- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

autobiography

Definition of autobiography

Examples of autobiography in a sentence.

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'autobiography.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

auto- + biography , perhaps after German Autobiographie

1797, in the meaning defined above

Phrases Containing autobiography

- semi - autobiography

Dictionary Entries Near autobiography

autobiographist

Cite this Entry

“Autobiography.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/autobiography. Accessed 5 Apr. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of autobiography, more from merriam-webster on autobiography.

Thesaurus: All synonyms and antonyms for autobiography

Nglish: Translation of autobiography for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of autobiography for Arabic Speakers

Britannica.com: Encyclopedia article about autobiography

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

The tangled history of 'it's' and 'its', more commonly misspelled words, why does english have so many silent letters, your vs. you're: how to use them correctly, every letter is silent, sometimes: a-z list of examples, popular in wordplay, 12 bird names that sound like compliments, 10 scrabble words without any vowels, 12 more bird names that sound like insults (and sometimes are), 8 uncommon words related to love, 9 superb owl words, games & quizzes.

Autobiography

Definition of autobiography.

Autobiography is one type of biography , which tells the life story of its author, meaning it is a written record of the author’s life. Rather than being written by somebody else, an autobiography comes through the person’s own pen, in his own words. Some autobiographies are written in the form of a fictional tale; as novels or stories that closely mirror events from the author’s real life. Such stories include Charles Dickens ’ David Copperfield and J.D Salinger’s The Catcher in The Rye . In writing about personal experience, one discovers himself. Therefore, it is not merely a collection of anecdotes – it is a revelation to the readers about the author’s self-discovery.

Difference between Autobiography and Memoir

In an autobiography, the author attempts to capture important elements of his life. He not only deals with his career, and growth as a person, he also uses emotions and facts related to family life, relationships, education, travels, sexuality, and any types of inner struggles. A memoir is a record of memories and particular events that have taken place in the author’s life. In fact, it is the telling of a story or an event from his life; an account that does not tell the full record of a life.

Six Types of Autobiography

There are six types of autobiographies:

- Autobiography: A personal account that a person writes himself/herself.

- Memoir : An account of one’s memory.

- Reflective Essay : One’s thoughts about something.

- Confession: An account of one’s wrong or right doings.

- Monologue : An address of one’s thoughts to some audience or interlocuters.

- Biography : An account of the life of other persons written by someone else.

Importance of Autobiography

Autobiography is a significant genre in literature. Its significance or importance lies in authenticity, veracity, and personal testimonies. The reason is that people write about challenges they encounter in their life and the ways to tackle them. This shows the veracity and authenticity that is required of a piece of writing to make it eloquent, persuasive, and convincing.

Examples of Autobiography in Literature

Example #1: the box: tales from the darkroom by gunter grass.

A noble laureate and novelist, Gunter Grass , has shown a new perspective of self-examination by mixing up his quilt of fictionalized approach in his autobiographical book, “The Box: Tales from the Darkroom.” Adopting the individual point of view of each of his children, Grass narrates what his children think about him as their father and a writer. Though it is really an experimental approach, due to Grass’ linguistic creativity and dexterity, it gains an enthralling momentum.

Example #2: The Story of My Life by Helen Keller

In her autobiography, The Story of My Life , Helen Keller recounts her first twenty years, beginning with the events of the childhood illness that left her deaf and blind. In her childhood, a writer sent her a letter and prophesied, “Someday you will write a great story out of your own head that will be a comfort and help to many.”

In this book, Keller mentions prominent historical personalities, such as Alexander Graham Bell, whom she met at the age of six, and with whom she remained friends for several years. Keller paid a visit to John Greenleaf Whittier , a famous American poet, and shared correspondence with other eminent figures, including Oliver Wendell Holmes, and Mrs. Grover Cleveland. Generally, Keller’s autobiography is about overcoming great obstacles through hard work and pain.

Example #3: Self Portraits: Fictions by Frederic Tuten

In his autobiography, “Self Portraits: Fictions ,” Frederic Tuten has combined the fringes of romantic life with reality. Like postmodern writers, such as Jorge Luis Borges, and Italo Calvino, the stories of Tuten skip between truth and imagination, time and place, without warning. He has done the same with his autobiography, where readers are eager to move through fanciful stories about train rides, circus bears, and secrets to a happy marriage; all of which give readers glimpses of the real man.

Example #4: My Prizes by Thomas Bernhard

Reliving the success of his literary career through the lens of the many prizes he has received, Thomas Bernhard presents a sarcastic commentary in his autobiography, “My Prizes.” Bernhard, in fact, has taken a few things too seriously. Rather, he has viewed his life as a farcical theatrical drama unfolding around him. Although Bernhard is happy with the lifestyle and prestige of being an author, his blasé attitude and scathing wit make this recollection more charmingly dissident and hilarious.

Example #5: The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin by Benjamin Franklin

“The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin ” is written by one of the founding fathers of the United States. This book reveals Franklin’s youth, his ideas, and his days of adversity and prosperity. He is one of the best examples of living the American dream – sharing the idea that one can gain financial independence, and reach a prosperous life through hard work.

Through autobiography, authors can speak directly to their readers, and to their descendants. The function of the autobiography is to leave a legacy for its readers. By writing an autobiography, the individual shares his triumphs and defeats, and lessons learned, allowing readers to relate and feel motivated by inspirational stories. Life stories bridge the gap between peoples of differing ages and backgrounds, forging connections between old and new generations.

Synonyms of Autobiography

The following words are close synonyms of autobiography such as life story, personal account, personal history, diary, journal, biography, or memoir.

Related posts:

- The Autobiography of Malcolm X

Post navigation

How to Define Autobiography

Glossary of Grammatical and Rhetorical Terms

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

An autobiography is an account of a person's life written or otherwise recorded by that person. Adjective: autobiographical .

Many scholars regard the Confessions (c. 398) by Augustine of Hippo (354–430) as the first autobiography.

The term fictional autobiography (or pseudoautobiography ) refers to novels that employ first-person narrators who recount the events of their lives as if they actually happened. Well-known examples include David Copperfield (1850) by Charles Dickens and Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye (1951).

Some critics believe that all autobiographies are in some ways fictional. Patricia Meyer Spacks has observed that "people do make themselves up. . . . To read an autobiography is to encounter a self as an imaginative being" ( The Female Imagination , 1975).

For the distinction between a memoir and an autobiographical composition, see memoir as well as the examples and observations below.

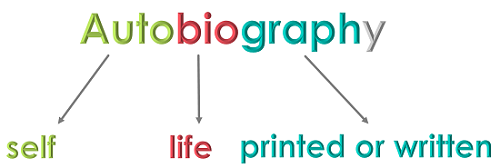

From the Greek, "self" + "life" + "write"

Examples of Autobiographical Prose

- Imitating the Style of the Spectator , by Benjamin Franklin

- Langston Hughes on Harlem

- On the Street, by Emma Goldman

- Ritual in Maya Angelou's Caged Bird

- The Turbid Ebb and Flow of Misery, by Margaret Sanger

- Two Ways of Seeing a River, by Mark Twain

Examples and Observations of Autobiographical Compositions

- "An autobiography is an obituary in serial form with the last installment missing." (Quentin Crisp, The Naked Civil Servant , 1968)

- "Putting a life into words rescues it from confusion even when the words declare the omnipresence of confusion, since the art of declaring implies dominance." (Patricia Meyer Spacks, Imagining a Self: Autobiography and Novel in Eighteenth-Century England . Harvard University Press, 1976)

- The Opening Lines of Zora Neale Hurston's Autobiography - "Like the dead-seeming, cold rocks, I have memories within that came out of the material that went to make me. Time and place have had their say. "So you will have to know something about the time and place where I came from, in order that you may interpret the incidents and directions of my life. "I was born in a Negro town. I do not mean by that the black back-side of an average town. Eatonville, Florida, is, and was at the time of my birth, a pure Negro town--charter, mayor, council, town marshal and all. It was not the first Negro community in America, but it was the first to be incorporated, the first attempt at organized self-government on the part of Negroes in America. "Eatonville is what you might call hitting a straight lick with a crooked stick. The town was not in the original plan. It is a by-product of something else. . . ." (Zora Neale Hurston, Dust Tracks on a Road . J.B. Lippincott, 1942) - "There is a saying in the Black community that advises: 'If a person asks you where you're going, you tell him where you've been. That way you neither lie nor reveal your secrets.' Hurston had called herself the 'Queen of the Niggerati.' She also said, 'I like myself when I'm laughing.' Dust Tracks on a Road is written with royal humor and an imperious creativity. But then all creativity is imperious, and Zora Neale Hurston was certainly creative." (Maya Angelou, Foreword to Dust Tracks on a Road , rpt. HarperCollins, 1996)

- Autobiography and Truth "All autobiographies are lies. I do not mean unconscious, unintentional lies; I mean deliberate lies. No man is bad enough to tell the truth about himself during his lifetime, involving, as it must, the truth about his family and friends and colleagues. And no man is good enough to tell the truth in a document which he suppresses until there is nobody left alive to contradict him." (George Bernard Shaw, Sixteen Self Sketches , 1898)" " Autobiography is an unrivaled vehicle for telling the truth about other people." (attributed to Thomas Carlyle, Philip Guedalla, and others)

- Autobiography and Memoir - "An autobiography is the story of a life : the name implies that the writer will somehow attempt to capture all the essential elements of that life. A writer's autobiography, for example, is not expected to deal merely with the author's growth and career as a writer but also with the facts and emotions connected to family life, education, relationships, sexuality, travels, and inner struggles of all kinds. An autobiography is sometimes limited by dates (as in Under My Skin: Volume One of My Autobiography to 1949 by Doris Lessing), but not obviously by theme. "Memoir, on the other hand, is a story from a life . It makes no pretense of replicating a whole life." (Judith Barrington, Writing the Memoir: From Truth to Art . Eighth Mountain Press, 2002) - "Unlike autobiography , which moves in a dutiful line from birth to fame, memoir narrows the lens, focusing on a time in the writer's life that was unusually vivid, such as childhood or adolescence, or that was framed by war or travel or public service or some other special circumstance." (William Zinsser, "Introduction," Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir . Mariner Books, 1998)

- An "Epidemical Rage for Auto-Biography" "[I]f the populace of writers become thus querulous after fame (to which they have no pretensions) we shall expect to see an epidemical rage for auto-biography break out, more wide in its influence and more pernicious in its tendency than the strange madness of the Abderites, so accurately described by Lucian. London, like Abdera, will be peopled solely by 'men of genius'; and as the frosty season, the grand specific for such evils, is over, we tremble for the consequences. Symptoms of this dreadful malady (though somewhat less violent) have appeared amongst us before . . .." (Isaac D'Israeli, "Review of "The Memoirs of Percival Stockdale," 1809)|

- The Lighter Side of Autobiography - "The Confessions of St. Augustine are the first autobiography , and they have this to distinguish them from all other autobiographies, that they are addressed directly to God." (Arthur Symons, Figures of Several Centuries , 1916) - "I write fiction and I'm told it's autobiography , I write autobiography and I'm told it's fiction, so since I'm so dim and they're so smart, let them decide what it is or isn't." (Philip Roth, Deception , 1990) - "I'm writing an unauthorized autobiography ." (Steven Wright)

Pronunciation: o-toe-bi-OG-ra-fee

- 6 Revealing Autobiographies by African American Thinkers

- Biographies: The Stories of Humanity

- 5 Writers of the Harlem Renaissance

- 42 Must-Read Feminist Female Authors

- Zora Neale Hurston

- 35 Zora Neale Hurston Quotes

- Point of View in Grammar and Composition

- How It Feels to Be Colored Me, by Zora Neale Hurston

- What Is a Personal Essay (Personal Statement)?

- Harlem Renaissance Women

- Quotes From Women in Black History

- 5 Leaders of the Harlem Renaissance

- 4 Publications of the Harlem Renaissance

- Men of the Harlem Renaissance

- Five African American Women Writers

- Literary Terms

- Autobiography

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Write Autobiography

I. What is Autobiography?

An autobiography is a self-written life story.

It is different from a biography , which is the life story of a person written by someone else. Some people may have their life story written by another person because they don’t believe they can write well, but they are still considered an author because they are providing the information. Reading autobiographies may be more interesting than biographies because you are reading the thoughts of the person instead of someone else’s interpretation.

II. Examples of Autobiography

One of the United States’ forefathers wrote prolifically (that means a lot!) about news, life, and common sense. His readings, quotes, and advice are still used today, and his face is on the $100 bill. Benjamin Franklin’s good advice is still used through his sayings, such as “We are all born ignorant, but one must work hard to remain stupid.” He’s also the one who penned the saying that’s seen all over many schools: “Tell me and I forget. Teach me and I remember. Involve me and I learn.” His autobiography is full of his adventures , philosophy about life, and his wisdom. His autobiography shows us how much he valued education through his anecdotes (stories) of his constant attempts to learn and improve himself. He also covers his many ideas on his inventions and his thoughts as he worked with others in helping the United States become free from England.

III. Types of Autobiography

There are many types of autobiographies. Authors must decide what purpose they have for writing about their lives, and then they can choose the format that would best tell their story. Most of these types all share common goals: helping themselves face an issue by writing it down, helping others overcome similar events, or simply telling their story.

a. Full autobiography (traditional):

This would be the complete life story, starting from birth through childhood, young adulthood, and up to the present time at which the book is being written. Authors might choose this if their whole lives were very different from others and could be considered interesting.

There are many types of memoirs – place, time, philosophic (their theory on life), occupational, etc. A memoir is a snapshot of a person’s life. It focuses on one specific part that stands out as a learning experience or worth sharing.

c. Psychological illness

People who have suffered mental illness of any kind find it therapeutic to write down their thoughts. Therapists are specialists who listen to people’s problems and help them feel better, but many people find writing down their story is also helpful.

d. Confession

Just as people share a psychological illness, people who have done something very wrong may find it helps to write down and share their story. Sharing the story may make one feel he or she is making amends (making things right), or perhaps hopes that others will learn and avoid the same mistake.

e. Spiritual

Spiritual and religious experiences are very personal . However, many people feel that it’s their duty and honor to share these stories. They may hope to pull others into their beliefs or simply improve others’ lives.

f. Overcoming adversity

Unfortunately, many people do not have happy, shining lives. Terrible events such as robberies, assaults, kidnappings, murders, horrific accidents, and life-threatening illnesses are common in some lives. Sharing the story can inspire others while also helping the person express deep emotions to heal.

IV. The Importance of Autobiography

Autobiographies are an important part of history. Being able to read the person’s own ideas and life stories is getting the first-person story versus the third-person (he-said/she-said) version. In journalism, reporters go to the source to get an accurate account of an event. The same is true when it comes to life stories. Reading the story from a second or third source will not be as reliable. The writer may be incorrectly explaining and describing the person’s life events.

Autobiographies are also important because they allow other people in similar circumstances realize that they are not alone. They can be inspiring for those who are facing problems in their lives. For the author, writing the autobiography allows them to heal as they express their feelings and opinions. Autobiographies are also an important part of history.

V. Examples of Autobiography in Literature

A popular autobiography that has lasted almost 100 years is that of Helen Keller. Her life story has been made into numerous movies and plays. Her teacher, Anne Sullivan, has also had her life story written and televised multiple times. Students today still read and learn about this young girl who went blind and deaf at 19 months of age, causing her to also lose her ability to learn to speak. Sullivan’s entrance into Helen’s life when the girl was seven was the turning point. She learned braille and soon became an activist for helping blind and deaf people across the nation. She died in 1968, but her autobiography is still helping others.

Even in the days before my teacher came, I used to feel along the square stiff boxwood hedges, and, guided by the sense of smell, would find the first violets and lilies. There, too, after a fit of temper, I went to find comfort and to hide my hot face in the cool leaves and grass. What joy it was to lose myself in that garden of flowers, to wander happily from spot to spot, until, coming suddenly upon a beautiful vine, I recognized it by its leaves and blossoms, and knew it was the vine which covered the tumble-down summer-house at the farther end of the garden! (Keller).

An autobiography that many middle and high school students read every year is “Night” by Elie Wiesel. His story is also a memoir, covering his teen years as he and his family went from the comfort of their own home to being forced into a Jewish ghetto with other families, before ending up in a Nazi prison camp. His book is not that long, but the details and description he uses brings to life the horrors of Hitler’s reign of terror in Germany during World War II. Students also read “The Diary of Anne Frank,” another type of autobiography that shows a young Jewish girl’s daily life while hiding from the Nazis to her eventual capture and death in a German camp. Both books are meant to remind us to not be indifferent to the world’s suffering and to not allow hate to take over.

“The people were saying, “The Red Army is advancing with giant strides…Hitler will not be able to harm us, even if he wants to…” Yes, we even doubted his resolve to exterminate us. Annihilate an entire people? Wipe out a population dispersed throughout so many nations? So many millions of people! By what means? In the middle of the twentieth century! And thus my elders concerned themselves with all manner of things—strategy, diplomacy, politics, and Zionism—but not with their own fate. Even Moishe the Beadle had fallen silent. He was weary of talking. He would drift through synagogue or through the streets, hunched over, eyes cast down, avoiding people’s gaze. In those days it was still possible to buy emigration certificates to Palestine. I had asked my father to sell everything, to liquidate everything, and to leave” (Wiesel 8).

VI. Examples of Autobiography in Pop Culture

One example of an autobiography that was a hit in the movie theaters is “American Sniper,” the story of Navy SEAL Chris Kyle. According to an article in the Dallas, Texas, magazine D, Kyle donated all the proceeds from the film to veterans and their families. He had a story to tell, and he used it to help others. His story is a memoir, focusing on a specific time period of his life when he was overseas in the military.

An autobiography by a young Olympian is “Grace, Gold and Glory: My Leap of Faith” by Gabrielle (Gabby) Douglas. She had a writer, Michelle Burford, help her in writing her autobiography. This is common for those who have a story to tell but may not have the words to express it well. Gabby was the darling of the 2012 Olympics, winning gold medals for the U.S. in gymnastics along with being the All-Around Gold Medal winner, the first African-American to do so. Many young athletes see her as an inspiration. Her story also became a television movie, “The Gabby Douglas Story.”

VII. Related Terms

The life story of one person written by another. The purpose may to be highlight an event or person in a way to help the public learn a lesson, feel inspired, or to realize that they are not alone in their circumstance. Biographies are also a way to share history. Historic and famous people may have their biographies written by many authors who research their lives years after they have died.

VIII. Conclusion

Autobiographies are a way for people to share stories that may educate, inform, persuade, or inspire others. Many people find writing their stories to be therapeutic, healing them beyond what any counseling might do or as a part of the counseling. Autobiographies are also a way to keep history alive by allowing people in the present learn about those who lived in the past. In the future, people can learn a lot about our present culture by reading autobiographies by people of today.

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

- Dictionaries home

- American English

- Collocations

- German-English

- Grammar home

- Practical English Usage

- Learn & Practise Grammar (Beta)

- Word Lists home

- My Word Lists

- Recent additions

- Resources home

- Text Checker

Definition of autobiography noun from the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary

autobiography

- In his autobiography, he recalls the poverty he grew up in.

- in an/the autobiography

Take your English to the next level

The Oxford Learner’s Thesaurus explains the difference between groups of similar words. Try it for free as part of the Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary app

Further Resources on Autobiography

ThoughtCo. shares some important points to consider before writing an autobiography .

The Living Handbook of Narratology delves into the history of the autobiography .

MasterClass breaks autobiography writing down into eight basic steps .

Pen & the Pad looks at the advantages and disadvantages of the autobiography .

Lifehack has a list of 15 autobiographies everyone should read at least once .

Related Terms

- Frame Story

- Point of View

- Daily Crossword

- Word Puzzle

- Word Finder

- Word of the Day

- Synonym of the Day

- Word of the Year

- Language stories

- All featured

- Gender and sexuality

- All pop culture

- Grammar Coach ™

- Writing hub

- Grammar essentials

- Commonly confused

- All writing tips

- Pop culture

- Writing tips

- autobiography

a history of a person's life written or told by that person.

Origin of autobiography

Other words from autobiography.

- au·to·bi·og·ra·pher, noun

Words Nearby autobiography

- autoantigen

- autobiographical

- auto caption

- autocatalysis

- autocatharsis

Dictionary.com Unabridged Based on the Random House Unabridged Dictionary, © Random House, Inc. 2024

How to use autobiography in a sentence

In so doing, she gave us an autobiography that has held up for more than a century.

His handwritten autobiography reawakens in Lee a longing to know her motherland.

His elocution, perfected on stage and evident in television and film, make X’s autobiography an easy yet informative listen.

The book is not so much an autobiography of Hastings — or even Netflix’s origin story.

By contrast, Shing-Tung Yau says in his autobiography that the Calabi-Yau manifold was given its name by other people eight years after he proved its existence, which Eugenio Calabi had conjectured some 20 years before that.

Glow: The autobiography of Rick JamesRick James David Ritz (Atria Books) Where to begin?

Hulanicki was the subject of a 2009 documentary, Beyond Biba, based on her 2007 autobiography From A to Biba.

And it was also during the phase of the higher autobiography .

“Nighttime was the worst,” Bennett wrote in his autobiography .

Then I picked up a book that shredded my facile preconceptions—Hard Stuff: The autobiography of Mayor Coleman Young.

No; her parents had but small place in that dramatic autobiography that Daphne was now constructing for herself.

His collected works, with autobiography , were published in 1865 under the editorship of Charles Hawkins.

But there is one point about the book that deserves some considering, its credibility as autobiography .

I thought you were anxious for leisure to complete your autobiography .

The smallest fragment of a genuine autobiography seems to me valuable for the student of past epochs.

British Dictionary definitions for autobiography

/ ( ˌɔːtəʊbaɪˈɒɡrəfɪ , ˌɔːtəbaɪ- ) /

an account of a person's life written or otherwise recorded by that person

Derived forms of autobiography

- autobiographer , noun

Collins English Dictionary - Complete & Unabridged 2012 Digital Edition © William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd. 1979, 1986 © HarperCollins Publishers 1998, 2000, 2003, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2009, 2012

Cultural definitions for autobiography

A literary work about the writer's own life. The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin and Isak Dinesen's Out of Africa are autobiographical.

The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, Third Edition Copyright © 2005 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Meaning of autobiography in English

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

- exercise book

- multi-volume

You can also find related words, phrases, and synonyms in the topics:

Related words

Autobiography | intermediate english, examples of autobiography, translations of autobiography.

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

the birds and the bees

the basic facts about sex and how babies are produced

Shoots, blooms and blossom: talking about plants

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- English Noun

- Intermediate Noun

- Translations

- All translations

Add autobiography to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

Find Study Materials for

- Business Studies

- Combined Science

- Computer Science

- Engineering

- English Literature

- Environmental Science

- Human Geography

- Macroeconomics

- Microeconomics

- Social Studies

- Browse all subjects

- Read our Magazine

Create Study Materials

As interesting as it may be writing about someone else's life, whether it be a fictional character's story or a non-fictional biography of someone you know, there is a different skill and enjoyment involved in sharing stories that are personal to you and showing others what it is like to experience life from your point of view.

Explore our app and discover over 50 million learning materials for free.

- Autobiography

- Explanations

- StudySmarter AI

- Textbook Solutions

- American Drama

- American Literary Movements

- American Literature

- American Poetry

- American Regionalism Literature

- American Short Fiction

- Literary Criticism and Theory

- Academic and Campus Novel

- Adventure Fiction

- African Literature

- Amatory Fiction

- Antistrophe

- Biblical Narrative

- Bildungsroman

- Blank Verse

- Children's Fiction

- Chivalric Romance

- Christian Drama

- Cliffhanger

- Closet drama

- Comedy in Drama

- Contemporary Fantasy

- Creative Non-Fiction

- Crime Fiction

- Cyberpunk Literature

- Detective Fiction

- Didactic Poetry

- Domestic Drama

- Dramatic Devices

- Dramatic Monologue

- Dramatic Structure

- Dramatic Terms

- Dramatis Personae

- Dystopian Fiction

- Elegiac Couplet

- English Renaissance Theatre

- Epic Poetry

- Epistolary Fiction

- Experimental Fiction

- Fantasy Fiction

- Feminist Literature

- Fictional Devices

- First World War Fiction

- Flash Fiction

- Foreshadowing

- Framed Narrative

- Free Indirect Discourse

- Genre Fiction

- Ghost Stories

- Gothic Novel

- Hard Low Fantasy

- Heroic Couplet

- Heroic Drama

- Historical Fantasy Fiction

- Historical Fiction

- Historical Romance Fiction

- Historiographic Metafiction

- Horatian Ode

- Horatian Satire

- Horror Novel

- Hyperrealism

- Iambic Pentameter

- Indian Literature

- Interleaving

- Internal Rhyme

- Intertextuality

- Irish Literature

- Limerick Poem

- Linear Narrative

- Literary Antecedent

- Literary Archetypes

- Literary Fiction

- Literary Form

- Literary Realism

- Literary Terms

- Literature Review

- Liturgical Dramas

- Lyric Poetry

- Magical Realism

- Malapropism

- Medieval Drama

- Metafiction

- Metrical Foot

- Miracle Plays

- Morality Plays

- Mystery Novels

- Mystery Play

- Narrative Discourse

- Narrative Form

- Narrative Literature

- Narrative Nonfiction

- Narrative Poetry

- Neo-Realism

- Non Fiction Genres

- Non-Fiction

- Non-linear Narrative

- Northern Irish Literature

- One-Act Play

- Oral Narratives

- Organic Poetry

- Pastoral Fiction

- Pastoral Poetry

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Petrarchan Sonnet

- Picaresque Novel

- Poetic Devices

- Poetic Form

- Poetic Genre

- Poetic Terms

- Political Satire

- Postcolonial Literature

- Prose Poetry

- Psychological Fiction

- Queer Literature

- Regency Romance

- Regional Fiction

- Religious Fiction

- Research Article

- Restoration Comedy

- Rhyme Scheme

- Roman a clef

- Romance Fiction

- Satirical Poetry

- Sceptical Literature

- Science Fiction

- Scottish Literature

- Second World War Fiction

- Sentimental Comedy

- Sentimental Novel

- Shakespearean Sonnet

- Short Fiction

- Social Realism Literature

- Speculative Fiction

- Spenserian Sonnet

- Stream of Consciousness

- Supernatural Fiction

- The Early Novel

- Theatre of the Absurd

- Theatrical Realism

- Tragedy in Drama

- Tragicomedy

- Translations and English Literature

- Urban Fiction

- Utopian Fiction

- Verse Fable

- Volta Poetry

- Welsh Literature

- Western Novels

- Women's fiction

- Literary Elements

- Literary Movements

- Literary Studies

- Non-Fiction Authors

Lerne mit deinen Freunden und bleibe auf dem richtigen Kurs mit deinen persönlichen Lernstatistiken

Nie wieder prokastinieren mit unseren Lernerinnerungen.

As interesting as it may be writing about someone else's life, whether it be a fictional character's story or a non-fictional biography of someone you know, there is a different skill and enjoyment involved in sharing stories that are personal to you and showing others what it is like to experience life from your point of view.

Many people hesitate to write accounts of their own life, in fear that their experiences are not worthy of attention or because it is too difficult to narrate one's own experiences. However, the truth is there is a much higher appreciation for self-written biographies, otherwise known as autobiographies. Let us look at the meaning, elements and examples of autobiography.

Autobiography Meaning

The word 'autobiography' is made of three words - 'auto' + 'bio' = 'graphy'

- The word 'auto" means 'self.'

- The word 'bio' refers to 'life.'

- The word 'graphy' means 'to write.'

Hence the etymology of the word 'autobiography' is 'self' + 'life' + 'write'.

'Autobiography' means a self-written account of one's own life.

Autobiography: An autobiography is a nonfictional account of a person's life written by the person themselves.

Writing an autobiography allows the autobiographer to share their life story in the way that they have personally experienced it. This allows the autobiographer to share their perspective or experience during significant events during their lifetime, which may differ from the experiences of other people. The autobiographer can also provide insightful commentary on the larger sociopolitical context in which they existed. This way, autobiographies form an important part of history because whatever we learn about our history today is from the recordings of those who experienced it in the past.

Autobiographies contain facts from the autobiographer's own life and are written with the intention of being as truthful as memory allows. However, just because an autobiography is a non-fictional narrative does not mean that it does not contain some degree of subjectivity in it. Autobiographers are only responsible for writing about events from their life, the way they have experienced them and the way they remember them. They are not responsible for showing how others may have experienced that very event.

Mein Kampf (1925) is the infamous autobiography of Adolf Hitler. The book outlines Hitler's rationale for carrying out the Holocaust (1941-1945) and his political perspectives on the future of Nazi Germany. While this does not mean that his perspective is factual or 'right', it is a truthful account of his experiences and his attitudes and beliefs.

A key to understanding the meaning of an autobiography is realising the difference between a biography and an autobiography.

A biography is an account of someone's life, written and narrated by someone else. Hence, in the case of a biography, the person whose life story is being recounted is not the author of the biography.

Biography: A written account of someone's life written by someone else.

Meanwhile, an autobiography is also an account of someone's life but written and narrated by the very same person whose life is being written about. In this case, the person on who the autobiography is based is also the author.

Therefore, while most biographies are written from the second or third-person perspective, an autobiography is always narrated with a first-person narrative voice. This adds to the intimacy of an autobiography, as readers get to experience the autobiographer's life from their eyes - see what they saw and feel what they felt.

Here is a table summarising the difference between a biography and an autobiography:

Autobiography Elements

Most autobiographies do not mention every detail of a person's life from birth to death. Instead, they select key touchstone moments that shaped the autobiographer's life. Here are some of the essential elements that most autobiographies are made of:

This could include information regarding the autobiographer's date and place of birth, family and history, key stages in their education and career and any other relevant factual details that tell the reader more about the writer and their background.

- Early experiences

This includes significant moments in the autobiographer's life that shaped their personality and their worldview. Sharing these with the readers, their thoughts and feelings during this experience and what lesson it taught them helps the readers understand more about the writer as a person, their likes and dislikes and what made them the way they are. This is usually how autobiographers connect with their readers, by either bringing forth experiences that the reader may identify with or by imparting them an important life lesson.

Many autobiographers dwell on their childhood, as that is a stage in life that particularly shapes people the most. This involves narrating key memories that the autobiographer may still remember about their upbringing, relationships with family and friends, and their primary education.

Professional life

Just as writing about one's childhood is a key area of focus in autobiographies, so are stories from an autobiographer's professional life. Talking about their successes and their progression in their chosen industry serves as a huge source of inspiration for those aspiring to go down the same career pathway. In contrast, stories of failures and injustices may serve to both warn the reader and motivate them to overcome these setbacks.

The HP Way (1995) is an autobiography by David Packard that details how he and Bill Hewlett founded HP, a company that began in their garage and ended up becoming a multi-billion technological company. Packard details how their management strategies, innovative ideas and hard work took their company towards growth and success. The autobiography serves as an inspiration and a guidebook for entrepreneurs in every field.

- Overcoming adversity

As mentioned above, autobiographers often delve into stories of their life's failures and how they dealt with this setback and overcame it.

This is not only to inspire sympathy from their readers but also to inspire those facing similar problems in their lives. These 'failures' could be in their personal and professional lives.

Stories of failure could also be about overcoming adversities in life. This could be recovering from a mental illness, accidents, discrimination, violence or any other negative experience. Autobiographers may wish to share their stories to heal from their experiences.

I Am Malala (2013) by Malala Yousafzai is the story of how Malala Yousafzai, a young Pakistani girl, got shot by the Taliban at the age of 15 for protesting for female education. She became the world's youngest Nobel Peace Prize laureate in 2014 and remains an activist for women's right to education.

Talking about culture involves discussions about the autobiographer's way of life. This means delving into their values and beliefs, traditions, customs, rituals and holidays that are practised by them and their family, the writer's language, food and clothing preferences and anything that may be 'normal' for the autobiographer, but unique to readers who do not belong to that culture.

This particular element also allows for identification, amongst people who belong to the same culture as the autobiographer, but also allows for an appreciation of diverse cultures.

Out of Africa (1937) is an autobiography by Karen Blizen where she details her life on a coffee plantation from 1914 to 1931 in Kenya, which was under British Empire at the time. It provides a picture of what life looked like during colonial rule in Africa.

Autobiographers often have a common theme or lesson running across the stories they have selected to include in their autobiographies. This is especially true for memoirs, a specific type of autobiography we will discuss in the next section.

On Writing (2000) is a memoir by American author Stephen King that is a collection of King's experiences as a writer. Hence, the underlying theme under all the experiences and events that he includes in this memoir either have had a profound impact on his writing career or serve as inspiration for aspiring writers.

Types of Autobiographies

Now that we have looked at the elements that make up an autobiography, let's look at the different types of self-written work that possess all the abovementioned elements.

- Traditional autobiographies

This is when an autobiographer chronicles their entire lifetime, starting from their birth and early childhood, all the way to the present time when the book is being written. Most autobiographers opt for a chronological structure while narrating, although this is not necessary. While not each and every moment starting from the day of their birth needs to be included, the autobiographer must delve into any formative events occurring throughout the entire course of their life.

My Life (2004) is an autobiography by former U.S. President Bill Clinton chronicling his life, beginning with his childhood in Arkansas and then covering his tenure as the president of the United States.

Memoirs are a type of autobiography where the autobiographer only zooms in on particular memories that are significant or special to the author. Hence, memoirs are usually collections of memories handpicked by the author from their own life.

The memories that are selected are usually bound by a common theme.

autobiography is a story of a life; memoir is a story from a life. 1

Eat, Pray, Love (2006) is a collection of memoirs by Elizabeth Gilbert who writes about her various experiences while travelling across Italy, India and Indonesia, and the lessons she learnt along the way.

Fictionalised autobiographies

Remember when we said that autobiographies are always non-fictional? Well, there are some autobiographers who blur the lines between fiction and non-fiction while writing an autobiography!

While the events taking place in the autobiography are from the author's real life, the author may decide to use fictional characters to represent their actual experiences. Or, sometimes, an author may create a fictional character with a fictional story, but choose to narrate it like it is an autobiography by recording made-up (but very believable) facts about the character and tracing their psychological and social development throughout the course of their life. Sometimes, the author is so skilled at autobiographical writing, that readers are hardly able to tell that the protagonist and the life they are reading about are fictional!

Charles Dickens took an autobiographical approach while writing David Copperfield (1849), a novel where the substance of the book comes from Dickens' own life. However, the novel has been written in the first-person narrative voice of David Copperfield, who is a fictional character who also happens to be the protagonist of the story. Dickens reproduces his own life t hrough the story of David, a character that is a reflection of Dickens as a person.

- Spiritual autobiographies

These autobiographies focus on the autobiographer's journey towards finding their faith and spirituality. It usually follows the narrative of the writer lacking faith or having lived a sinful youth. However, after numerous cycles of struggles, doubts, and repenting, the writer reconnects with their faith and undergoes a spiritual awakening.

Throughout the autobiography, the autobiographer shares stories of this conversion and attempts to spread God's message.

Left To Tell (2006) by Immaculée Ilibagiza is an autobiography where Ilibagiza details the story of her surviving the Rwandan Holocaust by hiding in a pastor's bathroom. She survives the genocide by possessing faith and trust, and by eventually learning to forgive those who murdered her family and friends.

Confessional autobiographies are written by people who usually have a hidden secret or a personal revelation that they wish to reveal. Some autobiographers have dark and painful secrets that they wish to share in order to seek redemption or to warn others from doing the same.

This could be anything from stories of struggling with addiction to committing a crime - anything that the autobiographer has been plagued with and wishes to get off their chest.

Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1821) narrates Thomas Quincy's struggle with drug addiction and the influence this has had on his life. He narrates instances from his childhood that acted as emotional factors leading to his addiction, the nightmares and visions he would have under the influence of the drug and even a contrasting picture of the allure of the drug and the pleasure and euphoria it affords. This is an extract from his autobiography:

The sense of space, and in the end, the sense of time, were both powerfully affected. Buildings, landscapes, &c. were exhibited in proportions so vast as the bodily eye is not fitted to conceive. Space swelled, and was amplified to an extent of unutterable infinity. This, however, did not disturb me so much as the vast expansion of time; I sometimes seemed to have lived for 70 or 100 years in one night; nay, sometimes had feelings representative of a millennium passed in that time, or, however, of a duration far beyond the limits of any human experience. ( pp. 103–104.)

Autobiography Books

Now let us look at a few famous examples of autobiographies.

The Story of My Life (1903) by Hellen Keller

In her autobiography, Hellen Keller details her struggles and journey following her blindness and deafness at a very young age. She describes her relationship with her teacher and life-long companion Anne Sullivan, who taught her how to cope and learn from her disability and enjoy life once again. She talks about her many adventures with Anne Sullivan, who taught her to appreciate nature and reading and built Hellen's confidence and determination. After overcoming several obstacles, Hellen grows up to become a successful and well-educated woman and is able to achieve all her dreams by the end of the novel.

This is a collection of diary entries written by Anne Frank from 1942 to 1944, where she details her life as a Jewish girl hiding from the Nazis in Nazi-occupied Amsterdam. She describes the two years she spent writing and studying in the Annex, a small refuge for her family and other Jewish people fleeing persecution. Anne's diary halts when the Annex is raided by the Nazis after which she and her family are sent to concentration camps. She died of typhus in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in 1945, and her diary is one of the most poignant accounts of the horrors of the Holocaust.

This is an extract from one of her diary entries from October 9th, 1942:

Escape is almost impossible; many people look Jewish, and they’re branded by their shorn heads. If it’s that bad in Holland, what must it be like in those faraway and uncivilised places where the Germans are sending them? We assume that most of them are being murdered. The English radio says they’re being gassed. Perhaps that’s the quickest way to die. I feel terrible. Miep’s accounts of these horrors are so heartrending… Fine specimens of humanity, those Germans, and to think I’m actually one of them! No, that’s not true, Hitler took away our nationality long ago. And besides, there are no greater enemies on earth than the Germans and Jews.

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969) by Maya Angelou

This autobiography is the first volume of a seven-volume autobiographical series written by Maya Angelou. It details her early life in Arkansas and her traumatic childhood where she was subjected to sexual assault and racism. The autobiography then takes us through each of her multiple careers as a poet, teacher, actress, director, dancer, and activist, and the injustices and prejudices she faces along the way as a black woman in America.

Autobiography - Key takeaways

- An autobiography is a nonfictional account of a person's life, written by the person themselves.

- A biography is a written account of someone's life written by someone else, whereas an autobiography is a self-written account of one's own life story.

- Key background information

- Professional Life

Fictional autobiographies

- Confessions

The Diary of a Young Girl (1947) by Anne Frank

- Judith Barrington. 'Writing the Memoir'. The Handbook of Creative Writing . 2014

- Fig. 1 - Adolf Hitler cropped restored (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Adolf_Hitler_cropped_restored.jpg) by Unknown Author is licensed by Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 de (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)

- Fig. 2 - Malala Yousafzai at Girl Summit 2014 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Malala_Yousafzai_at_Girl_Summit_2014.jpg) by Russell Watkins/Department for International Development is licensed by Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/)

- Fig. 3 - Public domain: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Angelou_at_Clinton_inauguration_(cropped_2).jpg

Frequently Asked Questions about Autobiography

--> what are some examples of autobiography.

Some notable examples of autobiographies are:

--> What does autobiography mean?

An autobiography is a nonfictional account of a person's life, written by the person themselves.

--> What should I write in an autobiography?

While writing an autobiography, include key background information about you and your family, early experiences from your childhood, your culture, your professional life, stories of adversity and any other touchstone moments that shaped your life.

--> What is the difference between biography and autobiography?

A biography is a written account of someone's life by someone else, whereas an autobiography is a self-written account of one's own life story.

--> What are the different types of autobiographies?

The types of autobiographies are:

Define an autobiography.

An autobiography is a nonfictional account of a person's life, written by the person themselves.

What is the difference between an autobiography and a biography?

A biography is a written account of someone's life by someone else, whereas an autobiography is a self-written account of one's own life story.

Which type of autobiography includes fictional elements?

Which narrative voice are autobiographies written in?

First-person narrative voice

Which of the following autobiographies were written about the Holocaust?

What is a memoir?

A memoir is a type of autobiography where the writer zooms in on a particular collection of memories that are significant or special to the author.

Learn with 10 Autobiography flashcards in the free StudySmarter app

Already have an account? Log in

- Literary Devices

of the users don't pass the Autobiography quiz! Will you pass the quiz?

How would you like to learn this content?

Free english-literature cheat sheet!

Everything you need to know on . A perfect summary so you can easily remember everything.

Join over 22 million students in learning with our StudySmarter App

The first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

- Flashcards & Quizzes

- AI Study Assistant

- Study Planner

- Smart Note-Taking

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

This is still free to read, it's not a paywall.

You need to register to keep reading, create a free account to save this explanation..

Save explanations to your personalised space and access them anytime, anywhere!

By signing up, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and the Privacy Policy of StudySmarter.

Entdecke Lernmaterial in der StudySmarter-App

Privacy Overview

Become a Bestseller

Follow our 5-step publishing path.

Fundantals of Fiction & Story

Bring your story to life with a proven plan.

Market Your Book

Learn how to sell more copies.

Edit Your Book

Get professional editing support.

Author Advantage Accelerator Nonfiction

Grow your business, authority, and income.

Author Advantage Accelerator Fiction

Become a full-time fiction author.

Author Accelerator Elite

Take the fast-track to publishing success.

Take the Quiz

Let us pair you with the right fit.

Free Copy of Published.

Book title generator, nonfiction outline template, writing software quiz, book royalties calculator.

Learn how to write your book

Learn how to edit your book

Learn how to self-publish your book

Learn how to sell more books

Learn how to grow your business

Learn about self-help books

Learn about nonfiction writing

Learn about fiction writing

How to Get An ISBN Number

A Beginner’s Guide to Self-Publishing

How Much Do Self-Published Authors Make on Amazon?

Book Template: 9 Free Layouts

How to Write a Book in 12 Steps

The 15 Best Book Writing Software Tools

What is an Autobiography? Definition, Elements, and Writing Tips

POSTED ON Oct 1, 2023

Written by Audrey Hirschberger

What is an autobiography, and how do you define autobiography, exactly? If you’re hoping to write an autobiography, it’s an important thing to know. After all, you wouldn’t want to mislabel your book.

What sets an autobiography apart from a memoir or a biography? And what type of writing is most similar to an autobiography? Should you even write one? How? Today we will be discussing all things autobiographical, so you can learn what an autobiography is, what sets it apart, and how to write one of your own – should you so choose.

But before we get into writing tips, we must first define autobiography. So what is an autobiography, precisely?

Need A Nonfiction Book Outline?

This Guide to Autobiographies Contains Information On:

What is an autobiography: autobiography meaning defined.

What is an autobiography? It’s a firsthand recounting of an author’s own life. So, if you were to write an autobiography, you would be writing a true retelling of your own life events.

Autobiography cannot be bound to only one type of work. What an autobiography is has more to do with the contents than the format. For example, autobiographical works can include letters, diaries, journals, or books – and may not have even been meant for publication.

An autobiography is what many celebrities, government officials, and important social figures sit down to write at the end of their lives or distinguished careers.

Of course, the work doesn’t have to cover your whole life. You can absolutely write an autobiography in your 20s or 30s if you’ve lived through events worth sharing!

If an autobiography doesn’t cover the entire lifespan of the author, it can start to get confused with another genre of writing. So what’s an autobiography most similar to? And how can you tell it apart from other genres of writing? Let’s dive into the details.

What type of writing is most similar to an autobiography?

A memoir is undoubtedly what type of writing is most similar to an autobiography. So what is the difference between an autobiography vs memoir ?

Simply put, a memoir is a book that an author writes about their own life with the intention of communicating a lesson or message to the reader. It doesn’t need to be written in chronological order, and only contains pieces of the author’s life story.

An autobiography, on the other hand, is the author’s life story from birth to present, and it’s much less concerned with theme than it is with communicating a “highlight reel” of the author’s biggest life events.

In addition to memoirs, there is also some confusion between autobiography vs biography . A biography is a true story about someone’s life, but it is not about the author’s life.

Is an autobiography always nonfiction?

When many people define autobiography, they say it is a true or “nonfiction” telling of an author’s life – but that’s not always the case.

There is actually such a thing as autobiographical fiction .

Autobiographical fiction refers to a story that is based on fact and inspired by the author’s actual experiences…but has made-up characters or events. Any element in the story can be embellished upon or fabricated.

Even the information in a standard “nonfiction” autobiography should be taken with a grain of salt. After all, anything written from the author’s perspective may contain certain biases, distortions, or unconscious omissions within the text.

So if being nonfiction isn’t a defining characteristic of an autobiography, what is an autobiography defined by?

The key elements of an autobiography

What’s an autobiography like from cover to cover? It should contain these key elements:

- A personal narrative : It is a firsthand account of the author's life experiences.

- A chronological structure : An autobiography typically follows a chronological order, tracing the author's life from birth to present.

- Reflection and insight : The book should contain the author's reflections, insights, and emotions about key life events.

- Key life events : The book should highlight significant events, milestones, and challenges in the author's life.

- Setting and context : There should be descriptions of the time period, cultural background, and environment to help the reader understand the author’s life.

- Authenticity : The author should be honest and sincere in presenting their life story.

- A personal perspective : An autobiography is written from the author's unique point of view.

- A strong conclusion : The ending of the book should reflect on the author's current state or outlook.

Famous Autobiography Examples

Now that you know what an autobiography is, let’s look at some famous autobiography examples .

The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank (1947)

Perhaps no autobiography is more famous than The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank. Her diary chronicles her profound thoughts, dreams, and fears as she hides with her family in the walls during the Holocaust.

Anne's words resonate with the enduring spirit of hope amid unimaginable darkness.

The Autobiography of Ben Franklin by Benjamin Franklin (1909)

Benjamin Franklin's autobiography follows Franklin’s life from humble origins to one of America's greatest forefathers. While originally intended as a collection of anecdotes for his son, this autobiography has become one of the most famous works of American literature.

Long Walk to Freedom by Nelson Mandela (1994)

Long Walk to Freedom narrates Nelson Mandela's epic odyssey from South African prisoner to revered statesman. This masterpiece of an autobiography is a portrait of resilience against the backdrop of apartheid – and his words are a bastion for courage and human rights.

Now you know what an autobiography is, and some examples of successful autobiographies, so it’s time to discuss what goes into actually writing one.

Who Should Write an Autobiography?

Celebrity autobiographies are popular for a reason – the people who wrote them were already popular.

The main purpose of an autobiography is to portray the life experiences and achievements of the author. If you haven’t made any massive achievements that people are already aware of, an autobiography might not be for you. Instead, you should learn how to write a memoir .

After all, what’s an autobiography worth if no one reads it?

If you have made an important contribution to society, or have amassed a massive following of fans, then writing an autobiography could be a fabulous idea.

An autobiography is what allows you to claim your rightful place in history. It provides a legacy for your life, helps you to better understand your life’s journey, and can even be deeply therapeutic to write.

But then comes the next problem: how to write an autobiography.

Tips on Writing Your Own Autobiography

While memoirs are the books that teach life lessons, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t give your autobiography meaning. The best autobiographies paint a vivid tapestry of personal growth and introspection.

You don’t just want to tell the reader about your life – you want them to feel like they are living it with you.

And it’s not just about painting a picture with your prose. A lot of thought should go into everything from autobiography titles to page count. To get started, here are five tips for writing an autobiography:

- Know your audience : Understand who will read your autobiography and speak to them while writing.

- Be candid and authentic : A life seen through rose-colored glasses isn’t relatable. You should include your failures as well as your triumphs, and humanize yourself so your story resonates with your reader.

- Do your research : Of course you know what happened in your life, but how many details do you actually remember? You may need to sift through photos, archives, and diaries – and interview people close to you. Consider adding the photos to your book.

- Identify key themes : Identify key events and life lessons that have shaped you. Reflect on how these themes have evolved over time.

- Edit and edit again : Write freely first, then edit rigorously. Seek feedback from trusted individuals and consider professional editing to ensure clarity and coherence in your narrative. NO ONE writes perfectly the first time.

So there you have it, you are well on your way to understanding (and writing) an autobiography.

If you'd still like more guidance for writing your autobiography, you can check out our free autobiography template . We can’t wait for you to share your life story with the world.

FREE BOOK OUTLINE TEMPLATE

100% Customizable For Your Manuscript.

Related posts

Business, Non-Fiction

How to Get More Patients With a Book & Brand

Non-Fiction

The Only (FREE) Autobiography Template You Need – 4 Simple Steps

How to write a biography: 10 step guide + book template.

- Subscriber Services

- For Authors

- Publications

- Archaeology

- Art & Architecture

- Bilingual dictionaries

- Classical studies

- Encyclopedias

- English Dictionaries and Thesauri

- Language reference

- Linguistics

- Media studies

- Medicine and health

- Names studies

- Performing arts

- Science and technology

- Social sciences

- Society and culture

- Overview Pages

- Subject Reference

- English Dictionaries

- Bilingual Dictionaries

Recently viewed (0)

- Save Search

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Related Content

Related overviews.

St Augustine (354—430) Doctor of the Church

Benjamin Franklin (1706—1790) natural philosopher, writer, and revolutionary politician in America

Anne Bradstreet (c. 1612—1672) poet

See all related overviews in Oxford Reference »

More Like This

Show all results sharing this subject:

autobiography

Quick reference.

In its modern form, may be taken as writing that purposefully and self‐consciously provides an account of the author's life and incorporates feeling and introspection as well as empirical detail. In this sense, autobiographies are infrequent in English much before 1800. Although there are examples of autobiography in a quasi‐modern sense earlier than this (e.g. Bunyan's conversion narrative, Grace Abounding, 1666, and Margaret Cavendish', duchess of Newcastle's ‘A True Relation’, 1655–6) it is not until the early 19th cent. that the genre becomes established in English writing: Gibbon's Memoirs (1796) are a notable exception.

From 1800 onwards the introspective Protestantism of an earlier period and the Romantic Movement's displeasure with the fact/feeling distinction of the Enlightenment provided for personal narratives of a largely new kind. They were characterized by a self‐scrutiny and vivid sentiment that produced what is now referred to, following Robert Southey (1809), as autobiography . Early in the 19th cent. Wordsworth gives in The Prelude (1805) a sustained reflection upon the circumstances of he himself being the subject of his own work; and in the second half of the century Newman in his Apologia pro Vita Sua (1864) publicly and originally reveals a personal spiritual journey. This latter, with its public disclosure of the private domain, had a dramatic and far‐reaching influence upon the intelligentsia of late Victorian society.

In the 20th cent. autobiography became increasingly valued not so much as an empirical record of historical events but as providing an epitome of personal sensibility among the intricate vicissitudes of cultural change. Vera Brittain achieved a seriousness of observation and affect to provide in Testament of Youth (1933) a major work on the conduct of the First World War. In the area of more domestic but no less social concerns J. R. Ackerley in his My Father and Myself (1968) constructed an autobiography of painful frankness in a disquisition upon his unusual family relations, his affection for his dog, and the tribulations of his homosexuality. More recently Tim Lott in The Scent of Dead Roses (1996) discussed the suicide of his mother and amalgamated autobiography, family history, and social analysis in a virtuoso performance of control and pathos. The truthfulness or not of autobiography is essentially a matter that must be left to biographers and philosophers. The plausibility of an autobiography, however, must find its authentication by the degree to which it can correspond to some approximation of its context.

From: autobiography in The Concise Oxford Companion to English Literature »

Subjects: Literature

Related content in Oxford Reference

Reference entries, autobiography.

View all reference entries »

View all related items in Oxford Reference »

Search for: 'autobiography' in Oxford Reference »

- Oxford University Press

PRINTED FROM OXFORD REFERENCE (www.oxfordreference.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2023. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single entry from a reference work in OR for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice ).

date: 05 April 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|162.248.224.4]

- 162.248.224.4

Character limit 500 /500

- Skip to search box

- Skip to main content

Princeton University Library

His 414: life-writing and history: diaries, memoirs and autobiographies.

- Where to Begin

Recent Works from the Library's Collection

- Finding Autobiographies in the Library

- Finding and Retrieving Memoirs in Special Collections

- Finding Life Writing Online

- << Previous: Where to Begin

- Next: Finding Autobiographies in the Library >>

- Last Updated: Dec 15, 2023 4:16 PM

- URL: https://libguides.princeton.edu/HIS414

What Is an Autobiography? Definition & 50+ Examples

Have you ever wondered what goes on behind the scenes in the lives of your favorite icons? Autobiographies offer us an intimate glimpse into the minds and hearts of those who’ve walked extraordinary paths.

These firsthand accounts of personal triumphs, challenges, and wisdom acquired along the way, illuminate the human experience in a profound and often surprising manner.

Join us as we journey through the pages of these literary treasures, unearthing the secrets that make them so compelling.

Table of Contents

Definition of Autobiography

An autobiography is a type of non-fiction writing that provides a firsthand account of a person’s life. The author recounts their own experiences, thoughts, emotions, and insights, often focusing on how these events have shaped their life. Typically structured around a chronological narrative, an autobiography provides a window into the author’s world

While autobiographies may be written for various reasons, including preserving personal history or sharing an inspiring story with others, they all aim to provide a genuine account of the author’s life.

Autobiographies can include stories of personal growth, challenges overcome, successes achieved, and important relationships. They often cover topics such as childhood, family life, education, career, personal struggles, and life-changing experiences.

It can portray both ordinary and extraordinary lives, allowing readers to connect with the author’s experiences and gain insights into their personal journeys.

Historical Overview

Autobiographies have a rich history, stemming from ancient times to the present day.

Early Examples

One of the earliest known examples of an autobiography is Augustine of Hippo’s “Confessions,” written in the 4th century AD. This seminal work is not only an important milestone in the development of the genre but also a deeply introspective and spiritual account of Augustine’s life and faith.

Born in 354 AD in Thagaste, Roman North Africa (modern-day Algeria), Augustine of Hippo was a Christian theologian and philosopher who became one of the most influential figures in the development of Western Christianity.

His “Confessions” were written between 397 and 400 AD, primarily as a testimony of his own personal conversion and growth in faith. The work is considered to be both a literary masterpiece and a foundational text in Christian theology.

Divided into thirteen books, the “Confessions” follows Augustine’s life chronologically, beginning with his childhood and progressing through his adolescence, early adulthood, and eventual conversion to Christianity.

The “Confessions” has been widely regarded as a groundbreaking work that laid the foundation for the autobiographical genre in Western literature. Its introspective and self-reflective style has influenced countless authors over the centuries, including Jean-Jacques Rousseau, John Henry Newman, and Thomas Merton.

Development Through the Centuries

By the early modern period, autobiographies became more widespread, with some of the best-known examples including:

- Saint Teresa of Avila’s “The Life of Saint Teresa of Avila by Herself” chronicling the 15th-century Spanish mystic and Carmelite nun’s spiritual relationship with God.

- “The True Travels, Adventures, and Observations of Captain John Smith” of John Smith in 16th-century, which recounts his experiences in the early days of the Virginia Colony and his encounters with Native Americans.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the genre continued to develop, with unique works such as:

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s “Confessions”

- Mary Wollstonecraft’s “Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden “

- Frederick Douglass’ “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave”

These important texts highlighted personal experiences, struggles, and social issues, shaping the autobiographical genre into what we recognize today.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, autobiographies span a wide range of themes and voices, including globally renowned works such as:

- Anne Frank’s “The Diary of a Young Girl”

- Nelson Mandela’s “Long Walk to Freedom”

These works demonstrate how the genre has evolved to encompass diverse perspectives and life experiences.

Elements of an Autobiography

An autobiography contains several key elements that help readers understand the life story of the author.

Chronological Order

Chronological order is a common structure used in autobiographies as it allows readers to follow the author’s life events in a linear sequence. This format provides a clear and organized presentation of the author’s experiences and life stages, making it easier for the reader to follow and understand.

One of the primary benefits of using a chronological structure in an autobiography is that it mirrors the natural progression of a person’s life.

As readers move through the narrative, they can witness the author’s growth, the various influences that shaped them, and the crucial turning points that led to significant changes in their lives. This progression allows for a comprehensive understanding of the author’s personal journey and evolution.

Moreover, a chronological order in autobiographies can help to contextualize the author’s experiences within broader historical and cultural events.

By situating their lives within a specific time frame, authors can provide readers with a deeper understanding of the social, political, and cultural forces that influenced their experiences and decisions. This context helps to illuminate the unique circumstances and challenges faced by the author, as well as the ways in which their lives intersected with larger societal trends and issues.

First-Person Perspective

Autobiographies are written in first-person perspective, using “I” statements, as a means of conveying the author’s personal journey through their own eyes. This technique allows the author to provide personal insights, emotions, and opinions, creating a stronger connection between the reader and the author’s personal experiences.