Reliability and validity of your thesis

Describing the reliability and validity of your research is an important part of your thesis.

Students in higher professional education as well as for academic students are required to describe these, and both are usually discussed in your methodology.

We help students with this daily, because describing these research concepts is often not too hard, but using them? That’s a different story!

In this article we explain these concepts and give you tips on how to use them in your thesis. Good luck!

Reliability, an example

When you look up the term reliability in you research manual, you will often find different definitions.

In the end, what matters with reliability is that the results of your research match the actual situation as much as possible. When a fellow student would research your topic, you want him or her to obtain practically the same results. Only then can we speak of a reliable study and will your research be reproducible.

Reliability in quantitative research

Reliability in quantitative research is often expressed as a reliability percentage of 95% or 99%. Do you want to know how many respondents you need to achieve this reliability score? You can use a sample size calculator, for example using this link.

You can also test the reliability of questionnaires in SPSS by calculating the so-called Cronbach’s Alpha. If this value is .80 or higher, this indicates a high reliability.

Most literature indicates that a score of 0.70 or higher is also still reliable.

Watch out: you can’t just combine all questions (with different response categories)!

Contact us now…

Validity in quantitative research

The validity of quantitative research usually has to do with which questions you ask your respondents. Validity means that the results you find will be factually correct.

It is often best to draw up your questions after you have finished your literature review (which is also most reliable!). You can then better judge which concepts are important, and use these concepts to draw up different questions (indicators). While doing this, always keep in mind the goal of the study and your sub-questions.

We have previously discussed the methodological validity, but you can also – this applies especially to academic students – look at the statistical validity. For this you check whether the used statistical models meet the underlying assumptions.

Reliability and validity in qualitative research

Reliability is just as important in qualitative research as it is in quantitative research. In discussing this, you need to describe certain things regarding the circumstances of your research, like for example the fact that a quiet location was chosen (so that respondents could not be disturbed), the attitude of the interviewer (respondents should not be influenced, so take on an open attitude, ask open question instead of guiding ones, stay silent in between, etc.). It is also important that you describe the representativeness of your sample, as the representativeness of the sample makes for better reliability. If you wish, for example, to map the wishes and needs of a company’s target group, try not just to include current customers in your study but also and especially potential new costumers.

Furthermore, it is good to discuss why you have specifically chosen this research method and what the pros and cons of this method are.

When using interviews, for example, you can choose between structured, semi-structured or in-depth interviews. The goal is to justify your choice as well as possible. (Tip: it often helps to describe the purpose of the interviews.)

As with quantitative research, validity in qualitative research is about drawing up the right questions/topics that really cover your subject matter. Here too you can make use of an operationalization model. The interview questions (with structured and semi-structured interviews) are often listed in an interview-guide, to help you go to an interview well prepared. With in-depth interviews it is common to use an item-list.

In this document you can also write down for yourself an introduction that you give each interviewee at the start of an interview, and you also mention the confidentiality. See the image below for an example of an interview-guide.

Finally you need to describe here how you are going to perform the analysis and whether you have for example recorded the interviews (and transcribed them).

Moreover, it is always good to present your interview-questions to an expert and to do some trial interviews if possible.

Describing reliability and validity in your thesis

To summarize, discuss as many aspects as possible that have led to the highest possible reliability of your study. Include at least the following:

Reliability of literature review (secondary research)

The definition of a literature review according to Topscriptie is: An overview of already existing information on your subject (what is known already) that shows the context of and identifies ‘gaps’ in the literature, takes the form of a critical and coherent review and sheds light on the connections between previous studies.

Many students forget to describe how they have tried to keep the reliability of their literature review (desk research) as high as possible. It is important to discuss this in your thesis. Describe for example the following aspects:

With the above mentioned tips from Topscriptie you can get started yourself on describing the reliability and validity of your study in your thesis. Don’t forget to discuss the limits of your study in your discussion . It actually makes your article more solid when you can show that you are aware of these. Don’t forget that every thesis and every study has its own problems with the reliability and validity.

Topscriptie has already helped more than 6,000 students!

Let us help you with your studies or graduation. Discover what we can do for you.

Call or WhatsApp a thesis supervisor

Winner of the best thesis agency in the Netherlands

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Validity – Types, Examples and Guide

Validity – Types, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

Definition:

Validity refers to the extent to which a concept, measure, or study accurately represents the intended meaning or reality it is intended to capture. It is a fundamental concept in research and assessment that assesses the soundness and appropriateness of the conclusions, inferences, or interpretations made based on the data or evidence collected.

Research Validity

Research validity refers to the degree to which a study accurately measures or reflects what it claims to measure. In other words, research validity concerns whether the conclusions drawn from a study are based on accurate, reliable and relevant data.

Validity is a concept used in logic and research methodology to assess the strength of an argument or the quality of a research study. It refers to the extent to which a conclusion or result is supported by evidence and reasoning.

How to Ensure Validity in Research

Ensuring validity in research involves several steps and considerations throughout the research process. Here are some key strategies to help maintain research validity:

Clearly Define Research Objectives and Questions

Start by clearly defining your research objectives and formulating specific research questions. This helps focus your study and ensures that you are addressing relevant and meaningful research topics.

Use appropriate research design

Select a research design that aligns with your research objectives and questions. Different types of studies, such as experimental, observational, qualitative, or quantitative, have specific strengths and limitations. Choose the design that best suits your research goals.

Use reliable and valid measurement instruments

If you are measuring variables or constructs, ensure that the measurement instruments you use are reliable and valid. This involves using established and well-tested tools or developing your own instruments through rigorous validation processes.

Ensure a representative sample

When selecting participants or subjects for your study, aim for a sample that is representative of the population you want to generalize to. Consider factors such as age, gender, socioeconomic status, and other relevant demographics to ensure your findings can be generalized appropriately.

Address potential confounding factors

Identify potential confounding variables or biases that could impact your results. Implement strategies such as randomization, matching, or statistical control to minimize the influence of confounding factors and increase internal validity.

Minimize measurement and response biases

Be aware of measurement biases and response biases that can occur during data collection. Use standardized protocols, clear instructions, and trained data collectors to minimize these biases. Employ techniques like blinding or double-blinding in experimental studies to reduce bias.

Conduct appropriate statistical analyses

Ensure that the statistical analyses you employ are appropriate for your research design and data type. Select statistical tests that are relevant to your research questions and use robust analytical techniques to draw accurate conclusions from your data.

Consider external validity

While it may not always be possible to achieve high external validity, be mindful of the generalizability of your findings. Clearly describe your sample and study context to help readers understand the scope and limitations of your research.

Peer review and replication

Submit your research for peer review by experts in your field. Peer review helps identify potential flaws, biases, or methodological issues that can impact validity. Additionally, encourage replication studies by other researchers to validate your findings and enhance the overall reliability of the research.

Transparent reporting

Clearly and transparently report your research methods, procedures, data collection, and analysis techniques. Provide sufficient details for others to evaluate the validity of your study and replicate your work if needed.

Types of Validity

There are several types of validity that researchers consider when designing and evaluating studies. Here are some common types of validity:

Internal Validity

Internal validity relates to the degree to which a study accurately identifies causal relationships between variables. It addresses whether the observed effects can be attributed to the manipulated independent variable rather than confounding factors. Threats to internal validity include selection bias, history effects, maturation of participants, and instrumentation issues.

External Validity

External validity concerns the generalizability of research findings to the broader population or real-world settings. It assesses the extent to which the results can be applied to other individuals, contexts, or timeframes. Factors that can limit external validity include sample characteristics, research settings, and the specific conditions under which the study was conducted.

Construct Validity

Construct validity examines whether a study adequately measures the intended theoretical constructs or concepts. It focuses on the alignment between the operational definitions used in the study and the underlying theoretical constructs. Construct validity can be threatened by issues such as poor measurement tools, inadequate operational definitions, or a lack of clarity in the conceptual framework.

Content Validity

Content validity refers to the degree to which a measurement instrument or test adequately covers the entire range of the construct being measured. It assesses whether the items or questions included in the measurement tool represent the full scope of the construct. Content validity is often evaluated through expert judgment, reviewing the relevance and representativeness of the items.

Criterion Validity

Criterion validity determines the extent to which a measure or test is related to an external criterion or standard. It assesses whether the results obtained from a measurement instrument align with other established measures or outcomes. Criterion validity can be divided into two subtypes: concurrent validity, which examines the relationship between the measure and the criterion at the same time, and predictive validity, which investigates the measure’s ability to predict future outcomes.

Face Validity

Face validity refers to the degree to which a measurement or test appears, on the surface, to measure what it intends to measure. It is a subjective assessment based on whether the items seem relevant and appropriate to the construct being measured. Face validity is often used as an initial evaluation before conducting more rigorous validity assessments.

Importance of Validity

Validity is crucial in research for several reasons:

- Accurate Measurement: Validity ensures that the measurements or observations in a study accurately represent the intended constructs or variables. Without validity, researchers cannot be confident that their results truly reflect the phenomena they are studying. Validity allows researchers to draw accurate conclusions and make meaningful inferences based on their findings.

- Credibility and Trustworthiness: Validity enhances the credibility and trustworthiness of research. When a study demonstrates high validity, it indicates that the researchers have taken appropriate measures to ensure the accuracy and integrity of their work. This strengthens the confidence of other researchers, peers, and the wider scientific community in the study’s results and conclusions.

- Generalizability: Validity helps determine the extent to which research findings can be generalized beyond the specific sample and context of the study. By addressing external validity, researchers can assess whether their results can be applied to other populations, settings, or situations. This information is valuable for making informed decisions, implementing interventions, or developing policies based on research findings.

- Sound Decision-Making: Validity supports informed decision-making in various fields, such as medicine, psychology, education, and social sciences. When validity is established, policymakers, practitioners, and professionals can rely on research findings to guide their actions and interventions. Validity ensures that decisions are based on accurate and trustworthy information, which can lead to better outcomes and more effective practices.

- Avoiding Errors and Bias: Validity helps researchers identify and mitigate potential errors and biases in their studies. By addressing internal validity, researchers can minimize confounding factors and alternative explanations, ensuring that the observed effects are genuinely attributable to the manipulated variables. Validity assessments also highlight measurement errors or shortcomings, enabling researchers to improve their measurement tools and procedures.

- Progress of Scientific Knowledge: Validity is essential for the advancement of scientific knowledge. Valid research contributes to the accumulation of reliable and valid evidence, which forms the foundation for building theories, developing models, and refining existing knowledge. Validity allows researchers to build upon previous findings, replicate studies, and establish a cumulative body of knowledge in various disciplines. Without validity, the scientific community would struggle to make meaningful progress and establish a solid understanding of the phenomena under investigation.

- Ethical Considerations: Validity is closely linked to ethical considerations in research. Conducting valid research ensures that participants’ time, effort, and data are not wasted on flawed or invalid studies. It upholds the principle of respect for participants’ autonomy and promotes responsible research practices. Validity is also important when making claims or drawing conclusions that may have real-world implications, as misleading or invalid findings can have adverse effects on individuals, organizations, or society as a whole.

Examples of Validity

Here are some examples of validity in different contexts:

- Example 1: All men are mortal. John is a man. Therefore, John is mortal. This argument is logically valid because the conclusion follows logically from the premises.

- Example 2: If it is raining, then the ground is wet. The ground is wet. Therefore, it is raining. This argument is not logically valid because there could be other reasons for the ground being wet, such as watering the plants.

- Example 1: In a study examining the relationship between caffeine consumption and alertness, the researchers use established measures of both variables, ensuring that they are accurately capturing the concepts they intend to measure. This demonstrates construct validity.

- Example 2: A researcher develops a new questionnaire to measure anxiety levels. They administer the questionnaire to a group of participants and find that it correlates highly with other established anxiety measures. This indicates good construct validity for the new questionnaire.

- Example 1: A study on the effects of a particular teaching method is conducted in a controlled laboratory setting. The findings of the study may lack external validity because the conditions in the lab may not accurately reflect real-world classroom settings.

- Example 2: A research study on the effects of a new medication includes participants from diverse backgrounds and age groups, increasing the external validity of the findings to a broader population.

- Example 1: In an experiment, a researcher manipulates the independent variable (e.g., a new drug) and controls for other variables to ensure that any observed effects on the dependent variable (e.g., symptom reduction) are indeed due to the manipulation. This establishes internal validity.

- Example 2: A researcher conducts a study examining the relationship between exercise and mood by administering questionnaires to participants. However, the study lacks internal validity because it does not control for other potential factors that could influence mood, such as diet or stress levels.

- Example 1: A teacher develops a new test to assess students’ knowledge of a particular subject. The items on the test appear to be relevant to the topic at hand and align with what one would expect to find on such a test. This suggests face validity, as the test appears to measure what it intends to measure.

- Example 2: A company develops a new customer satisfaction survey. The questions included in the survey seem to address key aspects of the customer experience and capture the relevant information. This indicates face validity, as the survey seems appropriate for assessing customer satisfaction.

- Example 1: A team of experts reviews a comprehensive curriculum for a high school biology course. They evaluate the curriculum to ensure that it covers all the essential topics and concepts necessary for students to gain a thorough understanding of biology. This demonstrates content validity, as the curriculum is representative of the domain it intends to cover.

- Example 2: A researcher develops a questionnaire to assess career satisfaction. The questions in the questionnaire encompass various dimensions of job satisfaction, such as salary, work-life balance, and career growth. This indicates content validity, as the questionnaire adequately represents the different aspects of career satisfaction.

- Example 1: A company wants to evaluate the effectiveness of a new employee selection test. They administer the test to a group of job applicants and later assess the job performance of those who were hired. If there is a strong correlation between the test scores and subsequent job performance, it suggests criterion validity, indicating that the test is predictive of job success.

- Example 2: A researcher wants to determine if a new medical diagnostic tool accurately identifies a specific disease. They compare the results of the diagnostic tool with the gold standard diagnostic method and find a high level of agreement. This demonstrates criterion validity, indicating that the new tool is valid in accurately diagnosing the disease.

Where to Write About Validity in A Thesis

In a thesis, discussions related to validity are typically included in the methodology and results sections. Here are some specific places where you can address validity within your thesis:

Research Design and Methodology

In the methodology section, provide a clear and detailed description of the measures, instruments, or data collection methods used in your study. Discuss the steps taken to establish or assess the validity of these measures. Explain the rationale behind the selection of specific validity types relevant to your study, such as content validity, criterion validity, or construct validity. Discuss any modifications or adaptations made to existing measures and their potential impact on validity.

Measurement Procedures

In the methodology section, elaborate on the procedures implemented to ensure the validity of measurements. Describe how potential biases or confounding factors were addressed, controlled, or accounted for to enhance internal validity. Provide details on how you ensured that the measurement process accurately captures the intended constructs or variables of interest.

Data Collection

In the methodology section, discuss the steps taken to collect data and ensure data validity. Explain any measures implemented to minimize errors or biases during data collection, such as training of data collectors, standardized protocols, or quality control procedures. Address any potential limitations or threats to validity related to the data collection process.

Data Analysis and Results

In the results section, present the analysis and findings related to validity. Report any statistical tests, correlations, or other measures used to assess validity. Provide interpretations and explanations of the results obtained. Discuss the implications of the validity findings for the overall reliability and credibility of your study.

Limitations and Future Directions

In the discussion or conclusion section, reflect on the limitations of your study, including limitations related to validity. Acknowledge any potential threats or weaknesses to validity that you encountered during your research. Discuss how these limitations may have influenced the interpretation of your findings and suggest avenues for future research that could address these validity concerns.

Applications of Validity

Validity is applicable in various areas and contexts where research and measurement play a role. Here are some common applications of validity:

Psychological and Behavioral Research

Validity is crucial in psychology and behavioral research to ensure that measurement instruments accurately capture constructs such as personality traits, intelligence, attitudes, emotions, or psychological disorders. Validity assessments help researchers determine if their measures are truly measuring the intended psychological constructs and if the results can be generalized to broader populations or real-world settings.

Educational Assessment

Validity is essential in educational assessment to determine if tests, exams, or assessments accurately measure students’ knowledge, skills, or abilities. It ensures that the assessment aligns with the educational objectives and provides reliable information about student performance. Validity assessments help identify if the assessment is valid for all students, regardless of their demographic characteristics, language proficiency, or cultural background.

Program Evaluation

Validity plays a crucial role in program evaluation, where researchers assess the effectiveness and impact of interventions, policies, or programs. By establishing validity, evaluators can determine if the observed outcomes are genuinely attributable to the program being evaluated rather than extraneous factors. Validity assessments also help ensure that the evaluation findings are applicable to different populations, contexts, or timeframes.

Medical and Health Research

Validity is essential in medical and health research to ensure the accuracy and reliability of diagnostic tools, measurement instruments, and clinical assessments. Validity assessments help determine if a measurement accurately identifies the presence or absence of a medical condition, measures the effectiveness of a treatment, or predicts patient outcomes. Validity is crucial for establishing evidence-based medicine and informing medical decision-making.

Social Science Research

Validity is relevant in various social science disciplines, including sociology, anthropology, economics, and political science. Researchers use validity to ensure that their measures and methods accurately capture social phenomena, such as social attitudes, behaviors, social structures, or economic indicators. Validity assessments support the reliability and credibility of social science research findings.

Market Research and Surveys

Validity is important in market research and survey studies to ensure that the survey questions effectively measure consumer preferences, buying behaviors, or attitudes towards products or services. Validity assessments help researchers determine if the survey instrument is accurately capturing the desired information and if the results can be generalized to the target population.

Limitations of Validity

Here are some limitations of validity:

- Construct Validity: Limitations of construct validity include the potential for measurement error, inadequate operational definitions of constructs, or the failure to capture all aspects of a complex construct.

- Internal Validity: Limitations of internal validity may arise from confounding variables, selection bias, or the presence of extraneous factors that could influence the study outcomes, making it difficult to attribute causality accurately.

- External Validity: Limitations of external validity can occur when the study sample does not represent the broader population, when the research setting differs significantly from real-world conditions, or when the study lacks ecological validity, i.e., the findings do not reflect real-world complexities.

- Measurement Validity: Limitations of measurement validity can arise from measurement error, inadequately designed or flawed measurement scales, or limitations inherent in self-report measures, such as social desirability bias or recall bias.

- Statistical Conclusion Validity: Limitations in statistical conclusion validity can occur due to sampling errors, inadequate sample sizes, or improper statistical analysis techniques, leading to incorrect conclusions or generalizations.

- Temporal Validity: Limitations of temporal validity arise when the study results become outdated due to changes in the studied phenomena, interventions, or contextual factors.

- Researcher Bias: Researcher bias can affect the validity of a study. Biases can emerge through the researcher’s subjective interpretation, influence of personal beliefs, or preconceived notions, leading to unintentional distortion of findings or failure to consider alternative explanations.

- Ethical Validity: Limitations can arise if the study design or methods involve ethical concerns, such as the use of deceptive practices, inadequate informed consent, or potential harm to participants.

Also see Reliability Vs Validity

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Internal Consistency Reliability – Methods...

Internal Validity – Threats, Examples and Guide

Split-Half Reliability – Methods, Examples and...

Alternate Forms Reliability – Methods, Examples...

Reliability – Types, Examples and Guide

Test-Retest Reliability – Methods, Formula and...

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- The 4 Types of Validity in Research | Definitions & Examples

The 4 Types of Validity in Research | Definitions & Examples

Published on September 6, 2019 by Fiona Middleton . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Validity tells you how accurately a method measures something. If a method measures what it claims to measure, and the results closely correspond to real-world values, then it can be considered valid. There are four main types of validity:

- Construct validity : Does the test measure the concept that it’s intended to measure?

- Content validity : Is the test fully representative of what it aims to measure?

- Face validity : Does the content of the test appear to be suitable to its aims?

- Criterion validity : Do the results accurately measure the concrete outcome they are designed to measure?

In quantitative research , you have to consider the reliability and validity of your methods and measurements.

Note that this article deals with types of test validity, which determine the accuracy of the actual components of a measure. If you are doing experimental research, you also need to consider internal and external validity , which deal with the experimental design and the generalizability of results.

Table of contents

Construct validity, content validity, face validity, criterion validity, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about types of validity.

Construct validity evaluates whether a measurement tool really represents the thing we are interested in measuring. It’s central to establishing the overall validity of a method.

What is a construct?

A construct refers to a concept or characteristic that can’t be directly observed, but can be measured by observing other indicators that are associated with it.

Constructs can be characteristics of individuals, such as intelligence, obesity, job satisfaction, or depression; they can also be broader concepts applied to organizations or social groups, such as gender equality, corporate social responsibility, or freedom of speech.

There is no objective, observable entity called “depression” that we can measure directly. But based on existing psychological research and theory, we can measure depression based on a collection of symptoms and indicators, such as low self-confidence and low energy levels.

What is construct validity?

Construct validity is about ensuring that the method of measurement matches the construct you want to measure. If you develop a questionnaire to diagnose depression, you need to know: does the questionnaire really measure the construct of depression? Or is it actually measuring the respondent’s mood, self-esteem, or some other construct?

To achieve construct validity, you have to ensure that your indicators and measurements are carefully developed based on relevant existing knowledge. The questionnaire must include only relevant questions that measure known indicators of depression.

The other types of validity described below can all be considered as forms of evidence for construct validity.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Content validity assesses whether a test is representative of all aspects of the construct.

To produce valid results, the content of a test, survey or measurement method must cover all relevant parts of the subject it aims to measure. If some aspects are missing from the measurement (or if irrelevant aspects are included), the validity is threatened and the research is likely suffering from omitted variable bias .

A mathematics teacher develops an end-of-semester algebra test for her class. The test should cover every form of algebra that was taught in the class. If some types of algebra are left out, then the results may not be an accurate indication of students’ understanding of the subject. Similarly, if she includes questions that are not related to algebra, the results are no longer a valid measure of algebra knowledge.

Face validity considers how suitable the content of a test seems to be on the surface. It’s similar to content validity, but face validity is a more informal and subjective assessment.

You create a survey to measure the regularity of people’s dietary habits. You review the survey items, which ask questions about every meal of the day and snacks eaten in between for every day of the week. On its surface, the survey seems like a good representation of what you want to test, so you consider it to have high face validity.

As face validity is a subjective measure, it’s often considered the weakest form of validity. However, it can be useful in the initial stages of developing a method.

Criterion validity evaluates how well a test can predict a concrete outcome, or how well the results of your test approximate the results of another test.

What is a criterion variable?

A criterion variable is an established and effective measurement that is widely considered valid, sometimes referred to as a “gold standard” measurement. Criterion variables can be very difficult to find.

What is criterion validity?

To evaluate criterion validity, you calculate the correlation between the results of your measurement and the results of the criterion measurement. If there is a high correlation, this gives a good indication that your test is measuring what it intends to measure.

A university professor creates a new test to measure applicants’ English writing ability. To assess how well the test really does measure students’ writing ability, she finds an existing test that is considered a valid measurement of English writing ability, and compares the results when the same group of students take both tests. If the outcomes are very similar, the new test has high criterion validity.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Face validity and content validity are similar in that they both evaluate how suitable the content of a test is. The difference is that face validity is subjective, and assesses content at surface level.

When a test has strong face validity, anyone would agree that the test’s questions appear to measure what they are intended to measure.

For example, looking at a 4th grade math test consisting of problems in which students have to add and multiply, most people would agree that it has strong face validity (i.e., it looks like a math test).

On the other hand, content validity evaluates how well a test represents all the aspects of a topic. Assessing content validity is more systematic and relies on expert evaluation. of each question, analyzing whether each one covers the aspects that the test was designed to cover.

A 4th grade math test would have high content validity if it covered all the skills taught in that grade. Experts(in this case, math teachers), would have to evaluate the content validity by comparing the test to the learning objectives.

Criterion validity evaluates how well a test measures the outcome it was designed to measure. An outcome can be, for example, the onset of a disease.

Criterion validity consists of two subtypes depending on the time at which the two measures (the criterion and your test) are obtained:

- Concurrent validity is a validation strategy where the the scores of a test and the criterion are obtained at the same time .

- Predictive validity is a validation strategy where the criterion variables are measured after the scores of the test.

Convergent validity and discriminant validity are both subtypes of construct validity . Together, they help you evaluate whether a test measures the concept it was designed to measure.

- Convergent validity indicates whether a test that is designed to measure a particular construct correlates with other tests that assess the same or similar construct.

- Discriminant validity indicates whether two tests that should not be highly related to each other are indeed not related. This type of validity is also called divergent validity .

You need to assess both in order to demonstrate construct validity. Neither one alone is sufficient for establishing construct validity.

The purpose of theory-testing mode is to find evidence in order to disprove, refine, or support a theory. As such, generalizability is not the aim of theory-testing mode.

Due to this, the priority of researchers in theory-testing mode is to eliminate alternative causes for relationships between variables . In other words, they prioritize internal validity over external validity , including ecological validity .

It’s often best to ask a variety of people to review your measurements. You can ask experts, such as other researchers, or laypeople, such as potential participants, to judge the face validity of tests.

While experts have a deep understanding of research methods , the people you’re studying can provide you with valuable insights you may have missed otherwise.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Middleton, F. (2023, June 22). The 4 Types of Validity in Research | Definitions & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved March 18, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/types-of-validity/

Is this article helpful?

Fiona Middleton

Other students also liked, reliability vs. validity in research | difference, types and examples, construct validity | definition, types, & examples, external validity | definition, types, threats & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

The Quintessence of Basic and Clinical Research and Scientific Publishing pp 769–781 Cite as

Writing a Postgraduate or Doctoral Thesis: A Step-by-Step Approach

- Usha Y. Nayak 4 ,

- Praveen Hoogar 5 ,

- Srinivas Mutalik 4 &

- N. Udupa 6

- First Online: 01 October 2023

581 Accesses

1 Citations

A key characteristic looked after by postgraduate or doctoral students is how they communicate and defend their knowledge. Many candidates believe that there is insufficient instruction on constructing strong arguments. The thesis writing procedure must be meticulously followed to achieve outstanding results. It should be well organized, simple to read, and provide detailed explanations of the core research concepts. Each section in a thesis should be carefully written to make sure that it transitions logically from one to the next in a smooth way and is free of any unclear, cluttered, or redundant elements that make it difficult for the reader to understand what is being tried to convey. In this regard, students must acquire the information and skills to successfully create a strong and effective thesis. A step-by-step description of the thesis/dissertation writing process is provided in this chapter.

- Dissertation

- Postgraduate

- SMART objectives

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Carter S, Guerin C, Aitchison C (2020) Doctoral writing: practices, processes and pleasures. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-1808-9

Book Google Scholar

Odena O, Burgess H (2017) How doctoral students and graduates describe facilitating experiences and strategies for their thesis writing learning process: a qualitative approach. Stud High Educ 42:572–590. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1063598

Article Google Scholar

Stefan R (2022) How to write a good PhD thesis and survive the viva, pp 1–33. http://people.kmi.open.ac.uk/stefan/thesis-writing.pdf

Google Scholar

Barrett D, Rodriguez A, Smith J (2021) Producing a successful PhD thesis. Evid Based Nurs 24:1–2. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebnurs-2020-103376

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Murray R, Newton M (2009) Writing retreat as structured intervention: margin or mainstream? High Educ Res Dev 28:541–553. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360903154126

Thompson P (2012) Thesis and dissertation writing. In: Paltridge B, Starfield S (eds) The handbook of english for specific purposes. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Hoboken, NJ, pp 283–299. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118339855.ch15

Chapter Google Scholar

Faryadi Q (2018) PhD thesis writing process: a systematic approach—how to write your introduction. Creat Educ 09:2534–2545. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2018.915192

Faryadi Q (2019) PhD thesis writing process: a systematic approach—how to write your methodology, results and conclusion. Creat Educ 10:766–783. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2019.104057

Fisher CM, Colin M, Buglear J (2010) Researching and writing a dissertation: an essential guide for business students, 3rd edn. Financial Times/Prentice Hall, Harlow, pp 133–164

Ahmad HR (2016) How to write a doctoral thesis. Pak J Med Sci 32:270–273. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.322.10181

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gosling P, Noordam LD (2011) Mastering your PhD, 2nd edn. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 12–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-15847-6

Cunningham SJ (2004) How to write a thesis. J Orthod 31:144–148. https://doi.org/10.1179/146531204225020445

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Azadeh F, Vaez R (2013) The accuracy of references in PhD theses: a case study. Health Info Libr J 30:232–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12026

Williams RB (2011) Citation systems in the biosciences: a history, classification and descriptive terminology. J Doc 67:995–1014. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220411111183564

Bahadoran Z, Mirmiran P, Kashfi K, Ghasemi A (2020) The principles of biomedical scientific writing: citation. Int J Endocrinol Metab 18:e102622. https://doi.org/10.5812/ijem.102622

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Yaseen NY, Salman HD (2013) Writing scientific thesis/dissertation in biology field: knowledge in reference style writing. Iraqi J Cancer Med Genet 6:5–12

Gorraiz J, Melero-Fuentes D, Gumpenberger C, Valderrama-Zurián J-C (2016) Availability of digital object identifiers (DOIs) in web of science and scopus. J Informet 10:98–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2015.11.008

Khedmatgozar HR, Alipour-Hafezi M, Hanafizadeh P (2015) Digital identifier systems: comparative evaluation. Iran J Inf Process Manag 30:529–552

Kaur S, Dhindsa KS (2017) Comparative study of citation and reference management tools: mendeley, zotero and read cube. In: Sheikh R, Mishra DKJS (eds) Proceeding of 2016 International conference on ICT in business industry & government (ICTBIG). Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Piscataway, NJ. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICTBIG.2016.7892715

Kratochvíl J (2017) Comparison of the accuracy of bibliographical references generated for medical citation styles by endnote, mendeley, refworks and zotero. J Acad Librariansh 43:57–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2016.09.001

Zhang Y (2012) Comparison of select reference management tools. Med Ref Serv Q 31:45–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763869.2012.641841

Hupe M (2019) EndNote X9. J Electron Resour Med Libr 16:117–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/15424065.2019.1691963

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Pharmaceutics, Manipal College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India

Usha Y. Nayak & Srinivas Mutalik

Centre for Bio Cultural Studies, Directorate of Research, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, Karnataka, India

Praveen Hoogar

Shri Dharmasthala Manjunatheshwara University, Dharwad, Karnataka, India

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to N. Udupa .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Retired Senior Expert Pharmacologist at the Office of Cardiology, Hematology, Endocrinology, and Nephrology, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD, USA

Gowraganahalli Jagadeesh

Professor & Director, Research Training and Publications, The Office of Research and Development, Periyar Maniammai Institute of Science & Technology (Deemed to be University), Vallam, Tamil Nadu, India

Pitchai Balakumar

Division Cardiology & Nephrology, Office of Cardiology, Hematology, Endocrinology and Nephrology, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD, USA

Fortunato Senatore

Ethics declarations

No conflict of interest exists.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Nayak, U.Y., Hoogar, P., Mutalik, S., Udupa, N. (2023). Writing a Postgraduate or Doctoral Thesis: A Step-by-Step Approach. In: Jagadeesh, G., Balakumar, P., Senatore, F. (eds) The Quintessence of Basic and Clinical Research and Scientific Publishing. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-1284-1_48

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-1284-1_48

Published : 01 October 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-99-1283-4

Online ISBN : 978-981-99-1284-1

eBook Packages : Biomedical and Life Sciences Biomedical and Life Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Want to Get your Dissertation Accepted?

Discover how we've helped doctoral students complete their dissertations and advance their academic careers!

Join 200+ Graduated Students

Get Your Dissertation Accepted On Your Next Submission

Get customized coaching for:.

- Crafting your proposal,

- Collecting and analyzing your data, or

- Preparing your defense.

Trapped in dissertation revisions?

External validity: everything you need to know, published by steve tippins on december 18, 2020 december 18, 2020.

Last Updated on: 29th August 2022, 08:16 am

Everybody knows external validity is important. With it, you’ll soar to the heights of research applicability. Without it, you’ll barely make it off the ground. But… what exactly is it?

Fear not: if you’re confused about what external validity is and how to achieve it, you’re in the right place. Or, if you already know what it is but haven’t the slightest clue how to actually put it into practice, we’ve got you covered too.

What Is External Validity?

When we consider external validity, we are asking whether the results of our study can be generalized beyond the scope of the study itself. Can the claim be realistically applied to larger populations, as well as to other times or situations?

When and How Is External Validity Important?

External validity is extremely important with frequency claims — studies that conclude how frequent or common something is. For example, “14% of College Students Consider Suicide” is a frequency claim. For us to take this claim seriously, we would need to know how they chose their study participants — did they ask a few students on the sidewalk? Did they ask 100 randomly chosen students across a variety of colleges?

Association claims — studies that claim that two things often occur together — also require interrogation of external validity. For example, “People Who Talk with Their Hands Are Often Warmer and Friendlier Than Those Who Don’t” is an example of an association claim. Do these results always hold true? Can a study of middle school girls in Connecticut that showed these results also hold true for a group of middle-aged men in California?

When saying one variable causes another (causal claims), we ask: to what populations, settings, and times can we generalize? For a study that claims that music lessons increase IQ, we would need to ask whether the results would apply in all cultures, for people of all socio-economic backgrounds, and at all ages. When making causal claims, however, interrogation is usually more rigorously focused on internal validity.

What’s the Difference Between External and Internal Validity?

Internal validity refers to the construction of the study and means that conclusions are warranted, extraneous variables are controlled, alternative explanations are eliminated, and accurate research methods were used.

External validity means the degree to which findings can be generalized beyond the sample, the outcomes apply to practical situations, and that the results can be translated into another context.

An Oregon State University researcher talks about the difference in practice:

In some more recent work, I was looking specifically at physical activity during pregnancy as the only exposure; thus, my advertisement to recruit women into the study mentioned that I was studying exercise in pregnancy (rather than pregnancy in general). [1] In this more recent study, I had very few sedentary people—indeed, I have a few who reported running half marathons while pregnant! Since this is not normal, my study—though it does have reasonable internal validity—cannot be generalized to all pregnant women but only to the subpopulation of them who get a fair bit of physical activity. It lacks external validity. Because it has good internal validity, I can generalize the results to highly active pregnant women—just not to all pregnant women.

Threats to External Validity

In order for your research to apply to other contexts (and thus be of use to anyone), it’s important to manage or eliminate threats to external validity. Here are some of the most common threats.

Sampling Errors

Polling during political campaign season offers a vivid example of the importance of sampling for predicting the behavior of a population: “Can we predict the results of the presidential election based on this sample of 1200 people?”

You’ll want to know if the sample comes from the population of interest , so you’ll want to define that first. Pollsters don’t ask children who they’d vote for, because children are not allowed to vote — they are not representative of the population of interest.

You’ll also need to be sure that the sample is representative of the population . Polls that sample only adult white males would be unlikely to accurately predict the election because they do not adequately represent the diversity of the voting population.

Special Circumstances

You also want to make sure major historical events do not influence the results of your study. For example, doing your study during a global pandemic. Does the pandemic have any influence on your results?

Or, if you planned to survey people over a time period (say, three months) and two months into the process, there’s a big change in society or within the profession, that might make your results have less external validity. Because some of the responses came before the major event and some came after, it’s hard to tell the impact the event had on the results.

Hack Your Dissertation

5-Day Mini Course: How to Finish Faster With Less Stress

Interested in more helpful tips about improving your dissertation experience? Join our 5-day mini course by email!

How to Achieve External Validity

Larger, representative sample.

Sample size is always a trade-off. Dedicating time and money needed to accumulate a large sample increases external validity, but a smaller sample allows for faster completion with fewer resources. Most people do a G*Power test, when doing a quantitative study, to determine the minimum sample size that’s needed to allow for external validity.

You want the sample to be large enough to sufficiently limit the influence of outliers. In a larger sample, someone offering unrepresentative views/behavior will not skew the results. For example, in a study where 4 people are asked how many doughnuts they can eat and 3 eat 2 doughnuts and 1 eats 34, the average is 10 doughnuts per person. However, if 1,000 people are surveyed and 999 eat 2 doughnuts and 1 eats 34 the average is 2.032. The outlier does not skew the results much.

Random samples are considered more valid than purposive samples, because you have a better chance of representing the population randomly than if you select who will be part of the study, or if they volunteer.

Replicability

If your study is set up so that others can repeat your study, then results have the potential to become much more externally valid. If others repeat the study and come up with similar results, that means your findings might actually be the case generally. If you replicate your own study under different circumstances or with different populations, you have more results to make your conclusion stronger.

Final Thoughts

External validity is an important concept to understand. A lack of understanding may doom your study, while strong external validity makes getting your dissertation accepted and/or article much easier to get published.

Steve Tippins

Steve Tippins, PhD, has thrived in academia for over thirty years. He continues to love teaching in addition to coaching recent PhD graduates as well as students writing their dissertations. Learn more about his dissertation coaching and career coaching services. Book a Free Consultation with Steve Tippins

Related Posts

Dissertation

What makes a good research question.

Creating a good research question is vital to successfully completing your dissertation. Here are some tips that will help you formulate a good research question. What Makes a Good Research Question? These are the three Read more…

Dissertation Structure

When it comes to writing a dissertation, one of the most fraught questions asked by graduate students is about dissertation structure. A dissertation is the lengthiest writing project that many graduate students ever undertake, and Read more…

Choosing a Dissertation Chair

Choosing your dissertation chair is one of the most important decisions that you’ll make in graduate school. Your dissertation chair will in many ways shape your experience as you undergo the most rigorous intellectual challenge Read more…

Make This Your Last Round of Dissertation Revision.

Learn How to Get Your Dissertation Accepted .

Discover the 5-Step Process in this Free Webinar .

Almost there!

Please verify your email address by clicking the link in the email message we just sent to your address.

If you don't see the message within the next five minutes, be sure to check your spam folder :).

- Open access

- Published: 07 September 2023

Validity, acceptability, and procedural issues of selection methods for graduate study admissions in the fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics: a mapping review

- Anastasia Kurysheva ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7425-1345 1 , 2 ,

- Harold V. M. van Rijen 1 , 2 ,

- Cecily Stolte 1 , 2 &

- Gönül Dilaver ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6227-2197 1 , 2

International Journal of STEM Education volume 10 , Article number: 55 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

2128 Accesses

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

This review presents the first comprehensive synthesis of available research on selection methods for STEM graduate study admissions. Ten categories of graduate selection methods emerged. Each category was critically appraised against the following evaluative quality principles: predictive validity and reliability, acceptability, procedural issues, and cost-effectiveness. The findings advance the field of graduate selective admissions by (a) detecting selection methods and study success dimensions that are specific for STEM admissions, (b) including research evidence both on cognitive and noncognitive selection methods, and (c) showing the importance of accounting for all four evaluative quality principles in practice. Overall, this synthesis allows admissions committees to choose which selection methods to use and which essential aspects of their implementation to account for.

Introduction

A high-quality student selection procedure for graduate level education is of utmost importance for programs, students, and society. Higher education has seen several influential policy developments over the past decades such as the introduction of the Bologna Process in 1999 in Europe and the increased internationalization of higher education across the globe (De Wit & Altbach, 2020 ). These policies contributed to rising international/cross-border and national (i.e., between higher education institutions within one country) student mobility (Okahana & Zhou, 2018 ; Payne, 2015 ). The knock-on effect of this mobility has created a growing diversity of graduate application files. Admissions committees are now faced with applicants from different higher education systems, potentially a variety of background fields, and varying levels of academic skills and proficiency in the language of instruction.

Furthermore, the problem of underrepresentation of students with certain backgrounds persists across the globe, including countries with well-developed higher education systems (Salmi & Bassett, 2014 ). As such, it is still more difficult for students with low socioeconomic status (SES), a migration background, those who are first-generation students, or students with disabilities to gain admissions into higher education programs compared to students with middle/high SES, no migration background, parents who hold academic degree, or students without disabilities (Garaz & Torotcoi, 2017 ; Salmi & Bassett, 2014 ; Weedon, 2017 ). Students’ application files are often conditioned by their background: For example, students with parents of low SES cannot typically show an impressive list of extracurricular activities on their resume in contrast to their peers with parents of high SES (Jayakumar & Page, 2021 ). Since these factors contribute to the inequality already at the entrance to higher education—at the undergraduate level (Zimdars, 2016 ), they may further exacerbate their effects in the selective graduate level of education, where there are even fewer places available. It is, therefore, often the case that a straightforward assessment of application files is not feasible because of the multifaceted nature of each application. Unsurprisingly, it is a complex task for admissions committees to evaluate the educational background and achievements of (inter)national students with diverse backgrounds. Regardless of described complexities, admissions decisions must be objective, fair, and transparent to ensure their adequate justification.

Evaluative quality principles

To facilitate the achievement of the overarching goals of objectivity, fairness, and transparency, four evaluative quality principles regarding student selection methods were recognized as essential (Patterson et al., 2016 ):

Effectiveness combines both (predictive) (incremental) validity and reliability. This principle encompasses several questions that should ideally be considered together: Does a selection method predict study success and to what extent? Even if a selection method does predict study success, does it provide additional value beyond other valid selection methods? Does the use of a selection method deliver consistent results across time, locations, and assessors?

Procedural issues of a selection method refer to any aspects that are important in the practical implementation of the method such as its limitations, the impact of its structure and format on its effectiveness, any biases that are naturally integrated into its design etc.

Acceptability refers to both the willingness to implement a selection method and the satisfaction of stakeholders from its usage. Relevant questions in this regard are: How widely is the selection method used across different disciplines, countries, and regions? To what extent are admissions committees willing to apply the method? Do they find it useful? Finally, how much do applicants favor the selection method?

Cost-effectiveness is a quality evaluative principle that refers to the financial impact of a selection method on educational programs and applicants. In other words, it refers to the questions: Who pays for its usage in the admissions process, and how much does it cost?

There is a striking lack of studies that synthesize research evidence on selection methods for graduate study admissions while accounting for all four evaluative quality principles. Instead, the existing reviews and meta-analyses address evidence for each selection method separately: standardized testing (Kuncel & Hezlett, 2007b , 2010 ; Kuncel et al., 2004 , 2010 ), recommendation letters (Kuncel et al., 2014 ), personal statements (Murphy et al., 2009 ), and other various noncognitive measures (Kuncel et al., 2020 ; Kyllonen et al., 2005 , 2011 ; Megginson, 2009 ). Moreover, these studies usually focus on predictive validity and rarely on procedural issues, with only limited or no attention to reliability, acceptability, and cost-effectiveness.

The only review to combine evidence on all available selection methods within one study and included the four evaluative quality principles (validity/reliability, procedural issues, acceptability, and cost-effectiveness) was conducted by Patterson et al. ( 2016 ). However, this review only focused on selection methods in medical education. For example, it does not present evidence on (nonmedical) standardized tests of academic aptitude, tests of language of instruction, or amount and quality of prior research experience. Therefore, its findings can only be partially generalized for graduate admissions.

The question that arises is which educational field (except medical education) has attracted enough high-quality research that (a) addresses the four evaluative quality principles and (b) allows admissions committees to use the findings in a wide range of graduate programs, therefore, enhancing the potential impact of this review? From the preliminary overview, we think that science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields meet these two conditions. STEM fields have been recognized worldwide as fundamental for finding solutions to urgent societal problems (Proudfoot & Hoffer, 2016 ). The efforts of certain countries to become leaders in STEM higher education and research (e.g., China; Kirby & van der Wende, 2019 ) are illustrative of how crucial the STEM fields are for economic growth and prosperity. Unsurprisingly, STEM disciplines have attracted a rising number of students, making research evidence on selection methods for STEM studies increasingly more relevant. Since there has been no synthesis of such evidence to date, we designed this review to address this gap.

The present review

The aim of this review is to present a comprehensive overview of research evidence on the existing selection methods in graduate admissions in STEM fields. The review focuses on evaluative quality principles of validity, reliability, procedural issues, acceptability, and cost-effectiveness. The term “graduate” refers to both master’s and doctoral levels. That is, studies on both levels were collected for this review.

Research questions

What evidence is provided in research literature within STEM graduate admissions field on:

the extent to which different selection methods are valid and reliable?

procedural issues of the selection methods?

the extent to which different selection methods are accepted by stakeholders?

the extent to which different selection methods are cost-effective?

For this review, a systematic search was conducted and complemented with an expanded search of literature in reference lists of relevant books and articles.

Inclusion criteria for the literature review

The inclusion criteria for this review were: (1) the topic on selection methods in graduate admissions, (2) the graduate level of education (i.e., master’s and/or PhD phase), (3) samples that include students from STEM disciplines, (4) studies addressing at least one of four evaluative quality principles of interest: validity/reliability, procedural issues, acceptability, and cost-effectiveness, (5) studies conducted in at least one of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, (6) studies published in English, (7) studies that went through a peer-review process, (8) studies conducted in the period between 2005 and June 2023.

The OECD countries were chosen because of their well-developed higher education systems as well as an expectation that the quality of research in these countries is comparable. The time frame was chosen in accordance with the changes in European higher education systems after the introduction of the Bologna Process (The Bologna Declaration, 1999 ). Countries joined the process in different subsequent years. Therefore, 2005 was chosen as a plausible cut-off moment to account for the fact that the first students, studying within the new system, could graduate. The same time frame was applied for the US research context.

We chose to review the literature, referring to master’s and PhD levels together (that is, on a graduate level overall), because the training on both levels is advanced. Furthermore, many studies that were included in this review did not make a distinction between the two levels. We also considered different STEM majors or contexts (e.g., the European vs. the US contexts) together, because we aimed to detect overarching patterns in evaluative quality principles that would be applicable to a variety of majors and higher education contexts on a graduate level.

The literature search procedure

The literature search delivered 3244 potentially relevant items including duplicates. The main portion of the results was obtained via conducting a systematic search in the specialized databases (ERIC: n = 1089; PsycInfo: n = 1112; Medline: n = 234; Scopus: n = 649). The keywords of the systematic search can be found in Additional file 1 : Table S1. The syntax for each database is available upon request. While we did not have the opportunity to carry out searches in all specific databases for each STEM education field (e.g., databases focusing on engineering education), we expect that the large educational data bases such as ERIC contain a substantial number of studies related to our topic in each of those fields. Next, the literature search was extended beyond the database approaches. Namely, the citations from relevant articles were examined ( n = 71), and previously collected research literature was added ( n = 89). The screening was conducted in two steps. In the first step, the titles and abstracts were scanned to remove duplicates and obviously irrelevant search results. In the second step, the full texts of remaining articles were obtained and examined. The full texts of four articles were not found even after contacting the authors and were not included in the final number.

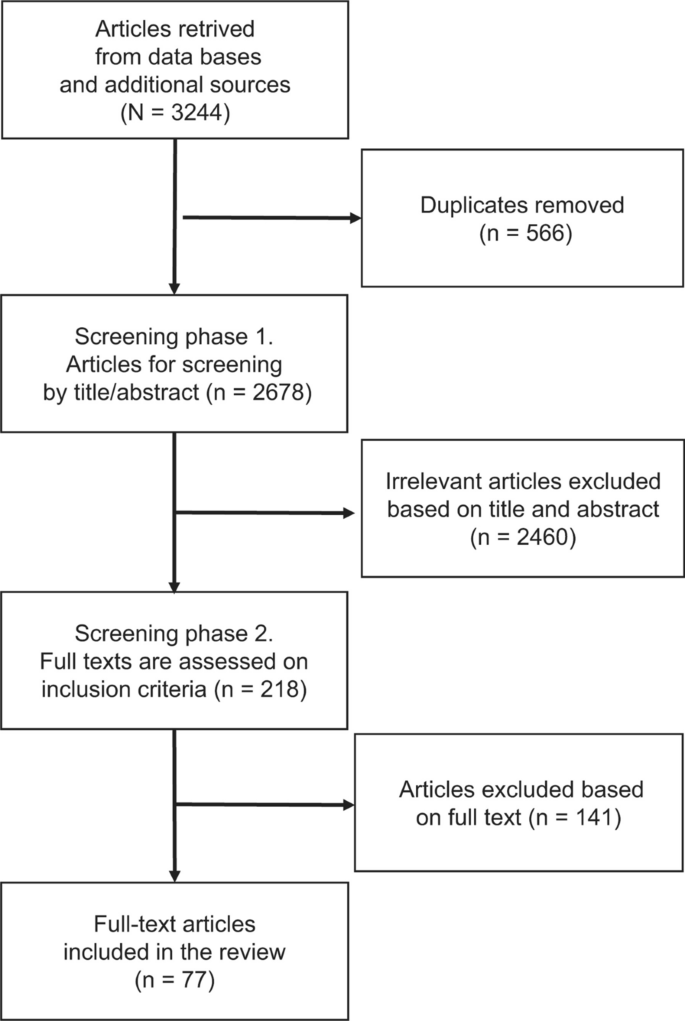

Figure 1 presents a detailed flowchart of the steps undertaken. Two coders (the first and the third authors) conducted both steps of screenings. To ensure that the same papers were selected, both coders screened all papers at both steps according to the inclusion criteria. They used codes, such as “yes”, “no”, and “may be”, with the later meaning that an article required a joint decision during the discussion. All papers were independently screened by the two coders during both steps. Although the agreement after the first screening was near complete (kappa = 0.88) and that of the second screening was strong (kappa = 0.70), there were papers with different codes (e.g., “yes” and “may be”, or more rarely “yes” and “no”) or about which the coders had doubts (a code of “may be”). All such disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Flowchart of articles’ selection

In total, 77 articles met the inclusion criteria for this review. The distribution across the OECD countries is presented in Table 1 . The distribution across STEM disciplines is presented in Table 2 .

After the screening was completed, the graduate selection methods from 77 studies were assigned into ten categories: (1) prior grades, (2) standardized testing of academic abilities, (3) letters of recommendation, (4) interviews, (5) personal statements (i.e., motivation letters), (6) personality assessments, (7) intelligence assessments, (8) language proficiency, (9) prior research experience, and (10) various, rarely studied selection methods that do not fall under more common methods above (such as resumes, selectivity of prior higher education institution (HEI), former (type of) HEI, amount and quality of research experience, or composite scores). If one study addressed different methods or evaluative quality principles, that study was included in all respective categories. The numbers of papers cross-tabulated according to selection method and evaluative quality principle are presented in Additional file 1 : Table S2. Additional file 1 : Table S3 shows the main characteristics of studies, such as study design, country, field of study, and so forth. Additional file 1 : Table S3 also includes the summary of the relevant findings per study.

Contributions of this review

The main contribution of this review is that it synthesizes high-quality research evidence across four evaluative quality principles, as proposed by Patterson et al. ( 2016 ), for both cognitive and noncognitive selection methods. No such synthesis has been conducted in the field of STEM graduate admissions (For an overview of the assessment of only noncognitive constructs in graduate education, one may consult the papers of de Boer and Van Rijnsoever, 2022a ; Kyllonen et al., 2005 , 2011 ). Another strong aspect of this review is that it compares the findings of primary and secondary (i.e., reviews, meta-analyses) studies, wherever possible. This is important considering possible limitations of primary studies, such as range restriction and criteria unreliability, which can be accounted for in meta-analyses (Sedlacek, 2003 ). Overall, this review aims to provide a compilation of state-of-the-art research on selective graduate admissions in STEM fields of study.

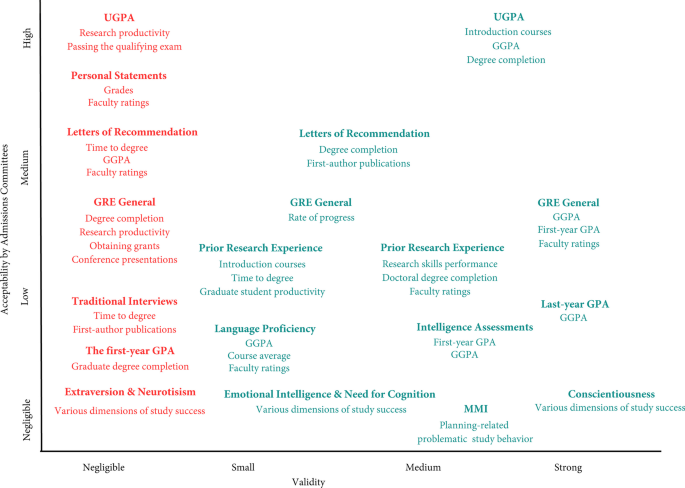

Additional file 1 : Table S2 shows the numbers of articles on each selection method and evaluative quality principle. We note the overall lack of research on the topics of reliability and cost-effectiveness. Therefore, the evidence below is presented mostly on validity, acceptability, and procedural issues. When studies on reliability or cost-effectiveness are available, they are reported in the respective selection methods’ categories.

Prior grades

Validity and reliability of prior grades.

The research focused on exploring the predictive validity of different aspects of grade point average (GPA), such as undergraduate GPA (UGPA), the first-year GPA, and the last-year GPA. Findings and relevant references are presented in Table 3 . Overall, it appears that UGPA is a valid predictor of graduate degree completion, student performance on introductory graduate courses, and graduate GPA (GGPA). However, UGPA is not valid for predicting research productivity (defined as number of published papers, presentations, and obtained grants) and passing qualifying exams. There is mixed evidence on predictive validity of UGPA toward time to graduate degree and faculty ratings.

Some single studies looked at UGPA in more detail. Namely, they disentangled UGPA on first-year UGPA and last-year GPA. A study that tried to predict graduate degree completion with first-year UGPA found no such relationship (DeClou, 2016 ). A study that explored the predictive validity of last-year UGPA found that last-year GPA is positively related to GGPA (Zimmermann et al., 2017a ).

We found one study that addressed the question of reliability estimates. The author calculated eight different reliability coefficients for fourth-year cumulative GPA at each higher education institution included in the study and then meta-analyzed them (Westrick, 2017 ). The study showed that the various reliability estimates ranged between 0.89 and 0.92. The author recommends using stratified alpha as a reliability coefficient for cumulative GPA, which works best with the multi-factor data, due to the variation in the processes involved in earning grades in the first-year and fourth-year courses (Westrick, 2017 ).

Procedural issues of prior grades

There are several procedural issues with using prior grades for admissions decisions. The first one is grade inflation—a practice of awarding higher grades than previously assigned for given levels of achievement (Merriam-Webster dictionary, n.d. ): For example, teachers giving higher grades for positive student ratings (European Grade Conversion System [EGRACONS], 2020 ). In her observational study of top graduate research programs, Posselt ( 2014 ) indicated that grade inflation is a widespread phenomenon in highly selective universities. In such universities, students from underrepresented backgrounds are extremely lacking; therefore, setting a grade-threshold on a high level disproportionately excluded these students (Posselt, 2014 ).

The second one refers to differences in grading standards, which relates to the fact that one grade obtained at different institutions might reflect a different level of academic qualification. Grade conversion and grade distribution tables, which are developed to tackle these issues, are not without limitations. They can often be crude, and this can affect both selection decisions and research done on grades as predictors of graduate study success (see, e.g., Zimmermann et al., 2017a ).

The third procedural issue relates to a possibility of cognitive biases of assessors to influence grading: This could be an origin of differences in prior grades observed between applicants with various socioeconomic status (SES), genders, and races (Woo et al., 2023 ). Finally, the relatedness, or fit, between undergraduate and graduate programs affects the predictive value of grades received during undergraduate studies: When the programs are related to a high extent, the relationship between undergraduate and graduate grades is stronger compared to a situation when the undergraduate and graduate programs are related to a low extent (de Boer & Rijnsoever, 2022b ).

Acceptability of prior grades

Prior grades are a widely accepted selective admissions method (Boyette-Davis, 2018 ; MasterMind Europe, 2017 ). The largest weight in admissions decisions is given to grades on undergraduate courses that are closest in terms of content to the courses of a graduate program (Chari & Potvin, 2019 ). When explaining what the reasons are behind high acceptability of grades and even overestimation of their importance in graduate admissions by admissions committees, Posselt ( 2014 ) states that high conventual achievements, such as grades, are consistent with the identity of an elite intellectual community, which admissions committee members, implicitly or explicitly, refer themselves.

Standardized testing of academic abilities

Validity of standardized admissions tests of academic abilities.

Among different standardized admissions tests, the ones which are typically required for selective admissions to graduate programs in STEM disciplines are the Graduate Record Examinations (GRE) General and GRE Subject. All but one study, which addressed validity of standardized tests, referred to these two GRE tests. The only exception was the standardized test EXANI-III, which is used in Mexico.

Validity of graduate standardized admissions tests has been a controversial topic in research, with some studies providing evidence for their weak-to-moderate predictive power toward graduate study success and others indicating the absence of predictive power (see Table 4 ). From Table 4 , we can infer that the standardized test most often examined is the GRE General.

The GRE General is a positive predictor of first-year GGPA, GGPA, and faculty ratings. This is in line with the existing reviews and meta-analyses (Kuncel & Hezlett, 2007b , 2010 ; Kuncel et al., 2010 ). From the majority of primary studies, it appears that the GRE General does not predict graduate degree completion and research productivity defined as the number of publications.

The meta-analyses on the topic, however, found that after meta-analytical corrections for statistical artifacts in primary studies were applied (such as a correction for the restriction of range of a predictor), these two relationships (1) between the GRE General and degree completion and (2) between the GRE General and research productivity, although weak, were detected (Kuncel & Hezlett, 2007a , 2007b ).