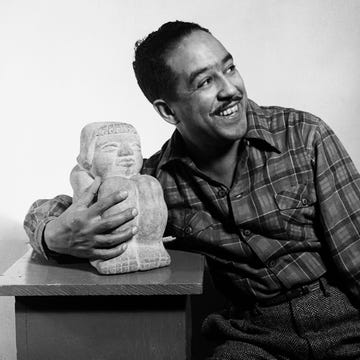

Biography of Langston Hughes, Poet, Key Figure in Harlem Renaissance

Hughes wrote about the African-American experience

Underwood Archives / Getty Images

- Favorite Poems & Poets

- Poetic Forms

- Best Sellers

- Classic Literature

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/JS800-800-5b70ad0c46e0fb00501895cd.jpg)

- B.A., English, Rutgers University

Langston Hughes was a singular voice in American poetry, writing with vivid imagery and jazz-influenced rhythms about the everyday Black experience in the United States. While best-known for his modern, free-form poetry with superficial simplicity masking deeper symbolism, Hughes worked in fiction, drama, and film as well.

Hughes purposefully mixed his own personal experiences into his work, setting him apart from other major Black poets of the era, and placing him at the forefront of the literary movement known as the Harlem Renaissance . From the early 1920s to the late 1930s, this explosion of poetry and other work by Black Americans profoundly changed the artistic landscape of the country and continues to influence writers to this day.

Fast Facts: Langston Hughes

- Full Name: James Mercer Langston Hughes

- Known For: Poet, novelist, journalist, activist

- Born: February 1, 1902 in Joplin, Missouri

- Parents: James and Caroline Hughes (née Langston)

- Died: May 22, 1967 in New York, New York

- Education: Lincoln University of Pennsylvania

- Selected Works: The Weary Blues, The Ways of White Folks, The Negro Speaks of Rivers, Montage of a Dream Deferred

- Notable Quote: "My soul has grown deep like the rivers."

Early Years

Langston Hughes was born in Joplin, Missouri, in 1902. His father divorced his mother shortly thereafter and left them to travel. As a result of the split, he was primarily raised by his grandmother, Mary Langston, who had a strong influence on Hughes, educating him in the oral traditions of his people and impressing upon him a sense of pride; she was referred to often in his poems. After Mary Langston died, Hughes moved to Lincoln, Illinois, to live with his mother and her new husband. He began writing poetry shortly after enrolling in high school.

Hughes moved to Mexico in 1919 to live with his father for a short time. In 1920, Hughes graduated high school and returned to Mexico. He wished to attend Columbia University in New York and lobbied his father for financial assistance; his father did not think writing was a good career, and offered to pay for college only if Hughes studied engineering. Hughes attended Columbia University in 1921 and did well, but found the racism he encountered there to be corrosive—though the surrounding Harlem neighborhood was inspiring to him. His affection for Harlem remained strong for the rest of his life. He left Columbia after one year, worked a series of odd jobs, and traveled to Africa working as a crewman on a boat, and from there on to Paris. There he became part of the Black expatriate community of artists.

The Crisis to Fine Clothes to the Jew (1921-1930)

- The Negro Speaks of Rivers (1921)

- The Weary Blues (1926)

- The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain (1926)

- Fine Clothes to the Jew (1927)

- Not Without Laughter (1930)

Hughes wrote his poem The Negro Speaks of Rivers while still in high school, and published it in The Crisis , the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The poem gained Hughes a great deal of attention; influenced by Walt Whitman and Carl Sandburg, it is a tribute to Black people throughout history in a free verse format:

I’ve known rivers: I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins. My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

Hughes began to publish poems on a regular basis, and in 1925 won the Poetry Prize from Opportunity Magazine . Fellow writer Carl Van Vechten, who Hughes had met on his overseas travels, sent Hughes’ work to Alfred A. Knopf, who enthusiastically published Hughes’ first collection of poetry, The Weary Blues in 1926.

Around the same time, Hughes took advantage of his job as a busboy in a Washington, D.C., hotel to give several poems to poet Vachel Lindsay, who began to champion Hughes in the mainstream media of the time, claiming to have discovered him. Based on these literary successes, Hughes received a scholarship to Lincoln University in Pennsylvania and published The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain in The Nation . The piece was a manifesto calling for more Black artists to produce Black-centric art without worrying whether white audiences would appreciate it—or approve of it.

In 1927, Hughes published his second collection of poetry, Fine Clothes to the Jew. He graduated with a bachelor’s degree in 1929. In 1930, Hughes published Not Without Laughter , which is sometimes described as a "prose poem" and sometimes as a novel, signaling his continued evolution and his impending experiments outside of poetry.

By this point, Hughes was firmly established as a leading light in what is known as the Harlem Renaissance. The literary movement celebrated Black art and culture as public interest in the subject soared.

Fiction, Film, and Theater Work (1931-1949)

- The Ways of White Folks (1934)

- Mulatto (1935)

- Way Down South (1935)

- The Big Sea (1940)

Hughes traveled through the American South in 1931 and his work became more forcefully political, as he became increasingly aware of the racial injustices of the time. Always sympathetic to communist political theory, seeing it as an alternative to the implicit racism of capitalism, he also traveled extensively through the Soviet Union during the 1930s.

He published his first collection of short fiction, The Ways of White Folks , in 1934. The story cycle is marked by a certain pessimism in regards to race relations; Hughes seems to suggest in these stories that there will never be a time without racism in this country. His play Mulatto , first staged in 1935, deals with many of the same themes as the most famous story in the collection, Cora Unashamed , which tells the story of a Black servant who develops a close emotional bond with the young white daughter of her employers.

Hughes became increasingly interested in the theater, and founded the New York Suitcase Theater with Paul Peters in 1931. After receiving a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1935, he also co-founded a theater troupe in Los Angeles while co-writing the screenplay for the film Way Down South . Hughes imagined he would be an in-demand screenwriter in Hollywood; his failure to gain much success in the industry was put down to racism. He wrote and published his autobiography The Big Sea in 1940 despite being only 28 years old; the chapter titled Black Renaissance discussed the literary movement in Harlem and inspired the name "Harlem Renaissance."

Continuing his interest in theater, Hughes founded the Skyloft Players in Chicago in 1941 and began writing a regular column for the Chicago Defender , which he would continue to write for two decades. After World War II and the Civil Rights Movement ’s rise and successes, Hughes found that the younger generation of Black artists, coming into a world where segregation was ending and real progress seemed possible in terms of race relations and the Black experience, saw him as a relic of the past. His style of writing and Black-centric subject matter seemed passé .

Children’s Books and Later Work (1950-1967)

- Montage of a Dream Deferred (1951)

- The First Book of the Negroes (1952)

- I Wonder as I Wander (1956)

- A Pictorial History of the Negro in America (1956)

- The Book of Negro Folklore (1958)

Hughes attempted to interact with the new generation of Black artists by directly addressing them, but rejecting what he saw as their vulgarity and over-intellectual approach. His epic poem "suite," Montage of a Dream Deferred (1951) took inspiration from jazz music, collecting a series of related poems sharing the overarching theme of a "dream deferred" into something akin to a film montage—a series of images and short poems following quickly after each other in order to position references and symbolism together. The most famous section from the larger poem is the most direct and powerful statement of the theme, known as Harlem :

What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun? Or fester like a sore— And then run? Does it stink like rotten meat? Or crust and sugar over— like a syrupy sweet? Maybe it just sags like a heavy load. Or does it explode ?

In 1956, Hughes published his second autobiography, I Wonder as I Wander . He took a greater interest in documenting the cultural history of Black America, producing A Pictorial History of the Negro in America in 1956, and editing The Book of Negro Folklore in 1958.

Hughes continued to work throughout the 1960s and was considered by many to be the leading writer of Black America at the time, although none of his works after Montage of a Dream Deferred approached the power and clarity of his work during his prime.

Although Hughes had previously published a book for children in 1932 ( Popo and Fifina ), in the 1950s he began publishing books specifically for children regularly, including his First Book series, which was designed to instill a sense of pride in and respect for the cultural achievements of African Americans in its youth. The series included The First Book of the Negroes (1952), The First Book of Jazz (1954), The First Book of Rhythms (1954), The First Book of the West Indies (1956), and The First Book of Africa (1964).

The tone of these children’s books was perceived as very patriotic as well as focused on the appreciation of Black culture and history. Many people, aware of Hughes’ flirtations with communism and his run-in with Senator McCarthy , suspected he attempted to make his children’s books self-consciously patriotic in order to combat any perception that he might not be a loyal citizen.

Personal Life

While Hughes reportedly had several affairs with women during his life, he never married or had children. Theories concerning his sexual orientation abound; many believe that Hughes, known for strong affections for Black men in his life, seeded clues about his homosexuality throughout his poems (something Walt Whitman, one of his key influences, was known to do in his own work). However, there is no overt evidence to support this, and some argue that Hughes was, if anything, asexual and uninterested in sex.

Despite his early and long-term interest in socialism and his visit to the Soviet Union, Hughes denied being a communist when called to testify by Senator Joseph McCarthy. He then distanced himself from communism and socialism, and was thus estranged from the political left that had often supported him. His work dealt less and less with political considerations after the mid-1950s as a result, and when he compiled the poems for his 1959 collection Selected Poems, he excluded most of his more politically-focused work from his youth.

Hughes was diagnosed with prostate cancer, and entered the Stuyvesant Polyclinic in New York City on May 22, 1967 to undergo surgery to treat the disease. Complications arose during the procedure, and Hughes passed away at the age of 65. He was cremated, and his ashes interred in the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, where the floor bears a design based on his poem The Negro Speaks of Rivers , including a line from the poem inscribed on the floor.

Hughes turned his poetry outward at a time in the early 20th century when Black artists were increasingly turning inward, writing for an insular audience. Hughes wrote about Black history and the Black experience, but he wrote for a general audience, seeking to convey his ideas in emotional, easily-understood motifs and phrases that nevertheless had power and subtlety behind them.

Hughes incorporated the rhythms of modern speech in Black neighborhoods and of jazz and blues music, and he included characters of "low" morals in his poems, including alcoholics, gamblers, and prostitutes, whereas most Black literature sought to disavow such characters because of a fear of proving some of the worst racist assumptions. Hughes felt strongly that showing all aspects of Black culture was part of reflecting life and refused to apologize for what he called the "indelicate" nature of his writing.

- Als, Hilton. “The Elusive Langston Hughes.” The New Yorker, The New Yorker, 9 July 2019, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/02/23/sojourner.

- Ward, David C. “Why Langston Hughes Still Reigns as a Poet for the Unchampioned.” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 22 May 2017, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/why-langston-hughes-still-reigns-poet-unchampioned-180963405/.

- Johnson, Marisa, et al. “Women in the Life of Langston Hughes.” US History Scene, http://ushistoryscene.com/article/women-and-hughes/.

- McKinney, Kelsey. “Langston Hughes Wrote a Children's Book in 1955.” Vox, Vox, 2 Apr. 2015, https://www.vox.com/2015/4/2/8335251/langston-hughes-jazz-book.

- Poets.org, Academy of American Poets, https://poets.org/poet/langston-hughes.

- 5 Writers of the Harlem Renaissance

- Men of the Harlem Renaissance

- Arna Bontemps, Documenting the Harlem Renaissance

- Literary Timeline of the Harlem Renaissance

- Black History Timeline: 1920–1929

- Harlem Renaissance Women

- Biography of James Weldon Johnson

- Black History Timeline: 1930–1939

- 5 Leaders of the Harlem Renaissance

- Biography of Georgia Douglas Johnson, Harlem Renaissance Writer

- An Early Verson of Flash Fiction by Poet Langston Hughes

- Women of the Harlem Renaissance

- 4 Publications of the Harlem Renaissance

- Zora Neale Hurston

- Biography of Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, African History Expert

- Poems to Read on Thanksgiving Day

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Langston Hughes

By: History.com Editors

Updated: December 15, 2023 | Original: January 24, 2023

Langston Hughes was a defining figure of the 1920s Harlem Renaissance as an influential poet, playwright, novelist, short story writer, essayist, political commentator and social activist. Known as a poet of the people, his work focused on the everyday lives of the Black working class, earning him renown as one of America’s most notable poets.

Hughes was born February 1, 1902 (although some evidence shows it may have been 1901 ), in Joplin, Missouri, to James and Caroline Hughes. When he was a young boy, his parents divorced, and, after his father moved to Mexico, and his mother, whose maiden name was Langston, sought work elsewhere, he was raised by his grandmother, Mary Langston, in Lawrence, Kansas. Mary Langston died when Hughes was around 12 years old, and he relocated to Illinois to live with his mother and stepfather. The family eventually landed in Cleveland.

According to the first volume of his 1940 autobiography, The Big Sea , which chronicled his life until the age of 28, Hughes said he often used reading to combat loneliness while growing up. “I began to believe in nothing but books and the wonderful world in books—where if people suffered, they suffered in beautiful language, not in monosyllables, as we did in Kansas,” he wrote.

In his Ohio high school, he started writing poetry, focusing on what he called “low-down folks” and the Black American experience. He would later write that he was influenced at a young age by Carl Sandburg, Walt Whitman and Paul Laurence Dunbar. Upon graduating in 1920, he traveled to Mexico to live with his father for a year. It was during this period that, still a teenager, he wrote “ The Negro Speaks of Rivers ,” a free-verse poem that ran in the NAACP ’s The Crisis magazine and garnered him acclaim. It read, in part:

“I’ve known rivers:

I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.”

Traveling the World

Hughes returned from Mexico and spent one year studying at Columbia University in New York City . He didn’t love the experience, citing racism, but he became immersed in the burgeoning Harlem cultural and intellectual scene, a period now known as the Harlem Renaissance.

Hughes worked several jobs over the next several years, including cook, elevator operator and laundry hand. He was employed as a steward on a ship, traveling to Africa and Europe, and lived in Paris, mingling with the expat artist community there, before returning to America and settling down in Washington, D.C. It was in the nation’s capital that, while working as a busboy, he slipped his poetry to the noted poet Vachel Lindsay, cited as the father of modern singing poetry, who helped connect Hughes to the literary world.

Hughes’ first book of poetry, The Weary Blues was published in 1926, and he received a scholarship to and, in 1929, graduated from, Pennsylvania’s Lincoln University. He soon published Not Without Laughter , his first novel, which was awarded the Harmon Gold Medal for literature.

Jazz Poetry

Called the “Poet Laureate of Harlem,” he is credited as the father of jazz poetry, a literary genre influenced by or sounding like jazz, with rhythms and phrases inspired by the music.

“But jazz to me is one of the inherent expressions of Negro life in America; the eternal tom-tom beating in the Negro soul—the tom-tom of revolt against weariness in a white world, a world of subway trains, and work, work, work; the tom-tom of joy and laughter, and pain swallowed in a smile,” he wrote in the 1926 essay, “ The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain .”

Writing for a general audience, his subject matter continued to focus on ordinary Black Americans. Hughes wrote that his 1927 work, “Fine Clothes to the Jew,” was about “workers, roustabouts, and singers, and job hunters on Lenox Avenue in New York, or Seventh Street in Washington or South State in Chicago—people up today and down tomorrow, working this week and fired the next, beaten and baffled, but determined not to be wholly beaten, buying furniture on the installment plan, filling the house with roomers to help pay the rent, hoping to get a new suit for Easter—and pawning that suit before the Fourth of July."

He also did not shy from writing about his experiences and observations.

“We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame,” he wrote in the The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain . “If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly too.”

Ever the traveler, Hughes spent time in the South, chronicling racial injustices, and also the Soviet Union in the 1930s, showing an interest in communism . (He was called to testify before Congress during the McCarthy hearings in 1953.)

In 1930, Hughes wrote “Mule Bone” with Zora Neale Hurston , his first play, which would be the first of many. “Mulatto: A Tragedy of the Deep South,” about race issues, was Broadway’s longest-running play written by a Black author until Lorraine Hansberry’s 1958 play, “A Raisin in the Sun.” Hansberry based the name of her play on Hughes’ 1951 poem, “ Harlem ” in which he writes,

"What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?...”

Hughes wrote the lyrics for “Street Scene,” a 1947 Broadway musical, and set up residence in a Harlem brownstone on East 127th Street. He co-founded the New York Suitcase Theater, as well as theater troupes in Los Angeles and Chicago. He attempted screenwriting in Hollywood, but found racism blocked his efforts.

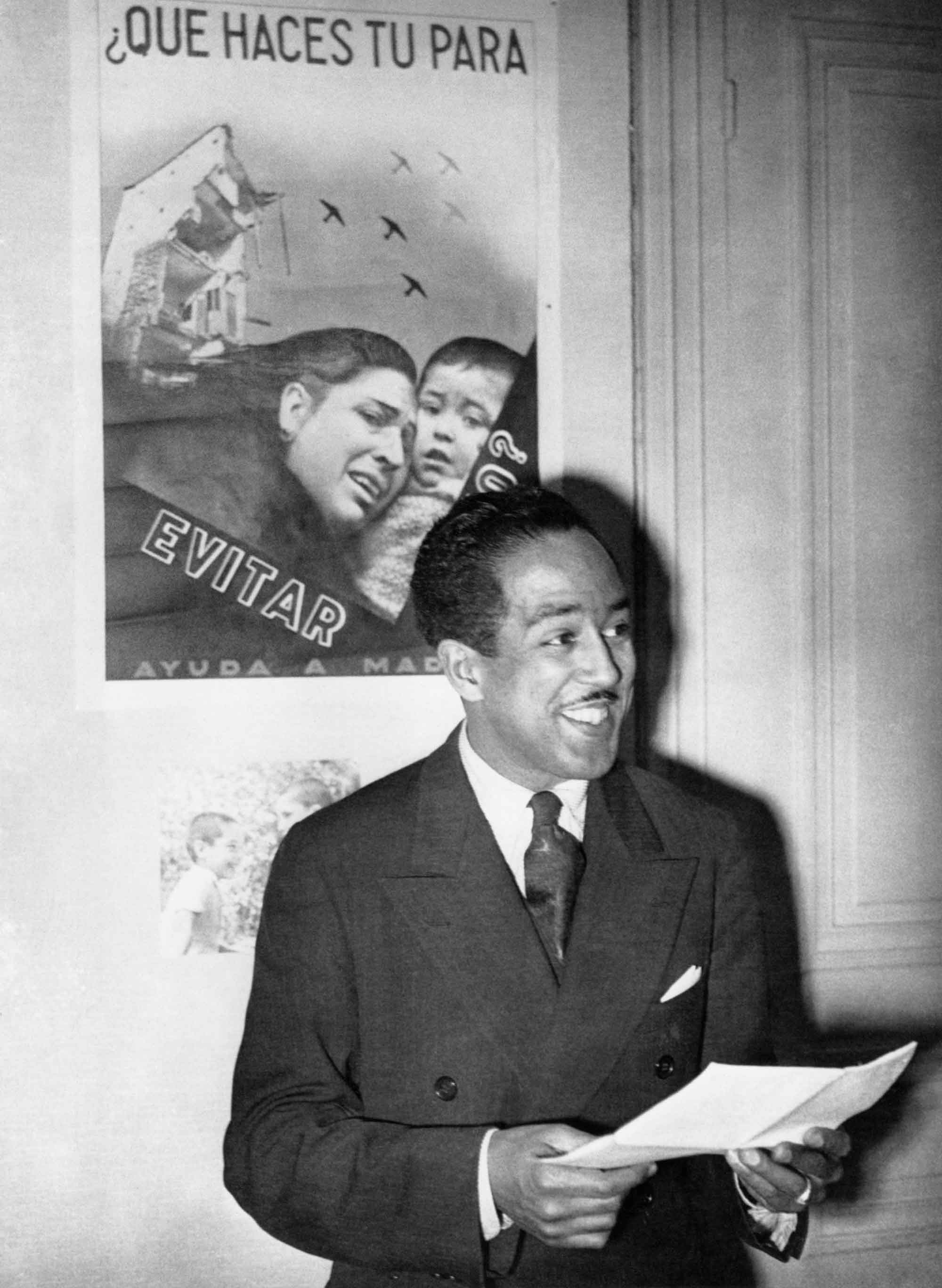

He worked as a newspaper war correspondent in 1937 for the Baltimore Afro American , writing about Black American soldiers fighting for the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War . He also wrote a column from 1942-1962 for the Chicago Defender , a Black newspaper, focusing on Jim Crow laws and segregation , World War II and the treatment of Black people in America. The column often featured the fictitious Jesse B. Semple, known as Simple.

In the 1950s and ’60s, Hughes wrote a “First Book” series of children's books, patriotic stories about Black culture and achievements, including The First Book of Negroes (1952), The First Book of Jazz (1955), and The Book of Negro Folklore (1958). Among the stories in the 1958 volume is "Thank You, Ma'am," in which a young teenage boy learns a lesson about trust and respect when an older woman he tries to rob ends up taking him home and giving him a meal.

Hughes died in New York from complications during surgery to treat prostate cancer on May 22, 1967, at the age of 65. His ashes are interred in Harlem’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. His Harlem home was named a New York landmark in 1981, and a National Register of Places a year later.

"I, too, am America," a quote from his 1926 poem, " I, too, " is engraved on the wall of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

“ Langston Hughes ,” The Library of Congress

“ Langston Hughes: The People's Poet ,” Smithsonian Magazine

“ The Blues and Langston Hughes ,” Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh

“ Langston Hughes ,” Poets.org

HISTORY Vault: Black History

Watch acclaimed Black History documentaries on HISTORY Vault.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Poetry Readings and Responses

Biography: langston hughes.

James Mercer Langston Hughes (February 1, 1902 – May 22, 1967) was an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist from Joplin, Missouri.

He was one of the earliest innovators of the then-new literary art form called jazz poetry. Hughes is best known as a leader of the Harlem Renaissance. He famously wrote about the period that “the negro was in vogue”, which was later paraphrased as “when Harlem was in vogue.”

First published in The Crisis in 1921, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” which became Hughes’s signature poem, was collected in his first book of poetry The Weary Blues (1926). Hughes’s first and last published poems appeared in The Crisis ; more of his poems were published in The Crisis than in any other journal. Hughes’s life and work were enormously influential during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, alongside those of his contemporaries, Zora Neale Hurston, Wallace Thurman, Claude McKay, Countee Cullen, Richard Bruce Nugent, and Aaron Douglas.

Hughes and his contemporaries had different goals and aspirations than the black middle class. They criticized the men known as the midwives of the Harlem Renaissance: W. E. B. Du Bois, Jessie Redmon Fauset, and Alain LeRoy Locke, as being overly accommodating and assimilating eurocentric values and culture to achieve social equality.

Hughes and his fellows tried to depict the “low-life” in their art: that is, the real lives of blacks in the lower social-economic strata. They criticized the divisions and prejudices based on skin color within the black community. Hughes wrote what would be considered their manifesto, “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” published in The Nation in 1926:

The younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly, too. The tom-tom cries, and the tom-tom laughs. If colored people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, their displeasure doesn’t matter either. We build our temples for tomorrow, strong as we know how, and we stand on top of the mountain free within ourselves.

His poetry and fiction portrayed the lives of the working-class blacks in America, lives he portrayed as full of struggle, joy, laughter, and music. Permeating his work is pride in the African-American identity and its diverse culture. “My seeking has been to explain and illuminate the Negro condition in America and obliquely that of all human kind,” Hughes is quoted as saying. He confronted racial stereotypes, protested social conditions, and expanded African America’s image of itself–a “people’s poet” who sought to reeducate both audience and artist by lifting the theory of the black aesthetic into reality.

Hughes stressed a racial consciousness and cultural nationalism devoid of self-hate. His thought united people of African descent and Africa across the globe to encourage pride in their diverse black folk culture and black aesthetic. Hughes was one of the few prominent black writers to champion racial consciousness as a source of inspiration for black artists. In addition to his example in social attitudes, Hughes had an important technical influence by his emphasis on folk and jazz rhythms as the basis of his poetry of racial pride.

View Upton Sinclair’s full biography on Wikipedia.

- Langston Hughes. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Langston_Hughes . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Image of Langston Hughes. Authored by : Carl van Vechten. Located at : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Langston_Hughes_by_Carl_Van_Vechten_1936.jpg . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

This site requires Javascript to be turned on. Please enable Javascript and reload the page.

Langston Hughes: Poems, Biography, and Timeline of his early career

Contents of this path:.

- 1 2022-01-05T15:17:55-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "The Weary Blues" (full text) (1926) 12 plain 2024-02-10T07:34:48-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2023-05-07T09:35:02-04:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "Fine Clothes to the Jew" (1927) (Full Text) 4 plain 2024-02-01T15:15:31-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2022-01-09T13:48:19-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Poems by Langston Hughes in "The New Negro" (1925) 1 plain 2022-01-09T13:48:19-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2022-01-05T15:14:17-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "The Negro Speaks of Rivers" (1921) 8 plain 2024-01-09T11:08:46-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2022-01-06T10:13:29-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "Aunt Sue's Stories" (1921) 3 plain 2022-07-02T08:31:28-04:00 07/01/1921 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2022-01-05T15:08:09-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "Song for a Banjo Dance" (1922) 4 plain 2024-01-09T10:53:16-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2022-01-06T10:16:44-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "When Sue Wears Red" (1923) 2 plain 2022-07-02T08:29:32-04:00 02/01/1923 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2022-07-19T14:25:59-04:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "Dreams" (1923) 1 plain 2022-07-19T14:25:59-04:00 05/01/1923 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2022-07-11T11:52:37-04:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "The Last Feast of Belshazzar" (1923) 1 plain 2022-07-11T11:52:37-04:00 08/01/1923 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2022-01-05T15:10:29-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "Winter Moon" (1923) 3 plain 2024-01-09T11:00:40-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2022-08-04T12:23:14-04:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "Song for a Suicide" (1924) 1 plain 2022-08-04T12:23:14-04:00 05/01/1924 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2022-08-16T08:40:49-04:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "Johannesburg Mines" (1925) 1 plain 2022-08-16T08:40:49-04:00 02/01/1925 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2022-08-16T08:39:13-04:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "Steel Mills" (1925) 1 plain 2022-08-16T08:39:13-04:00 02/01/1925 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2022-08-16T08:31:34-04:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "To Certain Intellectuals" (1925) 1 plain 2022-08-16T08:31:34-04:00 01/01/1925 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2022-07-11T12:55:18-04:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "To a Negro Jazz Band in a Parisian Cabaret" (1925) 2 plain 2022-07-11T12:56:07-04:00 12/01/1925 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2022-01-06T10:16:06-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "To the Black Beloved" (1925) 4 plain 2024-01-26T16:59:49-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2022-07-11T14:57:12-04:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "Love Song for Lucinda" (1926) 1 plain 2022-07-11T14:57:12-04:00 05/01/1926 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2022-01-06T10:29:14-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "Young Bride" (1925) 5 plain 2024-02-10T07:39:51-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2022-07-11T11:09:50-04:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "The Poppy Flower" (1925) 1 plain 2022-07-11T11:09:50-04:00 02/01/1925 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2022-01-06T10:32:10-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "Summer Night" (1925) 4 plain 2022-07-11T12:42:15-04:00 12/01/1925 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2022-07-11T13:00:50-04:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "A Song to a Negro Wash-woman" (1925) 1 plain 2022-07-11T13:00:50-04:00 01/01/1925 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2022-08-05T16:33:06-04:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "To Beauty" (1926) 1 plain 2022-08-05T16:33:06-04:00 10/01/1926 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2022-08-05T15:52:56-04:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "The Ring" (1926) 1 plain 2022-08-05T15:52:56-04:00 04/01/1926 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2024-03-12T07:08:12-04:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "Being Old" (1927) 1 plain 2024-03-12T07:08:12-04:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2024-03-10T08:39:01-04:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "Ma Lord" (1927) 1 plain 2024-03-10T08:39:01-04:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2024-03-05T11:41:36-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "For an Indian Screen" (1927) 1 plain 2024-03-05T11:41:36-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2024-03-05T11:43:29-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "Lincoln Monument" (1927) 2 plain 2024-03-05T11:45:02-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2024-03-05T12:33:07-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "I Thought it was Tangiers I Wanter" (1927) 1 plain 2024-03-05T12:33:07-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2024-03-05T11:44:23-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "Day" (1927) 1 plain 2024-03-05T11:44:23-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2024-03-05T11:42:34-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "Passing Love" (1927) 1 plain 2024-03-05T11:42:34-05:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2024-03-12T07:08:50-04:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "Freedom Seeker" (1927) 1 plain 2024-03-12T07:08:50-04:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2024-03-12T09:26:11-04:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "Montmartre Beggar Woman" (1927) 1 plain 2024-03-12T09:26:11-04:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

- 1 2024-03-10T08:49:52-04:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1 Langston Hughes, "Tapestry" (1927) 1 plain 2024-03-10T08:49:52-04:00 Amardeep Singh c185e79df2fca428277052b90841c4aba30044e1

This page references:

- 1 media/Langston Hughes Photo 1936 Carl Van Vechten_thumb.jpg 2022-01-21T09:31:56-05:00 Langston Hughes photo 1936 Carl Van Vechten 1 Langston Hughes photo 1936 Carl Van Vechten media/Langston Hughes Photo 1936 Carl Van Vechten.jpg plain 2022-01-21T09:31:56-05:00

- 1 media/langston hughes 1923_thumb.jpg 2022-07-21T10:50:03-04:00 Langston Hughes Photo 1923 1 Photo of Langston Hughes taken for Robert Kerlin's "Negro Poets and their Poems" (1923) media/langston hughes 1923.jpg plain 2022-07-21T10:50:03-04:00

National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Plan Your Visit

- Group Visits

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Accessibility Options

- Sweet Home Café

- Museum Store

- Museum Maps

- Our Mobile App

- Search the Collection

- Exhibitions

- Initiatives

- Museum Centers

- Publications

- Digital Resource Guide

- The Searchable Museum

- Freedmen's Bureau Search Portal

- Early Childhood

- Talking About Race

- Digital Learning

- Strategic Partnerships

- Ways to Give

- Internships & Fellowships

- Today at the Museum

- Upcoming Events

- Ongoing Tours & Activities

- Past Events

- Host an Event at NMAAHC

- About the Museum

- The Building

- Meet Our Curators

- Founding Donors

- Corporate Leadership Councils

- NMAAHC Annual Reports

Langston Hughes: The People's Poet

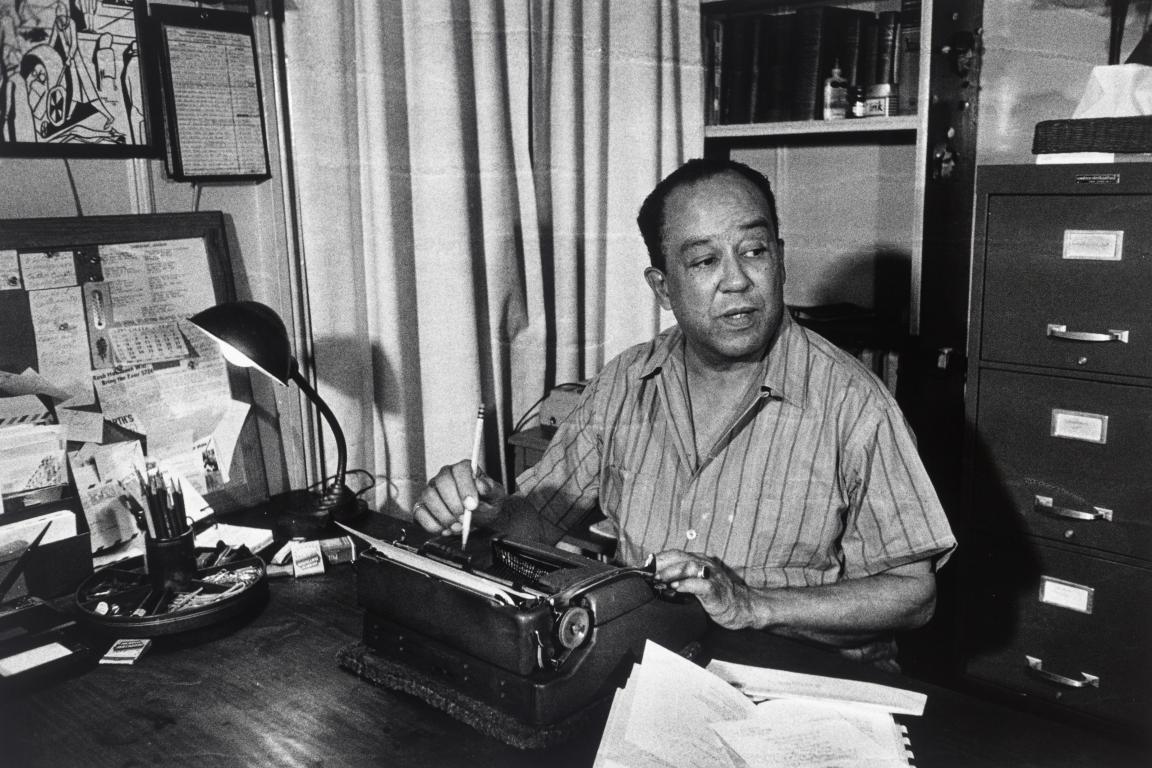

Sitting at his typewriter, a pencil in hand, Langston Hughes looks out just beyond the frame as though poised to capture and crystallize a verse still forming. The portrait, photographed by Louis H. Draper, gives only a glimpse of the writer who “simply liked people,” as Arnold Rampersad writes in the introduction to “Selected Letters of Langston Hughes.” “If he was lonely in essential ways, his main response to his pain was to create a body of art that others could admire and applaud.”

Born in Joplin, Missouri, in 1902, it was the writer's many years in Harlem that would come to characterize his work. There he focused squarely on the lives of working-class black Americans, delicately dismantling clichés and, in doing so, arriving at a genuine portrayal of the people he knew best.

But Hughes’s body of work, steeped as it was in stories of everyday life, was not without its critics. Hughes's writing, especially his use of the fictional character Jesse B. Semple (a.k.a. “Simple”) portrayed what critics saw as an unattractive view of black American life. Commenting on the writer's poetry collection, “Fine Clothes to the Jew,” EstaceGay asserted that “our aim ought to be [to] present to the general public, already misinformed both by well meaning and malicious writers, our higher aims and aspirations, and our better selves.” What such criticisms miss, however, is that Hughes's eloquently spare and humble verse was never disparaging. In telling stories of those he encountered, Hughes brought to light not only the drudgery but also the determination alive in Harlem.

Writing in Black World, one reviewer captured the popularity of Simple - a character who “lived in a world they knew, suffered their pangs, experienced their joys, reasoned in their way, talked their talk, dreamed their dreams, laughed their laughs, voiced their fears - and all the while underneath, he affirmed the wisdom which anchored at the base of their lives.” Hughes's beloved poem “I, Too” underlines both the empathy the writer showed for the working class and the quiet resistance these figures had come to represent. “Tomorrow, / I'll be at the table / When company comes … They'll see how beautiful I am / And be ashamed” Hughes’s unnamed first person is far from a passive observer of racism and its ruptures. Here is an individual sure of him or herself and confident in a justice still unrealized.

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, The Estate of Louis H. Draper

Indeed, the subtleties and singularities of Hughes’s characters set apart the writer’s work. Angela Flournoy echoes this sentiment in her review of “Not Without Laughter,” Hughes's debut novel . “Hughes accesses the universal - how all of us love and dream and laugh and cry - by staying faithful to the particulars of his characters and their way of life.” In the novel, themes of migration have particular resonance. It is the fascinating, intimate character studies Hughes offers which anchor an otherwise mercurial world. So, too, are the characters in his work resoundingly robust. By Hughes's own account, Simple “tells me his tales, mostly in high humor, but sometimes with a pain in his soul as sharp as the occasional hurt of that bunion on his right foot. Sometimes, as the old blues says, Simple might be ‘laughing to keep from crying.”

Here, then, are characters endowed with a depth akin to the river Hughes references in the much-beloved poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers.” In the poem's opening stanza the still unknown narrator recounts “I've known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in veins. / My soul has grown deep like the rivers.” One imagines from these lines that Simple, and other working-class Americans like him, knew comparable depths and, in finding their strength, realized the broader continuities between past and present trials.

Winold Reiss, "Langston Hughes," National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of W. Tjark Reiss, in memory of his father, Winold Reiss

What is inspiring about Hughes’s work, is that despite the hardship and hopelessness that colored his poetry and prose, he maintained a striking, confident assurance that a brighter future awaits. Typifying that impulse is Hughes’s poem “Let America Be America Again.” In one of the final stanzas, Hughes writes, “O, let America be America again - / The land that never has been yet - / And yet must be - the land where every man is free.”

Hughes knew the struggle of the working class intimately, indeed, he devoted much of the poem to it, while assuring readers that the future is a just one. This counterfactual history seems, at times, to be at odds with the stories of bigotry that emerge in Hughes's work in ways big and small. This hope, though, appears to derive less from mere idealism and more from the purview of a writer who, more than anything else, loved people and hoped - believed, even - that their work would not be in vain.

Indeed, it was Hughes's realistic idealism that made him the celebrated writer he is today. As raw as racism once was and as traumatizing as it still is, bringing to light the stories of the oppressed seems an enduring antidote - a phenomenon Hughes knew well. The writer was resolute in listening to the stories of the working class and telling those stories in a language they understood. By so doing, he reflected the beauty and boundlessness of the Harlem he experienced every day.

Subtitle here for the credits modal.

Langston Hughes

Scroll down ↓.

Langston Hughes—known early in his career as “Poet Laureate of the Negro Race” and, now, as the preeminent poet of the Harlem Renaissance—was born James Mercer Langston Hughes in Joplin, Missouri to Carrie Langston and Charles Hughes. Recent revelations from historical African American weekly newspapers strongly suggest his birth year as 1901, though he believed that he had been born a year later. Hughes’s birth date was never officially noted because Missouri did not require the registration of births.

In the first installment of his autobiography, The Big Sea , Hughes noted that he could not truly consider himself Black, due to the “different kinds of blood in [his] family.” His mother, Mary Langston, was born to Charles Langston and Mary Sampson Patterson. Mary was of French and indigenous ancestry on her mother’s side. Hughes recalled that she “looked like an Indian—with very long black hair.” Mary had first married a free Black man named Sheridan Leary in Oberlin, Ohio, where she had attended college. Unbeknownst to Mary, her husband left home to join John Brown during the abolitionist’s raid at Harper’s Ferry in Virginia. Leary died on the first night of the rebellion. Not long after her first husband’s death, Mary met Langston, who owned both a farm and a grocery store in Lawrence, Kansas. Like Leary, Langston was deeply invested in politics, so much so that he left his businesses to languish. After he died, he left his family with no money but plenty of his speeches.

On his father’s side, Hughes had two white great-grandfathers. One was Silas Cushenberry—a Jewish slave trader from Kentucky; the other was Sam Clay, a distiller of Scotch ancestry who was rumored to have been a relative of the renowned Kentucky senator Henry Clay.

Hughes’s parents separated shortly after he was born. Charles moved to Mexico to escape white mob violence in Joplin. When Hughes was five or six, his parents reconciled briefly when Charles invited him, Carrie, and Mary to live with him in Mexico City. After a massive earthquake, Carrie returned to Kansas with her mother and son. Hughes did not see his father again until he was seventeen. Some years later, Carrie married Homer Clark, an occasional chef from Topeka, Kansas who also supported the family with odd jobs in steel mills and coal mines. Together, Carrie and Homer had a son.

Hughes was raised by his grandmother, Mary Langston, in Lawrence, Kansas until he was 13. Mary was a conductor on the Underground Railroad with her first husband, Lewis Sheridan Leary, one of the men who helped John Brown attack Harpers Ferry. Hughes had difficult relationships with both of his parents and his grandmother. He claimed that he despised his father, whose expressed loathing for other Black people led Hughes to become estranged from him. In the summer of 1915, Carrie invited her son to move to Lincoln, Illinois. Hughes spent the next several years living with her there, in Cleveland, and in Chicago.

Hughes began writing poetry after he returned to Cleveland as a high school sophomore. He contributed verse to the school magazine, Central High Monthly , and later became its editor. He listed Paul Laurence Dunbar, Walt Whitman, and Carl Sandburg among his main poetic influences. After he graduated from high school, he composed one of his best-known poems, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers.” He then went to central Mexico for a year to spend time with his father and study Spanish. Meanwhile, Hughes sent three poems to Jessie Redmon Fauset to publish in the Brownies’ Book for children. Fauset published two of his submissions in the January 1921 edition. Five months later, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” was published in the June 1921 issue of the Crisis .

Hughes moved to Harlem in September 1921 and supported himself by working odd jobs. He became a seaman in the summer of 1923, traveling throughout West Africa and Europe. During a stint in Paris, he worked as a busboy at Le Grand Duc, a nightclub in Montmartre. There, he met and befriended numerous Black performers, including future famed nightclub hostess, Ada “Bricktop” Smith.

He returned to the United States and moved to Washington, D.C., working again as a busboy. One day, he waited on Vachel Lindsay at a hotel restaurant and slipped him a copy of “The Weary Blues.” Lindsay accepted the poems and later claimed to have discovered Hughes. In 1926, Hughes enrolled at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania and published his first collection, The Weary Blues (1926). The year was a prolific one. He wrote the manifesto “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain” for the Nation magazine, sponsored the short-lived Fire!! Magazine, and worked on O Blues! , a musical project for producer and future patron of Josephine Baker, Caroline Dudley Reagan. He also published a second poetry collection, Fine Clothes to the Jew (1926).

In 1929, Hughes earned a Bachelor of Arts and published his first novel, Not Without Laughter (1930), which won the Harmon gold medal for literature—an award “for distinguished achievement among Negroes.” He resumed his travels in 1932—this time going across the Pacific. He moved to the Soviet Union and traveled from Moscow to Vladivostok on the Trans-Siberian Railroad. He also visited countries in East Asia.

In 1933, Hughes moved to California but showed no sign of settling permanently in the U.S. He returned to Paris in 1937, where he met poet and future Senegalese president Léopold Sédar Senghor. He then traveled with Cuban poet Nicolás Guillén, whom he met in 1930, to Spain, where he worked as a newspaper correspondent during the Spanish Civil War.

In 1940, Hughes published The Big Sea , an autobiography that covered his life until 1931. The second, I Wonder as I Wander , was published in 1956. After releasing the book-length poem, Montage of a Dream Deferred (1951), Hughes shifted toward prose. He began publishing the “Simple” books: Simple Speaks His Mind (1950), Simple Stakes a Claim (1957), Simple Takes a Wife (1953), and Simple’s Uncle Sam (1965).

His career also included the publication of eleven plays, including Mule Bone (1930, 1991), co-written with Zora Neale Hurston; translations of numerous other poets’ work from Spanish and French, including Guillén’s; two anthologies co-edited with Arna Bontemps; and nine additional collections of poetry. Hughes’s final collection, The Panther and the Lash (1967), published posthumously, expressed his thoughts on Black Power and the Black Panther Party.

After his death, the city of New York declared his residence on East 127th Street in Harlem a cultural landmark and renamed the street “Langston Hughes Place.” Hughes bequeathed his personal library to Lincoln University. His ashes are interred under the floor of the lobby in the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture beneath a cosmogram memorial that quotes his poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers.”

Sources

Hughes, Langston. T he Big Sea: An Autobiography of Langston Hughes . New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1940, 1993.

Rampersad, Arnold. The Life of Langston Hughes: Volume I: 1902-1941, I, Too, Sing America . New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

Rampersad, Arnold. The Life of Langston Hughes: Volume II: 1941-1967, I Dream a World. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

▽ Full Bio △

Watch & listen.

POems by LaNgsToN HUghEs

.jpg)

(92) 336 3216666

Langston Hughes

James Mercer Langston Hughes was an American novelist, poet, playwright, social activist, and columnist. He made his career in New York City, where he shifted when he was quite young. Langston Hughes was one of the innovators of the new genre poetry known as jazz poetry. He is also known as the leader of the Harlem Renaissance. He wrote about the period when Negro was in trend, and this period was rephrased as when Harlem was in trend.

Hughes became a creative writer from a very early age, growing up in different Midwestern towns. Hughes attended high school in Cleveland, Ohio, and after graduation attended Columbia University, New York City. He was dropped out of the university; still, he got a notice from the publishers in New York City. He was immediately recognized in the creative community in Harlem because of his writing, particularly poems. Besides poetry, Hughes also wrote short stories and plays. He also published some nonfiction works. He immensely wrote about the civil rights movement (from 1942 to 1962) in a weekly column.

A Short Biography of Langston Hughes

Langston Hughes (James Mercer Langston Hughes) was born on 1 st February 1902 in Joplin, Missouri. When he was a young child, his parents got separated, and his father shifted to Mexico. Until the age of thirteen, he was raised by his grandmother. Afterward, Hughes went to Lincoln and started living with his mother and his foster father. The family then settled in Cleveland, Ohio. Hughes started writing poetry in Lincoln. He spent a year in Mexico after passing out from the college that was followed by a year at the University of Columbia in New York City.

He also had some meek jobs during this time like launder, assistant cook, and busboy. Working as a seaman, he also traveled to Europe and Africa. He shifted to Washington, D.C., in November 1924. In 1926, Hughes published his first book of poetry The Weary Blue in the Alfred A. Knopf publishers. He graduated from Lincoln University, Pennsylvania, in three years. His first novel, Not Without Laughter , received the Harmon gold medal for literature in 1930.

The primary influencers of Hughes included Carl Sandburg, Walt Whitman, and Paul Lawrence Dunbar. Hughes is regarded for his own insight and the colorful portrayal of the black life in America 1920s to 1960s. Hughes wrote short stories, poetry, novels, and plays; he was greatly engaged with the world of jazz and is also known as the earliest inventor of jazz poetry. He wrote a book-length poem, Montage of a Dream Deferred in 1951, influenced by jazz.

The artistic revolution of the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s is greatly shaped by both life and works of Langston Hughes. Hughes did not differentiate between the common experience of black America and the personal experience of Black America, unlike other prominent black poets of the twentieth century – Claude McKay, Countee Cullen, and Jean Toomer. He narrated the stories of people and reflected the real and actual culture of his time. He also talked about their suffering and problems, as well as their love of laughter, language, and music.

Besides a large body of poetic work, Hughes also wrote plays (eleven in number), and other countless prose work that includes a celebrated “simple: books such as Simple Speaks His Mind, Simple Stakes a Claim, Simple Takes a Wife, and Simple’s Uncle Sam.

He also edited the collection The Book of Negro Folklore and The Poetry of the Negro . He also wrote a much-admired autobiography, The Big Sea , and co-wrote the play Mule Bone with Zora Neale Hurston in 1991.

On 22 nd May 1967, Langston Hughes died of difficulties from prostate cancer, in New York City.

Langston Hughes’ Writing Style

In the introduction to Modern Black Poets: A Collection of Critical Essays published in 1973, Donald B. Gibson says from the black poets that among predecessors, Hughes is different from most of them in the sense that he wrote and addresses his poetry for people, particularly for black people. He says that the twentieth-century poets and writers turned to write about inward, obscure, and esoteric poetry for particular readers. Whereas, Hughes turned to write outward poetry, employing the theme, language, ideas, and attitude recognizable by all types of readers, even to the people who can simply read. He spread his message through poetry by employing humor in the apparently serious subject to them all across the country. His poetry has been read by more people than any other American poet.

The Essential Characteristics of Langston Hughes’ Literary Work

The following are the essential characteristics of Hughes’ work. Since he has written a larger body of poetry than prose work, the characteristics are mainly based on his poetic works.

The Use of Simple and Familiar Language

The main goal of Hughes was to spread his literary work, and particularly his poetic work, to the people belonging to any race. The black people are usually the mouthpiece of his works. Therefore, Hughes employed simple and unsophisticated language in his work. In addition to this, he uses free, unconventional, and decoded verse form in poetry. For example, the poem “I, Too, Sing America” is the best example in which the speaker expresses his dream.

“I, too, sing America.

I am the darker brother.

They send me to eat in the kitchen

When company comes,

But I laugh,

And eat well,

And grow strong .” (Lines 1 to 7)

The simple language in the poem is both rhetorical and poetic. The language is poetic because it runs into the main characteristic of poetic discourse: the language is coherent, connoted, condensed, and implicit. Similarly, the language is rhetorical because it has eleven (in the overall poem) rhetorical devices such as refrain, repetition, humor, irony, metaphor, kenning, foregrounding, image, symbol, ellipses, and hyperbole.

In his novels and short stories, Langston Hughes employs popular dialect or familiar language. For example, in the novel, Not without Laughing , Hughes employed a popular dialect with almost no ambiguities. Similarly, in poetry, Hughes also uses popular dialect. For example, in the poem “The Weary Blues”:

Thump, thump, thump, went his foot on the floor.

He played a few chords then he sang some more—

………………………………………………

And far into the night he crooned that tune.

The singer stopped playing and went to bed

While the Weary Blues echoed through his head.

He slept like a rock or a man that’s dead.

The Use of the Politically Essential Language

The literary works of Langston Hughes appear to be concerned in order to overcome and fight the factual and institutional slavery. In the Afro-American Movement of Harlem, Langston Hughes is among the frontline activists. Along with other black poets of America, he is also influenced by W.E.B. Du Bois.

The participation and the general obligation, to produce a literary and artistic expression, in connection to the existing identity of black people, in general, and of Afro-American, in particular, unite the social activists of the Harlem Renaissance.

In his poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” (published in 1921), Hughes clearly shows the experience and miseries of black slaves transported through the oceans and rivers. Basically, the poem is a nostalgia for the rivers that have developed the soul of the speaker and echoes the endurance, perseverance, life, death, victory, and wisdom. Inside the poet, a fire burns that nourishes his deep urge to write poetry and take from it a function of emancipation, justice, equity, and elevation. By using these political themes in his poetry, Langston Hughes became one of the greatest poets of all time. Hughes, like the Euphrates in the poem, bathed “when the dawn was young.”

Langston Hughes desires America to be the land of equality and freedom for all, blacks and whites. His poem, “Let America be America again,” published in 1936, advocates the liberation of American slaves.

“Let America be the dream the Dreamers dreamed

Let it be that great strong land of love

Where never kings connive nor tyrants scheme

That any man be crushed by one above.”

The Use of the Radical and Protest Tone

The tone of Langston Hughes is radical and revolutionary, along with protesting. Hughes appears to be outrageous and shocked because of the everlasting division between the different sects of people that has been entered insidiously into Harlem and North America. The physical and financial conditions of the black working class had not been improved since ages. The killings and executions in the south of America were countless, regardless of the involvement of Blacks in the Allied armies of the Great War.

In his literary works, Hughes rebels against this particular dark side of America. In his poetry and other works, he does not appear to believe in Christianity. He also revolts against the people who use religion, particularly the principles of Christianity, as a shield to hide their oppressive actions. These ideas inspire him to write the poem “Goodbye Christ.”

Langston Hughes revolts against this generally dark state of American life. He does “t trust the Christian religion. It is a revolt against the people who use Christianity as a mantle under which are hidden their oppressive actions, which inspired him to write his poem “Goodbye Christ.” In the poem, he writes,

“Listen, Christ,

You did alright in your day, I reckon —

But that day’s gone now.

They ghosted you up a swell story, too,

Called it Bible —

But it’s dead now,

The popes and the preachers’ve

Made too much money from it.”

Indeed, Hughes is not against Christ, nor he denounces his faith in Christ. However, he denounces the authority of white people over the religion, Bible, and church who use religion to exclude blacks.

Hughes got highly inspired from the 1932 trip to the Soviet Union, where every citizen – Whites, Blacks, Asians, and Europeans – was treated equally; even the blacks were treated more equally. It is because of this reason that Hughes wrote such revolutionary poems like “Good Morning Revolution” and Goodbye Christ.”

Due to such revolutionary poems and poems written in favor of Russian, Langston Hughes was accused of being a communist. However, he denies the allegation put on him before the American Senate and says that Communism only inspires him to criticize the enslavement, injustice, and insecurity encountered by the Afro-American for ages. According to Hughes, the only power able to liberate the Negros is of God; he has a firm belief in God. He believes that God acts according to his own will. In the poem “Who but Lord,” Hughes expresses his belief and hope in God.

“I said, O, Lord, if you can,

Save me from that man!

Don’t let him make a pulp out of me!

But the Lord he was not quick.

The Law raised up his stick

And beat the living hell

Out of me!”

Various Themes in Langston Hughes’ Works

The work of Langston has been greatly influenced by the life of Black Americans. In the works of Hughes, Andrew identified almost 16 themes. These themes include parental rejection, racism, miscegenation, the pride of blacks, the history of deportation, the dignity of blacks, the anger, the protest, the fight of equality, the oral tradition of Africa, social injustice, jazz, and the blues, suffering, and race. Here is a brief description of some themes explored in the works of Langston Hughes.

In the most basic sense, hybridity means mixture. The contemporary uses of the term are dispersed across several academic disciplines and are noticeable in popular culture. Basically, the term hybridity clearly demonstrates that how different cultures claim to be pure or authentic turned out to be a representation of mixture, overlap, and influence.

Langston Hughes was multicultural and mulatto. The theme of hybridity is clearly and profoundly treated in his works. For example, his poem “The Cross” is the best example of hybridity. For black and mulatto, hybridity is a burden: it is a cross to be tolerated. This poem also involves the Cross on which Jesus Christ was crucified. Just like Jesus, blacks also suffer from consistent oppression by the white people. The narrator of the poem is a mulatto, a hybrid, and is on crossroads constantly thinking about to whom he shall assimilate: white or black, or none?

The poem “Cross” is a free rhymed verse. It is written in a common and simple language. The poem is sung by the speaker “I,” who is most probably the poet himself. The theme of hybridity is hidden inside the title of the poem. The connotative meanings of the word cross are many, such as anger, bitterness, apologies, threats, crossroads, confusion, Christ’s crucifix, traversal, and crossbreed.

The goal of the speaker in the poem is to illustrate the anger, bitterness, and confusion for being and hybrid or bi-racial. In American societies, being bi-racial was the biggest problem that affects the life of bi-racial individuals and society. Such people had no identity, and they found it struggling to integrate and assimilate with society.

The tone of the first line of the poem, “My old man’s a white, old man,” is spoken in an angry tone. The speaker is giving threats to his/her parents right from the beginning of the poem; however, when the poem progresses, somewhere in the middle, the speaker apologizes and takes back his words. The lines “I’ m sorry for that evil wish” and “I take my curses back” show that the speaker is apologizing for his threats and curses that he gave earlier. At the end of the poem, the tone of the poem turns to confusion, and the speaker does not know whom to assimilate, white or black.

The poetry of Langston Hughes is everlasting. His poetry served to be a great impact not only on his own community but also on other communities around the world. The reading of the poem “Cross” is significant as it discusses the major issues the world is facing. The poem’s concerns are the undergoing conflicted, bitter, and enigmatic conditions that make people revolt against with perseverance and determination to conquer the important values such as justice, human dignity, emancipation, elevation, and equity.

Black Pride

Langston Hughes never regarded himself as white. He was proud of being hybrid and belonging to the black race. He believes in the notion the awareness of black origin at root contains the fact that to act in full awareness of being intentionally created black by God, and this makes a person equal to all human beings. Thus, a person who is conscious about his black origin shall not submit his soul before anyone and must struggle to liberate himself against all the powers that attempt to imprison him.

In the poem “Negro” published in 1922, Hughes says that he is a Negro; his complexion is as dark as night, dark as the African depth. Similarly, in the poem “To the Black Beloved,” published in 1924, he addresses his beloved as his black and says that you are not beautiful, but you are lovely and surpasses the beauty.

Similarly, his novel “Not without Laughter” also deals with the black pride and depicts the ordinary life of black people in simple language.

The History of the Transportation of the Blacks

Hughes’ novels, short stories, and several poems deal with the theme of deportation of transportation of the black slaves through the deep and wide rivers and oceans.

In the poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” published in 1921, the speaker is a black slave saying that he has known the rivers; he knows them from ancient times, even older than the “flow of human blood in the human vein.” This shows that the oppressed slaves are slaves for generations, and they have been deported to one place and other like donkeys and carts.

Crying for the black Americans, Langston Hughes, in his poem “Negro,” claims to be a singer (a black slave who has been transported) who carries his songs of sorrows “all the ways from Africa to Georgia.”

The Struggle for Equality

Langston Hughes’s writing is intensified with the issue of social equality. The major aim of Hughes in his writing is to encourage Blacks to struggle and fight for their rights for equality. He asserts that all humans are created equal; that blacks should be treated equally to white. In the poem “I Dream the World,” Hughes dreams about America, where there will be the rule of peace, love, freedom, and quality among all citizens.

In the poems, he says that he dreams about the world where no man will scorn the other man; The world full of blessing and peace; a free of any race; all sharing the bounties of the earth equally; a world where every man is free.

Since, from the beginning of the deportation of the slaves in 1562 until 1865, the African-American slaves were living in a state of misery and inhuman conditions. The year 1865 is marked as years of legal elimination of racial isolation. Hughes wrote several poems, short stories, and novels describing the miseries of black slaves in America. The poem, “Let America Be America Again,” published in 1936, echoes the miseries of black slaves.

“I am the farmer, bondsman to the soil.

I am the worker sold to the machine.

I am Negro, servant to you all.

I am the people, humble, hungry, mean—

Hungry yet today despite the dream.

Beaten yet today—O, Pioneers!

I am the man who never got ahead,

The poorest worker bartered through the years.”

The Use of the Jazz and the Blues

Music with strong rhythms is known as jazz. The music was originally created by African-American Musicians. Likewise, Blues are slow and sad music with strong rhythms. It was also developed by the musicians of African American living in the southern U.S. The blues is the style that illustrates the ill-being and originates from the songs held by blacks during their works.

Langston Hughes also employed the two styles of African American music. He would spend nights in clubs to listen to jazz music. Certainly, he was not seduced by the song; nonetheless, he was a radical follower of Black Consciousness. The only artistic form of the Black slaves was the jazz and the blues, and Hughes loved it the most.

The desire to assimilate and accept the white culture is choked by the two forms of blacks’ music, and Hughes rather celebrated the blacks’ only inheritance and creativity of art. In his book “The Negro and the Racial Mountain” that jazz for him is one of the inherent expressions of the life of Negros in America; It is the everlasting drum (tom-tom) beating in the hearts of Negros; it is the tom-tom of upheaval against the disillusionment in the world of white people; it is the tom-tom of laughter and joy, and pains absorbed in smiles.

Works Of Langston Hughes

- Mother to Son

- The Weary Blues

Langston Hughes

- Born February 1 , 1902 · Joplin, Missouri, USA

- Died May 22 , 1967 · New York City, New York, USA (lung cancer)

- Birth name James Mercer Langston Hughes

- Height 5′ 4″ (1.63 m)

- The son of teacher Carrie Langston and James Nathaniel Hughes, James Mercer "Langston" Hughes was born in Joplin, Missouri. His father abandoned the family and left for Cuba, then Mexico, due to enduring racism in the United States. Young Langston was left to be raised by his grandmother in Lawrence, Kansas. After her death, he went to live with family friends. Due to an unstable early life, his childhood was not a happy one but it heavily influenced the poet he would become. Later, he lived again with his mother--who had remarried--in Lincoln, Illinois, and eventually in Cleveland, Ohio. During high school he wrote for the school newspaper, edited the yearbook and began to write short stories, poetry, and dramatic plays. His first piece of jazz poetry, "When Sue Wears Red," was written during his high school years. Hughes was influenced by American poets Paul Laurence Dunbar , Carl Sandburg and Walt Whitman . He also briefly lived in Mexico with his father, who did not support his son's desire to be a writer. Langston studied engineering at Columbia University for a year (1921-22), eventually leaving because of racial prejudice at the school as well as his growing desire to return to Harlem and write poetry. Hughes worked various odd jobs, including a brief tenure as a crewman aboard the SS Malone in 1923, spending six months traveling to West Africa and Europe. In Europe he stayed for a while in Paris, becoming part of the black American expatriate community. In November 1924 he returned to the US to live with his mother in Washington, DC. While working as a busboy at a restaurant, Hughes tucked a few of his poems under the dinner plate of then-reigning poet Vachel Lindsay. Lindsay shared the poems during his reading that night, and in the morning Hughes was crowned Lindsay's new discovery, the "busboy poet." The following year Hughes enrolled at historically black Lincoln University, where he became a member of the Omega Psi Phi Fraternity and befriended classmate Thurgood Marshall . Hughes received a B.A. in 1929 and a Litt.D. in 1943. Except for travels to the Caribbean and West Indies, Harlem was Hughes' primary home for the rest of his life. Hughes achieved fame as a literary luminary during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s. In 1930 his first novel, "Not Without Laughter", won the Harmon gold medal for literature. Hughes was particularly known for his insightful, colorful portrayals of black life in America from the 1920s through the 1960s. His work was also known for his engagement with the world of jazz and the influence it had on his writing, as in "Montage of a Dream Deferred." His life and work were enormously important in shaping the artistic contributions of the Harlem Renaissance. Unlike other notable black poets of the period, Hughes refused to differentiate between his personal experiences and the common experience of black America. He told stories of people in ways that reflected their actual culture, including their suffering and their love of music, laughter and language itself. In addition to leaving us a large body of poetic work, Hughes wrote 11 plays and countless works of prose, including the well-known "Simple" books: "Simple Speaks His Mind," "Simple Stakes a Claim," "Simple Takes a Wife," and "Simple's Uncle Sam." He edited numerous poetry anthologies, wrote an acclaimed autobiography ("The Big Sea"), and co-wrote the play "Mule Bone" with Zora Neale Hurston . In 1967 Hughes died from complications following abdominal surgery, related to prostate cancer, at the age of 65. His ashes are interred beneath the foyer floor of the Arthur Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem. The design on the floor medallion reads, "My soul has grown deep like the rivers." - IMDb Mini Biography By: A. Nonymous

- Pictured on a USA 34¢ commemorative postage stamp in the Black Heritage series, issued 1 February 2002.

- Moved with his family to Cleveland, Ohio when he was 14.

- Wrote at Cleveland's Karamu House theatre, where many of his plays had their premiere.

- I'm laughing to keep from dying.

- Hold fast to dreams, for if dreams die, life is a broken bird that cannot fly.

Contribute to this page

- Learn more about contributing

More from this person

- View agent, publicist, legal and company contact details on IMDbPro

More to explore

Recently viewed

10 Essential Langston Hughes Poems, Including “Harlem” and “I, Too”

Langston Hughes’ poetry continues to capture the heart of America with its lyrical realism and everyday subject matter.

We may earn commission from links on this page, but we only recommend products we back.

The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes

His writing career began the year after he graduated from high school with the 1921 poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers.” His first book of poetry, The Weary Blues , followed in 1926. Throughout his work, Hughes portrayed working-class African Americans in a range of common experiences, both positive and negative. The New York City transplant was among the first poets to adapt jazz rhythms and dialect on the page. So groundbreaking was his work that Hughes wasn’t convinced he could earn a living as a writer until 1930, ultimately becoming one of the first Black Americans to do so.

Some of his most famous poems include “I, Too,” “Dreams,” and “Harlem,” which influenced playwright Lorraine Hansberry and civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr. , among many others. Beyond poetry, Hughes wrote novels like 1930’s Not Without Laughter , short stories, the autobiographies The Big Sea (1940) and I Wonder as I Wander (1956) , and plays like Mulatto . He even worked as a war correspondent during the Spanish Civil War in 1937 for several American newspapers and as a columnist for the Chicago Defender .

In 1967, the well-traveled writer died of cancer in his mid-60s, yet his legacy has endured. His brownstone home in Harlem became a historic landmark in 1982, schools bear his name, and most of all, his poetry still resonates. Here are 10 essential poems by Langston Hughes that capture of the heart of America.

“The Negro Speaks of Rivers” (1921)

Written when he was 17 years old on a train to Mexico City to see his father, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” was Hughes’ first published poem. It appeared in the June 1921 issue of the NAACP magazine The Crisis and received critical acclaim. The opening lines show a soul deeper than his age: “I’ve known rivers / I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins / My soul has grown deep like the rivers.” The style honors that of his poetic influences Walt Whitman and Carl Sandburg, as well as the voice of African American spirituals.

“Mother to Son” (1922)

With recitations from notable figures such as Martin Luther King Jr. and actor Viola Davis , “Mother to Son” was published in the December 1922 issue of The Crisis . The 20-line poem traces a mother’s words to her child about their difficult life journey using the analogy of stairs with “tacks” and “splinters” in it. But ultimately she encourages her son to forge ahead, as she leads by example: “So boy, don’t you turn back / Don’t you set down on the steps / ’Cause you finds it’s kinder hard / Don’t you fall now / For I’se still goin’, honey / I’se still climbin’ / And life for me ain’t been no crystal stair.”

“Dreams” (1922)

One of several Hughes poems about dreams and fittingly titled, this 1922 poem appeared in World Tomorrow . “Dreams,” an eight-line poem, remains a popular inspirational quote. It partially reads: “Hold fast to dreams / For if dreams die / Life is a broken-winged bird / That cannot fly.”

“The Weary Blues” (1925)

The weary blues by langston hughes.

“The Weary Blues” follows an African American pianist playing in Harlem on Lenox Avenue. It starts off sounding like he’s completely carefree but ends: “The stars went out and so did the moon / The singer stopped playing and went to bed / While the Weary Blues echoed through his head / He slept like a rock or a man that’s dead.”

After it won a contest in Opportunity magazine, Hughes called it his “lucky poem.” Sure enough, the next year, his first poetry collection was published by Knopf with the same title. Hughes was 24.

“Po’ Boy Blues” (1926)

As one of four Hughes poems that appeared in the November 1926 issue of Poetry Magazine , as well as his collection The Weary Blues , this poem feels music-like with its stanza and rhymes. The final verse reads: “Weary, weary / Weary early in de morn. / Weary, weary / Early, early in de morn. / I’s so wear / I wish I’d never been born.”

“Let America Be America Again” (1936)

First published in the July 1936 issue of Esquire magazine , “Let America Be America Again” highlights how class plays such a crucial role in the ability to realize the promises of the American dream. The three opening stanzas are each followed by a parenthetical representing the cast-off realities for the lower class, such as: “Let America be America again / Let it be the dream it used to be / Let it be the pioneer on the plain / Seeking a home where he himself is free / (America never was America to me.)”

“Life is Fine” (1949)

Perseverance pushes through all the odds—even suicide attempts—in “Life is Fine.” Broken into three sections, the first part talks about jumping into a cold river: “If that water hadn’t a-been so cold / I might’ve sunk and died.” And the second about going to the top of a 16-floor building: “If it hadn’t a-been so high/ I might’ve jumped and died.” But in the third section, it says, “But for livin’ I was born” before ending with “Life is fine! / Fine as wine! / Life is fine!”

“I, Too” (1945)

In “I, Too,” Hughes addresses segregation head-on: “I am the darker brother / They send me to eat in the kitchen / When company comes.” Despite being hidden in the back, he continues to “laugh,” “eat well,” and “grow strong.” The subject looks to a future of equality, emphatically declaring “I, too, am America.”

“Harlem” (1951)

Perhaps his most influential poem, “Harlem” starts with the line “What happens to a dream deferred? / Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun?” The poem digs into the dichotomy of the idea of the American dream juxtaposed with the reality of being in a marginalized community. Hughes’ words inspired the title of Lorraine Hansberry ’s 1959 play A Raisin in the Sun about a struggling Black family, and Martin Luther King Jr. referenced it in a number of his sermons and speeches.

“Harlem” was actually conceived as part of a book-length poem, Montage o f Dream Deferred . With more than 90 poems strung together in a musical beat, the full volume paints a full picture of life in Harlem during the Jim Crow era , most questioned in this poem’s final line, “Or does it explode?”

“Brotherly Love” (1956)