How to Change Unhealthy Habits

You can overcome bad habits—starting with these 10 steps..

Posted July 14, 2016 | Reviewed by Devon Frye

Do you ever find yourself standing at the refrigerator when you’re not hungry? Have you ever reached for the one food in your cupboard that is guaranteed to be bad for you?

It’s not just you. We all do it. These are “bad” habits—and habits, by definition, are the things we are so used to that they become our default even when we know better. Instead of using the word “bad,” however, let’s call them “unhealthy”—it's much more accurate and less judgmental.

Whether it’s not sleeping , lack of exercise, poor food choices, or overindulgence in alcohol —we know these things are not healthy for us. Why do we persist—and just as importantly, how can we stop?

The trick to getting rid of unhealthy habits is to stop justifying our poor choices and rewrite the script so we default to where we want to be. Although positive and affirmative self-talk is powerful, I am not going to whitewash today’s message with unhelpful clichés—which are about as useful as saying “just relax” to someone having a panic attack. Thus, “Just think positively,” or “Flex your willpower muscle” are not on my list of steps towards change. Instead, let’s dive into a really juicy, habit-changing discussion.

First, love yourself into change. The concept is simple. Use some compassion with yourself and notice that your unhealthy behavior is probably an alert that something is off-kilter in your life. Love yourself enough to make some changes. Don’t wait until you hit “rock bottom” to have to make the change.

Most unhealthy habits are in reaction to stress: excessive work (or hating your job), loss, worry, and avoidance of the tough stuff. These kinds of stressors can paralyze us. Change becomes harder than ever and we compensate for the stress by exercising behaviors that, though they are unhealthy, serve a clear purpose for us—whether physical, emotional, or psychological.

10 More Steps to Change Unhealthy Habits

- Identify the habits you want to change. This means bringing what is usually unconscious (or at least ignored) to your awareness. It does not mean beating yourself up about it. Make a list of things you’d like to change, and then pick one.

- Look at what you are getting out of it. In other words, how is your habit serving you? Are you looking for comfort in food? Numbness in wine? An outlet or connection online? Stress alleviation through eating or nail biting? This doesn’t have to be a long, complex process. You’ll figure it out—and you’ll have some good ideas about how to switch it up for healthier outcomes.

- Honor your own wisdom . Here’s a common scenario: You feel like you have no down-time, so you stay up way too late binge-watching your favorite show on Netflix. You know you’ll be exhausted and less productive the next day, but you feel “entitled” to something fun, just for you. Your wisdom, however, knows this is not a healthy way to get it. Use that wisdom to build something into your schedule that will provide what you really want. Realize you do have the answers and are capable of doing something different.

- Choose something to replace the unhealthy habit. Just willing yourself to change isn’t enough because it does not address the underlying benefit of the behavior you want to replace. What can you do instead of standing in front of the fridge when you’re stressed ? If you have a plan, you will be “armed” with tools and a replacement behavior. Next time you catch yourself not hungry but standing in front of the refrigerator anyway, try a replacement behavior. Some ideas: Breathe in to the count of 4 and breathe out to the count of 8, focusing only on your breathing. Do that 4 times and see how you feel. If you need more support, stand there until you come up with one reason why you shouldn’t continue with this habit. This is a key step. When you do something different to replace an unhealthy habit, acknowledge to yourself that you are doing it differently. You need to bring whatever it is that is subconscious to the conscious mind so that you can emphasize your ability to change. It can be as simple as saying to yourself, “Look at that. I made a better choice.”

- Remove triggers. If Doritos are a trigger, throw them out on a day you feel strong enough to do so. If you crave a cigarette when you drink socially, avoid social triggers—restaurants, bars, nights out with friends. This doesn't have to be forever—just for a while, until you feel secure in your new habit. Sometimes certain people are our triggers. Remember that you end up being like the five people you hang out with most. Look at who those people are: Do they inspire you or do they drag you down?

- Visualize yourself changing. Serious visualization retrains your brain. In this case, you want to think differently about your ability to change—so spend some time every day envisioning yourself with new habits. Picture yourself exercising and enjoying it, eating healthy foods, or fitting into those jeans. See yourself engaged in happy conversation with someone instead of standing in the back of the room. This kind of visualization really works. The now familiar idea that “nerves that fire together wire together” is based on the idea that the more you think about something—and do it—the more it becomes wired in your brain. Your default choice can actually be a healthier one for you.

- Monitor your negative self-talk. The refrain in your brain can seriously affect your default behaviors. So when you catch yourself saying, “I’m fat” or “No one likes me,” reframe it or redirect it. Reframing is like rewriting the script. Replace it with, “I’m getting healthy, or “My confidence is growing.” Redirecting is when you add to your negative self-talk of “I’m fat” with “But I’m working my way into a healthier lifestyle.” Judging yourself only keeps you stuck. Retrain the judgmental brain.

- Take baby steps, if necessary. Even if you can’t fully follow through with a new habit right away, do something small to keep yourself on track. For example, if you’ve blocked out an hour to exercise and you suddenly have to go to a doctor’s appointment, find another time to squeeze in at least 15 minutes. That way, you’ll reinforce your new habit, even if you can't commit 100 percent.

- Accept that you will sometimes falter. We all do. Habits don’t change overnight. Love yourself each time you do and remind yourself that you are human.

- Know that it will take time . Habits usually take several weeks to change. You have to reinforce that bundle of nerves in your brain to change your default settings.

Bring the process to your awareness by writing it down. It is very easy to forget a new plan that is conceived with best intentions, but never reinforced. For maximum success, take 15 minutes to plan out your new habit, pen in hand.

And yes, you can do this.

Teri Goetz, MS, LAC, ACC, is a doctor of Chinese medicine, transformational coach, speaker, group facilitator, and author.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Asking the internet about birth control

‘Harvard Thinking’: Facing death with dignity

Novel teamwork, promising results for glioblastoma treatment

Breaking a bad habit can be done, say experts.

Nuthawut Somsuk/iStock

How to break a bad habit

Harvard Health Blog

Make it easier by taking a hard look at motive, modification, and mindset

We all have habits we’d like to get rid of, and every night we give ourselves the same pep talk: I’ll go to bed earlier. I will resist that cookie. I will stop biting my nails. And then tomorrow comes, we cave, and feel worse than bad. We feel defeated and guilty because we know better and still can’t resist.

The cycle is understandable, because the brain doesn’t make changes easily. But breaking an unhealthy habit can be done. It takes intent, a little white-knuckling, and some effective behavior modification techniques. But even before that, it helps to understand what’s happening in our brains, with our motivations, and with our self-talk.

We feel rewarded for certain habits

Good or bad habits are routines, and routines, like showering or driving to work, are automatic and make our lives easier. “The brain doesn’t have to think too much,” says Stephanie Collier, director of education in the division of geriatric psychology at McLean Hospital, and instructor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School.

Bad habits are slightly different, but when we try to break a bad one we create dissonance, and the brain doesn’t like that, says Luana Marques, associate professor of psychology at Harvard Medical School. The limbic system in the brain activates the fight-flight-or-freeze responses, and our reaction is to avoid this “threat” and go back to the old behavior, even though we know it’s not good for us.

Often, habits that don’t benefit us still feel good, since the brain releases dopamine. It does this with anything that helps us as a species to survive, like eating or sex. Avoiding change qualifies as survival, and we get rewarded (albeit temporarily), so we keep reverting every time. “That’s why it’s so hard,” Collier says.

Finding the reason why you want to change

But before you try to change a habit, it’s fundamental to identify why you want to change. When the reason is more personal — you want to be around for your kids; you want to travel more — you have a stronger motivation and a reminder to refer back to during struggles.

After that, you want to figure out your internal and external triggers, and that takes some detective work. When the bad-habit urge hits, ask when, where, and with whom it happens, and how you are feeling, be it sad, lonely, depressed, nervous. It’s a mixing and matching process and different for every person, but if you notice a clue beforehand, you might be able to catch yourself, Collier says.

The next part — and sometimes the harder part — is modifying your behavior. If your weakness is a morning muffin on the way to work, the solution might be to change your route. But environments can’t always be altered, so you want to find a replacement, such as having almonds instead of candy or frozen yogurt in lieu of ice cream. “You don’t have to aim for perfect, but just a little bit healthier,” Collier says.

This is an excerpt from an article that appears on the Harvard Health Publishing website .

To read the full story

Share this article

You might like.

Only a fraction of it will come from an expert, researchers say

In podcast episode, a chaplain, a bioethicist, and a doctor talk about end-of-life care

Researchers cite ‘academic medicine’ as key factor in success

College accepts 1,937 to Class of 2028

Students represent 94 countries, all 50 states

Pushing back on DEI ‘orthodoxy’

Panelists support diversity efforts but worry that current model is too narrow, denying institutions the benefit of other voices, ideas

Aspirin cuts liver fat in trial

10 percent reduction seen in small study of disease that affects up to a third of U.S. adults

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

How to Break Up with Your Bad Habits

Why is breaking a habit so difficult? Because habits are made up of three components: a trigger (for example, feeling stressed), a behavior (browsing the Internet), and a reward (feeling sated). Each time we reinforce the reward, we become more likely to repeat the behavior. This is why old habits are so hard to break — it takes more than self-control to change them. But after 20 years of studying the behavioral neuroscience of how habits form, and the best way to tackle them, researchers have found a surprisingly natural solution: using mindfulness training to make people more aware of the “reward” reinforcing their behavior. Doing so helps people tap into what is driving their habit in the first place. Once this happens, they are more easily able to change their association with the “reward” from a positive one to a more accurate (and often negative) one.

Breaking habits is hard. We all know this, whether we’ve failed our latest diet (again), or felt the pull to refresh our Instagram feed instead of making progress on a work project that is past due. This is largely because we are constantly barraged by stimuli engineered to make us crave and consume , stimuli that hijack the reward-based learning system in our brains designed initially for survival.

- JB Jud Brewer MD PhD is an addiction psychiatrist and neuroscientist specializing in anxiety and habit change. He is an associate professor at Brown University’s School of Public Health and Medical School and the author of The Craving Mind: From Cigarettes to Smartphones to Love — Why We Get Hooked and How We Can Break Bad Habits . Dr. Brewer has posted 20+ short videos on how to develop resilience and work with Coronavirus-related mental health issues on his YouTube Channel .

Partner Center

A monthly newsletter from the National Institutes of Health, part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Search form

January 2012

Print this issue

Breaking Bad Habits

Why It’s So Hard to Change

If you know something’s bad for you, why can’t you just stop? About 70% of smokers say they would like to quit. Drug and alcohol abusers struggle to give up addictions that hurt their bodies and tear apart families and friendships. And many of us have unhealthy excess weight that we could lose if only we would eat right and exercise more. So why don’t we do it?

NIH-funded scientists have been searching for answers. They’ve studied what happens in our brains as habits form. They’ve found clues to why bad habits, once established, are so difficult to kick. And they’re developing strategies to help us make the changes we’d like to make.

“Habits play an important role in our health,” says Dr. Nora Volkow, director of NIH’s National Institute on Drug Abuse. “Understanding the biology of how we develop routines that may be harmful to us, and how to break those routines and embrace new ones, could help us change our lifestyles and adopt healthier behaviors.”

Habits can arise through repetition. They are a normal part of life, and are often helpful. “We wake up every morning, shower, comb our hair or brush our teeth without being aware of it,” Volkow says. We can drive along familiar routes on mental auto-pilot without really thinking about the directions. “When behaviors become automatic, it gives us an advantage, because the brain does not have to use conscious thought to perform the activity,” Volkow says. This frees up our brains to focus on different things.

Habits can also develop when good or enjoyable events trigger the brain’s “reward” centers. This can set up potentially harmful routines, such as overeating, smoking, drug or alcohol abuse, gambling and even compulsive use of computers and social media.

“The general machinery by which we build both kinds of habits are the same, whether it’s a habit for overeating or a habit for getting to work without really thinking about the details,” says Dr. Russell Poldrack, a neurobiologist at the University of Texas at Austin. Both types of habits are based on the same types of brain mechanisms.

“But there’s one important difference,” Poldrack says. And this difference makes the pleasure-based habits so much harder to break. Enjoyable behaviors can prompt your brain to release a chemical called dopamine A brain chemical that regulates movement, emotion, motivation and pleasure. . “If you do something over and over, and dopamine is there when you’re doing it, that strengthens the habit even more. When you’re not doing those things, dopamine creates the craving to do it again,” Poldrack says. “This explains why some people crave drugs, even if the drug no longer makes them feel particularly good once they take it.”

In a sense, then, parts of our brains are working against us when we try to overcome bad habits. “These routines can become hardwired in our brains,” Volkow says. And the brain’s reward centers keep us craving the things we’re trying so hard to resist.

The good news is, humans are not simply creatures of habit. We have many more brain regions to help us do what’s best for our health.

“Humans are much better than any other animal at changing and orienting our behavior toward long-term goals, or long-term benefits,” says Dr. Roy Baumeister, a psychologist at Florida State University. His studies on decision-making and willpower have led him to conclude that “self-control is like a muscle. Once you’ve exerted some self-control, like a muscle it gets tired.”

After successfully resisting a temptation, Baumeister’s research shows, willpower can be temporarily drained, which can make it harder to stand firm the next time around. In recent years, though, he’s found evidence that regularly practicing different types of self-control—such as sitting up straight or keeping a food diary—can strengthen your resolve.

“We’ve found that you can improve your self-control by doing exercises over time,” Baumeister says. “Any regular act of self-control will gradually exercise your ‘muscle’ and make you stronger.”

Volkow notes that there’s no single effective way to break bad habits. “It’s not one size fits all,” she says.

One approach is to focus on becoming more aware of your unhealthy habits. Then develop strategies to counteract them. For example, habits can be linked in our minds to certain places and activities. You could develop a plan, say, to avoid walking down the hall where there’s a candy machine. Resolve to avoid going places where you’ve usually smoked. Stay away from friends and situations linked to problem drinking or drug use.

Another helpful technique is to visualize yourself in a tempting situation. “Mentally practice the good behavior over the bad,” Poldrack says. “If you’ll be at a party and want to eat vegetables instead of fattening foods, then mentally visualize yourself doing that. It’s not guaranteed to work, but it certainly can help.”

One way to kick bad habits is to actively replace unhealthy routines with new, healthy ones. Some people find they can replace a bad habit, even drug addiction, with another behavior, like exercising. “It doesn’t work for everyone,” Volkow says. “But certain groups of patients who have a history of serious addictions can engage in certain behaviors that are ritualistic and in a way compulsive—such as marathon running—and it helps them stay away from drugs. These alternative behaviors can counteract the urges to repeat a behavior to take a drug.”

Another thing that makes habits especially hard to break is that replacing a first-learned habit with a new one doesn’t erase the original behavior. Rather, both remain in your brain. But you can take steps to strengthen the new one and suppress the original one. In ongoing research, Poldrack and his colleagues are using brain imaging to study the differences between first-learned and later-learned behaviors. “We’d like to find a way to train people to improve their ability to maintain these behavioral changes,” Poldrack says.

Some NIH-funded research is exploring whether certain medications can help to disrupt hard-wired automatic behaviors in the brain and make it easier to form new memories and behaviors. Other scientific teams are searching for genes that might allow some people to easily form and others to readily suppress habits.

Bad habits may be hard to change, but it can be done. Enlist the help of friends, co-workers and family for some extra support.

Related Stories

Mindfulness Training Can Promote Healthy Choices

Yoga for Health: A New e-Book

Addressing Childhood Bullying

Stop Smoking Early To Improve Cancer Survival

NIH Office of Communications and Public Liaison Building 31, Room 5B52 Bethesda, MD 20892-2094 [email protected] Tel: 301-451-8224

Editor: Harrison Wein, Ph.D. Managing Editor: Tianna Hicklin, Ph.D. Illustrator: Alan Defibaugh

Attention Editors: Reprint our articles and illustrations in your own publication. Our material is not copyrighted. Please acknowledge NIH News in Health as the source and send us a copy.

For more consumer health news and information, visit health.nih.gov .

For wellness toolkits, visit www.nih.gov/wellnesstoolkits .

Changing Habits

We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.

Introduction

Have you ever stopped to think about your habits or how they impact your daily life? Have you ever needed to change your habits because of a new environment like online learning or campus life? According to experts with Psychology Today, habits form when new behaviors become automatic and are enacted with minimum conscious awareness. That’s because “the behavioral patterns we repeat most often are literally etched into our neural pathways.”

Think about that last quote for a moment. Now, think about habits you do automatically. For example, how many times a day do you pick up your mobile phone to read text messages, wander on Facebook, or check your Instagram account? Did you actively think to yourself, “It’s time to check Instagram now?” Or did it just happen without much conscious effort?

While some habits can be detrimental, such as wasting an hour on Twitter when you should be studying, others can be great to have around. Learning to brush your teeth when you were young helps you have good dental health when you’re older. Another example is shutting off the lights when you leave a room. That habit helps save on your energy bill.

In this handout we are going to provide an overview of strategies that can help you better understand habit formation and how to create and maintain beneficial habits. Along the way we are going to provide some activities that can help you start putting these strategies into practice.

Understanding habit formation

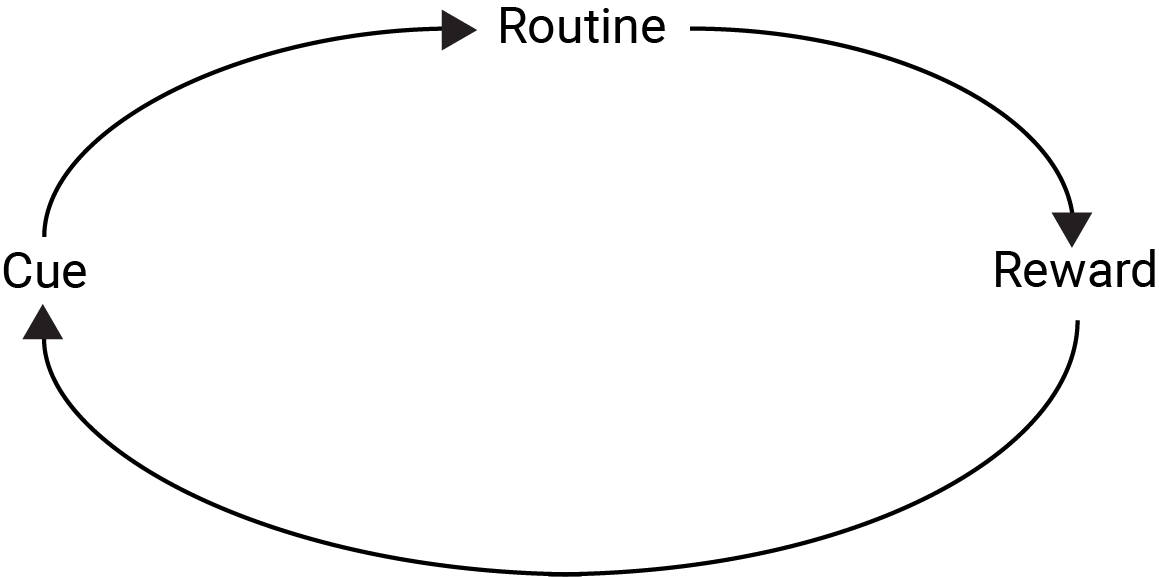

In the Power of Habit, Duhigg (2012) explains that MIT researchers discovered a three-step neurological pattern that forms the core of every habit (see figure 1). The first step is cue. It is a trigger that tells your brain to go into automatic mode and prompts the behavior to unfold. The second step is routine, which is the behavior itself and the action you take. The last step is reward. It helps your brain determine if a particular habit loop is worth remembering or not. Generally, habits have immediate or latent rewards. Habits with immediate rewards are easier to pick up and condition, whereas those with delayed rewards are more difficult to commit to and maintain. Think about how easy it is to check your iPhone compared to exercising more.

Let’s use the Instagram example to explain further how the habit loop works.

Cue: Your cell phone receives a push notification that someone likes or commented on one of your photos. The notification serves as a cue (or trigger) that tells you to check your account.

Routine: This is the actual behavior. When you receive the push notification, you automatically check your Instagram account.

Reward: This is the benefit you gain from doing the behavior (e.g., finding out who likes or commented on one of your photos). Recall that the reward helps the brain figure out if this particular loop is worth remembering for the future.

Because some habits are beneficial, let’s take a closer look at the example of turning out the lights when you leave a room. Cue: The light tells your brain to go into automatic mode and which habit to use when leaving the room. Routine: The actual behavior of turning out the light. Reward: A lower utility bill and better overall home energy budget.

Changing the habit loop

Now that you have an understanding of how habits form, let’s turn attention to changing them. Consider the following scenario:

Every day after class you go to Starbucks to hang out with friends instead of going to the library to study. You know that you need to spend a couple hours each day studying but socializing with friends makes you happy. Your goal is to implement a routine that accounts for more study time and yields the same happy feeling of hanging out with friends. But how might you do that?

One way would be to convince your friends to meet in the library and spend a couple of hours studying together. Afterward, you could treat yourselves at Starbucks. Another routine would be to study on your own and then meet your friends at Starbucks.

In either case, you replace a negative routine (going to Starbucks before studying) with a healthier one (studying before going to Starbucks). By changing these routines, you keep the reward of socializing with your friends while gaining new ones: earning better grades. By changing your routine, you increase your chances of earning multiple rewards.

Let’s plug this new routine into the habit loop to see how it works.

Cue: The time your class ends tells your brain which habit to employ. If you want to be extra ambitious, you could create a calendar notification on your computer or mobile device. Routine: Studying after class with friends or alone. Reward: Socializing with friends at Starbucks after studying; earning better grades.

Putting what we know into practice

The next step is to think about a habit you want to change. That begins by first describing the habit. Below are a few questions to help get you started. They were developed by Claiborn and Pedrick (2001), authors of The Habit Change Workbook.

- Identify a habit you would like to change.

- When did the habit begin, or when do you first remember doing it?

- Has the habit changed over time? If so, describe the changes that you have noticed.

- When do you typically engage in the habitual behavior (day and time)?

- Do you engage in the habit in a specific location?

- What else is usually happening in your life when the habit occurs?

- Does your behavior affect other people or facets of your life?

- What does the habit do for you?

- How happy (or unhappy) are you as result of your habits, or what are the rewards.

Second, you need to understand how the habit operates by diagnosing its cue, routine and reward. This will help you to gain power over it and begin making changes you seek to make.

- What is the Habit? _________________________

- What is the Cue? __________________________

- What is the Routine? _______________________

- What is the Reward? _______________________

Because a habit is a formula that the mind automatically follows, you need to re-engineer that formula by creating a new habit loop. In the spaces below, think of a healthy routine by planning for the cue and choosing a behavioral pattern that yields the reward you want. You may provide a list of multiple routines before settling on one. In addition, the reward does not need to be overly elaborate. The goal is to establish a positive association with putting the habit into practice.

It is important to note that telling yourself there is a reward is not enough for a habit to stick. According to Duhigg, one way to get a habit to stick is to repeat it. In other words, repetition is important if you want your brain to crave the reward. He notes that “countless studies have shown that a cue and a reward, on their own, aren’t enough for a new habit to last. Only when your brain starts expecting the reward—craving the endorphins or sense of accomplishment—will it become automatic” (p. 51).

Anticipating pitfalls

In a two-year study that examines the rate of self-change attempts of New Year’s resolvers, Norcross and Vangarelli (1988) note that 77% of resolution-makers maintained pledges for one week. However, only 19% of them kept their resolutions after two years. If this statistic is indicative of habits in general, “at least 8 times out of 10, you are more likely to fall back into your old habits and patterns than you are to stick with a new behavior” (Clear, 2015).

So the question is: how do you make new habits stick when the odds are not in your favor? You learned that repetition is an important factor, but that is only one piece of the puzzle. Experts agree that maintaining healthy habits require you to anticipate pitfalls. Listed below are a few common mistakes that people make and some solutions that can help you navigate around these hazards and toward healthy behavior patterns.

Pitfall 1: Trying to change everything at one time.

Solution: Try to pick one thing and do it well.

The following scenario is one you know too well. You start creating a new habit by first generating a list of things you hope to change or adopt. You tell yourself you have the willpower to succeed and you start off doing quite well. Then life responsibilities start piling up or the persistent urge to indulge in old habits kicks in. Before you know it, you feel overwhelmed and slowly revert to old behavior patterns. For example, if you suddenly shift to working from home when you’re used to working in the library or going to a coffee shop, you might slip into old habits like watching TV or going to the kitchen to grab a snack.

So, how do you avoid this “overwhelmed” feeling? In “The Power Less,” Leo Babauta (2009) suggests changing one habit at a time and focusing on doing it well before moving on to the next one. He recommends creating a list of behavioral changes you want to make and then chunking them based on which one you want to accomplish first. The key is focusing on the one goal, and after it becomes a ritual you move on to the next one.

If you find yourself struggling to pick a habit from the list of changes, try asking the following questions:

- Which goal is going to pull the rest of your life in line? This is referred to as focusing on a “keystone habit” (Clear, 2015; Duhigg, 2012).

- Focus on the small steps and take your time.

- What is the ripple effect of the keystone habit? In other words, what are the primary and secondary benefits of changing the habit? For example, exercising regularly leads to more energy (primary) and results in better sleep and focused study habits (secondary).

Pitfall 2: Trying to begin with a large habit.

Solution: Try to make the habit “so easy you can’t say no” (Babauta, 2013, qtd. in Clear, 2015).

You know that starting a new habit is difficult. And when you try to achieve the result you want right away with max effort, you tend to increase that difficulty and set yourself up for failure. Take the goal of developing a habit of exercising regularly. You start off by working out an hour or two everyday. After a week or so you discover that devoting a large amount of time to a new exercise regimen, when the body is not used to a workout routine, is too difficult to maintain. Ultimately, you give up. Most everyone has experienced a situation like that before.

According to habits experts, the goal should be to start small and easy, build up to thirty minutes and then to an hour or two. Babauta explains that “actually doing the habit is much more important than how much you do.” He says:

If you want to exercise, it’s more important that you actually do the exercise on a regular basis, rather than doing enough to get a benefit right away. Sure, maybe you need 30 minutes of exercise to see some fitness improvements, but try doing 30 minutes a day for two weeks. See how far you get, if you haven’t been exercising regularly. Then, if you don’t succeed, try 1-2 minutes a day. See how far you get there.

If you can do two weeks of 1-2 minutes of exercise, you have a strong foundation for a habit. Add another week or two, and the habit is almost ingrained. Once the habit is strong, you can add a few minutes here and there. Soon you’ll be doing 30 minutes on a regular basis—but you started out really small.

Let’s now put this situation in the context of establishing stronger study habits, using the example of studying before hanging out with friends at Starbucks.

- Cue: The time your last class ends tells your brain to go into automatic mode and which habit to employ once class is over (i.e., going to the library).

- Routine: Studying after class with friends or alone.

- Reward: Socializing with friends at Starbucks after studying; earning better grades

It is important to ask how much time is needed for studying. Thirty minutes, one hour, two hours, more? Remember, this is a new routine and you want to avoid failure. If your goal is to study two hours after class, you might start out studying for thirty or forty-five minutes and then lead up to that. Remember, you want to make the habit “so easy you can’t say no” (Babauta, 2013).

Pitfall 3: Not changing your environment.

Solution: Create an environment that promotes accountability and healthy lifestyle.

According to Clear (2015), “if your environment doesn’t change, you probably won’t either.” That means habits are part of your physical and social environment. For example, smelling delicious food is a cue to eat or seeing your television when you get home from work is a cue to sit down and relax for the evening (Jackson, Morrow, Hill & Dishman, 2004). Similarly, receiving a notification on your iPhone everyday at noon or a text message from a friend could be a cue that it is time to study.

You could take this example one step further by filling your environment with motivational posters or post-it notes with inspirational quotes like this: “every journey begins with a single step” (Confucius, philosopher). You could also keep a running record of your results and make it visible. For example, you could report progress in a journal or in social media or a blog. You could even tell your family, friends and colleagues what your goals are and have them send you reminders and encouragement via Twitter, Facebook or text messaging.

Once again, let’s put this situation in the context of establishing stronger study habits. Think about how you might change your physical and social environment. Keep in mind how others might help to hold you accountable. As experts contend, encouragement from friends, family and colleagues provides accountability and support for achieving successful goals (Jackson, Morrow, Hill & Dishman, 2004; Dolan, 2012; Oliveira, 2015). They can keep you on track and provide reminders and, more importantly, the necessary enthusiasm and support for when you feel like you’re going to falter. For example, if you have a hard time staying on task when you work on a larger project, you might decide to have a Zoom meeting with a friend where both of you check in with each other briefly and remain on the call while you work independently. As you work, you can periodically check in with each other to offer support and encouragement.

Creating a plan

Below are four simple steps for changing one habit at a time (Oliveira, 2015):

- Choose one keystone habit and do it well. It is ideal to select one goal that will bring your life in line. Be sure to start with something easy to achieve and then slowly enhance the degree of difficulty.

- Write down your plan: Try to create a habit loop: cue, routine and reward. Make visible what you will do each day. Remember to start off slow, focusing on creating ritual first and results second. Also, define success in measurable terms.

- Make your goal public and develop a support team: Ask your family, friends or colleagues to help hold you accountable. Be sure to report your progress each day, either within a journal or through your favorite social media outlet.

- Make a plan for when you falter. Write down what caused you to stumble. You want to be as honest as possible. Most importantly, don’t be afraid to start over with a revised plan.

How can technology help?

Need some help changing your habits? Technology can help you with various steps in the habit-formation process:

Calendars as Cues. Using an online calendar like Google Calendar , iCal , or Outlook 365 Calendar can help you schedule the habits you want to build. You can make events that recur monthly, weekly, or daily, and set reminders to let you know it’s time to get started on a task.

Checklists for Chunking Large Projects. Project management websites like Trello and phone apps like Color Note can help you break down large projects into smaller, more manageable tasks. Use these tools to write down small steps, and check each step off as you work. You can even write a step for rewards, so you remember to reinforce good habits!

Habit Trackers. There are also apps designed specifically to help you form good habits, including Streaks , Habitshare , and Habitica . Many of these apps help you assess your habits, break them into small pieces, stay accountable, and reward you for completing your goals.

Testimonials

Check out what other students and writers have tried!

Keeping Motivated With Rewards : Read more about how peer tutor Caleb uses rewards to stay motivated.

Optimizing Attention : A Learning Center Peer Tutor shares her experience using the Learning Center’s Optimizing Attention worksheets.

How I Use the Pomodoro Technique : A Writing Coach shares his experience using the Pomodoro Technique to build a routine/reward system.

Works consulted

Babauta, L. (2013, February 13). The four habits that form habits. Zen Habits: Breathe. Retrieved from http://zenhabits.net/habitses/

Claiborn, J., & Pedrick, C. (2001). The Habit change workbook: How to break bad habits and form good ones. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

Clear, J. (2015). The 3 R’s of habit change: How to start new habits that actually stick [Web log comment]. Retrieved from http://jamesclear.com/three-steps-habit-change

Dolan, S. (2012, January, 20). Benefits of group exercise. American College of Sports Medicine. Retrieved from https://www.acsm.org/public-information/articles/2012/01/20/benefits-of-group-exercise

Duhigg, C. (2014). The Power of habit: Why we do what we do in life and business. New York: Random House.

Habit Formation Basics. (2015). Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/basics/habit-formation

Jackson, A.W., Morrow, J.R., Hill, D.W., & Dishman, R.K. (2004). Physical activity for health and fitness. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Norcross, J. C., & Vangarelli, D. J. (1988). The resolution solution: Longitudinal examination of New Year’s change attempts. Journal of Substance Abuse, 1, 127–134.

Oliveira, R. (2015, August 25). Change your life – one habit at a time. UC Davis Integrative Medicine Program. Retrieved from http://www.ucdintegrativemedicine.com/2015/08/change-your-life-forever-one-habit-at-a-time/

If you enjoy using our handouts, we appreciate contributions of acknowledgement.

Make a Gift

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Entire Site

- Research & Funding

- Health Information

- About NIDDK

- Diet & Nutrition

Changing Your Habits for Better Health

- Español

On this page:

What stage of change are you in?

Contemplation: are you thinking of making changes, preparation: have you made up your mind, action: have you started to make changes, maintenance: have you created a new routine, clinical trials.

Are you thinking about being more active? Have you been trying to cut back on less healthy foods? Are you starting to eat better and move more but having a hard time sticking with these changes?

Old habits die hard. Changing your habits is a process that involves several stages. Sometimes it takes a while before changes become new habits. And, you may face roadblocks along the way.

Adopting new, healthier habits may protect you from serious health problems like obesity and diabetes . New habits, like healthy eating and regular physical activity, may also help you manage your weight and have more energy. After a while, if you stick with these changes, they may become part of your daily routine.

The information below outlines four stages you may go through when changing your health habits or behavior. You will also find tips to help you improve your eating, physical activity habits, and overall health. The four stages of changing a health behavior are

- contemplation

- preparation

- maintenance

Contemplation: “I’m thinking about it.”

In this first stage, you are thinking about change and becoming motivated to get started.

You might be in this stage if you

- have been considering change but are not quite ready to start

- believe that your health, energy level, or overall well-being will improve if you develop new habits

- are not sure how you will overcome the roadblocks that may keep you from starting to change

Preparation: “I have made up my mind to take action.”

In this next stage, you are making plans and thinking of specific ideas that will work for you.

- have decided that you are going to change and are ready to take action

- have set some specific goals that you would like to meet

- are getting ready to put your plan into action

Action: “I have started to make changes.”

In this third stage, you are acting on your plan and making the changes you set out to achieve.

- have been making eating, physical activity, and other behavior changes in the last 6 months or so

- are adjusting to how it feels to eat healthier, be more active, and make other changes such as getting more sleep or reducing screen time

- have been trying to overcome things that sometimes block your success

Maintenance: “I have a new routine.”

In this final stage, you have become used to your changes and have kept them up for more than 6 months.

You might be in this stage if

- your changes have become a normal part of your routine

- you have found creative ways to stick with your routine

- you have had slip-ups and setbacks but have been able to get past them and make progress

Did you find your stage of change? Read on for ideas about what you can do next.

Making the leap from thinking about change to taking action can be hard and may take time. Asking yourself about the pros (benefits) and cons (things that get in the way) of changing your habits may be helpful. How would life be better if you made some changes?

Think about how the benefits of healthy eating or regular physical activity might relate to your overall health. For example, suppose your blood glucose, also called blood sugar, is a bit high and you have a parent, brother, or sister who has type 2 diabetes . This means you also may develop type 2 diabetes. You may find that it is easier to be physically active and eat healthy knowing that it may help control blood glucose and protect you from a serious disease.

You may learn more about the benefits of changing your eating and physical activity habits from a health care professional. This knowledge may help you take action.

Look at the lists of pros and cons below. Find the items you believe are true for you. Think about factors that are important to you.

Healthy Eating

Physical activity.

If you are in the preparation stage, you are about to take action. To get started, look at your list of pros and cons. How can you make a plan and act on it?

The chart below lists common roadblocks you may face and possible solutions to overcome roadblocks as you begin to change your habits. Think about these things as you make your plan.

Once you have made up your mind to change your habits, make a plan and set goals for taking action. Here are some ideas for making your plan:

- learn more about healthy eating and food portions

- learn more about being physically active

- healthy foods that you like or may need to eat more of—or more often

- foods you love that you may need to eat less often

- things you could do to be more physically active

- fun activities you like and could do more often, such as dancing

After making your plan, start setting goals for putting your plan into action. Start with small changes. For example, “I’m going to walk for 10 minutes, three times a week.” What is the one step you can take right away?

You are making real changes to your lifestyle, which is fantastic! To stick with your new habits

- review your plan

- look at the goals you set and how well you are meeting them

- overcome roadblocks by planning ahead for setbacks

- reward yourself for your hard work

Track your progress

- Tracking your progress helps you spot your strengths, find areas where you can improve, and stay on course. Record not only what you did, but how you felt while doing it—your feelings can play a role in making your new habits stick.

- Recording your progress may help you stay focused and catch setbacks in meeting your goals. Remember that a setback does not mean you have failed. All of us experience setbacks. The key is to get back on track as soon as you can.

- You can track your progress with online tools such as the NIH Body Weight Planner . The NIH Body Weight Planner lets you tailor your calorie and physical activity plans to reach your personal goals within a specific time period.

Overcome roadblocks

- Remind yourself why you want to be healthier. Perhaps you want the energy to play with your nieces and nephews or to be able to carry your own grocery bags. Recall your reasons for making changes when slip-ups occur. Decide to take the first step to get back on track.

- Problem-solve to “outsmart” roadblocks. For example, plan to walk indoors, such as at a mall, on days when bad weather keeps you from walking outside.

- Ask a friend or family member for help when you need it, and always try to plan ahead. For example, if you know that you will not have time to be physically active after work, go walking with a coworker at lunch or start your day with an exercise video.

Reward yourself

- After reaching a goal or milestone, allow for a nonfood reward such as new workout gear or a new workout device. Also consider posting a message on social media to share your success with friends and family.

- Choose rewards carefully. Although you should be proud of your progress, keep in mind that a high-calorie treat or a day off from your activity routine are not the best rewards to keep you healthy.

- Pat yourself on the back. When negative thoughts creep in, remind yourself how much good you are doing for your health by moving more and eating healthier.

Make your future a healthy one. Remember that eating healthy, getting regular physical activity, and other healthy habits are lifelong behaviors, not one-time events. Always keep an eye on your efforts and seek ways to deal with the planned and unplanned changes in life.

Now that healthy eating and regular physical activity are part of your routine, keep things interesting, avoid slip-ups, and find ways to cope with what life throws at you.

Add variety and stay motivated

- Mix up your routine with new physical activities and goals, physical activity buddies, foods, recipes, and rewards.

Deal with unexpected setbacks

- Plan ahead to avoid setbacks. For example, find other ways to be active in case of bad weather, injury, or other issues that arise. Think of ways to eat healthy when traveling or dining out, like packing healthy snacks while on the road or sharing an entrée with a friend in a restaurant.

- If you do have a setback, don’t give up. Setbacks happen to everyone. Regroup and focus on meeting your goals again as soon as you can.

Challenge yourself!

- Revisit your goals and think of ways to expand them. For example, if you are comfortable walking 5 days a week, consider adding strength training twice a week. If you have limited your saturated fat intake by eating less fried foods, try cutting back on added sugars, too. Small changes can lead to healthy habits worth keeping.

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and other components of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) conduct and support research into many diseases and conditions.

What are clinical trials, and are they right for you?

Clinical trials are part of clinical research and at the heart of all medical advances. Clinical trials look at new ways to prevent, detect, or treat disease. Researchers also use clinical trials to look at other aspects of care, such as improving the quality of life for people with chronic illnesses. Find out if clinical trials are right for you.

What clinical trials are open?

Clinical trials that are currently open and are recruiting can be viewed at www.ClinicalTrials.gov .

This content is provided as a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health. NIDDK translates and disseminates research findings to increase knowledge and understanding about health and disease among patients, health professionals, and the public. Content produced by NIDDK is carefully reviewed by NIDDK scientists and other experts.

The NIDDK would like to thank: Dr. Carla Miller, Associate Professor, Ohio State University

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Personal Development

- Routines and Habits

How to Change Bad Habits

Last Updated: February 6, 2024 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Annie Lin, MBA . Annie Lin is the founder of New York Life Coaching, a life and career coaching service based in Manhattan. Her holistic approach, combining elements from both Eastern and Western wisdom traditions, has made her a highly sought-after personal coach. Annie’s work has been featured in Elle Magazine, NBC News, New York Magazine, and BBC World News. She holds an MBA degree from Oxford Brookes University. Annie is also the founder of the New York Life Coaching Institute which offers a comprehensive life coach certification program. Learn more: https://newyorklifecoaching.com There are 13 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 146,877 times.

Habits often become so ingrained we don't even notice we're doing them. Whether your bad habit is a minor annoyance such as cracking your knuckles, or something more serious such as smoking, it takes conscious effort and smart planning to break the cycle. Don't hesitate to seek professional help if you can't break it on your own.

- Does the bad habit happen more often when you are stressed or nervous?

- Does it happen more often (or less often) at certain places or during certain activities?

- If you're trying to avoid eating junk food, move any junk food in your home out of the kitchen and other snacking areas, to a more difficult-to-access location. When shopping for food, avoid walking through the aisles that contain tempting junk food, or follow a strict, healthy shopping list and don't bring any extra cash or a credit card.

- If you're trying to avoid checking your cell phone all the time, shut down the phone or put it in airplane mode. If that doesn't work, turn off the cell phone and put it in a different room when you're at home.

- A classic example is the nail-biter that coats his nails in a nasty-tasting substance. Specialized products for this purpose are available at drugstores. [5] X Trustworthy Source American Academy of Dermatology Professional organization made of over 20,000 certified dermatologists Go to source

- Recovering alcoholics sometimes take medication that causes unpleasant symptoms if alcohol is drunk.

- For habits that aren't easy to make unpleasant, put a rubber band around your wrist and snap it against the skin to cause mild pain each time you catch yourself giving in to the habit. [6] X Research source

- Many people find a daily exercise routine or jog becomes similarly satisfying once they've turned it into a habit.

- Some bad habits have a "good habit" opposite that you can focus on improving, which some people find more rewarding and easier to keep up than breaking a bad one. For instance, to avoid unhealthy food, challenge yourself to cook a healthy dinner a certain number of times per week.

- For example, if you're quitting smoking, plan on getting up and making yourself coffee or chatting to a coworker when your coworkers take a smoking break. If a friend starts pulling out cigarettes during a conversation, think to yourself "no thank you, no thank you, no thank you" in case she offers you one.

- You might need to try several rewards before you find one that works. Try setting an alarm for fifteen minutes from now each time you use one of these rewards. When the alarm goes off, ask yourself whether you still crave the bad habit. If so, try a different reward next time. [10] X Research source

- Some anti-addiction programs have the helper sign a contract explaining exactly what they are responsible for, including actions the helper may not feel comfortable doing otherwise, such as throwing away another person's cigarettes or alcohol. [12] X Research source

- There are many types of programs, so don't give up if one of them doesn't work for you. Motivational interviewing and distress-tolerance treatment are two examples of professional treatments that are not easy to replicate on your own. [13] X Research source

How Long Does it Take to Break a Habit?

Habit Breaking Journal Entry Template

Expert Q&A

- If your bad habit is a serious addiction, pay close attention to whether or not it's your only method of dealing with stress or depression . Handling those issues in other ways can make the difference between quitting for good and failing. If this is having a serious effect on your life, contact your doctor or see a therapist. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://kidshealth.org/en/teens/motivation.html

- ↑ Annie Lin, MBA. Life & Career Coach. Expert Interview. 25 November 2019.

- ↑ https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/trade-bad-habits-for-good-ones

- ↑ https://psychcentral.com/health/steps-to-changing-a-bad-habit

- ↑ https://www.aad.org/public/everyday-care/nail-care-secrets/basics/stop-biting-nails

- ↑ https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/self-harm

- ↑ https://newsinhealth.nih.gov/2012/01/breaking-bad-habits

- ↑ https://psychcentral.com/blog/10-instant-ways-to-calm-yourself-down

- ↑ https://www.tricitymed.org/2017/12/5-tips-actually-relaxing-vacation/

- ↑ https://www.bowdoin.edu/baldwin-center/pdf/handout-self-rewards.pdf

- ↑ https://health.cornell.edu/resources/health-topics/meditation

- ↑ https://www.healthhub.sg/live-healthy/748/mens-health-focus-on-smoking-and-drinking

- ↑ https://www.mhanational.org/get-professional-help-if-you-need-it

About This Article

Medical Disclaimer

The content of this article is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, examination, diagnosis, or treatment. You should always contact your doctor or other qualified healthcare professional before starting, changing, or stopping any kind of health treatment.

Read More...

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Paula Luyto

Aug 20, 2016

Did this article help you?

Veasna E. C.

Apr 25, 2018

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

Improving Your Eating Habits

Obesity and Excess Weight Increase Risk of Severe Illness; Racial and Ethnic Disparities Persist

Food Assistance and Food Systems Resources

When it comes to eating, many of us have developed habits. Some are good (“I always eat fruit as a dessert”), and some are not so good (“I always have a sugary drink after work as a reward”). Even if you’ve had the same eating pattern for years, it’s not too late to make improvements.

Making sudden, radical changes, such as eating nothing but cabbage soup, can lead to short term weight loss. However, such radical changes are neither healthy nor a good idea and won’t be successful in the long run. Permanently improving your eating habits requires a thoughtful approach in which you reflect, replace, and reinforce.

- REFLECT on all of your specific eating habits, both bad and good; and, your common triggers for unhealthy eating.

- REPLACE your unhealthy eating habits with healthier ones.

- REINFORCE your new, healthier eating habits.

- Create a list of your eating and drinking habits. Keep a food and beverage diary for a few days. Write down everything you eat and drink, including sugary drinks and alcohol. Write down the time of day you ate or drank the item. This will help you uncover your habits. For example, you might discover that you always seek a sweet snack to get you through the mid-afternoon energy slump. Use this diary [PDF-105KB] to help. It’s good to note how you were feeling when you decided to eat, especially if you were eating when not hungry. Were you tired? Stressed out?

- Eating too fast

- Always cleaning your plate

- Eating when not hungry

- Eating while standing up (may lead to eating mindlessly or too quickly)

- Always eating dessert

- Skipping meals (or maybe just breakfast)

- Look at the unhealthy eating habits you’ve highlighted. Be sure you’ve identified all the triggers that cause you to engage in those habits. Identify a few you’d like to work on improving first. Don’t forget to pat yourself on the back for the things you’re doing right. Maybe you usually eat fruit for dessert, or you drink low-fat or fat-free milk. These are good habits! Recognizing your successes will help encourage you to make more changes.

- Opening up the cabinet and seeing your favorite snack food.

- Sitting at home watching television.

- Before or after a stressful meeting or situation at work.

- Coming home after work and having no idea what’s for dinner.

- Having someone offer you a dish they made “just for you!”

- Walking past a candy dish on the counter.

- Sitting in the break room beside the vending machine.

- Seeing a plate of doughnuts at the morning staff meeting.

- Swinging through your favorite drive-through every morning.

- Feeling bored or tired and thinking food might offer a pick-me-up.

- Circle the “cues” on your list that you face on a daily or weekly basis . While the Thanksgiving holiday may be a trigger to overeat, for now focus on cues you face more often. Eventually you want a plan for as many eating cues as you can.

- Is there anything I can do to avoid the cue or situation? This option works best for cues that don’t involve others. For example, could you choose a different route to work to avoid stopping at a fast food restaurant on the way? Is there another place in the break room where you can sit so you’re not next to the vending machine?

- For things I can’t avoid, can I do something differently that would be healthier? Obviously, you can’t avoid all situations that trigger your unhealthy eating habits, like staff meetings at work. In these situations, evaluate your options. Could you suggest or bring healthier snacks or beverages? Could you offer to take notes to distract your attention? Could you sit farther away from the food so it won’t be as easy to grab something? Could you plan ahead and eat a healthy snack before the meeting?

- Replace unhealthy habits with new, healthy ones . For example, in reflecting upon your eating habits, you may realize that you eat too fast when you eat alone. So, make a commitment to share a lunch each week with a colleague, or have a neighbor over for dinner one night a week. Another strategy is to put your fork down between bites. Also, minimize distractions, such as watching the news while you eat. Such distractions keep you from paying attention to how quickly and how much you’re eating.

- Eat more slowly. If you eat too quickly, you may “clean your plate” instead of paying attention to whether your hunger is satisfied.

- Eat only when you’re truly hungry instead of when you are tired, anxious, or feeling an emotion besides hunger. If you find yourself eating when you are experiencing an emotion besides hunger, such as boredom or anxiety, try to find a non-eating activity to do instead. You may find a quick walk or phone call with a friend helps you feel better.

- Plan meals ahead of time to ensure that you eat a healthy well-balanced meal.

- Reinforce your new, healthy habits and be patient with yourself . Habits take time to develop. It doesn’t happen overnight. When you do find yourself engaging in an unhealthy habit, stop as quickly as possible and ask yourself: Why do I do this? When did I start doing this? What changes do I need to make? Be careful not to berate yourself or think that one mistake “blows” a whole day’s worth of healthy habits. You can do it! It just takes one day at a time! Top of Page

Eating Disorders Information on common eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia, and binge eating disorder.

Losing Weight What is healthy weight loss and why should you bother?

Getting Started Check out some steps you can take to begin!

Keeping the Weight Off Losing weight is the first step. Once you’ve lost weight, you’ll want to learn how to keep it off.

To receive email updates about this topic, enter your email address.

- Physical Activity

- Overweight & Obesity

- Healthy Weight, Nutrition, and Physical Activity

- Breastfeeding

- Micronutrient Malnutrition

- State and Local Programs

- Prevent Type 2 Diabetes

- Prevent Heart Disease

- Healthy Schools – Promoting Healthy Behaviors

- Obesity Among People with Disabilities

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

- Search Please fill out this field.

- Newsletters

- Sweepstakes

- Healthy Eating

- How to Eat Healthy

10 Unhealthy Habits You Need to Change Now

Here are our top 10 daily habits to change to live a healthier, happier life.

Brierley is a dietitian nutritionist, content creator and strategist, and avid mental health advocate. She is co-host and co-creator of the Happy Eating Podcast, a podcast that breaks down the connection between food and mental wellness. Brierley previously served as Food & Nutrition Director for Cooking Light magazine and the Nutrition Editor at EatingWell magazine. She holds a master's degree in Nutrition Communications from the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University. Her work has appeared in Better Homes & Gardens, Southern Living, Real Simple, Livestrong.com, TheKitchn and more.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/brierley-horton-headshot-343d9f10a69f424aa1be9bd8504429f6.jpg)

Elizabeth Ward is a registered dietitian and award-winning nutrition communicator and writer. She has authored or co-authored 10 books for consumers about nutrition at all stages of life.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/elizabeth-ward-2000-02e67fa239844547a8a14ab32548560e.jpg)

1. Not Drinking Enough Water

2. eating late at night, 3. not getting enough exercise, 4. skimping on sleep, 5. eating too much sodium.

- 6. Choosing Foods Because They 'Sound Healthy'

7. Eating Lunch at Your Desk

8. cooking everything in olive oil, 9. skipping dessert, 10. not changing or sanitizing your kitchen sponge frequently enough.

Pictured recipe: Lemon, Cucumber & Mint Infused Water

Some of the things you do—or don't do—every day might be getting in the way of your efforts to be healthier. As you read this list of daily habits, don't beat yourself up if you find many of them resonate with you. We all have things we could change. And change can be hard—but there are some things that can help make it a little easier.

For example, a 2020 study in Frontiers in Psychology suggests that practicing new habits consistently and in the same context helps them become more automatic so that you don't have to think about them as much to do them. For example, let's say you want to eat more vegetables. You could choose lunch to start with and decide that you'll have at least one serving of vegetables at lunch each day. Lunch becomes your trigger to eat more vegetables—and once that habit is formed, you can build on it.

Another tool to try is habit stacking. This takes a habit you already have and piggybacks the new habit onto it. For example, let's say you want to start your day by drinking water. You could habit stack this with brushing your teeth in the morning. So, after you brush your teeth, you'll drink a glass of water.

Or piggyback it with two habits—going to bed and getting up in the morning. In this case, you could fill your glass of water at bedtime, so your trigger to fill your glass is getting ready for bed. Now when you get up—which is your trigger to drink the water—it's there.

There is no one perfect way to change habits. And if you lapse—which is likely when forming new habits—simply learn from it and keep going. Research, including a 2019 study in the American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine suggests that making specific goals and writing them down increases your chances of success.

Take a look at these 10 habits to see if there are any areas where you can make a healthy change. While it can be tempting to take on a bunch of new habits at once, working on one at a time and consistently practicing it will help change your brain and make the habit automatic.

Water accounts for 60% of your body, so it's not too surprising that drinking water benefits your total body health . Staying hydrated helps to keep your memory sharp, your mood stable and your motivation intact.

Keeping up with your fluids helps your skin stay supple, helps your body cool down when it's hot, allows your muscles and joints to work better and helps clean toxins from your body via your kidneys.

So, how much water should you be drinking? According to the National Academy of Sciences , adult men need about 13 cups per day of fluid, and adult women need about 9. That recommendation includes 2 1/2 cups of fluid from foods and also counts the fluid in coffee, tea and other soft drinks toward your fluid needs.

But because one size doesn't fit all, the best way to know if you're adequately hydrated is to monitor your urine color: If it's light yellow (the color of lemonade or straw), that means you're probably drinking enough.

There are a couple of reasons to consider having dinner earlier. Researchers suspect that eating dinner later and close to bedtime changes how the food is digested, including how fat is processed. This could lead to weight gain, per a 2020 study in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism .

Another reason is that you may sleep better. A 2020 study in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health suggests that eating close to bedtime can disrupt sleep quality.

And if you have gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), a 2022 review in Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management suggests that eating within three hours of bedtime makes acid reflux worse through the night.

Physical activity has so many benefits to our health that we can't name them all here (but we'll try). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) , exercise helps manage weight; improves brain health; strengthens bones, muscles, heart and lungs; helps you sleep better; improves mental health and reduces the risk of depression and anxiety; improves focus and judgment; improves the ability to perform everyday activities; prevents falls; helps manage blood sugar; and reduces the risk of chronic disease.

According to a 2020 review in Cold Springs Harbor Perspectives in Medicine , exercise is associated with longer life. This is because it delays the onset of at least 40 chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease and Type 2 diabetes.

The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans recommends that all healthy adults perform moderate exercise for at least 30 minutes five days a week or vigorous-intensity activity for at least 20 minutes three days a week. They also recommend muscle-strengthening activities at least twice a week.

It's important that you start where you're at and progressively increase the intensity and frequency of your exercise over time. One big mistake people make is going all out from the beginning and quickly burning out. Set big goals but start small and work up to your bigger goals.

You know that falling short of sleep is a major no-no, but why—what's the big deal? According to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) , not getting enough shut-eye can impact a whole slew of things. For starters, it can compromise your immune system, as well as your judgment and ability to make decisions—which can result in making mistakes or being injured.

Sleep deficiency is also linked to several chronic health problems, including heart disease, high blood pressure, kidney disease, diabetes, stroke, obesity and depression, per the NHLBI.

Being sleep-deprived may make it harder for you to lose weight if you're dieting—and more likely that you'll give in to that sweet temptation tomorrow.

While there is no magic number of hours to sleep (and the number changes with age), the NHLBI recommends 7 to 8 hours of sleep each night for adults. It's important to listen to your body and try to get the amount of sleep that your body needs to function at its best.

Pictured recipe: Air-Fryer Turkey Stuffed Peppers

According to the CDC, 90% of Americans eat about 1,000 milligrams more sodium each day than we should. Restaurant foods and processed foods both tend to be very high in sodium. One of the easiest ways to reduce your sodium intake is to cook at home using fresh ingredients. To decrease your sodium intake even further, try boosting the flavor of food cooked at home with herbs and spices rather than salt.

6. Choosing Foods Because They 'Sound Healthy'

More and more food labels are sporting health benefits on their labels. If such claims lure you in, know that just because a product lacks fat or gluten or carbs doesn't necessarily mean it's healthier. For example, fat-free products often deliver more sugar than their counterparts to make up for the flavor the product lacks from having the fat removed—and many full-fat options are the healthier choice.

Avoid being duped by a healthy-sounding label claim by comparing the nutrition facts panels and ingredient lists across brands of the same food category. It's worth stating that some of the healthiest foods at the grocery store don't have any packaging or branding—like fruits and vegetables.

Pictured recipe: Zucchini Noodles with Quick Turkey Bolognese

It's all too easy to munch on your midday meal desk-side, but according to 2022 research published in Appetite , distracted eating was correlated to higher body weight. Researchers recommend shutting off devices and taking a break from work so that you can focus on what you're eating, enjoying your food and noticing when you're starting to feel full.

Even though olive oil is packed with heart-healthy antioxidants (called polyphenols) and monounsaturated fats, there are times when it's not the best choice for cooking . Why? Because olive oil has a lower smoke point than some other oils (that's the point at which an oil literally begins to smoke, and olive oil's is between 365°F and 420°F).

When you heat olive oil to its smoke point, the beneficial compounds in the oil start to degrade, and potentially health-harming compounds form. So if you're cooking over high heat, skip it and choose a different oil.

When is olive oil a good idea? It's a great choice for making salad dressing or sautéing vegetables over medium heat.

You may think you're doing a good thing by skipping sweet treats. But studies, like the 2022 review in Einstein (Sao Paulo) suggest that feeling deprived—even if you are consuming plenty of calories—can trigger overeating. And making any food off-limits just increases its allure.

So if it's something sweet you're craving, go for it. One ounce of dark chocolate or 1/2 cup of vanilla ice cream clocks in 170 and 137 calories, respectively.

This might not be something you think about regularly, but your kitchen sponge can be a cesspool of bacteria, molds and yeast, according to a 2020 study in BMC Public Health . And some of these microbes can make you sick. Add to that, if you're using the sponge to wipe down your sink, kitchen counter, stove and refrigerator shelves, you're providing the perfect transportation for cross-contamination.

It's important to disinfect your sponge every day by microwaving it wet for two minutes and replacing it frequently—at least every two weeks.

Related Articles

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

A Multitasker’s Guide to Regaining Focus

We can’t really do more than one thing at a time, experts say. But these tactics can help.

By Anna Borges

Multitasking is just the way many of us live. How often do you text while stuck in traffic, lose track of a podcast while doing chores, or flutter between the news and your inbox?

“We get stuck in this multitasking trap even without realizing that we’re doing it,” said Nicole Byers, a neuropsychologist in Calgary, Alberta, who specializes in treating people with burnout.

There are a few reasons for our collective habit, she added. Most of us avoid boredom if we can, Dr. Byers explained, and multitasking is a reliable way to ward it off.

There’s also a lot of pressure to do it. “How many times have we seen a job posting that says, ‘Must be an excellent multitasker’?” she asked. “Our modern world — where so many of us spend most of the day on screens — really forces our brain to multitask.”

The fact remains that we’re not great at doing it, and it’s not great for us. But there are ways we can be smarter in our approach.

Your brain on multitasking

First, “multitask” itself is typically a misnomer. According to experts, it’s not possible to do two things at once — unless we can do one without much thinking (like taking a walk while catching up with a friend).

“Usually, when people think they’re multitasking, they’re actually switching their attention back and forth between two separate tasks,” said Gloria Mark, a professor of informatics at the University of California, Irvine, and author of “Attention Span: A Groundbreaking Way to Restore Balance, Happiness and Productivity.”