Thoughts that breathe, and words that burn: poetic inquiry within health professions education

- A Qualitative Space

- Open access

- Published: 01 September 2021

- Volume 10 , pages 257–264, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Megan E. L. Brown ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9334-0922 1 , 2 ,

- Martina Kelly ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8763-7092 3 &

- Gabrielle M. Finn ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0419-694X 1 , 4

4256 Accesses

7 Citations

9 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

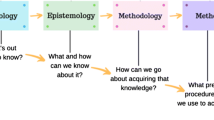

Qualitative inquiry is increasingly popular in health professions education, and there has been a move to solidify processes of analysis to demystify the practice and increase rigour. Whilst important, being bound too heavily by methodological processes potentially represses the imaginative creativity of qualitative expression and interpretation—traditional cornerstones of the approach. Rigid adherence to analytic steps risks leaving no time or space for moments of ‘wonder’ or emotional responses which facilitate rich engagement. Poetic inquiry, defined as research which uses poetry ‘as, in, [or] for inquiry’, offers ways to encourage creativity and deep engagement with qualitative data within health professions education. Poetic inquiry attends carefully to participant language, can deepen researcher reflexivity, may increase the emotive impact of research, and promotes an efficiency of qualitative expression through the use of ‘razor sharp’ language. This A Qualitative Space paper introduces the approach by outlining how it may be applied to inquiry within health professions education. Approaches to engaging with poetic inquiry are discussed and illustrated using examples from the field’s scholarship. Finally, recommendations for interested researchers on how to engage with poetic inquiry are made, including suggestions as to how to poetize existing qualitative research practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis

David Byrne

How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others

Brian E. Neubauer, Catherine T. Witkop & Lara Varpio

A Medical Science Educator’s Guide to Selecting a Research Paradigm: Building a Basis for Better Research

Megan E.L. Brown & Angelique N. Dueñas

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A Qualitative Space highlights research approaches that push readers and scholars deeper into qualitative methods and methodologies. Contributors to A Qualitative Space may: advance new ideas about qualitative methodologies, methods, and/or techniques; debate current and historical trends in qualitative research; craft and share nuanced reflections on how data collection methods should be revised or modified; reflect on the epistemological bases of qualitative research; or argue that some qualitative practices should end. Share your thoughts on Twitter using the hashtag: #aqualspace.

Introduction

“Poetry is thoughts that breathe, and words that burn” Thomas Gray

Poetry is a vehicle for human meaning making. It is part of everyday life which, if you look, you’ll find in advertisements, music, even sports cheers. It is not a modern fascination—indeed, poetry likely predates written text [ 1 ]. Before humans documented their experiences in a written format, poetry was an integral part of communities’ oral cultures, used to pass knowledge, history, and stories between generations [ 2 ]. Poems condense human experience, and when this experience speaks to you in some way, poetry feels meaningful and important [ 3 ]. Given the innate resonance of poetry to the human condition, poems feature within higher education, too. Within health professions education (HPE), poems have been most typically integrated into curricula within medical humanities modules as a way of centering patient narratives, engendering empathy amongst trainees, and facilitating reflective practice [ 4 , 5 , 6 ]. Several medical and medical humanities journals publish authors’ poems as arts contributions, demonstrating an appetite for poetry as a creative outlet in HPE. Yet, despite the pertinence of poetry to human experience, poetry as a form of research has not been a central topic of HPE conversation. In this article we introduce readers to poetic inquiry and its potential to expand qualitative research within HPE. We start by offering a broad definition of poetic inquiry, consider why it is both necessary and well suited to the field, and situate our exploration within phenomenology. We then progress to outline some approaches to engaging with poetic inquiry and illustrate these approaches using examples from HPE scholarship. Finally, we invite interested readers to consider ways in which they could engage with poetic inquiry, or to consider ways in which they could poetize their existing qualitative research practices.

What is poetic inquiry?

Poetic inquiry is an arts-based research methodology which treats poetry as a ‘vital way to express and learn’ by incorporating original poetry into academic research [ 7 , 8 ]. Though there is no consensus definition, ‘the key feature of poetic inquiry is the use of poetry as, in , [or] for inquiry’ [ 9 ], with poetic inquiry employed in diverse ways by researchers to collect data, collect field notes, and represent and reinterpret data [ 7 ]. The approach is gaining traction in many social science disciplines, including sociology, psychology, anthropology, and education [ 10 ]. Reasons for the use of poetic inquiry include preservation of participant voice [ 7 ], to explore the relationship between language and meaning [ 11 , 12 ], to deepen researcher reflexivity [ 13 ], and to increase the emotive impact and accessibility of academic research [ 14 ] as poetic inquiry can help both researchers and audiences engage more deeply with participant accounts [ 15 ]. Additionally, through its attention to language, poetic inquiry is a rigorous approach—it allows ‘thoughts [to] breathe’—whilst also promoting an emotive efficiency of qualitative expression which helps ‘words [to] burn’. Yet, despite the benefits poetic inquiry can offer qualitative research, it has not received the same degree of focus or enthusiasm within HPE.

Why do we need poetic inquiry?

Creative deviation from specific analytic qualitative processes is not the norm within HPE. Though approaches such as phenomenology, which seeks to represent the rich and complex nature of participants’ lived experiences [ 16 ], are becoming increasingly important within HPE, there has been a move to solidify processes of analysis to demystify the practice, and so increase rigor [ 17 ]. Whilst an important consideration, we believe the pendulum of data analysis is in danger of swinging too far—from openness to fixity—and qualitative research is at risk of stagnating. Several scholars have noted that qualitative inquiry often tends towards the descriptive, with deep thought regarding the connections between data, and the meaning of these connections wanting [ 17 , 18 ]. Such deep thought is necessary for approaches which seek to represent the complexity of experiences, such as within interpretative phenomenology [ 19 ]. Others have argued that servile adherence to one’s data through a rigid set of analytic steps leaves no time or space for moments of ‘wonder’, surprise, or the emotional responses of the researcher that facilitate rich engagement and interpretation [ 20 , 21 , 22 ]. Being bound too heavily by methodological processes represses the imaginative creativity of qualitative expression and interpretation that has traditionally been a cornerstone of the approach [ 23 , 24 ]. As we amass increasing levels of knowledge regarding topics such as professional identity formation within HPE, rich, creative qualitative exploration is necessary to advance scholarship in the field and expand understanding regarding the nuances of the process. New ways of scrutinizing old problems may also help further knowledge [ 25 ]. We propose that poetry through the medium of poetic inquiry may offer one way in which to restore creativity and deep engagement with qualitative data to qualitative inquiry within medical education.

Poetic inquiry as part of phenomenological inquiry

As an approach, poetic inquiry is broad and diverse. Scholars have situated their engagement with poetic inquiry within a variety of different qualitative traditions such as phenomenology [ 26 ], participatory action research [ 27 ], ethnography [ 28 ], narrative inquiry [ 29 ] and performative inquiry [ 30 ]. We suggest that, within HPE research, poetic inquiry finds a natural home as part approach of phenomenology.

Indeed, poetry is essential to phenomenological thought [ 31 ]. For Heidegger, thinking is something which only occurs in the company of, or with poetry [ 32 ], Van Manen refers to phenomenology itself as a ‘poetizing project’ [ 26 ], whilst Bachelard used poetry to consider the meaning and impact of physical spaces [ 33 ]. As researchers immerse themselves in the construction of poetry from data, they open themselves to ‘what is said, or more accurately to what is unsaid’ [ 32 ], a necessary condition to unconcealing phenomena which, for interpretative phenomenologists like Heidegger, is synonymous with truth [ 34 , 35 ]. As Galvin and Todres surmise, ‘poetic language emphasizes ‘wholeness’, in that, through rhythm, repetition, and imagery, a wholeness is pointed to that is more than what is there’ [ 36 ]. In this way, poetic inquiry facilitates an openness to ‘the otherness of language’ [ 32 ], and acts as a way of thinking about one’s data in a way that engenders moments of wonder, and stimulates deep, analytical thought. Whilst at the heart of phenomenology is a commitment to represent experience ‘well’, all too often this is taken by medical educationalists as a mandate to retell events as they are reported by participants, instead of utilizing phenomenological inquiry to open a space of understanding . Phenomenological accounts are not always factual—they can, and often do, draw upon fictional accounts to create ‘anecdotes of experience’, which convey meaning that is hard to communicate using a language of facts [ 37 ]. Creating poems as part of phenomenological inquiry can be seen as a way of creating these ‘anecdotes of experience’. For Van Manen, the key requirement of an ‘anecdote of experience’ is that the experiential account—in the case of poetic inquiry, the poem—is plausible in its truth-value [ 37 ]. Good phenomenological writing means that the reader recognizes the plausibility of the experience, even if they have never personally experienced that moment or kind of event. This is referred to by Van Manen as ‘the phenomenological nod’, where the reader of an account nods in agreement as they read about the lived experience of others [ 38 ].

Poetic inquiry may also help combat the oversimplification of findings within phenomenological research, which Sass comments is a key danger of phenomenological study [ 39 ]. Phenomenologists must constantly strive against reductionist portrayal of their findings—as Kelly et al. posit ‘phenomenology seeks to represent human experience in all its complexity, rather than seeking to reduce, parse or operationalize it’ [ 40 ]; this can cause issues when scholars are faced with journal-mandated word counts for their qualitative research. Portraying one’s data as poetry is an efficient way of displaying results within a qualitative paper’s results section, without (if done carefully, as we will discuss below) succumbing to reductionism. The necessity of ‘razor sharp’ language in short poems can powerfully capture the human experience in fewer words than with traditional qualitative quote display [ 41 ]. As Tse suggests, poetic inquiry ‘works with rather than against the complexities of experience, which researchers are always mining for understanding that is not easily extrapolated’[ 42 ]; simply put, poetic inquiry efficiently communicates a study’s findings whilst conserving their complexity. Poetic inquiry may, therefore, go some way to countering the temptation of reductionism in regard to phenomenological research.

Given the alignment of poetic inquiry to hermeneutic (interpretative [ 43 ]) phenomenological traditions, and its potential to counteract some of the issues phenomenological researchers may encounter, poetic inquiry has been used within phenomenological inquiry within other branches of the academe [ 13 , 26 ]. Within HPE, poetic inquiry is similarly suited to use within a phenomenological approach.

Types of poetic inquiry

One can engage in poetic inquiry in many ways. Van Luyn et al. draw distinctions between participant-voiced poetry, autobiographical poetry, and research poetry [ 44 ]. These approaches to poetic inquiry are summarized in Tab. 1 . In sum, participant-voiced poetry (sometimes referred to as ‘vox participare [ 10 ]’, ‘found poetry’ [ 11 ] or ‘data poetry’[ 45 ]) is the practice of creating a poem ‘solely from primary sources’ such as interview transcripts or written reflections [ 46 ]. The researcher shapes a participant’s words, ‘re-present[ing]’ them in poetic form [ 47 ]. Autobiographical poetry (sometimes referred to as auto-ethnographic poetry [ 45 ], or ‘vox autobiographica [ 10 ]’) is what one might expect—the construction of autobiographical poems that explore the experience of the researcher, ‘in order to gain insight into a particular research process’ [ 44 , 48 ]. Research poetry (or ‘vox theoria [ 10 ]’), is sometimes classed as a subtype of autobiographical poetry. However, Van Luyn et al. class research poems as a distinct entity, drawing attention to the fact that they are literature-voiced poems, written specifically in response to literature or theory in a field [ 44 ]. Whilst they are created by a researcher, they are ‘not a direct expression of the researcher’s personal experience’ [ 44 ].

How to ‘do’ poetic inquiry

Van Luyn et al.’s review suggests that participant-voiced poetry is the most common form of poetic inquiry [ 44 ]. There can be significant variation within this approach. Whilst we aim to cast some light on possible ways of engaging in participant-voiced poetic inquiry, the approaches we outline are by no means comprehensive or singular and are not intended to act as a prescriptive ‘how-to guide’. We outline two approaches to participant-voiced poetry: 1) Glesne’s method of poetic transcription and 2) Gilligan et al.’s listening guide, drawing on examples from HPE to illustrate their use.

Glesne’s method of poetic transcription

We suggest Glesne’s popular approach to poetic transcription [ 49 ] may act as a springboard for HPE researchers interested in poetic inquiry, by making clear the process of abiding by clear inquiry principles. The first principle Glesne sets is that only the participant’s words may be used within her participant-voiced poems [ 49 ]. Additionally, the syntax (the grammatical structure of words and phrases within a sentence—in essence, the ordering of words) of a participant’s way of speaking should be persevered in the poems that are written. For example, though the phrases ‘the cat ran quickly’, ‘the cat quickly ran’, and ‘quickly, the cat ran’ technically convey the same meaning, their syntax differs, which emphasizes different words within the phrases and alters the voice of the sentence. Though Glesne allowed herself to ‘pull … phrases from anywhere in the transcript and juxtapose them’, they paid attention to the participant’s ‘speaking rhythm … [their] way of saying things’ and echoed this in their poems [ 49 ].

Practically speaking, Glesne’s process first involves coding and sorting, similarly to the start of many qualitative research analyses. Major themes are then generated to group clusters of codes. It is after this point that poetic writing starts—all data under one theme is re-read, and the researcher reflects on the meaning and connections within the theme. Participant words within these data are used to portray meanings and connections. As researchers begin to write, it may become apparent that themes require some re-ordering. As poems are crafted, connections between data may become apparent that previously were hidden. As such, codes may shift categories or require refinement to attend to these new connections. Finally, researchers edit the participant-voiced poems, ensuring they speak to the meaning and complexity of the data.

We offer an example from our own research to demonstrate how transcript data can become a poem. Drawing inspiration from Glesne’s principles of poetic transcription, we used only the participant’s own words, and words from within one transcript, to construct participant-voiced poems for newly qualified doctors who had recently crossed the threshold into clinical practice [ 50 ]. As Glesne recommends, we were attentive to participant syntax—during our re-readings we made detailed notes in the margins of each transcript concerning participant tone, emphasis, use of pauses, rhythm and syntax. We also reviewed each transcript for repeating words, phrases, and expressions. An example of our process is depicted within the Table S1 of the Electronic Supplementary Material, where one participant-voiced poem (‘Friends are everything’) is displayed alongside the section of original transcript from which it is drawn. Words and phrases utilized in the poem are underlined.

Gilligan et al.’s ‘Listening Guide’ method

Gilligan et al. developed the ‘Listening Guide’ method in 2003 as a way of paying particular focus to how participants talk about themselves (using their first person ‘voices’)[ 51 ]. This method involves creation of a type of participant-voiced poetry, which helps researchers consider participant identities and subjectivities [ 52 ]. The method encourages researchers to pay close attention to participant use of the personal pronoun ‘I’ and recommends the creation of ‘I-poems’ in the second phase of the listening method [ 52 ]. The steps of the listening guide method are detailed in Tab. 2 . Typically, I‑poems are utilized only in the data analysis phase of the listening guide method [ 52 ], though some authors have used them to display results [ 53 ]. For examples of I‑poems, we recommend interested authors review the following references [ 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 ].

It is important to clarify that participant-voiced poetic inquiry is, by nature, an inductive approach to data analysis. If researchers wish to use educational theory to inform their analysis of participant-voiced poems, we suggest they do so in a way which aligns with what Varpio et al. term a ‘subjectivist inductive’ orientation to theory and research, where researchers work ‘from data up to abstract conceptualizations’ [ 56 ]. One subjectivist inductive approach to theory, which Varpio et al. term ‘theory-informing inductive data analysis’ may be of particular use to authors interested in applying theory to the process of poetic inquiry. In this approach, researchers move from data to theory, starting out with the intent to ‘understand or explain a … phenomenon’, and later using theory as ‘an interpretative tool’ to make sense of created participant-voiced poems [ 56 ]. In their study of the experience of women who identify as lesbian, gay, or queer, Lambert uses Butler’s theory of passionate attachments to analyze a poem created from participant interview text, employing theory in such a ‘theory-informing inductive data analysis’ approach [ 57 ].

Though we have outlined two specific approaches to poetic inquiry, we encourage researchers to read widely, and to adapt the method of poetic inquiry they select to suit their context and study, if appropriate. Transparency of one’s methodological approach is key, and adaptors must ensure they adequately detail their process, and justify the steps they have taken. There is an ethical domain to participant-voiced poetry, and it is important that researchers define and hold themselves to a set of principles throughout the process of inquiry [ 58 ].

Poetizing HPE qualitative research

We envision that increasing participant-voiced poetry use within HPE research could add depth to research questions which concern how participants speak about, and perceive, themselves, others, and their experiences. Through inviting researchers to engage deeply with participant accounts, poetic inquiry within HPE is not just a tool, but a way of being that gives rise to the space for wonder, surprise, emotions and creative expression and interpretation.

Though the benefits of poetry may appeal, researchers may not wish, or have capacity to, dive head-first into the unknown waters of poetic inquiry. If this is the case, there are several ways in which one can engage in ‘methodological borrowing’ [ 59 ] to poetize more traditional qualitative research projects and develop as a poet gradually over time [ 60 ]. Reflexive and analytic journaling is common within qualitative research. Researchers could expand this practice to include poetic journaling, an approach where researchers begin to think poetically about their findings. No two poetic journals will look the same. Researchers may wish to read poetry, taking notes on impactful lines and phrases which make them think. Researchers may also begin to write poems about their data and position as a researcher, experimenting with participant phrases, their own thoughts, and poetic conventions like rhyme and form. Keeping a poetic journal may also help capture what the sociologist Mills terms ‘fringe thoughts’—ideas which are by-products of everyday life, and which we usually dismiss as ‘mental noise’ but can hold intellectual value relevant to data analysis and theorization, as they prompt us to think differently about our research [ 61 ]. Excerpts from poetic journals could also be included within research manuscripts to demonstrate the process of reflexive engagement researchers have undertaken throughout a project. Using Gilligan’s listening guide as part of one’s analysis, but not results representation, may help researchers begin to think poetically about their data, and develop their poetic ear, without fear of their poetic output being subject to wide scrutiny.

Considerations of quality

There is debate within the poetic inquiry community as to what qualifies one to use poetic inquiry, with some concluding that, to engage in poetic inquiry, one should be a published or formally trained poet in their own right [ 58 ]. Respectfully, we disagree. Though proponents may claim their views are to protect the reputation of poetry, and ensure quality inquiry, such views position poetry as an elitist pursuit which prevents the engagement of novice, but keen, would-be poetic researchers. Given the benefits of poetic inquiry, we join with Lahman and Richard in advocating for ‘good enough’ research poetry [ 62 ]. ‘Good enough’ poetry is the space between the belief that ‘any person may write poetry’ (we recognize you need a grounding in poetic inquiry, and an appreciation of the approach), and ‘the scholarly belied that in-depth training is needed’ [ 62 ].

This debate may leave you feeling uneasy. As health professions educators, we enjoy practical guidance. If you are wondering how you will know whether your poems are ‘good enough’, we suggest you turn to Sullivan’s 2009 architectural dimensions of a poem [ 63 ] for reassurance, which Pate has synthesized into a quality checklist [ 26 ] (summarized in Table S2 of the Electronic Supplementary Material). As previously, these are not the only markers of poetic quality, nor do we believe they should be used prescriptively. Sullivan’s dimensions interplay and exist as a complex web or nexus that influence the impact and resonance of a poem. We advise that where researchers wish to use this checklist, they frame it as a broad guide or reflexive tool to consider the steps taken within their own research projects carefully and critically. Additionally, as researchers open up the possibilities of the method, it may be beneficial to learn more about typical poetic conventions such as form, meter and rhyme to advance your craft—but this is no means a prerequisite, at least in our eyes, to the ability to produce ‘good enough’ participant-voiced poetry.

Concluding thoughts

Though qualitative research is increasingly valued, barriers still exist to the progression of qualitative research within HPE. Discussions of the quality of qualitative research have centered methodological rigor, an important concern, but one that has dominated conversation. The threat to qualitative creativity has been much less frequently discussed within HPE. Poetic inquiry has not been a central topic of conversation yet holds the potential to encourage researchers to think deeply and creatively about their findings. Poems emphasize language and may cast new light on areas of HPE where thinking has become narrowed. Poetic inquiry can foster increased researcher attention to reflexivity in a creative and contemplative way. Crucially, poetic inquiry can preserve participant voice within research reports, and may offer one way to represent experience more faithfully. Poetic inquiry has much to offer HPE, and we encourage researchers to take up the poetic mantle to diversify research within the field and cultivate creativity. For, to return to the words of the poet Thomas Grey, who would not wish their thoughts to breathe, and words to burn?

Foley J. How to read an oral poem. Chicago: University of Illinois Press; 2002.

Google Scholar

Havelock E. Review: the ancient art of oral poetry. Philos Rhetor. 1979;12:187–202.

Lacoue-Labarthe P. Poetry as experience. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 1999.

Wolters F, Wijnen-Meijer M. The role of poetry and prose in medical education: the pen as mighty as the scalpel? Perspect Med Educ. 2012;1:43–50.

Article Google Scholar

Muszkat M, Yehuda A, Moses S, Naparstek Y. Teaching empathy through poetry: a clinically based model. Med Educ. 2010;44:503.

Finn G, Brown M, Laughey W. Holding a mirror up to nature: the role of medical humanities in postgraduate primary care training. Educ Prim Care. 2021;32:73–7.

Vincent A. Is there a definition? Ruminating on poetic inquiry, strawberries and the continued growth of the field. Art Res Int Transdiscipl J. 2018;3:48–76.

Wu B. My poetic inquiry. Qual Inq. 2021;27:283–91.

Faulkner S. Poetic inquiry: craft, method and practice. New York: Routledge; 2019.

Book Google Scholar

Prendergast M. The phenomenon of poetry in research. “Poem is what?” Poetic inquiry in qualitative social science. In: Prendergast M, Leggo C, Sameshima P, editors. Poetic inquiry: vibrant voices in the social sciences. Rotterdam: Sense; 2009. pp. 19–21.

Chapter Google Scholar

Sjollema S, Hordyk S, Walsh C, Hanley J, Ives N. Found poetry – finding home: a qualitative study of homeless immigrant women. J Poet Ther. 2012;25:205–17.

Eisner E. The enlightened eye. New York: Macmillan; 1991.

Freeman M. “Between eye and eye stretches an interminable landscape”: the challenge of philosophical hermeneutics. Qual Inq. 2001;7:646–58.

Fitzpatrick E, Fitzpatrick K. What poetry does for us in education and research. In: Fitzpatrick E, Fitzpatrick K, editors. Poetry, method and education research: doing critical, decolonising and political inquiry. Oxon: Routledge; 2020.

Nichols T, Biederman D, Gringle M. Using research poetics “responsibly”: applications for health promotion research. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2014;35:5–20.

Schwandt T. Three epistemological stances for qualitative inquiry: interpretativism, hermeneutics and social constructionism. In: Denzin N, Lincoln Y, editors. The landscape of qualitative research: theories and issues. Thousand Oaks: SAGE; 2003. pp. 292–331.

Kiger M, Varpio L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE guide No. 131. Med Teach. 2020;42:846–54.

Vaismoradi M, Jones J, Turunen H, Snelgrove S. Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2016;6:100–10.

Neubauer B, Witkop C, Varpio L. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspect Med Educ. 2019;8:90–7.

MacLure M. Classification or wonder? Coding as an analytic practice in qualitative research. In: Coleman R, editor. Deleuze and research methodologies. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press; 2013. pp. 164–83.

MacLure M. The wonder of data. Cult Stud Crit Methodol. 2013;13:228–32.

Kleiman S. Phenomenology: to wonder and search for meanings. Nurse Res. 2004;11:7–19.

Janesick V. Intuition and creativity: a pas de deux for qualitative researchers. Qual Inq. 2001;7:531–40.

Bothe A, Andreatta R. Quantitative and qualitative research paradigms: thoughts on the quantity and the creativity of stuttering research. Adv Speech Lang Pathol. 2004;6:167–73.

Veen M, Cianciolo A. Problems no one looked for: philosophical expeditions into medical education. Teach Learn Med. 2020;32:337–44.

Pate J. Found poetry: poetizing and the ‘art’ of phenomenological inquiry. SAGE Res Methods Cases. 2014; https://doi.org/10.4135/978144627305013512954 .

Stapleton SR. Data analysis in participatory action research: using poetic inquiry to describe urban teacher marginalization. Action Res. 2021;19(2):449–71.

Rapport F, Hartill G. Making the case for poetic inquiry in health services research. In: Galvin KT, Prendergast M, editors. Poetic inquiry II – seeing, caring, understanding. Rotterdam: Brill Sense; 2016. pp. 211–26.

Öhlén J. Evocation of meaning through poetic condensation of narratives in empirical phenomenological inquiry into human suffering. Qual Health Res. 2003;13:557–66.

Wiebe N. Mennocostal musings: poetic inquiry and performance in narrative research. Forum Qual Soc Res. 2008;9(2):42.

Anderson T. Through phenomenology to sublime poetry: Martin Heidegger on the decisive relation between truth and art. Res Phenomenol. 1996;26:198–229.

Bruns G. Heidegger’s estrangements. Language, truth, and poetry in the later writings. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1989.

Freshwater D. The poetics of space: researching the concept of spatiality through relationality. Psychodyn Pract. 2005;11:177–87.

Heidegger M. Being and time. Albany: Suny Press; 2010.

Koskela J. Truth as unconcealment in Heidegger’s Being and Time. Minerva. 2012;16:116–28.

Galvin K, Todres L. Research based empathic knowledge for nursing: a translational strategy for disseminating phenomenological research findings to provide evidence for caring practice. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48:522–30.

Van Manen M. Philological methods: the vocative. Phenomenology of practice: meaning-giving methods in phenomenological research and writing. Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press; 2014. pp. 240–81.

Van Manen M. Researching the lived experience: human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. London: University of Western Ontario; 1997.

Sass L. Three dangers: phenomenological reflections on the psychotherapy of psychosis. Psychopathology. 2019;52:126–34.

Kelly M, Svrcek C, King N, Scherpbier A, Dornan T. Embodying empathy: a phenomenological study of physician touch. Med Educ. 2020;54:400–7.

Leavy P. Method meets art: arts-based research practice. New York: Guilford; 2020.

Tse V. A review of poetic inquiry: vibrant voices in the social sciences. Education. 2014;20:177–81.

Bynum W, Varpio L. When I say … hermeneutic phenomenology. Med Educ. 2017;52:252–3.

van Luyn A, Gair S, Saunders V. ‘Transcending the limits of logic’: poetic inquiry as a qualitative research method for working with vulnerable communities. In: Gair S, van Luyn A, editors. Sharing qualitative research: showing lived experience and community narratives. New York: Routledge; 2016. pp. 95–111.

Willis K, Bishop E. “Hope is that fiery feeling”: using poetry as data to explore the meanings of hope for young people. Forum Qual Soc Res. 2014;15:9.

Connelly K. ‘What body part do I need to sell?’: Poetic re-presentations of experiences of poverty and fear from low-income Australians receiving welfare benefits. Creat Approaches Res. 2010;3:16.

Gair S, Van Luyn A. Sharing qualitative research: showing lived experience and community narratives. New York: Routledge; 2016.

Furman R, Langer C, Davis C, Gallardo H, Kulkarni S. Expressive, research and reflective poetry as qualitative inquiry: a study of adolescent identity. Qual Res. 2007;7:301315.

Glesne C. That rare feeling: re-presenting research through poetic transcription. Qual Inq. 1997;3:202–21.

Brown ME, Proudfoot A, Mayat NM, Finn GM. A phenomenological study of new doctors’ transition to practice, utilising participant-voiced poetry. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2021; https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-021-10046-x .

Gilligan C, Spencer R, Weinberg M, Bertsch T. On the listening guide: a voice centred relational method. In: Camic PM, Rhodes JE, Yardley L, editors. Qualitative research in psychology: expanding perspectives in methodology and design. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. pp. 157–72.

Edwards R, Weller S. I‑poems as a method of qualitative interview data analysis: young people’s sense of self. London: SAGE; 2015.

Balmer D, Devlin M, Richards B. Understanding the relation between medical students’ collective and individual trajectories: an application of habitus. Perspect Med Educ. 2017;6:36–43.

Petrovic S, Lordly D, Brigham S, Delaney M. Learning to listen: an analysis of applying the listening guide to reflection papers. Int J Qual Methods. 2015;14:1609406915621402.

Gilligan C, Eddy J. Listening as a path to psychological discovery: an introduction to the listening guide. Perspect Med Educ. 2017;6:76–81.

Varpio L, Paradis E, Uijtdehaage S, Young M. The distinctions between theory, theoretical framework, and conceptual framework. Acad Med. 2020;95:989–94.

Lambert K. ‘Capturing’ queer lives and the poetics of social change. Continuum. 2016;30:576–86.

Owton H. Doing poetic inquiry. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2017.

Varpio L, Martimianakis M, Mylopoulos M. Qualitative research methodologies: embracing methodological borrowing, shifting and importing. In: Cleland J, Durning S, editors. Researching medical education. 1st ed. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley; 2015.

Cahnmann M. The craft, practice, and possibility of poetry in educational research. Educ Res. 2003;32:29–36.

Mills C. The sociological imagination. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000.

Lahman M, Richard V. Appropriated poetry. Qual Inq. 2013;20:344–55.

Sullivan A. Defining poetic occasion in inquiry: concreteness, voice, ambiguity, emotion, tension and associative logic. Poetic inquiry, vibrant voices in the social sciences. Rotterdam: Brill Sense; 2009. pp. 111–26.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Tim Dornan for his encouragement, and for suggesting they connect over their mutual love for poetry and phenomenology.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Health Professions Education Unit, Hull York Medical School, University of York, York, UK

Megan E. L. Brown & Gabrielle M. Finn

Medical Education Innovation and Research Centre, Imperial College London, London, UK

Megan E. L. Brown

Department of Family Medicine, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Martina Kelly

School of Medical Sciences, Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health, The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK

Gabrielle M. Finn

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Megan E. L. Brown .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

M.E. L. Brown, M. Kelly and G.M. Finn declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary Information

40037_2021_682_moesm1_esm.docx.

Supplementary table 1: Construction of a participant-voiced poem in our own research using Glesne’s method of poetic transcription. Supplementary table 2: Sullivan’s architectural dimensions of a poem, as synthesised into a quality checklist by Pate

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Brown, M.E.L., Kelly, M. & Finn, G.M. Thoughts that breathe, and words that burn: poetic inquiry within health professions education. Perspect Med Educ 10 , 257–264 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-021-00682-9

Download citation

Received : 30 November 2020

Revised : 16 July 2021

Accepted : 20 July 2021

Published : 01 September 2021

Issue Date : October 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-021-00682-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Poetic inquiry

- Qualitative research

- Phenomenology

- Health professions education

- Medical education

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Fordham Library News

The latest from the Fordham University Libraries

A Guide to Researching Poetry

By Jeannie Hoag, Reference and Assessment Librarian

Tips for Researching Poetry

Among many other delightful signs of spring, April brings us National Poetry Month. Springtime during a pandemic is a contradictory mix of delights and shadows –an imperfectly perfect opportunity for poetry.

This is the 25th year we’ve been graced with National Poetry Month . If you regularly recognize National Poetry Month, it might be a welcome reminder of normalcy. And if you’ve never celebrated this month but want to dip your toe into the waters of the poetry pond, you’ve chosen a great time to explore. Below, you will find a few tips to help you get started with poetry research. A proposal: keep it simple, and let subject terms do the hard work for you.

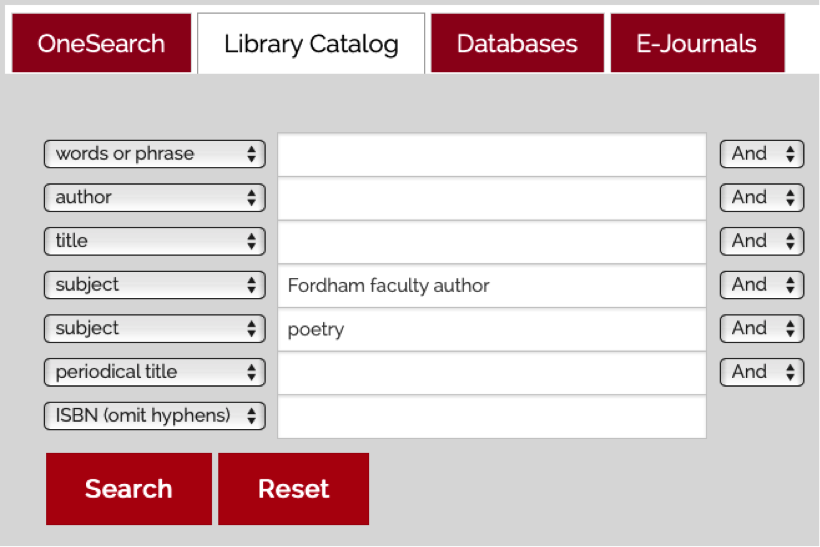

Tip #1: Start Local

First, let’s look at what’s happening on the local front. The library catalog makes it easy to identify works by Fordham faculty. Add in a few well-chosen limiters, and you can quickly pull together a list of books to dig into.

For example, by using the library catalog’s Advanced Search view, you can search using the subject terms “Fordham faculty author” and “poetry.” You’ll come away with a list of books of poetry, or books about poetry, by our very own faculty members. (This works for other topics, too.)

If you’re interested in exploring beyond Fordham, you can simply use the subject term “poetry” to find all the resources that are poetry-related. With over 35,000 results, that may be a bit overwhelming, so consider using some of these more specific subject terms:

- Narrative poetry

- Prose poems

- Modern poetry

- Jesuit poetry

And for focusing on poetry craft and technique, consider:

- Poetry authorship

- Poetry teaching

- Poetry criticism

If you’re able to visit the Walsh or Quinn libraries, might enjoy browsing by using this list of Library of Congress call numbers for Languages and Literatures . Some of the best discoveries come by way of serendipity. Even easier, pay a visit to the Poetry Room on the 3rd floor of Walsh Library, where you’ll find poetry spanning continents and centuries.

Tip #2: Get Specialized

Do you have a specific poetry need? Maybe a line has been zipping around, unidentified, all week. Or perhaps you’re officiating a wedding, dedicating a building, or tasked with making a public pronouncement that would benefit from a well-chosen poem.

Whatever your scenario, try Columbia Granger’s World of Poetry . This database provides a hearty amount of information, including the full text of some poems, author information, and subject indexing (497 poems about hair, 2 about haggis). It even notes applicable anthologies.

As with all our databases, you can locate Columbia Granger’s via the Databases tab on the library website. The advanced search option gives you maximum control, while the browse option is great for those who are just looking.

Tip #3: Expand Your Horizons

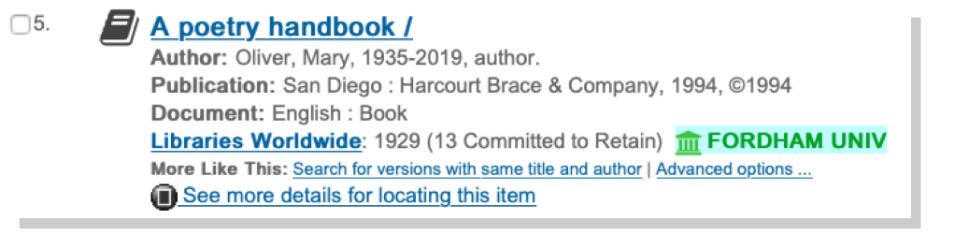

As you can see, the field of poetry is delightfully nuanced. If you’ve exhausted Fordham Libraries’ coverage of your area of interest, look globally to WorldCat .

WorldCat is a powerhouse “world catalog,” and is located on the library website under Resources .

Using the same Library of Congress subject terms you used in your library catalog search, you can see what’s available on your topic at libraries worldwide. For example, using the advanced search option in WorldCat, you can search for other books with the subject of poetry authorship.

In the results, books at Fordham are clearly labeled.

Find something interesting that’s not at Fordham? You can request it through ILLiad, our interlibrary loan service . And if it’s something you think Fordham should have, you can suggest it for purchase .

The Fordham Libraries has many excellent books and great databases for researching poetry. Whether you’re looking for literary criticism, biographies, or individual poems, we’ve got you covered. The Poetry research guide is full of recommended resources. Not finding what you’re looking for? Just ask a librarian. Our chat service is staffed 24/7, and you can also email our library liaisons directly.

More From the Blog

In Her Own Words: Memoirs, Essays, and Autobiographies Celebrating Women’s History Month

New Year, New You

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

A Defence of Poetry Study Guide

Related Papers

Maria Concetta Genova

Joann K Deiudicibus

On Shelley's theories of poetry and criticism, their place among his contemporaries et al, and a defense of his work in response to his critics. Note that I use the masculine pronoun he in this essay to be more succinct as I am writing mainly about male authors, although the larger concerns are those of any author.

KY Publication

Trisha Sengupta

The Romantic poets pursued the infinite and the invisible; they went beyond the limit of this phenomenal and nominal world in quest of absolute reality, or eternity. Also, it was the faculty of imagination, which was for them the gateway to the invisible and infinite worlds. They insisted that imagination, far from dealing with the fictitious and the non-existent, unravelled the mystery surrounding spiritual truths. They believed that when imagination was at work, it endowed one with a special insight to look beyond the surface and also enabled one to see things that intelligence could not reach. Shelley declared in his A Defence of Poetry that imagination was the highest faculty of man, and that the poet endowed with this faculty, possessed a special insight. This research paper does an analysis of one of P. B. Shelley's most influential works, A Defense of Poetry, reflecting that the main focus of poetry is to unveil the perfection of a world that is shrouded by darkness and uncertainty. To understand the significance of Shelley's essay, the paper outlines the critical line of thought on poetry back to its predecessors like Plato, who viewed poetry as blasphemous, and Aristotle, who considered poetry as a symbol of the eternal truth. The paper also explores the functions and responsibilities of poetry while elucidating the power of imaginative faculty.

Timothy Morton

Αθηνά Νακοπούλου

Subal Kinnar

The Keats-Shelley Review

Paul Whickman

Justin Keena

Composition and publication history, themes, analysis, and possible contexts of "Hymn to Intellectual Beauty," "Ozymandias," "Ode to the West Wind," and "The Cloud."

RELATED PAPERS

Fred Wright

Claes Annerstedt

psychoneuro

Wolfgang Retz

Micro-Macro-interaction

Thomas Böhlke

Studia Polonijne

Jerzy Grzybowski

Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Gabriel R Constantinescu

sunita panda

Muhammad Arsyad

Open Journal of Modern Linguistics

Anouar Smaoui

Journal of the Optical Society of America. A, Optics, image science, and vision

Mari Uusküla

Itzageri Pahuani Vera García

Astroparticle Physics

Salvatore Viola

Bertrand Gervais

Boletim do Centro de Pesquisa de Processamento de Alimentos

Tonye Waughon

American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology

Cristina Linde

Journal of Eating Disorders

Chia-Wei Fan

European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Imaging

Francesca Heilbron

Electronics

Melissa Mosquera

Angga Purnama

Irgy Saputra

Open Forum Infectious Diseases

Abdella Gemechu

Physical therapy in sport : official journal of the Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Sports Medicine

Leslie Nicholson

HAL (Le Centre pour la Communication Scientifique Directe)

Clara Jullien

Critical Finance Review

stylianos perrakis

Frontiers in Psychology

Kaisa Tiippana

See More Documents Like This

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Poetry & Poets

Explore the beauty of poetry – discover the poet within

How To Write A Poetry Research Paper

Introduction

Writing a poetry research paper can be an intimidating task for students. Even for experienced writers, the process of writing a research paper on poetry can be daunting. However, there are a few helpful tips and guidelines that can help make the process easier. Writing a research paper on poetry requires the student to have an analytical understanding of the poet or poet’s work and to utilize multiple sources of evidence in order to make a convincing argument. Before starting the research paper, it is important to properly analyze the poem and to understand the form, structure, and language of the poem.

The process of writing a research paper requires numerous steps, beginning with researching the poet and poem. If a poet is unknown, the research process must be started by learning about their biography, other works, and their impact on society. With online databases, libraries, and archives the research process can move quickly. It is important to carefully document sources for later use when creating bibliographies for the paper. Once the process of researching the poem has been completed, the next step is to analyze the poem itself. It is important for the student to read the poem carefully in order to understand the meaning, as well as its tone, imagery, and metaphors. Furthermore, analyzing other poems by the same poet can help students observe patterns, trends, or elements of a poet’s work.

Outlining and Structure

Outlining the research paper is just as important as analyzing the poem itself. Many students make the mistake of not taking enough time to craft a detailed outline that follows the structure of the paper. An effective outline will make process of writing the research paper more efficient, allowing for ease of transitions between sections of the paper. When writing the paper, it is important to think through the structure of the paper and how to make a strong argument. Support for the argument should be based on concrete evidence, such as literary criticism, literary theory, and close readings of the poem. It is essential to have a clear argument that is consistent throughout the body of the paper.

Citing Sources

When writing a research paper it is also important to cite all sources that are used. The style used for citing sources will depend on the style guide indicated by the professor or the school’s guidelines. Whether using MLA, APA, or Chicago style, it is important to adhere to the style guide indicated in order to have a complete and well-written paper.

Once the research and outlining is complete, the process of drafting a poetry research paper can begin. When constructing the first draft, it is especially useful to re-read the poem and to recall evidence that supports the argument made about the poem. Additionally, it is important to proofread and edit the first draft in order to make the argument more clear and to check for any grammar or spelling errors.

Writing a research paper on poetry does not have to be a difficult task. By taking the time to properly research, analyze, and structure the paper, the process of writing a successful poetry research paper becomes easier. Following these steps— researching the poet, understanding the poem itself, outlining the paper, citing sources, and drafting the paper— will ensure a great and thorough paper is prepared.

Using Imagery and Metaphor

The use of imagery and metaphor is an essential element when writing poetry. Imagery can be used to provide vivid descriptions of scenes and characters, while metaphor can be used to create deeper meanings and analogies. Understanding the use of imagery and metaphor can help to break down the poem and discover hidden meanings. Students researching poetry should pay special attentions to the poetic devices used to further the story or allusions to other works, such as classical mythology. Paying close attention to the language, metaphors, and imagery used by the poet can help to uncover the true meaning of the poem. By breaking down the element of the poem and focusing on individual elements, it is much easier to make valid conclusions about the poem and its author.

Understanding Rhyme and Meter

Rhyme and meter are two of the most important and complex elements of poetry. These two poetic techniques are used to help the poet structure their poem to provide rhythm and flow. Most commonly, rhyme and meter help to provide emphasis to certain words or phrases to give them additional meaning. When analyzing poetry, it is important to pay attention to the written rhyme schemes and meter of the poem. There are various patterns of rhyme, such as couplets, tercets, and quatrains. Meter, usually governed by iambs and trochees, can give the poem an added sense of rhythm to further emphasize certain words, phrases, or thoughts.

Exploring Themes

Themes are the central ideas behind a poem. The themes of a poem can be subtle and can be found in the language and images used. Exploring the poem through a thematic analysis can help to identify the true meaning of the poem and the message that the poet is conveying. When researching a poem, it is important to identify the primary theme of the poem and to look for evidence in the poem that can be used to support the claim. By paying attention to the language of a poem, students can uncover the deeper meanings within the poem and can move past the literal interpretation of the poem.

Analyzing Discourse and Context

In addition to the written aspects of a poem, it is important to consider the historical and social context of the poem. The context of the poem can be used to further understand its deeper meanings and implications. Collingwood’s theory of re-enactment can be used to reconstruct the context of a poem in order to gain a deeper understanding of the poem. When researching a poem, it is important to consider the the time period in which the poem was written, the author’s other works, and the broader literary context of the poem. Examining the discourse used by the poet can help to uncover the true message of the poem and the impact on society at the time.

Finding Inspiration

When researching poetry, it is important for the student to find inspiration in the form of other authors, critics, and theorists. Studying the works of other authors can provide valuable insight into a poem and can inform the student’s own interpretations. In addition to studying critics and theorists, the student should also look to other poets and authors as sources of inspiration. The student can explore the works of similar poets or authors to learn how they use their poetic elements in their work. This can help students to gain insight into the language, imagery, and themes present in the poem being researched.

Minnie Walters

Minnie Walters is a passionate writer and lover of poetry. She has a deep knowledge and appreciation for the work of famous poets such as William Wordsworth, Emily Dickinson, Robert Frost, and many more. She hopes you will also fall in love with poetry!

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

- Spartanburg Community College Library

- SCC Research Guides

ENG 102 - Poetry Research

- 4. Find Sources

Once you have narrowed your topic and thought about keywords, try searching the databases below for potential sources you can use to support your thesis. If your keywords aren't working ask a librarian for help!

Biographical Sources

Your research paper includes biographical information about the author. The literature databases will have some information, but also look for the author in the Gale in Context: Biography database. There are also several recommended books that include biographies on poets (see below).

Literary Criticism Sources

The following databases have lots of sources for poetry criticism. Begin your search by entering the name of the poem. If there are a lot of results, you can add the word "and," and then the theme you are researching.

- Poetry Criticism

Search for Books & eBooks

Use the search box below to search the SCC Library Catalog for physical books (in one of our library locations) and eBooks. You can also open the Library Catalog or use the Advanced Search for more search options.

- Open Library Catalog

- Advanced Search

Recommended Websites

- Academy of American Poets Hundreds of essays and interviews about poetry, biographies of more than 500 poets, over 1700 poems, and audio clips of one hundred and fifty poems read by their authors or other poets.

- Bartleby Contains thousands of poems, several poetry anthologies including the Oxford Book of English Verse.

- Contemporary American Poetry Archive An electronic archive designed to make out-of-print volumes of poetry available to readers, scholars, and researchers.

- Modern American Poetry A multi-media companion to the Anthology of Modern American Poetry. Contains poetry analysis of the works of over 160 poets.

- Representative Poetry Online Includes 3,162 English poems by 500 poets from Old English poets to the work of living poets today.

- American Verse Project An electronic archive of volumes of American poetry prior to 1920.

- << Previous: 3. Narrow Your Topic

- Next: 5. Cite Your Sources >>

- 1. Getting Started

- 2. Explore Your Topic

- 3. Narrow Your Topic

- 5. Cite Your Sources

- 6. Evaluate Your Sources

- 7. Write Your Paper

- Literary Criticism Guide

Questions? Ask a Librarian

- Last Updated: Mar 7, 2024 5:09 PM

- URL: https://libguides.sccsc.edu/Poetry

Giles Campus | 864.592.4764 | Toll Free 866.542.2779 | Contact Us

Copyright © 2024 Spartanburg Community College. All rights reserved.

Info for Library Staff | Guide Search

Return to SCC Website

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing About Poetry

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This section covers the basics of how to write about poetry, including why it is done, what you should know, and what you can write about.

Writing about poetry can be one of the most demanding tasks that many students face in a literature class. Poetry, by its very nature, makes demands on a writer who attempts to analyze it that other forms of literature do not. So how can you write a clear, confident, well-supported essay about poetry? This handout offers answers to some common questions about writing about poetry.

What's the Point?

In order to write effectively about poetry, one needs a clear idea of what the point of writing about poetry is. When you are assigned an analytical essay about a poem in an English class, the goal of the assignment is usually to argue a specific thesis about the poem, using your analysis of specific elements in the poem and how those elements relate to each other to support your thesis.

So why would your teacher give you such an assignment? What are the benefits of learning to write analytic essays about poetry? Several important reasons suggest themselves:

- To help you learn to make a text-based argument. That is, to help you to defend ideas based on a text that is available to you and other readers. This sharpens your reasoning skills by forcing you to formulate an interpretation of something someone else has written and to support that interpretation by providing logically valid reasons why someone else who has read the poem should agree with your argument. This isn't a skill that is just important in academics, by the way. Lawyers, politicians, and journalists often find that they need to make use of similar skills.

- To help you to understand what you are reading more fully. Nothing causes a person to make an extra effort to understand difficult material like the task of writing about it. Also, writing has a way of helping you to see things that you may have otherwise missed simply by causing you to think about how to frame your own analysis.

- To help you enjoy poetry more! This may sound unlikely, but one of the real pleasures of poetry is the opportunity to wrestle with the text and co-create meaning with the author. When you put together a well-constructed analysis of the poem, you are not only showing that you understand what is there, you are also contributing to an ongoing conversation about the poem. If your reading is convincing enough, everyone who has read your essay will get a little more out of the poem because of your analysis.

What Should I Know about Writing about Poetry?

Most importantly, you should realize that a paper that you write about a poem or poems is an argument. Make sure that you have something specific that you want to say about the poem that you are discussing. This specific argument that you want to make about the poem will be your thesis. You will support this thesis by drawing examples and evidence from the poem itself. In order to make a credible argument about the poem, you will want to analyze how the poem works—what genre the poem fits into, what its themes are, and what poetic techniques and figures of speech are used.

What Can I Write About?

Theme: One place to start when writing about poetry is to look at any significant themes that emerge in the poetry. Does the poetry deal with themes related to love, death, war, or peace? What other themes show up in the poem? Are there particular historical events that are mentioned in the poem? What are the most important concepts that are addressed in the poem?

Genre: What kind of poem are you looking at? Is it an epic (a long poem on a heroic subject)? Is it a sonnet (a brief poem, usually consisting of fourteen lines)? Is it an ode? A satire? An elegy? A lyric? Does it fit into a specific literary movement such as Modernism, Romanticism, Neoclassicism, or Renaissance poetry? This is another place where you may need to do some research in an introductory poetry text or encyclopedia to find out what distinguishes specific genres and movements.

Versification: Look closely at the poem's rhyme and meter. Is there an identifiable rhyme scheme? Is there a set number of syllables in each line? The most common meter for poetry in English is iambic pentameter, which has five feet of two syllables each (thus the name "pentameter") in each of which the strongly stressed syllable follows the unstressed syllable. You can learn more about rhyme and meter by consulting our handout on sound and meter in poetry or the introduction to a standard textbook for poetry such as the Norton Anthology of Poetry . Also relevant to this category of concerns are techniques such as caesura (a pause in the middle of a line) and enjambment (continuing a grammatical sentence or clause from one line to the next). Is there anything that you can tell about the poem from the choices that the author has made in this area? For more information about important literary terms, see our handout on the subject.

Figures of speech: Are there literary devices being used that affect how you read the poem? Here are some examples of commonly discussed figures of speech:

- metaphor: comparison between two unlike things

- simile: comparison between two unlike things using "like" or "as"

- metonymy: one thing stands for something else that is closely related to it (For example, using the phrase "the crown" to refer to the king would be an example of metonymy.)

- synecdoche: a part stands in for a whole (For example, in the phrase "all hands on deck," "hands" stands in for the people in the ship's crew.)

- personification: a non-human thing is endowed with human characteristics

- litotes: a double negative is used for poetic effect (example: not unlike, not displeased)

- irony: a difference between the surface meaning of the words and the implications that may be drawn from them

Cultural Context: How does the poem you are looking at relate to the historical context in which it was written? For example, what's the cultural significance of Walt Whitman's famous elegy for Lincoln "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloomed" in light of post-Civil War cultural trends in the U.S.A? How does John Donne's devotional poetry relate to the contentious religious climate in seventeenth-century England? These questions may take you out of the literature section of your library altogether and involve finding out about philosophy, history, religion, economics, music, or the visual arts.

What Style Should I Use?

It is useful to follow some standard conventions when writing about poetry. First, when you analyze a poem, it is best to use present tense rather than past tense for your verbs. Second, you will want to make use of numerous quotations from the poem and explain their meaning and their significance to your argument. After all, if you do not quote the poem itself when you are making an argument about it, you damage your credibility. If your teacher asks for outside criticism of the poem as well, you should also cite points made by other critics that are relevant to your argument. A third point to remember is that there are various citation formats for citing both the material you get from the poems themselves and the information you get from other critical sources. The most common citation format for writing about poetry is the Modern Language Association (MLA) format .

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

5 Writers Who Blur the Boundary Between Poetry and Essay

"poets are the hoarders of the literary world".

There is a Bernadette Mayer writing exercise that suggests attempting to flood the brain with ideas from varying sources, then writing it all down, without looking at the page or what spreads over it. I have attempted this exercise multiple times, with multiple sources, and what I love about it—along with many of Mayer’s other 81 prompts—is that what comes out can literally take any form. The form is not dictated by the content I read, nor the rules of the exercise. The information I collect prior to writing may be entirely disparate, seemingly unrelated, but through the writing, it begins to take shape, and links are found. In the process of communicating information in a lyric way, barriers to form withheld, I am able to develop a richer portrait of what thinking really looks like.

I heard someone say once that poets are the hoarders of the literary world: collectors of facts, dates, quotes, newspaper headlines, ticket stubs, and love letters. Indeed, another of Mayer’s prompts is to keep a diary, or diar ies , of such useful things. As these journal pages begin to overflow, content spilling over the borders, the writing becomes something we might not always call a poem. Reflecting on his poetry collection The Little Edges and a book of essays The Service Porch , both of which appeared in 2016, poet and critic Fred Moten said , “The line between the criticism and the poetry is sort of blurry. I got some stuff in the poems that probably could’ve been collected with the essays.”

There is a long-standing tradition of poets who have refused genre, or reinvented it, and who continue to push the boundaries of form. Here are five, but just a cursory glance into any of their work will lead you to uncover many more.

Jenny Boully

The first essay in Jenny Boully’s latest collection Betwixt and Between: Essays on the Writing Life, published last month, is a journey into two illusive linguistic temporalities: “the future imagined and the past imagined. ” By positioning the reader in a space of hypothesis, Boully tests the limits of memory and lived experience, never quite allowing her reader to land on stable footing. With this linguistic trick, a redefinition of what is the personal begins to emerge.

Throughout her work, Boully is interested in reorienting the role of the reader from passive to participatory and reorienting the structure of the text from chronological to sensory. In an introduction to Boully’s work, Mary Jo Bang writes , “She uses form in a way that undercuts our every expectation based on previous encounters with poetry.” It’s no wonder that excerpts from her first book The Body , written as footnotes to an imaginary text, were included in both John D’Agata’s The Next American Essay and The Best American Poetry 2002 .

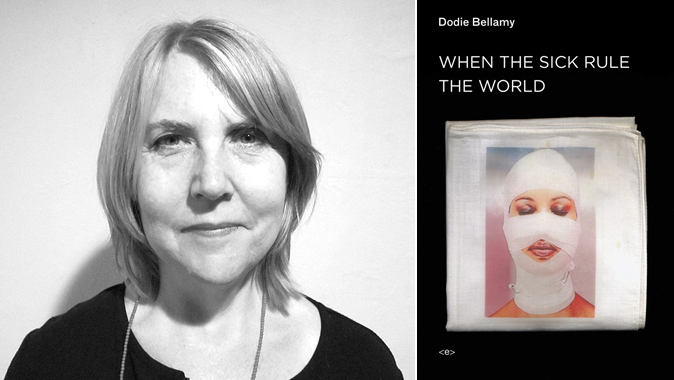

Dodie Bellamy

Dodie Bellamy is a seamstress of language. Her work stretches the definitions of narrative writing by incorporating literary appropriation, cut-ups, collage, and détournement, or the act of turning a recognizable cultural product on itself, a technique developed by the Situationist International in the 1950s. Her poetic “cunt ups” take works of the traditional poetic canon and reinvent them with a contemporary feminist voice, directly splicing the historic masculine texts with pornographic imagery. The 2013 collection Cunt Norton employs the original language of 33 canonical poets, twisting them into erotic poems as an act of love for her predecessors. “These patriarchal voices that threatened to erase me—of course I love them as well,” Bellamy wrote of the work . Her experiments began to take a more prosaic form as she desired further space for her content. “I was writing linked poems that kept getting longer and more narrative,” she said in an interview .

Due to her inventive and often hysterical treatment of language, Bellamy’s voice is engaging on any topic. The themes she tackles in her collected essays When the Sick Rule the World range from the gentrification of San Francisco, her experiences with a women’s writing group and a moving tribute to the late equally inventive writer Kathy Acker, in the form of a catalogue of the contents of her wardrobe.

Claudia Rankine

When Claudia Rankine’s Citizen won the National Book Critics Circle Award, the judges’ citation read, in part, “It’s not (just) poetry.” The prose-poetry hybrid is a current throughout her work; her previous poetry title Don’t Let Me Be Lonely was described, alongside Citizen , as “lyric essays” in the The New York Review of Books . Rankine’s work uses investigative tools of poetry to probe what it means to be human and to encourage readers to examine their personal responsibility to others. Through experiments in form, she highlights the dangers of lazy classification of people and experiences; her words in any medium provoke self-reflection.

In Citizen , a 2015 essay on Serena Williams finds a comfortable home alongside prose and list poems. With her employment of the second person throughout the collection, Rankine prompts her readers to enter into the very experiences she is describing, whether they are wholly familiar or not. As such, her approach is in equal measure confrontational and humanizing.

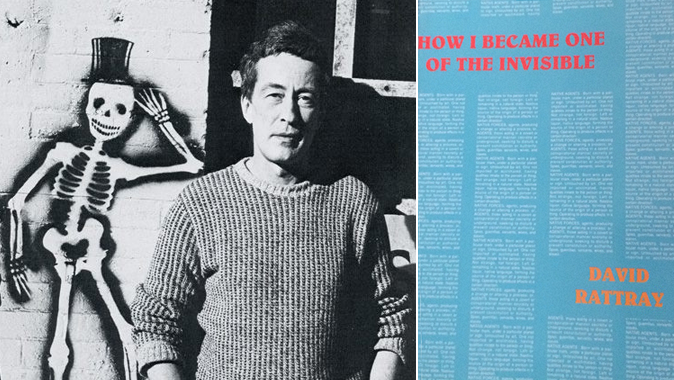

David Rattray

When the poet, critic, and renowned translator David Rattray passed away at the age of 57 in 1993, the experimental writer Lynn Tillman wrote , “He swept us away also with his ‘bad attitude,’ his insubordination to authority and to the authority of what he knew.” This was true not just in the manner he lived his life, but also how he captured life in text. A principle translator of Antonin Artaud, Rattray’s own poems display a diary-like quality: they are grand narrations stuffed full of dates, places, people.

A collection of essays and stories exploring his relationship to close friends, grief, drugs, travel, and literature called How I Became One of the Invisible was put together by Chris Kraus just before his death. Through narratives that are at once breathless and directional, and full of poetic references and quotes, Rattray reveals his deep feelings for those with whom he shared his life. “He believed people were gems, precious, and treated them accordingly,” Betsy Sussler wrote , following his passing. And so too did he treat his words, allowing us to enter into his world imbued with sensitivity.

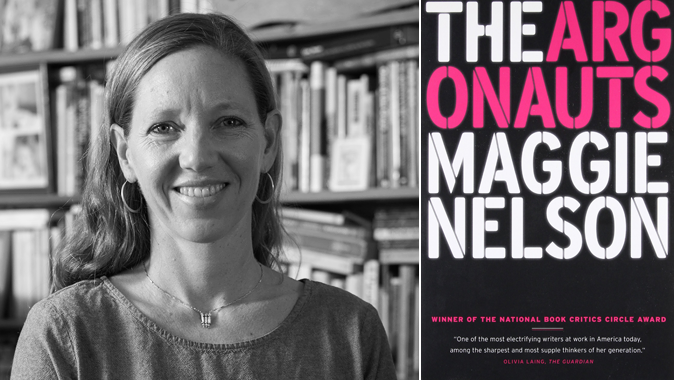

Maggie Nelson

Asked in an interview by Emily Gould as to how she decides on which genre(s) she will employ when writing a new book, Maggie Nelson replied , “Genre, for me, is determined by the unfolding of my interests, which is unknowable at a projects’ start.” Her defiance of category is not only evident in her bibliography, but in the bibliography of each book which makes it up. Bluets , which began as an investigation into the color blue and its varying manifestations throughout history, became a book of prose poems. The Art of Cruelty , a personal reflection on the employment of violence in art, became a book of academic criticism. Begun as a work of criticism, The Argonauts became a personal memoir, with its background research spilling, literally, into the margins. “I find my way to the right tone, idiom, form or set of subjects as I bumble along,” Nelson says.

It is her very adaptability of form and expression that has become one of her signature attributes, despite the literary world’s continued insistence on writerly classification, and in turn mimics the fluidity of her subjects. Hilton Als writes , “It’s Nelson’s articulation of her many selves . . . that makes her readers feel hopeful.”

Listen: Claudia Rankine talks to Paul Holdengräber about objectifying the moment, investigating a subject, and accidental stalking.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Ruby Brunton

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

12 Famous Authors at Work With Their Dogs

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essays Samples >

- Essay Types >

- Research Paper Example

Poetry Research Papers Samples For Students

257 samples of this type

If you're seeking a viable way to simplify writing a Research Paper about Poetry, WowEssays.com paper writing service just might be able to help you out.

For starters, you should skim our large catalog of free samples that cover most various Poetry Research Paper topics and showcase the best academic writing practices. Once you feel that you've studied the key principles of content organization and drawn actionable ideas from these expertly written Research Paper samples, putting together your own academic work should go much smoother.

However, you might still find yourself in a situation when even using top-notch Poetry Research Papers doesn't allow you get the job done on time. In that case, you can get in touch with our writers and ask them to craft a unique Poetry paper according to your individual specifications. Buy college research paper or essay now!

Poetic Structure and the Theme of Death Research Paper

Good research paper about dickinson poems.

The two poems, Because I Could Not Stop for Death, by Emily Dickinson and Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night, by Dylan Thomas deal with the theme of death. Each poem looks at death in different ways. Thomas does not accept death readily, but implores his father to hold on to life. On the other hand, Dickinson accepts death calmly. Both poets make use of figurative devices such as metaphors, personification and alliteration as they explore their opposing views of the concept of death.

Example Of Research Paper On Gawain and the Green Knight

Introduction:.

On page 41 of “Gawain and the Green Knight” the poem speaks more of metrical romance. In this context the poet brings the theme of hunting and seduction. This is in relation to the frequently distinguished corresponding flanked by the three consequent hunting panoramas which are followed by the three seduction scenes. This clearly highlights the correspondence of the scenes that actually does arise when the lord goes out hunting. In this context the scene that does arise is the one which is illustrated by the lord rising early in the morning and goes deer hunting.

Don't waste your time searching for a sample.

Get your research paper done by professional writers!

Just from $10/page

Robert Hass Research Paper Examples

Good example of satire in rochester, swift and dryden research paper, free comparing daystar and miss brill research paper sample, free research paper on perspective of religions in the flea and show me, dear christ sonnets, good example of edgar allan poe research paper, good example of research paper on riders to the sea, analysis of “riders to the sea”, free research paper about historical criticism, introduction, free research paper about poetic voices on slavery, poetry research paper example.

Presentation and evaluation of three critical approaches to the poem ‘To His Coy Mistress’ by Andrew Marvell – Analysis of each one of these approaches according to the socio-historical context of the era in which each approach was developed – Reflections drawn upon these three approaches and personal conclusion upon their validity [The author’s name]

Good Example Of Oscar Wilde Research Paper