The effects of business ethics and corporate social responsibility on intellectual capital voluntary disclosure

Journal of Intellectual Capital

ISSN : 1469-1930

Article publication date: 9 March 2021

Issue publication date: 17 December 2021

This study aims to examine the potential effect that business ethics (BE) in general and corporate social responsibility (CSR) more specifically can exert on the voluntary disclosure (VD) of intellectual capital (IC) for the ethically most engaged firms in the world.

Design/methodology/approach

The research design is based on an inductive approach. As part of the global quantitative investigation, the authors have analyzed the impact of BE and CSR on the transparent communication of the IC. The data under analysis have been investigated using multiple linear regression.

Based on a sample of 83 enterprises emerging as the most ethical companies in the world, the results have revealed that the adoption of ethical and socially responsible approach is positively associated with the extent of VD about IC. This finding may help attenuating the asymmetry of information and the conflict of interest potentially arising with corporate partners. Hence, IC-VD may stand as an evidence of ethical and socially responsible behaviors.

Practical implications

Global and national regulators and policymakers can be involved by these results when setting social reporting standards because they suggest that institutional and/or cultural factors affect top management's social reporting behavior in the publication of the IC information.

Social implications

Direct and indirect stakeholders, if supported by ethical and socially responsible behaviors of the company, could assess more in detail the quality of the disclosed information concerning the IC.

Originality/value

Most of the studies that have been conducted in this field have examined the effect of BE and CSR on the firm's overall transparency, neglecting their potential effect on IC disclosure. This study is designed to fill in this gap through testing the impact of ethical and socially responsible approaches specifically on IC-VD.

- Business ethics

- Corporate social responsibility

- Voluntary disclosure

- Intellectual capital

- Transparency

Rossi, M. , Festa, G. , Chouaibi, S. , Fait, M. and Papa, A. (2021), "The effects of business ethics and corporate social responsibility on intellectual capital voluntary disclosure", Journal of Intellectual Capital , Vol. 22 No. 7, pp. 1-23. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-08-2020-0287

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2021, Matteo Rossi, Giuseppe Festa, Salim Chouaibi, Monica Fait and Armando Papa

Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

Over the last few decades, firms have been generating value not only from securities and financials but also from other intangible elements, such as skills of employees (human capital), novelty in technology (structural capital), relationships with customers (direct relational capital) and reputation on the market (indirect relational capital or social capital), all forms of potential intellectual capital (IC), whose contribution, however, is probably riskier than industrial assets ( Su, 2014 ; Cruz-González et al. , 2014 ). In fact, the impact of IC on the business results is uncertain, and in addition, it is often more difficult to identify and measure its characteristics ( Murray et al. , 2016 ).

The uncertainty about its representation and measurement still poses issues related to accounting, evaluation and governance ( Hussi, 2004 ; Guthrie et al. , 2006 ; Hamed and Omri, 2014 ). To limit these problems, managers may choose voluntary disclosure (VD) to reduce the asymmetry of the information ( Branco and Rodrigues, 2008 ).

IC is a driving factor and creator of lasting value ( Lin et al. , 2015 ; Vaz et al. , 2019 ), and disclosure by applying ethical and social principles improves the trust of information and reduces the conflict of interest ( Alves et al. , 2012 ; Chung et al. , 2015 ; Al Maskati and Hamdan, 2017 ). These behaviors may exert a positive effect on the global quality of the IC-VD ( Melloni, 2015 ), and in this study, more specifically, VD of nonfinancial information about IC are assumed to be positively influenced by ethical and socially responsible behaviors of the company's decision-makers ( Corvino et al. , 2019 ).

In this respect, interest in the development of business ethics (BE) and corporate social responsibility (CSR) in accounting, evaluation and management has gained increasing attention in the academic literature ( Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998 ), and the last 20 years (or even more) of empirical research on these issues have generated vast literature ( Gray et al. , 1995 ; Chen and Gavious, 2015 ; Singh and Gaur, 2020 ). Accordingly, the quality of the information published by companies about their IC has received an ever more peculiar interest in managerial research ( Ousama and Fatima, 2012 ; Muttakin et al. , 2015 ; Devalle et al. , 2016 ; Bellucci et al. , 2020 ), with specific concerns about the effect of BE and CSR on the quality of the disclosed information on voluntary or mandatory basis, also considering several financial scandals that have added doubts about relevance and reliability of some company data ( Lehnert et al. , 2016 ).

Subsequently, a critical question is the following: is it adequate, opportune and reliable to take into consideration only the accounting information that mandatorily concern IC, especially considering that this entity is so difficult to identify and measure? This issue seems deserving huge attention particularly in the current context, constantly and continuously marked by the rise of BE and CSR, with consequent effect also on the relevance of the quality of the disclosed information.

For example, the legitimacy theory provides some contributions regarding environmental reputation, and the related effect of VD on reputational capital ( Alvino et al. , 2020 ). In this respect, the reputation of the company is a social construct stemming from the process of legitimization ( Bond et al. , 2016 ).

However, empirical studies investigating the effect of BE and CSR on VD have proved mixed results, mostly because of the different meaning about ethics and responsibility in each institutional and cultural context ( Ting et al. , 2020 ). The current study aims to combat this diversity and its consequences in terms of value creation, analyzing more specifically the potential effect of BE and CSR on the VD of IC ( Giacosa et al. , 2017 ).

The perimeter of the research regards the companies that are ranked by the Ethisphere Institute – most probably the global leader in the world for defining and advancing the standards of ethical and social practices that fuel corporate character, market trust and business success – as the most ethical companies in the world. More precisely, the contribution of the study is in checking whether the companies' behavior about IC disclosure is influenced by BE and CSR, aspect that has been often neglected in other studies.

In this respect, a research concerning companies displaying high level of ethical and socially responsible commitment has been conducted, with two main ambitions. First, results should enable to explicitly identify the characteristics that are more likely to influence the diffusion of information about IC in the annual reports through adoption of BE and CSR; second, it should help exploring the contribution of the several company characteristics as assessed in terms of ethics-based scoring.

The empirical evidence emerging from the research has demonstrated that the adoption of approaches that are based on BE and CSR noticeably help in enhancing the disclosure extent of the IC information as figuring in annual reports. Thus, this study should serve to provide further recommendations to the companies intending to adopt codes of ethics, or to put forward CSR practices, encouraging these behaviors also from the point of view of the IC disclosure (and consequent accounting, evaluation and management).

The structure of this paper is organized as follows; Section 2 presents the basic theoretical background and the hypotheses that have been developed: in this section, the relationship between the potential effect of BE and CSR on the VD of IC has been analyzed. Section 3 displays the methodology that has been adopted, while the empirical results are exposed and discussed in Section 4 ; finally, the discussions of the findings, the concluding remarks and their implications are provided in Section 5 .

2. Theoretical background and hypotheses development

As aforementioned, the following investigation is about the effect of BE and CSR on IC-VD, also for clarifying the distinct influences that may arise from concepts that sometimes are considered in ambiguous connection ( Fassin et al. , 2011 ). Therefore, the first step of the research is about a general analysis of the studies focusing on the association between ethical as well as socially responsible behaviors and IC-VD as core aspect of a more global knowledge management approach that cutting-edge enterprises should adopt to succeed ( Serenko and Bontis, 2013 ).

2.1 Theoretical background

To present main reasons and usefulness of the VD of information about IC, the theory of planned behavior has been adopted as fundamental approach. In fact, although extensive research has focused on the variables that externally and internally may influence the managers' decision about disclosing information on IC, few studies have examined in this respect the psychological factors and have used a theoretical decision-making framework ( Coluccia et al. , 2017 ; McPhail, 2009 ).

The theory of planned behavior, largely used to explain the process of individual decision-making behavior ( Ajzen, 1991 ), can emerge as a theoretical framework for investigating the psychosocial factors stimulating the managers' decision to disclose IC information in a mandatory and/or voluntary way. In addition, this model has demonstrated its superiority over other theoretical approaches in many contexts of VD, including IC ( Zhang et al. , 2019 ).

This theory assumes that when individuals, considering altogether internal attitudes and external considerations, perceive a manageable activity as capable of providing business benefits, such as those that may arise from IC-VD, they receive intention, support and encouragement in adopting that specific behavior, also making assumptions about their ability to perform the task ( Passaro et al. , 2018 ; Mura et al. , 2012 ).

For example, Armitage and Conner (2001) examined 185 empirical studies that were conducted prior to 1997, finding that about 39 and 27% of the variance of intention and behavior, respectively, was caused by the theory of planned behavior. In fact, this theory is a rational decision-making model, which is mainly used to predict the potential behavioral intentions of the managers (in this specific case, adopting VD of IC).

Three key independent variables are at the basis of this framework: (1) the attitudes toward a particular behavior; (2) the perceptions of others' approval or disapproval of a particular behavior (subjective norms) and (3) the perceived behavioral control about easiness or difficulty in performing a particular behavior ( Ajzen, 1991 ). This configuration is adopted as methodological basis for the theoretical model in which assessing the following hypotheses.

2.2 Hypotheses development (H1) : BE and VD of IC

Transparent and reliable communication is essential to reflect the true image of a company ( Bhimani, 2008 ): with this regard, financial transparency is a necessary condition for a firm that is involved in the BE process. In the specific context of disclosure, several authors have recognized that BE rooted in organizational culture has a tremendous influence on the development of IC-VD ( Branco and Rodrigues, 2008 ).

For example, Jo et al. (2008) have analyzed the development of ethical standards in the business to improve the quality of the disclosed information, finding that entrepreneurs and managers that consider the promotion of ethical behaviors are urged to ensure permanent disclosure of the company's IC. Later, Navid et al. (2015) have found that unethical behaviors are at the basis of corporate financial scandals, workplace frauds and harassment or misleading financial reporting: such issues have raised awareness about the positive benefits of ethical behavior, also in improving VD (and then, also about IC), to limit the problems of the agency theory.

Mouritsen (2004) has found a significant gap between the market value and the book value resulting from the failure of the companies' hidden value in their annual reports: consequently, BE oriented to IC-VD would limit the problem of the business undervaluation (more specifically, VD of information about IC is positively influenced by the ethical behavior of the company's decision-makers).

On the other hand, the complexity and uncertainty of strategic decision-making require different combinations of data, information and knowledge. In this respect, some research has been conducted to examine the factors influencing disclosure of IC: Ferreira et al. (2012) have found that ownership concentration and firm size have a positive influence on the disclosure of IC, and ethical behaviors also positively influence this disclosure.

Several studies suggest that there are many benefits to acting ethically, such as improving the financial and nonfinancial performances as well as creating a sustainable competitive advantage ( Goel and Ramanathan, 2014 ; Khondkar et al. , 2016 ). In addition, in highly risky and uncertain contexts, policymakers are forced to select powerful tools over VD.

BE behaviors have positive impact on the extent of the IC-VD.

2.3 Hypotheses development (H2) : CSR and VD of IC

The economic value of the company is expressed not only by its means of production but also by the global impact that fundamentally derives from its IC ( Campanella et al. , 2014 ), activating human, structural and relational resources to generate shared value ( Porter and Kramer, 2011 ) at business, social and environmental level ( Elkington, 1998 ). As result, a new path on IC reporting sustains that all companies are increasingly required to be socially responsible and to better manage their environmental impact ( Aslam et al. , 2018 ).

In this vein, organizations have developed accounting and management systems and improved their disclosure practices according to social and environmental principles ( Khondkar et al. , 2016 ). In part, this has been due also to the fact that companies may have incentives for adopting globally responsible approaches and operating socially responsible initiatives ( Gangi et al. , 2019 ); however, a study by Türkel et al. (2016) on the European Union has provided evidence that CSR is a mean that companies may voluntarily decide to adopt to contribute to better society and cleaner environment.

From one side, Sun et al. (2010) have found that companies that need to pursue a strategy of VD of IC are brought to value CSR, and this should be positively interpreted by the various stakeholders. On the other side, regarding the potential asymmetry of information and conflict of interest that may exist, CSR should constitute a behavioral method that would have positive effect on the corporate behaviors, as it promotes transparency, also with regard to the potential VD of IC ( Beretta et al. , 2019 ).

Coherently to the dynamic resource capability perspective of (Bamel and Bamel, 2018) , Luthan et al. (2016) found that in an uncertain world, the adoption of a CSR approach could help reducing uncertainty, especially if the company discloses information about its IC. Similarly, some researchers argue that CSR is a very broad domain, and VD of IC should be considered as a social responsibility action ( Chan et al. , 2014 ).

Polo and Vázquez (2008) have described the relationship between CSR and the VD of information, to ensure the sustainability of the business in general and its operational goals more specifically. In other words, CSR is an asset for the company and the various stakeholders ( Fukukawa et al. , 2007 ) because of its direct contribution to IC (indirect relational capital, for example), with consequent influence on the relevance of the information provided by the company about its IC and knowledge properties more in general ( Rechberg and Syed, 2013 ).

Moreover, as aforementioned, Khondkar et al. (2016) have studied the effect of CSR on the quality of the information disclosed in companies' annual reports. They have found a positive relationship between the level of disclosure and the intensity of CSR, concluding that greater disclosure is a form of socially responsible behavior, thus directly and/or indirectly impacting IC ( Vrontis et al. , 2020 ).

CSR behaviors have positive impact on the extent of the IC-VD.

3. Research design

3.1 sample construction and data collection.

Being the main purpose of this study to explore the effect of BE and CSR on IC-VD, a sample of firms already involved in the process has been selected. In other words, the selectable companies have been detected among those with evident commitment and involvement in ethical and social behaviors.

Several statistical institutes are responsible for making an appropriate classification in this specific field: however, since 2007, the Ethisphere Institute ( Ethisphere.com ) has been analyzing the global market to identify, sector by sector, the most committed companies in the field of ethical behaviors, drawing up a list of the most ethical companies in the world and gaining at international level high reputation in the field ( BusinessWire.com ).

Then, the following investigation has been grounded on the Ethisphere Institute database, which considers more than 100 criteria; the most important are social responsibility, good governance, environmental impact, implementation of code of good behavior, commitment of the direction to questions of ethics and CSR, setting up of internal monitoring indicators, citizen investment and so on (it also considers negative criteria, such as the existence of disputes or infringements to sector regulations). This database provides a global overview, and the list of elected representatives reveals a real geographical diversity with several companies located outside the United States, such as the United Kingdom, Australia, Sweden, Germany, India, Guatemala, Poland, Switzerland, Saudi Arabia, Portugal and Belgium.

The data under investigation have been obtained from the Global-100 KPI 2015 database published by the independent Ethics Expert Group of the Ethisphere Institute (secondary, which have been then summarized into composite indexes, and not empirical data have been used to avoid any potential bias deriving from individual interviews concerning BE and CSR, most of all in the context of the planned behavior theory). Considered as one of the most authoritative indexes in the world due to its methodology and reliability, the Corporate Knights Global 100 designates each year the top 100 companies (out of several thousands) that are the most responsible in terms of ethical behavior.

The year 2015 has been chosen so that the data under analysis could be taken as definitively reliable, considering the time that sometimes is necessary to validate all the accounting information, most of all from a social and environmental point of view. Thus, the 2015 database, to the best of the authors' ability, is the latest publicly available for which it has been possible to collect all the necessary information for implementing the current investigation, but evidently the methodology can be replicated for any other year, when all necessary data would be available (for example, searching for the adequate data starting from WorldsMostEthicalCompanies.com ).

The initial population consisted of 4,353 companies (candidates); in a second step, 4,253 companies that did not meet the classification criteria for the first 100 companies were excluded. From the 100 best ranked companies, for the specific scope of the current research firms that are part of the financial sector, considering the very peculiar rules that govern this industry, have been excluded (i.e. 17 companies); thus, the final sample has included 83 firms, with Table 1 summarizing the sampling selection criteria.

Tables 2 and 3 describe the distributional profiles by country and by sector, respectively: the sample includes 18 developed countries belonging to 35 industries, according to the 48 industry group affiliations as figuring in Fama and French (1997) , with most firms that are based in the USA, the UK and France (these three countries make up 54.28% of the total sample).

The companies from the USA are at the top of the list, with 25% of the sample (20 firms out of 83, 24.09%): French and British companies are entitled of the second position in this ranking, respectively, represented with 10 companies on an equal basis. Then, Canada ranks fourth, since it is represented with eight firms, corresponding to 10% of the total sample (hence, these four countries account for almost 60% of the total sample).

In Table 3 , the most represented sectors are Oil, Gas & Consumable Fuels (eight firms), Pharmaceuticals (seven firms) and Chemicals (four firms), respectively. Concerning other sectors, the number of companies is more limited (three or less).

3.2 The regression model

DISC_SCO: composite index about IC-VD, calculated as combination of several elements (cf. Table 4 ).

ETH_SCO: composite index about BE, calculated as combination of several elements reflecting ethical principles.

CSR_INDEX: composite index about CSR, calculated as combination of 40 indicators reflecting principles of individual and collective social responsibility.

INVT: the degree of innovation intensity is the ratio between research and development (R&D) costs and the turnover (concerning 2015).

TAX_PAID: the effective tax rate is the ratio between tax expenses and earnings before interest and taxes.

ETH_COUNTRY: the scores about this variable range from 1 to 7, with 1 indicating a very low level of country ethics and 7 indicating a very high level of country ethics.

WOM_BOARD: this variable measures the proportion of women that are present in the boards of directors.

LEG_SYST: the legal system works as a binary variable, which numbers 1 if the company belongs to the Anglo-Saxon legal system (globally recognized as stricter), and 0 otherwise.

LEVE: the level of indebtedness is the ratio between long- and medium-term debts and total assets.

POL_SECTOR: the pollutant sector works as a binary variable, which numbers 1 if the company belongs to the polluting sectors (more regulated), and 0 otherwise.

3.3 Variables definition

To operationalize the hypotheses under test, all the variables that have been included in the empirical model are defined and commented as follows.

3.3.1 Dependent variable (“DISC_SCO”)

To measure this dimension, Li et al. (2008) have adopted a content analysis method, investigating the annual reports of selected companies to derive the qualitative, quantitative, financial as well as nonfinancial data relating to IC. In Table 4 the several components for human, structural and relational capital are reported.

In the current research, according to the measure used by Li et al. (2008) , cited also in Maaloul and Zeghal (2015) , the variable “DISC_SCO” has been adopted as a proxy of IC-VD, concerning published items about IC. Based on the examination of the annual reports, this dimension appraises the disclosed information on IC.

3.3.2 Independent variables

As aforementioned, several categories of explanatory variables have been selected to test their combined effects on the VD of IC. In the empirical model under analysis, to test H1 and H2 , two explanatory variables are naturally the most relevant, namely, BE and CSR.

3.3.2.1 BE (“ETH_SCO”)

The ethical measurement has been differently implemented in different contexts because this concept is highly complex and relates to several nonmeasurable dimensions. In addition, several studies have recently operationalized this measure by various means, originating from several international organizations.

In this research, the Ethisphere Quotient developed by the Ethisphere Institute has been adopted to measure the BE of the firms, as result of an investigation that consists of a series of multiple-choice questions that count the company's ethical performance. It is a composite index based on the combination of several items, reflecting each company's level of ethical principles.

3.3.2.2 CSR (“CSR_INDEX”)

In the current study, this measure has been derived from Dias et al. (2017) , who have constructed a list of indicators for measuring the CSR associated practices. The construct involves 40 CSR indicators categorized into three CSR dimensions (5 economic, 15 environmental and 20 social), as shown in Table 5 , thus providing a global view on the CSR of each firm.

The choice of the 40 indicators has been influenced by the most widely adopted standards on CSR disclosure (CSRD), i.e. the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) Guidelines ( Bebbington et al. , 2008 ). Dias et al. (2017) have primarily focused on the GRI core indicators representing the well-established CSR indicators, and the selected items have been adapted to avoid penalizing companies that do not apply the GRI model.

CSR_INDEX = Level of CSR disclosure

e j = Attributed analysis (1 if the disclosure item is found, and 0 otherwise)

e = Maximum number of items a company can disclose (40).

3.3.3 The control variables: characteristics about the firm and the environment of the firm

BE and CSR are not the only factors that may influence the VD of IC. A control has been operated about other determinants of VD that have been documented in prior studies and that might explain the effects of financial and economic peculiarities of the firms on the scale and design of voluntary, and sometimes even mandatory, disclosure of IC ( Ribeiro Lucas and Costa Lourenço, 2014 ).

More specifically, control variables related to the characteristics of the firm are the following: the degree of innovation intensity (INVT), the effective tax rate (TAX_PAID), the percentage women on board of directors (WOM_BOARD), the leverage level (LEVE) and the pollutant sector (POL_SECTOR). Control variables related to the characteristics of the environment of the firm are the following: the level of country ethics (ETH_COUNTRY) and the legal system (LEG_SYST) because the sample includes several countries.

Generally, positive signs should be expected for INVT, WOM_BOARD, ETH_COUNTRY and LEG_SYST, whereas negative signs should be expected for LEVE, and POL_SECTOR, while no directional prediction is assumed for TAX_PAID. Finally, for an overall overview about the model variables composition, cf. Table 6 .

4. Empirical results and discussion

The current research, although engineered for testing specific hypotheses, has an explanatory purpose, aiming at identifying the potential determinants for the VD of the IC through ethical-and-social responsibility approach. As a result, a linear relationship could be established between the variable to be explained (IC-VD) and the potential explanatory variables (BE and CSR).

4.1 Descriptive analysis

Sections A and B, as figuring in Table 7 , provide the descriptive statistics characteristics concerning the continuous and dichotomous variables under investigation. Section A depicts mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum relevant to the continuous variables, whereas Section B provides the frequency of the dichotomous variables; globally speaking, the sample seems to be evenly distributed.

Starting with the analysis of Section A in Table 7 , the descriptive analysis provides evidence that the mean level of IC-VD (DISC_SCO) is 0.59; this score is high with respect to the Maaloul and Zeghal (2015) reached index (0.46), relevant to a sample of US companies in 2013. Moreover, the current sample encloses firms that should also tend to improve their informational capacity related to IC.

The BE score (ETH_SCO) has a mean value of 0.608. Most companies in the sample tend to be more involved in BE activities.

The CSR scores range from a minimum of 0.15 to a maximum of 0.95, with a mean of 0.698. A higher CSR score denotes that the company displays a better CSR performance ( Hassan and Guo, 2017 ).

As regards the control variables, the following considerations may arise. The intensity of innovation (INVT) displays an average of 0.068, with a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 0.745; whereas the mean level of debt (LEVE) scores 33.3 (that seems an appreciable level of indebtedness), and the effective tax rate (TAX_PAID) exhibits an average of 0.166.

Regarding women's percentage on directors' boards (WOM_BOARD), it has been discovered that, on average, 0.223 of board members are female, with a minimum and a maximum value of 0.10 and 0.429, respectively. Consequently, there is predominance of men in the boards of directors.

As concerns the measure of the level of the country ethics (ETH_COUNTRY), Finland (6.4), Denmark (6.2) and Japan (6) rank as the most ethical, while Spain (3.8), Canada (3.51) and South Korea (0) exhibit the lowest ethical values. This finding is very relevant, affecting the potential influence of the countries' ethical approach on the adoption of IC-VD policies on behalf of enterprises.

From the analysis of Section B in Table 7 , highlighting the binary variables related frequencies, as regards the legal system (LEG_SYST) most of the companies in the sample turn out to pertain to the Anglo-Saxon rules (55%). Additionally, concerning the pollutant sector variable (POL_SECTOR), 51% of the companies in the sample appears to belong to nonpolluting sectors.

4.2 Correlations analysis

The Pearson coefficients were computed to examine the associations between the independent variables. According to Gujarati (2004) , if the pair-wise comparison between two independent variables is over 0.8, serious multicollinearity exists.

The maximum pair-wise value in the current investigation is 0.2649 (cf. Table 8 ); thus, multicollinearity should not be a concern for the regression analysis. Nonetheless, the null hypothesis of autocorrelation can be accepted because the explanatory variables are weakly correlated with each other, indicating that autocorrelation is not a problem. Table 8 presents all the correlation coefficients between the various explanatory variables that have been adopted in the empirical model.

The intercorrelations for all the explanatory variables have been examined by applying the variance inflation factors (VIF) analysis, which revealed no sign of multicollinearity. In fact, the VIF values corresponding to all the independent variables ranged from 1.05 to 1.47, very far below the acceptable upper bound of 10 ( Hair et al. , 2006 ).

The VIF values have been reported for each regression to demonstrate the model stability. Finally, both tests suggest that the regression estimations are not degraded by the presence of multicollinearity.

4.3 Regression analysis

The empirical results reveal that 32.5% of the variation for the level of IC-VD is explained by BE, CSR and control-related variables (cf. Table 9 ). As per Fisher's ( F ) statistics, equal to 2.8, the model's reliability is confirmed at a significant threshold lower than 0.01, and consequently, we tend to reject the null hypothesis, and assume that regression has significant potential to exist.

As expected, the empirical findings, even though with not definitive statistical values, in accordance with the exploratory nature of the research, show some evidence about supporting the research hypotheses ( H1 and H2 ), as further analyzed in detail. Thus, it can be concluded that the model is statistically significant and somehow fruitful for exploring the phenomenon under investigation.

4.3.1 Empirical evidence on BE impacting IC-VD ( H1 )

This hypothesis has been assumed to verify whether the ethical behavior of the companies under analysis positively influences the level of VD of IC: examination of the statistical tests (beta coefficient, t -test and p -value) shows that this variable has a positive and significant effect on the VD of IC. Indeed, the study of causal relationships shows that the coefficient associated with the link between BE and IC-VD is positive (0.485) and statistically significant (the value of the associated t is 1.99 with p = 0.045), corroborating the hypothesis predictions ( H1 ).

It could be noted the existence of some similarity between these findings and those published by Wirth et al. (2016) . In addition, the results show that divergence of interests and information asymmetry are issues that hinder the success of the enterprise ( Rubinstein et al. , 2001 ); similarly, the rigidity of the corporate governance system could also prevent managers from disclosing information about IC.

The problems of moral hazard and adverse selection are obvious; nevertheless, the results found in this study show that the abovementioned risks are not constraints that prevent the company from disclosing information on IC. These results turn out to be in-line with those reported by Goel and Ramanathan (2014) .

As a further result, the company's commitment in the BE process is a trigger for improving VD of IC, corroborating the results found by Areal and Carvalho (2012) on a sample of the most ethical companies in the world, as these companies can have advantages over others because of three distinct effects, namely, culture, diversity and reputation. This attitude positively influences the level of IC-VD, suggesting for example that these companies may benefit from special protection in the event of a crisis.

4.3.2 Empirical evidence on CSR impacting IC-VD ( H2 )

This hypothesis has assumed that CSR has a positive influence on the level of VD of IC. The statistical tests analysis shows that this variable positively and statistically influences the VD of information.

The estimated coefficient of CSR_INDEX is positive and statistically significant (0.116, p < 0.01), meaning that CSR influences the VD of the IC. This corroborates the hypothesis predictions ( H2 ).

These results turn out to be in-line with those reported by Branco and Rodrigues (2008) and Dias et al. (2017) . In this respect, CSR is positively interpreted by the various stakeholders via its effect on the decisions made by the company's organs and on the cognitive and mental patterns of the managers as well as on the legitimacy of the decisions ( Fontana et al. , 2019 ).

Likewise, these results align perfectly with the conclusions about the legitimacy of the company's managers ( Bond et al. , 2016 ). Thus, in some cases, and more specifically those based on the postulates of the agency theory, the manager who engages in specific activities related to CSR seems to reduce asymmetric information adopting these actions.

Indeed, the current findings support the view suggesting that VD of information about IC is sustained by CSR, in a mutual influence. Nevertheless, the commitment of the company in the activities of social responsibility, also when impacting IC-VD, is an asset that improves the confidence of investors in the business in the long run ( Saeidi et al. , 2015 ).

These results show the potential existence of a link between CSR and socially responsible disclosure and therefore, the transparency of information. Indeed, as shown by Su (2014) , engagement in social responsibility is a form of commitment to sustainable development and integration into VD that is needed for the most innovative companies.

In addition, as indicated by Garcia-Sanchez et al. (2016) , the company's commitment to social responsibility activities may affect the level of VD and promote financial transparency. Therefore, engagement in social responsibility activities could be dominated by a strategy of transparency and reliability, which may have significant impact on IC-VD.

4.3.3 Complementary considerations

Regarding the control variables, not all the related coefficients show the expected signs. The degree of innovation intensity (INVT) is positively and significantly associated ( p < 0.1) with VD of IC: this finding suggests that the most innovative firms worldwide have adopted more VD practices about IC; in fact, innovative firms are often under greater pressure from the part of investors and financial analysts to disclose IC relating information.

In addition, the influence of pollutant sector (POL_SECTOR) turns out to be negatively and significantly correlated ( p < 0.1) with the IC-VD, as expected. Similar confirmation can be found also as concerns the ethical level of the country (ETH_COUNTRY), positively associated with IC-VD.

However, the legal system relevant to each country (LEG_SYST) seems to be involved in controlling the corporate transparency, but this variable appears to be negatively correlated and statistically significant ( p < 0.05) with IC-VD. Most probably, and differently from what expected, stricter legal system may stimulate in reinforcing potential conflicts of interest and information asymmetry.

Similarly, the percentage of women on boards of directors and the level of indebtedness present directions that are contrary to what expected. Globally speaking, these potential contradictions about the control variables estimations suggest caution and confirm the initial assumption about the exploratory nature of the research.

5. Theoretical and practical implications

The overall results of the research show some applicative potential. From a scientific point of view, essentially, the study helps highlighting the persistence of several connections associating corporate ethics and the extent of IC-VD, within a context characterized with a new tendency of the companies to be responsible in this respect. From a managerial point of view, furthermore, the current study can be useful to promote the implementation of BE and CSR-related strategies, enabling to protect majority or minority shareholders through an enhanced high-quality disclosure of IC.

Ethically, nevertheless, companies should allot greater engagement about the necessity and importance of transparent and reliable communication helping reflecting the firm's true image ( Mathuva et al. , 2017 ). In this respect, financial transparency constitutes a necessary condition for the effective promotion of a firm involved in ethical and socially responsible behaviors, and with this regard, several studies have acknowledged that global ethics, as engraved within the organizational culture, has a remarkable impact on the development of VD, and specifically on the various components of IC ( Luthan et al. , 2016 ).

For example, Rezaee et al. (2020) have stressed the promotion of ethical standards within the company to improve the quality of disclosed information. Indeed, it has been recently discovered that the companies envisaging to promote ethical behaviors are called upon to adopt a rather intensive disclosure policy regarding their IC characteristics: in other words, the quality of disclosed information about IC contributes to outline the social legitimacy ( Slack and Munz, 2016 ).

The quality of information disclosed about the company's IC as based on corporate ethics should necessarily help improving the confidence of the user of the information, while enhancing the firm's social legitimacy. In this context, Su (2014) has found that companies involved in stakeholders' ethical issues can gain a competitive advantage and higher performance attracting excellent employees, as concerns human capital, and enhancing the brand image, as concerns relational/social capital ( Pedrini, 2007 ).

The VD program is an organized process that abides by specific rules conforming to the company's social approach and the executive's behavior. In this respect, the agency theory helps only partially reflecting the reality of the company, as it outlooks other aspects of the business value, especially within the new context of the knowledge-based economy ( Long Kweh et al. , 2014 ).

More particularly, managers are representative agents that rationally respond to the firm's economic stakeholders and the control mechanisms/contractual motivations ( Bamber et al. , 2010 ). Yet, the enterprises' decision-makers are not interchangeable, and companies' actions are a reflection of the values, skills and cognitive competences of the human capital ( Rodriguez Perez and de Pablos, 2003 ); thus, as an organizational option, VD is rather potentially dependent on other considerations than on just the firm's environmental characteristics.

Moreover, the process of communication is complex, as it involves judgments and arbitrations that account for the various constraints relating to the environment of the company, and managers act on the basis of their personal interpretations of the strategic situations they encounter. These interpretations are therefore based also on the individual and organizational values that the manager enjoys ( López-González, 2019 ).

To this end, the theory of planned behavior has been considered as means whereby the disclosure decision about IC could be influenced by several attitudes about BE and CSR. Indeed, it helps understanding a certain behavior in individual's psychological processes, as subjected to various influences, particularly to ethical and social factors.

Like any other behavior, information disclosure about IC also rests on perceived opportunities as well as probable outcomes, as entirely based on managers' values and proper knowledge. Moreover, the generated and disseminated information highly depends on the capacity of the company's information systems not only in terms of quantity but also in terms of growth and ability to account for the needs issued by parties that are external to the company, along with other organisms' requests, ever more with respect to IC.

At even more practical level, the reached findings appear to provide effects for global regulators and policymakers intending to install social reporting standards. They may provide ground that institutional and/or cultural factors affect top management's social reporting behavior or ethical/social values more in general, influencing the quality of published information about IC.

6. Research limitations and future avenues

The study shows several constraints, and two seem quite relevant. First, the research sample corresponds to firms without homogeneous characteristics, especially with regard to their pertinence to two different legal systems (the selected sample encloses several countries with two distinct legal system assumptions), probably affecting the companies' behaviors in terms of VD (mandatorily for sure); for this reason, it seems very desirable to control more thoroughly the legal system's effect, for example, subdividing further research samples into subsamples on the basis of the legal system pertinence. Furthermore, it could be useful to implement a comparison of the investigated model between companies pertaining to civil law or common law, since the legal system directly influences the accounting system, and then, the quality of the financial information.

Second, this finding appears to demonstrate that VD depends highly on corporate culture rather than the respective countries' accounting culture: this should also highlight that IC-VD stands as a form of socially responsible behavior, or an outcome of ethical behavior regarding the entirety of partners, more than mere legal constraint. Thus, further research on cross-cultural management influence could be useful, along with longitudinal analyses that could support major reliability of the global research.

7. Conclusion

This study has explored the impact of BE and CSR on the process of IC-VD, concerning a sample including 83 of the most ethical companies in 2015 in the world. Among the research motivations, it is to highlight that very few empirical studies appear to demonstrate the persistence of a relationship between ethical and social approaches and IC-VD: attempting to fill such a noticeable gap, the current study has been conducted to investigate, empirically, the relationship binding both variables.

Findings support arguments that companies with ethical behaviors and socially responsible practices appear to be highly committed to VD about their IC. It could follow, therefore, that IC-VD can also be considered as a form of ethical and socially responsible behavior.

The results achieved in this research afford empirical evidence as to the extent of external disclosure practices in the global context, also considering ever more frequent interfirm networks, providing useful means for investors seeking profitable investment opportunities and for financial report users, acting as operative orientations of knowledge management and IC strategy ( Del Giudice and Maggioni, 2014 ). In this respect, an ethical behavior (structural capital), influenced by personal values (human capital), affects IC-VD and then, practically, also the relational/social capital of the organization.

Sample selection process

Note(s) : *, ** and *** represent significance at 0.1, 0.05 and 0.01, respectively

Source(s) : Authors' calculation

Ajzen , I. ( 1991 ), “ The theory of planned behavior ”, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes , Vol. 50 No. 2 , pp. 179 - 211 .

Al Maskati , M.M. and Hamdan , A.M.M. ( 2017 ), “ Corporate governance and voluntary disclosure: evidence from Bahrain ”, International Journal of Economics and Accounting , Vol. 8 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 28 .

Alves , H. , Rodrigues , A.M. and Canadas , N. ( 2012 ), “ Factors influencing the different categories of voluntary disclosure in annual reports: an analysis for Iberian Peninsula listed companies ”, Tékhne , Vol. 10 No. 1 , pp. 15 - 26 .

Alvino , F. , Di Vaio , A. , Hassan , R. and Palladino , R. ( 2020 ), “ Intellectual capital and sustainable development: a systematic literature review ”, Journal of Intellectual Capital , Vol. 22 No. 1 , pp. 76 - 94 .

Areal , N. and Carvalho , A. ( 2012 ), “ The financial performance of the world's most ethical companies: advantage in times of crisis ”, Working Paper , University of Minho School of Economics and Management , Braga , pp. 1 - 48 , doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2186088 .

Armitage , C.J. and Conner , M. ( 2001 ), “ Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: a meta, analytic review ”, British Journal of Social Psychology , Vol. 40 No. 4 , pp. 471 - 499 .

Aslam , S. , Ahmad , M. , Amin , S. , Usman , M. and Arif , S. ( 2018 ), “ The impact of corporate governance and intellectual capital on firm's performance and corporate social responsibility disclosure ”, Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences , Vol. 12 No. 1 , pp. 283 - 308 .

Bamber , L.S. , Jiang , J.X. and Wang , I.Y. ( 2010 ), “ What's my style? The influence of top managers on voluntary corporate financial disclosure ”, The Accounting Review , Vol. 85 No. 4 , pp. 1131 - 1162 .

Bamel , U.K. and Bamel , N. ( 2018 ), “ Organizational resources, KM process capability and strategic flexibility: a dynamic resource-capability perspective ”, Journal of Knowledge Management , Vol. 22 No. 7 , pp. 1555 - 1572 .

Bebbington , J. , Larrinaga , C. and Moneva , J.M. ( 2008 ), “ Corporate social reporting and reputation risk management ”, Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal , Vol. 21 No. 3 , pp. 337 - 361 .

Bellucci , M. , Marzi , G. , Orlando , B. and Ciampi , F. ( 2020 ), “ Journal of Intellectual Capital: a review of emerging themes and future trends ”, Journal of Intellectual Capital , Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print , pp. 1 - 24 , doi: 10.1108/JIC-10-2019-0239 .

Beretta , V. , Demartini , C. and Trucco , S. ( 2019 ), “ Does environmental, social and governance performance influence intellectual capital disclosure tone in integrated reporting? ”, Journal of Intellectual Capital , Vol. 20 No. 1 , pp. 100 - 124 .

Bhimani , A. ( 2008 ), “ Making corporate governance count: the fusion of ethics and economic rationality ”, Journal of Management and Governance , Vol. 12 No. 2 , pp. 135 - 147 .

Bond , A. , Pope , J. , Morrison-Saunders , A. and Retief , F. ( 2016 ), “ A game theory perspective on environmental assessment: what games are played and what does this tell us about decision making rationality and legitimacy? ”, Environmental Impact Assessment Review , Vol. 57 No. 2016 , pp. 187 - 194 .

Branco , M.C. and Rodrigues , L.L. ( 2008 ), “ Factors influencing social responsibility disclosure by Portuguese companies ”, Journal of Business Ethics , Vol. 83 No. 4 , pp. 685 - 701 .

Campanella , F. , Della Peruta , M.R. and Del Giudice , M. ( 2014 ), “ Creating conditions for innovative performance of science parks in Europe. How manage the intellectual capital for converting knowledge into organizational action ”, Journal of Intellectual Capital , Vol. 15 No. 4 , pp. 576 - 596 .

Chan , M.C. , Watson , J. and Woodliff , D. ( 2014 ), “ Corporate governance quality and CSR disclosures ”, Journal of Business Ethics , Vol. 125 No. 1 , pp. 59 - 73 .

Chen , E. and Gavious , I. ( 2015 ), “ Does CSR have different value implications for different shareholders? ”, Finance Research Letters , Vol. 14 , No. 2015 , pp. 29 - 35 .

Chung , H. , Judge , W.Q. and Li , Y.H. ( 2015 ), “ Voluntary disclosure, excess executive compensation, and firm value ”, Journal of Corporate Finance , Vol. 32 , No. 2015 , pp. 64 - 90 .

Coluccia , D. , D'Amico , E. , Fontana , S. and Solimene , S. ( 2017 ), “ A cross-cultural perspective of voluntary disclosure: Italian listed firms in the stakeholder global context ”, European Journal of International Management , Vol. 11 No. 4 , pp. 430 - 451 .

Corvino , A. , Caputo , F. , Pironti , M. , Doni , F. and Bianchi Martini , S. ( 2019 ), “ The moderating effect of firm size on relational capital and firm performance: evidence from Europe ”, Journal of Intellectual Capital , Vol. 20 No. 4 , pp. 510 - 532 .

Cruz-González , J. , López-Sáez , P. , Emilio Navas-López , J. and Delgado-Verde , M. ( 2014 ), “ Directions of external knowledge search: investigating their different impact on firm performance in high-technology industries ”, Journal of Knowledge Management , Vol. 18 No. 5 , pp. 847 - 866 .

Del Giudice , M. and Maggioni , V. ( 2014 ), “ Managerial practices and operative directions of knowledge management within inter-firm networks: a global view ”, Journal of Knowledge Management , Vol. 18 No. 5 , pp. 841 - 846 .

Devalle , A. , Rizzato , F. and Busso , D. ( 2016 ), “ Disclosure indexes and compliance with mandatory disclosure-The case of intangible assets in the Italian market ”, Advances in Accounting , Vol. 35 , No. 2016 , pp. 8 - 25 .

Dias , A. , Rodrigues , L.L. and Craig , R. ( 2017 ), “ Corporate governance effects on social responsibility disclosures ”, Australasian Accounting Business and Finance Journal , Vol. 11 No. 2 , pp. 3 - 22 .

Elkington , J. ( 1998 ), “ Accounting for the triple bottom line ”, Measuring Business Excellence , Vol. 2 No. 3 , pp. 18 - 22 .

Fama , E.F. and French , K.R. ( 1997 ), “ Industry costs of equity ”, Journal of Financial Economics , Vol. 43 No. 2 , pp. 153 - 193 .

Fassin , Y. , Van Rossem , A. and Buelens , M. ( 2011 ), “ Small-business owner-managers' perceptions of business ethics and CSR-related concepts ”, Journal of Business Ethics , Vol. 98 No. 3 , pp. 425 - 453 .

Ferreira , A.L. , Branco , M.C. and Moreira , J.A. ( 2012 ), “ Factors influencing intellectual capital disclosure by Portuguese companies ”, International Journal of Accounting and Financial Reporting , Vol. 2 No. 2 , p. 278 .

Fontana , S. , Coluccia , D. and Solimene , S. ( 2019 ), “ VAIC as a tool for measuring intangibles value in voluntary multi-stakeholder disclosure ”, Journal of the Knowledge Economy , Vol. 10 No. 4 , pp. 1679 - 1699 .

Fukukawa , K. , Balmer , J.M. and Gray , E.R. ( 2007 ), “ Mapping the interface between corporate identity, ethics and corporate social responsibility ”, Journal of Business Ethics , Vol. 76 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 5 .

Gangi , F. , Mustilli , M. and Varrone , N. ( 2019 ), “ The impact of corporate social responsibility (CSR) knowledge on corporate financial performance: evidence from the European banking industry ”, Journal of Knowledge Management , Vol. 23 No. 1 , pp. 110 - 134 .

Garcia-Sanchez , I.M. , Cuadrado-Ballesteros , B. and Frias-Aceituno , J.V. ( 2016 ), “ Impact of the institutional macro context on the voluntary disclosure of CSR information ”, Long Range Planning , Vol. 49 No. 1 , pp. 15 - 35 .

Giacosa , E. , Ferraris , A. and Bresciani , S. ( 2017 ), “ Exploring voluntary external disclosure of intellectual capital in listed companies: an integrated intellectual capital disclosure conceptual model ”, Journal of Intellectual Capital , Vol. 18 No. 1 , pp. 149 - 169 .

Goel , M. and Ramanathan , M.P.E. ( 2014 ), “ Business ethics and corporate social responsibility–is there a dividing line? ”, Procedia Economics and Finance , Vol. 11 , No. 2014 , pp. 49 - 59 .

Gray , R. , Kouhy , R. and Lavers , S. ( 1995 ), “ Corporate social and environmental reporting: a review of the literature and a longitudinal study of UK disclosure ”, Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal , Vol. 8 No. 2 , pp. 47 - 77 .

Gujarati , D.N. ( 2004 ), Basic Econometrics , McGraw-Hill , New York, NY .

Guthrie , J. , Petty , R. and Ricceri , F. ( 2006 ), “ The voluntary reporting of intellectual capital: comparing evidence from Hong Kong and Australia ”, Journal of Intellectual Capital , Vol. 7 No. 2 , pp. 254 - 271 .

Hair , J. , Black , W. , Babin , B. , Anderson , R. and Tatham , R. ( 2006 ), Multivariate Data Analysis , Pearson Prentice Hall , Upper Saddle River, NJ .

Hamed , M.S. and Omri , M.A. ( 2014 ), “ Voluntary disclosure about innovation and technological choices by Tunisian listed companies ”, International Journal of Managerial and Financial Accounting , Vol. 5 No. 4 , pp. 379 - 390 .

Haniffa , R.M. and Cooke , T.E. ( 2005 ), “ The impact of culture and governance on corporate social reporting ”, Journal of Accounting and Public Policy , Vol. 24 No. 5 , pp. 391 - 430 .

Hassan , A. and Guo , X. ( 2017 ), “ The relationships between reporting format, environmental disclosure and environmental performance: an empirical study ”, Journal of Applied Accounting Research , Vol. 18 No. 4 , pp. 425 - 444 .

Hussi , T. ( 2004 ), “ Reconfiguring knowledge management – combining intellectual capital, intangible assets and knowledge creation ”, Journal of Knowledge Management , Vol. 8 No. 2 , pp. 36 - 52 .

Jo , J. , Park , J. and Cho , M. ( 2008 ), “ A study on the segment reporting of Korean firms ”, Korean Accounting Journal , Vol. 17 , No. 2008 , pp. 191 - 223 .

Khondkar , E.K. , Suh , S. and Tang , J. ( 2016 ), “ Do ethical firms create value? ”, Social Responsibility Journal , Vol. 12 No. 1 , pp. 54 - 68 .

Lehnert , K. , Craft , J. , Singh , N. and Park , Y.H. ( 2016 ), “ The human experience of ethics: a review of a decade of qualitative ethical decision making research ”, Business Ethics: A European Review , Vol. 25 No. 4 , pp. 498 - 537 .

Li , J. , Pike , R. and Haniffa , R. ( 2008 ), “ Intellectual capital disclosure and corporate governance structure in UK firms ”, Accounting and Business Research , Vol. 38 No. 2 , pp. 137 - 159 .

Lin , C.S. , Chang , R.Y. and Dang , V.T. ( 2015 ), “ An integrated model to explain how corporate social responsibility affects corporate financial performance ”, Sustainability , Vol. 7 No. 7 , pp. 8292 - 8311 .

López-González , E. , Martínez-Ferrero , J. and García-Meca , E. ( 2019 ), “ Corporate social responsibility in family firms: a contingency approach ”, Journal of Cleaner Production , Vol. 211 , No. 2019 , pp. 1044 - 1064 .

Long Kweh , Q. , Lu , W.-M. and Wang , W.-K. ( 2014 ), “ Dynamic efficiency: intellectual capital in the Chinese non-life insurance firms ”, Journal of Knowledge Management , Vol. 18 No. 5 , pp. 937 - 951 .

Luthan , E. , Asniati and Yohana , D. ( 2016 ), “ A correlation of CSR and intellectual capital, its implication toward company's value creation ”, International Journal of Business and Management Invention , Vol. 5 No. 11 , pp. 88 - 94 .

Maaloul , A. and Zeghal , D. ( 2015 ), “ Financial statement informativeness and intellectual capital disclosure: an empirical analysis ”, Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting , Vol. 13 No. 1 , pp. 66 - 90 .

Mathuva , D.M. , Mboya , J.K. and McFie , J.B. ( 2017 ), “ Achieving legitimacy through co-operative governance and social and environmental disclosure by credit unions in a developing country ”, Journal of Applied Accounting Research , Vol. 18 No. 2 , pp. 162 - 184 .

McPhail , K. ( 2009 ), “ Where is the ethical knowledge in the knowledge economy? Power and potential in the emergence of ethical knowledge as a component of intellectual capital ”, Critical Perspectives on Accounting , Vol. 20 No. 7 , pp. 804 - 822 .

Melloni , G. ( 2015 ), “ Intellectual capital disclosure in integrated reporting: an impression management analysis ”, Journal of Intellectual Capital , Vol. 16 No. 3 , pp. 661 - 680 .

Mouritsen , J. ( 2004 ), “ Measuring and intervening: how do we theorise intellectual capital management? ”, Journal of Intellectual Capital , Vol. 5 No. 2 , pp. 257 - 267 .

Mura , M. , Lettieri , E. , Spiller , N. and Radaelli , G. ( 2012 ), “ Intellectual capital and innovative work behaviour: opening the black box ”, International Journal of Engineering Business Management , Vol. 4 , No. 2012 , pp. 4 - 39 .

Murray , A. , Papa , A. , Cuozzo , B. and Russo , G. ( 2016 ), “ Evaluating the innovation of the internet of things ”, Business Process Management Journal , Vol. 22 No. 2 , pp. 1 - 21 .

Muttakin , M.B. , Khan , A. and Belal , A.R. ( 2015 ), “ Intellectual capital disclosures and corporate governance: an empirical examination ”, Advances in Accounting , Vol. 31 No. 2 , pp. 219 - 227 .

Nahapiet , J. and Ghoshal , S. ( 1998 ), “ Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage ”, Academy of Management Review , Vol. 23 No. 2 , pp. 242 - 266 .

Navid , B.J. , Pourmazaheri , M. and Amiri , M. ( 2015 ), “ The investigate of relationships between intellectual capital, performance and corporate social responsibility evidence from Tehran stock exchange ”, International Journal of Applied Business and Economic Research , Vol. 13 No. 6 , pp. 3983 - 3993 .

Ousama , A.A. and Fatima , A.H. ( 2012 ), “ Extent and trend of intellectual capital reporting in Malaysia: empirical evidence ”, International Journal of Managerial and Financial Accounting , Vol. 4 No. 2 , pp. 159 - 176 .

Passaro , R. , Quinto , I. and Thomas , A. ( 2018 ), “ The impact of higher education on entrepreneurial intention and human capital ”, Journal of Intellectual Capital , Vol. 19 No. 1 , pp. 135 - 156 .

Pedrini , M. ( 2007 ), “ Human capital convergences in intellectual capital and sustainability reports ”, Journal of Intellectual Capital , Vol. 8 No. 2 , pp. 346 - 366 .

Polo , F.C. and Vázquez , D.G. ( 2008 ), “ Social information within the intellectual capital report ”, Journal of International Management , Vol. 14 No. 4 , pp. 353 - 363 .

Porter , M.E. and Kramer , M.R. ( 2011 ), “ Creating shared value ”, Harvard Business Review , Vol. 89 Nos 1-2 , pp. 62 - 77 .

Rechberg , I. and Syed , J. ( 2013 ), “ Ethical issues in knowledge management: conflict of knowledge ownership ”, Journal of Knowledge Management , Vol. 17 No. 6 , pp. 828 - 847 .

Rezaee , Z. , Alipour , M. , Faraji , O. , Ghanbari , M. and Jamshidinavid , B. ( 2020 ), “ Environmental disclosure quality and risk: the moderating effect of corporate governance ”, Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal , Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print , pp. 1 - 34 , doi: 10.1108/SAMPJ-10-2018-0269 .

Ribeiro Lucas , S.M. and Costa Lourenço , I. ( 2014 ), “ The effect of firm and country characteristics on mandatory disclosure compliance ”, International Journal of Managerial and Financial Accounting , Vol. 6 No. 2 , pp. 87 - 116 .

Rodriguez Perez , J. and Ordóñez de Pablos , P. ( 2003 ), “ Knowledge management and organizational competitiveness: a framework for human capital analysis ”, Journal of Knowledge Management , Vol. 7 No. 3 , pp. 82 - 91 .

Rubinstein , J.S. , Meyer , D.E. and Evans , J.E. ( 2001 ), “ Executive control of cognitive processes in task switching ”, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance , Vol. 27 No. 4 , pp. 763 - 797 .

Saeidi , S.P. , Sofian , S. , Saeidi , P. , Saeidi , S.P. and Saaeidi , S.A. ( 2015 ), “ How does corporate social responsibility contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of competitive advantage, reputation, and customer satisfaction ”, Journal of Business Research , Vol. 68 No. 2 , pp. 341 - 350 .

Serenko , A. and Bontis , N. ( 2013 ), “ The intellectual core and impact of the knowledge management academic discipline ”, Journal of Knowledge Management , Vol. 17 No. 1 , pp. 137 - 155 .

Singh , S.K. and Gaur , S.S. ( 2020 ), “ Corporate growth, sustainability and business ethics in twenty-first century ”, Journal of Management and Governance , Vol. 24 , No. 2020 , pp. 303 - 305 .

Slack , R. and Munz , M. ( 2016 ), “ Intellectual capital reporting, leadership and strategic change ”, Journal of Applied Accounting Research , Vol. 17 No. 1 , pp. 61 - 83 .

Su , H.Y. ( 2014 ), “ Business ethics and the development of intellectual capital ”, Journal of Business Ethics , Vol. 119 No. 1 , pp. 87 - 98 .

Sun , N. , Salama , A. , Hussainey , K. and Habbash , M. ( 2010 ), “ Corporate environmental disclosure, corporate governance and earnings management ”, Managerial Auditing Journal , Vol. 25 No. 7 , pp. 679 - 700 .

Ting , I.W.K. , Ren , C. , Chen , F.-C. and Kweh , Q.L. ( 2020 ), “ Interpreting the dynamic performance effect of intellectual capital through a value-added-based perspective ”, Journal of Intellectual Capital , Vol. 21 No. 3 , pp. 381 - 401 .

Türkel , S. , Uzunoğlu , E. , Kaplan , M.D. and Vural , B.A. ( 2016 ), “ A strategic approach to CSR communication: examining the impact of brand familiarity on consumer responses ”, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management , Vol. 23 No. 4 , pp. 228 - 242 .

Vaz , C.R. , Selig , P.M. and Viegas , C.V. ( 2019 ), “ A proposal of intellectual capital maturity model (ICMM) evaluation ”, Journal of Intellectual Capital , Vol. 20 No. 2 , pp. 208 - 234 .

Vrontis , D. , Christofi , M. , Battisti , E. and Graziano , E.A. ( 2020 ), “ Intellectual capital, knowledge sharing and equity crowdfunding ”, Journal of Intellectual Capital , Vol. 22 No. 1 , pp. 95 - 121 .

Wirth , H. , Kulczycka , J. , Hausner , J. and Koński , M. ( 2016 ), “ Corporate Social Responsibility: communication about social and environmental disclosure by large and small copper mining companies ”, Resources Policy , Vol. 49 , No. 2016 , pp. 53 - 60 .

Zhang , Y. , Wang , T. and Hsu , C. ( 2019 ), “ The effects of voluntary GDPR adoption and the readability of privacy statements on customers' information disclosure intention and trust ”, Journal of Intellectual Capital , Vol. 21 No. 2 , pp. 145 - 163 .

businesswire.com .

ethisphere.com .

weforum.org .

worldbank.org .

worldsmostethicalcompanies.com .

Acknowledgements

The article is based on the study funded by the Basic Research Program of the National Research University Higher School of Economics (HSE) and by the Russian Academic Excellence Project “5-100”.

Corresponding author

About the authors.

Matteo Rossi is an Associate Professor of Corporate Finance at the University of Sannio, Benevento, Italy, where he received the PhD degree in Management. He is also an Adjunct Professor of Advanced Corporate Finance at LUISS, Rome, Italy. Dr Rossi is the Editor-in-Chief for the International Journal of Managerial and Financial Accounting and for the International Journal of Behavioral Accounting and Finance.

Giuseppe Festa is an Associate Professor of Management at the Department of Economics and Statistics of the University of Salerno, Italy, EU. He holds a PhD in Economics and Management of Public Organizations from the University of Salerno, where he is the Scientific Director of the Postgraduate course in Wine Business and the Vice-Director of the Second Level Master's in Management of Healthcare Organizations – Daosan. He is also the Chairman of the Euromed Research Interest Committee on Wine Business. His research interests focus mainly on wine business, information systems and healthcare management.

Salim Chouaibi is a PhD Student in Accounting at the Faculty of Economic Sciences and Management of the University of Sfax (Tunisia).

Monica Fait is an Assistant Professor of Management at the Department of Management Economics Mathematics and Statistics of the University of Salento, Lecce (Italy), where she teaches Business Economics and Management. Her research looks at the effects of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) on company behavior, knowledge sharing and sustainability. She is the author of several scientific publications and papers on the Web 2.0 marketing strategies, and her studies have been published on international journals like Technological Forecasting and Social Change , Journal of Knowledge Management and British Food Journal . She also serves as reviewer for several international journals and is a speaker at national and international conferences and industry forums.

Armando Papa is an Associate Professor of Management at the Faculty of Communication Sciences of the University of Teramo (Italy) and at the National Research University Higher School of Economics (HSE) of Moscow (Russian Federation). He received the postgraduate master's degree in corporate finance from IPE (Naples, Italy) and the PhD degree in management from the “Federico II” University of Naples. He is an Associate Editor for the Journal of Knowledge Economy (Springer) and an Editorial Assistant for the Journal of Knowledge Management (Emerald).

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 26 April 2023

Exploring the factors affecting the implementation of corporate social responsibility from a strategic perspective

- Chao-Chan Wu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3891-310X 1 ,

- Fei-Chun Cheng 2 &

- Dong-Yu Sheh 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 179 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

2 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Business and management

In general, the objective of a company is to pursue higher returns for its shareholders. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is an ethical practice that seems to be contrary to the objectives of companies; as a result, companies lack sufficient motivation to implement CSR. Academics and practitioners have recently begun considering CSR from a strategic perspective. However, the definition and scope of strategic CSR have not been clearly defined or discussed in previous studies. This study uses the strategic triangle perspective as a theoretical basis to explore the key factors affecting the implementation of strategic CSR. Three main factors and ten sub-factors were summarized to form a hierarchical network structure based on a literature review. The weights of each factor and sub-factor were then prioritized using the analytic network process (ANP). The results of this study show that “company” is the most important main factor, while “corporate image”, “innovation ability”, “reputation risk”, “financial capacity”, and “investment intention” are the top five important sub-factors. The hierarchical network structure and critical factors suggested in this study contribute to implementing strategic CSR. The findings of this study will also help the theoretical development in the field of CSR.

Similar content being viewed by others

A cross-verified database of notable people, 3500BC-2018AD

Morgane Laouenan, Palaash Bhargava, … Etienne Wasmer

Ethics and discrimination in artificial intelligence-enabled recruitment practices

Zhisheng Chen

The role of artificial intelligence in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals

Ricardo Vinuesa, Hossein Azizpour, … Francesco Fuso Nerini

Introduction

The purpose of businesses is to produce products or services that meet consumer demand. However, with the depletion of resources and environmental pollution, people have gradually realized the importance of sustainable development. Furthermore, with better living standards, people pay attention to social issues such as health and human rights. Various factors have led to higher expectations regarding the role of businesses in society (Huang, 2014 ). In addition to their growth, companies need to consider the overall well-being of society and make moral contributions beyond economic and legal aspects. Enterprises are not only economic entities that operate for profit but also exist to create an ideal society (Carroll and Shabana, 2010 ). Therefore, corporate social responsibility (CSR) has become an important research topic in recent years (Yuan et al., 2020 ).

The motivation for CSR implementation changes with the social environment (Bergquist, 2017 ). The goal of an enterprise is to make profits and maximize shareholder value. Thus, it is necessary to establish formal regulations to enforce the implementation of environmental protection and social issues by enterprises. Nevertheless, if CSR is merely a response to legal requirements, companies will not realize the value and benefits of this action. For organizations such as businesses that pursue economic benefits, implementing CSR may be viewed as a cost. This reactive motivation prevents companies from effectively implementing CSR (Bansal, 2022 ).

Social responsibility and corporate benefits do not conflict. This means that companies should not treat CSR as an expense incurred by contributions to fulfill public interest. Instead, companies should transform CSR from an ethical practice to one of their strategies (Porter and Kramer, 2006 ). If CSR is combined with a company’s strengths and strategies, its potential will maximize the benefits to society and the company (Branco and Rodrigues, 2006 ; Yuan et al., 2020 ). A strategic vision of CSR will allow companies to avoid seeing it as a cost or expense when implementing CSR, but will instead consider the relationship between CSR and the company’s core business and how to help the company achieve its strategic goals (Lepoutre and Heene, 2006 ; Manasakis, 2018 ). Strategic CSR can help companies achieve a win-win situation regarding economic benefits and social responsibility.

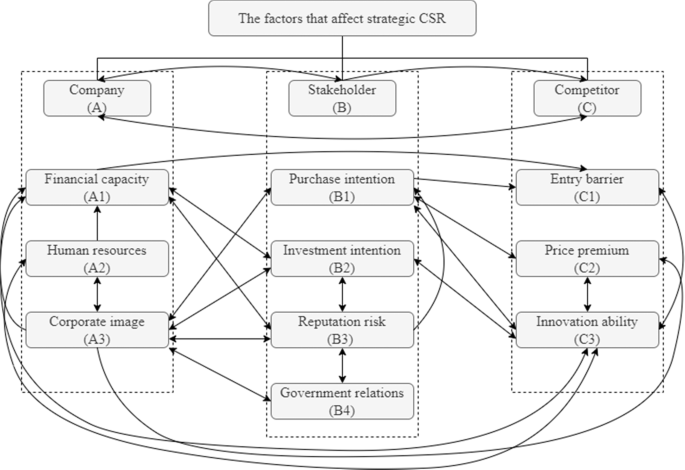

To implement strategic CSR, companies must identify the capabilities and resources that influence their social responsibility (Branco and Rodrigues, 2006 ). In addition, resources are limited to businesses, so selection and prioritization are important parts of strategic thinking (Porter, 2008 ). Identifying the key factors affecting the implementation of strategic CSR and recognizing the relative importance of these factors will help companies plan their strategic CSR activities. Therefore, it is important to explore the key factors that influence the implementation of strategic CSR. According to the strategic triangle perspective proposed by Ohmae ( 1982 ), the strategic thinking of a business is mainly based on company, customer, and competitor aspects. From the company aspect, the main description is the importance of internal resources in implementing a strategy. The customer aspect focuses on how a company uses its resources to provide attractive products and services to satisfy its customers. The principle of the competitor aspect is that a company should create as much competitive advantage as possible to enable it to compete with its competitors (Ohmae, 1982 ; van Vliet, 2009 ). The strategic triangle perspective can be used to develop a conceptual framework for strategic CSR.

This study aims to explore the key factors affecting the implementation of strategic CSR. Based on a literature review of the CSR concept and the strategic triangle perspective, this study identifies the main factors and sub-factors affecting the implementation of strategic CSR and establishes a hierarchical network structure for these factors. This study then uses the analytic network process (ANP) method to prioritize the relative weights of each factor and sub-factor in the hierarchical network structure. The results of this study contribute to determining the important factors that influence the implementation of strategic CSR to plan relevant strategies.

Literature review

This study examines the key factors influencing companies’ implementation of strategic CSR. In this section, we first review the general altruistic view of CSR. Second, the essence of corporate strategy was discussed within the framework of the strategic triangle. Then, we explain how to incorporate the strategic triangle perspective into the CSR concept to form strategic CSR. Finally, factors affecting the implementation of strategic CSR were selected to build a hierarchical network structure.

The concept of CSR

With the rise in sustainable development, CSR has become a popular topic. CSR means that enterprises are responsible for promoting social interests while pursuing their benefits (Carroll and Shabana, 2010 ; Josiah and Akpuh, 2022 ). The concept of CSR is a company’s response to social welfare and its responsibility to stakeholders affected by its development (Chang et al., 2014 ). CSR is strongly related to customers, investors, the government, and other stakeholders. Companies with social responsibility balance the needs of the company and stakeholders when making decisions so that they can contribute to society and stakeholders while pursuing profits (Hopkins, 2012 ). CSR mainly focuses on the positive actions of enterprises on social and environmental issues while paying attention to the rights and interests of stakeholders. However, it is difficult to link the ethical behavior of these companies to their own operations (Sheh, 2022 ). The traditional concept of CSR focuses on public interest but ignores the necessity of continuous profitability of companies (Matytsin et al., 2023 ). Companies must learn to integrate CSR actions into their operations rather than viewing CSR as additional philanthropy (Zollo, 2004 ). The current meaning of CSR is that companies must voluntarily incorporate social and environmental issues and interactions with stakeholders into their operations (Commission of the European Communities, 2001 ). Therefore, companies must consider both social responsibilities and operational performance, as well as their complementary strengths.

Strategic perspective and CSR

The purpose of strategy is to efficiently achieve the specific goal of an individual or organization, given the resources and capabilities. Strategic thinking integrates internal and external resources to achieve a competitive advantage in an uncertain and high-risk environment (Khalifa, 2020 ). In other words, the execution of strategy considers not only the current state within the company but also the situation of the external environment to choose the most appropriate way to achieve the goal (Hambrick and Fredrickson, 2005 ). Furthermore, Ohmae ( 1982 ) suggests a strategic triangle perspective and indicates that enterprises should focus on three factors when formulating their strategies, including the company, customer, and competitor. Companies must consider their own conditions and customer needs to provide products or services that are consistently better than those of their competitors and consider the interrelationships among the three factors.