An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites. .

Disaster Case Management

Disaster Case Management (DCM) is a time-limited collaboration between a trained case manager and a disaster survivor involving the development of a disaster recovery plan and a mutual effort to meet those disaster-caused unmet needs described in the plan. Disaster Case Management is most often funded by FEMA as a federal award or cooperative agreement to the SLTT.

To assess and address a survivor’s unmet needs through a disaster recovery plan. This disaster recovery plan includes resources, decision-making priorities, providing guidance, and tools to assist disaster survivors.

Please directly consult the provider of a potential resource for current program information and to verify the applicability and requirements of a particular program.

Content Search

World + 7 more

Case Studies: Red Cross Red Crescent Disaster Risk Reduction in Action – What Works at Local Level, June 2018

Attachments.

Community/local action for resilience:

- Building the disaster resilience of asylum seekers

The Australian Red Cross in Queensland adapted a generic preparedness tool to support highrisk marginalised communities of asylum seekers to build their own resilience to disaster. Specific and relevant messaging was developed within a community education programme co-designed with members of the asylum seekers community, who became educators and facilitators to deliver the programme. The programme reached 900 people in a successful pilot, measured through positive shifts in knowledge of key actions to take in preparedness of disaster. The underlying achievement is the acceptance and trust of the communities, reflecting the respect for cultural and language diversity, and recognizing the capacity of asylum seekers communities to contribute and participate in their host country.

- Integrated Coastal Community Resilience and Disaster Risk Reduction in Demak, Central Java

Exacerbated erosion affected the ecology and increased vulnerability of coastal communities in Demak. The Indonesian Red Cross mobilized communities through Community-Based Action Teams to restore the ecosystem through mangrove plantation and implement livelihood generation to improve community resilience. Under an integrated approach, the community is connected with village authorities and scientists from the Bogor Agricultural Institute to implement sustainable local action. The programme has shown concrete results in reducing the risks of tidal disasters, while eco-tourism and crab cultivation farming have increased the income of the communities, along with their heightened awareness and preparedness for disaster.

- Winter shelters for rural herder communities

Rural herders in Mongolia must keep their livestock alive through extreme temperatures and exposure of harsh winters that follow after drought. In efforts to reduce livestock loss, the Red Cross supported herder communities to design and construct winters shelters for livestock in a participatory approach garnering the collective capacity of community, local government and the Red Cross. A strong community focus ensures that the herders drive the activities towards preserving their livelihoods and the traditional nomadic way of life under threat by climatic challenges.

- Youth-led actions for more resilient schools and communities: Mapping of School Safety approaches and Youth in School Safety training for youth facilitators

Over the last two years the Red Cross Red Crescent Southeast Asia Youth Network has improved Youth programming and networks on youth-led initiatives and solutions for DRR. A pilot Youth in School Safety Programme rolled out in six countries, training 150 youth volunteers who in turn conducted countless school safety actions. A comprehensive mapping of school safety actions in all 11 countries of South Asia is underway to showcase activities of RCRC Youth volunteers on the ground.

Private Sector Interventions:

- Australian Business Roundtable for Disaster Resilience and Safer Communities

Leaders of leading commercial organizations jointly commit resources to work constructively with government to make Australian communities safer and more resilient to natural disasters, by shifting national investment from recovery and response to preparedness and mitigation. The Australian Red Cross joins this Roundtable - contributing on emergency management and humanitarian aspects - to collectively deliver on community education, risk information, adaptation research, mitigation infrastructure and strategic alliances.

Disaster Risk Governance:

- A seat at the table: inclusive decision-making to strengthen local resilience

Disaster related laws and policies need to better include and protect those most at risk of disasters. This case study outlines the steps taken by the IFRC Disaster Law Programme - from global research undertaken jointly by IFRC and UNDP, to the provision of technical advice in supporting Asia Pacific National Societies, as the community-based actor and auxiliary to government, to ensure inclusive community empowerment and protection, gender and inclusion in national disaster laws and policies.

Gender and Inclusiveness:

- Participatory Campaign Planning for Inclusive DRR Knowledge and Messaging in Nepal

An innovative approach that embraces the essence of inclusiveness, the Participatory Campaign Planning methodology is applied to develop hazard messages and the means of communicating them that are tailored to different target groups, with the aim of making them more effective in creating behaviour change. This case study focuses on urban communities in Nepal and various elements to be considered within different target groups and their geographic environments.

- Community participatory action research on sexual and genderbased violence prevention and response during disasters

This collaborative research by the IFRC and the ASEAN Committee for Disaster Management was undertaken in recognizing that there are few SGBV studies that focus on low-income developing countries and fewer that go beyond the gendered effects on women and girls, overlooking men and boys and sexual minority groups. Key findings illustrate that the risks to SGBV are exacerbated during natural disaster situations in Indonesia, Lao PDR and the Philippines, and that “disaster responders” and actors addressing needs of SGBV survivors are not working together adequately to reduce these risks.

Early Warning and Early Action:

- Forecast-based Financing: Effective early actions to reduce flood impacts

When four pilot communities in the district of Bogura were affected by severe flood events in July and August of 2017, the Early Action Protocol of the Forecast-based Financing (FbF) approach was activated, and unconditional cash grant was chosen as the early action for floods to give people the flexibility to prepare individually for the impending flood and take the measures they see fit. This case study outlines the steps taken by Bangladesh Red Crescent Society and German Red Cross to implement FbF in Bangladesh. It analyses not only the effectiveness of the activation in Bogura, but the longer term impacts of this early action development.

- CPP Early Warning: Saving Thousands in Cyclone Mora

Through the Bangladesh Cyclone Preparedness Programme (CPP) interventions, a programme jointly run by the Government of Bangladesh and the Bangladesh Red Crescent Society (BDRCS), the communities of the coastal areas in Bangladesh have become more aware of the need to go to safe shelters during emergencies, have understood the significance of early warning and learned to pay heed to advice from CPP and youth volunteers. On 28 May 2017 - the eve of Cyclone Mora, more than 55,260 CPP volunteers and BDRCS youth volunteers were deployed to pass early warning message door to door in the coastal region, and announcing the danger of the approaching cyclone in the local language. Cyclone early warning messages were disseminated across a population area covering 11 million people, and almost half a million people were reached in this process and taken to safe places in less than 24 hours. The CPP has substantially reduce death tolls due to cyclones in Bangladesh.

- Flood Early Warning and Early Action System (FEWEAS)

The Flood Early Warning Early Action System (FEWEAS) was developed through a collaboration between the Indonesian Red Cross (PMI) and Institute Teknologi Bandung (ITB) to provide effective solutions for reducing disaster risk through a shared platform for community and government to address issues upstream and downstream in formulating appropriate strategy, planning and ground action for floods. FEWEAS is an internet-based application to predict and monitor rainfall and flooding. PMI Provincial and District staff and volunteers are using the FEWEAS to monitor floods along the Bengawan Solo River in East Java, and along the Citarum River in West Java. While the application provides flood alerts and updates to the community through smartphones, the communities and Community Based Action Teams can update their response, upload photos, videos and relevant information to further inform response actions.

- Forecast-based Financing for the vulnerable herders in Mongolia

The Mongolian Red Cross Society (MRCS) assisted 2,000 herder households in most-at-risk areas (40 soums in 12 provinces) with unrestricted cash grants in December 2017 and with animal care kits in January 2018, before the peak of the winter season. The MRCS used the Dzud Risk Map released by the Government in November 2017 to decide which soums to target for early action with the aim to reach the herders well before the loss of their livestock to reduce the impact of Dzud on the livelihoods of the herders. The Dzud Risk Map highlighted the risk of livestock death throughout the whole of Mongolia. A cost-benefit analysis is being conducted to further inform FbF in Mongolia.

- More than response: Building partnerships to engage communities in preparedness and early warning systems in the Pacific

A community early warning system (CEWS) model was developed in partnership by the Red Cross, government agencies and regional organizations in the Pacific to better link CEWS with national and sub-national systems. Taking these pilots to scale requires i) national mechanisms such as SOPs and action plans that systematically link warnings and climate information provided by National Meteorological Services to early preparedness actions at multiple scales, and; ii) available funding (at multiple scales) to support early actions. Recently a Roadmap for Forecast-based Financing for Drought Preparedness has been developed in the Solomon Islands. Through continued partnership approach, the Roadmap and outcomes from the regional ‘FINPAC’ CEWS project will be used to support the Government of the Solomon Islands and Solomon Islands Red Cross to implement a programme for communities, provincial and national authorities to apply forecast information for early action at scale. The drought thresholds developed in collaboration will form the basis of an FbF trigger system in the Solomon Islands.

Displacement and DRR:

- Preparing and reducing risks of disasters to displaced communities

Cox’s Bazar became the world’s most densely populated refugee settlement following the massive influx of people from Myanmar that started in August 2017. Being a coastal district prone to disaster, existing infrastructure and services cannot cope to cover the host population and incoming refugees, and preparedness interventions became critical. This case study follows actions taken to extend the coverage of the Cyclone Preparedness Programme, successfully integrating displaced people in camp settlements as temporary CPP camp volunteers, to support in establishing early warning system and ensure relevant preparedness and response action.

Urban Community/local action for resilience:

- What is an Urban ‘Community’? – New ways for local DRR actions in cities . Lessons learned from the 2015 Nepal earthquake response show that vulnerable populations in urban context do not often engage with or rely on local disaster management committees in the event of a disaster. Instead they organize themselves around their own networks, both informal and formal, such as family, temples, markets, service-providers, employment. A meaningful DRR intervention in urban communities must first recognize what defines an urban community and how they are organized to guide specific engagement and participatory-led approaches. The target group and network-based approach by Nepal Red Cross are innovations in organizing effective community-owned urban disaster resilience.

Green Response/ Enhancing Preparedness for Effective Response:

- Greening the IFRC Supply Chains; mapping of our GHG emissions

Under the Green Response initiative to improve environmental outcomes of life-saving operations, the IFRC in reviewing practices and policies is mapping the present level of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions generated by relief operations and to implement GHG reduction activities to lower the environmental impact of emergency operations. The mapping contributes to the global emission baseline for IFRC supply chain monitoring, to design the reduction roadmap and build internal capacity.

- Environmental Field Advisor deployment in an emergency response

To improve the environmental outcomes and reduce negative impacts of operations and programmes, the IFRC deployed an Environmental Field Advisor (EFA) to the Population Movement Operation in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. The EFA conducted an environmental impact assessment and worked with project leads to identify and implement improvements. A significant achievement to date is the IFRC joining the UNHCR/IOM/WFP/FAO to provide LPG as cooking fuel to camp community households to combat massive deforestation cause by firewood collection.

Related Content

World + 8 more

Fewer Tropical Cyclones observed than forecast over November 2023 to April 2024 in the southwest Pacific

Undac operational partners, covid-19 lessons learnt: launch of the first pan-european network for disease control, les principales agences sanitaires présentent une terminologie actualisée pour les agents pathogènes qui se transmettent par voie aérienne.

Advertisement

Covid-19 Disaster relief projects management: an exploratory study of critical success factors

- Published: 26 April 2022

- Volume 17 , pages 1–12, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

- Arvind Upadhyay ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6906-5369 1 ,

- Maria Jose Perezalonso Hernandez 2 &

- Krishna Chandra Balodi 3

3041 Accesses

4 Citations

Explore all metrics

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused unprecedented socio-economic devastation. With widespread displacement of population/ migrants, considerable destruction of property, increase in mortality, morbidity, and poverty, infectious disease outbreaks and epidemics have become global threats requiring a collective response. Project Management is, however, a relatively less explored discipline in the Third Sector, particularly in the domain of humanitarian assistance or exploratory projects. Via a systematic literature review and experts' interviews, this paper explores the essence of humanitarian projects in terms of the challenges encountered and the factors that facilitate or hinder project success during crises like Covid-19. Additionally, the general application of project management in international assistance projects is analysed to determine how project management can contribute to keeping the project orientation humane during a crisis. The analysis reveals that applying project management tools and techniques are beneficial to achieve success in humanitarian assistance projects. However, capturing, codifying, and disseminating the knowledge generated in the process and placing the end-users at the centre of the project life cycle is a prerequisite. While the latter can seem obvious, the findings demonstrate that the inadequate inclusion of beneficiaries is one of the main reasons that prevent positive project outcomes leading to unsustainable outcomes. The key finding of this paper is that the lack of human-centred approaches in project management for humanitarian assistance and development projects is the main reason such projects fail to achieve desired outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

An Inquiry into Success Factors for Post-disaster Housing Reconstruction Projects: A Case of Kerala, South India

Shyni Anilkumar & Haimanti Banerji

Linking Ambitions, Transparency and Institutional Voids to South–South Funded CPEC Project Performance

Governance Practices in Poverty Alleviation Projects: Case Study from Stewardship-Driven Perspective and Sustainability Context

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The destructive capacity of natural and artificial disasters increases continuously, affecting millions of people globally. In 2016, 564.4 million people were reportedly affected by natural disasters, the highest since 2006 (Guha-Sapir et al. 2016 ). The World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 as a pandemic on March 11, 2020, having around 3 million cases and causing 207,973 deaths (WHO, COVID-19: Situation Report). A Brooking’s report Footnote 1 on socio-economic impact of COVID-19 notes that causing global economy to contract by 3.5 percent it brought about one of the deepest recessions of modern times. According to an ILO report Footnote 2 , COVID-19 led to a loss of 8.8 per cent of global working hours roughly amounting to 255 million full-time jobs in 2020 compared to last quarter to 2019. As of June 2021, the COVID-19 outbreak had spread to 215 countries and territories across six continents causing over 3.9 million deaths. Footnote 3 Given the vulnerability of nations to hazards like Covid-19, International Aid (IA), also known as International Development (ID), has become increasingly important especially for less developed countries. The United Nations (UN) has suggested that the developed economies spend at least 0.7% of their gross national income on international assistance (Myers 2015 ). Much of this assistance ends up financing projects managed by the Third sector, including international, national and local non-governmental organisations (NGOs), charities and other voluntary groups (Marlow 2016 ).

NGOs are private organisations characterised by humanitarian objectives "that pursue activities to relieve suffering, promote the interest of the poor, protect the environment, provide essential social services, or undertake community development" (World Bank 1995 ). These organisations are key contributors to international assistance (Morton 2013 ), which is broadly divided into two categories: Official Development Assistance (ODA) and Humanitarian Assistance (HA), also referred to as emergency aid. HA projects have the overall goal of providing an immediate response as fast and effectively as possible. Nevertheless, the time scale and particular goals are less specific because of the spontaneous nature of these events and the available information (Lindell and Prater 2002 ). In this sense, HA projects fall into the category of exploratory projects, for which 'neither the goals nor the means to attaining them are clearly defined' (Lenfle et al. 2019 ). The loose definition of deliverables, the scope, and the recovery scale makes these projects challenging (Walker 2011 ). Additionally, a lack of Project Management (PM), cultural sensitivity, and stakeholder involvement contribute to high failure rates and unsatisfactory performance for these projects (Golini et al. 2015 ).

For exploratory projects, neither the output nor the means to attain it can be established from the beginning. Given their increasingly significant impact, however, it is prudent to develop a scientific understanding of the projects management challenges and success factors for the exploratory projects. Therefore, this research aims to investigate via template analysis of the relevant qualitative data, the ontology of humanitarian aid projects, and the effect that project management implementation could have on their success for such projects. More specifically, we review the literature and case studies on humanitarian projects by NGOs to identify the main challenges in achieving favourable HA project outcomes and factors that promote project success or contribute to project failure. We also explore the PM procedures, tools, and frameworks used for International Development and how these influence the cognitive Footnote 4 aspects of humanitarian projects; and revisit the link between PM and human-centred design in the Third Sector. We find that applying project management tools and techniques are beneficial to achieve success in humanitarian assistance projects. However, knowledge generation, storage, and sharing and end-user-centric projects' design and execution throughout the project life cycle are major critical success factors. The findings also highlight that the inadequate consideration of beneficiaries’ identity, expectation, and role is one of the main reasons preventing positive project outcomes from leading to sustainable outcomes. Our findings contribute to the literature in three ways. First, it explores the extension of the application of PM tools and techniques to a much important phenomenon of humanitarian assistance projects, especially during the current Covid-19 crisis. Second, relying on PM and design thinking literature, we explore more pragmatic design and execution choices that bring project output/ deliverables and outcomes closer. Thirdly, through literature review, case studies, and expert interviews, our study highlights some critical success and failure factors in humanitarian assistance projects.s The rest of the paper is organised as follows. Part two presents the literature review, followed by the methodology and findings, followed by the conclusion.

2 Literature review

2.1 crisis and humanitarian aid project management.

Relief projects carry an "acute sense of urgency", and their results are critical to people's livelihood in the affected communities (Steinfort and Walker 2011 ). The challenge is to minimise human suffering and death (Noham and Tzur 2014 ) and do so in an often hostile and uncertain environment, where violence, socio-political instability, disease, other health hazards, panic, and chaos are encountered. Other obstacles include lack-of or poor communication and transportation infrastructures, different cultural norms and rules, complex issues of autonomy and control and managing productive cooperation with governments and other organisations (Steinfort and Walker 2011 ).

According to Bysouth, project management is a relatively new discipline in the Third Sector. Despite the limited information regarding the adoption of PM methodologies by NGOs (Golini et al. 2015 ), several authors agree that PM expertise can be employed as a possible remedy for the poor performance of ID projects (Landoni and Corti 2011 ; Golini and Landoni 2014 ). Moreover, guidelines such as PMDPro and PM4DEV have been developed explicitly for NGO management of these projects (Table 1 ). However, recent empirical studies note widespread adoption of few PM tools, viz., Logical Framework (LogFrame) and Progress Reports and almost none of few such as Earned Value Management System and Issue Logs (Golini et al. 2015 ). LogFrame provides the goals, measures and expected resources for each level of the means-to-end logical path, laying out the way between vision, overall and specific objectives, desired outputs and outcomes through its detailed breakdown of the chain of causality among activities. Moreover, Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E) supports learning, governance and performance accountability (Steinfort and Walker 2011 ). It also includes the evaluation criteria- relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, impact and sustainability- to ensure appropriate monitoring and control.

Research has shown that lack of expertise and planning (Alexander 2002 ), poor coordination, duplication of services, and inefficient use of resources (Kopinak 2013 ), inadequate beneficiary involvement has hindered positive outcomes (Brown and Winter 2010 ). Coupled with Linking Relief, Rehabilitation and Development (LRRD) omission, this has often provided unsustainable solutions (Kopinak 2013 ). These interspersed layers demonstrate that humanitarian management cannot be improvised and that planning is relevant at all stages of the Disaster Cycle (Alexander 2002 ; Steinfort and Walker 2011 ). The professionalisation of humanitarian response is thus inevitable due to the adding layers of complexity that resulted from growing levels of stakeholders and poor management skills.

2.2 Defining project success

Project management focuses on delivering change via unique sets of concerted actions (Tantor 2010 ). Unlike general management, where almost everything is routine, almost everything is an exception (Meredith et al. 2014 ). Each project is unique and temporary, with a definite start and end (Tayntor 2010 ). The end of a project can be defined when the desired output is delivered or when the output can no longer be delivered, or when there is no more need for the project. These endeavours aim to create a unique product or deliver a unique service or result. It is possible to have repetitive elements, but repetition does not take away the uniqueness of a project because the mix of elements is unique to each project. Therefore, projects can also be considered generators of value (Winter et al. 2006 ) and explicit and tacit learning, as their uniqueness provides a foundation for capturing new knowledge (Zollo and Winter 2002 ).

The definition of project success is ambiguous due to the different characteristics, perspectives, interest, and objectives of the stakeholders involved (Fig 2 ). Nonetheless, the essential requirement of project success is achieving the project objectives/outputs within a defined budget, quality, and time. Project output can be defined as the product, service or result that the project was expected to generate. Furthermore, many authors suggest that project success is multidimensional, and that project outcome should also be considered when determining success (Rodrigues et al. 2014 ). That is particularly relevant in the case of exploratory post-crisis projects, for which neither the output nor the means to attain it can be established from the beginning (Lenfle 2014 ). This multidimensional outlook reflects project success and the project ' manager's responsibilities, including managing time, cost, quality and human resource, integration, communication, project design, procurement, and risk management (Radujkovic and Sjekavica 2017 ). The uniqueness of each project also requires the project manager to be creative, flexible, and highly adaptable. Special skills such as conflict resolution and negotiation are also required due to the high level of discontent present in these projects.

Project management success does not guarantee that the project output will lead to a successful outcome (Steinfort and Walker 2011 ; Kopinak 2013 ). The project outcome is the change produced as a consequence of the delivery of such output. Unfortunately, in HA projects, outputs are often delivered accordingly but still fail to provide a successful outcome. Project success might be initially perceived as achieved in such cases, yet project outcome might demonstrate the opposite (Brown and Winter 2010 ). This occurs when hard Footnote 5 and soft Footnote 6 services fail to transform the output into a functioning outcome (Steinfort and Walker 2011 ); perhaps because the output lacked the infrastructure to support its use or because it failed to consider the 'beneficiaries' needs, culture, behaviour, the context of their lives (Brown and Winter 2010 ). The latter has been recognised as a consequence of the ambiguous definition of target customer or beneficiary in HA projects, leading to their exclusion in the project design phases and considerable project execution errors (Golini et al. 2015 ). To this end, the literature suggests referring to the end-user as a consumer over the word beneficiary". Although both terms may be used interchangeably, researchers suggest that the latter can infer that recipient who do not pay for the services shall have unquestionable gratitude and, therefore, no right to choose or be informed, leading to poor recipient involvement projects. Steinfort and Walker ( 2011 ) argue that project success can be linked with the degree of customer value generated from the project. The real value is the output combinations that lead to a specific outcome, which allows the stakeholders to perceive that the project deliverables have been achieved. However, the natural outcome of the project is to generate customer value. The diversity of stakeholders and the different perception of values (Rodrigues et al. 2014 ) and a lack-of or poor inclusion of beneficiaries in project design (Golini et al. 2015 ) further hinder consensus in defining HA projects success.

2.3 Critical success factors

Planning is considered desirable in achieving success, especially among HA projects during Crisis like Covid-19 (Taylor 2010 ). Plans must be robust and granular yet flexible enough to adapt to different circumstances. NGOs and other organisations such as civil protection agencies have set up measures of natural disaster response based on their magnitude, recurrence, physical and human consequences, and the duration of their impact. Additionally, technology has become a vital tool in managing disasters (Alexander 2002 ). It was evident during the Covid-19 crisis as to how the biotechnology, data storage and analytical technology, and communication technology allowed the primary responders, frontline workers, and researchers to work together to arrive at standard operating procedures and share them with relevant stakeholders across the globe in a relatively short time. International recognition and acceptance of a set of common principles are essential to stimulate humanitarian aid project design, innovation, accountability and effectiveness, and the implementation of best tools and approaches.

Despite the diversity in stakeholders, antecedents and consequences, and desired outcomes (Alexander 2002 ), the lessons and results captured from previous projects can serve as a blueprint for planning and implementation (Lampel et al. 2009 ). Explicit knowledge can be expressed and formalised into frameworks or formal " know-how" procedures and instructions, which can later be integrated into the organisation/field/team methods. On the other hand, tacit knowledge, the skills, or experience acquired through practice, may be shared through training programs/ orientations or on-the-job simulations and training. Each form of knowledge can serve as a tool to acquire the other; however, they cannot convert into one another. Understanding these epistemological dimensions and their interplay provides organisations and teams with the ability to learn, innovate and develop competencies that can be used in future projects (Cook and Brown 1999 ). Additionally, the knowledge seeker must be careful of the subjective interpretation of success factors and avoid "superstitious learning" (Zollo and Winter 2002 ). Preconceived notions can be easily generated, and projects often falter because the needs of the beneficiaries have not been fully contemplated.

Human-centred approaches such as design thinking are considered a viable solution to integrate multidisciplinary knowledge, consumer insights and recognise the infrastructure needed to support the output provided. Design-thinking complements the learning process both through the collection of knowledge and its application. Not only does it tap into capacities that conventional problem-solving practices overlook, but also it brings balance between the rational/analytical side of thinking and the emotional/intuitive counterpart (Brown and Winter 2010 ). This approach has contributed significantly to ID project success and has been adopted by UNICEF, The World Food Programme, and the International Rescue Committee. Additionally, companies such as Frog and IDEO continue collaborating with NGOs to integrate this approach in development projects and programmes.

Programme thinking can also be explored to drive project success, as a given programme may involve coordinating multiple projects to achieve a specific outcome. In this sense, projects can focus specifically on their particular output whilst the programme can ensure that the outcome is delivered. In addition, projects can start and end under the programme umbrella. However, both approaches are complementary, and not all projects are part of a programme (OGC 2007 ). Lastly, given that the distinction between HA and ODA is less straightforward in practice (Fink and Redaelli 2011 ), LRRD has been identified as a model that could bridge the grey zone between both sides of the international assistance spectrum (Kopinak 2013 ). Programmes, rather than singled out projects, can be used to provide a successful LRRD as they can coordinate and oversee the implementation of a set of related projects to deliver an outcome greater than the sum of its parts (OGC 2007 ).

The literature review suggests that Project Management is a relatively new discipline in the Third Sector. Its methodologies have been progressively adopted and recognised as a possible remedy for poor ID performance (Landoni and Corti 2011 ; Golini and Landoni 2014 ). Logical Framework and Monitoring and Evaluation are widely adopted PM tools by NGOs (Golini et al. 2015 ; Steinfort and Walker 2011 ). Poor planning and coordination, inadequate beneficiary involvement and omission of LRRD have often provided unsustainable/unsuccessful outcomes. (Alexander 2002 ; Kopinak 2013 ) Project management, thus, alone is not enough to deliver a successful outcome. Outputs need to be supported by hard and soft services, and beneficiaries must be considered in project design phases (Steinfort and Walker 2011 ; Alexander 2002 ; Kopinak 2013 ). Projects generate value and learning. The customer value generated from the project should be considered to determine project success (Rodrigues et al. 2014 ). Design thinking complements the learning process both through the collection of knowledge and its application. Human-centred approaches increase the possibility to create sustainable solutions and achieve success by incorporating interpersonal elements into the existing paradigm (Winter et al. 2006 ; Brown and Winter 2010 ). The distinction between HA and ODA is not always straightforward. LRRD, Design Thinking and programme implementation can help ID projects deliver successful and sustainable outcomes (Fink and Redaelli 2011 ). These arguments lead to the following proposition:

Project management can contribute to HA projects by providing better planning, coordination and knowledge generation. PM can improve the outcome of HA projects; however, it is not the only success factor. Infrastructure (hard and soft services) must be available to support the project outcome Footnote 7 , and most importantly, such outcome should align with the broader culture and needs of the beneficiaries. Design thinking offers PM ways of including the end-users, ensuring outcomes are fit for purpose and that customer value is generated.

3 Methodology

Primary and secondary data were used to explore the effects that implementation of Project Management tools and techniques could have on the success of humanitarian projects. First, secondary qualitative data was explored via a systematic literature review. The review provided a synthesis of extant knowledge and helped create an expert database for conducting interviews as primary research (Hasson and Keeney 2011 ). Given the exploratory nature of this research, we interviewed a limited number of experts (mentioned in Table 2 ) in the fields of PM, ID and design thinking. Given that the purpose was to explore in-depth the expert's views on humanitarian aid and their particular field, discuss their findings, and find additional study paths, the interviews were kept unstructured. Each interview lasted approximately 30 to 45 minutes.

Computer-Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software (CAQDAS) was used for the data analysis to aid continuity, transparency and methodological rigour. Via Nvivo, the literature was coded following a template analysis, which combines deductive and inductive approaches. This meant that the literature could be coded using predetermined information (like the challenges or success factors identified in the literature review) and at the same time amend or add codes as more data was collected and analysed. This approach permitted exploring key themes and identifying emerging issues. Once all the codes were established, MS-Excel was used to measure the data from the 33 sources selected and display the data to facilitate comparisons through graphs. Ordinary scales from zero to five (from least relevant to most relevant) were used to rank-order the codes (variables) according to the importance that each author gave to each category (Sekaran and Bougie 2016 ).

Given that the authors did not focus solely on any of the variables, none of the categories ranked five, and most were rated two or three. Additionally, the graphs included the number of journals that mentioned the categories rated to give the audience a clearer view of each variable's " real" frequency. Finally, to prove reliability, the consistency of the rankings was confirmed by four volunteers unrelated to the study. These volunteers were given samples of 10 different journals. This exercise helped find and correct mistakes and strengthen validity. It also served as a point of discussion regarding the findings of this research.

There was not enough literature regarding project management in ID projects (Diallo and Thuillier 2005 ; Golini and Landoni 2014 ), including humanitarian projects. To overcome the limitation of data scarcity, the findings on PM applications in ODA projects were considered and later adapted to humanitarian projects. It was a straightforward process, given that the main difference between these types of assistance is the spontaneity of the event and the time horizon (Golini and Landoni 2014 ). Similarly, the overall theory on design and innovation was studied and further shaped into its use in the International Development field, focusing on humanitarian relief. The sources selected were published within the last ten years to gather the most recent information. This critical selection included the collection of academic and scientific journals published under the Association of Business School (ABS/AJG) rankings (Table 3 ). In addition, other research databases, like Scopus and Web of Science were also considered, non-ABS/AJG listed journal listed in these databases like The Journal of Humanitarian Assistance, Design Issues Journal, Standford Social Innovation, Centre for Research on Epidemiology of Disasters, UK Department for International Development, Evaluation and Program Planning Journal, International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, and International Journal of Advanced Intelligence Paradigms were also included, as they provided relevant information and helped overcome the obstacle of the limited available literature. Additional sources include books, conference reports and other official publications that focused on the chosen area.

4 Data analysis and discussion

This section presents the results obtained from the analysis of data described in part three. In line with the initial objectives, Sect. 1 highlights the challenges encountered in HA projects and factors contributing to HA project failure and success. Section 2 reports the benefits that PM brings into this field and the importance of the cognitive process in exploratory projects of this nature. Lastly, Sect. 3 revisits the link between PM and design theory and how human-centred approaches can contribute to sustainable projects.

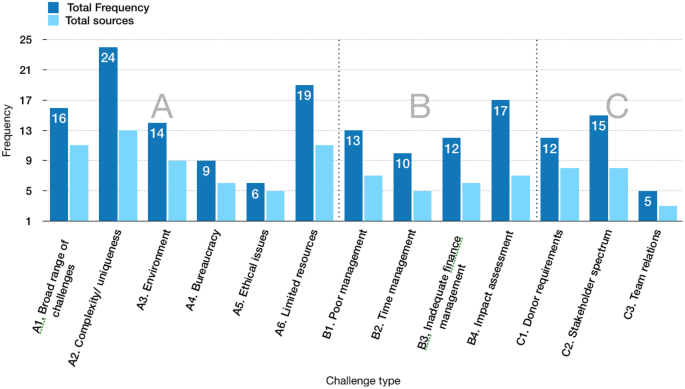

4.1 Challenges, failure, and success

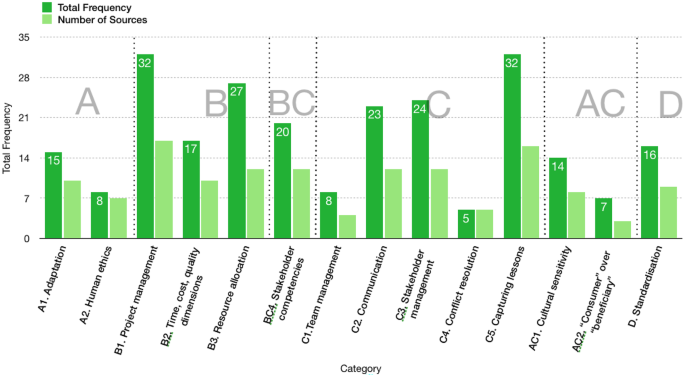

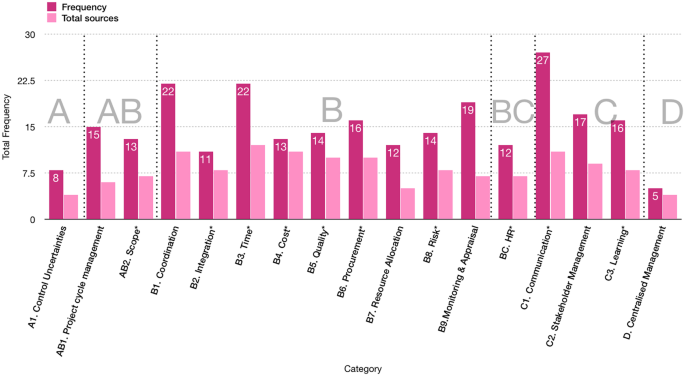

Figure one illustrates the main challenges in Humanitarian Aid projects. The graph further divides obstacles into four subcategories representing: A) the characteristics of the external environment and uncontrollable factors, B) general management and the "iron" triangle of Time, Cost, and Quality (TCQ), C) human-based management and challenges, and D) others. This categorisation Footnote 8 was derived as a common theme throughout the findings. It continues throughout the graphs of this section to link the commonalities between them and show the importance of PM in each of these levels.

HA challenges are broad[1, A1] Footnote 9 , and they are growing in scale, scope and complexity. All of these challenges are interlinked and often dependent on one another. Complexity[1, A2], for example, encompasses the diversity of time lines[1, B2] roles and stakeholders[1, C2] that must be coordinated in HA projects, adding a layer of difficulty as some of these are not clearly defined. Limited resources[1, A6], including lack of human skills, were the second biggest challenge. They are followed by the complications of assessing impact/quality[B4] given the poor feedback and control mechanisms recognised in this sector. Furthermore, the high number of stakeholders[1, C2] was considered more critical than the unique and unpredictable context in emergency settings[1, A2, A3]. The greater the stakeholder spectrum, the more coordination, communication, needs and requirements[1, C1] to be met; it also increases the opacity of authority lines and responsibilities[1, A2]. It was also discovered that the greater the power distance is between donors and recipients, the harder it is to meet donor requirements[1, C1]. Additionally, high levels of bureaucracy[1, A4] contribute to delays[1, B2], and personal agendas[1, A5] might interfere with project outcomes if, for example, managers were more concerned about their relationship with particular politicians or status in the public/private sector, rather than on the community burden (Diallo and Thuillier 2004 ). Together with the absence of PM methodologies, these challenges usually result in poor project planning, superficial risk management strategies, paucity of accountability and stakeholder involvement, unmotivated project teams, and eventually costing project success (Kelecklaite and Meiliene 2015 ).

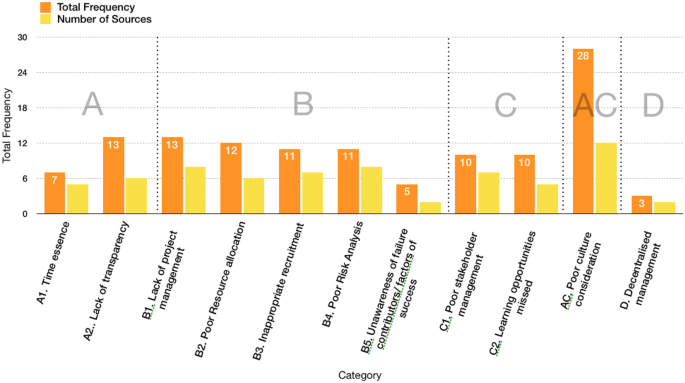

Failure factors

Figure two presents additional omissions that not only hinder success but can also lead to project failure. Insufficient culture consideration[2, AC] was regarded as the most relevant contributor to failure. Lack of shared perception between donors, project managers, and end-users can result in poor beneficiary inclusion and omission of community needs during planning and delivery stages. Exclusion of factual information, dishonesty, and lack of transparency[2, A2] came second; these include corruption and political manipulation, shaky government policies and lack of transparency derived from the difficulty of breaking down costs incurred in HA (Kopinak, 2013 ). Finally, lack of or poor PM[2, B1] was one of the most critical factors, mainly as factors mentioned in sections B and C can be managed through this discipline.

Furthermore, resource allocation[2, B2] amongst relief projects has been denounced disproportionately not only in terms of goods and skills but financially; some operations have been "forgotten" as they receive little or no help from donors, while others receive more than is necessary. Next came inappropriate recruitment[2, B3] and flawed risk analysis[2, B4]. Inappropriate recruitment disrupts team functions and service delivery, reflecting negatively on the donor and hindering project management and future finance. Lack of experience also reflects poor cultural perceptions[2, AC], including difficulty adapting to the environment and having an unbalanced view of local values, beliefs, and infrastructure. Finally, inexperience often results in workplace stress, frustration, anger and lack of empathy to the host country.

Success Factors

Figure three identifies that PM[3, B1], lessons captured[3, C5], resource allocation[3, B3], stakeholder management[3, C3], and communication[3, C2] are the key factors to consider to achieve success in HA projects. As the literature review suggested, capturing lessons is critical for success, helping to achieve continuous improvement. Knowledge creation and capture[3, C5] can happen at all stages and levels of the project life cycle. Lessons gained should be transmitted to subsequent projects to prevent the repetition of mistakes (Golini et al. 2015 ). Additionally, managers must know that learning opportunities are missed when managers are reluctant to admit mistakes, leading to losing some donor funding (Marlow 2016 ). Furthermore, PM[3, B1] was equally relevant and given that the PLC is included under this category, it can be inferred that the importance of planning has also been considered. Although communication[3, C2] was not as frequently mentioned, it is a critical success factor as it relates to other categories such as team management, motivation and leadership[3, C1], conflict resolution[3, C4], cultural sensitivity[3, AC1] and in choosing a particular language to refer to the end users[3, AC2]. Lastly, standardisation[3, D] was suggested to improve the application of PM methodologies and obtain more objective results from evaluation and feedback mechanisms. It was also significant to better understand success and failure contributing factors[2, B5], as well as to improve finance and resource allocation[2, B2], prioritisation of stakeholder needs[2, AC], ethical practices[3, A2], and reduction of coordination problems[7, B1, C1] and time frames.

4.2 Benefits of project management in humanitarian assistance

The general belief that enthusiasm and empathy are the essential skills of aid workers leads to staff that have unsuitable skills and experience (Kopinak 2013 ). As both literature and findings suggest, HA project managers deal with A) a broad range of challenges outside their control, B) hard services to deliver, and C) human management at all levels. Fortunately, PM can add value, improve performance through each of 'its knowledge areas*, and facilitate Project Capability Building (PCB). Figure four highlights communication[4, C1] as one of the most beneficial tools, followed by time coordination[4, B3] and general organisation[4, B1], monitoring and appraisal[4, B9], and stakeholder management[4, C2].

Communication[4, C1] represents the single most crucial task faced. However, it is also considered highly difficult in the HA context. The quality of information exchanged depends highly on trust, respect and values, and verbal and behavioural delivery and decoding. Furthermore, PM benefits projects by providing more realistic time frames[4, B3] and technical abilities to meet them[4, AB2]. This is particularly helpful in the case of exploratory projects as a means to identify cycles[4, AB1] such as the disaster areas: readiness, relief and recovery.

Time coordination[4, B3], allocation of resources[4, B7] and general organisation[B1] can be better achieved through the use of readiness stage, where possible scenarios[A1], governance indicators[4, A1] and preliminary planning can be applied to ensure quick and efficient crisis response as well as cost reduction[4, B4]. Additionally, the disaster relief stage supports logistics and procurement[4, B6] of both human and "basic" survival resources Footnote 10 , and disaster recovery serves as the transition to LRRD[4, B2]. Moreover, methodologies like stakeholder matrix and organised breakdown structure, as well as knowledge areas like Human Resources (HR)[4, BC] and communication[4, C1], help address the challenge of complex stakeholder management[4, C2]. Tools like " project monitoring and evaluation matrix" are relevant to assess project impact and serve as feedback mechanisms to capture lessons[4, C3].

4.3 Cognitive process in exploratory projects

PM offers the opportunity to learn from projects, which is progressively essential to project success (Fig.8). While Sect. 1 identified the uniqueness and complexity of HA projects as a challenge, both exploratory Footnote 11 and exploitative Footnote 12 learning are closely linked to the degree of change in the environment (Brady and Davies 2004 ). Learning from exploratory projects is the process of discovering practical lessons from experiences that could not have been foreseen (Lampel et al. 2009 ). HA projects provide higher learning opportunity as patterns and behaviours can quickly become obsolete. Consequently, constant revision of organisational process permits focus and transforms ambiguous information into knowledge, hence the relevance of identifying cycles and applying monitoring and evaluation in all stages.

Similarly, the process of learning involves making sense of the culture, leadership and capabilities of the current context; it requires a level of receptivity and observation. These lessons can manifest as the creation of new solutions or as innovative processes. The latter is ontological to the cognitive process of exploratory projects, as innovation processes are driven mainly by experimentation. Exploratory projects bring higher opportunities for learning as they do not have definite specifications; their " openness" provides a baseline for the generation of new ideas (Lenfle 2014 ). In like manner, new management methods are encouraged given the levels of " unforeseeable uncertainties"; therefore, the process of learning through exploratory projects can be understood as a loop of selection and testing, an inductive process. However, learning must be captured either through a communication or through embedding the new knowledge into processes and combinations.

4.4 Discussion

It was expected that each of the categories (A, B and C) within the graphs would relate to one another across the different divisions: main challenges, factors of success, contributors to failure and PM contribution. Even though all of these categories are interrelated, the results differ from one division to another. Within challenges (Fig 1 ), the category that was considered the most relevant was the one relating to the external factors (A). In this sense, the results agree with the literature review, which suggests that the environment of HA projects is hostile and uncertain and that its complexity is the main hindrance to success. Moreover, within success factors (Fig 2 ), category C, relating to human-based management and challenges, was considered vital. This category made a high emphasis on communication and interpersonal skills. However, in contrast with what was expected from the literature, communication was not as frequently mentioned as other factors like the relevance of PM or lessons captured. Stakeholder management was also mentioned in both success factors (Fig. 2 ) and PM contributions (Fig. 4 ). However, contrary to what was expected from the literature, the consideration of the recipients and their inclusion in the project was not mentioned as such. It could be inferred that it is part of stakeholder management and that the lack of culture consideration was regarded as highly relevant within contributors to failure (Fig 3 ).

Source: Authors

Main Challenges in Humanitarian Aid Projects;

Contributors to HA Project Failure;

Success Factors in HA projects;

Nevertheless, including the beneficiaries in project design phases was expected to be the primary approach to planning and implementing HA projects. Additionally, the most relevant category in both failure factors (Fig 3 ) and PM contributions (Fig. 4 ) was in relation to the more technical and general management (B).

Contribution/knowledge areas of Project Management;

Furthermore, project leaders should harness the passion for positive social impact with careful and intentional planning. This confirms the suggestion from the literature review regarding the possibility of PM being a remedy for poor project performance. Furthermore, it indicates that PM management is critical to achieving successful coordination, time management and resource allocation, all of which were also suggested in the literature review. Despite being a critical factor in the literature review, it was surprising that programme end-users were shown to receive meagre attention and have not been considered necessary, mainly because beneficiaries are at the centre of creating a sustainable project.

For this precise reason, the literature suggested incorporating human-centred design in the planning and implementation and evaluation of HA projects and the benefits of treating the recipients as consumers. However, it seems like there is still a gap in both the literature and the practice between these fields.

5 Conclusion

Natural disasters' frequency and destructive capacity are on the rise, and a high number of international assistance projects are reported to have high failure rates and unsatisfactory performance. Moreover, the livelihood and survival of people in the affected communities are highly dependent on disaster relief projects. Therefore, third sector organisations must find ways to manage humanitarian aid effectively. The professionalisation of humanitarian response has contributed to the adoption of PM tools, and the development of NGO focused PM frameworks. However, there is still a gap concerning meeting the end users' needs and considering them in all parts of the project/disaster life cycle. As the literature identified, the latter is one of the factors of project success because it is linked with the degree of customer value and because including the beneficiaries can result in sustainable outcomes that manage to bridge relief, rehabilitation, and development.

The categorisation of the variables into HA environment and PM knowledge areas suggested that PM can contribute to humanitarian project success and that project manager can and should learn from exploratory projects. The scope of the challenges discovered was as complex as the literature suggested; the main challenges in achieving favourable HA project outcomes included limited resources, difficulty assessing the project's impact, and the broad stakeholder spectrum. Although it was initially assumed that the emergent nature of the exploratory projects hinders outcomes, it was discovered that the highly complex- uncertain, unstable, culturally diverse, and multiple stakeholders- environment could provide a fertile ground to activate the learning process and generate explicit and tacit knowledge. In this sense, it is only logical that capturing lessons and PM application is rated as the most critical factors to achieve project success. However, project managers must consider that patterns and behaviours in HA projects can quickly become obsolete and that constant revision of organisational process and communication allows the transformation of ambiguous information into knowledge.

In the same way, communication was one of the most relevant success factors, and the PM contribution was considered the most important. Findings suggested that communication is at the core of success because it is part of every process, from HR to coordinating with a diverse roster of stakeholders to permit the correct allocation of time, resources, procurement, etc. Communication is also vital to design thinking. It allows project managers to adapt to the environment and understand the needs of the end-users and engage with them to create solutions that are suitable for the communities affected. People must be placed at the centre of the project life cycle, and beneficiaries must be included in all project design phases. Further research into both the practical use and perceived benefits of human-centred design needs to be undertaken and the results contrasted with those of current standard practices. This would enable a fuller understanding of how these practices help and hinder the development of better outcomes for beneficiaries, leading to more synthesis between traditional and innovative project management approaches in the third sector.

In conclusion, project management, particularly in HA, goes beyond tools and methodologies. Managers must also possess high human skills to adapt to demanding environments, communicate appropriately, and engage with multiple stakeholders to achieve a successful project outcome. People are the common denominator throughout this study. Lack of stakeholder consideration and working from the preconceived notions of what needs, and solutions are detrimental to project success. Both donors and recipients matter, and project managers should prioritise accordingly and bridge the gap between donor-recipient relations to find innovative ways of meeting their requirements. In this sense, adopting design thinking can lead to more sustainable solutions and project success. Lastly, this report identified a gap in the literature relating to the promotion and efficacy of design thinking when implementing PM. Further research into both the practical use and perceived benefits of human-centred design needs to be undertaken and the results contrasted with those of current standard practices. This would enable a fuller understanding of how these practices help and hinder the development of better outcomes for beneficiaries, leading to more synthesis between traditional and innovative project management approaches in the third sector.

https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Social-and-economic-impact-COVID.pdf accessed 24 June 2021

https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_767028.pdf accessed 24 June 2021

https://www.statista.com/statistics/1093256/novel-coronavirus-2019ncov-deaths-worldwide-by-country/ accessed 24 June 2021

The process of acquiring knowledge through thought, experience and/or senses (New Oxford American Dictionary, 2010 ).

“Hard” services refer to transportation links, water, electricity, etc. (Steinfort and Walker 2011 ).

Soft” services involve the activities that help the community return to normal life, such as restoring dignity and morale of the community and providing help to overcome the trauma of the catastrophe (Steinfort and Walker 2011 ).

Rebuilding schools without making sure that children live in a safe home, or building a water centre that does not provide containers to easily carry clean water, are some examples of how absence of hard and soft services delay project outcome (Brown and Winter, 2010 ).

This categorisation was organised in a way that it separated external/less controllable factors (A), from variables that can relate directly to PM knowledge areas (B&C). Further separating integration, scope, TCQ, risk management, procurement and justification (B), from more human based related variables: HR, stakeholder and communication.

Please read [1, A1] as figure 1, bar-chart A1.

Mainly food, shelter and medicine.

Knowledge acquired in exploratory projects (Brady and Davies 2004 )

What results of exploratory learning as it develops into new capabilities (Brady and Davies 2004 )

References

Alexander D (2002) Principles of emergency planning and management. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Google Scholar

Brady T, Davies A (2004) Building Project Capabilities: From Exploratory to Exploitative Learning. Organisation Studies 25(9):1601–1621

Article Google Scholar

Brown, T. and Winter, J. (2010). Design thinking for social innovation. Stanford Social Innovation Review

Cook SDN, Brown JS (1999) Bridging Epistemologies: The Generative Dance Between Organizational Knowledge and Organizational Knowing. Organ Sci 10(4):381–400

Diallo A, Thuillier D (2004) The success dimensions of international development projects: the perceptions of African project coordinators. Int J Proj Manag 22(1):19–31

Diallo A, Thuillier D (2005) The success of international development projects, trust and communication: an African perspective. Int J Proj Manag 23(3):237–252

Fink G, Redaelli S (2011) Determinants of International Emergency Aid—Humanitarian Need Only? World Development 39(5):741–757

Golini R, Kalchschmidt M, Landoni P (2015) Adoption of project management practices: The impact on international development projects of non-governmental organisations. Int J Proj Manag 88(3):650–663

Golini R, Landoni P (2014) International development projects by non-governmental organisations: an evaluation of the need for specific project management and appraisal tools. Impact Assess Proj Apprais 35(2):121–135

Great Britain. Office of Government, C (2007) Managing successful programmes, 3rd edn. TSO, London

Guha-Sapir D, Hoyois Ph., Wallemacq P. Below. R (2016) Annual Disaster Statistical Review 2016: The Numbers and Trends. Brussels: CRED

Hasson F, Keeney S (2011) Enhancing rigour in the Delphi technique research. Technol Forecast Soc Change 78(9):1695–1704

Kelecklaite, M. and Meiliene, E. (2015). The importance of project management methodologies and tools in non-governmental organizations: case study of Lithuania and Germany. PM World Journal Vol. 4, pp. 1–17

Kopinak, J. (2013). Humanitarian Aid: Are Effectiveness and Sustainability Impossible Dreams? The Journal of Humanitarian Assistance. pp. 1–14

Lampel J, Shamsie J, Shapira Z (2009) Experiencing the Improbable: Rare Events and Organizational Learning. Org Sci 20(5):835–845

Landoni, P. & Corti, B. (2011). The management of international development projects: moving toward a standard approach or differentiation? Project Management Journal. pp. 45–61

Lenfle S (2014) Toward a genealogy of project management: Sidewinder and the management of exploratory projects. Int J Proj Manag 32(6):921–931

Lenfle S, Midler C, Hallgren M (2019) Exploratory Projects: From Strangeness to Theory. Proj Manag J 50(50):519–523. https://doi.org/10.1177/8756972819871781

Lindberg, C. and Stevenson, A. (2010). New Oxford American Dictionary. Oxford University Press, New York.

Lindell MK, Prater CS (2002) Risk area residents’ perceptions and adoption of seismic hazard adjustments. J Appl Soc Psychol 32:2377–2392

Marlow M (2016) Weight-Loss Nudges: Market Test or Government Guess?. In: Abdukadirov S. (eds) Nudge Theory in Action. Palgrave Advances in Behavioral Economics. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31319-1_8

Meredith J, Shafer S, Mantel S, Sutton M (2014) Project management in practice. Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ

Morton, A. (2013). Emotion and Imagination. Cambridge

Myers, D.G. (2015) Exploring Social Psychology. 7th Edition, McGraw-Hill Education, New York

Noham, R. and Tzur, M. (2014) The Single and Multi-Item Transshipment Problem with Fixed Transshipment Costs. Naval Research Logistics, 61, 637-664. https://doi.org/10.1002/nav.21608

Radujkovic M, Sjekavica M (2017) Development of a project management performance enhancement model by analysing risks, changes, and limitations. GRADEVINAR 69(2):105–120

Rodrigues JS, Costa AR, Gestoso CG (2014) Project Planning and Control: Does National Culture Influence Project Success? Procedia Technology 16:1047–1056

Sekaran U, Bougie R (2016) Research Methods for Business, 7th edn. Wiley, Italy

Steinfort P, Walker D (2011) What Enables Project Success: Lessons from Aid Relief Projects . Drexel Hill, Project Management Institute.

Tayntor C (2010) Project Management Tools and Techniques for Success. CRC Press

Walker G (2011) The role for community in carbon governance. WIREs Climate Change 2:777–782. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.137

World Bank (1995) World Development Report 1995: Workers in an Integrating World. New York: Oxford University Press. © World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/5978

Winter M, Smith C, Morris P, Cicmil C (2006) Directions for future research in project management – The main findings of a UK government-funded research network. International Journal of Project Management 24(8):638–649

Zollo M, Winter SG (2002) Deliberate learning and the evolution of dynamic capabilities. Organization Science 13(3):339–351

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Stavanger, University of Stavanger Business School, Stavanger, Norway

Arvind Upadhyay

Sustainable Projects, Mexico City, Mexico

Maria Jose Perezalonso Hernandez

Indian Institute of Management Lucknow, Lucknow, India

Krishna Chandra Balodi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Arvind Upadhyay .

Ethics declarations

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Upadhyay, A., Hernandez, M.J.P. & Balodi, K.C. Covid-19 Disaster relief projects management: an exploratory study of critical success factors. Oper Manag Res 17 , 1–12 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-021-00246-4

Download citation

Received : 25 June 2021

Revised : 27 October 2021

Accepted : 05 December 2021

Published : 26 April 2022

Issue Date : March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-021-00246-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Project management

- Disaster relief projects management

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Quick Links

- Genesis & Functions

- Vision, Mission & Strategic Plan

- Management Structure & Organizational Overview

- Executive Director

- NIDM Southern Campus

- Annual Training Calendar

- Training Archives

- Trainee Database

- Training Designs & Modules

- Case Study/Research

- Proceedings

- NIDM Disaster & Development Journal

- Newsletter (TIDINGS)

- Annual Reports

- Directories

- Policies, Legislations & Notifications

- NDMA Publications

- Miscellaneous

- Awareness Material

- Do's and Don'ts for Common Disasters

- Designing Safe House in an Earthquake Prone Area

- Safe Life Line Public Buildings

- School Safety

- Floods, Cyclones & Tsunamis

- Online Training

- Self Study Programme

- CFE-DM Director

- CFE-DM Staff

- Humanitarian Assistance Response Training (HART) - Conflict

- Humanitarian-Assistance-Response-Training (HART) - Disasters

- Health Emergencies in Large Populations (HELP)

- Disaster Management Reference Handbooks

Case Studies & Factsheets

- Reports & Studies

- Best Practices Pamphlets

- Topic Specific Resources

- Academic Partnership Program

- Climate Change Impacts

- COVID-19 Updates

Case Studies

- Fact Sheets

The CFE-DM case study series is aimed at helping to inform future U.S. Indo-Pacific Command response to disasters in the Indo-Asia-Pacific region. By capturing observations and lessons learned, it is hoped that the case studies will also help improve civil-military coordination as well as military-to-military cooperation.

USINDOPACOM Foreign Disaster Response in the Indo-Asia-Pacific April 1991 – January 2024

This report looks at U.S. military foreign disaster response operations in the Indo-Asia-Pacific region, and provides a brief summary of each event and the accompanying response from U.S. forces.

Partner Case Studies

CFE-DM partners with various academic institutions, humanitarian organizations, and service academies for various research and information sharing initiatives. A wide variety of case studies in civil-military coordination, disaster response and other humanitarian issues are featured on this page.

Naval Post Graduate School (NPS)

"Civil and Military Cooperation in International Humanitarian Operations" This is a teaching case study on civil-military coordination. The authors asked the question: ‘What can be done to improve civilian and military working relations?’ To get to an answer, the authors interviewed experts in disaster response, peacekeeping, economic development, and inter-cultural relation-building. Interviewees included staff from the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies (APCSS), and the Center for Excellence in Disaster Management and Humanitarian Assistance (CFE-DM)

"Peacekeeping and Women’s Rights Latin American Countries Rise to the Challenge" This case study explores Latin America’s shift towards training and educating military forces regarding inclusion and protection of women during peacekeeping operations, following trends across the world leading to greater female participation in peacekeeping as well as shifting priorities towards the protection of civilians. The personal stories of Latin American women in the military is highlighted throughout.

“United States Navy Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) Costs: A Preliminary Study” Abstract: “Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) operations, one of the core capabilities for USN need to be studied, particularly in these times of budget cuts, realignment of forces, and restructuring of the Services. We study selected past disasters to organize their costs and propose future studies that can provide operational and financial policy recommendations that will induce efficiency and effectiveness.”

“Death, taxes, and disasters: AFSOF’s utility in disaster response” “This thesis investigates the use of AFSOF as a rapid responder through two case studies: the 2004 HADR operation following the earthquake and tsunami in Southeast Asia and the HADR operation following the 2013 super typhoon in the central Philippines.”

Other Studies

While making every attempt to ensure the information is relevant and accurate, Center for Excellence in Disaster Management and Humanitarian Assistance does not guarantee or warrant the accuracy, reliability, completeness or currency of the information in the case studies listed below.

Action Contre Le Faim Disaster Risk Management and Climate Change Adaptation

All Partners Access Network (APAN) Case studies range from recent disaster responses (i.e., Typhoon Haiyan) to recent exercises (i.e., RIMPAC 2018)

AmeriCorps “A Case Study of the Incident Command System in Missouri” Summary description: “Indiana University School of Public and Environmental Affairs (SPEA) Spring 2016 Capstone class worked with the Corporation for National and Community Service (CNCS) to study the AmeriCorps Disaster Response Teams’ (A-DRTs) experiences under the Incident Command System (ICS) during recent deployments to the December 2015 flood in Missouri.”

Asian Development Bank (ADB) “Natural Disasters, Public Spending, And Creative Destruction: A Case Study Of The Philippines” Abstract: “Using synthetic panel data regressions, the paper shows that typhoon-affected households are more likely to fall into lower income levels, although disasters can also promote economic growth. Augmenting the household data with municipal fiscal data, the analysis shows some evidence of the creative destruction effect: Municipal governments in the Philippines helped mitigate the poverty impact by allocating more fiscal resources to build local resilience while also utilizing additional funds poured in by the national government for rehabilitation and reconstruction.”

Asia Pacific Center for Security Studies (APCSS) and S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University “Disaster Response Regional Architectures: Assessing Future Possibilities” Document description: “This report captures the workshop discussions and presents key findings and recommendations for policymakers and decision-makers in governments, international organizations, academic institutions, and civil societies.”

Center for Naval Analysis (CNA) “Improving U.S.-India HA/DR Coordination in the Indian Ocean” According to CNA’s website: “The CNA Corporation conducted this study to determine how the United States can best deepen coordination with India on humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HA/DR) in the Indian Ocean.”

Collaborating Centre for Oxford University and CUHK for Disaster and Medical Humanitarian Response (CCOUC) Various case study from CCOUC

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) Information on disaster risk management: case study of five countries: Jamaica” Document description: “Jamaica, as a result of its location in the north-western Caribbean basin, is prone to numerous specific natural hazards. These include hurricanes, of which recent hurricanes experienced within the last few years (and in fact since 1988 with hurricane Gilbert), have reminded us of Jamaica's great vulnerability to the effects of this hazard. Next, it is also envisaged that a large earthquake could do considerable damage to sectors of the population and to infrastructure and could result in displacement and homelessness among large sections of the population, particularly in the highly urbanized areas of the Kingston Metropolitan Area (KMA). These two hazards, though perhaps not the most frequent, have the potential to do the most widespread damage to the population and to infrastructure.

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Various Case Studies Featured Case Studies include: Risk Assessment, Design and Construction, Private- and Public-sector Cooperative Efforts, Costs and Funding Mechanisms, Expected Benefits, and Performance of the Measures in Subsequent Hazard Events.

International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) Various Case Studies Case studies are available on the following topics: Climate change, Disaster preparedness, Early warning, Food security and livelihoods, Population movement, Risk reduction, Shelter, Vulnerability and Capacity Assessments:

“Case Studies: Red Cross Red Crescent Disaster Risk Reduction in Action – What Works at Local Level, June 2018” Document description: “These case studies demonstrate the Red Cross Red Crescent contribution to climate-smart disaster risk reduction action in Asia Pacific”

“Risk reduction in practice: a Philippines case study” Document description: “Since 1995, the PNRC has broadened its approach towards more proactive risk reduction. With support from the Danish Red Cross (DRC), PNRC initiated community based disaster preparedness in five mountain, coastal and urban provinces.”

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) “Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Climate Change Adaptation” Document description: “The case studies were grouped to examine types of extreme events, vulnerable regions, and methodological approaches. For the extreme event examples, the first two case studies pertain to events of extreme temperature with moisture deficiencies in Europe and Australia and their impacts including on health. These are followed by case studies on drought in Syria and dzud, cold-dry conditions in Mongolia. Tropical cyclones in Bangladesh, Myanmar, and Mesoamerica, and then floods in Mozambique are discussed in the context of community actions. The last of the extreme events case studies is about disastrous epidemic disease, using the case of cholera in Zimbabwe, as the example.”

Naval Post Graduate School (NPS) “United States Navy Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) Costs: A Preliminary Study” Abstract: “Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) operations, one of the core capabilities for USN need to be studied, particularly in these times of budget cuts, realignment of forces, and restructuring of the Services. We study selected past disasters to organize their costs and propose future studies that can provide operational and financial policy recommendations that will induce efficiency and effectiveness.”

Civil and Military Cooperation in International Humanitarian Operations

Peacekeeping and Women’s Rights Latin American Countries Rise to the Challenge

Naval War College (NWC) Center on Irregular Warfare & Armed Groups (CIWAG) Case Studies From the NWC website: “CIWAG's aim is to make these cutting edge research studies available to various professional curricula that assist professionals preparing to meet the complex challenges of the post-9/11 world, while aiding the work of operators, practitioners, and scholars of irregular warfare.”

Overseas Development Institute (ODI) “Delivering disaster risk reduction by 2030: Country Case Studies” Document description: “These case studies form the basis of the report Delivering disaster risk reduction by 2030: Pathways to progress (2017) (annexes 2–10). They provide analysis of the Hyogo Framework for Action (2005-2015) (HFA) country reports of nine countries: low-income countries (Guinea Bissau, Togo and Nepal), lower-middle-income (Fiji, Sri Lanka and Thailand) and upper-middle-income (Czech Republic, Mexico, and St Kitts and Nevis). These countries have different starting points, trajectories of progress, risk profiles and levels of per capita income. The reports give a good indication of what was prioritized by governments from 2005 to 2015.”

Pacific Journalism Review “Social media and disaster communication: A case study of Cyclone Winston” Abstract: “This article presents an analysis of how social media was used during Tropical Cyclone Winston, the strongest recorded tropical storm that left a wake of destruction and devastation in Fiji during February 2016.”