The String Theory

What happens when all of a man's intelligence and athleticism is focused on placing a fuzzy yellow ball where his opponent is not? An obsessive inquiry (with footnotes), into the physics and metaphysics of tennis.

When Michael T. Joyce of Los Angeles serves, when he tosses the ball and his face rises to track it, it looks like he's smiling, but he's not really smiling–his face's circumoral muscles are straining with the rest of his body to reach the ball at the top of the toss's rise. He wants to hit it fully extended and slightly out in front of him–he wants to be able to hit emphatically down on the ball, to generate enough pace to avoid an ambitious return from his opponent. Right now, it's 1:00, Saturday, July 22, 1995, on the Stadium Court of the Stade Jarry tennis complex in Montreal. It's the first of the qualifying rounds for the Canadian Open, one of the major stops on the ATP's "hard-court circuit," [1] which starts right after Wimbledon and climaxes at N.Y.C.'s U.S. Open. The tossed ball rises and seems for a second to hang, waiting, cooperating, as balls always seem to do for great players. The opponent, a Canadian college star named Dan Brakus, is a very good tennis player. Michael Joyce, on the other hand, is a world-class tennis player. In 1991, he was the top-ranked junior in the United States and a finalist at Junior Wimbledon [2] is now in his fourth year on the ATP Tour, and is as of this day the seventy-ninth-best tennis player on planet earth.

A tacit rhetorical assumption here is that you have very probably never heard of Michael Joyce of Brentwood, L.A. Nor of Tommy Ho of Florida. Nor of Vince Spadea nor Jonathan Stark nor Robbie Weiss nor Steve Bryan–all ranked in the world's top one hundred at one point in 1995. Nor of Jeff Tarango, sixty-eight in the world, unless you remember his unfortunate psychotic breakdown in full public view during last year's Wimbledon [3] .

You are invited to try to imagine what it would be like to be among the hundred best in the world at something. At anything. I have tried to imagine; it's hard.

Stade Jarry's Center Court, known as the Stadium Court, can hold slightly more than ten thousand souls. Right now, for Michael Joyce's qualifying match, there are ninety-three people in the crowd, ninety-one of whom appear to be friends and relatives of Dan Brakus's. Michael Joyce doesn't seem to notice whether there's a crowd or not. He has a way of staring intently at the air in front of his face between points. During points, he looks only at the ball.

The acoustics in the near-empty stadium are amazing–you can hear every breath, every sneaker's squeak, the authoritative pang of the ball against very tight strings.

Professional tennis tournaments, like professional sports teams, have distinctive traditional colors. Wimbledon's is green, the Volvo International's is light blue. The Canadian Open's is–emphatically–red. The tournament's "title sponsor," du Maurier cigarettes, has ads and logos all over the place in red and black. The Stadium Court is surrounded by a red tarp festooned with corporate names in black capital letters, and the tarp composes the base of a grandstand that is itself decked out in red-and-black bunting, so that from any kind of distance, the place looks like either a Kremlin funeral or a really elaborate brothel. The match's umpire and linesmen and ball boys all wear black shorts and red shirts emblazoned with the name of a Quebec clothier [4] .

.css-f6drgc:before{margin:-0.99rem auto 0 -1.33rem;left:50%;width:2.1875rem;border:0.3125rem solid #FF3A30;height:2.1875rem;content:'';display:block;position:absolute;border-radius:100%;} .css-1aglugu{font-family:Lausanne,Lausanne-fallback,Lausanne-roboto,Lausanne-local,Arial,sans-serif;font-size:1.625rem;line-height:1.2;margin:0rem;}@media(max-width: 48rem){.css-1aglugu{font-size:1.75rem;line-height:1.2;}}@media(min-width: 64rem){.css-1aglugu{font-size:2.375rem;line-height:1.2;}}.css-1aglugu b,.css-1aglugu strong{font-family:inherit;font-weight:bold;}.css-1aglugu em,.css-1aglugu i{font-style:italic;font-family:inherit;}.css-1aglugu:before{content:'"';display:block;padding:0.3125rem 0.875rem 0 0;font-size:3.5rem;line-height:0.8;font-style:italic;font-family:Lausanne,Lausanne-fallback,Lausanne-styleitalic-roboto,Lausanne-styleitalic-local,Arial,sans-serif;} You can hear every breath, every sneaker's squeak, the authoritative pang of the ball against very tight strings.

Stade Jarry's Stadium Court is adjoined on the north by Court One, or the Grandstand Court, a slightly smaller venue with seats on only one side and a capacity of forty-eight hundred. A five-story scoreboard lies just west of the Grandstand, and by late afternoon both courts are rectangularly shadowed. There are also eight nonstadium courts in canvas-fenced enclosures scattered across the grounds. There are very few paying customers on the grounds on Saturday, but there are close to a hundred world-class players: big spidery French guys with gelled hair, American kids with peeling noses and Pac-10 sweats, lugubrious Germans, bored-looking Italians. There are blank-eyed Swedes and pockmarked Colombians and cyberpunkish Brits. Malevolent Slavs with scary haircuts. Mexican players who spend their spare time playing two-on-two soccer in the gravel outside the players' tent. With few exceptions, all the players have similar builds–big muscular legs, shallow chests, skinny necks, and one normal-size arm and one monstrously huge and hypertrophic arm. Many of these players in the qualies, or qualifying rounds, have girlfriends in tow, sloppily beautiful European girls with sandals and patched jeans and leather backpacks, girlfriends who set up cloth lawn courts [5] . At the Radisson des Gouverneurs, the players tend to congregate in the lobby, where there's a drawsheet for the qualifying tournament up on a cork bulletin board and a multilingual tournament official behind a long desk, and the players stand around in the air-conditioning in wet hair and sandals and employ about forty languages and wait for results of matches to go up on the board and for their own next matches' schedules to get posted. Some of them listen to headphones; none seem to read. They all have the unhappy and self-enclosed look of people who spend huge amounts of time on planes and in hotel lobbies, waiting around–the look of people who must create an envelope of privacy around themselves with just their expressions. A lot of players seem extremely young–new guys trying to break into the tour–or conspicuously older–like over thirty–with tans that look permanent and faces lined from years in the trenches of tennis's minor leagues.

The Canadian open, one of the ATP tour's "Super 9" tournaments, which weigh most heavily in the calculations of world ranking, officially starts on Monday, July 24. What's going on for the two days right before it is the qualies. This is essentially a competition to determine who will occupy the seven slots in the Canadian Open's main draw designated or "qualifiers." A qualifying tourney precedes just about every big-money ATP event, and money and prestige and lucrative careers are often at stake in qualie matches, and often they feature the best matches of the whole tournament, and it's a good bet you've never heard of qualies.

The realities of the men's professional-tennis tour bear about as much resemblance to the lush finals you see on TV as a slaughterhouse does to a well-presented cut of restaurant sirloin. For every Sampras-Agassi final we watch, there's been a weeklong tournament, a pyramidical single-elimination battle between 32, 64, or 128 players, of whom the finalists are the last men standing. But a player has to be eligible to enter that tournament in the first place. Eligibility is determined by ATP computer ranking. Each tournament has a cutoff, a minimum ranking required to be entered automatically in the main draw. Players below that ranking who want to get in have to compete in a kind of pretournament tournament. That's the easiest way to describe qualies. I'll try to describe the logistics of the Canadian Open's qualies in just enough detail to communicate the complexity without boring you mindless.

The du Maurier Omnium Ltée has a draw of sixty-four. The sixteen entrants with the highest ATP rankings get "seeded," which means their names are strategically dispersed in the draw so that, barring upsets, they won't have to meet one another until the latter rounds. Of the seeds, the top eight–here, Andre Agassi, Pete Sampras, Michael Change, the Russian Yevgeny Kafelnikov, Croatia's Goran Ivanisevic, South Africa's Wayne Ferreira, Germany's Michael Stich, and Switzerland's Marc Rosset, respectively–get "byes," or automatic passes, into the tournament's second round. This means that there is actually room for fifty-six players in the main draw. The cutoff for the 1995 Canadian Open isn't fifty-six, however, because not all of the top fifty-six players in the world are here [6] . Here, the cutoff is eighty-five. You'd think that this would mean that anybody with an ATP ranking of eighty-six or lower would have to play the qualies, but here, too, there are exceptions. The du Maurier Omnium Ltée, like most other big tournaments, has five "wild card" entries into the main draw. These are special places given either to high-ranked players who entered after the six-week deadline but are desirable to have in the tournament because they're big stars (like Ivanisevic, number six in the world but a notorious flakeroo who supposedly "forgot to enter till a week ago") or to players who ranked lower than eighty-fifth whom the tournament wants because they are judged "uniquely deserving."

By the way, if you're interested, the ATP tour updates and publishes its world ranking weekly, and the rankings constitute a nomological orgy that makes for truly first-rate bathroom reading. As of this writing, Mahesh Bhudapathi is 284th, Luis Lobo 411th. There's Martin Sinner and Guy Forget. There's Adolf Musil and Jonathan Venison and Javier Frana and Leander Paes. There's–no kidding–Cyril Suk. Rodolfo Ramos-Paganini is 337th, Alex Lopez-Moron is 174th. Gilad Bloom is 228th and Zoltan Nagy is 414th. Names out of some postmodern Dickens: Udo Riglewski and Louis Gloria and Francisco Roig and Alexander Mronz. The twenty-ninth-best player in the world is named Slava Dosedel. There's Claude N'Goran and Han-Cheol Shin (276th but falling fast) and Horacio de la Peña and Marcus Barbosa and Amos Mansdorf and Mariano Hood. Andres Zingman is currently ranked two places above Sander Groen. Horst Skoff and Kris Goossens and Thomas Hogstedt are all ranked higher than Martin Zumpft. One reason the industry sort of hates upsets is that the ATP press liaisons have to go around teaching journalists how to spell and pronounce new names.

The Canadian qualies themselves have a draw of fifty-six world-class players; the cutoff for qualifying for the qualies is an ATP ranking of 350th [7] . The qualies won't go all the way through to the finals, only to the quarterfinals: The seven quarterfinalists of the qualies will receive first-round slots in the Canadian Open [8] . This means that a player in the qualies will need to win three rounds–round of fifty-six, round of twenty-eight, round of fourteen–in two days to get into the first round of the main draw [9] .

The eight seeds in the qualies are the eight players whom the Canadian Open officials consider most likely to make the quarters and thus get into the main draw. The top seed this weekend is Richard Krajicek [10] a six-foot-five-inch Dutchman who wears a tiny white billed hat in the sun and rushes the net like it owes him money and in general plays like a rabid crane. Both his knees are bandaged. He's in the top twenty and hasn't had to play qualies for years, but for this tournament he missed the entry deadline, found all the wild cards already given to uniquely deserving Canadians, and with phlegmatic Low Country cheer decided to go ahead and play the weekend qualies for the match practice. The qualies' eight seed is Jamie Morgan, an Australian journeyman, around one hundredth in the world, whom Michael Joyce beat in straight sets last week in the second round of the main draw at the Legg Mason Tennis Classic in Washington, D.C. Michael Joyce is seeded third.

If you're wondering why Joyce, who's ranked above the number-eighty-five cutoff, is having to play the Canadian Open qualies, gird yourself for one more smidgen of complication. The fact is that six weeks before, Joyce's ranking was not above the cutoff, and that's when the Canadian entry deadline was, and that's the ranking the tournament used when it made up the main draw. Joyce's ranking jumped from 119th to 89th after Wimbledon 1995, where he beat Marc Rosset (ranked 11th in the world) and reached the round of sixteen.

The qualie circuit is to professional tennis sort of what AAA baseball is to the major leagues: Somebody playing the qualies in Montreal is an undeniably world-class tennis player, but he's not quite at the level where the serious TV and money are. In the main draw of the du Maurier Omnium Ltée, a first-round loser will earn $5,400, and a second-round loser $10,300. In the Montreal qualies, a player will receive $560 for losing in the second round and an even $0.00 for losing in the first. This might not be so bad if a lot of the entrants for the qualies hadn't flown thousands of miles to get here. Plus, there's the matter of supporting themselves in Montreal. The tournament pays the hotel and meal expenses of players in the main draw but not of those in the qualies. The seven survivors of the qualies, however, will get their hotel expenses retroactively picked up by the tournament. So there's rather a lot at stake–some of the players in the qualies are literally playing for their supper or for the money to make airfare home or to the site of the next qualie.

You could think of Michael Joyce's career as now kind of on the cusp between the majors and AAA ball. He still has to qualify for some tournaments, but more and more often he gets straight into the main draw. The move from qualifier to main-draw player is a huge boost, both financially and psychically, but it's still a couple of plateaus away from true fame and fortune. The main draw's 64 or 128 players are still mostly the supporting cast for the stars we see in televised finals. But they are also the pool from which superstars are drawn. McEnroe, Sampras, and even Agassi had to play qualies at the start of their careers, and Sampras spent a couple of years losing in the early rounds of main draws before he suddenly erupted in the early nineties and started beating everybody.

Still, even most main-draw players are obscure and unknown. An example is Jakob Hlasek [11] a Czech who is working out with Marc Rosset on one of the practice courts this morning when I first arrive at Stade Jarry. I notice them and go over to watch only because Hlasek and Rosset are so beautiful to see–at this point, I have no idea who they are. They are practicing ground strokes down the line–Rosset's forehand and Hlasek's backhand–each ball plumb-line straight and within centimeters of the corner, the players moving with compact nonchalance I've since come to recognize in pros when they're working out: The suggestion is of a very powerful engine in low gear. Jakob Hlasek is six foot two and built like a halfback, his blond hair in a short square Eastern European cut, with icy eyes and cheekbones out to here: He looks like either a Nazi male model or a lifeguard in hell and seems in general just way too scary ever to try to talk to. His backhand is a one-hander, rather like Ivan Lendl's, and watching him practice it is like watching a great artist casually sketch something. I keep having to remember to blink. There are a million little ways you can tell that somebody's a great player–details in his posture, in the way he bounces the ball with his racket head to pick it up, in the way he twirls the racket casually while waiting for the ball. Hlasek wears a plain gray T-shirt and some kind of very white European shoes. It's midmorning and already at least 90 degrees, and he isn't sweating. Hlasek turned pro in 1983, six years later had one year in the top ten, and for the last few years has been ranked in the sixties and seventies, getting straight into the main draw of all the tournaments and usually losing in the first couple of rounds. Watching Hlasek practice is probably the first time it really strikes me how good these professionals are, because even just fucking around Hlasek is the most impressive tennis player I've ever seen [12] . I'd be surprised if anybody reading this article has ever heard of Jakob Hlasek. By the distorted standards of TV's obsession with Grand Slam finals and the world's top five, Hlasek is merely an also-ran. But last year, he made $300,000 on the tour (that's just in prize money, not counting exhibitions and endorsement contracts), and his career winnings are more than $4 million, and it turns out his home base was for a time Monte Carlo, where lots of European players with tax issues end up living.

Michael Joyce, twenty-two, is listed in the ATP Tour Player Guide as five eleven and 165 pounds, but in person he's more like five nine. On the Stadium Court, he looks compact and stocky. The quickest way to describe him would be to say that he looks like a young and slightly buff David Caruso. He is fair-skinned and has reddish hair and the kind of patchy, vaguely pubic goatee of somebody isn't quite old enough yet to grow real facial hair. When he plays in the heat, he wears a hat ]13] . He wears Fila clothes and uses Yonex rackets and is paid to do so. His face is childishly full, and though it isn't freckled, it somehow looks like it ought to be freckled. A lot of professional tennis players look like lifeguards–with that kind of extreme tan that looks like it's penetrated to the subdermal layer and will be retained to the grave–but Joyce's fair skin doesn't tan or even burn, though he does get red in the face when he plays, from effort [14] . His on-court expression is grim without being unpleasant; it communicates the sense that Joyce's attentions on-court have become very narrow and focused and intense–it's the same pleasantly grim expression you see on, say, working surgeons or jewelers. On the Stadium Court, Joyce seems boyish and extremely adult at the same time. And in contrast to his Canadian opponent, who has the varnished good looks and Pepsodent smile of the stereotypical tennis player, Joyce looks terribly real out there playing: He sweats through his shirt [15] gets flushed, whoops for breath after a long point. He wears little elastic braces on both ankles, but it turns out they're mostly prophylactic.

It's 1:30 p.m. Joyce has broken Brakus's serve once and is up 3-1 in the first set and is receiving. Brakus is in the multi-brand clothes of somebody without an endorsement contract. He's well over six feet tall, and, as with many large male college stars, his game is built around his serve [16] . With the score at 0-15, his first serve is flat and 118 miles per hour and way out of Joyce's backhand, which is a two-hander and hard to lunge effectively with, but Joyce lunges plenty effectively and sends the ball back down the line to the Canadian's forehand, deep in the court and with such flat pace that Brakus has to stutter-step a little and backpedal to get set up–clearly, he's used to playing guys for whom 118 mumps out wide would be an outright ace or at least produce such a weak return that he could move up easily and put the ball away–and Brakus now sends the ball back up the line, high over the net, loopy with topspin–not all that bad a shot, considering the fierceness of the return, and a topspin shot that'd back most of the tennis players up and put them on the defensive, but Michael Joyce, whose level of tennis is such that he moves in on balls hit with topspin and hits them on the rise [17] moves in and takes the ball on the rise and hits a backhand cross so tightly angled that nobody alive could get to it. This is kind of a typical Joyce-Brakus point. The match is carnage of a particularly high-level sort: It's like watching an extremely large and powerful predator get torn to pieces by an even larger and more powerful predator. Brakus looks pissed off after Joyce's winner and makes some berating-himself-type noises, but the anger seems kind of pro forma–it's not like there's anything Brakus could have done much better, not given what he and the seventy-ninth-best player in the world have in their respective arsenals.

Michael Joyce will later say that Brakus "had a big serve, but the guy didn't belong on a pro court." Joyce didn't mean this in an unkind way. Nor did he mean it in a kind way. It turns out what Michael Joyce says rarely has any kind of spin or slant on it; he mostly just reports what he sees, rather like a camera. You couldn't even call him sincere, because it's not like it seems ever to occur to him to try to be sincere or nonsincere. For a while, I thought that Joyce's rather bland candor was a function of his not being very bright. This judgment was partly informed by the fact that Joyce didn't go to college and was only marginally involved in his high school academics (stuff I know because he told me right away) [18] . What I discovered as the tournament wore on was that I can be kind of a snob and an asshole and that Michael Joyce's affectless openness is not a sign of stupidity but of something else.

Advances in racket technology and conditioning methods over the last decade have dramatically altered men's professional tennis. For much of the twentieth century, there were two basic styles of top-level tennis. The "offensive" [19] style is based on the serve and the net game and is ideally suited to slick, or "fast," surfaces like grass and cement. The "defensive," or "baseline," style is built around foot speed, consistency, and ground strokes accurate enough to hit effective passing shots against a serve-and-volleyer; this style is most effective on "slow" surfaces like clay and Har-True composite. John McEnroe and Bjorn Borg are probably the modern era's greatest exponents of the offensive and defensive styles, respectively.

There is now a third way to play, and it tends to be called the "power baseline" style. As far as I can determine, Jimmy Connors [20] more or less invented the power-baseline game back in the seventies, and in the eighties Ivan Lendl raised it to a kind of brutal art. In the nineties, the majority of players on the ATP Tour have a power-baseline-type game. This game's cornerstone is ground strokes, but ground strokes hit with incredible pace, such that winners from the baseline are not unusual [21] . A power-baseliner's net game tends to be solid but uninspired -- a PBer is more apt to hit a winner on the approach shot and not need to volley at all. His serve is usually competent and reasonably forceful, but the really inspired part of a PBer's game is usually his return of the serve [22] . He often has incredible reflexes and can hit the power and aggression of an offensive style and the speed and calculated patience of a defensive style. It is adjustable both to slick grass and to slow clay, but its most congenial surface is DecoTurf II [23] the type of abrasive hard-court surface now used at the U.S. Open and at all the broiling North American tune-ups for it, including the Canadian Open.

There is now a third way to play, and it tends to be called the "power baseline" style.

Boris Becker and Stefan Edberg are contemporary examples of the classic offensive style. Serve-and-volleyers are often tall [24] and tall Americans like Pete Sampras and Todd Martin and David Wheaton are also offensive players. Michael Chang is a pure exponent of the defensive tour's Western Europeans and South Americans, many of whom grew up exclusively on clay and now stick primarily to the overseas clay-court circuits. Americans Jimmy Arias, Aaron Krickstein, and Jim Courier all play a power-baseline game. So does just about every new young male player on the tour. But its most famous and effective post Lendl avatar is Andre Agassi, who on 1995's hard-court circuit was simply kicking everyone's ass [25] .

Michael Joyce's style is power baseline in the Agassi mold: Joyce is short and right-handed and has a two-handed backhand, a serve that's just good enough to set up a baseline attack, and a great return of serve that is the linchpin of his game. Like Agassi, Joyce takes the ball early, on the rise, so he always looks like he's moving forward in the court even though he rarely comes to the net. Joyce's first serve usually comes in around ninety-five miles per hour [26] and his second serve is in the low eighties but has so much spin on it that the ball turns topological shapes in the air and bounces high and wide to the first-round Canadian's backhand. Brakus has to stretch to float a slice return, the sort of weak return that a serve-and-volleyer would be rushing up to the net to put away on the fly. Joyce does move up, but only halfway, right around his own service line, where he lets the floater land and bounce up all ripe, and he winds up his forehand and hits a winner crosscourt into the deuce corner, very flat and hard, so that the ball makes an emphatic sound as it hits the scarlet tarp behind Brakus's side of the court. Ball boys move for the ball and reconfigure complexly as Joyce walks back to serve another point. The applause of a tiny crowd is so small and sad and tattered-sounding that it'd almost be better if people didn't clap at all.

Like those of Lendl and Agassi and Courier and many PBers, Joyce's strongest shot is his forehand, a weapon of near-Wagnerian aggression and power. Joyce's forehand is particularly lovely to watch. It's sparer and more textbook than Lendl's whip-crack forehand or Borg's great swooping loop; by way of decoration, there's only a small loop of flourish [27] on the backswing. The stroke itself is completely well out in front of him. As with all great players, Joyce's side is so emphatically to the net as the ball approaches that his posture is a classic contrapposto.

As Joyce on the forehand makes contact with the tennis ball, his left hand behind him opens up, as if he were releasing something, a decorative gesture that has nothing to do with the mechanics of the stroke. Michael Joyce doesn't know that his left hand opens up at impact on forehands: It is unconscious, some aesthetic tic that stated when he was a child and is now inextricably hardwired into a stroke that is itself, now, unconscious for Joyce, after years of his hitting more forehands over and over and over than anyone could ever count [28] .

Agassi, who is twenty-five, is kind of Michael Joyce's hero. Just the week before this match, at the Legg Mason Tennis Classic in Washington, in wet-mitten heat that had players vomiting on-court and defaulting all over the place, Agassi beat Joyce in the third round of the main draw, 6-2, 6-2. Every once in a while now, Joyce will look over at his coach next to me in the player-guest section of the Grandstand and grin and say something like, "Agassi'd have killed me on that shot." Joyce's coach will adjust the set of his sunglasses and not say anything–coaches are forbidden to say anything to their players during a match. Joyce's coach, Sam Aparicio [29] a protégé of Pancho Gonzalez's, is based in Las Vegas, which is also Agassi's hometown, and Joyce has several times been flown to Las Vegas at Agassi's request to practice with him and is apparently regarded by Agassi as a friend and peer–these are facts Michael Joyce will mention with as much pride as he evinces in speaking of victories and world ranking.

There are differences between Agassi's and Joyce's games, however. Though Joyce and Agassi both use the western forehand grip and two-handed backhand that are very distinctive of topspinners, Joyce's ground strokes are very flat–i.e., spinless, passing low over the net, driven rather than brushed–because the actual motion of his strokes is so levelly horizontal. Joyce's balls actually look more like Jimmy Connors's balls than like Agassi's [30] . Some of Joyce's ground strokes look like knuckleballs going over the net, and you can actually see the ball's seams just hanging there, not spinning. Joyce also has a slight hitch in his backhand that makes it look stiff and slightly awkward, though his pace and placement are lethal; Agassi's own backhand is flowing and hitchless [31] . And while Joyce is far from slow, he lacks Agassi's otherwordly foot speed. Agassi is every bit as fast as Michael Chang [32] . Watch him on TV sometime as he's walking between points: He takes the tiny, violently pigeon-toed steps of a man whose feet weigh basically nothing.

Michael Joyce also–in his own coach's opinion–doesn't "see" the ball in the same magical way that Andre Agassi does, and so Joyce can't take the ball quite so early or generate quite the same amount of pace off his ground strokes. The business of "seeing" is important enough to explain. Except for the serve, power in tennis is not a matter of strength but of timing. This is one reason why so few top tennis players look muscular [33] . Any normal adult male can hit a tennis ball with a pro pace; the trick is being able to hit the ball both hard and accurately. If you can get your body in just the right position and time your stroke so you hit the ball in just the right spot–waist-level, just slightly out in front of you, with your own weight moving from your back leg to your front leg as you make contact–you can both cream the ball and direct it. Since "… just the right …" is a matter of millimeters and microseconds, a certain kind of vision is crucial [34] . Agassi's vision is literally one in a billion, and it allows him to hit his ground strokes as hard as he can just about every time. Joyce, whose hand-eye coordination is superlative, in the top 1 percent of all athletes everywhere (he's been exhaustively tested), still has to take some incremental bit of steam off most of his ground strokes if he wants to direct them.

I submit that tennis is the most beautiful sport there is [35] and also the most demanding. It requires body control, hand-eye coordination, quickness, flat-out speed, endurance, and that weird mix of caution and abandon we call courage. It also requires smarts. Just one single shot in one exchange in one point of a high-level match is a nightmare of mechanical variables. Given a net that's three feet high (at the center) and two players in (unrealistically) fixed positions, the efficacy of one single shot is determined by its angle, depth, pace, and spin. And each of these determinants is itself determined by still other variables–i.e., a shot's depth is determined by the height at which the ball passes over the net combined with some integrated function of pace and spin, with the ball's height over the net itself determined by the player's body position, grip on the racket, height of backswing and angle of racket face, as well as the 3-D coordinates through which the racket face moves during that interval in which the ball is actually on the strings. The tree of variables and determinants branches out and out, on and on, and then on much further when the opponent's own position and predilections and the ballistic features of the ball he's sent you to hit are factored in [36] . No silicon-based RAM yet existent could compute the expansion of variables for even a single exchange; smoke would come out of the mainframe. The sort of thinking involved is the sort that can be done only by a living and highly conscious entity, and then it can really be done only unconsciously, i.e., by fusing talent with repetition to such an extent that the variables are combined and controlled without conscious thought. In other words, serious tennis is a kind of art.

I submit that tennis is the most beautiful sport there is and also the most demanding.

If you've played tennis at least a little, you probably have some idea how hard a game is to play really well. I submit to you that you really have no idea at all. I know I didn't. And television doesn't really allow you to appreciate what real top-level players can do–how hard they're actually hitting the ball, and with what control and tactical imagination and artistry. I got to watch Michael Joyce practice several times right up close, like six feet and a chain-link fence away. This is a man who, at full run, can hit a fast-moving tennis ball into a one-foot square area seventy-eight feet away over a net, hard. He can do this something like more than 90 percent of the time. And this is the world's seventy-ninth-best player, one who has to play the Montreal qualies.

It's not just the athletic artistry that compels interest in tennis at the professional level. It's also what this level requires–what it's taken for the one-hundredth-ranked player in the world to get there, what it takes to stay, what it would take to rise even higher against other men who've paid the same price number one hundred has paid.

Americans revere athletic excellence, competitive success, and it's more than lip service we pay; we vote with our wallets. We'll pay large sums to watch a truly great athlete; we'll reward him with celebrity and adulation and will even go so far as to buy products and services he endorses.

But it's better for us not to know the kinds of sacrifices the professional-grade athlete has made to get so very good at one particular thing. Oh, we'll invoke lush clichés about the lonely heroism of Olympic athletes, the pain and analgesia of football, the early rising and hours of practice and restricted diets, the preflight celibacy, et cetera. But the actual facts of the sacrifices repel us when we see them: basketball geniuses who cannot read, sprinters who dope themselves, defensive tackles who shoot up with bovine hormones until they collapse or explode. We prefer not to consider closely the shockingly vapid and primitive comments uttered by athletes in postcontest interviews or to consider what impoverishments in one's mental life would allow people actually to think the way great athletes seem to think. Note the way "up close and personal" profiles of professional athletes strain so hard to find evidence of a rounded human life–outside interests and activities, values beyond the sport. We ignore what's obvious, that most of this straining is farce. It's farce because the realities of top-level athletics today require an early and total commitment to one area of excellence. An ascetic focus [37] . A subsumption of almost all other features of human life to one chosen talent and pursuit. A consent to live in a world that, like a child's world, is very small.

We prefer not to consider closely the shockingly vapid and primitive comments uttered by athletes

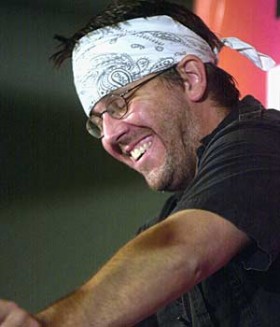

Playing two professional singles matches on the same day is almost unheard of, except in qualies. Michael Joyce's second qualifying round is at 7:30 on Saturday night. He's playing an Austrian named Julian Knowle, a tall and cadaverous guy with pointy Kafkan ears. Knowle uses two hands off both sides, [38] and throws his racket when he's mad. The match takes place on Stade Jarry's Grandstand Court. The smaller Grandstand is more intimate: The box seats start just a few yards from the courts surface, and you're close enough to see a wen on Joyce's cheek or the abacus of sweat on Herr Knowle's forehead. The Grandstand could hold maybe forty-eight hundred people, and tonight there are exactly four human beings in the audience as Michael Joyce basically beats the ever-living shit out of Julian Knowle, who will be at the Montreal airport tonight at 1:30 to board a red-eye for a minor-league clay tournament in Poznan, Poland.

During this afternoon's match, Joyce wore a white Fila shirt with different-colored sleeves. Onto his sleeve is sewn a patch that says POWERBAR; Joyce is paid $1,000 each time he appears in the media wearing his patch. For tonight's match, Joyce wears a pinstripe Jim Courier-model Fila shirt with one red sleeve and one blue sleeve. He has a red bandanna around his head, and as he begins to perspire in the humidity, his face turns the same color as the bandanna. It is hard not to find this endearing. Julian Knowle has on an abstract pastel shirt whose brand is unrecognizable. He has very tall hair, Knowle does, that towers over his head at near-Beavis altitude and doesn't diminish or lose its gelled integrity as he perspires [39] . Knowle's shirt, too, has sleeves of different colors. This seems to be the fashion constant this year among the qualifiers: sleeve-color asymmetry.

The Joyce-Knowle match takes only slightly more than an hour. This is including delays caused when Knowle throws his racket and has to go retrieve it or when Knowle walks around in aimless circles, muttering blackly to himself in some High German dialect. Knowle's tantrums seem a little contrived and insincere to me, though, because he rarely loses a point as a result of doing anything particularly wrong. Here's a typical point in this match: It's 1-4 and 15-30 in the sixth game. Knowle hits a respectable 110-mile-an-hour slice serve to Joyce's forehand. Joyce returns a very flat, penetrating drive crosscourt so that Knowle has to stretch and hit his forehand on the run, something that's not particularly easy to do with a two-handed forehand. Knowle gets to the forehand and hits a thoroughly respectable shot, heavy with topspin and landing maybe only a little bit short, a few feet behind the service line, whereupon he reverses direction and starts scrambling back to get in the middle of the baseline to get ready for his next shot. Joyce, as is SOP, has moved in on the slightly short ball and takes it on the rise just after it's bounced, driving a backhand even flatter and harder in the exact same place he hit his last shot, the spot Knowle is scrambling away from. Knowle is now forced to reverse direction and get back to where he was. This he does, and he gets his racket on the ball, but only barely, sending back a weak little USDA Prime loblet that Joyce, now in the vicinity of the net, has little trouble blocking into the open court for a winner. The four people clap, Knowle's racket goes spinning into the blood-colored tarp, and Joyce walks expressionlessly back to the deuce court to receive again whenever Knowle gets around to serving. Knowle has slightly more firepower than the first round's Brakus: His ground strokes are formidable, probably even lethal if he has sufficient time to get to the ball and get set up. Joyce simply denies him that time. Joyce will later admit that he wasn't working all that hard in this match, and he doesn't need to. He hits few spectacular winners, but he also makes very few unforced errors, and his shots are designed to make the somewhat clumsy Knowle move a lot and to deny him the time and the peace ever to set up his game. This strategy is one that Knowle cannot solve or interdict: he has the firepower but not the speed to do so. This may be one reason why Joyce is unaffronted by having to play the qualies for Montreal. Barring some kind of major injury or neurological seizure, he's not going to lose to somebody like Austria's Julian Knowle–Joyce is simply on a different plane than the mass of these qualie players.

The idea that there can be wholly distinct levels to competitive tennis–levels so distinct that what's being played is in essence a whole different game–might seem to you weird and hyperbolic. I have played probably just enough tennis to understand that it's true. I have played against men who were on a whole different, higher plateau than I, and I have understood on the deepest and most humbling level the impossibility of beating them, of "solving their game." Knowle is technically entitled to be called a professional, but he is playing a fundamentally different grade of tennis from Michael Joyce's, one constrained by limitations Joyce does not have. I feel like I could get on a tennis court with Julian Knowle. He would beat me, perhaps handily, but I don't feel like it would be absurd for me to occupy the same seventy-eight-by-twenty-seventy-foot rectangle as he. The idea of me playing Joyce–or even hitting around with him, which was one of the ideas I was entertaining on the flight to Montreal–is now revealed to me to be in a certain way obscene, and I resolve not even to let Joyce [40] know that I used to play competitive tennis, and (I'd presumed) rather well. This makes me sad.

This article is about Michael Joyce and the realities of the tour, not me. But since a big part of my experience of the Canadian Open and its players was one of sadness, it might be worthwhile to spend a little time letting you know where I'm coming from vis-à-vis these players. As a young person, I played competitive junior tennis, traveling to tournaments all over the Midwest, the region that the United States Tennis Association has in its East Coast wisdom designated to the "western" region. Most of my best friends were also tennis players, and on a regional level we were successful, and we thought of ourselves as extremely good players. Tennis and our proficiency at it were tremendously important to us–a serious junior gives up a lot of his time and freedom to develop his game [41] and it can very easily come to constitute a big part of his identity and self-worth. The other fourteen-year-old Midwest hotshots and I knew that our fishpond was somehow limited; we knew that there was a national level of play and that there were hotshots and champions at that level. But levels and plateaus beyond our own seemed abstract, somehow unreal –those of us who were the best in our region literally could not imagine players our own age who were substantially better than we.

A child's world tends to be very small. If I'd been just a little bit better, an actual regional champion, I would have gotten to see that there were fourteen-year-olds in the United States playing a level of tennis unlike anything I knew about. My own game as a junior was a particular type of the classic defensive style, a strategy Martin Amis once described as "craven retrieval." I didn't hit the ball all that hard, but I rarely made unforced errors, and I was fast, and my general approach was simply to keep hitting the ball back to my opponent until my opponent fucked up and either made an unforced error or hit a ball so short and juicy that even I could hit a winner off it. It doesn't look like a very glorious or even interesting way to play, now that I see it here in bald retrospective print, but it was interesting to me, and you'd be surprised how effective it was (on the level at which I was competing, at least). At age twelve, a good competitive player will still generally miss after four or five balls (mostly because he'll get impatient or grandiose). At age sixteen, a good player will generally keep the ball in play for more like seven or eight shots before he misses. At the collegiate level, too, opponents were stronger than junior players but not markedly more consistent, and if I could keep a rally going to seven or eight shots, I could usually win the point on the other guy's mistake [42] . I still play–not competitively, but seriously–and I should confess that deep down inside, I still consider myself an extremely good tennis player, very hard to beat. Before coming to Montreal to watch Michael Joyce, I'd seen professional tennis only on television, which, as has been noted, does not give the viewer a very accurate picture of how good pros are. I thus further confess that I arrived in Montreal with some dim unconscious expectation that these professionals–at least the obscure ones, the nonstars–wouldn't be all that much better than I. I don't mean to imply that I'm insane: I was ready to concede that age, a nasty ankle injury in 1988, and a penchant for nicotine (and worse) meant that I wouldn't be able to compete physically with a young unhurt professional, but on TV (while eating junk and smoking), I'd seen pros whacking balls at each other that didn't look to be moving substantially faster than the balls I'd hit. In other words, I arrived at my first professional tournament with the pathetic deluded pride that attends ignorance. And I have been brought up sharply. I do not play and never have played even the same game as these qualifiers.

The craven game I'd spent so much of my youth perfecting would not work against these guys. For one thing, pros simply do not make unforced errors–or, at any rate, they make them so rarely that there's no way they are going to make the four unforced errors in seven points necessary for me to win a game. Another thing, they will take any ball that doesn't have simply ferocious depth and pace on it and–given even a fractional moment to line up a shot–hit a winner off it. For yet another thing, their own shots have such ferocious depth and pace that there's no way I'd be able to hit more than a couple of them back at any one time. I could not meaningfully exist on the same court with these obscure, hungry players. Nor could you. And it's not just a matter of talent or practice. There's something else.

Once the main draw starts, you get to look up close and live at name tennis players you're used to seeing only as arras of pixels. One of the highlights of Tuesday's second round of the main draw is getting to watch Agassi play MaliVai Washington. Washington, the most successful U.S. black man on the tour since Arthur Ashe, is unseeded at the Canadian Open but has been ranked as high as number eleven in the world and is dangerous, and since I loathe Agassi with a passion, it's an exciting match. Agassi looks scrawny and faggy and, with his shaved skull and beret-ish hat and black shoes and socks and patchy goatee, like somebody just released from reform school (a look you can tell he's carefully decided on with the help of various paid image consultants). Washington, who's in dark-green shorts and a shirt with dark-green sleeves, was a couple of years ago voted by People magazine on of the Fifty Prettiest Human Beings or something, and on TV is real pretty but in person is awesome. From twenty yards away, he looks less like a human being than like a Michelangelo anatomy sketch: his upper body the V of serious weight lifting, his leg muscles standing out even in repose, his biceps little cannonballs of fierce-looking veins. He's beautiful and doomed, because the slowness of the Stadium Court makes it impractical for anybody but a world-class net man to rush the net against Agassi, and Washington is not a net man but a power-baseliner. He stays back and trades ground strokes with Agassi, and even though the first set goes to a tiebreaker, you can tell it's a mismatch. Agassi has less mass and flat-out speed than Washington, but he has timing and vision that give his ground strokes way more pace. He can stay back and hit nuclear ground strokes and force Washington until Washington eventually makes a fatal error. There are two ways to make an error against Agassi: The first is the standard way, hitting it out or into the net; the second is to hit anything shorter than a couple of feet inside the baseline, because anything that Agassi can move up on, he can hit for a winner. Agassi's facial expression is the slightly smug self-aware one of somebody who's used to being looked at and who automatically assumes the minute he shows up anywhere that everybody's looking at him. He's incredible to see play in person, but his domination of Washington doesn't make me like him any better; it's more like it chills me, as if I'm watching the devil play.

Television tends to level everybody out and make everyone seem kind of blandly good-looking, but at Montreal it turns out that a lot of the pros and stars are interesting-or even downright funny-looking. Jim Courier, former number one but now waning and seeded tenth here [43] , looks like Howdy Doody in a hat on TV but here turns out to be a very big boy–the "Guide Média" lists him at 175 pounds, but he's way more than that, with big smooth muscles and the gait and expression of a Mafia enforcer. Michael Chang, twenty-three and number five in the world, sort of looks like two different people stitched crudely together: a normal upper body perched atop hugely muscular and totally hairless legs. He has a mushroom-shaped head, inky-black hair, and an expression of deep and intractable unhappiness, as unhappy a face as I've seen outside a graduate creative-writing program [44] . Pete Sampras is mostly teeth and eyebrows in person and has unbelievably hairy legs and forearms–hair in the sort of abundance that allows me confidently to bet that he has hair on his back and is thus at least not 100 percent blessed and graced by the universe. Goran Ivanisevic is large and tan and surprisingly good-looking, at least for a Croat; I always imagine Croats looking ravaged and emaciated, like somebody out of a Munch lithograph–except for an incongruous and wholly absurd bowl haircut that makes him look like somebody in a Beatles tribute band. It's Ivanisevic who will beat Joyce in three sets in the main draw's second round. Czech former top-ten Petr Korda is another classic-looking mismatch: At six three and 160, he has the body of an upright greyhound and the face of–eerily, uncannily–a freshly hatched chicken (plus soulless eyes that reflect no light and seem to see only in the way that fishes' and birds' eyes see).

Television tends to level everybody out and make everyone seem kind of blandly good-looking, but at Montreal it turns out that a lot of the pros and stars are interesting-or even downright funny-looking.

And Wilander is here–Mats Wilander, Borg's heir and top-ten at eighteen, number one at twenty-four, now thirty and basically unranked and trying to come back after years off the tour, here cast in the role of the wily mariner, winning on smarts. Tuesday's best big-name match is between Wilander and Stefan Edberg, twenty-eight and Wilander's own heir [45] and now married to Annette Olsen, Wilander's SO during his glory days, which adds a delicious personal cast to the match, which Wilander wins 6-4 in the third. Wilander ends up getting all the way to the semifinals before Agassi beats him as badly as I have ever seen one professional beat another professional, the score being 6-2, 6-0, and the match not nearly as close as the score would indicate.

Even more illuminating than watching pro tennis live is watching it with Sam Aparicio. Watching tennis with him is like watching a movie with somebody who knows a lot about the technical aspects of film: He helps you see things you can't see alone. It turns out, for example, that there are whole geometric sublevels of strategy in a power-baseline game, all dictated by various PBers' strength and weaknesses. A PBer depends on being able to hit winners from the baseline. But, as Sam teaches me to see, Michael Chang can hit winners only at an acute angle from either corner. An "inside-out" player like Jim Courier, though, can hit winners only at obtuse angles from the center out. Hence, wily and well-coached players tend to play Chang "down the middle" and Courier "out wide." One of the things that make Agassi so good is that he's capable of hitting winners from anywhere on the court–he has no geometric restriction. Joyce, too, according to Sam, can hit a winner at any angle. He just doesn't do it quite as well as Agassi, or as often.

Michael Joyce in close-up, viewed eating supper or riding in a courtesy car, looks slighter and younger than he does on-court. Close-up, he looks his age, which to me is basically that of a fetus. Michael Joyce's interests outside tennis consist mostly of big-budget movies and genre novels of the commercial-paperback sort that one reads on airplanes. He has a tight and long-standing group of friends back home in L.A., but one senses that most of his personal connections have been made via tennis. He's dated some. It's impossible to tell whether he's a virgin. It seems staggering and impossible, but my sense is that he might be. Then again, I tend to idealize and distort him, I know, because of how I feel about what he can do on a tennis court. His most revealing sexual comment was made in the context of explaining the odd type of confidence that keeps him from freezing up in a match in front of large crowds or choking on a point when there's lots of money at stake [46] . Joyce, who usually needs to pause about five beats to think before he answer a questions, thinks the confidence is partly a matter of temperament and partly a function of hard work and practice.

"If I'm in like a bar, and there's a really good-looking girl, I might be kind of nervous. But if there's like a thousand gorgeous girls in the stands when I'm playing, it's a different story. I'm not nervous then, when I play, because I know what I'm doing. I know what to do out there." Maybe it's good to let these be his last quoted words.

Whether or not he ends up in the top ten and a name anybody will know, Michael Joyce will remain a paradox. The restrictions on his life have been, in my opinion, grotesque; and in certain ways Joyce himself is a grotesque. But the radical compression of his attention and sense of himself have allowed him to become a transcendent practitioner of an art–something few of us get to be. They've allowed him to visit and test parts of his psychic reserves most of us do not even know for sure we have (courage, playing with violent nausea, not choking, et cetera).

Joyce is, in other words, a complete man, though in a grotesquely limited way. But he wants more. He wants to be the best, to have his name known, to hold professional trophies over his head as he patiently turns in all four directions for the media. He wants this and will pay to have it–to pursue it, let it define him–and will pay up with the regretless cheer of a man for whom issues of choice became irrelevant a long time ago. Already, for Joyce, at twenty-two, it's too late for anything else; he's invested too much, is in too deep. I think he's both lucky and unlucky. He will say he is happy and mean it. Wish him well.

1. Comprising Washington, D.C., Montreal, Los Angeles, Cincinnati, Indianapolis, New Haven, and Long Island, this is possibly the most grueling part of the yearly ATP Tour (as the erstwhile Association of Tennis Professionals Tour is now officially known), with three-digit temperatures and the cement courts shimmering like Moroccan horizons and everyone wearing a hat and even the spectators carrying sweat towels.

2. Joyce lost that final to Thomas Enqvist, now ranked in the ATP's top twenty and a potential superstar and in high profile attendance here in Montreal.

3. Tarango, twenty-seven, who completed three years at Stanford, is regarded as something of a scholar by Joyce and the other young Americans on tour. His little bio in the 1995 ATP Tour Player Guide lists his interests as including, 'philosophy, creative writing, and bridge,' and his slight build and receding hairline do in fact make him look more like an academic or a tax attorney than a world-class tennis player. Also a native Californian, he's a friend and something of a mentor to Michael Joyce, whom he practices with regularly and addresses as 'Grasshopper.' Joyce–who seems to like everybody–likes Jeff Tarango and won't comment on his on-court explosion at Wimbledon except to say that Tarango is 'a very intense guy, very intellectual, that gets kind of paranoid sometimes.'

4. An economical way to be a tournament sponsor: supply free stuff to the tournament and put your name on it in really big letters. All the courts' tall umpire chairs have signs that say TROPICANA; all the bins for fresh and un-fresh towels say WAMSUTTA; the drink coolers at courtside (the size of trash barrels, with clear plastic lids) say TROPICANA and EVIAN. Those players who don't individually endorse a certain brand of drink tend, as a rule, to drink Evian, orange juice being a bit heavy for on-court rehydration.

5. Most of the girlfriends have something indefinable about them that suggests extremely wealthy parents whom the girls are pissing off by hooking up with an obscure professional tennis player.

6. Except for the four in the Grand Slam–Wimbledon and the U.S., French, and Australian opens–no tournament draws all the top players, although every tournament would obviously like to, since the more top players are entered, the better the paid attendance and the more media exposure the tournament gets for itself and its sponsors. Players in the top twenty or so, though, tend to play a comparatively light schedule of tournaments, taking time off not only for rest and training but to compete in wildly lucrative exhibitions that don't affect ATP ranking. (We're talking wildly lucrative, like millions of dollars per annum for the top stars.) Given the sharp divergence of interests between tournaments and players, it's not surprising that there are Kafkanly complex rules for how many ATP tournaments a player must enter each year to avoid financial or ranking-related penalties, and commensurately complex and crafty ways players have for getting around these rules and doing pretty much what they want. These will be passed over. The thing to realize is that players of Michael Joyce's station tend to take way less time off; they play just about every tournament they can squeeze in and get to unless they're forced by injury or exhaustion to sit out a couple of weeks. This is because they need to, not just financially but because under the ATP's (very complex) set of algorithms for determining ranking, most players fare better the more tournaments they enter.

7. There is no qualifying tournament for the qualies themselves, though some particularly huge tournaments have metaqualies. The qualies also have a number of wild-card berths, most of which here are given to Canadian players, like the collegiate legend whom Michael Joyce is beating the shit out of right now in the first round.

8. These places are usually right near the top seeds, which is the reason why in the televised first rounds of major tournaments you usually see Agassi or Sampras beating the shit out of some totally obscure guy–that guy's usually a qualifier. It's also part of why it's so hard for somebody low-ranked enough to have to play the qualies to move up in the rankings enough that he doesn't have to play qualies anymore–he usually meets a high-ranked player in the very first round and gets smeared.

9. Another reason qualifiers usually get smeared by the top players they face in the early rounds is that the qualifier is playing his fourth or fifth match in three days, while the top player usually has had a couple of days with his masseur or creative-visualization consultant to get ready for the first round. Michael Joyce details all these asymmetries and stacked odds the way a farmer speaks of weather, with an absence of emotion that seems deep instead of blank.

10. Pronounced kry -chek.

11. Pronounced ya -kob h la -sick, if that helps.

12. Joyce is even more impressive, but I hadn't seen Joyce yet. And Enqvist is even more impressive than Joyce, and Agassi is even more impressive than Enqvist. After the week was over, I truly understood why Charlton Heston looks gray and ravaged on his descent from Sinai: Past a certain point, impressiveness is corrosive to the psyche.

13. During his two daily one-hour practice sessions, he wears the hat backward and also wears boxy plaid shorts that look for all the world like swim trunks. His favorite practice T-shirt has FEAR: THE ENEMY OF DREAMS on the chest. He laughs a lot when he practices. You can tell just by looking at him out there that he's totally likable and cool.

14. If you've played only casually, it is probably hard to understand how physically demanding really serious tennis is. Realizing that these pros can move one another from one end of the twenty-seven-foot baseline to the other pretty much at will and that they hardly ever end a point by making an unforced error might help your imagination. A close best-of-three-set match is probably equivalent in its demands to a couple of hours of full court basketball, but we're talking serious basketball.

15. Something else you don't get a good sense of on television: Tennis is a very sweaty game. On ESPN or whatever, when you see a player walk over to the ball boy after a point and request a towel and quickly wipe his arm and hand off and toss the towel back to the (rather luckless) ball boy, most of the time the towel thing isn't a stall or a meditative pause–it's done because sweat is running down the inside of the player's arm in such volume that it's getting all over his hand and making the racket slippery. Especially on the sizzling North American summer junket, players sweat through their shirts early on and sometimes also their shorts. And they drink enormous amounts of water–staggering amounts. I thought I was seeing things at first, watching matches, as players seem to go through one of those skinny half-liter Evian bottles every second side change, but Michael Joyce confirmed it. Pro-grade tennis players seem to have evolved a metabolic system that allows rapid absorption of water and its transformation into sweat. (Most players I spoke with confirmed, by the way, that Gatorade and All-Sport and Boost and all those pricey sports drinks are mostly bullshit; that salt and carbs at table and small lakes of daily H2O are the way to go. The players who didn't confirm this turned out to be players who had endorsement deals with some pricey-sports-drink manufacturer, but I personally saw at least one such player dumping out his bottled pricey electrolyte contents and replacing them with good old water for his match.)

16. The taller you are, the harder you can serve (get a protractor and figure it out), but the less able to bend and reverse direction you are. Tall guys tend to be serve-and-volleyers, and they live and die by their serves. Bill Tilden, Stan Smith, Arthur Ashe, Roscoe Tanner, and Goran Ivanisevic were/are all tall guys with serve-dependent games. And so on.

17. This is mind-bogglingly hard to do when the ball's hit hard. If we can assume you've played Little League or sandlot ball or something, imagine the hardest-hit grounder of all time coming at you at shortstop, and you not standing and waiting to try to knock it down but actually of your own free will running forward toward the grounder, then trying not just to catch it in a big glove but to strike it hard and reverse its direction and send it someplace frightfully specific and very far away–this comes close.

18. Joyce could have gone to college, but if he'd gone to college, it would have been primarily to play tennis. Coaches at major universities apparently offered Joyce inducements to come play for them so literally outrageous and incredible that I wouldn't repeat them here even if Joyce hadn't asked me not to.

The reason Michael Joyce would have gone to college primarily to play tennis is that the academic and social aspects of collegiate life interest him about as much as hitting twenty-five hundred crosscourt forehands while a coach yells at you in foreign languages interests you. Tennis is what Michael Joyce loves and lives for and is. He sees little point in telling anybody anything different. It's the only thing he's devoted himself to, and he's devoted massive amounts of himself to it, and, as far as he understands it, it's all he wants to do or be involved in. Because he started playing at age two and playing competitively at age seven and had the first half-dozen years of his career directed rather, shall we say, forcefully and enthusiastically by his father (who Joyce estimates probably spent around $250,000 on lessons and court time and equipment and travel during Michael's junior career), it's perhaps reasonable to ask Joyce to what extent he chose to devote himself to tennis. Can you choose something when you are forcefully and enthusiastically immersed in it at an age when the resources and information necessary for choosing are not yet yours?

Joyce's response to this line of inquiry strikes me as both unsatisfactory and totally satisfactory. Because the question is unanswerable, or at least it's unanswerable by a person who's already–as far as he understands it– chosen . Joyce's answer is that it doesn't really matter much to him whether he originally 'chose' serious tennis or not; all he knows is that he loves it. He tries to explain the U.S. juniors, which he won in 1991: 'You get there and look at the draw; it's a 128 draw–there's so many guys you have to beat. And then it's all over and you've won, you're the national champion–there's nothing like it. I get chills even talking about it.' Or just the previous week in Washington: 'I'm playing Agassi, and it's great tennis, and there's nothing like thousands of fans going nuts. I can't describe the feeling. Where else could I get that?'

What he says is understandable, but it's not the satisfactory part of the answer. The satisfactory part is the way Joyce's face looks when he talks about what tennis means to him. He loves it–you can see this in his face when he talks about it: His eyes normally have a kind of Asiatic cast because of a slight epicanthic fold common to ethnic Irishmen, but when he speaks of tennis and his career, the eyes get round and the pupils dilate and the look in them is one of love. The love is not the love one feels for a job or a lover or any of the loci of intensity that most of us choose to call the things we love. It's the sort of love you see in the eyes of really old people who've been married for an incredibly long time or in religious people who are so religious, they've devoted their whole lives to religious stuff: It's the sort of love whose measure is what it's cost, what one's given up for it. Whether there's 'choice' involved is, at a certain point, of no interest ... since it's the surrender of choice and self that informs the love in the first place.

19. Aka serve-and-volley, see immediately supra .

20. I don't know whether you know this, but Connors had one of the most eccentric games in the history of tennis -- he was an aggressive 'power' player who rarely came to the net, had the serve of an ectomorphic girl, and hit everything totally spinless and flat (which is inadvisable on ground strokes because the absence of spin makes the ball so hard to control). His game was all the more strange because the racket he generated all his firepower from the baseline with was a Wilson T2000, a weird steel thing that's one of the shittiest tennis rackets ever made and is regarded by most serious players as useful only for home defense or prying large rocks out of your backyard or something. Connors was addicted to this racket and kept using it long after Wilson stopped even making it, and he forfeited millions in potential endorsement money by doing so. Connors was also eccentric (and kind of repulsive) in lots of other ways, too, none of which are germane to this article.

21. In the yore days before wide-body ceramic rackets and scientific strength training, the only two venues for hitting winners used to be the volley–where your decreased distance from the net allowed for greatly increased angle (get that protractor out)–and the defensive passing shot, i.e., in the tactical language of boxing, 'punch' versus 'counterpunch.' The new power-baseline game allows a player, in effect, to punch his opponent all the way from his stool in the corner; it changes absolutely everything, and the analytic geometry of these changes would look like the worst calculus final you ever had in your life.

22. This is one reason why the phenomenon of 'breaking serve' in a set is so much less important when a match involves power-baseliners. It is one reason why so many older players and fans no longer like to watch pro tennis as much: The structural tactics of the game are now ineluctably different from when they played.

23. A trademark of the Wichita, Kans., Kock Materials Company, 'a leader in asphalt-emulsions technology.'

24. John McEnroe wasn't all that tall, and he was arguably the best serve-and-volley man of all time, but then McEnroe was an exception to pretty much every predictive norm there was. At his peak (say 1980-1984), he was the greatest tennis player who ever lived–the most talented, the most beautiful, the most tormented: a genius. For me, watching McEnroe don a blue polyester blazer and do stiff lame truistic color commentary for TV is like watching Faulkner do a Gap ad.

25. One answer to why public interest in men's tennis has been on the wane in recent years is an essential and unpretty thuggishness about the power-baseline style that's become dominant on the tour. Watch Agassi closely sometime–for so small a man and so great a player, he's amazingly absent of finesse, with movements that look more like a heavy-metal musician's than an athlete's.

The power-baseline game itself has been compared to metal or grunge. But what a top PBer really resembles is film of the old Soviet Union putting down a rebellion. It's awesome, but brutally so, with a grinding, faceless quality about its power that renders that power curiously dull and empty.

26. Compare Ivanisevic's at 136 miles per hour or Sampras's at 132 or even this Brakus kid's at 118.

27. The loop in a pro's backswing is kind of the trademark flourish of excellence and consciousness of the same, not unlike the five-star chef's quick kiss of his own fingertips as he presents a piece or the magician's hand making a French curl in the air as he directs our attention to his vanished assistant.

28. All serious players have these little extraneous tics, stylistic fingerprints, and the pros even more so because of years of repetition and ingraining. Pros' tics have always been fun to note and chart, even just e.g. on the serve. Watch the way Sampras' lead foot rises from the heel on his toss, as if his left foot's toes got suddenly hot. The odd Tourettic way Gerulaitis used to whip his head from side to side while bouncing the ball before the toss, as if he were having a small seizure. McEnroe's weird splayed stiff-armed service stance, both feet parallel to the baseline and his side so severely to the net that he looked like a figure on an Egyptian frieze. The odd sudden shrug Lendl gives before releasing his toss. The way Agassi shifts his weight several times from foot to foot as he bounces before the toss like he needs desperately to pee. Or, here at the Canadian Open, the way the young star Thomas Enqvist's body bends queerly back as he tosses, limboing away from the toss, as if for a moment the ball smelled very bad. This tic derives from Enqvist's predecessor Edberg's own weird spinal arch and twist on the toss. Edberg also has this strange sudden way of switching his hold on the racket in mid-toss, changing from an eastern forehand to an extreme backhand grip, as if the racket were a skillet.

29. Who looks a bit like a Hispanic Dustin Hoffman and is an almost unbelievably nice guy, with the sort of inward self-sufficiency of truly great teachers and coaches everywhere, with the Zen-like blend of focus and calm developed by people who have to spend enormous amounts of time sitting in one place watching closely while somebody else does something. Sam gets 10 percent of Joyce's gross revenues and spends his time in airports reading gigantic tomes on Mayan architecture and is one of the coolest people I've ever met either inside the tennis world or outside it (so cool I'm kind of scared of him and haven't once called him since the assignment ended, if that makes sense). In return, Sam travels with Joyce, rooms with him, coaches him, supervises his training, analyzes matches with him, and attends him in practice, even to the extent of picking up errant balls so that Joyce doesn't have to spend part of his tightly organized practice time picking up errant balls. The stress and weird loneliness of pro tennis, where everybody's in the same community and sees one another every week but is constantly on the diasporic move and is one another's rival, with enormous amounts of money at stake and life essentially a montage of airports and bland hotels and non-home-cooked food and courtesy cars and nagging injuries and staggering long-distance bills, and with people's families back home tending to be wackos, since only wackos would make the financial and temporal sacrifices necessary to let their offspring become good enough at something to turn pro at it–all this means that most players lean heavily on their coaches for emotional support and friendship as well as technical counsel. Sam's role with Joyce looks to me to approximate what in the latter century was called that of 'companion,' those older ladies who traveled with nubile women when they traveled abroad.

30. Agassi's balls look more like Borg's balls would have looked if Borg had been on a yearlong regimen of both steroids and methamphetamines and was hitting every single fucking ball just as hard as he could. Agassi hits his ground strokes as hard as anybody who's ever played tennis–so hard you almost can't believe it in person.

31. But Agassi does have this exaggerated follow-through in which he keeps both hands on the racket and follows through almost like a hitter in baseball, which causes his shirtfront to lift and his hairy tummy to be exposed to public view–in Montreal I found this repellent, though the females in the stands around me seem ready to live and die for a glimpse of Agassi's tummy. Agassi's significant other, Brooke Shields, is in Montreal, by the way, and will end up highly visible in the player-guest box for all Agassi's matches wearing big sunglasses and what look to be multiple hats. This may be the place to insert that Brooke Shields is rather a lot taller than Agassi and considerably less hairy, and that seeing them standing together in person is rather like seeing Sigourney Weaver on the arm of Danny DeVito. The effect is especially surreal when Brooke is wearing one of the plain, classy sundresses that make her look like a deb summering in the Hamptons and Agassi's wearing his new Nike on-court ensemble, a blue-black horizontally striped outfit that together with his black sneakers makes him look like somebody's idea of a French Resistance fighter. (Since we all enjoy celeb stuff, this might also be the place to insert an unkind but true observation. Up close in person, Brooke Shields is in fact extremely pretty, but she is not at all sexy. Her eyebrows are actually not nearly as thick/bushy as Groucho's or Brezhnev's, but she's incredibly tall, and her posture's not all that great, and her prettiness is that sort of computer-enhanced-looking prettiness that is resoundingly unsexy. To find somebody sexy, I think you actually have to be able to imagine having sex with them, and something intrinsically remote and artificial about Brooke Shields makes it possible to imagine jacking off to a picture of her but not to imagine actually having sex with her.)

32. Some tennis writer somewhere observed of Michael Chang that whereas all pros up at net will run back to retrieve a lob placed over their heads, Chang is the only pro known sometimes to run back and retrieve passing shots .

33. Though note that very few of them wear eyeglasses, either.

34. A whole other kind of vision–the kind attributed to Larry Bird in basketball, sometimes, when he's made those incredible surgical passes to people who nobody else could even see were open–is required when you're hitting: This involves seeing the other side of the court–where your opponent is and which direction he's moving in and what possible angles are open to you in consequence of where he's going. The schizoid thing about tennis is that you have to use both kinds of vision–ball and court–at the same time.

35. Basketball comes close, but it's a team sport and lacks tennis' primal mano a mano intensity. Boxing might come close–at least at the lighter weight divisions–but the actual physical damage the fighters inflict on each other makes it too concretely brutal to be really beautiful–a level of abstraction and formality (i.e., 'play') is necessary for a sport to possess true metaphysical beauty (in my opinion).

36. For those of you into business stats, the calculus of a shot in tennis would be rather like establishing a running compound-interest expansion in a case in which not only is the rate of interest itself variable and not only are the determinants of that rate variable and not only is the amount of time during which the determinants influence the interest rate variable, but the principle itself is variable.

37. Sex and substance issues notwithstanding, professional athletes are our culture's holy men: They give themselves over to a pursuit, endure great privation and pain to actualize themselves at it, and enjoy a relationship to 'excellence' and 'perfection' that we admire and reward (the monk's begging bowl, the RBI guru's eight-figure contract) and like to watch, even though we have no inclination to walk that road ourselves. In other words, they do it for us, sacrifice themselves for our redemption.

38. Meaning a two-handed forehand, whose pioneer was a South African named Frew McMillan and whose most famous practitioner today is Monica Seles.

39. The idea of what it would be like to perspire heavily with huge amounts of gel in your hair is sufficiently horrific to me that I approach Knowle after the match to ask him about it, only to discover that neither he nor his coach spoke enough English–or even French–to be able to determine who I was, and the whole sweat-and-gel issue will, I'm afraid, remain a matter for your own imagination.

40. Who is clearly such a fundamentally nice guy that he would probably hit around with me for a little while just out of politeness, since for him it would be at worst a little bit dull. For me, though, it would be, as I said, a little obscene.