- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Morality?

Morality is the behavior and beliefs that a society deems acceptable

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

How Morals Are Established

Morals that transcend time and culture, examples of morals, morality vs. ethics, morality and laws.

Morality refers to the set of standards that enable people to live cooperatively in groups. It’s what societies determine to be “right” and “acceptable.”

Sometimes, acting in a moral manner means individuals must sacrifice their own short-term interests to benefit society. Individuals who go against these standards may be considered immoral.

It may be helpful to differentiate between related terms, such as immoral , nonmoral , and amoral . Each has a slightly different meaning:

- Immoral : Describes someone who purposely commits an offensive act, even though they know the difference between what is right and wrong

- Nonmoral : Describes situations in which morality is not a concern

- Amoral : Describes someone who acknowledges the difference between right and wrong, but who is not concerned with morality

Morality isn’t fixed. What’s considered acceptable in your culture might not be acceptable in another culture. Geographical regions, religion, family, and life experiences all influence morals.

Scholars don’t agree on exactly how morals are developed. However, there are several theories that have gained attention over the years:

- Freud’s morality and the superego: Sigmund Freud suggested moral development occurred as a person’s ability to set aside their selfish needs were replaced by the values of important socializing agents (such as a person’s parents).

- Piaget’s theory of moral development: Jean Piaget focused on the social-cognitive and social-emotional perspective of development. Piaget theorized that moral development unfolds over time, in certain stages as children learn to adopt certain moral behaviors for their own sake—rather than just abide by moral codes because they don’t want to get into trouble.

- B.F. Skinner’s behavioral theory: B.F. Skinner focused on the power of external forces that shaped an individual’s development. For example, a child who receives praise for being kind may treat someone with kindness again out of a desire to receive more positive attention in the future.

- Kohlberg’s moral reasoning: Lawrence Kohlberg proposed six stages of moral development that went beyond Piaget’s theory. Through a series of questions, Kohlberg proposed that an adult’s stage of reasoning could be identified.

What Is the Basis of Morality?

There are different theories as to how morals are developed. However, most theories acknowledge the external factors (parents, community, etc.) that contribute to a child's moral development. These morals are intended to benefit the group that has created them.

Most morals aren’t fixed. They usually shift and change over time.

Ideas about whether certain behaviors are moral—such as engaging in pre-marital sex, entering into same-sex relationships, and using cannabis—have shifted over time. While the bulk of the population once viewed these behaviors as “wrong,” the vast majority of the population now finds these activities to be “acceptable.”

In some regions, cultures, and religions, using contraception is considered immoral. In other parts of the world, some people consider contraception the moral thing to do, as it reduces unplanned pregnancy, manages the population, and reduces the risk of STDs.

7 Universal Morals

Some morals seem to transcend across the globe and across time, however. Researchers have discovered that these seven morals seem somewhat universal:

- Defer to authority

- Help your group

- Love your family

- Return favors

- Respect others’ property

The following are common morality examples that you may have been taught growing up, and may have even passed on to younger generations:

- Have empathy

- Don't steal

- Tell the truth

- Treat others as you want to be treated

People might adhere to these principles by:

- Being an upstanding citizen

- Doing volunteer work

- Donating money to charity

- Forgiving someone

- Not gossiping about others

- Offering their help to others

To get a sense of the types of morality you were raised with, think about what your parents, community and/or religious leaders told you that you "should" or "ought" to do.

Some scholars don’t distinguish between morals and ethics. Both have to do with “right and wrong.”

However, some people believe morality is personal while ethics refer to the standards of a community.

For example, your community may not view premarital sex as a problem. But on a personal level, you might consider it immoral. By this definition, your morality would contradict the ethics of your community.

Both laws and morals are meant to regulate behavior in a community to allow people to live in harmony. Both have firm foundations in the concept that everyone should have autonomy and show respect to one another.

Legal thinkers interpret the relationship between laws and morality differently. Some argue that laws and morality are independent. This means that laws can’t be disregarded simply because they’re morally indefensible.

Others believe law and morality are interdependent. These thinkers believe that laws that claim to regulate behavioral expectations must be in harmony with moral norms. Therefore, all laws must secure the welfare of the individual and be in place for the good of the community.

Something like adultery may be considered immoral by some, but it’s legal in most states. Additionally, it’s illegal to drive slightly over the speed limit but it isn’t necessarily considered immoral to do so.

There may be times when some people argue that breaking the law is the “moral” thing to do. Stealing food to feed a starving person, for example, might be illegal but it also might be considered the “right thing” to do if it’s the only way to prevent someone from suffering or dying.

A Word From Verywell

It can be helpful to spend some time thinking about the morals that guide your decisions about things like friendship, money, education, and family. Understanding what’s really important to you can help you understand yourself better and it may make decision making easier.

Merriam-Webster. A lesson on 'unmoral,' 'immoral,' 'nonmoral,' and 'amoral.'

Ellemers N, van der Toorn J, Paunov Y, van Leeuwen T. The psychology of morality: A review and analysis of empirical studies published from 1940 through 2017 . Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2019;23(4):332-366. doi:10.1177/1088868318811759

Curry OS, Mullins DA, Whitehouse H. Is it good to cooperate? Testing the theory of morality-as-cooperation in 60 societies . Current Anthropology. 2019;60(1):47-69. doi:10.1086/701478

What's the difference between morality and ethics? Encyclopædia Britannica.

Moka-Mubelo W. Law and morality . Reconciling Law and Morality in Human Rights Discourse. Philosophy and Politics - Critical Explorations . 2017;3. Springer, Cham. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-49496-8_3

By Amy Morin, LCSW Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

Ethics and Morality Relationship Essay

Introduction, relationship between ethics and morality, ethical choices available to hr managers.

Bibliography

Over the years, ethics and morality have often been used synonymously. Although the two terms are closely related both in conceptual and ideal meaning, they have both differences and similarities. This paper, therefore, discusses the relationship between ethics and morality, giving examples of each, and also explores the ethical choices available for human resources managers.

Ethics is a term used to refer to the body of doctrines that guide individuals to behave in a way that is ideologically right, fine, and appropriate. Guidelines or principles that constitute do not at all times lead an individual towards just a solitary moral but act as a way to direct the individual to follow a set of codes of conducts whose objective is to foster overall desirable behaviors in an individual or a group of people (George, 2006).

According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ethics are regulations that are clearly stipulated and that guide individuals in determining what to do and what not to. In many organizations, ethics are guided by sets of written laws and regulations that guide the way individuals within them should behave (Conroy & Emerson, 2004).

For example, there could be written principles that guide the way customer service should be undertaken in the organization, rules guarding salespeople against selling inappropriate products to the customers, rules guarding against corruption or undue extortion of money from the customers, principles that direct employees to behave in the highest level of professionalism, integrity, honesty, and humility while serving customers and which are well written down in the organization’s code of conduct.

According to Peterson et al (2005), ethics are a set of rules that direct individuals to decide to act in a correct way. The latter asserts that ethics are embedded in and guided by laws that redirect individuals from doing what their conscience directs them to do and do what is morally correct i.e. they help an individual to avoid doing what he or she wants to but rather do what is correct in moral standards. For instance, someone’s conscience tells him to climb up a neighbor’s apple tree to eat his apples without the latter’s consent, but he shrugs off his personal selfish feelings and abstains from doing such a thing and which he has the power to do due to the respect for the neighbor and his property. The person will make a decision not to eat the neighbor’s apples hence he will have acted in an ethical way.

Ethics leads to honesty, a show of respect for others, and behavior that is consistent with one’s obligation as a member of the organization or a citizen to a country (Conroy & Emerson, 2004). According to the latter, ethics are not innate in an individual but are mainly exotically controlled by laws and regulations are set and enforced by human beings or authority. For example, ethics in marketing are controlled by laws that restrict marketers from engaging in business malpractices such as unhealthy competition, poor product prices, overpricing, and hoarding among other business vices.

George (2006) defines morality from two main perspectives. From an individuals’ perspective, morality is a set of individual’s standards, principles, or customs that greatly shapes an individual’s character trait and way of behavior or the level of which an individual is able to willingly uphold the generally accepted standards of behaviors within a society that he lives in at a specific instance in time. On the other hand, George asserts that societal morals are the universally acceptable code of conduct in a certain society at a specific point of time, and which autonomously guides the behavior of its members.

For instance, stealing is generally not acceptable in society at any one time. As such, it is immoral to steal. In the same way, if the society holds that it is moral to belong to a religion in the 21 st century, it would be immoral according to such a society for a member to be without religion. Similarly, in a society that prostitution is rebuked, it would be immoral for an individual within it to engage in prostitution. Societal standards/ principles change rapidly over time. Similarly, moral standards within a society will vary with time. For example, it was moral to hold slaves in the past. However, this is no longer acceptable in modern society hence it would be immoral for an individual to hold a slave today.

Ethics are guidelines for proper behavior or conduct and they are absolutely not pegged to the specified period in time. As a result, they usually have limited variations overtimes. On the other hand, morality is the acceptable standard within a society at a given point in time (Peterson et al, 2005).

As a result, they change over time. Ethics are more basic and permanent than morality; hence morality is a subset of ethics. Similarly, ethics lead to morality whereas vice versa is not applicable. Moreover, a change in ethics is likely to generate a change in morality. In circumstances where a society or institution amends its code of ethics, the moral standards will obviously be altered (Peterson et al, 2005).

For example, the ethical code of conduct led to the alteration of the slavery law in the eighteenth century which led to slavery being regarded as immoral since then. Unlike the ethical code of conduct which is entrenched in the written artificial laws, morality is more or less entrenched in and controlled by the individual’s personality. As a result, a change in a person’s character trait for the better will make him or her more moral and vice versa. However, the similarity between ethics and morality is that they are all geared towards enhancing the desirable relationship between individuals in the organization, institutions, or society in which they live (Peterson et al, 2005).

There are several ethical choices that are available to human resource managers. These include:

Equity in opportunities and neutrality

Employment takes place in a multifaceted environment. As a result it is ethical for the human resource managers involved in the employment or appointment of personnel in the organization to give equal opportunity for various individual interested in the job to compete on a level ground and pick the most suitable for the job without any discrimination whatsoever(University of Western Australia, 2007). For instance, the recruitment process should be devoid of nepotism, corruption, undue charges to the candidates, bias and prejudices. Employment should be carried out via an open, fair and due process. In addition, HR managers should desist from taking positions that appears to favor one side during dissolution of employees disputes (Lowry , 2006).

Fairness in the treatment of employees and quietism

HR manager will be ethical if they establish an organizational environment in which all employees are treated in a just manner. For instance, the managers should ensure equitable reward system for all employees, just promotions and a system that is without favoritism based on any aspects. In addition, employees need to be treated like people with rights to be honored and defended by the HR manager (Lowry , 2006).

Sexual harassment of employees

The human resources managers will be ethical if they desist from gender stereotypes and sexual harassment of employees. Cases of sexually mistreating of employees by human resources managers are not only unethical but absolutely unacceptable and illegal (University of Western Australia, 2007). For instance, some manager demand for sexual relations with female employees as a leeway to giving them a favor, promotion, salary increment or even initial employment which is against the HR ethical code of conduct (Lowry , 2006).

Privacy and Confidentiality

Human resources code of ethics requires that employee privacy and personal life be respected at all times. For instance, it will be in breach of the ethical code of HR to force the employee to reveal his sexual life information (University of Western Australia, 2007). In addition it is the duty of the manager to safeguard the information given to him by the employees, by treating it with the highest level of confidentiality (Lowry , 2006). For example, if the HR has the information of the employee’s health profile, such information must not be released to the outside without the consent of the employee.

Poaching of employees

In industry HR managers may tend to poach competitors employees so as to lessen their competitive power. In doing this they entice the competitors employees in order to gain undue advantage over rivals which is unethical (University of Western Australia, 2007). In addition ethical human resource managers should be ethically assertive. Remain neutral in resolving employee’s disputes, ethical in dealing with errant employees and should be ethically reactive.

Ethics and morality are two terms that are closely related and which individuals often tend to refer to synonymously. However, the two are different in that while ethics are sets of principles that guide desirable behavior or conducts, morality is the generally acceptable behavior within a society at a given period of time. In addition, morality unlike ethics keeps on changing from time to time as societal values change (Peterson et al, 2005).

Conclusively, it can be held that morality is a subset of ethics since ethics shapes morality while ethics is bigger than morality. Finally, the ethical choices available for HR managers includes, offering equal opportunities in employment, treating all employees fairly, respecting the employees, avoiding ill-led poaching of competitors employees to gain undue advantage over them, respecting employees privacy and confidentiality of information and not sexually mistreating employees. Breaching any of these will be unethical on the part of the HR manger.

Conroy, S.J. and Emerson, (2004) “Business Ethics and Religion: Religiosity as a Predictor of Ethical Awareness among Student Inc Journal of Business Ethics 50 (4):247-258.

George Desnoyers (2006), the relationship between ethics and morality: Inc the Journal of behavioral psychology. Vol. 11 167-186.

Lowry , 2006, Ethical Choices for HR Managers Inc Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources; 44; p.171.

Peterson, et al (2005) Ethics vs. Morality – The Distinction between Ethics and Morals. Web.

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy- The Definition of Morality. Web.

University of Western Australia (2007), code of ethics and code of conduct for human resources. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, March 12). Ethics and Morality Relationship. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ethics-and-morality-relationship/

"Ethics and Morality Relationship." IvyPanda , 12 Mar. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/ethics-and-morality-relationship/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Ethics and Morality Relationship'. 12 March.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Ethics and Morality Relationship." March 12, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ethics-and-morality-relationship/.

1. IvyPanda . "Ethics and Morality Relationship." March 12, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ethics-and-morality-relationship/.

IvyPanda . "Ethics and Morality Relationship." March 12, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/ethics-and-morality-relationship/.

- Undue Influence's Case: Atlas Express v. Kafko Ltd

- HR Managers Challenges: Recruiting Expatriates

- Strategic Human Resource Management Concept and HR Manager Role

- Permanent HR Manager or Temporary Manager

- Contractual Capacity and Legality: Case Analysis

- HR Manager: Strategic Partner in Today’s Organisations

- HR Managers and Cultural Differences

- Job Evaluation of the HR Manager: Performance, Safety, and Professional Development

- Failure to Achieve “Meeting of the Minds”

- Rights, Equity and the State: Dispute Resolution Case

- Ethical Problem of Abortion

- Organ Donation: Ethical Dilemmas

- Ethical Practices in the Workplace

- Moral Clients & Agents and Their Evaluation

- Abortion in Islamic View

Subscribe to our newsletter

15 great articles and essays about ethics and morality, on morality by joan didion, the moral instinct by stephen pinker, the greatest good by derek thompson, stop trying to save the world by michael hobbes, army of altruists by david graeber, the myth of the ethical shopper by michael hobbes, tragedy. call. compassion. response. by roxane gay, the business of voluntourism by tina rosenberg, the backfire effect by david mcraney, see also..., 50 great psychology articles, 100 great articles about science and technology, articles cont., in defense of prejudice by jonathan rauch, not nothing by stephen cave, what's so bad about hate by andrew sullivan, the ethics paradox by chuck klosterman.

About The Electric Typewriter We search the net to bring you the best nonfiction, articles, essays and journalism

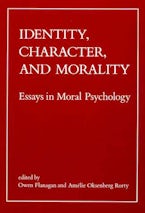

Identity, Character, and Morality : Essays in Moral Psychology

Owen Flanagan is James B. Duke Professor of Philosophy at Duke University. He is the author of Consciousness Reconsidered and The Really Hard Problem: Meaning in a Material World , both published by the MIT Press, and other books.

Many philosophers believe that normative ethics is in principle independent of psychology. By contrast, the authors of these essays explore the interconnections between psychology and moral theory. They investigate the psychological constraints on realizable ethical ideals and articulate the psychological assumptions behind traditional ethics. They also examine the ways in which the basic architecture of the mind, core emotions, patterns of individual development, social psychology, and the limits on human capacities for rational deliberation affect morality.

Bradford Books imprint

- Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

Identity, Character, and Morality : Essays in Moral Psychology Edited by: Owen Flanagan, Amélie Oksenberg Rorty https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3645.001.0001 ISBN (electronic): 9780262272766 Publisher: The MIT Press Published: 1990

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Table of Contents

- [ Front Matter ] Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3645.003.0029 Open the PDF Link PDF for [ Front Matter ] in another window

- Acknowledgments Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3645.003.0001 Open the PDF Link PDF for Acknowledgments in another window

- Introduction By Owen Flanagan , Owen Flanagan Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Amélie Oksenberg Rorty Amélie Oksenberg Rorty Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3645.003.0002 Open the PDF Link PDF for Introduction in another window

- 1: Aspects of Identity and Agency By Amélie Oksenberg Rorty , Amélie Oksenberg Rorty Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar David Wong David Wong Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3645.003.0004 Open the PDF Link PDF for 1: Aspects of Identity and Agency in another window

- 2: Identity and Strong and Weak Evaluation By Owen Flanagan Owen Flanagan Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3645.003.0005 Open the PDF Link PDF for 2: Identity and Strong and Weak Evaluation in another window

- 3: The Moral Life of a Pragmatist By Ruth Anna Putnam Ruth Anna Putnam Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3645.003.0006 Open the PDF Link PDF for 3: The Moral Life of a Pragmatist in another window

- 4: Natural Affection and Responsibility for Character: A Critique of Kantian Views of the Virtues By Gregory Trianosky Gregory Trianosky Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3645.003.0008 Open the PDF Link PDF for 4: Natural Affection and Responsibility for Character: A Critique of Kantian Views of the Virtues in another window

- 5: On the Old Saw That Character Is Destiny By Michele Moody-Adams Michele Moody-Adams Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3645.003.0009 Open the PDF Link PDF for 5: On the Old Saw That Character Is Destiny in another window

- 6: Hume and Moral Emotions By Marcia Lind Marcia Lind Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3645.003.0010 Open the PDF Link PDF for 6: Hume and Moral Emotions in another window

- 7: The Place of Emotions in Kantian Morality By Nancy Sherman Nancy Sherman Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3645.003.0011 Open the PDF Link PDF for 7: The Place of Emotions in Kantian Morality in another window

- 8: Vocation, Friendship, and Community: Limitations of the Personal-Impersonal Framework By Lawrence A. Blum Lawrence A. Blum Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3645.003.0013 Open the PDF Link PDF for 8: Vocation, Friendship, and Community: Limitations of the Personal-Impersonal Framework in another window

- 9: Gender and Moral Luck By Claudia Card Claudia Card Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3645.003.0014 Open the PDF Link PDF for 9: Gender and Moral Luck in another window

- 10: Friendship and Duty: Some Difficult Relations By Michael Stocker Michael Stocker Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3645.003.0015 Open the PDF Link PDF for 10: Friendship and Duty: Some Difficult Relations in another window

- 11: Trust, Affirmation, and Moral Character: A Critique of Kantian Morality By Laurence Thomas Laurence Thomas Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3645.003.0016 Open the PDF Link PDF for 11: Trust, Affirmation, and Moral Character: A Critique of Kantian Morality in another window

- 12: Why Honesty Is a Hard Virtue By Annette C. Baier Annette C. Baier Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3645.003.0017 Open the PDF Link PDF for 12: Why Honesty Is a Hard Virtue in another window

- 13: Higher-Order Discrimination By Adrian M. S. Piper Adrian M. S. Piper Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3645.003.0019 Open the PDF Link PDF for 13: Higher-Order Discrimination in another window

- 14: Obligation and Performance: A Kantian Account of Moral Conflict By Barbara Herman Barbara Herman Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3645.003.0020 Open the PDF Link PDF for 14: Obligation and Performance: A Kantian Account of Moral Conflict in another window

- 15: Rational Egoism, Self, and Others By David O. Brink David O. Brink Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3645.003.0021 Open the PDF Link PDF for 15: Rational Egoism, Self, and Others in another window

- 16: Is Akratic Action Always Irrational? By Alison McIntyre Alison McIntyre Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3645.003.0022 Open the PDF Link PDF for 16: Is Akratic Action Always Irrational? in another window

- 17: Rationality, Responsibility, and Pathological Indifference By Stephen L. White Stephen L. White Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3645.003.0023 Open the PDF Link PDF for 17: Rationality, Responsibility, and Pathological Indifference in another window

- 18: Some Advantages of Virtue Ethics By Michael Slote Michael Slote Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3645.003.0025 Open the PDF Link PDF for 18: Some Advantages of Virtue Ethics in another window

- 19: On the Primacy of Character By Gary Watson Gary Watson Search for other works by this author on: This Site Google Scholar Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3645.003.0026 Open the PDF Link PDF for 19: On the Primacy of Character in another window

- Bibliography Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3645.003.0027 Open the PDF Link PDF for Bibliography in another window

- Contributors Doi: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3645.003.0028 Open the PDF Link PDF for Contributors in another window

- Open Access

A product of The MIT Press

Mit press direct.

- About MIT Press Direct

Information

- Accessibility

- For Authors

- For Customers

- For Librarians

- Direct to Open

- Media Inquiries

- Rights and Permissions

- For Advertisers

- About the MIT Press

- The MIT Press Reader

- MIT Press Blog

- Seasonal Catalogs

- MIT Press Home

- Give to the MIT Press

- Direct Service Desk

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Statement

- Crossref Member

- COUNTER Member

- The MIT Press colophon is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Ethics and Morality

Morality, Ethics, Evil, Greed

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

To put it simply, ethics represents the moral code that guides a person’s choices and behaviors throughout their life. The idea of a moral code extends beyond the individual to include what is determined to be right, and wrong, for a community or society at large.

Ethics is concerned with rights, responsibilities, use of language, what it means to live an ethical life, and how people make moral decisions. We may think of moralizing as an intellectual exercise, but more frequently it's an attempt to make sense of our gut instincts and reactions. It's a subjective concept, and many people have strong and stubborn beliefs about what's right and wrong that can place them in direct contrast to the moral beliefs of others. Yet even though morals may vary from person to person, religion to religion, and culture to culture, many have been found to be universal, stemming from basic human emotions.

- The Science of Being Virtuous

- Understanding Amorality

- The Stages of Moral Development

Those who are considered morally good are said to be virtuous, holding themselves to high ethical standards, while those viewed as morally bad are thought of as wicked, sinful, or even criminal. Morality was a key concern of Aristotle, who first studied questions such as “What is moral responsibility?” and “What does it take for a human being to be virtuous?”

We used to think that people are born with a blank slate, but research has shown that people have an innate sense of morality . Of course, parents and the greater society can certainly nurture and develop morality and ethics in children.

Humans are ethical and moral regardless of religion and God. People are not fundamentally good nor are they fundamentally evil. However, a Pew study found that atheists are much less likely than theists to believe that there are "absolute standards of right and wrong." In effect, atheism does not undermine morality, but the atheist’s conception of morality may depart from that of the traditional theist.

Animals are like humans—and humans are animals, after all. Many studies have been conducted across animal species, and more than 90 percent of their behavior is what can be identified as “prosocial” or positive. Plus, you won’t find mass warfare in animals as you do in humans. Hence, in a way, you can say that animals are more moral than humans.

The examination of moral psychology involves the study of moral philosophy but the field is more concerned with how a person comes to make a right or wrong decision, rather than what sort of decisions he or she should have made. Character, reasoning, responsibility, and altruism , among other areas, also come into play, as does the development of morality.

The seven deadly sins were first enumerated in the sixth century by Pope Gregory I, and represent the sweep of immoral behavior. Also known as the cardinal sins or seven deadly vices, they are vanity, jealousy , anger , laziness, greed, gluttony, and lust. People who demonstrate these immoral behaviors are often said to be flawed in character. Some modern thinkers suggest that virtue often disguises a hidden vice; it just depends on where we tip the scale .

An amoral person has no sense of, or care for, what is right or wrong. There is no regard for either morality or immorality. Conversely, an immoral person knows the difference, yet he does the wrong thing, regardless. The amoral politician, for example, has no conscience and makes choices based on his own personal needs; he is oblivious to whether his actions are right or wrong.

One could argue that the actions of Wells Fargo, for example, were amoral if the bank had no sense of right or wrong. In the 2016 fraud scandal, the bank created fraudulent savings and checking accounts for millions of clients, unbeknownst to them. Of course, if the bank knew what it was doing all along, then the scandal would be labeled immoral.

Everyone tells white lies to a degree, and often the lie is done for the greater good. But the idea that a small percentage of people tell the lion’s share of lies is the Pareto principle, the law of the vital few. It is 20 percent of the population that accounts for 80 percent of a behavior.

We do know what is right from wrong . If you harm and injure another person, that is wrong. However, what is right for one person, may well be wrong for another. A good example of this dichotomy is the religious conservative who thinks that a woman’s right to her body is morally wrong. In this case, one’s ethics are based on one’s values; and the moral divide between values can be vast.

Psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg established his stages of moral development in 1958. This framework has led to current research into moral psychology. Kohlberg's work addresses the process of how we think of right and wrong and is based on Jean Piaget's theory of moral judgment for children. His stages include pre-conventional, conventional, post-conventional, and what we learn in one stage is integrated into the subsequent stages.

The pre-conventional stage is driven by obedience and punishment . This is a child's view of what is right or wrong. Examples of this thinking: “I hit my brother and I received a time-out.” “How can I avoid punishment?” “What's in it for me?”

The conventional stage is when we accept societal views on rights and wrongs. In this stage people follow rules with a good boy and nice girl orientation. An example of this thinking: “Do it for me.” This stage also includes law-and-order morality: “Do your duty.”

The post-conventional stage is more abstract: “Your right and wrong is not my right and wrong.” This stage goes beyond social norms and an individual develops his own moral compass, sticking to personal principles of what is ethical or not.

The Bronze Age Harappans had nothing to kill or die for and no religion.

Even when we know an apology is deserved, we may still feel reluctant to offer one. Research tells us why we might feel threatened.

Researchers discover how caregivers of community cats experience emotional connections similar to pet owners and why their bond is often ignored.

How consequences shape our sense of fairness and justice in unexpected ways.

How appearance anxiety is affecting the mental health of young women and girls.

Aromas and flavors switch on a neural wayback machine that accesses deep recollection.

Spite often drives punishment. The problem, researchers find, is that it's not always worth the benefit; it often leads us into excessive self-sacrifice.

Your biggest vulnerability to bullying is your active healthy conscience. Here's how to maintain it without being bullied by shameless moralizing scolds.

The Alabama ruling has sent shockwaves throughout the infertility community. During times of uncertainty, prioritize your mental health and assemble a toolkit of coping strategies.

The revival of Existential Therapy is imperative today; the crises we face are emotional, relational, and spiritual.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Hume’s Moral Philosophy

Hume’s position in ethics, which is based on his empiricist theory of the mind , is best known for asserting four theses: (1) Reason alone cannot be a motive to the will, but rather is the “slave of the passions” (see Section 3 ) (2) Moral distinctions are not derived from reason (see Section 4 ). (3) Moral distinctions are derived from the moral sentiments: feelings of approval (esteem, praise) and disapproval (blame) felt by spectators who contemplate a character trait or action (see Section 7 ). (4) While some virtues and vices are natural (see Section 13 ), others, including justice, are artificial (see Section 9 ). There is heated debate about what Hume intends by each of these theses and how he argues for them. He articulates and defends them within the broader context of his metaethics and his ethic of virtue and vice.

Hume’s main ethical writings are Book 3 of his Treatise of Human Nature , “Of Morals” (which builds on Book 2, “Of the Passions”), his Enquiry concerning the Principles of Morals , and some of his Essays . In part the moral Enquiry simply recasts central ideas from the moral part of the Treatise in a more accessible style; but there are important differences. The ethical positions and arguments of the Treatise are set out below, noting where the moral Enquiry agrees; differences between the Enquiry and the Treatise are discussed afterwards.

1. Issues from Hume’s Predecessors

2. the passions and the will, 3. the influencing motives of the will, 4. ethical anti-rationalism.

- 5. Is and Ought

6. The Nature of Moral Judgment

7. sympathy, and the nature and origin of the moral sentiments, 8. the common point of view, 9. artificial and natural virtues, 10.1 the circle, 10.2 the origin of material honesty, 10.3 the motive of honest actions, 11. fidelity to promises, 12. allegiance to government, 13. the natural virtues, 14. differences between the treatise and the moral enquiry, other internet resources, related entries.

Hume inherits from his predecessors several controversies about ethics and political philosophy.

One is a question of moral epistemology: how do human beings become aware of, or acquire knowledge or belief about, moral good and evil, right and wrong, duty and obligation? Ethical theorists and theologians of the day held, variously, that moral good and evil are discovered: (a) by reason in some of its uses (Hobbes, Locke, Clarke), (b) by divine revelation (Filmer), (c) by conscience or reflection on one’s (other) impulses (Butler), or (d) by a moral sense: an emotional responsiveness manifesting itself in approval or disapproval (Shaftesbury, Hutcheson). Hume sides with the moral sense theorists: we gain awareness of moral good and evil by experiencing the pleasure of approval and the uneasiness of disapproval when we contemplate a character trait or action from an imaginatively sensitive and unbiased point of view. Hume maintains against the rationalists that, although reason is needed to discover the facts of any concrete situation and the general social impact of a trait of character or a practice over time, reason alone is insufficient to yield a judgment that something is virtuous or vicious. In the last analysis, the facts as known must trigger a response by sentiment or “taste.”

A related but more metaphysical controversy would be stated thus today: what is the source or foundation of moral norms? In Hume’s day this is the question what is the ground of moral obligation (as distinct from what is the faculty for acquiring moral knowledge or belief). Moral rationalists of the period such as Clarke (and in some moods, Hobbes and Locke) argue that moral standards or principles are requirements of reason — that is, that the very rationality of right actions is the ground of our obligation to perform them. Divine voluntarists of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries such as Samuel Pufendorf claim that moral obligation or requirement, if not every sort of moral standard, is the product of God’s will. The moral sense theorists (Shaftesbury and Hutcheson) and Butler see all requirements to pursue goodness and avoid evil as consequent upon human nature, which is so structured that a particular feature of our consciousness (whether moral sense or conscience) evaluates the rest. Hume sides with the moral sense theorists on this question: it is because we are the kinds of creatures we are, with the dispositions we have for pain and pleasure, the kinds of familial and friendly interdependence that make up our life together, and our approvals and disapprovals of these, that we are bound by moral requirements at all.

Closely connected with the issue of the foundations of moral norms is the question whether moral requirements are natural or conventional. Hobbes and Mandeville see them as conventional, and Shaftesbury, Hutcheson, Locke, and others see them as natural. Hume mocks Mandeville’s contention that the very concepts of vice and virtue are foisted on us by scheming politicians trying to manage us more easily. If there were nothing in our experience and no sentiments in our minds to produce the concept of virtue, Hume says, no lavish praise of heroes could generate it. So to a degree moral requirements have a natural origin. Nonetheless,Hume thinks natural impulses of humanity and dispositions to approve cannot entirely account for our virtue of justice; a correct analysis of that virtue reveals that mankind, an “inventive species,” has cooperatively constructed rules of property and promise. Thus he takes an intermediate position: some virtues are natural, and some are the products of convention.

Linked with these meta-ethical controversies is the dilemma of understanding the ethical life either as the “ancients” do, in terms of virtues and vices of character, or as the “moderns” do, primarily in terms of principles of duty or natural law. While even so law-oriented a thinker as Hobbes has a good deal to say about virtue, the ethical writers of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries predominantly favor a rule- or law-governed understanding of morals, giving priority to laws of nature or principles of duty. The chief exception here is the moral sense school, which advocates an analysis of the moral life more like that of the Greek and Hellenistic thinkers, in terms of settled traits of character — although they too find a place for principles in their ethics. Hume explicitly favors an ethic of character along “ancient” lines. Yet he insists on a role for rules of duty within the domain of what he calls the artificial virtues.

Hume’s predecessors famously took opposing positions on whether human nature was essentially selfish or benevolent, some arguing that man was so dominated by self-interested motives that for moral requirements to govern us at all they must serve our interests in some way, and others arguing that uncorrupted human beings naturally care about the weal and woe of others and here morality gets its hold. Hume roundly criticizes Hobbes for his insistence on psychological egoism or something close to it, and for his dismal, violent picture of a state of nature. Yet Hume resists the view of Hutcheson that all moral principles can be reduced to our benevolence, in part because he doubts that benevolence can sufficiently overcome our perfectly normal acquisitiveness. According to Hume’s observation, we are both selfish and humane. We possess greed, and also “limited generosity” — dispositions to kindness and liberality which are more powerfully directed toward kin and friends and less aroused by strangers. While for Hume the condition of humankind in the absence of organized society is not a war of all against all, neither is it the law-governed and highly cooperative domain imagined by Locke. It is a hypothetical condition in which we would care for our friends and cooperate with them, but in which self-interest and preference for friends over strangers would make any wider cooperation impossible. Hume’s empirically-based thesis that we are fundamentally loving, parochial, and also selfish creatures underlies his political philosophy.

In the realm of politics, Hume again takes up an intermediate position. He objects both to the doctrine that a subject must passively obey his government no matter how tyrannical it is and to the Lockean thesis that citizens have a natural right to revolution whenever their rulers violate their contractual commitments to the people. He famously criticizes the notion that all political duties arise from an implicit contract that binds later generations who were not party to the original explicit agreement. Hume maintains that the duty to obey one’s government has an independent origin that parallels that of promissory obligation: both are invented to enable people to live together successfully. On his view, human beings can create a society without government, ordered by conventional rules of ownership, transfer of property by consent, and promise-keeping. We superimpose government on such a pre-civil society when it grows large and prosperous; only then do we need to use political power to enforce these rules of justice in order to preserve social cooperation. So the duty of allegiance to government, far from depending on the duty to fulfill promises, provides needed assurance that promises of all sorts will be kept. The duty to submit to our rulers comes into being because reliable submission is necessary to preserve order. Particular governments are legitimate because of their usefulness in preserving society, not because those who wield power were chosen by God or received promises of obedience from the people. In a long-established civil society, whatever ruler or type of government happens to be in place and successfully maintaining order and justice is legitimate, and is owed allegiance. However, there is some legitimate recourse for victims of tyranny: the people may rightly overthrow any government that is so oppressive as not to provide the benefits (peace and security from injustice) for which governments are formed. In his political essays Hume certainly advocates the sort of constitution that protects the people’s liberties, but he justifies it not based on individual natural rights or contractual obligations but based on the greater long-range good of society.

According to Hume’s theory of the mind, the passions (what we today would call emotions, feelings, and desires) are impressions rather than ideas (original, vivid and lively perceptions that are not copied from other perceptions). The direct passions, which include desire, aversion, hope, fear, grief, and joy, are those that “arise immediately from good or evil, from pain or pleasure” that we experience or think about in prospect (T 2.1.1.4, T 2.3.9.2); however he also groups with them some instincts of unknown origin, such as the bodily appetites and the desires that good come to those we love and harm to those we hate, which do not proceed from pain and pleasure but produce them (T 2.3.9.7). The indirect passions, primarily pride, humility (shame), love and hatred, are generated in a more complex way, but still one involving either the thought or experience of pain or pleasure. Intentional actions are caused by the direct passions (including the instincts). Of the indirect passions Hume says that pride, humility, love and hatred do not directly cause action; it is not clear whether he thinks this true of all the indirect passions.

Hume is traditionally regarded as a compatibilist about freedom and determinism, because in his discussion in the Enquiry concerning Human Understanding he argues that if we understand the doctrines of liberty and necessity properly, all mankind consistently believe both that human actions are the products of causal necessity and that they are free. In the Treatise , however, he explicitly repudiates the doctrine of liberty as “absurd... in one sense, and unintelligible in any other” (T 2.3.2.1). The two treatments, however, surprisingly enough, are entirely consistent. Hume construes causal necessity to mean the same as causal connection (or rather, intelligible causal connection), as he himself analyzes this notion in his own theory of causation: either the “constant union and conjunction of like objects,” or that together with “the inference of the mind from the one to the other” (ibid.). In both works he argues that just as we discover necessity (in this sense) to hold between the movements of material bodies, we discover just as much necessity to hold between human motives, character traits, and circumstances of action, on the one hand, and human behavior on the other. He says in the Treatise that the liberty of indifference is the negation of necessity in this sense; this is the notion of liberty that he there labels absurd, and identifies with chance or randomness (which can be no real power in nature) both in the Treatise and the first (epistemological) Enquiry . Human actions are not free in this sense. However, Hume allows in the Treatise that they are sometimes free in the sense of ‘liberty’ which is opposed to violence or constraint. This is the sense on which Hume focuses in EcHU: “ a power of acting or not acting, according to the determinations of the will; ” which everyone has “who is not a prisoner and in chains” (EcHU 8.1.23, Hume’s emphasis). It is this that is entirely compatible with necessity in Hume’s sense. So the positions in the two works are the same, although the polemical emphasis is so different — iconoclastic toward the libertarian view in the Treatise , and conciliatory toward “all mankind” in the first Enquiry .

Hume argues, as well, that the causal necessity of human actions is not only compatible with moral responsibility but requisite to it. To hold an agent morally responsible for a bad action, it is not enough that the action be morally reprehensible; we must impute the badness of the fleeting act to the enduring agent. Not all harmful or forbidden actions incur blame for the agent; those done by accident, for example, do not. It is only when, and because, the action’s cause is some enduring passion or trait of character in the agent that she is to blame for it.

According to Hume, intentional actions are the immediate product of passions, in particular the direct passions, including the instincts. He does not appear to allow that any other sort of mental state could, on its own, give rise to an intentional action except by producing a passion, though he does not argue for this. The motivating passions, in their turn, are produced in the mind by specific causes, as we see early in the Treatise where he first explains the distinction between impressions of sensation and impressions of reflection:

An impression first strikes upon the senses, and makes us perceive heat or cold, thirst or hunger, pleasure or pain, of some kind or other. Of this impression there is a copy taken by the mind, which remains after the impression ceases; and this we call an idea. This idea of pleasure or pain, when it returns upon the soul, produces the new impressions of desire and aversion, hope and fear, which may properly be called impressions of reflection, because derived from it. (T 1.1.2.2)

Thus ideas of pleasure or pain are the causes of these motivating passions. Not just any ideas of pleasure or pain give rise to motivating passions, however, but only ideas of those pleasures or pains we believe exist or will exist (T 1.3.10.3). More generally, the motivating passions of desire and aversion, hope and fear, joy and grief, and a few others are impressions produced by the occurrence in the mind either of a feeling of pleasure or pain, whether physical or psychological, or of a believed idea of pleasure or pain to come (T 2.1.1.4, T 2.3.9.2). These passions, together with the instincts (hunger, lust, and so on), are all the motivating passions that Hume discusses.

The will, Hume claims, is an immediate effect of pain or pleasure (T 2.3.1.2) and “exerts itself” when either pleasure or the absence of pain can be attained by any action of the mind or body (T 2.3.9.7). The will, however, is merely that impression we feel when we knowingly give rise to an action (T 2.3.1.2); so while Hume is not explicit (and perhaps not consistent) on this matter, he seems not to regard the will as itself a (separate) cause of action. The causes of action he describes are those he has already identified: the instincts and the other direct passions.

Hume famously sets himself in opposition to most moral philosophers, ancient and modern, who talk of the combat of passion and reason, and who urge human beings to regulate their actions by reason and to grant it dominion over their contrary passions. He claims to prove that “reason alone can never be a motive to any action of the will,” and that reason alone “can never oppose passion in the direction of the will” (T 413). His view is not, of course, that reason plays no role in the generation of action; he grants that reason provides information, in particular about means to our ends, which makes a difference to the direction of the will. His thesis is that reason alone cannot move us to action; the impulse to act itself must come from passion. The doctrine that reason alone is merely the “slave of the passions,” i.e., that reason pursues knowledge of abstract and causal relations solely in order to achieve passions’ goals and provides no impulse of its own, is defended in the Treatise , but not in the second Enquiry , although in the latter he briefly asserts the doctrine without argument. Hume gives three arguments in the Treatise for the motivational “inertia” of reason alone.

The first is a largely empirical argument based on the two rational functions of the understanding. The understanding discovers the abstract relations of ideas by demonstration (a process of comparing ideas and finding congruencies and incongruencies); and it also discovers the causal (and other probabilistic) relations of objects that are revealed in experience. Demonstrative reasoning is never the cause of any action by itself: it deals in ideas rather than realities, and we only find it useful in action when we have some purpose in view and intend to use its discoveries to inform our inferences about (and so enable us to manipulate) causes and effects. Probable or cause-and-effect reasoning does play a role in deciding what to do, but we see that it only functions as an auxiliary, and not on its own. When we anticipate pain or pleasure from some source, we feel aversion or propensity to that object and “are carry’d to avoid or embrace what will give us” the pain or pleasure (T 2.3.3.3). Our aversion or propensity makes us seek the causes of the expected source of pain or pleasure, and we use causal reasoning to discover what they are. Once we do, our impulse naturally extends itself to those causes, and we act to avoid or embrace them. Plainly the impulse to act does not arise from the reasoning but is only directed by it. “’Tis from the prospect of pain or pleasure that the aversion or propensity arises...” (ibid.). Probable reasoning is merely the discovering of causal connections, and knowledge that A causes B never concerns us if we are indifferent to A and to B. Thus, neither demonstrative nor probable reasoning alone causes action.

The second argument is a corollary of the first. It takes as a premise the conclusion just reached, that reason alone cannot produce an impulse to act. Given that, can reason prevent action or resist passion in controlling the will? To stop a volition or retard the impulse of an existing passion would require a contrary impulse. If reason alone could give rise to such a contrary impulse, it would have an original influence on the will (a capacity to cause intentional action, when unopposed); which, according to the previous argument, it lacks. Therefore reason alone cannot resist any impulse to act. Therefore, what offers resistance to our passions cannot be reason of itself. Hume later proposes that when we restrain imprudent or immoral impulses, the contrary impulse comes also from passion, but often from a passion so “calm” that we confuse it with reason.

The third or Representation argument is different in kind. Hume offers it initially only to show that a passion cannot be opposed by or be contradictory to “truth and reason”; later (T 3.1.1.9), he repeats and expands it to argue that volitions and actions as well cannot be so. One might suppose he means to give another argument to show that reason alone cannot provide a force to resist passion. Yet the Representation Argument is not empirical, and does not talk of forces or impulses. Passions (and volitions and actions), Hume says, do not refer to other entities; they are “original existence[s],” (T 2.3.3.5), “original facts and realities” (T3.1.1.9), not mental representations of other things. Since Hume here understands representation in terms of copying, he says a passion has no “representative quality, which renders it a copy of any other existence or modification” (T 2.3.3.5). Contradiction to truth and reason, however, consists in “the disagreement of ideas, consider’d as copies, with those objects, which they represent” (ibid.). Therefore, a passion (or volition or action), not having this feature, cannot be opposed by truth and reason. The argument allegedly proves two points: first, that actions cannot be reasonable or unreasonable; second, that “reason cannot immediately prevent or produce any action by contradicting or approving of it” (T3.1.1.10). The point here is not merely the earlier, empirical observation that the rational activity of the understanding does not generate an impulse in the absence of an expectation of pain or pleasure. The main point is that, because passions, volitions, and actions have no content suitable for assessment by reason, reason cannot assess prospective motives or actions as rational or irrational; and therefore reason cannot, by so assessing them, create or obstruct them. By contrast, reason can assess a potential opinion as rational or irrational; and by endorsing the opinion, reason will (that is, we will) adopt it, while by contradicting the opinion, reason will destroy our credence in it. The Representation Argument, then, makes a point a priori about the relevance of the functions of the understanding to the generation of actions. Interpreters disagree about exactly how to parse this argument, whether it is sound, and its importance to Hume’s project.

Hume allows that, speaking imprecisely, we often say a passion is unreasonable because it arises in response to a mistaken judgment or opinion, either that something (a source of pleasure or uneasiness) exists, or that it may be obtained or avoided by a certain means. In just these two cases a passion may be called unreasonable, but strictly speaking even here it is not the passion but the judgment that is so. Once we correct the mistaken judgment, “our passions yield to our reason without any opposition,” so there is still no combat of passion and reason (T 2.3.3.7). And there is no other instance of passion contrary to reason. Hume famously declaims, “’Tis not contrary to reason to prefer the destruction of the whole world to the scratching of my finger. ‘Tis not contrary to reason for me to chuse my total ruin, to prevent the least uneasiness of an Indian or person wholly unknown to me. ‘Tis as little contrary to reason to prefer even my own acknowledg’d lesser good to my greater, and have a more ardent affection for the former than for the latter.” (2.3.3.6)

Interpreters disagree as to whether Hume is an instrumentalist or a skeptic about practical reason. Either way, Hume denies that reason can evaluate the ends people set themselves; only passions can select ends, and reason cannot evaluate passions. Instrumentalists understand the claim that reason is the slave of the passions to allow that reason not only discovers the causally efficacious means to our ends (a task of theoretical causal reasoning) but also requires us to take them. If Hume regards the failure to take the known means to one’s end as contrary to reason, then on Hume’s view reason has a genuinely practical aspect: it can classify some actions as unreasonable. Skeptical interpreters read Hume, instead, as denying that reason imposes any requirements on action, even the requirement to take the known, available means to one’s end. They point to the list of extreme actions that are not contrary to reason (such as preferring one’s own lesser good to one’s greater), and to the Representation Argument, which denies that any passions, volitions, or actions are of such a nature as to be contrary to reason. Hume never says explicitly that failing to take the known means to one’s end is either contrary to reason or not contrary to reason (it is not one of the extreme cases in his list). The classificatory point in the Representation Argument favors the reading of Hume as a skeptic about practical reason; but that argument is absent from the moral Enquiry .

Hume claims that moral distinctions are not derived from reason but rather from sentiment. His rejection of ethical rationalism is at least two-fold. Moral rationalists tend to say, first, that moral properties are discovered by reason, and also that what is morally good is in accord with reason (even that goodness consists in reasonableness) and what is morally evil is unreasonable. Hume rejects both theses. Some of his arguments are directed to one and some to the other thesis, and in places it is unclear which he means to attack.

In the Treatise he argues against the epistemic thesis (that we discover good and evil by reasoning) by showing that neither demonstrative nor probable/causal reasoning has vice and virtue as its proper objects. Demonstrative reasoning discovers relations of ideas, and vice and virtue are not identical with any of the four philosophical relations (resemblance, contrariety, degrees in quality, or proportions in quantity and number) whose presence can be demonstrated. Nor could they be identical with any other abstract relation; for such relations can also obtain between items such as trees that are incapable of moral good or evil. Furthermore, were moral vice and virtue discerned by demonstrative reasoning, such reasoning would reveal their inherent power to produce motives in all who discern them; but no causal connections can be discovered a priori . Causal reasoning, by contrast, does infer matters of fact pertaining to actions, in particular their causes and effects; but the vice of an action (its wickedness) is not found in its causes or effects, but is only apparent when we consult the sentiments of the observer. Therefore moral good and evil are not discovered by reason alone.

Hume also attempts in the Treatise to establish the other anti-rationalist thesis, that virtue is not the same as reasonableness and vice is not contrary to reason. He gives two arguments for this. The first, very short, argument he claims follows directly from the Representation Argument, whose conclusion was that passions, volitions, and actions can be neither reasonable nor unreasonable. Actions, he observes, can be laudable or blamable. Since actions cannot be reasonable or against reason, it follows that “[l]audable and blameable are not the same with reasonable or unreasonable” (T 458). The properties are not identical.

The second and more famous argument makes use of the conclusion defended earlier that reason alone cannot move us to act. As we have seen, reason alone “can never immediately prevent or produce any action by contradicting or approving of it” (T 458). Morality — this argument goes on — influences our passions and actions: we are often impelled to or deterred from action by our opinions of obligation or injustice. Therefore morals cannot be derived from reason alone. This argument is first introduced as showing it impossible “from reason alone... to distinguish betwixt moral good and evil” (T 457) — that is, it is billed as establishing the epistemic thesis. But Hume also says that, like the little direct argument above, it proves that “actions do not derive their merit from a conformity to reason, nor their blame from a contrariety to it” (T458): it is not the reasonableness of an action that makes it good, or its unreasonableness that makes it evil.

This argument about motives concludes that moral judgments or evaluations are not the products of reason alone. From this many draw the sweeping conclusion that for Hume moral evaluations are not beliefs or opinions of any kind, but lack all cognitive content. That is, they take the argument to show that Hume holds a non-propositional view of moral evaluations — and indeed, given his sentimentalism, that he is an emotivist: one who holds that moral judgments are meaningless ventings of emotion that can be neither true nor false. Such a reading should be met with caution, however. For Hume, to say that something is not a product of reason alone is not equivalent to saying it is not a truth-evaluable judgment or belief. Hume does not consider all our (propositional) beliefs and opinions to be products of reason; some arise directly from sense perception, for example, and some from sympathy. Also, perhaps there are (propositional) beliefs we acquire via probable reasoning but not by such reasoning alone . One possible example is the belief that some object is a cause of pleasure, a belief that depends upon prior impressions as well as probable reasoning.

Another concern about the famous argument about motives is how it could be sound. In order for it to yield its conclusion, it seems that its premise that morality (or a moral judgment) influences the will must be construed to say that moral evaluations alone move us to action, without the help of some (further) passion. This is a controversial claim and not one for which Hume offers any support. The premise that reason alone cannot influence action is also difficult to interpret. It would seem, given his prior arguments for this claim (e.g. that the mere discovery of a causal relation does not produce an impulse to act), that Hume means by it not only that the faculty of reason or the activity of reasoning alone cannot move us, but also that the conclusions of such activity alone (such as recognition of a relation of ideas or belief in a causal connection) cannot produce a motive. Yet it is hard to see how Hume, given his theory of causation, can argue that no mental item of a certain type (such as a causal belief) can possibly cause motivating passion or action. Such a claim could not be supported a priori . And in Treatise 1.3.10, “Of the influence of belief,” he seems to assert very plainly that some causal beliefs do cause motivating passions, specifically beliefs about pleasure and pain in prospect. It is possible that Hume only means to say, in the premise that reason alone cannot influence action, that reasoning processes cannot generate actions as their logical conclusions; but that would introduce an equivocation, since he surely does not mean to say, in the other premise, that moral evaluations generate actions as their logical conclusions. The transition from premises to conclusion also seems to rely on a principle of transitivity (If A alone cannot produce X and B produces X, then A alone cannot produce B), which is doubtful but receives no defense.

Commentators have proposed various interpretations to avoid these difficulties. One approach is to construe ‘reason’ as the name of a process or activity, the comparing of ideas (reasoning), and to construe ‘morals’ as Hume uses it in this argument to mean the activity of moral discrimination (making a moral distinction). If we understand the terms this way, the argument can be read not as showing that the faculty of reason (or the beliefs it generates) cannot cause us to make moral judgments, but rather as showing that the reasoning process (comparing ideas) is distinct from the process of moral discrimination. This interpretation does not rely on an assumption about the transitivity of causation and is consistent with Hume’s theory of causation.

5. Is and ought

Hume famously closes the section of the Treatise that argues against moral rationalism by observing that other systems of moral philosophy, proceeding in the ordinary way of reasoning, at some point make an unremarked transition from premises whose parts are linked only by “is” to conclusions whose parts are linked by “ought” (expressing a new relation) — a deduction that seems to Hume “altogether inconceivable” (T3.1.1.27). Attention to this transition would “subvert all the vulgar systems of morality, and let us see, that the distinction of vice and virtue is not founded merely on the relations of objects, nor is perceiv’d by reason” (ibid.).

Few passages in Hume’s work have generated more interpretive controversy.

According to the dominant twentieth-century interpretation, Hume says here that no ought-judgment may be correctly inferred from a set of premises expressed only in terms of ‘is,’ and the vulgar systems of morality commit this logical fallacy. This is usually thought to mean something much more general: that no ethical or indeed evaluative conclusion whatsoever may be validly inferred from any set of purely factual premises. A number of present-day philosophers, including R. M. Hare, endorse this putative thesis of logic, calling it “Hume’s Law.” (As Francis Snare observes, on this reading Hume must simply assume that no purely factual propositions are themselves evaluative, as he does not argue for this.) Some interpreters think Hume commits himself here to a non-propositional or noncognitivist view of moral judgment — the view that moral judgments do not state facts and are not truth-evaluable. (If Hume has already used the famous argument about the motivational influence of morals to establish noncognitivism, then the is/ought paragraph may merely draw out a trivial consequence of it. If moral evaluations are merely expressions of feeling without propositional content, then of course they cannot be inferred from any propositional premises.) Some see the paragraph as denying ethical realism, excluding values from the domain of facts.

Other interpreters — the more cognitivist ones — see the paragraph about ‘is’ and ‘ought’ as doing none of the above. Some read it as simply providing further support for Hume’s extensive argument that moral properties are not discernible by demonstrative reason, leaving open whether ethical evaluations may be conclusions of cogent probable arguments. Others interpret it as making a point about the original discovery of virtue and vice, which must involve the use of sentiment. On this view, one cannot make the initial discovery of moral properties by inference from nonmoral premises using reason alone; rather, one requires some input from sentiment. It is not simply by reasoning from the abstract and causal relations one has discovered that one comes to have the ideas of virtue and vice; one must respond to such information with feelings of approval and disapproval. Note that on this reading it is compatible with the is/ought paragraph that once a person has the moral concepts as the result of prior experience of the moral sentiments, he or she may reach some particular moral conclusions by inference from causal, factual premises (stated in terms of ‘is’) about the effects of character traits on the sentiments of observers. They point out that Hume himself makes such inferences frequently in his writings.

On Hume’s view, what is a moral evaluation? Four main interpretations have significant textual support. First, as we have seen, the nonpropositional view says that for Hume a moral evaluation does not express any proposition or state any fact; either it gives vent to a feeling, or it is itself a feeling (Flew, Blackburn, Snare, Bricke). (A more refined form of this interpretation allows that moral evaluations have some propositional content, but claims that for Hume their essential feature, as evaluations, is non-propositional.) The subjective description view, by contrast, says that for Hume moral evaluations describe the feelings of the spectator, or the feelings a spectator would have were she to contemplate the trait or action from the common point of view. Often grouped with the latter view is the third, dispositional interpretation, which understands moral evaluations as factual judgments to the effect that the evaluated trait or action is so constituted as to cause feelings of approval or disapproval in a (suitably characterized) spectator (Mackie, in one of his proposals). On the dispositional view, in saying some trait is good we attribute to the trait the dispositional property of being such as to elicit approval. A fourth interpretation distinguishes two psychological states that might be called a moral evaluation: an occurrent feeling of approval or disapproval (which is not truth-apt), and a moral belief or judgment that is propositional. Versions of this fourth interpretation differ in what they take to be the content of that latter mental state. One version says that the moral judgments, as distinct from the moral feelings, are factual judgments about the moral sentiments (Capaldi). A distinct version, the moral sensing view, treats the moral beliefs as ideas copied from the impressions of approval or disapproval that represent a trait of character or an action as having whatever quality it is that one experiences in feeling the moral sentiment (Cohon). This last view emphasizes Hume’s claim that moral good and evil are like heat, cold, and colors as understood in “modern philosophy,” which are experienced directly by sensation, but about which we form beliefs.

Our moral evaluations of persons and their character traits, on Hume’s positive view, arise from our sentiments. The virtues and vices are those traits the disinterested contemplation of which produces approval and disapproval, respectively, in whoever contemplates the trait, whether the trait’s possessor or another. These moral sentiments are emotions (in the present-day sense of that term) with a unique phenomenological quality, and also with a special set of causes. They are caused by contemplating the person or action to be evaluated without regard to our self-interest, and from a common or general perspective that compensates for certain likely distortions in the observer’s sympathies, as explained in Section 8 . Approval (approbation) is a pleasure, and disapproval (disapprobation) a pain or uneasiness. The moral sentiments are typically calm rather than violent, although they can be intensified by our awareness of the moral responses of others. They are types of pleasure and uneasiness that are associated with the passions of pride and humility, love and hatred: when we feel moral approval of another we tend to love or esteem her, and when we approve a trait of our own we are proud of it. Some interpreters analyze the moral sentiments as themselves forms of these four passions; others argue that Hume’s moral sentiments tend to cause the latter passions. We distinguish which traits are virtuous and which are vicious by means of our feelings of approval and disapproval toward the traits; our approval of actions is derived from approval of the traits we suppose to have given rise to them. We can determine, by observing the various sorts of traits toward which we feel approval, that every such trait — every virtue — has at least one of the following four characteristics: it is either immediately agreeable to the person who has it or to others, or it is useful (advantageous over the longer term) to its possessor or to others. Vices prove to have the parallel features: they are either immediately disagreeable or disadvantageous either to the person who has them or to others. These are not definitions of ‘virtue’ and ‘vice’ but empirical generalizations about the traits as first identified by their effects on the moral sentiments.