‘Learning To Swim At 24 Taught Me An Important Life Lesson’

Assistant editor Naydeline Mejia shares how she came to peace with the water.

It was the summer of 2018. My sister, cousin, and I were aboard a motorboat with seven other wide-eyed tourists hoping to catch a glimpse of the sunken statues off the coast of Isla Mujeres, Mexico. As we pulled away from the beach, I watched the celeste-hued water transform into a midnight blue and realized I could no longer rely on my fragile safety net—the knowledge that I’d be able to see my feet on the ocean floor. This was deep sea.

After about 15 minutes, our captain stopped the vessel and began to distribute the essentials alongside his assistant: life jackets, flippers, and goggles.

“Anyone who wants to get in and see the statues, now’s your chance,” he announced in Spanish, our shared mother tongue.

While I’m aware of the human body’s natural buoyancy in saltwater, I’m also conscious that the ocean will not hesitate to swallow one whole at the first sign of fear. In other words, I wasn’t about to risk it.

I’ve never been a particularly strong swimmer.

While I'd participated in an entire year of swimming lessons in the sixth grade—a rare opportunity for a low-income Black girl attending a West Bronx public school—sometime between the start of puberty and the beginning of adulthood, I had become increasingly aware of my own mortality. For me, this awareness largely manifested in a fear of drowning. When it comes to water-based activities, I prefer to stand comfortably in the shallow end.

And so, one by one, my boat mates made their way into the water. But I stayed onboard. As my family members and the other tourists followed the captain to see the life-sized sculptures which sat 30 feet under the surface, I began to viciously sob—failing miserably to hide my shame from the deckhand watching me as I swallowed my own salty tears.

I’ve always felt a deep connection to bodies of water . Whenever I feel overwhelmed, I search for a waterfront—a rarity in my concrete jungle home of New York City. My affinity also makes sense, since being in or near water has been linked to a reduction in stress, alleviated anxiety, and a boost in overall mood, according to licensed therapist Shontel Cargill, LMFT.

Yet, the visceral pain I felt that day from not being able to jump freely into the water is not something even I truly grasp. It felt like I’d tapped into a deep source within me—an ancestral struggle, almost. It was like I could hear the synchronous wails produced by my collective bloodline, begging for freedom from the forces that kept them shackled to the island of La Española—fearing yet worshiping the water gods.

It’s a common racist trope that Black people can’t swim.

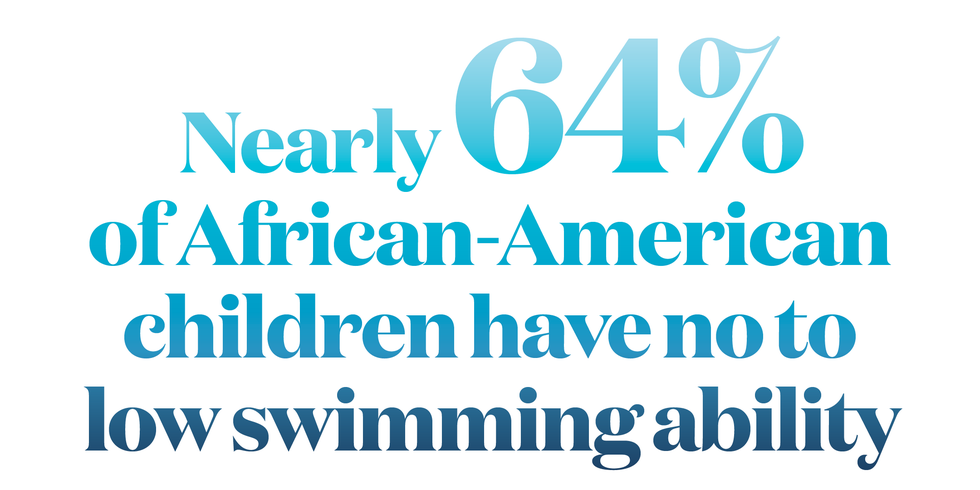

But it’s hard to ignore this one’s startling reality. Nearly 64 percent of African-American children have no to low swimming ability, compared to 45 percent of Hispanic children and 40 percent of Caucasian children, according to USA Swimming . Moreover, Black children drown at rates three times higher than white children, per the CDC .

And it's not just children who are affected. Black people, in general, drown at higher rates than any other demographic, says Paulana Lamonier, the founder and CEO of Black People Will Swim , a mission-based program empowering Black and brown people to be more confident in the water. I first learned about Paulana and her mission after reading a feature on her on CNBC , and knew that when I decided to begin my swim journey, it would be with her.

“The reason why it’s important for us to teach people these life-saving skills is simply that: because it is a life-saving skill,” she tells me. “We’re really giving people that chance to dream again; the chance and opportunity for freedom. When you’re on vacation, you no longer have to sit poolside—you don’t have to be scared to jump.”

Twenty minutes past noon on Saturday, May 20, 2023, I went to my first swim class.

I arrived at CUNY York College’s Health and Physical Education Building where classes for Black People Will Swim’s spring 2023 program were being held. By the time I reached the 25-meter swimming pool, class was already in session.

Paulana, a warm yet commandeering figure, was teaching the class, and invited me to join. As I slowly and awkwardly slid my way into the pool's shallow end, I took in the expressions around me. There was a variety of ages in our adult-beginner course, which was made up of all Black women. Young 20-somethings, like myself, women in their 30s and 40s, and even a few Aunties—elders, often mature women over the age of 50.

Our first lesson started with a breath. We were to learn how to breathe underwater.

One by one, Paulana went around asking each of us to hop down into a squat until our fingertips touched the pool floor. Once there, rather than sucking in air through our nostrils, we were to expel that air by blowing bubbles—holding in the remaining oxygen in our mouths. When my hands touched the bottom of that pool and I was surrounded by blue I felt—if only for a second—at home. If only I could breathe underwater , I thought, I would never leave .

“The water was like my getaway,” says Maritza McClendon , a 2004 Olympic silver medalist and the first Black female to make the U.S. Olympic swim team. “Every time I get in the water, I’m in my happy place—I’m in my element.”

McClendon—who, after being diagnosed with scoliosis, began swimming at the age of six per her doctor’s recommendation—has always found solace in the water, even when the pressures of competitive swimming weighed her down.

"When I got in the pool, it was like I went into an oasis and forgot about everything—it was just me and the water.”

As I re-emerged from the pool after that first drill, I suddenly became aware of my senses. The silence from being submerged disappeared, and I was met with the noises around me.

To my right, one of my classmates—an older woman perhaps in her mid-60s to early 70s—was holding onto the edge, quietly blowing bubbles to herself as the rest of the class moved onto the next lesson.

I pondered what experience may have caused her to develop this palpable fear, and ultimately lead her here today. I also wanted to grab her hand and walk her to the middle of the pool, so we could float together like two otters, holding on tight to ensure the other wouldn't float too far away, and she could share some of the joy I felt.

The truth is, part of the reason why many Black and brown Americans don’t know how to swim today is a result of racial and class discrimination.

“There were two times when swimming surged in popularity—at public swimming pools during the 1920s and 1930s and at suburban swim clubs during the 1950s and 1960s. In both cases, large numbers of white Americans had easy access to these pools, whereas racial discrimination severely restricted Black Americans’ access,” wrote Jeff Wiltse, a historian and author of Contested Waters: A Social History of Swimming Pools in America , in a 2014 paper published in the Journal of Sport and Social Issues .

The systemic impairing of Black Americans’ ability to swim—thanks to poorly maintained and unequal swimming pools, private clubs that barred Black members, and public pool closures in the wake of desegregation—meant that swimming became a “self-perpetuating recreational and sports culture” for white Americans, says Wiltse. Black communities struggled to literally and metaphorically get a foot in.

“[Swimming] is a predominantly white sport,” says McClendon. (FYI: Of the 331,228 USA Swimming members, less than 5 percent are Black or African American, according to the 2021 Membership Demographics Report .)

“Growing up, I was definitely one of the few at every single swim meet, and even on my swim team,” McClendon recounts. “As early as nine years old, I remember finishing a race in which I got first, and walking past a parent who said, ‘You should go back and do track or basketball. What are you doing here?’ Sort of questioning why I was in the sport. If anyone else would’ve won the race, they would’ve been congratulating them.”

While most of McClendon’s career spans the 1990s and early 2000s, she says instances like this still happen today.

I missed the next three weeks of classes, so by the time I walked into my second swim session, I felt energized yet daunted.

As soon as I got in the pool, I asked my classmates about their reasons for joining the Black People Will Swim program.

One woman shared that she wanted to learn how to swim because she’s the only one in her family that couldn't and she had a seven-month-old son: “If he’s drowning, I want to be able to save him,” she tells me.

The second woman I spoke to said almost drowning twice pushed her to want to learn.

Unsurprisingly, most of these reasons pertain to survival. Swimming , at the end of the day, is a skill needed to live; it’s an ability and privilege that so many take for granted.

At the start of that second class, I was anxious. I had missed so much during my time away, and we were at the point of the program where everyone was expected to navigate the 14-foot end of the pool. Our first lesson of the day: butterfly backstrokes. I tried my best to prolong my turn by generously offering that my other classmates go ahead of me, but eventually I had to go.

As I positioned my feet on the wall, held onto the edge of the pool, and laid my head back, I silently repeated to myself, You got this! You are a child of the water. You will not drown. “Ready?” asked the instructor who was teaching my class. With one deep breath, off I went.

As soon as I started kicking my feet and pushing the water forward with my arms, I was making headway. It felt so natural, like muscle memory. Perhaps those middle school swim lessons did teach me something. After about five strokes, I was ordered to stop so the next person could demonstrate if they were ready to move on to the next step.

Swimming is easy enough when you know you can safely land on your feet the moment you start to panic, but once the depth of the pool is above my own height (at 5'4"), I no longer feel at ease. So you can imagine my nervousness when the instructor said we were about to backstroke the entire 25-meter pool.

As I prepared for that feat on the wall, I recounted the memory of that fateful summer of 2018, when I was too afraid to jump off the boat without a lifejacket. Then there was another memory: 11-year-old Naydeline, unafraid to jump into the deep end. Instead, exhilarated by it.

“Ready?” asked the instructor.

Off I went, rapidly backstroking across that 25-meter pool. I was making headway, but as I reached the 12-meter mark, I stopped. I was beginning to swallow water, and the chlorine-tinged liquid filling my throat made me panic. I was no longer swimming, but sinking. I quickly grabbed the nearest lane rope to stabilize myself.

“What happened?” asked my instructor. “You were doing so well.”

“I panicked,” was all I could say. The intrusive thoughts had started to pour in as soon as I sensed the depth of the pool change from six feet to eight feet to 10 feet: You’re drowning, you’re drowning, you’re drowning , and my anxiety took over.

It took a few seconds to catch my breath, but then I turned to face the deep end of the pool. I realized there was no getting out of this—I had to keep going. With my instructor situated behind me to catch me if I began to drown, I shut my eyes and inhaled for three counts, exhaled for three counts, again and again. Ready?

I was off once more. I didn’t stop until I hit the end of the pool.

A month after the end of the swim program, I headed out on a trip to the island of Aruba.

The schedule was filled with walking tours, parasailing, and an exploration of one of the island’s many natural pools.

The author parasailing off a boat at Palm Beach, Aruba.

On the second to last day, we kayaked across a small portion of the Caribbean Sea to go snorkeling. There would be coral reefs, parrotfish, and lobsters. I opted out.

I wasn’t confident that I wouldn’t start to panic and drown. So, while the rest of my tour group and the instructor went ahead, I stayed seated on the dock. As I looked out at the expansive sea around me, noticing how the colors transitioned from celeste to navy, I breathed in deeply: 1, 2, 3, 4, 1, 2, 3, 4 . I was trying my best not to cry.

Our reserved, yet warm tour guide had also stayed behind. He claimed he was tired of beautiful beaches and ocean views—they didn’t impress him, he said. After noticing that I had been sitting alone on the dock for what felt like half an hour, he came to sit next to me. I told him about my deep affinity for the sea, but also how much it terrified me.

“The trick to swimming,” he said, “is letting go of fear. […] The water will do most of the work for you. It’ll hold you up, but only if you let it. You must remain calm, and trust yourself.”

Perhaps that is the missing puzzle piece: trust. Trust in the water, but most importantly, trust in myself. Trust that I could keep myself alive, and the water would help me—if I let it.

Naydeline Mejia is an assistant editor at Women’s Health , where she covers sex, relationships, and lifestyle for WomensHealthMag.com and the print magazine. She is a proud graduate of Baruch College and has more than two years of experience writing and editing lifestyle content. When she’s not writing, you can find her thrift-shopping, binge-watching whatever reality dating show is trending at the moment, and spending countless hours scrolling through Pinterest.

'Bachelorette' Jenn Tran S21: Cast, Release Date

'I Tried Factor Meals For A Full Week'

'The Bachelor': Where Are Joey And Kelsey Now?

All About Caitlin Clark's Family

PSA: Costco's Transformer Table Is Back in Stock

The iPad Air Is at Its Lowest Price Ever on Amazon

See Blake Shelton and Gwen Stefani's New Video

Score Up To 50% Off An Apple Watch Now

See a 'Fixer to Fabulous: Italiano' Deleted Scene

I Tested These Apple Watch Bands And Love Them

The Secret Amazon Coupon Page Is Loaded With Deals

Learning to Swim Taught Me More Than I Bargained for

By Jazmine Hughes March 24, 2020

- Share full article

At 28, I thought my life was pretty settled. Nope.

By Jazmine Hughes

In person, Turks and Caicos looks the same as it does in pictures — cloudless sky, sparkling sand, perfectly turquoise water — except that, of course, the water actually moves. Before I left New York, several people assured me that its ocean was “practically like bathwater,” promising me that, in saltwater, almost anyone could float; I would barely even have to try.

From my lounge chair, I watched the waves — what looked, to me, like a thrashing, unknowable sea — move with the same force as water being lapped from a dog’s bowl. If I stood at the edge, the ocean licking my ankles, I could see straight to the bottom, a generous layer of glassy light blue spread over sand. Still, I was trying not to succumb to dread. I told myself I would get in.

I drank two complimentary mimosas — I couldn’t possibly swim now, I had been drinking — and eavesdropped instead. My beach neighbors were older: a couple perhaps in their 70s, pale and mostly unmoving over the course of the morning. The husband snored the hours away. At one point, he awoke as his wife returned from the water, announcing, “I think it’s good for you.” He seemed satisfied. I assumed she was talking about the weather. He stood up, grabbing first onto her arm and then onto his cane.

The two dawdled to the water’s lip while I peered at them over my book. The husband took a few steps, turned and handed his cane to his wife, then dove in. His head reappeared after a few moments, and he threw his legs up and began floating on his back. The wife deposited the cane back at their lounge chairs, then rejoined him in the water.

I knew the water wasn’t that deep. Earlier that morning, two not particularly tall French tourists swam out to show me exactly how far you could go and still have your feet on the ground. “ C’est si bon! ” The couple was in only up to their shoulders, treading and talking. I admired their ease in the ocean in the same wide-eyed way I admire anyone who can do something I cannot: whistling, snapping fingers, driving a car.

The husband lay happily on his back and shut his eyes in the bliss of relaxation, spreading his arms out wide, barely moving; the wife splashed around him. My skin burned with envy under S.P.F. 30: They were having the time of their lives, and I was hiding under an umbrella. I decided I would get in. Later.

I’m a Calamity Obsessive. After My Trip to Italy, I Was the Calamity. March 24, 2020

Tourism at the End of the World March 24, 2020

Most people I know who swim learned before they could ever consider being afraid. At 28, I didn’t have that luxury. When I asked my mother why I never took swim lessons growing up, she reminded me that I already had a serious childhood extracurricular: competitive tap dancing. (I have a vague memory of getting into a pool during the national championships in Las Vegas and slipping under the surface when I tried to cast onto a floaty and inhaling through my mouth. When I emerged, coughing and sputtering, I angrily, dramatically announced that I had just drowned.) I spent my summers indoors, either at dance camp or vacation Bible school, where I lied about my age in order to be in the same Bible study as my friends, who then ratted me out for sinning. Later, in high school, I stared down the swimming requirement to graduate but then switched schools; in college, and beyond, no one ever asked why I never got into the water.

Three of my four younger sisters at some point took a summer swim class, but none of them ever really learned anything. I was worried that we were reinforcing an ugly stereotype: that black people, because of racism or urban flight or an inherited avoidance, don’t know how to swim. Desperate, I asked my mother if anyone in our family knew how. “Girl,” she said indignantly. “ I know how to swim.”

According to her, everyone who grew up in the 1970s knew how to swim. “We didn’t have all these distractions,” she said. “If there was water, you just went into it.” She learned when she was 7, at the Y.W.C.A. in New Haven, Conn., where I grew up. She described herself as “fearless” in the water — “city kids weren’t scared of nothin.” — but not enough to open her eyes when she was submerged. She pulled her mouth away from the phone and asked her husband, who grew up in the South, where he learned how to swim, to further her point. He learned around the same age, also at his local Y. Later, she texted me my great-great-grandfather’s 1917 military census, where he self-identifies as a good swimmer. “I just don’t know where you went wrong,” she said.

Yet she hadn’t been in a pool in 15 years. She and her husband had recently traveled to Hawaii on vacation, where she got her feet wet, but she otherwise stayed on the beach, relaxing and making sure her husband didn’t drown. She wasn’t scared, she insisted; she just didn’t want to go in, listing her reasons for avoiding the water in order: hair (she didn’t want to get it wet), weather (she prefers to swim only when it’s extremely hot), tan (she wanted one!) and sharks (they’re closer to shore these days, you know).

A year and a half ago, I was in Hawaii, not swimming, too. I was run-down and exhausted, my brain the consistency of a chewed-up eraser. A friend had told me that the water in Hawaii would be healing. Every morning in Honolulu, I woke up at 4 a.m., bought a coffee and sat on the beach, watching the sunrise and the surfers, listening to the Beach Boys’ “Pet Sounds.” One afternoon, I let the water wash over my ankles and burst into tears of sudden relief. But I never considered actually swimming — I didn’t even pack a bathing suit.

I was the water’s groupie, shyly hanging on its outskirts, waiting for the gumption — or invitation — to go in. Five years ago, wanting space to think and not finding enough in my three-bedroom, three-roommate apartment to do so, I rented a house for a weekend on Rockaway Beach, in Queens. I had never spent much time on the beach before, but I figured the water might be nice. I bought a deli hero every day and ate it while staring into Jamaica Bay. Two years later, I convinced my old college roommates to book a trip to Puerto Rico, where they swam in the water and I took pictures posing next to it. A friend and I took a trip to Miami last spring, where I — emboldened by a rum punch — entered the hotel pool up to my knees, dancing wildly, while she stood chest deep. That summer, I rented a houseboat in a marina on Rockaway Beach, spending a week stalking the beach every morning, content to watch roller skaters and burger eaters on the boardwalk, never once considering getting in.

In December, when a reporting trip took me to Los Angeles, I spent all my nonwork hours either walking along Venice Beach, listening to “Pet Sounds” again, or at an open-air restaurant halfway between my hotel and the beach, where I was mesmerized by the barefoot surfers ordering chia puddings and avocado toasts, wetsuits dripping onto the menus. I bought a collection of essays by Sandra Cisneros from a bookstore facing the beach, where she recounts stealing away to a Greek island to finish her first novel and finds herself healed by the sea; I started looking up Greek-island apartment rentals that night.

Only recently did I see the pattern: For some indeterminable reason, I felt drawn to the water, calmer when I was near it. Even just a glimpse from a hotel window seemed like enough.

“The Reluctant Swimmer” met twice a week, Monday and Friday, from 8 to 8:45 p.m., at a large, modernized Y.M.C.A. near Manhattan’s Union Square. I enrolled in January, temporally resolute, wanting to try something new before my new-year nerve wore off. Because the course is designed for people with a fear of the water, it’s limited to only four students, giving each person ample time with — and a chance to be saved by — the instructor. I arrived on my first day outfitted in an extra-large swim cap and the only swimsuit I had — an ill-fitting bright orange one-piece — to find that I was the only person in the course. I was, officially, the most reluctant swimmer in New York.

Paul Hunt, my instructor, fist-bumped me hello. We spent our first class humming, which forces you to close your mouth and push air out of your nostrils. I could hum just fine with my head above water, but as soon as I went under, I felt as if I were choking. I gurgled violently and unintentionally breathed in, causing trails of snot to web around my already-wet face. Paul, an affable man who taught with the playful firmness of a well-loved camp counselor, suggested that I practice in my bathtub that night when I got home. Next, he convinced me that I could float on my back, and eventually I did — albeit with a pool noodle under my legs, his arm under my back and my hand on the wall. I slowly leaned back as though I were being lowered into a grave and kicked my legs up, unconvinced that the water would support me, prepared to sink and shatter my butt into a million pieces. Instead, I stayed afloat, stunned at the lightness of my body.

A few minutes later, as we scooched our way down the wall over to the deep end, Paul told me that my brain was not used to being in the water and that the reluctance I felt was real and physiological — my brain protecting me from a perceived threat. Somewhere around a depth of seven feet, I switched into a visceral terror, gripping onto the wall tightly; by the time we arrived at the end of the pool, nine feet, I was so convinced that my life was over that I felt compelled to confess all my secrets to him, as if we were seatmates on a nose-diving plane.

“The Reluctant Swimmer” lasted eight weeks, and after each class, I took notes. That first night, dripping water onto the subway as I returned home, I wrote that, in class, “I felt true, tangible fear; not anxiety, not nervousness, not stress, but the high kick your brain does into a true panic with a real reason.”

By the next class, I could do a turtle float (drop into the water and wrap your arms around your knees, bobbing to the surface back first) into a jellyfish float (face down in the water, with all your limbs hanging away from you) into a plank position. After a few classes of kicking while holding onto the wall, I upgraded to different forms of flotation support: a kickboard, then a pool noodle, then just my arms, held straight out as if I were receiving a present. Floating, both on my stomach and on my back, became the resting state it was intended to be. In the very last session, I jumped into the deep end, floated to the surface and kicked across the entire pool on my back — alone. When I was done, Paul told me I was good enough to enroll in a swim course for beginners.

My months of learning how to swim followed a two-year period of learning how to date women, which I was better at. I had spent my early 20s in a domestic partnership with a handsome, broad-shouldered man who made me enormous sandwiches and kissed me on the forehead in the morning. When we broke up, I spent the following year casually dating, going through boys like water. But then I kissed a woman in the hazy hours after a happy new year — and then again a few days later — and I discovered I liked it better than anything else in the world.

So I came out with little fanfare, announcing not an identity but a girlfriend. I never considered that I might have long had feelings for women, but instead happily convinced myself that this was a sudden turn that righted the course. Recently, though, evidence of an earlier, latent queerness kept emerging, like apples floating to the surface of a barrel.

As a child, I learned about an omnipresent and homophobic God, so I trained myself not so much to suppress my impure thoughts as to let them just float away, unexplored. But the truth still told on itself. In middle school, for example, I watched the cheerleading film “Bring It On,” more or less a movie about girls in short skirts, every Friday night, without fail, for a year, “for no reason.” One year for Christmas I asked for a vest. Since college, my favorite song has been Charles Mingus’s “Girl of My Dreams,” and when my roommates and I would pile together on the couch, planning our future weddings over rosé and brownie batter, I would anguish over trying to figure out how to integrate the song into my future ceremony. I couldn’t demand my future husband dub me the girl of his dreams, I knew, but it didn’t occur to me that I could go out and find my own.

Once, about halfway through my long relationship, I went to Paris on my own. After dinner one night, I downloaded a dating app for the first time just to see and edited the settings to include women, safely swiping thousands of miles away from my home. I matched with some people, and a woman sent me an invitation for a meet-up of queer women later that night. I deleted the app before I could respond or remember the address. I flew back home to my boyfriend, who met me at the airport; it was the longest we had been apart in years, and we fell into each other’s arms with relief. I was lucky: I had a supportive partner whom I loved, and strong land legs. Who was I to want more?

All those years, I sat on all those shores, in Honolulu, in Queens, in Miami, in Los Angeles, watching people in the water, letting my admiration mask my envy. In truth, I was wickedly jealous: not of their skill but of their willingness to go out and learn, to get what they wanted and then to have it every day. I didn’t realize what I was really feeling until I recently read an old diary, curious to know more about the last time I was flailing. So many entries detail that same longing. One night, for instance, I was at a bar, content to share a drink with a male friend, when two queer women showed up on a date, and suddenly, I wasn’t. A bunch of their friends arrived, and I stopped listening to mine, fully entranced by the scene in front of me, studying the ways they looked at and touched one another, wanting to be part of it all.

Most of these latent memories — the movie, the Paris trip — had evaded me for years, boomerangs that returned after a long period of absence. Eventually, I worked up the courage to tell that old boyfriend about my new girlfriend. He wasn’t surprised by my admission: I had mentioned something like this a handful of times in the relationship, he said. Did I really not remember?

There’s a difference, I learned, between knowing something about yourself and accepting it. A few weeks into class, my swim diary became a regular diary, and I would intersperse the recordings of swim lessons with notes about my day-to-day life. I had two dates the week of my fourth swim class. My entry ended with, “I can’t believe I get to do this!” I don’t remember which one I meant.

From the plane, the sight of the water of Turks and Caicos made me sweaty and excited, as if I were preparing to go on a date. It was the end of February, and on this vacation I would finally swim in the ocean. But once I arrived, I kept finding ways to avoid getting into it. One afternoon, I sat in a restaurant near the beach, killing time, when two people peacefully paddled by me in a kayak. Suddenly competitive with these strangers, I decided that kayaking, for the first time and alone, might be fun.

If I could get into a kayak in the water, I thought, at some point I would swim. In a life jacket, I paddled around, pleased for even trying. If I can make it to that dock over there, I can get out. Accomplished, with ease. If I can make it from the dock to the reefs, I can finally leave the beach. Done!

I was turning back to shore when a father and a daughter came around the reefs’ bend. “There’s a shipwreck over there!” the child screeched. I told them I would try to make it over, but it was my first time kayaking. The dad told me I had nothing to worry about. “You can swim, right?”

“Not really!” I said in response, already paddling away.

The farther I got out from shore — the closer to the shipwreck — the choppier the waves became. There was nothing shielding me from the wind. The pulling became harder. I made it around the bend and saw the shipwreck from afar, a rusty humpback whale, then stopped kayaking long enough to catch my breath. A wave crashed me into a reef, then another. The wind had suddenly increased: I kept trying to pivot, but I couldn’t pull hard enough. My kayak got stuck between the reefs as though I had parallel-parked there, trapped lengthwise inside a little enclosure that kept me hidden from the shore.

I tried to keep calm. When I’m nervous, I sing. I started with the first song that popped into my head. “Anything … you can do … I can do better,” I sang through gritted teeth, fists clenched, trying to back myself out amid the rolling waves. “I can do … anything … better than you,” I sang to my ultimate nemesis: one of the calmest beaches in the world on a mildly windy day.

Eventually, the kayaking father returned with another child and guided me while I backed myself out. He led the way to the shipwreck, occasionally whooping with joy. Up close, it was unremarkable, and it occurred to me that I didn’t know if I was looking at a scene of death or survival. Still, now that I had done this, I was pulsing with adrenaline, dizzy with the new knowledge that I could do practically anything.

I returned to shore, dropped the kayak off, then waded back into the water. A woman waist deep was taking a selfie; another woman was still wearing her shorts. Before I could persuade myself to turn back, I was tasting saltwater, pulling my arms and kicking my legs froggy style. It was an overcast day, and the water put everything just out of focus. After two pulls, I remembered that I had to breathe; after two breaths, I got anxious. I was panicking, taking in shallow, quick breaths that were more for show than for air. I am relaxing on my beach vacation, I thought, hyperventilating.

I pushed my goggles off my face and tried floating on my back instead, holding my breath, afraid to let any air out of my lungs. The water encircled my face and splashed into my eyes, which I kept shut, confident that the saltwater would dry up my contacts and I’d have to swim back to shore a blind woman. I opened my eyes — not blind — and realized, to my horror, that I had been swimming away from the shore instead of toward it. I took a breath. I could panic, I thought to myself, or I could save myself.

I stood up.

The two experiences — coming out, learning to swim — kept braiding together, a second adolescence, and then a third. I would arrive to swim class awkward and jittery, nervously cracking jokes as soon as I got in sight of the water, babbling as if I were in front of a crush; I’d leave feeling on top of the world or six feet deep in it, my moods shifty and sudden. I cried random tears of happiness, disorientation, relief. Water would get into my nose, and I’d feel like a failure; I’d survive a jump into the deep end and feel ecstasy. At times, I dreaded going to class with the same angst as having to ask a girl on a date. I felt gawky and unsure and annoyed and insecure and thrilled and elated and confused and strong and brilliant and wondrous all at once. I was performing miracles every day.

There were a bevy of metaphors I employed to explain why, after a lifetime of happily dating men, I had suddenly switched gears: I had upgraded from coach to first class; I was in tryouts for the other team. But the metaphor that felt most right involved my eyesight. In fifth grade, from the second row of my classroom, I could see the whiteboard decently, but I was sure things could be better. I asked to get an eye exam. As I rode home from the optometrist a month later with my parents, a pair of round frames on my face, I looked at the edges of all the leaves with wonder and relief. Everything had come into focus.

The day after the kayak incident, I woke determined to swim. I went to a family resort with a water trampoline a few yards from shore. For a while, it was crawling with children, so I stayed in my seat, an impatient and surly teenager not wanting to play with the babies. When they got out, I got in. Immediately, I started to panic. I wondered if anyone on the shore — dads in hats and reflective glasses, an older woman reading a Danielle Steel novel, children munching on mahi-mahi tacos — would notice if I didn’t come back up. I brought my head above water and took a shallow, audible breath. Fatigue crept in. The trampoline was still so far. I gave up on inhaling and just held my breath, puffing my cheeks out to keep all the air in. Five or six pulls of the arms later, I grabbed the bottom rung like a life raft, thrilled to be safe.

But I still had to swim back to shore. I considered jumping off, as I had seen the kids do, but quickly humbled myself, sliding in off the side. Even with goggles, the water was murky, and I couldn’t tell how deep it was. My pulling got more frantic, my breaths shallower. I swam into infinity, unsure of where I was going and in which direction. My energy had been zapped. I gave up and scrambled back to shore.

I didn’t think I’d ever enjoy this. But the next day, I made myself get into Grace Bay, where I saw the older couple two days earlier. I wore a snorkel mask to get myself comfortable breathing and swam a few feet out from shore until I relaxed. With the mask on, I swam vigorously, growing overconfident, then nervous about my overconfidence, convinced that I was swimming out toward the horizon, never to be seen again. Then I ran into a pair of knees: a couple asking me to take a picture of them standing in the water. In the midst of our conversation, we saw something move past us. I pulled my goggles down and dove in, spotting my first fish: one blue tang, scuttling away from me.

In the ocean, I wasn’t afraid of what I might find beneath — seeing something new was the most appealing reason to get in. I would finally see what I had been missing all this time. The first time I ever opened my eyes underwater was in the pool with Paul. He had me grip the ledge and hang down by my arms, just to look around and know that I could come back up: I saw an Atlantis of pasty white legs and tiled lines, the light blue and refracted. In various diary entries, I insisted I wasn’t a lesbian, but I still couldn’t stop thinking about them. I started to see them everywhere.

My friend Jessica drove me to the airport for my flight to Turks and Caicos. She and I have an inside joke that we repeat to each other whenever we’re together: an astonished, resigned “You’ve changed.” On the drive, we traded accusations — she had a new haircut, I had glasses she hadn’t yet seen — and laughed. “You have changed, though,” she said. I had gone to her apartment the night before my first class, where she lent me goggles and a combination lock. “The last time I saw you, you weren’t a swimmer,” she said.

I still didn’t think I was. To be “a swimmer” implied mastery and decisiveness — I knew how to swim, I could swim, I had swum, I feel good swimming, swimming is part of me — whereas my ability was still inchoate, relegated largely to the shallow end. Afraid to commit, I wanted the word to reflect my process: I am taking a swim class, I am learning how to swim, I am figuring out what to do, I am mildly better than before. To call myself a swimmer felt deceitful. But I could get myself to the far side of the pool now — when would I be good enough to be what I effectively was?

After I started dating women, there was an inner urgency to give the change a name. My relationship seemed to stave off any inquiries about whether I was “going through a phase,” but I wondered myself if I was attracted to all women or just this one, a hypothesis I was happy to test after we broke up. My life had changed — the laws of attraction had morphed and expanded — but I hadn’t: I was always happy, but now I was just happier. Even an identity expansive enough to encompass all potential future destinations — bisexual, pansexual, queer — seemed too committal, and I was reluctant to give myself, as I had long known me, up. I joked, instead, that I was a “part-time lesbian,” worried that any further commitment would be an unmovable flag in the ground.

On the last day of swim class, Paul admonished me for grabbing onto the wall whenever I got scared or tired. “There is no wall on the beach!” he said. This was why we spent so much time at the beginning working on starting from the front plank and flipping onto my back. He wanted to make certain that if I’m ever in danger or too tired or confused, I can flip to float and regain my senses, elementary backstroking to safety. It took me half the course to perfect it, and I savored practicing the move, sloshing my body from left to right as if a pickle in a jar. The point of “The Reluctant Swimmer,” really, was baked into this motion: I didn’t need to know how to excel at swimming. I needed to know I could save myself.

I wanted to try the move on Grace Bay: If I can do this, I wagered to myself, I can get out of the water. On my last day, I lifted my head, took a gulp of air, then descended. I pulled twice and flipped onto my back with relative ease. I elementary backstroked, following the instructions from class — hanging each arm like a chicken wing, stretching my body out like a starfish, pulling my limbs all together like a rocket ship — gliding over the water. When I learned the stroke, I explained to friends who thought this meant I knew how to swim that it was only a safety stroke, something I would do if I were ever pushed off a boat. “It’s not for fun,” I would say. But it was, once I got used to it. I was relaxing on my beach vacation.

Self-definition is a grueling, delicious task. To be a teenager is to be a testing ground for the assembly of your person; to be a young adult is to have free rein to make mistakes. At some point, we make a plan that reflects the self-knowledge we’ve accumulated thus far — I am this, I like that, here are my intentions. But a plan is a limited comfort. What would happen if we allowed ourselves to deviate?

I might still spend this summer on the shore, and even now, “lesbian” feels close but not precise. (My new joke is that I’m a Kinsey 5.) Two months after coming out, I wrote this in my diary: “Some days, I feel like … I can peacefully submit to the new tide; other days, I feel like I’m drowning. I can’t control the movement, but I can control the actions.” That was before I ever submerged myself in water.

Travel in a Plague Year Tourism at the End of the World

Jazmine Hughes is a story editor for the magazine. She is one of the recipients of the 2020 ASME Next Awards, celebrating journalists under 30. She previously wrote a feature about generational consultants.

- Travel in a Plague Year

- Tourism at the End of the World

- Learning to Swim

A Guide to Swimming and Other Aquatic Activities

With just 30 minutes of swimming and a few useful tricks, a trip to the pool can become serious exercise .

Don’t feel like swimming? This 20-minute aquatic exercise routine is easy on the joints and provides a fun alternative to the gym .

Need a challenge? Consider training for the SCAR Swim, a 40-mile open water race across four lakes in Arizona .

If you want to avoid nasty germs and water-caused illnesses when visiting pools, lakes and water parks, these are some things to consider .

Is the water too polluted to dive into? Here is how to tell .

Travel companies are building entire tours around organized swims. Here are some options .

Cold water plunges are trendy. But do they really help reduce anxiety and depression ?

Advertisement

Home — Essay Samples — Life — Swimming — Learning to Swim for the First Time

Learning to Swim for The First Time

- Categories: Swimming

About this sample

Words: 585 |

Published: Jan 25, 2024

Words: 585 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr Jacklynne

Verified writer

- Expert in: Life

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 507 words

6 pages / 2514 words

2 pages / 1061 words

1 pages / 632 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Swimming

Swimming, once a simple act of human locomotion through water, has evolved significantly in response to technological advancements and modern demands. In this essay, we will explore how swimming has adapted to these changes, [...]

Swimming is a typical activity people of all ages enjoy in the summer. Americans spend hours passing time at the pool sunbathing, floating in the water, or watching their children. These activities are usually the first things [...]

Written records of swimming date back to near 2000 BC, however, nowhere are strokes or techniques mentioned, children were simply taught to swim. A record from between 2160 BC and 1780 BC from an Egyptian nobleman says “his [...]

"My hobby is swimming," I proudly declare as I submerge myself into the azure waters of the pool, feeling the soothing embrace of liquid tranquility. Swimming is not just an activity; it's a passion that has enriched my life in [...]

As a child, I remember watching Disney’s “The Little Mermaid”, and being awestruck by the raw strength of water, daydreaming and visualising myself as a mermaid. My first swimming lesson started soon after that. The fear that [...]

This morning is the start of one of the biggest swim meets of the year, the West Virginia High School State Championship in Morgantown, WV. As I gather my suits and walk out of the hotel, a blast of cold February air hits me. [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

- Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

Learning to Swim, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 582

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

Learning new skills or ideas has always been a scary experience for me. All my life, I have always admired swimmers and wished that I could learn the art myself. The thought of being in water without drowning has always amazed me. How can someone go into a bottomless end of a pool of water without drowning? That has always been my primary question. Swimming is one of the hardest things I have ever had to learn. Since I was a child, my parents always encouraged me to learn how to swim, but I always brushed that view aside because of my fear of water.

One day I decided that swimming was a great skill, which I had to learn by all means. This is because it was fun to watch people swim and the activity would form a good exercise for me since I needed a way to work out so that I could be able to keep fit. However, it did not dawn on me that swimming could increase my self-esteem and make me such a confident person.

Learning new activities has always made me uneasy; this was the same case as with my first swimming lesson. I took my time to change into my swimming costume, said a prayer in the locker room and then walked to the poolside. I stood timidly by the poolside as I waited for the swimming instructor to take me through my first swimming lesson ever. This was the biggest moment for me, and I could not let my fear of water or anything else ruin it for me. After some minutes, the swimming instructor emerged from the locker room. She smiled at me warmly and introduced herself. She then called three other ladies who had enrolled for the swimming classes to join me. I was scared initially but on knowing that the other ladies would join me in learning how to swim, I felt confident. We started the swimming lessons by doing a few warm up exercises and finally got into the shallow end of the water.

The instructor carefully took us through the swimming basics. She helped us try a few easy swimming techniques like how to breath and hold your breath in water. I was amazed to see that the other two ladies who were older than me were not embarrassed at all about not knowing how to swim. They made me feel at ease, and together we learned how to swim with the help of the instructor. After a couple of swimming classes, I had learned how to float on water. This was very encouraging. It took me several other classes to master the skills of swimming and learn various swimming styles. After a couple of weeks, I was able to do the backstroke, breaststroke, and freestyle from one end of the pool to the other without difficulty. Surprisingly enough, I was even able to swim at the pool’s deep end, something I never thought I could do.

With my good swimming skills, I decided to join my school swimming team where I perfected my swimming skills and even participated in the school swimming competitions. Today, I can stand and brag about being one of the best swimmers my university has ever had. I have participated in various competitions where I have emerged triumphant. My room is full of trophies that I got from winning swimming competitions. I was missing so much before, and I am so glad I learned how to swim.

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

The Impact of the Revolutionary War on Slavery, Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes Example

Global Warming, Annotated Bibliography Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Voting as a civic responsibility, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 999

The Term “Social Construction of Reality”, Essay Example

Words: 371

- Work + Money

- Relationships

- Slow Living

Reader Essay: The Times I Taught Myself To Swim

This essay was reader-submitted for our essay series on themes of joy, bliss, lightheartedness, and wonder.

By definition, the Bay Islands in Honduras would’ve been the perfect place to learn. The gentlest of waves, privacy in at least one of the watery nooks on the islands, sea so transparent it cannot frighten or confuse at all, seemed like very adequate reasons. I had even gotten into the habit of choosing my rentals based on my coming routine, a preliminary to my life as a 6 a.m. swim kind of girl. The intention was that one day I’d walk home, sun and salt water bleaching the hair on my arms and my head a reddish, coppery color, and that it would become normal for the month I was visiting.

“I’d eventually pause, anchoring my toes in the sea bed, confiding that I couldn’t go much further because I couldn’t swim—yet.”

Two weeks in and I was still untransformed by sun rays and sea water exposure. I had made two new friends since arriving and they could both swim. After getting waist-deep in the waters, I’d eventually pause, anchoring my toes in the sea bed, confiding that I couldn’t go much further because I couldn’t swim—yet. In always adding the ‘yet’ they’d understood my intention and separately offered to teach me. Both admitted that they were not the best, but more than able to help me float, doggy paddle, or just drench myself a little further out than where I stood.

I thanked them both but immediately realized this was not what I wanted. I returned to my original plan; I would try alone first. The next Monday, I wandered out to the transparent bay waters, feeling sure this would be the day. I waded in slowly, to my core first and then a little further somewhere level to my heart. I stood there, swaying in the quietness. A few speed boats bolted past, bringing with them a generous array of waves. And then, stillness again. I stood, feeling the salt in the water wanting to carry me with it, letting me know, gently, that I was sort of in the way, that everything here exists in flow. It reminded me of dancing in a group or moving in the direction of a strong wind, though rooted. Lifting one leg, being taken enough to have to hop, and feeling how my body was apparently more comfortable with submersion than my expectations, I’d place it down again. The salty body of water was too eager and I was not ready, yet.

Taking a trip to Jamaica for the first time and glimpsing a life that could’ve been mine was not an affair I could judge from land alone. My grandparents traded lushness, collected rainwater, and Sunday dinners by the river for life in London. My first time going to the beach in St. Ann Parish was a test to see if I belonged to the waters, the way I knew I belonged to the waterfalls, like my grandmothers. At this time, I had no intention to swim. I just wanted to cool down. I thought a lot about blending in, being among distant kin, and then if I could belong to the waters that once brought us there.

“My first time going to the beach in St. Ann Parish was a test to see if I belonged to the waters, the way I knew I belonged to the waterfalls, like my grandmothers.”

My relationship with the ocean, as a Caribbean person, is a matter of trust, then. It’s not just the beauty of the Caribbean sea that I was encountering for the first time, but how many chose to remain beneath it, how it is a place of freedom and a consequence of bondage, how it is alive, memoried and very new for someone born on the other side of it. I did not swim but let myself go as far as the gut would allow. I watched the sun set, ate well and humored the man who asked me why I wouldn’t swim, why I would come to the beach to ‘wet my foot’. He reminded me that our humor and ability to make jokes out of everything is likely born from survival mechanisms and big island character. I sat and admired fellow Jamaicans who had made peace with their waters.

There was one lady who had an enormous laugh even while her head bobbed above the water. Her turquoise bathing suit made her seem as if she had herself become the sea. She made me want to stay and enjoy the ocean just a little longer, so that I didn’t feel like I was still so in-between worlds. She noticed me as I made my way back to the sand, “You look like a beautiful little mermaid, girl” and she would float, led to wherever the water would want her.

Once replacing my favorite beach spot (the former favorite was not actually ‘secret’ but unvisited because the mangroves are suggestive of crocodile territory), and enjoying a WhatsApp video call with my grandad, who demonstrated what I should be doing with my legs while swimming—phone lop-sided in his hand and the other used for the demo—I had unlocked all that I needed to swim. Mainly this was courage, gratitude for grandparents, and the first days of the rainy season in Belize’s cayes, which makes everything immediate.

“My first attempt didn’t work, not because of anything in the water but because I was embarrassed.”

My first attempt didn’t work, not because of anything in the water but because I was embarrassed by the one family and the several workers who were posted at the beach in the moments before a two-day-long downpour. I got in, looking around in case anyone was watching, which they were, then sat on the shore, thinking to wait them out. The sky grew grayer, the children playing seemed cold but still adamant on gathering their rocks and then, deciding it would be annoying to ride the pot-holed path home in the rain, I left. I did some sun salutations, thanked the water and observed the almost full moon making its daytime appearance.

Two days later, I went again, when the road had dried up, leaving too early for the suggestion of rainfall to matter. An empty beach and blue skies were all that awaited. I got in, speaking my intention, asking the ocean permission once again to host me for these few minutes while I reacquainted myself. Remembering my grandad’s digital demonstration, I crouched, sea up to my neck, slightly giddy at my decidedness. With my palms flat on the seafloor, I didn’t resist my body’s natural desire to rise this time. Before long, it was one arm followed by another and then brief coordination, and then stopping and remembering breath, and then my first stride forward and my second and my feet, arms, and entire body working to stay up, swimming.

“I went in search of a relationship with the water, in several places, and received new definitions of bliss.”

The memory that I will carry with me is how I went in search of a relationship with the water, in several places, and received new definitions of bliss. I released the fear of what lurks physically and historically in the ocean, fear of being seen, of being perceived as a beginner, of burdening others, and the weight that I thought would follow me into the ocean. I learnt what no instructor could teach me; peace of mind that I am good at surrendering.

“I learnt what no instructor could teach me; peace of mind that I am good at surrendering.”

I still swim, and want to return to all the places I have had to admire from dry land. I want to plunge into the Cypriot waters, go back to a cenote in the Yucatán state on my birthday and, this time, get in, and call people in while floating and treading water, telling them not to be afraid to jump. I’ll dive off boats, float under moonlight, watch as, over time, maybe a string of weekends in August, I’ll find myself the furthest from the land that I have ever drifted.

The sea is a new terrain that I’m excited to witness myself in. This time as a gentle teacher, persistent student, insisting on 15 minutes longer, the taste of salt on my lips, rinsing my skin and hair before peddling home barefoot. I celebrate myself for the small wins, gliding and splashing loudly somewhere in the warm Caribbean sea.

Amara Amaryah is a Jamaican poet and essayist, born in London. Her writings are interested in voice — often voicelessness — and reclamations of identity through definitions of home. Her work has been received, translated and read internationally. The Opposite of an Exodus is her debut pamphlet (Bad Betty Press, 2021).

RELATED READING

Why Are You So Hard On Yourself?

9 Dinner Party Games For Your Next Gathering

How To Host a Dinner Party For New Friends (Who Don't Know Each Other)

What To Consider When Buying Your First Pair Of Hearing Aids (2024)

Why You Should Learn to Swim: It Could Save Your Life

Thousands in the U.S. drown accidentally each year.

Years before he became a U.S. Olympic swimmer, Cullen Jones almost drowned in front of his parents.

Young Cullen loved the water. He happily spent hours in the bathtub, “until I was a prune,” he recalls. At age 5, his parents took him to a water park in Pennsylvania. His father slid down a water slide in an inner tube, followed by a gleeful Cullen. His joy quickly turned to terror. “I flipped upside down,” Jones, now 33, says. “Underwater, I held onto the inner tube, trying to pull myself up, but I didn’t have the strength.” Cullen lost consciousness; a lifeguard rescued and helped resuscitate him .

The terrifying episode prompted Jones’ parents to take him to swimming lessons. Jones – who won a gold medal as part of a U.S. men’s freestyle relay team in the 2008 London Olympic Games – recounts his near-drowning as part of his efforts to encourage kids, adolescents, teenagers and adults to learn to swim on behalf of the USA Swimming Foundation's “Make a Splash” program. He and other proponents of swimming and water safety point out that every year, about 3,500 people in the U.S. accidentally drown, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Swimming is “not only a recreational activity – it’s a skill that saves lives,” says Lindsay Mondick, senior manager-aquatics for the YMCA. Swimming programs not only teach people how to swim, but they also provide other safety training, such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation lessons, demonstrations of how to use safety equipment, such as flotation devices, and tips on safer places to swim.

[See: 7 Exercises You Can Do Now to Save Your Knees Later .]

Outreach efforts by the USA Swimming Foundation (which works with hundreds of local pools), the YMCA and hundreds of local recreation programs are making a difference, says Debbie Hesse , executive director of USA Swimming Foundation. The foundation recently released a new study by the University of Memphis and the University of Nevada-Las Vegas measuring the swimming ability of kids ages 4 to 18 and parents and other caregivers in the U.S. Within this group, the study found that 64 percent of African-Americans, 45 percent of Hispanics and 40 percent of Caucasians have little or no swimming ability, which puts them at risk for drowning. Those numbers may not sound great, but they’re an improvement of 5 to 10 percent (depending on the group) over a 2010 survey released by the foundation. That survey found that 70 percent of African-Americans had little or no swimming ability.

A 2014 study by the CDC found that the rate of drowning in swimming pools for black kids and teens between ages 5 and 19 is more than five times that of white children. This lack of swimming ability has led to some high-profile tragedies: In August 2010, for example, a black teenager wading along the Red River shoreline near Shreveport, Louisiana, slipped off a ledge into deeper water. The teen didn’t know how to swim and yelled for help. Five siblings and cousins rushed into the water to save him – but none of them could swim, either. All six drowned.

Pre-civil rights era Jim Crow policies account for why relatively few African-Americans have learned how to swim, says Jeff Wiltse , a history professor at the University of Montana who wrote “The Black-White Swimming Disparity in America: A Deadly Legacy of Swimming Pool Discrimination,” published in 2014 in the Journal of Sport and Social Issues. He also wrote the book “Contested Waters: A Social History of Swimming Pools in America.”

“The comparatively low swimming rates among black Americans today is, in large part, a legacy of past discrimination. Swimming became popularized among white Americans in the 1920s and 1930s at municipal swimming pools and in the 1950s and 1960s at suburban club pools,” Wiltse says. “Black Americans were largely denied access to these pools and the swim lessons that occurred at them. As a result, swimming never became integral to black Americans’ recreation and sports culture and was not passed down from generation to generation as commonly occurred with whites. In many cases, black parents passed along a fear of water to their children rather than the practice of swimming. In this way, the swimming disparity created by past discrimination persists to the present.”

[See: The 10 Most Underrated Exercises, According to Top Trainers .]

Jones, one of the most prominent African-American swimmers in U.S. history, hopes he and other black swimmers can serve as role models for black youths. Jones wants blacks and everyone else to not only learn swimming for safety reasons, but to improve their health. Swimming is great exercise that's easy on the joints, so it’s excellent for people with arthritis . It doesn’t take a toll on your feet or legs the way high-impact exercise can. Swimming can also help ward off diabetes , obesity and heart disease. “The ball is rolling, but there’s a lot more work to be done,” Jones says.

If you want to learn how to swim and get water safety training, or want your child to take swimming lessons, experts suggest these strategies:

Consider your options. Between programs offered by the USA Swimming Foundation, the YMCA, local parks and recreation centers and private swim schools, you should be able to find a regimen that suits your child or you in your area virtually everywhere in the country. At the foundation’s website , you can find more than 1,000 lesson providers.

Look for affordable lessons. This year, the YMCA will provide 27,000 scholarships for swimming lessons in underserved communities , Mondick says. The USA Swimming Foundation will provide $450,000 in grants this year to provide free or reduced-cost swimming lessons to children whose families otherwise wouldn't be able to afford them. And the Los Angeles County Department of Parks and Recreation has 31 swimming pools and another 30 splash pads (areas for water play that have no standing water, but could have ground nozzles) and small water parks, says Joe Goss, chief of the department’s aquatics program. In partnership with the American Red Cross, the department offers free swimming lessons in disadvantaged areas.

Keeping Your Kids Healthy at Summer Camp

Lisa Esposito June 19, 2014

Don’t procrastinate. Many people have a “this will never happen to me” attitude about drowning, says Jim O’Connor, aquatics safety coordinator for Miami-Dade County’s Department of Parks, Recreation and Open Spaces. “It only takes 20 to 60 seconds for someone to be totally submerged in water,” he says. “It can happen quickly in a backyard pool with an unsupervised child."

The danger can be deceptive because “drowning doesn’t look like drowning,” says Lauren Bordages , director of Stop Drowning Now, an organization based in Tustin, California, that's dedicated to saving lives through drowning prevention and water safety education. “Drowning isn’t a splashy dramatic scene from television,” she says. “Drowning is silent.”

Don’t let age stop you. Some swimming programs offer training to children as young as 3 months. At that age, it’s about getting kids acclimated to water. Conversely, no one is ever too old to learn how to swim, Jones says. His mom, who’s 66, is planning on taking swim lessons this year. “You can learn to swim at any age,” he says.

[See: 8 Healthy West Coast Habits East Coasters Should Adopt .]

Have fun. “Swimming is one of the best ways to cool off in the summer heat and a fun way to stay active,” says Keith Anderson , director of the District of Columbia Department of Parks and Recreation. “Take it from me; I swam as a youth, and it was one of my favorite sporting activities.”

7 Ways to Boost Poolside Confidence Without Changing Your Body

Tags: sports , water , water safety , death

Most Popular

Senior Care

Patient Advice

health disclaimer »

Disclaimer and a note about your health », you may also like, when to stop exercising immediately.

Elaine K. Howley and Anna Medaris Miller March 25, 2024

Best Workouts for Women Over 50

Cedric X. Bryant March 14, 2024

Yoga for Knee Pain

Jake Panasevich Feb. 29, 2024

You Should Use These 9 Gym Machines

Ruben Castaneda , K. Aleisha Fetters and Payton Sy Feb. 23, 2024

Exercise: How Much Do You Need?

Cedric X. Bryant Feb. 15, 2024

How to Prevent Pickleball Injuries

Cedric X. Bryant Jan. 25, 2024

Are Energy Drinks Bad For You?

Elaine K. Howley and Anna Medaris Miller Jan. 19, 2024

Mind-Blowing Benefits of Exercise

Vanessa Caceres and Stacey Colino Jan. 10, 2024

Staying Fit During the Holidays

Cedric X. Bryant Dec. 8, 2023

Exercises to Strengthen Your Core

Cedric X. Bryant Nov. 30, 2023

How I Learned To Swim Essay

Leonard Morse 12/21/2010 ? Personal Narrative Short Paper How I had to learn to swim. Learning something new for me can usually be somewhat of an experience that’s frightening for me at various times in my life. One of the most difficult things that I had to do was learn how to swim because I was pushed into a pool when I was around 12 or 13 years old and it scared the daylights out of me. I was afraid of deep waters, but after being pushed into the pool as horseplay from my friends, I came to the conclusion that I ad to learn to swim to remove the fear and phobias that I had.

I also started to lift weights and exercise to help me to become physically stronger as I was a very skinny kid growing up. As I began to learn how to swim, I became more confident in myself as a person. As I stated earlier, situations new to me always make me a bit nervous, and my first swimming lesson was no exception.

After I changed into my swimming trunks in the locker-room, I stood by the side of the pool, cold and scared waiting for the physical ducation teacher who was teaching us the swimming lessons and the other students to show up. After a couple of minutes the teacher came over. He introduced himself to us, and to the other students who were waiting. As I remember, there were girls in my class and many of them knew how to swim and I felt kind of embarrassed because they knew how and I didn’t.

Proficient in: Physical Education

“ Really polite, and a great writer! Task done as described and better, responded to all my questions promptly too! ”

I began to feel more at ease once I started to focus on what the instructor was saying to all of us and not being easily distracted by looking at the other advanced swimmers.

As we were all in the pool getting our swimming lessons using the rubber floats to help us stay afloat, I remember one of the other students had already taken the beginning class once before, took a kickboard and went splashing off by himself. I was told to hold on to the side of the pool and shown how to kick for the breaststroke. One by one, the teacher had us hold on to a kickboard while He pulled it through the water and we kicked. Pretty soon I was off doing this by myself, with confidence but still knowing that this was only a board holding me afloat and not the real eal yet. I still had some resistance about going under water and holding my breath , but the teacher was very patient with me and the other students that were just learning how to swim. After a couple of weeks more weeks, when I seemed to have caught on with my legs, she taught me the arm strokes. Now I had two things to concentrate on, my arms and my legs. I felt hopelessly uncoordinated. Sooner than I imagined, however, things began to feel “right” and I was able to swim! It was wonderful free feeling – like flying, maybe – to be able to shoot across the water.

Learning to swim was not easy for me, but in the end my persistence paid off. Not only did I learn how to swim and to conquer my fear of the water, but I also learned something about learning. Now when I am faced with a new situation I am not so nervous. I may feel uncomfortable to begin with, but I know that as I practice being in that situation and as my skills get better, I will feel more and more comfortable. It is a wonderful, free feeling when you achieve a goal you have set for yourself. (GE-102)-12. 20. 10 ENGLISH/WRITING COMPOSITION (ICDC. GE-102-12. 20. 10) > UNIT THREE ?

Cite this page

How I Learned To Swim Essay. (2019, Dec 05). Retrieved from https://paperap.com/paper-on-essay-how-i-learned-to-swim/

"How I Learned To Swim Essay." PaperAp.com , 5 Dec 2019, https://paperap.com/paper-on-essay-how-i-learned-to-swim/

PaperAp.com. (2019). How I Learned To Swim Essay . [Online]. Available at: https://paperap.com/paper-on-essay-how-i-learned-to-swim/ [Accessed: 1 Apr. 2024]

"How I Learned To Swim Essay." PaperAp.com, Dec 05, 2019. Accessed April 1, 2024. https://paperap.com/paper-on-essay-how-i-learned-to-swim/

"How I Learned To Swim Essay," PaperAp.com , 05-Dec-2019. [Online]. Available: https://paperap.com/paper-on-essay-how-i-learned-to-swim/. [Accessed: 1-Apr-2024]

PaperAp.com. (2019). How I Learned To Swim Essay . [Online]. Available at: https://paperap.com/paper-on-essay-how-i-learned-to-swim/ [Accessed: 1-Apr-2024]

- Learning To Swim Is A Short Story By Graham Swift Pages: 4 (1153 words)

- What I Have Learned Essay Pages: 2 (585 words)

- What I Learned From Stealing Essay Pages: 4 (1116 words)

- QuestionWhat have you learned from VAK system Week one? How will you Pages: 6 (1670 words)

- What I Learned This Semester Essays Pages: 4 (1029 words)

- Learned Behaviour Pages: 2 (561 words)

- Learned Helplessness Experiment 1965 Pages: 5 (1364 words)

- Learned Helplessness In Education Pages: 4 (1039 words)

- What I Learned From The Broken Spears Pages: 3 (754 words)

- The Leadership Skills and Patience I Learned from Working at Cousin's Subs Pages: 2 (378 words)

How I learned to swim

- In April, the writer Aaricka Washington set a goal that she would learn to swim before her 30th birthday.

- Inspired by Black women trailblazers such as Olympic gold medalist Simone Manuel, she took a leap of faith.

- See more stories on Insider's business page .

The moment I vowed to learn how to swim came in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

It was 2019. I was with a group of friends for a destination wedding in Mexico and we were on a little boat excursion having the time of our lives, drinking, eating, and taking pictures. The boat's captains stopped for a chance for us to swim.

Most of the wedding party seemed unafraid to jump in the water, so they put their life jackets on and jumped in.

Even though I had no idea how to swim, not even in the shallow end of a public pool, and had always had a visceral fear of being surrounded by water, the daredevil in me won out. I fastened my life jacket and decided that I would be courageous.

But as soon as my whole body met the ocean, I panicked. I'm by nature a control freak, and I had totally lost control. I didn't know what to do.

I wailed to my friends for help. Two of them, one on each side, helped guide me safely to shore, which looked like it was thousands of miles away. After what felt like hours, I fell to the ground, praising God's sand and land that welcomed me.

But what inspired me, two years later, to actually walk into my local Y and sign up for swimming classes? It could have been the adventurous friend I was trying to impress, who was shocked to learn I didn't know how to swim. It could have been that I was inspired to see Simone Manuel become the first African American woman to win an individual Olympic gold medal in swimming at the 2016 Rio Olympics. Or maybe it was the burst of determination I felt after reading Jazmine Hughes' personal essay in The New York Times about mastering swimming at the age of 28.

I know now that deciding to learn to swim was fueled by something more personal. I wanted to be able to sink my whole body in the water, and still feel in control.

Swimming is a life skill that everyone should know. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly 4,000 people die from drowning every year. When it comes to Black kids from 5-19 years old, the rates for drowning are 5.5 times higher than white kids in the same age group. A whopping 64% of African American children do not know how to swim, compared to 40% of white children.

Also, swimming always seemed like a luxurious way to relax. Not knowing how to be at total peace in water was something particularly frustrating to someone like me, who loves to accomplish challenging tasks. There was this freedom I was missing out on.

There's also a long, tragic history of institutionalized and structural racism in this country, where Black people were seen as dirty, ridden with communicable diseases and sexually threatening to white swimmers. Segregation , violence , and lack of funding and upkeep of public pools after integration kept Black people from enjoying the same privileges that white people experienced.

Racist pool operators were sometimes known to "suddenly declare some nebulous malfunction," as Snopes put it, or even drain the pools , rather than allow Black swimmers to take a dip (that kind of behavior was memorialized by actress Halle Berry in the 1999 movie Introducing Dorothy Dandridge ). There's a historic picture of James Brock, a Florida motel owner, pouring muriatic acid on a group of Black and white protesters who were staging a "swim-in" to integrate the pool.