- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Don’t Just Memorize Your Next Presentation — Know It Cold

- Sabina Nawaz

Learn it upside-down and backwards.

Knowing a script or presentation cold means taking the time to craft the words and sequence of what you plan to say, and then rehearsing them until you could recite them backwards if asked. It’s a more effective approach to public speaking than simple memorization or “winging it” because you plan not just the words but the actions and transitions between points, so it becomes one fluid motion for you, all the while allowing time for adjusting or improvising during the speech itself.

To learn your script cold, first, decide how you will craft your script, whether it’s noting key talking points or writing down every line and detail. Next, create natural sections and learn them individually, including transitions. Then, learn your script over time and rehearse. Finally, have a plan for forgetfulness, which can include acknowledging that you need to reference your notes.

The three judges beamed at me. Buoyed by their support, I anticipated winning this college elocution competition. I nailed the first verse of my chosen poem, but might as well have been under general anesthesia when trying to remember a single word of the second verse. Now the judges’ encouraging smiles only roiled my rising panic. Finally, the timer buzzed, ending my turn on stage and initiating a two-decade fear of memorization.

- Sabina Nawaz is a global CEO coach , leadership keynote speaker, and writer working in over 26 countries. She advises C-level executives in Fortune 500 corporations, government agencies, non-profits, and academic organizations. Sabina has spoken at hundreds of seminars, events, and conferences including TEDx and has written for FastCompany.com , Inc.com , and Forbes.com , in addition to HBR.org. Follow her on Twitter .

Partner Center

- Benefits of Public Speaking →

How Public Speaking Improves Critical Thinking Skills

In today’s fast-paced world, effective communication and critical thinking skills are essential for personal and professional success. Public speaking is one avenue that can significantly improve these crucial abilities, allowing individuals to excel in various aspects of their lives.

This blog post will explore the relationship between public speaking and critical thinking, revealing how honing your presentation skills can lead to enhanced reasoning abilities and better decision-making.

Key Takeaways

- Public speaking and critical thinking skills are intrinsically linked, as both require the ability to analyze and present information clearly.

- Practicing public speaking techniques such as research, active listening , and constructive feedback can enhance analytical abilities, boost cognitive flexibility, promote self-awareness and personal growth while improving problem-solving capabilities

- Improved communication skills through public speaking lead to clearer expression of ideas, better collaboration with team members in professional settings resulting in more effective discussions. In a personal context it builds confidence on stage & off increasing interpersonal relationships.

The Relationship Between Public Speaking And Critical Thinking

Public speaking and critical thinking are intricately linked, as both skills require the ability to analyze information and present it in a clear and compelling way. In essence, effective public speakers must possess sharp critical thinking abilities to craft persuasive arguments that resonate with their audience.

As a public speaker, you need solid critical thinking skills for many aspects of your presentation: from researching your subject matter thoroughly to crafting logical arguments backed by evidence.

Additionally, you must be able to anticipate potential counterarguments and have responses at the ready.

On the other hand, when honing your oratory capabilities through frequent practice sessions or watching others present, analyzing their techniques can sharpen your own analytical faculties.

In conclusion, public speaking offers an invaluable opportunity for personal growth; developing proficiency in this domain inherently cultivates sharper critical reasoning capacity—an essential component for success across various spheres of life.

Benefits Of Public Speaking For Developing Critical Thinking Skills

Public speaking helps improve critical thinking skills by enhancing communication abilities, increasing cognitive flexibility, boosting problem-solving capabilities, promoting self-awareness and personal growth.

Improved Communication

Public speaking can greatly improve communication skills, which is an important aspect of critical thinking. When giving a speech, one must consider their audience and tailor their message accordingly.

This involves being able to articulate thoughts clearly and concisely while also being engaging and persuasive.

Improving communication skills through public speaking not only benefits the speaker but also those around them in personal and professional settings. It allows for clearer expression of ideas, better collaboration with team members, and more effective problem-solving in group discussions.

Overall, public speaking provides ample opportunities for individuals to hone their communication skills – a crucial component for successful critical thinking that can be applied across various areas of life from work to personal relationships.

Enhanced Analytical Abilities

Through public speaking, individuals can develop enhanced analytical abilities that are essential for critical thinking. Analytical thinking involves breaking down complex concepts into smaller components and using logic to understand relationships between them.

When developing a speech, speakers must learn how to analyze their audience’s needs and interests in order to deliver content that resonates with them.

For example, when preparing a persuasive speech on environmental conservation, a speaker might use data analysis skills to understand the impact of human activity on ecosystems.

By practicing public speaking techniques such as these, individuals can enhance their analytical abilities in both personal and professional settings – making it easier for them to organize thoughts clearly, evaluate ideas rigorously, make informed decisions confidently – all important aspects of critical thinking.

Boosted Cognitive Flexibility

Public speaking can also boost cognitive flexibility, which refers to the ability to adapt and switch between various modes of thinking. When preparing for a speech, speakers need to consider different perspectives and approaches in order to present their arguments persuasively.

This requires an open-mindedness and willingness to embrace alternative viewpoints.

Through public speaking, individuals learn how to better manage and navigate complex situations by honing their cognitive flexibility skills. For example, when faced with questions from the audience or rebuttals from opponents during debates , speakers must think quickly on their feet while switching between logical reasoning, analytical thinking, creativity and persuasion techniques.

Increased Self-awareness And Personal Growth

Developing critical thinking skills through public speaking can lead to increased self-awareness and personal growth. By being exposed to a variety of perspectives, speakers are able to challenge their own assumptions and beliefs, leading to greater introspection and understanding of oneself.

Through this process, speakers also have the chance to gain a sense of accomplishment as they improve their skills over time. This newfound confidence can extend beyond just public speaking and positively impact other areas of life as well.

Improved Problem-solving

Another important benefit of public speaking for developing critical thinking skills is improved problem-solving. When preparing a speech or presentation, speakers are required to think creatively and critically about how to best communicate their message.

This involves identifying potential problems or challenges that may arise during the delivery and finding effective solutions.

For example, when delivering a persuasive speech on environmental issues, speakers must identify potential counterarguments that their audience may have and anticipate the objections before presenting their case convincingly.

Through regular practice with public speaking activities such as debates or presentations, individuals can hone these problem-solving abilities while also improving communication skills by learning how to articulate ideas clearly effectively.

Techniques To Improve Critical Thinking Through Public Speaking

To improve critical thinking through public speaking, techniques such as conducting thorough research, practicing active listening and constructive feedback, using logic and evidence to support arguments, embracing uncertainty and open-mindedness, and adapting to different audiences can be incredibly helpful.

Conducting Thorough Research

Conducting thorough research is an essential component of developing critical thinking skills through public speaking. Effective research requires analytical thinking and problem-solving skills, as well as the ability to evaluate sources for credibility and relevance.

For example, when preparing a speech on climate change, conducting in-depth research can help identify key issues and data points that support the argument for environmental conservation.

Research also allows for identifying potential counterarguments or opposing viewpoints beforehand so they can be addressed effectively during delivery. Utilizing credible sources such as academic journals or scientific studies helps establish the speaker’s credibility while giving their audience confidence in their message’s reliability.

Practicing Active Listening And Constructive Feedback

Active listening and constructive feedback are crucial skills for any public speaker looking to improve their critical thinking abilities. Active listening involves paying close attention to what the audience is saying, both verbally and non-verbally, in order to gain a better understanding of their perspectives and interests.

Constructive feedback entails providing helpful criticism that can assist public speakers in improving their presentations or speeches. This can involve highlighting areas where improvements could be made while also recognizing strengths.

Constructive feedback encourages growth and development in a safe environment, allowing public speakers to hone their skills over time.

Using Logic And Evidence To Support Arguments

As a public speaker, it is critical to back up your arguments with logical reasoning and evidence. Including these elements in your presentation helps to improve critical thinking skills by reinforcing the value of well-supported positions.

When crafting an argument, prioritize identifying key points that support your claim and use them as evidence throughout your speech.

In addition, using logic to support arguments helps create a sense of credibility and persuasion in speeches. This approach underscores the importance of making compelling cases that resonate with audiences and encourages active engagement throughout presentations.

Embracing Uncertainty And Open-mindedness

Another important technique to improve critical thinking through public speaking is embracing uncertainty and open-mindedness. Critical thinkers are not afraid of uncertainty and recognize that multiple perspectives exist on any given topic.

Embracing uncertainty also means being willing to change one’s views based on new information or evidence. Speakers who engage in debates or discussions with others should actively listen to opposing viewpoints and constructively critique them using logic and evidence.

For example, let’s say a speaker is giving a speech about climate change. Rather than dismissing opposing viewpoints outright, the speaker could consider why someone may have a different opinion and try to understand their perspective.

Adapting To Different Audiences

As a public speaker, it’s essential to understand that every audience is unique. Adapting to different audiences can help you connect with them effectively and make your speech more impactful.

For instance, if you’re giving a presentation to financial experts, using technical language might be appropriate. However, if you’re speaking to a general audience that has no prior knowledge of finances, simplifying complex concepts would be necessary.

By adapting to different audiences through critical thinking skills like research and active listening during presentations will increase chances for success when delivering speeches.

Additional Benefits Of Improving Critical Thinking Skills Through Public Speaking

Improved critical thinking skills through public speaking can lead to better decision making, enhanced creativity, and the development of leadership skills .

Improved Decision Making

Improving critical thinking skills through public speaking can lead to better decision-making abilities. When delivering a speech, it’s essential to analyze different perspectives and evidence to decide on the best approach.

Critical thinking helps in evaluating arguments effectively, separating irrelevant information from pertinent ones.

For instance, before giving an argumentative speech on climate change, it’s crucial for a speaker first to research the topic thoroughly and weigh the pros and cons of different solutions suggested by various scientists.

By analyzing each option critically, drawing logical conclusions based on research findings, they can build a persuasive speech that will influence their audience positively.

Better Problem Solving

Public speaking can improve problem-solving skills, which is a crucial aspect of critical thinking. When delivering a speech, speakers need to anticipate potential problems and find ways to address them effectively.

This mindset can also extend beyond public speaking and into daily life, helping individuals approach challenges in a more rational and logical way.

In addition, public speaking helps develop creativity by encouraging individuals to explore different perspectives and ideas. Through engaging with diverse audiences during speeches or debates, speakers learn how to think outside of conventional boundaries while maintaining sound reasoning behind their arguments.

Enhancing Creativity

Improving critical thinking skills through public speaking can also enhance one’s creativity. The ability to think critically allows individuals to approach problems and situations with an open mind, considering all possible solutions and perspectives.

For example, a speaker who has honed their critical thinking skills may be able to brainstorm unique analogies or metaphors that effectively convey complex concepts to their audience.

Similarly, they may be able to develop original arguments that offer fresh insights on important issues.

Furthermore, the process of preparing for a speech involves researching various sources of information from different angles. Engaging with diverse viewpoints helps foster creativity by providing new perspectives on familiar topics while introducing unknown factors into the mix.

Boosting Confidence

Public speaking can have a powerful impact on boosting confidence levels. When individuals enter the world of public speaking, they are inherently taking a risk by putting themselves in front of an audience.

However, with practice and exposure to different audiences, individuals can become more comfortable and confident in their abilities to communicate effectively.

In addition, public speaking courses often provide opportunities for constructive feedback from instructors and peers. This feedback allows individuals to identify their strengths and weaknesses, providing them with the knowledge needed to improve both their delivery and content moving forward.

Furthermore, receiving positive feedback from an audience after a successful speech can be incredibly rewarding and contribute significantly to one’s confidence levels.

Developing Leadership Skills

Improving critical thinking through public speaking can also help develop valuable leadership skills. By learning to analyze the audience, adapt to different communication styles and effectively convey ideas, speakers are more likely to gain respect and trust from their listeners.

Public speaking provides a platform for individuals to practice decision-making, problem-solving, and strategic planning in an effective manner.

Moreover, mastering rhetoric techniques such as persuasion and argumentation enhances one’s ability to influence others positively in personal or professional settings. By developing analytical thinking skills and leveraging them with creative presentation techniques, expert speakers know exactly how they can motivate people towards action or change behavior patterns with great ease.

Conclusion: Public Speaking Improves Critical Thinking Skills

In conclusion, public speaking is a valuable tool for improving critical thinking skills. By enhancing communication abilities and analytical thinking, individuals can become more persuasive and effective speakers.

Through techniques such as thorough research, active listening, and constructive feedback, public speakers can develop the logic and evidence needed to support their arguments effectively.

With increased self-awareness and personal growth also comes improved problem-solving capabilities that are essential in both professional and personal contexts.

1. How does public speaking improve critical thinking skills?

Public speaking requires individuals to analyze and organize their thoughts in a clear and concise manner , which can improve their ability to think critically about complex topics and arguments.

2. Can public speaking help me develop better problem-solving skills?

Yes, by practicing public speaking, you are forced to consider multiple perspectives on an issue or topic, which can help you develop stronger problem-solving skills that enable you to identify potential solutions more quickly.

3. What are some techniques I can use during public speaking to challenge my critical thinking abilities?

Using analogies and metaphors, posing hypothetical scenarios, incorporating statistics and data into your presentation, asking thought-provoking questions or even employing rhetorical devices like repetition or contrast can stimulate deeper analysis of a topic or argument.

4. How do the benefits of improved critical thinking acquired through public speaking carry over into other areas of life?

Improved critical thinking skills make it easier for individuals to evaluate information more effectively across all aspects of life from making important decisions at work/school or analyzing current events happening within global political/economic landscape in order understand different viewpoints & draw one’s own conclusions based upon evidence available.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 3: Speaking Confidently

Battling nerves and the unexpected.

Ron Bulovs – Speech! – CC BY 2.0.

One of your biggest concerns about public speaking might be how to deal with nervousness or unexpected events. If that’s the case, you’re not alone—fear of speaking in public consistently ranks at the top of lists of people’s common fears. Some people are not joking when they say they would rather die than stand up and speak in front of a live audience. The fear of public speaking ranks right up there with the fear of flying, death, and spiders (Wallechinsky, Wallace, & Wallace, 1977). Even if you are one of the fortunate few who don’t typically get nervous when speaking in public, it’s important to recognize things that can go wrong and be mentally prepared for them. On occasion, everyone misplaces speaking notes, has technical difficulties with a presentation aid, or gets distracted by an audience member. Speaking confidently involves knowing how to deal with these and other unexpected events while speaking.

In this chapter, we will help you gain knowledge about speaking confidently by exploring what communication apprehension is, examining the different types and causes of communication apprehension, suggesting strategies you can use to manage your fears of public speaking, and providing tactics you can use to deal with a variety of unexpected events you might encounter while speaking.

Wallechinsky, D., Wallace, I., & Wallace, A. (1977). The people’s almanac presents the book of lists . New York, NY: Morrow. See also Boyd, J. H., Rae, D. S., Thompson, J. W., Burns, B. J., Bourdon, K., Locke, B. Z., & Regier, D. A. (1990). Phobia: Prevalence and risk factors . Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology , 25 (6), 314–323.

Stand up, Speak out Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

44 Critical Thinking Skills

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the role that logic plays in critical thinking

- Explain how critical thinking skills can be used to problem-solve

- Describe how critical thinking skills can be used to evaluate information

- Identify strategies for developing yourself as a critical thinker

Thinking comes naturally. You don’t have to make it happen—it just does. But you can make it happen in different ways. For example, you can think positively or negatively. You can think with “heart” and you can think with rational judgment. You can also think strategically and analytically, and mathematically and scientifically. These are a few of the multiple ways in which the mind can process thought.

What are some forms of thinking you use? When do you use them, and why?

As a college student, you are tasked with engaging and expanding your thinking skills. One of the most important of these skills is critical thinking. Critical thinking is important because it relates to nearly all tasks, situations, topics, careers, environments, challenges, and opportunities. It’s a “domain-general” thinking skill—not a thinking skill that’s reserved for a one subject alone or restricted to a particular subject area.

Great leaders have highly attuned critical thinking skills, and you can, too. In fact, you probably have a lot of these skills already. Of all your thinking skills, critical thinking may have the greatest value.

What Is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking is clear, reasonable, reflective thinking focused on deciding what to believe or do. It means asking probing questions like, “How do we know?” or “Is this true in every case or just in this instance?” It involves being skeptical and challenging assumptions, rather than simply memorizing facts or blindly accepting what you hear or read.

Imagine, for example, that you’re reading a history textbook. You wonder who wrote it and why, because you detect certain biases in the writing. You find that the author has a limited scope of research focused only on a particular group within a population. In this case, your critical thinking reveals that there are “other sides to the story.”

Who are critical thinkers, and what characteristics do they have in common?

- Critical thinkers are usually curious and reflective people. They like to explore and probe new areas and seek knowledge, clarification, and new solutions. They ask pertinent questions, evaluate statements and arguments, and distinguish between facts and opinion. They are also willing to examine their own beliefs, possessing a manner of humility that allows them to admit a lack of knowledge or understanding when needed. They are open to changing their mind. Perhaps most of all, they actively enjoy learning, and seeking new knowledge is a lifelong pursuit.

This may well be you!

No matter where you are on the road to being a critical thinker, you can always more fully develop and finely tune your skills. Doing so will help you develop more balanced arguments, express yourself clearly, read critically, and glean important information efficiently. Critical thinking skills will help you in any profession or any circumstance of life, from science to art to business to teaching. With critical thinking, you become a clearer thinker and problem solver.

Critical Thinking and Logic

Critical thinking is fundamentally a process of questioning information and data. You may question the information you read in a textbook, or you may question what a politician or a professor or a classmate says. You can also question a commonly-held belief or a new idea. With critical thinking, anything and everything is subject to question and examination for the purpose of logically constructing reasoned perspectives.

What Is Logic, and Why Is It Important in Critical Thinking?

The word logic comes from the Ancient Greek logike , referring to the science or art of reasoning. Using logic, a person evaluates arguments and reasoning and strives to distinguish between good and bad reasoning, or between truth and falsehood. Using logic, you can evaluate ideas or claims people make, make good decisions, and form sound beliefs about the world. [1]

Questions of Logic in Critical Thinking

Let’s use a simple example of applying logic to a critical-thinking situation. In this hypothetical scenario, a man has a PhD in political science, and he works as a professor at a local college. His wife works at the college, too. They have three young children in the local school system, and their family is well known in the community. The man is now running for political office. Are his credentials and experience sufficient for entering public office? Will he be effective in the political office? Some voters might believe that his personal life and current job, on the surface, suggest he will do well in the position, and they will vote for him. In truth, the characteristics described don’t guarantee that the man will do a good job. The information is somewhat irrelevant. What else might you want to know? How about whether the man had already held a political office and done a good job? In this case, we want to ask, How much information is adequate in order to make a decision based on logic instead of assumptions?

The following questions, presented in Figure 1, below, are ones you may apply to formulating a logical, reasoned perspective in the above scenario or any other situation:

- What’s happening? Gather the basic information and begin to think of questions.

- Why is it important? Ask yourself why it’s significant and whether or not you agree.

- What don’t I see? Is there anything important missing?

- How do I know? Ask yourself where the information came from and how it was constructed.

- Who is saying it? What’s the position of the speaker and what is influencing them?

Problem-Solving

For most people, a typical day is filled with critical thinking and problem-solving challenges. In fact, critical thinking and problem-solving go hand-in-hand. They both refer to using knowledge, facts, and data to solve problems effectively. But with problem-solving, you are specifically identifying, selecting, and defending your solution. Below are some examples of using critical thinking to problem-solve:

- Your roommate was upset and said some unkind words to you, which put a crimp in the relationship. You try to see through the angry behaviors to determine how you might best support the roommate and help bring the relationship back to a comfortable spot.

- Your campus club has been languishing on account of a lack of participation and funds. The new club president, though, is a marketing major and has identified some strategies to interest students in joining and supporting the club. Implementation is forthcoming.

- Your final art class project challenges you to conceptualize form in new ways. On the last day of class when students present their projects, you describe the techniques you used to fulfill the assignment. You explain why and how you selected that approach.

- Your math teacher sees that the class is not quite grasping a concept. She uses clever questioning to dispel anxiety and guide you to new understanding of the concept.

- You have a job interview for a position that you feel you are only partially qualified for, although you really want the job and you are excited about the prospects. You analyze how you will explain your skills and experiences in a way to show that you are a good match for the prospective employer.

- You are doing well in college, and most of your college and living expenses are covered. But there are some gaps between what you want and what you feel you can afford. You analyze your income, savings, and budget to better calculate what you will need to stay in college and maintain your desired level of spending.

Evaluating Information

Evaluating information can be one of the most complex tasks you will be faced with in college. But if you utilize the following four strategies, you will be well on your way to success:

- Read for understanding by using text coding

- Examine arguments

- Clarify thinking

- Cultivate “habits of mind”

Examine Arguments

When you examine arguments or claims that an author, speaker, or other source is making, your goal is to identify and examine the hard facts. You can use the spectrum of authority strategy for this purpose. The spectrum of authority strategy assists you in identifying the “hot” end of an argument—feelings, beliefs, cultural influences, and societal influences—and the “cold” end of an argument—scientific influences.

Clarify Thinking

When you use critical thinking to evaluate information, you need to clarify your thinking to yourself and likely to others. Doing this well is mainly a process of asking and answering probing questions, such as the logic questions discussed earlier. Design your questions to fit your needs, but be sure to cover adequate ground. What is the purpose? What question are we trying to answer? What point of view is being expressed? What assumptions are we or others making? What are the facts and data we know, and how do we know them? What are the concepts we’re working with? What are the conclusions, and do they make sense? What are the implications?

Cultivate “Habits of Mind”

“Habits of mind” are the personal commitments, values, and standards you have about the principle of good thinking. Consider your intellectual commitments, values, and standards. Do you approach problems with an open mind, a respect for truth, and an inquiring attitude? Some good habits to have when thinking critically are being receptive to having your opinions changed, having respect for others, being independent and not accepting something is true until you’ve had the time to examine the available evidence, being fair-minded, having respect for a reason, having an inquiring mind, not making assumptions, and always, especially, questioning your own conclusions—in other words, developing an intellectual work ethic. Try to work these qualities into your daily life.

Developing Yourself as a Critical Thinker

Critical thinking is a desire to seek, patience to doubt, fondness to meditate, slowness to assert, readiness to consider, carefulness to dispose and set in order; and hatred for every kind of imposture. —Francis Bacon, philosopher

Critical thinking is a fundamental skill for college students, but it should also be a lifelong pursuit. Below are additional strategies to develop yourself as a critical thinker in college and in everyday life:

- Reflect and practice : Always reflect on what you’ve learned. Is it true all the time? How did you arrive at your conclusions?

- Use wasted time : It’s certainly important to make time for relaxing, but if you find you are indulging in too much of a good thing, think about using your time more constructively. Determine when you do your best thinking and try to learn something new during that part of the day.

- Redefine the way you see things : It can be very uninteresting to always think the same way. Challenge yourself to see familiar things in new ways. Put yourself in someone else’s shoes and consider things from a different angle or perspective. If you’re trying to solve a problem, list all your concerns: what you need in order to solve it, who can help, what some possible barriers might be, etc. It’s often possible to reframe a problem as an opportunity. Try to find a solution where there seems to be none.

- Analyze the influences on your thinking and in your life : Why do you think or feel the way you do? Analyze your influences. Think about who in your life influences you. Do you feel or react a certain way because of social convention, or because you believe it is what is expected of you? Try to break out of any molds that may be constricting you.

- Express yourself : Critical thinking also involves being able to express yourself clearly. Most important in expressing yourself clearly is stating one point at a time. You might be inclined to argue every thought, but you might have greater impact if you focus just on your main arguments. This will help others to follow your thinking clearly. For more abstract ideas, assume that your audience may not understand. Provide examples, analogies, or metaphors where you can.

- Enhance your wellness : It’s easier to think critically when you take care of your mental and physical health. Try taking 10-minute activity breaks to reach 30 to 60 minutes of physical activity each day . Try taking a break between classes and walk to the coffee shop that’s farthest away. Scheduling physical activity into your day can help lower stress and increase mental alertness. Also, do your most difficult work when you have the most energy . Think about the time of day you are most effective and have the most energy. Plan to do your most difficult work during these times. And be sure to reach out for help . If you feel you need assistance with your mental or physical health, talk to a counselor or visit a doctor.

Key Takeaways

Critical thinking is a skill that will help speakers further develop their arguments and position their speech in a strong manner.

- Critical thinking utilizes thought, plan, and action. Be sure to consider the research at-hand and develop an argument that is logical and connects to the audience.

- It is important to conduct an audience analysis to understand the ways in which your research and argument will resonate with the group you are delivering your information to; you can strengthen your argument by accurately positioning your argument and yourself in within a diverse audience.

- “Student Success-Thinking Critically In Class and Online.” Critical Thinking Gateway. St Petersburg College, n.d. Web. 16 Feb 2016. ↵

Public Speaking Copyright © by Dr. Layne Goodman; Amber Green, M.A.; and Various is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Critical Thinking and Reasoning

Critical thinking.

We are approaching a new age of synthesis. Knowledge cannot be merely a degree or a skill…it demands a broader vision, capabilities in critical thinking and logical deduction, without which we cannot have constructive progress. – Li Ka Shing

Critical thinking has been defined in numerous ways. At its most basic, we can think of critical thinking as active thinking in which we evaluate and analyze information in order to determine the best course of action. We will look at more expansive definitions of critical thinking and its components in the following pages.

Before we get there, though, let’s consider a hypothetical example of critical thinking in action.

Shonda was researching information for her upcoming persuasive speech. Her goal with the speech was to persuade her classmates to drink a glass of red wine every day. Her argument revolved around the health benefits one can derive from the antioxidants found in red wine. Shonda found an article reporting the results of a study conducted by a Dr. Gray. According to Dr. Gray’s study, drinking four or more glasses of wine a day will help reduce the chances of heart attack, increase levels of good cholesterol, and help in reducing unwanted fat. Without conducting further research, Shonda changed her speech to persuade her classmates to drink four or more glasses of red wine per day. She used Dr. Gray’s study as her primary support. Shonda presented her speech in class to waves of applause and support from her classmates. She was shocked when, a few weeks later, she received a grade of “D”. Shonda’s teacher had also found Dr. Gray’s study and learned it was sponsored by a multi-national distributor of wine. In fact, the study in question was published in a trade journal targeted to wine and alcohol retailers. If Shonda had taken a few extra minutes to critically examine the study, she may have been able to avoid the dreaded “D.”

Shonda’s story is just one of many ways that critical thinking impacts our lives. Throughout this chapter we will consider the importance of critical thinking in all areas of communication, especially public speaking. We will first take a more in-depth look at what critical thinking is—and isn’t.

Before we get too far into the specifics of what critical thinking is and how we can do it, it’s important to clear up a common misconception. Even though the phrase critical thinking uses the word “critical,” it is not a negative thing. Being critical is not the same thing as criticizing. When we criticize something, we point out the flaws and errors in it, exercising a negative value judgment on it. Our goal with criticizing is less about understanding than about negatively evaluating. It’s important to remember that critical thinking is not just criticizing. While the process may involve examining flaws and errors, it is much more.

Critical Thinking Defined

“John Dewey” by Eva Watson-Schütze. Public domain.

Just what is critical thinking then? To help us understand, let’s consider a common definition of critical thinking. The philosopher John Dewey, often considered the father of modern day critical thinking, defines critical thinking as:

“Active, persistent, careful consideration of a belief or supposed form of knowledge in light of the grounds that support it and the further conclusions to which it tends.” [1]

The first key component of Dewey’s definition is that critical thinking is active. Critical thinking must be done by choice. As we continue to delve deeper into the various facets of critical thinking, we will learn how to engage as critical thinkers.

Probably one of the most concise and easiest to understand definitions is that offered by Barry Beyer: “Critical thinking… means making reasoned judgments.” [2] In other words, we don’t just jump to a conclusion or a judgment. We rationalize and justify our conclusions. A second primary component of critical thinking, then, involves questioning. As critical thinkers, we need to question everything that confronts us. Equally important, we need to question ourselves and ask how our own biases or assumptions influence how we judge something.

In the following sections we will explore how to do critical thinking more in depth. As you read through this material, reflect back on Dewey’s and Beyer’s definitions of critical thinking.

- Dewey, J. (1933). Experience and education . New York: Macmillan, 1933. ↵

- Beyer, B. K. (1995) Critical thinking. Bloomington, IN: Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation. ↵

- Chapter 6 Critical Thinking. Authored by : Terri Russ, J.D., Ph.D.. Provided by : Saint Mary's College, Notre Dame, IN. Located at : http://publicspeakingproject.org/psvirtualtext.html . Project : The Public Speaking Project. License : CC BY-NC-ND: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives

- John Dewey in 1902. Authored by : Eva Watson-Schutze. Located at : http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:John_Dewey_in_1902.jpg . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

1 Thinking about Public Speaking

What is Public Speaking?

In this chapter . . .

What’s your mental picture when you think about public speaking ? The President of the United States delivering an inaugural address? A sales representative seeking to persuade clients in a board room? Your minister, priest, or rabbi presenting a sermon at a worship service? Your professor lecturing? A dramatic courtroom scene? Politicians debating before an election? A comedian doing stand-up at a night club?

All of these and more are instances of public speaking. Public speaking takes many forms every day in our country and across the world.

Public Speaking vs. Everyday Conversation

What do we mean by “public speaking?” The most obvious answer is “talking in front of a group of people.” Public speaking is more formal than that. Public speaking is an organized, face-to-face, prepared, intentional (purposeful) attempt to inform, entertain, or persuade a group of people (usually five or more) through words, physical delivery, and (at times) visual or audio aids. In almost all cases, the speaker is the focus of attention for a specific amount of time. There still may be some back-and-forth interaction, such as questions and answers with the audience, but the speaker usually holds the responsibility to direct that interaction.

Although we communicate all the time, public speaking is bigger than everyday conversation. Public speaking is purposeful (to entertain, inform, or persuade your audience). Speeches are highly organized with certain formal elements (introduction and clear main points, for example). They are usually dependent on resources outside of your personal experience (research to support your ideas).

Unlike conversation, speech delivery is “enlarged” or “projected” as well—louder, more fluid, and more energetic, depending on the size and type of room in which you’re speaking—and you’ll be more conscious of the correctness and formality of your language. You might say, “That sucks” in a conversation but are less likely to do so in front of a large audience in certain situations. If you can keep in mind the basic principle that public speaking is formalized communication with an audience designed to achieve mutual understanding for mutual benefit (like a conversation), you’ll be able to relate to your audience on a human and personal level.

There is a cultural practice that achieves this same goal of communication: performance.

What is Performance?

There are multiple meanings of the word performance . The most common use of the word refers to a cultural event that is prepared for an audience. These are live events like theatre, dance, a circus, or a concert. We say, “I’m going to a theatre performance” or a “performance of a concert.” Related to this, performance also means the effort of the artist at these events. For example, we say the “actor performs,” or the “musician performs.”

Another common meaning of performance is achievement, as in how well one performs their job. We use phrases like “the student’s performance” or “that athlete performs well in competition.” This is performance as achievement or ability.

There’s yet another meaning that is interesting because it has a negative connotation: performance as something fake or presentational. In this sense, performing means a person isn’t authentic, not real, just playing a game, just acting.

Finally—and this is the definition that most applies to public speaking—we use performance to speak of how we present ourselves in the fulfillment of a designated social role. Shakespeare said, “All the world’s a stage and all the men and women merely players” ( As You Like It ). The idea is that on the stage of life, we are all actors. We should ask, therefore, what role are we playing? The answer is: many, many roles. Over the course of a few days or even just a single day, you play several roles. Starting in the morning, you’re showing yourself as a hard-working student in the classroom; over lunch you behave as a friend; you go to work and fulfill your role as a good employee; your parent call and you play the obedient child as you ask for gas money. As we circulate through these different social situations, we perform distinct roles. Taking it further, you can see that we perform not only social roles, but our very identity. Gender identity is one such performance.

Performance in Everyday Life

How did this broad concept of performance come about? In 1956, the Canadian sociologist Erving Goffman published a book called The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. The idea of how we present ourselves—perform ourselves—caught on for sociologists, psychologists, cultural anthropologists, and others who study theatre. Lived experience confirmed what felt like common sense: identity is flexible. How we think of ourselves changes with the situations we move through with other human beings.

There is an extension of this idea that is even more interesting. Namely, how we perform these roles isn’t original. Our performed behaviors are part of previously performed behaviors. Think about the way people behave at sporting events. There are special cheers and gestures, face painting, and chants. You couldn’t know how to perform at a sporting event unless these behaviors had been already performed, right? Put another way: each time a crowd gathers to enjoy the game, they are reenacting previously performed behaviors. Another example of this is a marriage ceremony. Marriage ceremonies rely on previously scripted behaviors. If you had a ceremony that was completely original, it wouldn’t be recognized by attendees as a marriage ceremony at all unless it contained some conventional elements.

If our stream of everyday performances is based on already-existing performances, how did we learn them? Did we study them? Obviously not. We learned them like we learned language: naturally and by example.

Public Speaker is a Social Role

This textbook is called Public Speaking as Performance to highlight the central idea that speaking in public is a social role that we perform upon invitation and under specific circumstances. Like all roles, this performance takes its instructions from previously performed examples.

Public speaking has reliable, repeatable behaviors. You know most of them already. How do speakers walk to the front of a room? How do they stand at a podium? What kinds of hand gestures do speakers typically use? These are common to the practice of public speaking. You’ve witnessed them throughout your life and already have the building blocks for that special type of role-playing we call public speaking.

The Communication Process

Human beings communicate with each other all the time and continually, but we don’t give much thought to exactly how it’s that we successfully get our messages across. How do we understand each other? Are we saying what we mean? How does one person speak to many? How does a speaker know they are being understood?

There are several fields of university research that study how communication works. Linguistics, for example, looks at how human languages function. Communication Studies examines a range of communication styles from small group interpersonal interactions to the communicative force of mass media. Departments of Philosophy, Classics, and Psychology each have their way of talking about the communication process. Artists in both the visual and performing arts also think about how they communicate with their audiences.

The Communication Studies Model

According to research in the field of Communication Studies, human communication aims to share meaning between two or more people. The process is composed of certain required elements:

- Senders and receivers (people)

- Outcome/result

In public speaking, it’s common to call one person (the speaker) the “ sender ” and the audience the “ receiver. ” In the real world, it’s not always as simple as that. Sometimes the speaker initiates the message, but other times the speaker is responding to the audience’s initiation. It’s enough to say that the sender and receiver exchange roles sometimes and both are as necessary as the other to the communication process.

Human communication takes place within a context , meaning the circumstances in which a speech happens. Context can have many levels, with several going on at the same time in any communication act.

- Historical, or what has gone on between the sender(s) and receiver(s) before the speech. The historical elements can be positive or negative, recent, or further back in time.

- Cultural, which sometimes refers to the country where someone was born and raised but can also include ethnic, racial, religious, and regional cultures or co-cultures.

- Social, or what kind of relationship the sender(s) and receiver(s) are involved in, such as teacher-student, co-workers, employer-employee, or members of the same civic organization, faith, profession, or community.

- Physical, which involves where the communication is taking place and the attributes of that location. The physical context can have cultural meaning (a famous shrine or monument) that influences the form and purpose of the communication, or attributes that influence audience attention (temperature, seating arrangements, or external noise).

Each one of these aspects of context bears upon how we behave as a communicator and specifically a public speaker.

Third, human communication of any kind involves a message . That message may be informal and spontaneous, such as small talk with a seatmate on a plane, conversing for no other reason than to have someone to talk to and be pleasant. On the other hand, it might be very formal, intentional, and planned, such as a commencement address.

Fourth, public speaking, like all communication, requires a channel . Channel is how the message gets from sender to receiver. In interpersonal human communication, we see each other and hear each other, in the same place and time. In mediated or mass communication, some sort of machine or technology (tool) comes between the people—phone, radio, television, printing press and paper, or computer.

The fifth element of human communication is feedback , which in public speaking is usually nonverbal, such as head movement, facial expressions, laughter, eye contact, posture, and other behaviors that we use to judge audience involvement, understanding, and approval. These types of feedback can be positive (nodding, sitting up, leaning forward, smiling) or less than positive (tapping fingers, fidgeting, lack of eye contact, checking devices).

The sixth element of human communication is noise , which might be considered any disruption that interrupts or interferes in the communication. Some amount of noise is almost always present due to the complexity of human behavior and context. Some categories of noise include:

- something in the room or physical environment keeps them from attending to or understanding a message.

- the receiver(s)’ health affects their understanding of the message, or the sender’s physical state affects her ability to be clear and have good delivery.

- the receiver(s) or sender(s) have stress, anxiety, past experiences, personal concerns, or some other psychological issue that prevents the audience from receiving an intended message.

This brief list of three types of noise isn’t exhaustive, but it’s enough to point out that many things can “go wrong” in a public speaking situation. However, the reason for studying public speaking is to become aware of the potential for these limitations or noise factors, to determine if they could happen during your speech, and take care of them.

The final element of the communication process is outcome or result, which means a change in either the audience or the context. For example, if you ask an audience to consider becoming bone marrow donors, there are certain outcomes. They will either have more information about the subject and feel more informed; they will disagree with you; they will take in the information but not follow through with any action; or they will decide it’s a good idea to become a donor and go through the steps to do so.

Let’s apply this model of communication to the situation of public speaking. It looks like this:

The speaker is a sender within a specific speaking context , who originates and creates a structured message and sends it through the visual or oral channel using symbols and nonverbal means to the receivers who are the members of the audience. They provide (mostly nonverbal) feedback . The speaker and audience may or may not be aware of the types of interference or noise that exist, and the speaker may try to deal with them. As an outcome of public speaking, the audience’s minds, emotions, and/or actions are affected, and possibly the speaker’s as well.

Now that you understand one model of the process of human communication, let’s consider another model. This model comes from the kind of communication that we see in performances such as theatre.

The Theatrical Model of Communication

First, let’s remember the seven elements of communication you have already learned: senders and receivers, context, message, channel, noise, feedback, and outcome. It’s all rather technical, isn’t it? Senders and receivers sound like a cell tower. Message might make you think of sending a text. Channel is a word we use to talk about TV or radio—like a streaming channel. Noise and feedback are associated with sounds that machines make like a bad amplifier or a broken microphone.

Obviously, we’re not communication machines. Is there another model for the process of communication? Theatre performance is an alternative. The elements of theatrical communication are actors and audience, circumstances, story, stage, audience reaction, obstacles, and effect.

Theatrical Model vs. Communication Model

Instead of a metaphor in which speakers and listeners are like a cell tower sending and receiving messages, imagine instead that communication involves actors who tell stories and an audience who listens, hopefully in rapt attention. Even though actors may have something called stage fright, they work through it because they owe it to their audiences to tell the story. As for the audience, these are people who have come willingly to listen. The occasion matters to them. Probably they paid for a ticket. Maybe they dressed up for the occasion. It doesn’t matter how they came together, but it’s that special meeting, essential to the nature of being human, between those who have a story to tell and those who have come to listen.

Now, let’s look at the element of context. Context is akin to something that actors and directors call given circumstances . The given circumstances are everything that we know about the situation in which a story and the storytelling takes place. Every play has a unique set of given circumstances. When creating a theatre production, the entire team analyzes a script to understand all the elements of the world of the play.

Instead of message, think more broadly about the word meaning . When we ask, “what does that word mean?”, we are using one sense of that word. But when we say, “You mean so much to me,” then we are using the word in the sense of important or significant. Why would actors be speaking if they didn’t have something meaningful to say? Why would a playwright write a play if there wasn’t meaning in it? How could a theatre group expect audiences to buy tickets if not with the promise of meaning? Much more than a message, meaning reminds us that speaking and listening matter.

The stage could be thought of as a channel. When we talk about a stage, we usually mean a separate space, one that is different from the space of the audience. Sometimes it’s higher than the audience to make it easier to see, but that isn’t a requirement. Actors use the term taking stage to describe when a person has separated themselves from the group, implying, “Hey, look at me for a few minutes. I have something to say!” Taking stage is a very human and powerful thing to do.

In theatre, actors want to be understood. Actors pay close attention to audience reaction . Often, actors can’t see the audience because of the lights, so they must pay close attention to feedback like laughter and applause, but also to more subtle audience signals like coughing and moving. This feedback might change the energy of the actors, or cause them to speak louder, or to take more pauses for laughter. Actors and public speakers alike are in a dialogue with the audience.

What about those distractions called “noise”? In the theatre, we speak instead about obstacles . Obstacles refer to anything that stands in the way of a person fully communicating with another. Instead of seeing noise as something negative, actors understand that obstacles are the beating heart of drama. Drama wouldn’t exist without people struggling to communicate with each other!

Finally, there is effect . The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle believed that the effect of theatre was to allow an audience to experience strong emotions, so that they would be cleansed of these emotions when they emerged again into real life. In public speaking there are different goals, depending on the purpose of the speech. However, they are all connected to these questions: What is the effect we hope to have on our audience?

Both the theatrical model of communication and the communication studies model of communication have their advantages. In the theatrical model, we have people who want to speak and people who want to listen. We have circumstances that tell us who, what, where, why, and why we’re speaking. Theatre tells a story that is meaningful. In the theatre, actors take stage, even when they are frightened, as a way of saying “Look at me. I have something to say.” They establish a dialogue with the audience by listening to their reaction. Obstacles are inherent to the process of human interaction, but in the end, we hope we have an effect.

To conclude, you may find it productive to consider these lessons taken from what performers know about communication:

- It all begins with the desire to speak and be heard.

- The audience has made an effort to be there. Respect that effort.

- Stories worth telling are stories that are meaningful.

- Consider all the given circumstances.

- Don’t be afraid to take the stage. It’s the only way to tell the story.

- Communication isn’t guaranteed. There will be obstacles.

- Performers are in dialogue with an audience. Communication is a two-way street.

- Whether big or small, you can have your performance make a difference.

Why Practice Public Speaking?

Do you see yourself as a public speaker? And when you do, do you see yourself as confident, prepared, and effective? Or do you see a person who is nervous, unsure of what to say, and feeling as if they are failing to get their message across? You find yourself in this public speaking course and probably have mixed emotions. Public speaking instruction may have been part of your high school experience. Maybe you competed in debates or individual speaking events, or you have acted in plays. These activities can help you in this course, especially in terms of confidence and delivery. On the other hand, it might be that the only public speaking experience you have had felt like a failure and therefore left you embarrassed and wanting to forget it and stay far away from public speaking. This class isn’t something you have been looking forward to, and you may have put it off. Maybe your attitude is, “Let’s just get it over with.” These are understandable emotions because, as you have probably heard or read, polls indicate public speaking is one of the things people fear the most.

Benefits of Practicing Public Speaking

First, public speaking is one of the major communication skills desired by employers. Employers are frequently polled regarding the skills they most want employees to possess, and communication is almost always in the top three (Adams, 2014). Of course, “communication skills” is a broad term and involves several abilities such as team leadership, clear writing in business formats, conflict resolution, interviewing, and listening. However, public speaking is one of those sought-after skills, even in fields where the entry-level workers may not do much formal public speaking. Nurses give training presentations to parents of newborn babies; accountants advocate for new software in their organizations; managers lead team meetings.

If you’re taking this class at the beginning of your college career, you’ll benefit in your future classes from the research, organizational, and presentational skills learned here. First-year college students enter with many expectations of college life and learning that they need to “un-learn,” and one of those is the expectation that they will not have to give oral presentations in classes. However, that is wishful thinking. Different kinds of presentations will be common in your upcoming classes.

Another reason for taking a public speaking course is the harder-to-measure but valuable personal benefits. As an article on the USA Today College website states, a public speaking course can help you be a better, more informed, and critical listener; it can “encourage you to voice your ideas and take advantage of the influence you have;” and it gives you an opportunity to face a major fear you might have in a controlled environment (Massengale, 2014). Finally, the course can attune you to the power of public speaking to change the world. Presentations that lead to changes in laws, policies, leadership, and culture happen every day, all over the world.

To improve your public speaking, it’s useful to be conscious of what you notice about other public speakers. What particular traits make them effective? How can you emulate this? Even with less effective speakers, you can take note of pitfalls you want to avoid in your own speeches. Being able to critique other speeches makes it easier to critique your own performance. As you begin this journey of improving your public speaking, commit to being more aware of how people communicate and what you can learn from it. Below are some reflections that will help you get started.

Something to Think About

- Who are some public speakers you admire? Why? (Don’t name deceased historical figures whom you have not heard personally or face-to-face.)

- What behavior done by public speakers “drives you nuts,” that is, creates “noise” for you in listening to them?

- When this class is over, what specific skills do you want to develop as a communicator?

Public Speaking as Performance Copyright © 2023 by Mechele Leon is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

71 Critical Thinking

We are approaching a new age of synthesis. Knowledge cannot be merely a degree or a skill…it demands a broader vision, capabilities in critical thinking and logical deduction, without which we cannot have constructive progress. – Li Ka Shing

Critical thinking has been defined in numerous ways. At its most basic, we can think of critical thinking as active thinking in which we evaluate and analyze information in order to determine the best course of action. We will look at more expansive definitions of critical thinking and its components in the following pages.

Before we get there, though, let’s consider a hypothetical example of critical thinking in action.

Shonda was researching information for her upcoming persuasive speech. Her goal with the speech was to persuade her classmates to drink a glass of red wine every day. Her argument revolved around the health benefits one can derive from the antioxidants found in red wine. Shonda found an article reporting the results of a study conducted by a Dr. Gray. According to Dr. Gray’s study, drinking four or more glasses of wine a day will help reduce the chances of heart attack, increase levels of good cholesterol, and help in reducing unwanted fat. Without conducting further research, Shonda changed her speech to persuade her classmates to drink four or more glasses of red wine per day. She used Dr. Gray’s study as her primary support. Shonda presented her speech in class to waves of applause and support from her classmates. She was shocked when, a few weeks later, she received a grade of “D”. Shonda’s teacher had also found Dr. Gray’s study and learned it was sponsored by a multi-national distributor of wine. In fact, the study in question was published in a trade journal targeted to wine and alcohol retailers. If Shonda had taken a few extra minutes to critically examine the study, she may have been able to avoid the dreaded “D.”

Shonda’s story is just one of many ways that critical thinking impacts our lives. Throughout this chapter we will consider the importance of critical thinking in all areas of communication, especially public speaking. We will first take a more in-depth look at what critical thinking is—and isn’t.

Before we get too far into the specifics of what critical thinking is and how we can do it, it’s important to clear up a common misconception. Even though the phrase critical thinking uses the word “critical,” it is not a negative thing. Being critical is not the same thing as criticizing. When we criticize something, we point out the flaws and errors in it, exercising a negative value judgment on it. Our goal with criticizing is less about understanding than about negatively evaluating. It’s important to remember that critical thinking is not just criticizing. While the process may involve examining flaws and errors, it is much more.

Critical Thinking Defined

Just what is critical thinking then? To help us understand, let’s consider a common definition of critical thinking. The philosopher John Dewey, often considered the father of modern day critical thinking, defines critical thinking as:

“Active, persistent, careful consideration of a belief or supposed form of knowledge in light of the grounds that support it and the further conclusions to which it tends.” [1]

The first key component of Dewey’s definition is that critical thinking is active. Critical thinking must be done by choice. As we continue to delve deeper into the various facets of critical thinking, we will learn how to engage as critical thinkers.

Probably one of the most concise and easiest to understand definitions is that offered by Barry Beyer: “Critical thinking… means making reasoned judgments.” [2] In other words, we don’t just jump to a conclusion or a judgment. We rationalize and justify our conclusions. A second primary component of critical thinking, then, involves questioning. As critical thinkers, we need to question everything that confronts us. Equally important, we need to question ourselves and ask how our own biases or assumptions influence how we judge something.

In the following sections we will explore how to do critical thinking more in depth. As you read through this material, reflect back on Dewey’s and Beyer’s definitions of critical thinking.

- Dewey, J. (1933). Experience and education . New York: Macmillan, 1933. ↵

- Beyer, B. K. (1995) Critical thinking. Bloomington, IN: Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation. ↵

Fundamentals of Public Speaking Copyright © by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

46 Getting Started in Public Speaking

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student will be able to:

- Define public speaking, channel, feedback, noise, encode, decode, symbol, denotative, and connotative;

- Explain what distinguishes public speaking from other modes of communication;

- List the elements of the communication process;

- Explain the origins of anxiety in public speaking;

- Apply some strategies for dealing with personal anxiety about public speaking;

- Discuss why public speaking is part of the curriculum at this college and important in personal and professional life.

Getting Started in Public Speaking

To finish this first chapter, let’s close with some foundational principles about public speaking, which apply no matter the context, audience, topic, or purpose.

Timing is everything

We often hear this about acting or humor. In this case, it has to do with keeping within the time limits. As mentioned before, you can only know that you are within time limits by practicing and timing yourself; being within time limits also shows preparation and forethought. More importantly, being on time (or early) for the presentation and within time limits shows respect for your audience.

Public speaking requires muscle memory

If you have ever learned a new sport, especially in your teen or adult years, you know that you must consciously put your body through some training to get it used to the physical activity of the sport. An example is golf. A golf swing, unlike swinging a baseball bat, is not a natural movement and requires a great deal of practice, over and over, to get right. Pick up any golf magazine and there will be at least one article on “perfecting the swing.” In fact, when done incorrectly, the swing can cause severe back and knee problems over time.

Public speaking is a physical activity as well. You are standing and sometimes moving around; your voice, eye contact, face, and hands are involved. You will expend physical energy, and after the speech you may be tired. Even more, your audience’s understanding and acceptance of your message may depend somewhat on how energetic, controlled, and fluid your physical delivery. Your credibility as a speaker hinges to some extent on these matters. Consequently, learning public speaking means you must train your body to be comfortable and move in predictable and effective ways.

Public speaking involves a content and relationship dimension

You may have heard the old saying, “People don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care.” According to Watzlawick, Beavin, and Jackson (1967), all human communication has two elements going on at the same time: content and relationship. There are statements about ideas, facts, and information, and there are messages communicated about the relationship between the communication partners, past and present. These relationship message have to do with trust, respect, and credibility, and are conveyed through evidence, appeals, wording (and what the speaker does not say) as well as nonverbal communication.

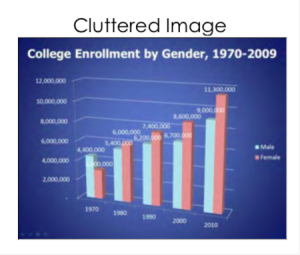

That said, public speaking is not a good way to provide a lot of facts and data to your audience. In fact, there are limits to how much information you can pile on your audience before listening is too difficult for them. However, public speaking is a good way to make the information meaningful for your audience. You can use a search engine with the term “Death by PowerPoint” and find lots of humorous, and too true, cartoons of audiences overwhelmed by charts, graphs, and slides full of text. In the case, less is more. This “less as more” principle will be re-emphasized throughout this textbook.

Emulation is the sincerest form of flattery

Learn from those who do public speaking well, but find what works best for you. Emulation is not imitation or copying someone; it is following a general model. Notice what other speakers do well in a speech and try to incorporate those strategies. An example is humor. Some of us excel at using humor, or some types of it. Some of us do not, or do not believe we do, no matter how hard we try. In that case, you may have to find other strengths to becoming an effective speaker.

Know your strengths and weaknesses

Reliable personality inventories, such as the Myers Briggs or the Gallup StrengthsQuest tests, can be helpful in knowing your strengths and weaknesses. One such area is whether you are an extravert or introvert. Introverts (about 40% of the population) get their psychological energy from being alone while extraverts tend to get it from being around others. This is a very basic distinction and there is more to the two categories, but you can see how an extravert may have an advantage with public speaking. However, the extravert may be tempted not to prepare and practice as much because he or she has so much fun in front of an audience, while the introvert may overprepare but still feel uncomfortable. Your public speaking abilities will benefit from increased self-awareness about such characteristics and your strengths. (For an online self-inventory about introversion and extraversion, go to http://www.quietrev.com/the-introvert-test/)

Remember the Power of Story

Stories and storytelling, in the form of anecdotes and narrative illustrations, are your most powerful tool as a public speaker. For better or worse, audiences are likely to remember anecdotes and narratives long after a speech’s statistics are forgotten.Your instructor may assign you to do a personal narrative speech, or require you to write an introduction or conclusion for one of your speeches that includes a story. This does not mean that other types of proof are unimportant and that you just want to tell stories in your speech, but human beings love stories and often will walk away from a speech moved by or remembering a powerful story or example more than anything.

This chapter has been designed to be informative but also serve as a bit of a pep talk. Many students face this course with trepidation, for various reasons. However, as studies have shown over the years, a certain amount of tension when preparing to speak in public can be good for motivation. A strong course in public speaking should be grounded in the communication research, the wisdom of those who have taught it over the last 2,000 years, and reflecting on your own experience.

John Dewey (1916), the twentieth century education scholar, is noted for saying, “Education does not come just from experience, but from reflecting on the experience.” As you finish this chapter and look toward your first presentation in class, be sure to give yourself time after the experience to reflect, whether by talking to another person, journaling, or sitting quietly and thinking, about how the experience can benefit the next speech encounter. Doing so will get you on the road to becoming more confident in this endeavor of public speaking.

Something to Think About

Investigate some other communication models on the Internet. What do they have in common? How are they different? Which ones seem to explain communication best to you?

Exploring Communication in the Real World Copyright © 2020 by Chris Miller is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Learning Objectives

- Describe the stages of the listening process.

- Discuss the four main types of listening.

- Compare and contrast the four main listening styles.

Listening is the learned process of receiving, interpreting, recalling, evaluating, and responding to verbal and nonverbal messages. We begin to engage with the listening process long before we engage in any recognizable verbal or nonverbal communication. It is only after listening for months as infants that we begin to consciously practice our own forms of expression. In this section we will learn more about each stage of the listening process, the main types of listening, and the main listening styles.

The Listening Process

Listening is a process and as such doesn’t have a defined start and finish. Like the communication process, listening has cognitive, behavioral, and relational elements and doesn’t unfold in a linear, step-by-step fashion. Models of processes are informative in that they help us visualize specific components, but keep in mind that they do not capture the speed, overlapping nature, or overall complexity of the actual process in action. The stages of the listening process are receiving, interpreting, recalling, evaluating, and responding .

Before we can engage other steps in the listening process, we must take in stimuli through our senses. In any given communication encounter, it is likely that we will return to the receiving stage many times as we process incoming feedback and new messages. This part of the listening process is more physiological than other parts, which include cognitive and relational elements. We primarily take in information needed for listening through auditory and visual channels. Although we don’t often think about visual cues as a part of listening, they influence how we interpret messages. For example, seeing a person’s face when we hear their voice allows us to take in nonverbal cues from facial expressions and eye contact. The fact that these visual cues are missing in e-mail, text, and phone interactions presents some difficulties for reading contextual clues into meaning received through only auditory channels.

The first stage of the listening process is receiving stimuli through auditory and visual channels.

Britt Reints – LISTEN – CC BY 2.0.