- Find a Lawyer

- Ask a Lawyer

- Research the Law

- Law Schools

- Laws & Regs

- Newsletters

- Justia Connect

- Pro Membership

- Basic Membership

- Justia Lawyer Directory

- Platinum Placements

- Gold Placements

- Justia Elevate

- Justia Amplify

- PPC Management

- Google Business Profile

- Social Media

- Justia Onward Blog

oral argument

- A spoken presentation where a party outlines their position and the logic supporting it, typically before a court of appeals

- The attorney presented a compelling oral argument, making the judge reconsider the initial decision.

- Every party has the opportunity to make an oral argument before the board makes a decision.

- The effectiveness of the oral argument can often influence the final outcome of the case.

- Bankruptcy Lawyers

- Business Lawyers

- Criminal Lawyers

- Employment Lawyers

- Estate Planning Lawyers

- Family Lawyers

- Personal Injury Lawyers

- Estate Planning

- Personal Injury

- Business Formation

- Business Operations

- Intellectual Property

- International Trade

- Real Estate

- Financial Aid

- Course Outlines

- Law Journals

- US Constitution

- Regulations

- Supreme Court

- Circuit Courts

- District Courts

- Dockets & Filings

- State Constitutions

- State Codes

- State Case Law

- Legal Blogs

- Business Forms

- Product Recalls

- Justia Connect Membership

- Justia Premium Placements

- Justia Elevate (SEO, Websites)

- Justia Amplify (PPC, GBP)

- Testimonials

Mastering the Art of Legal Argumentation: A Guide for Law Students

This comprehensive guide is a must-read for law students looking to improve their legal argumentation skills.

Posted January 2, 2024

Featuring Cian S.

Law School: Crafting a Compelling Personal Statement

Friday, april 19.

8:00 PM UTC · 45 minutes

Table of Contents

Legal argumentation is an essential skill for any law student or practicing lawyer. It involves the art of persuading an audience, whether it’s a judge, a jury, or other legal professionals, to adopt a particular viewpoint or conclusion. In this article, we’ll explore all aspects of legal argumentation, from understanding why it’s important to crafting a strong legal argument and using technology to enhance your skills.

Understanding the Importance of Legal Argumentation in Law School

Law students are often required to write briefs, oral arguments, and appellate court opinions as part of their coursework. These tasks require them to understand the intricacies of legal argumentation. Legal argumentation is essential for law students to develop critical thinking skills and articulate their ideas effectively. They need to analyze legal issues, gather evidence, structure their arguments, and persuade their audience to adopt their positions. Without legal argumentation skills, law students will struggle to excel in their coursework or their legal careers.

Moreover, legal argumentation is not only important for academic success but also for practical application in the legal profession. Lawyers must be able to present their arguments persuasively in court, negotiate effectively with opposing counsel, and draft legal documents that are clear and concise. Legal argumentation skills are also crucial for developing creative solutions to complex legal problems and for advocating for clients' rights and interests. Therefore, law students must prioritize the development of legal argumentation skills throughout their education to succeed in their future legal careers.

Legal argumentation skills are essential not only for law school but also for professional practice. In legal practice, lawyers use their argumentation skills to convince judges, juries, or clients of their position. Students should look for opportunities to apply their legal argumentation skills by taking internships, externships, or participating in legal clinics.

Mastering the art of legal argumentation can help build confidence in law students. By developing their legal argumentation skills, students can face legal challenges with confidence and clarity. They can make more convincing oral arguments, write better briefs, and produce persuasive evidence. This confidence can translate directly into better performance in law school or legal practice.

The Fundamentals of Crafting a Strong Legal Argument

Crafting a strong legal argument requires a thorough understanding of the law, factual analysis, and persuasive writing. Students need to research and identify legal issues, gather relevant facts, and then apply the law to the facts. They should also structure their arguments with clarity and coherence to prevent confusion or ambiguity. Additionally, they need to use persuasive language and evidence to convince their audience to adopt their positions.

Another important aspect of crafting a strong legal argument is anticipating and addressing counterarguments. Students should consider the opposing viewpoints and potential weaknesses in their own arguments. By addressing these counterarguments, they can strengthen their own position and demonstrate a deeper understanding of the issue at hand.

Furthermore, it is essential for students to understand the context in which their argument will be presented. They should consider the audience, the purpose of the argument, and the potential impact of their position. By tailoring their argument to the specific context, students can increase the effectiveness of their argument and achieve their desired outcome.

Analyzing Legal Issues and Gathering Evidence for Your Argument

The analysis of legal issues and gathering evidence from relevant sources is an essential step in legal argumentation. The legal issues provide the foundation for the argument, and the evidence supports the position taken. Law students need to process the legal issues and identify the relevant facts that support their position. They should understand how the court applies the legal principles to the facts and the relevance of previous cases. For example, when applying a precedent or case law, the facts of that case must be similar enough to the case being argued.

Moreover, it is important for law students to consider the counterarguments and potential weaknesses in their argument. This requires a thorough understanding of the opposing side's position and the ability to anticipate their arguments. By doing so, law students can strengthen their own argument and address any potential weaknesses. Additionally, gathering evidence from multiple sources, such as legal journals, case law, and expert opinions, can provide a more comprehensive and persuasive argument. Overall, the analysis of legal issues and gathering of evidence requires careful consideration and attention to detail in order to construct a strong and convincing legal argument.

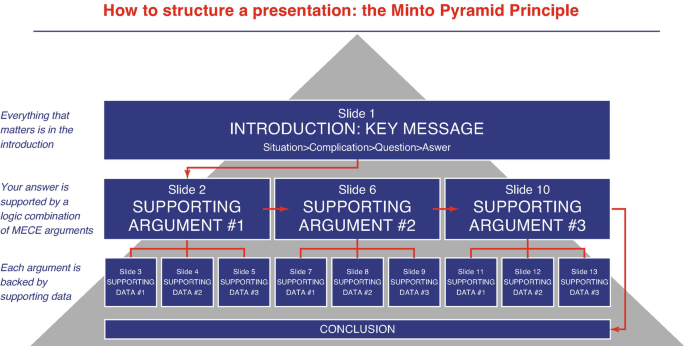

How to Structure Your Legal Argument: Tips and Techniques

The logical structure of a legal argument is crucial for presenting a clear and compelling case to a judge or jury. Law students should be familiar with the various structures of legal arguments, including deductive, inductive, and syllogistic reasoning. In addition, students must learn how to organize the evidence in a way that supports their conclusion. Effective structuring helps to prevent confusion and avoids illogical gaps or inconsistencies in the argument.

Another important aspect of structuring a legal argument is understanding the audience. Lawyers must tailor their arguments to the specific judge or jury they are presenting to. This means considering the judge or jury's background, beliefs, and values. By understanding the audience, lawyers can present their arguments in a way that resonates with them and increases the likelihood of a favorable outcome.

Finally, it is important to remember that a legal argument is not just about presenting facts and evidence. It is also about telling a story. Lawyers must craft a narrative that connects with the audience and makes them care about the case. This means using persuasive language, creating a compelling plot, and highlighting the emotional stakes of the case. By telling a story, lawyers can make their arguments more memorable and impactful.

The Role of Persuasion in Legal Argumentation

Persuasion is an essential tool for legal argumentation. It is the process of convincing your audience that your position is the correct one. In legal writing, students should aim to use persuasive language, vivid imagery, and rhetorical devices to engage their audience and create a powerful emotional impact. However, law students should be careful not to be overly emotional or manipulative, as this can undermine their credibility.

One effective way to use persuasion in legal argumentation is to anticipate and address counterarguments. By acknowledging and refuting potential objections to your position, you can strengthen your argument and demonstrate your thorough understanding of the issue at hand. Additionally, using real-world examples and analogies can help make complex legal concepts more accessible and relatable to your audience.

It is important to note that persuasion is not the same as manipulation. While persuasion aims to convince an audience through logical and emotional appeals, manipulation involves using deceitful or unethical tactics to achieve a desired outcome. As legal professionals, it is crucial to maintain ethical standards and avoid any actions that could compromise our integrity or the integrity of the legal system.

Developing a Unique Voice in Your Legal Writing

While there is a certain formality to legal writing, law students should not sacrifice their individuality. The best legal arguments are ones that convey the writer's unique perspective on the law and the facts. To do this, students must be aware of their tone, word choice, and syntax, and learn to write with purpose and clarity. By developing their unique voice, students can stand out from the crowd and make intelligent and engaging arguments.

One way to develop a unique voice in legal writing is to read widely and study the writing styles of different legal professionals. This can help students to identify their own strengths and weaknesses, and to develop their own writing style. Additionally, seeking feedback from professors and peers can be helpful in refining one's writing and developing a unique voice.

It is important to note that developing a unique voice does not mean sacrificing clarity or professionalism. Rather, it means finding a way to convey legal arguments in a way that is engaging and memorable. By doing so, students can not only stand out in their writing, but also make a lasting impression on their readers.

Preparing for Oral Arguments: Tips and Strategies

Oral arguments can be intimidating for law students, but they are an essential part of legal argumentation. Preparing for oral arguments involves practicing and memorizing key points, anticipating questions from the opposition, and developing a strategy for presenting the argument persuasively. Students should also use effective techniques like using visual aids, body language, and maintaining eye contact to convey their message effectively.

Rebuttals are an essential part of legal argumentation, especially in oral arguments. Winning an argument often entails the ability to address counterarguments and refute them successfully. Law students need to use effective techniques to identify and respond to potential counterarguments while developing strong responses to undermine the opposition's position.

Common Mistakes to Avoid in Legal Argumentation

Legal argumentation is a complex skill, and as such, there are many common mistakes that law students make. These include using fallacious arguments, failing to address counterarguments, lacking a clear thesis statement, and neglecting adequate evidence. By understanding and avoiding these pitfalls, law students can produce better arguments that are persuasive and effective.

Legal argumentation also raises ethical issues, especially when it involves persuading people to accept your position. Law students must be aware of the ethical rules and norms that apply to legal arguments. They must also be careful to avoid misrepresenting facts or engaging in dishonest behavior, which can lead to significant sanctions or worse.

The Importance of Feedback and Continuous Improvement in Legal Argumentation

Feedback and continuous improvement are critical to mastering legal argumentation skills. Law students should seek feedback from their professors, mentors, and peers on their legal writing and arguments. By taking their feedback and continuously improving their work, students can strengthen their skills and produce more persuasive and effective arguments.

Technology provides many opportunities for law students to improve their legal argumentation skills. Students can use online resources such as legal aid websites, legal research tools, and databases to enrich their legal writing. They can also use tools such as speech recognition software, mind-mapping software, and collaborative writing platforms to make the argumentation process more comfortable and productive.

Key Takeaways

- Legal argumentation is an essential skill for law students to master.

- Students must understand its importance, the fundamentals of crafting a strong legal argument, and how to use technology and other resources to enhance their skills.

- They should develop a unique voice, check for mistakes, and prepare for oral arguments.

- Students should be aware of the ethical issues and use feedback to improve their skills continually.

- By mastering legal argumentation skills, students can build confidence and succeed in law school and their legal careers.

Want to continue learning real-world skills that are prevalent to the law field? Check out these articles and see your skill set expand today:

- Books to Read Before Law School: Preparing for Legal Education

- Demystifying the Socratic Method in Law School

- Top 10 Ways to Prepare for Law School

- Transitioning From Law School to a Legal Career: What to Expect

Browse hundreds of expert coaches

Leland coaches have helped thousands of people achieve their goals. A dedicated mentor can make all the difference.

Browse Related Articles

June 6, 2023

Stanford Law School Acceptance Rate: Insights Into Admission Statistics

While Stanford Law School is certainly no stranger to aspiring law students, its admissions statistics are a bit more enigmatic. Discover the secrets behind Stanford Law School's highly competitive admission process and gain valuable insights into their acceptance standards.

May 12, 2023

The Road to Success in Torts: A Comprehensive Guide

Looking to excel in Torts? Look no further! Our comprehensive guide provides you with all the tools and knowledge you need to succeed.

NYU School of Law: A Comprehensive Overview and Guide

Looking to pursue a career in law? Our comprehensive guide to NYU School of Law provides an in-depth overview of the program, curriculum, and admissions process.

A Guide to the Yale Law School Interview Process

If you're applying to Yale Law School, you'll want to be prepared for the interview process.

A Guide to the University of Virginia School of Law Interview Process

Are you preparing for an interview at the University of Virginia School of Law? Our comprehensive guide covers everything you need to know about the interview process, including common questions, tips for success, and insider advice from current students.

A Guide to the University of California--Berkeley School of Law Interview Process

Get insider tips on how to ace your University of California--Berkeley School of Law interview with our comprehensive guide.

A Guide to the Georgetown University Law Center Interview Process

Get insider tips and insights on the Georgetown University Law Center interview process with our comprehensive guide.

A Guide to the University of Southern California Gould School of Law Interview Process

Are you preparing for an interview at USC Gould School of Law? Look no further than our comprehensive guide to the interview process.

A Guide to the Emory University School of Law Interview Process

If you're preparing for an interview at Emory University School of Law, this guide is a must-read.

A Guide to the Fordham University School of Law Interview Process

Get ready for your Fordham University School of Law interview with this comprehensive guide.

A Guide to the University of Wisconsin Law School Interview Process

Get insider tips and expert advice on how to ace the University of Wisconsin Law School interview process with our comprehensive guide.

A Guide to the University of North Carolina--Chapel Hill School of Law Interview Process

Are you preparing for an interview at the University of North Carolina--Chapel Hill School of Law? Look no further than this comprehensive guide to the interview process.

Mastering the Art of Legal Presentations: Essential Tips and Tricks

Navigating through law school and legal careers, budding attorneys realize that mastering the art of presentation is as crucial as knowing the letter of the law. Whether it's arguing a mock trial, presenting a case in court, or persuading peers during a seminar, effective presentation skills can set you apart in the competitive field of law. This Q&A post delves into some of the most commonly asked questions about law presentations and offers presentation hacks aimed at making you a more compelling legal communicator.

Do Presentation Skills Really Matter for Lawyers?

Absolutely! In the legal profession, presenting ideas and arguments clearly and persuasively is critical to success. The American Bar Association emphasizes the importance of honing presentation skills from law school onwards; being persuasive and articulate is a part of your toolkit as an attorney.

What Are Some Effective Presentation Hacks for Legal Professionals?

Start With a Clear Message : Know the core message of your presentation and keep it concise. A clear thesis helps you stay on track and makes your argument more digestible for your audience.

Understand Your Audience : Gauge the level of understanding your audience has about the topic. Presenting to peers might require a different approach than speaking to a jury or a judge.

Use Storytelling : A legal case is essentially a story with a problem and a resolution. Tapping into the power of storytelling can make your presentation more engaging and memorable.

Practice, Practice, Practice : Rehearse your presentation multiple times. This helps reduce nervousness and ensures you're comfortable with the material.

Seek Feedback : Before your presentation, practice in front of colleagues or mentors and ask for constructive criticism to sharpen your delivery.

How Can I Overcome Public Speaking Anxiety Before a Legal Presentation?

Facing a courtroom or an auditorium can be intimidating, but there are strategies to combat this anxiety. Preparing thoroughly is a start; being familiar with every aspect of your presentation can alleviate fear. Additionally, techniques like deep breathing, visualization, and positive self-talk can be beneficial. Moreover, watching inspiring TED Talks on public speaking can provide valuable insights into overcoming fears and delivering impactful messages.

For those looking for a comprehensive solution to enhance their presentation skills, we suggest exploring various features of presentation-focused tools and platforms. While not a substitute for personal practice, these tools can offer unique insights and aid in your delivery. For instance, the features section on College Tools may provide some interesting avenues to explore.

What Role Does Body Language Play in Legal Presentations?

Your physical presence can be as compelling as the words you speak. A poised stance, eye contact, and intentional gestures can convey confidence and help underscore your points. Posture and movement can non-verbally communicate passion for your subject matter and connect with your audience on a more profound level.

Can Technology Help in Improving my Presentations?

Definitely! Technology and AI-powered tools can assist in fine-tuning your presentations. They can help in organizing content, providing cues, and even analyzing your pace and tone. Embracing technology can also make your presentations more dynamic, engaging audiences with multimedia elements that might not be possible with traditional methods.

How Important Is the Quality of Visual Aids in Legal Presentations?

Visual aids should not distract from the message but rather support it. High-quality, pertinent visuals can reinforce your argument or help to clarify complex concepts. Carefully consider your choice of visuals, whether they're diagrams, timelines, or other graphical elements; they should be professionally rendered and easy to understand.

Becoming an effective legal presenter takes time, practice, and a willingness to learn from each experience. Employing the right presentation hacks , understanding the significance of effective communication , and continuing to build upon public speaking skills will prove invaluable throughout your legal career. Strive for clarity, conciseness, and connection with your audience, and you'll be better equipped to make your case, inside and outside the courtroom.

Conclusion: Strong presentation skills are a foundational element of a successful legal career. This Q&A has addressed critical aspects of delivering compelling legal presentations, offering insights and hacks to help you polish your communication prowess. Remember, the journey to becoming an articulate legal professional is ongoing; continue learning, practicing, and adapting to become the best presenter you can be.

Struggling with college quizzes and assigments?

Our AI-powered Chrome extension, College Tools, offers accurate solutions for any multiple-choice quiz in a flash. Integrated directly with your LMS, we provide a seamless, discreet and highly effective solution for your academic needs.

- Reduce study time, boost your grades

- Prooven accuracy

- Universal compatibility

- Discreet chrome extension

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

oral argument

Legal Definition of oral argument

Dictionary entries near oral argument, cite this entry.

“Oral argument.” Merriam-Webster.com Legal Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/legal/oral%20argument. Accessed 9 Apr. 2024.

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

The tangled history of 'it's' and 'its', more commonly misspelled words, why does english have so many silent letters, your vs. you're: how to use them correctly, every letter is silent, sometimes: a-z list of examples, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - apr. 5, 12 bird names that sound like compliments, 10 scrabble words without any vowels, 12 more bird names that sound like insults (and sometimes are), 8 uncommon words related to love, games & quizzes.

Your browser does not support HTML5 or CSS3

To best view this site, you need to update your browser to the latest version, or download a HTML5 friendly browser. Download: Firefox // Download: Chrome

Pages may display incorrectly.

Legal Presentation Skills Guide

Presentation skills are core life skills, but they are doubly important if you wish to practise as a lawyer. You will use presentation skills in a variety of different ways, including:

- to persuade

- to get a message across

Within a professional context:

- in an interview

- in a lecture room

- in a meeting or conference

About this resource

This resource will help you develop effective presentation skills in a legal context.

Work through the material and exercises and you should be able to:

- develop appropriate learning strategies to enhance your presentation skills

- learn and apply the three key rules of presenting

- use presentation skills effectively in advocacy and questioning

Module Contents

Learning presentation skills.

- Not just words

- Preparation, preparation, preparation

The rule of three

Presentation skills in a legal context, questioning, top 10 tips.

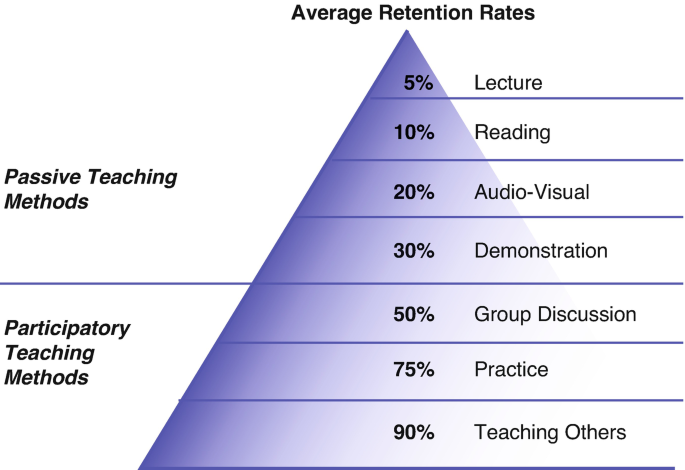

Unfortunately sitting there listening to a lecturer all day will not render you competent at presentation. Like most other skills, presentation skills are acquired through practice, and practice is most productive if accompanied by good preparation and followed by honest evaluation and feedback.

Try it yourself! Get together with one or more other students and try this:

- Without letting anyone else see, one of you sketches a picture of a scene, for example, a road traffic accident or a crime taking place. (Time allotted: 5 minutes).

- Now, the sketcher helps someone else to recreate the same scene, including as much detail as possible without showing them the original sketch. This requires good descriptive and presenting skills. (Time allotted: 10 minutes).

- Compare the finished sketches.

- Repeat the exercise with someone else sketching a different picture. This time, you may share the original sketch while the second person tries to recreate it.

- Discuss how the results differ. What have you learnt about effective presentation?

There are three essential rules about presentation:

- Words are not the only tool

Words are not the only (or even the best) tool

Research shows that when presented with information, we take in 55% of it from visuals, 38% from spoken words and 7% from printed words. So, just like the old adage, “a picture paints a thousand words”, try to use visual aids whenever possible. This is why lawyers use exhibits in documents and in court to help them prove points.

Been to a play where the actors had forgotten their lines? What was your immediate impression? That's why preparation is so important.

Some of the most memorable speeches in history have been the best prepared ones. Winston Churchill spent six weeks preparing, refining and rehearsing his maiden speech to the House of Commons in 1901, and then wowed his fellow MPs with a prefect memorised delivery on the day.

Good preparation involves:

- knowing the contents of your presentation

- having a well laid out plan

- refining and rehearsing the presentation before the real event.

People cannot remember too much information at any one time. Most of your audience will only remember three key things from your presentation, so plan for what these will be.

- Julius Caesar's “Friends, Romans, Countrymen, lend me your ears…”

- “Location, location, location” when buying property

- Churchill's “I can promise you blood, sweat, toil and tears” (usually quoted as the “Blood, Sweat & Tears” speech).

Top tip: Remember, the rule of three when it comes to presentations is:

- The rule of three.

Try it yourself! Think of a presentation you will need to make in the near future. Prepare for that presentation using the rule of three.

Essentially an advocate's task is one of presenting, as they need to:

- be heard (engage and maintain the audience's interest)

- get the message across (select the right contents and emphasis)

- persuade the audience to accept the view advocated.

Aristotle identified three elements of persuasion:

- Ethos: the speaker has to convince the audience that he or she is credible, trustworthy, genuine and believable.

- Pathos: the speech must appeal to the emotions, so that the audience is psychologically inclined to accept the arguments.

- Logos: the arguments must be reasoned, and supported by law and fact.

Advocates must consider these key points when presenting:

Addressing the audience

Body language.

Whether your audience is a judge, a jury, a group of lay magistrates or the Lords of Appeal, you always need to be clear and convincing. Consider who your audience is and tailor your presentation to make sure they will follow all your nuances and inferences.

Make sure you have prepared well, and have a structured and organised argument. Use notes and mind maps as prompts if you need them but remember that you will lose voice projection and eye contact if you are read from a speech. Presenting is not a test of fluency of reading. You should conduct yourself as an advocate, not a newsreader.

Everybody presents in a slightly different way and should find a personal style you are comfortable with. Try to be honest, sincere and authoritative (though you do not always need to be right). Try not to be pompous or arrogant. Ultimately, be yourself, an accomplished advocate, rather than an automaton.

Cultivate the art of fine speaking and the power of persuasion. Make sure you use appropriate and simple language (complex language can obscure the message) and keep your role and audience in mind. Where appropriate, use active language rather than passive phrases and make use of questions, emotion and repetition. Consider the pace of your presentation and include pauses for effect if required.

Be sure to consider your appearance, posture and performance when you are presenting. Different stances can communicate confidence or make you look like a bag of nerves. Think about how you interact with other people in the presentation, and the signals your appearance and behaviour may be sending.

Try it yourself! In no more than five minutes, try and persuade a friend to do something which they have never done before. How easy did you find that? What tactics worked well?

Questioning is the process by which the advocate elicits evidence from witnesses. It is used in two main situations:

- examination-in-chief: from own witnesses

- cross-examination: witnesses from the opposing party

- Keep your questions simple, even if the witnesses are familiar with the facts. This is especially relevant if there is a jury. Try to avoid the use of open questions unless you are questioning your own witness or an expert witness and you know they are reliable. You should be careful to avoid prejudicial effects or digression.

- Leading questions are forbidden in examination-in-chief, unless the advocates agree that the points are not contentious e.g. a name. This is to avoid bias, the suppression of other evidence or the chance of hearing something not delivered in the witness' own words. In cross-examination, however, nearly all questions are leading questions.

- Avoid using a rigid list of questions, though you should have a structured plan, and make sure you listen to the answers while you consider your next question.

- The most important rule is not to ask a question of which you do not know the answer!

Examination-in-chief

Examination-in-chief questions are now commonly written. If you pose them in court, make sure they are not too lengthy. You should structure your witnesses and their testimonies clearly. A chronological approach is the norm, though you can sometimes structure by topic.

Top tip: Examination-in-chief questions are the ‘W’ questions, where, what, who, when, why?

Remember that your witness will be cross-examined by the opposing counsel when you have finished your examination-in-chief and the judge may also question them.

Cross examination

Cross examination aims to test the vigour of opposing witnesses and obtain fresh evidence that is favourable to you. You should take an organised approach, without being too rigid and consider whether to structure your questions by topic or the chronological events.

Cross examination gives you an opportunity to attack the credibility of witnesses, both in general and related to specific issues. You should consider whether you wish to confront the witness at the start of your questioning, or lead them through a train of questions. However, if you discredit the witness in general you should be careful not to destroy your case.

Try to keep your questioning brief and finish on a conclusive point.

Top 10 tips for presentation success:

- Make sure you have prepared well , and have developed a clear, structured and organised argument.

- Consider who your audience is and tailor your presentation to their needs.

- Focus on three key messages that you want your audience to understand and remember.

- Don't try to be somebody else. Find a personal presenting style you are comfortable with.

- If you must use notes, do not read your presentation directly from them.

- Use images, charts, physical signals and pauses to help get your message across. Not just words.

- In examination-in-chief , focus on the ‘W’ questions, where, what, who, when, why?

- When cross-examining , develop a structured plan but avoid using a rigid list of questions.

- Make sure you listen to the answers while you consider your next question.

- Don't ask a question unless you know the answer.

Adding power to courtroom presentations http://www.trialtheater.com/wordpress/2008/courtroom-presentation-skills

Advocacy video http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0nhyFQ6S0VM

Draw a logic tree http://www.strategiccomm.com/logictree.html

Giving effective class presentations video http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1gXE19sh1r8

Killer presentation skills video http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=whTwjG4ZIJg

Oral presentation learning module http://www.jcu.edu.au/office/tld/learningskills/oral/

Positive and negative body language http://www.it-sudparis.eu/lsh/ressources/ops8.php

Public Speaking learning modules http://wps.ablongman.com/ab_public_speaking_2/

Speech Tips http://www.speechtips.com/

The Law Explored: The art of cross-examination http://business.timesonline.co.uk/tol/business/law/columnists/gary_slapper/article1960702.ece

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to prepare and...

How to prepare and deliver an effective oral presentation

- Related content

- Peer review

- Lucia Hartigan , registrar 1 ,

- Fionnuala Mone , fellow in maternal fetal medicine 1 ,

- Mary Higgins , consultant obstetrician 2

- 1 National Maternity Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

- 2 National Maternity Hospital, Dublin; Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Medicine and Medical Sciences, University College Dublin

- luciahartigan{at}hotmail.com

The success of an oral presentation lies in the speaker’s ability to transmit information to the audience. Lucia Hartigan and colleagues describe what they have learnt about delivering an effective scientific oral presentation from their own experiences, and their mistakes

The objective of an oral presentation is to portray large amounts of often complex information in a clear, bite sized fashion. Although some of the success lies in the content, the rest lies in the speaker’s skills in transmitting the information to the audience. 1

Preparation

It is important to be as well prepared as possible. Look at the venue in person, and find out the time allowed for your presentation and for questions, and the size of the audience and their backgrounds, which will allow the presentation to be pitched at the appropriate level.

See what the ambience and temperature are like and check that the format of your presentation is compatible with the available computer. This is particularly important when embedding videos. Before you begin, look at the video on stand-by and make sure the lights are dimmed and the speakers are functioning.

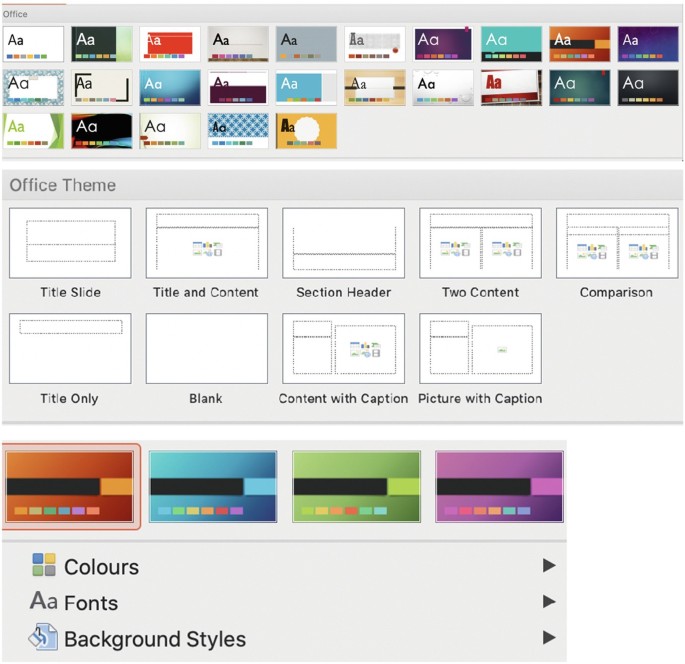

For visual aids, Microsoft PowerPoint or Apple Mac Keynote programmes are usual, although Prezi is increasing in popularity. Save the presentation on a USB stick, with email or cloud storage backup to avoid last minute disasters.

When preparing the presentation, start with an opening slide containing the title of the study, your name, and the date. Begin by addressing and thanking the audience and the organisation that has invited you to speak. Typically, the format includes background, study aims, methodology, results, strengths and weaknesses of the study, and conclusions.

If the study takes a lecturing format, consider including “any questions?” on a slide before you conclude, which will allow the audience to remember the take home messages. Ideally, the audience should remember three of the main points from the presentation. 2

Have a maximum of four short points per slide. If you can display something as a diagram, video, or a graph, use this instead of text and talk around it.

Animation is available in both Microsoft PowerPoint and the Apple Mac Keynote programme, and its use in presentations has been demonstrated to assist in the retention and recall of facts. 3 Do not overuse it, though, as it could make you appear unprofessional. If you show a video or diagram don’t just sit back—use a laser pointer to explain what is happening.

Rehearse your presentation in front of at least one person. Request feedback and amend accordingly. If possible, practise in the venue itself so things will not be unfamiliar on the day. If you appear comfortable, the audience will feel comfortable. Ask colleagues and seniors what questions they would ask and prepare responses to these questions.

It is important to dress appropriately, stand up straight, and project your voice towards the back of the room. Practise using a microphone, or any other presentation aids, in advance. If you don’t have your own presenting style, think of the style of inspirational scientific speakers you have seen and imitate it.

Try to present slides at the rate of around one slide a minute. If you talk too much, you will lose your audience’s attention. The slides or videos should be an adjunct to your presentation, so do not hide behind them, and be proud of the work you are presenting. You should avoid reading the wording on the slides, but instead talk around the content on them.

Maintain eye contact with the audience and remember to smile and pause after each comment, giving your nerves time to settle. Speak slowly and concisely, highlighting key points.

Do not assume that the audience is completely familiar with the topic you are passionate about, but don’t patronise them either. Use every presentation as an opportunity to teach, even your seniors. The information you are presenting may be new to them, but it is always important to know your audience’s background. You can then ensure you do not patronise world experts.

To maintain the audience’s attention, vary the tone and inflection of your voice. If appropriate, use humour, though you should run any comments or jokes past others beforehand and make sure they are culturally appropriate. Check every now and again that the audience is following and offer them the opportunity to ask questions.

Finishing up is the most important part, as this is when you send your take home message with the audience. Slow down, even though time is important at this stage. Conclude with the three key points from the study and leave the slide up for a further few seconds. Do not ramble on. Give the audience a chance to digest the presentation. Conclude by acknowledging those who assisted you in the study, and thank the audience and organisation. If you are presenting in North America, it is usual practice to conclude with an image of the team. If you wish to show references, insert a text box on the appropriate slide with the primary author, year, and paper, although this is not always required.

Answering questions can often feel like the most daunting part, but don’t look upon this as negative. Assume that the audience has listened and is interested in your research. Listen carefully, and if you are unsure about what someone is saying, ask for the question to be rephrased. Thank the audience member for asking the question and keep responses brief and concise. If you are unsure of the answer you can say that the questioner has raised an interesting point that you will have to investigate further. Have someone in the audience who will write down the questions for you, and remember that this is effectively free peer review.

Be proud of your achievements and try to do justice to the work that you and the rest of your group have done. You deserve to be up on that stage, so show off what you have achieved.

Competing interests: We have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: None.

- ↵ Rovira A, Auger C, Naidich TP. How to prepare an oral presentation and a conference. Radiologica 2013 ; 55 (suppl 1): 2 -7S. OpenUrl

- ↵ Bourne PE. Ten simple rules for making good oral presentations. PLos Comput Biol 2007 ; 3 : e77 . OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ Naqvi SH, Mobasher F, Afzal MA, Umair M, Kohli AN, Bukhari MH. Effectiveness of teaching methods in a medical institute: perceptions of medical students to teaching aids. J Pak Med Assoc 2013 ; 63 : 859 -64. OpenUrl

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 3: Oral Presentations

Patricia Williamson

Many academic courses require students to present information to their peers and teachers in a classroom setting. Such presentations are usually in the form of a short talk, often, but not always, accompanied by visual aids such as a PowerPoint. Yet, students often become nervous at the idea of speaking in front of a group. This chapter aims to help calms those nerves.

This chapter is divided under five headings to establish a quick reference guide for oral presentations.

- A beginner, who may have little or no experience, should read each section in full.

- For the intermediate learner, who has some experience with oral presentations, review the sections you feel you need work on.

- If you are an experienced presenter then you may wish to jog your memory about the basics or gain some fresh insights about technique.

The Purpose of an Oral Presentation

Generally, oral presentation is public speaking, either individually or as a group, the aim of which is to provide information, to entertain, to persuade the audience, or to educate. In an academic setting, oral presentations are often assessable tasks with a marking criteria. Therefore, students are being evaluated on two separate-but-related competencies within a set timeframe: the ability to speak and the quality of the spoken content. An oral presentation differs from a speech in that it usually has visual aids and may involve audience interaction; ideas are both shown and explained . A speech, on the other hand, is a formal verbal discourse addressing an audience, without visual aids and audience participation.

Tips for Types of Oral Presentations

Individual presentation.

- Know your content. The number one way to have a smooth presentation is to know what you want to say and how you want to say it. Write it down and rehearse it until you feel relaxed and confident and do not have to rely heavily on notes while speaking.

- Eliminate ‘umms’ and ‘ahhs’ from your oral presentation vocabulary. Speak slowly and clearly and pause when you need to. It is not a contest to see who can race through their presentation the fastest or fit the most content within the time limit. The average person speaks at a rate of 125 words per minute. Therefore, if you are required to speak for 10 minutes, you will need to write and practice 1250 words for speaking. Ensure you time yourself and get it right.

- Ensure you meet the requirements of the marking criteria, including non-verbal communication skills. Make good eye contact with the audience; watch your posture; don’t fidget.

- Know the language requirements. Check if you are permitted to use a more casual, conversational tone and first-person pronouns, or do you need to keep a more formal, academic tone?

- Breathe. You are in control. You’ve got this!

Group Presentation

- All of the above applies; however, you are working as part of a group. So how should you approach group work?

- Firstly, if you are not assigned to a group by your lecturer/tutor, choose people based on their availability and accessibility. If you cannot meet face-to-face you may schedule online meetings.

- Get to know each other. It’s easier to work with friends than strangers.

- Consider everyone’s strengths and weaknesses. Determining strengths and weaknesses will involve a discussion that will often lead to task or role allocations within the group; however, everyone should be carrying an equal level of the workload.

- Some group members may be more focused on getting the script written, with a different section for each team member to say. Others may be more experienced with the presentation software and skilled in editing and refining PowerPoint slides so they are appropriate for the presentation. Use one visual aid (one set of PowerPoint slides) for the whole group; you may consider using a shared cloud drive so that there is no need to integrate slides later on.

- Be patient and tolerant with each other’s learning style and personality. Do not judge people in your group based on their personal appearance, sexual orientation, gender, age, or cultural background.

- Rehearse as a group–more than once. Keep rehearsing until you have seamless transitions between speakers. Ensure you thank the previous speaker and introduce the one following you. If you are rehearsing online, but have to present in-person, try to schedule some face-to-face time that will allow you to physically practice using the technology and classroom space of the campus.

Writing Your Presentation

Approach the oral presentation task just as you would any other assignment. Review the available topics and then do some background reading and research to ensure you can talk about the topic for the appropriate length of time and in an informed manner. Break the question down into manageable parts .

Creating a presentation differs from writing an essay in that the information in the speech must align with the visual aid. Therefore, with each idea, concept, or new information that you write, you need to think about how this might be visually displayed through minimal text and the occasional use of images. Proceed to write your ideas in full, but consider that not all information will end up on a PowerPoint slide. Many guides, such as Marsen (2020), will suggest no more than five points per slide, with each bullet point have no more than six words (for a maximum of 30 words per slide). After all, it is you who are doing the presenting , not the PowerPoint. Your presentation skills are being evaluated, but this evaluation may include only a small percentage for the actual visual aid: check your assessment guidelines.

Using Visual Aids

To keep your audience engaged and help them to remember what you have to say, you may want to use visual aids, such as slides.

When designing slides for your presentation, make sure:

- any text is brief, grammatically correct and easy to read. Use dot points and space between lines, plus large font size (18-20 point)

- Resist the temptation to use dark slides with a light-coloured font; it is hard on the eyes

- if images and graphs are used to support your main points, they should be non-intrusive on the written work

Images and Graphs

- Your audience will respond better to slides that deliver information quickly – images and graphs are a good way to do this. However, they are not always appropriate or necessary.

When choosing images, it’s important to find images that:

- support your presentation and aren’t just decorative

- are high quality, however, using large HD picture files can make the PowerPoint file too large overall for submission via Turnitin

- you have permission to use (Creative Commons license, royalty-free, own images, or purchased)

- suggested sites for free-to-use images: Openclipart – Clipping Culture ; Beautiful Free Images & Pictures | Unsplash ; Pxfuel – Royalty free stock photos free download ; When we share, everyone wins – Creative Commons

The specific requirements for your papers may differ. Again, ensure that you read through any assignment requirements carefully and ask your lecturer or tutor if you’re unsure how to meet them.

Using Visual Aids Effectively

Too often, students make an impressive PowerPoint though do not understand how to use it effectively to enhance their presentation.

- Rehearse with the PowerPoint.

- Keep the slides synchronized with your presentation; change them at the appropriate time.

- Refer to the information on the slides. Point out details; comment on images; note facts such as data.

- Don’t let the PowerPoint just be something happening in the background while you speak.

- Write notes in your script to indicate when to change slides or which slide number the information applies to.

- Pace yourself so you are not spending a disproportionate amount of time on slides at the beginning of the presentation and racing through them at the end.

- Practice, practice, practice.

Nonverbal Communication

It is clear by the name that nonverbal communication includes the ways that we communicate without speaking. You use nonverbal communication everyday–often without thinking about it. Consider meeting a friend on the street: you may say “hello”, but you may also smile, wave, offer your hand to shake, and the like. Here are a few tips that relate specifically to oral presentations.

Being confident and looking confident are two different things. Even if you may be nervous (which is natural), the following will help you look confident and professional:

- Avoid slouching or leaning – standing up straight instantly gives you an air of confidence, but more importantly it allows you to breathe freely. Remember that breathing well allows you to project your voice, but it also prevents your body from experiencing extra stress.

- If you have the space, move when appropriate. You can, for example, move to gesture to a more distant visual aid or to get closer to different part of the audience who might be answering a question.

- If you’re someone who “speaks with their hands”, resist the urge to gesticulate constantly. Use gestures purposefully to highlight, illustrate, motion, or the like.

- Be animated, but don’t fidget. Ask someone to watch you rehearse and identify if you have any nervous, repetitive habits you may be unaware of, such as ‘finger-combing’ your hair or touching your face.

- Avoid ‘verbal fidgets’ such as “umm” or “ahh”; silence is ok. If you needs to cough or clear your throat, do so once then take a drink of water.

- Avoid distractions that you can control. Put your phone on “do not disturb” or turn it off completely.

- Keep your distance. Don’t hover over front-row audience members.

- Have a cheerful demeaner. Remember that your audience will mirror your demeanor.

- Maintain an engaging tone in your voice, by varying tone, pace, and emphasis. Match emotion to concept; slow when concepts might be difficult; stress important words.

- Don’t read your presentation–present it! Internalize your script so you can speak with confidence and only occasionally refer to your notes if needed.

- Make eye contact with your audience members so they know you are talking with them, not at them. You’re having a conversation. Watch the link below for some great speaking tips, including eye contact.

Below is a video of some great tips about public speaking from Amy Wolff at TEDx Portland [1]

- Wolff. A. [The Oregonion]. (2016, April 9). 5 public speaking tips from TEDxPortland speaker coach [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JNOXZumCXNM&ab_channel=TheOregonian ↵

Two or more people tied by marriage, blood, adoption, or choice; living together or apart by choice or circumstance; having interaction within family roles; creating and maintaining a common culture; being characterized by economic cooperation; deciding to have or not to have children, either own or adopted; having boundaries; and claiming mutual affection.

Chapter 3: Oral Presentations Copyright © 2023 by Patricia Williamson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Practical Law

Presentation skills: the basics

Practical law uk practice note w-020-4042 (approx. 7 pages).

- Presenting your department's strategic plan to the organisation's board.

- Addressing shareholders at your organisation's AGM.

- Explaining to the organisation what the legal function does and how it contributes to wider business goals.

- Addressing the media, possibly in response to a crisis.

- Speaking at industry conferences, either as a speaker or chair of a panel.

Effective ways to prepare for a presentation

Research your audience.

- What aspect of your subject area are the audience most interested in?

- How well informed about the subject are the audience?

- Are the audience interested in the subject from a particular perspective (for example, from a finance, legal, marketing or other viewpoint)?

What are the key takeaways

Plan your presentation.

- Tell them what you are going to tell them. Introduce your big idea at the outset and explain that your presentation will enlarge on that theme.

- Tell them. This is the main body of your presentation.

- Tell them what you have told them. When you reach the end of the main body, summarise by repeating your core theme, this time with the supporting points in short, bullet point style.

Chairing a panel

Organise a preparation call.

- Are going to be relevant on content.

- Stick to the panel topic.

- Have considered what they are going to say.

- Do not overlap on content.

- Have enough (but not too much) to say in the time allotted to them.

Starting the session

Moderating the discussion.

"Alex, that's a really interesting point; and one I've struggled with. Cameron, what's your view on this?"

"That sounds great, Evan. So, if I've understood correctly, in a nutshell…"

Q&A session

- Communicate and train

- Managing ethics and culture

This resource is continually monitored and revised for any necessary changes due to legal, market, or practice developments. Any significant developments affecting this resource will be described below.

- United Kingdom

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

In the social and behavioral sciences, an oral presentation assignment involves an individual student or group of students verbally addressing an audience on a specific research-based topic, often utilizing slides to help audience members understand and retain what they both see and hear. The purpose is to inform, report, and explain the significance of research findings, and your critical analysis of those findings, within a specific period of time, often in the form of a reasoned and persuasive argument. Oral presentations are assigned to assess a student’s ability to organize and communicate relevant information effectively to a particular audience. Giving an oral presentation is considered an important learning skill because the ability to speak persuasively in front of an audience is transferable to most professional workplace settings.

Oral Presentations. Learning Co-Op. University of Wollongong, Australia; Oral Presentations. Undergraduate Research Office, Michigan State University; Oral Presentations. Presentations Research Guide, East Carolina University Libraries; Tsang, Art. “Enhancing Learners’ Awareness of Oral Presentation (Delivery) Skills in the Context of Self-regulated Learning.” Active Learning in Higher Education 21 (2020): 39-50.

Preparing for Your Oral Presentation

In some classes, writing the research paper is only part of what is required in reporting the results your work. Your professor may also require you to give an oral presentation about your study. Here are some things to think about before you are scheduled to give a presentation.

1. What should I say?

If your professor hasn't explicitly stated what the content of your presentation should focus on, think about what you want to achieve and what you consider to be the most important things that members of the audience should know about your research. Think about the following: Do I want to inform my audience, inspire them to think about my research, or convince them of a particular point of view? These questions will help frame how to approach your presentation topic.

2. Oral communication is different from written communication

Your audience has just one chance to hear your talk; they can't "re-read" your words if they get confused. Focus on being clear, particularly if the audience can't ask questions during the talk. There are two well-known ways to communicate your points effectively, often applied in combination. The first is the K.I.S.S. method [Keep It Simple Stupid]. Focus your presentation on getting two to three key points across. The second approach is to repeat key insights: tell them what you're going to tell them [forecast], tell them [explain], and then tell them what you just told them [summarize].

3. Think about your audience

Yes, you want to demonstrate to your professor that you have conducted a good study. But professors often ask students to give an oral presentation to practice the art of communicating and to learn to speak clearly and audibly about yourself and your research. Questions to think about include: What background knowledge do they have about my topic? Does the audience have any particular interests? How am I going to involve them in my presentation?

4. Create effective notes

If you don't have notes to refer to as you speak, you run the risk of forgetting something important. Also, having no notes increases the chance you'll lose your train of thought and begin relying on reading from the presentation slides. Think about the best ways to create notes that can be easily referred to as you speak. This is important! Nothing is more distracting to an audience than the speaker fumbling around with notes as they try to speak. It gives the impression of being disorganized and unprepared.

NOTE: A good strategy is to have a page of notes for each slide so that the act of referring to a new page helps remind you to move to the next slide. This also creates a natural pause that allows your audience to contemplate what you just presented.

Strategies for creating effective notes for yourself include the following:

- Choose a large, readable font [at least 18 point in Ariel ]; avoid using fancy text fonts or cursive text.

- Use bold text, underlining, or different-colored text to highlight elements of your speech that you want to emphasize. Don't over do it, though. Only highlight the most important elements of your presentation.

- Leave adequate space on your notes to jot down additional thoughts or observations before and during your presentation. This is also helpful when writing down your thoughts in response to a question or to remember a multi-part question [remember to have a pen with you when you give your presentation].

- Place a cue in the text of your notes to indicate when to move to the next slide, to click on a link, or to take some other action, such as, linking to a video. If appropriate, include a cue in your notes if there is a point during your presentation when you want the audience to refer to a handout.

- Spell out challenging words phonetically and practice saying them ahead of time. This is particularly important for accurately pronouncing people’s names, technical or scientific terminology, words in a foreign language, or any unfamiliar words.

Creating and Using Overheads. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Kelly, Christine. Mastering the Art of Presenting. Inside Higher Education Career Advice; Giving an Oral Presentation. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra; Lucas, Stephen. The Art of Public Speaking . 12th edition. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2015; Peery, Angela B. Creating Effective Presentations: Staff Development with Impact . Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Education, 2011; Peoples, Deborah Carter. Guidelines for Oral Presentations. Ohio Wesleyan University Libraries; Perret, Nellie. Oral Presentations. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Speeches. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Storz, Carl et al. Oral Presentation Skills. Institut national de télécommunications, EVRY FRANCE.

Organizing the Content

In the process of organizing the content of your presentation, begin by thinking about what you want to achieve and how are you going to involve your audience in the presentation.

- Brainstorm your topic and write a rough outline. Don’t get carried away—remember you have a limited amount of time for your presentation.

- Organize your material and draft what you want to say [see below].

- Summarize your draft into key points to write on your presentation slides and/or note cards and/or handout.

- Prepare your visual aids.

- Rehearse your presentation and practice getting the presentation completed within the time limit given by your professor. Ask a friend to listen and time you.

GENERAL OUTLINE

I. Introduction [may be written last]

- Capture your listeners’ attention . Begin with a question, an amusing story, a provocative statement, a personal story, or anything that will engage your audience and make them think. For example, "As a first-gen student, my hardest adjustment to college was the amount of papers I had to write...."

- State your purpose . For example, "I’m going to talk about..."; "This morning I want to explain…."

- Present an outline of your talk . For example, “I will concentrate on the following points: First of all…Then…This will lead to…And finally…"

II. The Body

- Present your main points one by one in a logical order .

- Pause at the end of each point . Give people time to take notes, or time to think about what you are saying.

- Make it clear when you move to another point . For example, “The next point is that...”; “Of course, we must not forget that...”; “However, it's important to realize that....”

- Use clear examples to illustrate your points and/or key findings .

- If appropriate, consider using visual aids to make your presentation more interesting [e.g., a map, chart, picture, link to a video, etc.].

III. The Conclusion

- Leave your audience with a clear summary of everything that you have covered.

- Summarize the main points again . For example, use phrases like: "So, in conclusion..."; "To recap the main issues...," "In summary, it is important to realize...."

- Restate the purpose of your talk, and say that you have achieved your aim : "My intention was ..., and it should now be clear that...."

- Don't let the talk just fizzle out . Make it obvious that you have reached the end of the presentation.

- Thank the audience, and invite questions : "Thank you. Are there any questions?"

NOTE: When asking your audience if anyone has any questions, give people time to contemplate what you have said and to formulate a question. It may seem like an awkward pause to wait ten seconds or so for someone to raise their hand, but it's frustrating to have a question come to mind but be cutoff because the presenter rushed to end the talk.

ANOTHER NOTE: If your last slide includes any contact information or other important information, leave it up long enough to ensure audience members have time to write the information down. Nothing is more frustrating to an audience member than wanting to jot something down, but the presenter closes the slides immediately after finishing.

Creating and Using Overheads. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Giving an Oral Presentation. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra; Lucas, Stephen. The Art of Public Speaking . 12th ed. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2015; Peery, Angela B. Creating Effective Presentations: Staff Development with Impact . Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Education, 2011; Peoples, Deborah Carter. Guidelines for Oral Presentations. Ohio Wesleyan University Libraries; Perret, Nellie. Oral Presentations. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Speeches. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Storz, Carl et al. Oral Presentation Skills. Institut national de télécommunications, EVRY FRANCE.

Delivering Your Presentation

When delivering your presentation, keep in mind the following points to help you remain focused and ensure that everything goes as planned.

Pay Attention to Language!

- Keep it simple . The aim is to communicate, not to show off your vocabulary. Using complex words or phrases increases the chance of stumbling over a word and losing your train of thought.

- Emphasize the key points . Make sure people realize which are the key points of your study. Repeat them using different phrasing to help the audience remember them.

- Check the pronunciation of difficult, unusual, or foreign words beforehand . Keep it simple, but if you have to use unfamiliar words, write them out phonetically in your notes and practice saying them. This is particularly important when pronouncing proper names. Give the definition of words that are unusual or are being used in a particular context [e.g., "By using the term affective response, I am referring to..."].

Use Your Voice to Communicate Clearly

- Speak loud enough for everyone in the room to hear you . Projecting your voice may feel uncomfortably loud at first, but if people can't hear you, they won't try to listen. However, moderate your voice if you are talking in front of a microphone.

- Speak slowly and clearly . Don’t rush! Speaking fast makes it harder for people to understand you and signals being nervous.

- Avoid the use of "fillers." Linguists refer to utterances such as um, ah, you know, and like as fillers. They occur most often during transitions from one idea to another and, if expressed too much, are distracting to an audience. The better you know your presentation, the better you can control these verbal tics.

- Vary your voice quality . If you always use the same volume and pitch [for example, all loud, or all soft, or in a monotone] during your presentation, your audience will stop listening. Use a higher pitch and volume in your voice when you begin a new point or when emphasizing the transition to a new point.

- Speakers with accents need to slow down [so do most others]. Non-native speakers often speak English faster than we slow-mouthed native speakers, usually because most non-English languages flow more quickly than English. Slowing down helps the audience to comprehend what you are saying.

- Slow down for key points . These are also moments in your presentation to consider using body language, such as hand gestures or leaving the podium to point to a slide, to help emphasize key points.

- Use pauses . Don't be afraid of short periods of silence. They give you a chance to gather your thoughts, and your audience an opportunity to think about what you've just said.

Also Use Your Body Language to Communicate!

- Stand straight and comfortably . Do not slouch or shuffle about. If you appear bored or uninterested in what your talking about, the audience will emulate this as well. Wear something comfortable. This is not the time to wear an itchy wool sweater or new high heel shoes for the first time.

- Hold your head up . Look around and make eye contact with people in the audience [or at least pretend to]. Do not just look at your professor or your notes the whole time! Looking up at your your audience brings them into the conversation. If you don't include the audience, they won't listen to you.

- When you are talking to your friends, you naturally use your hands, your facial expression, and your body to add to your communication . Do it in your presentation as well. It will make things far more interesting for the audience.

- Don't turn your back on the audience and don't fidget! Neither moving around nor standing still is wrong. Practice either to make yourself comfortable. Even when pointing to a slide, don't turn your back; stand at the side and turn your head towards the audience as you speak.

- Keep your hands out of your pocket . This is a natural habit when speaking. One hand in your pocket gives the impression of being relaxed, but both hands in pockets looks too casual and should be avoided.

Interact with the Audience

- Be aware of how your audience is reacting to your presentation . Are they interested or bored? If they look confused, stop and ask them [e.g., "Is anything I've covered so far unclear?"]. Stop and explain a point again if needed.

- Check after highlighting key points to ask if the audience is still with you . "Does that make sense?"; "Is that clear?" Don't do this often during the presentation but, if the audience looks disengaged, interrupting your talk to ask a quick question can re-focus their attention even if no one answers.

- Do not apologize for anything . If you believe something will be hard to read or understand, don't use it. If you apologize for feeling awkward and nervous, you'll only succeed in drawing attention to the fact you are feeling awkward and nervous and your audience will begin looking for this, rather than focusing on what you are saying.

- Be open to questions . If someone asks a question in the middle of your talk, answer it. If it disrupts your train of thought momentarily, that's ok because your audience will understand. Questions show that the audience is listening with interest and, therefore, should not be regarded as an attack on you, but as a collaborative search for deeper understanding. However, don't engage in an extended conversation with an audience member or the rest of the audience will begin to feel left out. If an audience member persists, kindly tell them that the issue can be addressed after you've completed the rest of your presentation and note to them that their issue may be addressed later in your presentation [it may not be, but at least saying so allows you to move on].

- Be ready to get the discussion going after your presentation . Professors often want a brief discussion to take place after a presentation. Just in case nobody has anything to say or no one asks any questions, be prepared to ask your audience some provocative questions or bring up key issues for discussion.

Amirian, Seyed Mohammad Reza and Elaheh Tavakoli. “Academic Oral Presentation Self-Efficacy: A Cross-Sectional Interdisciplinary Comparative Study.” Higher Education Research and Development 35 (December 2016): 1095-1110; Balistreri, William F. “Giving an Effective Presentation.” Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 35 (July 2002): 1-4; Creating and Using Overheads. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Enfield, N. J. How We Talk: The Inner Workings of Conversation . New York: Basic Books, 2017; Giving an Oral Presentation. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra; Lucas, Stephen. The Art of Public Speaking . 12th ed. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2015; Peery, Angela B. Creating Effective Presentations: Staff Development with Impact . Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield Education, 2011; Peoples, Deborah Carter. Guidelines for Oral Presentations. Ohio Wesleyan University Libraries; Perret, Nellie. Oral Presentations. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Speeches. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Storz, Carl et al. Oral Presentation Skills. Institut national de télécommunications, EVRY FRANCE.

Speaking Tip

Your First Words are Your Most Important Words!

Your introduction should begin with something that grabs the attention of your audience, such as, an interesting statistic, a brief narrative or story, or a bold assertion, and then clearly tell the audience in a well-crafted sentence what you plan to accomplish in your presentation. Your introductory statement should be constructed so as to invite the audience to pay close attention to your message and to give the audience a clear sense of the direction in which you are about to take them.

Lucas, Stephen. The Art of Public Speaking . 12th edition. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2015.

Another Speaking Tip

Talk to Your Audience, Don't Read to Them!

A presentation is not the same as reading a prepared speech or essay. If you read your presentation as if it were an essay, your audience will probably understand very little about what you say and will lose their concentration quickly. Use notes, cue cards, or presentation slides as prompts that highlight key points, and speak to your audience . Include everyone by looking at them and maintaining regular eye-contact [but don't stare or glare at people]. Limit reading text to quotes or to specific points you want to emphasize.

- << Previous: Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Next: Group Presentations >>

- Last Updated: Mar 6, 2024 1:00 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

24 Oral Presentations

Many academic courses require students to present information to their peers and teachers in a classroom setting. This is usually in the form of a short talk, often, but not always, accompanied by visual aids such as a power point. Students often become nervous at the idea of speaking in front of a group.

This chapter is divided under five headings to establish a quick reference guide for oral presentations.

A beginner, who may have little or no experience, should read each section in full.

For the intermediate learner, who has some experience with oral presentations, review the sections you feel you need work on.

The Purpose of an Oral Presentation

Generally, oral presentation is public speaking, either individually or as a group, the aim of which is to provide information, entertain, persuade the audience, or educate. In an academic setting, oral presentations are often assessable tasks with a marking criteria. Therefore, students are being evaluated on their capacity to speak and deliver relevant information within a set timeframe. An oral presentation differs from a speech in that it usually has visual aids and may involve audience interaction; ideas are both shown and explained . A speech, on the other hand, is a formal verbal discourse addressing an audience, without visual aids and audience participation.

Types of Oral Presentations

Individual presentation.

- Breathe and remember that everyone gets nervous when speaking in public. You are in control. You’ve got this!

- Know your content. The number one way to have a smooth presentation is to know what you want to say and how you want to say it. Write it down and rehearse it until you feel relaxed and confident and do not have to rely heavily on notes while speaking.

- Eliminate ‘umms’ and ‘ahhs’ from your oral presentation vocabulary. Speak slowly and clearly and pause when you need to. It is not a contest to see who can race through their presentation the fastest or fit the most content within the time limit. The average person speaks at a rate of 125 words per minute. Therefore, if you are required to speak for 10 minutes, you will need to write and practice 1250 words for speaking. Ensure you time yourself and get it right.

- Ensure you meet the requirements of the marking criteria, including non-verbal communication skills. Make good eye contact with the audience; watch your posture; don’t fidget.

- Know the language requirements. Check if you are permitted to use a more casual, conversational tone and first-person pronouns, or do you need to keep a more formal, academic tone?

Group Presentation

- All of the above applies, however you are working as part of a group. So how should you approach group work?

- Firstly, if you are not assigned to a group by your lecturer/tutor, choose people based on their availability and accessibility. If you cannot meet face-to-face you may schedule online meetings.

- Get to know each other. It’s easier to work with friends than strangers.

- Also consider everyone’s strengths and weaknesses. This will involve a discussion that will often lead to task or role allocations within the group, however, everyone should be carrying an equal level of the workload.