Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Religion in India: Tolerance and Segregation

- 4. Attitudes about caste

Table of Contents

- The dimensions of Hindu nationalism in India

- India’s Muslims express pride in being Indian while identifying communal tensions, desiring segregation

- Muslims, Hindus diverge over legacy of Partition

- Religious conversion in India

- Religion very important across India’s religious groups

- Near-universal belief in God, but wide variation in how God is perceived

- Across India’s religious groups, widespread sharing of beliefs, practices, values

- Religious identity in India: Hindus divided on whether belief in God is required to be a Hindu, but most say eating beef is disqualifying

- Sikhs are proud to be Punjabi and Indian

- 1. Religious freedom, discrimination and communal relations

- 2. Diversity and pluralism

- 3. Religious segregation

- 5. Religious identity

- 6. Nationalism and politics

- 7. Religious practices

- 8. Religion, family and children

- 9. Religious clothing and personal appearance

- 10. Religion and food

- 11. Religious beliefs

- 12. Beliefs about God

- Acknowledgments

- Appendix A: Methodology

- Appendix B: Index of religious segregation

The caste system has existed in some form in India for at least 3,000 years . It is a social hierarchy passed down through families, and it can dictate the professions a person can work in as well as aspects of their social lives, including whom they can marry. While the caste system originally was for Hindus, nearly all Indians today identify with a caste, regardless of their religion.

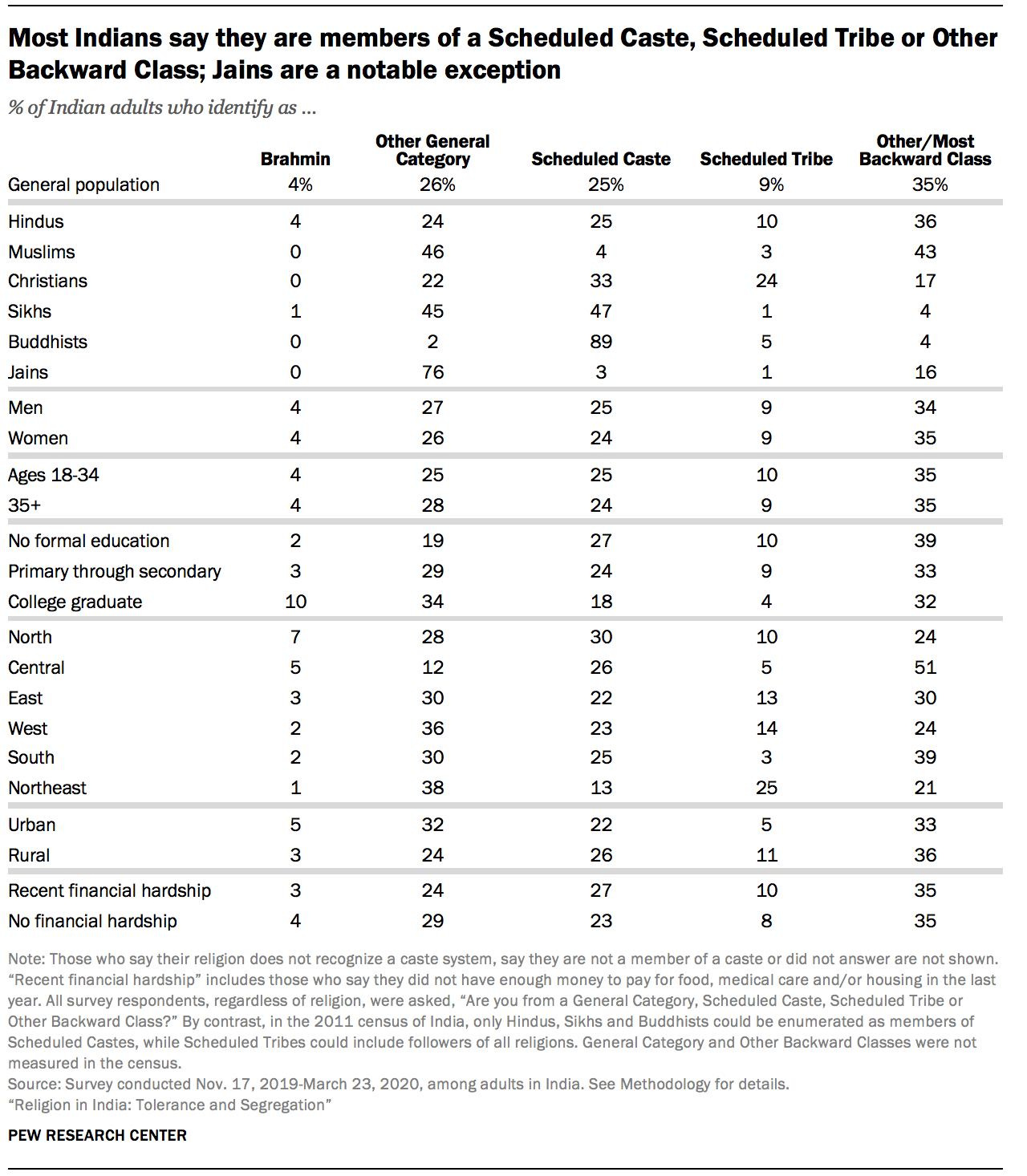

The survey finds that three-in-ten Indians (30%) identify themselves as members of General Category castes, a broad grouping at the top of India’s caste system that includes numerous hierarchies and sub-hierarchies. The highest caste within the General Category is Brahmin, historically the priests and other religious leaders who also served as educators. Just 4% of Indians today identify as Brahmin.

Most Indians say they are outside this General Category group, describing themselves as members of Scheduled Castes (often known as Dalits, or historically by the pejorative term “untouchables”), Scheduled Tribes or Other Backward Classes (including a small percentage who say they are part of Most Backward Classes).

Hindus mirror the general public in their caste composition. Meanwhile, an overwhelming majority of Buddhists say they are Dalits, while about three-quarters of Jains identify as members of General Category castes. Muslims and Sikhs – like Jains – are more likely than Hindus to belong to General Category castes. And about a quarter of Christians belong to Scheduled Tribes, a far larger share than among any other religious community.

Caste segregation remains prevalent in India. For example, a substantial share of Brahmins say they would not be willing to accept a person who belongs to a Scheduled Caste as a neighbor. But most Indians do not feel there is a lot of caste discrimination in the country, and two-thirds of those who identify with Scheduled Castes or Tribes say there is not widespread discrimination against their respective groups. This feeling may reflect personal experience: 82% of Indians say they have not personally faced discrimination based on their caste in the year prior to taking the survey.

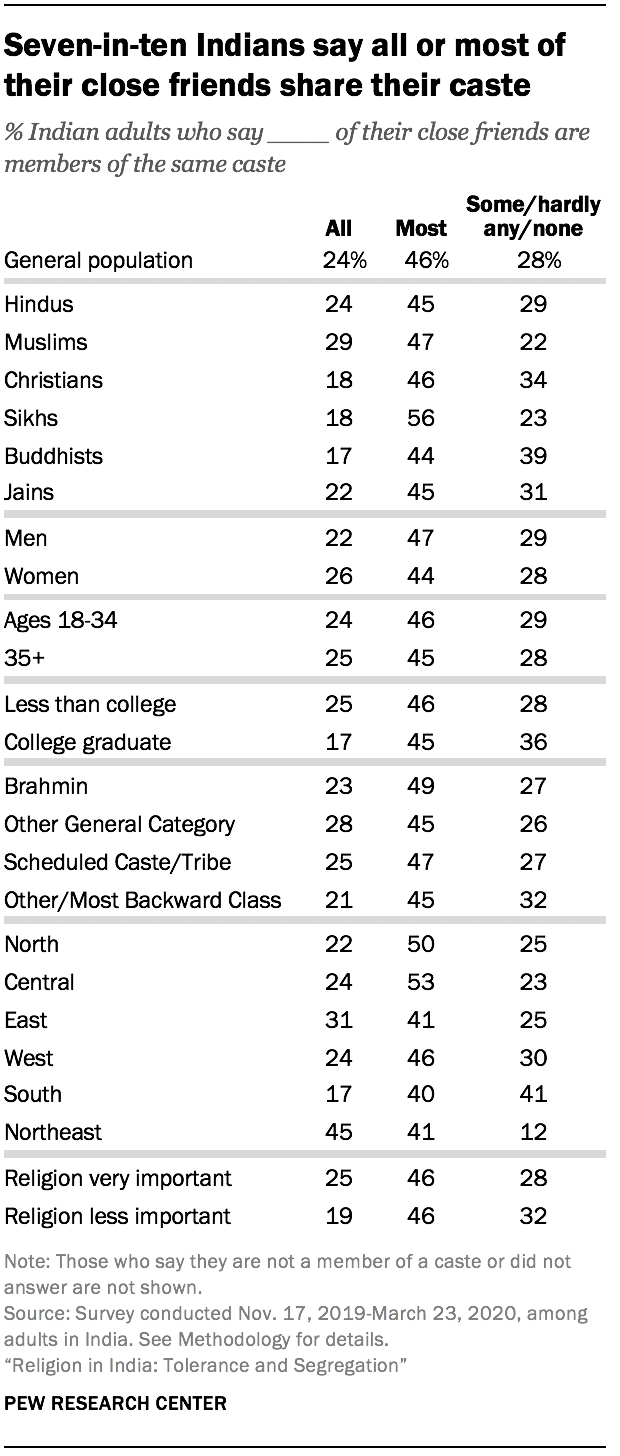

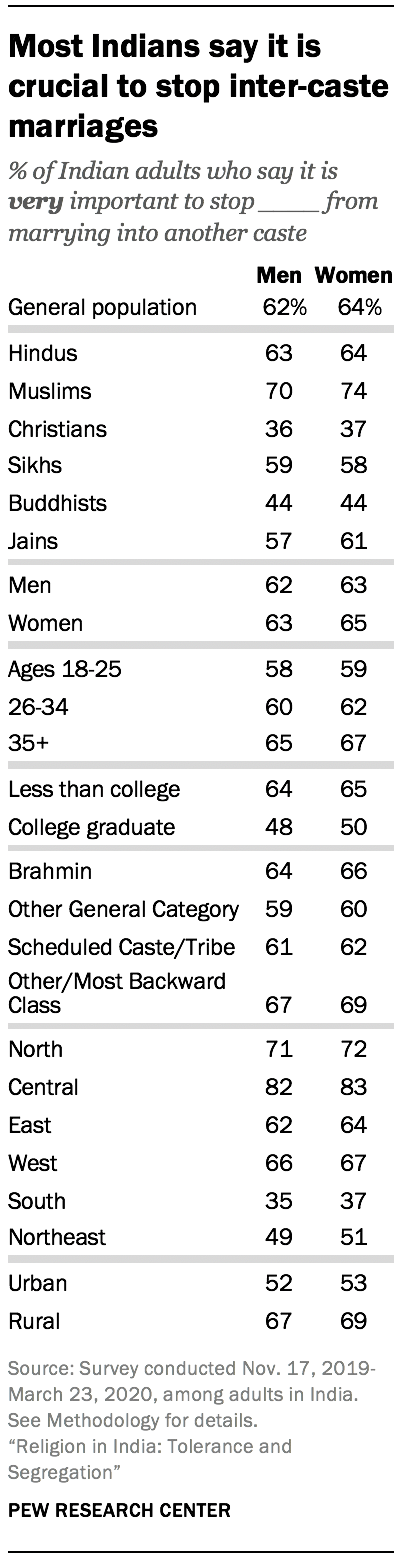

Still, Indians conduct their social lives largely within caste hierarchies. A majority of Indians say that their close friends are mostly members of their own caste, including roughly one-quarter (24%) who say all their close friends are from their caste. And most people say it is very important to stop both men and women in their community from marrying into other castes, although this view varies widely by region. For example, roughly eight-in-ten Indians in the Central region (82%) say it is very important to stop inter-caste marriages for men, compared with just 35% in the South who feel strongly about stopping such marriages.

India’s religious groups vary in their caste composition

Most Indians (68%) identify themselves as members of lower castes, including 34% who are members of either Scheduled Castes (SCs) or Scheduled Tribes (STs) and 35% who are members of Other Backward Classes (OBCs) or Most Backward Classes. Three-in-ten Indians identify themselves as belonging to General Category castes, including 4% who say they are Brahmin, traditionally the priestly caste. 12

Hindu caste distribution roughly mirrors that of the population overall, but other religions differ considerably. For example, a majority of Jains (76%) are members of General Category castes, while nearly nine-in-ten Buddhists (89%) are Dalits. Muslims disproportionately identify with non-Brahmin General Castes (46%) or Other/Most Backward Classes (43%).

Caste classification is in part based on economic hierarchy, which continues today to some extent. Highly educated Indians are more likely than those with less education to be in the General Category, while those with no education are most likely to identify as OBC.

But financial hardship isn’t strongly correlated with caste identification. Respondents who say they were unable to afford food, housing or medical care at some point in the last year are only slightly more likely than others to say they are Scheduled Caste/Tribe (37% vs. 31%), and slightly less likely to say they are from General Category castes (27% vs. 33%).

The Central region of India stands out from other regions for having significantly more Indians who are members of Other Backward Classes or Most Backward Classes (51%) and the fewest from the General Category (17%). Within the Central region, a majority of the population in the state of Uttar Pradesh (57%) identifies as belonging to Other or Most Backward Classes.

Indians in lower castes largely do not perceive widespread discrimination against their groups

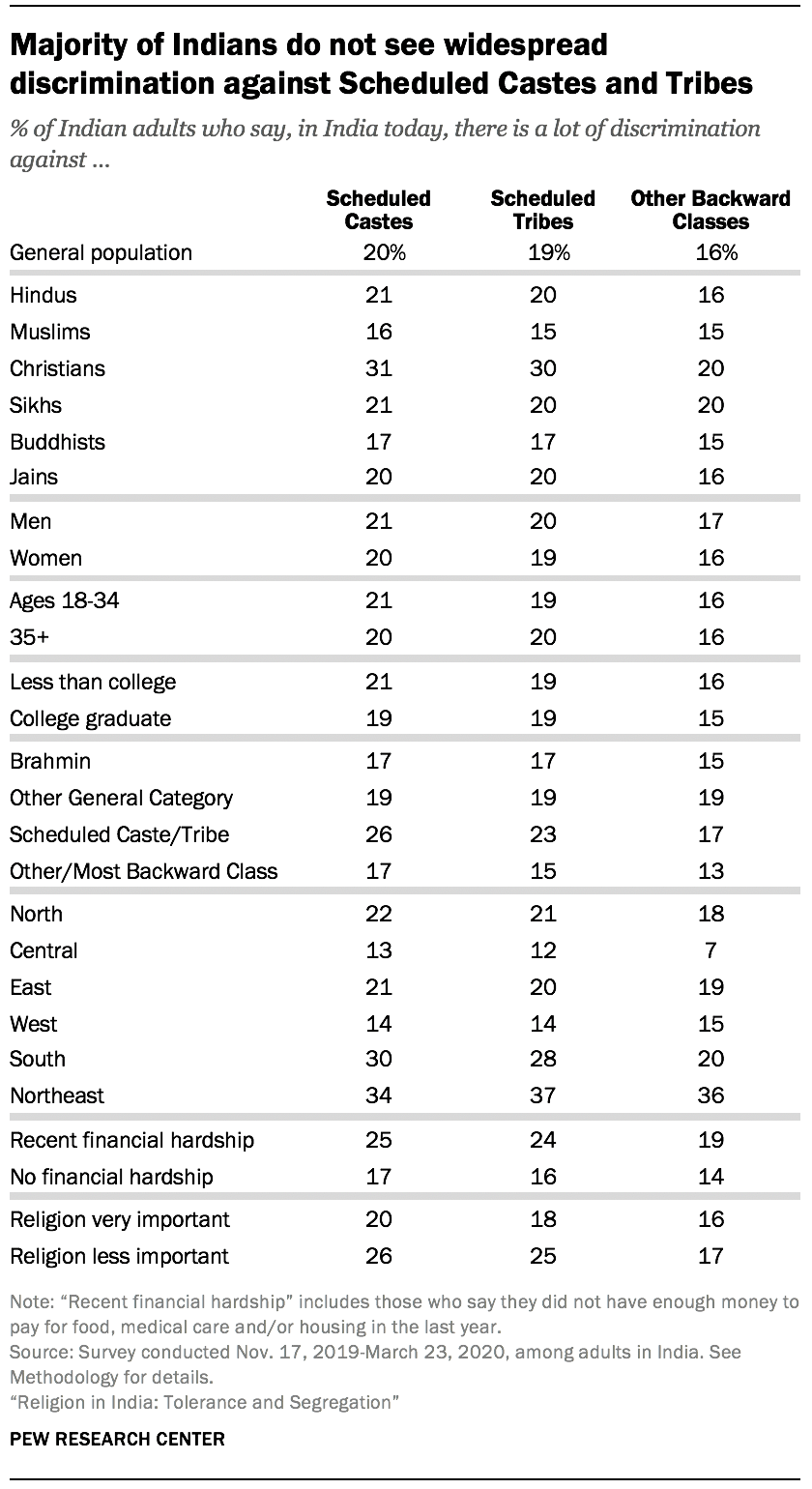

When asked if there is or is not “a lot of discrimination” against Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Other Backward Classes in India, most people say there isn’t a lot of caste discrimination. Fewer than one-quarter of Indians say they see evidence of widespread discrimination against Scheduled Castes (20%), Scheduled Tribes (19%) or Other Backward Classes (16%).

Generally, people belonging to lower castes share the perception that there isn’t widespread caste discrimination in India. For instance, just 13% of those who identify with OBCs say there is a lot of discrimination against Backward Classes. Members of Scheduled Castes and Tribes are slightly more likely than members of other castes to say there is a lot of caste discrimination against their groups – but, still, only about a quarter take this position.

Christians are more likely than other religious groups to say there is a lot of discrimination against Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes in India: About three-in-ten Christians say each group faces widespread discrimination, compared with about one-in-five or fewer among Hindus and other groups.

At least three-in-ten Indians in the Northeast and the South say there is a lot of discrimination against Scheduled Castes, although similar shares in the Northeast decline to answer these questions. Just 13% in the Central region say Scheduled Castes face widespread discrimination, and 7% say the same about OBCs.

Highly religious Indians – that is, those who say religion is very important in their lives – tend to see less evidence of discrimination against Scheduled Castes and Tribes. Meanwhile, those who have experienced recent financial hardship are more inclined to see widespread caste discrimination.

Most Indians do not have recent experience with caste discrimination

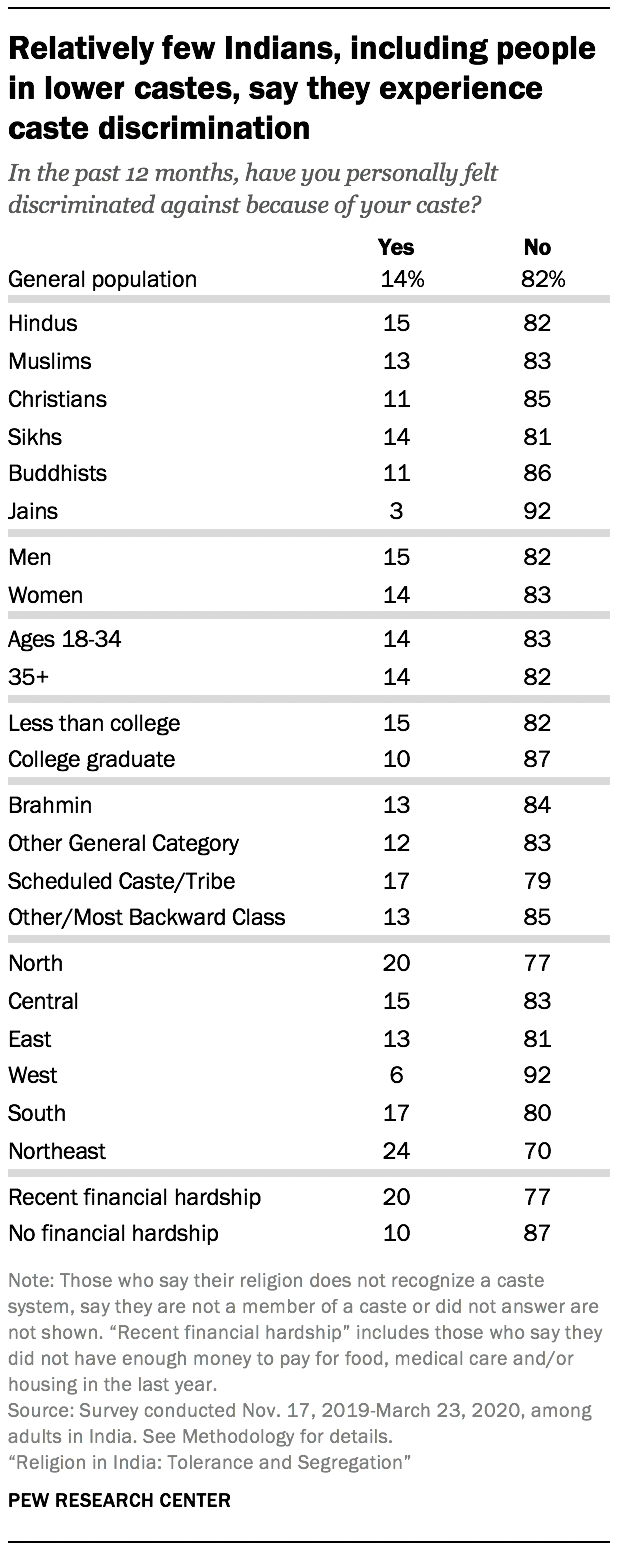

Not only do most Indians say that lower castes do not experience a lot of discrimination, but a strong majority (82%) say they have not personally felt caste discrimination in the past 12 months. While members of Scheduled Castes and Tribes are slightly more likely than members of other castes to say they have personally faced caste-based discrimination, fewer than one-in-five (17%) say they have experienced this in the last 12 months.

But caste-based discrimination is more commonly reported in some parts of the country. In the Northeast, for example, 38% of respondents who belong to Scheduled Castes say they have experienced discrimination because of their caste in the last 12 months, compared with 14% among members of Scheduled Castes in Eastern India.

Jains, the vast majority of whom are members of General Category castes, are less likely than other religious groups to say they have personally faced caste discrimination (3%). Meanwhile, Indians who indicate they have faced recent financial hardship are more likely than those who have not faced such hardship to report caste discrimination in the last year (20% vs. 10%).

Most Indians OK with Scheduled Caste neighbors

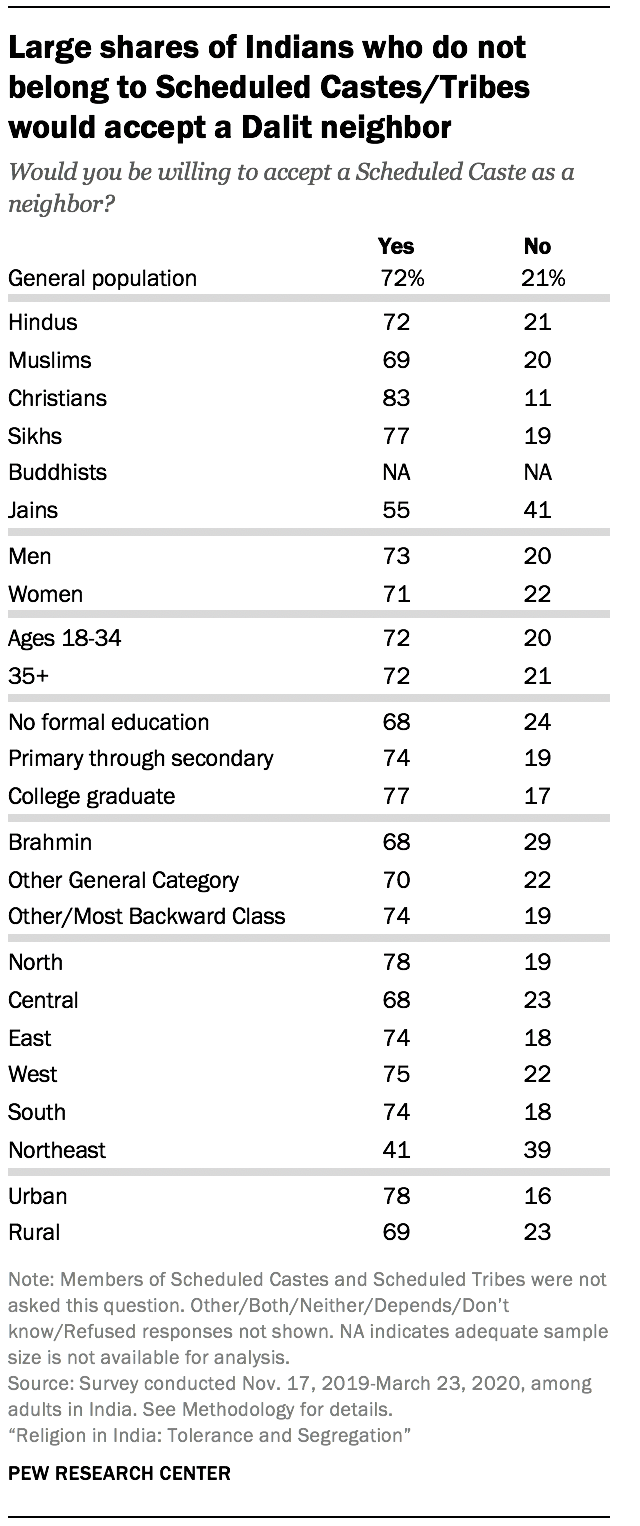

The vast majority of Indian adults say they would be willing to accept members of Scheduled Castes as neighbors. (This question was asked only of people who did not identify as members of Scheduled Castes or Scheduled Tribes.)

Among those who received the question, large majorities of Christians (83%) and Sikhs (77%) say they would accept Dalit neighbors. But a substantial portion of Jains, most of whom identify as belonging to General Category castes, feel differently; about four-in-ten Jains (41%) say that they would not be willing to accept Dalits as neighbors. (Because more than nine-in-ten Buddhists say they are members of Scheduled Castes or Scheduled Tribes, not enough Buddhists were asked this question to allow for separate analysis of their answers.)

About three-in-ten Brahmins (29%) say they would not be willing to accept members of Scheduled Castes as neighbors.

In most regions, at least two-thirds of people express willingness to accept Scheduled Caste neighbors. The Northeast, however, stands out, with roughly equal shares saying they would (41%) or would not (39%) be willing to accept Dalits as neighbors, although this region also has the highest share of respondents – 20% – who gave an unclear answer or declined to answer the question.

Indians who live in urban areas (78%) are more likely than rural Indians (69%) to say they would be willing to accept Scheduled Caste neighbors. And Indians with more education also are more likely to accept Dalit neighbors. Fully 77% of those with a college degree say they would be fine with neighbors from Scheduled Castes, while 68% of Indians with no formal education say the same.

Politically, those who have a favorable opinion of the BJP are somewhat less likely than those who have an unfavorable opinion of India’s ruling party to say they would accept Dalits as neighbors, although there is widespread acceptance across both groups (71% vs. 77%).

Indians generally do not have many close friends in different castes

Indians may be comfortable living in the same neighborhoods as people of different castes, but they tend to make close friends within their own caste. About one-quarter (24%) of Indians say all their close friends belong to their caste, and 46% say most of their friends are from their caste.

About three-quarters of Muslims and Sikhs say that all or most of their friends share their caste (76% and 74%, respectively). Christians and Buddhists – who disproportionately belong to lower castes – tend to have somewhat more mixed friend circles. Nearly four-in-ten Buddhists (39%) and a third of Christians (34%) say “some,” “hardly any” or “none” of their close friends share their caste background.

Members of OBCs are also somewhat more likely than other castes to have a mixed friend circle. About one-third of OBCs (32%) say no more than “some” of their friends are members of their caste, compared with roughly one-quarter of all other castes who say this.

Women, Indian adults without a college education and those who say religion is very important in their lives are more likely to say that all their close friends are of the same caste as them. And, regionally, 45% of Indians in the Northeast say all their friends are part of their caste, while in the South, fewer than one-in-five (17%) say the same.

Large shares of Indians say men, women should be stopped from marrying outside of their caste

As another measure of caste segregation, the survey asked respondents whether it is very important, somewhat important, not too important or not at all important to stop men and women in their community from marrying into another caste. Generally, Indians feel it is equally important to stop both men and women from marrying outside of their caste. Strong majorities of Indians say it is at least “somewhat” important to stop men (79%) and women (80%) from marrying into another caste, including at least six-in-ten who say it is “very” important to stop this from happening regardless of gender (62% for men and 64% for women).

Majorities of all the major caste groups say it is very important to prevent inter-caste marriages. Differences by religion are starker. While majorities of Hindus (64%) and Muslims (74%) say it is very important to prevent women from marrying across caste lines, fewer than half of Christians and Buddhists take that position.

Among Indians overall, those who say religion is very important in their lives are significantly more likely to feel it is necessary to stop members of their community from marrying into different castes. Two-thirds of Indian adults who say religion is very important to them (68%) also say it is very important to stop women from marrying into another caste; by contrast, among those who say religion is less important in their lives, 39% express the same view.

Regionally, in the Central part of the country, at least eight-in-ten adults say it is very important to stop both men and women from marrying members of different castes. By contrast, fewer people in the South (just over one-third) say stopping inter-caste marriage is a high priority. And those who live in rural areas of India are significantly more likely than urban dwellers to say it is very important to stop these marriages.

Older Indians and those without a college degree are more likely to oppose inter-caste marriage. And respondents with a favorable view of the BJP also are much more likely than others to oppose such marriages. For example, among Hindus, 69% of those who have a favorable view of BJP say it is very important to stop women in their community from marrying across caste lines, compared with 54% among those who have an unfavorable view of the party.

CORRECTION (August 2021): A previous version of this chapter contained an incorrect figure. The share of Indians who identify themselves as members of lower castes is 68%, not 69%.

- All survey respondents, regardless of religion, were asked, “Are you from a General Category, Scheduled Caste, Scheduled Tribe or Other Backward Class?” By contrast, in the 2011 census of India, only Hindus, Sikhs and Buddhists could be enumerated as members of Scheduled Castes, while Scheduled Tribes could include followers of all religions. General Category and Other Backward Classes were not measured in the census. A detailed analysis of differences between 2011 census data on caste and survey data can be found here . ↩

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Beliefs & Practices

- Christianity

- International Political Values

- International Religious Freedom & Restrictions

- Interreligious Relations

- Other Religions

- Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures Project

- Religious Characteristics of Demographic Groups

- Religious Identity & Affiliation

- Religiously Unaffiliated

- Size & Demographic Characteristics of Religious Groups

How common is religious fasting in the United States?

8 facts about atheists, spirituality among americans, how people in south and southeast asia view religious diversity and pluralism, religion among asian americans, most popular, report materials.

- Questionnaire

- Overview (Hindi)

- இந்தியாவில் மதம்: சகிப்புத்தன்மையும் தனிப்படுத்துதலும்

- भारत में धर्म: सहिष्णुता और अलगाव

- ভারতে ধর্ম: সহনশীলতা এবং পৃথকীকরণ

- भारतातील धर्म : सहिष्णुता आणि विलग्नता

- Related: Religious Composition of India

- How Pew Research Center Conducted Its India Survey

- Questionnaire: Show Cards

- India Survey Dataset

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

- Next Article

An Unwritten Grammar

Education and employment gaps, the persistence of caste, the mirage of equality, a march for independence, how india’s caste inequality has persisted—and deepened in the pandemic.

Ashwini Deshpande is a professor of economics and the founding director of the Centre for Economic Data and Analysis at Ashoka University, India. Parts of this essay are adapted from an online piece by the author published in December 2020 by IAI News .

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Guest Access

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Ashwini Deshpande; How India’s Caste Inequality Has Persisted—and Deepened in the Pandemic. Current History 1 April 2021; 120 (825): 127–132. doi: https://doi.org/10.1525/curh.2021.120.825.127

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

The economic impact of COVID-19 has been much harder on those at the bottom of the caste ladder in India, reflecting the persistence of a system of social stigmatization that many Indians believe is a thing of the past. Untouchability has been outlawed since 1947, and an affirmative action program has lowered some barriers for stigmatized caste groups. But during the pandemic, members of lower castes suffered heavier job losses due to their higher representation in precarious daily wage jobs and their lower levels of education. Lower caste families are less able to help their children with remote learning, which threatens to worsen labor market inequality in India. But Dalits, at the bottom of the caste ladder, have recently.

“The economic distress resulting from India’s pandemic response is intensifying preexisting structures of disadvantage based on social identity.”

In his 2017 book The Great Leveler , Austrian economic historian Walter Scheidel argues that throughout human history, four types of catastrophic event have led to greater economic equality: pandemics, wars, revolutions, and state collapses. In Scheidel’s analysis, these upheavals cause a surge in excess mortality that raises the price of labor, leading to declines in inequality. The validity of Scheidel’s argument for the current pandemic can only be assessed after it is over. But some have already described COVID-19 as a leveler in similar, if looser, terms. They argue that the disease can strike anyone, and that the resultant slowdown of economic activity has led to widespread job losses and economic hardships across the range of income and occupational distributions.

However, evidence from several parts of the world indicates that these assumptions are incorrect. The incidence of the disease is not class-neutral: poorer and economically vulnerable populations are more likely to contract the virus, as well as to die from it. Nor are the pandemic’s economic impacts neutral with respect to social identity. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have found that racial and ethnic minority groups are at greater risk of getting sick, having more severe complications, and dying. The groups that are more vulnerable to the disease are also unequally affected by the unintended economic, social, and secondary health consequences of COVID-19 mitigation strategies, such as lockdowns and social distancing.

This is true globally, and the story in India is no different. Since data on the incidence of the disease in India is not available by social group categories of caste and religion, it is impossible to assess which groups are at greater risk of mortality. But there is evidence that the economic impact of the pandemic has not been uniform across social groups.

A key element of the early pandemic control strategy adopted by most countries was to shut down economic and social activity. India’s nationwide lockdown started in the last week of March 2020, with only a few hours’ warning—resulting in a last-minute scramble to stock up on provisions. Even though the initial announcement was for 21 days, there was massive uncertainty about how long it would actually last. For the first month, the lockdown was among the strictest in the world, with a near-complete suspension of all economic activity.

The lockdown proceeded through four phases over 68 days. On June 1, 2020, the process of “unlocking” the economy started, and restrictions were gradually removed from various economic and social activities, based on the severity of COVID-19 incidence in different areas. In February 2021, at the time of writing, scheduled international flights remain suspended, university teaching is online, and office work is being conducted with a mix of online and on-site methods; but factories and most service establishments are open, apart from gyms, pools, and cinemas in some places.

My ongoing work with fellow economist Rajesh Ramachandran, using national-level large data sets, shows that the lockdown affected the marginalized, stigmatized group of lower-ranked castes much more severely than the higher-ranked castes. Thus, the COVID-19 pandemic has not proved to be a great leveler in India; in fact, it has worsened labor market inequality among caste groups.

In India, the finding that the economic impact of the pandemic-induced slowdown has been harsher for those at the bottom of the caste ladder is largely met with incredulity. For international readers who associate India strongly with the caste system, this disbelief might appear surprising. But large segments of the Indian population either are genuinely convinced that caste inequalities are not systemic or structural, or are persuaded by the Hindu right’s denunciations of any discussion of caste inequality as an attempt to break a mythical or presumed Hindu unity. There is widespread support for the idea that contemporary gaps are either sporadic or just a hangover from the past, and certainly should not be discussed and analyzed candidly.

This essay juxtaposes the findings of the caste-differentiated economic impacts of the pandemic with the context of the longer-term trend of caste inequality in India. By summarizing the new reality and the contemporary grammar of the caste system, I hope to show why the pandemic has deepened the preexisting fault lines of the caste system.

Formerly untouchable castes are still among the most marginalized and stigmatized groups.

Some readers might imagine that Indian castes are racial divisions, since American journalist Isabel Wilkerson has described US structural or systemic racism as a caste system in her bestselling 2020 book Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents . That would be incorrect. This is not a mere semantic quibble; an accurate understanding of caste divisions is essential to working out appropriate policy responses.

Despite the caste system’s appearance of being fixed in a timeless state, there have been important changes over the centuries in the manifestation and grammar of caste. In its contemporary version, India’s caste system consists of several thousand groups, known as jatis . This is not a binary division between “high” and “low” groups, though if one were to take a binary view of the caste system (as important anti-caste thinkers and social reformers such as Jotiba Phule advocated in the nineteenth century for the sake of subaltern unity), the latter groups would collectively form the majority, not a minority of low castes similar to Wilkerson’s characterization of the American situation.

The precise number of jatis is not known with certainty. Although the system is clearly hierarchical, and there is no ambiguity about higher-ranking jatis, the precise contours of the hierarchy vary from state to state: jati is a regional category, not a national one. Typically the two ends of the spectrum are clearly identified; there is a definite local understanding of which jatis are dominant and which are subordinate. But a jati that is dominant in one state or region might not be dominant in another one. For example, Jats are powerful in the northern state of Haryana, but less so in neighboring Rajasthan.

A key element that defines the status hierarchy is the notion of ritual purity. In the scale of ritual purity, Brahmins rank the highest everywhere in the country. Correspondingly, jatis whose traditional occupations are considered ritually impure are the lowest in the hierarchy everywhere.

The latter occupations have included scavenging, dealing with dead animals (butchery) or dead bodies (cremation), leather work, and even midwifery. Before India attained independence in 1947, members of these jatis were considered “untouchable”—touching them, seeing them, or even seeing their shadows was considered polluting for everyone else. Thus, these groups were ostracized and subjected to severe social restrictions. They were forced to live in separate hamlets outside villages, and were barred from upper-caste Hindu homes, temples, and sources of water. They were known as the ati-shudras , the lowest of the low.

Untouchability has been abolished since India won independence from British rule in 1947 and breaches of the ban are punishable by law. The Indian Constitution guarantees equality to all citizens regardless of caste, religion, gender, or any other social identity. Nonetheless, members of the formerly untouchable castes are still among the most marginalized and stigmatized groups in the country, even though they are entitled to preferential affirmative action in the form of quotas in government-funded higher educational institutions and public sector jobs.

The affirmative action program, known as the “reservations” system, has allowed members of the stigmatized caste groups to enter positions to which it would have been difficult for them to gain access otherwise. There are also electoral quotas at all levels of government: the rise of politicians and political parties belonging to the lower-ranked caste groups has been termed “India’s silent revolution.”

Since these castes are listed in a government schedule, they are lumped together in the omnibus administrative category of Scheduled Castes (SCs). Whereas SC is an administrative term for the purpose of affirmative action, members of this group have claimed “Dalit” as a term of identity and pride. (The word comes from Sanskrit and means “the oppressed.”) There is an analogous category of Scheduled Tribes (ST), who are also referred to as Adivasi (original inhabitants).

A third category of castes and communities identified for affirmative action is Other Backward Classes (OBCs), a large and heterogeneous collection of groups that rank low in the socioeconomic hierarchy but were not considered untouchables. Despite the fact that landowning and locally dominant groups have managed to find their way into this legal category (possibly to benefit from reservations or quotas), indicators show that the average standard of living for OBCs is still below that of the Hindu upper castes.

For quantitative assessment of caste inequality, data are available for the broad categories of Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, OBCs, and Others (everyone else). Any three- or four-way comparison understates the actual extent of caste inequality, since we cannot isolate, in the data, outcomes of jatis at the top end of the “Others” spectrum. But when we focus only on Hindus, “Others” makes a good proxy for the upper (ranked) castes. The broad hierarchy of the caste system thus consists of Hindu upper castes at the top, OBCs in the middle, and Scheduled Castes, or Dalits (along with STs or Adivasis), at the bottom.

A disclaimer before proceeding further: the use of the terms “lower (ranked)” and “upper (ranked)” is intended to reflect the hierarchy found in the reality on the ground. It is not, and should not be read as, an endorsement of caste hierarchy.

In research examining the evolution of caste inequality in India, Rajesh Ramachandran and I have found that caste gaps in basic educational attainment (up to the secondary school level) have narrowed over the past few decades. However, in higher education—which is what matters for getting good jobs—the gaps have increased over time. Younger cohorts of OBCs have moved closer to the upper castes, but the gaps between Dalits and Adivasis on the one hand and Hindu upper castes on the other have widened in the pursuit of higher education and white-collar jobs.

Adult life course disparities among caste groups seem to originate in early childhood malnourishment, which perpetuates a vicious cycle of disadvantage for Dalits and Adivasis. Due to caste gaps in nutrition, children from the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes are 40 percent more likely to be stunted than children belonging to the upper castes. This has long-term implications for educational and cognitive development.

COVID-19 struck in this context, and appears to have deepened the existing caste fault lines. We have found that the labor market or employment effects of the pandemic have been much more severe for the more disadvantaged groups—the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, and the OBCs. Their early job losses—during the first month of the strictest lockdown—were three and two times higher, respectively, than Hindu upper castes experienced.

Our results indicate that the heavier job losses among Scheduled Castes are accounted for by two main factors: their higher representation in precarious, vulnerable daily wage jobs, and their lower levels of education. Meanwhile, caste differences are minimal (though not completely eliminated) among the better-off workers—those who have more than 12 years of schooling and are not engaged in daily wage jobs.

The current pandemic is likely to exacerbate educational differences. Data from another nationally representative survey, the India Human Development Survey for 2011–12, show that 51 percent of Scheduled Caste households include adult women who have zero years of education—who are illiterate—and 27 percent include illiterate adult male members. In upper caste households, the corresponding proportions are 24 percent for women and 11 percent for men. Faced with current school closures, Scheduled Caste parents are less equipped than their upper caste counterparts to assist their children with any form of home learning.

There are other crucial differences. Only 49 percent of Scheduled Caste households have savings in a bank account; 62 percent of upper caste households do. Twenty percent of upper caste households have access to the Internet, compared with just 10 percent of Scheduled Caste households. These differences in access to information technology are critical in shaping access to online education during the pandemic: almost a year since the first lockdown, most schools are still closed.

The economic distress resulting from India’s pandemic response is intensifying preexisting structures of disadvantage based on social identity. Investments in education and health that close gaps between social groups will be essential to build resilience in the face of future shocks.

These findings might appear surprising to anyone under the impression that caste has either vanished or declined in importance in a modernizing, urbanizing, and rapidly globalizing India. To understand the persistence of caste, and of such conflicting views about its reality, it will be useful to briefly delve into an important pre-independence debate that continues to shape beliefs about the caste system to this day.

The debate took place in 1936 between Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi and Bhimrao Ambedkar, two titans of the Indian nationalist movement and leaders of the Congress Party. Gandhi wrote, “The law of varna [caste] teaches us that we have each one of us to earn our bread by following the ancestral calling.” Ambedkar prepared a sharp rejoinder in a speech titled “Annihilation of Caste.” It went undelivered but became a definitive statement (after the text was published that year) on why the caste system could not be reformed but had to be destroyed altogether.

Gaps have widened in the pursuit of higher education and white-collar jobs.

Ambedkar asked, “Must a man follow his ancestral calling even if it does not suit his capacities, even when it has ceased to be profitable? Must a man live by his ancestral calling even if he finds it immoral?” He argued that this was “not only an impossible and impractical ideal, but it is also a morally indefensible ideal.” According to Ambedkar, the reality of the caste system was a “system based on the principle of each according to his birth,” rather than a division of labor based on abilities or merit. Those born into the untouchable castes were condemned to a life of stigma, discrimination, oppression, and humiliation.

The belief that the caste system is a benign division of labor (Gandhi’s view) instead of a malignant division of laborers (Ambedkar’s view) continues to be held widely in India. The Ambedkarite view is just as strongly held.

After Indian independence and the partition of the subcontinent in 1947, a constituent assembly was established to debate the new constitution, which was finally adopted on January 26, 1950. Ambedkar served as the chairman of the drafting committee and went on to become India’s first law minister. It was his understanding of the caste system that shaped the constitutional provisions for reservations, which he argued were necessary to resolve the central contradiction of newly independent India: the ideal of formal equality was enshrined in the constitution but superimposed over substantive inequality on the ground.

Although the practice of untouchability has been illegal in India since 1947, and the Constitution guarantees all citizens equal status regardless of caste or religion, the reality is that caste simply has a new grammar. Since 1991, India has seen a rapid increase in new opportunities thanks to globalization and liberalization, but upper castes have benefited disproportionately. The lower-ranked castes are often deficient in the basic skills needed to take advantage of these new opportunities. Access to higher education has expanded, but labor market discrimination has blocked occupational mobility. Caste continues to mediate economic outcomes and assert its presence in society and politics.

A wealth of evidence shows the long-standing disparities among broad caste groups in material outcomes such as education, occupation, consumption expenditure, wages, and asset ownership. But many Indians assume that these disparities are either largely rural or a mere residue of discrimination in the past. There is a strong and pervasive belief that caste discrimination is absent from the urban formal sector in contemporary India.

The debate over the degree of the caste system’s persistence still centers on the relationship between caste and occupation, since the system traditionally assigned specific occupations to castes. So the debate is really about change: the degree of association, or dissociation, between caste and occupation ought to be a measure of how much the system has changed.

Which castes work in the traditional caste-based occupations now? Are modern occupations (those that do not have a caste counterpart) allocated purely based on ability? In other words, now that the range of occupations in contemporary India far exceeds the occupations assigned by the caste system, how thoroughly has the deck been reshuffled? To what extent does the overlap between caste and status or privilege persist?

The spectrum of modern occupations is not caste-based: caste is not legally recognized, except for the purpose of compensatory affirmative action. All Indians are free to choose their occupation of choice. Yet the higher-ranked castes are concentrated at the top of the occupational spectrum, and the lower-ranked castes are concentrated at the bottom. It turns out that traditional occupations have not broken caste boundaries.

People’s beliefs about how earnings or status correspond to caste are not necessarily informed by evidence. In the 1936 debate, Gandhi said, “I do not find a great disparity between earnings of different tradesmen, including Brahmins.” But the empirical record reveals a significant earnings gap that has widened over time among the top half of wage earners.

Labor markets in the formal sector, which predominantly comprises the modern occupations, display features that are not meritocratic. Firms often have hereditary “reservations”—being born into a business family guarantees access to the top spots. Such hiring practices reveal the pernicious role of networks in informal and personalized recruitment: whom you know is often more important than what you know.

Employers find this convenient and efficient, since it minimizes recruitment outlays, ensures commitment and loyalty, and lowers transaction costs associated with disciplining workers and handling disputes and grievances. But it leads to a narrow distribution of senior positions: top jobs are not representative of the underlying composition of society. (The official affirmative action system of reservations does not extend to the private sector.)

Employers, including multinational corporations, like to use the language of merit. But managers are seemingly blind to the unequal playing field that produces what they take to be meritocratic outcomes. Their commitment to meritocracy tends to be based on the conviction that merit is fairly distributed by caste and region. This results in a process whereby the qualities of individuals are supplanted by stereotypes that make it harder for qualified job applicants to gain recognition for their skills and accomplishments.

Many Indians proclaim that they are casteless—but is it equally easy for different caste groups to shed their caste identities?

The truth is that it is far easier for those born into privilege to shed caste than it is for those who continue to bear the stigma of untouchability. As Ambedkar wrote, “[A]lmost every Brahmin has transgressed the rule of caste. The number of Brahmins who sell shoes is far greater than those who practice priesthood.”

Dalits nonetheless have tried to organize to transcend their low status. Initiatives to promote Dalit entrepreneurship have included the formation of the Dalit Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industry. The objective is to develop entrepreneurial activities as a means of circumventing labor market discrimination. Fostering “Dalit capitalism” will help Dalits be “job givers, not job seekers”—and eventually lift enough Dalits to the top of the social pyramid to end the caste system.

The implicit assumptions in this argument are that self-employment activity would be concentrated at the top end, and that discriminatory tendencies would be absent from other markets critical to the success of entrepreneurship. Both of these assumptions are doubtful. There is now an emerging group of Dalit millionaires who could be “job givers,” but most Dalit businesses occupy a very different place in the production chain: they are bottom-of-the-ladder, low-productivity survival activities, like roadside kiosks or tiny repair units.

After independence, the first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, announced that India had a “tryst with destiny” and was poised to become a force to be reckoned with on the world stage. Underlying this optimism was the hope that the nation would unshackle itself from antiquated ideas. As the economy modernized, a casteless society would emerge. Caste-based affirmative action was seen as a temporary step to achieve a level playing field.

Yet caste has turned out to be fiercely tenacious, reinventing itself over time. This has made the extension of remedial policies necessary. Despite affirmative action’s moderately ameliatory effects, the annihilation of caste has come to seem a herculean task, partly because of the widespread belief that the caste system has ended or is merely a benign cultural artefact. In fact, it continues to be hierarchical, oppressive, and discriminatory. It has morphed to suit the contemporary milieu.

Since the landslide election victory of the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party brought Prime Minister Narendra Modi to power in 2014, the current political dispensation strongly advocates the unity of all Hindus—against other religions, especially India’s Muslim minority—and actively denies caste divisions. A typical claim is that Dalits, being part of the Hindu majority, are insiders—even though historically they were considered too low for and hence unfit to be assigned a varna (caste), and were the avarnas (with no caste), in contrast to the upper-caste savarnas (those with caste).

Caste-based reservations and other policies regarding Dalits have continued under Modi, though his government started a quota for “economically weaker sections” that was ostensibly not caste-based. But even if official policies have not shifted very drastically, there have been major changes on the ground.

August 15, 2016, marked India’s 70th Independence Day. As Modi unfurled the national flag from the ramparts of the Red Fort and delivered his annual address to the nation, an unprecedented gathering was underway in Una, a city in the western state of Gujarat, about 1,300 kilometers from the capital. Thousands of Dalits, who had set out from Ahmedabad on a Dalit Asmita Yatra (Dalit Pride March) ten days earlier, congregated in Una to declare their own independence—not from the British Empire, but from the stigmatizing and dehumanizing occupations traditionally assigned to them.

Caste has turned out to be fiercely tenacious, reinventing itself over time.

These occupations branded them the lowest of the low within the caste system, stamping them with a stigma that has not weakened with India’s post-independence growth and development. The marchers pledged never again to collect human excrement, dispose of cattle carcasses, or perform other humiliating caste-assigned tasks.

It is noteworthy that this gathering took place in Gujarat, the poster child for the presumed ability of economic growth to lift all groups out of poverty and put everyone on the path of socioeconomic advancement, regardless of social identity. (Modi cultivated this reputation while serving as the state’s chief minister for over a decade.) The Dalit gathering demonstrated that something was amiss with this development-lifts-all rhetoric.

Una had been chosen as the site of this momentous event in response to a grim incident in the city the previous month. A “cow vigilante” ( gau rakshak ) group had chained seven Dalit youths to a van and publicly thrashed them for skinning a dead cow. This atrocity, which was filmed and proudly circulated by the perpetrators, went viral via online sharing on various social media platforms. It led to a wave of anger and protest, finally culminating in the historic march.

In sharp contrast to the official event in New Delhi, this Independence Day celebration was bursting at the seams with the voluntary participation of the marginalized. They, too, saluted the national flag, but it was unfurled by Radhika Vemula—the mother of Rohit Vemula, a Dalit research scholar at the University of Hyderabad who had committed suicide in January that year. He and others had been subjected to harsh disciplinary action for their activities as members of the Ambedkar Students’ Association.

The past few years have seen growing majoritarianism in India, accompanied by a sharpening of caste cleavages. The emboldened cow vigilantes have targeted traditional Dalit livelihoods, particularly the meat and leather industries. There have also been vicious attacks on Dalit–upper caste mixed couples.

Meanwhile, economic gaps and wage and occupational discrimination continue undiminished and appear to be getting worse due to the pandemic, deepening caste inequality. There are anecdotal accounts of a surge in discrimination and the stigmatizing practice of untouchability under the pretext of social distancing.

In a little less than a year, the scientific community moved heaven and earth to develop vaccines to halt the spread of the pandemic. But there are no one-shot cures for inequality and discrimination. Unless a strong anti-caste, egalitarian social movement emerges, caste will continue to embroil individual lives, just as divisions based on differences such as race continue to define the socioeconomic realities of the advanced industrialized nations of the West.

Recipient(s) will receive an email with a link to 'How India’s Caste Inequality Has Persisted—and Deepened in the Pandemic' and will not need an account to access the content.

Subject: How India’s Caste Inequality Has Persisted—and Deepened in the Pandemic

(Optional message may have a maximum of 1000 characters.)

Citing articles via

Email alerts, affiliations.

- Recent Content

- Browse Issues

- Regional Issues

- Global Trends

- Special Issues

- Virtual Issues

- All Content

- Info for Authors

- Info for Librarians

- Editorial Team

- Online ISSN 1944-785X

- Print ISSN 0011-3530

- Copyright © 2024

Stay Informed

Disciplines.

- Ancient World

- Anthropology

- Communication

- Criminology & Criminal Justice

- Film & Media Studies

- Food & Wine

- Browse All Disciplines

- Browse All Courses

- Book Authors

- Booksellers

- Instructions

- Journal Authors

- Journal Editors

- Media & Journalists

- Planned Giving

About UC Press

- Press Releases

- Seasonal Catalog

- Acquisitions Editors

- Customer Service

- Exam/Desk Requests

- Media Inquiries

- Print-Disability

- Rights & Permissions

- UC Press Foundation

- © Copyright 2024 by the Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Privacy policy Accessibility

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

UPSC Coaching, Study Materials, and Mock Exams

Enroll in ClearIAS UPSC Coaching Join Now Log In

Call us: +91-9605741000

Caste System in India – Origin, Features, and Problems

Last updated on September 21, 2023 by ClearIAS Team

Table of Contents

Jana → Jati → Caste

The word caste derives from the Spanish and Portuguese “casta”, means “race, lineage, or breed”. Portuguese employed casta in the modern sense when they applied it to hereditary Indian social groups called as ‘jati’ in India. ‘Jati’ originates from the root word ‘Jana’ which implies taking birth. Thus, caste is concerned with birth.

According to Anderson and Parker, “Caste is that extreme form of social class organization in which the position of individuals in the status hierarchy is determined by descent and birth .”

How did Caste System originate in India: Various Theories

There are many theories like traditional, racial, political, occupational, evolutionary etc which try to explain the caste system in India.

1.Traditional Theory

According to this theory, the caste system is of divine origin. It says the caste system is an extension of the varna system, where the 4 varnas originated from the body of Bramha.

At the top of the hierarchy were the Brahmins who were mainly teachers and intellectuals and came from Brahma’s head. Kshatriyas, or the warriors and rulers, came from his arms. Vaishyas, or the traders, were created from his thighs. At the bottom were the Shudras, who came from Brahma’s feet. The mouth signifies its use for preaching, learning etc, the arms – protections, thighs – to cultivate or business, feet – helps the whole body, so the duty of the Shudras is to serve all the others. The sub-castes emerged later due to intermarriages between the 4 varnas.

The proponents of this theory cite Purushasukta of Rigveda, Manusmriti etc to support their stand.

2. Racial Theory

The Sanskrit word for caste is varna which means colour. The caste stratification of the Indian society had its origin in the chaturvarna system – Brahmins, Kashtriyas, Vaishyas and Shudras. Indian sociologist D.N. Majumdar writes in his book, “ Races and Culture in India ”, the caste system took its birth after the arrival of Aryans in India.

Rig Vedic literature stresses very significantly the differences between the Arya and non-Aryans (Dasa), not only in their complexion but also in their speech, religious practices, and physical features.

The Varna system prevalent during the Vedic period was mainly based on division of labour and occupation. The three classes, Brahma, Kshatra and Vis are frequently mentioned in the Rig Veda. Brahma and Kshatra represented the poet-priest and the warrior-chief. Vis comprised all the common people. The name of the fourth class, the ‘Sudra’, occurs only once in the Rig Veda. The Sudra class represented domestic servants.

3. Political Theory

According to this theory, the caste system is a clever device invented by the Brahmins in order to place themselves on the highest ladder of social hierarchy.

Join Now: CSAT Course

Dr. Ghurye states, “Caste is a Brahminic child of Indo-Aryan culture cradled in the land of the Ganges and then transferred to other parts of India.”

The Brahmins even added the concept of spiritual merit of the king, through the priest or purohit in order to get the support of the ruler of the land.

4. Occupational Theory

Caste hierarchy is according to the occupation. Those professions which were regarded as better and respectable made the persons who performed them superior to those who were engaged in dirty professions.

According to Newfield, “Function and function alone is responsible for the origin of caste structure in India.” With functional differentiation there came in occupational differentiation and numerous sub-castes such as Lohar(blacksmith), Chamar(tanner), Teli(oil-pressers).

5. Evolution Theory

According to this theory, the caste system did not come into existence all of a sudden or at a particular date. It is the result of a long process of social evolution.

- Hereditary occupations;

- The desire of the Brahmins to keep themselves pure;

- The lack of rigid unitary control of the state;

- The unwillingness of rulers to enforce a uniform standard of law and custom

- The ‘Karma’ and ‘Dharma’ doctrines also explain the origin of caste system. Whereas the Karma doctrine holds the view that a man is born in a particular caste because of the result of his action in the previous incarnation, the doctrine of Dharma explains that a man who accepts the caste system and the principles of the caste to which he belongs, is living according to Dharma. Confirmation to one’s own dharma also remits on one’s birth in the rich high caste and violation gives a birth in a lower and poor caste.

- Ideas of exclusive family, ancestor worship, and the sacramental meal;

- Clash of antagonistic cultures particularly of the patriarchal and the matriarchal systems;

- Clash of races, colour prejudices and conquest;

- Deliberate economic and administrative policies followed by various conquerors

- Geographical isolation of the Indian peninsula;

- Foreign invasions;

- Rural social structure.

Note: It is from the post-Vedic period, the old distinction of Arya and Sudra appears as Dvija and Sudra, The first three classes are called Dvija (twice-born) because they have to go through the initiation ceremony which is symbolic of rebirth. “The Sudra was called “ekajati” (once born).

Note: Caste system developed on rigid lines post Mauryan period , especially after the establishment of Sunga dynasty by Pushyamitra Sunga (184 BC). This dynasty was an ardent patron of ‘Brahminism’. Through Manusmriti, Brahmins once again succeeded in organizing the supremacy and imposed severe restrictions on the Sudras. Manusmriti mentioned that, ‘the Sudra, who insults a twice-born man, shall have his tongue cut out’.

Note: Chinese scholar Hieun Tsang, who visited India in 630 AD , writes that, “Brahminism dominated the country, caste ruled the social structure and the persons following unclean occupations like butchers, scavengers had to live outside the city”.

Principal features of caste system in India

- Segmental Division of Society: The society is divided into various small social groups called castes. Each of these castes is a well developed social group, the membership of which is determined by the consideration of birth.

- Hierarchy: According to Louis Dumont, castes teach us a fundamental social principle of hierarchy. At the top of this hierarchy is the Brahmin caste and at the bottom is the untouchable caste. In between are the intermediate castes, the relative positions of which are not always clear.

- Endogamy: Endogamy is the chief characteristic of caste, i.e. the members of a caste or sub-caste should marry within their own caste or sub-caste. The violation of the rule of endogamy would mean ostracism and loss of caste. However, hypergamy (the practice of women marrying someone who is wealthier or of higher caste or social status.) and hypogamy (marriage with a person of lower social status) were also prevalent. Gotra exogamy is also maintained in each caste. Every caste is subdivided into different small units on the basis of gotra. The members of one gotra are believed to be successors of a common ancestor-hence prohibition of marriage within the same gotra.

- Hereditary status and occupation: Megasthenes, the Greek traveller to India in 300 B. C., mentions hereditary occupation as one of the two features of caste system, the other being endogamy.

- Restriction on Food and Drink: Usually a caste would not accept cooked food from any other caste that stands lower than itself in the social scale, due to the notion of getting polluted. There were also variously associated taboos related to food. The cooking taboo, which defines the persons who may cook the food. The eating taboo which may lay down the ritual to be followed at meals. The commensal taboo which is concerned with the person with whom one may take food. Finally, the taboo which has to do with the nature of the vessel (whether made of earth, copper or brass) that one may use for drinking or cooking. For eg: In North India Brahmin would accept pakka food (cooked in ghee) only from some castes lower than his own. However, no individual would accept kachcha(cooked in water) food prepared by an inferior caste. Food prepared by Brahmin is acceptable to all, the reason for which domination of Brahmins in the hotel industry for a long time. The beef was not allowed by any castes, except harijans.

- A Particular Name: Every caste has a particular name though which we can identify it. Sometimes, an occupation is also associated with a particular caste.

- The Concept of Purity and Pollution: The higher castes claimed to have ritual, spiritual and racial purity which they maintained by keeping the lower castes away through the notion of pollution. The idea of pollution means a touch of lower caste man would pollute or defile a man of higher caste. Even his shadow is considered enough to pollute a higher caste man.

- Jati Panchayat: The status of each caste is carefully protected, not only by caste laws but also by the conventions. These are openly enforced by the community through a governing body or board called Jati Panchayat. These Panchayats in different regions and castes are named in a particular fashion such as Kuldriya in Madhya Pradesh and Jokhila in South Rajasthan.

Varna vs Caste – The difference

Varna and caste are 2 different concepts, though some people wrongly consider it the same.

Functions of the caste system

- It continued the traditional social organization of India.

- It has accommodated multiple communities by ensuring each of them a monopoly of a specific means of livelihood.

- Provided social security and social recognition to individuals. It is the individual’s caste that canalizes his choice in marriage, plays the roles of the state-club, the orphanage and the benefits society. Besides, it also provides him with health insurance benefits. It even provides for his funeral.

- It has handed over the knowledge and skills of the hereditary occupation of a caste from one generation to another, which has helped the preservation of culture and ensured productivity.

- Caste plays a crucial role in the process of socialization by teaching individuals the culture and traditions, values and norms of their society.

- It has also led to interdependent interaction between different castes, through jajmani relationships. Caste acted as a trade union and protected its members from the exploitation.

- Promoted political stability, as Kshatriyas were generally protected from political competition, conflict and violence by the caste system.

- Maintained racial purity through endogamy.

- Specialization led to quality production of goods and thus promoted economic development. For eg: Many handicraft items of India gained international recognition due to this.

Dysfunctions of the caste system

- The caste system is a check on economic and intellectual advancement and a great stumbling block in the way of social reforms because it keeps economic and intellectual opportunities confined to a certain section of the population only.

- It undermines the efficiency of labour and prevents perfect mobility of labour, capital and productive effort

- It perpetuates the exploitation of the economically weaker and socially inferior castes, especially the untouchables.

- It has inflicted untold hardships on women through its insistence on practices like child-marriage, prohibition of widow-remarriage, seclusion of women etc.

- It opposes real democracy by giving a political monopoly to Kshatriyas in the past and acting as a vote bank in the present political scenario. There are political parties which solely represent a caste. eg: BSP was formed by Kanshi Ram mainly to represent SC, ST and OBC.

- It has stood in the way of national and collective consciousness and proved to be a disintegrating rather than an integrating factor. Caste conflicts are widely prevalent in politics, reservation in jobs and education , inter-caste marriages etc. eg: Demand for Jat reservation, agitation by Patidar community.

- It has given scope for religious conversion. The lower caste people are getting converted into Islam and Christianity due to the tyranny of the upper castes.

- The caste system by compelling an individual to act strictly in accordance with caste norms stands in the way of modernization, by opposing change.

Is the caste system unique to India?

The caste system is found in other countries like Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Caste-like systems are also found in countries like Indonesia, China, Korea, Yemen and certain countries in Africa, Europe as well.

But what distinguishes Indian caste system from the rest is the core theme of purity and pollution, which is either peripheral or negligible in other similar systems of the world. In Yemen, there exists a hereditary caste, Al-Akhdam who are kept as perennial manual workers. Burakumin in Japan, originally members of outcast communities in the Japanese feudal era, includes those with occupations considered impure or tainted by death.

However, India is unique in some aspects.

- India has had a cultural continuity that no other civilization has had. The ancient systems, religions, cultures of other civilizations have been mostly gone. In India, history is present and even the external empires mostly co-opted the system rather than changing them.

- The caste has been merged into a modern religion, making it hard to remove.

- India has integrated multiple systems more easily. What is known as “caste” in Portuguese/English is actually made of 3 distinct components – jati, jana, varna. Jati is an occupational identification. Jana is an ethnic identification. Varna is a philosophical identification. These have been more tightly merged over the centuries.

- In the world’s most transformative period – of the past 3 centuries, India spent most of it under European colonialism. Thus, India lost a lot of time changing. Most of the changes to the system came only in 1950 when India became a republic .

To summarize theoretically, caste as a cultural phenomenon (i.e., as a matter of ideology or value system) is found only in India while when it is viewed as a structural phenomenon, it is found in other societies too.

There are four sociological approaches to caste by distinguishing between the two levels of theoretical formulation, i.e., cultural and structural, and universalistic and particularistic. These four approaches are cultural-universalistic, cultural-particularistic, structural- universalistic and structural-particularistic.

- Structural-particularistic view of caste has maintained that the caste system is restricted to the Indian society

- Structural-universalistic category holds that caste in India is a general phenomenon of a closed form of social stratification found across the world.

- The third position of sociologists like Ghurye who treat caste as a cultural universalistic phenomenon maintains that caste-like cultural bases of stratification are found in most traditional societies. Caste in India is a special form of status-based social stratification. This viewpoint was early formulated by Max Weber.

- The cultural-particularistic view is held by Louis Dumont who holds that caste is found only in India.

Is the caste system unique to Hinduism?

Caste-based differences are practised in other religions like Nepalese Buddhism, Christianity, Islam, Judaism and Sikhism. But the main difference is – caste system in Hinduism is mentioned in its scriptures while other religions adopted casteism as a part of socialization or religious conversions. In other words, the caste system in Hinduism is a religious institution while it is social in others.

As a general rule, higher castes converts became higher castes in other religions while lower caste converts acquired lower caste positions.

- Islam – Some upper caste Hindus converted to Islam and became part of the governing group of Sultanates and Mughal Empire, who along with Arabs, Persians and Afghans came to be known as Ashrafs . Below them are the middle caste Muslims called Ajlafs , and the lowest status is those of the

- Christianity – In Goa, Hindu converts became Christian Bamonns while Kshatriya and Vaishya became Christian noblemen called Chardos. Those Vaishya who could not get admitted into the Chardo caste became Gauddos, and Shudras became Sudirs. Dalits who converted to Christianity became Mahars and Chamars

- Buddhism – various forms of the caste system are practised in several Buddhist countries, mainly in Sri Lanka, Tibet, and Japan where butchers, leather and metal workers and janitors are sometimes regarded as being impure.

- Jainism – There are Jain castes wherein all the members of a particular caste are Jains. At the same time, there have been Jain divisions of several Hindu castes.

- Sikhism – Sikh literature mention Varna as Varan , and Jati as Zat. Eleanor Nesbitt, a professor of Religion, states that the Varan is described as a class system, while Zat has some caste system features in Sikh literature. All Gurus of Sikhs married within their Zat , and they did not condemn or break with the convention of endogamous marriages.

Caste Divisions – The future?

The caste system in India is undergoing changes due to progress in education, technology, modernization and changes in general social outlook. In spite of the general improvement in conditions of the lower castes, India has still a long way to go, to root out the evils of the caste system from the society.

References:

- https://www.sociologyguide.com

- Sociology for Nurses by Shama Lohumi

- Indian Social system by Ram Ahuja

Article contributed by: Rehna R. Rehna is a UPSC Civil Services Exam 2016 Rank Holder.

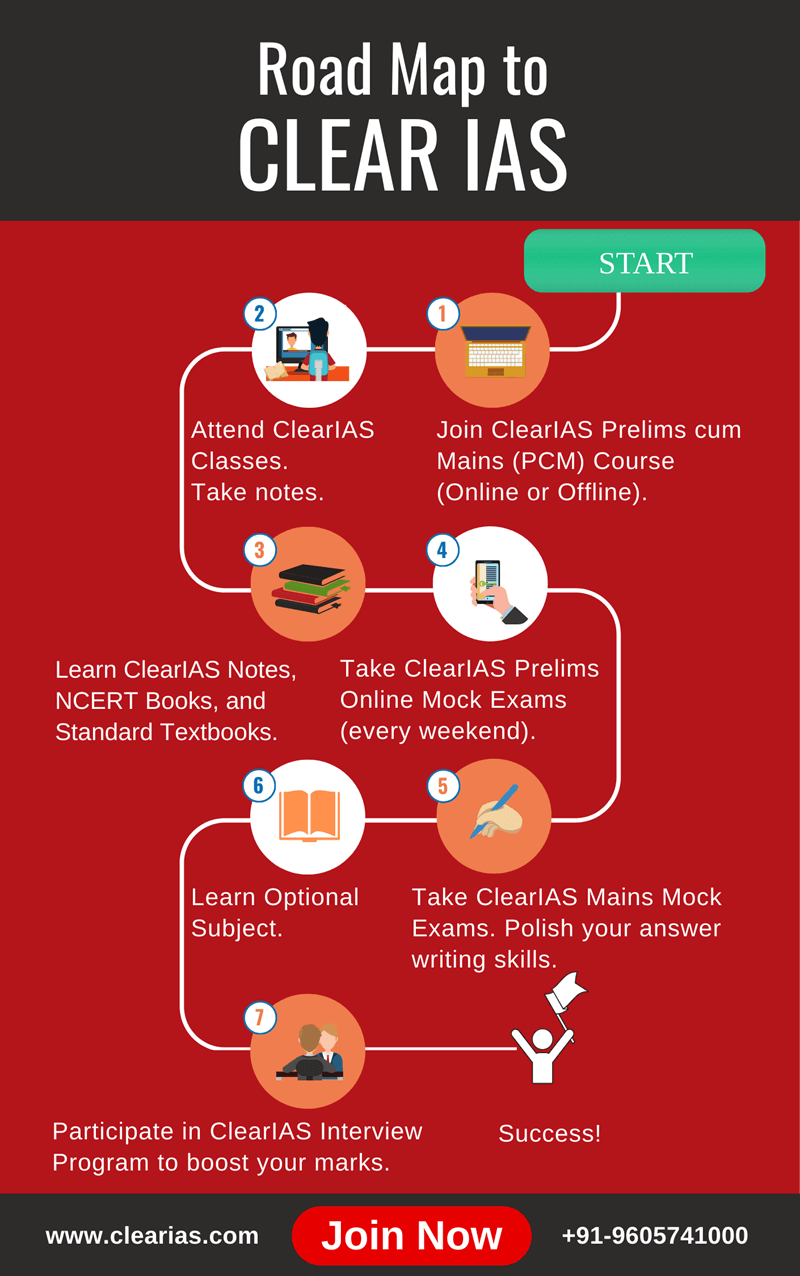

Take a Test: Analyse Your Progress

Aim IAS, IPS, or IFS?

About ClearIAS Team

ClearIAS is one of the most trusted learning platforms in India for UPSC preparation. Around 1 million aspirants learn from the ClearIAS every month.

Our courses and training methods are different from traditional coaching. We give special emphasis on smart work and personal mentorship. Many UPSC toppers thank ClearIAS for our role in their success.

Download the ClearIAS mobile apps now to supplement your self-study efforts with ClearIAS smart-study training.

Reader Interactions

August 18, 2017 at 3:14 pm

wow…..exclnt…

August 18, 2017 at 7:59 pm

August 18, 2017 at 10:29 pm

i would like to receive the new posts updates to my email. i didnt find the option to join or subscribe….

August 19, 2017 at 8:53 am

Hi, Open clearias.com from a new browser (or clear your cache) and you will see the option for free email subscription.

August 29, 2017 at 4:37 pm

Wonderful explanation in all dimensions.

February 11, 2018 at 11:58 am

April 28, 2018 at 11:03 am

very nice.. matter is exactly what i was searching to teach my students..

August 18, 2018 at 9:14 am

You guys must see this video strong message.

https://youtu.be/AKTdd6GgnQw

November 9, 2021 at 7:45 pm

Good balanced writeup. Would have liked some speculation on the future of Caste in India, the appearance of the ‘fifth’ caste of Untouchables etc. But thanks.

December 24, 2021 at 10:02 pm

“All Gurus of Sikhs married within their Zat, and they did not condemn or break with the convention of endogamous marriages.” I would like to recommend a correction in this sentence given in the article. All of the Sikh Gurus condemned the caste system and the concept of endogamous marriages. The tenth Sikh Guru bestowed the last names of Kaur and Singh so that the concept of caste could be removed. Another reason for this was stop the practice of forcing females to take up the surname of their husband after marriage.

March 19, 2022 at 6:47 pm

A pure propaganda without covering any view from the natives and covers only the colonial views and you wonder why the IAS officers hate this country and dont have speck of nationalism. Next some serious question, if caste existed for thousands of years why it has its origin in spanish or porteguse race system? basically it shows europeans shoved their race system in the existing indian social system. So how does it make it a old system it is just a new system created by colonialist but blamed on indians for it. Next Both Varna and Jati are different from colonial caste. It seems govt needs to change syllabus otherwise our country will never develop.

February 4, 2023 at 10:01 pm

Exactly said. Wonder how aspiring IAS candidates are brainwashed with this false information undermining the original societal demarcation, and creating false propaganda. British have created the caste system to create infighting in India. The syllabus needs to change asap to reflect the truth.

January 7, 2023 at 9:13 pm

informative love it, thankyou <3

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Don’t lose out without playing the right game!

Follow the ClearIAS Prelims cum Mains (PCM) Integrated Approach.

Join ClearIAS PCM Course Now

UPSC Online Preparation

- Union Public Service Commission (UPSC)

- Indian Administrative Service (IAS)

- Indian Police Service (IPS)

- IAS Exam Eligibility

- UPSC Free Study Materials

- UPSC Exam Guidance

- UPSC Prelims Test Series

- UPSC Syllabus

- UPSC Online

- UPSC Prelims

- UPSC Interview

- UPSC Toppers

- UPSC Previous Year Qns

- UPSC Age Calculator

- UPSC Calendar 2024

- About ClearIAS

- ClearIAS Programs

- ClearIAS Fee Structure

- IAS Coaching

- UPSC Coaching

- UPSC Online Coaching

- ClearIAS Blog

- Important Updates

- Announcements

- Book Review

- ClearIAS App

- Work with us

- Advertise with us

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Talk to Your Mentor

Featured on

and many more...

The multiple faces of inequality in India

Post-doctoral research fellow in economics, Centre de Sciences Humaines de New Delhi

Disclosure statement

Tista Kundu a reçu des financements de AXA Research Fund.

View all partners

Known for its caste system, India is often thought of as one of the world’s most unequal countries. The 2022 World Inequality Report (WIR), headed by leading economist Thomas Piketty and his protégé, Lucas Chancel, did nothing to improve this reputation. Their research showed that the gap between the rich and the poor in India is at a historical high, with the top 10% holding 57% of national income – more than the average of 50% under British colonial rule (1858-1947). In contrast, the bottom half accrued only 13% of national revenue. A February report by Oxfam noted 2021 alone saw 84% of households suffer a loss of income while the number of Indian billionaires grew from 102 to 142.

Both reports highlight not only the problem of revenue inequality but also of opportunity. While there may be disagreement between left and right on the ethics of equality, there is a consensus that everyone should be given the chance to succeed and the principle of fairness – and not factors such as birth, region, race, gender, ethnicity or family backgrounds – ought to lay the foundations of a level playing field for all.

Drawing from the latest pre-pandemic database from the Periodic Labour Force Survey of 2018-19, our research confirms this is far from the case in India. On the one hand, the country has had a consistently high GDP growth rate of more than 7% for nearly two decades, the exception being the period around the 2008 financial crisis. On the other hand, this income has failed to trickle down to India’s marginalised communities, with preliminary results pointing to a higher level of inequality of opportunity in the country than in Brazil or Guatemala.

Precarity as well as a large shadow economy also plague the country’s labour market. Even before the pandemic, only 30% to 40% of regular salaried adult Indian earners had job contracts or social securities such as national pension schemes, provident fund or health insurance. For self-employed workers, the situation is even more critical, even though these constituted nearly 60% of the Indian labour force in 2019.

Castes, gender and background still determine life chances

Our research indicated that at least 30% of earning inequality is still determined by caste, gender and family backgrounds. The seriousness of this figure becomes clear when it’s compared with rates of the world’s most egalitarian countries, such as Finland and Norway, where the respective estimates are below 10% for a similar set of social and family attributes.

The caste system is a distinctive feature of Indian inequality. Emerging around 1500 BC, the hereditary social classification draws its origins from occupational hierarchy. Ancient Indian society was thought to be divided in four Varnas or castes: Brahmins (the priests), Khatriyas (the soldiers), Vaishyas (the traders) and Shudras (the servants), in order of hierarchy. Apart from the above four, there were the “untouchables” or Dalits (the oppressed), as they are called now, who were prohibited to come into contact with any of the upper castes. These groups were further subdivided in thousands of sub-castes or Jatis , with complicated internal hierarchy, eventually merged into fewer manageable categories under the British colonisation period.

The Indian constitution secures the rights of the Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST) and Other Backward Class (OBC) through a caste-based reservation quota, by virtue of which a certain portion of higher-education admissions, public sector jobs, political or legislative representations, are reserved for them. Despite this, there is a notable earning inequality between these social categories and the rest of the population, who consists of no more than 30% to 35% of Indian population. Adopting a data-driven approach we find that, on average, SC, ST and OBC still earn less than the rest.

While unique, the caste system is not the only source of unfairness. Indeed, it accounts for less than 7% of inequality of opportunity, something that’s in itself laudable. We will need to add criteria such as gender and family background differences to explain 30% of inequality.

In a country where femicides and rapes regularly make headlines, it comes as no surprise that women from marginalised social groups are often subject to a “double disadvantage”. For some states such as Rajasthan (in the country’s northwest), Andhra Pradesh (south), Maharashtra (centre), we find even upper-caste women enjoy fewer educational opportunities than men from the marginalised SC/ST communities. Even among the graduates, while the national average employment rate for males is 70%, it is below 30% for the females.

A temporary byproduct of rising growth?

Rising inequality could be dismissed as a temporary byproduct of rapid growth on the grounds of Simon Kuznets’ famous hypothesis , according to which inequality rises with rapid growth before eventually subsiding. However, there is no guarantee of this, least of all because widening gap between rich and poor is not only limited to fast-growing countries such as India. Indeed, a 2019 study found that the growth-inequality relationship often reflects inequality of opportunity and prospects of growth are relatively dim for economies with a bumpy distribution of opportunities.

Despite sporadic evidence of converging caste or gender gaps, our research shows an intricate web of social hierarchy has been cast over every aspect of life in India. It is true that some deprived castes may withdraw from school early to explore traditional jobs available to their caste-based networks – thereby limiting their opportunities. However, are they responsible for such choices or it is the precariousness of the Indian economy that pushes them down such routes? There is no straightforward answer to these questions, even if some of the “bad choices” that individuals make can result more from pressure than choice.

Given the complicated intertwining of various forms of hierarchy in India, broad policies targeting inequality may have less success than anticipated. Dozens of factors other than caste, gender or family background feed into inequality, including home sanitation, school facilities, domestic violence, access to basic infrastructure such as electricity, water or healthcare, crime rates, political stability of the locality, environmental risks and many more.

Better data would allow researchers studying India to capture the contours of its society and also help gauge the effectiveness of policies intended to expand opportunities for the neediest.

Created in 2007 to help accelerate and share scientific knowledge on key societal issues, the AXA Research Fund has supported nearly 700 projects around the world conducted by researchers in 38 countries. To learn more, visit the site of the AXA Research Fund or follow on Twitter @AXAResearchFund.

- Caste system

- The Conversation France

- Axa Research Fund (English)

- Sexism at work

- India caste system

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Senior Disability Services Advisor

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

GRAINS RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION CHAIRPERSON

- CBSE Class 10th

- CBSE Class 12th

- UP Board 10th

- UP Board 12th

- Bihar Board 10th

- Bihar Board 12th

- Top Schools in India

- Top Schools in Delhi

- Top Schools in Mumbai

- Top Schools in Chennai

- Top Schools in Hyderabad

- Top Schools in Kolkata

- Top Schools in Pune

- Top Schools in Bangalore

Products & Resources

- JEE Main Knockout April

- Free Sample Papers

- Free Ebooks

- NCERT Notes

- NCERT Syllabus

- NCERT Books

- RD Sharma Solutions

- Navodaya Vidyalaya Admission 2024-25

- NCERT Solutions