- Last edited on September 9, 2020

Homework in CBT

Table of contents, why do homework in cbt, how to deliver homework, strategies to increase confidence.

Homework assignments in Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) can help your patients educate themselves further, collect thoughts, and modify their thinking.

Homework is not something that you just assign randomly. You should make sure you:

- tailor the homework to the patient

- provide a rationale for why the patient needs to do the homework

- uncover any obstacles that might prevent homework from being done (i.e. - busy work schedule, significant neurovegetative symptoms)

Types of homework

Types of homework assignments.

You should also decide the frequency of the homework should be assigned: should it be daily, weekly?

If your patient does not do homework, that’s OK! Explore as a team, in a non-judgmental way, to explore why the homework was not done. Here are some ways to increase adherence to homework:

- Tailor the assignments to the individual

- Provide a rationale for how and why the assignment might help

- Determine the homework collaboratively

- Try to start the homework during the session. This creates some momentum to continue doing the homework

- Set up systems to remember to do the assignments (phone reminders, sticky notes

- It is better to start with easier homework assignments and err on the side of caution

- They should be 90-100% confident they will be able to do this assignment

- Covert rehearsal - running through a thought experiment on a situation

- Change the assignment - It is far better to substitute an easier homework assignment that patients are likely to do than to have them establish a habit of not doing what they had agreed to in session

- Intellectual/emotional role play - “I’ll be the intellectual part of you; you be the emotional part. You argue as hard as you can against me so I can see all the arguments you’re using not to read your coping cards and start studying. You start.”

Applications for the Beck Institute Certified Master Clinician program are open! Learn more .

- Impact of CBT

What is the Status of “Homework” in Cognitive Behavior Therapy, 50 Years On?

By Nikolaos Kazantzis, PhD

The comedian Jerry Seinfeld once asked:

“ What’s the deal with ‘homework?’ It’s not like you’re doing work on your home… ”

The great thing about that quote is that it conveys that the “H” word has some of the most unpleasant associations for clients in CBT. In July 2016, Dr. Judith S. Beck and Dr. Francine Broder wrote an important contribution to the Beck Institute blog giving good reason for a move away from the “H” word in practice.

When developing Cognitive Therapy, Dr. Aaron T. Beck was inspired by existing therapies, including behavior therapy, wherein the educative model to generate clinically meaningful change had been adopted. The inclusion of homework as a crucial feature of Cognitive Therapy made perfect sense 1 . Homework is a collaborative endeavor. It is also ideally empirical and can help to promote the reappraisal of key cognitions 2 .

Asking clients to engage with therapeutic tasks between sessions, in a form of action plan has been subject to more empirical study than any other process in CBT 3 . However, the evidence supporting homework is almost wholly derived from dismantling studies that contrast CBT with CBT without homework, or correlational studies of homework adherence and symptom reduction. Findings from our most recent meta-analysis suggest that homework quantity and quality have little difference in their relations with outcome 4 . As clinicians, we can take from this that we should use homework consistently and be especially encouraged when clients engage with tasks 5 .

However, if we try to seriously answer Jerry’s question above, we have to ask ourselves another important question – what are we actually really interested in with CBT homework?

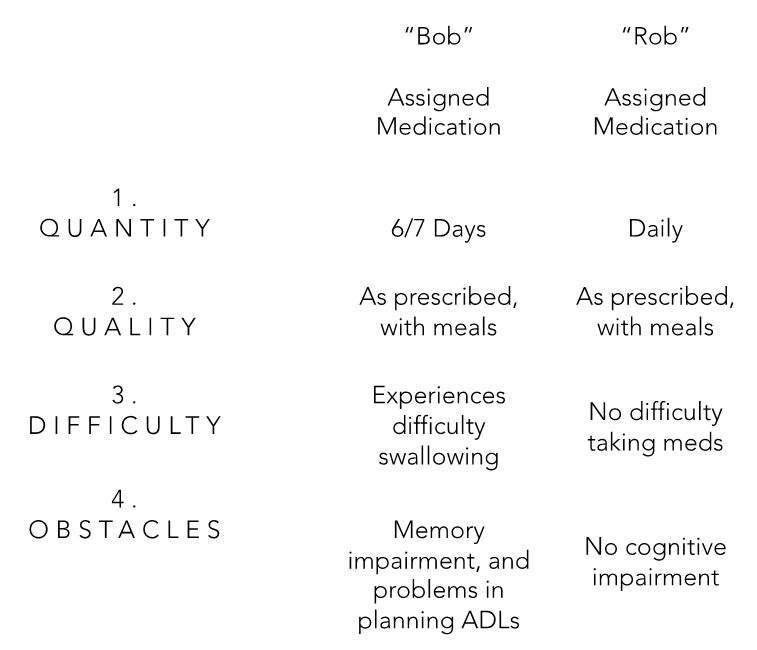

Current definitions of homework adherence have been derived from the literature on pharmacotherapy, and that might be the source of the problem. Take our two client examples below, Bob and Rob. Both have been prescribed a daily medication script, and if we look at the quantity of what was “done,” Rob looks more “adherent” than Bob.

However, when we take into account the cognitive impairment that Bob has, as well as his capacity to swallow medication following a head injury, then his 6/7 days’ worth of adherence is particularly noteworthy. Of course, in CBT, the content of homework varies on a weekly basis, and is tailored for the client in its design and plan. Therefore, the scope for subjective views of difficulty, and array of unique practical barriers is considerable. Thus, if we are genuinely interested in “engagement,” we need to take into account the inherent difficulties of the homework and practical obstacles to it for each individual client, at each session 6 .

Dr. Judith Beck’s earliest teachings emphasize the importance of the client’s subjective evaluation of homework. Those who are depressed are less likely to recognize their achievements, those with anxiety presentations often have negative predictions about its utility or their ability to carry it out, and many clients abandon the task when encountering obstacles. Those with pervasive interpersonal difficulties often have their core beliefs triggered in carrying out the action plan. When they do, they may experience intense negative emotion, viewing themselves and/or their therapist negatively. The working alliance may become strained. Dr. Beck has also advocated for use of the cognitive case conceptualization to understand clients’ patterns of engagement and anticipate problems of this nature 7-8 .

Fortunately, the research underpinning CBT homework is moving towards more clinically meaningful studies. Therapist skill in using homework has been shown to predict outcomes 9-10 , and recently a study found that greater consistency of homework with the therapy session resulted in more adherence. 11 Our Cognitive Behavior Therapy Research Lab (currently based at the Turner Institute for Brain and Mental Health at Monash University) is centrally focused on how clients’ adaptive beliefs about homework strengthen their sense of self-efficacy in engaging in homework tasks, despite the difficulties and obstacles they experience. Thus, for several reasons, we can be optimistic that the evidence for homework is an example of how a bridge between science and practice is being built on solid foundations.

A half century after the first practice guide for Cognitive Therapy was published (Beck et al, 1979), we can be curious in the personal meaning our clients attribute to the action plan. How do beliefs about coping and change affect engagement? Are there important maladaptive assumptions and compensatory strategies that might make it difficult for the client to engage? How does the task align with the client’s values? What might be the pros and cons to the client in choosing not to engage? It’s important to focus less on trying to achieve perfect – or even a close approximation of perfect – “adherence” and to focus more on facilitating engagement. An empathic understanding of challenges clients face completing the homework tasks will better equip us to design and plan future homework. Rather than a focus on “compliance,” let us inspire our clients to tolerate the discomfort and uncertainty in their homework. Let us also celebrate in their discovery of new ideas and perspectives that homework brings.

Nikolaos Kazantzis, PhD is Editor of “Using Homework Assignments in Cognitive Behavior Therapy” (2 nd edition), currently in preparation with Routledge publishers of New York.

- Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression . New York: Guilford Press.

- Kazantzis, N., Dattilio, F. M., & Dobson, K. A. (2017). The therapeutic relationship in cognitive behavioral therapy: A clinician’s guide. New York: Guilford.

- Kazantzis, N., Luong, H. K., Usatoff, A. S., Impala, T., Yew, R. Y., & Hofmann, S. G. (2018). The processes of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 42 (4), 349-357. doi: 10.1007/s10608-018-9920-y

- Kazantzis, N., Whittington, C. J., Zelencich, L., Norton, P. J., Kyrios, M., & Hofmann, S. G. (2016). Quantity and quality of homework compliance: A meta-analysis of relations with outcome in cognitive behavior therapy. Behavior Therapy, 47 , 755-772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2016.05.002

- Callan, J. A., Kazantzis, N., Park, S. Y., Moore, C., Thase, M. E., Emeremni, C. A., Minhajuddin, A., Kornblith, S., & Siegle, G. J. (2019). Effects of cognitive behavior therapy homework adherence on outcomes: Propensity score analysis. Behavior Therapy, 50 (2), 285-299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2018.05.010

- Holdsworth, E., Bowen, E., Brown, S., & Howat, D. (2014). Client engagement in psychotherapeutic treatment and associations with client characteristics, therapist characteristics, and treatment factors. Clinical Psychology Review, 34 (5), 428–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.06.004

- Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive therapy for challenging problems: What to do when the basics don’t work . New York: Guilford.

- Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford.

- Weck, F., Richtberg, S., Esch, S., Hofling, V., & Stangier, U. (2013). The relationship between therapist competence and homework compliance in maintenance cognitive therapy for recurrent depression: Secondary analysis of a randomized trial. Behavior Therapy, 44 (1), 162–172. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2012.09.004

- Conklin, L. R., Strunk, D. R., & Cooper, A. A. (2018). Therapist behaviors as predictors of immediate homework engagement in cognitive therapy for depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 42 (1), 16–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-017-9873-6

- Jensen, A., Fee, C., Miles, A. L., Beckner, V. L., Owen, D., & Persons, J. B. (in press). Congruence of patient takeaways and homework assignment content predicts homework compliance in psychotherapy. Behavior Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2019.07.005

Privacy Overview

Advertisement

Introduction to the Special Issue on Homework in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: New Clinical Psychological Science

- Published: 18 February 2021

- Volume 45 , pages 205–208, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Nikolaos Kazantzis ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9559-4160 1

3778 Accesses

6 Citations

Explore all metrics

This article introduces the Special Issue in Cognitive Therapy and Research that presents advances in clinical psychological science for homework in behavior and cognitive behavioral therapies (CBTs). Studies include sophisticated evaluations of homework adherence, moving beyond simplistic assessments of quantity and quality of completion to more complete assessments of engagement (i.e., perceived difficulty, obstacles, and helpfulness). Studies advance the clinical psychological science by examining therapist behavior as a predictor of homework adherence, by testing homework as a vehicle for specific treatment processes in behavior therapy (e.g., context engagement via exposure), and also by quantifying relational patterns within longitudinal data from mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. The Special Issue also includes two studies on mobile health delivery of CBT interventions and point to advances in gathering objective data on client engagement with homework.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Homework has been incorporated in behavior and cognitive behavioral therapies (CBT) as a primary means of facilitating generalization and maintenance of skills (Beck et al. 1979 ; Beck 2011 ; Kazantzis et al. 2005 ). Given that homework, in essence, is the extension of the in-session work to the client’s daily life through continuation of the technique from the session or some modification thereof, homework directly supports treatment processes in CBTs (Hofmann and Hayes 2018 ; Klepac et al. 2012 ; Mennin et al. 2013 ). However, more fundamental questions have been posed by researchers seeking to advance the science for this aspect of CBT process.

Acknowledging the limitations of low statistical power (see quantitative review in Kazantzis 2000 ), the typical study on homework has either sought to (a) examine causal effects using experimental methodology, by contrasting CBT with and without homework, or (b) examine correlations involving the quantity of homework completed. When aggregated by multiple research groups, across disorders, across clinical populations and types of homework, these studies provide robust evidence for both causal (Kazantzis et al. 2000 ) and correlational effects (Kazantzis et al. 2016 ; Mausbach et al. 2010 ). The effect of adding homework to therapy is medium and significant ( d = 0.53; 95% CI 0.35–0.72, p < 0.0001 in Kazantzis et al. 2010 ) and the linear association between homework compliance and outcome is small and significant ( r = 0.26; 95% CI 0.19−0.33 in Mausbach et al.). More recently, a focus has been placed on the assessment of quality of homework completed, in relation to outcome (Kazantzis et al. 2016 ). The articles in this Special Issue manage to achieve the impressive task of extending beyond these fundamental questions and draw upon advancements in clinical methods and technological advancements in psychotherapy delivery to examine more complex questions.

The effective facilitation of client engagement in homework is not straightforward; it is a process of CBT nested within a broader therapeutic relationship and demands a variety of therapist behaviors in order to skillfully design, plan, and then review homework. Further complexity can be acknowledged when we consider that the therapist is engaged in a moment-to-moment case conceptualization; drawing links between what the client is currently saying and what they have said in the past, taking into account the client’s current CBT skills (e.g., access to cognitions and personal responsibility for change), their unique beliefs and etiological factors that explain psychopathology (e.g., core beliefs, assumptions, rules, schema, behavioral and relational patterns), while fluidly adjusting generic (e.g., working alliance) and CBT specific elements (i.e., collaboration, empiricism, Socratic dialogue) of the therapeutic relationship based on that evolving conceptualization (Kazantzis et al. 2017 ; Lorenzo-Luaces et al. 2015 ). This process has the potential to activate the client’s negative core beliefs, and lead to a rupture in the working alliance (Okamoto and Kazantzis, in press). Despite the substantial role of the therapist, only a few studies have sought to consider the behavior the therapist as a predictor of engagement.

Studying Therapist Skill as a Predictor

Startup and Edmonds ( 1994 ) conducted an early study examining the behaviors of the therapist (i.e., occurrence of behavior) as a predictor of homework adherence, but were unable to demonstrate a clear link, possibly due to the measures available to identify presence and degree of therapist skill. In a subsequent study by Bryant et al. ( 1999 ), data gathered by trained independent observers using a modification of the Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale (Young and Beck 1980 ) showed an association between therapist skill in reviewing homework and adherence in CBT for depression, findings that were replicated in the context of anxiety (Weck et al. 2013 ). Therapist skill in assigning homework has also been associated with homework adherence in multiple studies (Conklin et al. 2017 ; Jungbluth and Shirk 2013 ; Ryum et al. 2010 ).

The articles in this Special Issue of Cognitive Therapy and Research reflect the latest scientific work on the role of therapist skill as a predictor of homework adherence. The paper by Yew et al. ( 2021 ) considered whether client appraisals of homework, and a broader concept of adherence, engagement (i.e., taking into account client perceptions of the difficulty and obstacles in attempting the homework) served as mediators of relations involving therapist skill/ competence. The paper by Haller and Watzke ( 2021 ) examined associations involving the frequency of therapist behaviors associated with homework adherence and depressive symptoms in telephone delivered CBT.

New Data on Homework-Outcome Relations

The paper by Wheaton and Chen ( 2021 ) focuses on the role of homework as a vehicle for exposure in treating obsessive compulsive disorder. Their paper provides a useful account of how homework facilitates a treatment process of context engagement and offers some useful recommendations for future research on the basis of their findings.

The paper by ter Avest et al. ( 2021 ) examines homework in the context of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and makes a novel contribution by examining client symptom profile in relation to homework adherence at follow-up assessment points.

Employing Advances in Technology to Advance Clinical Psychological Science for Homework

Early efforts to obtain objective data on client homework adherence were unsuccessful and hampered by the technology available at the time. For example, Hoelscher et al. ( 1984 ) attempted to obtain objective data on clients’ level of relaxation practice by including a timer in an audio cassette player, and because the device was an obviously modified piece of equipment participants were suspicious and this resulted in unreliability of resultant adherence data. Other studies have experienced similar technological challenges, such as in Neimeyer et al. ( 2008 ) where lightly glued pages of a book were used as the measure of adherence (i.e., once opened).

In 2021, technology provides an ethical and far less invasive means of attempting to obtain objective assessments of homework adherence (Aizenstros et al. in press). The paper by Kraepelien et al. ( 2021 ) provides an example of how homework adherence assessment can be enhanced, both in terms of the frequency and focus of assessment. Their study employed weekly adherence assessments and sought to examine client ratings of the helpfulness of the homework.

Two studies examined mobile health delivery of CBT. The paper by Bunnell et al. ( 2021 ) involved interviews with clients and trainers to examine barriers to the successful implementation of homework in youth mental health treatment as well as the potential for mobile solutions to overcome those barriers. The paper by Callan et al. ( 2021 ) outlines an initial development and testing of a mobile mental health smartphone application delivering CBT interventions for depression, a central relationship studied was the extent of app use and symptom reduction.

Finally, an in-depth discussion of the Special Issue’s contributions is provided by Dobson ( 2021 ). Findings from the papers presented from the issue along with opportunities for future research are tied together in this final compelling piece.

Concluding Comments

Homework has been extensively studied in the context of behavior and cognitive-behavior therapies over the past several decades. Theoretical and methodological advances in psychotherapy have occurred during this period and clarity regarding cognitive and behavioral determinants of homework adherence have emerged. As illustrated by papers in this Special Issue, opportunities exist to refine the assessment of homework adherence to include client appraisals in a more complete assessment of the concept of engagement in CBT.

The role of therapist skill, and the broader therapist–client interaction also provides a rich territory for future scientific enquiry. New data have come to light; studies in this Special Issue have examined specific portions of therapist skill in reviewing and assigning homework, and further work is needed to examine the complex interplay between specific skills in using homework, case conceptualization (given that task beliefs serve as determinants of engagement), and more global skills in facilitating a therapeutic relationship in behavior and CBTs. Although a comprehensive model of how therapist behavior, nested within a broader therapeutic relationship, is yet to be published and tested at the time of this writing, the papers in this Special Issue provide encouragement about the current advances in clinical psychological science.

Aizenstros, A., Bakker, D., Hofmann, S. G., Curtiss, J., & Kazantzis, N. (in press). Engagement with smartphone-delivered behavioral activation interventions: A study of the MoodMission smartphone application. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy.

Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression . New York: Guilford Press.

Google Scholar

Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive therapy for challenging problems: What to do when the basics don’t work . New York: Guilford.

Bryant, M. J., Simons, A. D., & Thase, M. E. (1999). Therapist skill and patient variables in homework compliance: Controlling an uncontrolled variable in cognitive therapy outcome research. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 23 (4), 381–399. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018703901116 .

Article Google Scholar

Bunnell, B. E., Nemeth, L. S., Lenert, L. A., Kazantzis, N., Deblinger, E., Higgins, K. A., & Ruggiero, K. J. (2021). Barriers associated with the implementation of homework in youth mental health treatment and potential mobile health solutions. Cognitive Therapy and Research . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-020-10090-8 .

Callan, J. A., Sigle, G. J., Day, A., Thase, M. E., Kazantzis, N., Devito Dabbs, A. D., et al. (2021). CBTMobileWork: Development and testing of a mobile mental health application using patient-centered design. Cognitive Therapy and Research, this issue.

Conklin, L. R., Strunk, D. R., & Cooper, A. A. (2017). Therapist behaviors as predictors of immediate homework engagement in cognitive therapy for depression. Cognitive Therapy & Research . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-017-9873-6 .

Dobson, K. S. (2021) Conclusions from the Cognitive Therapy & Research special issue on homework. Cognitive Therapy & Research, this issue.

Haller, E., & Watzke, B. (2021). The role of homework engagement, homework-related therapist behaviors, and their association with depressive symptoms in telephone-based CBT for depression. Cognitive Therapy & Research . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-020-10136-x .

Hoelscher, T. J., Lichstein, K. L., & Rosenthal, T. L. (1984). Objective vs subjective assessment of relaxation compliance among anxious individuals. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 22, 187–193.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Hofmann, S. G., & Hayes, S. C. (2018). The future of intervention science: Process-based therapy. Clinical Psychological Science, 7 (1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702618772296 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Jungbluth, N. J., & Shirk, S. R. (2013). Promoting homework adherence in cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 42 (4), 545–553. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2012.743105 .

Kazantzis, N. (2000). Power to detect homework effects in psychotherapy outcome research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 166–170. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.68.1.166 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Kazantzis, N., Dattilio, F. M., & Dobson, K. S. (2017). The therapeutic relationship in cognitive behavior therapy . New York: Guilford.

Kazantzis, N., Deane, F. P., & Ronan, K. R. (2000). Homework assignments in cognitive and behavioral therapy: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 7, 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.7.2.189 .

Kazantzis, N., Deane, F. P., Ronan, K. R., & L’Abate, L. (Eds.). (2005). Using homework assignments in cognitive behavioral therapy . New York: Routledge.

Kazantzis, N., Whittington, C. J., & Dattilio, F. M. (2010). Meta-analysis of homework effects in cognitive and behavioral therapy: A replication and extension. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 17, 144–156.

Kazantzis, N., Whittington, C. J., Zelencich, L., Norton, P. J., Kyrios, M., & Hofmann, S. G. (2016). Quantity and quality of homework compliance: A meta-analysis of relations with outcome in cognitive behavior therapy. Behavior Therapy, 47, 755–772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2016.05.002 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Klepac, R. K., Ronan, G. F., Andrasik, F., Arnold, K. D., Belar, C. D., Berry, S. L., et al. (2012). Guidelines for cognitive behavioral training within doctoral psychology programs in the United States: Report of the Inter-Organizational Task Force on Cognitive and Behavioral Psychology Doctoral Education. Behavior Therapy, 43 (4), 687–697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2012.05.002 .

Kraepelien, M., Blom, K., Jernelöv, S., & Kaldo, V. (2021). Weekly self-ratings of treatment involvement and their relation to symptom reduction in internet cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. Cognitive Therapy & Research . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-020-10151-y .

Lorenzo-Luaces, L., German, R. E., & DeRubeis, R. J. (2015). It’s complicated: The relation between cognitive change procedures, cognitive change, and symptom change in cognitive therapy for depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 41, 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.12.003 .

Mausbach, B. T., Moore, R., Roesch, S., Cardenas, V., & Patterson, T. L. (2010). The relationship between homework compliance and therapy outcomes: An updated meta-analysis. Cognitive Therapy & Research, 34, 429–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-010-9297-z .

Mennin, D. S., Ellard, K. K., Fresco, D. M., & Gross, J. J. (2013). United we stand: Emphasizing commonalities across cognitive-behavioral therapy. Behavior Therapy, 44, 234–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2013.02.004 .

Neimeyer, R. A., Kazantzis, N., Kassler, D. M., Baker, K. D., & Fletcher, R. (2008). Group cognitive behavior therapy for depression: Outcomes predicted by willingness to engage in homework, compliance with homework, and cognitive restructuring skill acquisition. Cognitive Behavior Therapy, 37, 199–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506070801981240 .

Okamoto, A., & Kazantzis, N. (in press). Alliance rupture repairs in cognitive therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Ryum, T., Stiles, T. C., Svartberg, M., & McCullough, L. (2010). The effects of therapist competence in assigning homework in cognitive therapy with cluster C personality disorders: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 17 (3), 283–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2009.10.005 .

Startup, M., & Edmonds, J. (1994). Compliance with homework assignments in cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for depression: Relation to outcome and methods of enhancement. Cognitive Therapy & Research, 18, 567–579.

ter Avest, M., Greven, C. U., Huijbers, M. J., Wilderjans, T. F., Speckens, A. E. M., & Spinhoven, P. (2021). Prospective associations between home practice and depressive symptoms in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for recurrent depression: A 15 months follow-up study. Cognitive Therapy & Research . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-020-10108-1 .

Weck, F., Richtberg, S., Esch, S., Höfling, V., & Stangier, U. (2013). The relationship between therapist competence and homework compliance in maintenance cognitive therapy for recurrent depression: Secondary analysis of a randomized trial. Behavior Therapy, 44 (1), 162–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2012.09.004 .

Wheaton, M. G., & Chen, S. C. (2021). Homework completion in treating obsessive-compulsive disorder with exposure and ritual prevention: A review of the empirical literature. Cognitive Therapy and Research . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-020-10125-0 .

Yew, R. Y., Dobson, K. S., Zypher, M., & Kazantzis, N. (2021). Mediators and moderators of homework-outcome relations in CBT for depression: A study of engagement, therapist skill, and client factors. Cognitive Therapy and Research . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-019-10059-2 .

Young, J. E., & Beck, A. T. (1980). Cognitive Therapy Scale: Rating manual. Unpublished manuscript. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Cognitive Behavior Therapy Research Unit, Institute for Social Neuroscience, Melbourne, VIC, 3079, Australia

Nikolaos Kazantzis

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nikolaos Kazantzis .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

Further to the signed Conflict-of-Interest Disclosure Forms submitted by the author on this manuscript, the author reported being the Australian delegate for the International Association of Cognitive Therapy, which has a strategic partnership with the Academy of Cognitive Therapy; being a consultant to the Australian Psychological Society Institute; serving on the advisory board, being a member of the faculty, and fees from the Beck Institute for Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Research; receiving compensation from Springer Nature; receiving royalties from Springer Nature, Guilford, and Routledge.

Informed Consent

No human subjects were involved in this article.

Research Involving Human and Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors. In addition, the attribution of authorship on this manuscript has also been carefully considered and is being made in a manner that is consistent with ethical research practice.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Kazantzis, N. Introduction to the Special Issue on Homework in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: New Clinical Psychological Science. Cogn Ther Res 45 , 205–208 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-021-10213-9

Download citation

Accepted : 30 January 2021

Published : 18 February 2021

Issue Date : April 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-021-10213-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Cognitive behavioral therapy

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Supporting Homework Compliance in Cognitive Behavioural Therapy: Essential Features of Mobile Apps

Affiliations.

- 1 Discipline of Psychiatry, Department of Medicine, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John's, NL, Canada.

- 2 Division of Youth Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, ON, Canada.

- 3 Centre for Mobile Computing in Mental Health, Department of Psychiatry, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, ON, Canada.

- 4 Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada.

- PMID: 28596145

- PMCID: PMC5481663

- DOI: 10.2196/mental.5283

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is one of the most effective psychotherapy modalities used to treat depression and anxiety disorders. Homework is an integral component of CBT, but homework compliance in CBT remains problematic in real-life practice. The popularization of the mobile phone with app capabilities (smartphone) presents a unique opportunity to enhance CBT homework compliance; however, there are no guidelines for designing mobile phone apps created for this purpose. Existing literature suggests 6 essential features of an optimal mobile app for maximizing CBT homework compliance: (1) therapy congruency, (2) fostering learning, (3) guiding therapy, (4) connection building, (5) emphasis on completion, and (6) population specificity. We expect that a well-designed mobile app incorporating these features should result in improved homework compliance and better outcomes for its users.

Keywords: cognitive behavioral therapy; homework compliance; mobile apps.

©Wei Tang, David Kreindler. Originally published in JMIR Mental Health (http://mental.jmir.org), 08.06.2017.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Therapy Homework?

Sanjana is a health writer and editor. Her work spans various health-related topics, including mental health, fitness, nutrition, and wellness.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/SanjanaGupta-d217a6bfa3094955b3361e021f77fcca.jpg)

Dr. Sabrina Romanoff, PsyD, is a licensed clinical psychologist and a professor at Yeshiva University’s clinical psychology doctoral program.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/SabrinaRomanoffPhoto2-7320d6c6ffcc48ba87e1bad8cae3f79b.jpg)

Astrakan Images / Getty Images

Types of Therapy That Involve Homework

If you’ve recently started going to therapy , you may find yourself being assigned therapy homework. You may wonder what exactly it entails and what purpose it serves. Therapy homework comprises tasks or assignments that your therapist asks you to complete between sessions, says Nicole Erkfitz , DSW, LCSW, a licensed clinical social worker and executive director at AMFM Healthcare, Virginia.

Homework can be given in any form of therapy, and it may come as a worksheet, a task to complete, or a thought/piece of knowledge you are requested to keep with you throughout the week, Dr. Erkfitz explains.

This article explores the role of homework in certain forms of therapy, the benefits therapy homework can offer, and some tips to help you comply with your homework assignments.

Therapy homework can be assigned as part of any type of therapy. However, some therapists and forms of therapy may utilize it more than others.

For instance, a 2019-study notes that therapy homework is an integral part of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) . According to Dr. Erkfitz, therapy homework is built into the protocol and framework of CBT, as well as dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) , which is a sub-type of CBT.

Therefore, if you’re seeing a therapist who practices CBT or DBT, chances are you’ll regularly have homework to do.

On the other hand, an example of a type of therapy that doesn’t generally involve homework is eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy. EMDR is a type of therapy that generally relies on the relationship between the therapist and client during sessions and is a modality that specifically doesn’t rely on homework, says Dr. Erkfitz.

However, she explains that if the client is feeling rejuvenated and well after their processing session, for instance, their therapist may ask them to write down a list of times that their positive cognition came up for them over the next week.

"Regardless of the type of therapy, the best kind of homework is when you don’t even realize you were assigned homework," says Erkfitz.

Benefits of Therapy Homework

Below, Dr. Erkfitz explains the benefits of therapy homework.

It Helps Your Therapist Review Your Progress

The most important part of therapy homework is the follow-up discussion at the next session. The time you spend reviewing with your therapist how the past week went, if you completed your homework, or if you didn’t and why, gives your therapist valuable feedback on your progress and insight on how they can better support you.

It Gives Your Therapist More Insight

Therapy can be tricky because by the time you are committed to showing up and putting in the work, you are already bringing a better and stronger version of yourself than what you have been experiencing in your day-to-day life that led you to seek therapy.

Homework gives your therapist an inside look into your day-to-day life, which can sometimes be hard to recap in a session. Certain homework assignments keep you thinking throughout the week about what you want to share during your sessions, giving your therapist historical data to review and address.

It Helps Empower You

The sense of empowerment you can gain from utilizing your new skills, setting new boundaries , and redirecting your own cognitive distortions is something a therapist can’t give you in the therapy session. This is something you give yourself. Therapy homework is how you come to the realization that you got this and that you can do it.

"The main benefit of therapy homework is that it builds your skills as well as the understanding that you can do this on your own," says Erkfitz.

Tips for Your Therapy Homework

Below, Dr. Erkfitz shares some tips that can help with therapy homework:

- Set aside time for your homework: Create a designated time to complete your therapy homework. The aim of therapy homework is to keep you thinking and working on your goals between sessions. Use your designated time as a sacred space to invest in yourself and pour your thoughts and emotions into your homework, just as you would in a therapy session .

- Be honest: As therapists, we are not looking for you to write down what you think we want to read or what you think you should write down. It’s important to be honest with us, and yourself, about what you are truly feeling and thinking.

- Practice your skills: Completing the worksheet or log are important, but you also have to be willing to put your skills and learnings into practice. Allow yourself to be vulnerable and open to trying new things so that you can report back to your therapist about whether what you’re trying is working for you or not.

- Remember that it’s intended to help you: Therapy homework helps you maximize the benefits of therapy and get the most value out of the process. A 2013-study notes that better homework compliance is linked to better treatment outcomes.

- Talk to your therapist if you’re struggling: Therapy homework shouldn’t feel like work. If you find that you’re doing homework as a monotonous task, talk to your therapist and let them know that your heart isn’t in it and that you’re not finding it beneficial. They can explain the importance of the tasks to you, tailor your assignments to your preferences, or change their course of treatment if need be.

"When the therapy homework starts 'hitting home' for you, that’s when you know you’re on the right track and doing the work you need to be doing," says Erkfitz.

A Word From Verywell

Similar to how school involves classwork and homework, therapy can also involve in-person sessions and homework assignments.

If your therapist has assigned you homework, try to make time to do it. Completing it honestly can help you and your therapist gain insights into your emotional processes and overall progress. Most importantly, it can help you develop coping skills and practice them, which can boost your confidence, empower you, and make your therapeutic process more effective.

Get Help Now

We've tried, tested, and written unbiased reviews of the best online therapy programs including Talkspace, BetterHelp, and ReGain. Find out which option is the best for you.

Conklin LR, Strunk DR, Cooper AA. Therapist behaviors as predictors of immediate homework engagement in cognitive therapy for depression . Cognit Ther Res . 2018;42(1):16-23. doi:10.1007/s10608-017-9873-6

Lebeau RT, Davies CD, Culver NC, Craske MG. Homework compliance counts in cognitive-behavioral therapy . Cogn Behav Ther . 2013;42(3):171-179. doi:10.1080/16506073.2013.763286

By Sanjana Gupta Sanjana is a health writer and editor. Her work spans various health-related topics, including mental health, fitness, nutrition, and wellness.

CBT Techniques: 25 Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Worksheets

It’s an extremely common type of talk therapy practiced around the world.

If you’ve ever interacted with a mental health therapist, a counselor, or a psychiatry clinician in a professional setting, it’s likely you’ve participated in CBT.

If you’ve ever heard friends or loved ones talk about how a mental health professional helped them identify unhelpful thoughts and patterns and behavior and alter them to more effectively work towards their goals, you’ve heard about the impacts of CBT.

CBT is one of the most frequently used tools in the psychologist’s toolbox. Though it’s based on simple principles, it can have wildly positive outcomes when put into practice.

In this article, we’ll explore what CBT is, how it works, and how you can apply its principles to improve your own life or the lives of your clients.

Before you read on, we thought you might like to download our three Positive CBT Exercises for free . These science-based exercises will provide you with a comprehensive insight into Positive CBT and will give you the tools to apply it in your therapy or coaching.

This Article Contains:

What is cbt, cognitive distortions, 9 essential cbt techniques and tools.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Worksheets (PDFs) To Print and Use

Some More CBT Interventions and Exercises

A cbt manual and workbook for your own practice and for your client, 5 final cognitive behavioral activities, a take-home message.

“This simple idea is that our unique patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving are significant factors in our experiences, both good and bad. Since these patterns have such a significant impact on our experiences, it follows that altering these patterns can change our experiences” (Martin, 2016).

Cognitive-behavioral therapy aims to change our thought patterns, our conscious and unconscious beliefs, our attitudes, and, ultimately, our behavior, in order to help us face difficulties and achieve our goals.

Psychiatrist Aaron Beck was the first to practice cognitive behavioral therapy. Like most mental health professionals at the time, Beck was a psychoanalysis practitioner.

While practicing psychoanalysis, Beck noticed the prevalence of internal dialogue in his clients and realized how strong the link between thoughts and feelings can be. He altered the therapy he practiced in order to help his clients identify, understand, and deal with the automatic, emotion-filled thoughts that regularly arose in his clients.

Beck found that a combination of cognitive therapy and behavioral techniques produced the best results for his clients. In describing and honing this new therapy, Beck laid the foundations of the most popular and influential form of therapy of the last 50 years.

This form of therapy is not designed for lifelong participation and aims to help clients meet their goals in the near future. Most CBT treatment regimens last from five to ten months, with clients participating in one 50- to 60-minute session per week.

CBT is a hands-on approach that requires both the therapist and the client to be invested in the process and willing to actively participate. The therapist and client work together as a team to identify the problems the client is facing, come up with strategies for addressing them, and creating positive solutions (Martin, 2016).

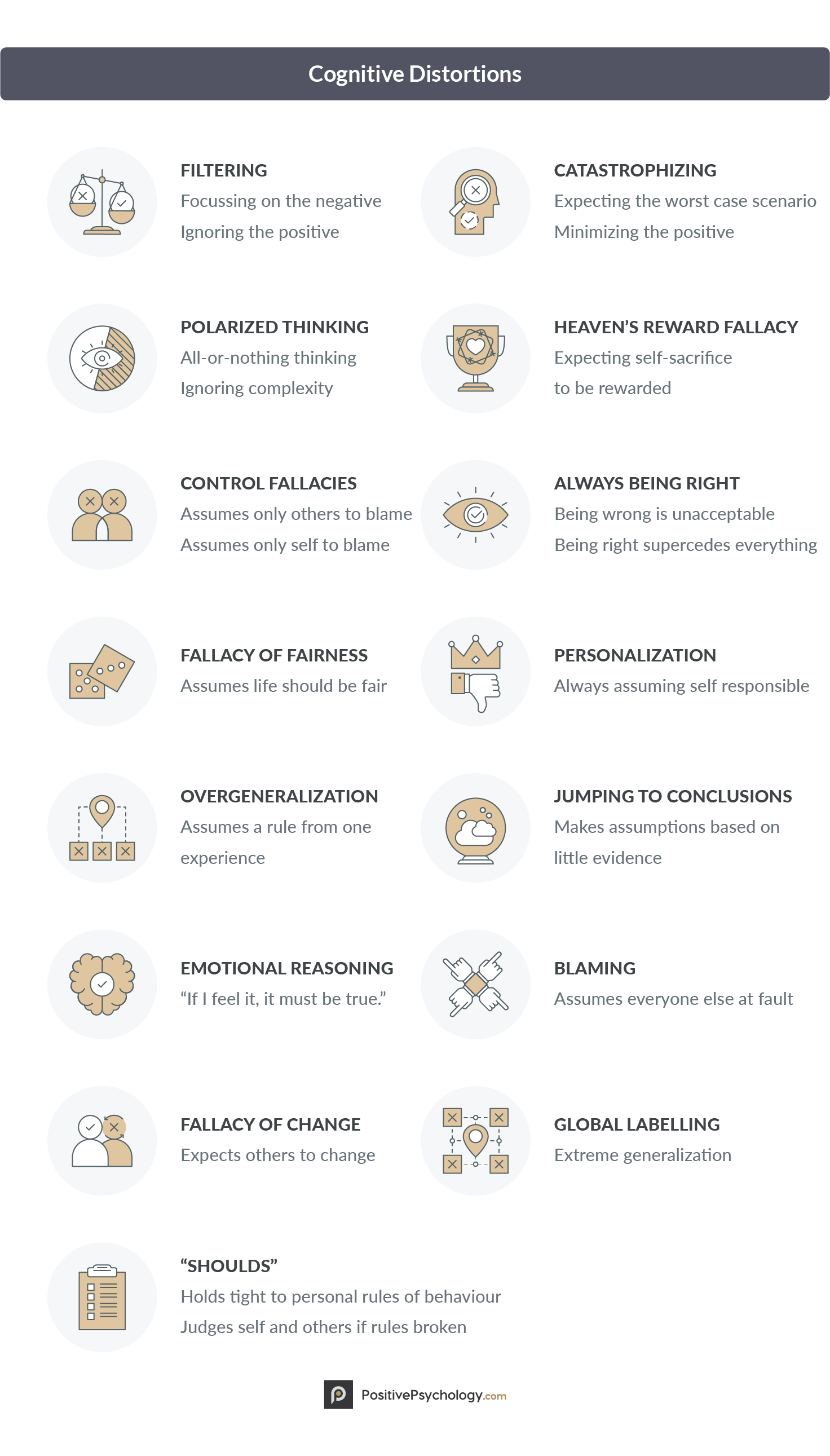

Many of the most popular and effective cognitive-behavioral therapy techniques are applied to what psychologists call “ cognitive distortions ,” inaccurate thoughts that reinforce negative thought patterns or emotions (Grohol, 2016).

There are 15 main cognitive distortions that can plague even the most balanced thinkers.

1. Filtering

Filtering refers to the way a person can ignore all of the positive and good things in life to focus solely on the negative. It’s the trap of dwelling on a single negative aspect of a situation, even when surrounded by an abundance of good things.

2. Polarized thinking / Black-and-white thinking

This cognitive distortion is all-or-nothing thinking, with no room for complexity or nuance—everything’s either black or white, never shades of gray.

If you don’t perform perfectly in some area, then you may see yourself as a total failure instead of simply recognizing that you may be unskilled in one area.

3. Overgeneralization

Overgeneralization is taking a single incident or point in time and using it as the sole piece of evidence for a broad conclusion.

For example, someone who overgeneralizes could bomb an important job interview and instead of brushing it off as one bad experience and trying again, they conclude that they are terrible at interviewing and will never get a job offer.

4. Jumping to conclusions

Similar to overgeneralization, this distortion involves faulty reasoning in how one makes conclusions. Unlike overgeneralizing one incident, jumping to conclusions refers to the tendency to be sure of something without any evidence at all.

For example, we might be convinced that someone dislikes us without having any real evidence, or we might believe that our fears will come true before we have a chance to really find out.

5. Catastrophizing / Magnifying or Minimizing

This distortion involves expecting that the worst will happen or has happened, based on an incident that is nowhere near as catastrophic as it is made out to be. For example, you may make a small mistake at work and be convinced that it will ruin the project you are working on, that your boss will be furious, and that you’ll lose your job.

Alternatively, one might minimize the importance of positive things, such as an accomplishment at work or a desirable personal characteristic.

6. Personalization

This is a distortion where an individual believes that everything they do has an impact on external events or other people, no matter how irrational that may be. A person with this distortion will feel that he or she has an exaggerated role in the bad things that happen around them.

For instance, a person may believe that arriving a few minutes late to a meeting led to it being derailed and that everything would have been fine if they were on time.

7. Control fallacies

This distortion involves feeling like everything that happens to you is either a result of purely external forces or entirely due to your own actions. Sometimes what happens to us is due to forces we can’t control, and sometimes what it’s due to our own actions, but the distortion is assuming that it is always one or the other.

We might assume that difficult coworkers are to blame for our own less-than-stellar work, or alternatively assume that every mistake another person makes is because of something we did.

8. Fallacy of fairness

We are often concerned about fairness, but this concern can be taken to extremes. As we all know, life is not always fair. The person who goes through life looking for fairness in all their experiences will end up resentful and unhappy.

Sometimes things will go our way, and sometimes they will not, regardless of how fair it may seem.

When things don’t go our way, there are many ways we can explain or assign responsibility for the outcome. One method of assigning responsibility is blaming others for what goes wrong.

Sometimes we may blame others for making us feel or act a certain way, but this is a cognitive distortion. Only you are responsible for the way you feel or act.

10. “Shoulds”

“Shoulds” refer to the implicit or explicit rules we have about how we and others should behave. When others break our rules, we are upset. When we break our own rules, we feel guilty. For example, we may have an unofficial rule that customer service representatives should always be accommodating to the customer.

When we interact with a customer service representative that is not immediately accommodating, we might get angry. If we have an implicit rule that we are irresponsible if we spend money on unnecessary things, we may feel exceedingly guilty when we spend even a small amount of money on something we don’t need.

11. Emotional reasoning

This distortion involves thinking that if we feel a certain way, it must be true. For example, if we feel unattractive or uninteresting in the current moment, we think we are unattractive or uninteresting. This cognitive distortion boils down to:

“I feel it, therefore it must be true.”

Clearly, our emotions are not always indicative of the objective truth, but it can be difficult to look past how we feel.

12. Fallacy of change

The fallacy of change lies in expecting other people to change as it suits us. This ties into the feeling that our happiness depends on other people, and their unwillingness or inability to change, even if we demand it, keeps us from being happy.

This is a damaging way to think because no one is responsible for our own happiness except ourselves.

13. Global labeling / mislabeling

This cognitive distortion is an extreme form of generalizing, in which we generalize one or two instances or qualities into a global judgment. For example, if we fail at a specific task, we may conclude that we are a total failure in not only that area but all areas.

Alternatively, when a stranger says something a bit rude, we may conclude that he or she is an unfriendly person in general. Mislabeling is specific to using exaggerated and emotionally loaded language, such as saying a woman has abandoned her children when she leaves her children with a babysitter to enjoy a night out.

14. Always being right

While we all enjoy being right, this distortion makes us think we must be right, that being wrong is unacceptable.

We may believe that being right is more important than the feelings of others, being able to admit when we’ve made a mistake or being fair and objective.

15. Heaven’s Reward Fallacy

This distortion involves expecting that any sacrifice or self-denial will pay off. We may consider this karma, and expect that karma will always immediately reward us for our good deeds. This results in feelings of bitterness when we do not receive our reward (Grohol, 2016).

Many tools and techniques found in cognitive behavioral therapy are intended to address or reverse these cognitive distortions.

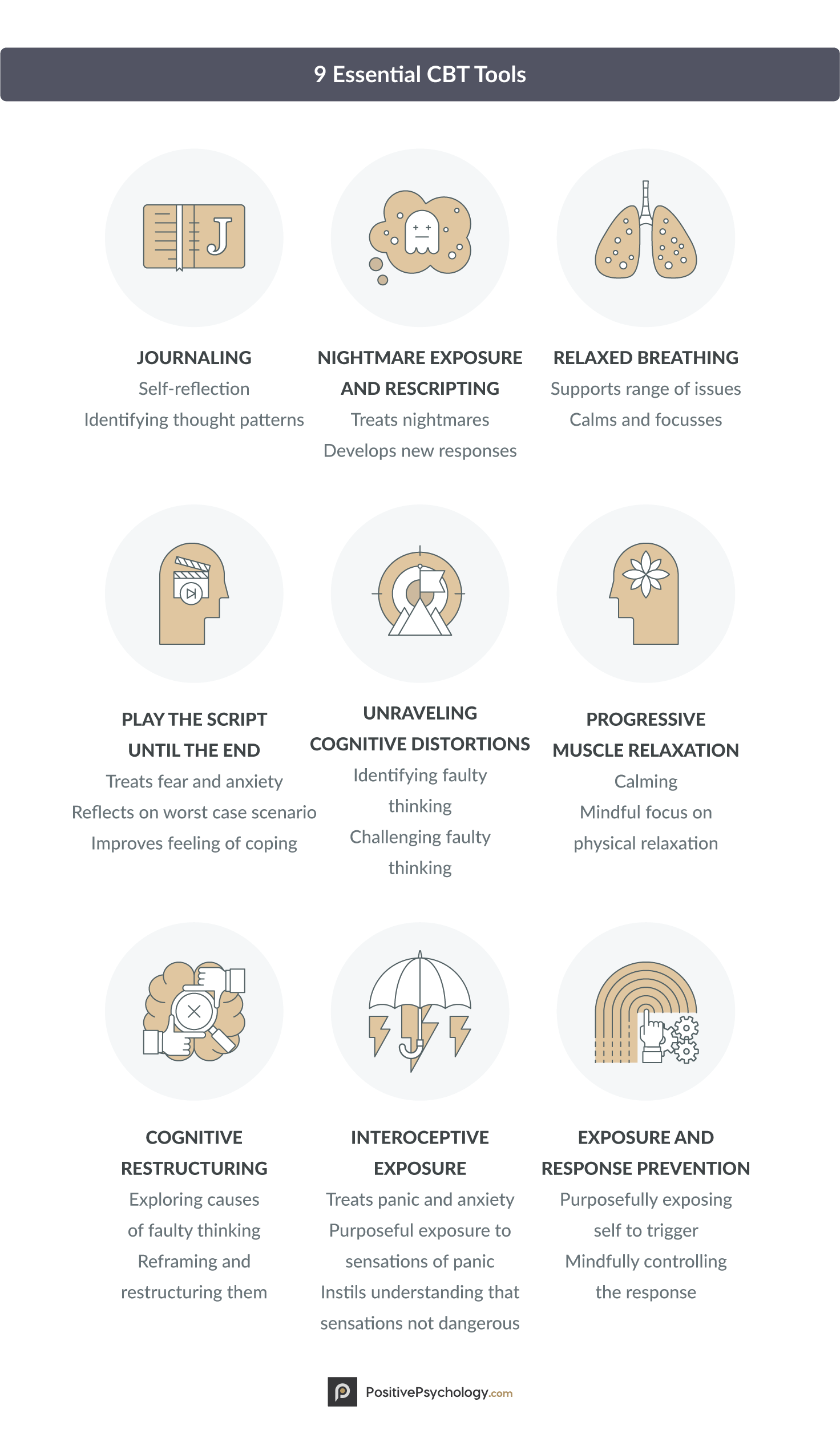

There are many tools and techniques used in cognitive behavioral therapy, many of which can be used in both a therapy context and in everyday life. The nine techniques and tools listed below are some of the most common and effective CBT practices.

1. Journaling

This technique is a way to gather about one’s moods and thoughts. A CBT journal can include the time of the mood or thought, the source of it, the extent or intensity, and how we reacted, among other factors.

This technique can help us to identify our thought patterns and emotional tendencies, describe them, and change, adapt, or cope with them (Utley & Garza, 2011).

Follow the link to find out more about using a thought diary for journaling.

2. Unraveling cognitive distortions

This is a primary goal of CBT and can be practiced with or without the help of a therapist. In order to unravel cognitive distortions, you must first become aware of the distortions from which you commonly suffer (Hamamci, 2002).

Part of this involves identifying and challenging harmful automatic thoughts, which frequently fall into one of the 15 categories listed earlier.

3. Cognitive restructuring

Once you identify the distortions you hold, you can begin to explore how those distortions took root and why you came to believe them. When you discover a belief that is destructive or harmful, you can begin to challenge it (Larsson, Hooper, Osborne, Bennett, & McHugh, 2015).

For example, if you believe that you must have a high-paying job to be a respectable person, but you’re then laid off from your high-paying job, you will begin to feel bad about yourself.

Instead of accepting this faulty belief that leads you to think negative thoughts about yourself, with cognitive restructuring you could take an opportunity to think about what really makes a person “respectable,” a belief you may not have explicitly considered before.

4. Exposure and response prevention

This technique is specifically effective for those who suffer from obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD; Abramowitz, 1996). You can practice this technique by exposing yourself to whatever it is that normally elicits a compulsive behavior, but doing your best to refrain from the behavior.

You can combine journaling with this technique, or use journaling to understand how this technique makes you feel.

5. Interoceptive exposure

Interoceptive Exposure is intended to treat panic and anxiety. It involves exposure to feared bodily sensations in order to elicit the response (Arntz, 2002). Doing so activates any unhelpful beliefs associated with the sensations, maintains the sensations without distraction or avoidance, and allows new learning about the sensations to take place.

It is intended to help the sufferer see that symptoms of panic are not dangerous, although they may be uncomfortable.

6. Nightmare exposure and rescripting

Nightmare exposure and rescripting are intended specifically for those suffering from nightmares. This technique is similar to interoceptive exposure, in that the nightmare is elicited, which brings up the relevant emotion (Pruiksma, Cranston, Rhudy, Micol, & Davis, 2018).

Once the emotion has arisen, the client and therapist work together to identify the desired emotion and develop a new image to accompany the desired emotion.

7. Play the script until the end

This technique is especially useful for those suffering from fear and anxiety. In this technique, the individual who is vulnerable to crippling fear or anxiety conducts a sort of thought experiment in which they imagine the outcome of the worst-case scenario.

Letting this scenario play out can help the individual to recognize that even if everything he or she fears comes to pass, the outcome will still be manageable (Chankapa, 2018).

8. Progressive muscle relaxation

This is a familiar technique to those who practice mindfulness. Similar to the body scan, progressive muscle relaxation instructs you to relax one muscle group at a time until your whole body is in a state of relaxation (McCallie, Blum, & Hood, 2006).

You can use audio guidance, a YouTube video, or simply your own mind to practice this technique, and it can be especially helpful for calming nerves and soothing a busy and unfocused mind.

9. Relaxed breathing

This is another technique that will be familiar to practitioners of mindfulness . There are many ways to relax and bring regularity to your breath, including guided and unguided imagery, audio recordings, YouTube videos, and scripts. Bringing regularity and calm to your breath will allow you to approach your problems from a place of balance, facilitating more effective and rational decisions (Megan, 2016).

These techniques can help those suffering from a range of mental illnesses and afflictions, including anxiety, depression, OCD, and panic disorder, and they can be practiced with or without the guidance of a therapist. To try some of these techniques without the help of a therapist, see the next section for worksheets and handouts to assist with your practice.

How does cognitive behavioral therapy work – Psych Hub

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Worksheets (PDFs) To Print and Use

1. Coping styles worksheet

This PDF Coping Styles Formulation Worksheet instructs you or your client to first list any current perceived problems or difficulties – “The Problem”. You or your client will work backward to list risk factors above (i.e., why you are more likely to experience these problems than someone else) and triggers or events (i.e., the stimulus or source of these problems).

Once you have defined the problems and understand why you are struggling with them, you then list coping strategies. These are not solutions to your problems, but ways to deal with the effects of those problems that can have a temporary impact. Next, you list the effectiveness of the coping strategies, such as how they make you feel in the short- and long-term, and the advantages and disadvantages of each strategy.

Finally, you move on to listing alternative actions. If your coping strategies are not totally effective against the problems and difficulties that are happening, you are instructed to list other strategies that may work better.

This worksheet gets you (or your client) thinking about what you are doing now and whether it is the best way forward.

2. ABC functional analysis

One popular technique in CBT is ABC functional analysis . Functional analysis helps you (or the client) learn about yourself, specifically, what leads to specific behaviors and what consequences result from those behaviors.

In the middle of the worksheet is a box labeled “Behaviors.” In this box, you write down any potentially problematic behaviors you want to analyze.

On the left side of the worksheet is a box labeled “Antecedents,” in which you or the client write down the factors that preceded a particular behavior. These are factors that led up to the behavior under consideration, either directly or indirectly.

On the right side is the final box, labeled “Consequences.” This is where you write down what happened as a result of the behavior under consideration. “Consequences” may sound inherently negative, but that’s not necessarily the case; some positive consequences can arise from many types of behaviors, even if the same behavior also leads to negative consequences.

This ABC Functional Analysis Worksheet can help you or your client to find out whether particular behaviors are adaptive and helpful in striving toward your goals, or destructive and self-defeating.

3. Case formulation worksheet

In CBT, there are 4 “P’s” in Case Formulation:

- Predisposing factors;

- Precipitating factors;

- Perpetuating factors; and

- Protective factors

They help us understand what might be leading a perceived problem to arise, and what might prevent them from being tackled effectively.

In this worksheet, a therapist will work with their client through 4 steps.

First, they identify predisposing factors, which are those external or internal and can add to the likelihood of someone developing a perceived problem (“The Problem”). Examples might include genetics, life events, or their temperament.

Together, they collaborate to identify precipitating factors, which provide insight into precise events or triggers that lead to “The Problem” presenting itself. Then they consider perpetuating factors, to discover what reinforcers may be maintaining the current problem.

Last, they identify protective factors, to understand the client’s strengths, social supports, and adaptive behavioral patterns.

Download 3 Free Positive CBT Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients with tools to find new pathways to reduce suffering and more effectively cope with life stressors.

Download 3 Free Positive CBT Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

4. Extended case formulation worksheet

This worksheet builds on the last. It helps you or your client address the “Four P Factors” described just above—predisposing, precipitating, perpetuating, and protective factors. This formulation process can help you or your client connect the dots between core beliefs, thought patterns, and present behavior.

This worksheet presents six boxes on the left of the page (Part A), which should be completed before moving on to the right-hand side of the worksheet (Part B).

- The first box is labeled “The Problem,” and corresponds with the perceived difficulty that your client is experiencing. In this box, you are instructed to write down the events or stimuli that are linked to a certain behavior.

- The next box is labeled “Early Experiences” and corresponds to the predisposing factor. This is where you list the experiences that you had early in life that may have contributed to the behavior.

- The third box is “Core Beliefs,” which is also related to the predisposing factor. This is where you write down some relevant core beliefs you have regarding this behavior. These are beliefs that may not be explicit, but that you believe deep down, such as “I’m bad” or “I’m not good enough.”

- The fourth box is “Conditional assumptions/rules/attitudes,” which is where you list the rules that you adhere to, whether consciously or subconsciously. These implicit or explicit rules can perpetuate the behavior, even if it is not helpful or adaptive. Rules are if-then statements that provide a judgment based on a set of circumstances. For instance, you may have the rule “If I do not do something perfectly, I’m a complete failure.”

- The fifth box is labeled “Maladaptive Coping Strategies” This is where you write down how well these rules are working for you (or not). Are they helping you to be the best you can be? Are they helping you to effectively strive towards your goals?

- Finally, the last box us titled “Positives.” This is where you list the factors that can help you deal with the problematic behavior or thought, and perhaps help you break the perpetuating cycle. These can be things that help you cope once the thought or behavior arises or things that can disrupt the pattern once it is in motion.

On the right, there is a flow chart that you can fill out based on how these behaviors and feelings are perpetuated. You are instructed to think of a situation that produces a negative automatic thought and record the emotion and behavior that this thought provokes, as well as the bodily sensations that can result. Filling out this flow chart can help you see what drives your behavior or thought and what results from it.

Download our PDF Extended Case Formulation Worksheet .

5. Dysfunctional thought record

This worksheet is especially helpful for people who struggle with negative thoughts and need to figure out when and why those thoughts are most likely to pop up. Learning more about what provokes certain automatic thoughts makes them easier to address and reverse.

The worksheet is divided into seven columns:

- On the far left, there is space to write down the date and time a dysfunctional thought arose.

- The second column is where the situation is listed. The user is instructed to describe the event that led up to the dysfunctional thought in detail.

- The third column is for the automatic thought. This is where the dysfunctional automatic thought is recorded, along with a rating of belief in the thought on a scale from 0% to 100%.

- The next column is where the emotion or emotions elicited by this thought are listed, also with a rating of intensity on a scale from 0% to 100%.

- Use this fifth column to note the dysfunctional thought that will be addressed. Example maladaptive thoughts include distortions such as over-inflating the negative while dismissing the positive of a situation, or overgeneralizing.

- The second-to-last column is for the user to write down alternative thoughts that are more positive and functional to replace the negative one.

- Finally, the last column is for the user to write down the outcome of this exercise. Were you able to confront the dysfunctional thought? Did you write down a convincing alternative thought? Did your belief in the thought and/or the intensity of your emotion(s) decrease?

Download this Dysfunctional Thought Record as a PDF.

6. Fact-checking

One of my favorite CBT tools is this Fact Checking Thoughts Worksheet because it can be extremely helpful in recognizing that your thoughts are not necessarily true.

At the top of this worksheet is an important lesson:

Thoughts are not facts.

Of course, it can be hard to accept this, especially when we are in the throes of a dysfunctional thought or intense emotion. Filling out this worksheet can help you come to this realization.

The worksheet includes 16 statements that the user must decide are either fact or opinion. These statements include:

- I’m a bad person.

- I failed the test.

- I’m selfish.

- I didn’t lend my friend money when they asked.

This is not a trick—there is a right answer for each of these statements. (In case you’re wondering, the correct answers for the statements above are as follows: opinion, fact, opinion, fact.)

This simple exercise can help the user to see that while we have lots of emotionally charged thoughts, they are not all objective truths. Recognizing the difference between fact and opinion can assist us in challenging the dysfunctional or harmful opinions we have about ourselves and others.

7. Cognitive restructuring

This worksheet employs the use of Socratic questioning, a technique that can help the user to challenge irrational or illogical thoughts.

The first page of the worksheet has a thought bubble for “What I’m Thinking”. You or your client can use this space to write down a specific thought, usually, one you suspect is destructive or irrational.

Next, you write down the facts supporting and contradicting this thought as a reality. What facts about this thought being accurate? What facts call it into question? Once you have identified the evidence, you can use the last box to make a judgment on this thought, specifically whether it is based on evidence or simply your opinion.

The next page is a mind map of Socratic Questions which can be used to further challenge the thought. You may wish to re-write “What I’m Thinking” in the center so it is easier to challenge the thought against these questions.

- One question asks whether this thought is truly a black-and-white situation, or whether reality leaves room for shades of gray. This is where you think about (and write down) whether you are using all-or-nothing thinking, for example, or making things unreasonably simple when they are complex.

- Another asks whether you could be misinterpreting the evidence or making any unverified assumptions. As with all the other bubbles, writing it down will make this exercise more effective.

- A third bubble instructs you to think about whether other people might have different interpretations of the same situation, and what those interpretations might be.

- Next, ask yourself whether you are looking at all the relevant evidence or just the evidence that backs up the belief you already hold. Try to be as objective as possible.

- It also helps to ask yourself whether your thought may an over-inflation of a truth. Some negative thoughts are based in truth but extend past their logical boundaries.

- You’re also instructed to consider whether you are entertaining this negative thought out of habit or because the facts truly support it.

- Then, think about how this thought came to you. Was it passed on from someone else? If so, is that person a reliable source of truth?

- Finally, you complete the worksheet by identifying how likely the scenario your thought brings up actually is, and whether it is the worst-case scenario.

These Socratic questions encourage a deep dive into the thoughts that plague you and offer opportunities to analyze and evaluate those thoughts. If you are having thoughts that do not come from a place of truth, this Cognitive Restructuring Worksheet can be an excellent tool for identifying and defusing them.

How is positive cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) different from traditional CBT?

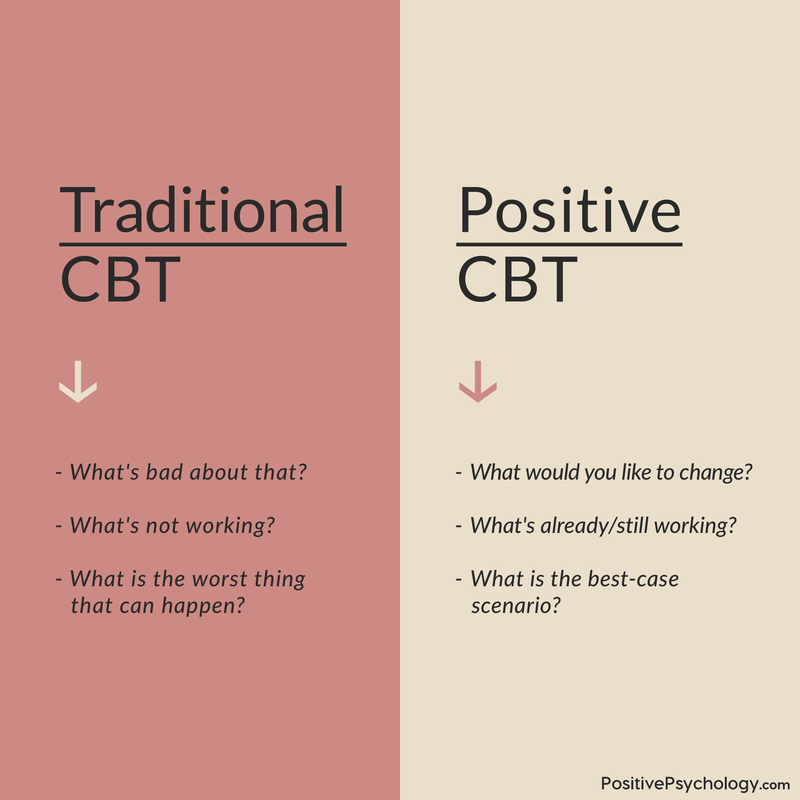

Although both forms of CBT have the same goal of bringing about positive changes in a client’s life, the pathways used in traditional and positive CBT to actualize this goal differ considerably. Traditional CBT, as initially formulated by Beck (1967), focuses primarily on the following:

- Analyzing problems

- Lessening what causes suffering

- Working on clients’ weaknesses

- Getting away from problems

Instead, positive CBT, as formulated by Bannink (2012), focuses mainly on the following:

- Finding solutions

- Enhancing what causes flourishing

- Working with client’s strengths

- Getting closer to the preferred future

In other words, Positive CBT shifts the focus on what’s right with the person (rather than what’s wrong with them) and on what’s working (rather than what’s not working) to foster a more optimistic process that empowers clients to flourish and thrive.

In an initial study comparing the effects of traditional and Positive CBT in the treatment of depression, positive CBT resulted in a more substantial reduction of depression symptoms, a more significant increase in happiness, and it was associated with less dropout (Geschwind et al., 2019).

Haven’t had enough CBT tools and techniques yet? Read on for additional useful and effective exercises.

1. Behavioral experiments

These are related to thought experiments, in that you engage in a “what if” consideration. Behavioral experiments differ from thought experiments in that you actually test out these “what ifs” outside of your thoughts (Boyes, 2012).

In order to test a thought, you can experiment with the outcomes that different thoughts produce. For example, you can test the thoughts:

“If I criticize myself, I will be motivated to work harder” versus “If I am kind to myself, I will be motivated to work harder.”

First, you would try criticizing yourself when you need the motivation to work harder and record the results. Then you would try being kind to yourself and recording the results. Next, you would compare the results to see which thought was closer to the truth.

These Behavioral Experiments to Test Beliefs can help you learn how to achieve your therapeutic goals and how to be your best self.

2. Thought records

Thought records are useful in testing the validity of your thoughts (Boyes, 2012). They involve gathering and evaluating evidence for and against a particular thought, allowing for an evidence-based conclusion on whether the thought is valid or not.

For example, you may have the belief “My friend thinks I’m a bad friend.” You would think of all the evidence for this belief, such as “She didn’t answer the phone the last time I called,” or “She canceled our plans at the last minute,” and evidence against this belief, like “She called me back after not answering the phone,” and “She invited me to her barbecue next week. If she thought I was a bad friend, she probably wouldn’t have invited me.”

Once you have evidence for and against, the goal is to come up with more balanced thoughts, such as, “My friend is busy and has other friends, so she can’t always answer the phone when I call. If I am understanding of this, I will truly be a good friend.”

Thought records apply the use of logic to ward off unreasonable negative thoughts and replace them with more balanced, rational thoughts (Boyes, 2012).

Here’s a helpful Thought Record Worksheet to download.

3. Pleasant activity scheduling

This technique can be especially helpful for dealing with depression (Boyes, 2012). It involves scheduling activities in the near future that you can look forward to.

For example, you may write down one activity per day that you will engage in over the next week. This can be as simple as watching a movie you are excited to see or calling a friend to chat. It can be anything that is pleasant for you, as long as it is not unhealthy (i.e., eating a whole cake in one sitting or smoking).

You can also try scheduling an activity for each day that provides you with a sense of mastery or accomplishment (Boyes, 2012). It’s great to do something pleasant, but doing something small that can make you feel accomplished may have more long-lasting and far-reaching effects.

This simple technique can introduce more positivity into your life, and our Pleasant Activity Scheduling Worksheet is designed to help.

4. Imagery-based exposure

This exercise involves thinking about a recent memory that produced strong negative emotions and analyzing the situation.

For example, if you recently had a fight with your significant other and they said something hurtful, you can bring that situation to mind and try to remember it in detail. Next, you would try to label the emotions and thoughts you experienced during the situation and identify the urges you felt (e.g., to run away, to yell at your significant other, or to cry).

Visualizing this negative situation, especially for a prolonged period of time, can help you to take away its ability to trigger you and reduce avoidance coping (Boyes, 2012). When you expose yourself to all of the feelings and urges you felt in the situation and survive experiencing the memory, it takes some of its power away.

This Imagery Based Exposure Worksheet is a useful resource for this exercise.

5. Graded exposure worksheet

This technique may sound complicated, but it’s relatively simple.

Making a situation exposure hierarchy involves means listing situations that you would normally avoid (Boyes, 2012). For example, someone with severe social anxiety may typically avoid making a phone call or asking someone on a date.

Next, you rate each item on how distressed you think you would be, on a scale from 0 to 10, if you engaged in it. For the person suffering from severe social anxiety, asking someone on a date may be rated a 10 on the scale, while making a phone call might be rated closer to a 3 or 4.

Once you have rated the situations, you rank them according to their distress rating. This will help you recognize the biggest difficulties you face, which can help you decide which items to address and in what order. It’s often advised to start with the least distressing items and work your way up to the most distressing items.

Download our Graded Exposure Worksheet here.

Some of these books are for the therapist only, and some are to be navigated as a team or with guidance from the therapist.

There are many manuals out there for helping therapists apply cognitive behavioral therapy in their work, but these are some of the most popular:

- A Therapist’s Guide to Brief Cognitive Behavioral Therapy by Jeffrey A. Cully and Andra L. Teten (PDF here );

- Individual Therapy Manual for Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Depression by Ricardo F. Munoz and Jeanne Miranda (PDF here );

- Provider’s Guidebook: “Activities and Your Mood” by Community Partners in Care (PDF here );

- Treatment Manual for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression by Jeannette Rosselló, Guillermo Bernal, and the Institute for Psychological Research (PDF here ).

Here are some of the most popular workbooks and manuals for clients to use alone or with a therapist:

- The CBT Toolbox: A Workbook for Clients and Clinicians by Jeff Riggenbach ( Amazon );

- Client’s Guidebook: “Activities and Your Mood” by Community Partners in Care (PDF here );

- The Cognitive Behavioral Workbook for Anxiety: A Step-by-Step Program by William J. Knaus and Jon Carlson ( Amazon );

- The Cognitive Behavioral Workbook for Depression: A Step-by-Step Program by William J. Knaus and Albert Ellis ( Amazon );

- Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Skills Workbook by Barry Gregory ( Amazon );

- A Course in CBT Techniques: A Free Online CBT Workbook by Albert Bonfil and Suraji Wagage (online here ).

There are many other manuals and workbooks available that can help get you started with CBT, but the tools above are a good start. Peruse our article: 30 Best CBT Books to Master Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for an excellent list of these books.

1. Mindfulness meditation

Mindfulness can have a wide range of positive impacts, including helping with depression, anxiety, addiction, and many other mental illnesses or difficulties.

The practice can help those suffering from harmful automatic thoughts to disengage from rumination and obsession by helping them stay firmly grounded in the present (Jain et al., 2007).

Mindfulness meditations, in particular, can function as helpful tools for your clients in between therapy sessions, such as to help ground them in the present moment during times of stress.

If you are a therapist who uses mindfulness-based approaches, consider finding or pre-recording some short mindfulness meditation exercises for your clients.

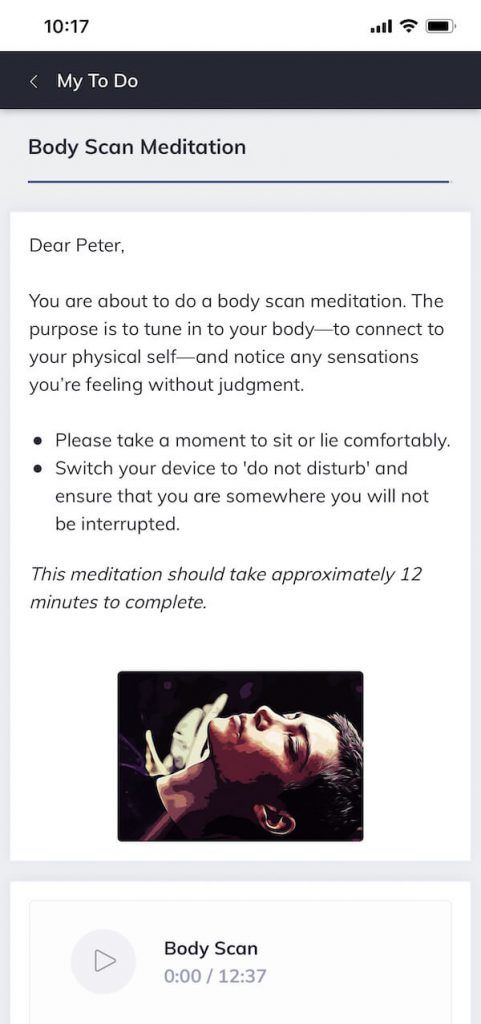

You might then share these with your clients as part of a toolkit they can draw on at their convenience, such as using the blended care platform Quenza (pictured here), which allows clients to access meditations or other psychoeducational activities on-the-go via their portable devices.

2. Successive approximation

This is a fancy name for a simple idea that you have likely already heard of: breaking up large tasks into small steps.

It can be overwhelming to be faced with a huge goal, like opening a business or remodeling a house. This is true in mental health treatment as well, since the goal to overcome depression or anxiety and achieve mental wellness can seem like a monumental task.

By breaking the large goal into small, easy-to-accomplish steps, we can map out the path to success and make the journey seem a little less overwhelming (e.g., Emmelkamp & Ultee, 1974).

3. Writing self-statements to counteract negative thoughts

This technique can be difficult for someone who’s new to CBT treatment or suffering from severe symptoms, but it can also be extremely effective (Anderson, 2014).

When you (or your client) are being plagued by negative thoughts, it can be hard to confront them, especially if your belief in these thoughts is strong. To counteract these negative thoughts, it can be helpful to write down a positive, opposite thought.