What is Creative Research?

What is "creative" or "artistic" research how is it defined and evaluated how is it different from other kinds of research who participates and in what ways - and how are its impacts understood across various fields of inquiry.

After more than two decades of investigation, there is no singular definition of “creative research,” no prescribed or prevailing methodology for yielding practice-based research outcomes, and no universally applied or accepted methodology for assessing such outcomes. Nor do we think there should be.

We can all agree that any type of serious, thoughtful creative production is vital. But institutions need rubrics against which to assess outcomes. So, with the help of the Faculty Research Working Group, we have developed a working definition of creative research which centers inquiry while remaining as broad as possible:

Creative research is creative production that produces new knowledge through an interrogation/disruption of form vs. creative production that refines existing knowledge through an adaptation of convention. It is often characterized by innovation, sustained collaboration and inter/trans-disciplinary or hybrid praxis, challenging conventional rubrics of evaluation and assessment within traditional academic environments.

This is where Tisch can lead.

Artists are natural adapters and translators in the work of interpretation and meaning-making, so we are uniquely qualified to create NEW research paradigms along with appropriate and rigorous methods of assessment. At the same time, because of Tisch's unique position as a professional arts-training school within an R1 university, any consideration of "artistic" or "creative research" always references the rigorous standards of the traditional scholarship also produced here.

The long-term challenge is two-fold. Over the long-term, Tisch will continue to refine its evaluative processes that reward innovation, collaboration, inter/trans-disciplinary and hybrid praxis. At the same time, we must continue to incentivize faculty and student work that is visionary and transcends the obstacles of convention.

As the research nexus for Tisch, our responsibility is to support the Tisch community as it embraces these challenges and continues to educate the next generation of global arts citizens.

Emerging Methods: Creative Research Examples

by Janet Salmons

Dr. Salmons is the Research Community Manager for Sage Research Methods Community. Her most recent book from SAGE Publishing is Doing Qualitative Research Online , which discusses using creative methods online. If ordering from SAGE, use MSPACEQ422 for a 20% discount, valid through the end of December 2022.

Visual and arts-based methods have used in research for a very long time.

Visual and arts-based methods of research have been part of many methodological traditions for a very long time. From the moment that cameras were invented they have been used as research tools. Researchers documented research sites, events, and participants, even though early cameras were unwieldy. Researchers used elicitation methods with photographs and artifacts to generate discussions about meanings and cultural significance. Arts-based methods extended the possibility for rich exchange by inviting participants to express themselves in ways that expand on what could be spoken in an interview response. While many of these approaches are qualitative, quantitative researchers have also long studied visual and artistic materials.

Still, with cameras on our phones that can record images or video, scanned images in databases, and the ability to share arts experiences online, new opportunities for creative approaches continue to emerge. These methods are extending beyond origins in fields such as cultural anthropology, psychology, and sociology and are now used in almost any social science field. Creative methods are used online, in-person, or in hybrid research.

We showcase creative research methods on Sage Research Methods Community, including photovoice , collage , poetry , visual journaling , multimodal visual methods and more . Dr. Helen Kara , author of several books about creative methods, has served as a Mentor in Residence and regular contributor.

It is important to include creative methods in this month’s focus on new and emerging ways to conduct research. This multidisciplinary collection of recent open-access articles demonstrates the rich variety of artistic and creative ways researchers are engaging with participants.

Using Arts-Based and Creative Methods in New Ways

Andrä, c. (2022). crafting stories, making peace creative methods in peace research . millennium, 50(2), 494–523. https://doi.org/10.1177/03058298211063510.

Abstract. This article examines the analytical and political potentials of creative methods for peace research. Specifically, the article argues that creative methods can textile, i.e. render material and irregularly textured, (research on) post-conflict politics. Grounded in a collaborative research project with former combatants in Colombia, the article takes this project’s methods – narrative practice, textile-making, and a travelling exhibition – as examples to demonstrate how creative methods’ element of making contributes to the development of post-conflict subjectivities and relationships. Casting the data generated by creative methods as crafted stories, the article also shows how in these stories, semantic meaning becomes entangled with material traces of emotional, affective, and embodied experiences of violence and its aftermath, effecting a shift in the post-conflict distribution of the sensible. By exploring creative methods’ capacity for textiling peace (research), the article contributes to research on creativity, the arts, and peace and on the post-conflict trajectories of former combatants.

Balmer, A. (2021). Painting with data: Alternative aesthetics of qualitative research . The Sociological Review, 69(6), 1143–1161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026121991787

Abstract. In this article I outline an original creative method for qualitative research, namely the painting with data technique. This is a participatory methodology which brings creativity and participation through to the analytical phase of qualitative research. Crucially, I acknowledge but also challenge the dominant aesthetic that currently shapes qualitative research and renders life in a monochromatic palette. The painting with data method evidences an alternative aesthetic to the predominant one and I argue that we can understand this methodology by adapting Jennifer Mason’s concept of ‘layering’ to conceptualise how different aesthetics help us to see the different shapes, forms and moulds that make us, our relationships and our worlds. The process moves away from traditional ways of treating transcribed data, and prioritises addition above extraction; juxtaposition over thematisation; and collaging rather than ordering. This alternative aesthetic for qualitative research offers an evocative form and a conceptual schema through which to interpret the world, providing a route to novel insights, that enlivens the interpretative work of the analyst and offers opportunities to make and witness potent connections.

Dahal, P., Joshi, S. K., & Swahnberg, K. (2021). Does Forum Theater Help Reduce Gender Inequalities and Violence? Findings From Nepal . Journal of Interpersonal Violence. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260521997457

Abstract. Gender inequality and violence against women are present in every society and culture around the world. The intensities vary, however, based on the local guiding norms and established belief systems. The society of Nepal is centered on traditional belief systems of gender roles and responsibilities, providing greater male supremacy and subordination for the females. This has led to the development and extensive practices of social gender hierarchal systems, producing several inequalities and violence toward women. This study has utilized Forum Theater interventions as a method of raising awareness in 10 villages in eastern Nepal. The study aimed to understand the perception and changes in the community and individuals from the interactive Forum Theater performances on pertinent local gender issues. We conducted 6 focus group discussions and 30 individual interviews with male and female participants exposed to the interventions. The data analysis utilized the constructivist grounded theory methodology. The study finds that exposure and interactive participation in the Forum Theater provide the audience with knowledge, develop empathy toward the victim, and motivate them to change the situation of inequality, abuse, and violence using dialogues and negotiations. The study describes how participation in Forum Theater has increased individual’s ability for negotiating changes. The engagement by the audience in community discussions and replication of efforts in one of the intervention sites show the level of preparedness and ownership among the targeted communities. The study shows the methodological aspects of the planning and performance of the Forum Theater and recommends further exploration of the use of Forum Theater in raising awareness.

Earle-Brown, H. (2021). Little Miss Homeless: creative methods for research impact . Cultural Geographies, 28(2), 409–415. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474020987244

Abstract. Women’s homelessness is a significant and increasing problem in the UK. Yet, much research on homelessness does not acknowledge the particular gendered issues homeless women face. Furthermore, the small amount of research available on the matter is often restricted to academic and professional audiences. Little Miss Homeless, a culture jammed children’s book, was produced with the intention of making wider public audiences aware and engaged with issues relating to women’s homelessness. This article traces through the process of producing the book and reflects on the emerging interest within cultural geography to use creative methods of research dissemination in order to engage wider public audiences with our research.

Harrison, K., & Ogden, C. A. (2021). ‘ Knit “n” natter’: a feminist methodological assessment of using creative ‘women’s work’ in focus groups . Qualitative Research, 21(5), 633–649. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794120945133

Abstract. This article outlines the methodological innovations generated in a study of knitting and femininity in Britain. The study utilised ‘knit “n” natter’ focus groups during which female participants were encouraged to knit and talk. The research design encompassed a traditionally undervalued form of domestic ‘women’s work’ to recognise the creative skills of female practitioners. ‘Knit “n” natter’ is a fruitful feminist research method in relation to its capitalisation on female participants’ creativity, its disruption of expertise and its feminisation of academic space. The method challenges patriarchal conventions of knowledge production and gendered power relations in research, but it also reproduces problematic constructions of gender, which are acknowledged. The study contributes to a growing body of work on creative participatory methods and finds that the ‘knit “n” natter’ format has utility beyond investigations of crafting and may be used productively in other contexts where in-depth research with women is desirable.

Goldman, A., Gervis, M., & Griffiths, M. (2022). Emotion mapping: Exploring creative methods to understand the psychology of long-term injury . Methodological Innovations , 15 (1), 16–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/20597991221077924

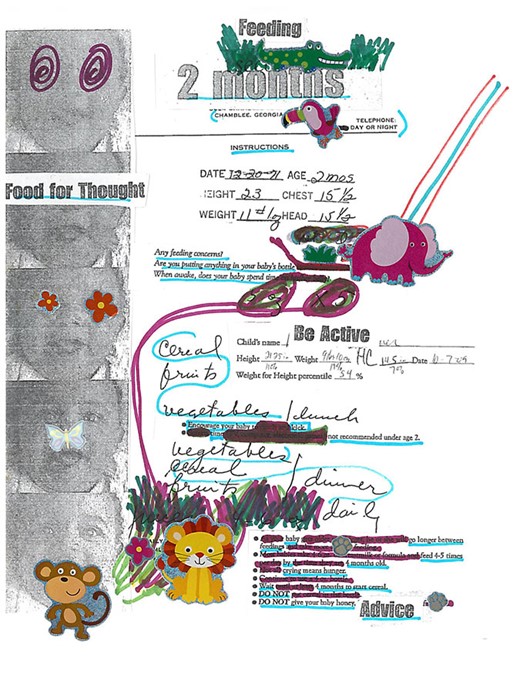

Abstract. This methodological study details the effectiveness of emotion mapping as a method to explore the lived experiences of professional male athletes ( n = 9) with a long-term injury. This represents the first use of emotion mapping to garner phenomenal knowledge on long-term injury within a sport psychology context, and as such is a departure from traditional approaches in this field. Following an orientation meeting, each participant was asked to produce an emotion map in the privacy of their home of two critical spaces occupied during their rehabilitation. Using video conferencing software, they were then asked to narrate their map, to facilitate understanding of their lived experiences of injury. Overall, the method was found to be efficacious in supporting existing literature on injury and revealing previously unknown aspects of long-term injury. In particular, the study provided phenomenal knowledge that was previously absent. As such, recommendations are made for the use of emotion mapping both as an effective research technique, and as a therapeutic tool.

Lahman, M. K. E., De Oliveira, B., Cox, D., Sebastian, M. L., Cadogan, K., Rundle Kahn, A., Lafferty, M., Morgan, M., Thapa, K., Thomas, R., & Zakotnik-Gutierrez, J. (2021). Own Your Walls: Portraiture and Researcher Reflexive Collage Self-Portraits . Qualitative Inquiry, 27(1), 136–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800419897699

Abstract. As part of an advanced doctoral research course, class members participated in an in-depth exploration of the methodology portraiture. In this article, the authors—course instructor and 10 students—represent themselves as researchers through collage portraits and written reflexive responses. A brief review of portraiture, collage in research, and researcher reflexivity, along with descriptions of relevant course experiences are presented. Images of the collage process and resulting portraits are highlighted. A collage portrait of a class emerges as issues of transparency in research, the role of the researcher, and the use of art in research are explored.

Manuel, J., & Vigar, G. (2021). Enhancing citizen engagement in planning through participatory film-making . Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science, 48(6), 1558–1573. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399808320936280

Abstract. There is a long history of engaging citizens in planning processes, and the intention to involve them actively in planning is a common objective. However, the reality of doing so is rather fraught and much empirical work suggests poor results. Partly in response an increasingly sophisticated toolkit of methods has emerged, and, in recent years, the deployment of various creative and digital technologies has enhanced this toolkit. We report here on case study research that deployed participatory film-making to augment a process of neighbourhood planning. We conclude that such a technology can elicit issues that might be missed in traditional planning processes; provoke key actors to include more citizens in the process by highlighting existing absences in the knowledge base; and, finally, provoke greater deliberation on issues by providing spaces for reflection and debate. We note, however, that while participants in film-making were positive about the experience, such creative methods were side-lined as established forms of technical–rational planning reasserted themselves.

Parsons, L. T., & Pinkerton, L. (2022). Poetry and prose as methodology: A synergy of knowing. Methodological Innovations. https://doi.org/10.1177/20597991221087150

Abstract. In this study, situated in the borderland between traditional and artistic methodologies, we innovatively represent our research findings in both prose and poetry. This is an act of exploration and resistance to hegemonic assumptions about legitimate research writing. A content analysis of young adult literature featuring trafficked child soldiers is the vehicle through which we advocate for the simultaneous use of prose and poetry. Several overarching insights emerged from this work as our prose and poetic representations, taken together, did more than either could have done on its own. We noted significant differences in scope, impact, and use of words when representing findings in the two forms. Additionally, independently selecting many of the same quotes as we created our separate representations contributed to the validity of the analysis. We saw very concretely that what one knows in one form one might know differently in another, generating a synergy of knowing.

Using Visual Methods in Research: Podcast and Video Interview

The doll’s marriage: an ethnographic encounter with rural children and childhood.

- Transforming Society

- Open access

- Bristol University Press Digital

Sign up for 25% off all books

Creative Research Methods

A Practical Guide

By helen kara.

Visit companion website

Recommend to library

Request e-inspection copy

Watch Helen Kara's YouTube channel

In the media

On our blog: LESSONS FROM LOCKDOWN: Helen Kara on research

- Description

Creative research methods can help to answer complex contemporary questions which are hard to answer using conventional methods alone. Creative methods can also be more ethical, helping researchers to address social injustice.

This bestselling book, now in its second edition, is the first to identify and examine the five areas of creative research methods:

• arts-based research

• embodied research

• research using technology

• multi-modal research

• transformative research frameworks.

Written in an accessible, practical and jargon-free style, with reflective questions, boxed text and a companion website to guide student learning, it offers numerous examples of creative methods in practice from around the world. This new edition includes a wealth of new material, with five extra chapters and over 200 new references. Spanning the gulf between academia and practice, this useful book will inform and inspire researchers by showing readers why, when, and how to use creative methods in their research.

Creative Research Methods has been cited over 750 times.

Helen Kara has been an independent researcher since 1999 and specialises in research methods and ethics. She is the author of Research and Evaluation for Busy Students and Practitioners: A Time-Saving Guide (Policy Press, 2nd ed. 2017) and Research Ethics in the Real World: Euro-Western and Indigenous Perspectives (Policy Press, 2018). Helen is Honorary Senior Research Fellow at the University of Manchester, and Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences.

Introducing Creative Research

Creative Research Methods in Practice

Transformative Research Frameworks and Indigenous Research

Creative Research Methods and Ethics

Creative Thinking

Arts-Based and Embodied Data Gathering

Technology-Based and Multi-Modal Data Gathering

Arts-Based and Embodied Data Analysis

Technology-Based and Multi-Modal Data Analysis

Arts-Based and Embodied Research Reporting

Technology-Based and Multi-Modal Research Reporting

Arts-Based and Embodied Presentation

Technology-Based and Multi-Modal Presentation

From Research Into Practice

Understanding Research for Social Policy and Social Work (Second Edition)

Edited by Saul Becker , Alan Bryman and Harry Ferguson

Find out more

Social Research with Children and Young People

By Louca-Mai Brady and Berni Graham

Doing Qualitative Desk-Based Research

By Barbara Bassot

Doing Your Research Project with Documents

By Aimee Grant

Doing Reflexivity

By Jon Dean

Creative Research Methods in Education

By Helen Kara , Narelle Lemon , Dawn Mannay and Megan McPherson

Critical Criminology and Literary Criticism

By Rafe McGregor

Qualitative and Digital Research in Times of Crisis

Edited by Helen Kara and Su-ming Khoo

Narrative Research Now

Edited by Ashley Barnwell and Signe Ravn

Photovoice Reimagined

By Nicole Brown

The Handbook of Creative Data Analysis

Edited by Helen Kara , Dawn Mannay and Alastair Roy

Fiction and Research

By Becky Tipper and Leah Gilman

Doing Phenomenography

By Amanda Taylor-Beswick and Eva Hornung

Encountering the World with I-docs

By Ella Harris

Embedding Young People's Participation in Health Services

Edited by Louca-Mai Brady

Research Methodologies for the Creative Arts & Humanities: Practice-based & practice-led research

Practice-based & practice-led research.

Known by a variety of terms, practice-led research is a conceptual framework that allows a researcher to incorporate their creative practice, creative methods and creative output into the research design and as a part of the research output.

Smith and Dean note that practice-led research arises out of two related ideas. Firstly, "that creative work in itself is a form of research and generates detectable research outputs" ( 2009, p5 ). The product of creative work itself contributes to the outcomes of a research process and contributes to the answer of a research question. Secondly, "creative practice -- the training and specialised knowledge that creative practitioners have and the processes they engage in when they are making art -- can lead to specialised research insights which can then be generalised and written up as research" ( 2009, p5 ). Smith and Dean's point here is that the content and processes of a creative practice generate knowledge and innovations that are different to, but complementary with, other research styles and methods. Practice-led research projects are undertaken across all creative disciplines and, as a result, the approach is very flexible in its implementation able to incorporate a variety of methodologies and methods within its bounds.

Most commonly, a practice-led research project consists of two components: a creative output and a text component, commonly referred to as an exegesis . The two components are not independent, but interact and work together to address the research question. The ECU guidelines for examiners states that the practice-led approach to research is

... based upon the perspective that creative art practices are alternative forms of knowledge embedded in investigation processes and methodologies of the various disciplines of performance … the visual and audio arts, design and creative writing ( "Guidelines and Examination Report for Examination of Doctor of Philosophy theses in creative research disciplines," para. 1 ).

A helpful way to understand this is to think of practice-led research as an approach that allows you to incorporate your creative practices into the research, legitimises the knowledge they reveal and endorses the methodologies, methods and research tools that are characteristic of your discipline.

Additional advice and guidance on the nature and implementation of a practice-led research project may be sought from your supervisors and from the research consultants .

- Boyes, E. Masquerade of the feminine (2006)

- Clarke, R. What feels true? (2012)

- Ellis, S. Indelible (2005)

- Grocott, L. Design research & reflective practice (2010)

- Hicks, T. Path to abstraction (2011)

- Mafe, D. Rephrasing voice (2009)

- Noon, D. The pink divide (2012)

- Wilkinson, T. Uncertain surrenders (2012)

ECU Library Resources - Practice-Based/ Practice-Led Research

- Art practice as research : inquiry in visual arts

- Art practice in a digital culture

- Artistic practice as research in music : theory, criticism, practice

- Creative research

- Design research through practice : from the lab, field, and showroom

- Live research : methods of practice-led inquiry in performance

- Method meets art : arts-based research practice

- Mapping landscapes for performance as research

- Thinking through practice: art as research in the academy

- Digital research in the arts and humanities

Further Reading

- Practice Based Research: A Guide

- The practical implications of applying a theory of practice based research: a case study

- Evaluating quality practice - led research: still a moving target?

- Creative and practice-led research: current status, future plans

- Developing a Research Procedures Programme for Artists & Designers

- Inquiry through Practice: developing appropriate research strategies

- Illuminating the Exegesis

- A Manifesto for Performative Research.

- The art object does not embody a form of knowledge

- From Practice to the Page: Multi-Disciplinary Understandings of the Written Component of Practice-Led Studies

- Scholarly design as a paradigm for practice-based research

- << Previous: Positivism

- Next: Qualitative research >>

- Action Research

- Case studies

- Constructivism

- Constructivist grounded theory

- Content analysis

- Critical discourse analysis

- Ethnographic research

- Focus groups research

- Grounded theory research

- Historical research

- Longitudinal analysis

- Life histories/ autobiographies

- Media Analysis

- Mixed methodology

- Narrative inquiry research method

- Other related creative arts research methodologies

- Participant observation research

- Practice-based & practice-led research

- Qualitative research

- Quasi-experimental design

- Social constructivism

- Survey research

- Usability studies

- Theses, Books & eBooks

- Subject Headings

- Academic Skills & Research Writing

- Last Updated: Mar 11, 2024 3:12 PM

- URL: https://ecu.au.libguides.com/research-methodologies-creative-arts-humanities

Edith Cowan University acknowledges and respects the Noongar people, who are the traditional custodians of the land upon which its campuses stand and its programs operate. In particular ECU pays its respects to the Elders, past and present, of the Noongar people, and embrace their culture, wisdom and knowledge.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

34 Creative Approaches to Writing Qualitative Research

Sandra L. Faulkner Bowling Green State University Bowling Green, OH, USA

Sheila Squillante Chatham University Pittsburgh, PA, USA

- Published: 02 September 2020

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter addresses the use of creative writing forms and techniques in qualitative research writing. Paying attention to the aesthetics of writing qualitative work may help researchers achieve their goals. The chapter discusses research method, writing forms, voice, and style as they relate to the craft of creative writing in qualitative research. Researchers use creative writing to highlight the aesthetic in their work, as a form of data analysis, and/or as a qualitative research method. Qualitative researchers are asked to consider their research goals, their audience, and how form and structure will suit their research purpose(s) when considering the kind of creative writing to use in their qualitative writing.

Creative Approaches to Writing Qualitative Research

In 2005, Richardson and St. Pierre wrote,

I confessed that for years I had yawned my way through numerous supposedly exemplary studies. Countless number of texts had I abandoned half read, half scanned.… Qualitative research has to be read, not scanned; its meaning is in the reading.… Was there some way in which to create texts that were vital and made a difference? (pp. 959–960)

How can researchers make their qualitative writing and work interesting? If qualitative researchers use the principles of creative writing, will their work be vital? What does it mean to use creative writing in qualitative research? In this chapter, we answer these questions by focusing on the how and the why of doing and using creative writing in qualitative research through the use of writing examples. We will discuss research method, writing forms, voice, and style as they relate to the craft of creative writing in qualitative research. Researchers use creative writing as a way to highlight the aesthetic in their work (Faulkner, 2020 ), as a form of data analysis (Faulkner, 2017b ), and/or as a qualitative research method (e.g., Richardson & St. Pierre, 2005 ). Table 34.1 asks you to consider the kind of creative writing to use in your qualitative research depending on the goals you wish to accomplish, who your audience is, and what form best suits your research purpose(s). Use the table as a guide for planning your next research project.

Notes : We adapted Table 34.1 from Chapter 1 and material from Chapters 2 , 4 , and 6 in Faulkner and Squillante ( 2016 ).

Writing Goals and Considerations

Using creative approaches to writing qualitative work can add interest to your work, be evocative for your audience, and be used to mirror research aims. Answering the questions we ask in Table 34.1 is a good starting point for a process that most likely will not be linear; you may try many forms of writing in any given project to meet your research goals.

You may use poetry to make your work sing, tell an evocative story of research participants, or demonstrate attention to craft and the research process (Faulkner, 2020 ). Faulkner ( 2006 ) used poetry to present 31 lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer Jews’ narratives about being gay and Jewish; the poems showed subjective emotional processes, the difficulties of negotiating identities in fieldwork, and the challenges of conducting interviews while being reflexive and conscious in ways that a prose report could not. Faulkner

wrote poems from interviews, observations, and field notes to embody the experience of being LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer) and Jewish in ways that pay attention to the senses and offer some narrative and poetic truths about the experience of multiple stigmatized identities. (Faulkner, 2018a , p. 85)

There were poems about research method, poems about individual participants, and poems about the experiences of being gay and Jewish.

You may write memoir or a personal or lyrical essay to show a reflexive and embodied research process. In the feminist ethnography Real Women Run (Faulkner, 2018c ), Faulkner wrote one chapter as an autoethnographic memoir of running and her emerging feminist consciousness from grade school to the present, which includes participant observation at the 2014 Gay Games. Scenes of running in everyday contexts, in road races, and with friends, as well as not running because of physical and psychic injuries, are interspersed with the use of haiku as running logs to show her embodied experiences of running while female and to make an aesthetic argument for running as feminist and relational practice.

You may use a visual and text collage to show interesting and nuanced details about your topic that are not readily known or talked about in other sources in ways that you desire. For instance, Faulkner ( n.d. ) created Web-based material for her feminist ethnography on women and running that presents aspects of the embodied fieldwork through sound and image. A video essay, photo and haiku collage, and soundscapes of running as fieldwork are used to help the audience think differently about women and running. The sounds and sights of running—the noise, the grunts, the breathing, the encouragement, the disappointment—jog the audience through training runs, races, and the in situ embodiment of running. In another example of embodied ethnography, Faulkner ( 2016b ) used photos from fieldwork in Germany along with poems to create a series of virtual postcards that include sound, text, and images of fieldwork. The presentation of atypical postcards shows the false dichotomy between the domestic and public spheres, between the private and the public; they show the interplay between power and difference. In a collage on queering sexuality education in family and school, Faulkner, ( 2018c ) uses poetic collage as queer methodology, manipulating headlines of current events around women’s reproductive health and justice, curriculum from liberal sexuality education, and conversations with her daughter about sex and sexuality to critique sexuality education and policies about women’s health in the United States. Autoethnography in the form of dialogue poems between mother and daughter demonstrates reflexivity. Social science “research questions” frame and push the poetic analysis to show critical engagement with sexuality literature, and the collaging of news headlines about sexuality connects personal experience about sexuality education to larger cultural issues.

You may use fiction or an amalgam/composite of participants’ interviews or stories to protect the privacy and confidentiality of research participants, to make your work useful to those outside the academy, and to “present complex, situated accounts from individuals, rather than breaking data down into categories” (Willis, 2019 ). Krizek ( 1998 ) suggested that

ethnographers employ the literary devices of creative writing—yes, even fiction—to develop a sense of dialogue and copresence with the reader. In other words, bring the reader along into the specific setting as a participant and codiscoverer instead of a passive recipient of a descriptive monologue (p. 93).

In Low-Fat Love Stories , Leavy and Scotti ( 2017 ) used short stories and visual portraits to portray interviews with women about dissatisfying relationships. The stories and “textual visual snapshots” are composite characters created from interviews with women. Faulkner and her colleagues used fictional poetry to unmask sexual harassment in the academy using the pop-culture character Hello Kitty as a way to examine taken-for-granted patterns of behavior (Faulkner, Calafell, & Grimes, 2009 ). The poems, presented in the chapbook Hello Kitty Goes to College (Faulkner, 2012a ), portray administrative and faculty reactions to the standpoints of women of color, untenured women faculty, and students’ experiences and narratives of harassment and hostile learning environments through the fictionalized experiences of Hello Kitty. The absurdity of a fictional character as student and professor is used to make the audience examine their implicit assumptions about the academy, to shake them out of usual ways of thought.

The point of using creative writing practices in your qualitative research writing and method is that writing about your research does not have to be tedious. Reading research writing need not put the reader to sleep; using creative writing can make your research more compelling, authentic, and impactful. You can explain your lexicon to those who do not speak it in compelling and artful ways. The use of creative forms can be a form of public scholarship, a way to make your work more accessible and useful (Faulkner & Squillante, 2019 ). Some scholars have remarked on the irony of using academic language to write about personal relationships and use creative forms, such as the personal narrative, the novel, and poetry, as a means of public scholarship and for accessibility (Bochner, 2014 ; Ellis, 2009 ; Faulkner & Squillante, 2016 ). The goals with this work are to use the personal and aesthetic to help others learn, critique, and envision new ways of relating in personal relationships. For example, in Knit Four, Frog One , a collection of poetry about women’s work and family stories, Faulkner ( 2014 ) wrote narratives in different poetic forms (e.g., collage, free verse, dialogue poems, sonnets) to show grandmother–mother–daughter relationships, women’s work, mothering, family secrets, and patterns of communication in close relationships. The poems represent different versions of family stories that reveal patterns of interaction to tell better stories and offer more possibilities for close relationships.

Creative Forms and Qualitative Writing

Writers have a reputation for collecting material from everywhere and with anyone—especially in their personal relationships—and using it in their writing. This is analogous to fieldwork: immersing yourself in the culture you want to study and engaging in participant observation. We embrace the analogy of the writer as ethnographer because it makes the focus on the writing as method and writing as a way of life (Rose, 1990 ). We encourage you to get your feet wet in the field as a writer and ethnographer. An ethnographer writes ethnography, which is both a process and a product—a process of systematically studying a culture and a product, the writing of a culture. Since we are discussing creative writing as method, we encourage you to be an autoethnographer, an ethnographer who uses personal experience “to describe and critique cultural beliefs, practices, and experiences” (Adams, Holman Jones, & Ellis, 2015 , p. 1). An (auto)ethnographer engages in fieldwork. A writer engages in fieldwork through the use of personal experience, participant observation, interviews, archival, library, and online research (Buch & Staller, 2014 ).

You may remember conversations and events that become relevant to your writing. You may write down these conversations and observations. Take photos, selfies, and draw sketches. Sketch poems and collect artifacts. You may post Facebook updates, Instagram and tweet these details, regularly journal, and use that writing in your work. You may keep a theoretical journal during fieldwork and interviews and sketch your understandings in the margins. You may write poetry in your field notes. You may feel unsure how to incorporate the research you do (and live) into your writing; poet Mark Doty ( 2010 ) offered helpful advice:

Not everything can be described, nor need be. The choice of what to evoke, to make any scene seem REAL to the reader, is a crucial one. It might be just those few elements that create both familiarity (what would make, say, a beach feel like a beach?) and surprise (what would rescue that scene from the generic, providing the particular evidence of specificity?). (p. 116)

How to Use Creative Writing to Frame Research (and Vice Versa)

How you incorporate research and personal experience in your work depends on how you want structure and form to work in your writing. The way that scholars who use creative writing in their work cite research and use their personal experience varies: you may include footnotes and endnotes; use a layered text with explicit context, theory, and methodological notes surrounding your poems, prose, and visuals; and sometimes, you may just use the writing.

Some qualitative researchers use dates and epigraphs from historical and research texts in the titles of poems and prose (e.g., Faulkner, 2016a , Panel I: Painting the Church-House Doors Harlot Red on Easter Weekend, 2014) and include chronologies of facts and appendices with endnotes and source material (e.g., Adams, 2011 ; Faulkner, 2012b ), while others use prefaces, appendices, or footnotes with theoretical, methodological, and citational points and prose exposition about the creative writing. Faulkner ( 2016c ) used footnotes of theoretical framings and research literature to critique staid understandings of marriage, interpersonal communication research, and the status quo in an editorial for a special issue on The Promise of Arts-Based, Ethnographic, and Narrative Research in Critical Family Communication Research and Praxis ; all of the academic work was contained in footnotes, so that the story of 10 years of marriage and 10 years of research was highlighted in the main text in 10 sections (an experimental text like we will talk about in the narrative section). In Faulkner’s feminist ethnography, “Postkarten aus Deutschland” (2016b), we see dates included in poem titles, details about cities in poetry lines, and images and places crafted into postcards beside the text. Calafell ( 2007 ) used a letter format to write about mentoring in “Mentoring and Love: An Open Letter” to show faculty of color mentoring students of color as a form of love; the letter form challenges “our understandings of power and hierarchies in these relationships and academia in general” (p. 425).

Writing Form and Structure

Whether you desire to write about an interview as a poem, use personal essay to demonstrate reflexivity in the research process, or create a photoessay about your fieldwork, you must ask yourself some questions before you begin: How will you shape this experience in language so that a reader can connect with it? What scaffolding will you build to support it? How can you arrange your information to leave the correct impression, make the biggest impact? These are questions of form and structure. They are related terms, to be sure, but it is important to understand their distinctions.

When we say form , we can also mean type or genre . For example, essay, poem, and short story are all classic forms in creative writing. Structure refers to the play of language within a form. So, things like chronology, stanza breaks, white space, or even dialogue are structural elements of a text. Think of it like cooking: you have spinach, some eggs, a few tablespoons of sharp cheese. Choose this pan and you have made an omelet; choose that pot and you have soup. Pan or pot is a big decision. Fortunately, you have a big cookbook to flip through for ideas before you light the stove.

To narrate something is to attach a singular voice to a series of actions or thoughts. But it is more than simply voice, isn’t it? Imagine the great narrators of literature and film (e.g., Scout from To Kill a Mockingbird ; Ishmael in Moby Dick ; Ralphie in A Christmas Story ; the Stranger in The Big Lebowski ). They bring their personality, their point of view, their irritations and expectations with them onto the page or screen. Details are not merely flung forth from the narrator’s mind or pen as a string of chronological or sequential happenings. This is no information dump. Rather, a narrative is a shapely thing: organized, polished, curated, its events arranged so that they will reach us, move us. Change us. Simply put, narrative is story .

The evocative narrative as an alternative form of research reporting encourages researchers to transform collected materials into vivid, detailed accounts of lived experience that aims to show how lives are lived, understood, and experienced. The goals of evocative narratives are expressive rather than representational; the communicative significance of this form of research reporting lies in its potential to move readers into the worlds of others, allowing readers to experience these worlds in emotional, even bodily ways. (Kiesigner, 1998 , p. 129)

In the following excerpt from Faulkner’s ( 2016a ) personal narrative written in the form of a triptych about her partner’s cancer, she included scholarly research about a polar vortex, scientific information about the color characteristics of red paint, and historical facts about the church née house she lives in with her family to add nuance and detail to her experience (see Figure 34.1 ). She used library search engines, a goggle search, an interview with a city clerk, her academic background knowledge, and journal articles to find research relevant to social support, weather, and paint. Because Faulkner was writing about cancer, living in a former church, and home as supportive place, the triptych form added another layer and emphasized the role of fate and endurance and resilience in relational difficulties. A triptych is something composed in three sections, such as a work of art like an altarpiece. Constructing the personal narrative as a trilogy with sections—Panel I, Painting the Church-House Doors Harlot Red on Easter Weekend, 2014; Panel II, Talking Cancer, Cookies, and Poetry, Summer Solstice, 2014; Panel III, Knitting a Polar Vortex, January 6–9, 2014—played on the idea of a church-house and story as an altarpiece.

Excerpt from “Cancer Triptych” (Faulkner, 2016a ).

The use of research layered the cancer story; it becomes more than a story of a cancer diagnosis. The story paints the picture of community, social support, and coping.

Memoir and Personal Essay

Memoir is a form that filters and organizes personal events, sifting through to shape and present them in an intentional, mediated, engaging way.

Note, too, what memoir is not : a chronological account of everysinglething that ever happened to you from cradle to grave. That form is called autobiography , and it is normally reserved for people who rule countries or scandalize Hollywood. Mostly, that is not us. Memoir is reflective writing, which tells the true story of one important event or relationship in a person’s life. Autoethnography is a form, which also connects the self with the wider culture. Those who do autoethnography use it to highlight “the ways in which our identities as raced, gendered, aged, sexualized, and classed researchers impact what we see, do, and say” (Jones, Adams, & Ellis, 2013, p. 35).

Besides autobiography, memoir is probably the form most of us think of when we hear personal story . But what is it about this form, in particular, that makes it a good choice for such stories?

From the perspective of the reader, a good memoir does many things. It renders a world using the same tools a novel might: with lush physical details, vivid scenes, a gripping plot, dramatic tension, and dialogue that moves the story forward. It also makes use of exposition —the kind of writing that provides important background information the reader will need to orient themselves within the story. All these elements combine to make for an immersive reading experience, the kind where the scaffolding disappears and the reader slips wholly into the world the writer has created.

But memoir does something else that makes its form distinct from that of a novel or short story. Where for fiction writers we say they should “show, don’t tell,” for memoirists, that maxim becomes “show AND tell.” The memoirist is not only tasked with rendering an experience concretely through sensory writing for the reader, but also required to explain , in a direct way, the importance of that experience at every turn. We call this kind of language reflection . Think of it as the voice of the now-wise author speaking directly to the reader about their insights and revelations, having come through the experience a changed person.

Personal essay is a form that, like memoir, begins with the writer’s self and draws on experiences from their lives. Also like memoir, personal essay uses the tools of fiction—scene, summary, setting, and dialogue—to create a rich sensory world. The difference between these forms is that memoir uses personal experience to look inward , toward the self, and personal essay uses the same experience to look outward at the world.

For instance, let’s say you grew up as a middle child, with a successful older sister and a mischievous younger brother. Your memories of your childhood are filled with moments when you felt invisible in their midst, the classic middle child. There was that one summer when your parents were focused on your sister’s achievements as she applied to Ivy League colleges. Meanwhile, your brother had discovered the local skateboard community and spent his days on the halfpipe behind the grocery store. Most days he came home bleeding, but happy. This was also the summer you started writing poetry and you wanted to read your drafts to anyone who would listen. But your parents were—in your memory—preoccupied with worry about your siblings. They could not sit still long enough to listen to you. You felt neglected and ignored and the feeling has stayed with you throughout your life.

A memoir about this summer would explore your role in the family dynamic and your particular relationships with each player. It would investigate your own complicity in the situation—were they really ignoring you? Are you exaggerating the memory? Did you sometimes enjoy having that solitude, away from their support, possibly, but also away from their scrutiny? Did the experience of learning to rely on yourself lay an important foundation for your nascent adult self? Your memoir about this summer will delve deeply into these questions so that you can learn something important about yourself, and your reader can learn something important about the human condition by reading it.

Take the same material and cast it as a personal essay, however, and you could be investigating the cultural phenomenon of “middle child syndrome.” Perhaps you will interweave moments from that summer with research about birth order psychology to help you, and your reader, understand something important about middle children in general and, by extension, about the world in which humans interact.

Poems, too, can narrate events and had the explicit job of doing so in many cultures for thousands of years. The oral tradition of poetry kept important stories vital for generations and passed historical, political, and sociological information from generation to generation.

Received forms like the epic (which covered many events) and the ballad (which generally celebrated one event) have been used by poets to spin complex tales, which celebrate and memorialize the stuff of human interaction: love, grief, politics, and war. Think of Odysseus’s journeys as recounted in Homer’s great works The Iliad and The Odyssey or of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” as examples of each form, respectively. These forms have survived antiquity and continue, at the hands of the skillful poet, to grip and enthrall readers. Dudley Randall’s 1968 poem, “Ballad of Birmingham,” is a stunning and, sadly, still-relevant lament to racial violence in the American South. Derek Walcott’s 1990 masterpiece, Omeros , is a modern epic that weaves narratives of colonialism, Native American tribal loss, and African displacement over 8,000 lines. Even more recently, the poet Marly Youmans’s 2012 book, Thaliad , offers the survival story of seven children, one of whom is named Thalia, in a postapocalyptic landscape.

Beyond these traditional forms, though, contemporary poets use line and image and stanza to evoke story in less prescribed ways as well. Narrative poems in the 21st century employ many of the same tools that fiction or memoir writers do. They must use setting details to create a specific, sensual world for the poem. They must create engaging characters who interact with one another inside a dynamic scene. There can be dialogue, and certainly there will be dramatic tension—something to drive the story forward and keep the reader enthralled. Faulkner’s ( 2016b ) feminist ethnography, “Postkarten aus Deutschland,” is an example of how a qualitative researcher can use narrative poetry (see Figure 34.2 ). Faulkner wrote a chapbook of poems from participant observation in Mannheim, Germany, like postcards that tell the story of participant observation and the time spent observing and writing down details of living, working, and playing in Germany. Faulkner used scenes of participating as a student in a German class, traveling with her family, and everyday experiences like running, spending time with friends, and shopping to add interest and veracity to the project.

Excerpt from “Postkarten aus Deutschland: A Chapbook of Ethnographic Poetry” (Faulkner, 2016b ).

Poets can create dramatic tension both through the sequencing of details and through word choice, or what poets call diction . It is a mistake to suggest that the only type of poem that can work in service of the personal is the explicitly narrative one. Not all stories require chronology or sequence. Some are best expressed in glimpses of place or time, in vivid flashes of insight. Where a memoir or a long narrative poem will move us through story across place and time, a lyric poem can slow us down to find the story inside a single moment.

The term lyric probably makes you think about music, and this is exactly right. In antiquity, lyric poems were those that expressed personal emotions and feelings and were usually accompanied by music, often played on a stringed instrument called a lyre. They were typically written or originally spoken or sung in the first person.

As poetry has evolved away from song, however, that term lyric has come to refer not to music played alongside the poem, but instead to the music inside it, in the way the poet employs sound devices like alliteration, assonance , and repetition of various types to create the appropriate mood (see Figure 34.3 ).

Lyric poem.

This relationship poem begins with a direct address to a “new husband, old lover” and a recollection of a shared sensual experience, which puts the reader into an intensely intimate space. A first read may evoke feelings of companionship, trust, love, even bliss. The poem’s imagery seems beautiful and comforting—“breeze of butterscotch,” “sun-burnished afternoon,” “breakers of mahogany”—but a second, careful read will reveal something more. The “rolling four-poster” at once suggests sexual connection, but could also suggest instability or chaos. “Arms and ankles all slip-knot and braid” shows bodily closeness, certainly, but note the use of the word “knot” to point to something more complicated—a sense of being bound or trapped.

Further into the poem, we find language like “swaying,” “late,” “tempting,” “laggard,” and “augural,” which come together to form a mood of distinct unease. It is pretty clear this marriage is not going to last much beyond this “honeymoon kiss.”

The music of the poem can be found mainly in the repetition of long “a” sounds. They begin in the title with the word Bay and continue through bay/taste/lay/ankles/braid/breakers/swaying/cane/bracing/waving and return to bay in the final line. This effectively bookends the poem with sound. The strong repetition creates the effect of constraint within the lines and stanzas and also, by extension, within the context of the doomed relationship narrative suggested in the poem.

Faulkner and Squillante ( 2018 ) used an intersectional feminist approach to examine their responses to the 2016 U.S. presidential election and rape culture by creating a video collage composed of video, images, and poetry. Their womanifesta, “Nasty Women Join the Hive,” decentered White feminism through the use of reflexive poetry, repetitive images, and critical questions to invite other women to embrace intersectional feminism and reject White feminism and White fragility.

Experimental Forms