Qualitative Research – a practical guide for health and social care researchers and practitioners

(0 reviews)

Darshini Ayton, Monash University

Tess Tsindos, Monash University

Danielle Berkovic, Monash University

Copyright Year: 2023

Last Update: 2024

ISBN 13: 9780645755404

Publisher: Monash University

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Table of Contents

- Acknowledgement of Country

- About the authors

- Accessibility statement

- Introduction to research

- Research design

- Data collection

- Data analysis

- Writing qualitative research

- Peer review statement

- Licensing and attribution information

- Version history

Ancillary Material

About the book.

This guide is designed to support health and social care researchers and practitioners to integrate qualitative research into the evidence base of health and social care research. Qualitative research designs are diverse and each design has a different focus that will inform the approach undertaken and the results that are generated. The aim is to move beyond the “what” of qualitative research to the “how”, by (1) outlining key qualitative research designs for health and social care research – descriptive, phenomenology, action research, case study, ethnography, and grounded theory; (2) a decision tool of how to select the appropriate design based on a guiding prompting question, the research question and available resources, time and expertise; (3) an overview of mixed methods research and qualitative research in evaluation studies; (4) a practical guide to data collection and analysis; (5) providing examples of qualitative research to illustrate the scope and opportunities; and (6) tips on communicating qualitative research.

About the Contributors

Associate Professor Darshini Ayton is the Deputy Head of the Health and Social Care Unit at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. She is a transdisciplinary implementation researcher with a focus on improving health and social care for older Australians and operates at the nexus of implementation science, health and social care policies, public health and consumer engagement. She has led qualitative research studies in hospitals, aged care, not-for-profit organisations and for government and utilises a range of data collection methods. Associate Professor Ayton established and is the director of the highly successful Qualitative Research Methods for Public Health short course which has been running since 2014.

Dr Tess Tsindos is a Research Fellow with the Health and Social Care Unit at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. She is a public health researcher and lecturer with strong qualitative and mixed methods research experience conducting research studies in hospital and community health settings, not-for-profit organisations and for government. Prior to working in academia, Dr Tsindos worked in community care for government and not-for-profit organisations for more than 25 years. Dr Tsindos has a strong evaluation background having conducted numerous evaluations for a range of health and social care organisations. Based on this experience she coordinated the Bachelor of Health Science/Public Health Evaluation unit and the Master of Public Health Evaluation unit and developed the Evaluating Public Health Programs short course in 2022. Dr Tsindos is the Unit Coordinator of the Master of Public Health Qualitative Research Methods Unit which was established in 2022.

Dr Danielle Berkovic is a Research Fellow in the School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. She is a public health and consumer-led researcher with strong qualitative and mixed-methods research experience focused on improving health services and clinical guidelines for people with arthritis and other musculoskeletal conditions. She has conducted qualitative research studies in hospitals and community health settings. Dr Berkovic currently provides qualitative input into Australia’s first Living Guideline for the pharmacological management of inflammatory arthritis. Dr Berkovic is passionate about incorporating qualitative research methods into traditionally clinical and quantitative spaces and enjoys teaching clinicians and up-and-coming researchers about the benefits of qualitative research.

Contribute to this Page

- Open access

- Published: 27 May 2020

How to use and assess qualitative research methods

- Loraine Busetto ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9228-7875 1 ,

- Wolfgang Wick 1 , 2 &

- Christoph Gumbinger 1

Neurological Research and Practice volume 2 , Article number: 14 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

676k Accesses

262 Citations

88 Altmetric

Metrics details

This paper aims to provide an overview of the use and assessment of qualitative research methods in the health sciences. Qualitative research can be defined as the study of the nature of phenomena and is especially appropriate for answering questions of why something is (not) observed, assessing complex multi-component interventions, and focussing on intervention improvement. The most common methods of data collection are document study, (non-) participant observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups. For data analysis, field-notes and audio-recordings are transcribed into protocols and transcripts, and coded using qualitative data management software. Criteria such as checklists, reflexivity, sampling strategies, piloting, co-coding, member-checking and stakeholder involvement can be used to enhance and assess the quality of the research conducted. Using qualitative in addition to quantitative designs will equip us with better tools to address a greater range of research problems, and to fill in blind spots in current neurological research and practice.

The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of qualitative research methods, including hands-on information on how they can be used, reported and assessed. This article is intended for beginning qualitative researchers in the health sciences as well as experienced quantitative researchers who wish to broaden their understanding of qualitative research.

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is defined as “the study of the nature of phenomena”, including “their quality, different manifestations, the context in which they appear or the perspectives from which they can be perceived” , but excluding “their range, frequency and place in an objectively determined chain of cause and effect” [ 1 ]. This formal definition can be complemented with a more pragmatic rule of thumb: qualitative research generally includes data in form of words rather than numbers [ 2 ].

Why conduct qualitative research?

Because some research questions cannot be answered using (only) quantitative methods. For example, one Australian study addressed the issue of why patients from Aboriginal communities often present late or not at all to specialist services offered by tertiary care hospitals. Using qualitative interviews with patients and staff, it found one of the most significant access barriers to be transportation problems, including some towns and communities simply not having a bus service to the hospital [ 3 ]. A quantitative study could have measured the number of patients over time or even looked at possible explanatory factors – but only those previously known or suspected to be of relevance. To discover reasons for observed patterns, especially the invisible or surprising ones, qualitative designs are needed.

While qualitative research is common in other fields, it is still relatively underrepresented in health services research. The latter field is more traditionally rooted in the evidence-based-medicine paradigm, as seen in " research that involves testing the effectiveness of various strategies to achieve changes in clinical practice, preferably applying randomised controlled trial study designs (...) " [ 4 ]. This focus on quantitative research and specifically randomised controlled trials (RCT) is visible in the idea of a hierarchy of research evidence which assumes that some research designs are objectively better than others, and that choosing a "lesser" design is only acceptable when the better ones are not practically or ethically feasible [ 5 , 6 ]. Others, however, argue that an objective hierarchy does not exist, and that, instead, the research design and methods should be chosen to fit the specific research question at hand – "questions before methods" [ 2 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. This means that even when an RCT is possible, some research problems require a different design that is better suited to addressing them. Arguing in JAMA, Berwick uses the example of rapid response teams in hospitals, which he describes as " a complex, multicomponent intervention – essentially a process of social change" susceptible to a range of different context factors including leadership or organisation history. According to him, "[in] such complex terrain, the RCT is an impoverished way to learn. Critics who use it as a truth standard in this context are incorrect" [ 8 ] . Instead of limiting oneself to RCTs, Berwick recommends embracing a wider range of methods , including qualitative ones, which for "these specific applications, (...) are not compromises in learning how to improve; they are superior" [ 8 ].

Research problems that can be approached particularly well using qualitative methods include assessing complex multi-component interventions or systems (of change), addressing questions beyond “what works”, towards “what works for whom when, how and why”, and focussing on intervention improvement rather than accreditation [ 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. Using qualitative methods can also help shed light on the “softer” side of medical treatment. For example, while quantitative trials can measure the costs and benefits of neuro-oncological treatment in terms of survival rates or adverse effects, qualitative research can help provide a better understanding of patient or caregiver stress, visibility of illness or out-of-pocket expenses.

How to conduct qualitative research?

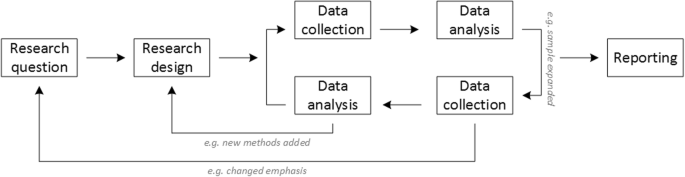

Given that qualitative research is characterised by flexibility, openness and responsivity to context, the steps of data collection and analysis are not as separate and consecutive as they tend to be in quantitative research [ 13 , 14 ]. As Fossey puts it : “sampling, data collection, analysis and interpretation are related to each other in a cyclical (iterative) manner, rather than following one after another in a stepwise approach” [ 15 ]. The researcher can make educated decisions with regard to the choice of method, how they are implemented, and to which and how many units they are applied [ 13 ]. As shown in Fig. 1 , this can involve several back-and-forth steps between data collection and analysis where new insights and experiences can lead to adaption and expansion of the original plan. Some insights may also necessitate a revision of the research question and/or the research design as a whole. The process ends when saturation is achieved, i.e. when no relevant new information can be found (see also below: sampling and saturation). For reasons of transparency, it is essential for all decisions as well as the underlying reasoning to be well-documented.

Iterative research process

While it is not always explicitly addressed, qualitative methods reflect a different underlying research paradigm than quantitative research (e.g. constructivism or interpretivism as opposed to positivism). The choice of methods can be based on the respective underlying substantive theory or theoretical framework used by the researcher [ 2 ].

Data collection

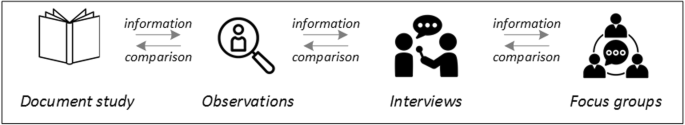

The methods of qualitative data collection most commonly used in health research are document study, observations, semi-structured interviews and focus groups [ 1 , 14 , 16 , 17 ].

Document study

Document study (also called document analysis) refers to the review by the researcher of written materials [ 14 ]. These can include personal and non-personal documents such as archives, annual reports, guidelines, policy documents, diaries or letters.

Observations

Observations are particularly useful to gain insights into a certain setting and actual behaviour – as opposed to reported behaviour or opinions [ 13 ]. Qualitative observations can be either participant or non-participant in nature. In participant observations, the observer is part of the observed setting, for example a nurse working in an intensive care unit [ 18 ]. In non-participant observations, the observer is “on the outside looking in”, i.e. present in but not part of the situation, trying not to influence the setting by their presence. Observations can be planned (e.g. for 3 h during the day or night shift) or ad hoc (e.g. as soon as a stroke patient arrives at the emergency room). During the observation, the observer takes notes on everything or certain pre-determined parts of what is happening around them, for example focusing on physician-patient interactions or communication between different professional groups. Written notes can be taken during or after the observations, depending on feasibility (which is usually lower during participant observations) and acceptability (e.g. when the observer is perceived to be judging the observed). Afterwards, these field notes are transcribed into observation protocols. If more than one observer was involved, field notes are taken independently, but notes can be consolidated into one protocol after discussions. Advantages of conducting observations include minimising the distance between the researcher and the researched, the potential discovery of topics that the researcher did not realise were relevant and gaining deeper insights into the real-world dimensions of the research problem at hand [ 18 ].

Semi-structured interviews

Hijmans & Kuyper describe qualitative interviews as “an exchange with an informal character, a conversation with a goal” [ 19 ]. Interviews are used to gain insights into a person’s subjective experiences, opinions and motivations – as opposed to facts or behaviours [ 13 ]. Interviews can be distinguished by the degree to which they are structured (i.e. a questionnaire), open (e.g. free conversation or autobiographical interviews) or semi-structured [ 2 , 13 ]. Semi-structured interviews are characterized by open-ended questions and the use of an interview guide (or topic guide/list) in which the broad areas of interest, sometimes including sub-questions, are defined [ 19 ]. The pre-defined topics in the interview guide can be derived from the literature, previous research or a preliminary method of data collection, e.g. document study or observations. The topic list is usually adapted and improved at the start of the data collection process as the interviewer learns more about the field [ 20 ]. Across interviews the focus on the different (blocks of) questions may differ and some questions may be skipped altogether (e.g. if the interviewee is not able or willing to answer the questions or for concerns about the total length of the interview) [ 20 ]. Qualitative interviews are usually not conducted in written format as it impedes on the interactive component of the method [ 20 ]. In comparison to written surveys, qualitative interviews have the advantage of being interactive and allowing for unexpected topics to emerge and to be taken up by the researcher. This can also help overcome a provider or researcher-centred bias often found in written surveys, which by nature, can only measure what is already known or expected to be of relevance to the researcher. Interviews can be audio- or video-taped; but sometimes it is only feasible or acceptable for the interviewer to take written notes [ 14 , 16 , 20 ].

Focus groups

Focus groups are group interviews to explore participants’ expertise and experiences, including explorations of how and why people behave in certain ways [ 1 ]. Focus groups usually consist of 6–8 people and are led by an experienced moderator following a topic guide or “script” [ 21 ]. They can involve an observer who takes note of the non-verbal aspects of the situation, possibly using an observation guide [ 21 ]. Depending on researchers’ and participants’ preferences, the discussions can be audio- or video-taped and transcribed afterwards [ 21 ]. Focus groups are useful for bringing together homogeneous (to a lesser extent heterogeneous) groups of participants with relevant expertise and experience on a given topic on which they can share detailed information [ 21 ]. Focus groups are a relatively easy, fast and inexpensive method to gain access to information on interactions in a given group, i.e. “the sharing and comparing” among participants [ 21 ]. Disadvantages include less control over the process and a lesser extent to which each individual may participate. Moreover, focus group moderators need experience, as do those tasked with the analysis of the resulting data. Focus groups can be less appropriate for discussing sensitive topics that participants might be reluctant to disclose in a group setting [ 13 ]. Moreover, attention must be paid to the emergence of “groupthink” as well as possible power dynamics within the group, e.g. when patients are awed or intimidated by health professionals.

Choosing the “right” method

As explained above, the school of thought underlying qualitative research assumes no objective hierarchy of evidence and methods. This means that each choice of single or combined methods has to be based on the research question that needs to be answered and a critical assessment with regard to whether or to what extent the chosen method can accomplish this – i.e. the “fit” between question and method [ 14 ]. It is necessary for these decisions to be documented when they are being made, and to be critically discussed when reporting methods and results.

Let us assume that our research aim is to examine the (clinical) processes around acute endovascular treatment (EVT), from the patient’s arrival at the emergency room to recanalization, with the aim to identify possible causes for delay and/or other causes for sub-optimal treatment outcome. As a first step, we could conduct a document study of the relevant standard operating procedures (SOPs) for this phase of care – are they up-to-date and in line with current guidelines? Do they contain any mistakes, irregularities or uncertainties that could cause delays or other problems? Regardless of the answers to these questions, the results have to be interpreted based on what they are: a written outline of what care processes in this hospital should look like. If we want to know what they actually look like in practice, we can conduct observations of the processes described in the SOPs. These results can (and should) be analysed in themselves, but also in comparison to the results of the document analysis, especially as regards relevant discrepancies. Do the SOPs outline specific tests for which no equipment can be observed or tasks to be performed by specialized nurses who are not present during the observation? It might also be possible that the written SOP is outdated, but the actual care provided is in line with current best practice. In order to find out why these discrepancies exist, it can be useful to conduct interviews. Are the physicians simply not aware of the SOPs (because their existence is limited to the hospital’s intranet) or do they actively disagree with them or does the infrastructure make it impossible to provide the care as described? Another rationale for adding interviews is that some situations (or all of their possible variations for different patient groups or the day, night or weekend shift) cannot practically or ethically be observed. In this case, it is possible to ask those involved to report on their actions – being aware that this is not the same as the actual observation. A senior physician’s or hospital manager’s description of certain situations might differ from a nurse’s or junior physician’s one, maybe because they intentionally misrepresent facts or maybe because different aspects of the process are visible or important to them. In some cases, it can also be relevant to consider to whom the interviewee is disclosing this information – someone they trust, someone they are otherwise not connected to, or someone they suspect or are aware of being in a potentially “dangerous” power relationship to them. Lastly, a focus group could be conducted with representatives of the relevant professional groups to explore how and why exactly they provide care around EVT. The discussion might reveal discrepancies (between SOPs and actual care or between different physicians) and motivations to the researchers as well as to the focus group members that they might not have been aware of themselves. For the focus group to deliver relevant information, attention has to be paid to its composition and conduct, for example, to make sure that all participants feel safe to disclose sensitive or potentially problematic information or that the discussion is not dominated by (senior) physicians only. The resulting combination of data collection methods is shown in Fig. 2 .

Possible combination of data collection methods

Attributions for icons: “Book” by Serhii Smirnov, “Interview” by Adrien Coquet, FR, “Magnifying Glass” by anggun, ID, “Business communication” by Vectors Market; all from the Noun Project

The combination of multiple data source as described for this example can be referred to as “triangulation”, in which multiple measurements are carried out from different angles to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under study [ 22 , 23 ].

Data analysis

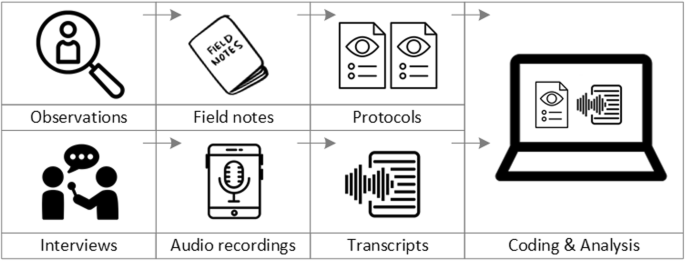

To analyse the data collected through observations, interviews and focus groups these need to be transcribed into protocols and transcripts (see Fig. 3 ). Interviews and focus groups can be transcribed verbatim , with or without annotations for behaviour (e.g. laughing, crying, pausing) and with or without phonetic transcription of dialects and filler words, depending on what is expected or known to be relevant for the analysis. In the next step, the protocols and transcripts are coded , that is, marked (or tagged, labelled) with one or more short descriptors of the content of a sentence or paragraph [ 2 , 15 , 23 ]. Jansen describes coding as “connecting the raw data with “theoretical” terms” [ 20 ]. In a more practical sense, coding makes raw data sortable. This makes it possible to extract and examine all segments describing, say, a tele-neurology consultation from multiple data sources (e.g. SOPs, emergency room observations, staff and patient interview). In a process of synthesis and abstraction, the codes are then grouped, summarised and/or categorised [ 15 , 20 ]. The end product of the coding or analysis process is a descriptive theory of the behavioural pattern under investigation [ 20 ]. The coding process is performed using qualitative data management software, the most common ones being InVivo, MaxQDA and Atlas.ti. It should be noted that these are data management tools which support the analysis performed by the researcher(s) [ 14 ].

From data collection to data analysis

Attributions for icons: see Fig. 2 , also “Speech to text” by Trevor Dsouza, “Field Notes” by Mike O’Brien, US, “Voice Record” by ProSymbols, US, “Inspection” by Made, AU, and “Cloud” by Graphic Tigers; all from the Noun Project

How to report qualitative research?

Protocols of qualitative research can be published separately and in advance of the study results. However, the aim is not the same as in RCT protocols, i.e. to pre-define and set in stone the research questions and primary or secondary endpoints. Rather, it is a way to describe the research methods in detail, which might not be possible in the results paper given journals’ word limits. Qualitative research papers are usually longer than their quantitative counterparts to allow for deep understanding and so-called “thick description”. In the methods section, the focus is on transparency of the methods used, including why, how and by whom they were implemented in the specific study setting, so as to enable a discussion of whether and how this may have influenced data collection, analysis and interpretation. The results section usually starts with a paragraph outlining the main findings, followed by more detailed descriptions of, for example, the commonalities, discrepancies or exceptions per category [ 20 ]. Here it is important to support main findings by relevant quotations, which may add information, context, emphasis or real-life examples [ 20 , 23 ]. It is subject to debate in the field whether it is relevant to state the exact number or percentage of respondents supporting a certain statement (e.g. “Five interviewees expressed negative feelings towards XYZ”) [ 21 ].

How to combine qualitative with quantitative research?

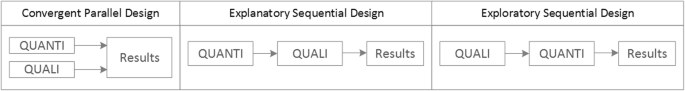

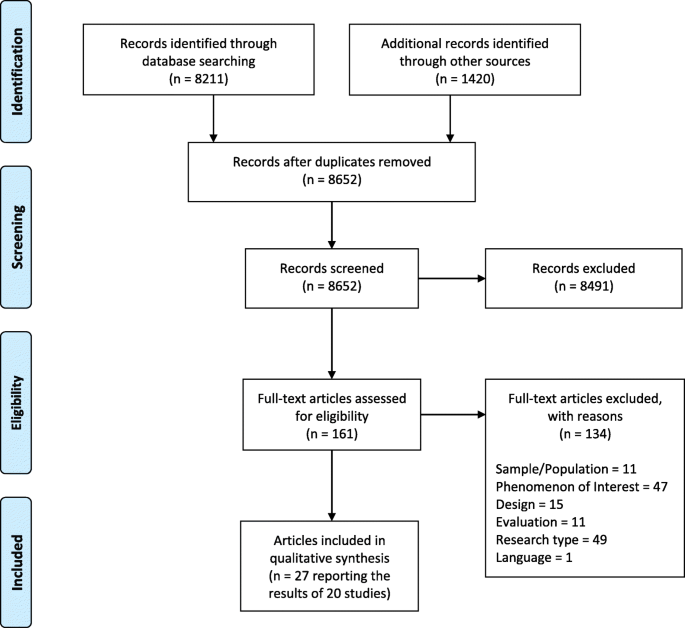

Qualitative methods can be combined with other methods in multi- or mixed methods designs, which “[employ] two or more different methods [ …] within the same study or research program rather than confining the research to one single method” [ 24 ]. Reasons for combining methods can be diverse, including triangulation for corroboration of findings, complementarity for illustration and clarification of results, expansion to extend the breadth and range of the study, explanation of (unexpected) results generated with one method with the help of another, or offsetting the weakness of one method with the strength of another [ 1 , 17 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. The resulting designs can be classified according to when, why and how the different quantitative and/or qualitative data strands are combined. The three most common types of mixed method designs are the convergent parallel design , the explanatory sequential design and the exploratory sequential design. The designs with examples are shown in Fig. 4 .

Three common mixed methods designs

In the convergent parallel design, a qualitative study is conducted in parallel to and independently of a quantitative study, and the results of both studies are compared and combined at the stage of interpretation of results. Using the above example of EVT provision, this could entail setting up a quantitative EVT registry to measure process times and patient outcomes in parallel to conducting the qualitative research outlined above, and then comparing results. Amongst other things, this would make it possible to assess whether interview respondents’ subjective impressions of patients receiving good care match modified Rankin Scores at follow-up, or whether observed delays in care provision are exceptions or the rule when compared to door-to-needle times as documented in the registry. In the explanatory sequential design, a quantitative study is carried out first, followed by a qualitative study to help explain the results from the quantitative study. This would be an appropriate design if the registry alone had revealed relevant delays in door-to-needle times and the qualitative study would be used to understand where and why these occurred, and how they could be improved. In the exploratory design, the qualitative study is carried out first and its results help informing and building the quantitative study in the next step [ 26 ]. If the qualitative study around EVT provision had shown a high level of dissatisfaction among the staff members involved, a quantitative questionnaire investigating staff satisfaction could be set up in the next step, informed by the qualitative study on which topics dissatisfaction had been expressed. Amongst other things, the questionnaire design would make it possible to widen the reach of the research to more respondents from different (types of) hospitals, regions, countries or settings, and to conduct sub-group analyses for different professional groups.

How to assess qualitative research?

A variety of assessment criteria and lists have been developed for qualitative research, ranging in their focus and comprehensiveness [ 14 , 17 , 27 ]. However, none of these has been elevated to the “gold standard” in the field. In the following, we therefore focus on a set of commonly used assessment criteria that, from a practical standpoint, a researcher can look for when assessing a qualitative research report or paper.

Assessors should check the authors’ use of and adherence to the relevant reporting checklists (e.g. Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR)) to make sure all items that are relevant for this type of research are addressed [ 23 , 28 ]. Discussions of quantitative measures in addition to or instead of these qualitative measures can be a sign of lower quality of the research (paper). Providing and adhering to a checklist for qualitative research contributes to an important quality criterion for qualitative research, namely transparency [ 15 , 17 , 23 ].

Reflexivity

While methodological transparency and complete reporting is relevant for all types of research, some additional criteria must be taken into account for qualitative research. This includes what is called reflexivity, i.e. sensitivity to the relationship between the researcher and the researched, including how contact was established and maintained, or the background and experience of the researcher(s) involved in data collection and analysis. Depending on the research question and population to be researched this can be limited to professional experience, but it may also include gender, age or ethnicity [ 17 , 27 ]. These details are relevant because in qualitative research, as opposed to quantitative research, the researcher as a person cannot be isolated from the research process [ 23 ]. It may influence the conversation when an interviewed patient speaks to an interviewer who is a physician, or when an interviewee is asked to discuss a gynaecological procedure with a male interviewer, and therefore the reader must be made aware of these details [ 19 ].

Sampling and saturation

The aim of qualitative sampling is for all variants of the objects of observation that are deemed relevant for the study to be present in the sample “ to see the issue and its meanings from as many angles as possible” [ 1 , 16 , 19 , 20 , 27 ] , and to ensure “information-richness [ 15 ]. An iterative sampling approach is advised, in which data collection (e.g. five interviews) is followed by data analysis, followed by more data collection to find variants that are lacking in the current sample. This process continues until no new (relevant) information can be found and further sampling becomes redundant – which is called saturation [ 1 , 15 ] . In other words: qualitative data collection finds its end point not a priori , but when the research team determines that saturation has been reached [ 29 , 30 ].

This is also the reason why most qualitative studies use deliberate instead of random sampling strategies. This is generally referred to as “ purposive sampling” , in which researchers pre-define which types of participants or cases they need to include so as to cover all variations that are expected to be of relevance, based on the literature, previous experience or theory (i.e. theoretical sampling) [ 14 , 20 ]. Other types of purposive sampling include (but are not limited to) maximum variation sampling, critical case sampling or extreme or deviant case sampling [ 2 ]. In the above EVT example, a purposive sample could include all relevant professional groups and/or all relevant stakeholders (patients, relatives) and/or all relevant times of observation (day, night and weekend shift).

Assessors of qualitative research should check whether the considerations underlying the sampling strategy were sound and whether or how researchers tried to adapt and improve their strategies in stepwise or cyclical approaches between data collection and analysis to achieve saturation [ 14 ].

Good qualitative research is iterative in nature, i.e. it goes back and forth between data collection and analysis, revising and improving the approach where necessary. One example of this are pilot interviews, where different aspects of the interview (especially the interview guide, but also, for example, the site of the interview or whether the interview can be audio-recorded) are tested with a small number of respondents, evaluated and revised [ 19 ]. In doing so, the interviewer learns which wording or types of questions work best, or which is the best length of an interview with patients who have trouble concentrating for an extended time. Of course, the same reasoning applies to observations or focus groups which can also be piloted.

Ideally, coding should be performed by at least two researchers, especially at the beginning of the coding process when a common approach must be defined, including the establishment of a useful coding list (or tree), and when a common meaning of individual codes must be established [ 23 ]. An initial sub-set or all transcripts can be coded independently by the coders and then compared and consolidated after regular discussions in the research team. This is to make sure that codes are applied consistently to the research data.

Member checking

Member checking, also called respondent validation , refers to the practice of checking back with study respondents to see if the research is in line with their views [ 14 , 27 ]. This can happen after data collection or analysis or when first results are available [ 23 ]. For example, interviewees can be provided with (summaries of) their transcripts and asked whether they believe this to be a complete representation of their views or whether they would like to clarify or elaborate on their responses [ 17 ]. Respondents’ feedback on these issues then becomes part of the data collection and analysis [ 27 ].

Stakeholder involvement

In those niches where qualitative approaches have been able to evolve and grow, a new trend has seen the inclusion of patients and their representatives not only as study participants (i.e. “members”, see above) but as consultants to and active participants in the broader research process [ 31 , 32 , 33 ]. The underlying assumption is that patients and other stakeholders hold unique perspectives and experiences that add value beyond their own single story, making the research more relevant and beneficial to researchers, study participants and (future) patients alike [ 34 , 35 ]. Using the example of patients on or nearing dialysis, a recent scoping review found that 80% of clinical research did not address the top 10 research priorities identified by patients and caregivers [ 32 , 36 ]. In this sense, the involvement of the relevant stakeholders, especially patients and relatives, is increasingly being seen as a quality indicator in and of itself.

How not to assess qualitative research

The above overview does not include certain items that are routine in assessments of quantitative research. What follows is a non-exhaustive, non-representative, experience-based list of the quantitative criteria often applied to the assessment of qualitative research, as well as an explanation of the limited usefulness of these endeavours.

Protocol adherence

Given the openness and flexibility of qualitative research, it should not be assessed by how well it adheres to pre-determined and fixed strategies – in other words: its rigidity. Instead, the assessor should look for signs of adaptation and refinement based on lessons learned from earlier steps in the research process.

Sample size

For the reasons explained above, qualitative research does not require specific sample sizes, nor does it require that the sample size be determined a priori [ 1 , 14 , 27 , 37 , 38 , 39 ]. Sample size can only be a useful quality indicator when related to the research purpose, the chosen methodology and the composition of the sample, i.e. who was included and why.

Randomisation

While some authors argue that randomisation can be used in qualitative research, this is not commonly the case, as neither its feasibility nor its necessity or usefulness has been convincingly established for qualitative research [ 13 , 27 ]. Relevant disadvantages include the negative impact of a too large sample size as well as the possibility (or probability) of selecting “ quiet, uncooperative or inarticulate individuals ” [ 17 ]. Qualitative studies do not use control groups, either.

Interrater reliability, variability and other “objectivity checks”

The concept of “interrater reliability” is sometimes used in qualitative research to assess to which extent the coding approach overlaps between the two co-coders. However, it is not clear what this measure tells us about the quality of the analysis [ 23 ]. This means that these scores can be included in qualitative research reports, preferably with some additional information on what the score means for the analysis, but it is not a requirement. Relatedly, it is not relevant for the quality or “objectivity” of qualitative research to separate those who recruited the study participants and collected and analysed the data. Experiences even show that it might be better to have the same person or team perform all of these tasks [ 20 ]. First, when researchers introduce themselves during recruitment this can enhance trust when the interview takes place days or weeks later with the same researcher. Second, when the audio-recording is transcribed for analysis, the researcher conducting the interviews will usually remember the interviewee and the specific interview situation during data analysis. This might be helpful in providing additional context information for interpretation of data, e.g. on whether something might have been meant as a joke [ 18 ].

Not being quantitative research

Being qualitative research instead of quantitative research should not be used as an assessment criterion if it is used irrespectively of the research problem at hand. Similarly, qualitative research should not be required to be combined with quantitative research per se – unless mixed methods research is judged as inherently better than single-method research. In this case, the same criterion should be applied for quantitative studies without a qualitative component.

The main take-away points of this paper are summarised in Table 1 . We aimed to show that, if conducted well, qualitative research can answer specific research questions that cannot to be adequately answered using (only) quantitative designs. Seeing qualitative and quantitative methods as equal will help us become more aware and critical of the “fit” between the research problem and our chosen methods: I can conduct an RCT to determine the reasons for transportation delays of acute stroke patients – but should I? It also provides us with a greater range of tools to tackle a greater range of research problems more appropriately and successfully, filling in the blind spots on one half of the methodological spectrum to better address the whole complexity of neurological research and practice.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Endovascular treatment

Randomised Controlled Trial

Standard Operating Procedure

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research

Philipsen, H., & Vernooij-Dassen, M. (2007). Kwalitatief onderzoek: nuttig, onmisbaar en uitdagend. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Qualitative research: useful, indispensable and challenging. In: Qualitative research: Practical methods for medical practice (pp. 5–12). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Chapter Google Scholar

Punch, K. F. (2013). Introduction to social research: Quantitative and qualitative approaches . London: Sage.

Kelly, J., Dwyer, J., Willis, E., & Pekarsky, B. (2014). Travelling to the city for hospital care: Access factors in country aboriginal patient journeys. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 22 (3), 109–113.

Article Google Scholar

Nilsen, P., Ståhl, C., Roback, K., & Cairney, P. (2013). Never the twain shall meet? - a comparison of implementation science and policy implementation research. Implementation Science, 8 (1), 1–12.

Howick J, Chalmers I, Glasziou, P., Greenhalgh, T., Heneghan, C., Liberati, A., Moschetti, I., Phillips, B., & Thornton, H. (2011). The 2011 Oxford CEBM evidence levels of evidence (introductory document) . Oxford Center for Evidence Based Medicine. https://www.cebm.net/2011/06/2011-oxford-cebm-levels-evidence-introductory-document/ .

Eakin, J. M. (2016). Educating critical qualitative health researchers in the land of the randomized controlled trial. Qualitative Inquiry, 22 (2), 107–118.

May, A., & Mathijssen, J. (2015). Alternatieven voor RCT bij de evaluatie van effectiviteit van interventies!? Eindrapportage. In Alternatives for RCTs in the evaluation of effectiveness of interventions!? Final report .

Google Scholar

Berwick, D. M. (2008). The science of improvement. Journal of the American Medical Association, 299 (10), 1182–1184.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Christ, T. W. (2014). Scientific-based research and randomized controlled trials, the “gold” standard? Alternative paradigms and mixed methodologies. Qualitative Inquiry, 20 (1), 72–80.

Lamont, T., Barber, N., Jd, P., Fulop, N., Garfield-Birkbeck, S., Lilford, R., Mear, L., Raine, R., & Fitzpatrick, R. (2016). New approaches to evaluating complex health and care systems. BMJ, 352:i154.

Drabble, S. J., & O’Cathain, A. (2015). Moving from Randomized Controlled Trials to Mixed Methods Intervention Evaluation. In S. Hesse-Biber & R. B. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research Inquiry (pp. 406–425). London: Oxford University Press.

Chambers, D. A., Glasgow, R. E., & Stange, K. C. (2013). The dynamic sustainability framework: Addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implementation Science : IS, 8 , 117.

Hak, T. (2007). Waarnemingsmethoden in kwalitatief onderzoek. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Observation methods in qualitative research] (pp. 13–25). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Russell, C. K., & Gregory, D. M. (2003). Evaluation of qualitative research studies. Evidence Based Nursing, 6 (2), 36–40.

Fossey, E., Harvey, C., McDermott, F., & Davidson, L. (2002). Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 36 , 717–732.

Yanow, D. (2000). Conducting interpretive policy analysis (Vol. 47). Thousand Oaks: Sage University Papers Series on Qualitative Research Methods.

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22 , 63–75.

van der Geest, S. (2006). Participeren in ziekte en zorg: meer over kwalitatief onderzoek. Huisarts en Wetenschap, 49 (4), 283–287.

Hijmans, E., & Kuyper, M. (2007). Het halfopen interview als onderzoeksmethode. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [The half-open interview as research method (pp. 43–51). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Jansen, H. (2007). Systematiek en toepassing van de kwalitatieve survey. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Systematics and implementation of the qualitative survey (pp. 27–41). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Pv, R., & Peremans, L. (2007). Exploreren met focusgroepgesprekken: de ‘stem’ van de groep onder de loep. In L. PLBJ & H. TCo (Eds.), Kwalitatief onderzoek: Praktische methoden voor de medische praktijk . [Exploring with focus group conversations: the “voice” of the group under the magnifying glass (pp. 53–64). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Carter, N., Bryant-Lukosius, D., DiCenso, A., Blythe, J., & Neville, A. J. (2014). The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41 (5), 545–547.

Boeije H: Analyseren in kwalitatief onderzoek: Denken en doen, [Analysis in qualitative research: Thinking and doing] vol. Den Haag Boom Lemma uitgevers; 2012.

Hunter, A., & Brewer, J. (2015). Designing Multimethod Research. In S. Hesse-Biber & R. B. Johnson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Multimethod and Mixed Methods Research Inquiry (pp. 185–205). London: Oxford University Press.

Archibald, M. M., Radil, A. I., Zhang, X., & Hanson, W. E. (2015). Current mixed methods practices in qualitative research: A content analysis of leading journals. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14 (2), 5–33.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Choosing a Mixed Methods Design. In Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research . Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2000). Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ, 320 (7226), 50–52.

O'Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine : Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 89 (9), 1245–1251.

Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality and Quantity, 52 (4), 1893–1907.

Moser, A., & Korstjens, I. (2018). Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. European Journal of General Practice, 24 (1), 9–18.

Marlett, N., Shklarov, S., Marshall, D., Santana, M. J., & Wasylak, T. (2015). Building new roles and relationships in research: A model of patient engagement research. Quality of Life Research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation, 24 (5), 1057–1067.

Demian, M. N., Lam, N. N., Mac-Way, F., Sapir-Pichhadze, R., & Fernandez, N. (2017). Opportunities for engaging patients in kidney research. Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease, 4 , 2054358117703070–2054358117703070.

Noyes, J., McLaughlin, L., Morgan, K., Roberts, A., Stephens, M., Bourne, J., Houlston, M., Houlston, J., Thomas, S., Rhys, R. G., et al. (2019). Designing a co-productive study to overcome known methodological challenges in organ donation research with bereaved family members. Health Expectations . 22(4):824–35.

Piil, K., Jarden, M., & Pii, K. H. (2019). Research agenda for life-threatening cancer. European Journal Cancer Care (Engl), 28 (1), e12935.

Hofmann, D., Ibrahim, F., Rose, D., Scott, D. L., Cope, A., Wykes, T., & Lempp, H. (2015). Expectations of new treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: Developing a patient-generated questionnaire. Health Expectations : an international journal of public participation in health care and health policy, 18 (5), 995–1008.

Jun, M., Manns, B., Laupacis, A., Manns, L., Rehal, B., Crowe, S., & Hemmelgarn, B. R. (2015). Assessing the extent to which current clinical research is consistent with patient priorities: A scoping review using a case study in patients on or nearing dialysis. Canadian Journal of Kidney Health and Disease, 2 , 35.

Elsie Baker, S., & Edwards, R. (2012). How many qualitative interviews is enough? In National Centre for Research Methods Review Paper . National Centre for Research Methods. http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/2273/4/how_many_interviews.pdf .

Sandelowski, M. (1995). Sample size in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 18 (2), 179–183.

Sim, J., Saunders, B., Waterfield, J., & Kingstone, T. (2018). Can sample size in qualitative research be determined a priori? International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 21 (5), 619–634.

Download references

Acknowledgements

no external funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Neurology, Heidelberg University Hospital, Im Neuenheimer Feld 400, 69120, Heidelberg, Germany

Loraine Busetto, Wolfgang Wick & Christoph Gumbinger

Clinical Cooperation Unit Neuro-Oncology, German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany

Wolfgang Wick

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

LB drafted the manuscript; WW and CG revised the manuscript; all authors approved the final versions.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Loraine Busetto .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Busetto, L., Wick, W. & Gumbinger, C. How to use and assess qualitative research methods. Neurol. Res. Pract. 2 , 14 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42466-020-00059-z

Download citation

Received : 30 January 2020

Accepted : 22 April 2020

Published : 27 May 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s42466-020-00059-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Qualitative research

- Mixed methods

- Quality assessment

Neurological Research and Practice

ISSN: 2524-3489

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 13 December 2018

Using qualitative Health Research methods to improve patient and public involvement and engagement in research

- Danielle E. Rolfe 1 ,

- Vivian R. Ramsden 2 ,

- Davina Banner 3 &

- Ian D. Graham 1

Research Involvement and Engagement volume 4 , Article number: 49 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

42k Accesses

57 Citations

23 Altmetric

Metrics details

Plain English summary

Patient engagement (or patient and public involvement) in health research is becoming a requirement for many health research funders, yet many researchers have little or no experience in engaging patients as partners as opposed to research subjects. Additionally, many patients have no experience providing input on the research design or acting as a decision-making partner on a research team. Several potential risks exist when patient engagement is done poorly, despite best intentions. Some of these risks are that: (1) patients’ involvement is merely tokenism (patients are involved but their suggestions have little influence on how research is conducted); (2) engaged patients do not represent the diversity of people affected by the research; and, (3) research outcomes lack relevance to patients’ lives and experiences.

Qualitative health research (the collection and systematic analysis of non-quantitative data about peoples’ experiences of health or illness and the healthcare system) offers several approaches that can help to mitigate these risks. Several qualitative health research methods, when done well, can help research teams to: (1) accurately incorporate patients’ perspectives and experiences into the design and conduct of research; (2) engage diverse patient perspectives; and, (3) treat patients as equal and ongoing partners on the research team.

This commentary presents several established qualitative health research methods that are relevant to patient engagement in research. The hope is that this paper will inspire readers to seek more information about qualitative health research, and consider how its established methods may help improve the quality and ethical conduct of patient engagement for health research.

Research funders in several countries have posited a new vision for research that involves patients and the public as co-applicants for the funding, and as collaborative partners in decision-making at various stages and/or throughout the research process. Patient engagement (or patient and public involvement) in health research is presented as a more democratic approach that leads to research that is relevant to the lives of the people affected by its outcomes. What is missing from the recent proliferation of resources and publications detailing the practical aspects of patient engagement is a recognition of how existing research methods can inform patient engagement initiatives. Qualitative health research, for example, has established methods of collecting and analyzing non-quantitative data about individuals’ and communities’ lived experiences with health, illness and/or the healthcare system. Included in the paradigm of qualitative health research is participatory health research, which offers approaches to partnering with individuals and communities to design and conduct research that addresses their needs and priorities.

The purpose of this commentary is to explore how qualitative health research methods can inform and support meaningful engagement with patients as partners. Specifically, this paper addresses issues of: rigour (how can patient engagement in research be done well?); representation (are the right patients being engaged?); and, reflexivity (is engagement being done in ways that are meaningful, ethical and equitable?). Various qualitative research methods are presented to increase the rigour found within patient engagement. Approaches to engage more diverse patient perspectives are presented to improve representation beyond the common practice of engaging only one or two patients. Reflexivity, or the practice of identifying and articulating how research processes and outcomes are constructed by the respective personal and professional experiences of researchers and patients, is presented to support the development of authentic, sustainable, equitable and meaningful engagement of patients as partners in health research.

Conclusions

Researchers will need to engage patients as stakeholders in order to satisfy the overlapping mandate in health policy, care and research for engaging patients as partners in decision-making. This paper presents several suggestions to ground patient engagement approaches in established research designs and methods.

Peer Review reports

Patient engagement (or patient and public involvement) in research involves partnering with ‘patients’ (a term more often used in Canada and the US, that is inclusive of individuals, caregivers, and/or members of the public) to facilitate research related to health or healthcare services. Rather than research subjects or participants, patients are engaged as partners in the research process. This partnership is intended to be meaningful and ongoing, from the outset of planning a research project, and/or at various stages throughout the research process. Engagement can include the involvement of patients in defining a research question, identifying appropriate outcomes and methods, collecting and interpreting data, and developing and delivering a knowledge translation strategy [ 1 ].

The concept of engaging non-researchers throughout the research process is not new to participatory health researchers, or integrated knowledge translation researchers, as the latter involves ongoing collaboration with clinicians, health planners and policy makers throughout the research process in order to generate new knowledge [ 2 , 3 ]. Patients, however, are less frequently included as partners on health research teams, or as knowledge users in integrated knowledge translation research teams compared to clinicians, healthcare managers and policy-makers, as these individuals are perceived as having “the authority to invoke change in the practice or policy setting.” (p.2) [ 2 ] Recent requirements for patient engagement by health research funders [ 4 , 5 , 6 ], ,and mandates by most healthcare planners and organizations to engage patients in healthcare improvement initiatives, suggest that it would be prudent for integrated knowledge translation (and indeed all) health researchers to begin engaging patients as knowledge users in many, if not all, of their research projects.

Training and tools for patient engagement are being developed and implemented in Canada via the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) Strategy for Patient Oriented Research (SPOR) initiative, in the US via Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), and very practical resources are already available from the UK’s more established INVOLVE Advisory Group [ 5 , 6 , 7 ]. What is seldom provided by these ‘get started’ guides, however, are rigorous methods and evidence-based approaches to engaging diverse patient perspectives, and ensuring that their experiences, values and advice are appropriately incorporated into the research process.

The purpose of this commentary is to stimulate readers’ further discussion and inquiry into qualitative health research methods as a means of fostering the more meaningfully engagement of patients as partners for research. Specifically, this paper will address issues of: rigour (how do we know that the interpretation of patients’ perspectives has been done well and is applicable to other patients?); representation (are multiple and diverse patient perspectives being sought?); and, reflexivity (is engagement being done ethically and equitably?). This commentary alone is insufficient to guide researchers and patient partners to use the methods presented as part of their patient engagement efforts. However, with increased understanding of these approaches and perhaps guidance from experienced qualitative health researchers, integrated knowledge translation and health researchers alike may be better prepared to engage patients in a meaningful way in research that has the potential to improve health and healthcare experiences and outcomes.

What can be learned from methods utilized in qualitative health research?

There is wide variation in researchers’ and healthcare providers’ openness to engaging patients [ 8 ]. Often, the patients that are engaged are a select group of individuals known to the research team, sometimes do not reflect the target population of the research, are involved at a consultative rather than a partnership level, and are more likely to be involved in the planning rather than the dissemination of research [ 9 , 10 , 11 ]. As a result, patient engagement can be seen as tokenistic and the antithesis of the intention of most patient engagement initiatives, which is to have patients’ diverse experiences and perspectives help to shape what and how research is done. The principles, values, and practices of qualitative health research (e.g., relativism, social equity, inductive reasoning) have rich epistemological traditions that align with the conceptual and practical spirit of patient engagement. It is beyond the scope of this commentary, however, to describe in detail the qualitative research paradigm, and readers are encouraged to gain greater knowledge of this topic via relevant courses and texts. Nevertheless, several qualitative research considerations and methods can be applied to the practice of patient engagement, and the following sections describe three of these: rigour, representation and reflexivity.

Rigour: Interpreting and incorporating patients’ experiences into the design and conduct of research

When patient engagement strategies go beyond the inclusion of a few patient partners on the research team, for example, by using focus groups, interviews, community forums, or other methods of seeking input from a broad range of patient perspectives, the diversity of patients’ experiences or perspectives may be a challenge to quickly draw conclusions from in order to make decisions about the study design. To make these decisions, members of the research team (which should include patient partners) may discuss what they heard about patients’ perspectives and suggestions, and then unsystematically incorporate these suggestions, or they may take a vote, try to achieve consensus, implement a Delphi technique [ 12 ], or use another approach designed specifically for patient engagement like the James Lind Alliance technique for priority setting [ 13 ]. Although the information gathered from patients is not data (and indeed would require ethical review to be used as such), a number of qualitative research practices designed to increase rigour can be employed to help ensure that the interpretation and incorporation of patients’ experiences and perspectives has been done systematically and could be reproduced [ 14 ]. These practices include member checking , dense description , and constant comparative analysis . To borrow key descriptors of rigour from qualitative research, these techniques improve “credibility” (i.e., accurate representations of patients’ experiences and preferences that are likely to be understood or recognized by other patients in similar situations – known in quantitative research as internal validity), and “transferability” (or the ability to apply what was found among a group of engaged patients to other patients in similar contexts – known in quantitative research as external validity) [ 15 ].

Member checking

Member checking in qualitative research involves “taking ideas back to the research participants for their confirmation” (p. 111) [ 16 ]. The objective of member checking is to ensure that a researcher’s interpretation of the data (whether a single interview with a participant, or after analyzing several interviews with participants) accurately reflects the participants’ intended meaning (in the case of a member check with a single participant about their interview), or their lived experience (in the case of sharing an overall finding about several individuals with one or more participants) [ 16 ]. For research involving patient engagement, member checking can be utilized to follow-up with patients who may have been engaged at one or only a few time points, or on an on-going basis with patient partners. A summary of what was understood and what decisions were made based on patients’ recommendations could be used to initiate this discussion and followed up with questions such as, “have I understood correctly what you intended to communicate to me?” or “do you see yourself or your experience(s) reflected in these findings or suggestions for the design of the study?”

Dense description

As with quantitative research, detailed information about qualitative research methods and study participants is needed to enable other researchers to understand the context and focus of the research and to establish how these findings relate more broadly. This helps researchers to not only potentially repeat the study, but to extend its findings to similar participants in similar contexts. Dense description provides details of the social, demographic and health profile of participants (e.g., gender, education, health conditions, etc.), as well as the setting and context of their experiences (i.e., where they live, what access to healthcare they have). In this way, dense description improves the transferability of study findings to similar individuals in similar situations [ 15 ]. To date, most studies involving patient engagement provide limited details about their engagement processes and who was engaged [ 17 ]. This omission may be done intentionally (e.g., to protect the privacy of engaged patients, particularly those with stigmatizing health conditions), or as a practical constraint such as publication word limits. Nonetheless, reporting of patient engagement using some aspects of dense description of participants (as appropriate), the ways that they were engaged, and recommendations that emanated from engaged patients can also contribute to greater transferability and understanding of how patient engagement influenced the design of a research study.

Constant comparative analysis

Constant comparative analysis is a method commonly used in grounded theory qualitative research [ 18 ]. Put simply, the understanding of a phenomenon or experience that a researcher acquires through engaging with participants is constantly redeveloped and refined based on subsequent participant interactions. This process of adapting to new information in order to make it more relevant is similar to processes used in rapid cycle evaluation during implementation research [ 19 ]. This method can be usefully adapted and applied to research involving ongoing collaboration and partnership with several engaged patient partners, and/or engagement strategies that seek the perspectives of many patients at various points in the research process. For example, if, in addition to having ongoing patient partners, a larger group of patients provides input and advice (e.g., a steering or advisory committee) at different stages in the research process, their input may result in multiple course corrections during the design and conduct of the research processes to incorporate their suggestions. These suggestions may result in refinement of earlier decisions made about study design or conduct, and as such, the research process becomes more iterative rather than linear. In this way, engaged patients and patient partners are able to provide their input and experience to improve each step of the research process from formulating an appropriate research question or objective, determining best approaches to conducting the research and sharing it with those most affected by the outcomes.

Representation: Gathering diverse perspectives to design relevant and appropriate research studies

The intention of engaging patients is to have their lived experience of health care or a health condition contribute to the optimization of a research project design [ 20 ]. Development of a meaningful and sustainable relationship with patient partners requires considerable time, a demonstrated commitment to partnership by both the patient partners and the researcher(s), resources to facilitate patient partners’ engagement, and often, an individual designated to support the development of this relationship [ 17 , 21 ]. This may lead some research teams to sustain this relationship with only one or two patients who are often previously known to the research team [ 17 ]. The limitation of this approach is that the experiences of these one or two individuals may not adequately reflect the diverse perspectives of patients that may be affected by the research or its outcomes. The notion of gaining ‘ the patient perspective’ from a single or only a few individuals has already been problematized [ 22 , 23 ]. To be sure, the engagement of a single patient is better than none at all, but the engagement of a broader and diverse population of patients should be considered to better inform the research design, and to help prevent further perpetuation of health disparities. Key issues to be considered include (1) how engagement can be made accessible to patients from diverse backgrounds, and (2) which engagement strategies (e.g., ranging from a community information forum to full partnership on the research team) are most appropriate to reach the target population [ 24 ].

Making engagement accessible

Expecting patient partner(s) to attend regular research team meetings held during working hours in a boardroom setting in a hospital, research institute or university limits the participation of many individuals. To support the participation and diversity of engaged patients, effort should be made to increase the accessibility and emotional safety of engagement initiatives [ 25 ]. A budget must be allocated for patient partners’ transportation, childcare or caregiving support, remuneration for time or time taken off work and, at the very least, covering expenses related to their engagement. Another consideration that is often made by qualitative health researchers is whether brief counselling support can be provided to patients should the sharing of their experiences result in emotional distress. There are some resources that can help with planning for costs [ 26 ], including an online cost calculator [ 27 ].

Engagement strategies

Patient partners can be coached to consider the needs and experiences of people unlike them, but there are other methods of engagement that can help to gain a more fulsome perspective of what is likely a diverse patient population that is the focus of the research study. In qualitative health research, this is known as purposeful or purposive sampling: finding people who can provide information-rich descriptions of the phenomenon under study [ 28 ]. Engagement may require different approaches (e.g., deliberative group processes, community forums, focus groups, and patient partners on the research team), at different times in the research process to reach different individuals or populations (e.g., marginalized patients, or patients or caregivers experiencing illnesses that inhibit their ability to maintain an ongoing relationship with the research team). Engagement strategies of different forms at different times may be required. For example, ongoing engagement may occur with patient partners who are members of the research team (e.g., co-applicants on a research grant), and intermittent engagement may be sought from other patients through other methods that may be more time-limited or accessible to a diverse population of patients (e.g., a one-time focus group, community forum, or ongoing online discussion) to address issues that may arise during various stages of the research or dissemination processes. The result of this approach is that patients are not only consulted or involved (one-time or low commitment methods), but are also members of the research team and have the ability to help make decisions about the research being undertaken.

Engagement can generate a wealth of information from very diverse perspectives. Each iteration of engagement may yield new information. Knowing when enough information has been gathered to make decisions with the research team (that includes patient partners) about how the research may be designed or conducted can be challenging. One approach from qualitative research that can be adapted for patient engagement initiatives is theoretical saturation [ 29 ], or “the point in analysis when…further data gathering and analysis add little new to the conceptualization, though variations can always be discovered.” (p. 263) [ 18 ]. That is, a one-time engagement strategy (e.g., a discussion with a single patient partner) may be insufficient to acquire the diverse perspectives of the individuals that will be affected by the research or its outcomes. Additional strategies (e.g., focus groups or interviews with several individuals) may be initiated until many patients identify similar issues or recommendations.

Engagement approaches should also consider: how patients are initially engaged (e.g., through known or new networks, posted notices, telephone or in-person recruitment) and whether involvement has been offered widely enough to garner multiple perspectives; how patients’ experiences are shared (e.g., community forums, formal meetings, individual or group discussions) and whether facilitation enables broad participation; and finally, how patients’ participation and experiences are incorporated into the research planning and design, with patients having equal decision-making capacity to other research team members. Several publications and tools are available that can help guide researchers who are new to processes of engaging patients in research [ 24 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ], but unfortunately few address how to evaluate the effectiveness of engagement [ 35 ].

Reflexivity: Ensuring meaningful and authentic engagement

In qualitative research, reflexivity is an ongoing process of “the researcher’s scrutiny of his or her research experience, decisions, and interpretations in ways that bring the researcher into the process and allow the reader to assess how and to what extent the researcher’s interests, positions, and assumptions influenced inquiry. A reflexive stance informs how the researcher conducts his or her research, relates to the research participants, and represents them in written reports,” (p.188–189) [ 16 ]. The concept of reflexivity can be applied to research involving patient engagement by continually and explicitly considering how decisions about the research study were made. All members of the research team must consider (and perhaps discuss): (1) how patient partners are invited to participate in research planning and decision-making; (2) how their input is received relative to other team members (i.e., do their suggestions garner the same respect as researchers’ or providers’?); and, (3) whether engaged patients or patient partners feel sufficiently safe, able and respected to share their experiences, preferences and recommendations with the research team.

Ideally, reflexivity becomes a practice within the research team and may be operationalized through regular check-ins with patients and researchers about their comfort in sharing their views, and whether they feel that their views have been considered and taken onboard. Power dynamics should also be considered during patient engagement initiatives. For example, reflecting on how community forums, focus groups or interviews are to be facilitated, including a consideration of who is at the table/who is not, who speaks/who does not, whose suggestions are implemented/whose are not? Reflexivity can be practiced through informal discussions, or using methods that may allow more candid responses by engaged patients (e.g., anonymous online survey or feedback forms). At the very least, if these practices were not conducted throughout the research process, the research team (including patient partners) should endeavor to reflect upon team dynamics and consider how these may have contributed to the research design or outcomes. For example, were physicians and researchers seen as experts and patients felt less welcome or able to share their personal experiences? Were patients only engaged by telephone rather than in-person and did this influence their ability to easily engage in decision-making? Reflexive practices may be usefully supplemented by formal evaluation of the process of patient engagement from the perspective of patients and other research team members [ 36 , 37 ], and some tools are available to do this [ 35 ].

A note about language

One way to address the team dynamic between researchers, professional knowledge users (such as clinicians or health policy planners) and patients is to consider the language used to engage with patients in the planning of patient engagement strategies. That is, the term ‘patient engagement’ is a construction of an individual’s identity that exists only within the healthcare setting, and in the context of a patient-provider dynamic. This term does not consider how people make decisions about their health and healthcare within a broader context of their family, community, and culture [ 22 , 38 ]. This may be why research communities in some countries (e.g., the United Kingdom) use the term ‘patient and public involvement’. Additionally, research that involves communities defined by geography, shared experiences, cultural or ethnic identity, as is the case with participatory health research, may refer to ‘community engagement.’ Regardless of the term used, partnerships with patients, the public, or with communities need to be conceived instead as person-to-person interactions between researchers and individuals who are most affected by the research. Discussions with engaged patients should be conducted early on to determine how to best describe their role on the team or during engagement initiatives (e.g., as patient partners, community members, or people with lived experience).

Tokenism is the “difference between…the empty ritual of participation and having the real power needed to affect the outcome,” (p.2) [ 39 ]. Ongoing reflection on the power dynamic between researchers and engaged patients, a central tenet of critical qualitative health research [ 40 , 41 ], can increase the likelihood that engagement involves equitable processes and will result in meaningful engagement experiences by patients rather than tokenism [ 36 , 42 ]. Patient engagement initiatives should strive for “partnership” amongst all team members, and not just reflect a patient-clinician or researcher-subject dynamic [ 43 ]. To develop meaningful, authentic and sustainable relationships with engaged patients, methods used for participatory, action or community-based research (approaches that fall under the paradigm of qualitative inquiry) provide detailed experiential guidance [ 44 ]. For example, a realist review of community-based participatory research projects reported that gaining and maintaining trust with patient or community partners, although time-intensive, is foundational to equitable and sustainable partnerships that benefit communities and individuals [ 45 , 46 ]. Additionally, Chapter Nine of the Canadian Tri-Council Policy Statement on Research involving Humans, which has to date been applied to research involving First Nations, Inuit and, Métis Peoples in Canada [ 47 ], provides useful information and direction that can be applied to working with patient partners on research [ 48 ].