Office of Undergraduate Research

- Office of Undergraduate Research FAQ's

- URSA Engage

- Resources for Students

- Resources for Faculty

- Engaging in Research

- Presenting Your Research

- Earn Money by Participating in Research Studies

- Transcript Notation

- Student Publications

How to take Research Notes

How to take research notes.

Your research notebook is an important piece of information useful for future projects and presentations. Maintaining organized and legible notes allows your research notebook to be a valuable resource to you and your research group. It allows others and yourself to replicate experiments, and it also serves as a useful troubleshooting tool. Besides it being an important part of the research process, taking detailed notes of your research will help you stay organized and allow you to easily review your work.

Here are some common reasons to maintain organized notes:

- Keeps a record of your goals and thoughts during your research experiments.

- Keeps a record of what worked and what didn't in your research experiments.

- Enables others to use your notes as a guide for similar procedures and techniques.

- A helpful tool to reference when writing a paper, submitting a proposal, or giving a presentation.

- Assists you in answering experimental questions.

- Useful to efficiently share experimental approaches, data, and results with others.

Before taking notes:

- Ask your research professor what note-taking method they recommend or prefer.

- Consider what type of media you'll be using to take notes.

- Once you have decided on how you'll be taking notes, be sure to keep all of your notes in one place to remain organized.

- Plan on taking notes regularly (meetings, important dates, procedures, journal/manuscript revisions, etc.).

- This is useful when applying to programs or internships that ask about your research experience.

Note Taking Tips:

Taking notes by hand:.

- Research notebooks don’t belong to you so make sure your notes are legible for others.

- Use post-it notes or tabs to flag important sections.

- Start sorting your notes early so that you don't become backed up and disorganized.

- Only write with a pen as pencils aren’t permanent & sharpies can bleed through.

- Make it a habit to write in your notebook and not directly on sticky notes or paper towels. Rewriting notes can waste time and sometimes lead to inaccurate data or results.

Taking Notes Electronically

- Make sure your device is charged and backed up to store data.

- Invest in note-taking apps or E-Ink tablets

- Create shortcuts to your folders so you have easier access

- Create outlines.

- Keep your notes short and legible.

Note Taking Tips Continued:

Things to avoid.

- Avoid using pencils or markers that may bleed through.

- Avoid erasing entries. Instead, draw a straight line through any mistakes and write the date next to the crossed-out information.

- Avoid writing in cursive.

- Avoid delaying your entries so you don’t fall behind and forget information.

Formatting Tips

- Use bullet points to condense your notes to make them simpler to access or color-code them.

- Tracking your failures and mistakes can improve your work in the future.

- If possible, take notes as you’re experimenting or make time at the end of each workday to get it done.

- Record the date at the start of every day, including all dates spent on research.

Types of media to use when taking notes:

Traditional paper notebook.

- Pros: Able to take quick notes, convenient access to notes, cheaper option

- Cons: Requires a table of contents or tabs as it is not easily searchable, can get damaged easily, needs to be scanned if making a digital copy

Electronic notebook

- Apple Notes

- Pros: Easily searchable, note-taking apps available, easy to edit & customize

- Cons: Can be difficult to find notes if they are unorganized, not as easy to take quick notes, can be a more expensive option

Combination of both

Contact info.

618 Kerr Administration Building Corvallis, OR 97331

541-737-5105

13.5 Research Process: Making Notes, Synthesizing Information, and Keeping a Research Log

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Employ the methods and technologies commonly used for research and communication within various fields.

- Practice and apply strategies such as interpretation, synthesis, response, and critique to compose texts that integrate the writer’s ideas with those from appropriate sources.

- Analyze and make informed decisions about intellectual property based on the concepts that motivate them.

- Apply citation conventions systematically.

As you conduct research, you will work with a range of “texts” in various forms, including sources and documents from online databases as well as images, audio, and video files from the Internet. You may also work with archival materials and with transcribed and analyzed primary data. Additionally, you will be taking notes and recording quotations from secondary sources as you find materials that shape your understanding of your topic and, at the same time, provide you with facts and perspectives. You also may download articles as PDFs that you then annotate. Like many other students, you may find it challenging to keep so much material organized, accessible, and easy to work with while you write a major research paper. As it does for many of those students, a research log for your ideas and sources will help you keep track of the scope, purpose, and possibilities of any research project.

A research log is essentially a journal in which you collect information, ask questions, and monitor the results. Even if you are completing the annotated bibliography for Writing Process: Informing and Analyzing , keeping a research log is an effective organizational tool. Like Lily Tran’s research log entry, most entries have three parts: a part for notes on secondary sources, a part for connections to the thesis or main points, and a part for your own notes or questions. Record source notes by date, and allow room to add cross-references to other entries.

Summary of Assignment: Research Log

Your assignment is to create a research log similar to the student model. You will use it for the argumentative research project assigned in Writing Process: Integrating Research to record all secondary source information: your notes, complete publication data, relation to thesis, and other information as indicated in the right-hand column of the sample entry.

Another Lens. A somewhat different approach to maintaining a research log is to customize it to your needs or preferences. You can apply shading or color coding to headers, rows, and/or columns in the three-column format (for colors and shading). Or you can add columns to accommodate more information, analysis, synthesis, or commentary, formatting them as you wish. Consider adding a column for questions only or one for connections to other sources. Finally, consider a different visual format , such as one without columns. Another possibility is to record some of your comments and questions so that you have an aural rather than a written record of these.

Writing Center

At this point, or at any other point during the research and writing process, you may find that your school’s writing center can provide extensive assistance. If you are unfamiliar with the writing center, now is a good time to pay your first visit. Writing centers provide free peer tutoring for all types and phases of writing. Discussing your research with a trained writing center tutor can help you clarify, analyze, and connect ideas as well as provide feedback on works in progress.

Quick Launch: Beginning Questions

You may begin your research log with some open pages in which you freewrite, exploring answers to the following questions. Although you generally would do this at the beginning, it is a process to which you likely will return as you find more information about your topic and as your focus changes, as it may during the course of your research.

- What information have I found so far?

- What do I still need to find?

- Where am I most likely to find it?

These are beginning questions. Like Lily Tran, however, you will come across general questions or issues that a quick note or freewrite may help you resolve. The key to this section is to revisit it regularly. Written answers to these and other self-generated questions in your log clarify your tasks as you go along, helping you articulate ideas and examine supporting evidence critically. As you move further into the process, consider answering the following questions in your freewrite:

- What evidence looks as though it best supports my thesis?

- What evidence challenges my working thesis?

- How is my thesis changing from where it started?

Creating the Research Log

As you gather source material for your argumentative research paper, keep in mind that the research is intended to support original thinking. That is, you are not writing an informational report in which you simply supply facts to readers. Instead, you are writing to support a thesis that shows original thinking, and you are collecting and incorporating research into your paper to support that thinking. Therefore, a research log, whether digital or handwritten, is a great way to keep track of your thinking as well as your notes and bibliographic information.

In the model below, Lily Tran records the correct MLA bibliographic citation for the source. Then, she records a note and includes the in-text citation here to avoid having to retrieve this information later. Perhaps most important, Tran records why she noted this information—how it supports her thesis: The human race must turn to sustainable food systems that provide healthy diets with minimal environmental impact, starting now . Finally, she makes a note to herself about an additional visual to include in the final paper to reinforce the point regarding the current pressure on food systems. And she connects the information to other information she finds, thus cross-referencing and establishing a possible synthesis. Use a format similar to that in Table 13.4 to begin your own research log.

Types of Research Notes

Taking good notes will make the research process easier by enabling you to locate and remember sources and use them effectively. While some research projects requiring only a few sources may seem easily tracked, research projects requiring more than a few sources are more effectively managed when you take good bibliographic and informational notes. As you gather evidence for your argumentative research paper, follow the descriptions and the electronic model to record your notes. You can combine these with your research log, or you can use the research log for secondary sources and your own note-taking system for primary sources if a division of this kind is helpful. Either way, be sure to include all necessary information.

Bibliographic Notes

These identify the source you are using. When you locate a useful source, record the information necessary to find that source again. It is important to do this as you find each source, even before taking notes from it. If you create bibliographic notes as you go along, then you can easily arrange them in alphabetical order later to prepare the reference list required at the end of formal academic papers. If your instructor requires you to use MLA formatting for your essay, be sure to record the following information:

- Title of source

- Title of container (larger work in which source is included)

- Other contributors

- Publication date

When using MLA style with online sources, also record the following information:

- Date of original publication

- Date of access

- DOI (A DOI, or digital object identifier, is a series of digits and letters that leads to the location of an online source. Articles in journals are often assigned DOIs to ensure that the source can be located, even if the URL changes. If your source is listed with a DOI, use that instead of a URL.)

It is important to understand which documentation style your instructor will require you to use. Check the Handbook for MLA Documentation and Format and APA Documentation and Format styles . In addition, you can check the style guide information provided by the Purdue Online Writing Lab .

Informational Notes

These notes record the relevant information found in your sources. When writing your essay, you will work from these notes, so be sure they contain all the information you need from every source you intend to use. Also try to focus your notes on your research question so that their relevance is clear when you read them later. To avoid confusion, work with separate entries for each piece of information recorded. At the top of each entry, identify the source through brief bibliographic identification (author and title), and note the page numbers on which the information appears. Also helpful is to add personal notes, including ideas for possible use of the information or cross-references to other information. As noted in Writing Process: Integrating Research , you will be using a variety of formats when borrowing from sources. Below is a quick review of these formats in terms of note-taking processes. By clarifying whether you are quoting directly, paraphrasing, or summarizing during these stages, you can record information accurately and thus take steps to avoid plagiarism.

Direct Quotations, Paraphrases, and Summaries

A direct quotation is an exact duplication of the author’s words as they appear in the original source. In your notes, put quotation marks around direct quotations so that you remember these words are the author’s, not yours. One advantage of copying exact quotations is that it allows you to decide later whether to include a quotation, paraphrase, or summary. ln general, though, use direct quotations only when the author’s words are particularly lively or persuasive.

A paraphrase is a restatement of the author’s words in your own words. Paraphrase to simplify or clarify the original author’s point. In your notes, use paraphrases when you need to record details but not exact words.

A summary is a brief condensation or distillation of the main point and most important details of the original source. Write a summary in your own words, with facts and ideas accurately represented. A summary is useful when specific details in the source are unimportant or irrelevant to your research question. You may find you can summarize several paragraphs or even an entire article or chapter in just a few sentences without losing useful information. It is a good idea to note when your entry contains a summary to remind you later that it omits detailed information. See Writing Process Integrating Research for more detailed information and examples of quotations, paraphrases, and summaries and when to use them.

Other Systems for Organizing Research Logs and Digital Note-Taking

Students often become frustrated and at times overwhelmed by the quantity of materials to be managed in the research process. If this is your first time working with both primary and secondary sources, finding ways to keep all of the information in one place and well organized is essential.

Because gathering primary evidence may be a relatively new practice, this section is designed to help you navigate the process. As mentioned earlier, information gathered in fieldwork is not cataloged, organized, indexed, or shelved for your convenience. Obtaining it requires diligence, energy, and planning. Online resources can assist you with keeping a research log. Your college library may have subscriptions to tools such as Todoist or EndNote. Consult with a librarian to find out whether you have access to any of these. If not, use something like the template shown in Figure 13.8 , or another like it, as a template for creating your own research notes and organizational tool. You will need to have a record of all field research data as well as the research log for all secondary sources.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Authors: Michelle Bachelor Robinson, Maria Jerskey, featuring Toby Fulwiler

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Writing Guide with Handbook

- Publication date: Dec 21, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/13-5-research-process-making-notes-synthesizing-information-and-keeping-a-research-log

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

How to Do Research: A Step-By-Step Guide: 4a. Take Notes

- Get Started

- 1a. Select a Topic

- 1b. Develop Research Questions

- 1c. Identify Keywords

- 1d. Find Background Information

- 1e. Refine a Topic

- 2a. Search Strategies

- 2d. Articles

- 2e. Videos & Images

- 2f. Databases

- 2g. Websites

- 2h. Grey Literature

- 2i. Open Access Materials

- 3a. Evaluate Sources

- 3b. Primary vs. Secondary

- 3c. Types of Periodicals

- 4a. Take Notes

- 4b. Outline the Paper

- 4c. Incorporate Source Material

- 5a. Avoid Plagiarism

- 5b. Zotero & MyBib

- 5c. MLA Formatting

- 5d. MLA Citation Examples

- 5e. APA Formatting

- 5f. APA Citation Examples

- 5g. Annotated Bibliographies

Note Taking in Bibliographic Management Tools

We encourage students to use bibliographic citation management tools (such as Zotero, EasyBib and RefWorks) to keep track of their research citations. Each service includes a note-taking function. Find more information about citation management tools here . Whether or not you're using one of these, the tips below will help you.

Tips for Taking Notes Electronically

- Try using a bibliographic citation management tool to keep track of your sources and to take notes.

- As you add sources, put them in the format you're using (MLA, APA, Chicago, etc.).

- Group sources by publication type (i.e., book, article, website).

- Number each source within the publication type group.

- For websites, include the URL information and the date you accessed each site.

- Next to each idea, include the source number from the Works Cited file and the page number from the source. See the examples below. Note that #A5 and #B2 refer to article source 5 and book source 2 from the Works Cited file.

#A5 p.35: 76.69% of the hyperlinks selected from homepage are for articles and the catalog #B2 p.76: online library guides evolved from the paper pathfinders of the 1960s

- When done taking notes, assign keywords or sub-topic headings to each idea, quote or summary.

- Use the copy and paste feature to group keywords or sub-topic ideas together.

- Back up your master list and note files frequently!

Tips for Taking Notes by Hand

- Use index cards to keep notes and track sources used in your paper.

- Include the citation (i.e., author, title, publisher, date, page numbers, etc.) in the format you're using. It will be easier to organize the sources alphabetically when creating the Works Cited page.

- Number the source cards.

- Use only one side to record a single idea, fact or quote from one source. It will be easier to rearrange them later when it comes time to organize your paper.

- Include a heading or key words at the top of the card.

- Include the Work Cited source card number.

- Include the page number where you found the information.

- Use abbreviations, acronyms, or incomplete sentences to record information to speed up the notetaking process.

- Write down only the information that answers your research questions.

- Use symbols, diagrams, charts or drawings to simplify and visualize ideas.

Forms of Notetaking

Use one of these notetaking forms to capture information:

- Summarize : Capture the main ideas of the source succinctly by restating them in your own words.

- Paraphrase : Restate the author's ideas in your own words.

- Quote : Copy the quotation exactly as it appears in the original source. Put quotation marks around the text and note the name of the person you are quoting.

Example of a Work Cited Card

Example notecard.

- << Previous: Step 4: Write

- Next: 4b. Outline the Paper >>

- Last Updated: Feb 21, 2024 11:01 AM

- URL: https://libguides.elmira.edu/research

- Writing Home

- Writing Advice Home

Taking Notes from Research Reading

- Printable PDF Version

- Fair-Use Policy

If you take notes efficiently, you can read with more understanding and also save time and frustration when you come to write your paper. These are three main principles

1. Know what kind of ideas you need to record

Focus your approach to the topic before you start detailed research. Then you will read with a purpose in mind, and you will be able to sort out relevant ideas.

- First, review the commonly known facts about your topic, and also become aware of the range of thinking and opinions on it. Review your class notes and textbook and browse in an encyclopaedia or other reference work.

- Try making a preliminary list of the subtopics you would expect to find in your reading. These will guide your attention and may come in handy as labels for notes.

- Choose a component or angle that interests you, perhaps one on which there is already some controversy. Now formulate your research question. It should allow for reasoning as well as gathering of information—not just what the proto-Iroquoians ate, for instance, but how valid the evidence is for early introduction of corn. You may even want to jot down a tentative thesis statement as a preliminary answer to your question. (See Using Thesis Statements .)

- Then you will know what to look for in your research reading: facts and theories that help answer your question, and other people’s opinions about whether specific answers are good ones.

2. Don’t write down too much

Your essay must be an expression of your own thinking, not a patchwork of borrowed ideas. Plan therefore to invest your research time in understanding your sources and integrating them into your own thinking. Your note cards or note sheets will record only ideas that are relevant to your focus on the topic; and they will mostly summarize rather than quote.

- Copy out exact words only when the ideas are memorably phrased or surprisingly expressed—when you might use them as actual quotations in your essay.

- Otherwise, compress ideas in your own words . Paraphrasing word by word is a waste of time. Choose the most important ideas and write them down as labels or headings. Then fill in with a few subpoints that explain or exemplify.

- Don’t depend on underlining and highlighting. Find your own words for notes in the margin (or on “sticky” notes).

3. Label your notes intelligently

Whether you use cards or pages for note-taking, take notes in a way that allows for later use.

- Save bother later by developing the habit of recording bibliographic information in a master list when you begin looking at each source (don’t forget to note book and journal information on photocopies). Then you can quickly identify each note by the author’s name and page number; when you refer to sources in the essay you can fill in details of publication easily from your master list. Keep a format guide handy (see Documentation Formats ).

- Try as far as possible to put notes on separate cards or sheets. This will let you label the topic of each note. Not only will that keep your notetaking focussed, but it will also allow for grouping and synthesizing of ideas later. It is especially satisfying to shuffle notes and see how the conjunctions create new ideas—yours.

- Leave lots of space in your notes for comments of your own—questions and reactions as you read, second thoughts and cross-references when you look back at what you’ve written. These comments can become a virtual first draft of your paper.

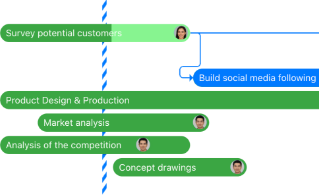

Finally see how to stop getting stuck in a project management tool

20 min. personalized consultation with a project management expert

Smart Note-Taking for Research Paper Writing

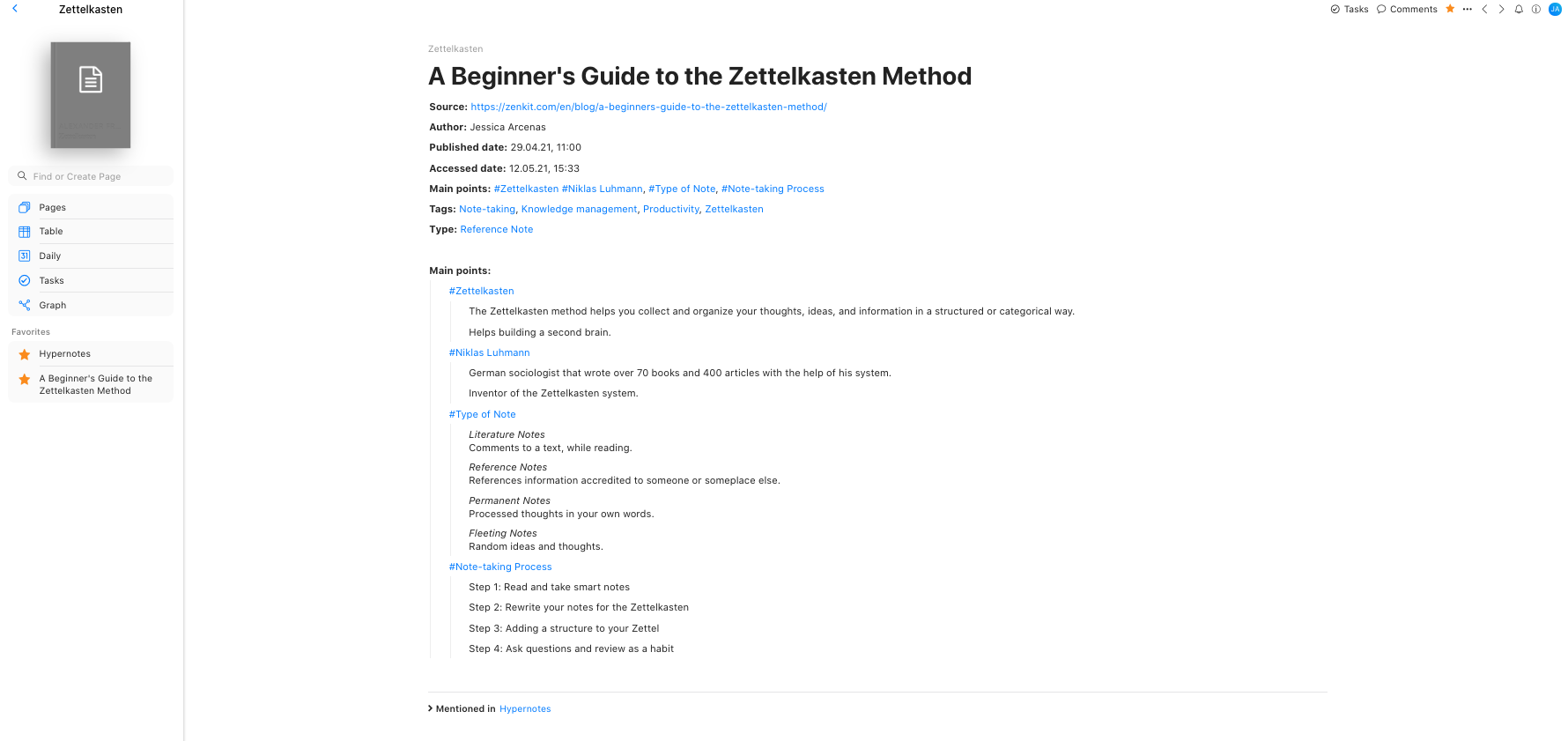

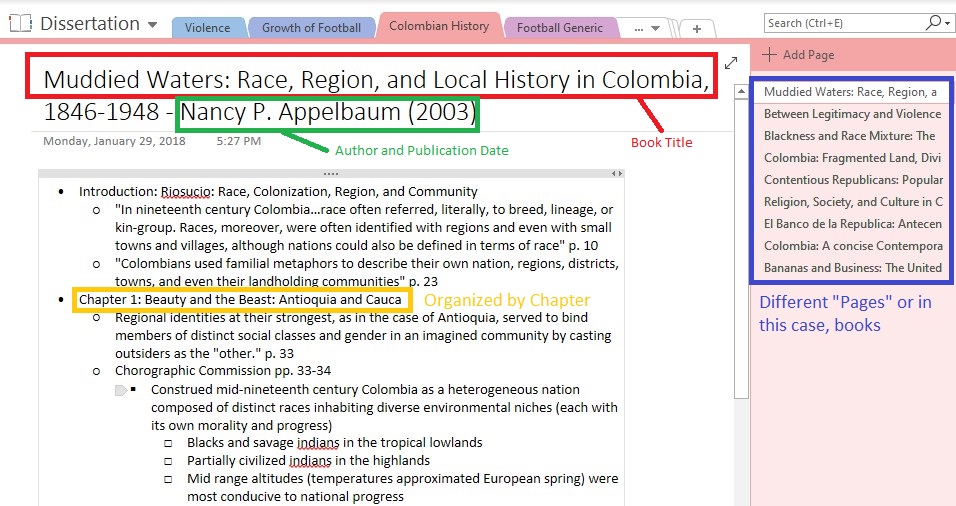

How to organize research notes using the Zettelkasten Method when writing academic papers

With plenty of note-taking tips and apps available, online and in paper form, it’s become extremely easy to take note of information, ideas, or thoughts. As simple as it is to write down an idea or jot down a quote, the skill of academic research and writing for a thesis paper is on another level entirely. And keeping a record or an archive of all of the information you need can quickly require a very organized system.

The use of index cards seems old-fashioned considering that note-taking apps (psst! Hypernotes ) offer better functionality and are arguably more user-friendly. However, software is only there to help aid our individual workflow and thinking process. That’s why understanding and learning how to properly research, take notes and write academic papers is still a highly valuable skill.

Let’s Start Writing! But Where to Start…

Writing academic papers is a vital skill most students need to learn and practice. Academic papers are usually time-intensive pieces of written content that are a requirement throughout school or at University. Whether a topic is assigned or you have to choose your own, there’s little room for variation in how to begin.

Popular and purposeful in analyzing and evaluating the knowledge of the author as well as assessing if the learning objectives were met, research papers serve as information-packed content. Most of us may not end up working jobs in academic professions or be researchers at institutions, where writing research papers is also part of the job, but we often read such papers.

Despite the fact that most research papers or dissertations aren’t often read in full, journalists, academics, and other professionals regularly use academic papers as a basis for further literary publications or blog articles. The standard of academic papers ensures the validity of the information and gives the content authority.

There’s no-nonsense in research papers. To make sure to write convincing and correct content, the research stage is extremely important. And, naturally, when doing any kind of research, we take notes.

Why Take Notes?

There are particular standards defined for writing academic papers . In order to meet these standards, a specific amount of background information and researched literature is required. Taking notes helps keep track of read/consumed literary material as well as keeps a file of any information that may be of importance to the topic.

The aim of writing isn’t merely to advertise fully formed opinions, but also serves the purpose of developing opinions worth sharing in the first place.

What is Note-Taking?

Note-taking (sometimes written as notetaking or note-taking ) is the practice of recording information from different sources and platforms. For academic writing, note-taking is the process of obtaining and compiling information that answers and supports the research paper’s questions and topic. Notes can be in one of three forms: summary, paraphrase, or direct quotation.

Note-taking is an excellent process useful for anyone to turn individual thoughts and information into organized ideas ready to be communicated through writing. Notes are, however, only as valuable as the context. Since notes are also a byproduct of the information we consume daily, it’s important to categorize information, develop connections, and establish relationships between pieces of information.

What Type of Notes Can I Take?

- Explanation of complex theories

- Background information on events or persons of interest

- Definitions of terms

- Quotations of significant value

- Illustrations or graphics

Note-Taking 101

Taking notes or doing research for academic papers shouldn’t be that difficult, considering we take notes all the time. Wrong. Note-taking for research papers isn’t the same as quickly noting down an interesting slogan or cool quote from a video, putting it on a sticky note, and slapping it onto your bedroom or office wall.

Note-taking for research papers requires focus and careful deliberation of which information is important to note down, keep on file, or use and reference in your own writing. Depending on the topic and requirements of your research paper from your University or institution, your notes might include explanations of complex theories, definitions, quotations, and graphics.

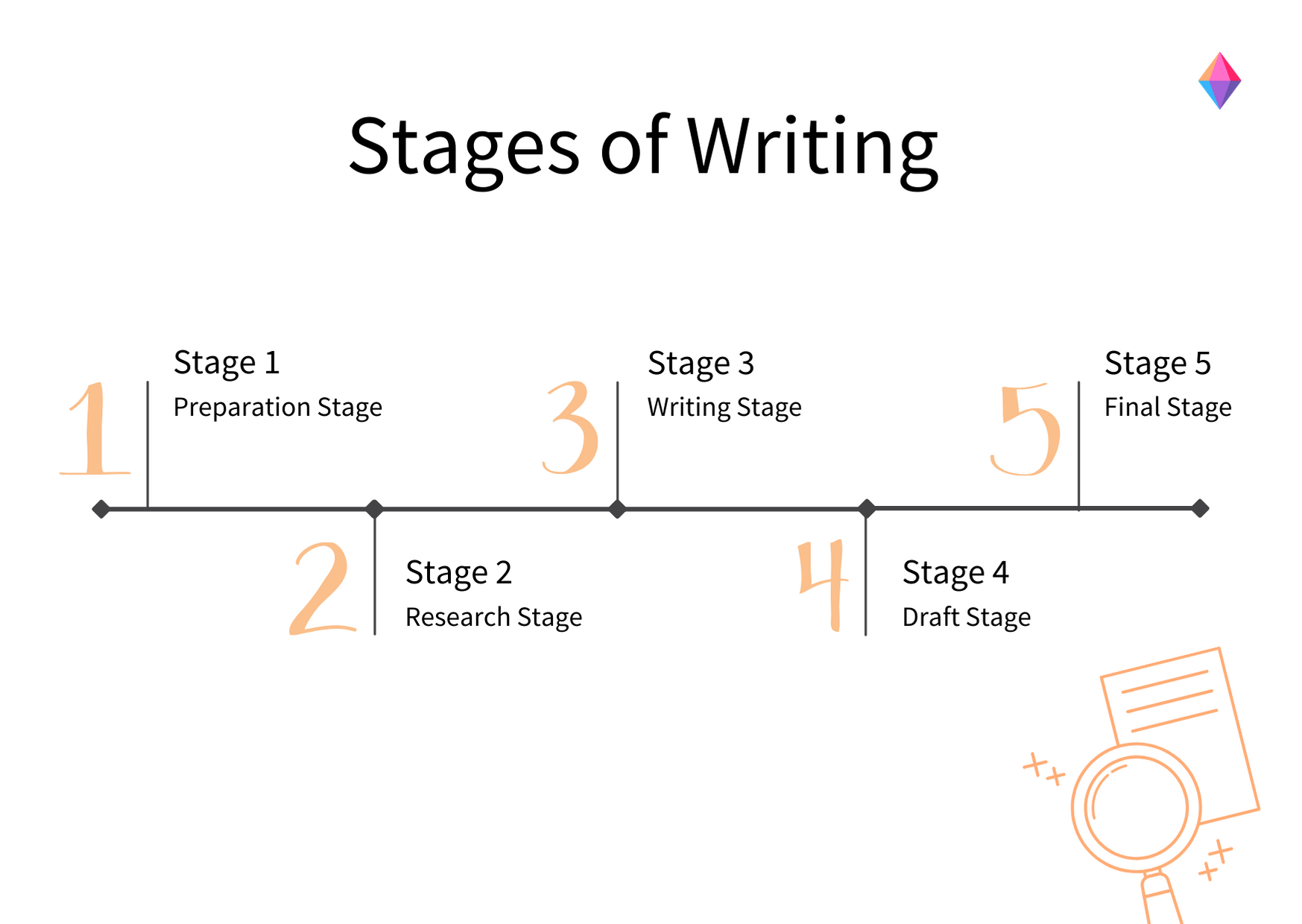

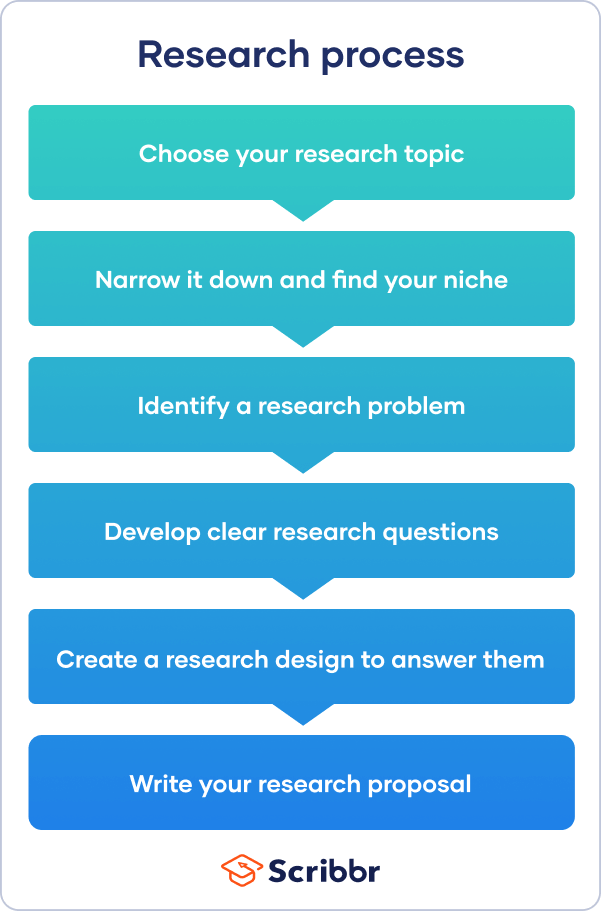

Stages of Research Paper Writing

1. Preparation Stage

Before you start, it’s recommended to draft a plan or an outline of how you wish to begin preparing to write your research paper. Make note of the topic you will be writing on, as well as the stylistic and literary requirements for your paper.

2. Research Stage

In the research stage, finding good and useful literary material for background knowledge is vital. To find particular publications on a topic, you can use Google Scholar or access literary databases and institutions made available to you through your school, university, or institution.

Make sure to write down the source location of the literary material you find. Always include the reference title, author, page number, and source destination. This saves you time when formatting your paper in the later stages and helps keep the information you collect organized and referenceable.

In the worst-case scenario, you’ll have to do a backward search to find the source of a quote you wrote down without reference to the original literary material.

3. Writing Stage

When writing, an outline or paper structure is helpful to visually break up the piece into sections. Once you have defined the sections, you can begin writing and referencing the information you have collected in the research stage.

Clearly mark which text pieces and information where you relied on background knowledge, which texts are directly sourced, and which information you summarized or have written in your own words. This is where your paper starts to take shape.

4. Draft Stage

After organizing all of your collected notes and starting to write your paper, you are already in the draft stage. In the draft stage, the background information collected and the text written in your own words come together. Every piece of information is structured by the subtopics and sections you defined in the previous stages.

5. Final Stage

Success! Well… almost! In the final stage, you look over your whole paper and check for consistency and any irrelevancies. Read through the entire paper for clarity, grammatical errors , and peace of mind that you have included everything important.

Make sure you use the correct formatting and referencing method requested by your University or institution for research papers. Don’t forget to save it and then send the paper on its way.

Best Practice Note-Taking Tips

- Find relevant and authoritative literary material through the search bar of literary databases and institutions.

- Practice citation repeatedly! Always keep a record of the reference book title, author, page number, and source location. At best, format the citation in the necessary format from the beginning.

- Organize your notes according to topic or reference to easily find the information again when in the writing stage. Work invested in the early stages eases the writing and editing process of the later stages.

- Summarize research notes and write in your own words as much as possible. Cite direct quotes and clearly mark copied text in your notes to avoid plagiarism.

Take Smart Notes

Taking smart notes isn’t as difficult as it seems. It’s simply a matter of principle, defined structure, and consistency. Whether you opt for a paper-based system or use a digital tool to write and organize your notes depends solely on your individual personality, needs, and workflow.

With various productivity apps promoting diverse techniques, a good note-taking system to take smart notes is the Zettelkasten Method . Invented by Niklas Luhmann, a german sociologist and researcher, the Zettelkasten Method is known as the smart note-taking method that popularized personalized knowledge management.

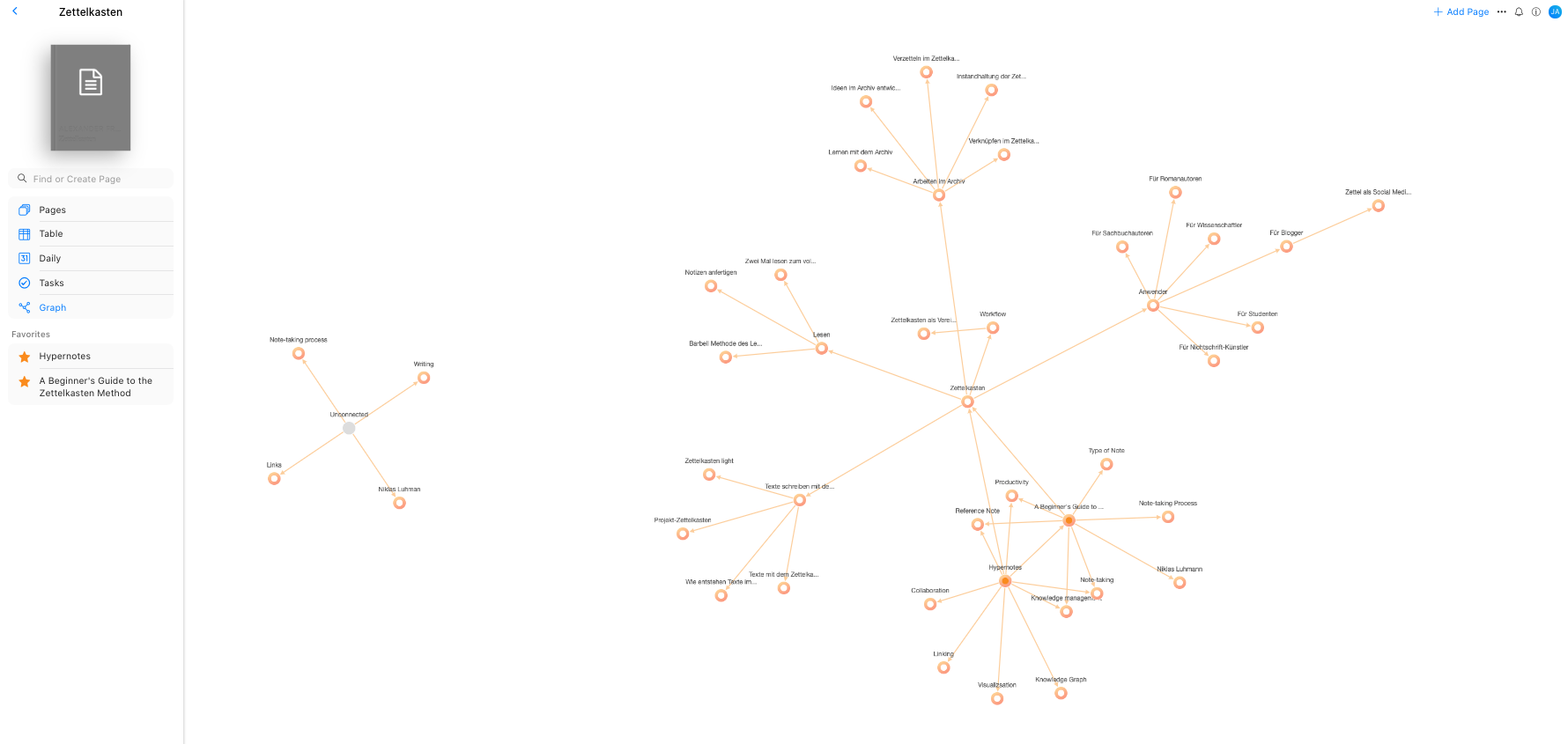

As a strategic process for thinking and writing, the Zettelkasten Method helps you organize your knowledge while working, studying, or researching. Directly translated as a ‘note box’, Zettelkasten is simply a framework to help organize your ideas, thoughts, and information by relating pieces of knowledge and connecting pieces of information to each other.

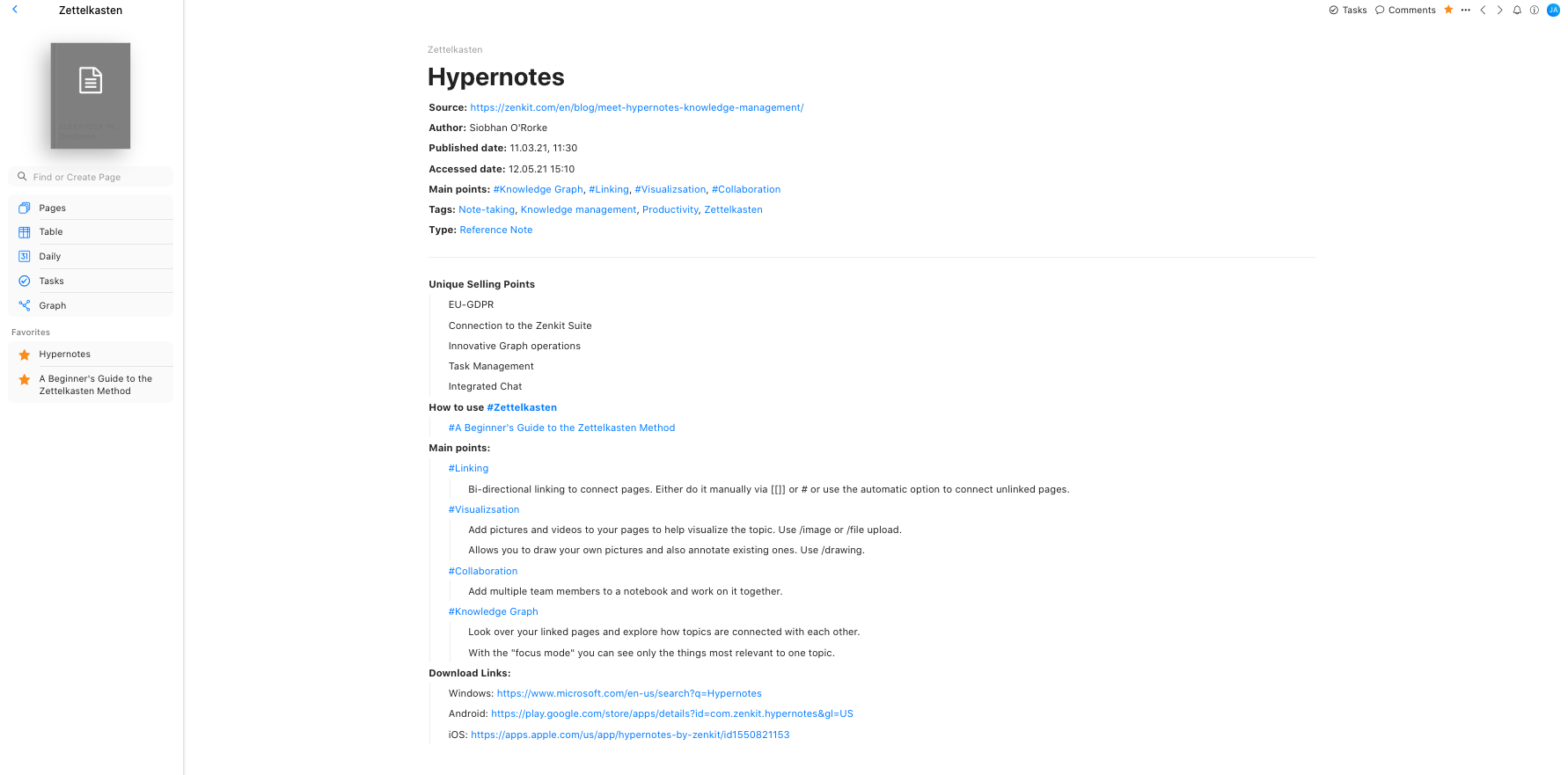

Hypernotes is a note-taking app that can be used as a software-based Zettelkasten, with integrated features to make smart note-taking so much easier, such as auto-connecting related notes, and syncing to multiple devices. In each notebook, you can create an archive of your thoughts, ideas, and information.

Using the tag system to connect like-minded ideas and information to one another and letting Hypernotes do its thing with bi-directional linking, you’ll soon create a web of knowledge about anything you’ve ever taken note of. This feature is extremely helpful to navigate through the enormous amounts of information you’ve written down. Another benefit is that it assists you in categorizing and making connections between your ideas, thoughts, and saved information in a single notebook. Navigate through your notes, ideas, and knowledge easily.

Ready, Set, Go!

Writing academic papers is no simple task. Depending on the requirements, resources available, and your personal research and writing style, techniques, apps, or practice help keep you organized and increase your productivity.

Whether you use a particular note-taking app like Hypernotes for your research paper writing or opt for a paper-based system, make sure you follow a particular structure. Repeat the steps that help you find the information you need quicker and allow you to reproduce or create knowledge naturally.

Images from NeONBRAND , hana_k and Surface via Unsplash

A well-written piece is made up of authoritative sources and uses the art of connecting ideas, thoughts, and information together. Good luck to all students and professionals working on research paper writing! We hope these tips help you in organizing the information and aid your workflow in your writing process.

Cheers, Jessica and the Zenkit Team

FREE 20 MIN. CONSULTATION WITH A PROJECT MANAGEMENT EXPERT

Wanna see how to simplify your workflow with Zenkit in less than a day?

- digital note app

- how to smart notes

- how to take notes

- hypernotes note app

- hypernotes take notes

- note archive software

- note taking app for students

- note taking tips

- note-taking

- note-taking app

- organize research paper

- reading notes

- research note taking

- research notes

- research paper writing

- smart notes

- taking notes zettelkasten method

- thesis writing

- writing a research paper

- writing a thesis paper

- zettelkasten method

More from Karen Bradford

10 Ways to Remember What You Study

More from Kelly Moser

How Hot Desking Elevates the Office Environment in 2024

More from Chris Harley

8 Productivity Tools for Successful Content Marketing

2 thoughts on “ Smart Note-Taking for Research Paper Writing ”

Thanks for sending really an exquisite text.

Great article thank you for sharing!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Zenkit Comment Policy

At Zenkit, we strive to post helpful, informative, and timely content. We want you to feel welcome to comment with your own thoughts, feedback, and critiques, however we do not welcome inappropriate or rude comments. We reserve the right to delete comments or ban users from commenting as needed to keep our comments section relevant and respectful.

What we encourage:

- Smart, informed, and helpful comments that contribute to the topic. Funny commentary is also thoroughly encouraged.

- Constructive criticism, either of the article itself or the ideas contained in it.

- Found technical issues with the site? Send an email to [email protected] and specify the issue and what kind of device, operating system, and OS version you are using.

- Noticed spam or inappropriate behaviour that we haven’t yet sorted out? Flag the comment or report the offending post to [email protected] .

What we’d rather you avoid:

Rude or inappropriate comments.

We welcome heated discourse, and we’re aware that some topics cover things people feel passionately about. We encourage you to voice your opinions, however in order for discussions to remain constructive, we ask that you remember to criticize ideas, not people.

Please avoid:

- name-calling

- ad hominem attacks

- responding to a post’s tone instead of its actual content

- knee-jerk contradiction

Comments that we find to be hateful, inflammatory, threatening, or harassing may be removed. This includes racist, gendered, ableist, ageist, homophobic, and transphobic slurs and language of any sort. If you don’t have something nice to say about another user, don't say it. Treat others the way you’d like to be treated.

Trolling or generally unkind behaviour

If you’re just here to wreak havoc and have some fun, and you’re not contributing meaningfully to the discussions, we will take actions to remove you from the conversation. Please also avoid flagging or downvoting other users’ comments just because you disagree with them.

Every interpretation of spamming is prohibited. This means no unauthorized promotion of your own brand, product, or blog, unauthorized advertisements, links to any kind of online gambling, malicious sites, or otherwise inappropriate material.

Comments that are irrelevant or that show you haven’t read the article

We know that some comments can veer into different topics at times, but remain related to the original topic. Be polite, and please avoid promoting off-topic commentary. Ditto avoid complaining we failed to mention certain topics when they were clearly covered in the piece. Make sure you read through the whole piece before saying your piece!

Breaches of privacy

This should really go without saying, but please do not post personal information that may be used by others for malicious purposes. Please also do not impersonate authors of this blog, or other commenters (that’s just weird).

How to Take Notes

How to Use Sources Effectively

Most articles in periodicals and some of the book sources you use, especially those from the children’s room at the library, are probably short enough that you can read them from beginning to end in a reasonable amount of time. Others, however, may be too long for you to do that, and some are likely to cover much more than just your topic. Use the table of contents and the index in a longer book to find the parts of the book that contain information on your topic. When you turn to those parts, skim them to make sure they contain information you can use. Feel free to skip parts that don’t relate to your questions, so you can get the information you need as quickly and efficiently as possible.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code, methods for note taking.

Don’t—start reading a book and writing down information on a sheet of notebook paper. If you make this mistake, you’ll end up with a lot of disorganized scribbling that may be practically useless when you’re ready to outline your research paper and write a first draft. Some students who tried this had to cut up their notes into tiny strips, spread them out on the floor, and then tape the strips back together in order to put their information in an order that made sense. Other students couldn’t even do that—without going to a photocopier first—because they had written on both sides of the paper. To avoid that kind of trouble, use the tried-and-true method students have been using for years—take notes on index cards.

Taking Notes on Index Cards

As you begin reading your sources, use either 3″ x 5″ or 4″ x 6″ index cards to write down information you might use in your paper. The first thing to remember is: Write only one idea on each card. Even if you write only a few words on one card, don’t write anything about a new idea on that card. Begin a new card instead. Also, keep all your notes for one card only on that card. It’s fine to write on both the front and back of a card, but don’t carry the same note over to a second card. If you have that much to write, you probably have more than one idea.

After you complete a note card, write the source number of the book you used in the upper left corner of the card. Below the source number, write the exact number or numbers of the pages on which you found the information. In the upper right corner, write one or two words that describe the specific subject of the card. These words are like a headline that describes the main information on the card. Be as clear as possible because you will need these headlines later.

After you finish taking notes from a source, write a check mark on your source card as a reminder that you’ve gone through that source thoroughly and written down all the important information you found there. That way, you won’t wonder later whether you should go back and read that source again.

Taking Notes on Your Computer

Another way to take notes is on your computer. In order to use this method, you have to rely completely on sources that you can take home, unless you have a laptop computer that you can take with you to the library.

If you do choose to take notes on your computer, think of each entry on your screen as one in a pack of electronic note cards. Write your notes exactly as if you were using index cards. Be sure to leave space between each note so that they don’t run together and look confusing when you’re ready to use them. You might want to insert a page break between each “note card.”

When deciding whether to use note cards or a computer, remember one thing—high-tech is not always better. Many students find low-tech index cards easier to organize and use than computer notes that have to be moved around by cutting and pasting. In the end, you’re the one who knows best how you work, so the choice is up to you.

How to Take Effective Notes

Knowing the best format for notes is important, but knowing what to write on your cards or on your computer is essential. Strong notes are the backbone of a good research paper.

Not Too Much or Too Little

When researching, you’re likely to find a lot of interesting information that you never knew before. That’s great! You can never learn too much. But for now your goal is to find information you can use in your research paper. Giving in to the temptation to take notes on every detail you find in your research can lead to a huge volume of notes—many of which you won’t use at all. This can become difficult to manage at later stages, so limit yourself to information that really belongs in your paper. If you think a piece of information might be useful but you aren’t sure, ask yourself whether it helps answer one of your research questions.

Writing too much is one pitfall; writing too little is another. Consider this scenario: You’ve been working in the library for a couple of hours, and your hand grows tired from writing. You come to a fairly complicated passage about how to tell if a dog is angry, so you say to yourself, “I don’t have to write all this down. I’ll remember.” But you won’t remember—especially after all the reading and note taking you have been doing. If you find information you know you want to use later on, get it down. If you’re too tired, take a break or take off the rest of the day and return tomorrow when you’re fresh.

To Note or Not to Note: That is the Question

What if you come across an idea or piece of information that you’ve already found in another source? Should you write it down again? You don’t want to end up with a whole stack of cards with the same information on each one. On the other hand, knowing that more than one source agrees on a particular point is helpful. Here’s the solution: Simply add the number of the new source to the note card that already has the same piece of information written on it. Take notes on both sources. In your paper, you may want to come right out and say that sources disagree on this point. You may even want to support one opinion or the other—if you think you have a strong enough argument based on facts from your research.

Paraphrasing—Not Copying

Have you ever heard the word plagiarism? It means copying someone else’s words and claiming them as your own. It’s really a kind of stealing, and there are strict rules against it.

The trouble is many students plagiarize without meaning to do so. The problem starts at the note-taking stage. As a student takes notes, he or she may simply copy the exact words from a source. The student doesn’t put quotation marks around the words to show that they are someone else’s. When it comes time to draft the paper, the student doesn’t even remember that those words were copied from a source, and the words find their way into the draft and then into the final paper. Without intending to do so, that student has plagiarized, or stolen, another person’s words.

The way to avoid plagiarism is to paraphrase, or write down ideas in your own words rather than copy them exactly. Look again at the model note cards in this chapter, and notice that the words in the notes are not the same as the words from the sources. Some of the notes are not even written in complete sentences. Writing in incomplete sentences is one way to make sure you don’t copy—and it saves you time, energy, and space. When you write a draft of your research paper, of course, you will use complete sentences.

How to Organize Your Notes

Once you’ve used all your sources and taken all your notes, what do you have? You have a stack of cards (or if you’ve taken notes on a computer, screen after screen of entries) about a lot of stuff in no particular order. Now you need to organize your notes in order to turn them into the powerful tool that helps you outline and draft your research paper. Following are some ideas on how to do this, so get your thinking skills in gear to start doing the job for your own paper.

Organizing Note Cards

The beauty of using index cards to take notes is that you can move them around until they are in the order you want. You don’t have to go through complicated cutting-and-pasting procedures, as you would on your computer, and you can lay your cards out where you can see them all at once. One word of caution—work on a surface where your cards won’t fall on the floor while you’re organizing them.

Start by sorting all your cards with the same headlines into the same piles, since all of these note cards are about the same basic idea. You don’t have to worry about keeping notes from the same sources together because each card is marked with a number identifying its source.

Next, arrange the piles of cards so that the order the ideas appear in makes sense. Experts have named six basic types of order. One—or a combination of these—may work for you:

- Chronological , or Time, Order covers events in the order in which they happened. This kind of order works best for papers that discuss historical events or tell about a person’s life.

- Spatial Order organizes your information by its place or position. This kind of order can work for papers about geography or about how to design something—a garden, for example.

- Cause and Effect discusses how one event or action leads to another. This kind of organization works well if your paper explains a scientific process or events in history.

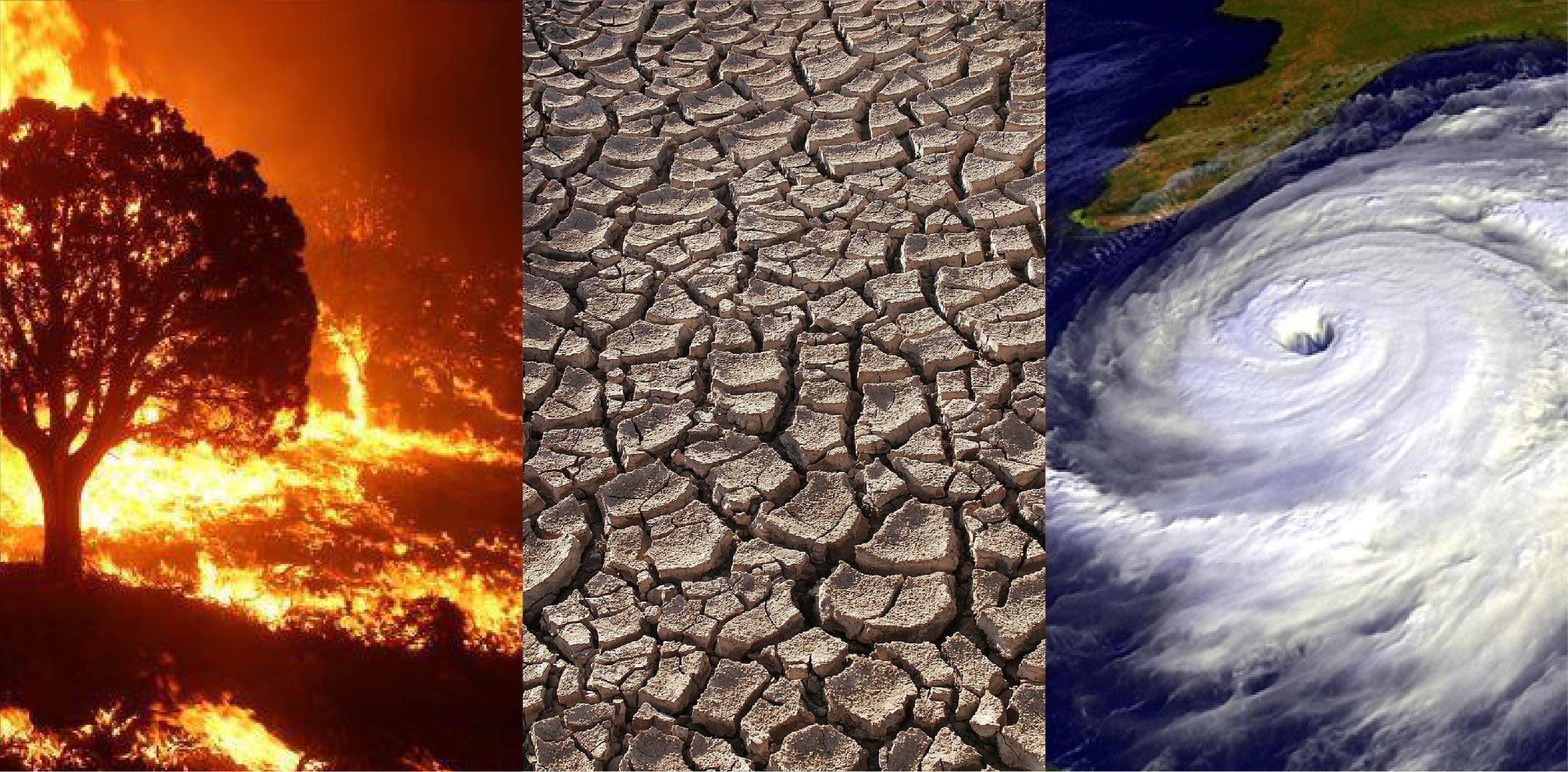

- Problem/Solution explains a problem and one or more ways in which it can be solved. You might use this type of organization for a paper about an environmental issue, such as global warming.

- Compare and Contrast discusses similarities and differences between people, things, events, or ideas.

- Order of Importance explains an idea, starting with its most important aspects first and ending with the least important aspects—or the other way around.

After you determine your basic organization, arrange your piles accordingly. You’ll end up with three main piles—one for sounds, one for facial expressions, and one for body language. Go through each pile and put the individual cards in an order that makes sense. Don’t forget that you can move your cards around, trying out different organizations, until you are satisfied that one idea flows logically into another. Use a paper clip or rubber band to hold the piles together, and then stack them in the order you choose. Put a big rubber band around the whole stack so the cards stay in order.

Organizing Notes on Your Computer

If you’ve taken notes on a computer, organize them in much the same way you would organize index cards. The difference is that you use the cut-and-paste functions on your computer rather than moving cards around. The advantage is that you end up with something that’s already typed—something you can eventually turn into an outline without having to copy anything over. The disadvantage is that you may have more trouble moving computer notes around than note cards: You can’t lay your notes out and look at them all at once, and you may get confused when trying to find where information has moved within a long file on your computer screen.

However, be sure to back up your note cards on an external storage system of your choice. In addition, print hard copies as you work. This way, you won’t lose your material if your hard drive crashes or the file develops a glitch.

Developing a Working Bibliography

When you start your research, your instructor may ask you to prepare a working bibliography listing the sources you plan to use. Your working bibliography differs from your Works Cited page in its scope: your working bibliography is much larger. Your Works Cited page will include only those sources you have actually cited in your research paper.

To prepare a working bibliography, arrange your note cards in the order required by your documentation system (such as MLA and APA) and keyboard the entries following the correct form. If you have created your bibliography cards on the computer, you just have to sort them, usually into alphabetical order.

Developing an Annotated Bibliography

Some instructors may ask you to create an annotated bibliography as a middle step between your working bibliography and your Works Cited page. An annotated bibliography is the same as a working bibliography except that it includes comments about the sources. These notes enable your instructor to assess your progress. They also help you evaluate your information more easily. For example, you might note that some sources are difficult to find, hard to read, or especially useful.

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

- Cambridge Libraries

Study Skills

Research skills.

- Searching the literature

- Note making for dissertations

- Research Data Management

- Copyright and licenses

- Publishing in journals

- Publishing academic books

- Depositing your thesis

- Research metrics

- Build your online profile

- Finding support

Note making for dissertations: First steps into writing

Note making (as opposed to note taking) is an active practice of recording relevant parts of reading for your research as well as your reflections and critiques of those studies. Note making, therefore, is a pre-writing exercise that helps you to organise your thoughts prior to writing. In this module, we will cover:

- The difference between note taking and note making

- Seven tips for good note making

- Strategies for structuring your notes and asking critical questions

- Different styles of note making

To complete this section, you will need:

- Approximately 20-30 minutes.

- Access to the internet. All the resources used here are available freely.

- Some equipment for jotting down your thoughts, a pen and paper will do, or your phone or another electronic device.

Note taking v note making

When you think about note taking, what comes to mind? Perhaps trying to record everything said in a lecture? Perhaps trying to write down everything included in readings required for a course?

- Note taking is a passive process. When you take notes, you are often trying to record everything that you are reading or listening to. However, you may have noticed that this takes a lot of effort and often results in too many notes to be useful.

- Note making , on the other hand, is an active practice, based on the needs and priorities of your project. Note making is an opportunity for you to ask critical questions of your readings and to synthesise ideas as they pertain to your research questions. Making notes is a pre-writing exercise that develops your academic voice and makes writing significantly easier.

Seven tips for effective note making

Note making is an active process based on the needs of your research. This video contains seven tips to help you make brilliant notes from articles and books to make the most of the time you spend reading and writing.

- Transcript of Seven Tips for Effective Notemaking

Question prompts for strategic note making

You might consider structuring your notes to answer the following questions. Remember that note making is based on your needs, so not all of these questions will apply in all cases. You might try answering these questions using the note making styles discussed in the next section.

- Question prompts for strategic note making

- Background question prompts

- Critical question prompts

- Synthesis question prompts

Answer these six questions to frame your reading and provide context.

- What is the context in which the text was written? What came before it? Are there competing ideas?

- Who is the intended audience?

- What is the author’s purpose?

- How is the writing organised?

- What are the author’s methods?

- What is the author’s key argument and conclusions?

Answer these six questions to determine your critical perspectivess and develop your academic voice.

- What are the most interesting/compelling ideas (to you) in this study?

- Why do you find them interesting? How do they relate to your study?

- What questions do you have about the study?

- What could it cover better? How could it have defended its research better?

- What are the implications of the study? (Look not just to the conclusions but also to definitions and models)

- Are there any gaps in the study? (Look not just at conclusions but definitions, literature review, methodology)

Answer these five questions to compare aspects of various studies (such as for a literature review.

- What are the similarities and differences in the literature?

- Critically analyse the strengths, limitations, debates and themes that emerg from the literature.

- What would you suggest for future research or practice?

- Where are the gaps in the literature? What is missing? Why?

- What new questions should be asked in this area of study?

Styles of note making

- Linear notes . Great for recording thoughts about your readings. [video]

- Mind mapping : Great for thinking through complex topics. [video]

Further sites that discuss techniques for note making:

- Note-taking techniques

- Common note-taking methods

- Strategies for effective note making

Did you know?

How did you find this Research Skills module

Image Credits: Image #1: David Travis on Unsplash ; Image #2: Charles Deluvio on Unsplash

- << Previous: Searching the literature

- Next: Research Data Management >>

- Last Updated: Sep 18, 2023 9:07 PM

- URL: https://libguides.cam.ac.uk/research-skills

© Cambridge University Libraries | Accessibility | Privacy policy | Log into LibApps

Writing a Research Paper: 5. Taking Notes & Documenting Sources

- Getting Started

- 1. Topic Ideas

- 2. Thesis Statement & Outline

- 3. Appropriate Sources

- 4. Search Techniques

- 5. Taking Notes & Documenting Sources

- 6. Evaluating Sources

- 7. Citations & Plagiarism

- 8. Writing Your Research Paper

Taking Notes & Documenting Sources

How to take notes and document sources.

Note taking is a very important part of the research process. It will help you:

- keep your ideas and sources organized

- effectively use the information you find

- avoid plagiarism

When you find good information to be used in your paper:

- Read the text critically, think how it is related to your argument, and decide how you are going to use it in your paper.

- Select the material that is relevant to your argument.

- Copy the original text for direct quotations or briefly summarize the content in your own words, and make note of how you will use it.

- Copy the citation or publication information of the source.

- << Previous: 4. Search Techniques

- Next: 6. Evaluating Sources >>

- Last Updated: Sep 26, 2023 5:26 PM

- URL: https://kenrick.libguides.com/writing-a-research-paper

- Peterborough

Useful Research Notes

Why is notetaking important, what should i note.

- Guidelines for good notetaking

5 Notetaking Pitfalls to Avoid

- Note templates

Good notes ask questions, summarize key points, analyse, connect to your thesis, and to other sources.

Taking notes helps you read analytically and critically. Notetaking also provides distance from sources, making it a useful strategy to avoid plagiarism.

Bibliographic or Reference Information

Before taking any notes on content, record the bibliographic information. For books, r ecord the author, title, publisher, place of publication, and date published and for journal articles, you need the name of the journal, the volume and issue numbers, the year published, and pages.

Summary or Paraphrase

Most of your notes will be of summaries of an author’s ideas, arguments, or findings with some paraphrases of more specific ideas. It is essential that you strive for accuracy. Do not confuse what you want research to show with what it does show, and do not make a point out of context.

Facts and Figures

Be meticulous when you record facts or figures.

Quote thoughtfully and carefully; take note of context so you can be true to the author’s intent. Remember to always place quotation marks around direct quotations in your notes.

Record important terms or words that need clarification. Your ability to use these words correctly and to define terms clearly will affect the success of your argument and analysis.

Response and Analysis

Record your insights and questions as you read; your notes will then provide that necessary balance between yourself and the material.

- Consider how the interpretation offered by the text addresses your topic and it relates to your thesis.

- Compare and contrast competing arguments between scholars.

- Assess the author’s use of evidence or the logic of his or her argument.

- Ask questions like “how,” “why,” and “so what?”

- Ask how your research supports your thesis or doesn't support it, as the case may be, and how you will have to deal with it in your essay.

Guidelines for Good Notetaking

- Have a clear direction: Maintain a clear focus on the purpose of your work. As you read and research, revise and modify your tentative thesis and outline.

- Organize your notes carefully: set up a folder for your research, save your digital files frequently and clearly label all files.

- Take point-form notes in your own words as much as possible: include your own thoughts and analysis about the reading. Make sure to note references and page numbers for all sources.

- Wait for breaks in the reading (paragraph, sub-section, chapter) before summarizing the author's ideas; then go back to specific details you wish to include.

- Once you have finished the whole text, review your notes, and summarize the key points and how they relate to your work.

- Taking too many notes: without a clear research direction, you may take far too many notes. Consider your purpose; only record ideas relevant to your topic and thesis and which have a place in your outline.

- Using sticky notes or highlighting instead of taking point-from notes: putting ideas into your words makes you think about material more carefully. It also helps avoid plagiarism.

- Copying and pasting from electronic sources: this makes it hard to remember if ideas belong to you or the author. In addition, you may rely too heavily on direct quotation in your paper, with little attention to analysis.

- Incomplete referencing: when you record references at the final stages of writing, it is easier to miss essential information or have difficulty finding the texts again.

- Recording content but not your analysis: ignoring your own response can lead you to a paper with too much summary and not enough analysis.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9 Organizing Research: Taking and Keeping Effective Notes

Once you’ve located the right primary and secondary sources, it’s time to glean all the information you can from them. In this chapter, you’ll first get some tips on taking and organizing notes. The second part addresses how to approach the sort of intermediary assignments (such as book reviews) that are often part of a history course.

Honing your own strategy for organizing your primary and secondary research is a pathway to less stress and better paper success. Moreover, if you can find the method that helps you best organize your notes, these methods can be applied to research you do for any of your classes.

Before the personal computing revolution, most historians labored through archives and primary documents and wrote down their notes on index cards, and then found innovative ways to organize them for their purposes. When doing secondary research, historians often utilized (and many still do) pen and paper for taking notes on secondary sources. With the advent of digital photography and useful note-taking tools like OneNote, some of these older methods have been phased out – though some persist. And, most importantly, once you start using some of the newer techniques below, you may find that you are a little “old school,” and might opt to integrate some of the older techniques with newer technology.

Whether you choose to use a low-tech method of taking and organizing your notes or an app that will help you organize your research, here are a few pointers for good note-taking.

Principles of note-taking

- If you are going low-tech, choose a method that prevents a loss of any notes. Perhaps use one spiral notebook, or an accordion folder, that will keep everything for your project in one space. If you end up taking notes away from your notebook or folder, replace them—or tape them onto blank pages if you are using a notebook—as soon as possible.

- If you are going high-tech, pick one application and stick with it. Using a cloud-based app, including one that you can download to your smart phone, will allow you to keep adding to your notes even if you find yourself with time to take notes unexpectedly.

- When taking notes, whether you’re using 3X5 note cards or using an app described below, write down the author and a shortened title for the publication, along with the page number on EVERY card. We can’t emphasize this point enough; writing down the bibliographic information the first time and repeatedly will save you loads of time later when you are writing your paper and must cite all key information.

- Include keywords or “tags” that capture why you thought to take down this information in a consistent place on each note card (and when using the apps described below). If you are writing a paper about why Martin Luther King, Jr., became a successful Civil Rights movement leader, for example, you may have a few theories as you read his speeches or how those around him described his leadership. Those theories—religious beliefs, choice of lieutenants, understanding of Gandhi—might become the tags you put on each note card.

- Note-taking applications can help organize tags for you, but if you are going low tech, a good idea is to put tags on the left side of a note card, and bibliographic info on the right side.

Organizing research- applications that can help

Using images in research.

- If you are in an archive: make your first picture one that includes the formal collection name, the box number, the folder name and call numbe r and anything else that would help you relocate this information if you or someone else needed to. Do this BEFORE you start taking photos of what is in the folder.

- If you are photographing a book or something you may need to return to the library: take a picture of all the front matter (the title page, the page behind the title with all the publication information, maybe even the table of contents).

Once you have recorded where you find it, resist the urge to rename these photographs. By renaming them, they may be re-ordered and you might forget where you found them. Instead, use tags for your own purposes, and carefully name and date the folder into which the photographs were automatically sorted. There is one free, open-source program, Tropy , which is designed to help organize photos taken in archives, as well as tag, annotate, and organize them. It was developed and is supported by the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University. It is free to download, and you can find it here: https://tropy.org/ ; it is not, however, cloud-based, so you should back up your photos. In other cases, if an archive doesn’t allow photography (this is highly unlikely if you’ve made the trip to the archive), you might have a laptop on hand so that you can transcribe crucial documents.

Using note or project-organizing apps

When you have the time to sit down and begin taking notes on your primary sources, you can annotate your photos in Tropy. Alternatively, OneNote, which is cloud-based, can serve as a way to organize your research. OneNote allows you to create separate “Notebooks” for various projects, but this doesn’t preclude you from searching for terms or tags across projects if the need ever arises. Within each project you can start new tabs, say, for each different collection that you have documents from, or you can start new tabs for different themes that you are investigating. Just as in Tropy, as you go through taking notes on your documents you can create your own “tags” and place them wherever you want in the notes.

Another powerful, free tool to help organize research, especially secondary research though not exclusively, is Zotero found @ https://www.zotero.org/ . Once downloaded, you can begin to save sources (and their URL) that you find on the internet to Zotero. You can create main folders for each major project that you have and then subfolders for various themes if you would like. Just like the other software mentioned, you can create notes and tags about each source, and Zotero can also be used to create bibliographies in the precise format that you will be using. Obviously, this function is super useful when doing a long-term, expansive project like a thesis or dissertation.

How History is Made: A Student’s Guide to Reading, Writing, and Thinking in the Discipline Copyright © 2022 by Stephanie Cole; Kimberly Breuer; Scott W. Palmer; and Brandon Blakeslee is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Research Guides

Gould library, reading well and taking research notes.

- How to read for college

- How to take research notes

- How to use sources in your writing

- Tools for note taking and annotations

- Mobile apps for notes and annotations

- Assistive technology

- How to cite your sources

Be Prepared: Keep track of which notes are direct quotes, which are summary, and which are your own thoughts. For example, enclose direct quotes in quotation marks, and enclose your own thoughts in brackets. That way you'll never be confused when you're writing.

Be Clear: Make sure you have noted the source and page number!

Be Organized: Keep your notes organized but in a single place so that you can refer back to notes about other readings at the same time.

Be Consistent: You'll want to find specific notes later, and one way to do that is to be consistent in the way you describe things. If you use consistent terms or tags or keywords, you'll be able to find your way back more easily.

Recording what you find

Take full notes

Whether you take notes on cards, in a notebook, or on the computer, it's vital to record information accurately and completely. Otherwise, you won't be able to trust your own notes. Most importantly, distinguish between (1) direct quotation; (2) paraphrases and summaries of the text; and (3) your own thoughts. On a computer, you have many options for making these distinctions, such as parentheses, brackets, italic or bold text, etc.

Know when to quote, paraphrase, and summarize

- Summarize when you only need to remember the main point of the passage, chapter, etc.

- Paraphrase when you are able to able to clearly state a source's point or meaning in your own words.

- Quote exactly when you need the author's exact words or authority as evidience to back up your claim. You may also want to be sure and use the author's exact wording, either because they stated their point so well, or because you want to refute that point and need to demonstrate you aren't misrepresenting the author's words.

Get the context right

Don't just record the author's words or ideas; be sure and capture the context and meaning that surrounds those ideas as well. It can be easy to take a short quote from an author that completely misrepresents his or her actual intentions if you fail to take the context into account. You should also be sure to note when the author is paraphrasing or summarizing another author's point of view--don't accidentally represent those ideas as the ideas of the author.

Example of reading notes

Here is an example of reading notes taken in Evernote, with citation and page numbers noted as well as quotation marks for direct quotes and brackets around the reader's own thoughts.

- << Previous: How to read for college

- Next: How to use sources in your writing >>

- Last Updated: Feb 7, 2024 12:22 PM

- URL: https://gouldguides.carleton.edu/activereading

Questions? Contact [email protected]

Powered by Springshare.

Research Note

Takes effect immediately upon receipt. — In-game description

“ Takes effect immediately upon receipt. — In-game description

As wallet currency:

“ Acquired by deconstructing crafted items with research kits. Used at vendors in Cantha and to craft newer recipes. — In-game description

Research Notes are a currency and crafting material earned by salvaging crafted items with a Research Kit , or by toggling the option to automatically research crafted items in the crafting interface. They are automatically stored in the wallet upon acquisition.

- 1.1 Salvaged from

- 1.2 Contained in

- 2.1 Multiple disciplines

- 2.2 Armorsmith

- 2.3 Artificer

- 2.4 Huntsman

- 2.5 Jeweler

- 2.6 Leatherworker

- 2.8 Weaponsmith

- 3 Currency for

- 5 External links

Acquisition [ edit ]

Salvaged from [ edit ].

Use a Research Kit to salvage crafted items for research notes:

- Utility items (only above Novice level recipes)

- Crafted food (only above Novice level recipes) 1 2 3

- Crafted armor 4

- Crafted weapons 5

- Crafted tonics

- Crafted potions (only above Novice level recipes)

Use a Research Kit on a stat changed non-salvageable named Ascended Weapon and Armor:

- If an Ascended Weapon/Armor (from named boxes, e.g. Sabetha's armor, Mist-Touched defender armor) is un-salvageable since its not crafted, you can stat change them in the Mystic Forge to normal ascended gear, then salvage them using a Research Kit for research notes.

Extract any runes, sigils, and infusions that you need first. As they will be lost.

- Salvage research can be found here .

- Contains 5 research notes.

- Ascended feasts (2)

- Crafted exotic armor (8-10)

- Crafted exotic weapons (8-10)

- Contains 25 research notes.

- Ascended feasts (1-2)

- Crafted exotic armor (3-4)

- Crafted exotic weapons (2-4)

- Crafted ascended armor excluding coats(4-20) [ verification requested ]

- Contains 100 research notes.

- Crafted exotic armor (0-1)

- Crafted ascended armor excluding coats (2-6) [ verification requested ]

- Crafted ascended coats (2-3)

- Crafted ascended weapons (2-3)

- Contains 500 research notes.

- Crafted ascended armor (1)

- Crafted ascended weapons (1)

Contained in [ edit ]

Used in [ edit ]

Multiple disciplines, leatherworker, weaponsmith, currency for [ edit ].

- Guest Elder

- Keycard Exchange Service

- Repurposed Jade Servitor

- Requisitions Specialist

- Xunlai Jade Sales Associate

- Zazzl and Archaeologist Vorri

Notes [ edit ]

- Since the July 7, 2022 game update , the Research Notes go directly into the wallet. The previously earned notes can be double-clicked to add to the wallet.

External links [ edit ]

- Fast Farming Community | Salvaging costs per Research Note

- Service items

- Item articles with stub sections

- Pages with verification requests

Navigation menu

Page actions, other languages, personal tools.

- Not logged in

- Contributions

- Create account

- Quick links

- Community portal

- Recent changes

- Random page

Wiki support

- Help center

- Editing guide

- Admin noticeboard

- Report a wiki bug

- What links here

- Related changes

- Special pages

- Printable version

- Permanent link

- Page information

- Transclusion list

- Browse properties

- This page was last edited on 19 March 2024, at 02:24.

- Content is available under these licensing terms unless otherwise noted.

- Privacy policy

- About Guild Wars 2 Wiki

- Disclaimers

- Mobile view

- AI Templates

- Get a demo Sign up for free Log in Log in

How to code and organize research notes for analysis like a pro

15 Minute Read

Conducting high quality, rigorous research is tough, regardless of how seasoned you are, because each research project is completely unique. In addition to actually doing the research itself, aggregating and organizing research notes can be overwhelming.

Making sense of research data during synthesis and writing up a research report takes a lot of time. And if you don't organize your research notes and set yourself up for success early on, it will take even longer. You’ll miss out on important observations that will slow down your analysis and impact the quality of your research findings.

Taking the time to code and organize your research notes is key to avoid feeling overwhelmed by the sheer volume of data. In this article, we’ll share some practical tips to set you up for doing high quality analysis and synthesis.

Re-Organize, Re-Group, Re-Compile: A method for making meaning out of mess.

You must be wondering - organize, group and compile make sense. But what does the 'Re' mean? This is a recursive approach to research. You cast a wide net to gather as many ideas and data points as you can when conducting your research. Don’t filter the data or try to make sense of it prematurely.

This data-gathering stage is where you pull in qualitative data, like interview transcripts with direct quotes from a user interview analysis and/or observations from a user researcher’s notes. Only once you’ve collected all of your data do you start analysis.