An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

A systematic review of substance use and substance use disorder research in Kenya

Florence Jaguga

1 Department of Mental Health, Moi Teaching & Referral Hospital, Eldoret, Kenya

Sarah Kanana Kiburi

2 Department of Mental Health, Mbagathi Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya

Eunice Temet

3 Department of Mental Health & Behavioral Sciences, Moi University School of Medicine, Eldoret, Kenya

Julius Barasa

4 Population Health, Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare, Eldoret, Kenya

Serah Karanja

5 Department of Mental Health, Gilgil Sub-County Hospital, Gilgil, Kenya

Lizz Kinyua

6 Intensive Care Unit, Aga Khan University Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya

Edith Kamaru Kwobah

Associated data.

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting information files.

The burden of substance use in Kenya is significant. The objective of this study was to systematically summarize existing literature on substance use in Kenya, identify research gaps, and provide directions for future research.

This systematic review was conducted in line with the PRISMA guidelines. We conducted a search of 5 bibliographic databases (PubMed, PsychINFO, Web of Science, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Professionals (CINAHL) and Cochrane Library) from inception until 20 August 2020. In addition, we searched all the volumes of the official journal of the National Authority for the Campaign Against Alcohol & Drug Abuse (the African Journal of Alcohol and Drug Abuse). The results of eligible studies have been summarized descriptively and organized by three broad categories including: studies evaluating the epidemiology of substance use, studies evaluating interventions and programs, and qualitative studies exploring various themes on substance use other than interventions. The quality of the included studies was assessed with the Quality Assessment Tool for Studies with Diverse Designs.

Of the 185 studies that were eligible for inclusion, 144 investigated the epidemiology of substance use, 23 qualitatively explored various substance use related themes, and 18 evaluated substance use interventions and programs. Key evidence gaps emerged. Few studies had explored the epidemiology of hallucinogen, prescription medication, ecstasy, injecting drug use, and emerging substance use. Vulnerable populations such as pregnant women, and persons with physical disability had been under-represented within the epidemiological and qualitative work. No intervention study had been conducted among children and adolescents. Most interventions had focused on alcohol to the exclusion of other prevalent substances such as tobacco and cannabis. Little had been done to evaluate digital and population-level interventions.

The results of this systematic review provide important directions for future substance use research in Kenya.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO: CRD42020203717.

Introduction

Globally, substance use is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. In the 2017 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study, substance use disorders (SUDs) were the second leading cause of disability among the mental disorders with 31,052,000 (25%) Years Lived with Disability (YLD) attributed to them [ 1 ]. In 2016, harmful alcohol use resulted in 3 million deaths (5.3% of all deaths) worldwide and 132.6 (5.1%) million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) [ 2 ]. Tobacco use, the leading cause of preventable death, kills more than 8 million people worldwide annually [ 3 ]. Alcohol and tobacco use are leading risk factors for non-communicable diseases for example cardiovascular disease, cancer, and liver disease [ 3 , 4 ]. Even though the prevalence rate of opioid use is small compared to that of tobacco and alcohol use, opioid use disorder contributes to 76% of all deaths from SUDs [ 4 ]. Other psychoactive substances such as cannabis and amphetamines are associated with mental health consequences including increased risk of suicidality, depression, anxiety and psychosis [ 5 , 6 ]. In addition to the effect on health, substance use is associated with significant socio-economic costs arising from its impact on health and criminal justice systems [ 7 ].

Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) bear the burden of substance use. Over 80% of the 1.3 billion tobacco users worldwide live in LMICs [ 3 ]. In 2016, the alcohol-attributable disease burden was highest in LMICs compared to upper-middle-income and high-income countries (HICs) [ 2 ]. In Kenya, a nationwide survey conducted in 2017 reported that over 10% of Kenyans between the ages of 15 to 65 years had a SUD [ 8 ]. In another survey, 20% of primary school children had ever used at least one substance in their lifetime [ 9 ]. Moreover, Kenya has the third highest total DALYs (54,000) from alcohol use disorders (AUD) in Africa [ 4 ] Unfortunately, empirical work on substance use in LMICs is limited [ 10 , 11 ]. In a global mapping of SUD research, majority of the work had been conducted in upper-middle income and HICs (HICs) [ 11 ]. In a study whose aim was to document the existing work on mental health in Botswana, only 7 studies had focused on substance use [ 10 ]. Information upon which policy and interventions could be developed is therefore lacking in low-and-middle income settings.

Since the early 1980s, scholars in Kenya began engaging in research to document the burden and patterns of substance use [ 12 ]. In 2001 the National Authority for the Campaign Against Alcohol and Drug Abuse (NACADA) was established in response to the rising cases of harmful substance use in the country particularly among the youth. The mandate of the Authority was to educate the public on the harms associated with substance use [ 13 ]. In addition to prevention work, NACADA contributes to research by conducting general population prevalence surveys every 5 years and recently launched its journal, the African Journal of Alcohol and Drug Abuse (AJADA) [ 14 ]. The amount of empirical work done on substance use in Kenya has expanded since these early years but has not been systematically summarized. The evidence gaps therefore remain unclear.

In order to guide future research efforts and adequately address the substance use scourge in Kenya, there is need to document the scope and breadth of available scientific literature. The aim of this systematic review is therefore: (i) to describe the characteristics of research studies conducted on substance use and SUD in Kenya; (ii) to assess the methodological quality of the studies; (iii) to identify areas where there is limited research evidence and; (iv) to make recommendations for future research. This paper is in line the Vision 2030 [ 15 ], Kenya’s national development policy framework, which directs that the government implements substance use treatment and prevention projects and programs, and target 3.5 of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) which requires that countries strengthen the treatment and prevention for SUDs [ 16 ].

Materials and methods

Protocol and registration.

In conducting this systematic review we adhered to the recommendations from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [ 17 ]. A 27-item PRISMA checklist is available as an additional file to this protocol ( S1 Checklist ). Our protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO): CRD42020203717.

Search strategy

A search was carried out in five electronic databases on 20 th August 2020: PubMed, PsychINFO, Web of Science, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Professionals (CINAHL) and Cochrane Library. The full search strategy can be found in S1 File and takes the following form: (terms for substance use) and (terms for substance use outcomes of interest) and (terms for region) . The searches spanned the period from inception to date. No filter was applied. A manual search was done in Volumes 1, 2 and 3 (all published volumes by the time of the search) of the recently launched AJADA journal by NACADA, and additional articles identified.

[ 14 , 18 , 19 ].

Study selection

Following the initial search, all articles were loaded onto Mendeley reference manager where initial duplicate screening and removal was done. After duplicate removal, the articles were loaded onto Rayyan, a soft-ware for screening and selecting studies during the conduct of systematic reviews [ 20 ]. The abstract and titles of retrieved articles were independently screened by two authors based on a set of pre-determined eligibility criteria. A second screening of full text articles was also done independently by two authors and resulted in an 88.7% agreement. Disagreements during each stage of the screening were resolved through discussion and consensus.

Inclusion criteria

Since we sought to map existing literature on the subject, our inclusion criteria were broad. We included articles on substance use if (i) the sample or part of the sample was from Kenya, (ii) they were original research articles, (iii) they had a substance use or SUD exposure, (iv) they had a substance use or SUD related outcome such as prevalence, pattern of use, prevention and treatment, and (iv) they were published in English or had an English translation available. We included studies conducted among all age groups and studies that used all designs including quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if: (i) they were cross-national and did not report country specific results (ii) they did not report substance use or SUD as an exposure, and did not have substance use or SUD related outcomes or as part of the outcomes, (iii) they were review articles, dissertations, conference presentations or abstracts, commentaries or editorials, (iv) and the full text articles were not available.

Data extraction

We prepared 3 data extraction forms based on three emerging categories of studies i.e.:

- Studies reporting on the epidemiology of substance use or SUD

- Studies evaluating substance use or SUD interventions and programs

- Studies qualitatively exploring various themes on substance use or SUD (but not evaluating interventions or programs)

The forms were piloted by F.J. and S.K. and adjustments made to the content. Data extraction was then done using the final form by all authors and double checked by F.J. for completeness and accuracy. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion with S.K. and E.T. until consensus was achieved. The following data was extracted for each study category:

- Studies reporting on the epidemiology of substance use or SUD: study design, study population characteristics, study setting, sample size, age and gender distribution, substance(s) assessed, standardized tool or criteria used, main findings (prevalence, risk factors, other key findings).

- Studies evaluating substance use or SUD interventions and programs: study design, study objective, sample size, name of the intervention or program, person delivering intervention, outcomes and measures, and main findings.

- Studies qualitatively exploring various aspects of substance use or SUD other than programs and interventions: study objective, methods of data collection, study setting, study population, age and gender distribution, theoretical framework used, and main findings.

Data synthesis

The results have been summarized descriptively and organized by the three categories above. Within each category, a general description of the study characteristics has been provided followed by a narrative synthesis of findings organized by sub-themes inductively derived from the data. The sub-themes within each category are as follows:

- Studies reporting on the epidemiology of substance use or SUD : Epidemiology of alcohol use, epidemiology of tobacco use, epidemiology of khat use, epidemiology of cannabis use, epidemiology of opioid and cocaine use, epidemiology of other substance use (sedatives, inhalants, hallucinogens, prescription medication, emerging drugs, ecstasy).

- Studies evaluating substance use or SUD interventions and programs: Individual level interventions (Individual-level interventions for harmful alcohol use, individual-level interventions for khat use, individual level intervention for substance use in general); Programs (Methadone programs, needle-syringe programs, tobacco cessation programs, out-patient SUD treatment programs); Population-level interventions : Population-level tobacco interventions, population-level alcohol interventions.

- Studies qualitatively exploring various aspects of substance use or SUD other than programs and interventions : Injecting drug use and heroin use, alcohol use, substance use among youth and adolescents, other topics.

Quality assessment of the studies

Quality assessment was conducted by S.K. using the Quality Assessment Tool for Studies with Diverse Designs (QATSDD) [ 21 ]. F.J. & J.B. double checked the scores for completeness and accuracy. Any disagreements were discussed and resolved by consensus. We had initially planned to use the National Institute of Health (NIH) set of quality assessment tools but due to the diverse nature of study designs, the authors agreed to use the QATSDD tool. The QATSDD is a 16-item tool for both qualitative and quantitative studies. Each item is scored on a 4-point scale (0–3), with a total of 14 criteria for each study design and 16 for studies with mixed methods. Scoring relies on guidance notes provided as well as judgment and expertise from the reviewers. The criteria used are: (i) theoretical framework; (ii) statement of aims or objectives; (iii) description of research setting; (iv) sample size consideration; (v) representative sample of target group (vi) data collection procedure description; (vii) rationale for choice of data collection tool(s); (viii) detailed recruitment data; (ix) statistical assessment of reliability and validity of measurement tools (quantitative only); (x) fit between research question and method of data collection (quantitative only); (xi) fit between research question and format and content data collection (qualitative only); (xii) fit between research question and method of analysis; (xiii) justification of analytical method; (xiv) assessment of reliability of analytical process (qualitative only); (xv) user involvement in design and (xvi) discussion on strengths and limitations[ 21 ]. Scores are awarded for each criterion as follows: 0 = no mention at all; 1 = very brief description; 2 = moderate description; and 3 = complete description. The scores of each criterion are then summed up with a maximum score of 48 for mixed methods studies and 42 for studies using either qualitative only or quantitative only designs. For ease of interpretation, the scores were converted to percentages and classified as low (<50%), medium (50%–80%) or high (>80%) quality of evidence [ 22 ].

Search results

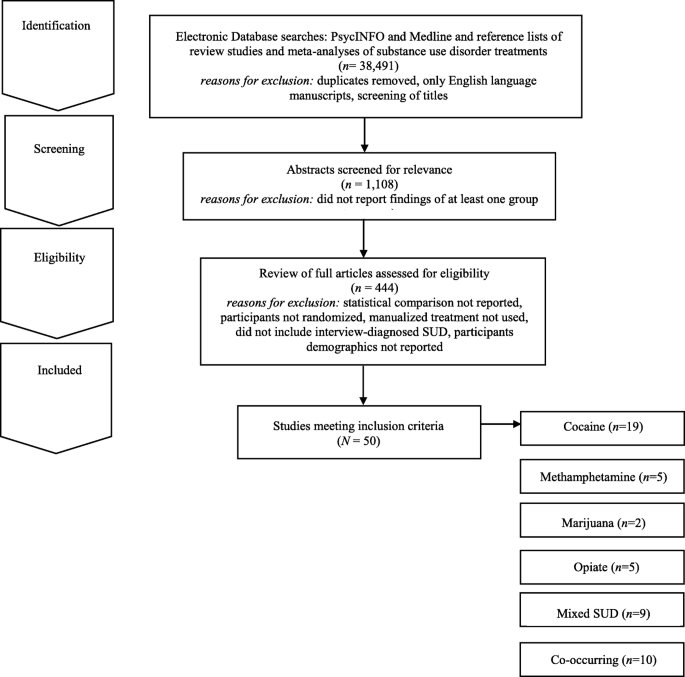

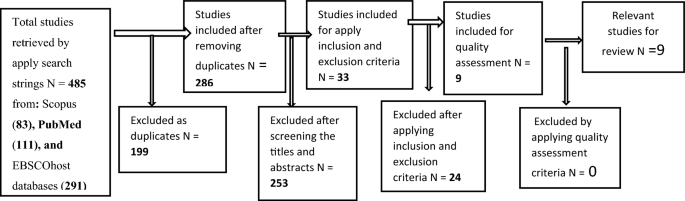

The search from the five electronic databases yielded 1535 results: 950 from PubMed, 173 from PsychINFO, 210 from web of science, 123 from CINAHL and 79 from Cochrane library. Thirteen additional studies were identified through a manual search of the AJADA journals (Volumes 1, 2 and 3). Studies were assessed for duplicates and 1154 articles remained after removal of duplicates. The 1154 studies underwent an initial screening based on abstracts and titles, and 946 articles were excluded. A second screen of full text articles was done for the 208 studies that were potentially eligible for the review. Twenty three studies were excluded as follows: 21 did not meet the eligibility criteria and 2 had duplicated results. A total of 185 studies were found to meet the inclusion criteria and were included in the review ( Fig 1 ).

General characteristics of the studies

Of the 185 studies included in this review, 144 (77.8%) investigated the epidemiology of substance use or SUD, 18 (9.7%) evaluated substance use or SUD interventions and programs, and 23 (12.4%) were qualitative studies exploring perceptions on various substance use or SUD topics other than interventions and programs (Table 4). The studies were published between 1982 and 2020. The number of studies published has gradually increased in number over the years, particularly in the past decade. Fig 2 shows the publication trends for substance use research in Kenya.

Quality assessment

The QATSDD scores ranged from 28.6% [ 23 ] to 92.9% [ 24 ]. Only 14 studies [ 12 , 23 , 25 – 36 ] (all quantitative) had scores of less than 50%. Of these, the main items driving low quality were: no mention of user involvement in study design (n = 14) [ 12 , 23 , 25 – 36 ], no explicit mention of a theoretical framework (n = 10) [ 12 , 23 , 25 – 28 , 30 , 33 , 35 , 36 ] and a lack of a statistical assessment of reliability and validity of measurement tools (n = 10) [ 12 , 23 , 25 , 28 , 30 – 33 , 35 , 36 ] Table 1 .

Studies examining the epidemiology of substance use or SUD

General description of epidemiological studies.

One hundred and forty-four studies examined the prevalence and or risk factors for various substances. The studies were published between 1982 and 2020. The four main study designs used were cross-sectional (n = 126), cohort (n = 5), case-control (n = 10), and mixed methods (n = 2). One study used a combination of the multiplier method, Wisdom of the Crowds (WOTC) method, and a published literature review to document the size of key populations [ 164 ]. The sample size for this category of studies ranged from 42 [ 130 ] to 72292 [ 128 ].

The studies were conducted in diverse settings including the community (n = 72), hospitals (n = 40), institutions of learning (n = 24), streets (n = 5), prisons and courts (n = 3), charitable institutions (n = 1), methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) clinics (n = 1), and in needle-syringe program (NSP) sites (n = 1). Of the studies conducted within the community, 12 were conducted in informal settlements. The study populations were similarly diverse as follows: general population adults & adolescents (n = 39), persons with NCDs (n = 11), primary and secondary school students (n = 15), people who inject drugs (PWID) (n = 11), general patients (n = 5), men who have sex with men (MSM) (n = 8), university and college students (n = 9), commercial sex workers (n = 7), psychiatric patients (n = 6), orphans and street connected children and youth (n = 6), people living with HIV (PLHIV) (n = 6), healthcare workers (n = 3), law offenders (n = 3), military (n = 1), and teachers (n = 1). Only one study was conducted among pregnant women [ 131 ].

Sixty-nine studies (47.6%) used a standardized diagnostic tool to assess for substance use. The Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) (n = 21) and the Alcohol, Smoking & Substance Use Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) questionnaire (n = 10) were the most frequently used tools. Most papers assessed for alcohol ( n = 109) and tobacco use ( n = 80). Other substances assessed included khat (n = 34), opioids (n = 21), sedatives (n = 19), cocaine (n = 19), inhalants (n = 16), cannabis (n = 14), hallucinogens (n = 7), prescription medication (n = 4), emerging drugs (n = 1) and ecstasy (n = 1). Most studies (n = 93) assessed for more than one substance.

Epidemiology of alcohol use

One hundred and nine papers assessed for the prevalence and or risk factors for alcohol use. Using the AUDIT, the 12-month prevalence rate for hazardous alcohol use ranged from 2.9% among adults drawn from the community [ 97 ] to 64.6% among female sex workers (FSW) [ 77 ]. Based on the same tool, the lowest and highest 12-month prevalence rates for harmful alcohol use were both reported among FSWs i.e. 9.3% [ 80 ] and 64.0% [ 174 ] respectively, while the prevalence of alcohol dependence ranged from 8% among FSWs living with HIV [ 203 ] to 33% among MSM who were commercial sex workers [ 144 ]. The highest lifetime prevalence rate for alcohol use was reported by Ndegwa & Waiyaki [ 151 ]. The authors found that 95.7% of undergraduate students had ever used alcohol.

Alcohol use, was associated with several socio-demographic factors including being male [ 50 , 112 , 114 , 140 , 158 , 168 , 182 , 191 ], being unemployed [ 114 ], being self-employed [ 97 ], having a lower socio-economic status (SES) [ 128 ], being single or separated, living in larger households [ 97 ], having a family member struggling with alcohol use, and alcohol being brewed in the home [ 143 ]. Alcohol use was linked to various health factors including glucose intolerance [ 81 ], poor cardiovascular risk factor control [ 111 ], having a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus [ 134 ], hypertension [ 112 , 139 ], default from tuberculosis (TB) treatment [ 148 ], depression [ 113 ], psychological Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) [ 205 ], tobacco use [ 182 , 205 ], and increased risk of esophageal cancer [ 137 , 179 ]. Finally, alcohol use was associated with involvement in Road Traffic Accidents (RTAs) [ 88 ], and having injuries [ 88 , 171 ] and suicidal behavior [ 109 ].

Epidemiology of tobacco use

Eighty papers assessed for the prevalence and risk factors for tobacco use. The lifetime prevalence of tobacco use ranged from 23.5% among healthcare workers (HCWs) [ 140 ] to 84.3% among psychiatric patients [ 110 ]. The highest lifetime prevalence rate for tobacco use was reported by Ndegwa & Waiyaki [ 151 ]. The authors found that 95.7% of undergraduate students had ever used tobacco.

Tobacco use was associated with socio-demographic factors such as being male [ 112 , 140 , 168 ] and living in urban areas [ 163 ]. Several health factors were linked to tobacco use including hypertension [ 112 ], development of oral leukoplakia [ 32 ], pneumonia [ 146 ], increased odds of laryngeal cancer [ 136 ], ischemic stroke [ 100 ] and diabetes mellitus [ 134 ]. In addition, tobacco use was associated with having had an injury in the last 12 months [ 171 ], emotional abuse [ 110 ], and psychological IPV [ 205 ]. Longer duration of smoking was associated with a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus [ 73 ], lower SES [ 128 ], and hypertension [ 98 , 142 ]. Peltzer et al. [ 181 ] reported that early smoking initiation among boys was associated with ever drunk from alcohol use, ever used substances, and ever had sex. Among girls, the authors found that early smoking initiation was associated with higher education, ever drunk from alcohol use, parental or guardian tobacco use, and suicide ideation.

Epidemiology of khat use

The epidemiology of khat use was investigated by 34 studies. The lifetime prevalence rate for khat use ranged from 10.7% among general hospital patients [ 168 ] to 88% among a community sample [ 23 ]. Khat use was associated with being male [ 114 , 168 ]; unemployment [ 114 ]; being employed [ 25 ]; younger age (less than 35 years), higher level of income, comorbid alcohol and tobacco use [ 166 ] and age at first paid sex of less than 20 years among FSWs [ 195 ]. Further, khat use was associated with increased odds of negative health outcomes [ 130 , 146 , 166 , 201 ].

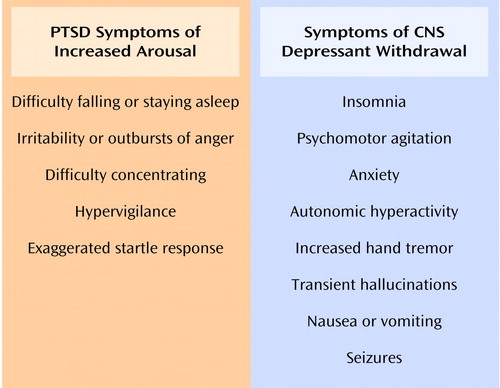

Higher odds of reporting psychotic [ 166 , 201 ], and PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder) symptoms [ 201 ], having thicker oral epithelium [ 130 ], and pneumonia [ 146 ], were reported among khat users compared to non-users.

Epidemiology of cannabis use

Fourteen studies evaluated the prevalence of cannabis use. The lifetime prevalence rate of cannabis use ranged from 21.3% among persons with AUD [ 120 ] to 64.2% among psychiatric patients [ 110 ]. Cannabis use was associated with being male [ 140 , 168 ], and with childhood exposure to physical abuse [ 110 ].

Epidemiology of opioid and cocaine use

Twenty-one studies investigated the prevalence of opioid use. The lifetime prevalence rate of opioid use ranged from 1.1% among PLHIV [ 132 ] to 8.2% among psychiatric patients [ 110 ].

Nineteen studies assessed for the prevalence of cocaine use. The highest reported prevalence rates were 76.2% among PWID use (current use) [ 190 ]; 8.8% among healthcare workers (lifetime use) [ 140 ]; and 6.7% among PLHIV (lifetime use) [ 132 ].

Epidemiology of IDU

One study assessed the prevalence for IDU. Key population size estimates for PWID use was reported as 6107 for Nairobi [ 164 ]. IDU was associated with depression, risky sexual behavior [ 149 ], Hepatitis-C Virus (HCV) infection [ 173 ], and HIV-HCV co-infection [ 68 ].

Epidemiology of other substance use (sedatives, inhalants, hallucinogens and prescription medication, emerging drugs, ecstasy)

The epidemiology of sedative use was investigated by 19 studies, inhalant use by 16 studies, hallucinogen use by 7 studies, prescription medication by 4 studies, and emerging drugs and ecstasy by one study each. The highest lifetime prevalence rate for sedative use was reported as 71.4% among a sample of psychiatric patients [ 28 ], while the highest prevalence rate for inhalant use was 67% among children living in the streets [ 86 ]. The lifetime prevalence rates for hallucinogen use ranged from 1.4% among university students [ 160 ] to 3.7% among psychiatric patients [ 110 ]. The highest prevalence rate for the use of prescription medication was reported as 21.2% among PWID [ 190 ]. One study each reported on the prevalence of emerging drugs [ 122 ] and ecstasy [ 153 ]. The studies were both conducted among adolescents and youth. The authors found the lifetime prevalence rates for the two substances to be 11.8% [ 122 ] and 4.0% [ 153 ] respectively.

Other topics explored by the epidemiology studies

In addition to prevalence and associated factors, the epidemiological studies explored other topics.

Papas et al. [ 176 ] explored the agreement between self-reported alcohol use and the biomarker phosphatidyl ethanol and reported a lack of agreement between self-reported alcohol use and the biomarker phosphatidyl ethanol among PLHIV with AUD.

One study investigated the self-efficacy of primary HCWs for SUD management and reported that self-efficacy for SUD management was lower in those practicing in public facilities and among those perceiving a need for AUD training. Higher self-efficacy was associated with attending to a higher proportion of patients with AUD, and the belief that AUD is manageable in outpatient settings [ 196 ].

Five studies investigated the reasons for substance use. Common reasons for substance use included leisure, stress and peer pressure among psychiatric patients[ 28 ], curiosity, fun, and peer influence among college students [ 123 ], peer influence, idleness, easy access, and curiosity among adults in the community [ 25 ], and peer pressure, to get drunk, to feel better and to feel warm among street children [ 74 ]. Atwoli et al. 2011 [ 72 ] reported that most students were introduced to substances by friends.

Kaai et al. [ 99 ] conducted a study regarding quit intentions for tobacco use and reported that 28% had tried to quit in the past 12 months, 60.9% had never tried to quit, and only 13.8% had ever heard of smoking cessation medication. Intention to quit smoking was associated with being younger, having tried to quit previously, perceiving that quitting smoking was beneficial to health, worrying about future health consequences of smoking, and being low in nicotine dependence. A complete description of the prevalence studies has been provided in Table 2 .

a khat (catha edulis) is a plant with stimulant properties and is listed by WHO as a psychoactive substance. Its use is common in East Africa

b kuber is a type of smokeless tobacco product.

Studies evaluating substance use or SUD programs and interventions

General description of studies evaluating programs and interventions.

A total of eighteen studies evaluated specific interventions or programs for the treatment and prevention of substance use. These were carried out between 2009 and 2020. Eleven studies focused on individual-level interventions, 5 studies evaluated programs, and 2 studies evaluated population-level interventions. The studies used various approaches including randomized control trials (RCT) (n = 7), mixed methods (n = 3), non-concurrent multiple baseline design (n = 1), quasi experimental (n = 1), cross-sectional (n = 2), and qualitative (n = 3). One study employed a combination of qualitative methods and mathematical modeling.

Individual-level interventions

Individual-level interventions for harmful alcohol use . Nine studies evaluated either feasibility, acceptability, and or efficacy for individual-level interventions for harmful alcohol use [ 38 , 40 , 90 , 94 , 127 , 141 , 175 , 178 , 193 ]. All the interventions were tested among adult populations including persons attending a Voluntary Counseling & Testing (VCT) center (38), PLHIV [ 40 , 175 ], and adult males and females drawn from the community [ 94 , 141 ] and FSWs [ 127 , 178 ].

Two studies evaluated a six session CBT intervention for harmful alcohol use among PLHIV. The intervention was reported as feasible, acceptable [ 40 ] and efficacious [ 175 ] in reducing alcohol consumption among PLHIV. The intervention was delivered by trained lay providers.

Giusto et al [ 90 ] evaluated the preliminary efficacy of an intervention aimed at reducing men’s alcohol use and improving family outcomes. The intervention was delivered in 5 sessions by trained lay-providers, and utilized a combination of behavioral activation, motivational interviewing (MI) and gender norm transformative strategies. The intervention showed preliminary efficacy for addressing alcohol use and family related problems.

Five studies evaluated brief interventions that ranged from 1 to 6 sessions and were delivered by primary HCWs, lay providers and specialist mental health professionals [ 38 , 94 , 127 , 178 , 193 ]. The brief interventions were reported as feasible, acceptable [ 38 ], and efficacious in reducing alcohol consumption [ 94 , 127 , 178 , 193 ]. The brief interventions additionally resulted in reductions to IPV, participation in sex work [ 178 ], and risky sexual behavior [ 127 ].

One study evaluated the efficacy of a mobile delivered MI intervention and found that at 1 month, AUDIT-C scores were significantly higher for waiting-list controls compared to those who received the mobile MI [ 94 ].

Moscoe at al. [ 141 ] found no effect of a prize-linked savings account on alcohol, gambling and transactional sex expenditures among men.

Individual-level interventions for khat use . One study utilized a randomized control trial (RCT) approach to evaluate the effect of a three-session brief intervention for khat use on comorbid psychopathology (depression, PTSD, khat induced psychotic symptoms) and everyday functioning. The intervention was delivered by trained college graduates and was found to result in reduced khat use and increased functioning levels, but had no benefit for comorbidity symptoms (compared to assessments only) [ 202 ].

Individual level intervention for any substance use . One study evaluated the efficacy of a four-session psychoeducation intervention using an RCT approach. The study found that the intervention was effective in reducing the severity of symptoms of any substance abuse at 6 months compared to no intervention. The intervention was additionally effective in reducing symptoms for depression, hopelessness, suicidality, and anxiety [ 145 ].

Methadone programs . Two studies utilized qualitative methods to evaluate the perceptions of persons receiving methadone on the benefits of the programs [ 61 , 62 ]. The methadone programs were perceived as having potential to aid in recovery from opioid use and to reduce HIV transmission among PWID [ 61 , 62 ].

Needle-syringe programs (NSPs) . One paper explored the impact of NSPs programs on needle and syringe sharing among PWID. The study reported that the introduction of NSPs led to significant reductions in needle and syringe sharing [ 56 ].

Tobacco cessation programs . One study evaluated HCWs knowledge and practices on tobacco cessation and found that the knowledge and practice on tobacco cessation was inadequate [ 89 ].

Out-patient SUD treatment programs . One paper investigated the impact of community based outpatient SUD treatment services and reported a 42% substance use abstinence rate 0–36 months following treatment termination [ 84 ].

Population-level interventions

Population-level tobacco interventions . One study evaluated the appropriateness and effectiveness of HIC anti-tobacco adverts in the African context and found the adverts to be effective and appropriate [ 183 ].

Population-level alcohol interventions . One paper examined community members’ perspectives on the impact of the government’s public education messages on alcohol abuse and reported that the messages were ineffective and unpersuasive [ 55 ].

A complete description of studies investigating programs and interventions is in Table 3 .

Studies qualitatively exploring various substance use or SUD topics (other than interventions)

General description of qualitative studies.

There were 23 qualitative studies included in our review. The studies were conducted between 2004 and 2020. Data was collected using several approaches including in-depth interviews (IDIs) only (n = 6), focus group discussions (FGDs) only (n = 2), a combination of FGDs and IDIs (n = 10), a combination of observation and individual IDIs (n = 2), a combination of observation, IDIs and FGDs (n = 1), a combination of literature review, observation, IDIs and FGDs (n = 1). One study utilized the participatory research and action approach [ 60 ]. The target populations for the qualitative studies included persons using heroin (n = 3), males and females with IDU (n = 11) adolescents and youth (n = 3), FSWs (n = 2), refugees and Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) (n = 1), and PLHIV (n = 2).

Injecting drug use and heroin use

Thirteen studies explored various themes related to IDU and heroin use with most of them (n = 8) focusing on issues related to women. Three studies explored the drivers of IDU among women and found them to include influence of intimate partners [ 48 , 49 ], stress of unexpected pregnancies [ 49 ], gender inequality, and social suffering [ 67 ]. One study found that IDU among women interfered with utilization of antenatal and maternal and child health services [ 57 ], while another reported that women who inject drugs linked IDU to amenorrhea hence did not perceive the need for contraception [ 51 ].

Mburu et al [ 47 ] explored the social contexts of women who inject drugs and found that these women experienced internal and external stigma of being injecting drug users, and external gender-related stigma of being female injecting drug users. Using a socio-ecological approach, Mburu et al [ 50 ] reported that IDU during sex work was an important HIV risk behavior. In another study, FSWs reported that they used heroin to boost courage to engage in sex work [ 65 ].

Other than IDU and heroin use among women, five studies investigated other themes. One study explored the experiences of injecting heroin users and found that the participants perceived heroin injection as cool [ 42 ]. Guise et al. 2015 [ 44 ] conducted a study to explore transitions from smoking to injecting and reported that transitions from smoking to IDU were experienced as a process of managing resource constraints, or of curiosity, or search for pleasure. One study explored the experiences of persons on MMT as regards integration of MMT with HIV treatment. The study was guided by the material perspective in sociology theory and Annmarie’s Mol’s analysis of logic of care. Persons on MMT preferred that they have choice over whether to seek care for HIV and MMT in a single, or in separate settings.

Alcohol use

Six studies focused on alcohol use. Three studies explored perceptions of service providers and communities on the effects of alcohol use. Alcohol use was perceived as having a negative impact on sexual and reproductive health [ 53 , 54 ] and on socio-economic status [ 43 , 46 ]. One study explored the reasons for alcohol use among PLHIV and found that reasons for alcohol use included stigma and psychological problems, perceived medicinal value, and poverty [ 60 ].

Youth and adolescent substance use

Three studies focused on substance use among youth and adolescents. In one study, the adolescents perceived that substance use contributed to risky sexual behavior including unprotected sex, transactional sex, and multiple partner sex [ 58 ]. The youth identified porn video shows and local brew dens as places where risky sexual encounters between adolescents occurred [ 59 ]. Ssewanyana et al. [ 63 ] utilized the socio-ecological model to explore perceptions of adolescents and stakeholders on the factors predisposing and contributing to substance use. Substance use among adolescents was perceived to be common and to be due to several socio-cultural factors e.g. access to disposable income, idleness, academic pressure, low self-esteem etc.

Other topics

Utilizing the syndemic theory, one study explored how substance use, violence and HIV risk affect PrEP (Pre-exposure prophylaxis) acceptability, access and intervention needs among male and female sex workers. The study found that co-occurring substance use, and violence experienced by sex workers posed important barriers to PrEP access [ 41 ].

A complete description of included qualitative studies is in Table 4 .

This is to our knowledge, the first study to summarize empirical work done on substance use and SUDs in Kenya. More than half (77.8%) of the reviewed studies investigated the area of prevalence and risk factors for substance use. Less common were qualitative studies exploring various themes (12.4%) and studies evaluating interventions and programs (9.7%). The first study was conducted in 1982 and since then the number of publications has gradually risen. Most of the research papers (92.4%) were of moderate to high quality. In comparison to two recent scoping reviews conducted in South Africa and Botswana, more research work has been done on substance use in Kenya. Our study found that 185 papers on substance use among Kenyans had been published by the time of the search while Opondo et al. [ 11 ] and Tran et al. [ 10 ] reported that only 53 and 7 papers focusing on substance use had been published in South Africa (between 1971 and 2017) and in Botswana (between 1983 and 2020) respectively.

Epidemiology of substance use or SUD

Studies investigating the prevalence, and risk factors for substance use dominated the literature. The studies, which were conducted across a broad range of settings and populations, focused on various substances including alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, opioids, cocaine, sedatives, inhalants, hallucinogens, prescription medication, and ecstasy. In addition, a wide range of important health and socio-demographic factors were examined for their association with substance use. Most studies had robust sample sizes and were conducted using diverse designs including cross-sectional, case-control and cohort. The studies showed a significant burden of substance use among both adults and children and adolescents. In addition, substance use increased the odds of negative mental and physical health outcomes consistent with findings documented in global reports [ 2 , 3 ]. These findings highlight the importance of making the treatment and prevention for substance use and SUDs of high priority in Kenya.

- Two main evidence gaps were identified within this category: The prevalence and risk factors for substance use among certain vulnerable populations for whom substance use can have severe negative consequences, had not been investigated. For example, no study had included police officers or persons with physical disability, only one study had its participants as pregnant women [ 113 ], and only 2 studies had been conducted among HCWs [ 140 , 196 ].

- Few studies had explored the epidemiology of hallucinogens, prescription medication, ecstasy, IDU, and emerging substances e.g. synthetic cannabinoids. These substances are a public health threat globally [ 207 , 208 ] yet their use remains poorly documented in Kenya.

Interventions and programs

Given the significant documented burden of substance use and SUDs in Kenya, it was surprising that few studies had focused on developing and testing treatment and prevention interventions for SUDs. A possible reason for this is limited expertise in the area of intervention development and testing. For example, research capacity in implementation science has been shown to be limited in resource-poor settings such as ours [ 209 ].

Of note is that most of the tested interventions had been delivered by lay providers [ 40 , 90 , 175 ] and primary HCWs [ 38 , 127 , 178 ] indicating a recognition of task-shifting as a strategy for filling the mental health human resource gap in Kenya.

Several research gaps were identified within this category.

- Out of the 11 individual-level interventions tested, nine had targeted harmful alcohol use except one which focused on khat [ 202 ] and another that targeted several substances [ 145 ]. No studies had evaluated individual-level interventions targeting tobacco and cannabis use, despite the two being the second and third most commonly used substances in Kenya [ 8 ]. Further, no individual-level interventions had focused on other important SUDs like opioid, sedative and cocaine use disorders.

- Few studies had evaluated the impact of substance use population-level interventions [ 55 , 183 ]. Several cost-effective population-level interventions have been recommended by WHO e.g. mass media education and national toll free quit line services for tobacco use, and brief interventions integrated into all levels of primary care for harmful alcohol use [ 210 ]. Such strategies need to be tested for scaling up in Kenya.

- None of the interventions had been tested among important vulnerable populations for whom local research already shows a significant burden e.g. children and adolescents, the Lesbian Gay Bisexual Transgender & Queer (LGBTQ) community, HCWs, prisoners, refugees, and IDPs. In addition, no interventions had been tested for police officers and pregnant women, and no studies had evaluated interventions to curb workplace substance use.

- Only one study evaluated digital strategies for delivering substance use interventions [ 94 ] yet the feasibility of such strategies has been demonstrated for other mental health disorders in Kenya [ 211 ]. Moreover, the time is ripe for adopting such an approach to substance use treatment given the fact that the country currently has a mobile subscriptions penetration of greater than 90% [ 212 ].

- No studies had evaluated the impact of other interventions such as mindfulness and physical exercise. Meta-analytic evidence suggests that such strategies hold promise for reducing the frequency and severity of substance use and craving [ 213 , 214 ].

Qualitative studies

The qualitative studies focused on a broad range of themes including drivers and impact of substance use, drug markets, patterns of substance use, stigma, and access to treatment. Most of the work however focused on PWID and heroin users. Future qualitative work should explore issues relating to other populations for example persons with other mental disorders, persons with physical disabilities, police officers, and persons using other commonly used substances such as tobacco, khat, and cannabis.

Limitations

The aim of this systematic review was to provide an overview of the existing literature on substance use and SUD research in Kenya. We therefore did not undertake a meta-analysis and detailed synthesis of the findings of studies included in this review. In addition, variability in measurements of substance use outcomes precluded our ability to more comprehensively summarize the study findings. For quality assessment, detailed assessments using design specific tools were not possible given the diverse methodological approaches utilized in the studies. We therefore used a single tool for the quality assessment of all studies. The results of the quality assessment are therefore to be interpreted with caution. Nonetheless this review describes for the first time the breadth of existing literature on substance use and SUDs in Kenya, identifies research gaps, and provides important directions for future research.

The purpose of this systematic review was to map the research that has been undertaken on substance use and SUDs in Kenya. Epidemiological studies dominated the literature and indicated a significant burden of substance use among both adults and adolescents. Our findings indicate that there is a dearth of literature regarding interventions for substance use and we are calling for further research in this area. Specifically, interventions ought to be tested not just for alcohol but for other substances as well, and among important at risk populations. In addition, future research ought to explore the feasibility of delivering substance use interventions using digital means, and the benefit of other interventions such as mindfulness and physical exercise. Future qualitative work should aim at providing in-depth perspectives on substance use among populations excluded from existing literature e.g. police officers, persons using other substances such as tobacco, cannabis and khat, and persons with physical disability.

Supporting information

S1 checklist, abbreviations, funding statement.

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Data Availability

- PLoS One. 2022; 17(6): e0269340.

Decision Letter 0

28 Mar 2022

PONE-D-22-00681A systematic review of substance use and substance use disorder research in KenyaPLOS ONE

Dear Dr. JAGUGA,

Thank you for submitting your manuscript to PLOS ONE. After careful consideration, we feel that it has merit but does not fully meet PLOS ONE’s publication criteria as it currently stands. Therefore, we invite you to submit a revised version of the manuscript that addresses the points raised during the review process.

Please submit your revised manuscript by May 12 2022 11:59PM. If you will need more time than this to complete your revisions, please reply to this message or contact the journal office at gro.solp@enosolp . When you're ready to submit your revision, log on to https://www.editorialmanager.com/pone/ and select the 'Submissions Needing Revision' folder to locate your manuscript file.

Please include the following items when submitting your revised manuscript:

- A rebuttal letter that responds to each point raised by the academic editor and reviewer(s). You should upload this letter as a separate file labeled 'Response to Reviewers'.

- A marked-up copy of your manuscript that highlights changes made to the original version. You should upload this as a separate file labeled 'Revised Manuscript with Track Changes'.

- An unmarked version of your revised paper without tracked changes. You should upload this as a separate file labeled 'Manuscript'.

If you would like to make changes to your financial disclosure, please include your updated statement in your cover letter. Guidelines for resubmitting your figure files are available below the reviewer comments at the end of this letter.

If applicable, we recommend that you deposit your laboratory protocols in protocols.io to enhance the reproducibility of your results. Protocols.io assigns your protocol its own identifier (DOI) so that it can be cited independently in the future. For instructions see: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/submission-guidelines#loc-laboratory-protocols . Additionally, PLOS ONE offers an option for publishing peer-reviewed Lab Protocol articles, which describe protocols hosted on protocols.io. Read more information on sharing protocols at https://plos.org/protocols?utm_medium=editorial-email&utm_source=authorletters&utm_campaign=protocols .

We look forward to receiving your revised manuscript.

Kind regards,

Judith I Tsui

Academic Editor

Journal Requirements:

When submitting your revision, we need you to address these additional requirements.

1. Please ensure that your manuscript meets PLOS ONE's style requirements, including those for file naming. The PLOS ONE style templates can be found at

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/file?id=wjVg/PLOSOne_formatting_sample_main_body.pdf and

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/file?id=ba62/PLOSOne_formatting_sample_title_authors_affiliations.pdf

2. We noticed you have some minor occurrence of overlapping text with the following previous publication(s), which needs to be addressed:

- Tsuei, S.HT., Clair, V., Mutiso, V. et al. Factors Influencing Lay and Professional Health Workers’ Self-efficacy in Identification and Intervention for Alcohol, Tobacco, and Other Substance Use Disorders in Kenya. Int J Ment Health Addiction 15, 766–781 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-017-9775-6

The text that needs to be addressed involves lines 279-283 in your submission.

In your revision ensure you cite all your sources (including your own works), and quote or rephrase any duplicated text outside the methods section. Further consideration is dependent on these concerns being addressed

3. In your Data Availability statement, you have not specified where the minimal data set underlying the results described in your manuscript can be found. PLOS defines a study's minimal data set as the underlying data used to reach the conclusions drawn in the manuscript and any additional data required to replicate the reported study findings in their entirety. All PLOS journals require that the minimal data set be made fully available. For more information about our data policy, please see http://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/data-availability .

Upon re-submitting your revised manuscript, please upload your study’s minimal underlying data set as either Supporting Information files or to a stable, public repository and include the relevant URLs, DOIs, or accession numbers within your revised cover letter. For a list of acceptable repositories, please see http://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/data-availability#loc-recommended-repositories . Any potentially identifying patient information must be fully anonymized.

Important: If there are ethical or legal restrictions to sharing your data publicly, please explain these restrictions in detail. Please see our guidelines for more information on what we consider unacceptable restrictions to publicly sharing data: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/data-availability#loc-unacceptable-data-access-restrictions . Note that it is not acceptable for the authors to be the sole named individuals responsible for ensuring data access.

We will update your Data Availability statement to reflect the information you provide in your cover letter.

[Note: HTML markup is below. Please do not edit.]

Reviewers' comments:

Reviewer's Responses to Questions

Comments to the Author

1. Is the manuscript technically sound, and do the data support the conclusions?

The manuscript must describe a technically sound piece of scientific research with data that supports the conclusions. Experiments must have been conducted rigorously, with appropriate controls, replication, and sample sizes. The conclusions must be drawn appropriately based on the data presented.

Reviewer #1: Yes

Reviewer #2: Partly

2. Has the statistical analysis been performed appropriately and rigorously?

Reviewer #1: N/A

Reviewer #2: N/A

3. Have the authors made all data underlying the findings in their manuscript fully available?

The PLOS Data policy requires authors to make all data underlying the findings described in their manuscript fully available without restriction, with rare exception (please refer to the Data Availability Statement in the manuscript PDF file). The data should be provided as part of the manuscript or its supporting information, or deposited to a public repository. For example, in addition to summary statistics, the data points behind means, medians and variance measures should be available. If there are restrictions on publicly sharing data—e.g. participant privacy or use of data from a third party—those must be specified.

Reviewer #2: Yes

4. Is the manuscript presented in an intelligible fashion and written in standard English?

PLOS ONE does not copyedit accepted manuscripts, so the language in submitted articles must be clear, correct, and unambiguous. Any typographical or grammatical errors should be corrected at revision, so please note any specific errors here.

Reviewer #1: No

5. Review Comments to the Author

Please use the space provided to explain your answers to the questions above. You may also include additional comments for the author, including concerns about dual publication, research ethics, or publication ethics. (Please upload your review as an attachment if it exceeds 20,000 characters)

Reviewer #1: This manuscript adds value in an under-research area by summarizing main learnings from substance use and substance use disorder research in Kenya. Major revisions are needed though for the article to be presented as a scientifically- acceptable piece. These revision include punctuation, grammar errors (eg: inappropriate use of upper case letter on line 84- 86), and overall flow of some sentences such as line 31, line 39, line 50, line 58, line 69, line 83, line 87- 91, line 104, line 172, line 175 to list a few.

In addition to these revision, below are proposed consideration:

- In the abstract, please specify the start date used in the search strategy.

- Line 53- tobacco kills 8million people where? Worldwide? On a specific continent? Please specify

-Line 57- you mentioned one consequence so far ie death which others are you referring to here?

- Line 104- inception of what?

-Line 111 who checked the duplicates? Was the software used for this or did the authors do it? It's a bit unclear

-Line 124-125: Were mixed methods studies included as well? The way this is phrased it sounds like "all designs" refers more to qualitative and quantitative studies

-Avoid over using "/" in sentences. If need be list item a "or" b throughout the manuscript. Eg: substance use or SUDs

-Line 182- 183- did you mean that 13 additional studies were identified? Please consider reviewing and rephrasing your sentences to improve clarity

-Line 185- Is "These" referring to the studies? If yes, can you be a bit more explicit?

-Line 238- are you referring to MSM who are commercial sex workers? Please use appropriate languages throughout the manuscript

- For the result presentation, it might be helpful to have as part of the main manuscript (not supplemental information) a summary table of the final literature reviewed including information on the title of the article, authors, methods, findings and gap from the articles that were included in the review instead of having long references throughout the result section.

- Line 313 Lay healthcare providers might be more appropriate same for line 314 for primary healthcare workers not primary care workers

-Line 331-332 that last sentence seems incomplete, please consider reviewing it

-Line 371- 372- What are estimates then on what has been done elsewhere in SSA? Is this conclusion based mainly on the 2 scoping work from SA and Bostwana? How about other SSA countries including countries neighboring Kenya like Uganda, Tanzania, etc?

How do you define a lot?

-Line 392- Emerging substances like which ones?

- Line 404- Was the study specifically assessing feasibility? If that was not the case, making such claim is misleading

Reviewer #2: This systematic review highlights several gaps in licit and illicit substance use (SU) and substance use disorder (SUD) literature within Kenya, with the goal of summarizing research within three broad domains: (1) epidemiologic studies, (2) intervention and/or programs and (3) qualitative studies. The authors apply sound methods, with attention to details around decision-making processes when including articles in their review. The attention to target study populations (e.g., community, hospitals, prisons, etc.) is extremely valuable and calls for additional studies within specific populations. In addition, the authors make the case that their review is needed in order to address Kenya’s Vision 2030 and moves towards accomplishing SDG’s. I commend the authors for completing this large undertaking and offer feedback to strengthen and improve their paper.

Major Edits

• There is an absolute need for SU and SUD systematic review; however, this paper may have limited applications in its current state. In the introduction, the authors state this paper will “guide future research efforts”; however, most SUD researchers work with one substance or one category of substances. It would be helpful within the key findings sections to expand on SU categories, which are discussed briefly in the introduction (e.g., tobacco, alcohol, opioids, cannabis, and stimulants.) Another option may be to reformat the paragraphs according to SU categories and discuss the current epidemiologic, interventions/programs, and qualitative studies.

• In your criteria, you do not mention whether you included studies conducted out of methadone clinics or harm reduction sites (i.e., drop-in centres, NSPs), specifically. However, when I look over the publications, several were conducted within these sites. Please clarify whether these terms were part of your search categories and include them on Page 11, lines 215-217.

• Throughout the descriptions and key findings sections, there should be more syntheses of the data instead of frequencies, which are already conveyed in your tables. For example, under the epidemiology section of SU/SUD, you say that 47% of the studies used evidence-based diagnostic tools, but this should be followed by the key findings of those studies (i.e., X-X% of participants indicated hazardous or harmful alcohol consumption, and X-X% of participants indicated alcohol dependence.) This is just one example, but all of the key finding’s sections should provide more data syntheses.

• As it stands, the key findings and other findings sections are a little difficult to follow and are heavily focused on alcohol and tobacco use. For example, in the epidemiologic key findings section the paragraphs are organized as follows: (1) youth and substance use, (2) adults and tobacco use, (3) adults and alcohol use, and (4) two case control studies. Again, this may have a better flow if the authors organized the key findings by SU categories (e.g., tobacco, alcohol, opioids, cannabis, and stimulants.) By structuring the paragraphs by SU categories, the reader is able to quickly decipher where there are gaps in the literature. Alternatively, the authors may want to consider narrowing the scope of their paper by solely focusing on alcohol and tobacco use, which seem to be the main focus throughout the paper.

• In the qualitative study key findings section, most of the studies apply frameworks and/or theories to their analysis (e.g., stages of change, risk environment framework), which should be synthesized and included as a column in Additional File 5/Qualitative Studies.

Minor Edits

• Please review the PLOS ONE Guidelines on formatting references and edit references.

• Page 11 (line 220) “People with injecting drug use” should be “people (or persons) who inject drugs.”

• Page 11 (line 221) “Men who have Sex with Men” should not contain capital letters.

• Page 11 (lines 218-225) This section does not sum up to the total studies in the epidemiology section n=144.

• Page 11 (line 210-213) Please be consistent in how you mention the study designs with corresponding references. This was completed in the interventions and programs section, but not for the epidemiological studies.

• Page 15 (lines 299-303) Conversely, please indicate in the programs and intervention section, how may studies were included in each of the study designs.

• Page 12 (line 229) typo, please change to “opioids (n=21)”

• In the findings section, please define “hospital,” and whether this includes methadone clinics.

• Page 20 (line 398) “Substance use” should be “substance use disorder.”

• Page 21 (line 423-424) “Mental disorders” should be “mental health disorders.”

• Additional File 3/Epidemiological Studies: The SU category should not include how people consume their drugs (“injection drugs”), which is only seen a few times, but what drugs categories were examined. Please be more specific than “illicit drugs.”

• Additional File 4/Interventions and Program: Please review the sample sizes for each study, particularly for those with “not reported.”

6. PLOS authors have the option to publish the peer review history of their article ( what does this mean? ). If published, this will include your full peer review and any attached files.

If you choose “no”, your identity will remain anonymous but your review may still be made public.

Do you want your identity to be public for this peer review? For information about this choice, including consent withdrawal, please see our Privacy Policy .

Reviewer #2: No

[NOTE: If reviewer comments were submitted as an attachment file, they will be attached to this email and accessible via the submission site. Please log into your account, locate the manuscript record, and check for the action link "View Attachments". If this link does not appear, there are no attachment files.]

While revising your submission, please upload your figure files to the Preflight Analysis and Conversion Engine (PACE) digital diagnostic tool, https://pacev2.apexcovantage.com/ . PACE helps ensure that figures meet PLOS requirements. To use PACE, you must first register as a user. Registration is free. Then, login and navigate to the UPLOAD tab, where you will find detailed instructions on how to use the tool. If you encounter any issues or have any questions when using PACE, please email PLOS at gro.solp@serugif . Please note that Supporting Information files do not need this step.

Submitted filename: PONE-D-22-00681.pdf

Author response to Decision Letter 0

12 May 2022

Reviewer #1: This manuscript adds value in an under-research area by summarizing main learnings from substance use and substance use disorder research in Kenya. Major revisions are needed though for the article to be presented as a scientifically- acceptable piece. These revision include punctuation, grammar errors (eg: inappropriate use of upper case letter on line 84- 86), and overall flow of some sentences such as line 31, line 39, line 50, line 58, line 69, line 83, line 87- 91, line 104, line 172, line 175 to list a few.

We thank the reviewer for this comment. We have thoroughly proof read the paper and made corrections to grammar and punctuation.

We have specified that the search was conducted from inception (line 27).

We have clarified that it is worldwide (line 58)

The paragraph has been revised to include health consequences of alcohol, tobacco and other substances (line 58-63)

Inception means from the earliest available study. This term is commonly used in systematic review searches when no date limits have been set

The Mendeley Reference manager was used to identify and remove duplicates. This has been clarified on line 116-117.

Yes, we included studies with qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods designs. This has now been clarified (line 133).

This has been corrected throughout the manuscript

The sentence has been reviewed to improve clarity (line 208)

We have reworded the sentence to make it more explicit (line 210)

The authors are referring to MSM who were commercial sex workers. We have corrected this (line 273).

We have included the tables within the main manuscript (line 367, 439, 504)

This has been corrected line 388, 391, 395, 551, 552

This sentence has been revised (line 428-430)

We have reworded the paragraph to show that we are comparing our findings with available scoping reviews (line 513-520)

How do you define a lot? We have revised this sentence and used the word “more…” (line 515)

An example has been given (line 541)

This line has been deleted (line 554).

Reviewer #2: This systematic review highlights several gaps in licit and illicit substance use (SU) and substance use disorder (SUD) literature within Kenya, with the goal of summarizing research within three broad domains: (1) epidemiologic studies, (2) intervention and/or programs and (3) qualitative studies. The authors apply sound methods, with attention to details around decision-making processes when including articles in their review. The attention to target study populations (e.g., community, hospitals, prisons, etc.) is extremely valuable and calls for additional studies within specific populations. In addition, the authors make the case that their review is needed in order to address Kenya’s Vision 2030 and moves towards accomplishing SDG’s. I commend the authors for completing this large undertaking and offer feedback to strengthen and improve their paper.

We thank the reviewer for their comments.

We acknowledge this comment. We have organized the key findings sections by substance use categories and expanded on the findings (line 162, 266-366, 373-439, 446-503).

NSP sites has been included in the general characteristics of epidemiological studies (line 248)

• We have now provided more synthesis of data in the results section

(line 266-366, 373-439, 446-503).

We have incorporated the theoretical frameworks into the results section (line 468,478, 492, 499), and added a column presenting information on theoretical frameworks to the table 4 (line 505).

The references have been edited in line with PLOS one guidelines

This has been corrected (line 251)

This has been corrected (line 252)

Yes. This is true because some populations overlapped e.g. some studies were conducted among general population adults with NCDs.

We have now deleted references in the general description section for the intervention studies (line 375-378) and qualitative studies (448-457) to ensure uniformity

This has been indicated. Line 386-389

This has been corrected. Line 261

We have separated out studies done within hospitals and those done within methadone clinics (line 247; Kisilu et al. 2019 on table 2 line 367)

This has been corrected. Line 551

This has been corrected. Line 578

The studies described the substances as just IDU and illicit substances, and did not provide descriptions of the specific substances assessed for. We have included the phrase ‘not specified’ next to the term illicit drugs and IDU for clarity. (Table 2 line 367)

These were reviewed and appropriate sample sizes reported (table 3 line 443)

Editors’ comments

We have addressed this (line 349-354)

About data availability. All analyzed data has been included in the main manuscript and in the supporting information files 1 and 2. (line 1264)

Decision Letter 1

19 May 2022

PONE-D-22-00681R1

We’re pleased to inform you that your manuscript has been judged scientifically suitable for publication and will be formally accepted for publication once it meets all outstanding technical requirements.

Within one week, you’ll receive an e-mail detailing the required amendments. When these have been addressed, you’ll receive a formal acceptance letter and your manuscript will be scheduled for publication.

An invoice for payment will follow shortly after the formal acceptance. To ensure an efficient process, please log into Editorial Manager at http://www.editorialmanager.com/pone/ , click the 'Update My Information' link at the top of the page, and double check that your user information is up-to-date. If you have any billing related questions, please contact our Author Billing department directly at gro.solp@gnillibrohtua .

If your institution or institutions have a press office, please notify them about your upcoming paper to help maximize its impact. If they’ll be preparing press materials, please inform our press team as soon as possible -- no later than 48 hours after receiving the formal acceptance. Your manuscript will remain under strict press embargo until 2 pm Eastern Time on the date of publication. For more information, please contact gro.solp@sserpeno .

Additional Editor Comments (optional):

Acceptance letter

26 May 2022

Dear Dr. Jaguga:

I'm pleased to inform you that your manuscript has been deemed suitable for publication in PLOS ONE. Congratulations! Your manuscript is now with our production department.

If your institution or institutions have a press office, please let them know about your upcoming paper now to help maximize its impact. If they'll be preparing press materials, please inform our press team within the next 48 hours. Your manuscript will remain under strict press embargo until 2 pm Eastern Time on the date of publication. For more information please contact gro.solp@sserpeno .

If we can help with anything else, please email us at gro.solp@enosolp .

Thank you for submitting your work to PLOS ONE and supporting open access.

PLOS ONE Editorial Office Staff

on behalf of

Dr. Judith I Tsui

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

A systematic review of substance use and substance use disorder research in Kenya

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Mental Health, Moi Teaching & Referral Hospital, Eldoret, Kenya

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Mental Health, Mbagathi Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya

Roles Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Mental Health & Behavioral Sciences, Moi University School of Medicine, Eldoret, Kenya

Affiliation Population Health, Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare, Eldoret, Kenya

Roles Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Mental Health, Gilgil Sub-County Hospital, Gilgil, Kenya

Affiliation Intensive Care Unit, Aga Khan University Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya

Roles Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

- Florence Jaguga,

- Sarah Kanana Kiburi,

- Eunice Temet,

- Julius Barasa,

- Serah Karanja,

- Lizz Kinyua,

- Edith Kamaru Kwobah

- Published: June 9, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269340

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

The burden of substance use in Kenya is significant. The objective of this study was to systematically summarize existing literature on substance use in Kenya, identify research gaps, and provide directions for future research.

This systematic review was conducted in line with the PRISMA guidelines. We conducted a search of 5 bibliographic databases (PubMed, PsychINFO, Web of Science, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Professionals (CINAHL) and Cochrane Library) from inception until 20 August 2020. In addition, we searched all the volumes of the official journal of the National Authority for the Campaign Against Alcohol & Drug Abuse (the African Journal of Alcohol and Drug Abuse). The results of eligible studies have been summarized descriptively and organized by three broad categories including: studies evaluating the epidemiology of substance use, studies evaluating interventions and programs, and qualitative studies exploring various themes on substance use other than interventions. The quality of the included studies was assessed with the Quality Assessment Tool for Studies with Diverse Designs.

Of the 185 studies that were eligible for inclusion, 144 investigated the epidemiology of substance use, 23 qualitatively explored various substance use related themes, and 18 evaluated substance use interventions and programs. Key evidence gaps emerged. Few studies had explored the epidemiology of hallucinogen, prescription medication, ecstasy, injecting drug use, and emerging substance use. Vulnerable populations such as pregnant women, and persons with physical disability had been under-represented within the epidemiological and qualitative work. No intervention study had been conducted among children and adolescents. Most interventions had focused on alcohol to the exclusion of other prevalent substances such as tobacco and cannabis. Little had been done to evaluate digital and population-level interventions.

The results of this systematic review provide important directions for future substance use research in Kenya.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO: CRD42020203717.

Citation: Jaguga F, Kiburi SK, Temet E, Barasa J, Karanja S, Kinyua L, et al. (2022) A systematic review of substance use and substance use disorder research in Kenya. PLoS ONE 17(6): e0269340. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269340

Editor: Judith I. Tsui, University of Washington, UNITED STATES

Received: January 8, 2022; Accepted: May 18, 2022; Published: June 9, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Jaguga et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting information files.

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Abbreviations: ASI, Addiction Severity Index; ASSIST, Alcohol Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test; AUD, Alcohol Use Disorder; AUDIT, Alcohol Use Identification Test; AUDIT-C, Alcohol Use Identification Test–Concise; BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BHS, Behavioral Health Screen; BMI, Body Mass index; BSIS, Beck Suicidal Intent Scale; CAD, Coronary Artery Disease; CAGE, Cut, Annoyed, Guilty, Eye-opener; CIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; CINAHL, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Professionals; CRAFFT, Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, Trouble; DAST, Drug Abuse Screening Test; DSM-III, Diagnostic & Statistical Manual Third Edition; DSM-III R, Diagnostic & Statistical Manual Third Edition Revised; DSM-IV, Diagnostic & Statistical Manual Fourth Edition; DSM-V, Diagnostic & Statistical Manual Fifth Edition; DUSI-R, Drug Use Screening Inventory—Revised; FGD, Focus Group Discussion; FSW, Female Sex Workers; GSHS, Global School-based Health Survey; HCV, Hepatitis C Virus; HCW, Healthcare worker; HIC, High Income Country; HIV, Human Immunodeficiency Virus; ICD, International Classification of Disease; IDI, In-depth Interviews; IDP, Internally Displaced Persons; IPV, Intimate Partner Violence; KIIs, Key Informant Interviews; K-SADS, Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders; LGBTQ, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer; LMIC, Low and Middle Income Country; MAST, Michigan Alcohol Screening Test; MI, Motivational Interviewing; MINI, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; MMT, Methadone Maintenance Therapy; MPBI, Multiple Problem Behavior Inventory; MSM, Men who have Sex with Men; MSME, Men who have Sex with Men Exclusively; MSMW, Men who have Sex with Men & Women; NIH, National Institute of Health; NSP, Needle Syringe Program; OST, Opioid Substitution Therapy; PLHIV, People Living with HIV; PrEP, Pre-exposure Prophylaxis; PTSD, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder; PWID, People Who Inject Drugs; QATSDD, Quality Assessment Tool for Studies with Diverse Designs; RCT, Randomized controlled trial; RTAs, Road Traffic Accidents; SCID, Structured Clinical interview for DSM; SES, Socio-economic Status; SSA, Sub-Saharan Africa; TB, Tuberculosis; UNODC, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; VCT, Voluntary Counseling & Testing; WOTC, Wisdom of the Crowds

Introduction

Globally, substance use is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. In the 2017 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study, substance use disorders (SUDs) were the second leading cause of disability among the mental disorders with 31,052,000 (25%) Years Lived with Disability (YLD) attributed to them [ 1 ]. In 2016, harmful alcohol use resulted in 3 million deaths (5.3% of all deaths) worldwide and 132.6 (5.1%) million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) [ 2 ]. Tobacco use, the leading cause of preventable death, kills more than 8 million people worldwide annually [ 3 ]. Alcohol and tobacco use are leading risk factors for non-communicable diseases for example cardiovascular disease, cancer, and liver disease [ 3 , 4 ]. Even though the prevalence rate of opioid use is small compared to that of tobacco and alcohol use, opioid use disorder contributes to 76% of all deaths from SUDs [ 4 ]. Other psychoactive substances such as cannabis and amphetamines are associated with mental health consequences including increased risk of suicidality, depression, anxiety and psychosis [ 5 , 6 ]. In addition to the effect on health, substance use is associated with significant socio-economic costs arising from its impact on health and criminal justice systems [ 7 ].