Essay Writing: Essay Writing Basics

- Essay Writing Basics

- Purdue OWL Page on Writing Your Thesis This link opens in a new window

- Paragraphs and Transitions

- How to Tell if a Website is Legitimate This link opens in a new window

- Formatting Your References Page

- Cite a Website

- Common Grammatical and Mechanical Errors

- Additional Resources

- Proofread Before You Submit Your Paper

- Structuring the 5-Paragraph Essay

Basic Essay Format

Please Note : These guidelines are general suggestions. When in doubt, please refer to your assignment for specifics.

Most essays consist of three parts:

- the introduction (one paragraph);

- the body (usually at least three paragraphs), and

- the conclusion (one paragraph).

Minimum of 5 paragraphs total

Standard Parts of an Essay

Introduction paragraph (including the thesis statement ).

Begin your paper by introducing your topic.

Parts of an Introduction paragraph:

- “I danced so much at my birthday party; my feet are killing me!”

- “The surprise birthday party my friends gave me was amazing.”

- “I was so glad that the party remained a secret; my friends from the old neighborhood were there, and most surprisingly, I didn’t know I could still dance so much.”

Be sure your Introduction makes a clear, general point, which you can back up with specifics as you lead to your Thesis Statement.

Thesis Statement

The final sentence in your Introduction paragraph should be your Thesis Statement: a single, clear, and concise sentence stating your essay’s main idea or argument .

According to Denis Johnson of the Rasmussen College Library , you should t hink of a thesis statement as one complete sentence that expresses your position or tells your story in a nutshell .

The Thesis Statement should always take a stand and justify further discussion .

3 or More Body Paragraphs (and using Transitions )

Now use the Body of your essay to support the main points you presented in your Thesis Statement. Develop each point using one or more paragraphs, and support each point with specific details . Your details may come from research or your direct experience. Refer to your assignment for required supporting documentation (APA citations.) Your analysis and discussion of your topic should tie your narrative together and draw conclusions supporting your thesis.

Use effective transition words and phrases to give your paper “flow,” to connect your ideas, and to move from one supporting statement to another.

Conclusion Paragraph

- “The surprise party my friends had for me was a great reminder of the good old days. It was a wonderful surprise seeing old friends again and have fun like we did when we were younger. My feet will never be the same again.”

Use your conclusion to restate and consolidate all the main points of your essay. You should first restate your Thesis Statement (using slightly different phrasing this time). Give closure to your essay by resolving any outstanding points and leaving your readers with a final thought regarding your argument's future or long-term implications. Your Conclusion is not the place to introduce new ideas or topics that did not appear earlier in your paper.

Don’t forget to cite each source of information you use - using In-Text Citations throughout your paper and a References page at the end. Use these LibGuides to help you with your In-Text Citations and References page.

(Sample Essay excerpts and instructions, thanks to Professor Deborah Ashby: Monroe College, Department of Social Sciences)

A Monroe College Research Guide

THIS RESEARCH OR "LIBGUIDE" WAS PRODUCED BY THE LIBRARIANS OF MONROE COLLEGE

- Next: Choosing/Narrowing Your Topic >>

- Last Updated: Jan 24, 2024 11:23 AM

- URL: https://monroecollege.libguides.com/essaywriting

- Research Guides |

- Databases |

Talk to our experts

1800-120-456-456

- Essay Writing

Introduction

In the simplest terms, an essay is a short piece of writing which is set around a specific topic or subject. The piece of writing will give information surrounding the topic but will also display the opinions and thoughts of the author. Oftentimes, an essay is used in an academic sense by way of examination to determine whether a student has understood their studies and as a way of testing their knowledge on a specific subject. An essay is also used in education as a way of encouraging a student to develop their writing skills.

Moreover; an essay is a focused piece of writing designed to inform or persuade. There are many different types of essays, but they are often defined in four categories: argumentative, expository, narrative, and descriptive essays. Argumentative and expository essays are focused on conveying information and making clear points, while narrative and descriptive essays are about exercising creativity and writing in an interesting way. At the university level, argumentative essays are the most common type.

Types of Essay Writing

When it comes to writing an essay, there is not simply one type, there are, quite a few types of essay, and each of them has its purpose and function which are as follows:

Narrative Essays

A narrative essay details a story, oftentimes from a particular point of view. When writing a narrative essay, you should include a set of characters, a location, a good plot, and a climax to the story. It is vital that when writing this type of essay you use fine details which will allow the reader to feel the emotion and use their senses but also give the story the chance to make a point.

Descriptive Essay

A descriptive essay will describe something in great detail. The subject can be anything from people and places to objects and events but the main point is to go into depth. You might describe the item’s color, where it came from, what it looks like, smells like, tastes like, or how it feels. It is very important to allow the reader to sense what you are writing about and allow them to feel some sort of emotion whilst reading. That being said, the information should be concise and easy to understand, the use of imagery is widely used in this style of essay.

Expository Essay

An expository essay is used as a way to look into a problem and therefore compare it and explore it. For the expository essay, there is a little bit of storytelling involved but this type of essay goes beyond that. The main idea is that it should explain an idea giving information and explanation. Your expository essay should be simple and easy to understand as well as give a variety of viewpoints on the subject that is being discussed. Often this type of essay is used as a way to detail a subject which is usually more difficult for people to understand, clearly and concisely.

Argumentative Essay

When writing an argumentative essay, you will be attempting to convince your reader about an opinion or point of view. The idea is to show the reader whether the topic is true or false along with giving your own opinion. You must use facts and data to back up any claims made within the essay.

Format of Essay Writing

Now there is no rigid format of an essay. It is a creative process so it should not be confined within boundaries. However, there is a basic structure that is generally followed while writing essays.

This is the first paragraph of your essay. This is where the writer introduces his topic for the very first time. You can give a very brief synopsis of your essay in the introductory paragraph. Generally, it is not very long, about 4-6 lines.

This is the main crux of your essays. The body is the meat of your essay sandwiched between the introduction and the conclusion. So the most vital content of the essay will be here. This need not be confined to one paragraph. It can extend to two or more paragraphs according to the content.

This is the last paragraph of the essay. Sometimes a conclusion will just mirror the introductory paragraph but make sure the words and syntax are different. A conclusion is also a great place, to sum up, a story or an argument. You can round up your essay by providing some morals or wrapping up a story. Make sure you complete your essays with the conclusion, leave no hanging threads.

Writing Tips

Give your essays an interesting and appropriate title. It will help draw the attention of the reader and pique their curiosity

Keep it between 300-500 words. This is the ideal length, you can take creative license to increase or decrease it

Keep your language simple and crisp. Unnecessary complicated and difficult words break the flow of the sentence.

Do not make grammar mistakes, use correct punctuation and spelling five-paragraph. If this is not done it will distract the reader from the content

Before beginning the essay, organize your thoughts and plot a rough draft. This way you can ensure the story will flow and not be an unorganized mess.

Understand the Topic Thoroughly-Sometimes we jump to a conclusion just by reading the topic once and later we realize that the topic was different than what we wrote about. Read the topic as many times as it takes for you to align your opinion and understanding about the topic.

Make Pointers-It is a daunting task to write an essay inflow as sometimes we tend to lose our way of explaining and get off-topic, missing important details. Thinking about all points you want to discuss and then writing them down somewhere helps in covering everything you hoped to convey in your essay.

Develop a Plan and Do The Math-Essays have word limits and you have to plan your content in such a way that it is accurate, well-described, and meets the word limit given. Keep a track of your words while writing so that you always have an idea of how much to write more or less.

Essays are the most important means of learning the structure of writing and presenting them to the reader.

FAQs on Essay Writing

1. Writing an Essay in a format is important?

Yes, it is important because it makes your content more streamlined and understandable by the reader. A set format gives a reader a clear picture of what you are trying to explain. It also organises your own thoughts while composing an essay as we tend to think and write in a haphazard manner. The format gives a structure to the writeup.

2. How does Essay writing improve our English?

Essay writing is a very important part of your English earning curriculum, as you understand how to describe anything in your words or how to put your point of view without losing its meaning

3. How do you write a good essay?

Start by writing a thorough plan. Ensure your essay has a clear structure and overall argument. Try to back up each point you make with a quotation. Answer the question in your introduction and conclusion but remember to be creative too.

4. What is the format of writing an essay?

A basic essay consists of three main parts: introduction, body, and conclusion. This basic essay format will help you to write and organize an essay. However, flexibility is important. While keeping this basic essay format in mind, let the topic and specific assignment guide the writing and organization.

5. How many paragraphs does an essay have?

The basic format for an essay is known as the five paragraph essay – but an essay may have as many paragraphs as needed. A five-paragraph essay contains five paragraphs. However, the essay itself consists of three sections: an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. Below we'll explore the basics of writing an essay.

6. Can you use the word you in an essay?

In academic or college writing, most formal essays and research reports use third-person pronouns and do not use “I” or “you.” An essay is the writer's analysis of a topic. “You” has no place in an essay since the essay is the writer's thoughts and not the reader's thoughts.

7. What does bridge mean in an essay?

A bridge sentence is a special kind of topic sentence. In addition to signaling what the new paragraph is about, it shows how that follows from what the old paragraph said. The key to constructing good bridges is briefly pointing back to what you just finished saying.

Tips for Online Students , Tips for Students

How To Write An Essay: Beginner Tips And Tricks

Many students dread writing essays, but essay writing is an important skill to develop in high school, university, and even into your future career. By learning how to write an essay properly, the process can become more enjoyable and you’ll find you’re better able to organize and articulate your thoughts.

When writing an essay, it’s common to follow a specific pattern, no matter what the topic is. Once you’ve used the pattern a few times and you know how to structure an essay, it will become a lot more simple to apply your knowledge to every essay.

No matter which major you choose, you should know how to craft a good essay. Here, we’ll cover the basics of essay writing, along with some helpful tips to make the writing process go smoothly.

Photo by Laura Chouette on Unsplash

Types of Essays

Think of an essay as a discussion. There are many types of discussions you can have with someone else. You can be describing a story that happened to you, you might explain to them how to do something, or you might even argue about a certain topic.

When it comes to different types of essays, it follows a similar pattern. Like a friendly discussion, each type of essay will come with its own set of expectations or goals.

For example, when arguing with a friend, your goal is to convince them that you’re right. The same goes for an argumentative essay.

Here are a few of the main essay types you can expect to come across during your time in school:

Narrative Essay

This type of essay is almost like telling a story, not in the traditional sense with dialogue and characters, but as if you’re writing out an event or series of events to relay information to the reader.

Persuasive Essay

Here, your goal is to persuade the reader about your views on a specific topic.

Descriptive Essay

This is the kind of essay where you go into a lot more specific details describing a topic such as a place or an event.

Argumentative Essay

In this essay, you’re choosing a stance on a topic, usually controversial, and your goal is to present evidence that proves your point is correct.

Expository Essay

Your purpose with this type of essay is to tell the reader how to complete a specific process, often including a step-by-step guide or something similar.

Compare and Contrast Essay

You might have done this in school with two different books or characters, but the ultimate goal is to draw similarities and differences between any two given subjects.

The Main Stages of Essay Writing

When it comes to writing an essay, many students think the only stage is getting all your ideas down on paper and submitting your work. However, that’s not quite the case.

There are three main stages of writing an essay, each one with its own purpose. Of course, writing the essay itself is the most substantial part, but the other two stages are equally as important.

So, what are these three stages of essay writing? They are:

Preparation

Before you even write one word, it’s important to prepare the content and structure of your essay. If a topic wasn’t assigned to you, then the first thing you should do is settle on a topic. Next, you want to conduct your research on that topic and create a detailed outline based on your research. The preparation stage will make writing your essay that much easier since, with your outline and research, you should already have the skeleton of your essay.

Writing is the most time-consuming stage. In this stage, you will write out all your thoughts and ideas and craft your essay based on your outline. You’ll work on developing your ideas and fleshing them out throughout the introduction, body, and conclusion (more on these soon).

In the final stage, you’ll go over your essay and check for a few things. First, you’ll check if your essay is cohesive, if all the points make sense and are related to your topic, and that your facts are cited and backed up. You can also check for typos, grammar and punctuation mistakes, and formatting errors.

The Five-Paragraph Essay

We mentioned earlier that essay writing follows a specific structure, and for the most part in academic or college essays , the five-paragraph essay is the generally accepted structure you’ll be expected to use.

The five-paragraph essay is broken down into one introduction paragraph, three body paragraphs, and a closing paragraph. However, that doesn’t always mean that an essay is written strictly in five paragraphs, but rather that this structure can be used loosely and the three body paragraphs might become three sections instead.

Let’s take a closer look at each section and what it entails.

Introduction

As the name implies, the purpose of your introduction paragraph is to introduce your idea. A good introduction begins with a “hook,” something that grabs your reader’s attention and makes them excited to read more.

Another key tenant of an introduction is a thesis statement, which usually comes towards the end of the introduction itself. Your thesis statement should be a phrase that explains your argument, position, or central idea that you plan on developing throughout the essay.

You can also include a short outline of what to expect in your introduction, including bringing up brief points that you plan on explaining more later on in the body paragraphs.

Here is where most of your essay happens. The body paragraphs are where you develop your ideas and bring up all the points related to your main topic.

In general, you’re meant to have three body paragraphs, or sections, and each one should bring up a different point. Think of it as bringing up evidence. Each paragraph is a different piece of evidence, and when the three pieces are taken together, it backs up your main point — your thesis statement — really well.

That being said, you still want each body paragraph to be tied together in some way so that the essay flows. The points should be distinct enough, but they should relate to each other, and definitely to your thesis statement. Each body paragraph works to advance your point, so when crafting your essay, it’s important to keep this in mind so that you avoid going off-track or writing things that are off-topic.

Many students aren’t sure how to write a conclusion for an essay and tend to see their conclusion as an afterthought, but this section is just as important as the rest of your work.

You shouldn’t be presenting any new ideas in your conclusion, but you should summarize your main points and show how they back up your thesis statement.

Essentially, the conclusion is similar in structure and content to the introduction, but instead of introducing your essay, it should be wrapping up the main thoughts and presenting them to the reader as a singular closed argument.

Photo by AMIT RANJAN on Unsplash

Steps to Writing an Essay

Now that you have a better idea of an essay’s structure and all the elements that go into it, you might be wondering what the different steps are to actually write your essay.

Don’t worry, we’ve got you covered. Instead of going in blind, follow these steps on how to write your essay from start to finish.

Understand Your Assignment

When writing an essay for an assignment, the first critical step is to make sure you’ve read through your assignment carefully and understand it thoroughly. You want to check what type of essay is required, that you understand the topic, and that you pay attention to any formatting or structural requirements. You don’t want to lose marks just because you didn’t read the assignment carefully.

Research Your Topic

Once you understand your assignment, it’s time to do some research. In this step, you should start looking at different sources to get ideas for what points you want to bring up throughout your essay.

Search online or head to the library and get as many resources as possible. You don’t need to use them all, but it’s good to start with a lot and then narrow down your sources as you become more certain of your essay’s direction.

Start Brainstorming

After research comes the brainstorming. There are a lot of different ways to start the brainstorming process . Here are a few you might find helpful:

- Think about what you found during your research that interested you the most

- Jot down all your ideas, even if they’re not yet fully formed

- Create word clouds or maps for similar terms or ideas that come up so you can group them together based on their similarities

- Try freewriting to get all your ideas out before arranging them

Create a Thesis

This is often the most tricky part of the whole process since you want to create a thesis that’s strong and that you’re about to develop throughout the entire essay. Therefore, you want to choose a thesis statement that’s broad enough that you’ll have enough to say about it, but not so broad that you can’t be precise.

Write Your Outline

Armed with your research, brainstorming sessions, and your thesis statement, the next step is to write an outline.

In the outline, you’ll want to put your thesis statement at the beginning and start creating the basic skeleton of how you want your essay to look.

A good way to tackle an essay is to use topic sentences . A topic sentence is like a mini-thesis statement that is usually the first sentence of a new paragraph. This sentence introduces the main idea that will be detailed throughout the paragraph.

If you create an outline with the topic sentences for your body paragraphs and then a few points of what you want to discuss, you’ll already have a strong starting point when it comes time to sit down and write. This brings us to our next step…

Write a First Draft

The first time you write your entire essay doesn’t need to be perfect, but you do need to get everything on the page so that you’re able to then write a second draft or review it afterward.

Everyone’s writing process is different. Some students like to write their essay in the standard order of intro, body, and conclusion, while others prefer to start with the “meat” of the essay and tackle the body, and then fill in the other sections afterward.

Make sure your essay follows your outline and that everything relates to your thesis statement and your points are backed up by the research you did.

Revise, Edit, and Proofread

The revision process is one of the three main stages of writing an essay, yet many people skip this step thinking their work is done after the first draft is complete.

However, proofreading, reviewing, and making edits on your essay can spell the difference between a B paper and an A.

After writing the first draft, try and set your essay aside for a few hours or even a day or two, and then come back to it with fresh eyes to review it. You might find mistakes or inconsistencies you missed or better ways to formulate your arguments.

Add the Finishing Touches

Finally, you’ll want to make sure everything that’s required is in your essay. Review your assignment again and see if all the requirements are there, such as formatting rules, citations, quotes, etc.

Go over the order of your paragraphs and make sure everything makes sense, flows well, and uses the same writing style .

Once everything is checked and all the last touches are added, give your essay a final read through just to ensure it’s as you want it before handing it in.

A good way to do this is to read your essay out loud since you’ll be able to hear if there are any mistakes or inaccuracies.

Essay Writing Tips

With the steps outlined above, you should be able to craft a great essay. Still, there are some other handy tips we’d recommend just to ensure that the essay writing process goes as smoothly as possible.

- Start your essay early. This is the first tip for a reason. It’s one of the most important things you can do to write a good essay. If you start it the night before, then you won’t have enough time to research, brainstorm, and outline — and you surely won’t have enough time to review.

- Don’t try and write it in one sitting. It’s ok if you need to take breaks or write it over a few days. It’s better to write it in multiple sittings so that you have a fresh mind each time and you’re able to focus.

- Always keep the essay question in mind. If you’re given an assigned question, then you should always keep it handy when writing your essay to make sure you’re always working to answer the question.

- Use transitions between paragraphs. In order to improve the readability of your essay, try and make clear transitions between paragraphs. This means trying to relate the end of one paragraph to the beginning of the next one so the shift doesn’t seem random.

- Integrate your research thoughtfully. Add in citations or quotes from your research materials to back up your thesis and main points. This will show that you did the research and that your thesis is backed up by it.

Wrapping Up

Writing an essay doesn’t need to be daunting if you know how to approach it. Using our essay writing steps and tips, you’ll have better knowledge on how to write an essay and you’ll be able to apply it to your next assignment. Once you do this a few times, it will become more natural to you and the essay writing process will become quicker and easier.

If you still need assistance with your essay, check with a student advisor to see if they offer help with writing. At University of the People(UoPeople), we always want our students to succeed, so our student advisors are ready to help with writing skills when necessary.

Related Articles

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Essay Writing

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The Modes of Discourse—Exposition, Description, Narration, Argumentation (EDNA)—are common paper assignments you may encounter in your writing classes. Although these genres have been criticized by some composition scholars, the Purdue OWL recognizes the wide spread use of these approaches and students’ need to understand and produce them.

This resource begins with a general description of essay writing and moves to a discussion of common essay genres students may encounter across the curriculum. The four genres of essays (description, narration, exposition, and argumentation) are common paper assignments you may encounter in your writing classes. Although these genres, also known as the modes of discourse, have been criticized by some composition scholars, the Purdue OWL recognizes the wide spread use of these genres and students’ need to understand and produce these types of essays. We hope these resources will help.

The essay is a commonly assigned form of writing that every student will encounter while in academia. Therefore, it is wise for the student to become capable and comfortable with this type of writing early on in her training.

Essays can be a rewarding and challenging type of writing and are often assigned either to be done in class, which requires previous planning and practice (and a bit of creativity) on the part of the student, or as homework, which likewise demands a certain amount of preparation. Many poorly crafted essays have been produced on account of a lack of preparation and confidence. However, students can avoid the discomfort often associated with essay writing by understanding some common genres.

Before delving into its various genres, let’s begin with a basic definition of the essay.

What is an essay?

Though the word essay has come to be understood as a type of writing in Modern English, its origins provide us with some useful insights. The word comes into the English language through the French influence on Middle English; tracing it back further, we find that the French form of the word comes from the Latin verb exigere , which means "to examine, test, or (literally) to drive out." Through the excavation of this ancient word, we are able to unearth the essence of the academic essay: to encourage students to test or examine their ideas concerning a particular topic.

Essays are shorter pieces of writing that often require the student to hone a number of skills such as close reading, analysis, comparison and contrast, persuasion, conciseness, clarity, and exposition. As is evidenced by this list of attributes, there is much to be gained by the student who strives to succeed at essay writing.

The purpose of an essay is to encourage students to develop ideas and concepts in their writing with the direction of little more than their own thoughts (it may be helpful to view the essay as the converse of a research paper). Therefore, essays are (by nature) concise and require clarity in purpose and direction. This means that there is no room for the student’s thoughts to wander or stray from his or her purpose; the writing must be deliberate and interesting.

This handout should help students become familiar and comfortable with the process of essay composition through the introduction of some common essay genres.

This handout includes a brief introduction to the following genres of essay writing:

- Expository essays

- Descriptive essays

- Narrative essays

- Argumentative (Persuasive) essays

Essay Writing: A complete guide for students and teachers

P LANNING, PARAGRAPHING AND POLISHING: FINE-TUNING THE PERFECT ESSAY

Essay writing is an essential skill for every student. Whether writing a particular academic essay (such as persuasive, narrative, descriptive, or expository) or a timed exam essay, the key to getting good at writing is to write. Creating opportunities for our students to engage in extended writing activities will go a long way to helping them improve their skills as scribes.

But, putting the hours in alone will not be enough to attain the highest levels in essay writing. Practice must be meaningful. Once students have a broad overview of how to structure the various types of essays, they are ready to narrow in on the minor details that will enable them to fine-tune their work as a lean vehicle of their thoughts and ideas.

In this article, we will drill down to some aspects that will assist students in taking their essay writing skills up a notch. Many ideas and activities can be integrated into broader lesson plans based on essay writing. Often, though, they will work effectively in isolation – just as athletes isolate physical movements to drill that are relevant to their sport. When these movements become second nature, they can be repeated naturally in the context of the game or in our case, the writing of the essay.

THE ULTIMATE NONFICTION WRITING TEACHING RESOURCE

- 270 pages of the most effective teaching strategies

- 50+ digital tools ready right out of the box

- 75 editable resources for student differentiation

- Loads of tricks and tips to add to your teaching tool bag

- All explanations are reinforced with concrete examples.

- Links to high-quality video tutorials

- Clear objectives easy to match to the demands of your curriculum

Planning an essay

The Boys Scouts’ motto is famously ‘Be Prepared’. It’s a solid motto that can be applied to most aspects of life; essay writing is no different. Given the purpose of an essay is generally to present a logical and reasoned argument, investing time in organising arguments, ideas, and structure would seem to be time well spent.

Given that essays can take a wide range of forms and that we all have our own individual approaches to writing, it stands to reason that there will be no single best approach to the planning stage of essay writing. That said, there are several helpful hints and techniques we can share with our students to help them wrestle their ideas into a writable form. Let’s take a look at a few of the best of these:

BREAK THE QUESTION DOWN: UNDERSTAND YOUR ESSAY TOPIC.

Whether students are tackling an assignment that you have set for them in class or responding to an essay prompt in an exam situation, they should get into the habit of analyzing the nature of the task. To do this, they should unravel the question’s meaning or prompt. Students can practice this in class by responding to various essay titles, questions, and prompts, thereby gaining valuable experience breaking these down.

Have students work in groups to underline and dissect the keywords and phrases and discuss what exactly is being asked of them in the task. Are they being asked to discuss, describe, persuade, or explain? Understanding the exact nature of the task is crucial before going any further in the planning process, never mind the writing process .

BRAINSTORM AND MIND MAP WHAT YOU KNOW:

Once students have understood what the essay task asks them, they should consider what they know about the topic and, often, how they feel about it. When teaching essay writing, we so often emphasize that it is about expressing our opinions on things, but for our younger students what they think about something isn’t always obvious, even to themselves.

Brainstorming and mind-mapping what they know about a topic offers them an opportunity to uncover not just what they already know about a topic, but also gives them a chance to reveal to themselves what they think about the topic. This will help guide them in structuring their research and, later, the essay they will write . When writing an essay in an exam context, this may be the only ‘research’ the student can undertake before the writing, so practicing this will be even more important.

RESEARCH YOUR ESSAY

The previous step above should reveal to students the general direction their research will take. With the ubiquitousness of the internet, gone are the days of students relying on a single well-thumbed encyclopaedia from the school library as their sole authoritative source in their essay. If anything, the real problem for our students today is narrowing down their sources to a manageable number. Students should use the information from the previous step to help here. At this stage, it is important that they:

● Ensure the research material is directly relevant to the essay task

● Record in detail the sources of the information that they will use in their essay

● Engage with the material personally by asking questions and challenging their own biases

● Identify the key points that will be made in their essay

● Group ideas, counterarguments, and opinions together

● Identify the overarching argument they will make in their own essay.

Once these stages have been completed the student is ready to organise their points into a logical order.

WRITING YOUR ESSAY

There are a number of ways for students to organize their points in preparation for writing. They can use graphic organizers , post-it notes, or any number of available writing apps. The important thing for them to consider here is that their points should follow a logical progression. This progression of their argument will be expressed in the form of body paragraphs that will inform the structure of their finished essay.

The number of paragraphs contained in an essay will depend on a number of factors such as word limits, time limits, the complexity of the question etc. Regardless of the essay’s length, students should ensure their essay follows the Rule of Three in that every essay they write contains an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

Generally speaking, essay paragraphs will focus on one main idea that is usually expressed in a topic sentence that is followed by a series of supporting sentences that bolster that main idea. The first and final sentences are of the most significance here with the first sentence of a paragraph making the point to the reader and the final sentence of the paragraph making the overall relevance to the essay’s argument crystal clear.

Though students will most likely be familiar with the broad generic structure of essays, it is worth investing time to ensure they have a clear conception of how each part of the essay works, that is, of the exact nature of the task it performs. Let’s review:

Common Essay Structure

Introduction: Provides the reader with context for the essay. It states the broad argument that the essay will make and informs the reader of the writer’s general perspective and approach to the question.

Body Paragraphs: These are the ‘meat’ of the essay and lay out the argument stated in the introduction point by point with supporting evidence.

Conclusion: Usually, the conclusion will restate the central argument while summarising the essay’s main supporting reasons before linking everything back to the original question.

ESSAY WRITING PARAGRAPH WRITING TIPS

● Each paragraph should focus on a single main idea

● Paragraphs should follow a logical sequence; students should group similar ideas together to avoid incoherence

● Paragraphs should be denoted consistently; students should choose either to indent or skip a line

● Transition words and phrases such as alternatively , consequently , in contrast should be used to give flow and provide a bridge between paragraphs.

HOW TO EDIT AN ESSAY

Students shouldn’t expect their essays to emerge from the writing process perfectly formed. Except in exam situations and the like, thorough editing is an essential aspect in the writing process.

Often, students struggle with this aspect of the process the most. After spending hours of effort on planning, research, and writing the first draft, students can be reluctant to go back over the same terrain they have so recently travelled. It is important at this point to give them some helpful guidelines to help them to know what to look out for. The following tips will provide just such help:

One Piece at a Time: There is a lot to look out for in the editing process and often students overlook aspects as they try to juggle too many balls during the process. One effective strategy to combat this is for students to perform a number of rounds of editing with each focusing on a different aspect. For example, the first round could focus on content, the second round on looking out for word repetition (use a thesaurus to help here), with the third attending to spelling and grammar.

Sum It Up: When reviewing the paragraphs they have written, a good starting point is for students to read each paragraph and attempt to sum up its main point in a single line. If this is not possible, their readers will most likely have difficulty following their train of thought too and the paragraph needs to be overhauled.

Let It Breathe: When possible, encourage students to allow some time for their essay to ‘breathe’ before returning to it for editing purposes. This may require some skilful time management on the part of the student, for example, a student rush-writing the night before the deadline does not lend itself to effective editing. Fresh eyes are one of the sharpest tools in the writer’s toolbox.

Read It Aloud: This time-tested editing method is a great way for students to identify mistakes and typos in their work. We tend to read things more slowly when reading aloud giving us the time to spot errors. Also, when we read silently our minds can often fill in the gaps or gloss over the mistakes that will become apparent when we read out loud.

Phone a Friend: Peer editing is another great way to identify errors that our brains may miss when reading our own work. Encourage students to partner up for a little ‘you scratch my back, I scratch yours’.

Use Tech Tools: We need to ensure our students have the mental tools to edit their own work and for this they will need a good grasp of English grammar and punctuation. However, there are also a wealth of tech tools such as spellcheck and grammar checks that can offer a great once-over option to catch anything students may have missed in earlier editing rounds.

Putting the Jewels on Display: While some struggle to edit, others struggle to let go. There comes a point when it is time for students to release their work to the reader. They must learn to relinquish control after the creation is complete. This will be much easier to achieve if the student feels that they have done everything in their control to ensure their essay is representative of the best of their abilities and if they have followed the advice here, they should be confident they have done so.

WRITING CHECKLISTS FOR ALL TEXT TYPES

ESSAY WRITING video tutorials

- Tips for Reading an Assignment Prompt

- Asking Analytical Questions

- Introductions

- What Do Introductions Across the Disciplines Have in Common?

- Anatomy of a Body Paragraph

- Transitions

- Tips for Organizing Your Essay

- Counterargument

- Conclusions

- Strategies for Essay Writing: Downloadable PDFs

- Brief Guides to Writing in the Disciplines

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Essay Basics

For college, an essay is a collection of paragraphs that all work together to express ideas that respond appropriately to the directions and guidelines of a given written assignment. Depending on the instructor, course, or assignment, you might also hear essays called papers, term papers, articles, themes, compositions, reports, writing assignments , and written assessments , but these terms are largely interchangeable at the beginning of college.

Essays and their assignments vary so much that there is no single right kind of essay, so there are no clear answers to questions such as, “How many paragraphs should a college essay have?” or, “How many examples should I use to help convey my ideas?” etc.

But with that said, most essays have a few components in common:

- The Introduction: the beginning parts that show what is to come

- The Body: the bulk of the essay that says everything the assignment calls for

- The Conclusion: the ending parts that emphasize or make sense of what has been said

One rudimentary type of essay that displays these components in a way that’s easy to demonstrate and see is the five-paragraph essay.

The Five Paragraph Essay

The term “five-paragraph essay” refers to a default structure that consists of the following:

- This should clearly state the main idea of the whole essay, also called the essay’s claim or thesis .

- This should also include a brief mention of the main ideas to come, which is the essay map .

- Each paragraph should be about one main point that supports the main idea of the essay (the claim or thesis).

- The topic sentence of each paragraph should be its main point.

- The rest of the sentences of each paragraph should explain or support that topic sentence. In general, the method for this support is to provide an explanation, then an example or analogy, and then a conclusion. See more in the textbook section Paragraph Basics.

- This should clarify the most important ideas or interpretations regarding what the essay has said in the body.

Example Outline of a Five-Paragraph Essay:

- Claim/Thesis: Unleashed dogs on city streets are a dangerous nuisance.

- Essay Map : They scare cyclists and pedestrians, present traffic hazards, and damage gardens.

- Topic Sentence: Dogs can scare cyclists and pedestrians.

- Cyclists are forced to zigzag on the road.

- School children panic and turn wildly on their bikes.

- People who are walking at night freeze in fear.

- Topic Sentence : Loose dogs are traffic hazards.

- Dogs in the street make people swerve their cars.

- To avoid dogs, drivers run into other cars or pedestrians.

- Children coaxing dogs across busy streets create danger.

- Topic Sentence: Unleashed dogs damage gardens.

- They step on flowers and vegetables.

- They destroy hedges by urinating on them.

- They mess up lawns by digging holes.

- Emphasis: The problem of unleashed dogs should be taken seriously by citizens and city council members.

Using a subject assigned by your instructor, create an outline for a five-paragraph essay following these guidelines. Complete sentences are allowed but not required in such outlines.

- Claim/Thesis

- Topic Sentence

- Support (Explanation, Example or Analogy, and Conclusion)

When the above example outline is turned into complete sentences, arranged in paragraphs, and further elaborated here and there for clarity and transition, it becomes a complete five-paragraph essay, as seen here:

Problems Unleashed

With unfamiliar turning lanes branching and numerous traffic lights flashing and aggressive drivers weaving and honking, the last surprise you need as an urban driver is to suddenly see a dog run by in front of you. Unfortunately, given the current ordinances allowing unleashed dogs, this is the case. Unleashed dogs on city streets are a dangerous nuisance. They not only present traffic hazards, but they also scare cyclists and pedestrians, and they damage property such as gardens.

Loose dogs are traffic hazards. Many dogs won’t hesitate to run across busy roads, and as soon as they do, people must suddenly swerve their cars. But the cars swerve where? In crowded city streets, the chances are there to swerve accidentally into other cars or pedestrians. And this danger is made worse by the tendency of children, who often don’t know any better, coaxing dogs across busy streets. These kinds of dangers are frequent enough for causes that can’t be controlled, and the problem of unleashed dogs, which can be controlled, adds to them unnecessarily.

And these dangers aren’t limited to swerving cars, for dogs can scare cyclists and pedestrians too. When dogs dart across their path, cyclists are forced to zigzag on the road. This leads to wrecks, which for cyclists can cause serious injury. And while adult cyclists might maintain control when confronted with a darting dog, children riding home from school can’t be expected to. They typically panic and turn wildly on their bikes. Even among pedestrians, unleashed dogs present a real danger, for no one can predict how aggressive a loose dog might be. When confronted with such dogs, people who are walking at night freeze in fear.

These are some of the most severe problems with unleashed dogs, but there are others still worthy of concern, such as the damage unleashed dogs do to lawns and gardens. Property owners invest significant time and money into the value of their lawns, but dogs can’t understand or respect that. Let loose without a leash, dogs will simply act like the animals they are. They will step on flowers and vegetables, destroy hedges by urinating on them, and mess up lawns by digging holes.

With the city ordinances as they currently stand, unleashed dogs are allowed to cause danger, injury, fear, and property damage. But this doesn’t have to be the case. The problem of unleashed dogs should be taken seriously by citizens and city council members. We would be wise to stop letting dogs take responsibility for their actions, and start taking responsibility ourselves.

Read the above example outline and essay carefully. Then identify any significant changes in ideas, wording, or organization that the essay has made from the original plan in the outline. Explain why the writer would make those changes.

Using your outline from Exercise 1, create a five-paragraph essay.

Keep in mind that the five-paragraph essay is a rudimentary essay form. It is excellent for demonstrating the key parts of a general essay, and it can address many types of short writing assignments in college, but it is too limited to sustain the more complex kinds of discussions many of the higher-level college essays need to develop and present.

For those kinds of essays, you will need a deeper and more complete understanding of the general essay structure (below), as well as an understanding of various writing modes and strategies, research, and format (the sections and chapters that follow).

Complete General Essay Structure

The following explains how to write an essay using a general essay structure at a far more complete level and with far more depth than the five-paragraph essay. This complete general essay structure can be applied to many of your essay assignments that you will encounter in many of your college classes, regardless of subject matter. Although innumerable alterations and variations are possible in successful essays, these concepts are foundational, and they merit your understanding and application as a student of writing.

Also note that there is no set number of paragraphs using a complete general essay structure, as there is in the five-paragraph essay (one introductory, three body, and one concluding). A good introduction can be broken up into more than one paragraph, as can a conclusion, and body paragraphs might number more than three. But this complete general essay structure can indeed be achieved in five paragraphs as well.

Here are the components of complete general essay structure:

- Use a phrase that identifies the subject.

- Consider a title that also suggests the main claim, or thesis (see below, and see the section Thesis for more information)

- Remember that the title is the writer’s main opportunity to control interpretation.

- Don’t use a phrase that could easily apply to all the other students’ essays, such as the number or title of the assignment.

- The Introduction gives the audience a stark impression of what the essay is about.

- In choosing this glimpse, consider that which is surprising, counter-intuitive, or vivid.

- Don’t use false questions, such as those about the reader’s personal experience, those that have obvious answers, or those for which you won’t attempt specific or compelling answers.

- Give a larger understanding of the glimpse above, such as what the important issue is, or why it is significant.

- Don’t get detailed. Save details for the body paragraphs.

- Your main claim or thesis is your position or point about the subject, often confirming or denying a proposition.

- For more details on thesis statements, see the section Thesis.

- Don’t use a question or a fragment as a main claim or thesis.

- Don’t confuse the subject with the main claim or thesis.

- Don’t reference your own essay. State your main points by discussing the subject itself rather than by discussing the essay you’re writing.

- Don’t get detailed here either.

- The Body forms the support for your main claim or thesis.

- Keep in mind that you are not limited to three body paragraphs only, but that three body paragraphs form a good base regardless.

- Give each main point a separate paragraph. Aim for at least three body paragraphs, which means you should have at least three main points that support your main claim or thesis.

- Use topic sentences and supporting sentences in each paragraph. Supporting sentences often come in the form of explanations, then examples or analogies, and then conclusions. For more information on the structure of a paragraph, see the section Paragraph Basics.

- Remember that separate paragraphs not only help the audience read, but they also help writers see their ideas as clarified segments, each of which needs to be completed, connected, and organized.

- For details and strategies about how best to connect paragraphs, see the section Transitions.

- Don’t combine two different focal points into the same paragraph, even if they are about the same subject.

- Don’t contradict the order of your Essay Map from the Introduction, even if minor points require paragraphs in-between the main points.

- Don’t veer away from supporting your main claim or thesis. If any necessary minor point appears to do this, immediately follow it up by conveying its support to your thesis.

- The Conclusion brings your essay to its final and most significant point. Use any one or combination of the following components:

- One good strategy is to use a brief and poignant phrase or quotation.

- Another good strategy is to use a metaphor: description of an interesting image that stands for an important idea.

- Don’t re-state the introduction or be redundant.

- Don’t bring up new details or issues.

- Don’t end on a minor point

- Don’t weaken your essay here with contradiction, false humility, self-deprecation, or un-rebutted opposition.

- Don’t issue commands, get aggressive, or sound exclamatory in the Conclusion.

- For more information, see the section Rhythms of Three.

- Combine or rearrange Emphasis, Humility, and Elevation as needed.

Using a subject assigned by your instructor, create an outline for a complete general essay structure. In your outline, identify the types of ideas that you would use to address the components and principles explained above. Complete sentences are allowed but not required in such outlines.

Using your outline from Exercise 4 and the concepts above, compose a complete general essay.

The Writing Textbook Copyright © 2021 by Josh Woods, editor and contributor, as well as an unnamed author (by request from the original publisher), and other authors named separately is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Learn the Standard Essay Format: MLA, APA, Chicago Styles

Being able to write an essay is a vital part of any student's education. However, it's not just about linearly listing ideas. A lot of institutions will require a certain format that your paper must follow; prime examples would be one of a basic essay format like MLA, the APA, and the Chicago formats. This article will explain the differences between the MLA format, the APA format, and the Chicago format. The application of these could range from high school to college essays, and they stand as the standard of college essay formatting. EssayPro — dissertation services , that will help to make a difference!

What is an Essay Format: Structure

Be it an academic, informative or a specific extended essay - structure is essential. For example, the IB extended essay has very strict requirements that are followed by an assigned academic style of writing (primarily MLA, APA, or Chicago):

- Abstract: comprised of 3 paragraphs, totaling about 300 words, with 100 words in each.

- ~ Paragraph 1: must include a research question, thesis, and outline of the essay’s importance.

- ~ Paragraph 2: Key resources, scope and limits of research, etc.

- ~ Paragraph 3: Conclusion that you’ve already reached in your essay.

- Table of Contents (with page numbers)

- ~ Research question

- ~ Introduction

- ~ Arguments

- ~ Sub-headings

- ~ Conclusion

- ~ Works cited (bibliography)

- Introduction

- ~ The research question is required

- Bibliography (Works Cited)

This outline format for an extended essay is a great example to follow when writing a research essay, and sustaining a proper research essay format - especially if it is based on the MLA guidelines. It is vital to remember that the student must keep track of their resources to apply them to each step outlined above easily. And check out some tips on how to write an essay introduction .

Lost in the Labyrinth of Essay Formatting?

Navigate the complexities of essay structures with ease. Let our experts guide your paper to the format it deserves!

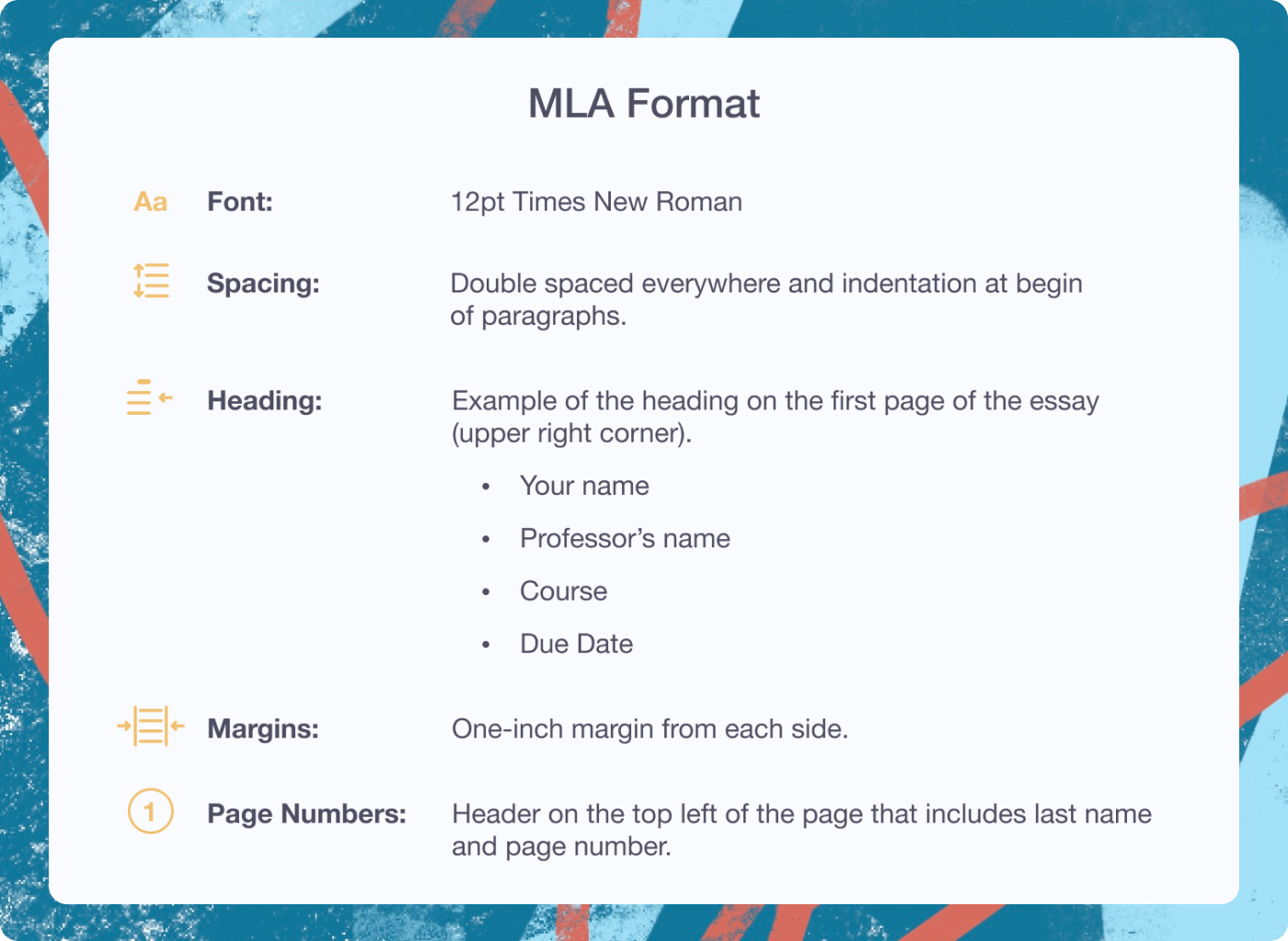

How to Write an Essay in MLA Format

To write an essay in MLA format, one must follow a basic set of guidelines and instructions. This is a step by step from our business essay writing service

- Font : 12pt Times New Roman

- ~ Double spaced everywhere

- ~ No extra spaces, especially between paragraphs

- Heading : Example of the heading on the first page of the essay (upper left corner)

- ~ Your name (John Smith)

- ~ Teacher’s / Professor’s name (Margot Robbie)

- ~ The class (Depends on course/class)

- ~ Date (20 April 2017)

- Margins : One-inch margin on the top, bottom, left and right.

- Page Numbers : Last name and page number must be put on every page of the essay as a “header”. Otherwise, it would go in place of the text.

- Title : There needs to be a proper essay title format, centered and above the first line of the essay of the same font and size as the essay itself.

- Indentation : Just press tab (1/2 inch, just in case)

- Align : Align to the left-hand side, and make sure it is aligned evenly.

It’s important to remember that the essay format of MLA is usually used in humanities, which differs from other types of academic writing that we’ll go into detail later. For now, feast your eyes upon an MLA format essay example:

Essay in MLA Format Example

Mla format digital technology and health, mla vs. apa.

Before we move on to the APA essay format, it is important to distinguish the two types of formatting. Let’s go through the similarities first:

- The formatting styles are similar: spacing, citation, indentation.

- All of the information that is used within the essay must be present within the works cited page (in APA, that’s called a reference page)

- Both use the parenthetical citations within the body of the paper, usually to show a certain quote or calculation.

- Citations are listed alphabetically on the works cited / reference page.

What you need to know about the differences is not extensive, thankfully:

- MLA style is mostly used in humanities, while APA style is focused more on social sciences. The list of sources has a different name (works cited - MLA / references - APA)

- Works cited differ on the way they display the name of the original content (MLA -> Yorke, Thom / APA -> Yorke T.)

- When using an in-text citation, and the author’s name is listed within the sentence, place the page number found at the end: “Yorke believes that Creep was Radiohead’s worst song. (4).” APA, on the other hand, requires that a year is to be inserted: “According to Yorke (2013), Creep was a mess.”

Alright, let’s carry over to the APA style specifics.

Order an Essay Now & and We Will Cite and Format It For Free :

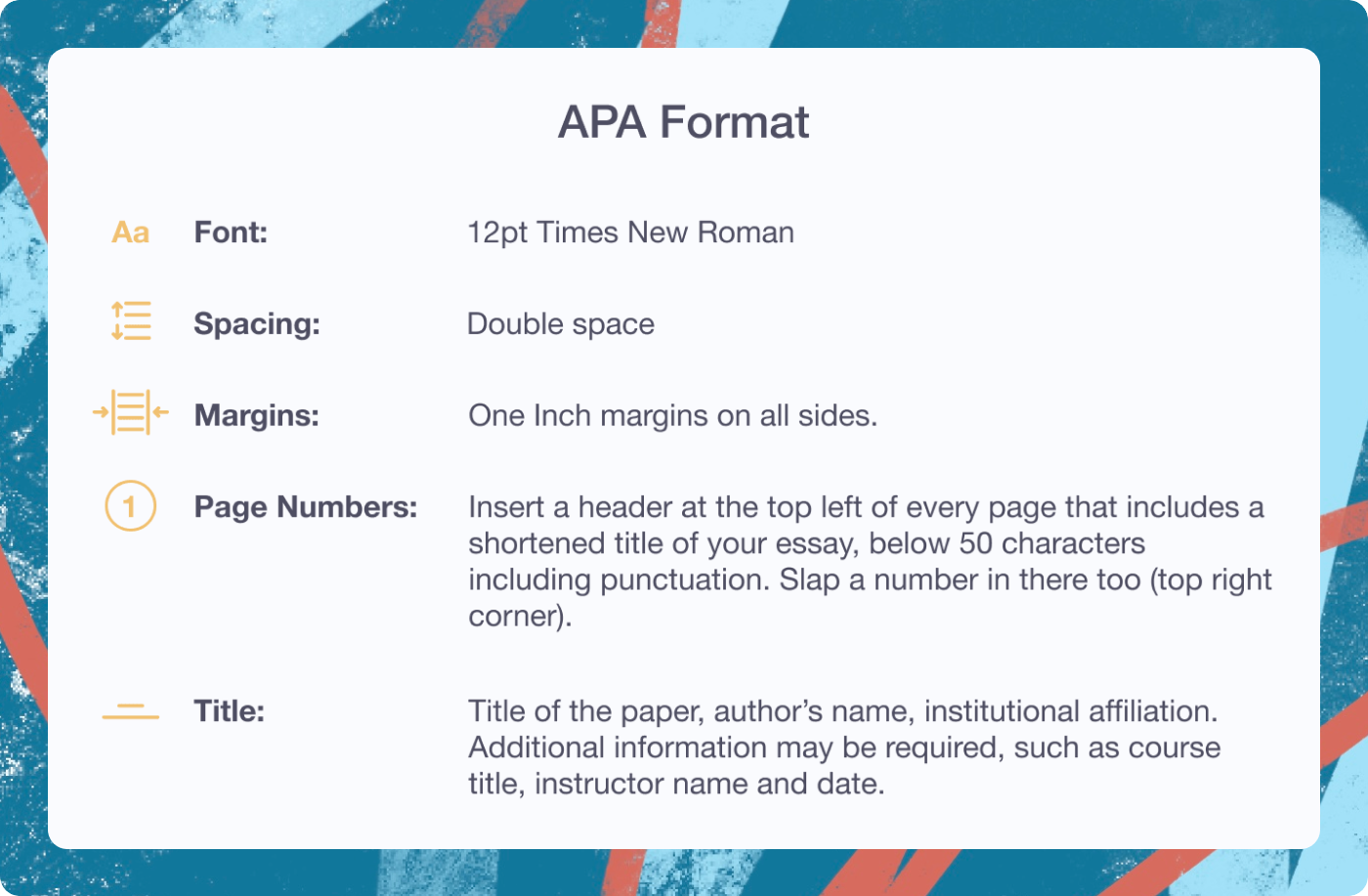

How to write an essay in apa format.

The APA scheme is one of the most common college essay formats, so being familiar with its requirements is crucial. In a basic APA format structure, we can apply a similar list of guidelines as we did in the MLA section:

- Spacing : Double-space that bad boy.

- Margins : One Inch margins on all sides.

- Page Numbers : Insert a header at the top left of every page that includes a shortened title of your essay, below 50 characters including punctuation. Slap a number in there too (top right corner).

- Title Page : Title of the paper, author’s name, institutional affiliation. Additional information may be required, such as course title, instructor name and date.

- Headings: All headings should be written in bold and titlecase. Different heading levels have different additional criteria to apply.

You can also ask us to write or rewrite essay in APA format if you find it difficult or don't have time.

Note that some teachers and professors may request deviations from some of the characteristics that the APA format originally requires, such as those listed above.

Note that some teachers and professors maybe have deviations to some of the characteristics that the APA format originally requires, such as those listed above.

If you think: 'I want someone write a research paper for me ', you can do it at Essaypro.

Essay in APA Format Example

Apa format chronobiology, chicago style.

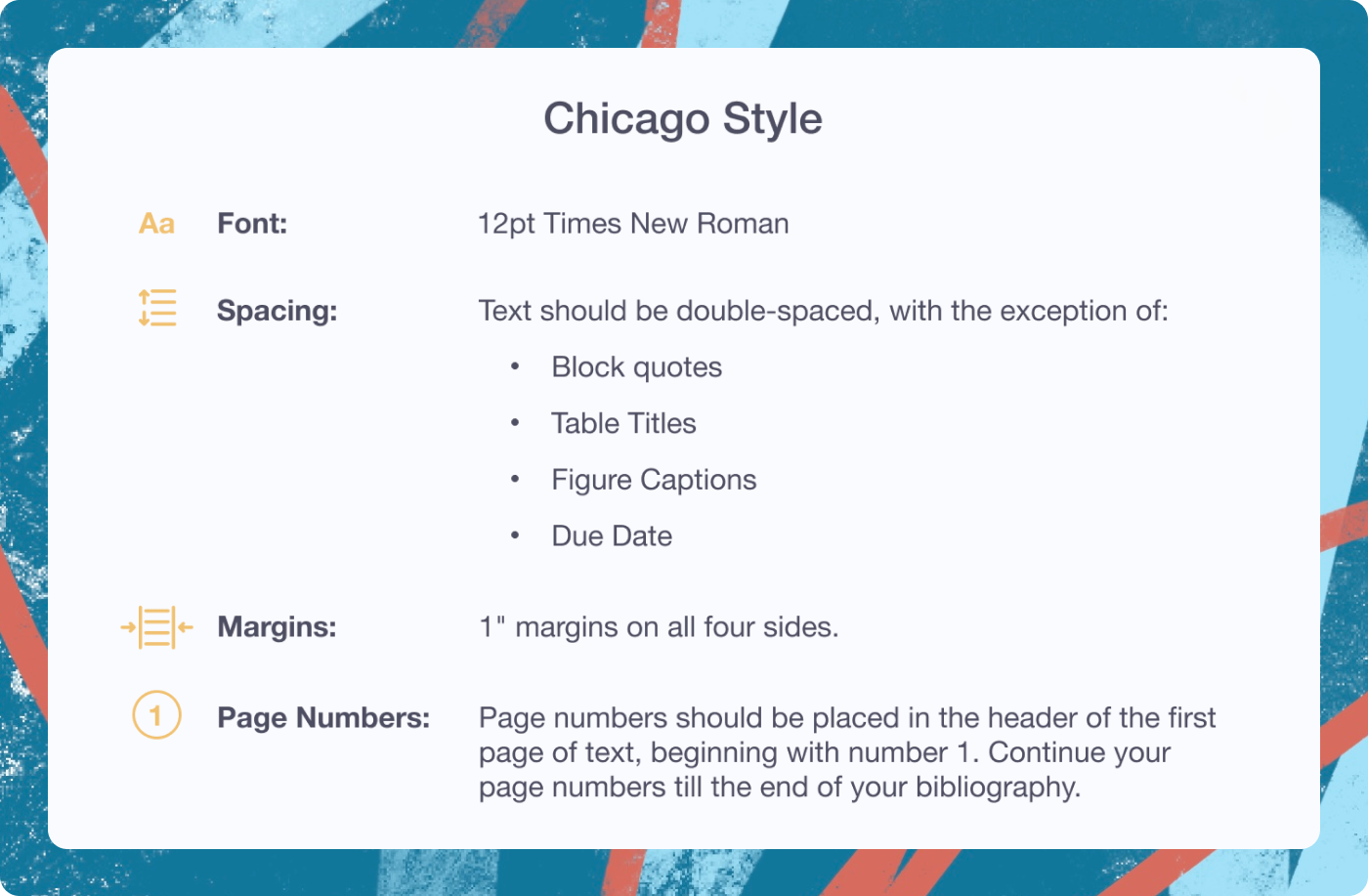

The usage of Chicago style is prevalent in academic writing that focuses on the source of origin. This means that precise citations and footnotes are key to a successful paper.

Chicago Style Essay Format

The same bullet point structure can be applied to the Chicago essay format.

- ~ Chicago style title page is all about spacing.

- ~ Down the page should be the title, with regular text. If longer than one line, double-spaced.

- ~ Next, in the very middle, center your full name.

- ~ Down the page - course number, instructor’s name and the date in separate double-spaced lines.

- Margins : Use one-inch margins apart from the right side.

- ~ Double spaced everywhere.

- ~ No extra spaces, especially between paragraphs.

- Font : Times New Roman is the best choice (12pt)

- Page Numbers

- ~ Last name, page number in the heading of every page on the top right

- ~ Do not number the title page. The first page of the text should start with a 2.

- Footnotes : The Chicago format requires footnotes on paraphrased or quoted passages.

- Bibliography : The bibliography is very similar to that of MLA. Gather the proper information and input it into a specialized citation site.

Tips for Writing an Academic Paper

There isn’t one proper way of writing a paper, but there are solid guidelines to sustain a consistent workflow. Be it a college application essay, a research paper, informative essay, etc. There is a standard essay format that you should follow. For easier access, the following outline will be divided into steps:

Choose a Good Topic

A lot of students struggle with picking a good topic for their essays. The topic you choose should be specific enough so you can explore it in its entirety and hit your word limit if that’s a variable you worry about. With a good topic that should not be a problem. On the other hand, it should not be so broad that some resources would outweigh the information you could squeeze into one paper. Don’t be too specific, or you will find that there is a shortage of information, but don’t be too broad or you will feel overwhelmed. Don’t hesitate to ask your instructor for help with your essay writing.

Start Research as Soon as Possible

Before you even begin writing, make sure that you are acquainted with the information that you are working with. Find compelling arguments and counterpoints, trivia, facts, etc. The sky is the limit when it comes to gathering information.

Pick out Specific, Compelling Resources

When you feel acquainted with the subject, you should be able to have a basic conversation on the matter. Pick out resources that have been bookmarked, saved or are very informative and start extracting information. You will need all you can get to put into the citations at the end of your paper. Stash books, websites, articles and have them ready to cite. See if you can subtract or expand your scope of research.

Create an Outline

Always have a plan. This might be the most important phase of the process. If you have a strong essay outline and you have a particular goal in mind, it’ll be easy to refer to it when you might get stuck somewhere in the middle of the paper. And since you have direct links from the research you’ve done beforehand, the progress is guaranteed to be swift. Having a list of keywords, if applicable, will surely boost the informational scope. With keywords specific to the subject matter of each section, it should be much easier to identify its direction and possible informational criteria.

Write a Draft

Before you jot anything down into the body of your essay, make sure that the outline has enough information to back up whatever statement you choose to explore. Do not be afraid of letting creativity into your paper (within reason, of course) and explore the possibilities. Start with a standard 5 paragraph structure, and the content will come with time.

Ask for a Peer Review of Your Academic Paper

Before you know it, the draft is done, and it’s ready to be sent out for peer review. Ask a classmate, a relative or even a specialist if they are willing to contribute. Get as much feedback as you possibly can and work on it.

Final Draft

Before handing in the final draft, go over it at least one more time, focusing on smaller mistakes like grammar and punctuation. Make sure that what you wrote follows proper essay structure. Learn more about argumentative essay structure on our blog. If you need a second pair of eyes, get help from our service.

Read also our movie review example and try to determine the format in which it is written.

Want Your Essay to Stand Out in Structure and Style?

Don't let poor formatting dim your ideas. Our professional writers are here to give your paper the polished look it needs!

Related Articles

.webp)

Tips for Writing an Effective Application Essay

How to Write an Effective Essay

Writing an essay for college admission gives you a chance to use your authentic voice and show your personality. It's an excellent opportunity to personalize your application beyond your academic credentials, and a well-written essay can have a positive influence come decision time.

Want to know how to draft an essay for your college application ? Here are some tips to keep in mind when writing.

Tips for Essay Writing

A typical college application essay, also known as a personal statement, is 400-600 words. Although that may seem short, writing about yourself can be challenging. It's not something you want to rush or put off at the last moment. Think of it as a critical piece of the application process. Follow these tips to write an impactful essay that can work in your favor.

1. Start Early.

Few people write well under pressure. Try to complete your first draft a few weeks before you have to turn it in. Many advisers recommend starting as early as the summer before your senior year in high school. That way, you have ample time to think about the prompt and craft the best personal statement possible.

You don't have to work on your essay every day, but you'll want to give yourself time to revise and edit. You may discover that you want to change your topic or think of a better way to frame it. Either way, the sooner you start, the better.

2. Understand the Prompt and Instructions.

Before you begin the writing process, take time to understand what the college wants from you. The worst thing you can do is skim through the instructions and submit a piece that doesn't even fit the bare minimum requirements or address the essay topic. Look at the prompt, consider the required word count, and note any unique details each school wants.

3. Create a Strong Opener.

Students seeking help for their application essays often have trouble getting things started. It's a challenging writing process. Finding the right words to start can be the hardest part.

Spending more time working on your opener is always a good idea. The opening sentence sets the stage for the rest of your piece. The introductory paragraph is what piques the interest of the reader, and it can immediately set your essay apart from the others.

4. Stay on Topic.

One of the most important things to remember is to keep to the essay topic. If you're applying to 10 or more colleges, it's easy to veer off course with so many application essays.

A common mistake many students make is trying to fit previously written essays into the mold of another college's requirements. This seems like a time-saving way to avoid writing new pieces entirely, but it often backfires. The result is usually a final piece that's generic, unfocused, or confusing. Always write a new essay for every application, no matter how long it takes.

5. Think About Your Response.

Don't try to guess what the admissions officials want to read. Your essay will be easier to write─and more exciting to read─if you’re genuinely enthusiastic about your subject. Here’s an example: If all your friends are writing application essays about covid-19, it may be a good idea to avoid that topic, unless during the pandemic you had a vivid, life-changing experience you're burning to share. Whatever topic you choose, avoid canned responses. Be creative.

6. Focus on You.

Essay prompts typically give you plenty of latitude, but panel members expect you to focus on a subject that is personal (although not overly intimate) and particular to you. Admissions counselors say the best essays help them learn something about the candidate that they would never know from reading the rest of the application.

7. Stay True to Your Voice.

Use your usual vocabulary. Avoid fancy language you wouldn't use in real life. Imagine yourself reading this essay aloud to a classroom full of people who have never met you. Keep a confident tone. Be wary of words and phrases that undercut that tone.

8. Be Specific and Factual.

Capitalize on real-life experiences. Your essay may give you the time and space to explain why a particular achievement meant so much to you. But resist the urge to exaggerate and embellish. Admissions counselors read thousands of essays each year. They can easily spot a fake.

9. Edit and Proofread.

When you finish the final draft, run it through the spell checker on your computer. Then don’t read your essay for a few days. You'll be more apt to spot typos and awkward grammar when you reread it. After that, ask a teacher, parent, or college student (preferably an English or communications major) to give it a quick read. While you're at it, double-check your word count.

Writing essays for college admission can be daunting, but it doesn't have to be. A well-crafted essay could be the deciding factor─in your favor. Keep these tips in mind, and you'll have no problem creating memorable pieces for every application.

What is the format of a college application essay?

Generally, essays for college admission follow a simple format that includes an opening paragraph, a lengthier body section, and a closing paragraph. You don't need to include a title, which will only take up extra space. Keep in mind that the exact format can vary from one college application to the next. Read the instructions and prompt for more guidance.

Most online applications will include a text box for your essay. If you're attaching it as a document, however, be sure to use a standard, 12-point font and use 1.5-spaced or double-spaced lines, unless the application specifies different font and spacing.

How do you start an essay?

The goal here is to use an attention grabber. Think of it as a way to reel the reader in and interest an admissions officer in what you have to say. There's no trick on how to start a college application essay. The best way you can approach this task is to flex your creative muscles and think outside the box.

You can start with openers such as relevant quotes, exciting anecdotes, or questions. Either way, the first sentence should be unique and intrigue the reader.

What should an essay include?

Every application essay you write should include details about yourself and past experiences. It's another opportunity to make yourself look like a fantastic applicant. Leverage your experiences. Tell a riveting story that fulfills the prompt.

What shouldn’t be included in an essay?

When writing a college application essay, it's usually best to avoid overly personal details and controversial topics. Although these topics might make for an intriguing essay, they can be tricky to express well. If you’re unsure if a topic is appropriate for your essay, check with your school counselor. An essay for college admission shouldn't include a list of achievements or academic accolades either. Your essay isn’t meant to be a rehashing of information the admissions panel can find elsewhere in your application.

How can you make your essay personal and interesting?

The best way to make your essay interesting is to write about something genuinely important to you. That could be an experience that changed your life or a valuable lesson that had an enormous impact on you. Whatever the case, speak from the heart, and be honest.

Is it OK to discuss mental health in an essay?

Mental health struggles can create challenges you must overcome during your education and could be an opportunity for you to show how you’ve handled challenges and overcome obstacles. If you’re considering writing your essay for college admission on this topic, consider talking to your school counselor or with an English teacher on how to frame the essay.

Related Articles

🏀 MARCH MADNESS

❗️ Men's first round set

🚨 (12) Vandy, (16) Presbyterian advance | Women's

Men's bracket

👀 Women's bracket

✍️ Create your bracket

Men's Brackets Lock In

Official Bracket

Ncaa.com | march 21, 2024, latest bracket, schedule and scores for 2024 ncaa men's tournament.

The 64-team NCAA tournament field is set! A thrilling slate of First Four action saw Wagner, Grambling State, Colorado and Colorado State emerge victorious, allowing for the first round of action to begin Thursday at 12:15 p.m.

Take a look at the complete, updated bracket below:

NCAA bracket 2024: Printable March Madness bracket

Click or tap here to open it as a .JPG | Click or tap here for the interactive bracket | PDF link

Here is the schedule for this year's tournament.

- Selection Sunday: Sunday, March 17

- First Four: March 19-20

- First round: March 21-22

- Second round: March 23-24

- Sweet 16: March 28-29

- Elite Eight: March 30-31

- Final Four: Saturday, April 6

- NCAA championship game: Monday, April 8

Here is the game-by-game schedule:

2024 NCAA tournament schedule, scores, highlights

Thursday, March 21 (Round of 64)

- (8) Mississippi State vs. (9) Michigan State | 12:15 p.m. | CBS

- (6) BYU vs. (11) Duquesne | 12:40 p.m. | truTV

- (3) Creighton vs. (14) Akron | 1:30 p.m. | TNT

- (2) Arizona vs. (15) Long Beach State | 2 p.m. | TBS

- (1) North Carolina vs. (16) Wagner | 2:45 p.m. | CBS

- (3) Illinois vs. (14) Morehead State | 3:10 p.m. | truTV

- (6) South Carolina vs. (11) Oregon | 4 p.m. | TNT

- (7) Dayton vs. (10) Nevada | 4:30 p.m. | TBS

- (7) Texas vs. (10) Colorado State | 6:50 p.m. | TNT

- (3) Kentucky vs. (14) Oakland | 7:10 p.m. | CBS

- (5) Gonzaga vs. (12) McNeese | 7:25 p.m. | TBS

- (2) Iowa State vs. (15) South Dakota State | 7:35 p.m. | truTV

- (2) Tennessee vs. (15) Saint Peter's | 9:20 p.m. | TNT

- (6) Texas Tech vs. (11) NC State | 9:40 p.m. | CBS

- (4) Kansas vs. (13) Samford | 9:55 p.m. | TBS

- (7) Washington State vs. (10) Drake | 10:05 p.m. | truTV

Friday, March 22 (Round of 64)

- (8) Florida Atlantic vs. (9) Northwestern | 12:15 p.m. | CBS

- (3) Baylor vs. (14) Colgate | 12:40 p.m. | truTV

- (5) San Diego State vs. (12) UAB | 1:45 p.m. | TNT

- (2) Marquette vs. (15) Western Kentucky | 2 p.m. | TBS

- (1) UConn vs. (16) Stetson | 2:45 p.m. | CBS

- (6) Clemson vs. (11) New Mexico | 3:10 p.m. | truTV

- (4) Auburn vs. (13) Yale | 4:15 p.m. | TNT

- (7) Florida vs. (10) Colorado | 4:30 p.m. | TBS

- (8) Nebraska vs. (9) Texas A&M | 6:50 p.m. | TNT

- (4) Duke vs. (13) Vermont | 7:10 p.m. | CBS

- (1) Purdue vs. (16) Grambling | 7:25 p.m. | TBS

- (4) Alabama vs. (13) College of Charleston | 7:35 pm. | truTV

- (1) Houston vs. (16) Longwood | 9:20 p.m. | TNT

- (5) Wisconsin vs. (12) James Madison | 9:40 p.m. | CBS

- (8) Utah State vs. (9) TCU | 9:55 p.m. | TBS

- (5) Saint Mary's vs. (12) Grand Canyon | 10:05 p.m. | truTV

Saturday, March 23 (Round of 32)

- TBD vs. TBD

Sunday, March 24 (Round of 32)

Thursday, March 28 (Sweet 16)

Friday, March 29 (Sweet 16)

Saturday, March 30 (Elite Eight)

Sunday, March 31 (Elite Eight)

Saturday, April 6 (Final Four)

Monday, April 8 (National championship game)

- TBD vs. TBD | 9:20 p.m.

Tuesday, March 19 (First Four in Dayton, Ohio)

- (16) Wagner 71 , (16) Howard 68

- (10) Colorado State 67 , (10) Virginia 42

Wednesday, March 20 (First Four in Dayton, Ohio)

- (16) Grambling 88 , (16) Montana State 81

- (10) Colorado 60 , (10) Boise State 53

Here's the complete seed list:

These are the sites for the men's tournament in 2024:

March Madness

- 🗓️ 2024 March Madness schedule, dates

- 👀 Everything to know about March Madness

- ❓ How the field of 68 is picked

- 📓 College basketball dictionary: 51 terms defined

Greatest buzzer beaters in March Madness history

Relive Laettner's historic performance against Kentucky

The deepest game-winning buzzer beaters in March Madness history

College basketball's NET rankings, explained

What March Madness looked like the year you were born

Di men's basketball news.

- Grambling State follows familiar footsteps as FDU, faces 1-seed Purdue in the first round

- Here is every HBCU that has won a men's NCAA tournament game in history

- Watch the Quest for the Perfect Bracket Tracker Live show — Day 4

- Watch the Quest for the Perfect Bracket Tracker Live show — Day 3

- 2024 NIT bracket: Schedule, TV channels for the men’s tournament

- Latest bracket, schedule and scores for 2024 NCAA men's tournament

- Blowout loss a footnote in Virginia's rocky tournament history

- With only 7 healthy players, Wagner is set to face 1-seed UNC