AP® Spanish Language

How to approach ap® spanish language free-response questions.

- The Albert Team

- Last Updated On: March 1, 2022

The AP® Spanish Language Course targets interpersonal, interpretive, and presentational modes of communication through writing, reading, speaking, and understanding. Strategies that emphasize vocabulary, language structure, communication, and culture in both contemporary and historical contexts are taught almost exclusively in Spanish. Instruction is often interactive, using Spanish books, music, and patterns of social interactions within a culture to familiarize students with the language.

This AP® Spanish study guide will briefly outline the format of the AP® Spanish Language Exam, putting particular emphasis on the AP® Spanish Language Free-Response section. It will provide insights into why the free-response section is important to the overall test results, mention content covered in the free-response section, and discuss how to prepare for AP® Spanish Language Free-Response section. Finally, this guide will provide you with AP® Spanish Language Exam tips to help you answer the free-response questions on the day of the test, and provide AP® Spanish Language practice questions.

What is the Format of the AP® Spanish Language Exam?

The AP® Spanish Language Exam is approximately three hours long and consists of two sections divided into several components.

The first section asks test takers to complete a number of listening and reading comprehension questions. Here students are asked to listen to prerecorded interviews, radio programs, podcasts, or to read articles from newspapers, web pages, special reports, or literature, and answer multiple choice questions about each of them.

The second section, also referred to as the “AP® Spanish Free-Response” section, lasts about one hour and 30 minutes. It deals with writing and speaking both informal and formal Spanish. The Interpersonal Writing component, for example, asks that students look over a document – an email, perhaps – and respond with a written answer. The Presentational Writing component asks students to draw together an argument from a number of sources like articles, tables, graphs, or an audio artifact to express their views on a particular topic.

Students also interact with documents in the informal and formal speaking component as well. In the Interpersonal Speaking component, test takers are given five listening passages meant to provoke conversation. Students then respond to the clip for about 20 seconds per question. The Presentational Speaking component asks that test takers speak for a bit longer – for two minutes, to be exact. Here they are given a prompt on a cultural topic, where they are asked to compare how such an issue may be similar or different in their own community and that of a Spanish-speaking country.

Why is the AP® Spanish Language Free-Response Important?

The AP® Spanish Language Exam is scored by a team of college faculty and seasoned AP® teachers trained in fair-mindedness and uniformity. This Free-Response section, like the multiple choice section, is 50% of your final exam grade – so it’s pretty important. The weighted scores from the Free-Response section are combined with those from a machine-graded multiple choice. These are summed and given an AP® composite score of a 5, 4, 3, 2, or 1 (5 being the highest and 1 being the lowest).

What Content is Covered in the Free-Response Section of the AP® Spanish Language Exam?

The exam tests the social, cultural, academic, and workplace skills you have been developing throughout your AP® Spanish course. In particular, test-takers are presented with questions on global challenges, science & technology, contemporary life, personal and public identities, families and communities, and beauty and aesthetics. Within these themes, students are asked to interact with an assortment of media, voice their opinions, and make connections and comparisons between English and Spanish speaking communities.

How can Test Takers Prepare for the AP® Spanish Language Free-Response Section?

In this section, you’ll find a few suggestions on how you can conduct your own AP® Spanish review during your free time. The CollegeBoard also offers some additional insights to get test-takers ready for test day. You can find out more by clicking here .

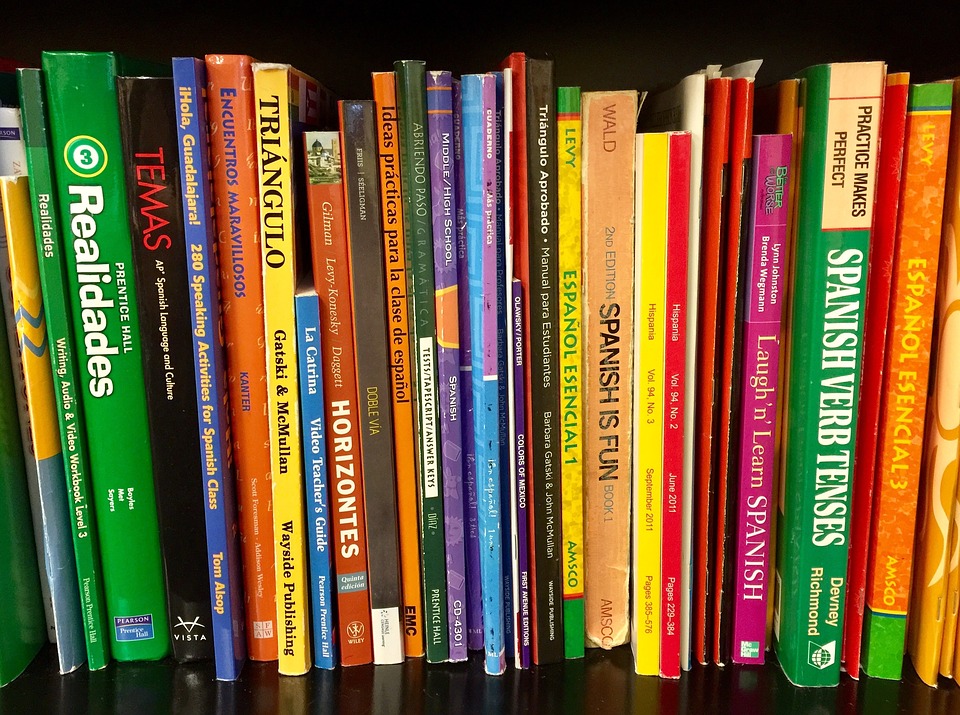

One way to prepare for the writing section of the exam is to look through various review books — in addition to your textbook, AP® Spanish: Preparing for the Language and Culture Examination by José M. Díaz, Prentice Hall’s Una Vez Más (Once More), or Triángulo (Triangle) by Barbara Gatski all come highly recommended. When looking through these books, check out a few practice questions that are modeled after writing prompts from the test. Doing a few practice drills will better acquaint you with the sorts of essay questions asked on the test. If your AP® Spanish teacher has the time, ask them to go over any mistakes you may have made while working out your answers.

You’ll improve your Spanish skills by speaking the language on a daily basis. As mentioned, the exam asks you to discuss various topics in Spanish, for times ranging from a few seconds to a few minutes. Practicing this skill will be invaluable. Without limiting yourself, speak in simple, frank sentences that use vocabulary and grammar you are most conversant in. Investing in a digital recorder so that you can practice speaking into it is one way to improve your oral communication skills while developing muscle memory for particular tough-to-pronounce Spanish sounds.

How can Test Takers Answer the AP® Spanish Language Free-Response Questions?

Albert offers test takers some useful tips to prepare them for the writing section of the AP® Spanish Language exam (see Albert’s The Ultimate List of AP® Spanish Language Tips for further details). Here are a few more insights regarding how you may want to tackle answering these during the exam.

AP® Spanish Language Essay Tips & Advice

- Begin your paragraphs with clear topic sentences and follow them with well-organized supporting sentences. Link paragraphs with transitional phrases like De esta manera, como resultado, además de eso.

- Write neatly in pen.

- If using difficult sentence structures, be sure you use them correctly. Practice these prior to the example so that you’ll have them down to a science!

- Incorporate each of the sources you’re being asked to discuss.

- Be sure to follow the directions so that you answer what is being asked of you. If, for example, an email prompt asks that you “include a greeting and a closing,” so be sure to include this in your reply.

- Show off your language skills by using the subjunctive.

- The Presentational Writing component asks that you write a persuasive essay. Be sure that you include a strong argument backed up with the sources provided to support your position. You may want to reference and disclaim the opposing arguments first, to strengthen your point.

Interpersonal and Presentational Speaking Examples and Tips

- Use the time you have to talk! If you get stuck, return to the main idea to help jog your memory.

- Rather than using filler words in English (ahh, but, so, and…), try Spanish fillers instead (pues, bueno, y, o sea, entonces… )

- Don’t be afraid to correct any mistakes you’ve made.

- Keep your Interpersonal Speaking answers casual.

- Be sure to address the task or answer the question presented to you.

- Consider who you are talking to and decide if you should use informal ( tú ) or formal ( Usted ) pronouns.

- Jot down an outline, grammar notes, or a vocabulary bank to glance upon in case you get stuck.

- The Presentational Speaking component is formal, so remember who your audience is and adjust accordingly.

- Stay organized by building your comparisons off of a thesis or main idea, then go into differences and similarities with supporting evidence. Remember to conclude with a summary of your arguments.

- Outline key ideas, but do not script what you want to say.

- Remember that in this section you are being asked to compare aspects of your culture with those of a Spanish-speaking culture. Jot down a Venn diagram or other visual tools to help you organize your claims.

- Research a few specifics on Spanish speaking countries so that you’ll have cultural references to draw from.

- Use transition words like además, por ejemplo, por otro lado, aunque, por el contrario…

- Remember it is okay to talk about your personal experiences. Use this to support your opinion.

What are the AP® Spanish Language Free-Response Questions Like?

Below you’ll find some examples of real Free-Response Questions from the CollegeBoard’s AP® Central (you can check out specific details and more sample questions here ). Try a few of these questions in the months before the test to ensure you are getting your fill of AP® Spanish practice!

Example 1 : You will write a reply to an e-mail message. You have 15 minutes to read the message and write your reply. Your reply should include a greeting and a closing and should respond to all the questions and requests in the message. In your reply, you should also ask for more details about something mentioned in the message. Also, you should use a formal method of address.

Example 2 : You will write a persuasive essay to submit to a Spanish writing contest. The essay topic is based on three accompanying sources, which present different viewpoints on the topic and include both print and audio material. First, you will have 6 minutes to read the essay topic and the printed material. Afterward, you will hear the audio material twice; you should take notes while you listen. Then, you will have 40 minutes to prepare and write your essay. In your persuasive essay, you should present the sources’ different viewpoints on the topic and also clearly indicate your own viewpoint and defend it thoroughly. Use information from all of the sources to support your essay. As you refer to the sources, identify them appropriately. Also, organize your essay into clear paragraphs.

Example 1 : You will participate in a conversation. First, you will have one minute to read a preview of the conversation, including an outline of each turn in the conversation. Afterward, the conversation will begin, following the outline. Each time it is your turn to speak, you will have 20 seconds to record your response. You should participate in the conversation as fully and appropriately as possible.

Example 2 : You will make an oral presentation on a specific topic to your class. You will have four minutes to read the presentation topic and prepare your presentation. Then you will have two minutes to record your presentation. In your presentation, compare your own community to an area of the Spanish-speaking world with which you are familiar. You should demonstrate your understanding of cultural features of the Spanish-speaking world. You should also organize your presentation clearly.

How can Test Takers Practice for the AP® Spanish Language Free-Response Section?

In summary, there are a lot of resources that test takers can draw from to help them with the AP® Spanish Language Free-Response section. Wrap your mind around as many interviews, radio programs, podcasts, newspapers, web pages, special reports, or literature in Spanish as you can handle. Meet with your fellow students or Spanish speakers in your community to attend Spanish cultural events and films, Discuss current global events; the latest tech gadgets; or your love, family, or work life. In other words, if you engage with the language on a daily basis, you’ll not only be developing skills that will help you practice for the test, but you’ll be opening yourself up to unique social worlds in new and dynamic ways.

Looking for AP® Spanish Language practice?

Kickstart your AP® Spanish Language prep with Albert. Start your AP® exam prep today .

Interested in a school license?

Popular posts.

AP® Score Calculators

Simulate how different MCQ and FRQ scores translate into AP® scores

AP® Review Guides

The ultimate review guides for AP® subjects to help you plan and structure your prep.

Core Subject Review Guides

Review the most important topics in Physics and Algebra 1 .

SAT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall SAT® score

ACT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall ACT® score

Grammar Review Hub

Comprehensive review of grammar skills

AP® Posters

Download updated posters summarizing the main topics and structure for each AP® exam.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

The AP Spanish Exam 2024: Your Complete Starter Guide

A three-hour long exam focused solely on Spanish? Sounds like a handful!

Luckily, studying for the exam and knowing what to expect can take the edge off the nerves and ensure you do your best. There are also plenty of great resources to help you practice for the exam.

Here’s everything you need to know about what’s included in the AP Spanish Language and Culture exam.

Why Take the AP Spanish Exam?

The 2023 ap spanish exam, section i: multiple choice and multiple choice with audio, section ii: free response written and free response spoken, what’s on the exam, multiple choice, free response, ap spanish themes, and one more thing….

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

First, to get yourself energized and ready to study, take a look at these motivating reasons to take the AP Spanish exam seriously:

- To earn college credits. This is terrific because it can save you the time and money required to take courses in college. The AP Spanish test costs about $100, but you can earn college credits with a score of at least 3 out of 5, saving you thousands of dollars and hundreds of hours.

- To prove your proficiency . Earning a passing score shows that you have some skills. You can use this to your advantage in the job market .

- To motivate yourself towards fluency . After all, you’ll need to study for the test. That test date will be a clear deadline for when your Spanish needs to be in tip-top shape. The College Board offers helpful materials like an in-depth course and exam description and a guide with examples from previous tests .

This year’s AP Spanish Language and Culture exam takes place on Wednesday, May 10 at 8 a.m. local time.

You’ll have 3 hours total to complete the whole test (including the multiple choice and free response sections):

For the print component of the multiple choice portion of the exam, you’ll read brief passages and answer multiple choice questions based on these passages.

Print and Audio

There will be two texts that use both audio and print. You’ll review both the print and the audio and then answer multiple choice questions on them.

You can take notes during the listening passages, so this should help you keep track of the material.

Audio passages will be played twice. Each time you listen to a passage, you’ll have some time to answer the accompanying multiple choice questions.

Remember to take notes so that you remember what the passages cover!

Interpersonal Writing

In this section, you’ll write a brief reply to an example email. Don’t forget to include a greeting, closing , answers to its questions and follow-up questions of your own.

Be sure to brush up on usted (formal “you”) since this email is expected to be formal. Learn how to write your formal Spanish emails here !

Using varied language is also an important way to show off your knowledge of vocabulary , so don’t lean too heavily on similar phrases.

Presentational Writing

This section presents you with a topic and materials and asks you to write a persuasive essay based on them. You’ll have some time to review the print and audio material before you begin writing, and you’re welcome to take notes (which you definitely should).

You’ll need to present both sides of the argument while also expressing your own perspective using the materials provided to support your ideas. Obviously, your Spanish writing matters here, but so do your comprehension and writing skills in general.

Try to incorporate information from all the sources within your final product. Don’t forget to use everything you’ve learned about writing essays in your English class. If you’re unfamiliar with this style of writing, Purdue’s Online Writing Lab has a helpful guide .

For specific Spanish phrases you can use and more AP free response writing advice, see this post:

Want to ace the AP Spanish essay section? Then learn these 52 persuasive essay phrases in Spanish and watch your writing improve. Make the free-response section of the AP…

Interpersonal Speaking

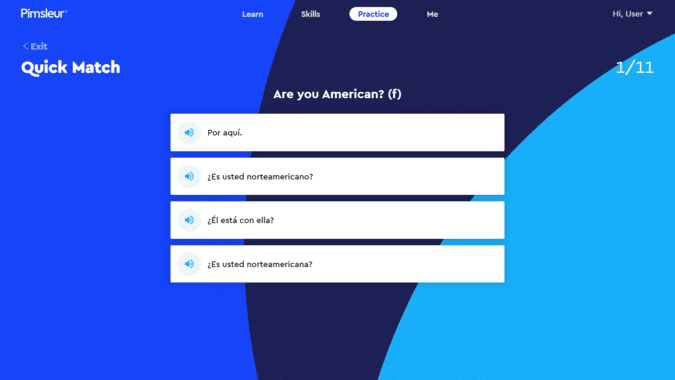

This section simulates a conversation. You’ll receive a brief outline of the conversation that you can use as a reference to keep track of what’s happening and what your conversational goals are. Then, you’ll hear a brief passage and give a brief response. Since this is a conversation, it’s appropriate to use tú (informal “you”).

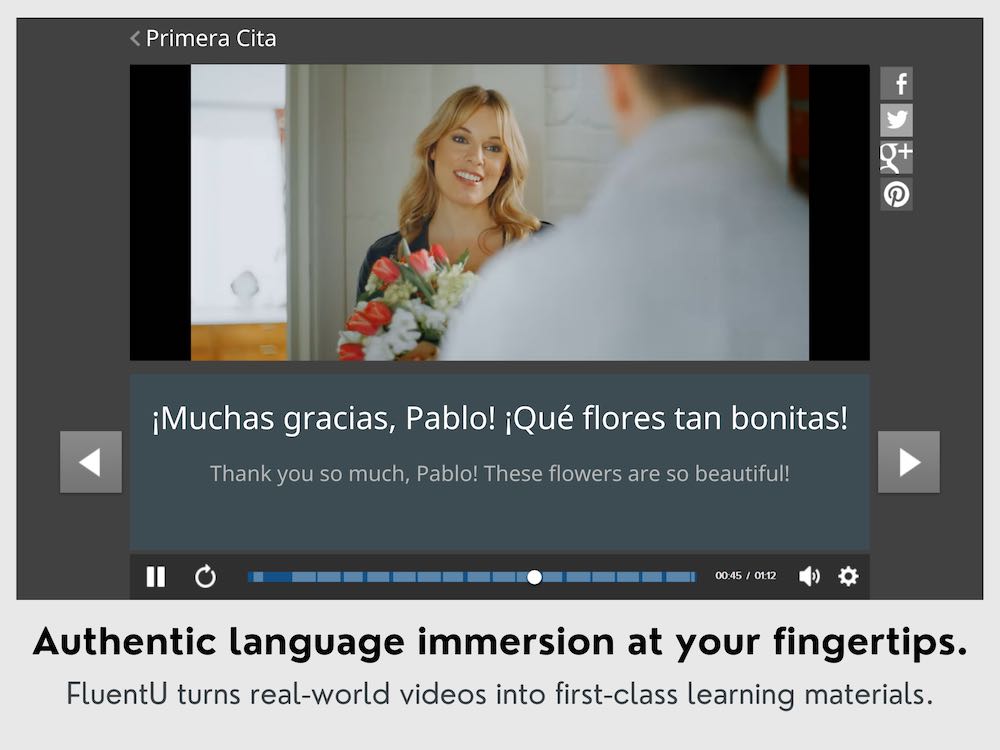

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Try FluentU for FREE!

Presentational Speaking

This section is short but intense. You’ll have four minutes to read material and prepare a presentation followed by two minutes to deliver your presentation. The section focuses on the general topic of cultural comparison, but its precise focus varies between exams.

Here, it’s important to think on your feet. You won’t have a lot of time to prepare, so being able to think about the topic in Spanish rather than translating will save you valuable time.

Not only should you illustrate your command of the Spanish language, you should also show some knowledge of culture. If you make any mistakes, you can always correct yourself, but make sure that your correction is clear.

The AP Spanish exam employs various “themes” to conceptualize the content it will include.

It’s important to note that you won’t be quizzed on these topics. However, the content of the test itself is based on these themes, so some familiarity with them is helpful. Studying vocabulary related to these themes will help provide you with words you may need on the exam.

Science and Technology: Science and Ethics, Healthcare and Medicine, Access to and Effects of Technology

Global Challenges: Philosophy/Religion, Economic Changes, Environment, Social Conscience and Welfare

Contemporary Life: Entertainment, Travel and Leisure, Education/Careers, Social Customs and Values

Families and Communities: Family Structure, Customs and Values, Education, Social Networking

Personal and Public Identities: Personal Beliefs and Interests, National and Ethnic Identities, Heroes/Historical Figures

Beauty and Aesthetics: Defining Beauty and Creativity, Fashion/Design/Architecture, Visual and Performing Arts, Language and Literature

Now that you know more about the exam, it doesn’t seem so intimidating, does it?

Just remember that the exam changes periodically, so it’s important to check the College Board website .

With a little preparation, you’ll be ready to pass the AP Spanish exam and earn college credit!

If you've made it this far that means you probably enjoy learning Spanish with engaging material and will then love FluentU .

Other sites use scripted content. FluentU uses a natural approach that helps you ease into the Spanish language and culture over time. You’ll learn Spanish as it’s actually spoken by real people.

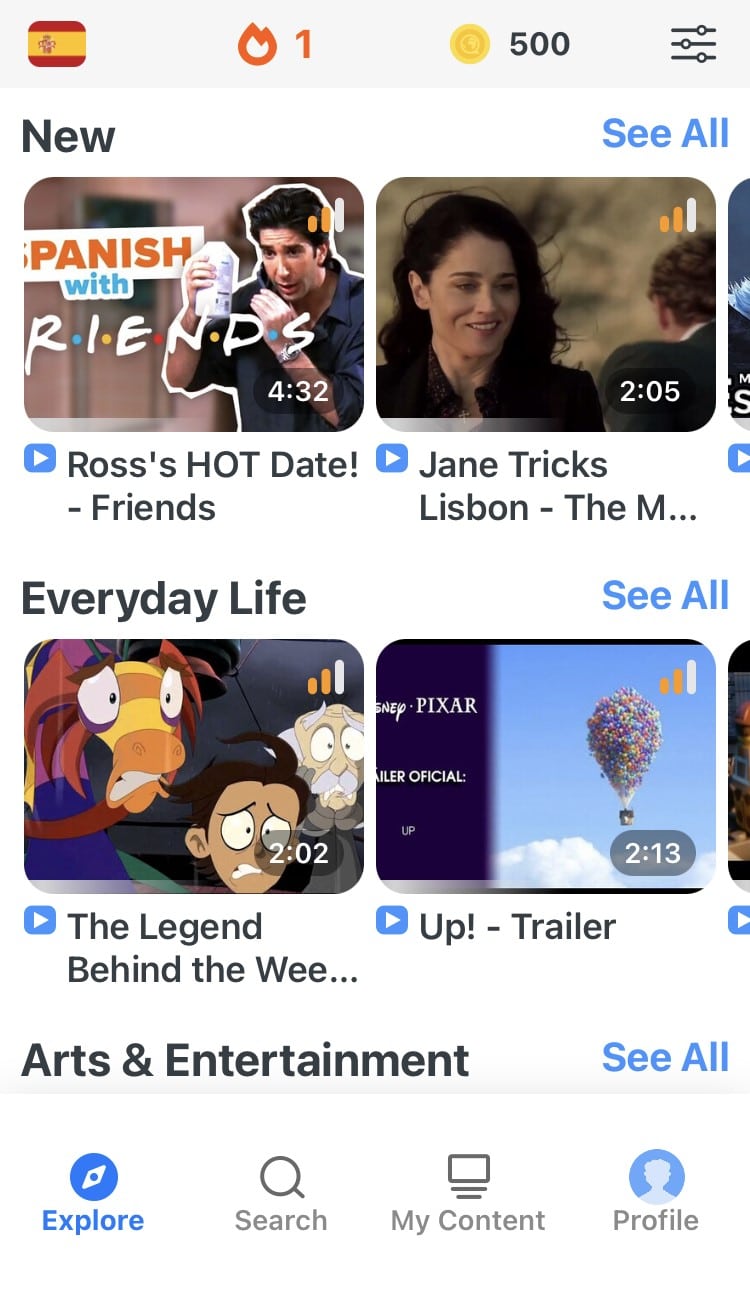

FluentU has a wide variety of videos, as you can see here:

FluentU brings native videos within reach with interactive transcripts. You can tap on any word to look it up instantly. Every definition has examples that have been written to help you understand how the word is used. If you see an interesting word you don’t know, you can add it to a vocab list.

Review a complete interactive transcript under the Dialogue tab, and find words and phrases listed under Vocab .

Learn all the vocabulary in any video with FluentU’s robust learning engine. Swipe left or right to see more examples of the word you’re on.

The best part is that FluentU keeps track of the vocabulary that you’re learning, and gives you extra practice with difficult words. It'll even remind you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. Every learner has a truly personalized experience, even if they’re learning with the same video.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. All annual subscriptions now on sale!

Enter your e-mail address to get your free PDF!

We hate SPAM and promise to keep your email address safe

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

Ultimate Guide to the AP Spanish Language and Culture Exam

Do you know how to improve your profile for college applications.

See how your profile ranks among thousands of other students using CollegeVine. Calculate your chances at your dream schools and learn what areas you need to improve right now — it only takes 3 minutes and it's 100% free.

The AP Spanish courses are the most popular AP foreign language classes. In fact, they’re so popular that two sets of Spanish curricula exist: AP Spanish Language and Culture and AP Spanish Literature and Culture. This is the only AP foreign language that has more than one course offering. In 2019, over 185,000 students took the AP Spanish Language and Culture exam, making it by far the most popular foreign language exam taken.

The curriculum for the AP Spanish Language and Culture exam emphasizes communication by applying interpersonal, interpretive, and presentational skills in real-life situations. As you undertake the coursework or exam preparations, you will need to focus on understanding others and being understood by others. If you’re planning to take the AP Spanish Language and Culture exam, whether you have taken the class, are a native speaker, or have self-studied, read on for a breakdown of the test and CollegeVine’s advice for how to best prepare.

When is the AP Spanish Language and Culture Exam?

The College Board will administer the 2020 AP Spanish Language and Culture exam on Tuesday, May 12, at 8 am. For a complete list of all the AP exams, along with tips for success and information about how students score, check out our article 2020 AP Exam Schedule: Everything You Need to Know.

About the AP Spanish Language and Culture Exam

The AP Spanish Language and Culture course is taught almost exclusively in Spanish and includes instruction in vocabulary usage, language control, communication strategies, and cultural awareness.

Although there is some emphasis placed on correct grammar usage, the College Board specifically warns against overemphasizing grammatical accuracy at the expense of communication. Instead, more time will be spent on applying interpersonal, interpretive, and presentational communication skills in real-life situations, exploring the culture in both contemporary and historical contexts, and building an awareness and appreciation of cultural products, practices, and perspectives.

There are no explicit prerequisites for the AP Spanish Language and Culture course, but students who take it are typically in their fourth year of high school-level Spanish language study or have extensive practical experience communicating in both written and oral Spanish language.

There are four essential components to the framework of the AP Spanish Language and Culture course that clarify what you must know, be able to do, and understand to qualify for

college credit or placement. Those components are skills, themes, modes, and task models.

Skills: Skills are the abilities you’ll need to think and act like a Spanish speaker. The College Board breaks these skills into eight units; below is a list of those units along with the weight they are given on the multiple-choice section of the AP Spanish Language and Culture exam:

Themes: The AP Spanish Language and Culture course is divided into 6 themes in which there are 5-7 contexts covered. Below are the 6 themes along with their recommended contexts:

Modes: To pass the AP Spanish Language and Culture exam, students need to demonstrate proficiency engaging in three modes of communication: interpretive, interpersonal, and presentational. Students need to possess skills in listening, reading, speaking, and writing in the following areas:

- Audio, Visual, and Audiovisual Interpretive Communication

- Written and Print Interpretive Communication

- Spoken Interpersonal Communication

- Written Interpersonal Communication

- Spoken Presentational Communication

- Written Presentational Communication

Task Model: Finally, you will work with various task models to demonstrate linguistic skills and cultural understanding. The task model types are:

AP Spanish Language and Culture Exam Content

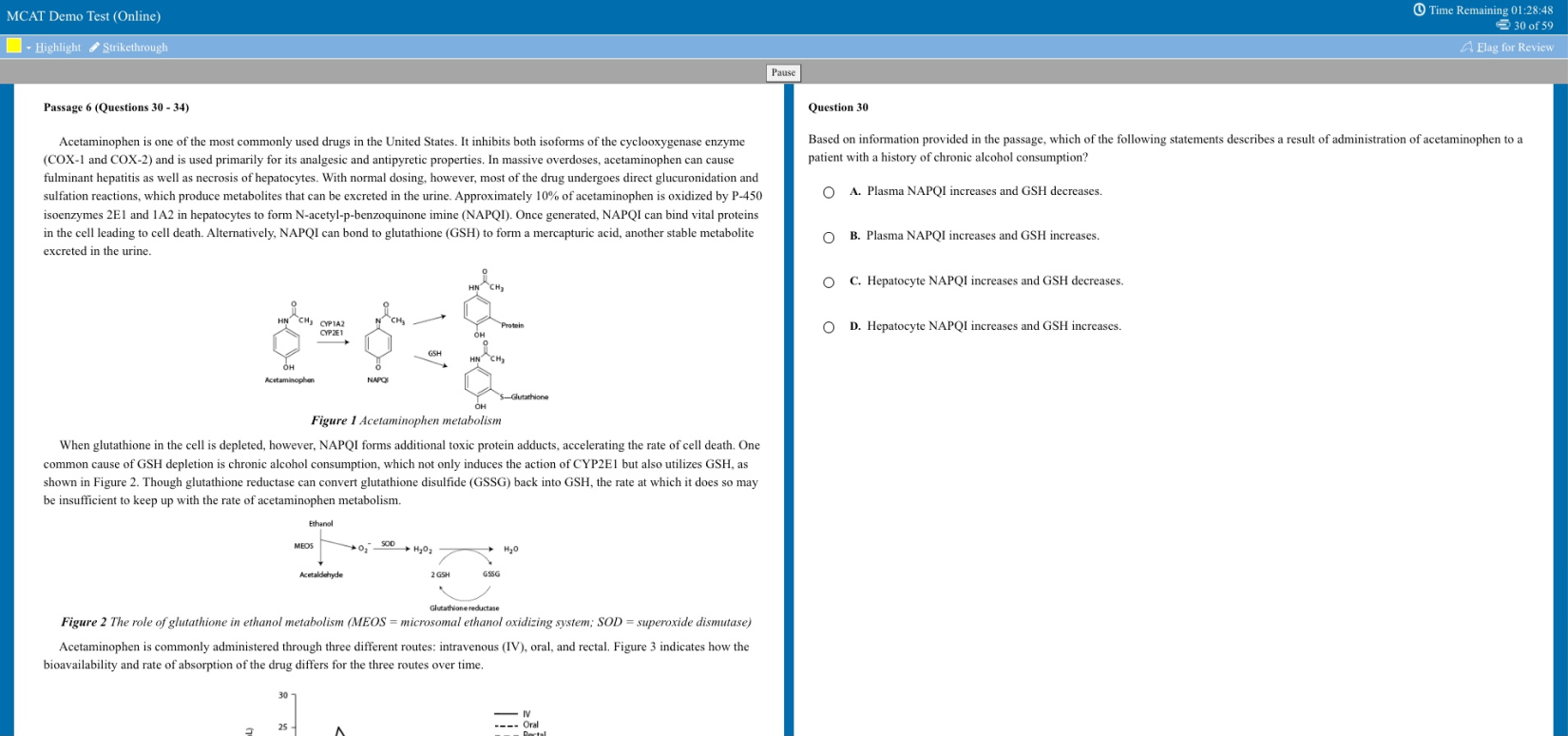

At 3 hours and 3 minutes long, the AP Spanish Language and Culture exam is one of the longer-lasting AP exams. It consists of two primary sections—the first section featuring multiple-choice questions, and the second made up of free response questions.

The multiple-choice questions are further broken down into two parts—one part based on text as a stimulus, the other part uses audio as a stimulus.

Section 1(a): Multiple-Choice Text

40 minutes | 30 questions | 23% of score

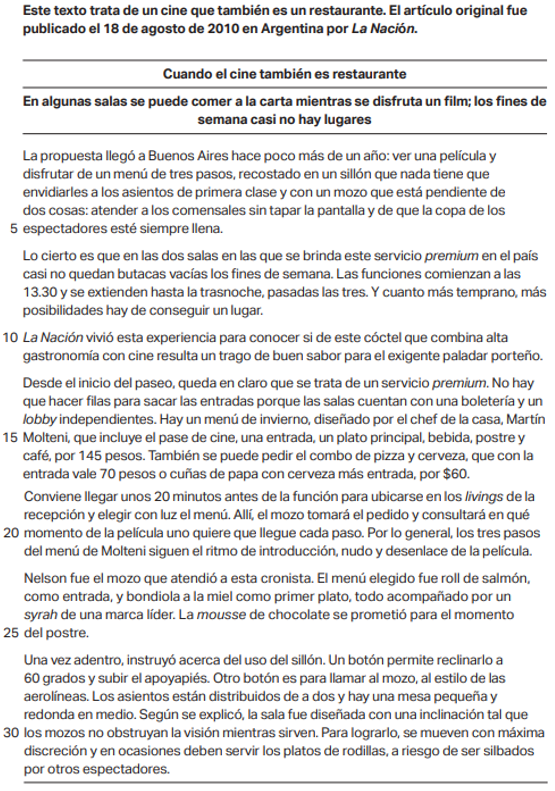

The first part of the AP Spanish Language and Culture exam uses a variety of printed materials—journalistic and literary texts, announcements, advertisements, letters, charts, maps, and tables—as a stimulus. You’re asked to identify ideas and details, define words in context, identify an author’s point of view or target audience, and demonstrate knowledge of cultural or interdisciplinary information contained in the text.

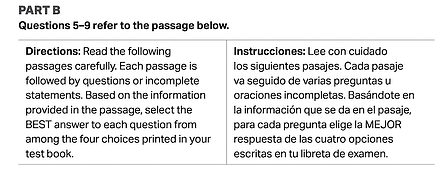

Example of a text-based multiple-choice question:

Answers to multiple-choice questions above:

Section 1(b): Multiple-Choice Audio

55 minutes | 35 questions | 27% of score

The second part of the multiple-choice section uses audio material—interviews, podcasts, PSAs, conversations, and brief presentations—as a stimulus. In this part of the exam, students will encounter two subsections of questions.

- In the first subsection, you’re asked to answer questions using two audio sources and related print materials as a stimulus.

- The second subsection uses three audio sources (and no print material) as the stimulus.

Example of a question you’ll encounter in the audio-based multiple-choice section, click on the question for audio:

Answers to the multiple choice questions above:

The free-response section of the AP Spanish Language and Culture exam is also broken down into two parts—one part focusing on writing, and the other on speaking.

Section 2 (a): Free Response Written

1 hour 10 minutes | 2 questions | 25% of score

The first free response section features two questions—one on interpersonal writing and the other on presentational writing. The first of the two questions require you to read and respond to an email. You have 15 minutes to complete this section, and it’s worth 12.5% of your exam score. The second of these questions provides three sources—including an article, a table, graph, chart, or infographic, and a related audio source offering different viewpoints on a topic—that you will use to construct an argumentative essay. This question is allotted 55 minutes (15 minutes to review materials and 40 minutes to write) and is also worth 12.5% of your exam score.

Example of an email free-response question:

Section 2: Free Response Spoken

18 minutes | 2 questions | 25% of score

The spoken part of the free response section tests your interpersonal and presentational speaking ability. For interpersonal speaking, you will participate in five exchanges in a simulated conversation with 20 seconds for each response. For the second part, you’re tasked with delivering a two-minute presentation requiring you to compare a cultural feature of a Spanish-speaking community to another community you are familiar with.

When delivering oral responses, you will be digitally recorded and your proctor will submit your recordings with the rest of your test materials. Learn more about submitting audio on the College Board’s webpage of the same name, Submitting Audio .

Example of a spoken, presentational, free-response question:

AP Spanish Language and Culture Score Distribution, Average Score, and Passing Rate

In 2019, students generally did quite well on the AP Spanish Language and Culture exam. More than half of all students received a score of 4 or 5, and nearly 90% of test-takers received a passing score (3 or higher). Though students who regularly spoke or heard Spanish outside of school did perform slightly better overall than the standard group of foreign language students, the standard group still passed the exam at a rate of nearly 85% and only 3% received the lowest score of a 1.

To guide your studying, read the full AP Spanish course description . For a comprehensive listing of the score distribution on all of the AP exams, check out our post Easiest and Hardest AP Exams .

Best Ways to Study for the AP Spanish Language and Culture Exam

Step 1: start by assessing your skills.

It’s important to start your studying off with a good understanding of your existing knowledge. Although the College Board does not provide a complete practice test, you can find sample questions with scoring explanations included in the course description . Additionally, you can find a free AP Spanish Language and Culture diagnostic test from Varsity Tutors. You may also find practice or diagnostic exams in many of the commercially printed study guides.

Step 2: Study the Material

In the case of the AP Spanish Language and Culture course, the theory you’ll need to know falls into six themes (Beauty and Aesthetics, Contemporary Life, Families and Communities, Global Challenges, Personal and Public Identities, Science and Technology). Many textbooks will be divided into units based on these themes. Even if they are not, you should find threads of them throughout your studies.

Of course, the best way to study a foreign language is to truly immerse yourself in it. Although your course will be taught primarily in Spanish, this will account for only a tiny percentage of your day. You should find other ways to further your exposure to the Spanish language, and given the prevalence of Spanish in our own contemporary culture, this should not be difficult. You can easily find engaging young adult books written in Spanish, interesting Youtube videos or TV shows in Spanish, or even Spanish podcasts. Check out comic books, news, or websites in Spanish. Make sure you are speaking, listening to, and reading Spanish as much as possible, even outside of your regular study or class hours.

The College Board also provides some valuable study tools for your use. Reviewing the AP Spanish Language and Culture Course and Exam Description can help you to more deeply understand the course content and format. You should also review the exam audio files and the official Exam Practice Tips to help guide your studying.

In addition, you should take advantage of the many commercial study guides available for your use. One of the top-rated AP Spanish Language and Culture study guides is the Princeton Review’s Cracking the AP Spanish Language & Culture Exam with Audio CD, 2020 Edition . This compilation of content reviews and strategies also contains two full-length practice tests with complete answer explanations and access to the Princeton Review’s AP Connect portal online. Another great option is Barron’s AP Spanish Language and Culture with MP3 CD, 8th Edition , which again contains two full-length practice exams with audio sections for both practice exams.

There are also vast amounts of study materials available online. Taking one of the more popular AP exams means that many students have been in your shoes, and often they or their teachers have posted past materials to supplement their studying. You can find a huge database of resources including sound files, Spanish reading sites, and grammar sites— this site is a good place to get started.

Finally, apps are a relatively new and fun way to squeeze in a little more studying. The Fluent U app is a great option for AP foreign languages. The basic version is free, but watch out for in-app purchases. The premium versions can set you back between $30 and $240 dollars.

Step 3: Practice Multiple-Choice Questions

Once you’ve got a good handle on the major course content and theory, you can begin putting it to use. Start by practicing multiple-choice questions. You will be able to find plenty of these available online (for example, study.com has a free 50-question online practice test ) for the AP Spanish Language and Culture exam, or you can try the practice ones provided in commercial study guides.

The College Board course description also contains a number of multiple-choice questions with answers and explanations. As you are reviewing these, keep track of which broad content areas are coming easily to you and which still require more effort. Think about what each question is really asking you to do, and keep a list of vocabulary, grammar, and content areas that still seem unfamiliar. These will be points for more review before you move on.

Step 4: Practice Free Response Questions

Even if you’ve studied for the free response section of other APs in the past, your studies for the free response section of the foreign language AP exams will be quite different. In addition to practicing your written responses, you’ll also need to fine-tune your listening skills and oral responses.

Begin your preparations by brushing up on your vocabulary and grammar. Make sure you have a handle on a broad variety of verbs and how to conjugate each. Also, reaffirm that your knowledge of vocabulary will allow you to express yourself as fluently as possible. A great tool for this is a supplementary set of Barron’s AP Spanish Flash Cards . These cards emphasize word usage within the context of sentences and review parts of speech, noun genders, verb forms and tenses, and correct sentence structure.

Beyond vocabulary and grammar, your studies should also include practicing written and oral responses. The best way to specifically prepare for both the written and spoken portions of your free response questions is to practice repeated similar prompts. There is a huge resource of past free response questions available on College Board’s website dating back to 1999, with accompanying scoring explanations and examples of authentic student responses.

To make the most of these example free response questions, review the Chief Reader Report on Student Responses wherein the Chief Reader of the AP Exam compiles feedback to describe how students performed on the prompts, summarizes typical student errors, and addresses specific concepts and content with which students have struggled the most.

It can be especially difficult to prepare for the oral portion of your free response section since it’s difficult to identify your own spoken errors. Try recording your responses and comparing them to the authentic student responses available above. Alternatively, collaborate with a classmate to record and trade responses, offering one another constructive criticism framed by the scoring examples available above.

Step 5: Take Another Practice Test

Just as you took a practice test at the beginning of your preparations to gauge your readiness for the exam, do so again after a thorough review of the course content and each exam portion. Identify the areas in which you’ve improved the most, and areas still in need of improvement. If time allows, repeat the steps above to incrementally increase your score with each pass.

Step 6: Exam Day Specifics

If you’re taking the AP course associated with this exam, your teacher will walk you through how to register. If you’re self-studying, check out our blog post How to Self-Register for AP Exams .

For information about what to bring to the exam, see our post What Should I Bring to My AP Exam (And What Should I Definitely Leave at Home)?

Want access to expert college guidance — for free? When you create your free CollegeVine account, you will find out your real admissions chances, build a best-fit school list, learn how to improve your profile, and get your questions answered by experts and peers—all for free. Sign up for your CollegeVine account today to get a boost on your college journey.

For more information about APs, check out these CollegeVine posts:

- 2020 AP Exam Schedule

- How Long is Each AP Exam?

- Easiest and Hardest AP Exams

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

RU Penza Oblast

Recently viewed courses

Recently viewed.

Find Your Dream School

This site uses various technologies, as described in our Privacy Policy, for personalization, measuring website use/performance, and targeted advertising, which may include storing and sharing information about your site visit with third parties. By continuing to use this website you consent to our Privacy Policy and Terms of Use .

COVID-19 Update: To help students through this crisis, The Princeton Review will continue our "Enroll with Confidence" refund policies. For full details, please click here.

Enter your email to unlock an extra $25 off an SAT or ACT program!

By submitting my email address. i certify that i am 13 years of age or older, agree to recieve marketing email messages from the princeton review, and agree to terms of use., guide to the ap spanish language & culture exam.

The AP ® Spanish Language and Culture Exam is a college-level exam administered every year in May upon the completion of an Advanced Placement Spanish Language course taken at your high school. If you score high enough, you could earn college credit!

Check out our AP Spanish Guide for the essential info you need about the exam:

- AP Spanish Exam Overview

- AP Spanish Sections & Question Types

- AP Spanish Scoring

- How to Prepare

What's on the AP Spanish Language & Culture Exam?

The College Board requires your AP teacher to cover certain topics in the AP Spanish Language & Culture course. As you complete your review, make sure you are familiar with the following topics:

- Families in Different Societies

- The Influence of Language and Culture on Identity

- Influences of Beauty and Art

- How Science and Technology Affect Our Lives

- Factors That Impact the Quality of Life

- Environmental, Political, and Societal Challenges

For helpful exam review and test-taking strategies, check out our book, AP Spanish Language & Culture Prep

Sections & Question Types

The AP Spanish Language & Culture Exam is just over 3 hours long to complete and is comprised of two sections: a multiple-choice section and a free-response section. There are two parts to the multiple-choice section, and four questions in the free-response section.

Part A Multiple-Choice Questions

The first part of the multiple-choice section contains sets of questions based on one or more print text sources.

Part B Multiple-Choice Questions

The second part of the multiple-choice section contains sets of questions based on audio text sources, as well as a combination of audio and print text sources.

Free-Response Questions

- In Question 1: Email Reply, students are required to compose a formal email response in Spanish. They must include a greeting, a closing, and respond to all questions and requests in the incoming email. They must also ask for details about something mentioned in the incoming email.

- In Question 2: Argumentative Essay, students are required to write an essay as a submission to a Spanish writing contest. The topic is based on three sources, a combination of audio and print sources. The students must form an argument, defend their position, and integrate information from all three sources into their essay.

- In Question 3: Conversation, a student must participate in a simulated conversation where they have five turns in the conversation. They have 20 seconds to respond in each turn.

- In Question 4: Cultural Comparison, the student must compare an aspect of a Spanish-speaking community with the student’s own, or another, community. They must demonstrate an understanding of the cultural features of this Spanish-speaking community with an organized and clear presentation, using varied and appropriate language.

Read More: Review for the exam with our AP Psychology Crash Courses

What’s a good AP Spanish Score?

AP scores are reported from 1 to 5. Colleges are generally looking for a 4 or 5 on the AP Spanish Language & Culture exam, but some may grant credit for a 3. Here’s how students scored on the May 2020 test:

Source: College Board

How can I prepare?

AP classes are great, but for many students they’re not enough! For a thorough review of AP Spanish content and strategy, pick the AP prep option that works best for your goals and learning style.

- AP Exams

Explore Colleges For You

Connect with our featured colleges to find schools that both match your interests and are looking for students like you.

Career Quiz

Take our short quiz to learn which is the right career for you.

Get Started on Athletic Scholarships & Recruiting!

Join athletes who were discovered, recruited & often received scholarships after connecting with NCSA's 42,000 strong network of coaches.

Best 389 Colleges

165,000 students rate everything from their professors to their campus social scene.

SAT Prep Courses

1400+ course, act prep courses, free sat practice test & events, 1-800-2review, free digital sat prep try our self-paced plus program - for free, get a 14 day trial.

Free MCAT Practice Test

Thank you! Look for the MCAT Review Guide in your inbox.

I already know my score.

Enrollment Advisor

1-800-2REVIEW (800-273-8439) ext. 1

1-877-LEARN-30

Mon-Fri 9AM-10PM ET

Sat-Sun 9AM-8PM ET

Student Support

1-800-2REVIEW (800-273-8439) ext. 2

Mon-Fri 9AM-9PM ET

Sat-Sun 8:30AM-5PM ET

Partnerships

- Teach or Tutor for Us

College Readiness

International

Advertising

Affiliate/Other

- Enrollment Terms & Conditions

- Accessibility

- Cigna Medical Transparency in Coverage

Register Book

Local Offices: Mon-Fri 9AM-6PM

- SAT Subject Tests

Academic Subjects

- Social Studies

Find the Right College

- College Rankings

- College Advice

- Applying to College

- Financial Aid

School & District Partnerships

- Professional Development

- Advice Articles

- Private Tutoring

- Mobile Apps

- Local Offices

- International Offices

- Work for Us

- Affiliate Program

- Partner with Us

- Advertise with Us

- International Partnerships

- Our Guarantees

- Accessibility – Canada

Privacy Policy | CA Privacy Notice | Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information | Your Opt-Out Rights | Terms of Use | Site Map

©2024 TPR Education IP Holdings, LLC. All Rights Reserved. The Princeton Review is not affiliated with Princeton University

TPR Education, LLC (doing business as “The Princeton Review”) is controlled by Primavera Holdings Limited, a firm owned by Chinese nationals with a principal place of business in Hong Kong, China.

Find what you need to study

2024 AP Spanish Language and Culture Exam Guide

8 min read • august 18, 2023

Attend a live cram event

Review all units live with expert teachers & students

Your Guide to the 2024 AP Spanish Language and Culture Exam

We know that studying for your AP exams can be stressful, but Fiveable has your back! We created a study plan to help you crush your AP Spanish Language and Culture exam . This guide will continue to update with information about the 2024 exams, as well as helpful resources to help you do your best on test day. Unlock Cram Mode for access to our cram events—students who have successfully passed their AP exams will answer your questions and guide your last-minute studying LIVE! And don't miss out on unlimited access to our database of thousands of practice questions. FYI, something cool is coming your way Fall 2023! 👀

Format of the 2024 AP Spanish Language and Culture Exam

This year, all AP exams will cover all units and essay types. The 2024 AP Spanish Lang exam format will be:

Reading Multiple Choice - 23% of your score

30 questions in 40 minutes

Reading/ Listening Multiple Choice - 27% of your score

35 questions in 55 minutes

Email Reply - 12.5% of your score

15 minutes

Argumentative Essay - 12.5% of your score

Conversation - 12.5% of your score

~ 2 minutes

Cultural Comparison - 12.5% of your score

~ 6 minutes

Scoring Rubric for the 2024 AP Spanish Language and Culture Exam

Check out our study plan below to find resources and tools to prepare for your AP Spanish Language and Culture exam !

When is the 2024 AP Spanish Language and Culture Exam and How Do I Take It?

How should i prepare for the exam.

First, download the AP Spanish Language Cheatsheet PDF - a single sheet that covers everything you need to know at a high level. Take note of your strengths and weaknesses!

Review every unit and question type, and focus on the areas that need the most improvement and practice. We’ve put together this plan to help you study between now and May. This will cover all of the units and essay types to prepare you for your exam

Try to immerse yourself in Spanish: watching movies or videos, chatting with friends, and reading news in Spanish will help you be more fluent by the time the exam comes!

We've put together the study plan found below to help you study between now and May. This will cover all of the units and essay types to prepare you for your exam. Pay special attention to the units that you need the most improvement in.

Study, practice, and review for test day with other students during our live cram sessions via Cram Mode . Cram live streams will teach, review, and practice important topics from AP courses, college admission tests, and college admission topics. These streams are hosted by experienced students who know what you need to succeed.

Pre-Work: Set Up Your Study Environment

Before you begin studying, take some time to get organized.

🖥 Create a study space.

Make sure you have a designated place at home to study. Somewhere you can keep all of your materials, where you can focus on learning, and where you are comfortable. Spend some time prepping the space with everything you need and you can even let others in the family know that this is your study space.

📚 Organize your study materials.

Get your notebook, textbook, prep books, or whatever other physical materials you have. Also, create a space for you to keep track of review. Start a new section in your notebook to take notes or start a Google Doc to keep track of your notes. Get yourself set up!

📅 Plan designated times for studying.

The hardest part about studying from home is sticking to a routine. Decide on one hour every day that you can dedicate to studying. This can be any time of the day, whatever works best for you. Set a timer on your phone for that time and really try to stick to it. The routine will help you stay on track.

🏆 Decide on an accountability plan.

How will you hold yourself accountable to this study plan? You may or may not have a teacher or rules set up to help you stay on track, so you need to set some for yourself. First, set your goal. This could be studying for x number of hours or getting through a unit. Then, create a reward for yourself. If you reach your goal, then x. This will help stay focused!

🤝 Get support from your peers.

There are thousands of students all over the world who are preparing for their AP exams just like you! Join Rooms 🤝 to chat, ask questions, and meet other students who are also studying for the spring exams. You can even build study groups and review material together!

AP Spanish Language and Culture 2024 Study Plan

👨👨👧 unit 1: families in different societies.

Unit 1 dives into the various themes related to families in the Spanish-speaking world. Some major questions we will consider are:

What constitutes a family in Spanish-speaking societies? / ¿Qué compone una familia en una sociedad hispanohablante?

What are some important aspects of family values and family life in Spanish-speaking societies? / ¿Cuáles son algunos aspectos importantes de los valores y la vida familiar en las sociedades hispanohablantes?

What challenges do families face in today's world? / ¿Qué retos enfrentan las familias de hoy?

Some Resources:

📚 Read these study guides:

Unit 1 Overview

1.1 Families in Different Societies

1.2 Family Customs and Values

1.3 Challenges Families Face in Spanish-Speaking Countries

1.4 Global Challenges

1.5 Possible Prompts for Unit 1

If you have more time or want to dig deeper:

💻 Learn about the best prep books so you can start studying early:

Best AP Spanish Language Textbooks and Prep Books

🗣 Unit 2: The Influence of Language and Culture on Identity

This unit plunges deeper into a few aspects of personal and public identity by analyzing the influences that language and culture have on forming one's identity. Our guiding questions for this unit are:

How does one’s identity evolve over time? / ¿Cómo se desarrolla nuestra identidad a lo largo del tiempo?

How does language shape our cultural identity? / ¿Cómo moldea la lengua nuestra identidad cultural?

How does technology influence the development of personal and public identity? / ¿Cómo influye la tecnología en el desarrollo de la identidad pública y personal?

How does the art of a community reflect its public identify? / ¿Cómo refleja el arte de una comunidad su identidad pública?

Unit 2 Overview

2.1 The Influence of Language and Culture on Identity

2.2 Beauty and Aesthetics

2.3 Contemporary Life

2.4 Science and Technology

Possible Prompts for Unit 2

💻 It is never too early to want to prepare for the exam:

🏆 How to Get a 5 in AP Spanish Language

🎨 Unit 3: Influences of Beauty and Art

This unit guide will explore how beauty and art influence quality of life and values in Spanish-speaking communities.

How do ideals of beauty and aesthetics influence daily life? / ¿Cómo influyen los ideales/ modelos de belleza y estética en la vida diaria?

How does art both challenge and reflect cultural perspectives? / ¿Cómo el arte desafía y a la vez refleja las perspectivas culturales?

How do communities value beauty and art? / ¿Cómo valoran las comunidades la belleza y el arte?

How is art used to record history? / ¿Cómo se usa el arte para documentar la historia?

Unit 3 Overview: Influences of Beauty and Art

3.1 Beauty and Aesthetics

3.2 Personal and Public Identities

3.3 Contemporary Life

3.4 Families and Communities

💻 Check out these AP Spanish Language Self-Study/Homeschool tips:

🏠 AP Spanish Language Self-Study and Homeschool

🔬 Unit 4: How Science and Technology Affect Our Lives

This unit will explore how science and technology affect the lives of those living in Spanish-speaking communities.

What factors drive innovation and discovery in the fields of science and technology ? / ¿Qué factores impulsan la innovación y los descubrimientos en los campos de la ciencia y la tecnología?

What role do ethics play in scientific advancement? / ¿Qué papel juega la ética en los avances científicos?

What are the social consequences of scientific or technological advancements? / ¿Cuáles son las consecuencias sociales de los avances científicos y tecnológicos?

Unit 4 Overview: How Science and Technology Affect Our Lives

4.1 Science and Technology

4.2 Global Challenges

4.3 Contemporary Life

4.4 Personal and Public Identities

Possible Prompts for Unit 4

🏘️ Unit 5: Factors That Impact the Quality of Life

This unit will dive into some specific factors that impact our quality of life.

How do aspects of everyday life influence and relate to the quality of life? / ¿Cómo influyen y se relacionan los aspectos de la vida diaria con la calidad de vida?

How does where one live impact the quality of life? / ¿Cómo impacta la calidad de vida el lugar donde se vive?

What influences one’s interpretation and perceptions of the quality of life? / ¿Qué influye en nuestra interpretación y en nuestras percepciones de la calidad de vida?

Unit 5 Overview: Factors that Impact the Quality of Life

5.1 Contemporary Life

5.2 Global Challenges

5.3 Science and Technology

5.4 Beauty and Aesthetics

5.5 Tourism and Cuisine

⛈️ Unit 6: Environmental, Political, and Societal Challenges

This last unit explores how global challenges and complex issues impact people's lives in the Spanish-speaking world. Some guiding questions are:

How do environmental, political, and societal challenges positively and negatively impact communities? / ¿Cómo los desafíos medioambientales, políticos y sociales impactan, positiva—o negativamente— nuestras comunidades?

What role do individuals play in addressing complex societal issues? / ¿Qué papel juegan los individuos a la hora de abordar asuntos sociales complicados?

How do challenging issues affect a society’s culture? / ¿Cómo los asuntos desafiant es afectan la cultura de una sociedad?

Unit 6 Overview: Environmental, Political, and Societal Changes

6.1 Economic Issues

6.2 Contemporary Life

6.3 Population and Demographics

6.4 Families and Communities

6.5 Possible Prompts for Unit 6

Key Terms to Review ( 18 )

AP Spanish Language and Culture exam

Argumentative Essay

Beauty and Aesthetics

Challenges Families Face in Spanish-Speaking Countries

College Board

Contemporary Life

Conversation

Cultural Comparison

Email Reply

Environmental Challenges

Families in Different Societies

Family Customs and Values

How Science and Technology Affect Our Lives

Influences of Beauty and Art

Listening Multiple Choice

Political Challenges

Science and Technology

Scoring Rubric

Stay Connected

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.

AP® and SAT® are trademarks registered by the College Board, which is not affiliated with, and does not endorse this website.

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, the ultimate guide to the ap spanish literature exam.

Advanced Placement (AP)

The AP Spanish Literature and Culture exam is an excellent opportunity to show off your critical reading, writing, and analytical skills in another language while earning college credit in the process.

But conquering the course material is only the beginning. You need to learn everything there is to know about the exam to boost your chances of earning a passing score (and college credit) to boot!

In this guide, we’ll go over everything you need to know to start prepping for the AP Spanish Literature and Culture exam , including:

- The structure and format of the AP Spanish Lit exam

- The core themes and skills you’ll be tested on

- The types of questions that appear on the exam and how to answer them (with real AP student sample responses!)

- How the AP Spanish Lit exam is scored, with official scoring rubrics

- Four crucial tips for prepping for the AP Spanish Lit exam

There’s a lot to cover, so let’s get started!

Exam Overview: How Is the AP Spanish Lit Exam Structured?

The AP Spanish Literature and Culture exam tests your understanding of Spanish language skills and literature written in Spanish , including short stories, novels, essays, plays, and poetry.

Like most AP exams, the test lasts for a total of three hours . You’ll have to answer 65 multiple choice questions and four free-response questions to complete the test.

The AP Spanish Lit exam is divided into two sections. Section I of the exam consists of 65 multiple-choice questions and lasts for one hour and 20 minutes (80 minutes total). The multiple-choice section is further divided into two parts: Part 1A, and Part 1B. Both Part A and Part B of Section I are totally multiple choice, but they test you on different skills. As a whole, Section I counts for 50% of your total exam score .

Section II of the exam tests your critical reading and analytical writing skills through four free response questions . Section II lasts for 1 hour and 40 minutes (100 minutes) and counts for 50% of your total exam score . Each free response question asks you to write either a short answer or longer essay in response to a specific text or set of texts (called “stimulus” on the exam).

To help you visualize the breakdown, here’s the AP Spanish Lit exam structure in table format:

Source: The College Board

But is AP Spanish Literature hard? If you want to get an idea of how difficult the exam is and learn how to get a 5 on AP Spanish Literature, keep reading: we’ll break down the course content, skills, and themes (temas de AP Spanish Literature) that you need to understand for the AP Spanish Lit exam next!

Course Themes, Skills, and Units

AP Spanish Lit is focused around six core themes , or temas de AP Spanish Literature. These course themes are designed to help you develop the skills you need to fully understand Spanish literature and culture…and ace the AP Spanish Lit exam!

Exploring these themes and applying them to the texts on the AP Spanish Literature reading list will equip you with the critical thinking and analytical skills you need to succeed on the AP Spanish Literature exam. The six themes and skills that you’ll master during the course are:

The AP Spanish Lit themes and skills are typically taught through eight units of study . Understanding these units of study will help you get a big picture view of what the course covers, and how different course topics are connected. Content from each course unit will appear on the exam, so it’s important to familiarize yourself with them as early as you can!

The eight units of study in AP Spanish Literature are :

Now that you have a good sense of what’s on the AP Spanish Literature exam, let’s take a closer look at each section of the exam and the types of questions that appear in each one.

Spanish AP Literature Exam Section I: Multiple-Choice

The first section of the exam tests you in two main areas: your interpretive listening skills, and your reading analysis skills .

To test you on these skills, Section I is broken down into two parts: Part A and Part B. Part A will test your interpretive listening skills, and Part B will test your reading analysis skills. Both parts of Section I use authentic Spanish language texts presented in different formats to assess your skills.

While Parts A and B of Section I test you using texts in different formats (audio vs. print/written), both parts include question types that assess you on these three skills:

- At least 75% of multiple-choice questions assess your ability to analyze and interpret literary and audio texts in Spanish.

- Around 10% of multiple-choice questions assess your ability to make connections between a literary text and a non-literary text or an aspect of Spanish culture.

- Around 10% of the multiple-choice questions assess your ability to compare literary texts in Spanish.

Since Part A and Part B are a bit different (though both are multiple-choice!), let’s break them down a bit further next.

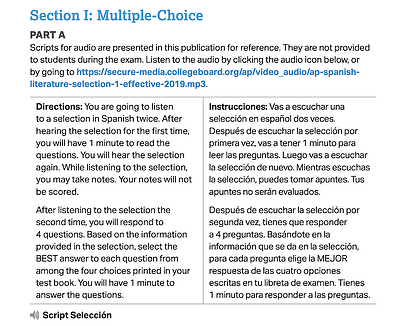

Section I Part A: Multiple-Choice Interpretive Listening

Part A of Section I asks you to demonstrate your ability to accurately interpret a variety of Spanish language audio texts . This part of Section I consists of 15 total questions that are presented in sets of either four or seven multiple-choice questions. Each set of questions comes with an audio text in either the format of an interview, a poem, and a discussion or lecture on literary topics.

Here’s a clearer breakdown of the structure of Part A of Section I:

Since Part A is a bit of an outlier when it comes to the testing format, it’s important to understand how this part of the exam will be administered ahead of time. Let’s look at a real interpretive listening question to get a better sense of how this part of the exam works next.

Sample Multiple-Choice Question: Interpretive Listening

To help you get a better sense of what Section I Part A will be like, let’s take a look at a real interpretive listening question from the 2021 AP Spanish Lit exam .

In the picture below, you’ll see a set of written directions (which appear in Spanish on the real exam!), a written transcript of a poem entitled “La guitarra,” and one multiple choice question. However, on the real exam, you’ll only get to listen to the text provided –you won’t be given a printed copy of it!

When this portion of the exam begins, you’ll listen to the provided text once, then have one minute to take notes and view the exam questions for this portion of the test. After that, you’ll listen to the provided text a second time, then have one minute to answer the provided set of questions (ranging from four to seven questions in total). You’ll be able to use the notes you took for reference as you answer the questions!

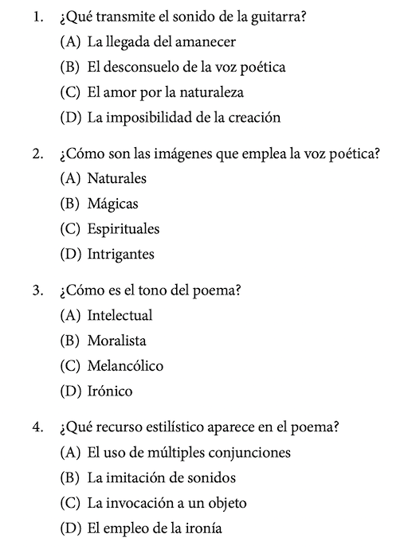

You can read the directions, Spanish language poem, and set of four questions for our example interpretive listening task here:

And here's the question set:

The four questions in the set above ask about the events that occur in the poem, as well as the poem’s imagery, tone, and writing style . We’ll break down the correct answers for each question here:

To ace interpretive listening questions like these, you’ll need to listen closely, jot down notes about important words, themes, or ideas, and use context clues to accurately analyze the texts that you’re given.

Next, let’s look at the second part of Section I of the exam: Part B, multiple-choice reading analysis.

Section I Part B: Multiple-Choice Reading Analysis

Section I Part B asks you to demonstrate your skills of reading analysis by engaging with print or written texts. On this part of Section I, you’ll be given 60 minutes to complete 50 multiple-choice questions. Part B accounts for 40% of your exam score .

The questions on Part B are divided into four sets. Each set applies to a specific text or set of texts. To give you a clearer picture of how Part B is structured, we’ll break it down further below:

Sample Multiple-Choice Question: Reading Analysis

To help you get a better sense of what Section I Part B will be like, let’s take a look at a real set of reading analysis questions from the 2021 AP Spanish Lit exam .

In the picture below, you’ll see a set of written directions (Spanish-only provided on the real exam!), a written passage, and a set of five multiple-choice questions :

Each of the questions above asks you to analyze the provided text and select the answer choice that best characterizes your understanding of the text’s meaning . Now, let’s look at the correct answers for each question and the skills you’ll need to successfully choose them:

To succeed on reading analysis questions like the ones above, you’ll need to have a solid grasp of Spanish language conventions, strong analytical skills, and the ability to interpret ideas in different contexts.

Next, let’s look more closely at Section II of the AP Spanish Lit exam: the free-response section.

Or more accurately, escribe algo.

Spanish AP Literature Section II: Free-Response

Section II of the AP Spanish Lit exam lasts for one hour and 40 minutes, includes four free-response questions, and counts for 50% of your exam score.

There are two distinct types of questions on the AP Spanish Lit free-response section : short answer questions, and essay questions. Both types of free-response questions test your ability to clearly and thoughtfully explain the events of a text, analyze texts, and compare and contrast multiple texts that share common themes. You’ll demonstrate these skills by writing short and longer free-responses on the exam!

To help you understand what free-response questions will be like on the exam, we’ll walk you through a real exam question, scoring rubric, and student response for both short-answer and essay questions below.

Free-Response Short Answer Question: Scoring Rubric and Example Response

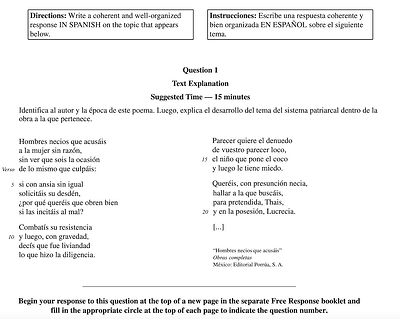

On the AP Spanish Lit exam, you’ll respond to two short-answer questions . The sample question below is an example of a short answer free-response question from the 2021 AP Spanish Lit exam. This short-answer question asks students to provide a Spanish-language explanation of the provided text, which comes from Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz’s poem “ Hombres necios que acusáis ,” written in 1689:

The free-response short answer question above asks students to read the provided text, identify the author and period of the text, and explain the development of a given theme in the text.

We’ll provide a sample student response to this question in just a minute, but first, let’s see how you could earn full credit for this question. Take a look at the official scoring rubric used to evaluate this question on the 2021 Spanish AP Lit exam to see how your response will be scored:

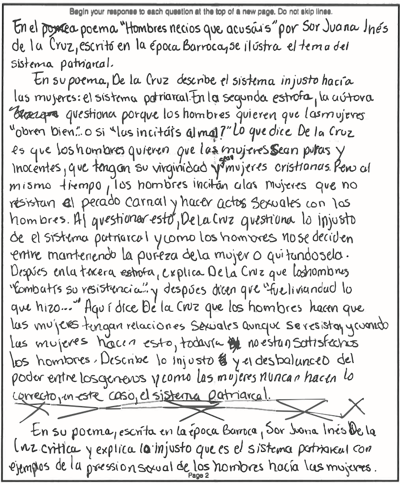

The example student response below comes straight from the 2021 AP Spanish Lit exam. The student is responding to the short-answer question we’ve included above.

This short-answer response received a 3 for Content and a 3 for Language based on the criteria in the scoring rubric above. That means that this student response received six out of six possible points for this free-response question!

Free-Response Essay Question: Scoring Rubric and Example Response

There are two free-response essay questions on the AP Spanish Lit exam . To help you get an idea of what these questions are like, let’s go over a sample essay question, scoring rubric, and student response from the 2021 AP Spanish Lit exam.

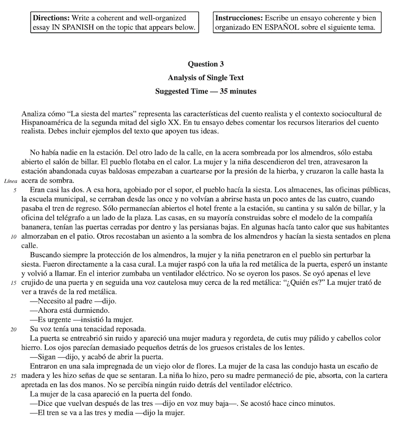

The free-response essay question below asks students to analyze how a single text represents both the specified period, movement, literary genre, and technique and the given cultural context. The selected text in the question below comes from Gabriel García Márquez’s short story, “ La siesta del martes” :

Before we look at a real student’s response to this essay question, let’s look at the scoring rubric used to evaluate responses to this essay question . The rubric below was used to score this type of essay question on the 2021 AP Spanish Lit exam:

Now that you know how this type of essay question is scored, let’s look at a real student’s response to this essay question. This student’s response comes straight from the 2021 AP Spanish Lit exam and scored a 5/5 for Content and a 5/5 for Language, which means this response received full points !

How the AP Spanish Literature Exam Is Scored

Understanding how your AP Spanish Lit exam will be scored can help you feel more prepared for the exam. Here, we’ll overview how each section of the AP Spanish lit exam is scored, scaled, and combined to produce your final score on the AP 1-5 scale .

As a refresher, here’s how the score percentages break down on the AP Spanish Literature exam:

- Section I: Multiple-choice: 50% of overall score

- Section IA: 10% of score

- Section IB: 40% of score

- Section II: Free-response: 50% of overall score

- Question 1: 7.5%

- Question 2: 7.5%

- Question 3: 17.5%

- Question 4: 17.5%

On the multiple choice section, you earn one raw point for every question you answer correctly. This means that the maximum raw score you can earn on the multiple choice section is 65 points. No points are deducted for wrong answers .

The free-response section is a bit different. The two short answer free-response questions are each worth six raw points, and the two essay free-response questions are worth 10 points each. This means that there are a total of 32 possible points in the free-response section.

Keep in mind that you’ll lose points on free-response questions only for major errors , like failing to analyze or compare the provided texts, for instance. You aren’t going to lose points for a stray comma splice here and there as long as grammatical errors don’t interfere with the AP grader’s ability to understand your response.

You can earn 97 raw points on the AP Spanish Lit exam. Here’s how those are divided by section:

- 65 points for multiple-choice

- 32 points for free-response

From there, your raw scores will be converted into a scaled score of 1-5 by the College Board. That’s the score you’ll see when you receive your official score report! Unfortunately, the 5 rate for the AP Spanish Literature exam is pretty low compared to other AP exams . You can see what percentage of test takers earned each possible score on the 2021 AP Spanish Lit exam below:

4 Tips for Prepping for the AP Spanish Literature and Culture Exam

You know what’s on the exam and how it’s scored. Now you’re ready to get down to business! If you’re wondering how to study for AP Spanish Literature, keep reading–we’ll give you four top tips for kickstarting your Spanish AP Literature prep below!

Tip 1: Take a Practice Exam

The best way to assess your preparedness for the AP Spanish Lit exam is to test your skills out on a practice exam. Taking a practice exam will help you identify skills and texts that you struggle with. From there, you can design a study plan that targets your weaker areas to improve your chances of earning a passing score !

You can find a full set of official multiple-choice practice questions here , and the College Board provides a large repository of past free-response exam questions on their website . Be sure to use official practice questions like the ones linked here as much as possible. Using official practice materials ensures you’re getting quality practice that’s very similar to the real exam!

Tip 2: Consult AP Spanish Literature Reading Lists

The AP Spanish Literature course includes a total of 38 required texts –and you’ll be expected to read and know all of them for the exam. That’s a lot of texts to master, especially if Spanish isn’t your first language!

Your AP teacher will dedicate lots of class time to teaching you the texts on the AP Spanish Literature reading list, but if you want to really learn them, you’ll need to spend time studying them outside of class too. Remember: all of the required course readings will be unabridged, full-text, and in Spanish. The more effort you dedicate to studying the texts on the AP Spanish Literature reading list on your own time, the more successful you’re likely to be on the AP exam.

The College Board provides an official AP Spanish Literature reading list on their website . You can use this list to start working through the course readings and searching for supplemental study materials for individual texts online.

Tip 3: Master the Temas de AP Spanish Literature

Understanding the six core themes of the AP Spanish Lit course (temas de AP Spanish Literature) is crucial to success on the AP exam. These course themes are designed to promote critical thinking about the course readings and encourage making connections and comparisons between different texts and cultures.

As you take the AP Spanish Literature course, you’ll notice that the course themes are paired with various learning goals. Pay close attention when these themes pop up in course materials and consider what you should be learning from them! Doing this will help you develop the skills you need to interpret, analyze, and compare texts on the exam .

Tip 4: Practice Tough Questions

As you progress through the AP Spanish Lit course, you’ll begin to notice question types that seem to trip you up. As you get graded quizzes and tests back during class, keep running notes about the questions you miss. Jot down what type of question it was (multiple choice or free response), the skills it assessed, and where you lost points or went wrong.

From there, you can find and work with practice questions (like the ones linked earlier!) that are the same type as the ones you’ve struggled with. The more you practice with questions that trip you up, the more likely you’ll be to get them right on the real exam!

What’s Next?

Need a little help with your Spanish vocabulary? This list of how to talk about body parts in Spanish can give you a fun way to brush up!

Thinking about taking another foreign language in high school? This guide will help you pick the best languages for you.

While the SAT Spanish subject test is no longer offered, you can use the free study materials to help you practice your reading and comprehension skills. We’ve compiled a list of resources that you can use as extra prep.

Looking for help studying for your AP exam?

Our one-on-one online AP tutoring services can help you prepare for your AP exams. Get matched with a top tutor who got a high score on the exam you're studying for!

Ashley Sufflé Robinson has a Ph.D. in 19th Century English Literature. As a content writer for PrepScholar, Ashley is passionate about giving college-bound students the in-depth information they need to get into the school of their dreams.

Student and Parent Forum

Our new student and parent forum, at ExpertHub.PrepScholar.com , allow you to interact with your peers and the PrepScholar staff. See how other students and parents are navigating high school, college, and the college admissions process. Ask questions; get answers.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Mexican Spanish

Ap Spanish Essay Examples

Are you struggling to find examples of AP Spanish essays? Look no further!

In this article, we’ll explore various essay samples that will help you ace your AP Spanish exam.

From cultural comparison essays to persuasive and literary analysis essays, we’ve got you covered.

Whether you’re looking for inspiration or guidance, our expertly crafted examples will provide you with a solid foundation.

So, sit back, relax, and let us take you on a journey through the world of AP Spanish essay writing.

Key Takeaways

- Analysis of causes and effects of immigration

- Examination of cultural assimilation and its positive and negative effects

- Importance of understanding immigration’s impact on individuals and communities

- Significance of comparing cultures to gain a deeper understanding

Sample AP Spanish Essay on Immigration

You should start your essay on immigration with an analysis of the causes and effects of this complex issue.

Immigration challenges and cultural assimilation are two key aspects of this topic that need to be explored. Immigration challenges refer to the difficulties faced by individuals and families as they navigate the process of moving to a new country. These challenges can include language barriers, discrimination, and the struggle to find employment and housing.