An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

A comparison of characteristics between food delivery riders with and without traffic crash experience during delivery in Malaysia

Rusdi rusli.

a School of Civil Engineering, College of Engineering, Universiti Teknologi MARA, 40450 Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia

Mazlina Zaira Mohammad

Noor azreena kamaluddin, harun bakar.

b Prevention, Medical and Rehabilitation Division, Social Security Organization (SOCSO), Ministry of Human Resources, Menara PERKESO, 281, Jalan Ampang, 50538 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Mohd Hafzi Md Isa

The rapid development of e-commerce and the spread of the COVID-19 virus created many new jobs opportunity including food delivery riders known as P-Hailing riders. The number of food delivery riders has increased drastically, especially in Malaysia. Consequently, the number of food delivery riders involved in traffic crashes also increased. This study aimed to examine the characteristics of food delivery riders involved in traffic crashes during delivery and to compare with the characteristics of food delivery riders without any traffic crash history. This paper explores and compares general characteristics, previous experience of working and receiving traffic tickets, and knowledge of road safety. Due to unavailable official records about the number of active food delivery riders in Malaysia, this study focuses on riders who registered as members of the Malaysian P-Hailing Association, PENGHANTAR. A total of 225 food delivery riders participated in the online survey conducted through Google Form. Categorical data analysis techniques were used to examine the different characteristics of food delivery riders with and without traffic crash experiences. Results show that the odds ratio of young and full-time riders are respectively about 2.05 times and 1.79 times higher than being involved in traffic crashes. Other factors that increase the odds of being involved in traffic crashes include having more than two years of experience in delivery, an average distance travelled of>100 km a day, working previously in the food and grocery sector, and without working experience. The findings from this study will help related agencies to design and develop awareness programs targeting this group of riders.

1. Introduction

The rapid development of electronic commerce (e-commerce) has changed traditional business models around the world. In 2016, e-commerce generated approximately US$400 billion in the United States, EUR 601 billion in Europe, and US$11 billion in South Asia ( Nair, 2017 ). In Malaysia, there have been upward trends in the e-commerce industry in recent years. For example, in 2017, the e-commerce business value was US$3.6 billion and rose to US$8 billion in 2019 ( Morgan, 2020 ). Among the biggest growth areas in the e-commerce industry is food delivery services. It is projected that by the year 2022, the food delivery business will grow to annual revenue of US$956 million, which is one of the fastest-growing sectors in the food market ( Milo, 2018 ). In early 2020, the world was shocked by the pandemic COVID-19. The Malaysian government has introduced a different approach to combating this pandemic to reduce the number of infected people. For example, during the Movement Control Order (MCO), customers were not allowed to dine in at the restaurants, while during the Conditional Movement Control Order (CMCO) and Recovery Movement Control Order (RMCO), restaurants needed to reduce their seating capacity to maintain social distancing between tables. As an alternative, customers and restaurants are moving to online and delivery services to buy or sell food. Many companies offer food delivery services in Malaysia, including FoodPanda, DeliverEat, Ubar Eats, Grab Food, Lalamove, Honestbee, and Running Man Delivery. These companies have appointed local riders to deliver food and parcels. For example, Foodpanda has 30,000 riders working for them around the country ( Murugiah, 2021 ). This scenario created a new job opportunity, and most were food delivery riders, also known as P-Hailing riders in Malaysia. To support the development of the food delivery business, it is important to understand the risk factors associated with this job.

The trend of traffic crashes involving food delivery riders has also increased recently worldwide. For example, there are 76 fatal crashes in Shanghai, China involving delivery riders in the first 6 months of 2017 and nearly-one delivery rider died from a traffic crash every 2.5 days ( Daily, 2017 ). In Malaysia, although there is not a specific breakdown for food delivery riders, 66 % of the people killed in traffic crashes in Malaysia are motorcyclists ( Dave, 2020 ). Based on three months of crash statistics recorded by the Malaysian Institute of Road Safety Research (MIROS), there are 4 fatalities, 55 serious injuries, and 73 slight injuries were reported from two food delivery services companies, Foodpanda and GrabFood ( Tamrin, 2020 ). The Social Security Organisation (SOCSO) reported there were>150 road traffic crashes involving food delivery riders that happens between March and June 2020 ( Bernama, 2021 ). Additionally, there is often news about crashes involving this group of riders. To avoid the increasing number of fatalities in Malaysia, this issue must be well understood before a targeted countermeasure can be proposed. Intensive study is the only way to understand this issue. However, the research related to the safety of food delivery riders is very limited in Malaysia.

Previous studies identified many risk factors associated with traffic crashes involving food delivery riders. A study conducted in the Republic of Korea analysed the data of motorcycle crashes of 1,310 food delivery workers that have been approved as on-duty industrial crashes since 2015 ( Byun et al., 2017 ). They found that 99.2 % of crash-involved food delivery riders were males and 82.6 % had less than six months of work experience. Another study also conducted in the Republic of Korea analysed the traffic crashes involving 671 motorcycle curriers and found 50.6 % were aged less than 40 years, 49.2 % ran a small business of less than five employees, and 47.2 % had work experience of less than six months ( Shin et al., 2019 ). Further study by ( Byun et al., 2020 ) about the effect of age and violations on occupational accidents among 1,317 injured motorcyclists performing food delivery in the Republic of Korea. Among injured riders, 67.4 % were temporary workers, 76.1 % worked in small companies with fewer than five employees, 58.7 % in the night time, and 51.5 % had work experience of less than one month. They also found that the violation rate decreased with age. A study in two cities in China; Shanghai, and Nanjing found less rest, higher frequency of engaging in risky riding behaviours, and completing more daily orders significantly associated to crash involvement among delivery riders ( Zheng et al., 2019 ). Tran et al. (2022) conducted a study in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam found many delivery riders adopt risky riding behaviours due to job pressure, long working hours and financial commitment. It is crucial to know the association between the characteristics of food delivery riders and traffic crash experiences before further action can be taken. However, the amount of evidence available to explain road traffic crashes involving food delivery riders is relatively scarce in Malaysia.

The economic downturn due to the pandemic of COVID-19 has led some people to lose their jobs. As an alternative, they become food delivery riders to earn a living. Food delivery riders earn money based on the number of deliveries that have been made. They will earn more money if they make more deliveries. As for food delivery, they also got pressure from customers about the duration of delivery of food ( TheSTAR, 2021 ). Many food delivery riders violate a traffic law to get a high income and avoid complaints from customers. Based on previous research, about two-thirds of the delivery riders disobeyed traffic rules and about one-third committed a serious safety violations including holding their phones in their hands while riding, running red lights, making illegal U-turns, and riding in the wrong direction ( Dave, 2020 ). Among the factors associated with traffic violation behaviours among motorcycle curriers were a small business of less than 5 employees (13.9 %), with work experience of less than 6 months (13.9 %), on cloudy or clear days (12.4 %), at an intersection (29.8 %), in the type of “crash with a vehicle” (31.2 %), or a deadly traffic crash (35.7 %) ( Shin et al., 2019 ). Papakostopoulos et al. ( Papakostopoulos and Nathanael, 2021 ) investigated the intricate interrelationship of occupational factors underlying the risky driving behaviour of food delivery riders in Athens, Greece, with a focus on two serious offenses: red-light running and helmet non-use. They discovered that common health and safety precautions had an impact on serious traffic offenses; instead, they found a relationship between young age and both offenses. However, various work circumstances such as less working experience, use of a personal vehicle on the job, and hourly payment were associated with red-light running behaviours, while intense work pace, high tip income per day, and low concern about vehicle condition were associated with helmet non-use. In Malaysia, ( Kulanthayan et al., 2012 ) conducted a study to determine the factors that influence non-standard safety helmet use by food delivery workers. They found that 55.3 % of fast-food delivery workers use non-standard helmets. A study conducted by the Malaysian Institute of Road Safety Research (MIROS) discovered 70 % of food delivery riders have broken the traffic regulations during delivery ( Supramani, 2021 ). In addition, this study also reveals that few of traffic violation including stopping within yellow box (57 %), red-light running (16 %), mobile phone use during riding (15 %), riding in opposite direction (7 %) and performing illegal U-turns (5 %). Although there is some research about food delivery riders, much more remains to be known about factors associated with crash occurrence among this group of riders.

Therefore, the objectives of this study were to examine the characteristics of food delivery riders involved in traffic crashes during delivery and to compare with the characteristics of food delivery riders without any crash experience. It should be noted that the study focus on food delivery riders only includes those who deliver food using motorcycles. Compared to other motorcycle riders, food delivery riders more frequent disobey traffic rules due to time commitment in delivery ( Dave, 2020 ). In addition, the increasing number of motorcycle riders embarked in the food delivery industry during the pandemic has raised serious concerns among the safety actors as registered number of traffic violations and crashes. Three aspects analysed in this study include general characteristics of riders, previous experience in previous jobs and receiving traffic tickets, and knowledge of road safety. The scope of this study is limited to the riders who registered with the Malaysian P-Hailing Association, PENGHANTAR. The findings from this study could provide a proper road safety awareness program targeting this group of riders. In addition, findings from this study are also necessary for researchers to further analyse the identified factors associated with food delivery riders.

2.1. Materials and data collection

A questionnaire has been developed to obtain information from food delivery riders to achieve the objectives of this study. The questionnaire consists of three sections including general characteristics (i.e., gender, age, job status, experience in delivery works, average monthly income, average daily working hours, and average daily distance travelled), previous experience (i.e., the previous job and received traffic ticket), and knowledge in road safety (i.e., frequency of motorcycle servicing, basic knowledge about safety as a food delivery rider and behaviour of holding the mobile phone while riding). In addition, the participants also need to state their experience being involved in traffic crashes during delivery.

This research has used an online survey to obtain feedback from food delivery riders. Due to unavailable official information about the numbers of active food delivery riders in Malaysia, this study used the number of members registered with the Malaysian P-Hailing Association, PENGHANTAR as a study population. Based on the record from PENGHANTAR, the number of registered members reached approximately 4,000 riders in December 2020. This study followed Hair et al. ( Hair et al., 2018 ) to determine the appropriate sample size. As the ideal sample-to-variable ratio for observational research, they suggest 15:1 to 20:1. If we use the lower ratio of 20:1, with 11 variables in this study, 220 samples or observations are necessary.. The link to the survey was distributed among the PENGHANTAR members using the official communication platform, Facebook “Persatuan Penghantar P-Hailing Malaysia”. The online survey was available for five months and was accessible from 1st December 2020 until 30th April 2021. Riders who completed the survey received a voucher worth RM10. During online surveying, about 6 % (2 4 0) of the registered food delivery riders voluntarily participated in this study which is more than the minimum sample size.

2.2. Data analysis

This study applied disaggregate-analysis techniques to examine the different characteristics of riders with and without traffic crash experiences. A series of chi-square tests in the form of contingency tables with a 5 % level of confidence was formed to compare the statistical differences between with and without crash experience across the range of explanatory variables. We also calculate the odds ratio to measure the effect of size and strength of the relationship between pairs of categorical variables. The selection of this technique is due to the capability to elucidate underlying trends and patterns. This is very important for us as the first step to comprehending the safety scenario for riders of food delivery services. This technique has been used widely in road safety research. For example, Rusli et al. (2015) applied this technique to compare the characteristics of road traffic crashes along rural mountainous roads and non-mountainous roads. Another study in the US used this technique in their data analysis to evaluate the safety edge treatment for pavement edge drop-offs on two-lane rural roads ( Lyon et al., 2018 ).

3. Results and discussion

A total of 240 riders participated in this survey. However, after the data cleaning process, the final participant is 225. Out of these, 93 riders (41 %) have been involved in traffic crashes during deliveries. This finding shows that more than one-quarter of the food delivery riders were involved in traffic crashes out of the total respondents in this study. This finding explains the increasing trend in road traffic crashes reported nationwide ( Tamrin, 2020 , Bernama, 2021 ). Furthermore, forty-one riders (18 %) reported being involved in at least one traffic crash, 25 riders (11 %) were involved in two traffic crashes, and 27 riders (12 %) claimed that they had been involved in more than three traffic crashes. Due to less feedback from the female riders (3 %), gender was dropped from the discussion list. Further discussions were held based on the differences in general characteristics, previous experience in previous jobs and receiving traffic crashes, and knowledge in road safety among delivery riders with and without traffic crash history. As mentioned before, this study will only discuss the variables with a p-value less than 0.05. P-value more than0.05 implies that no effect has been observed.

3.1. General characteristics

Table 1 represents a univariate analysis comparing the general characteristics of food delivery riders with and without traffic crash experience. The age of riders was divided into two categories: young riders ( Kulanthayan et al., 2012 ) and middle-aged riders ( Zhang et al., 2020 ). About 65 % of riders who experienced being involved in traffic crashes were young riders. Compared to middle-aged riders, young riders were slightly overrepresented involved in traffic crashes, with the corresponding odds about 2.05 times (95 %CI 0.28–0.84) higher compared to not involved in traffic crashes (p less than 0.01). This finding is in line with a study in the Republic of Korea ( Byun et al., 2020 ). They found more than half of the injured riders were young riders (less than 29 years old). They also found that 16 % of them violated traffic rules and regulations. This group of riders are inexperienced, lack proper riding skills and are risk-taker ( Haworth and Rowden, 2010 ). A study in Greece also revealed age is a critical risk factor and found young riders are the common dominators of red-light running and helmet non-use among food delivery riders ( Papakostopoulos and Nathanael, 2021 ). This group of riders has a greater attitude during riding and are more likely to engage in risky behaviours compared to older riders. The same trend was also observed among young non-food delivery riders in Malaysia ( Manan and Várhelyi, 2012 ). Fig. 1 presents the detailed distribution of riders with and without traffic crash experience across ages.

General Characteristics.

*reference category.

Percentage of Riders by Age for Riders With and Without Traffic Crash Experience.

About 66 % of riders involved in traffic crashes during delivery were full-time riders. The odds of full-time riders being involved in traffic crashes were about 79 % (95 %CI 1.04–3.10) higher than part-time riders. This finding might be due to the work environment between full-time and part-time riders. Part-time workers may perhaps have other sources of income, and they are more flexible due to their other commitments and activities ( Ashkrof et al., 2020 ). They do not need to be rushing for delivery compared to the full-time rider who depends entirely on this job as their income.

In terms of experience, about 71 % of food delivery riders involved in traffic crashes have had less than two years of experience in this job. However, the result of the odds ratio shows that riders with experience of two years and more have high odds involved in traffic crashes as much as 2.59 times (95 %CI 1.32–5.05) compared to riders with experience less than two years (p less than 0.01). Although most previous studies ( Byun et al., 2017 , Shin et al., 2019 ) found that experienced riders were less likely to cause traffic accidents, the findings of this recent study show that they were also less cautious when riding for food deliveries. Another reason that needs to be considered is the exposure factors while the increased period of working as a food delivery rider, the exposure to the crash also increases. Further research is needed to identify this contradictory finding. Fig. 2 presents the percentage of riders by delivery experience for riders with and without traffic crash experience.

Percentage of Riders by Delivery Experience for Riders With and Without Traffic Crash Experience.

Riders in the food delivery industry are mostly paid based on the number of deliveries. An increased number of deliveries will increase the income of the riders. Most of the food delivery companies in Malaysia do not have the maximum number of working hours for their riders in a day. Findings from this study reveal that about 11 % of the respondents work >12 h per day. Nevertheless, it was found that there was no significant difference in average monthly income between riders with and without crash experience (p > 0.05). This study also found daily working hours spent by food delivery riders are not statistically different between riders with and without traffic crash experience (p > 0.05). However, daily distance travelled of 200 km and more, compared to less than 200 km, increases the likelihood of being involved in traffic crashes by as much as 1.79 times (95 %CI 1.04 – 3.10) (p = 0.04). This is due to the exposure factors of riders on the road. The majority of road safety studies discovered that increasing distance travelled is positively associated with the occurrence of a crash. For example, a study among motorcycle taxis in Vietnam found high daily travel distances were associated with crash occurrences ( Nguyen-Phuoc et al., 2019 ). In Malaysia, distance travelled is among the factors identified as influencing crash occurrence among commuter workers by motorcycle ( Oxley et al., 2013 ). Fig. 3 shows the percentage of riders by average daily distance travelled for riders with and without traffic crash experience.

Percentage of Riders by Average Daily Distance Travelled for Riders with and without Traffic Crash Experience.

3.2. Previous experience in job and receiving traffic ticket

Table 2 presents the distribution of riders with and without traffic crash experience across previous job sectors and experienced received traffic tickets or fines. As mentioned before, the food delivery sector has been increasing recently due to the growth of e-commerce. This sector became more popular when the COVID-19 Pandemic spread around the world, forcing many sectors to shut down including restaurants. In this study, the previous job was categorized into seven categories based on the feedback from respondents. Among them, riders who did not have any previous working experience were overrepresented in the crash, representing about 22 % of all riders who have experience in traffic crashes. Compared to riders from the transportation sector, riders with no previous working experience were about 3.50 times (95 %CI 1.22 – 10.04) more likely to be involved traffic crashes (p = 0.02). This study used the transportation sector as a reference because it is similar to food delivery services.

Previous Job Experience and Receiving Traffic Ticket.

The government servants and the professional sector represent the second largest group of food delivery riders (19 %) followed by the food and groceries sector with about 15 %. Compared to the transportation sector, the odds of food delivery riders previously from the food and grocery sector were about 3.39 times (95 %CI 1.16 – 9.91) higher to involve in traffic crashes (p = 0.02). The explanation might be due to riders formerly from the food and grocery sectors needing to learn new skills as riders compared to their previous jobs, which were mostly involved in restaurants and shops. Other work sectors such as business, factories, government servants and professionals, and services were found to be not significantly different between riders with and without traffic crash experience (p > 0.05). Fig. 4 shows the percentage of riders by previous job for riders with and without traffic crash experience.

Percentage of Riders by Previous Job for Riders With and Without Traffic Crash Experience.

Another variable found with no significant difference between riders with and without traffic crash experience is experienced received a traffic ticket (p > 0.05). About 30 % of riders with traffic crash experience got traffic tickets due to traffic violence compared to about 21 % of riders without traffic crash experience. Nevertheless, in Brazil, drivers with a history of traffic tickets are associated with crash involvement ( Rios et al., 2020 ). According to a study conducted in Massachusetts, the United States, traffic tickets significantly reduce traffic crashes and non-fatal injuries ( Luca, 2015 ).

3.3. Knowledge in road safety

Three factors were examined to identify the relationship between knowledge of road safety and involvement in traffic crash, including the frequency of servicing motorcycles, basic knowledge about safety as food delivery riders, and mobile phone use during riding. Based on the distribution between riders with and without traffic crash experience in Table 3 , the same observation for frequency motorcycle servicing was observed. Most riders with and without traffic crash experience prefer to service their motorcycle on a daily basis with about 41 % and 42 %, respectively. The odds ratio analysis confirms that there are no significant differences between these groups (p > 0.05). Referring to the basic knowledge about safety as a food delivery rider, the same observation was also found. There is no specific course that needs to be attended by the food delivery riders when first joining this job (p > 0.05). However, 70 % of riders with crash experience and 79 % of riders without crash experience reported having basic traffic safety knowledge.

Knowledge in Road Safety.

The use of the mobile phone during riding shows the same proportion between riders with and without traffic crash experience about 25 % and 24 %, respectively. Analysis of the odds ratio shows there are no significant differences between both groups with regards to the holding mobile phone (p > 0.05). Although previous research has found that mobile phones increase the likelihood of being involved in a crash, the mobile phone is important for food delivery riders because it provides navigation to the delivery address. A study in China confirms that 96.3 % out of 315 respondents among food deliverymen used mobile phone while riding ( Zhang et al., 2020 ). There were about 21 % of all courier and take-out food delivery riders by electric bike in China using a mobile phone ( Wang et al., 2021 ). Oviedo-Trespalacios et al. (2022) found cyclists delivering food used handheld mobile phones differently depending on the time of day. The focus of this study is only on riders who hold their phones while riding. Further studies need to be conducted to confirm the use of the mobile phone (text, wayfinding, phone, and use of the application) during riding among food delivery riders.

4. Conclusion

This study applied the disaggregated-analysis technique to examine the characteristics of riders with and without traffic crash experiences. An online survey was conducted among the food delivery riders who registered as members of PENGHANTAR, the Malaysian P-Hailing Association. Based on participants feedback, several explanatory variables were tested in this study including age, job status, experience in delivery, monthly income, daily working hours, and daily delivery distance. In addition, previous working experience and history of receiving traffic tickets were also tested. Lastly, knowledge of the riders toward road safety was also tested including the frequency of motorcycle servicing, basic knowledge about the safety of food delivery, and holding mobile phones while riding.

The results show that young, full-time, experienced, and those who travel equal to or>100 km daily are more likely to be involved in road traffic crashes. Riders who previously did not work or worked in the food and grocery sector are more likely to be involved in traffic crashes. This study also confirms that the frequency of servicing motorcycles and having basic knowledge about the safety of food delivery is not significantly different between riders with and without crash experience. Interestingly, although the number of riders holding the mobile phone during riding was higher, there were no significant differences between both categories of riders (with or without crash experience).

There are some limitations to this study. First, the number of populations cannot be identified due to unavailable official records about the number of active food delivery riders in Malaysia. Food delivery riders can be categorized as freelance work and not covered under the Employment Act 1995 (Act 265) (1995) . To protect self-employed individuals, the Social Security Organisation (SOCSO) offers the Self-Employment Social Security Scheme (SKSPS) under the provisions of the Self-Employment Social Security Act 2017 (Act 789) (2017) . Alternative, a record from SOCSO could be used as a data source in future research. Second, data for this study was obtained on a self-reported online questionnaire distributed through social media to the PENGHANTAR association members only. Third, this study's focus on mobile phone usage as a whole ignores the impact of specific mobile phone uses, such as texting, calling, location-based services, and delivery apps. Future research should include these observations in order to get an in-depth understanding of the distraction of food delivery riders during riding. In addition, advanced analysis techniques such as the development of binary logistic regression should be considered in future research to examine the relevant variables discovered in this study using data from the SOCSO.

Although this study has some limitations, it does identify some basic characteristics between riders with and without crash experience as food delivery riders. Based on the findings from this study, it is important to introduce a short course for new food delivery riders to increase their understanding of safe riding, especially for those riders without working experience or who have previously worked in other sectors. In addition, regular safety campaigns should be provided to increase awareness of road safety among full-time, experienced and riders with higher daily travelled distances. ( Wang et al., 2021 ) also suggested that distribution companies create a safety campaign as one strategy to lower the risk of crashes among delivery riders in Shanghai, China. This current study also discovered a relationship between young riders and crash experiences. Implementing a demerit point system for young delivery riders or perhaps setting an age restriction should be considered, as suggested by ( Papakostopoulos and Nathanael, 2021 ). It should be noted that the respondents in this study are PENGHANTAR members and all suggestions are primarily appropriate for PENGHANTAR use. However, other relevant authorities or service providers also can consider these findings where suitable.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

- Self-Employment Social Security Act 2017 (Act 789) (2017) 2017. https://www.perkeso.gov.my/images/imej/akta_dan_peraturan/Act789-Asat1March2020.pdf

- Ashkrof P., de Almeida Correia G.H., Cats O., van Arem B. Understanding ride-sourcing drivers’ behaviour and preferences: Insights from focus groups analysis. Res. Transp. Bus Manag. 2020; 37 [ Google Scholar ]

- Bernama Socso: Over 150 accidents involving delivery riders from March to June last year. Bernama. 2021 [ Google Scholar ]

- Byun J.H., Jeong B.Y., Park M.H. Characteristics of motorcycle crashes of food delivery workers. J. Ergon. Soc. Korea. 2017; 36 (2):157–168. [ Google Scholar ]

- Byun J.H., Park M.H., Jeong B.Y. Effects of age and violations on occupational accidents among motorcyclists performing food delivery. Work. 2020; 65 (1):53–61. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Legal Daily. Frequent Accident Involvement of Delivery Rider, Traffic Management Departments Start to Take Actions. [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2021 Apr 4]. Available from: http://www.xinhuanet.com/legal/2017-09/15/c_1121666204.htm.

- Dave G. Malaysian Road Safety Institute Pushes For Better Training Of Food Delivery Riders. Voice of America (VOA) [Internet]. 2020 Sep 16; Available from: https://www.voanews.com/economy-business/malaysian-road-safety-institute-pushes-better-training-food-delivery-riders.

- Dave G. Malaysian Road Safety Institute Pushes For Better Training Of Food Delivery Riders. 2020 Sep 16; Available from: https://www.voanews.com/a/economy-business_malaysian-road-safety-institute-pushes-better-training-food-delivery-riders/6195935.html.

- Employment Act 1995 (Act 265) (1995) https://jtksm.mohr.gov.my/images/kluster-warnawarni/akta-borang/akta-peraturan/akta_kerja1955_bi.pdf

- Hair J.F., Black W.C., Babin B.J., Anderson R.E. 8th ed. Cengage Learning; United Kingdom: 2018. Multivariate Data Analysis. [ Google Scholar ]

- Haworth N, Rowden P. Challenges in improving the safety of learner motorcyclists. In: Proceedings of the 20th Canadian Multidisciplinary Road Safety Conference. Canadian Association of Road Safety Professionals; 2010. p. 1–16.

- Kulanthayan S., See L.G., Kaviyarasu Y., Afiah M.Z.N. Prevalence and determinants of non-standard motorcycle safety helmets amongst food delivery workers in Selangor and Kuala Lumpur. Injury. 2012; 43 (5):653–659. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Luca D.L. Do traffic tickets reduce motor vehicle accidents? Evidence from a natural experiment. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2015; 34 (1):85–106. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lyon C., Persaud B., Donnell E. Safety evaluation of the SafetyEdge treatment for pavement edge drop-offs on two-lane rural roads. Transp. Res. Rec. 2018; 2672 (30):1–8. [ Google Scholar ]

- M B. Demanding customers force us to break traffic rules, say riders. TheSTAR [Internet]. 2021 Mar; Available from: https://www.thestar.com.my/metro/metro-news/2021/03/23/demanding-customers-force-us-to-break-traffic-rules-say-riders.

- Manan M.M.A., Várhelyi A. Motorcycle fatalities in Malaysia. IATSS Res. 2012; 36 (1):30–39. [ Google Scholar ]

- EC Milo. The food delivery battle has just begun in Malaysia [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://www.ecinsider.my/2018/02/food-delivery-companies-malaysia.html?m=1&fbclid=IwAR2qZlY69l8B8L8iGeCUmFUKSFvt0FSO-URWa_0G-Me5JB5fbjZ9OrZZkUA.

- J.P.Morgan. 2020 E-commerce Payments Trends Report: Malaysia [Internet]. J.P. Morgan. 2020 [cited 2021 Apr 2]. Available from: https://www.jpmorgan.com/merchant-services/insights/reports/malaysia-2020#:∼:text=Malaysia’s e-commerce market is,39 percent in 2019 alone.

- Murugiah S. Big data has trimmed 50% off delivery time for foodpanda delivery riders. theedgemarkets.com [Internet]. 2021; Available from: https://www.theedgemarkets.com/article/big-data-has-trimmed-50-delivery-time-foodpanda-delivery-riders.

- Nair K.S. Impact of E-Commerce on Global Business And Opportunities–A Conceptual Study. Dubai Int. J. Adv. Eng. Manag. Res. 2017; 2 (2) [ Google Scholar ]

- Nguyen-Phuoc D.Q., Nguyen H.A., De Gruyter C., Su D.N., Nguyen V.H. Exploring the prevalence and factors associated with self-reported traffic crashes among app-based motorcycle taxis in Vietnam. Transp. Policy. 2019; 81 :68–74. [ Google Scholar ]

- Oviedo-Trespalacios Oscar, Rubie, E., & Haworth, N. Risky business: Comparing the riding behaviours of food delivery and private bicycle riders. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 2022; 177 doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2022.106820. Submitted for publication. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oxley J., Yuen J., Ravi M.D., Hoareau E., Mohammed M.A.A., Bakar H., et al. Commuter motorcycle crashes in Malaysia: An understanding of contributing factors. Ann. Adv. Automot. Med. 2013; 57 :45. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Papakostopoulos V., Nathanael D. The Complex Interrelationship of Work-Related Factors Underlying Risky Driving Behavior of Food Delivery Riders in Athens, Greece. Saf Health Work [Internet]. 2021; 12 (2):147–153. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2093791120303486 Available from. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rios P.A.A., Mota E.L.A., Ferreira L.N., Cardoso J.P., Ribeiro V.M., de Souza B.S. Factors associated with traffic accidents among drivers: findings from a population-based study. Cien Saude Colet. 2020; 25 :943–955. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rusli R., Haque M.M., King M., Voon W.S. The 2015 Australasian Road Safety Conference. Australasian College of Road Safety Inc. (ACRS); Australia: 2015. A Comparison of Road Traffic Crashes along Mountainous and Non-Mountainous Roads in Sabah, Malaysia. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shin D.S., Byun J.H., Jeong B.Y. Crashes and traffic signal violations caused by commercial motorcycle couriers. Saf Health Work. 2019; 10 (2):213–218. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Supramani S. 70% of p-hailing riders disobey traffic rules while on delivery runs: Miros. The Sun Daily. 2021 [ Google Scholar ]

- Tamrin S. Agensi keselamatan akan bincang kadar kemalangan penghantar makanan. https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/ [Internet]. 2020; Available from: https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/bahasa/2020/07/19/agensi-keselamatan-akan-bincang-kadar-kemalangan-penghantar-makanan/.

- Tran N.A.T., Nguyen H.L.A., Nguyen T.B.H., Nguyen Q.H., Huynh T.N.L., Pojani D., et al. Health and safety risks faced by delivery riders during the Covid-19 pandemic. J. Transp. Heal. 2022; 25 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang X., Chen J., Quddus M., Zhou W., Shen M. Influence of familiarity with traffic regulations on delivery riders’e-bike crashes and helmet use: Two mediator ordered logit models. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021; 159 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang Z., Neitzel R.L., Zheng W., Wang D., Xue X., Jiang G. Road safety situation of electric bike riders: A cross-sectional study in courier and take-out food delivery population. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2021; 22 (7):564–569. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhang Y., Huang Y., Wang Y., Casey T.W. Who uses a mobile phone while driving for food delivery? The role of personality, risk perception, and driving self-efficacy. J. Safety Res. 2020; 73 :69–80. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zheng Y., Ma Y., Guo L., Cheng J., Zhang Y. Crash involvement and risky riding behaviors among delivery riders in China: the role of working conditions. Transp. Res. Rec. 2019; 2673 (4):1011–1022. [ Google Scholar ]

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, online food delivery research: a systematic literature review.

International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management

ISSN : 0959-6119

Article publication date: 26 May 2022

Issue publication date: 26 July 2022

Online food delivery (OFD) has witnessed momentous consumer adoption in the past few years, and COVID-19, if anything, is only accelerating its growth. This paper captures numerous intricate issues arising from the complex relationship among the stakeholders because of the enhanced scale of the OFD business. The purpose of this paper is to highlight publication trends in OFD and identify potential future research themes.

Design/methodology/approach

The authors conducted a tri-method study – systematic literature review, bibliometric and thematic content analysis – of 43 articles on OFD published in 24 journals from 2015 to 2021 (March). The authors used VOSviewer to perform citation analysis.

Systematic literature review of the existing OFD research resulted in six potential research themes. Further, thematic content analysis synthesized and categorized the literature into four knowledge clusters, namely, (i) digital mediation in OFD, (ii) dynamic OFD operations, (iii) OFD adoption by consumers and (iv) risk and trust issues in OFD. The authors also present the emerging trends in terms of the most influential articles, authors and journals.

Practical implications

This paper captures the different facets of interactions among various OFD stakeholders and highlights the intricate issues and challenges that require immediate attention from researchers and practitioners.

Originality/value

This is one of the few studies to synthesize OFD literature that sheds light on unexplored aspects of complex relationships among OFD stakeholders through four clusters and six research themes through a conceptual framework.

- Online food delivery

- Sharing economy

- Systematic literature review

- Bibliometric analysis

- Content analysis

Acknowledgements

The authors thank three anonymous reviewers, the guest editor, and the editor-in-chief for their critical and valuable comments in developing the manuscript in stages.

Shroff, A. , Shah, B.J. and Gajjar, H. (2022), "Online food delivery research: a systematic literature review", International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management , Vol. 34 No. 8, pp. 2852-2883. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2021-1273

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2022, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

HYPOTHESIS AND THEORY article

Study on instant delivery service riders' safety and health by the effects of labour intensity in china: a mediation analysis.

- 1 School of Public Administration, Zhongnan University of Economics and Law, Wuhan, China

- 2 Chinese Academy of Labour and Social Security, Peking, China

The Instant Delivery Service (IDS) riders' overwork by “self-pressurisation” will not only reduce the level of their physical and mental health but also lose their lives in safety accidents caused by their fatigue riding. The purpose of this article is to examine whether there is overwork among IDS riders in big and medium cities in China? What's going on with them? Based on the Cobb-Douglas production function in the input-output theory, this study characterised the factors on IDS riders' safety and health associated with labour intensity. A mediating model with moderating effect was adopted to describe the mediation path for the 2,742 IDS riders who were surveyed. The results of moderating regression demonstrated that (1) 0.4655 is the total effect of labour intensity on the safety and health of IDS riders. (2) 0.3124 is the moderating effect that working hours make a greater impact on labour intensity. (3) The mediating effect of work pressure is the principal means of mediation both upstream and downstream.

Introduction

The Instant Delivery Service (IDS) riders have been linked to the city's capillaries. The outbreak of COVID-19 prompted the number of IDS riders to increase in early 2020. The IDS riders delivered food, vegetables, and medicines to the inhabitants ignoring the dangers to themselves both day and night during the epidemic period. 20.8% of IDS riders are serviced by riding more than 50 kilometres per day ( 1 ). The number of workers has increased significantly in new employment forms such as online appointment distributors, online appointment drivers, and Taxi drivers employed on the Internet platform. IDS workers have bounded to the “human component” ( 2 ) of IDS which set up the game mechanism depending on the AI system, especially the IDS riders.

Most of the work of couriers takes place outdoors, where they are exposed to various environmental conditions such as weather, pollution, and the risk of accidents ( 3 ). The demand for fast deliveries and payment per delivery in some modes of employment put extra stress on couriers that increase the risk of unsafe behaviours and involvement in accidents ( 4 – 6 ). Statistics for Great Britain show that motorcyclists are more at risk of being killed or injured in a road traffic crash than any other type of vehicle user ( 7 ).

There was a definite relation between hours of work, fatigue, and involvement in a road accident ( 8 ). A number of studies have demonstrated that the risk of a motorcyclist having a crash increases with exposure and falls with age and riding experience [e.g., ( 7 , 9 – 11 )], increase crash risk include riding too fast e.g. ( 12 – 14 ).

Gig's work led some couriers to experience impairment caused by fatigue and pressure to violate speed limits and to use their phones whilst driving ( 15 ). Descriptive analysis for the assessed mobile phone use while driving (MPUWD) behaviours showed that 96.3% ( N = 315) of food deliverymen undertook the MPUWD behaviours, food deliverymen, interact with mobile phones while on work-related travels mostly for business rather than entertainment ( 16 ). One notable exception was intersections, where the risk of being involved in a conflict was twice as high for e-bikes as for conventional bicycles. The speed immediately preceding a conflict was higher for riders of e-bikes compared to conventional bicycles, a pattern that was also found for mean speed ( 17 ). Motorists tend to accept smaller gaps in crossing situations in front of an oncoming e-bike compared to a bicycle approaching at the same speed ( 17 ). This effect was hypothesised to be the result of an apparent mismatch between the cyclist's actual speed and the speed perceived by the motorist. Given that the motorised component eases acceleration for the e-bike rider, it could be expected that mis-judgements of e-bike speed are especially prevalent at intersections, resulting in an increased number of conflicts ( 17 ). Safety attitudes had a significant negative effect on aberrant riding behaviours. E-bike riders reporting more errors and aggressive behaviours were more prone to at-fault accidents involving. E-bike riders who had stronger positive attitudes towards safety and showed more worry and concern about their traffic risks tended to be less likely to engage in aberrant riding behaviours ( 18 ). The emergence of the gig driver could give rise to a perfect storm of risk factors affecting the health and safety not just of the people who work in the economy but of other road users ( 15 ). Higher traffic violations of laws, more and more frequent traffic accidents and casualties, it cannot be underestimated for IDS riders' safety.

Today, anyone who can prove their right to work in the UK can put themselves to work via on-demand platforms such as Deliveroo ( 19 ), which has successfully drawn in full-time and part-time riders, including students, migrant workers, and those looking to supplement their incomes with gig work ( 20 ). Were any of these individuals to suffer a crash, however, they would not qualify for employee compensation. Deliver riders are classified as “self-employed contractors rather than as employees of the company” ( 21 ).

IDS companies control the employees by carrying out “over the horizon management” and flat management by Internet technology ( 22 ). It is naturally and constantly weakened for the formal employment contract of IDS workers. IDS workers with informal employment relations cannot be protected by China's industrial injury insurance. The amount of compensation is very limited even if parts of workers insure themselves commercially.

The properties of the hegemonic factory regime make the employees working on the IDS platform be no sense of commitment and identity to their profession ( 23 ). IDS riders' work is instrumental and transitional. “No life, but work,” ( 24 , 25 ) The poor living conditions are only for the reproduction of physical strength and recovery of labour tools. IDS rider's concept of labour time and space runs counter to the presupposition of labour law, and their injury to occupational health and physical and mental health deviates from the labour legal standard.

Reportedly, delivery riders are temporarily employed, poorly paid, and often paid “by the job,” e.g., paid by the hour or the number of delivery goods ( 26 ). This tends to induce an intense work pace for long hours, without breaks but also higher work stress, work fatigue, and unsafe driving behaviours, e.g., running a red light or a stop sign ( 27 , 28 ). Since the motorcyclists could be forced by employers to shorten the delivery time ( 29 ), they could be forced to commit traffic violations inevitably ( 27 ). Many restaurants in Korea maintain quick-delivery service programs to satisfy customers. This service allows delivery workers limited time to deliver, which frequently puts them in danger ( 30 ). Stress and work overload were associated with reduced safety behaviour and increased risk of involvement in accidents ( 31 ).

The workers' fatigue savings formed by their high intensity of labour and pressure of life seriously affect their safety and health. It is seen often enough that overwork and sudden death of IDS riders.

Papakostopoulos and Nathanael ( 32 ) reported that the delivery industry lacks a safety culture, thus making risk-taking acceptable for a delivery rider in Greece. At least in this particular socio-cultural context, the estimated compliance of food delivery companies to safety and health rules suggesting to do so. This is supported by the vast majority of respondents (83%) reporting an intensive work pace (more than 3.5 deliveries per hour) suggesting that employers vastly promote fast delivery over self-protection ( 32 ). The fatigue savings of IDS riders mainly arise from the work game design of the platform and the cognitive psychology at work ( 33 – 35 ). To study the association factors and mechanism why IDS riders will be overworked, we should consider the factor of labour intensity. This paper analyzes the mediation path of the impact of labour intensity on safety and health in physical and mental, based on the hypothesis that labour intensity has a direct impact on IDS riders' safety and health.

It is the scholars abroad who first began their research of IDS riders. However, most of the research results focused on the safety guarantee of riding. With the development of China's platform economy, domestic scholars began to study IDS riders. However, most of the research results are related to their life and work on rights ( 36 ). In terms of research methods, qualitative research is generally carried out from the perspective of law and management. In these qualitative studies, there are few results on IDS rider health issues. From the literature search, there are few empirical studies on IDS riders by Chinese scholars ( 37 , 38 ). Of course, little empirical research is on the health issues of IDS riders.

This research mainly makes breakthroughs from two aspects: (1) In discussing the economic problem of IDS riders' income, their safety and health are also considered, and high-quality employment is promoted from the employment problems. (2) An empirical method is used to describe the intermediary path of IDS riders' safety and health.

Participants and Procedure

From June 2020 to June 2021, A total of 3,000 questionnaires were distributed in 16 districts and 2 counties in Beijing and 13 administrative regions in Wuhan (no survey was conducted in 6 functional areas).

The participants of IDS riders are from 12 IDS companies including Meituan, ELM, SF Express, EMS, JD, YTO, STO, ZTO, Rhyme Express, TTK Express, Best Express, and Homestead Express. These 12 companies have the largest scale in China's express industry and absorb a large number of IDS riders. They are also the most standardised enterprises which carry out the labour law standards. For IDS riders, these companies with formal management should be able to better protect their health and avoid overworking. If the employees of these companies are in a state of overwork, it shows that the sample is more persuasive.

According to the “Code of Occupational Classification of the People's Republic of China” (2015 Edition), the “National Occupational Standard for Express Operators” (Draught), IDS riders were identified as our research object. They mainly focus on food and beverage distributors and express delivery. The research in the express industry is usually conducted when they pick up and pick up goods from 9 to 11 a.m. Because their personnel is relatively concentrated at this time. IDS riders in food and beverage distributors usually concentrate from 8:30 to 10:30 am. Before and after the morning meeting of the company, they can communicate freely or inquire about orders online for a while. Because there are few orders during this period, it is more convenient to investigate IDS riders in food and beverage distributors during this period.

In this study, if IDS riders are directly probability sampled, they would refuse to investigate because of their busy work. The sample selection process is judgmental sampling. We get the cooperation of enterprise management through the intervention of the administrative organisation. Judgment sampling, a non-probability sampling procedure, has low operation cost and is also suitable for the objective situation of tight funds in this study. Although there are disadvantages of tendentious influence, IDS riders have a high coincidence of working properties, so the non-probability sampling results can be inferred as a whole.

Among the questionnaires, 2,000 were distributed in Beijing, 1,000 were distributed in Wuhan, 2,848 were recovered, 107 invalids were excluded, and the rate of recovery was 94.9%, and the rate of effectiveness was 91.4%. Of the 106 invalid questionnaires, 95 were incomplete (the IDS riders did not complete the questionnaire). Because the answer results should be analysed together with the working conditions of the respondents, it is necessary to avoid mutual consultation when filling in together in the workplace. Six questionnaires cannot be counted due to the lack of data or inconsistencies between filling in and out. Five questionnaires were filled in by others instead, so we eliminate them. Therefore, we get 2,742 observations.

We take Beijing and Wuhan as the research areas, mainly because Beijing is a megacity and Wuhan is a megacity 1 .

These two cities are very developed and representative cities in express delivery. One is the capital, whose industrial development plays the role of a wind vane. Another reason is that Beijing has a simple terrain of the traffic route map, which can be used as a concise sample representative of urban planning. Wuhan is located in the central region, and its development level is equivalent to the national average standard. Wuhan has complex terrain, intricate, and intersecting rivers, lakes, and a vast area, which can be used as a sample representative of complex urban planning.

Data Analyses

The questions about safety and health in Part 1 of the questionnaire are mainly based on the Cumulative Fatigue Symptoms Index (CFSI) ( 39 , 40 ), Fatigue Scale-14 (FS-14) developed by Japan ( 41 ), and Fatigue Assessment Instrument (FAI) ( 42 ).

Japan's Fatigue Assessment Instrument has many design items, including not only physical but also spiritual. In addition to working conditions, it also analyzes the main causes of damage to health in working life from the aspects of living time and living conditions ( 43 ).

The results of factor analysis are classified and a new item classification is obtained 2 . CFSI includes five major causes, including sleepiness (Group V), restlessness (Group V), unhappiness (Group III), fatigue (Group V), and vertigo (Group V). It is composed of 25 subjective fatigue descriptions.

Fatigue Scale-14 was jointly compiled by Trudie Chalder ( 41 ) of King's College Hospital's psychological medical research laboratory and G. Berelowitz of Queen Mary's University Hospital in 1992. The scale consists of 14 items, including two dimensions: first, physical fatigue, which mainly evaluates physical strength, muscle strength, and rest, with a total of 8 items; The second is mental fatigue, which mainly evaluates memory, attention, and quick thinking, with a total of 6 items. FS-14 requires respondents to answer “yes” or “no” according to their actual situation, in which “yes” is 1 and “no” is 0. The higher the score, the more serious the fatigue is.

Fatigue Assessment Instrument was formulated by Joseph E, Schwartz of the American Psychiatric and behavioural sciences research laboratory, and Lina Jandorf of the neurology research laboratory in 1993 ( 44 ). Workers can make self-assessments based on this scale, which includes four dimensions: first, the severity of fatigue, which has 11 items; Second, the environmental specificity of fatigue, including 6 items; The third is the result of fatigue, including three items; fourth, the response of fatigue to rest and sleep, including 2 items. Each item in FAI shall be graded from 1 to 7.

The scale consists of 14 items, including two dimensions ( 45 ): first, physical fatigue, which mainly evaluates physical strength, muscle strength, and rest, with a total of 8 items; The second is mental fatigue, which mainly evaluates memory, attention, and quick thinking, with a total of 6 items. Fs-14 requires subjects to answer “yes” or “no” according to their actual situation, in which “yes” is 1 and “no” is 0. The higher the score, the more serious the fatigue is.

In the questionnaire of IDS riders, we designed options such as irritability, unable to control emotions, sleepy at work, lack of motivation, feeling weak limbs, and so on. According to the data in the survey, 50.4% of IDS riders sometimes felt impatient, irritable, and unable to control their emotions by themselves. They sometimes want to drop express items on the ground. 20.2% of them even often did that too. In the options about health, 27.2% of them have frequent physical issues (headache/dizziness/heart discomfort/tinnitus/dizziness, etc.). Comparing their stress of mental with physical, 56.3% chose “mental stress is greater than physical stress.” Regarding work status, 30.6% were in the range of 9–20 (II). 42.5% were in the range of 21~27(III). More than 20.4% were above 28 (IV) in the statistic. Making statistics on work Burden Indices, we found that 26% were in the early warning zone, 35.1% were in the danger zone, 23.3% were in the danger zone, and 6.2% were in the high-risk zone.

From the analysis above, according to the statistical data, we would conclude that most IDS riders were in an overworked state.

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable is the Work Burden Index reflects the degree of overwork in the zone of health risk, which is to measure the status of IDS riders' safety and health. The variables are in order. A higher value indicates lower health. The Work Burden Indexes representing safety and health are classified by I, II, III, and IV levels based on the 2 scales of self-conscious symptoms and working conditions.

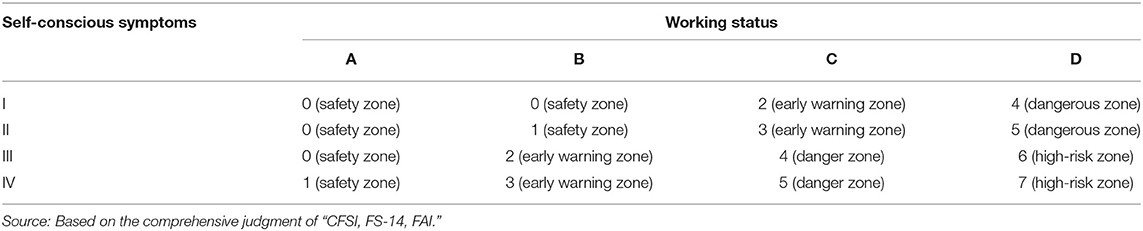

The 7 points in a matrix 3 . form different zones of safety and health. The safety zone, early warning zone, dangerous zone, and high-risk zone can be seen in Table 1 .

Table 1 . Score of IDS riders' overwork (Work Burden Index).

In the zone of 0–1 point, IDS riders' job is easy and the hours are good; In the range of 2–3 points, IDS riders have a work burden, and their safety and health in the early warning zone; In the range of 4–5 points, IDS riders have a higher work burden and be in the danger zone; In the range of 6–7 points, IDS riders are in the high—risk zone.

According to the Work Burden Index matrix, safety and health are mainly completed in three steps.

Step 1: Divide the fatigue symptoms into health grades according to the Self-Diagnosis Scale of Fatigue Accumulation of Workers issued by the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare in Japan, Safe Production Law of the People's Republic of China, and Guiding Opinions on Safeguarding Workers' Rights and Interests of Labour Security in New Forms of Employment issued by eight departments in China 4 . Construct an evaluation system to measure IDS riders' work burden. This system combined with the Fatigue Assessment Instrument, FS-14, Fatigue Scale-14, and the ten early warning signals of “overwork death” issued by the Japan Overwork Death Prevention Association. Then a scale is established to measure IDS riders' subjective feelings of fatigue, including 14 items: such as “impatient, irritable, unable to control their emotions, sometimes want to drop the delivery items on the ground,” “frequent physical issues (headache/dizziness/heart discomfort/tinnitus/dizziness, etc.).” The scores and grades are as follows: 0–8 is for I, 9–20 is for II, 21–27 is for III, and 28 or more is for IV.

Step 2: Classify the grade of work level. Eight items are in the work condition evaluation form, such as “sudden increase in the number of receiving and sending, the need to work overtime” and “mental pressure caused by work.” The standard of score and level are: 0 ~ 8 points are Grade A, 9–15 points are Grade B, 16–23 points are grade C, and more than 24 points are grade D.

“Five score rating scale” was drawn according to IDS riders' work. They are “never so (0), rarely so (1), sometimes so (2), often so (3), and always so (4).”

Step 3: Build a conscious symptom and work condition matrix to determine the safety and health zone of IDS riders.

Independent Variables

According to National Standard GB3869-83, physical labour intensity was divided into four levels: I (light labour), II (medium labour), III (heavy labour), and IV (extremely heavy labour). The measurement indicators are average energy consumption and net labour time 5 . However, it is difficult to measure the energy consumption in the survey. IDS riders' work is mainly determined by working hours and riding distance. (In the structural survey, we found that many riders are not only interested in the number of orders, but also concerned about their daily odometer). In this paper, the “average daily distance” is instead of the “energy metabolism rate” in National Standard GB3869-83. We keep the calculation formula and calculation coefficient unchanged. A calculated six-level labour intensity index is used as the independent variable.

Instrumental Variable

As the needs of the instrumental variable are correlated with the independent variables, the frequency of traffic offences and orders are tailored to the instrumental variables. The correlation is that IDS riders are easily distracted while driving in the mood of high work intensity and pressure. It is easy for IDS riders to cause traffic violations facing plenty of orders. Labour intensity increases with the increase in the number of orders. There is a correlation between the number of orders and labour intensity.

The instrumental variable also needs to meet the condition that it is not correlated to the disturbance item. We find that the number of orders is qualified as an instrumental variable that has no correlation to the random disturbance term. However, being the new economic form, IDS riders obtain tasks randomly on the platform through “online order-grabbing.” Random orders are knocked out without limited time and placed by different millions of customers on the platform. Since the random orders do not correlate with the error term, the instrumental variable is credible.

Another instrumental variable of traffic violation frequency has random too. Complex and changeable traffic full of the constant flow of vehicles and people randomly happens on traffic violations or accidents. Similarly, traffic violation frequency meets the requirements of an instrumental variable.

Theory Model

An increasing number of employees of IDS workers sign up for the IDS platform. It is a rational choice for flexible employees under the development situation of the new economics. U ij is for the utility of the IDS riders in the state of reasonable working hours and pleasant mood, and U ik is for the utility while they are in physical and mental fatigue state. WhenU ij ≥ U ik , IDS riders have higher physical health. IDS riders' utility is determined by career and restricted by the status of their family economy and the way to get income. As it is known to all, those characteristics of IDS riders have a low employment threshold, which makes them limited space for career to transform and less income to improve. An Intertemporal Utility Model for IDS riders can be constructed using the C-D Function:

Where U is for the utility of IDS riders, L1 and L2 are for IDS occupation and leisure consumption while quitting IDS, θ∈[0, 1].

Suppose that labour intensity is α∈[0, 6] 6 . In this paper, the average daily distance is used to replace the energy metabolic rate in the National Standard GB3-83. We keep the calculation formula and the coefficient of the labour intensity index. The “Daily Distance” is divided into 6 levels as the labour intensity index.

A rise α indicates an increase in labour intensity. The budget constraints for the two periods are

Among them, L 1 is the labour supply during the working period, and C is the total consumption expenditure for IDS riders' daily living; S is the savings during the working period, is the health cost during the working period, is the salary, t (α) is the working hours, and E is the non-labour income. The labour intensity α will affect by health costs, wages and working hours, etc. L 2 is the consumption of physical or leisure while quitting IDS, refers to the health cost after quitting IDS occupation, Y refers to the IDS riders' old-age pension, λS refers to the savings and transferred interest after quitting IDS occupation, and ln f is the legacy and death gratuity left to their family. Consumption capacity after they quit IDS depends on their all pension, savings, and the property left to their family.

Construct the Lagrange Function and take a derivative of labour intensity to solve IDS' Intertemporal Utility Function:

It can be seen from the above formula that the impact direction of labour intensity on the occupational utility of IDS riders is related not only to wage and working hours t (α), but also to the impact of labour intensity on wagesand working hours ∂ t ( α ) ∂ α , and so does the impact on intertemporal health costs and .

Measurement Model

The average age of IDS, riders is 26.4 years old. The employees are mainly male youth. This paper assumes that IDS riders are homogeneous, [λ(1−θ)] 1−θ and θ θ are constants 7 and >0; More labour supply will result in increases in working hours and salary. Both ∂ ω ( α ) ∂ α t ( α ) and ∂ t ( α ) ∂ α ω ( α ) will be >0. IDS riders will ignore or overdraft the health cost (current and future) to work which is likely an economic rational choice under the constraint of the platform. and will be also >0. According to these theories, we can deduce Hypothesis 1.

H1: The increase in riders' labour intensity makes the Work Burden Index rise, which eventually leads IDS riders to overwork and is in the zone of health risk.

Due to the order-grabbing system in the IDS industry, the substitution effect of labour supply caused by salary is greater than the income effect. To increase working hours, the result is to improve labour intensity. From this, we can get Hypothesis 2.

H2: Salary and working hours play a moderating role.

The effect of increasing work intensity on health is not direct, where job stress and job satisfaction have a mediating role. Therefore, we can propose Hypothesis 3.

H3: Job stress and job satisfaction play a mediation role between labour intensity and safety and health.

Labour intensity is ordered by multiple categorical variables, and its value has only ordered significance and lacks an interval scale. Therefore, this study selects the Ordered Multinomial Logistic Regression Model:

Where, H is the health degree of IDS rider i in an urban area j , and LI (Labour Intensity) is the labour intensity of IDS rider i in an urban area j ; X ij is the control variable group; α, β and γ are the parameters to be estimated.

However, there are many factors affecting the health level of IDS riders. In addition to the physical health level characteristics of IDS riders, there are also external complex factors such as urban discrimination against migrant workers, riders' living conditions, and living environment. It is difficult to completely control in the model, and other unobservable factors may be omitted, which would result in the endogenous problem. On the other hand, there can be a reverse causality between labour intensity and safety and health. Different knowledge about familiarity with urban rods will make IDS riders safer and healthier. The safety and health of IDS users will also be exacerbated by the degree of congestion in various sections of urban traffic and psychological discouragement after poor evaluation. Due to the endogenous problem, this document selects an identification strategy by the instrumental variable analysis. We adopt IV-Logit Two-stage Estimation Method after adjusting the Logit Model above.

Estimated Results

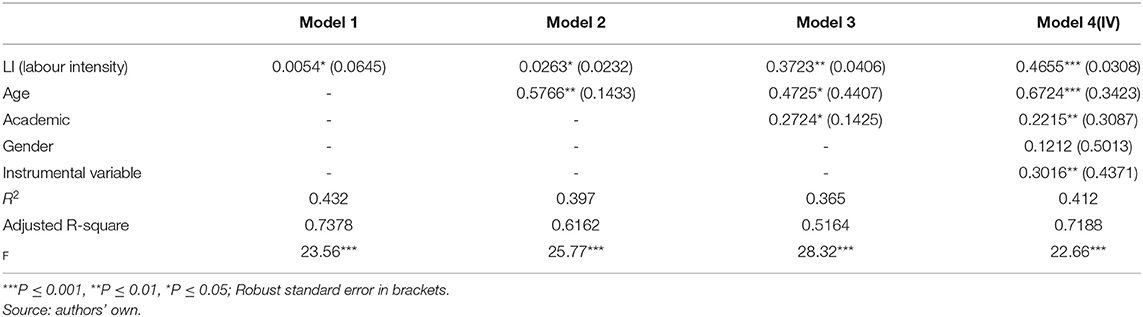

The regression results in Table 2 , Model 1 only includes the core independent variable, and the significance of the regression results is not too strong. The age control variable was added to Model 2, and the test results were slightly improved. Three control variables of age, education, and gender were added to Model 3, and the significance was greatly enhanced. Model 4 adopts the IV-Logit Two-stage Method, the regression coefficient is more statistically significant, and the result is more reliable.

Table 2 . Model estimation results.

In model 4 (IV), the regression coefficient is significantly positive and the intensity is high. H1 is verified and supported. The increase in labour intensity will greatly increase the work burden, so it is a negative impact on safety and health.

Extreme Working Environment Analysis

We did not do a heterogeneity test for IDS riders of the model. The safety issues, more dangerous than health, are caused by the extreme working environment. Structure investigation is adopted to analyse the problem of safety.

Instant Delivery Service riders are exposed to outdoor work most of the time. The external factors harm their safety and health, such as hot sun, high temperature, fierce wind, rain and snow, and daily breathing exposure. Daily breathing exposure is mainly due to the excessive PM2.5 in haze air. The little difference in daily breathing exposure for the whole urban residents, so IDS riders are afraid of the hot sun, high temperature, wind, rain, and snow. Poor working environment, especially the extreme weather has the greatest impact on IDS riders. However, in the survey, it is believed that the impact of wind, rain, snow and high temperature, and hot sun on safety are, respectively, 78, 88, 94, and 23%. According to the structural interview survey, IDS riders generally don't care about the high temperature and hot sun. What is the reason that they take the first three items seriously, but the high temperature? It may be that the high temperature cannot prevent them from delivering. Another reason may be that they know little about the probability of heatstroke which leads to death. They have no medical understanding that high-temperature thermal fatigue may potentially induce safety and health issues, such as heart disease and coronary heart disease.

Mediating Path Analysis

The transmission path between labour intensity and safety and health is as follows: the stronger become the labour intensity, the greater cost the of safety and health. Labour intensity is not beneficial to physical safety and health.

A high income formed by labour utility may make IDS riders satisfied with their work. High satisfaction work makes workers be in good health, physical and mental. The impact is positive. While the work pressure of long working hours does harm workers physically and mentally. Then, that impact is negative. Therefore, in this study, we take income and working hours as moderating variables.

Salary has a substitution effect and an income effect. The income effect makes fewer working hours, while the substitution effect makes workers work more. The total effect is uncertain. But for IDS riders, being a game of orders-grabbing, the substitution effect of salary is greater than the income effect.

Our study explores the variable's role and the mediation path by applying Muller's Chain Mediating Effect Model with moderating variables.

H ij represents safety and health, and G ij represents the moderating variables of salary and working hours 8 The data on salary comes from the 7-income range of monthly income in the questionnaire, and the data on working hours come from 4-time ranges in the questionnaire.

M p (p =1-3)is the mediating variable: work stress M 1 includes 5 dimensions, Calculate the mean value of 5 dimensions as the variable: “24 h rest/month, labour contract, social security, perception of competitive stress, and poor comments,” which is answered in four grades. Job satisfaction M 2 is investigated from six dimensions. The mean value is calculated in the same way. Six dimensions are “organisation satisfaction, management satisfaction, job reward satisfaction, working atmosphere satisfaction, the job itself satisfaction, and human resource management satisfaction,” which are answered in five levels of satisfaction. The chain mediating variableM 3 is expressed by “job stress * job satisfaction.”

Mediating Effects Test

To analyze the mediating effect neatly, the moderating effect is not considered.

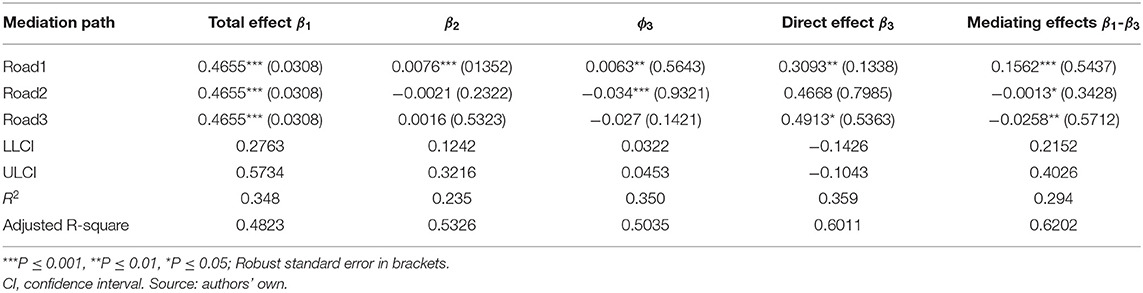

According to the mediating effect results in Table 3 , the front-end effect of Road 1 is significant, and the back-end effect of the Road 1 mediation path is also very significant. It is not difficult to find that job pressure is the leading mediating variable leading to safety and health. Hypothesis 3 is verified job pressure has a mediating effect.

Table 3 . Estimation results of chain mediating effect.

Moderating Effect Test

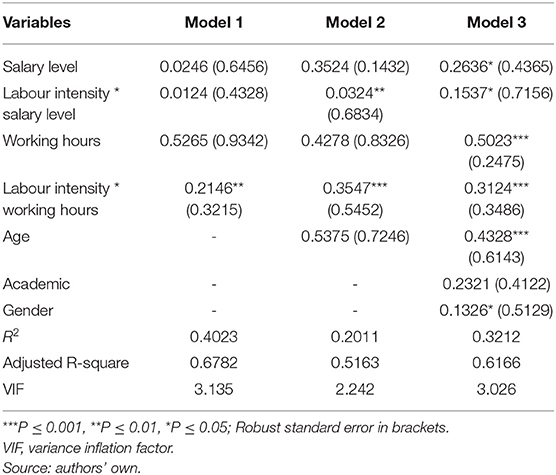

Data is centralised before the two variables G ij are used in moderation. Hierarchical Regression is carried out for the two generated interactive variables. The linear regression estimation results of the model with moderating variables are shown in Table 4 .

Table 4 . Estimation results of moderating effect.

According to the estimation results of the moderating effect in Table 4 , the impact of salary on labour intensity is not significant, and the extension of working hours has a positive effect on labour intensity. The significance test of multiplication of salary and labour intensity is passed at 10%. Though the moderating effect of salary on labour intensity is determined by the income effect and the substitution effect, the total effect is positive. Facing the temptation of salary, IDS riders will take the initiative to grab more orders to earn more money. In reality, platform work has only changed mechanisms through which companies can exercise control over labour and evade their employer obligations. The freedom of food delivery platform workers is essentially an “illusory freedom” ( 49 ).

As a result of an increase in labour intensity, they will be overworked, which is no benefit to their health. The multiplication of working hours and the labour intensity is tested at the significance of 1%. It shows that the IDS riders' labour intensity increases with the extension of working hours, and the resulting job pressure will affect their health, and even their safety. We verified that both salary and working hours have a moderating effect on labour intensity, and the effect of working hours is greater, so Hypothesis 2 is tested.

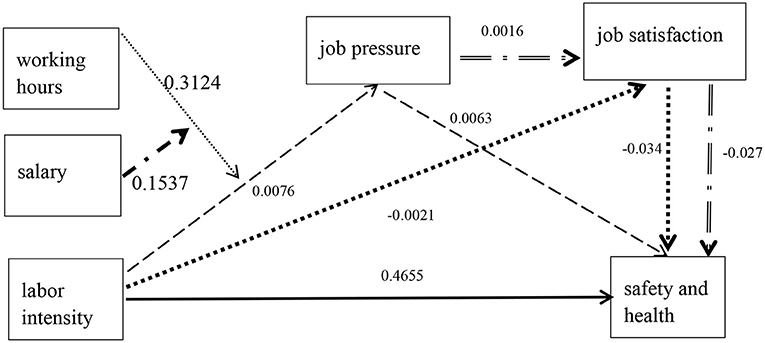

We can see the health mediating effect of IDS riders in Figure 1 . Overall, in the mediating effect, job pressure has not only a strong impact on the front-end effect but also a strong mediation path in the back-end effect. Job satisfaction is a weak mediation path in both the front-end effect and the back-end effect. The mediating effect of job pressure is 0.1562 (β 1 -β 3 = 0.4655–0.3093). The change in salary causes the change in working hours, which leads to the change in labour intensity and job pressure. The moderating effect of salary is 0.1537 and the moderating effect of working hours is 0.3124. Working hours increase labour intensity and then affect safety and health through job pressure. Labour intensity has a positive impact on safety and health. The total effect of labour intensity on safety and health is 0.4655.

Figure 1 . Impact path of the labour intensity on safety and health.

The index of job pressure mainly includes five dimensions: “complete rest days per week, signing of the labour contract, social security participation, perception of competitive pressure, and perception of dealing with bad comments.” Take the mean value as the working pressure variable and evaluate it with 4 grades of “very small, small, general, large, or very large.”

The index of job satisfaction is formed by a six-factor analysis of “organisation satisfaction, management satisfaction, job reward satisfaction, working atmosphere satisfaction, the job itself satisfaction, and human resource management satisfaction.” Five grades are formed by Likert five subscale methods: “very dissatisfied, relatively dissatisfied, average, relatively satisfied, and very satisfied.”

The regression coefficient of labour intensity is 0.0076, which can cause work pressure. Labour intensity can directly lead to the decline of physical health and make IDS riders enter a state of overwork. For other job characteristics, it appears that workers in the app-enabled gigs are ordinarily doing standardised tasks repeatedly over a period of time, the structured algorithmic management techniques offer workers a high level of autonomy ( 50 ). Unstable employment tends to negatively affect health status. As it causes psychological and physical health risks, such as low mental health, dissatisfaction with physical health, anxiety, or high blood pressure. Platforms have added “digital reputation mechanisms” or “evaluating and rewarding mechanisms.” Their real motivation is to let IDS riders grab orders and compete to increase labour intensity.