- View programs

- Take our program quiz

- Online BBA Degree Program

- ↳ Specialization in Artificial Intelligence

- ↳ Specialization in Business Analytics

- ↳ Specialization in Digital Marketing

- ↳ Specialization in Digital Transformation

- ↳ Specialization in Entrepreneurship

- ↳ Specialization in International Business

- ↳ Specialization in Product Management

- ↳ Specialization in Supply Chain Management

- Online BBA Top-Up Program

- Associate of Applied Science in Business (AAS)

- Online MS Degree Programs

- ↳ MS in Data Analytics

- ↳ MS in Digital Transformation

- ↳ MS in Entrepreneurship

- Online MBA Degree Program

- ↳ Specialization in Cybersecurity

- ↳ Specialization in E-Commerce

- ↳ Specialization in Fintech & Blockchain

- ↳ Specialization in Sustainability

- Undergraduate certificates

- Graduate certificates

- Undergraduate courses

- Graduate courses

- ↳ Data Analytics

- ↳ Data Science

- ↳ Software Development

- Transfer credits

- Scholarships

- For organizations

- Career Coalition

- Accreditation

- Our faculty

- Career services

- Academic model

- Learner stories

- The Global Grid

- Book consultation

- Careers - we're hiring!

Importance of Creativity & Innovation in Entrepreneurship 2024

If entrepreneurs all did business in the same way, in the same industries, in the same marketplace, and with the same products and services, nobody would stand out with a competitive advantage and many businesses would not be in business for very long.

Carving out a niche for yourself as an entrepreneur, or making sure that your Unique Selling Proposition (USPs) helps differentiate your business to make it stand out from the clutter, you need to implement high levels of creativity and innovation into all of your entrepreneurial practices. Innovation and entrepreneurship, and more specifically, cultivating creativity in entrepreneurship is an important process which helps entrepreneurs generate value, useful unique products, services, ideas, procedures, or new business processes.

Role Of Creativity and Innovation In Entrepreneurship

According to Atlantis Press , creativity and innovation helps develop new ways of improving an existing product or service to optimize the business. Successful innovation is the driving force that allows entrepreneurs to think outside the box and beyond the traditional solutions. Through this opportunity new, interesting, potential yet versatile ideas come up.

Overall, creativity and innovation are integral to entrepreneurial success. They empower entrepreneurs to discover opportunities, solve problems, differentiate themselves, adapt to change, continuously improve, and drive business growth. By embracing creativity and fostering an innovative mindset, entrepreneurs can build successful ventures in an ever-evolving business landscape.

Entrepreneurs and creativity

Creativity is an indispensable trait for entrepreneurs. It drives idea generation, opportunity recognition, problem-solving, innovation, and differentiation. Creative entrepreneurs embrace risk, communicate effectively, and continually learn and adapt. By harnessing their creativity, entrepreneurs can navigate challenges, seize opportunities, create new solutions and build successful and impactful ventures.

But creativity does not only assist entrepreneurs in the initial stages of coming up with a business idea. Creativity will also be a driving force and also highly valuable in terms of:

Coming up with branding and marketing ideas

Creative ideas for blogs, other SEO-related content

Finding creative solutions to everyday business problems

Fun and exciting social media strategies

A good balance of linear and lateral thinking

Entrepreneurs and Innovation

Entrepreneurs and innovation go hand in hand. Innovation is a key driver of entrepreneurial success, and entrepreneurs play a critical role in bringing innovative ideas to life. They adapt to change, solve problems, and fuel business growth through innovation. By embracing innovation, entrepreneurs can create disruptive solutions, differentiate themselves in the market, and ultimately achieve entrepreneurial success.

Having a good hold on innovation and as a net result, innovative ideas, is very important for entrepreneurs. Not only will an innovative mindset be advantageous in coming up with products, services, and business ideas, it will also be exceptionally helpful when it comes to adapting to change and finding new and improved ways of doing things in your business structure.

Do you have the skills to be a successful entrepreneur?

Take our free quiz to measure your entrepreneurial skills and see if you have what it takes to run your own successful business.

Your results will help you identify key skill gaps you may have! Up for the challenge?

Benefits of using creativity for innovation

For decades, advertising and marketing companies have used creativity to differentiate innovative products and services being advertised against other like products in the marketplace. Using creativity for innovation can lead you to be a better entrepreneur and infusing creativity into your business makes you an innovative leader within your industry. Without creativity, businesses run the risk of slipping into the clutter that may exist in an industry.

To improve your chances of successful entrepreneurship, here are some of the benefits of being a creative and innovative entrepreneur:

You will be able to create new products or services that solve problems for people

You will be able to improve processes and make them more efficient

You will be able to find new markets for existing products or services

You will be able to create new jobs

You will be able to make a positive impact on society

You will be able to have a lot of fun and satisfaction in what you do

Thinking about Improving your Skills as an Entrepreneur?

Discover how you can acquire the most important skills for creating a widely successful business.

Download the free report now and find out how you can do this and stay ahead of the competition!

And if you're interested in pursuing entrepreneurship further, here at Nexford University , why not consider our excellent selection of BBA , MBA and MS degrees , including our BBA in Entrepreneurship and our MS in Entrepreneurship .

Examples of Entrepreneurial Creativity and Innovation

Apple (steve jobs).

He may have passed away on the 5th of October 2011, but the creative entrepreneurial legacy that Steve Jobs left behind will have a marked impact on all other intrepid tech entrepreneurs that come after him.

Steve Jobs had a never say die attitude and an incredible flair when it came to producing products that were leagues ahead of the competition and so creative that they stood head and shoulders above the competition.

Apple Computer, Inc. was founded on April 1, 1976, by college dropouts Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak, who brought to the new company a vision of changing the way people viewed computers. Jobs and Wozniak wanted to make computers small enough for people to have them in their homes or offices. And they succeeded beyond their wildest imagination.

Entrepreneur magazine says that Steve Jobs systematically cultivated his creativity and so can others. While there's no doubt that Jobs had a naturally creative brain, thanks to modern research, we can see that Jobs' artistry was also due to practices every entrepreneur can adopt to enhance creative thinking.

Jobs' meditation practice helped him develop creativity. Meditative practices, such as "open-monitoring training," encourage divergent thinking, a process of allowing the generation of many new ideas, which is a key part of creative innovation.

Other forces of creative entrepreneurial thinking

Steve Jobs most certainly did not have the monopoly when it came to creative entrepreneurial thinking. Far from it. Many other top creative entrepreneurs came before him, and right now the next wave of creative entrepreneurs are starting to make their mark. Household names such as Richard Branson, Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, and Elon Musk have set the bar very high when it comes to creative thinking, allowing them to build multi-billion dollar empires.

Now whilst they may have had one thing in common which was having a knack for creative thinking, the one thing that leading entrepreneurs and innovators like Bill Gates and J.K. Rowling all have one thing in common and that is that they were all domain experts before launching their businesses. Bill Gates, spent nearly 10 years in school programming in different computer systems before starting Microsoft, whilst J.K. Rowling began writing at the age of six, and spent over seven years refining and perfecting her idea before it became a global sensation and boosted her net worth to over $1 billion.

Conclusion

Whilst people maintain that you are born with creativity and an entrepreneurial flair, others maintain that it can be taught. You may have a great idea, but you’ll need business acumen to turn your idea into a successful, sustainable enterprise. Business degrees give you the space and time to hone these critical skills in a safe environment. A good one will give you opportunities to work on real-life projects or go on placements with industry leaders before launching out on your own. And once you're ready to go solo, you'll have already built an important network of connections and highly creative ways of thinking in an effective way.

If you are looking to up your understanding of business, improve your levels of creativity and promote entrepreneurship when it comes to the branding and running of a business, you might want to consider a university that offers business degrees that involve learning how to be creative and effective in business using real life case studies.

Nexford is just such a university. Expand your entrepreneurial skill set with an online BBA , MBA and MS degrees , including our BBA in Entrepreneurship and our MS in Entrepreneurship .

For a more in-depth analysis download our free report .

Is innovation and creativity key to entrepreneurial success?

Yes, innovation and creativity are key to entrepreneurial success. They are essential elements that drive the growth and sustainability of entrepreneurial ventures. Innovation and creativity are vital for entrepreneurial success. They enable entrepreneurs to differentiate themselves, respond to market changes, solve problems, drive growth, take risks, attract stakeholders, and foster a culture of continuous improvement.

Now whilst there have been many business ideas that were a stroke of genius, or people being in the right place at the right time, it is undeniable that the difference between business success and abject failure is the use of creativity in coming up with a concept and getting it noticed. Not always is it a case of 'if you build it they will come.' It's all about being innovative and never taking no for an answer.

Applied to business, innovation comprises several key elements, including a challenge (to provoke it), creativity (to spark it), contemplation (to come up with an idea), focus on the customers (to sharpen the idea), and communication and cooperation to facilitate the whole process.

How does creativity and innovation work together?

Creativity provides the foundation of new and unique ideas, while innovation is the process of transforming those ideas into tangible outcomes. They work together to generate solutions, improve offerings, take risks, and differentiate in the market. By leveraging both creativity and innovation, entrepreneurs can foster a culture of continuous improvement and drive entrepreneurial success.

Whilst experts say that you are born with an innate sense of creativity and innovation, many others say that there are ways to encourage creativity and innovation. Don't be afraid to take risks and always maintain an open mind.

What is the purpose of innovation in business?

The purpose of innovation in business is to differentiate, meet customer needs, gain a competitive advantage, drive growth, improve operational efficiency, adapt to change, and promote sustainable development. By embracing innovation, businesses can remain relevant, creative, thrive in a dynamic marketplace, and create long-term value for customers and stakeholders.

Creativity and innovation in organizations allows for adaptability, separates a business from its competitors, and fosters growth.

How can you encourage innovation and creativity in the workplace?

Encouraging innovation and creativity in the workplace is crucial for fostering a culture of continuous improvement and driving business success. Here are some ways you can promote an innovative environment in your business with a proven methodology that combines theory and practice:

1. Make innovation a core value

2. Hire people with different perspectives

3. Give employees time and space to innovate

4. Encourage collaboration

5. Have a feedback process

6. Reward employees for great ideas

What strategies can leadership use to enhance creativity and innovation for employees

The importance of creativity and innovation can't be stressed enough and both play a major role in entrepreneurship. The link between creativity and successful businesses is proven. Kelly Personnel maintains that there are four strategies to enhance your team's creativity and improve organizational productivity.

1. Cultivate open communication

Cultivating open communication in the workplace is essential for creating an environment where ideas can freely flow, collaboration can thrive, and innovation can flourish. There are many strategies to cultivate open communication which include; establishing a foundation of trust, encourage active listening, promoting two-way communication, fostering an open-door policy, embracing diverse perspectives, using clear and transparent communication channels, providing communication skills training, and leading by example.

2. Facilitate diverse ways of working

Facilitating diverse ways of working can greatly enhance creativity and innovation within an organization. By embracing diverse ways of working, organizations can tap into the collective creativity and innovation potential of their workforce. It encourages fresh perspectives, drives collaboration, and opens up new possibilities for problem-solving and growth.

3. Intentionally change things up

Intentionally changing things up in the workplace can have a positive impact on creativity and innovation. By intentionally changing things up, organizations can stimulate creativity and foster a culture of innovation. Embracing variety, providing opportunities for cross-pollination, and encouraging experimentation all contribute to an environment where new ideas can flourish, leading to breakthrough innovations and improved problem-solving.

4. Hold guided brainstorm sessions

Holding guided brainstorming sessions can be an effective way to enhance creativity and innovation in the workplace. By conducting guided brainstorming sessions, organizations can tap into the collective creativity and generate innovative ideas. These sessions provide a structured framework for idea generation, encourage collaboration, and inspire employees to think outside the box.

Looking to Improve your Skills as an Entrepreneur?

Mark is a college graduate with Honours in Copywriting. He is the Content Marketing Manager at Nexford, creating engaging, thought-provoking, and action-oriented content.

Join our newsletter and be the first to receive news about our programs, events and articles.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6 Creativity and Innovation in Entrepreneurship

Task Summary:

Lesson 2.3.1: Entrepreneurial Creativity and Innovation

Lesson 2.3.2: Design Thinking

Activity 2.3.1: Read/Watch/Listen – Reflect

Activity 2.3.2: Journal Entry

- Unit 2 Assignment: The Makings of a Successful Entrepreneur

Learning Outcomes:

- Define creativity and innovation in an entrepreneurial context

- Reflect on various perspectives on creativity and innovation in an entrepreneurial context

- Assess the potential of design thinking

- Identify the characteristics that resonate with you as being critical to entrepreneurial success

Creativity and innovation are what make the world go around and continue to improve and evolve! There have been lots of great ideas and thoughts around the creative and innovative process for entrepreneurs, as this is a key part of the problem identification process. Have a look at what some resident experts have said about creativity and innovation from an entrepreneurial lens.

Systematic innovation involves “monitoring seven sources for an innovative opportunity” (Drucker, 1985). The first four are internally focused within the business or industry, in that they may be visible to those involved in that organization or sector. The last three involve changes outside the business or industry.

- The unexpected (unexpected success, failure, or outside events)

- The incongruity between reality as it actually is and reality as it is assumed to be or as it ought to be

- Innovation based on process need

- Changes in industry structure or market structure that catch everyone unawares

- Demographics (population changes)

- Changes in perception, mood, and meaning

- New knowledge, both scientific and nonscientific

One of the components of Mitchell’s (2000) New Venture Template asks whether the venture being examined represents a new combination. To determine this, he suggests considering two categories of entrepreneurial discovery: scientific discovery and circumstance .

- Physical/technological insight

- A new and valuable way

- Specific knowledge of time, place, or circumstance

- When and what you know

The second set of variables to consider are the market imperfections that can create profit opportunities: excess demand and excess supply . This gives rise to the following four types of entrepreneurial discovery.

- Uses science to exploit excess demand (a market imperfection)

- Becomes an opportunity to discover and apply the laws of nature to satisfy excess demand

- Inventions in one industry have ripple effects in others

- Example: the invention of the airplane

- Circumstances reveal an opportunity to exploit excess demand (a market imperfection)

- Not necessarily science-oriented

- Example: airline industry = need for food service for passengers

- Uses science to exploit excess supply (a market imperfection)

- Example: Second most abundant element on earth after oxygen = silicon microchips

- Circumstances reveal an opportunity to exploit excess supply (a market imperfection)

- Example: Producer’s capacities to lower prices = Wal-Mart

Schumpeter’s (1934) five kinds of new combinations can occur within each of the four kinds of entrepreneurial discovery (Mitchell, 2000):

- The distinction between true advances and promotional differences

- Example: assembly line method to automobile production, robotics, agricultural processing

- Global context: Culture, laws, local buyer preferences, business practices, customs, communication, transportation all set up new distribution channels

- Example: Honda created a new market for smaller modestly powered motorbikes

- Enhance availability of products by providing at lower cost

- Enhance availability by making more available without compromising quality

- Reorganization of an industry

Murphy (2011) claimed that there was a single-dimensional logic that oversimplified the approach taken to understand entrepreneurial discovery. He was bothered by the notion that entrepreneurs either deliberately searched for entrepreneurial opportunities or they serendipitously discovered them. Murphy’s (2011) multidimensional model of entrepreneurial discovery suggests that opportunities may be identified (a) through a purposeful search; (b) because others provide the opportunity to the entrepreneur; (c) through prior knowledge, entrepreneurial alertness, and means other than a purposeful search; and, (d) through a combination of lucky happenstance and deliberate searching for opportunities.

According to experimentation research, entrepreneurial creativity is not correlated with IQ (people with high IQs can be unsuccessful in business and those with lower IQs can be successful as an entrepreneur). Research has also shown that those who practice idea generation techniques can become more creative. The best ideas sometimes come later in the idea-generation process—often in the days and weeks following the application of the idea-generating processes (Vesper, 1996).

Vesper (1996) identified several ways in which entrepreneurs found ideas:

- Chance event

- Answering discovery questions

Although would-be entrepreneurs usually don’t discover ideas by a deliberate searching strategy (except when pursuing acquisitions of ongoing firms), it is nevertheless possible to impute to their discoveries some implicit searching patterns. (Vesper, 1996)

Vesper (1996) categorized discovery questions as follows:

- What is bothering me and what might relieve that bother?

- How could this be made or done differently than it is now?

- What else might I like to have?

- How can I fall the family tradition?

- Can I play some role in providing this product or service to a broader market?

- Could there be a way to do this better for the customer?

- Could I do this job on my own instead of as an employee?

- If people elsewhere went for this idea, might they want it here too?

Vesper (1996) also highlighted several mental blocks to departure . He suggested that generating innovative ideas involved two tasks: to depart from what is usual or customary and to apply an effective way to direct this departure. The mental blocks in the way of departure include the following:

- difficulty viewing things from different perspectives

- seeing only what you expect to see or think what others expect you to see

- intolerance of ambiguity

- preference for judging rather than seeking ideas

- tunnel vision

- insufficient patience

- a belief that reason and logic are superior to feeling, intuition, and other such approaches

- thinking that tradition is preferable to change

- disdain for fantasy, reflection, idea playfulness, humor

- fear of subconscious thinking

- inhibition about some areas of imagination

- distrust of others who might be able to help

- distractions

- discouraging responses from other people

- lack of information

- incorrect information

- weak technical skills in areas such as financial analysis

- poor writing skills

- inability to construct prototypes

Understanding these mental blocks to departure is a first step in figuring out how to cope with them. Some tactics for departure include the following (Vesper, 1996):

- Trying different ways of looking at and thinking about venture opportunities

- Trying to continually generate ideas about opportunities and how to exploit them

- Seeking clues from business and personal contacts, trade shows, technology licensing offices, and other sources

- Not being discouraged by others’ negative views because many successful innovations were first thought to be impossible to make

- Generating possible solutions to obstacles before stating negative views about them

- Brainstorming

- Considering multiple consequences of possible future events or changes

- Rearranging, reversing, expanding, shrinking, combining, or altering ideas

- Developing scenarios

The Hasso Plattner Institute of Design at Stanford University called the d.school ( http://dschool.stanford.edu/ ), is an acknowledged leader at promoting design thinking. You can download the Bootcamp Bootleg manual from the d.school website at https://dschool.stanford.edu/resources/the-bootcamp-bootleg . The following description of design thinking is from the IDEO website:

Design thinking is a deeply human process that taps into abilities we all have but get overlooked by more conventional problem-solving practices. It relies on our ability to be intuitive, to recognize patterns, to construct ideas that are emotionally meaningful as well as functional, and to express ourselves through means beyond words or symbols. Nobody wants to run an organization on feeling, intuition, and inspiration, but an over-reliance on the rational and the analytical can be just as risky. Design thinking provides an integrated third way.

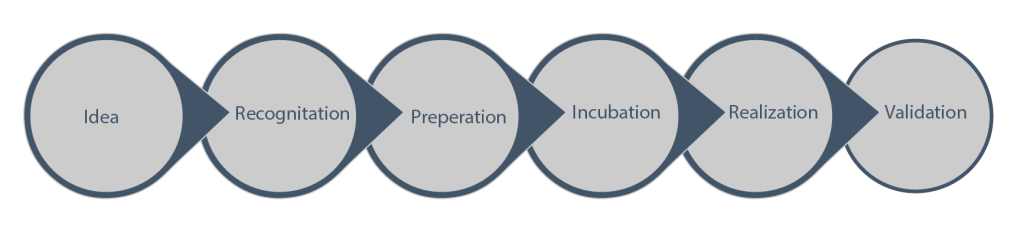

The design thinking process is best thought of as a system of overlapping spaces rather than a sequence of orderly steps. There are three spaces to keep in mind: inspiration , ideation , and implementation . Inspiration is the problem or opportunity that motivates the search for solutions. Ideation is the process of generating, developing, and testing ideas. Implementation is the path that leads from the project stage into people’s lives (IDEO, 2015).

Today is all about taking some time to sit the value of creativity and innovation in entrepreneurship. Similar to previous activities, this is all done with the intent to develop your own understanding of the characteristics needed for success in entrepreneurship. Pay close attention to characteristics and leanings that resonate with you, and are particularly appealing. Remember, at the end of this module you will be developing either a 250-word document, infographic, or a three-minute presentation on the characteristics that make an entrepreneurial thinker and leader successful.

The key steps are:

- Choose five (5) videos from this Innovation Playlist to watch

- Building on what you have learned throughout this unit, identify the characteristics that resonate with you as being critical to success and appealing to you personally

- Reflect on why these characteristics are critical and appealing

- Reflect on how these characteristics, or lack thereof, could impact your own success as an entrepreneur

- Reflect on how you can strengthen these characteristics to support your own entrepreneurial success over the next 18 months

As a reminder, journaling can be a really powerful way to learn because it gets us to pause and reflect not only on what we have learned but also on what it means to us. Journaling makes meaning of material in a way that is personal and powerful. Similar to your unit end reflection in Unit 1, we are going to take a slightly different approach for this journal, which focuses on developing an action plan given your previous two journal reflections. Here, you will develop a plan of action for immediate learning challenges, such as the unit assignments featured in this course. Recall in the past two journals you reflected on key learning (not content) aspects you found challenging. You will reconsider your strengths, weaknesses, and key learnings and determine specific steps to prepare and complete the oncoming learning challenge of designing the entrepreneurial process for yourself. Your reflection entries should be either 300 to 500 written words or a video that is approximately 5 minutes.

Using your past two journal reflections and your learning experience in Unit 2, Module 3, reflect on the following:

- If there was not a particular concept that was easy to understand, reflect on why this was the case

- If there was not a particular concept that was difficult to understand, reflect on why this was the case

- Develop a meaningful plan with clear and specific actions you need to take, how you will take them, and when you will take them, to address any challenges or weaknesses before you complete your Unit 2 Assignment: The Makings of a Successful Entrepreneur.

Media Attributions

- Photo of Innovation by Michal Jarmoluk on Pixabay .

Text Attributions

- The content related to the Ways of Identifying Opportunities was taken from “ Entrepreneurship and Innovation Toolkit, 3rd Edition ” by L. Swanson (2017) CC BY-SA

Drucker, P. F. (1985). Innovation and entrepreneurship: Practice and principles . p. 35. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

IDEO. (2015). About IDEO. para. 7-8. Retrieved from http://www.ideo.com/about/

Mitchell, R. K. (2000). Introduction to the Venture Analysis Standards 2000: New Venture Template Workbook . Victoria, B.C., Canada: International Centre for Venture Expertise

Murphy, P. J. (2011). A 2 x 2 conceptual foundation for entrepreneurial discovery theory. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35 (2), 359-374. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00368.x

Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The theory of economic development : An inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest, and the business cycl e (R. Opie, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Vesper, K. H. (1996). New venture experience (revised ed.). p. 60. Seattle, WA: Vector Books

Introduction to Entrepreneurship Copyright © 2021 by Katherine Carpenter is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Hand-Illustrated Explainer Videos

- Illustrated Conversation

- Infographics

- Strategy & Ideas

- Training Design & Development

- Event Communications

- Video Production

- Scripting & Script Assistance

- llustration

- Our Method: Scribology

- Our Process

- Our Guarantee

- What We Care About

- General Contact Info

- Book a Consult

- Book a Quote

- Schedule an Artist

The Role of Creativity in Entrepreneurship

Andrew Herkert

April 28th, 2022

Creativity in Business

Creativity is a necessity in a thriving business, but how often do we consider the role of creative thinking in the formation of a business? Creativity is just as crucial for entrepreneurs as it is for those looking to maintain an advantage over the competition in well-established organizations. Let’s see just how creativity can benefit the successful entrepreneur.

Innovation, Risk Taking, and Thinking the Unthinkable

Anastasia Belyh gives us a good place to start by helping us see where creativity naturally fits into this role . Innovation, the first characteristic of the role that Belyh lists, entails creative ideation. As she puts it, “There is a continuous and conscious effort required to look for niches and undertake the risks in entering them,” and there’s a constant need to improve on existing business workflows.

Risk taking is another area where creativity is necessary—in fact, Belyh argues that “The whole essence of entrepreneurship revolves around the courage and ability to take new risks.” Those risks involve more than innovative business workflows. Entrepreneurs strive to develop new and inventive products, and meet customer needs while pleasantly surprising them. They work to earn and maintain a competitive edge. They work with investors to meet financial needs while the business becomes profitable.

Thinking creatively allows an entrepreneur to come up with the ideas worth bringing to bear on their business. Belyh calls this “thinking the unthinkable” and describes the ability of entrepreneurs to “think beyond the traditional solutions, come up with something new, interesting, versatile, and yet have success potential.”

Adaptation and Success as a Continuum

Of course, there’s more to creativity than ideation , as Nicolas Susco contends—it’s not “just about coming up with ideas. It’s about being able to adapt to new circumstances, navigate uncertainty, and find solutions as problems arise.”

Success depends on the ability to pivot, even when this means pivoting away from a good thing. “Sometimes entrepreneurs get caught up in the success of their initial idea. They feel it’s so amazing that they never have to be creative again.” The entrepreneurs who succeed over time are the ones who don’t become complacent, but “use their creativity over and over” and reevaluate even what’s worked in the past.

A creative entrepreneur is also one who doesn’t see success as an endpoint—or, rather, one sees success as a moving target. “Just because your business is doing fine, that doesn’t mean it can’t do better ,” Susco points out, and reinforces the importance of creativity in surviving complacency: “Sometimes sitting back allows a competitor to innovate and put you out of business with a more creative solution.”

This is something that bears a moment of serious thought: whether or not you are committed to creativity, you have competitors that are. If you don’t fight fire with fire, you will be burned out by other firms working to develop next-level solutions and offerings.

Increasing Your Creativity: Going Analog

Now, let’s shift gears. Creativity matters to the entrepreneur, their products, their ability to contend with change, their chances to compete, and their ability to stave off complacency—so how can an entrepreneur become (and remain) creative?

John Boitnott of entrepreneur.com suggests first “free[ing] your mind to take those flights of fancy that result in heightened creativity” in his tips to help entrepreneurs unlock the creativity inside them. Boitnott’s suggestion for freeing the mind is to use your hands instead of your phone. Find an ‘analog’ activity (“anything that requires repetitive movements and little intellectual analysis”) and let your mind drift through a far more creative thought process.

Expanding Your Horizons

It’s also important to take stock of, and value, the creativity of others as you work to cultivate it in yourself. Boitnott suggests pursuing creative expression that you might not typically look into, like a movie or museum exhibit that you might otherwise skip.

Why should you go see art that would normally not match your interests? It can certainly give you ideas, but more than that, it can remind you of the scope of creativity. You might love movies, say, but this experiment might show you an art film or unconventional work that you hardly knew was possible. And beyond others’ creative output, try to “look for other people’s creative decision-making skills.”

This second part of appreciating others might be even more useful to the entrepreneur interested in increasing their creativity. Watching successful, innovative problem-solving, conflict resolution, or other decision-making situations involving others can create inspirational lightbulb moments. When you find yourself thinking “It never occurred to me to try this approach—look how well it works,” take a note.

The last of Boitnott’s suggestions for open-minded ideation is also a great final piece of advice for the creativity-interested entrepreneur: meditate often. Meditation serves many purposes, but in this context, its primary purpose is to quiet the mind and “power down.”

As in the analog activity advice, this freeing of the mind allows creative thinking to come much more easily. Open-monitoring meditation, “where you simply sit quietly and observe without judging whatever is going on around and within you,” is Boitnott’s suggestion for the greatest benefit.

Creativity is Indispensable

Creative thinking is crucial to an entrepreneur’s ability to gain traction with their business and maintain forward momentum. It promotes divergent, innovative thought in business processes, product design, and more, and encourages continuous reevaluation of circumstances.

Creativity is often the key differentiator between startups that do well for a time before becoming complacent and folding, and startups who enjoy lasting success. How will you become a more creative business leader—even if your ‘entrepreneur days’ are behind you?

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- *New* Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

The Importance of Creativity in Business

- 25 Jan 2022

When you think of creativity, job titles such as graphic designer or marketer may come to mind. Yet, creativity and innovation are important across all industries because business challenges require inventive solutions.

Here’s an overview of creativity’s importance in business, how it pairs with design thinking, and how to encourage it in the workplace.

Access your free e-book today.

Why Is Creativity Important?

Creativity serves several purposes. It not only combats stagnation but facilitates growth and innovation. Here's why creativity is important in business.

1. It Accompanies Innovation

For something to be innovative, there are two requirements: It must be novel and useful. While creativity is crucial to generate ideas that are both unique and original, they’re not always inherently useful. Innovative solutions can’t exist, however, without a component of creativity.

2. It Increases Productivity

Creativity gives you the space to work smarter instead of harder, which can increase productivity and combat stagnation in the workplace. Routine and structure are incredibly important but shouldn’t be implemented at the expense of improvement and growth. When a creative and innovative environment is established, a business’s productivity level can spike upward.

3. It Allows for Adaptability

Sometimes events—both internal and external—can disrupt an organization’s structure. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically changed how the present-day business world functions . In such instances, imaginative thinking and innovation are critical to maintaining business operations.

Creatively approaching challenges requires adaptability but doesn’t always necessitate significantly adjusting your business model. For example, you might develop a new product or service or slightly modify the structure of your operations to improve efficiency. Big problems don’t always require big solutions, so don’t reject an idea because it doesn’t match a problem’s scale.

Change is inevitable in the business world, and creative solutions are vital to adapting to it.

4. It’s Necessary for Growth

One of the main hindrances to a business’s growth is cognitive fixedness, or the idea that there’s only one way to interpret or approach a situation or challenge.

Cognitive fixedness is an easy trap to fall into, as it can be tempting to approach every situation similar to how you have in the past. But every situation is different.

If a business’s leaders don’t take the time to clearly understand the circumstances they face, encourage creative thinking, and act on findings, their company can stagnate—one of the biggest barriers to growth.

5. It’s an In-Demand Skill

Creativity and innovation are skills commonly sought after in top industries, including health care and manufacturing. This is largely because every industry has complex challenges that require creative solutions.

Learning skills such as design thinking and creative problem-solving can help job seekers set themselves apart when applying to roles.

Creativity and Design Thinking

While creativity is highly important in business, it’s an abstract process that works best with a concrete structure. This is where design thinking comes into play.

Design thinking —a concept gaining popularity in the business world—is a solutions-based process that ventures between the concrete and abstract. Creativity and innovation are key to the design thinking process.

In Harvard Business School Dean Srikant Datar’s course Design Thinking and Innovation , the process is broken down into four iterative stages:

- Clarify: In this stage, observation and empathy are critical. Observations can be either concrete and based on metrics and facts or abstract and gleaned from understanding and empathy. The goal during this stage is to gain an understanding of the situation and individuals impacted.

- Ideate: The ideation stage is abstract and involves creativity and idea generation. Creativity is a major focus, as the ideation phase provides the freedom to brainstorm and think through solutions.

- Develop: The development phase is a concrete stage that involves experimentation and trial and error. Critiquing and prototyping are important because the ideas generated from the ideation stage are formed into testable solutions.

- Implement: The fourth stage is solution implementation. This involves communicating the solution’s value and overcoming preexisting biases.

The value of design thinking is that it connects creativity and routine structure by encouraging using both the operational and innovation worlds. But what are these worlds, and how do they interact?

The Operational World

The operational world is the concrete, structured side of business. This world focuses on improving key metrics and achieving results. Those results are typically achieved through routine, structure, and decision-making.

The operational world has many analytical tools needed for the functional side of business, but not the innovative side. Furthermore, creativity and curiosity are typically valued less than in the innovation world. Employees who initiate unsuccessful, risky endeavors are more likely to be reprimanded than promoted.

The Innovation World

The innovation world requires curiosity, speculation, creativity, and experimentation. This world is important for a company’s growth and can bring about the aforementioned benefits of creativity in business.

This world focuses more on open-ended thinking and exploration rather than a company’s functional side. Although risky endeavors are encouraged, there’s little structure to ensure a business runs efficiently and successfully.

Connecting the Two Worlds

Although the operational world and innovation world are equally important to a business’s success, they’re separate . Business leaders must be ambidextrous when navigating between them and provide environments for each to flourish.

Creativity should be encouraged and innovation fostered, but never at the expense of a business’s functionality. The design thinking process is an excellent way to leverage both worlds and provides an environment for each to succeed.

Since the design thinking process moves between the concrete and abstract, it navigates the tension between operations and innovation. Remember: The operational world is the implementation of the innovative world, and innovation can often be inspired by observations from the operational world.

How to Encourage Creativity and Innovation

If you want to facilitate an innovative workplace, here are seven tips for encouraging creativity.

1. Don’t Be Afraid to Take Risks

Creativity often entails moving past your comfort zone. While you don't want to take risks that could potentially cripple your business, risk-taking is a necessary ingredient of innovation and growth. Therefore, providing an environment where it’s encouraged can be highly beneficial.

2. Don’t Punish Failure

Provide your team with the freedom to innovate without fear of reprisal if their ideas don’t work. Some of the best innovations in history were the product of many failures. View failure as an opportunity to learn and improve for the future rather than defeat.

3. Provide the Resources Necessary to Innovate

While it can be tempting to simply tell your team to innovate, creativity is more than just a state of mind. If your colleagues have the opportunity to be creative, you need to provide the resources to promote innovation. Whether that entails a financial investment, tools, or training materials, it’s in your best interest to invest in your team to produce innovative results.

4. Don’t Try to Measure Results Too Quickly

If an innovative idea doesn’t produce desirable results within a few months, you may consider discarding it entirely. Doing so could result in a lost opportunity because some ideas take longer to yield positive outcomes.

Patience is an important element of creativity, so don't try to measure results too quickly. Give your team the freedom to improve and experiment without the pressure of strict time constraints.

5. Maintain an Open Mind

One of the most important components of an environment that fosters creativity and innovation is keeping an open mind. Innovation requires constantly working against your biases. Continually ask questions, be open to the answers you receive, and don't require fully conceptualized ideas before proceeding with innovation.

6. Foster Collaboration

Collaborative environments are vital for innovation. When teams work together in pursuit of a common goal, innovation flourishes. To achieve this, ensure everyone has a voice. One way to do so is by hosting brainstorming sessions where each member contributes and shares ideas.

7. Encourage Diversity

Diversity fosters creativity and combats groupthink, as each individual brings a unique outlook to the table. Consider forming teams with members from different cultural backgrounds who haven’t previously worked together. Getting people to step outside their comfort zones is an effective way to encourage innovation.

Learning to Be Creative in Business

Creativity and innovation are immensely important skills whether you’re a job seeker, employer, or aspiring entrepreneur.

Want to learn more about design thinking? Start by finding fellow professionals willing to discuss and debate solutions using its framework. Take advantage of these interactions to consider how you can best leverage design thinking and devise different approaches to business challenges.

This exposure to real-world scenarios is crucial to deciding whether learning about design thinking is right for you. Another option is to take an online course to learn about design thinking with like-minded peers.

If you’re ready to take your innovation skills to the next level, explore our online course Design Thinking and Innovation , one of our online entrepreneurship and innovation courses. If you aren't sure which course is the right fit, download our free course flowchart to determine which best aligns with your goals.

About the Author

More From Forbes

How to be creative as an entrepreneur.

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

You might think that creativity requires the antithesis of rules and regulation. Even the thought of being creative conjures up images of disorder. Messy rooms, paint everywhere, scraps of paper with ideas scrawled across them. The frantic creative genius works away, oblivious to the world around them. Chaos. Method in madness. Flashes of brilliance among a cluttered existence.

How to be creative as an entrepreneur

The best entrepreneurs are creative. They need to find ways of solving old and new problems. They picture a world that doesn’t yet exist, they bring products to life using only their imagination. They think of ways to move forward, grow bigger and stand out. Doing more with the same tools doesn’t happen by accident, it’s intentional and it requires ideas.

Consistency and creativity

Although at a glance they seem to conflict, the secret to creativity is consistency. It’s a myth that creativity has to come from chaos. Creativity rarely exists without routine and order of some sort.

Consistency creates the framework from which genius can emerge. It underpins it. Inventors conjure up thousands of ideas before discovering the one that changes everything. Van Gogh made art daily, cycling various techniques until he found his calling, and even then it wasn’t appreciated until after his death. Business leaders follow repeatable routines of daily actions, trusting that they will one day reap what they sow.

Keishawn Blackstone is an entrepreneur in the entertainment industry, running tak3-One-Productions. He’s 24 and was born in Los Angeles. He didn’t go to college; educated instead by experiences and books. With three director credits on his IMDB, Blackstone’s early success has stemmed from his healthy habits. He meticulously plans his day and ensures consistency throughout his week. Blackstone stands by the mantra, “no rules”, and “set[s] no boundaries about how far or high the ultimate goal can be,” yet boundaries that keep him sharp and progressing define his day. It seems contradictory, but it works.

Emma Stone Wins 2024 Oscars Best Actress, Topping Fellow Favorite Lily Gladstone

‘oppenheimer’ does not break record for most oscar wins, academy awards 2024: how many oscars did ‘oppenheimer’ win, decision fatigue.

Limitless achievement requires limits. Unwavering confidence requires humility. Brilliant creativity requires routine. It’s an arena of paradoxes. Business coach Melitta Campbell said, “It's hard to be creative when your parameters are too broad, so the first step is to narrow your focus. Go back to your purpose and your clients’ needs, for example, and ask yourself, ‘could this work if..?’ Once you set yourself some limits, your creativity kicks in.”

Decision fatigue is real. Waking up only to spend time deciding what to wear and eat and where to work is a waste of mental energy that could be better spent elsewhere. Removing mundane decisions by setting and sticking to rules reduces physical and mental clutter. It makes space for experimentation within safe confines and helps creativity thrive.

Remove daily decision-making on things that don’t matter by planning your week ahead of time; meal prepping on a Sunday or planning the first thing you’ll do each day. Remove yourself as a bottleneck to decisions by training and trusting a team member to make them. Set personal policies on what you do and don’t do after or before certain times. They might include not checking email until 10am, not responding to friends’ messages until lunch, not doing admin of any sort until you have created something, whatever that might be.

Morning routines

The morning is a glorious time because your head is fresh from resting and everyone else is still asleep. There are fewer vies for your attention.

You can read about the morning routines of world class performers online, and it’s a common question in media interviews with successful entrepreneurs. Whilst reading you’ll notice that there is no commonality in the specific actions. The commonality is that a routine exists. It matters less what you do, it matters more that you do it the same every day.

The opposite of having a morning routine is meandering through your day paying attention to anything that tries to grab it. It will likely lead to having a day on someone else’s agenda; fulfilling their goals and being at the mercy of their needs. Mindlessly scrolling the news waiting for something to react to, seeing what has hit your inbox since yesterday, checking social media platforms or bank accounts or status reports; it all can wait.

New stimulus

Find inspiration from areas outside of your field. Jewellery designer Lucille Whiting knows that tunnel vision doesn’t aid her creative work. “Never stop learning” she advised, “seek out new ideas and talk to new people online or otherwise. Read, take photographs, journal, keep a hundred notebooks to draw, doodle and scribble down midnight ideas. Collect, take screen shots, add webpages to favourites and keep them in organised files.”

Content strategist Kirsty Bartholomew encourages cross-sector learning on the hunt for new ideas, “Get curious about how other people in different markets and niches build their business. It really opens your eyes to different opportunities and can shake up your ideas.” Founder of Coven Girl Gang, Sapphire Bates, knows that rest is as vital as work, “Ensure you make time for things that aren't work. My best ideas come when I'm not working. I can be doing literally anything else; cooking, walking, phoning a friend, doing a puzzle, anything that allows my brain some space from my business to step back and think creatively.”

Be creative as an entrepreneur by being open to absorbing and processing new information. Let novel points of view sit in the back of your mind until the inspiration you seek comes forward of its own accord. Let yourself be inspired.

Being creative as an entrepreneur

Clearing the way for creativity requires incorporating consistency and operating within a framework. It requires removing pointless decisions and creating routines and habits that will continue to serve you. It means being intentional with every second of your day, especially the morning. It means being open to learning outside your industry, scope and office.

Laying the foundations clears space for creativity to emerge. It makes room for ideas, experimentation and lets inspiration strike.

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

- 4.2 Creativity, Innovation, and Invention: How They Differ

- Introduction

- 1.1 Entrepreneurship Today

- 1.2 Entrepreneurial Vision and Goals

- 1.3 The Entrepreneurial Mindset

- Review Questions

- Discussion Questions

- Case Questions

- Suggested Resources

- 2.1 Overview of the Entrepreneurial Journey

- 2.2 The Process of Becoming an Entrepreneur

- 2.3 Entrepreneurial Pathways

- 2.4 Frameworks to Inform Your Entrepreneurial Path

- 3.1 Ethical and Legal Issues in Entrepreneurship

- 3.2 Corporate Social Responsibility and Social Entrepreneurship

- 3.3 Developing a Workplace Culture of Ethical Excellence and Accountability

- 4.1 Tools for Creativity and Innovation

- 4.3 Developing Ideas, Innovations, and Inventions

- 5.1 Entrepreneurial Opportunity

- 5.2 Researching Potential Business Opportunities

- 5.3 Competitive Analysis

- 6.1 Problem Solving to Find Entrepreneurial Solutions

- 6.2 Creative Problem-Solving Process

- 6.3 Design Thinking

- 6.4 Lean Processes

- 7.1 Clarifying Your Vision, Mission, and Goals

- 7.2 Sharing Your Entrepreneurial Story

- 7.3 Developing Pitches for Various Audiences and Goals

- 7.4 Protecting Your Idea and Polishing the Pitch through Feedback

- 7.5 Reality Check: Contests and Competitions

- 8.1 Entrepreneurial Marketing and the Marketing Mix

- 8.2 Market Research, Market Opportunity Recognition, and Target Market

- 8.3 Marketing Techniques and Tools for Entrepreneurs

- 8.4 Entrepreneurial Branding

- 8.5 Marketing Strategy and the Marketing Plan

- 8.6 Sales and Customer Service

- 9.1 Overview of Entrepreneurial Finance and Accounting Strategies

- 9.2 Special Funding Strategies

- 9.3 Accounting Basics for Entrepreneurs

- 9.4 Developing Startup Financial Statements and Projections

- 10.1 Launching the Imperfect Business: Lean Startup

- 10.2 Why Early Failure Can Lead to Success Later

- 10.3 The Challenging Truth about Business Ownership

- 10.4 Managing, Following, and Adjusting the Initial Plan

- 10.5 Growth: Signs, Pains, and Cautions

- 11.1 Avoiding the “Field of Dreams” Approach

- 11.2 Designing the Business Model

- 11.3 Conducting a Feasibility Analysis

- 11.4 The Business Plan

- 12.1 Building and Connecting to Networks

- 12.2 Building the Entrepreneurial Dream Team

- 12.3 Designing a Startup Operational Plan

- 13.1 Business Structures: Overview of Legal and Tax Considerations

- 13.2 Corporations

- 13.3 Partnerships and Joint Ventures

- 13.4 Limited Liability Companies

- 13.5 Sole Proprietorships

- 13.6 Additional Considerations: Capital Acquisition, Business Domicile, and Technology

- 13.7 Mitigating and Managing Risks

- 14.1 Types of Resources

- 14.2 Using the PEST Framework to Assess Resource Needs

- 14.3 Managing Resources over the Venture Life Cycle

- 15.1 Launching Your Venture

- 15.2 Making Difficult Business Decisions in Response to Challenges

- 15.3 Seeking Help or Support

- 15.4 Now What? Serving as a Mentor, Consultant, or Champion

- 15.5 Reflections: Documenting the Journey

- A | Suggested Resources

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Distinguish between creativity, innovation, and invention

- Explain the difference between pioneering and incremental innovation, and which processes are best suited to each

One of the key requirements for entrepreneurial success is your ability to develop and offer something unique to the marketplace. Over time, entrepreneurship has become associated with creativity , the ability to develop something original, particularly an idea or a representation of an idea. Innovation requires creativity, but innovation is more specifically the application of creativity. Innovation is the manifestation of creativity into a usable product or service. In the entrepreneurial context, innovation is any new idea, process, or product, or a change to an existing product or process that adds value to that existing product or service.

How is an invention different from an innovation? All inventions contain innovations, but not every innovation rises to the level of a unique invention. For our purposes, an invention is a truly novel product, service, or process. It will be based on previous ideas and products, but it is such a leap that it is not considered an addition to or a variant of an existing product but something unique. Table 4.2 highlights the differences between these three concepts.

One way we can consider these three concepts is to relate them to design thinking. Design thinking is a method to focus the design and development decisions of a product on the needs of the customer, typically involving an empathy-driven process to define complex problems and create solutions that address those problems. Complexity is key to design thinking. Straightforward problems that can be solved with enough money and force do not require much design thinking. Creative design thinking and planning are about finding new solutions for problems with several tricky variables in play. Designing products for human beings, who are complex and sometimes unpredictable, requires design thinking.

Airbnb has become a widely used service all over the world. That has not always been the case, however. In 2009, the company was near failure. The founders were struggling to find a reason for the lack of interest in their properties until they realized that their listings needed professional, high-quality photographs rather than simple cell-phone photos. Using a design thinking approach, the founders traveled to the properties with a rented camera to take some new photographs. As a result of this experiment, weekly revenue doubled. This approach could not be sustainable in the long term, but it generated the outcome the founders needed to better understand the problem. This creative approach to solving a complex problem proved to be a major turning point for the company. 7

People who are adept at design thinking are creative, innovative, and inventive as they strive to tackle different types of problems. Consider Divya Nag , a millennial biotech and medical device innovation leader, who launched a business after she discovered a creative way to prolong the life of human cells in Petri dishes. Nag’s stem-cell research background and her entrepreneurial experience with her medical investment firm made her a popular choice when Apple hired her to run two programs dedicated to developing health-related apps, a position she reached before turning twenty-four years old. 8

Creativity, innovation, inventiveness, and entrepreneurship can be tightly linked. It is possible for one person to model all these traits to some degree. Additionally, you can develop your creativity skills, sense of innovation, and inventiveness in a variety of ways. In this section, we’ll discuss each of the key terms and how they relate to the entrepreneurial spirit.

Entrepreneurial creativity and artistic creativity are not so different. You can find inspiration in your favorite books, songs, and paintings, and you also can take inspiration from existing products and services. You can find creative inspiration in nature, in conversations with other creative minds, and through formal ideation exercises, for example, brainstorming. Ideation is the purposeful process of opening up your mind to new trains of thought that branch out in all directions from a stated purpose or problem. Brainstorming , the generation of ideas in an environment free of judgment or dissension with the goal of creating solutions, is just one of dozens of methods for coming up with new ideas. 9

You can benefit from setting aside time for ideation. Reserving time to let your mind roam freely as you think about an issue or problem from multiple directions is a necessary component of the process. Ideation takes time and a deliberate effort to move beyond your habitual thought patterns. If you consciously set aside time for creativity, you will broaden your mental horizons and allow yourself to change and grow. 10

Entrepreneurs work with two types of thinking. Linear thinking —sometimes called vertical thinking —involves a logical, step-by-step process. In contrast, creative thinking is more often lateral thinking , free and open thinking in which established patterns of logical thought are purposefully ignored or even challenged. You can ignore logic; anything becomes possible. Linear thinking is crucial in turning your idea into a business. Lateral thinking will allow you to use your creativity to solve problems that arise. Figure 4.5 summarizes linear and lateral thinking.

It is certainly possible for you to be an entrepreneur and focus on linear thinking. Many viable business ventures flow logically and directly from existing products and services. However, for various reasons, creativity and lateral thinking are emphasized in many contemporary contexts in the study of entrepreneurship. Some reasons for this are increased global competition, the speed of technological change, and the complexity of trade and communication systems. 11 These factors help explain not just why creativity is emphasized in entrepreneurial circles but also why creativity should be emphasized. Product developers of the twenty-first century are expected to do more than simply push products and innovations a step further down a planned path. Newer generations of entrepreneurs are expected to be path breakers in new products, services, and processes.

Examples of creativity are all around us. They come in the forms of fine art and writing, or in graffiti and viral videos, or in new products, services, ideas, and processes. In practice, creativity is incredibly broad. It is all around us whenever or wherever people strive to solve a problem, large or small, practical or impractical.

We previously defined innovation as a change that adds value to an existing product or service. According to the management thinker and author Peter Drucker , the key point about innovation is that it is a response to both changes within markets and changes from outside markets. For Drucker, classical entrepreneurship psychology highlights the purposeful nature of innovation. 12 Business firms and other organizations can plan to innovate by applying either lateral or linear thinking methods, or both. In other words, not all innovation is purely creative. If a firm wishes to innovate a current product, what will likely matter more to that firm is the success of the innovation rather than the level of creativity involved. Drucker summarized the sources of innovation into seven categories, as outlined in Table 4.3 . Firms and individuals can innovate by seeking out and developing changes within markets or by focusing on and cultivating creativity. Firms and individuals should be on the lookout for opportunities to innovate. 13

One innovation that demonstrates several of Drucker’s sources is the use of cashier kiosks in fast-food restaurants. McDonald’s was one of the first to launch these self-serve kiosks. Historically, the company has focused on operational efficiencies (doing more/better with less). In response to changes in the market, changes in demographics, and process need, McDonald’s incorporated self-serve cashier stations into their stores. These kiosks address the need of younger generations to interact more with technology and gives customers faster service in most cases. 15

Another leading expert on innovation, Tony Ulwick , focuses on understanding how the customer will judge or evaluate the quality and value of the product. The product development process should be based on the metrics that customers use to judge products, so that innovation can address those metrics and develop the best product for meeting customers’ needs when it hits the market. This process is very similar to Drucker’s contention that innovation comes as a response to changes within and outside of the market. Ulwick insists that focusing on the customer should begin early in the development process. 16

Disruptive innovation is a process that significantly affects the market by making a product or service more affordable and/or accessible, so that it will be available to a much larger audience. Clay Christensen of Harvard University coined this term in the 1990s to emphasize the process nature of innovation. For Christensen, the innovative component is not the actual product or service, but the process that makes that product more available to a larger population of users. He has since published a good deal on the topic of disruptive innovation, focusing on small players in a market. Christensen theorizes that a disruptive innovation from a smaller company can threaten an existing larger business by offering the market new and improved solutions. The smaller company causes the disruption when it captures some of the market share from the larger organization. 17 , 18 One example of a disruptive innovation is Uber and its impact on the taxicab industry. Uber’s innovative service, which targets customers who might otherwise take a cab, has shaped the industry as whole by offering an alternative that some deem superior to the typical cab ride.

One key to innovation within a given market space is to look for pain points, particularly in existing products that fail to work as well as users expect them to. A pain point is a problem that people have with a product or service that might be addressed by creating a modified version that solves the problem more efficiently. 19 For example, you might be interested in whether a local retail store carries a specific item without actually going there to check. Most retailers now have a feature on their websites that allows you to determine whether the product (and often how many units) is available at a specific store. This eliminates the need to go to the location only to find that they are out of your favorite product. Once a pain point is identified in a firm’s own product or in a competitor’s product, the firm can bring creativity to bear in finding and testing solutions that sidestep or eliminate the pain, making the innovation marketable. This is one example of an incremental innovation , an innovation that modifies an existing product or service. 20

In contrast, a pioneering innovation is one based on a new technology, a new advancement in the field, and/or an advancement in a related field that leads to the development of a new product. 21 Firms offering similar products and services can undertake pioneering innovations, but pioneering the new product requires opening up new market space and taking major risks.

Entrepreneur In Action

Pioneering innovation in the personal care industry.

In his ninth-grade biology class, Benjamin Stern came up with an idea to change the personal care industry. He envisioned personal cleaning products (soap, shampoo, etc.) that would contain no harsh chemicals or sulfates, and would also produce no plastic waste from empty bottles. He developed Nohbo Drops , single-use personal cleansing products with water-soluble packaging. Stern was able to borrow money from family and friends, and use some of his college fund to hire a chemist to develop the product. He then appeared on Shark Tank with his innovation in 2016 and secured the backing of investor Mark Cuban . Stern assembled a research team to perfect the product and obtained a patent ( Figure 4.6 ). The products are now available via the company website.

Is a pioneering innovation an invention? A firm makes a pioneering innovation when it creates a product or service arising from what it has done before. Pokémon GO is a great example of pioneering innovation. Nintendo was struggling to keep pace with other gaming-related companies. The company, in keeping with its core business of video games, came up with a new direction for the gaming industry. Pokémon GO is known worldwide and is one of the most successful mobile games launched. 22 It takes creativity to explore a new direction, but not every pioneering innovation creates a distinctly new product or capability for consumers and clients.

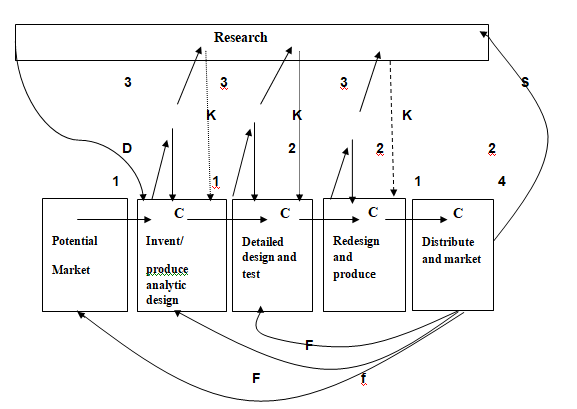

Entrepreneurs in the process of developing an innovation usually examine the current products and services their firm offers, investigate new technologies and techniques being introduced in the marketplace or in related marketplaces, watch research and development in universities and in other companies, and pursue new developments that are likely to fit one of two conditions: an innovation that likely fits an existing market better than other products or services being offered; or an innovation that fits a market that so far has been underserved.

An example of an incremental innovation is the trash receptacle you find at fast-food restaurants. For many years, trash cans in fast-food locations were placed in boxes behind swinging doors. The trash cans did one job well: They hid the garbage from sight. But they created other problems: Often, the swinging doors would get ketchup and other waste on them, surely a pain point. Newer trash receptacles in fast-food restaurants have open fronts or open tops that enable people to dispose of their trash more neatly. The downside for restaurants is that users can see and possibly smell the food waste, but if the restaurants change the trash bags frequently, as is a good practice anyway, this innovation works relatively well. You might not think twice about this everyday example of an innovation when you eat at a fast-food restaurant, but even small improvements can matter a lot, particularly if the market they serve is vast.

An invention is a leap in capability beyond innovation. Some inventions combine several innovations into something new. Invention certainly requires creativity, but it goes beyond coming up with new ideas, combinations of thought, or variations on a theme. Inventors build. Developing something users and customers view as an invention could be important to some entrepreneurs, because when a new product or service is viewed as unique, it can create new markets. True inventiveness is often recognized in the marketplace, and it can help build a valuable reputation and help establish market position if the company can build a future-oriented corporate narrative around the invention. 23

Besides establishing a new market position, a true invention can have a social and cultural impact. At the social level, a new invention can influence the ways institutions work. For example, the invention of desktop computing put accounting and word processing into the hands of nearly every office worker. The ripple effects spread to the school systems that educate and train the corporate workforce. Not long after the spread of desktop computing, workers were expected to draft reports, run financial projections, and make appealing presentations. Specializations or aspects of specialized jobs—such as typist, bookkeeper, corporate copywriter—became necessary for almost everyone headed for corporate work. Colleges and eventually high schools saw software training as essential for students of almost all skill levels. These additional capabilities added profitability and efficiencies, but they also have increased job requirements for the average professional.

Some of the most successful inventions contain a mix of familiarity and innovation that is difficult to achieve. With this mix, the rate of adoption can be accelerated because of the familiarity with the concept or certain aspects of the product or service. As an example, the “videophone” was a concept that began to be explored as early as the late 1800s. AT&T began extensive work on videophones during the 1920s. However, the invention was not adopted because of a lack of familiarity with the idea of seeing someone on a screen and communicating back and forth. Other factors included societal norms, size of the machine, and cost. It wasn’t until the early 2000s that the invention started to take hold in the marketplace. 24 The concept of a black box is that activities are performed in a somewhat mysterious and ambiguous manner, with a serendipitous set of actions connecting that result in a surprisingly beneficial manner. An example is Febreeze, a chemical combination that binds molecules to eliminate odors. From a black box perspective, the chemical engineers did not intend to create this product, but as they were working on creating another product, someone noticed that the product they were working on removed odors, thus inadvertently creating a successful new product marketed as Febreeze.

What Can You Do?

Did henry ford invent the assembly line.

Very few products or procedures are actually brand-new ideas. Most new products are alterations or new applications of existing products, with some type of twist in design, function, portability, or use. Henry Ford is usually credited with inventing the moving assembly line Figure 4.7 (a) in 1913. However, some 800 years before Henry Ford, wooden ships were mass produced in the northern Italian city of Venice in a system that anticipated the modern assembly line.

Various components (ropes, sails, and so on) were prefabricated in different parts of the Venetian Arsenal, a huge, complex construction site along one of Venice’s canals. The parts were then delivered to specific assembly points Figure 4.7 (b) . After each stage of construction, the ships were floated down the canal to the next assembly area, where the next sets of workers and parts were waiting. Moving the ships down the waterway and assembling them in stages increased speed and efficiency to the point that long before the Industrial Revolution, the Arsenal could produce one fully functional and completely equipped ship per day . The system was so successful that it was used from the thirteenth century to about 1800.

Henry Ford did not invent anything new—he only applied the 800-year-old process of building wooden ships by hand along a moving waterway to making metal cars by hand on a moving conveyor ( Figure 4.7 ).

Opportunities to bring new products and processes to market are in front of us every day. The key is having the ability to recognize them and implement them. Likewise, the people you need to help you be successful may be right in front of you on a regular basis. The key is having the ability to recognize who they are and making connections to them. Just as those ships and cars moved down an assembly line until they were ready to be put into service, start thinking about moving down the “who I know” line so that you will eventually have a successful business in place.

The process of invention is difficult to codify because not all inventions or inventors follow the same path. Often the path can take multiple directions, involve many people besides the inventor, and encompass many restarts. Inventors and their teams develop their own processes along with their own products, and the field in which an inventor works will greatly influence the modes and pace of invention. Elon Musk is famous for founding four different billion-dollar companies. The development processes for PayPal , Solar City , SpaceX , and Tesla differed widely; however, Musk does outline a six-step decision-making process ( Figure 4.8 ):

- Ask a question.

- Gather as much evidence as possible about it.

- Develop axioms based on the evidence and try to assign a probability of truth to each one.