10 Grounded Theory Examples (Qualitative Research Method)

Grounded theory is a qualitative research method that involves the construction of theory from data rather than testing theories through data (Birks & Mills, 2015).

In other words, a grounded theory analysis doesn’t start with a hypothesis or theoretical framework, but instead generates a theory during the data analysis process .

This method has garnered a notable amount of attention since its inception in the 1960s by Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss (Corbin & Strauss, 2015).

Grounded Theory Definition and Overview

A central feature of grounded theory is the continuous interplay between data collection and analysis (Bringer, Johnston, & Brackenridge, 2016).

Grounded theorists start with the data, coding and considering each piece of collected information (for instance, behaviors collected during a psychological study).

As more information is collected, the researcher can reflect upon the data in an ongoing cycle where data informs an ever-growing and evolving theory (Mills, Bonner & Francis, 2017).

As such, the researcher isn’t tied to testing a hypothesis, but instead, can allow surprising and intriguing insights to emerge from the data itself.

Applications of grounded theory are widespread within the field of social sciences . The method has been utilized to provide insight into complex social phenomena such as nursing, education, and business management (Atkinson, 2015).

Grounded theory offers a sound methodology to unearth the complexities of social phenomena that aren’t well-understood in existing theories (McGhee, Marland & Atkinson, 2017).

While the methods of grounded theory can be labor-intensive and time-consuming, the rich, robust theories this approach produces make it a valuable tool in many researchers’ repertoires.

Real-Life Grounded Theory Examples

Title: A grounded theory analysis of older adults and information technology

Citation: Weatherall, J. W. A. (2000). A grounded theory analysis of older adults and information technology. Educational Gerontology , 26 (4), 371-386.

Description: This study employed a grounded theory approach to investigate older adults’ use of information technology (IT). Six participants from a senior senior were interviewed about their experiences and opinions regarding computer technology. Consistent with a grounded theory angle, there was no hypothesis to be tested. Rather, themes emerged out of the analysis process. From this, the findings revealed that the participants recognized the importance of IT in modern life, which motivated them to explore its potential. Positive attitudes towards IT were developed and reinforced through direct experience and personal ownership of technology.

Title: A taxonomy of dignity: a grounded theory study

Citation: Jacobson, N. (2009). A taxonomy of dignity: a grounded theory study. BMC International health and human rights , 9 (1), 1-9.

Description: This study aims to develop a taxonomy of dignity by letting the data create the taxonomic categories, rather than imposing the categories upon the analysis. The theory emerged from the textual and thematic analysis of 64 interviews conducted with individuals marginalized by health or social status , as well as those providing services to such populations and professionals working in health and human rights. This approach identified two main forms of dignity that emerged out of the data: “ human dignity ” and “social dignity”.

Title: A grounded theory of the development of noble youth purpose

Citation: Bronk, K. C. (2012). A grounded theory of the development of noble youth purpose. Journal of Adolescent Research , 27 (1), 78-109.

Description: This study explores the development of noble youth purpose over time using a grounded theory approach. Something notable about this study was that it returned to collect additional data two additional times, demonstrating how grounded theory can be an interactive process. The researchers conducted three waves of interviews with nine adolescents who demonstrated strong commitments to various noble purposes. The findings revealed that commitments grew slowly but steadily in response to positive feedback, with mentors and like-minded peers playing a crucial role in supporting noble purposes.

Title: A grounded theory of the flow experiences of Web users

Citation: Pace, S. (2004). A grounded theory of the flow experiences of Web users. International journal of human-computer studies , 60 (3), 327-363.

Description: This study attempted to understand the flow experiences of web users engaged in information-seeking activities, systematically gathering and analyzing data from semi-structured in-depth interviews with web users. By avoiding preconceptions and reviewing the literature only after the theory had emerged, the study aimed to develop a theory based on the data rather than testing preconceived ideas. The study identified key elements of flow experiences, such as the balance between challenges and skills, clear goals and feedback, concentration, a sense of control, a distorted sense of time, and the autotelic experience.

Title: Victimising of school bullying: a grounded theory

Citation: Thornberg, R., Halldin, K., Bolmsjö, N., & Petersson, A. (2013). Victimising of school bullying: A grounded theory. Research Papers in Education , 28 (3), 309-329.

Description: This study aimed to investigate the experiences of individuals who had been victims of school bullying and understand the effects of these experiences, using a grounded theory approach. Through iterative coding of interviews, the researchers identify themes from the data without a pre-conceived idea or hypothesis that they aim to test. The open-minded coding of the data led to the identification of a four-phase process in victimizing: initial attacks, double victimizing, bullying exit, and after-effects of bullying. The study highlighted the social processes involved in victimizing, including external victimizing through stigmatization and social exclusion, as well as internal victimizing through self-isolation, self-doubt, and lingering psychosocial issues.

Hypothetical Grounded Theory Examples

Suggested Title: “Understanding Interprofessional Collaboration in Emergency Medical Services”

Suggested Data Analysis Method: Coding and constant comparative analysis

How to Do It: This hypothetical study might begin with conducting in-depth interviews and field observations within several emergency medical teams to collect detailed narratives and behaviors. Multiple rounds of coding and categorizing would be carried out on this raw data, consistently comparing new information with existing categories. As the categories saturate, relationships among them would be identified, with these relationships forming the basis of a new theory bettering our understanding of collaboration in emergency settings. This iterative process of data collection, analysis, and theory development, continually refined based on fresh insights, upholds the essence of a grounded theory approach.

Suggested Title: “The Role of Social Media in Political Engagement Among Young Adults”

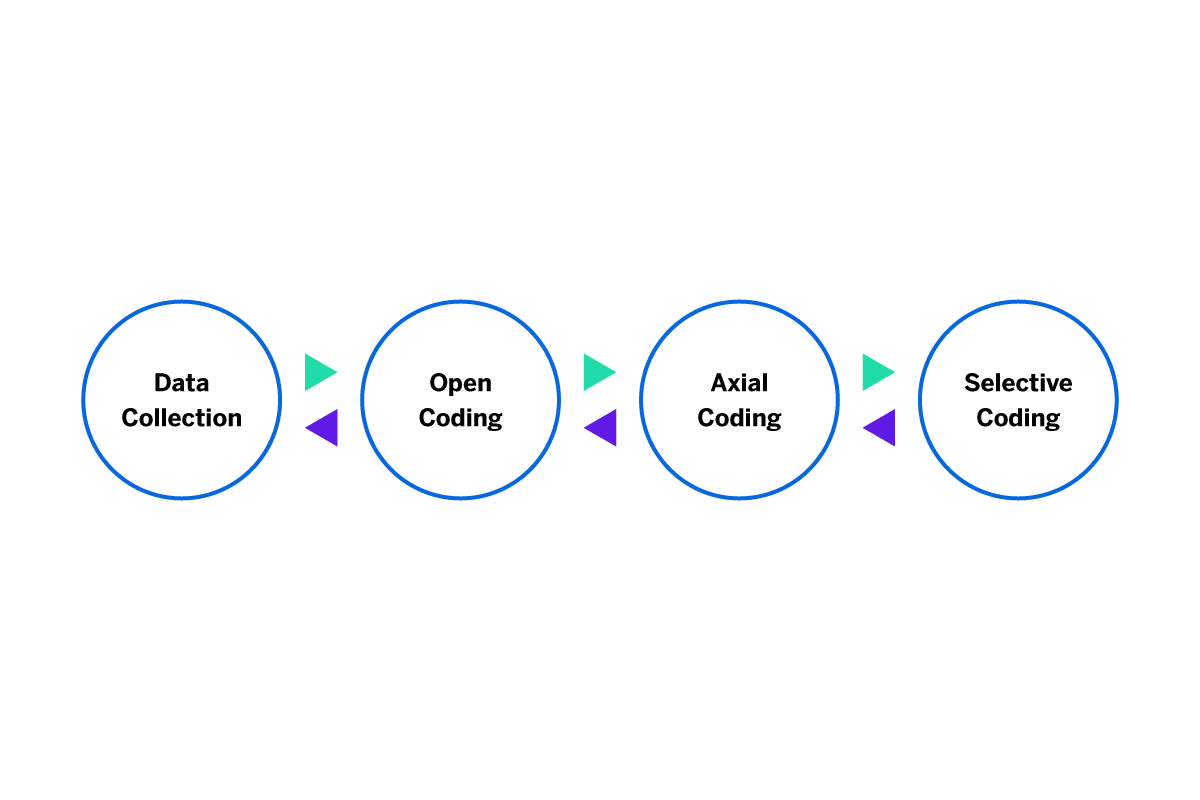

Suggested Data Analysis Method: Open, axial, and selective coding

Explanation: The study would start by collecting interaction data on various social media platforms, focusing on political discussions engaged in by young adults. Through open, axial, and selective coding, the data would be broken down, compared, and conceptualized. New insights and patterns would gradually form the basis of a theory explaining the role of social media in shaping political engagement, with continuous refinement informed by the gathered data. This process embodies the recursive essence of the grounded theory approach.

Suggested Title: “Transforming Workplace Cultures: An Exploration of Remote Work Trends”

Suggested Data Analysis Method: Constant comparative analysis

Explanation: The theoretical study could leverage survey data and in-depth interviews of employees and bosses engaging in remote work to understand the shifts in workplace culture. Coding and constant comparative analysis would enable the identification of core categories and relationships among them. Sustainability and resilience through remote ways of working would be emergent themes. This constant back-and-forth interplay between data collection, analysis, and theory formation aligns strongly with a grounded theory approach.

Suggested Title: “Persistence Amidst Challenges: A Grounded Theory Approach to Understanding Resilience in Urban Educators”

Suggested Data Analysis Method: Iterative Coding

How to Do It: This study would involve collecting data via interviews from educators in urban school systems. Through iterative coding, data would be constantly analyzed, compared, and categorized to derive meaningful theories about resilience. The researcher would constantly return to the data, refining the developing theory with every successive interaction. This procedure organically incorporates the grounded theory approach’s characteristic iterative nature.

Suggested Title: “Coping Strategies of Patients with Chronic Pain: A Grounded Theory Study”

Suggested Data Analysis Method: Line-by-line inductive coding

How to Do It: The study might initiate with in-depth interviews of patients who’ve experienced chronic pain. Line-by-line coding, followed by memoing, helps to immerse oneself in the data, utilizing a grounded theory approach to map out the relationships between categories and their properties. New rounds of interviews would supplement and refine the emergent theory further. The subsequent theory would then be a detailed, data-grounded exploration of how patients cope with chronic pain.

Grounded theory is an innovative way to gather qualitative data that can help introduce new thoughts, theories, and ideas into academic literature. While it has its strength in allowing the “data to do the talking”, it also has some key limitations – namely, often, it leads to results that have already been found in the academic literature. Studies that try to build upon current knowledge by testing new hypotheses are, in general, more laser-focused on ensuring we push current knowledge forward. Nevertheless, a grounded theory approach is very useful in many circumstances, revealing important new information that may not be generated through other approaches. So, overall, this methodology has great value for qualitative researchers, and can be extremely useful, especially when exploring specific case study projects . I also find it to synthesize well with action research projects .

Atkinson, P. (2015). Grounded theory and the constant comparative method: Valid qualitative research strategies for educators. Journal of Emerging Trends in Educational Research and Policy Studies, 6 (1), 83-86.

Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2015). Grounded theory: A practical guide . London: Sage.

Bringer, J. D., Johnston, L. H., & Brackenridge, C. H. (2016). Using computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software to develop a grounded theory project. Field Methods, 18 (3), 245-266.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory . Sage publications.

McGhee, G., Marland, G. R., & Atkinson, J. (2017). Grounded theory research: Literature reviewing and reflexivity. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 29 (3), 654-663.

Mills, J., Bonner, A., & Francis, K. (2017). Adopting a Constructivist Approach to Grounded Theory: Implications for Research Design. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 13 (2), 81-89.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 5 Top Tips for Succeeding at University

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 50 Durable Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 100 Consumer Goods Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 30 Globalization Pros and Cons

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Grounded Theory – Methods, Examples and Guide

Grounded Theory – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

Grounded Theory

Definition:

Grounded Theory is a qualitative research methodology that aims to generate theories based on data that are grounded in the empirical reality of the research context. The method involves a systematic process of data collection, coding, categorization, and analysis to identify patterns and relationships in the data.

The ultimate goal is to develop a theory that explains the phenomenon being studied, which is based on the data collected and analyzed rather than on preconceived notions or hypotheses. The resulting theory should be able to explain the phenomenon in a way that is consistent with the data and also accounts for variations and discrepancies in the data. Grounded Theory is widely used in sociology, psychology, management, and other social sciences to study a wide range of phenomena, such as organizational behavior, social interaction, and health care.

History of Grounded Theory

Grounded Theory was first introduced by sociologists Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss in the 1960s as a response to the limitations of traditional positivist approaches to social research. The approach was initially developed to study dying patients and their families in hospitals, but it was soon applied to other areas of sociology and beyond.

Glaser and Strauss published their seminal book “The Discovery of Grounded Theory” in 1967, in which they presented their approach to developing theory from empirical data. They argued that existing social theories often did not account for the complexity and diversity of social phenomena, and that the development of theory should be grounded in empirical data.

Since then, Grounded Theory has become a widely used methodology in the social sciences, and has been applied to a wide range of topics, including healthcare, education, business, and psychology. The approach has also evolved over time, with variations such as constructivist grounded theory and feminist grounded theory being developed to address specific criticisms and limitations of the original approach.

Types of Grounded Theory

There are two main types of Grounded Theory: Classic Grounded Theory and Constructivist Grounded Theory.

Classic Grounded Theory

This approach is based on the work of Glaser and Strauss, and emphasizes the discovery of a theory that is grounded in data. The focus is on generating a theory that explains the phenomenon being studied, without being influenced by preconceived notions or existing theories. The process involves a continuous cycle of data collection, coding, and analysis, with the aim of developing categories and subcategories that are grounded in the data. The categories and subcategories are then compared and synthesized to generate a theory that explains the phenomenon.

Constructivist Grounded Theory

This approach is based on the work of Charmaz, and emphasizes the role of the researcher in the process of theory development. The focus is on understanding how individuals construct meaning and interpret their experiences, rather than on discovering an objective truth. The process involves a reflexive and iterative approach to data collection, coding, and analysis, with the aim of developing categories that are grounded in the data and the researcher’s interpretations of the data. The categories are then compared and synthesized to generate a theory that accounts for the multiple perspectives and interpretations of the phenomenon being studied.

Grounded Theory Conducting Guide

Here are some general guidelines for conducting a Grounded Theory study:

- Choose a research question: Start by selecting a research question that is open-ended and focuses on a specific social phenomenon or problem.

- Select participants and collect data: Identify a diverse group of participants who have experienced the phenomenon being studied. Use a variety of data collection methods such as interviews, observations, and document analysis to collect rich and diverse data.

- Analyze the data: Begin the process of analyzing the data using constant comparison. This involves comparing the data to each other and to existing categories and codes, in order to identify patterns and relationships. Use open coding to identify concepts and categories, and then use axial coding to organize them into a theoretical framework.

- Generate categories and codes: Generate categories and codes that describe the phenomenon being studied. Make sure that they are grounded in the data and that they accurately reflect the experiences of the participants.

- Refine and develop the theory: Use theoretical sampling to identify new data sources that are relevant to the developing theory. Use memoing to reflect on insights and ideas that emerge during the analysis process. Continue to refine and develop the theory until it provides a comprehensive explanation of the phenomenon.

- Validate the theory: Finally, seek to validate the theory by testing it against new data and seeking feedback from peers and other researchers. This process helps to refine and improve the theory, and to ensure that it is grounded in the data.

- Write up and disseminate the findings: Once the theory is fully developed and validated, write up the findings and disseminate them through academic publications and presentations. Make sure to acknowledge the contributions of the participants and to provide a detailed account of the research methods used.

Data Collection Methods

Grounded Theory Data Collection Methods are as follows:

- Interviews : One of the most common data collection methods in Grounded Theory is the use of in-depth interviews. Interviews allow researchers to gather rich and detailed data about the experiences, perspectives, and attitudes of participants. Interviews can be conducted one-on-one or in a group setting.

- Observation : Observation is another data collection method used in Grounded Theory. Researchers may observe participants in their natural settings, such as in a workplace or community setting. This method can provide insights into the social interactions and behaviors of participants.

- Document analysis: Grounded Theory researchers also use document analysis as a data collection method. This involves analyzing existing documents such as reports, policies, or historical records that are relevant to the phenomenon being studied.

- Focus groups : Focus groups involve bringing together a group of participants to discuss a specific topic or issue. This method can provide insights into group dynamics and social interactions.

- Fieldwork : Fieldwork involves immersing oneself in the research setting and participating in the activities of the participants. This method can provide an in-depth understanding of the culture and social dynamics of the research setting.

- Multimedia data: Grounded Theory researchers may also use multimedia data such as photographs, videos, or audio recordings to capture the experiences and perspectives of participants.

Data Analysis Methods

Grounded Theory Data Analysis Methods are as follows:

- Open coding: Open coding is the process of identifying concepts and categories in the data. Researchers use open coding to assign codes to different pieces of data, and to identify similarities and differences between them.

- Axial coding: Axial coding is the process of organizing the codes into broader categories and subcategories. Researchers use axial coding to develop a theoretical framework that explains the phenomenon being studied.

- Constant comparison: Grounded Theory involves a process of constant comparison, in which data is compared to each other and to existing categories and codes in order to identify patterns and relationships.

- Theoretical sampling: Theoretical sampling involves selecting new data sources based on the emerging theory. Researchers use theoretical sampling to collect data that will help refine and validate the theory.

- Memoing : Memoing involves writing down reflections, insights, and ideas as the analysis progresses. This helps researchers to organize their thoughts and develop a deeper understanding of the data.

- Peer debriefing: Peer debriefing involves seeking feedback from peers and other researchers on the developing theory. This process helps to validate the theory and ensure that it is grounded in the data.

- Member checking: Member checking involves sharing the emerging theory with the participants in the study and seeking their feedback. This process helps to ensure that the theory accurately reflects the experiences and perspectives of the participants.

- Triangulation: Triangulation involves using multiple sources of data to validate the emerging theory. Researchers may use different data collection methods, different data sources, or different analysts to ensure that the theory is grounded in the data.

Applications of Grounded Theory

Here are some of the key applications of Grounded Theory:

- Social sciences : Grounded Theory is widely used in social science research, particularly in fields such as sociology, psychology, and anthropology. It can be used to explore a wide range of social phenomena, such as social interactions, power dynamics, and cultural practices.

- Healthcare : Grounded Theory can be used in healthcare research to explore patient experiences, healthcare practices, and healthcare systems. It can provide insights into the factors that influence healthcare outcomes, and can inform the development of interventions and policies.

- Education : Grounded Theory can be used in education research to explore teaching and learning processes, student experiences, and educational policies. It can provide insights into the factors that influence educational outcomes, and can inform the development of educational interventions and policies.

- Business : Grounded Theory can be used in business research to explore organizational processes, management practices, and consumer behavior. It can provide insights into the factors that influence business outcomes, and can inform the development of business strategies and policies.

- Technology : Grounded Theory can be used in technology research to explore user experiences, technology adoption, and technology design. It can provide insights into the factors that influence technology outcomes, and can inform the development of technology interventions and policies.

Examples of Grounded Theory

Examples of Grounded Theory in different case studies are as follows:

- Glaser and Strauss (1965): This study, which is considered one of the foundational works of Grounded Theory, explored the experiences of dying patients in a hospital. The researchers used Grounded Theory to develop a theoretical framework that explained the social processes of dying, and that was grounded in the data.

- Charmaz (1983): This study explored the experiences of chronic illness among young adults. The researcher used Grounded Theory to develop a theoretical framework that explained how individuals with chronic illness managed their illness, and how their illness impacted their sense of self.

- Strauss and Corbin (1990): This study explored the experiences of individuals with chronic pain. The researchers used Grounded Theory to develop a theoretical framework that explained the different strategies that individuals used to manage their pain, and that was grounded in the data.

- Glaser and Strauss (1967): This study explored the experiences of individuals who were undergoing a process of becoming disabled. The researchers used Grounded Theory to develop a theoretical framework that explained the social processes of becoming disabled, and that was grounded in the data.

- Clarke (2005): This study explored the experiences of patients with cancer who were receiving chemotherapy. The researcher used Grounded Theory to develop a theoretical framework that explained the factors that influenced patient adherence to chemotherapy, and that was grounded in the data.

Grounded Theory Research Example

A Grounded Theory Research Example Would be:

Research question : What is the experience of first-generation college students in navigating the college admission process?

Data collection : The researcher conducted interviews with first-generation college students who had recently gone through the college admission process. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis: The researcher used a constant comparative method to analyze the data. This involved coding the data, comparing codes, and constantly revising the codes to identify common themes and patterns. The researcher also used memoing, which involved writing notes and reflections on the data and analysis.

Findings : Through the analysis of the data, the researcher identified several themes related to the experience of first-generation college students in navigating the college admission process, such as feeling overwhelmed by the complexity of the process, lacking knowledge about the process, and facing financial barriers.

Theory development: Based on the findings, the researcher developed a theory about the experience of first-generation college students in navigating the college admission process. The theory suggested that first-generation college students faced unique challenges in the college admission process due to their lack of knowledge and resources, and that these challenges could be addressed through targeted support programs and resources.

In summary, grounded theory research involves collecting data, analyzing it through constant comparison and memoing, and developing a theory grounded in the data. The resulting theory can help to explain the phenomenon being studied and guide future research and interventions.

Purpose of Grounded Theory

The purpose of Grounded Theory is to develop a theoretical framework that explains a social phenomenon, process, or interaction. This theoretical framework is developed through a rigorous process of data collection, coding, and analysis, and is grounded in the data.

Grounded Theory aims to uncover the social processes and patterns that underlie social phenomena, and to develop a theoretical framework that explains these processes and patterns. It is a flexible method that can be used to explore a wide range of research questions and settings, and is particularly well-suited to exploring complex social phenomena that have not been well-studied.

The ultimate goal of Grounded Theory is to generate a theoretical framework that is grounded in the data, and that can be used to explain and predict social phenomena. This theoretical framework can then be used to inform policy and practice, and to guide future research in the field.

When to use Grounded Theory

Following are some situations in which Grounded Theory may be particularly useful:

- Exploring new areas of research: Grounded Theory is particularly useful when exploring new areas of research that have not been well-studied. By collecting and analyzing data, researchers can develop a theoretical framework that explains the social processes and patterns underlying the phenomenon of interest.

- Studying complex social phenomena: Grounded Theory is well-suited to exploring complex social phenomena that involve multiple social processes and interactions. By using an iterative process of data collection and analysis, researchers can develop a theoretical framework that explains the complexity of the social phenomenon.

- Generating hypotheses: Grounded Theory can be used to generate hypotheses about social processes and interactions that can be tested in future research. By developing a theoretical framework that explains a social phenomenon, researchers can identify areas for further research and hypothesis testing.

- Informing policy and practice : Grounded Theory can provide insights into the factors that influence social phenomena, and can inform policy and practice in a variety of fields. By developing a theoretical framework that explains a social phenomenon, researchers can identify areas for intervention and policy development.

Characteristics of Grounded Theory

Grounded Theory is a qualitative research method that is characterized by several key features, including:

- Emergence : Grounded Theory emphasizes the emergence of theoretical categories and concepts from the data, rather than preconceived theoretical ideas. This means that the researcher does not start with a preconceived theory or hypothesis, but instead allows the theory to emerge from the data.

- Iteration : Grounded Theory is an iterative process that involves constant comparison of data and analysis, with each round of data collection and analysis refining the theoretical framework.

- Inductive : Grounded Theory is an inductive method of analysis, which means that it derives meaning from the data. The researcher starts with the raw data and systematically codes and categorizes it to identify patterns and themes, and to develop a theoretical framework that explains these patterns.

- Reflexive : Grounded Theory requires the researcher to be reflexive and self-aware throughout the research process. The researcher’s personal biases and assumptions must be acknowledged and addressed in the analysis process.

- Holistic : Grounded Theory takes a holistic approach to data analysis, looking at the entire data set rather than focusing on individual data points. This allows the researcher to identify patterns and themes that may not be apparent when looking at individual data points.

- Contextual : Grounded Theory emphasizes the importance of understanding the context in which social phenomena occur. This means that the researcher must consider the social, cultural, and historical factors that may influence the phenomenon of interest.

Advantages of Grounded Theory

Advantages of Grounded Theory are as follows:

- Flexibility : Grounded Theory is a flexible method that can be used to explore a wide range of research questions and settings. It is particularly well-suited to exploring complex social phenomena that have not been well-studied.

- Validity : Grounded Theory aims to develop a theoretical framework that is grounded in the data, which enhances the validity and reliability of the research findings. The iterative process of data collection and analysis also helps to ensure that the research findings are reliable and robust.

- Originality : Grounded Theory can generate new and original insights into social phenomena, as it is not constrained by preconceived theoretical ideas or hypotheses. This allows researchers to explore new areas of research and generate new theoretical frameworks.

- Real-world relevance: Grounded Theory can inform policy and practice, as it provides insights into the factors that influence social phenomena. The theoretical frameworks developed through Grounded Theory can be used to inform policy development and intervention strategies.

- Ethical : Grounded Theory is an ethical research method, as it allows participants to have a voice in the research process. Participants’ perspectives are central to the data collection and analysis process, which ensures that their views are taken into account.

- Replication : Grounded Theory is a replicable method of research, as the theoretical frameworks developed through Grounded Theory can be tested and validated in future research.

Limitations of Grounded Theory

Limitations of Grounded Theory are as follows:

- Time-consuming: Grounded Theory can be a time-consuming method, as the iterative process of data collection and analysis requires significant time and effort. This can make it difficult to conduct research in a timely and cost-effective manner.

- Subjectivity : Grounded Theory is a subjective method, as the researcher’s personal biases and assumptions can influence the data analysis process. This can lead to potential issues with reliability and validity of the research findings.

- Generalizability : Grounded Theory is a context-specific method, which means that the theoretical frameworks developed through Grounded Theory may not be generalizable to other contexts or populations. This can limit the applicability of the research findings.

- Lack of structure : Grounded Theory is an exploratory method, which means that it lacks the structure of other research methods, such as surveys or experiments. This can make it difficult to compare findings across different studies.

- Data overload: Grounded Theory can generate a large amount of data, which can be overwhelming for researchers. This can make it difficult to manage and analyze the data effectively.

- Difficulty in publication: Grounded Theory can be challenging to publish in some academic journals, as some reviewers and editors may view it as less rigorous than other research methods.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Cluster Analysis – Types, Methods and Examples

Discriminant Analysis – Methods, Types and...

MANOVA (Multivariate Analysis of Variance) –...

Documentary Analysis – Methods, Applications and...

ANOVA (Analysis of variance) – Formulas, Types...

Graphical Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

Grounded Theory: Approach And Examples

Grounded theory is a qualitative research approach that attempts to uncover the meanings of people’s social actions, interactions and experiences….

Grounded theory is a qualitative research approach that attempts to uncover the meanings of people’s social actions, interactions and experiences. These explanations are called ‘grounded’ because they are grounded in the participants’ own explanations or interpretations.

Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss originated this method in their 1967 book, The Discovery Of Grounded Theory . The grounded theory approach has been used by researchers in various disciplines, including sociology, anthropology, psychology, economics and public health.

Grounded theory qualitative research was considered path-breaking in many respects upon its arrival. The inductive method allowed the analysis of data during the collection process. It also shifted focus away from the existing practice of verification, which researchers felt didn’t always produce rigorous results.

Let’s take a closer look at grounded theory research.

What Is Grounded Theory?

How to conduct grounded theory research, features of grounded theory, grounded theory example, advantages of grounded theory.

Grounded theory is a qualitative method designed to help arrive at new theories and deductions. Researchers collect data through any means they prefer and then analyze the facts to arrive at concepts. Through a comparison of these concepts, they plan theories. They continue until they reach sample saturation, in which no new information upsets the theory they have formulated. Then they put forth their final theory.

In grounded theory research, the framework description guides the researcher’s own interpretation of data. A data description is the researcher’s algorithm for collecting and organizing data while also constructing a conceptual model that can be tested against new observations.

Grounded theory doesn’t assume that there’s a single meaning of an event, object or concept. In grounded theory, you interpret all data as information or materials that fit into categories your research team creates.

Now that we’ve examined what is grounded theory, let’s inspect how it’s conducted. There are four steps involved in grounded theory research:

- STAGE 1: Concepts are derived from interviews, observation and reflection

- STAGE 2: The data is organized into categories that represent themes or subplots

- STAGE 3: As the categories develop, they are compared with one another and two or more competing theories are identified

- STAGE 4: The final step involves the construction of the research hypothesis statement or concept map

Grounded theory is a relatively recent addition to the tools at a researcher’s disposal. There are several methods of conducting grounded theory research. The following processes are common features:

Theoretical Memoing

compile findings.

Data collection in the grounded theory method can include both quantitative and qualitative methods.

By now, it’s clear that grounded theory is unlike other research techniques. Here are some of its salient features:

It Is Personal

It is flexible, it starts with data, data is continually assessed.

Grounded theory qualitative research is a dynamic and flexible approach to research that answers questions other formats can’t.

Grounded theory can be used in organizations to create a competitive advantage for a company. Here are some grounded theory examples:

- Grounded theory is used by marketing departments by letting marketing executives express their views on how to improve their product or service in a structured way

- Grounded theory is often used by the HR department. For instance, they might study why employees are frustrated by their work. Employees can explain what they feel is lacking. HR then gathers this data, examines the results to discover the root cause of their problems and presents solutions

- Grounded theory can help with design decisions, such as how to create a more appealing logo. To do this, the marketing department might interview consumers about their thoughts on their logo and what they like or dislike about it. They will then gather coded data that relates back to the interviews and use this for a second iteration

These are just some of the possible applications of grounded theory in a business setting.

Its flexibility allows its uses to be virtually endless. But there are still advantages and disadvantages that make the grounded theory more or less appropriate for a subject of study. Here are the advantages:

- Grounded theory isn’t concerned with whether or not something has been done before. Instead, grounded theory researchers are interested in what participants say about their experiences. These researchers are looking for meaning

- The grounded theory method allows researchers to use inductive reasoning, ensuring that the researcher views the participant’s perspectives rather than imposing their own ideas. This encourages objectivity and helps prevent preconceived notions from interfering with the process of data collection and analysis

- It allows for constant comparison of data to concepts, which refines the theory as the research proceeds. This is in contrast with methods that look to verify an existing hypothesis only

- Researchers may also choose to conduct experiments to provide support for their research hypotheses. Through an experiment, researchers can test ideas rigorously and provide evidence to support hypotheses and theory development

- It produces a clearer theoretical model that is not overly abstract. It also allows the researcher to see the connections between cases and have a better understanding of how each case fits in with others

- Researchers often produce more refined and detailed analyses of data than with other methods

- Because grounded theory emphasizes the interpretation of the data, it makes it easier for researchers to examine their own preconceived ideas about a topic and critically analyze them.

As with any method, there are some drawbacks too that researchers should consider. Here are a few:

- It doesn’t promote consensus because there are always competing views about the same phenomenon

- It may seem like an overly theoretical approach that produces results that are too open-ended. Grounded theory isn’t concerned with whether something is true/false or right/wrong

- Grounded theory requires a high level of skill and critical thinking from the researcher. They must have a level of objectivity in their approach, ask unbiased, open-minded questions and conduct interviews without being influenced by personal views or agenda.

While professionals may never have to conduct research like this themselves, an understanding of the kinds of analytical tools available can help when there are decisions to be made in the workplace. Harappa’s Thinking Critically course can help with just this. Analytical skills are some of the most sought-after soft skills in the professional world. The earlier managers can master these, the more value they’ll bring to the organization. With our transformative course and inspiring faculty, empower your teams with the ability to think through any problem, no matter how large.

Explore Harappa Diaries to learn more about topics such as Meaning Of Halo Effect , Different Brainstorming Methods , Operant Conditioning Theory of learning and How To Improve Analytical Skills to upgrade your knowledge and skills.

Root out friction in every digital experience, super-charge conversion rates, and optimize digital self-service

Uncover insights from any interaction, deliver AI-powered agent coaching, and reduce cost to serve

Increase revenue and loyalty with real-time insights and recommendations delivered to teams on the ground

Know how your people feel and empower managers to improve employee engagement, productivity, and retention

Take action in the moments that matter most along the employee journey and drive bottom line growth

Whatever they’re are saying, wherever they’re saying it, know exactly what’s going on with your people

Get faster, richer insights with qual and quant tools that make powerful market research available to everyone

Run concept tests, pricing studies, prototyping + more with fast, powerful studies designed by UX research experts

Track your brand performance 24/7 and act quickly to respond to opportunities and challenges in your market

Explore the platform powering Experience Management

- Free Account

- For Digital

- For Customer Care

- For Human Resources

- For Researchers

- Financial Services

- All Industries

Popular Use Cases

- Customer Experience

- Employee Experience

- Employee Exit Interviews

- Net Promoter Score

- Voice of Customer

- Customer Success Hub

- Product Documentation

- Training & Certification

- XM Institute

- Popular Resources

- Customer Stories

Market Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Partnerships

- Marketplace

The annual gathering of the experience leaders at the world’s iconic brands building breakthrough business results, live in Salt Lake City.

- English/AU & NZ

- Español/Europa

- Español/América Latina

- Português Brasileiro

- REQUEST DEMO

- Experience Management

- Grounded Theory Research

Try Qualtrics for free

Your complete guide to grounded theory research.

11 min read If you have an area of interest, but no hypothesis yet, try grounded theory research. You conduct data collection and analysis, forming a theory based on facts. Read our ultimate guide for everything you need to know.

What is grounded theory in research?

Grounded theory is a systematic qualitative research method that collects empirical data first, and then creates a theory ‘grounded’ in the results.

The constant comparative method was developed by Glaser and Strauss, described in their book, Awareness of Dying (1965). They are seen as the founders of classic grounded theory.

Research teams use grounded theory to analyze social processes and relationships.

Because of the important role of data, there are key stages like data collection and data analysis that need to happen in order for the resulting data to be useful.

The grounded research results are compared to strengthen the validity of the findings to arrive at stronger defined theories. Once the data analysis cannot continue to refine the new theories down, a final theory is confirmed.

Grounded research is different from experimental research or scientific inquiry as it does not need a hypothesis theory at the start to verify. Instead, the evolving theory is based on facts and evidence discovered during each stage.Also, grounded research also doesn’t have a preconceived understanding of events or happenings before the qualitative research commences.

Free eBook: Qualitative research design handbook

When should you use grounded theory research?

Grounded theory research is useful for businesses when a researcher wants to look into a topic that has existing theory or no current research available. This means that the qualitative research results will be unique and can open the doors to the social phenomena being investigated.

In addition, businesses can use this qualitative research as the primary evidence needed to understand whether it’s worth placing investment into a new line of product or services, if the research identifies key themes and concepts that point to a solvable commercial problem.

Grounded theory methodology

There are several stages in the grounded theory process:

1. Data planning

The researcher decides what area they’re interested in.

They may create a guide to what they will be collecting during the grounded theory methodology. They will refer to this guide when they want to check the suitability of the qualitative data, as they collect it, to avoid preconceived ideas of what they know impacting the research.

A researcher can set up a grounded theory coding framework to identify the correct data. Coding is associating words, or labels, that are useful to the social phenomena that is being investigated. So, when the researcher sees these words, they assign the data to that category or theme.

In this stage, you’ll also want to create your open-ended initial research questions. Here are the main differences between open and closed-ended questions:

These will need to be adapted as the research goes on and more tangents and areas to explore are discovered. To help you create your questions, ask yourself:

- What are you trying to explain?

- What experiences do you need to ask about?

- Who will you ask and why?

2. Data collection and analysis

Data analysis happens at the same time as data collection. In grounded theory analysis, this is also known as constant comparative analysis, or theoretical sampling.

The researcher collects qualitative data by asking open-ended questions in interviews and surveys, studying historical or archival data, or observing participants and interpreting what is seen. This collected data is transferred into transcripts.

The categories or themes are compared and further refined by data, until there are only a few strong categories or themes remaining. Here is where coding occurs, and there are different levels of coding as the categories or themes are refined down:

- Data collection (Initial coding stage): Read through the data line by line

- Open coding stage: Read through the transcript data several times, breaking down the qualitative research data into excerpts, and make summaries of the concept or theme.

- Axial coding stage: Read through and compare further data collection to summarize concepts or themes to look for similarities and differences. Make defined summaries that help shape an emerging theory.

- Selective coding stage: Use the defined summaries to identify a strong core concept or theme.

During analysis, the researcher will apply theoretical sensitivity to the collected data they uncover, so that the meaning of nuances in what they see can be fully understood.

This coding process repeats until the researcher has reached theoretical saturation. In grounded theory analysis, this is where all data has been researched and there are no more possible categories or themes to explore.

3. Data analysis is turned into a final theory

The researcher takes the core categories and themes that they have gathered and integrates them into one central idea (a new theory) using selective code. This final grounded theory concludes the research.

The new theory should be a few simple sentences that describe the research, indicating what was and was not covered in it.

An example of using grounded theory in business

One example of how grounded theory may be used in business is to support HR teams by analyzing data to explore reasons why people leave a company.

For example, a company with a high attrition rate that has not done any research on this area before may choose grounded theory to understand key reasons why people choose to leave.

Researchers may start looking at the quantitative data around departures over the year and look for patterns. Coupled with this, they may conduct qualitative data research through employee engagement surveys , interview panels for current employees, and exit interviews with leaving employees.

From this information, they may start coding transcripts to find similarities and differences (coding) picking up on general themes and concepts. For example, a group of excepts like:

- “The hours I worked were far too long and I hated traveling home in the dark”

- “My manager didn’t appreciate the work I was doing, especially when I worked late”

- There are no good night bus routes home that I could take safely”

Using open coding, a researcher could compare excerpts and suggest the themes of managerial issues, a culture of long hours and lack of traveling routes at night.

With more samples and information, through axial coding, stronger themes of lack of recognition and having too much work (which led people to working late), could be drawn out from the summaries of the concepts and themes.

This could lead to a selective coding conclusion that people left because they were ‘overworked and under-appreciated’.

With this information, a grounded theory can help HR teams look at what teams do day to day, exploring ways to spread workloads or reduce them. Also, there could be training supplied to management and employees to engage professional development conversations better.

Advantages of grounded theory

- No need for hypothesis – Researchers don’t need to know the details about the topic they want to investigate in advance, as the grounded theory methodology will bring up the information.

- Lots of flexibility – Researchers can take the topic in whichever direction they think is best, based on what the data is telling them. This means that exploration avenues that may be off-limits in traditional experimental research can be included.

- Multiple stages improve conclusion – Having a series of coding stages that refine the data into clear and strong concepts or themes means that the grounded theory will be more useful, relevant and defined.

- Data-first – Grounded theory relies on data analysis in the first instance, so the conclusion is based on information that has strong data behind it. This could be seen as having more validity.

Disadvantages of grounded theory

- Theoretical sensitivity dulled – If a researcher does not know enough about the topic being investigated, then their theoretical sensitivity about what data means may be lower and information may be missed if it is not coded properly.

- Large topics take time – There is a significant time resource required by the researcher to properly conduct research, evaluate the results and compare and analyze each excerpt. If the research process finds more avenues for investigation, for example, when excerpts contradict each other, then the researcher is required to spend more time doing qualitative inquiry.

- Bias in interpreting qualitative data – As the researcher is responsible for interpreting the qualitative data results, and putting their own observations into text, there can be researcher bias that would skew the data and possibly impact the final grounded theory.

- Qualitative research is harder to analyze than quantitative data – unlike numerical factual data from quantitative sources, qualitative data is harder to analyze as researchers will need to look at the words used, the sentiment and what is being said.

- Not repeatable – while the grounded theory can present a fact-based hypothesis, the actual data analysis from the research process cannot be repeated easily as opinions, beliefs and people may change over time. This may impact the validity of the grounded theory result.

What tools will help with grounded theory?

Evaluating qualitative research can be tough when there are several analytics platforms to manage and lots of subjective data sources to compare. Some tools are already part of the office toolset, like video conferencing tools and excel spreadsheets.

However, most tools are not purpose-built for research, so researchers will be manually collecting and managing these files – in the worst case scenario, by pen and paper!

Use a best-in-breed management technology solution to collect all qualitative research and manage it in an organized way without large time resources or additional training required.

Qualtrics provides a number of qualitative research analysis tools, like Text iQ , powered by Qualtrics iQ, provides powerful machine learning and native language processing to help you discover patterns and trends in text.

This also provides you with research process tools:

- Sentiment analysis — a technique to help identify the underlying sentiment (say positive, neutral, and/or negative) in qualitative research text responses

- Topic detection/categorisation — The solution makes it easy to add new qualitative research codes and group by theme. Easily group or bucket of similar themes that can be relevant for the business and the industry (eg. ‘Food quality’, ‘Staff efficiency’ or ‘Product availability’)

Related resources

Market intelligence 10 min read, marketing insights 11 min read, ethnographic research 11 min read, qualitative vs quantitative research 13 min read, qualitative research questions 11 min read, qualitative research design 12 min read, primary vs secondary research 14 min read, request demo.

Ready to learn more about Qualtrics?

- Correspondence

- Open access

- Published: 09 September 2011

How to do a grounded theory study: a worked example of a study of dental practices

- Alexandra Sbaraini 1 , 2 ,

- Stacy M Carter 1 ,

- R Wendell Evans 2 &

- Anthony Blinkhorn 1 , 2

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 11 , Article number: 128 ( 2011 ) Cite this article

381k Accesses

189 Citations

44 Altmetric

Metrics details

Qualitative methodologies are increasingly popular in medical research. Grounded theory is the methodology most-often cited by authors of qualitative studies in medicine, but it has been suggested that many 'grounded theory' studies are not concordant with the methodology. In this paper we provide a worked example of a grounded theory project. Our aim is to provide a model for practice, to connect medical researchers with a useful methodology, and to increase the quality of 'grounded theory' research published in the medical literature.

We documented a worked example of using grounded theory methodology in practice.

We describe our sampling, data collection, data analysis and interpretation. We explain how these steps were consistent with grounded theory methodology, and show how they related to one another. Grounded theory methodology assisted us to develop a detailed model of the process of adapting preventive protocols into dental practice, and to analyse variation in this process in different dental practices.

Conclusions

By employing grounded theory methodology rigorously, medical researchers can better design and justify their methods, and produce high-quality findings that will be more useful to patients, professionals and the research community.

Peer Review reports

Qualitative research is increasingly popular in health and medicine. In recent decades, qualitative researchers in health and medicine have founded specialist journals, such as Qualitative Health Research , established 1991, and specialist conferences such as the Qualitative Health Research conference of the International Institute for Qualitative Methodology, established 1994, and the Global Congress for Qualitative Health Research, established 2011 [ 1 – 3 ]. Journals such as the British Medical Journal have published series about qualitative methodology (1995 and 2008) [ 4 , 5 ]. Bodies overseeing human research ethics, such as the Canadian Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans, and the Australian National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research [ 6 , 7 ], have included chapters or sections on the ethics of qualitative research. The increasing popularity of qualitative methodologies for medical research has led to an increasing awareness of formal qualitative methodologies. This is particularly so for grounded theory, one of the most-cited qualitative methodologies in medical research [[ 8 ], p47].

Grounded theory has a chequered history [ 9 ]. Many authors label their work 'grounded theory' but do not follow the basics of the methodology [ 10 , 11 ]. This may be in part because there are few practical examples of grounded theory in use in the literature. To address this problem, we will provide a brief outline of the history and diversity of grounded theory methodology, and a worked example of the methodology in practice. Our aim is to provide a model for practice, to connect medical researchers with a useful methodology, and to increase the quality of 'grounded theory' research published in the medical literature.

The history, diversity and basic components of 'grounded theory' methodology and method

Founded on the seminal 1967 book 'The Discovery of Grounded Theory' [ 12 ], the grounded theory tradition is now diverse and somewhat fractured, existing in four main types, with a fifth emerging. Types one and two are the work of the original authors: Barney Glaser's 'Classic Grounded Theory' [ 13 ] and Anselm Strauss and Juliet Corbin's 'Basics of Qualitative Research' [ 14 ]. Types three and four are Kathy Charmaz's 'Constructivist Grounded Theory' [ 15 ] and Adele Clarke's postmodern Situational Analysis [ 16 ]: Charmaz and Clarke were both students of Anselm Strauss. The fifth, emerging variant is 'Dimensional Analysis' [ 17 ] which is being developed from the work of Leonard Schaztman, who was a colleague of Strauss and Glaser in the 1960s and 1970s.

There has been some discussion in the literature about what characteristics a grounded theory study must have to be legitimately referred to as 'grounded theory' [ 18 ]. The fundamental components of a grounded theory study are set out in Table 1 . These components may appear in different combinations in other qualitative studies; a grounded theory study should have all of these. As noted, there are few examples of 'how to do' grounded theory in the literature [ 18 , 19 ]. Those that do exist have focused on Strauss and Corbin's methods [ 20 – 25 ]. An exception is Charmaz's own description of her study of chronic illness [ 26 ]; we applied this same variant in our study. In the remainder of this paper, we will show how each of the characteristics of grounded theory methodology worked in our study of dental practices.

Study background

We used grounded theory methodology to investigate social processes in private dental practices in New South Wales (NSW), Australia. This grounded theory study builds on a previous Australian Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) called the Monitor Dental Practice Program (MPP) [ 27 ]. We know that preventive techniques can arrest early tooth decay and thus reduce the need for fillings [ 28 – 32 ]. Unfortunately, most dentists worldwide who encounter early tooth decay continue to drill it out and fill the tooth [ 33 – 37 ]. The MPP tested whether dentists could increase their use of preventive techniques. In the intervention arm, dentists were provided with a set of evidence-based preventive protocols to apply [ 38 ]; control practices provided usual care. The MPP protocols used in the RCT guided dentists to systematically apply preventive techniques to prevent new tooth decay and to arrest early stages of tooth decay in their patients, therefore reducing the need for drilling and filling. The protocols focused on (1) primary prevention of new tooth decay (tooth brushing with high concentration fluoride toothpaste and dietary advice) and (2) intensive secondary prevention through professional treatment to arrest tooth decay progress (application of fluoride varnish, supervised monitoring of dental plaque control and clinical outcomes)[ 38 ].

As the RCT unfolded, it was discovered that practices in the intervention arm were not implementing the preventive protocols uniformly. Why had the outcomes of these systematically implemented protocols been so different? This question was the starting point for our grounded theory study. We aimed to understand how the protocols had been implemented, including the conditions and consequences of variation in the process. We hoped that such understanding would help us to see how the norms of Australian private dental practice as regards to tooth decay could be moved away from drilling and filling and towards evidence-based preventive care.

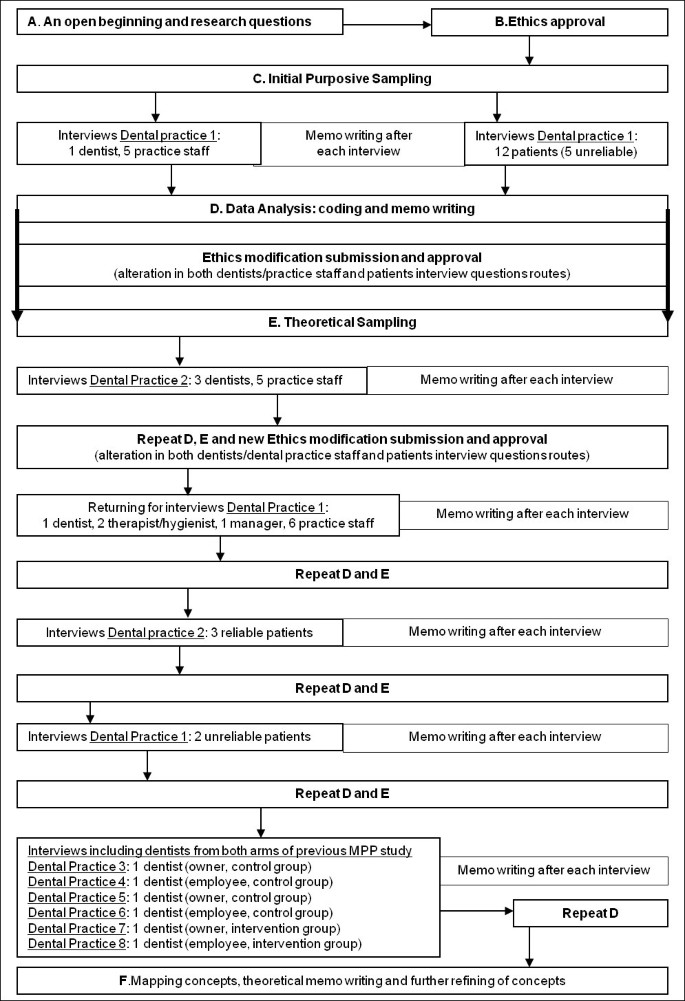

Designing this grounded theory study

Figure 1 illustrates the steps taken during the project that will be described below from points A to F.

Study design . file containing a figure illustrating the study design.

A. An open beginning and research questions

Grounded theory studies are generally focused on social processes or actions: they ask about what happens and how people interact . This shows the influence of symbolic interactionism, a social psychological approach focused on the meaning of human actions [ 39 ]. Grounded theory studies begin with open questions, and researchers presume that they may know little about the meanings that drive the actions of their participants. Accordingly, we sought to learn from participants how the MPP process worked and how they made sense of it. We wanted to answer a practical social problem: how do dentists persist in drilling and filling early stages of tooth decay, when they could be applying preventive care?

We asked research questions that were open, and focused on social processes. Our initial research questions were:

What was the process of implementing (or not-implementing) the protocols (from the perspective of dentists, practice staff, and patients)?

How did this process vary?

B. Ethics approval and ethical issues

In our experience, medical researchers are often concerned about the ethics oversight process for such a flexible, unpredictable study design. We managed this process as follows. Initial ethics approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Sydney. In our application, we explained grounded theory procedures, in particular the fact that they evolve. In our initial application we provided a long list of possible recruitment strategies and interview questions, as suggested by Charmaz [ 15 ]. We indicated that we would make future applications to modify our protocols. We did this as the study progressed - detailed below. Each time we reminded the committee that our study design was intended to evolve with ongoing modifications. Each modification was approved without difficulty. As in any ethical study, we ensured that participation was voluntary, that participants could withdraw at any time, and that confidentiality was protected. All responses were anonymised before analysis, and we took particular care not to reveal potentially identifying details of places, practices or clinicians.

C. Initial, Purposive Sampling (before theoretical sampling was possible)

Grounded theory studies are characterised by theoretical sampling, but this requires some data to be collected and analysed. Sampling must thus begin purposively, as in any qualitative study. Participants in the previous MPP study provided our population [ 27 ]. The MPP included 22 private dental practices in NSW, randomly allocated to either the intervention or control group. With permission of the ethics committee; we sent letters to the participants in the MPP, inviting them to participate in a further qualitative study. From those who agreed, we used the quantitative data from the MPP to select an initial sample.

Then, we selected the practice in which the most dramatic results had been achieved in the MPP study (Dental Practice 1). This was a purposive sampling strategy, to give us the best possible access to the process of successfully implementing the protocols. We interviewed all consenting staff who had been involved in the MPP (one dentist, five dental assistants). We then recruited 12 patients who had been enrolled in the MPP, based on their clinically measured risk of developing tooth decay: we selected some patients whose risk status had gotten better, some whose risk had worsened and some whose risk had stayed the same. This purposive sample was designed to provide maximum variation in patients' adoption of preventive dental care.

Initial Interviews

One hour in-depth interviews were conducted. The researcher/interviewer (AS) travelled to a rural town in NSW where interviews took place. The initial 18 participants (one dentist, five dental assistants and 12 patients) from Dental Practice 1 were interviewed in places convenient to them such as the dental practice, community centres or the participant's home.

Two initial interview schedules were designed for each group of participants: 1) dentists and dental practice staff and 2) dental patients. Interviews were semi-structured and based loosely on the research questions. The initial questions for dentists and practice staff are in Additional file 1 . Interviews were digitally recorded and professionally transcribed. The research location was remote from the researcher's office, thus data collection was divided into two episodes to allow for intermittent data analysis. Dentist and practice staff interviews were done in one week. The researcher wrote memos throughout this week. The researcher then took a month for data analysis in which coding and memo-writing occurred. Then during a return visit, patient interviews were completed, again with memo-writing during the data-collection period.

D. Data Analysis

Coding and the constant comparative method.

Coding is essential to the development of a grounded theory [ 15 ]. According to Charmaz [[ 15 ], p46], 'coding is the pivotal link between collecting data and developing an emergent theory to explain these data. Through coding, you define what is happening in the data and begin to grapple with what it means'. Coding occurs in stages. In initial coding, the researcher generates as many ideas as possible inductively from early data. In focused coding, the researcher pursues a selected set of central codes throughout the entire dataset and the study. This requires decisions about which initial codes are most prevalent or important, and which contribute most to the analysis. In theoretical coding, the researcher refines the final categories in their theory and relates them to one another. Charmaz's method, like Glaser's method [ 13 ], captures actions or processes by using gerunds as codes (verbs ending in 'ing'); Charmaz also emphasises coding quickly, and keeping the codes as similar to the data as possible.

We developed our coding systems individually and through team meetings and discussions.

We have provided a worked example of coding in Table 2 . Gerunds emphasise actions and processes. Initial coding identifies many different processes. After the first few interviews, we had a large amount of data and many initial codes. This included a group of codes that captured how dentists sought out evidence when they were exposed to a complex clinical case, a new product or technique. Because this process seemed central to their practice, and because it was talked about often, we decided that seeking out evidence should become a focused code. By comparing codes against codes and data against data, we distinguished the category of "seeking out evidence" from other focused codes, such as "gathering and comparing peers' evidence to reach a conclusion", and we understood the relationships between them. Using this constant comparative method (see Table 1 ), we produced a theoretical code: "making sense of evidence and constructing knowledge". This code captured the social process that dentists went through when faced with new information or a practice challenge. This theoretical code will be the focus of a future paper.

Memo-writing

Throughout the study, we wrote extensive case-based memos and conceptual memos. After each interview, the interviewer/researcher (AS) wrote a case-based memo reflecting on what she learned from that interview. They contained the interviewer's impressions about the participants' experiences, and the interviewer's reactions; they were also used to systematically question some of our pre-existing ideas in relation to what had been said in the interview. Table 3 illustrates one of those memos. After a few interviews, the interviewer/researcher also began making and recording comparisons among these memos.

We also wrote conceptual memos about the initial codes and focused codes being developed, as described by Charmaz [ 15 ]. We used these memos to record our thinking about the meaning of codes and to record our thinking about how and when processes occurred, how they changed, and what their consequences were. In these memos, we made comparisons between data, cases and codes in order to find similarities and differences, and raised questions to be answered in continuing interviews. Table 4 illustrates a conceptual memo.

At the end of our data collection and analysis from Dental Practice 1, we had developed a tentative model of the process of implementing the protocols, from the perspective of dentists, dental practice staff and patients. This was expressed in both diagrams and memos, was built around a core set of focused codes, and illustrated relationships between them.

E. Theoretical sampling, ongoing data analysis and alteration of interview route

We have already described our initial purposive sampling. After our initial data collection and analysis, we used theoretical sampling (see Table 1 ) to determine who to sample next and what questions to ask during interviews. We submitted Ethics Modification applications for changes in our question routes, and had no difficulty with approval. We will describe how the interview questions for dentists and dental practice staff evolved, and how we selected new participants to allow development of our substantive theory. The patients' interview schedule and theoretical sampling followed similar procedures.

Evolution of theoretical sampling and interview questions

We now had a detailed provisional model of the successful process implemented in Dental Practice 1. Important core focused codes were identified, including practical/financial, historical and philosophical dimensions of the process. However, we did not yet understand how the process might vary or go wrong, as implementation in the first practice we studied had been described as seamless and beneficial for everyone. Because our aim was to understand the process of implementing the protocols, including the conditions and consequences of variation in the process, we needed to understand how implementation might fail. For this reason, we theoretically sampled participants from Dental Practice 2, where uptake of the MPP protocols had been very limited according to data from the RCT trial.

We also changed our interview questions based on the analysis we had already done (see Additional file 2 ). In our analysis of data from Dental Practice 1, we had learned that "effectiveness" of treatments and "evidence" both had a range of meanings. We also learned that new technologies - in particular digital x-rays and intra-oral cameras - had been unexpectedly important to the process of implementing the protocols. For this reason, we added new questions for the interviews in Dental Practice 2 to directly investigate "effectiveness", "evidence" and how dentists took up new technologies in their practice.

Then, in Dental Practice 2 we learned more about the barriers dentists and practice staff encountered during the process of implementing the MPP protocols. We confirmed and enriched our understanding of dentists' processes for adopting technology and producing knowledge, dealing with complex cases and we further clarified the concept of evidence. However there was a new, important, unexpected finding in Dental Practice 2. Dentists talked about "unreliable" patients - that is, patients who were too unreliable to have preventive dental care offered to them. This seemed to be a potentially important explanation for non-implementation of the protocols. We modified our interview schedule again to include questions about this concept (see Additional file 3 ) leading to another round of ethics approvals. We also returned to Practice 1 to ask participants about the idea of an "unreliable" patient.

Dentists' construction of the "unreliable" patient during interviews also prompted us to theoretically sample for "unreliable" and "reliable" patients in the following round of patients' interviews. The patient question route was also modified by the analysis of the dentists' and practice staff data. We wanted to compare dentists' perspectives with the perspectives of the patients themselves. Dentists were asked to select "reliable" and "unreliable" patients to be interviewed. Patients were asked questions about what kind of services dentists should provide and what patients valued when coming to the dentist. We found that these patients (10 reliable and 7 unreliable) talked in very similar ways about dental care. This finding suggested to us that some deeply-held assumptions within the dental profession may not be shared by dental patients.

At this point, we decided to theoretically sample dental practices from the non-intervention arm of the MPP study. This is an example of the 'openness' of a grounded theory study potentially subtly shifting the focus of the study. Our analysis had shifted our focus: rather than simply studying the process of implementing the evidence-based preventive protocols, we were studying the process of doing prevention in private dental practice. All participants seemed to be revealing deeply held perspectives shared in the dental profession, whether or not they were providing dental care as outlined in the MPP protocols. So, by sampling dentists from both intervention and control group from the previous MPP study, we aimed to confirm or disconfirm the broader reach of our emerging theory and to complete inductive development of key concepts. Theoretical sampling added 12 face to face interviews and 10 telephone interviews to the data. A total of 40 participants between the ages of 18 and 65 were recruited. Telephone interviews were of comparable length, content and quality to face to face interviews, as reported elsewhere in the literature [ 40 ].

F. Mapping concepts, theoretical memo writing and further refining of concepts

After theoretical sampling, we could begin coding theoretically. We fleshed out each major focused code, examining the situations in which they appeared, when they changed and the relationship among them. At time of writing, we have reached theoretical saturation (see Table 1 ). We have been able to determine this in several ways. As we have become increasingly certain about our central focused codes, we have re-examined the data to find all available insights regarding those codes. We have drawn diagrams and written memos. We have looked rigorously for events or accounts not explained by the emerging theory so as to develop it further to explain all of the data. Our theory, which is expressed as a set of concepts that are related to one another in a cohesive way, now accounts adequately for all the data we have collected. We have presented the developing theory to specialist dental audiences and to the participants, and have found that it was accepted by and resonated with these audiences.

We have used these procedures to construct a detailed, multi-faceted model of the process of incorporating prevention into private general dental practice. This model includes relationships among concepts, consequences of the process, and variations in the process. A concrete example of one of our final key concepts is the process of "adapting to" prevention. More commonly in the literature writers speak of adopting, implementing or translating evidence-based preventive protocols into practice. Through our analysis, we concluded that what was required was 'adapting to' those protocols in practice. Some dental practices underwent a slow process of adapting evidence-based guidance to their existing practice logistics. Successful adaptation was contingent upon whether (1) the dentist-in-charge brought the whole dental team together - including other dentists - and got everyone interested and actively participating during preventive activities; (2) whether the physical environment of the practice was re-organised around preventive activities, (3) whether the dental team was able to devise new and efficient routines to accommodate preventive activities, and (4) whether the fee schedule was amended to cover the delivery of preventive services, which hitherto was considered as "unproductive time".