Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Syntax at Hand: Common Syntactic Structures for Actions and Language

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliations L2C2- Institut des Sciences Cognitives, CNRS UMR 5304, Bron, France, Université Claude Bernard Lyon I, Lyon, France

Affiliations L2C2- Institut des Sciences Cognitives, CNRS UMR 5304, Bron, France, Centre de Référence «Déficiences Intellectuelles de Causes Rares» Hôpital Femme Mère Enfant, Hospices Civils de Lyon, Bron, France, Université de Lyon, Faculté de Médecine Lyon Sud - Charles Mérieux, Lyon, France

Affiliations L2C2- Institut des Sciences Cognitives, CNRS UMR 5304, Bron, France, Université Claude Bernard Lyon I, Lyon, France, Centre de Référence «Déficiences Intellectuelles de Causes Rares» Hôpital Femme Mère Enfant, Hospices Civils de Lyon, Bron, France, Université de Lyon, Faculté de Médecine Lyon Sud - Charles Mérieux, Lyon, France

Affiliations L2C2- Institut des Sciences Cognitives, CNRS UMR 5304, Bron, France, Université Claude Bernard Lyon I, Lyon, France, Service de Psychopathologie du Développement- Hôpital Femme Mère Enfant, Hospices Civils de Lyon, Bron, France, Université de Lyon, Faculté de Médecine Lyon Sud - Charles Mérieux, Lyon, France

- Alice C. Roy,

- Aurore Curie,

- Tatjana Nazir,

- Yves Paulignan,

- Vincent des Portes,

- Pierre Fourneret,

- Viviane Deprez

- Published: August 22, 2013

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0072677

- Reader Comments

Evidence that the motor and the linguistic systems share common syntactic representations would open new perspectives on language evolution. Here, crossing disciplinary boundaries, we explore potential parallels between the structure of simple actions and that of sentences. First, examining Typically Developing (TD) children displacing a bottle with or without knowledge of its weight prior to movement onset, we provide kinematic evidence that the sub-phases of this displacing action (reaching + moving the bottle) manifest a structure akin to linguistic embedded dependencies. Then, using the same motor task, we reveal that children suffering from specific language impairment (SLI), whose core deficit affects syntactic embedding and dependencies, manifest specific structural motor anomalies parallel to their linguistic deficits. In contrast to TD children, SLI children performed the displacing-action as if its sub-phases were juxtaposed rather than embedded. The specificity of SLI’s structural motor deficit was confirmed by testing an additional control group: Fragile-X Syndrome patients, whose language capacity, though delayed, comparatively spares embedded dependencies, displayed slower but structurally normal motor performances. By identifying the presence of structural representations and dependency computations in the motor system and by showing their selective deficit in SLI patients, these findings point to a potential motor origin for language syntax.

Citation: Roy AC, Curie A, Nazir T, Paulignan Y, des Portes V, Fourneret P, et al. (2013) Syntax at Hand: Common Syntactic Structures for Actions and Language. PLoS ONE 8(8): e72677. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0072677

Editor: Corrado Sinigaglia, University of Milan, Italy

Received: November 29, 2012; Accepted: July 18, 2013; Published: August 22, 2013

Copyright: © 2013 Roy et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: This work has been supported by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and ACR and PF were additionally supported by Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and Agence Nationale pour la Recherche Samenta (ANR-12-SAMA-015-02). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The nature of the relationships between language and motor control is currently the object of growing attention [ 1 ]. Up to now, however, empirical research has largely centered on the meaning of action words and their representation in our sensory and motor systems [2 for a review]. With their focus on the lexico-semantic domain, these studies have rarely addressed other core aspects of language such as its structural aspects and its syntax. Yet, the common involvement of Broca’s area in syntax and in the sensori-motor system points to possible convergence between these domains [ 3 , 4 ]. Positive evidence that syntax-based representations could be partially common to the motor and the linguistic systems would suggest that linguistic syntax could have exploited and built upon parts of a pre-existing “syntax” used by the motor system [ 5 – 7 ]. The present study provides support for this assumption.

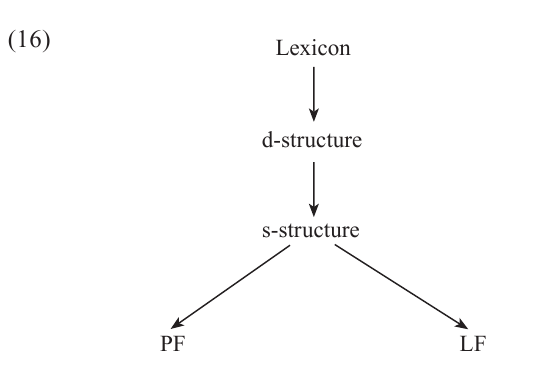

Like verbs in spoken language, actions arguably manifest a comparable argument structure relating agents and objects [ 8 ]. Accordingly, they are commonly branded as ‘transitive’ when performed with or towards objects [ 9 ]. Knott [ 10 ] for instance, proposes that "the Logical Form" of a sentence reporting a cup-grabbing episode can be understood as a description of the sensorimotor processes involved in experiencing the episode. He argues that the LF of the sentence can be given a detailed sensorimotor characterization, and that many of the syntactic principles are actually sensorimotor in origin.

Similarly, drawing on modeling studies of motor planning, Jackendoff [ 11 , 12 ] suggested that actions are recursively structured in ways quite analogous to the hierarchical embedding that characterizes language syntax and further conjectured that the structure of certain sub-events within goal-oriented actions (e.g. preparing coffee) could even have "the flavor of variable binding and long distance dependencies" [12 p597] like those at play in the syntactic structures of questions or relative clauses. Jackendoff [12 p597] describes one such dependencies in the complex routine action of making coffee as follows: "For instance, suppose you go to take the coffee out of the freezer and discover you’re out of coffee. Then you may append to the [making coffee] structure a giant preparation of buying coffee, which involves finding your car keys, driving to the store, going into the store (…) and driving home. The crucial thing is that in this deeply embedded head (i.e. the buying action), what you take off the shelf (...is...) the same thing you need in the larger structure this action is embedded in".

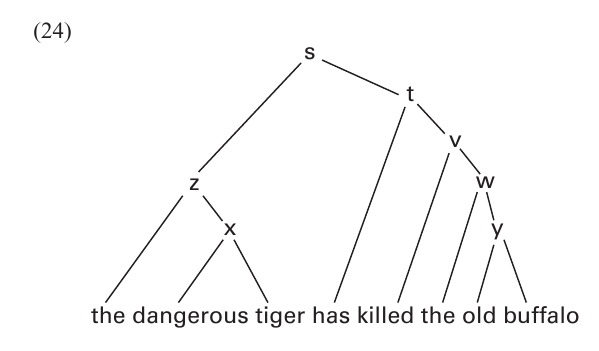

Consider now in some detail the syntactic structure of a relative clause dependency in language. In a simple sentence like [ John grasped the bottle ], the complement of a transitive verb like “ grasped ”, i.e the nominal phrase [ the bottle ], generally occurs after the verb. In contrast, in a relative clause like ‘ [ This is the bottle (which) John grasped ] the nominal phrase [ the bottle ] is syntactically displaced to the front of the clause, so that it no longer appears after the verb. Yet, despite this displacement, the nominal phrase remains interpreted as the complement of the verb “ grasped ”. In syntactic theory, the link between the displaced position of a fronted nominal phrase and the position in which it is interpreted (i.e. here as a complement of the verb grasp) is modeled as a ‘distant dependency’ between the two syntactic positions of the nominal phrase. Syntacticians propose that a relative clause is a transform of a basic sentence in which the nominal complement of a verb has been displaced to the front of a clause leaving a silent copy in the position in which it originated and is interpreted e.g. [ This is the bottle (which) John grasped the bottle ]. Schematically, the abstract structure of a relative clause is as in Figure 1 : Here, S’ represents the relative clause, S, the original sentence, the arrow indicates the displacement i.e. the distant dependency between the nominal phrase (NP) and its silent copy represented here as the crossed NP : the bottle .

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

The noun phrase "the bottle" appears twice, once when it is pronounced at the beginning of the main clause and as a trace in the position it is interpreted in i.e. as the object complement of the verb grasp of the relative clause. Note that this structure is characteristically asymmetric.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0072677.g001

‘Distant dependencies’ are also known in linguistics as filler-gap dependencies or operator-variable dependencies. All these dependencies involve relations akin to that between a noun and a pronoun that is two representations of the same element as in: (John thinks he will win, where ‘he’ = john) but where the pronoun is silent. ‘Distant dependencies’ have played a central role in linguistic theory in probing the hierarchical nature of sentence embedding [ 13 ]. As Ross [ 14 ] showed indeed, these dependencies are tightly constrained. In particular, although the distance between the displaced nominal phrase and its silent copy can span over several clauses if these are embedded, the dependency fails to be properly interpreted if the intervening clauses are coordinated or juxtaposed instead. Compare the following examples:

- (a). This is the heavy bottle (which) [John realized] (that) [Mary knows] (that) [he grasped [the bottle]]

(b). * This is the heavy bottle (which) [John smiled] (and) [Mary stretched] and [he grasped [the bottle]]

Please note that the asterisk in front of the sentence indicates that the sentence in (b) is ungrammatical and that the elements in parenthesis are optional in English. They can remain unpronounced so that respectively the two sentences can be realized as:

This is the heavy bottle John realized Mary knows he grasped vs. This is the heavy bottle John smiled Mary stretched and he grasped. In (a), the dependency between the fronted nominal phrase, the bottle and the position in which it is interpreted (e.g. as a complement of the verb grasp) spans over three embedded clauses, but the sentence is still natural. In (b) -though formed from the perfectly accep It should be noted that we are not claiming that motor syntax is as complex as linguistic syntax, nor that it shares all of its crucial aspects, but we are arguing that some rudimentary, but fundamental aspect of linguistic syntax could be traced back to relatively complex motor actions. sentence "John smiled and Mary stretched and he grasped the heavy bottle"- it is rather difficult to understand the fronted nominal phrase [ the bottle ] as the complement of the verb grasp and still obtain a fully natural sentence. Note that the actual linear distance between the fronted noun phrase and the silent copy [ the bottle ] after the verb grasp is the same in (a) and (b). What differs is the nature of the syntactic relationship that the intervening clauses entertain: embedded vs. coordinated. That is, what matters is the nature of the abstract structural relation that connects the components that intervene between the two pieces of the distant dependency, the nominal phrase and its silent copy. Hence, the break down of the distance dependency in (b) vs. (a) serves to reveal a fundamental distinction in the syntax of these two sentences that would otherwise not be immediately obvious from the simple sequential ordering of their components. The distinction in the structural relations between the component constituents is schematized in Figure 2 .

A: An embedded structure is essentially asymmetric and accepts distance dependency as in the example given in (a). By contrast a symmetric coordinated structure does not accept distance dependency.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0072677.g002

As the arrows indicate, a linguistic distant dependency can succeed when the intervening components are embedded, but it breaks down when they are coordinated or juxtaposed. This structural constraint, dubbed the "Coordinated Structure Constraint" in the linguistic literature, provides evidence of the fundamentally hierarchical and embedded nature of certain linguistic structures.

Following Jackendoff’s conjecture that comparable distant dependencies are found in the motor domain, we sought to use these to experimentally probe the nature of the abstract structural relations that connect the motor components of a transitive action.

Endeavoring to construct an analogous motor distant dependency, we used a basic goal-directed displacing-action task that consisted in reaching a bottle and moving it to another target location while manipulating the participant’s knowledge of its weight. Our task was designed, first, to build on existing evidence that a displacing motor action can be divided in two component sub-phases [ 15 ], a first sub-phase of [reach+grip] that unfolds before object contact, dubbed here the Reach sub-phase, and a second sub-phase of [lift+move] that unfolds after object contact, dubbed here the Move sub-phase ( Figure S1 ). Second, we chose to manipulate the weight of an opaque bottle because, in contrast to features such as shape, size or location, which are visually perceived and hence can come to affect the kinematics of a reach and grasp action before any object contact [ 16 ], weight is a somatosensory perception that affects movement kinematics only after object contact [ 17 – 19 ] as long as there are no visual (or other) cues to it. That is, weight information, is normally "encapsulated" in the second phase of a displace action, i.e. dubbed here the Move sub-phase. Yet, weight information could become accessible prior to object contact [e.g. 20-22], if the weight of a given object is experienced or known before critical movement onset. When known, weight information could be so to speak ‘raised out’ of the Move sub-phase where it is normally encapsulated, and become accessible to potentially affect kinematic parameters already in the Reach sub-phase. Such a displaced weight effect in the Reach sub-phase would form the motor equivalent of a ‘distant dependency’ between the point in the Reach sub-phase where the mental representation of object weight is integrated in movement kinematics and the point of object contact in the Move sub-phase where the object weight is physically accessed. Note that at this second point in the action structure i.e. at the point of contact, the pertinent object weight better matches the representation integrated earlier in the Reach component, or else a mismatch would occur. This implies that a representation of object weight must be part of the motor computation to allow a backward feedback similar to the relation posited in linguistics between a displaced nominal phrase and its silent copy.

Although there is a rather broad consensus in the motor literature that a simple object displacing action of the type we used can be subdivided into two distinctive sub-components [ 15 ], the nature of the structural relation between these two components has at this point not been investigated empirically. A priori, the two sub-phases of a displacing action could be structurally related in either of two ways: they could be merely sequentially juxtaposed in analogy with the coordinated linguistic structures in Figures 2 and 3A-B or entertain a complex hierarchical relation, a form of syntactic embedding, analogous to the embedded structure in Figures 2 and 3C-D . This subtle but key distinction is essential for comparing motor with linguistic structure because in language, as illustrated in Figure 2 , the two types of structural relations have characteristically distinct effects on distant dependencies. While juxtaposed constituents are largely independent from one another, i.e. there have no domination or inclusion relation, embedded constituents are hierarchically related and thus asymmetrically dependent with domination or inclusion relations. Manipulating access to object weight information, during or prior to action execution, by creating a distant dependency, allows us to probe the structural relation entertained by the two component sub-phases of a displacing action. When the weight of an object is unknown to the subject, the kinematic parameters should always adjust to weight after object contact, that is, in the Move sub-phase only: such cases, then do not afford the possibility to uncover a distinction between the two potential structural models for our displacing action depicted in Figure 3 . However, when the object-weight is known in advance, so that a potential distant dependency now arises between a motor weight representation before object contact and the point of object contact where weight is physically felt, the two models make different predictions. If the displacing-action has a juxtaposed structure (with two relatively independent and parallel sub-components), weight effects could be distributed over and affect the kinematic parameters of both sub-components symmetrically (red line in Figure 3 ) in analogy with what happens in a linguistic coordinated structure as the following (e.g. the heavy/light bottle, I reach it AND I move it) where the fronted nominal complement ‘[the heavy/light bottle] is resumed by an overt pronoun (it) in both constituents of the coordinated structure. That is, if the structure of the displacing action is as in Figure 3B , we expect weight to affect both the Reach sub-phase as the weight representation is accessible to affect the kinematic computation, and the Move sub-phase as this is where the object weight is actually felt. By contrast, if the two components of the displacing action are embedded and object properties computation is akin to a linguistic distant dependency, as we conjecture, prior weight knowledge could result in an asymmetric transfer of the weight effects to the topmost level of the hierarchical structure, i.e., to the ‘Reach sub-phase’ with a consequent reduction or absence of weight effects in the ‘Move sub-phase’ in analogy with the silent copy that a linguistic dependency leaves in the original complement position when a nominal phrase is displaced (e.g. the heavy/light bottle which I reach to move [the bottle]). In similarity with linguistic displacement, object weight effects could be so to speak ‘raised out’ of the Move sub-phase and be displaced to affect the Reach sub-phase, leaving in turn the kinematics parameters of the lower Move sub-component unaffected by weight, in analogy with the linguistic silent copy left after fronting in relative clauses [ 23 ].

AB: Sequential juxtaposition, analogous to [I reach-grip a bottle AND lift-move it]. When object weight is unknown prior to object contact (A), kinematic parameters adapt to object weight in the ‘Move sub-phase’ (schematically indicated by the red line). No effect of object weight is expected in the ‘Reach sub-phase’. By contrast, when object weight is known in advance (B), movement kinematics could differ for heavy and light objects conjointly in the ‘Reach sub-phase’ and the Move sub-phase i.e. [This heavy bottle, I reached-griped it AND lift-moved it]. CD: Syntactic embedding, analogous to [I reach-grip a bottle TO lift-move it]. When object weight is unknown kinematic parameters adapt to object weight in the ‘Move sub-phase’ only (C). When known prior to movement onset object weight effects could be front-moved from the Move sub-phase to the reach sub-phase(D), following this displacement the Move sub-phase kinematics would remain immune to object weight effects (i.e., [The heavy bottle that I reached-griped TO lift-move]).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0072677.g003

To test this hypothesis and probe the structural relation of the motor components of a simple structured action, we compared the behavior of Typically Developing (TD) children with that of children diagnosed with Specific Language Impairment (SLI). SLI refers to a deficit in language acquisition that occurs in children who are otherwise developing normal cognitive abilities (absence of mental retardation, no diagnosed motor deficit, no hearing loss, or identifiable neurological disease). We reasoned that if the two sub-components of our displacing action presented a hierarchical structure rather than a mere juxtaposition, SLI patients whose core deficit has been shown to affect among other complex hierarchical sentences and, even more specifically, relative clause structures [ 24 – 27 ] may present a parallel deficit in performing a structured motor action. Such evidence would support the hypothesis that motor control and syntax could share analog mechanisms, possibly grounded in common neural structures. Both groups of children were asked to displace one of two identically looking opaque bottles with a significant weight difference (50g vs. 500g). The bottle was placed at a fixed distance from the participants’ hand, under two weight-knowledge conditions: one in which the weight was unknown prior to movement execution (Unknown condition) and one in which weight was known in advance (Known condition). Participants were first familiarized with the two object weights to ensure they had acquired sensorimotor knowledge of each before kinematic acquisition. In the unknown condition, the bottles were presented with a random alternation in weight unbeknownst to the participants, so that they did not get information about the object weight until object contact in the Move sub-phase. In the known condition, in contrast, participants were provided with the relevant information about the object weight before movement execution, and trials with a specified weight were presented consecutively. TD’s behavior enabled us to uncover the structural representation of the displacing-action, while the behavior of the language impaired population allowed us to trace potential parallels between motor and linguistic impairment.

The distinction between the two structures depicted in Figure 3 rests on modulations of the effect of physical object weight as a function of prior weight-knowledge. Our analysis therefore focused on interactions between the factors Weight and Knowledge in each of the two sub-phases of the displacing-action. Whenever this interaction was significant, planned comparisons between heavy and light objects were performed. Additional statistics are given in Table S1 in File S1 .

TD children (n=7, 4 males, mean age 10 years and 6 months). Figure 4 in the left panel plots peak latencies for the analyzed kinematic parameters ( Figure S1 ). The critical interaction between Weight x Knowledge was observed for 4 parameters in the Reach- and 3 parameters in the Move sub-phases. Additionally the interaction between Weight x Knowledge was found on the whole action time (the time elapsed from the beginning of the Reach sub-phase to the very end of the Move sub-phase when the hand left the bottle). Planned comparison between heavy and light objects in the Known and Unknown conditions revealed that:

Horizontal line with (*) indicates significant planned comparison between heavy and light objects. Vertical line with (*) indicates significant main effects of Knowledge (all p<= .05).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0072677.g004

in the Unknown condition , when the weight was unknown prior to object contact, its effects were absent from the Reach sub-phase, and present only in the Move sub-phase. In this Move sub-phase, we found that heavy objects gave rise to delayed wrist acceleration peaks (F 1,6 =27.09; p=.002), velocity peaks (F 1,6 =27.64; p=.001), and deceleration peaks (F 1,6 =11.40; p=.01) as compared to light objects ( Figure 4 ). The amplitude of the acceleration peak and of the velocity peak were also smaller when displacing the heavy compared to the light objects, however, the interaction between Weight x Knowledge remained marginally significant (Table S1 in File S1 ). In sum, displacing the heavy object as opposed to the light one had a cost (delayed and decreased peaks) that translated in an overall longer whole action time (F 1,6 =6.68; p=.041).

In contrast, in the Known condition , when the object-weight was known in advance, the kinematic parameters adapted to the weight already in the Reach sub-phase. Reaching for the heavy objects yielded anticipated wrist acceleration peaks and maximum grip aperture (latency of first acceleration peak F 1,6 =12.24; p=.01; latency of second acceleration peak F 1,6 =7.89; p=.03; latency of maximum grip aperture F 1,6 =23.72; p=.003). Even more noticeably, weight effects failed to be evident in the Move sub-phase ( Figure 4 ); the light and heavy objects gave rise to equivalent profiles for the relevant kinematic parameters, even though direct contact with the object occurred only in this second sub-phase. Characteristically, in the Known condition, TD children exhibited a comparable whole action time for the two object weights, as if the cost of displacing a heavier object had been counterbalanced during the Reach sub-phase by an anticipation of its kinematics consequences. Note that the object weight effects in the Move sub-phase of the Unknown condition were the inverse of the object weight effects observed in the Reach sub-phase of the Known condition. That is, heavy objects gave rise to later and smaller peaks in the Move sub-phase of the Unknown condition, while expected heavy objects gave rise to earlier peaks in the Reach sub-phase of the Known condition. These anticipated peaks are readily understandable as a motor strategy to compensate the added cost of moving the heavy object on the whole action time, which was observed in the Unknown condition.

SLI children (n=7, 4 males, mean age 11 years, p = ns with respect to TD children age). None of the measured motor parameters (latencies or amplitudes) showed an interaction between Weight x Knowledge ( Figure 4 right panel; Table S1 in File S1 ).

In the Unknown and Known conditions , object weight effects were strictly confined to the Move sub-phase (that is after direct contact with the bottle had occurred). Moving the heavy object as compared to the lighter one resulted in later and smaller peaks (main effect of Weight on latencies of acceleration F 1,6 =29.93; p=.002, velocity F 1,6 =31.60; p=.001, and deceleration peaks F 1,6 =14.73; p=.009; main effect of Weight on amplitudes of acceleration F 1,6 =14.48; p=.009 and velocity F 1,6 =16.84; p=.006). The cost of object weight in the Move sub-phases was such that it impacted the whole action time in both the Unknown and known conditions (main effect of Weight on whole action time F 1,6 =42.92; p=.001).

Additionally in the Known condition , a symmetric main effect of Knowledge was observed in both the Reach and the Move sub-phases, consisting in shorter latencies (for both light and heavy objects alike) when object weight was known in advance by SLI children (In the Reach sub-phase: Time to second acceleration F 1,6 =10.39; p=.018, velocity F 1,6 =10.88; p=.016 and deceleration peaks F 1,6 =9.81; p=.02; In the Move sub-phase: Time to acceleration F 1,6 =5.88; p=.051, velocity F 1,6 =10.38; p=.016, and deceleration peaks F 1,6 =13.17; p=.011). Finally, the whole action time was overall shorter in the Known condition than in the Unknown condition (Main effect of Knowledge on whole action time F 1,6 =8.37; p=.028). These kinematic effects (i.e shorter latencies and whole action time in the Known condition) crucially testify that SLI children did not simply ignore weight information. In the Known condition, they clearly integrated the weight information of the object, but for them this information affected both subcomponents symmetrically. That is, knowing that the object was heavy/light did not translate into knowing how to shift the weight effects to the Reach component to adapt kinematic parameters appropriately.

Importantly, our results for the Unknown condition also provide evidence that SLI children did not otherwise show any gross motor impairment nor specific problem in dealing with object weight; when the object weight was unknown, SLI performance did not differ from those of TD children. Accordingly, an omnibus non parametric MANOVA performed with Group (TD, SLI) as a between-subject factor and Weight (heavy, light) and Knowledge (known, unknown) as within-subject factors revealed no main effect of Group (F=11.87; p = ns), but a significant three way interaction (F=38.49; p=.018). A non parametric MANOVA performed for each group separately, further confirmed that the within-subject factors Weight and Knowledge interacted in TD children movements (F=45.73; p=.01) but not in SLI children movements (F=11.32; p = ns).

Specificity of the syntactic motor deficit

To ascertain the specificity of SLI motor deficit we examined the performance of a group of Fragile X Syndrome (FXS) patients on the same motor task. FXS is the most common cause of inherited intellectual disabilities and the most common single gene cause of autism (90% of FXS patients present autistic-like behavior [ 28 ]). FXS offer an appropriate control for potential confounding factors coming from reduced cognitive resources or autistic traits as the border between SLI and autistic disorder is blurred [ 29 ]. Most importantly language acquisition in FXS is delayedm with first words appearing at 26,4 months instead of 11 for TD and 23 for SLI [ 30 , 31 ], however, the profile of FXS’ linguistic impairment differs from that of SLI subjects, as it centrally concerns speech rate, articulation, and pragmatic aspects of language. Crucially, the syntactic level of FXS subjects is thought to be delayed rather than deviant [ 30 , 32 , 33 ], and complex structures and distant dependencies have been observed to be spared [ 34 ]. We therefore asked FXS patients and age-matched healthy adults to perform the very same structured motor tasks.

FXS adults (n=7, mean age 25 years). For FXS adults, like for TD children, the critical interaction between Weight x Knowledge was observed for peak latencies of several parameters in the Reach- and Move sub-phases and for the whole action time ( Figure 5 left panel; Table S2 in File S1 ). Planned comparison between heavy and light objects in the Known and Unknown conditions revealed that:

Same conventions as in Figure 4.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0072677.g005

in the Unknown condition when the object weight was unknown prior to contact, effects of weight were absent from the Reach sub-phase and present in the Move sub-phase only (latencies of acceleration F 1,6 =74.75; p<.001, velocity F 1,6 =37.95; p<.001, and deceleration peaks F 1,6 =28.73; p=.001) affecting nevertheless the whole action time (F 1,6 =14.21; p=.009). By contrast, in the Known condition the kinematic parameters adapted to weight in the Reach sub-phase (latency of deceleration peak F 1,6 =7.42; p=.03; latency of maximum grip aperture F 1,6 =17.5; p=.006) enabling the whole action time to be immune to the effects of object weight.

Healthy Adults (n=7, mean age 25,4 years, p = ns with respect to FXS age). . For healthy adults effects of object weight were generally small as further witnessed by the absence of weight effects on whole action time. Yet, like for FXS adults and TD children, the critical interaction between Weight x Knowledge was observed on peak latencies and amplitudes ( Figure 5 right panel; Table S2 in File S1 ). Planned comparison between heavy and light objects in the Known and Unknown conditions revealed that:

in the Unknown condition , the effects of weight were absent from the Reach sub-phase and present in the Move sub-phase (planned comparison between heavy and light objects: acceleration peak latency F 1,6 =8.24; p=.02 and amplitude F 1,6 =18.54; p=.005). In contrast, in the Known condition when the object weight was known in advance, these effects were observed in the Reach sub-phase (planned comparison between heavy and light objects: deceleration peak latency F 1,6 =6.88; p=.039) but no longer in the Move sub-phase.

An Omnibus non parametric MANOVA with [Group (FXS, HA) as a between-subject factor and Weight (heavy, light) and Knowledge (known, unknown) as within-subject factors] revealed 1) a main effect of the factor Group (F=72.06; p=.004), FXS patients showing reduced amplitudes and delayed latencies with respect to healthy individuals ( Figure 5 , Table S2 in File S1 ); 2) an interaction between Group x Weight x Knowledge (F=33.40; p=.03). The non parametric MANOVA performed for each group separately confirmed that the within factors Weight and Knowledge interacted in FXS (F=44.44; p=.015), a similar result was found in healthy individuals though it did not reach significance (F=27.84; p=.078).

In sum, while movement kinematic parameters of SLI and TD children occurred in the same latency range and exhibited comparable amplitudes, SLI children differed from their control group in the ability to modulate kinematic parameters as a function of action structure. FXS patients, in contrast, differed from their control group with respect to their general movement amplitudes and latencies, but did not display deficits in their ability to modulate kinematic parameters as a function of action structure.

Crossing disciplinary boundaries, we explored whether the structure of simple actions could manifest a hierarchical embedding revealed by distant dependencies. We provided experimental evidence that the two sub-phases of a displacing action are asymmetrically structured in ways that owes more to embedding than to mere temporal juxtaposition. By manipulating when participants access object weight information, we devised a way to build a motor distant dependency in order to probe the nature of the structural relation that the two sub-phases of a displacing action entertain. When the weight of a displaced object is unknown, accessibility to weight information is governed by object contact. Consequently, weight can have an impact on kinematics only in the second component of the displace action, i.e. our Move sub-phase, and this, independently of how the two sub-phases are structured (Fig. 3AB). However, when weight information is available prior to object contact, so that participants are able to form a motor representation of the object weight prior to the onset of movement, only an embedded structure predicts that the impact of object weight on kinematics could asymmetrically transfer to the topmost action sub-phase, i.e. our Reach sub-phase, and leave the subordinate sub-phase almost unaffected. This transfer of the weight impact to the kinematic parameters of the Reach sub-phase, attests of a link between the two subcomponents that goes beyond mere juxtaposition.

As predicted, in the unknown weight condition, our results show that for all groups of participants alike, the object weight affected the kinematic parameters of the Move sub-phase, that is only after object contact: thus, the object weight information and the object weight kinematic impact were entirely encapsulated within the Move sub-phase. In contrast, when object weight was known in advance, our kinematic results crucially revealed that for TD children, HA and FXS patients, the kinematic impact of object weight shifted to the Reach sub-phase and was no longer encapsulated in the Move sub-phase. More strikingly and more significantly, this weight effect transfer was further accompanied by an almost complete disappearance of the weight effects from the Move sub-phase, despite the fact this sub-component is where direct contact with the objet and the weight somatosensory feedback takes place. It is thus as if the kinematic impact of the object weight had been entirely relocated from the Move sub-phase to the Reach sub-phase, leaving only a silent motor copy for feedback checking. We argue that only an embedding structure, as illustrated in Figure 3D , accurately models this observed pattern because, although an anticipated weight effect on the first sub-component could also be expected in a juxtaposed structure, this symmetric structure neither predicts nor explains the here observed weight effect disappearance from the second sub-component. Juxtaposed components are understood to be such, because they do not entertain relations beyond that of sequential, temporal or spatial, ordering. Given that the disappearance of kinematic weight effects from the Move sub-phase is a consequence of their anticipated impact on the Reach sub-phase, this weight effect transfer clearly suggests that the two components entertain relations that go beyond mere sequential ordering.

The relation between the point of object weight integration in the movement kinematic of the Reach sub-component and the point of object contact in the Move sub-component (where the weight is felt) presents a strong analogy to a syntactic operation of relative clause displacement in linguistic syntax. When known, the weight of an object is integrated into motor programming and execution prior to direct sensory contact with the object. Likewise, in a relative clause, a nominal phrase is pronounced, i.e. integrated in the speech computation before the position in which it is semantically interpreted. Furthermore, in motor embedding, the early integration of weight effects in the dominating Reach sub-component licenses a ‘silent’ motor copy of object weight in the Move sub-phase, quite analogous to the ‘silent’ copy of a displaced nominal phrase that linguistic theory posits after noun-phrase displacement [ 13 ]. That is, although the object weight is accessed via somatosensation after object contact, it no longer impacts the kinematic parameter at that point because weight effects were integrated earlier at a higher level of the action structure. Finally, recall that characteristically in language, ‘distant dependencies’ have been observed to lead acceptable sentences only across clauses that are embedded (This is the heavy bottle [John realized (which) Mary knows [he grasped]]), but not across clauses that are coordinated or juxtaposed (* ‘This is the heavy bottle (which) John smiled and Mary stretched and he grasped’). This linguistic hierarchical constraint dubbed “The Coordinate Structure Constraint” [ 14 ] seems here to be echoed in the motor system.

To further investigate whether the uncovered motor syntactic mechanisms at play in our displacing action displayed some fundamental aspects typical of linguistic syntax, we tested the movement structure of children with SLI. SLI children suffer from a disorder known to disrupt the development of a full-blown linguistic syntax. In particular, as it has been repeatedly observed, children with SLI commonly fail to produce and understand complex embedding and distant dependencies, particularly in relative clauses [24,25,35,36 but see 37 for an alternative statistical learning deficit hypothesis]. Furthermore, when prompted to do so, they have been observed to produce juxtaposition of matrix clauses instead. The sentence “I did it with my teacher, he’s called Doris” (the English rendering of a sentence produced by a French SLI patient, taken from 25) is a characteristic example of such failed attempts for the embedded relative clause: I did it with my teacher who is called Doris. In SLI, this deficient relative clause rendering has been taken to evidence a failure in the ability to construct appropriately embedded syntactic structures [ 24 , 25 , 35 , 36 ]. Though future studies are needed to establish intra-subjects correlation between motor and linguistic deficits, our findings on the distinctions between TD and SLI in the motor domain highlight an intriguingly striking parallel with the typical linguistic syntactic deficits SLI children have been observed to exhibit. With weight knowledge available prior to movement onset, SLI children were the only group that failed to transfer the motor computation of kinematic object weight adjustment from the Move to the Reach sub-phase. That is, despite prior weight knowledge, kinematic adjustments to weight for SLI children continued to take place only after object contact, i.e. still in the Move sub-phase. Thus, no displacement of weight effects was observed for this group. Yet, weight information was not ignored: As witnessed by the overall shortening of the latencies in the known condition both in the Reach and in the Move sub-phase alike, SLI patients benefited from weight knowledge. However, while for TD children, prior weight knowledge caused the appearance of an asymmetric shift in how weight effects impacted the two sub-components of our structured displacing action, for SLI children in contrast, advanced weight knowledge affected the two subcomponents symmetrically. This is as if the structure of the SLI children displacing sub-phases were juxtaposed, rather than embedded, provoking a distributed effect of advanced weight knowledge as if the expected normal execution of a motor distant dependency was disrupted. This, we suggest, echoes the Coordinate Structure Constraint at play in language syntax.

The rather striking analogy here observed for SLI patients between specific known language difficulties with relative clauses and hitherto unnoticed fine-grained structural motor abnormalities, highlights the possibility of common syntactic mechanisms in language and motor domain with renewed vigor.

Within the framework of the mirror system, an analogous motor impairment has been reported for autistic children by Cattaneo and colleagues ([ 38 ], see also 39 ). The study investigated the ability of autistic children to understand the motor intentions of others. In their study the authors compared the electro-myographic activity of the mouth opening muscle of TD with that of high functioning autistic children. These subjects were observing and executing two action chains; 1) reaching and bringing to the mouth a piece of food, 2) reaching and putting in a container a piece of paper. Characteristically, in the bringing to the mouth action, for both observation and execution, TD children exhibited an anticipatory activity of the mouth-opening muscle that started during the reaching sub-phase until the end of the movement. In contrast, autistic children failed to exhibit a comparable anticipatory muscle activity. Mouth muscle activation was confined to the bringing phase. Although our results also report an analogous failure in SLI children to kinematically anticipate weight effects, the putative resemblance between the two types of motor execution failure may only be superficial. In Cattaneo et al.’s study the task involved the anticipation of the goal of an action and the impact of knowing this goal on motor parameters. In contrast, our task investigated how knowing the weight of an object allows participants to transfer and invert the effects of object weight from the Move to the Reach sub-phase. This transfer is independent of the goal (i.e. the displacement of the object), which in our case remains the same. Hence, Cattaneo and colleagues observed a delay of the onset of the mouth opening muscles activity in autistic population, compared to their controls. In our case, however, the qualitative shift of the way motor parameters adapt to weight knowledge from the “Move-“ to the “Reach-“ phase, which characterizes the performance of our control groups, is never seen in the population of SLI children. Most importantly, FXS patients, who suffer from language deficits observed to spare syntactic embedding and distant dependencies [ 34 ], displayed a preserved ability to adjust their motor parameters as a function of action structure requirements. Despite a profound alteration of their motor performance, as witnessed by the overall delay in their movement parameters and the relative sluggishness of their motor performance, FXS patients produced what we could call a structurally correct motor distant dependency.

To date, only few studies have empirically probed the nature of motor syntax [see, for a review, 7]. Hoen and colleagues showed that agrammatic patients trained with non-linguistic sequences could improve their performance with relative clause comprehension [ 40 ]. In the motor domain, Fazio and coworkers [ 41 ] documented the inability of agrammatic brain-damaged patients to correctly reorder frames taken from a video-clip showing a human action, while their ability to reorder physical events was preserved. Using repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) in a paradigm similar to the one used by Fazio et colleagues, Clerget and colleagues [ 42 ] suggested that Broca’s area played a role in understanding complex transitive actions. In an Electro-Encephalogram study [ 43 ], healthy participants presented with videos containing expectancy violations of common real-world actions (i.e. an electric iron used in an ongoing bread cutting action) displayed two event related potentials (ERP), one negative peaking around 400ms and one positive peaking around 600ms and centered over the parietal lobes. These ERPs recall respectively the N400 elicited by semantic violation and the syntactic positive shift (the P600) argued to index syntactic integration difficulties [ 44 , 45 ] Kaan and Swaab 2003; Osterhout et al. 1994). While all these studies support the existence of syntactic mechanisms at work in complex action understanding, the present study critically adds to our knowledge by indicating that the motor production system could share rather specific structural representations and processes with language as well as, possibly, some of its constraints, namely, perhaps constraints akin to the linguistic Coordinate Structure constraint.

In conclusion, supporting Jackendoff’s theoretical conjecture, we provide experimental evidence for a motor structure that is in many ways analogous to the linguistically characterized distant dependency at hand in relative clauses. Our study is also the first to make use of a task simple enough to be performed by young patients, but whose structure is sufficiently complex to probe fine motor skills. Our task uses a fixed set of material (objects properties and movement goals) and manipulates only one feature of the target action, namely prior knowledge of object weight. Moreover, this task enables a direct access to the structural properties of simple actions without the potential confounds of semantic or cultural factors. Our findings, that a developmental linguistic deficit affecting (among other) the ability to construct complex embeddings and dependencies, is mirrored by a structural deficit in building the motor analogue of a distant dependency strongly restate the principled motivation for investigating common motor and linguistic structural mechanisms, and the existence of a possible motor precursor for language syntax.

Ethics Statement

All participants were naïve as to the purpose of the study and all participants as well as their parents or guardians (for children), gave a written informed consent to participate to the study, which was approved by the local ethics committee (CPP Sud Est II), and were tested in observance of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participants

SLI children were diagnosed by a trained multidisciplinary team of specialists working at the national reference center for learning and communications disorders of the Lyon hospitals. IQ evaluation revealed a difference of at least 20 points between IQv and IQp (mean score 91.6 and 116.5, respectively), which represents more than 1.5 standard deviations. Patients were between 9 years and 13 years and 4 months, mean age was 11 years. All patients, except one, were right handed. Four patients were diagnosed with a dysphasia affecting the phonological and syntactic aspects of their language, and three patients were diagnosed with a dysphasia affecting the lexical and syntactic aspects. All patients have been undergoing intensive speech reeducation for several years (six years and a half on average). At the time of testing, children had at least partially recovered from phonological and lexical deficits, but remained dramatically impaired at the syntactic level, expressing themselves using simple sentences only. Language production rather than comprehension was affected: For 6 out of the 7 patients syntactic comprehension as assessed with the ECOSSE test (Evaluation de la Compréhension Syntaxico-Sémantique, P. Lecocq, 1996) met the expected age-dependent level of performance. On the production side, 4 out of 7 patients exhibited a delay of, on average, 36.3 months with respect to their chronological age (for syntax and morpho-syntax; TGC-R: Test of Grammatical Closure, Deltour, 1992, 2002). In the remaining 3 patients, the developmental age of syntactic abilities was not quantifiable: Despite a chronological age of 9 years and 1 month, 9 and 13 years, no complex sentences were produced, and the present tense was the only one used.

FXS patients were recruited through the Rare Causes of Intellectual Disability National Center of the Lyon hospitals. They were between 20 and 31 years-old. All but one were right-handed. FXS was confirmed by more than 200 CGG repeats or a positive cytogenetic test and a family history of FXS. Mental age varied from 4,5 to 7,5 years as evaluated with nonverbal reasoning test (Raven’s Colored Progressive Matrices). Language comprehension, assessed with the ECOSSE test, revealed a developmental age of 5 years and 5 months. On the production side the mean length of utterance was 5,39 words and the mean age of grammatical development was 4,92 as evaluated with the TGC-R.

Typically developing children and healthy adults (all right-handed) were recruited out of patient’s relatives.

Stimuli and procedure

Two visually identical white opaque bottles (250ml containers) were used as stimuli, one weighting 50g (termed hereafter ‘light’) and one weighting 500g (termed hereafter ‘heavy’). Prior to starting the experiment, participants were asked to manually familiarize themselves with the bottle and the experimenter reinforced their perception by saying “You feel how this bottle is heavy/light, now feel this one; isn’t it much lighter/heavier?”.

Participants were required to keep their hand, held in a pinch grip position, on a fixed starting point on a table along their sagittal axis. Upon hearing a go-signal they were instructed to reach and grasp for the bottle (placed 20cm in front of the starting point) and to displace it to a pre-defined position 15cm to the right of the initial position. Once the bottle was displaced to its final position, participants replaced his/her hand back on the starting point and waited for the next go-signal. Participants were instructed to grasp the bottle on its cap to ensure a uniformly sized grasp surface. Participants performed a total of 40 trials. In the first 20 trials, relevant information about object weight (i.e., light vs. heavy) was provided prior to movement onset and participants perform a block of 10 successive trials with the heavy object, and a block of 10 successive trials with the light object, or vice versa. In the remaining 20 trials, object weight was unknown and heavy and light trials were proposed in a pseudo random order. To ensure that participants were oblivious of object weight, experimenter’s manipulation of the bottles was concealed.

Movement recordings and data processing (analysis)

Movement kinematics were recorded via an Optotrak 3020 system (Northern Digital Inc). One active infrared marker (sampling rate set at 300Hz) was placed on the wrist, two respectively on the index and thumb fingers, and two on the bottles. A second-order Butterworth dual pass filter (cutoff frequency, 10Hz) was used for raw data processing. Individual movements were then visualized and analyzed using Optodisp software (Optodisp copyright UCBL-CNRS, Marc Thevenet et Yves Paulignan, 2001). For each Reach sub-phase latency and amplitude of the first and second acceleration peaks, velocity peaks, deceleration peaks and grip aperture were measured. For the Move sub-phase latency and amplitude of the highest acceleration peaks, velocity peaks, and deceleration peaks were measured ( Figure S1 ). The whole action time, as defined as the time elapsed between the beginning of the movement when participants left the starting point and movement end when participants had displaced the bottle in its final position.

To reduce noise, the first two movements of each of the four experimental conditions were discarded from subsequent analysis. For each participant, mean values for the different kinematic parameter were computed separately for each condition. Data normality and homoscedasticity were controlled with Shapiro-Wilk and Levene tests, respectively. Mean values for each participant were entered into a repeated measures ANOVA with Weight (light, heavy) and Knowledge (known, unknown) as within-subject factors. To further test the combined effect of all measured parameters of the movement a multivariate approach was applied. Since the requirement of a parametric MANOVA, i.e., to have more observations than parameters, is not fulfilled in our case, a resampling-based non parametric MANOVA with Fisher combination of the p-values was used [ 46 , 47 ].

Supporting Information

Wrist velocity and acceleration profile for the Displace action task.

Here are represented the wrist velocity (left panel) and acceleration profile (right panel) pertaining to an individual representative movement and the collected parameters. The Reach sub-phase (green ground) is characteristically composed of two acceleration peaks followed by a velocity peak (red marks) and a deceleration peak (green mark); the ensuing Move Object phase (orange ground) is in turn characterized by an acceleration peak, a velocity peak (red marks) and a deceleration peak (green mark). Please note that more than one deceleration peak may occur for each movement sub-phase (or acceleration for the second sub-phase); in those cases, the lowest deceleration or on the contrary the highest acceleration peak was collected for subsequent analyses.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0072677.s001

Tables S1 & S2.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0072677.s002

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all the participants and their families, L. Finos for his support with statistical analyses and A. Brun for her help during data acquisitions.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: ACR AC TAN YP VdP PF VD. Performed the experiments: ACR AC PF. Analyzed the data: ACR VD. Wrote the manuscript: ACR AC TAN YP VdP PF VD.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- 3. Fadiga L, Craighero L, Roy AC (2006) In: Y. GrodzinskyK. Amunts, Broca’s region. Oxford University press, New York. pp. 137-152.

- 4. Grodzinsky Y, Amunts K, editors (2006) Broca’s region. Oxford University press, New York.

- 10. Knott A (2012) Sensorimotor cognition and natural language syntax. Cambridge: MIT Press. pp. 416.

- 11. Jackendoff R (2007) Language, Consciousness, Culture: Essays on Mental Structure. Cambridge: MIT Press. pp. 416.

- 13. Chomsky N (1977) In: P. CulicoverT. WasowA. Akmajian. Formal Syntax. New York: Academic Press. pp. 71–132.

- 14. Ross JR (1967) Constraints on variables in syntax. Doctoral dissertation MIT.

- 23. Chomsky N (1982) Lectures on Government and Binding: The Pisa Lectures. Dordrecht, Holland: Foris Publications.

- 25. Hamann C, Tuller L, Monjauze HD (2007) (Un)successful Subordination in French-speaking Children andAdolescents with SLI. Proc 31st Ann BUCLD 286-298.

- 26. Rice ML, Hoffman L, Wexler K (2009) Judgments of omitted BE and DO in questions as extended finiteness clinical markers of SLI to fifteen years: A study of growth and asymptote. J Speech Lang Hear Res, 52: 1417-1433 doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0171). PubMed: 19786705.

- 31. Leonard LB (1998) Children with specific language impairment. Cambridge MIT Press.

- 33. Finestack LH, Abbeduto L (2010) Expressive Language Profiles of Verbally Expressive Adolescents and Young Adults With Down Syndrome or Fragile X Syndrome. J Speech Lang Hear Res 53: 1334-1348 doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2010/09-0125). PubMed: 20643789.

- 47. Pesarin F (2001) Multivariate Permutation Tests with Applications in Biostatistics. Wiley, New York.

Syntax, the brain, and linguistic theory: a critical reassessment

Perspective 01 November 2023 Three conceptual clarifications about syntax and the brain Cas W. Coopmans and Emiliano Zaccarella 225 views 0 citations

Hypothesis and Theory 15 September 2023 A reconceptualization of sentence production in post-stroke agrammatic aphasia: the Synergistic Processing Bottleneck model Yasmeen Faroqi-Shah 1,135 views 0 citations

Original Research 14 August 2023 Defying syntactic preservation in Alzheimer's disease: what type of impairment predicts syntactic change in dementia (if it does) and why? Olga Ivanova , 2 more and Juan José G. Meilán 861 views 1 citations

Opinion 09 August 2023 Lexico-semantics obscures lexical syntax William Matchin 1,359 views 2 citations

Original Research 09 June 2023 Dissociating the processing of empty categories in raising and control sentences: a self-paced reading study in Japanese Koki Yamaguchi and Shinri Ohta 1,306 views 0 citations

Review 25 May 2023 The neurofunctional network of syntactic processing: cognitive systematicity and representational specializations of objects, actions, and events Brennan Gonering and David P. Corina 929 views 1 citations

Loading... Perspective 20 April 2023 False perspectives on human language: Why statistics needs linguistics Matteo Greco , 3 more and Andrea Moro 2,583 views 3 citations

Review 10 March 2023 How (not) to look for meaning composition in the brain: A reassessment of current experimental paradigms Lia Călinescu , 1 more and Giosuè Baggio 1,867 views 2 citations

Hypothesis and Theory 21 February 2023 Correlated attributes: Toward a labeling algorithm of complementary categorial features Juan Uriagereka 1,070 views 0 citations

Loading... Hypothesis and Theory 13 February 2023 Moving away from lexicalism in psycho- and neuro-linguistics Alexandra Krauska and Ellen Lau 4,468 views 7 citations

- Centre for Linguistic Research

- All About Linguistics- Home

- About this website

- Branches of Linguistics

Research in Syntax

Find out more about how linguists research Syntax through looking at some example research.

Dixon (1999)

Syntax – the pillar of human language.

What separates us from the animals? Why have humans been able to conquer the planet whereas no other animal hasn’t? The answer is of course language! “ But hold on! ” I hear you say, “ We’re not the only animals with language, whales sing to each other, dogs bark, hyenas laugh, and they all appear to understand one another. ” That is true, but these methods of communication are heavily simplified. An animal call may mean ‘ There is food here‘ or ‘ Danger !’ but what they lack is the ability to put these sounds together to form complicated meanings.

Even if animals were able to do this, we would encounter another problem as to how to interpret these new complicated meanings. What would the sounds for ‘ food here ‘ and ‘ danger ‘ together mean? Dangerous food? Food is here but there is also a leopard in the bushes? This is where syntax comes in.

Syntax essentially categorises words, fills in the gaps and makes a group of words make sense. Every human in the world uses the same syntactic structure to communicate with other humans, the only difference is the sounds that are produced. This isn’t to be confused with the order of where words appear such as Subject-Verb-Object compared to Subject-Object-Verb in Japanese for example, as all languages contain nouns, verbs, prepositions, inflections etc. no matter where they come in the sentence, they are still present. So, there is clearly an underlying system that all humans can understand and acquire.

So where is this steppingstone between one sound calls and a complex sentence? How did humans get here? Bickerton refers to the case of Genie, a girl who had had no communication with anyone due to her father imprisoning her from the age of 18 months until she was found years later at the age of 13. She had missed the critical age of of between 18 months and 3 years where she children usually acquire an adult language (see language acquisition). When she was found she didn’t know how to speak English at all. Even after a long time of treatment from speech therapists and linguistic experts, she only managed to gain a very simple version of English. Her sentence’s consisted of noun and verb or adjective and noun, occasional strung together and even more rarely with adverbs and certain prepositions.

Here’s an example:

G: Genie have yellow material at school. M: What are you using it for? G: Paint. Paint picture. Take home. Ask teacher yellow material. Blue paint. Yellow green paint. Genie have blue material. Teacher said no. Genie use material paint. I want use material at school.

He had expected her to either fully learn human language as someone might learn a 2nd language, or not be able to learn one at all. Bickerton found it strange that the girl had developed a kind of proto, or base language. This form of speaking is actually more common than you might think. If you’ve ever been on holiday to a country whose language you can’t speak, you may have found yourself trying to talk like this to get your point across. Protolanguage is the most basic form of language, where the mere sounds of words begin to form meanings when combined together.

There is still the issue of how language moved from the protolanguage structure to the syntactical structure. The answer lies in explicitly, or being as clear as possible. If a child were to say to you ‘no socks!’ how would you interpret it? That the child isn’t wearing socks? They do not own any socks? They don’t want to wear socks? They don’t want you to wear socks? There are too many ways for the sentence to be interpreted. By adding new phrases to the sentence, the meaning becomes narrowed down. The actual meaning in this instance is ‘I don’t want to wear socks’. If we are to break it down, you can see it is rather difficult to not understand. The noun phrase I refers to the speaker, don’t is a combination of the verb to do and a negative, want to tie to don’t to form the negative of want, wear shows what not/to do with the object, and finally socks the object of the sentence. Everything from don’t to wear tells us something about the socks in relation to the child. A lot better and surprisingly, easier to understand than simply ‘no socks!’!

- Adapted from: Bickerton D., (1990) Language and Species. The University of Chicago Press.

One of the most interesting aspects of the English language is the ability to change the order of words and still end up with the same meaning such as ‘John bought a book’ and ‘A book was bought by John’. You may recognise these as the active and the passive forms of a sentence, the passive sentence being the one where the object is given more emphasis than the subject as opposed to the standard subject-verb-object. But if we can easily shift the object and subject around, how do we recognise which one is which in any given sentence?

The key actually lies with the verb. If we want to say that a hearty chuckle was let out by John at someone called Mary (in far less words of course!) we might say ‘John laughed at Mary’. Here, laughed acts as a bridge between Mary and John indicating that what comes before the verb acts on what comes after the verb. This is called a transitive verb . If we were to swap the subject and verb however, we come up with ‘at Mary laughed John’ we have a sentence which kind of makes sense but doesn’t seem to sit right on the tongue.

Another form of verb is the intransitive verb which does not need an object to function so we can say things like ‘John laughed’. Intransitive verbs are used extensively in the passive tense so we can use an intransitive from of the verb laughed to move around the subject and object, so we end up with ‘Mary was laughed at by John’.

So, there you have it, a very brief look at how subject and object can be defined and the links they have to the different types of verbs.

- Adapted from: R.M.W. Dixon (1989) Subject and Object in Universal Grammar Clarendon Paperbacks

Where to next?

Why not check out how syntax is studied to take a closer look at what other researchers are doing.

Bruening (2013)

We will now talk you through a journal article written by Benjamin Bruening. We understand that this article is rather overwhelming so we will try and summarise it for you! If there are any words that you don’t understand please refer to the glossary at the bottom of the page.

Syntax By Phrases in Passives and Nominals March 2013 Volume 16, Issue 1 Pages 1-41 Benjamin Bruening

“ By Phrases in Passives and Nominals” is a recent article related to syntax. It’s about by-phrases (exactly what they sound like; phrases beginning with by), and how they assign theta roles in sentences.

Theta roles simply describe what a word does in a sentence. There are many different theta roles; for example agent , goal and theme . If a word has been assigned the role of agent , then it is likely to be the subject of the sentence and is performing the action described.

For example, in the sentence:

My mother-in-law received the present

Mother-in-law has the agent role, which has been assigned to it by the verb.

Passive sentences , such as this one, do not always have agent roles:

The present was received

Here, the agent is not specified, but if we want to say who received the present while keeping the sentence in the passive, we can add a by-phrase like this:

The present was received by my mother-in-law

Here the by-phrase is assigning the agent role to mother-in-law.

Theta roles can be a bit overwhelming, and we understand that! So don’t worry! If you want to know more about theta roles, look here .

There is a long-standing claim that by-phrases can assign certain theta roles in passive sentences that they cannot in other types of sentences, such as nominalisations . In a nominalisation, a word that is not usually a noun is used as a noun , for example:

The receipt of the present (*by my mother-in-law)

Here, the verb receive has been nominalised.

Bruening disagrees with the idea that by-phrases in passives behave differently to by-phrases in nominals. So, to start, he uses some examples to show how they do appear to behave differently.

“ The present was received by my mother-in-law ” and “ The receipt of the present (*by my mother-in-law) ” are two of these examples. In the first sentence, which is a passive, the agent role is assigned by the word “by”. But when we try to use the by-phrase in the same way in the second sentence, a nominal, the result is ungrammatical.

Another pair of examples:

Harry is feared by John *The fear of Harry by John

These show the same pattern – the by-phrase is fine in the passive but becomes ungrammatical in the nominal. (A * before a phrase or sentence means that is is ungrammatical.)

However, in Bruening’s judgement “The receipt of the present by my mother-in-law” is perfectly acceptable, so he argues that in some nominals, by-phrases are allowed. Here are some examples he uses to back up his argument:

… after the date of receipt of the letter by the GDS The start date must be at least ten days after the receipt of the form by Gift Processing.

These examples were found using Google searches and show by-phrases in nominals which are grammatical. However, there are still some nominals which don’t allow by-phrases, such as “ *The fear of Harry by John ” from the previous example. So, we need to look at the differences between the nominals which do allow by-phrases and those that don’t, to find out why this is!

Bruening also argues that a rule explaining why only certain nominals allow by-phrases should not be a rule just about by-phrases, because two other types of adjuncts follow the same pattern as by-phrases (so they are not allowed in the same types of nominals that by-phrases are barred from). This means that a single, general rule can cover all three of these adjuncts .

(An adjunct is an optional addition to a sentence and can be omitted without making the sentence ungrammatical. For example, “by John” is an adjunct to the sentence “Harry was feared by John”. Removing it leaves “Harry was feared”, which is a grammatical sentence by itself.)

The other adjuncts which behave in the same way as by-phrases are comitatives and instrumentals .

Comitatives show accompaniment, for example:

The ushers seated 50,000 ticket holders with the security guards

Here, the meaning is that the ushers and the security guards were both seating ticket holders – so “ with the security guards ” is comitative.

Instrumentals show what was used to do something, for example:

The enemy sank the ship with a torpedo

Here, “ with a torpedo ” is instrumental, as the torpedo was used to sink the ship.

So, what is it that makes all three types of adjunct ungrammatical in certain nominals? According to Bruening, these adjuncts need there to be an agent role . Some examples might help you to understand:

The ship was sunk The ship sank

Can you see the difference between these two sentences? Let’s try adding a by-phrase to each of them:

The ship was sunk by a torpedo *The ship sank by a torpedo

The first sentence makes perfect sense, but the second is ungrammatical. This is because the verb in the second sentence doesn’t have an agent role, while the first does. If a by-phrase assigned agent roles by itself, we would expect to be able to add them even to verbs which wouldn’t otherwise have an agent, like “ sank ” from the second example.

Instead, Bruening suggests they fill the agent roles, rather than adding them. “ The ship sank ” doesn’t imply that something caused the ship to sink – it just sank. So, it doesn’t make sense to add a by-phrase to this sentence. In the sentence “ The ship was sunk “, however, we expect that something caused the ship to sink. A by-phrase can therefore be used to show what it was.

This article shows that by-phrases are interesting in their functions- they can be added to passives but adding them to certain nominals makes them ungrammatical. By-phrases are just one specific type of phrase, but Bruening saw something that interested him about their rules and structure and decided to investigate them further. This is part of the ever-growing and evolving research into syntax, phrases, adjuncts and sentence structure that is going on even today- there are always new things to research and discover about syntax!

If you’re interested in the ideas brought up by this article, why not look at some related areas of linguistics – such as semantics !

Getting a bit lost in terminology? Don’t worry! We’ll guide you through it.

- Agent – This theta role is usually given to the subject of a sentence. The agent does the action described by the verb (For example, in the sentence “Mary gave the cake to John”, Mary has the agent role as she is performing the action of giving.)

- Adjunct -A thing added to something else as a supplementary rather than an essential part Comitative – shows accompaniment

- Goal – This theta role is assigned to a word or phrase that shows where or who the action is directed towards (For example, in the sentence “Mary gave the cake to John”, John has the goal role as he is the person Mary’s action of giving is directed towards.)

- Hypothesis – A supposition or proposed explanation made on the basis of limited evidence as a starting point for further investigation.

- Instrumental – Shows what was used to do something

- Intransitive verbs – A verb (or verb construction) that does not take an object

- Morpheme -A meaningful morphological unit of a language that cannot be further divided

- Nominalisations – The use of a verb, an adjective, or an adverb as the head of a noun phrase

- Noun -A word used to identify any of a class of people, places, or things

- Passive sentences – When the grammatical subject of the verb is the recipient (not the source) of the action denoted by the verb

- Preposition -A word governing, and usually preceding, a noun or pronoun and expressing a relation to another word or element in the clause

- Semantic Roles – The underlying relation that a constituent has with the main verb in a clause.

- Subject -A person or thing that is being discussed, described, or dealt with.

- Theme – This theta role is given to the object that undergoes the action that the agent is performing, but does not change its state (For example, in the sentence “Mary gave the cake to John”, ‘cake’ has the theme role as it is the thing that is being given.)

- Unaccusatives – An unaccusative verb is an intransitive verb (one that does not need to take a complement) that does not assign any external theta roles, and in which the subject does not appear to deliberately initiate the action of the verb. Examples include ‘fall’, ‘die’ and ‘melt’.

- Verb -A word used to describe an action, state, or occurrence, and forming the main part of the predicate of a sentence

- Voice – A sentence can either be in the active voice- “Mary baked a cake”, or the passive voice- “A cake was baked” (Notice that in the passive, you can avoid stating who performed the action- the adjunct “by Mary” is an optional add-on to the sentence.)

Sheffield is a research university with a global reputation for excellence. We're a member of the Russell Group: one of the 24 leading UK universities for research and teaching.

Study at Cambridge

About the university, research at cambridge.

- Events and open days

- Fees and finance

- Student blogs and videos

- Why Cambridge

- Qualifications directory

- How to apply

- Fees and funding

- Frequently asked questions

- International students

- Continuing education

- Executive and professional education

- Courses in education

- How the University and Colleges work

- Visiting the University

- Term dates and calendars

- Video and audio

- Find an expert

- Publications

- International Cambridge

- Public engagement

- Giving to Cambridge

- For current students

- For business

- Colleges & departments

- Libraries & facilities

- Museums & collections

- Email & phone search

- Postgraduates

- Postgraduate Study in Linguistics

- MPhils in Theoretical and Applied Linguistics

- MPhil in Theoretical and Applied Linguistics by Advanced Study

Lent Term Seminars

Topics in Syntax

- Faculty of Modern and Medieval Languages and Linguistics

- Faculty Home

- About Theoretical & Applied Linguistics

- Staff in Theoretical & Applied Linguistics overview

- Staff and Research Interests

- Research overview

- Research Projects overview

- Current projects overview

- Expressing the Self: Cultural Diversity and Cognitive Universals overview

- Project Files

- Semantics and Philosophy in Europe 8

- Rethinking Being Gricean: New Challenges for Metapragmatics overview

- Research Clusters overview

- Comparative Syntax Research Area overview

- Research Projects

- Research Students

- Senior Researchers

- Computational Linguistics Research Area overview

- Members of the area

- Experimental Phonetics & Phonology Research Area overview

- EP&P Past Events

- Language Acquisition & Language Processing Research Area overview

- Research Themes

- Mechanisms of Language Change Research Area overview

- Mechanisms of Language Change research themes

- Semantics, Pragmatics & Philosophy Research Area overview

- Group Meetings 2023-2024 overview

- Previous years

- Take part in linguistic research

- Information for Undergraduates

- Prospective Students overview

- Preliminary reading

- Part I overview

- Li1: Sounds and Words

- Li2: Structures and Meanings

- Li3: Language, brains and machines

- Li4: Linguistic variation and change

- Part II overview

- Part IIB overview

- Li5: Linguistic Theory

- Part IIB Dissertation

- Section C overview

- Li6: Phonetics

- Li7: Phonological Theory

- Li8: Morphology

- Li9: Syntax

- Li10: Semantics and Pragmatics

- Li11: Historical Linguistics

- LI12: History of Ideas on Language

- Li13: History of English

- Li14: History of the French Language

- Li15: First and Second Language Acquisition

- Li16: Psychology of Language Processing and Learning

- Li17: Language Typology and Cognition

- Li18: Computational Linguistics

- Undergraduate Timetables

- Marking Criteria

- Postgraduate Study in Linguistics overview

- MPhils in Theoretical and Applied Linguistics overview

- MPhil in Theoretical and Applied Linguistics by Advanced Study overview

- Michaelmas Term Courses

- Lent Term Seminars overview

- Computational and Corpus Linguistics

- Experimental Phonetics and Phonology

- Experimenting with Meaning

- French Linguistics

- Historical Linguistics and History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Psychological Language Processing & Learning

- Semantics, Pragmatics and Philosophy

- Syntactic change

- MPhil in Theoretical and Applied Linguistics by Thesis

- PhD Programmes in Linguistics overview

- PhD in Theoretical and Applied Linguistics

- PhD in Computation, Cognition and Language

- Life as a Linguistics PhD student

- Current PhD Students in TAL

- Recent PhD Graduates in TAL

- News and Events overview

- News and Events

- COPiL overview

- All Volumes overview

- Volume 14 Issue 2

- Volume 14 Issue 1

- All Articles

- TAL Talks Archive

- Editorial Team

- Linguistics Forum overview

- Schedule of Talks

- Societies overview

- Linguistics Society

- Research Facilities

Convenor: Dr James Baker