Advertisement

Supported by

Ring of Power

- Share full article

By Ellen Ullman

- Nov. 1, 2013

Mae Holland, a woman in her 20s, arrives for her first day of work at a company called the Circle. She marvels at the beautiful campus, the fountain, the tennis and volleyball courts, the squeals of children from the day care center “weaving like water.” The first line in the book is: “ ‘My God,’ Mae thought. ‘It’s heaven.’ ”

And so we know that the Circle in Dave Eggers’s new novel, “The Circle,” will be a hell.

The time is somewhere in the not-too-distant future — the Three Wise Men who own and rule the Circle are recognizable as individuals living today. The company demands transparency in all things; two of its many slogans are SECRETS ARE LIES and PRIVACY IS THEFT. Anonymity is banished; everyone’s past is revealed; everyone’s present may be broadcast live in video and sound. Nothing recorded will ever be erased. The Circle’s goal is to have all aspects of human existence — from voting to love affairs — flow through its portal, the sole such portal in the world.

This potential dystopia should sound familiar. Books and tweets and blogs are already debating the issues Eggers raises: the tyranny of transparency, personhood defined as perpetual presence in social networks, our strange drive to display ourselves, the voracious information appetites of Google and Facebook, our lives under the constant surveillance of our own government.

“The Circle” adds little of substance to the debate. Eggers reframes the discussion as a fable, a tale meant to be instructive. His instructors include a Gang of 40, a Transparent Man, a shadowy figure who may be a hero or a villain, a Wise Man with a secret chamber and a smiling legion of true-believing company employees. The novel has the flavor of a comic book: light, entertaining, undemanding.

Readers who enter the Circle’s potential Inferno do not have the benefit of Virgil, Dante’s guide through hell and purgatory, but they do have Mae, a naïve girl with the sensibility of a compulsive iPhone FaceTime chatterer. (Oddly, Mae does not lead us through the ranks of programmers — let alone offer a glimpse of a woman programmer — a strange omission in a book purporting to be about technology.)

Mae has been introduced to the Circle by her friend and former roommate Annie, who is close to the Three Wise Men. She begins work in lowly Customer Experience, providing boilerplate answers to client questions and complaints. Her performance is tabulated after every interaction, her ratings displayed for all to see.

Mae is an eager competitor, earning a record score on her first day. Soon she is a champion Circler, moving ever closer to the company’s inner rings. Eventually she becomes as transparent as a person can be within the realm of the Circle: wired for the broadcasting of her every waking move. In the bathroom, for instance, she can turn off the audio, but the camera stays on, focused on the back of the stall door. (If she is silent for too long, her followers send urgent messages asking if she is O.K.)

At each advance into “participation” (or descent into hell, as the case may be), Mae is a tail-wagging puppy waiting for the next reward: a better rating, millions of viewers. Far from resisting, she finds each new electronic demand “delicious” and “exhilarating.” Now and then, she briefly feels a black “tear” opening inside her, but the feeling comes at improbable moments and in such overheated prose as to parody emotion: “a scream muffled by fathomless waters, that high-pitched scream of a million drowned voices.”

Can anything prevent Mae’s fall into the depths of the Circle? Enter the mysterious Kalden. While everyone else lives in the clear light of transparency, Kalden emerges from the shadows. Everyone working at the Circle can be located, but Kalden’s name appears nowhere; Mae experiences his invisibility as “aggressive.” Everyone inside the Circle is young and healthy; the outside is for the old and ill. And here is Kalden, who has gray hair yet looks young. The symbolism — is he a vibrant Circler or an old man from the dark outside? — is all too obvious.

At their second meeting, Mae follows Kalden down long corridors, through underground tunnels, down and down and down. What she sees in this netherworld is a metallic red box the size of a bus, wrapped in tentacles of “gleaming silver pipes.” Kalden tells her it stores the experiences of the Transparent Man, who for five years has recorded everything he has seen and heard. Kalden makes some excuse for the box’s huge size, but his technical explanation is ridiculous. There just happens to be a mattress in an alcove, where Mae and Kalden have sex — she thrills as he breathes “fire into her ear.” Later Kalden will say the Circle is in fact a “totalitarian nightmare,” as if a reader did not know this from the start.

Like Kalden, alas, Eggers tends to overexplain. An example of what might have been a fine scene: Mae is with her ex-boyfriend, Mercer, who makes chandeliers out of deer antlers. (Eggers has not been kind to Mercer in giving him this occupation.) Mae takes out her digital device and, without Mercer’s asking, starts reciting negative online reviews of his work. He begs her to stop. But Mae reads another: “All those poor deer antlers died for this?” The scene, having established Mae’s casual cruelty, should have ended there. Instead it continues for five more pages, during which Mae and Mercer debate the effects of social media. The words “author’s message” flash above the scene, as they do above too many others.

Do we even care about Mae? What remains of her life outside the Circle — Mercer, her family, her father’s multiple sclerosis — she relentlessly (and blithely) draws inside the power ring of the company, to disastrous and tragic effect. And finally Annie, the onetime friend who drew her into the Circle: Mae wants to triumph over her and push her out, again to disastrous effect. A sense of horror finally arrives near the end of the book, coming not through Mae’s eyes but through the power of Eggers’s writing, which we have been waiting for all along. The final scene is chilling.

Mae, then, is not a victim but a dull villain. Her motivations are teenage-Internet petty: getting the highest ratings, moving into the center of the Circle, being popular. She presents a plan that will enclose the world within the Circle’s reach, but she exhibits no complex desire for power, only a longing for the approval of the Wise Men. She is more a high school mean girl than an evil opponent. Perhaps this is what Eggers wants to say: that evil in the future will look more like the trivial Mae than it will the hovering dark eye of Big Brother. If so, he should have worked much harder to express this profound thought. The characters need substance; Mae must be more than a cartoon.

There is an early scene in which Mae could have become a rounded character, one we might worry about. It is her first day on the job. All information on her digital devices has been transferred to the Circle’s system. During the introductory formalities, she is asked if she would like to hand over her old laptop for responsible recycling. But Mae hesitates. “Maybe tomorrow,” she says. “I want to say goodbye.”

If there was ever a need for a pause in the narrative, it is after that “goodbye.” In the opening of a white space, we might imagine Mae’s feelings as she holds the device containing her private experiences. We might linger over what it means to surrender — voluntarily, even eagerly — the last shreds of one’s personal life.

By Dave Eggers

491 pp. Alfred A. Knopf/McSweeney’s Books. $27.95.

Ellen Ullman’s most recent book is the novel “By Blood.”

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

Stephen King, who has dominated horror fiction for decades , published his first novel, “Carrie,” in 1974. Margaret Atwood explains the book’s enduring appeal .

The actress Rebel Wilson, known for roles in the “Pitch Perfect” movies, gets vulnerable about her weight loss, sexuality and money in her new memoir.

“City in Ruins” is the third novel in Don Winslow’s Danny Ryan trilogy and, he says, his last book. He’s retiring in part to invest more time into political activism .

Jonathan Haidt, the social psychologist and author of “The Anxious Generation,” is “wildly optimistic” about Gen Z. Here’s why .

Do you want to be a better reader? Here’s some helpful advice to show you how to get the most out of your literary endeavor .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

by Dave Eggers ‧ RELEASE DATE: Oct. 8, 2013

Though Eggers strives for a portentous, Orwellian tone, this book mostly feels scolding, a Kurt Vonnegut novel rewritten by...

A massive feel-good technology firm takes an increasingly totalitarian shape in this cautionary tale from Eggers ( A Hologram for the King , 2012, etc.).

Twenty-four-year-old Mae feels like the luckiest person alive when she arrives to work at the Circle, a California company that’s effectively a merger of Google, Facebook, Twitter and every other major social media tool. Though her job is customer-service drudgework, she’s seduced by the massive campus and the new technologies that the “Circlers” are working on. Those typically involve increased opportunities for surveillance, like the minicameras the company wants to plant everywhere, or sophisticated data-mining tools that measure every aspect of human experience. (The number of screens at Mae’s workstation comically proliferate as new monitoring methods emerge.) But who is Mae to complain when the tools reduce crime, politicians allow their every move to be recorded, and the campus cares for her every need, even providing health care for her ailing father? The novel reads breezily, but it’s a polemic that’s thick with flaws. Eggers has to intentionally make Mae a dim bulb in order for readers to suspend disbelief about the Circle’s rapid expansion—the concept of privacy rights are hardly invoked until more than halfway through. And once they are invoked, the novel’s tone is punishingly heavy-handed, particularly in the case of an ex of Mae's who wants to live off the grid and warns her of the dehumanizing consequences of the Circle’s demand for transparency in all things. (Lest that point not be clear, a subplot involves a translucent shark that’s terrifyingly omnivorous.) Eggers thoughtfully captured the alienation new technologies create in his previous novel, A Hologram for the King , but this lecture in novel form is flat-footed and simplistic.

Pub Date: Oct. 8, 2013

ISBN: 978-0-385-35139-3

Page Count: 504

Publisher: Knopf

Review Posted Online: Sept. 15, 2013

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Oct. 1, 2013

LITERARY FICTION | DYSTOPIAN FICTION | THRILLER | TECHNICAL & MEDICAL THRILLER | GENERAL THRILLER & SUSPENSE

Share your opinion of this book

More by Dave Eggers

BOOK REVIEW

by Dave Eggers

More About This Book

SEEN & HEARD

Awards & Accolades

Our Verdict

New York Times Bestseller

by Max Brooks ‧ RELEASE DATE: June 16, 2020

A tasty, if not always tasteful, tale of supernatural mayhem that fans of King and Crichton alike will enjoy.

Are we not men? We are—well, ask Bigfoot, as Brooks does in this delightful yarn, following on his bestseller World War Z (2006).

A zombie apocalypse is one thing. A volcanic eruption is quite another, for, as the journalist who does a framing voice-over narration for Brooks’ latest puts it, when Mount Rainier popped its cork, “it was the psychological aspect, the hyperbole-fueled hysteria that had ended up killing the most people.” Maybe, but the sasquatches whom the volcano displaced contributed to the statistics, too, if only out of self-defense. Brooks places the epicenter of the Bigfoot war in a high-tech hideaway populated by the kind of people you might find in a Jurassic Park franchise: the schmo who doesn’t know how to do much of anything but tries anyway, the well-intentioned bleeding heart, the know-it-all intellectual who turns out to know the wrong things, the immigrant with a tough backstory and an instinct for survival. Indeed, the novel does double duty as a survival manual, packed full of good advice—for instance, try not to get wounded, for “injury turns you from a giver to a taker. Taking up our resources, our time to care for you.” Brooks presents a case for making room for Bigfoot in the world while peppering his narrative with timely social criticism about bad behavior on the human side of the conflict: The explosion of Rainier might have been better forecast had the president not slashed the budget of the U.S. Geological Survey, leading to “immediate suspension of the National Volcano Early Warning System,” and there’s always someone around looking to monetize the natural disaster and the sasquatch-y onslaught that follows. Brooks is a pro at building suspense even if it plays out in some rather spectacularly yucky episodes, one involving a short spear that takes its name from “the sucking sound of pulling it out of the dead man’s heart and lungs.” Grossness aside, it puts you right there on the scene.

Pub Date: June 16, 2020

ISBN: 978-1-9848-2678-7

Page Count: 304

Publisher: Del Rey/Ballantine

Review Posted Online: Feb. 9, 2020

Kirkus Reviews Issue: March 1, 2020

GENERAL SCIENCE FICTION & FANTASY | GENERAL THRILLER & SUSPENSE | SCIENCE FICTION

More by Max Brooks

by Max Brooks

BOOK TO SCREEN

A CONSPIRACY OF BONES

by Kathy Reichs ‧ RELEASE DATE: March 17, 2020

Forget about solving all these crimes; the signal triumph here is (spoiler) the heroine’s survival.

Another sweltering month in Charlotte, another boatload of mysteries past and present for overworked, overstressed forensic anthropologist Temperance Brennan.

A week after the night she chases but fails to catch a mysterious trespasser outside her town house, some unknown party texts Tempe four images of a corpse that looks as if it’s been chewed by wild hogs, because it has been. Showboat Medical Examiner Margot Heavner makes it clear that, breaking with her department’s earlier practice ( The Bone Collection , 2016, etc.), she has no intention of calling in Tempe as a consultant and promptly identifies the faceless body herself as that of a young Asian man. Nettled by several errors in Heavner’s analysis, and even more by her willingness to share the gory details at a press conference, Tempe launches her own investigation, which is not so much off the books as against the books. Heavner isn’t exactly mollified when Tempe, aided by retired police detective Skinny Slidell and a host of experts, puts a name to the dead man. But the hints of other crimes Tempe’s identification uncovers, particularly crimes against children, spur her on to redouble her efforts despite the new M.E.’s splenetic outbursts. Before he died, it seems, Felix Vodyanov was linked to a passenger ferry that sank in 1994, an even earlier U.S. government project to research biological agents that could control human behavior, the hinky spiritual retreat Sparkling Waters, the dark web site DeepUnder, and the disappearances of at least four schoolchildren, two of whom have also turned up dead. And why on earth was Vodyanov carrying Tempe’s own contact information? The mounting evidence of ever more and ever worse skulduggery will pull Tempe deeper and deeper down what even she sees as a rabbit hole before she confronts a ringleader implicated in “Drugs. Fraud. Breaking and entering. Arson. Kidnapping. How does attempted murder sound?”

Pub Date: March 17, 2020

ISBN: 978-1-9821-3888-2

Page Count: 352

Publisher: Scribner

Review Posted Online: Dec. 22, 2019

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Jan. 15, 2020

GENERAL MYSTERY & DETECTIVE | GENERAL THRILLER & SUSPENSE | MYSTERY & DETECTIVE | SUSPENSE | THRILLER | DETECTIVES & PRIVATE INVESTIGATORS | SUSPENSE | GENERAL & DOMESTIC THRILLER

More by Kathy Reichs

by Kathy Reichs

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

The Circle by Dave Eggers – review

I n a recent essay published in these pages, Jonathan Franzen inveighed against what he sees as the glibness and superficiality of the new online culture. “With technoconsumerism,” he wrote, “a humanist rhetoric of ‘empowerment’ and ‘creativity’ and ‘freedom’ and ‘connection’ and ‘democracy’ abets the frank monopolism of the techno-titans; the new infernal machine seems increasingly to obey nothing but its own developmental logic, and it’s far more enslavingly addictive, and far more pandering to people’s worst impulses, than newspapers ever were.”

I cite this because it chimes with the points that Dave Eggers is making in his latest novel, The Circle ; we are at an interesting moment when two such significant figures of American letters have both independently been so moved to expound on the same subject. But my guess is that Eggers won’t suffer the same online crucifixion that has subsequently been Franzen’s fate. Why? Because although Eggers is saying all the same things as Franzen (and so much more), he makes his case not through the often tetchy medium of the essay, but in the glorious, ever resilient and ever engaging form of the novel.

The Circle is a deft modern synthesis of Swiftian wit with Orwellian prognostication. That is not to say the writing is without formal weaknesses – Eggers misses notes like an enthusiastic jazz pianist, whereas Franzen is all conservatoire meticulousness – but rather to suggest that The Circle is a work so germane to our times that it may well come to be considered as the most on-the-money satirical commentary on the early internet age.

This is the story of Mae Holland, a woman in her early 20s, who secures a job at the vast techno-sexy social media company, the Circle, an approximate combination of Facebook, Google, Twitter, PayPal and every other big online conglomerate to whom we have so far trusted our lives. Run by the “Three Wise Men”, the Circle recruits “hundreds of gifted young minds” every week and has been voted “most admired company four years running”. Among their inventions is “TruYou”, a single integrated user interface that executes and streamlines every internet interaction and purchase: “One button for the rest of your life online.” Their philosophy is total transparency and their campus is an architectural essay in glass, a temple to all the geek-chic entertainment and amenities that limitless profits can buy.

Mae is absurdly grateful for the opportunity to work in this brave new world. The novel tracks her own integration into the ethos and activities of the Circle, gradually illuminating a deeply disconcerting vision of how real life might soon be chased into hiding by the tyranny of total techno-intrusion. Mae, herself, ends up suggesting that an account with The Circle should be made mandatory by the government, this being the most effective way to increase vote turnouts.

There is much to admire. The pages are full of clever, plausible, unnerving ideas that I suspect are being developed right now. “SeeChange” is one such: millions of cheap, lollipop-sized “everything-proof” high-resolution cameras with a two-year battery life that can be taped up anywhere so that the video streams can be accessed by all. “This is the ultimate transparency. No filter. See everything. Always.” Meanwhile, there are some fine moments of description – Eggers portrays the mysterious Kalden as a man whose “skinny jeans and tight long-sleeve jersey gave his silhouette the quick thick-thin brushstrokes of calligraphy”.

The book is also very funny. Dan, Mae’s boss, is described as “unshakeably sincere”; he nods “emphatically, as if his mouth had just uttered something his ears found quite profound”. One of my favourite passages describes Mae’s frenzy as she attempts to raise her “PartiRank”, her relative Circle social-participation score, calculated as the result of her digital interactions. After work, therefore, she sits for hours in front of her myriad screens and posts in 11 discussion groups, joins 67 more feeds, replies to 70 messages, RSVPs to dozens of events, signs petitions and provides widespread “constructive criticism” before realising that, in order to make real headway up the ranks, she had better stay up all night and manically comment, smile, zing, join, frown, befriend, invite …

Mae has a boyfriend from her past, Mercer, her main antagonist. Mercer spends hours thinking of ways to “unsubscribe to mailing lists without hurting anyone’s feelings”. He finds that the digital bingeing of the world leaves him “hollow and diminished”, and that there is “this new neediness [that] pervades everything”. Indeed, it is Mercer with whom Franzen might best get along; Mercer feels that he has “entered … some mirror world where the dorkiest shit is completely dominant”, that “the world has dorkified itself”. And it is Mercer’s fate – when Mae tracks him down in hiding using Circle technology – that furnishes the novel with its most kinetic passage of satire.

There are a few weaknesses. Eggers struggles here and there to balance psychological plausibility with the outlandishness of his satirical flourishes; he sometimes needs his characters to behave in ways that seem – certainly when you put the book down – to be wholly implausible. There is also a clumsy metaphorical scene where a shark eats all the other fish in the aquarium tank. But this is a prescient, important and enjoyable book, and what I love most about The Circle is that it is telling us so much about the impact of the computer age on human beings in the only form that can do so with the requisite wit, interiority and profundity: the novel.

- Dave Eggers

- Social media

- Digital media

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

Awesome, you're subscribed!

Thanks for subscribing! Look out for your first newsletter in your inbox soon!

The best of New York for free.

Sign up for our email to enjoy New York without spending a thing (as well as some options when you’re feeling flush).

Déjà vu! We already have this email. Try another?

By entering your email address you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy and consent to receive emails from Time Out about news, events, offers and partner promotions.

Love the mag?

Our newsletter hand-delivers the best bits to your inbox. Sign up to unlock our digital magazines and also receive the latest news, events, offers and partner promotions.

- Things to Do

- Food & Drink

- Time Out Market

- Coca-Cola Foodmarks

- Attractions

- Los Angeles

Get us in your inbox

🙌 Awesome, you're subscribed!

Book review: The Circle by Dave Eggers

Eggers's satire of social media, which might be his 1984 or Brave New World, touches us IRL.

By Dave Eggers. Knopf, $28. From his breakout memoir, A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius , to last year’s National Book Award finalist A Hologram for the King , Eggers’s works pulse with life. His latest novel, The Circle , pushes his art even further; this dive into technology’s intrusive ubiquity is his Brave New World or 1984 . Mae Holland, a 24-year-old idealist working at a gloomy utilities company in her small Californian hometown, calls in a favor with her college roommate and gets a job working at a utopian tech company called the Circle. Think Facebook or Google or Apple, but more impressive and intrusive than all of them combined. As the company asserts its disconcerting global omnipresence, Mae becomes more and more involved until she finds herself the Circle’s head cheerleader. Eggers’s work, part dark comedy, part sobering glimpse into the near-future, stuns for two reasons: Mae’s humanity and compassion are apparent even as she helps erode our civil liberties; and two, it doesn’t feel like science fiction. It feels like the next horrific—but very plausible—small step for mankind.

An email you’ll actually love

[image] [title]

Discover Time Out original video

- Press office

- Investor relations

- Work for Time Out

- Editorial guidelines

- Privacy notice

- Do not sell my information

- Cookie policy

- Accessibility statement

- Terms of use

- Copyright agent

- Modern slavery statement

- Manage cookies

- Claim your listing

- Local Marketing Solutions

- Advertising

Time Out products

- Time Out Worldwide

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- What Is Cinema?

- Newsletters

Book Review: The Circle , Dave Eggers’s Chilling, New Allegory of Silicon Valley

By Lauren Christensen

McSweeney’s founder and former Pulitzer finalist Dave Eggers today publishes his latest work of fiction, The Circle (Knopf). In it, the famously staunch defender of the printed page allegorizes the Digital Age as a pseudo-theological cult, issuing a grave—and page-turning—warning about the perils of a society obsessed with technology.

The story follows young and impressionable Mae as she navigates a new job at The Circle, an eerily familiar-sounding Silicon Valley corporation that’s known for its immense resources and relentless ambition. At The Circle’s sprawling campus—which Mae considers a “utopia” where “all had been perfected”—employees are indoctrinated in the company ideals of constant connectivity, transparency, and accessibility.

At first, The Circle’s mantra of an inclusive community sounds nurturing and forward-thinking, particularly compared with the dreary job Mae has left behind in her hometown, at the cement building of a utility company, which “felt like something from another time, a rightfully forgotten time.” But as our starry-eyed heroine makes her way around The Circle, the reader begins to sense Eggers’s implicit denunciation of the company culture: boundary-less communication can cause paranoia and hypersensitivity among those who attempt it, and can give the people who facilitate it utter control. The social message of the novel is clear, but Eggers expertly weaves it into an elegantly told, compulsively readable parable for the 21st century.

Mae’s official role at The Circle is in its so-called customer-experience department, where she answers clients’ questions and is expected to aim for a satisfaction rating of 100 percent. But, as Mae soon learns, her duties at the company extend far beyond this job description. Punished for traveling home for the weekend to visit her ailing father without keeping the Circle community constantly apprised of her whereabouts via social media, Mae naïvely acquiesces to the new demands, not worrying, as the reader does, that she’s putting her basic human autonomy at risk. Later, she fails to notice when her closest friend and co-worker Annie cracks under The Circle’s unrelenting pressure and the humiliation that can come from complete visibility. And, most tragically, her ex-boyfriend meets a horrific fate after Mae rejects his skepticism about the company’s vision.

Mae, meanwhile, walks the line of indoctrination and disillusionment until the novel’s closing pages. The protagonist is at last forced to choose between the prospect of “completing” the Circle and recognizing its hollowness when she discovers the truth about a mysterious and alluring fellow Circler, Kalden.

What may be the most haunting discovery about The Circle, however, is readers’ recognition that they share the same technology-driven mentality that brings the novel’s characters to the brink of dysfunction. We too want to know everything by watching, monitoring, commenting, and interacting, and the force of Eggers’s richly allusive prose lies in his ability to expose the potential hazards of that impulse. There might be hope for us after all, though, for the simple fact that we’ve just been reading a work of literary fiction and not a 140-character tweet or zing. Even if some of us did download it on an e-reader.

By Savannah Walsh

By Bess Levin

By Gabriel Sherman

Lauren Christensen

Cocktail hour.

By signing up you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Faith Cummings

By Joy Press

By Richard Lawson

By Keziah Weir

‘The Circle’ by Dave Eggers

When I finished reading Dave Eggers's chilling and caustic novel, "The Circle," I felt like disconnecting from all my online devices and retreating for a while into an unplugged world. I gather that's what he had in mind.

Eggers displayed a scrappy ironic side in "A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius," his 2000 memoir about raising his younger brother after their parents died of cancer. He has written with finesse and empathy from the perspective of a "Lost Boy" forced to fight in Sudan's civil war ("What Is the What," 2006), a Syrian businessman caught up in a post-Katrina nightmare ("Zeitoun," 2009), and a failing American salesman suspended in a desert limbo, hoping to cut a deal with a Saudi monarch ("A Hologram for the King," 2012). "The Circle" is his most satiric work, with shades of Orwell, Swift, Voltaire, even Mary Shelley's "Frankenstein,'' in his dark vision of an insatiable Internet monopoly that breaches the barrier between public and private.

Advertisement

The novel opens as Mae Holland, 24, begins her first day of work at the Circle, a slightly futuristic amalgam of the social-media and personal-tech companies that have emerged over the past decade, from Google to Facebook, Twitter and Square. Mae is enchanted. "My God, Mae thought. It's heaven. The campus was vast and rambling, wild with Pacific color, and yet the smallest detail had been carefully considered, shaped by the most eloquent hands."

The 400-acre Circle campus seems like a mash-up of the Googleplex and Disney World, with a picnic area, tennis courts, clay and grass, organic gardens, and towering brushed steel and glass structures with names like Renaissance, Enlightenment, and Cultural Revolution.

On Dream Fridays Mae gets glimpses of "the Wise Men," the trio at the top of the Circle — avuncular Eamon Bailey, ruthlessly capitalistic CEO Tom Stenton, and, via video, reclusive young founder, Ty Gospodinov, who usually wears an oversized hoodie. Ty devised a unified operating system, which combined all users' needs and tools into one TruYou account — e-mail, social networking, banking, and purchasing. "TruYou changed the Internet, in toto, within a year," Eggers writes.

The novel unfolds in an ever accelerating narrative flow. On her first day answering online customer questions, Mae is instructed to score 98 to 100 percent satisfaction on follow-up surveys. By her second week she is supervising a group of newbies. Within a month she is staying up all night to post continuously on the company's social networks after being criticized because her Participation Rank was low. She discovers that the community-building after-work and weekend events — concerts, circuses, theme nights, and all-night parties — are obligatory. And there's a dorm for those who don't want to go home.

Like a modern-day Candide, Mae maintains an optimistic front as she submits to the Circle's increasingly invasive demands. But her impulsive side leads her to take surprising risks. A nerdy coworker videotapes their wine-soaked sexual encounter (the Circle does not delete, she learns). And she enters into a clandestine on-campus affair with a mysterious, wiry, grey-haired man who calls himself Kalden. This relationship grows ever odder.

Back home, her high school boyfriend calls Mae's new colleagues "Digital Brownshirts," and her parents struggle with an insurance quagmire as her father is treated for multiple sclerosis. Mae's parents end up on the Circle's health plan. A miracle? Not exactly, as it turns out.

At the novel's midpoint, as Mae sinks deeper into the cult-like culture of the Circle, Bailey and Stenton begin rolling out newly minted Circle inventions, like SeeChange cameras the size of lollipops planted at Tahrir Square, along beachfronts, and in private homes.

A congresswoman goes "transparent," wearing a camera around her neck and allowing a live feed of her workdays to go online. Within weeks, 80 percent of politicians have followed her, leaving the other 20 percent to fight public perception they must have something to hide. Bailey and Stenton suggest that paying taxes, voter registration, even voting, should be woven into each individual's mandatory TruYou identity and constantly monitored. (If you don't vote, your TruYou account is frozen.) The developers get to work.

Like a concerned uncle, the smooth-talking Bailey coaxes Mae into making statements highlighted onscreen during a Dream Friday chat: "SECRETS ARE LIES. CARING IS SHARING. PRIVACY IS THEFT." Then he announces that Mae, "in the interest of all she saw and could offer the world," would be going transparent immediately. Soon she accumulates millions of followers whose opinions she tracks from a wrist-mounted screen in a continuous flow of smiles, frowns, and zings. Closing the Circle, with mass birth-to-death transparency, becomes the new corporate goal.

Exhausted, Mae has a brief "blasphemous flash" that "the volume of information, of data, of judgments, of measurements, was too much, and there were too many people, and too many desires of too many people and too many opinions of too many people, and too much pain . . . and having all of it constantly collated, collected, added and aggregated, and presented to her as if that all made it tidier and more manageable — it was too much." Indeed.

"The Circle'' reads as if it were written in an urgent rush, just barely ahead of the headlines. Its ending comes as abruptly as one character's drive off a bridge. We are, Eggers warns, at a pivot in history. "There used to be the option of opting out. But now that's over.'' It's a "totalitarian nightmare," he writes."Everyone will be tracked, cradle to grave, with no possibility of escape."

"The Circle" is biting, even vicious at times. Despite the polemics, Eggers raises timely questions about transparency, privacy, democracy, and the sinister side of the Internet. And he offers a corrective, in Kalden's manifesto, "The Rights of Humans in a Digital Age." "Not every human activity can be measured," Eggers writes.

The list ends with a plea: "We must all have the right to disappear."

Jane Ciabattari is vice president/online and former president of the National Book Critics Circle. Reach her at [email protected] .

Review: The Circle by Dave Eggers

- Post published: August 13, 2018

- Post last modified: August 25, 2022

The Circle by Dave Eggers Summary

This post may contain affiliate links, meaning that if you buy something, I might earn a small commission from that sale at no cost to you. Read my full disclosure here .

When Mae Holland is hired to work for the Circle, the world’s most powerful internet company, she feels she’s been given the opportunity of a lifetime. The Circle, run out of a sprawling California campus, links users’ personal emails, social media, banking, and purchasing with their universal operating system, resulting in one online identity and a new age of civility and transparency. As Mae tours the open-plan office spaces, the towering glass dining facilities, the cozy dorms for those who spend nights at work, she is thrilled with the company’s modernity and activity. There are parties that last through the night, there are famous musicians playing on the lawn, there are athletic activities and clubs and brunches, and even an aquarium of rare fish retrieved from the Marianas Trench by the CEO. Mae can’t believe her luck, her great fortune to work for the most influential company in the world–even as life beyond the campus grows distant, even as a strange encounter with a colleague leaves her shaken, even as her role at the Circle becomes increasingly public. What begins as the captivating story of one woman’s ambition and idealism soon becomes a heart-racing novel of suspense, raising questions about memory, history, privacy, democracy, and the limits of human knowledge.

The Circle by Dave Eggers Review

So I just finished watching the movie, because even though people had warned me away from it, I saw Emma Watson and couldn’t help myself. She was the only redeeming part, so this is me warning you: Don’t watch the movie, y’all. Just don’t. The book version of The Circle is far better and very worth your time.

Ironically, seeing the trailer in theaters was the first time I had even heard of The Circle , which prompted me looking it up and realizing it was a book first. Then, as usually happens, I noticed that a bunch of my favorite book people had brought it up in the past and loved it, so I jumped on board (late, per usual), and I’m so glad I did.

The Circle by Dave Eggers was one of the most gripping books I’ve read in a bit. This might be kind of unusual for a reader, but I don’t have the best attention span. Typically a book of this length will take me a bit of time, but I breezed through it in a couple of sittings.

The one thing that threw me was that this book doesn’t have chapters, and, as I mentioned, I’m pretty distractible, so not having a super-easy way to gauge where I am in the book was a bit off-putting.

Eggers, though, does an amazing job of drawing you in. If you’re familiar with my TV references, the book starts off very Silicon Valley , but quickly turns into Black Mirror . In other words, the tech drew me in, but then the sheer creepiness of the whole thing slipped up behind me and blocked the exit.

The story follows average twenty-something Mae after her college roommate helps her get a job at one of the hottest companies in the world, the Circle. Soon, what started off as a beginner’s job in customer service (or “Customer Experience,” as the Circlers call it), turns into very public role, one filled with unseen dangers, lots of shiny new tech, and eventually, possibilities such as the “perfect democracy.”

While a lot of it, admittedly, might seem far-fetched, there is the perfect amount of humanity injected into the story. Take, for instance, Mae’s family: her father, struggling with a recent MS diagnosis, and her mother, left to battle the insurance companies alone. There is also Mercer, an ex-boyfriend and family friend who is wary of the Circle from the start.

I think one of the biggest complaints I heard about this one was that many people believed it to be predictable, and I’ll give you that in some respects. The Circle really doesn’t contain anything you don’t already know about tech, social media, and monopolies, and gives you what you expect. However, I think that’s the point.

While Eggers is pointing out the dangers here, he is also showing just how easy it is to slip into them, all the positives, all the arguments that can box someone into a corner, into believing that they are helping humanity. It is easy (and this might be a mild spoiler) to watch Mae fall into the deep end of this whole thing, and that is the scary part, that is what kept me so interested in reading this book.

All-in-all, I would say this isn’t one to be missed (as I so obviously did a couple years back). If you are a geek for cool tech, like I am, it is a must, and you’ll surely be caught up just in all the free stuff Mae gets.

If you’re looking for a slightly shorter book by Dave Eggers, check out my review of his novella The Captain and the Glory . Once again, Dave Eggers proves to be one of the most clever writers around.

(Update 2022: Since this review, Dave Eggers has published a sequel to The Circle called The Every, which tells the story of a woman going to work for the company born of a merger with The Circle. I, for one, am dying for a chance to read this. I wrote this post over four years ago and have since converted to being a big Dave Eggers fan.)

See y’all soon,

<img src=”https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56f84c727c65e4881ffa9b43/1624649731637-XB3OH55JXV74PXKSU2FB/newsignature.png” alt=”newsignature.png”>

Share this:

You might also like.

Review: The Reason You’re Alive by Matthew Quick

Review: an absolutely remarkable thing by hank green.

Review: The Arc by Tory Henwood Hoen

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

(I will not sell your data.)

Advertisement

More from the Review

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Best of The New York Review, plus books, events, and other items of interest

- The New York Review of Books: recent articles and content from nybooks.com

- The Reader's Catalog and NYR Shop: gifts for readers and NYR merchandise offers

- New York Review Books: news and offers about the books we publish

- I consent to having NYR add my email to their mailing list.

- Hidden Form Source

April 18, 2024

Current Issue

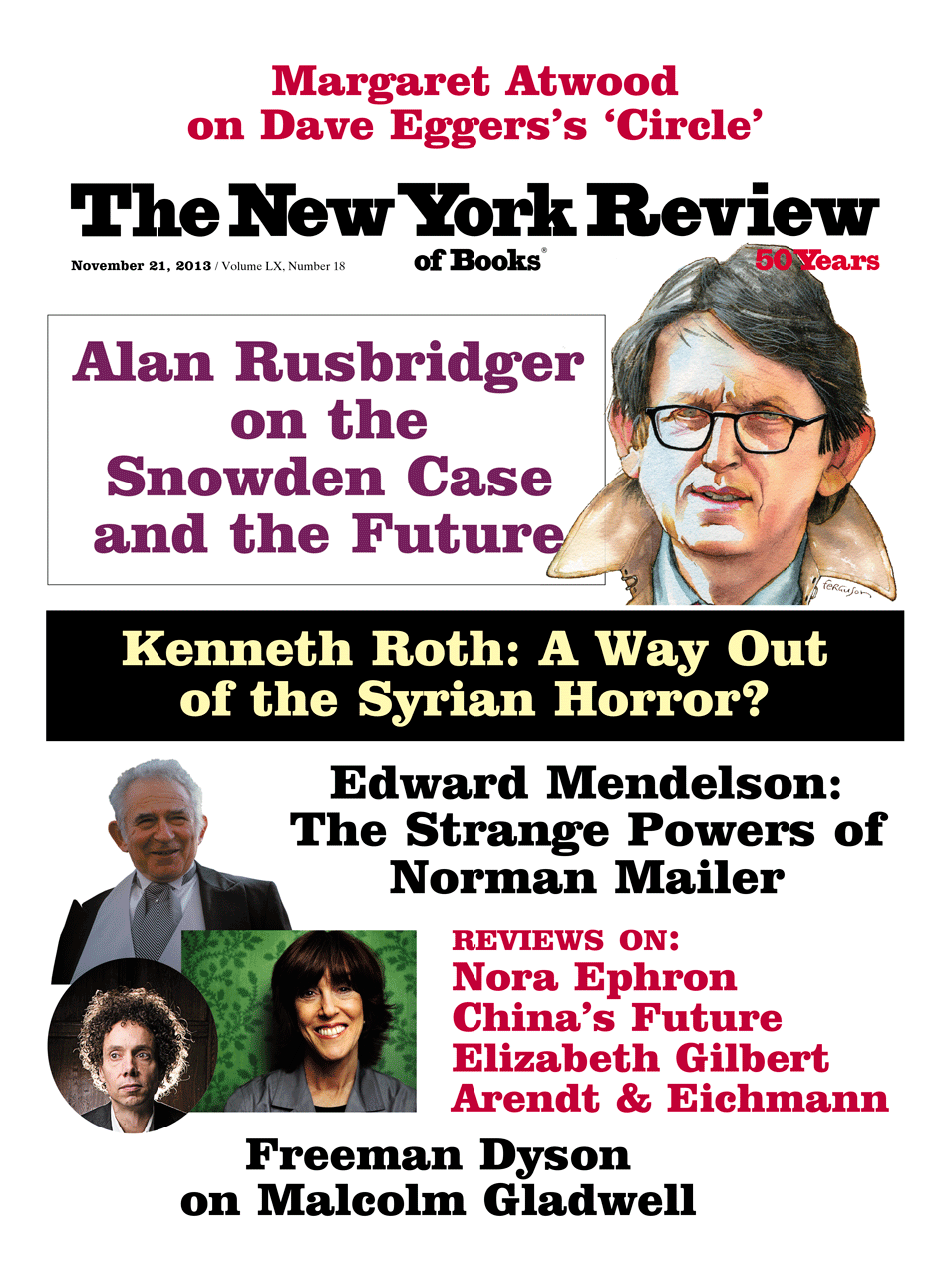

When Privacy Is Theft

November 21, 2013 issue

Submit a letter:

Email us [email protected]

Robert Gumpert/NB Pictures/Contact Press Images

Dave Eggers, 2007

The Circle is Dave Eggers’s tenth work of fiction, and a fascinating item it is.

Eggers’s first major book was the much-acclaimed semifictional memoir A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius (2000), which recounts the struggles of Eggers to raise his younger brother after the death of their parents. By that time he was already active in the underground worlds of comic strip writing, small-magazine founding, and columnizing in the then-embryonic realm of online magazines. He has continued along a multibranched road that has included the founding of McSweeney’s magazine and publishing house, and an associated monthly, The Believer ; of 826 Valencia, a youth literacy charity; and of ScholarMatch, connecting non-rich college-age kids in the San Francisco Bay Area with donors.

Then there’s the writing: the screenplays, the journalism, and, of course, the books. These include two unflinching looks at man’s inhumanity to man, in Africa and America respectively— What Is the What and Zeitoun —and the novel A Hologram for the King , which glances at the decline of America’s international clout through the eyes of a sad salesman. Eggers appears to run on pure adrenaline, and has as many ideas pouring out of him as the entrepreneurs pitching their inventions in The Circle .

The outpouring of ideas is central to The Circle , as it is in part a novel of ideas. What sort of ideas? Ideas about the social construction and deconstruction of privacy, and about the increasing corporate ownership of privacy, and about the effects such ownership may have on the nature of Western democracy. Dissemination of information is power, as the old yellow-journalism newspaper proprietors knew so well. What is withheld can be as potent as what is disclosed, and who can lie publicly and get away with it is determined by gatekeepers: thus, in the Internet age, code-owners have the keys to the kingdom.

Marshall McLuhan was among the first to probe the effects of different kinds of media on our collective consciousness with The Gutenberg Galaxy (1962) and Understanding Media (1964). Even then, before interactive technologies, he pointed out that “the global village” could be an unpleasant and claustrophobic place. As far back as 1835, Toqueville’s Democracy in America predicted the tyranny of public opinion, a tyranny that can be amplified immeasurably via the Internet.

The concerns that underlie The Circle are therefore of long standing, but have been much discussed recently, not only in newspapers and magazines both online and off, but in books. Misha Glenny has written eloquently about cybertheft and cybercrime in McMafia and DarkMarket , and, in Black Code , Ronald Deibert has detailed various cyberthreats to democracy and privacy. In The Boy Kings , a 2012 memoir that chronicles the early days of Facebook, Katherine Losse questioned the desirability of making personal information public.

This, then, is the “real” world to which Eggers holds up the mirror of art in order to show us ourselves and the perils that surround us. But The Circle is neither a tract nor an analysis but a novel, and novels always tell the stories of individuals. In genre this novel partakes of the Menippean satire—distinct from social satire in viewing moral defects less as flaws of character than as intellectual perversions. It also incorporates passages of symposium-like Socratic dialogue by which the central character is manipulated, through rational-sounding questions and answers, into performing the increasingly outrageous acts that logic demands of her.

Some will call The Circle a “dystopia,” but there’s no sadistic slave-whipping tyranny on view in this imaginary America: indeed, much energy is expended on world betterment by its earnest denizens. Plagues are not raging, nor is the planet blowing up or even warming noticeably. Instead we are in the green and pleasant land of a satirical utopia for our times, where recycling and organics abound, people keep saying how much they like each another, and the brave new world of virtual sharing and caring breeds monsters.

The Circle takes its name most immediately from a fictional West Coast social media corporation that has subsumed all earlier iterations such as Google, Facebook, and Twitter. It traces the rise and rise within this company of its female protagonist, Maebelline, a name that closely resembles that of a brand of mascara, thus hinting at masks and acting. (Names matter in The Circle because they matter both to its author and to its characters, some of whom go so far as to pick out new ones for themselves from the Internet.) Maebelline is commonly called “Mae,” and this nickname is then expanded by a coworker who’s bringing Mae up to speed on her Circle duties. She’s opened a “Zing” account for Mae—zinging being an amalgamation of tweeting, texting, and pinging. “I made up a name for you,” says Gina.

“MaeDay. Like the war holiday. Isn’t that cool?”

Mae wasn’t so sure about the name, and couldn’t remember a holiday by that name.

Clever Mr. Eggers. There is no real war holiday called MaeDay, but “Mayday”—from the French m’aidez —is a venerable distress signal. May Day was once a pagan springtime celebration, but was adopted in the nineteenth century as a workers’ holiday. It was then appropriated for military parades during Stalinism, a period noted for its hyperactive secret police, and satirized in Orwell’s 1984 , a work that is echoed more than once in The Circle. Maebelline, Zing-christened as MaeDay: a makeup accessory, a distress signal, a totalitarian power-show. The reader feels a pricking of the thumbs.

At first Mae is winsomely innocuous. She’s recently been an Everygirl stuck in her own version of purgatory, the humiliating McJob in the gas and energy utility of her small hometown in California that she took out of the need to pay off her crushing college debts. Now she’s called back from the living dead by her college roommate turned Circle higher-up, Annie. Annie too is significantly named: Annies get their guns, being competitive, perky sharpshooting tomboys; they’re Orphan Annies, brave and adventurous and protected by Daddy Warbucks, who uses his wealth for Good. This Annie is a golden-girl scatterbrained “doofus” who slouched around at college in men’s flannel trousers, but then, after a Stanford MBA , was recruited into the Circle and has been soaring like a helium balloon, adored by all.

Annie comes from money and family class—Mayflower rather than MaeDay—not that eye-rolling Annie claims to take her aristocratic descent seriously. None of her privilege has been lost on second-fiddle Mae, who, as she enters the Circle, is suffused with gratitude toward Annie and wonderment at being actually there, part of “the only company that really mattered at all”; but as the reader may anticipate, an All About Eve girl-on-girl mud-wrestling glint soon flickers in her star-bedazzled eyes.

Eggers sets forth the players and ground of his novel right at the beginning, like a gamer setting up the board. The Circle, we learn, is run by a triumvirate known as the Three Wise Men. Like Melville’s Pequod and Stephen King’s Overlook Hotel, the Circle is a combination of physical container, financial system, spiritual state, and dramatis personae, intended to represent America, or at least a powerful segment of it; so these three, like Melville’s three harpooners, are emblematic.

Tyler Alexander Gospodinov, known as Ty, is the “boy-wonder visionary” founder who, by inventing a system called TruYou, did away with passwords and fake identities and trolls, not because he wished to take over the world, but because he wanted things to be simpler and more transparent. The most telling element of his name is “Alexander”—the Great, of course, but also he who wept because he had no more worlds to conquer. Elusive Ty is seldom seen about the place except as an image on a screen, a hoodie pulled over his head. In the Circle, where the alleged mission is to render everyone and everything visible, he is hidden, shadowy: no one ever knows what he’s planning next.

The second Wise Man is Eamon (“rich protector”) Bailey (as in Barnum). A Notre Dame graduate, he’s the company’s genial, uncle-ish public face, combining the flair of a showman with the suave persuasiveness of a Jesuit. “Loved by all,” says Annie, “and I think he really loves them back.” That “I think” should give Mae pause, but it doesn’t.

The third Wise Man is Tom Stenton. In literature, Toms are often scamps and boundary pushers, as are Toms Thumb, Kitten, Brown, and Jones; or they may be pig stealers, as in the nursery rhyme, or rich thugs, as in The Great Gatsby , or even imps or evil geniuses, as in Tom Tit-Tot and Tom Riddle, respectively. A Tom coupled with a Stenton (“stone enclosure”) is likely to be a hard customer. So it is with this shark-like Tom, the CEO , who revels in his money and influence, fights the company’s battles and squashes its enemies, and has eyes that are “flat, unreadable.”

Serving under the Three Wise Men are the members of the inner circle, known jokingly as “the Gang of Forty.” This might seem a nod to the Chinese Gang of Four, but there’s more to it: in scripture, forty is a highly significant number. It rained for forty days and forty nights during Noah’s flood, Moses spent forty years in the wilderness, and Jesus fasted for forty days while being tempted by the Devil, who offers him the world in exchange for his soul. “Forty” signifies a period of trial and testing, with high stakes in the balance, and not only Mae but Annie are indeed tested throughout the novel.

These, then, are the major players of The Circle. There are a lot of small fry, and even some “plankton”—outsiders who pitch their ideas, hoping to be hired. They are the krill on which the larger fish graze, and yes, the marine life metaphors culminate in a Big Metaphor. Not for nothing does the Circle possess a large glass aquarium.

Next comes the physical layout or “campus,” described in lavish, enchanting detail: readers of lifestyle sections will salivate over the adjectives, and are sure to make comparisons between what’s on offer here and what real life has already provided on other such company “campuses.” The Circle’s security walls enclose a paradise of green spaces, buildings, fountains, artworks, and game spaces, with luxurious dormitories for those who may wish to work late and stay overnight, not that there’s any pressure, mind you. The restaurants dish up gourmet but virtuous food, the parties are übercool, and there’s a sample room full of products that their manufacturers are dying to have the trend-setting Circlers adopt.

The different buildings are named after historical periods: the Dark Ages, the Renaissance, and the like. (He who controls the past controls the future and he who controls the present controls the past, as 1984 puts it.) Artists, both starving and otherwise, are brought in to entertain, like the troubadours in the Middle Ages or Voltaire at the court of Frederick the Great; for such corporations are the modern equivalent of kingdoms and Renaissance dukedoms. Lest we miss the point, there’s a marvelous collection in the Circle, assembled by Bailey, who, despite his folksiness, is a “connoisseur.” He’s amassed all kinds of obsolete objects, such as leather-bound books and green-shaded reading lamps, loot he’s bought from “distressed estates”—the losers of capitalism, we gather. If you hear an echo of rich financier and art collector Adam Verver from Henry James’s The Golden Bowl , you might be correct: one of the things money buys is the past, all the better to gloat over it.

The palatial buildings are made of glass, ostensibly to underline the Circle’s mantra of “transparency”—everyone should be open to everyone else in all ways, a goal within the Circle’s reach thanks to the ingenious schemes and doodads cooked up by its collective brain trust: the tiny “SeeChange” cameras that can be planted everywhere (no more rapes and atrocities!), the scheme to embed tracking chips in children’s bones (no more kidnapping!). Why wouldn’t any sane person want those things? People who live in glass houses not only shouldn’t throw stones—they can’t throw them! Isn’t that a good thing? And if you have nothing to hide, why get paranoid?

But literary structures of glass, or its close cousin, ice, are never reassuring. Glass buildings are halls of mirrors where one may become lost; or they are illusions that easily melt or shatter; or they are prisons that permit others to look at you unchecked, like the glass cage in which Billy Pilgrim is kept by the Tralfamadorians in Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five . The glass buildings in Yevgeny Zamyatin’s 1924 novel We —precursor of both Brave New World and 1984 —allow the totalitarian police to snoop on everyone all the time. To see everything without being seen is, needless to say, the prerogative of the biblical God whose eyes run everywhere, as well as the labor of spies and surveillance agencies, and the fondest desire of the voyeur.

As we move deeper into The Circle we may recall the Snow Queen’s palace in the Hans Andersen tale, where hearts are frozen, the cold queen rules from her throne on the Mirror of Reason, and the puzzle of “eternity” cannot be solved without love. We may also be reminded of the “stately pleasure dome” from Coleridge’s poem “Kubla Khan,” “a sunny pleasure-dome with caves of ice.” The poet dreams of recreating this fabled edifice through art, but others find something demonic about his enterprise. “Weave a circle round him thrice,” they chant. The woven circle is to protect others from him, because he’s entranced; in modern parlance he’s been drinking the Kool-Aid and is, like, totally out of his mind.

Which brings us to circles. Both the reader and Mae encounter the Circle first through its logo, which is obligingly depicted on the book’s cover and then described through Mae’s eyes: “Though the company was less than six years old, its name and logo—a circle surrounding a knitted grid, with a small ‘c’ in the center—were already the best-known in the world.” Looked at by someone unfamiliar with it, the logo would surely suggest a manhole cover. I certainly hope Eggers intended this: as a flat disc, the thing might imply a moon or a sun or a mandala—something shining and cosmic and quasi-religious—but as a portal to dark, sulphurous, Plutonian tunnels it is much more resonant.

The circle motif may be Eggers’s wink at Google’s “Circles,” a way of arranging your contacts on its counterpart to Facebook: but it’s much more than that. The circle is an ancient symbol that’s had a variety of incarnations. There are divine circles—the Egyptian sun, the vision of the poet Henry Vaughan, who “saw Eternity the other night,/Like a great ring of pure and endless light”; in case we overlook the point, inside Eamon Bailey’s private lair is a stained glass ceiling with “countless angels arranged in rings.” Bailey himself weighs in on circles: “A circle is the strongest shape in the universe. Nothing can beat it, nothing can improve upon it, nothing can be more perfect. And that’s what we want to be: perfect.” A man with Bailey’s Catholic background should know that he’s verging on heresy, since perfection belongs to God alone. He ought to know also that circles can be demonic: Dante’s Inferno has nine circles. Maybe he does know those things, but has discounted them.

As the story advances, our view of the Circle moves from bright to dark to darker. At first, viewed through Mae’s eyes, the place seems wondrous:

The rest of America…seemed like some chaotic mess in the developing world. Outside the walls of the Circle, all was noise and struggle, failure and filth. But here, all had been perfected. The best people had made the best systems and the best systems had reaped funds, unlimited funds, that made possible this, the best place to work. And it was natural that it was so, Mae thought. Who else but utopians could make utopia?

But if this is utopia, why is Mae so anxious most of the time? True, her workload in “Customer Experience” is crushing, as she answers questions, sends “smiles” and “frowns”—the Circle equivalent of Likes and Dislikes and Favorites—to other websites and accounts, fields an avalanche of messages and invitations from other Circlers, and is under increasing pressure to spend all her time “participating.” But her main terror is being cast out of the Circle: she’ll do almost anything to stay inside, and worries constantly about what sort of impression she’s making. Is she getting enough approval, a substance she measures by messages, Zings, “smiles,” and online watchers? Is she making the grade?

The Circlers’ social etiquette is as finely calibrated as anything in Jane Austen: how fast you return a Zing or your tone of voice when saying “Yup” can matter deeply, and missing someone’s themed party is a lethal snub. Every choice is tracked and evaluated, every “aesthetic” ruthlessly judged. The nineteenth-century art critic John Ruskin—who famously said, “Tell me what you like and I’ll tell you who you are”—viewed bad taste as a moral offense, and the young Circlers subscribe to this dogma: nothing gets you the brushoff more quickly than a pair of uncool jeans. Utopia, it seems, is an awful lot like high school, but with even more homework.

Just as there are Three Wise Men, there are also Three Inadequate Boyfriends: a conforming wanker who wants to post recordings of his ersatz sex with Mae online; a hapless, arts-and-crafts Jiminy Cricket conscience from her previous life who tries to warn her about the unreality and inherent totalitarianism of the Circle’s proceedings; and a mysterious, sexually charged older man who pops in and out of tunnels like the Phantom of the Opera. It’s this third one who plays demon lover to the Circle’s sunny pleasure dome, and who shows Mae the caverns measureless to man, in this case the underground river cave in which people’s total data profiles—call them souls—are stored in red boxes. His name—not his real one—is Kalden, Tibetan for “of the golden age.” Point being: the golden age is over.

Eggers treats his material with admirable inventiveness and gusto. The plot capers along, the trap doors open underfoot, the language ripples and morphs. Why has he not been headhunted by some corporation specializing in new brand names? Better than reality, some of these, and all too plausible. But don’t look to The Circle for Chekhovian nuance or thoroughly rounded characters with many-layered inwardness: it isn’t “literary fiction” of that kind. It’s an entertainment, but a challenging one: it demands that the reader think its positions through in the same way that the characters must. Some of its incidents are funny, some of them are appalling, and some of them are both at once, like a nightmare in which you find yourself making a speech with no clothes on.

And there’s quite a lot of that: who has the right to see whose dangly bits, and under what circumstances? If everything must be accessible to everyone else—if you’re on camera all the time, so to speak—what times and places can be private, apart from sex and bathroom functions? Sure enough, it’s not long before sex is taking place in toilet cubicles, though not for the first time in either literature or life. Private communication is driven in there too, and those aware of the fact that all their e-mails are potentially monitored—and who can be more aware of that potential than the Circlers?—are driven back on a pitiful Stone Age technology: the note scribbled with some obsolete mark-making device on that despised substance, paper.

But apart from the moments of almost farcical discovery—among them the discovery by the characters themselves that there is indeed such a thing as TMI , or Too Much Information—Eggers has a serious purpose, or several. One of them is to remind us that we can be led down the primrose path much more blindly by our good intentions than by our bad ones. (He’s entitled to speak about good intentions, having manifested so many of them himself, in his various other lives.) A second may be to examine the nature of looking and being looked at.

A face with a direct gaze is said to be one of the first images a baby recognizes. It’s a primary pattern. The human gaze, when languorous, is much celebrated in love poetry, but a blank or hostile stare is intimidating at the biological level. Who can look at whom, and at what, informs not only the parental admonition “Don’t stare” and the insulting childhood challenge “Who’re you looking at?” but a wide range of other human behaviors, from the use of mandatory body and head coverings to PG labels on films to Peeping Tom legislation. “Don’t make a spectacle of yourself,” kids used to be told; but in the world of the Circle, people must make spectacles of themselves: to refuse to do so is selfish, or, as Bailey leads Mae to declaim, PRIVACY IS THEFT .

Publication on social media is in part a performance, as is everything “social” that human beings do; but what happens when that brightly lit arena expands so much that there is no green room in which the mascara can be removed, no cluttered, imperfect back stage where we can be ‘“ourselves”? What happens to us if we must be “on” all the time? Then we’re in the twenty-four-hour glare of the supervised prison. To live entirely in public is a form of solitary confinement.

November 21, 2013

The Snowden Leaks and the Public

The Strange Powers of Norman Mailer

Subscribe to our Newsletters

More by Margaret Atwood

November 6, 2018

September 24, 2015 issue

May 6, 2013

Margaret Atwood is the author of more than forty books of fiction, poetry, and critical essays, including the 2000 Booker Prize–winning The Blind Assassin ; Alias Grace , which won the Giller Prize and the Premio Mondello; The Robber Bride , Cat’s Eye , The Handmaid’s Tale , and The Penelopiad . Her latest work is a book of short stories called Stone Mattress: Nine Tales (2014). Her newest novel, MaddAddam (2013) is the third in a trilogy comprising The Year of the Flood (2009) and the Giller and Booker Prize–nominated Oryx and Crake (2003). Atwood lives in Toronto with the writer Graeme Gibson.

V. S. Pritchett, 1900–1997

April 24, 1997 issue

‘Animal Farm’: What Orwell Really Meant

July 11, 2013 issue

February 1, 1963 issue

November 19, 2020 issue

February 11, 2021 issue

November 5, 2020 issue

Corn Crowfoot, Corn Buttercup

April 9, 2020 issue

Evening Trains

February 27, 2020 issue

Subscribe and save 50%!

Get immediate access to the current issue and over 25,000 articles from the archives, plus the NYR App.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Book Review: The Circle, by Dave Eggers

Dave Eggers asks the right questions in the wrong ways in The Circle

You can save this article by registering for free here . Or sign-in if you have an account.

Article content

If you are under the age of 30, you will probably not enjoy The Circle . It is a book about the Internet, social media and consumer technology that is so utterly wrong , you’ll feel compelled to take to Facebook, Twitter and Tumblr to catalogue all the ways.

Book Review: The Circle, by Dave Eggers Back to video

Of course, you would also be proving author Dave Eggers’ point. The Circle is a book about a company of the same name, a sprawling, idealistic mash-up of Google, Facebook, Twitter and all of the Internet’s most popular bits, but inflated to levels of hyper-connectedness of which even the most plugged-in teen could scarcely dream.

Enjoy the latest local, national and international news.

- Exclusive articles by Conrad Black, Barbara Kay, Rex Murphy and others. Plus, special edition NP Platformed and First Reading newsletters and virtual events.

- Unlimited online access to National Post and 15 news sites with one account.

- National Post ePaper, an electronic replica of the print edition to view on any device, share and comment on.

- Daily puzzles including the New York Times Crossword.

- Support local journalism.

Create an account or sign in to continue with your reading experience.

- Access articles from across Canada with one account.

- Share your thoughts and join the conversation in the comments.

- Enjoy additional articles per month.

- Get email updates from your favourite authors.

Don't have an account? Create Account

In this world, everything is liked, shared, commented on and captured by its users thousands of times per day, and to not swim in this constant, crashing, digital ocean is to be perceived as anti-social — as weird. On the surface, it’s a scathing and arguably obvious commentary on how we — the collective, digital “we” — apparently now live our lives. But below Eggers’ imagined deluge of likes and tweets, more interesting topics sadly remain untouched.

Our proxy for this descent into digital excess is a young woman named Mae Holland, who moves from small-town obscurity to entry-level Circle employee thanks to the influence of a Circle executive and old friend. We see Mae climb up the ranks of the company, absorbed into its culture — and as Eggers no doubt intends — witness the havoc such networks and services are apparently wreaking upon our relationships, our ideals, and our expectations of privacy and self.

Key to this vision is The Circle ’s embodiment of common Silicon Valley stereotypes and tropes. We are reminded, constantly, that most Circlers — a play on Googlers — are in their twenties. There is the Mark Zuckerberg-like autistic-savant founder, swaddled in hoodies and toques, flanked by a pair of slick co-executives that direct The Circle towards any number of eccentric, world-changing pursuits — location-aware bone implants that promise to eliminate child abductions, or deep-sea subs capable of surviving the depths of the Marianas Trench. Employees embrace the quantified self movement, using wearable technology to track their health, location history and social engagement in real time. Tablets and smartphones are always cutting-edge, employees spread data across nine screens or more, retinal computing is apparently common place and everything — everything — is stored, permanently, un-deletable, in the cloud.

There is the sprawling, self-contained campus in a fictional suburban south Californian town, with tennis courts and medical clinic and dorm rooms and concerts and kitchens staffed with professional chefs all conveniently splayed on site. And this is to say nothing of the search queries, emails, instant messages, tweet-like analogs called Zings, online payments, surveys, smiles, frowns, petitions and protests that course through The Circle’s digital, circuitous veins.

It is all perfect distillation of the promise and excess of modern industry giants — less fiction than an honest, selective portrayal of the reality of working in present day tech.

Quite early on, the subtext of this wonderment becomes clear: here is a company that does so much, controls so many things, that it has practically become the underpinning of society itself. That, Eggers posits, is what should scare us most of all. But it reads like a less compelling 1984 for the Internet set — a totalitarian future fallen victim to its own utopian ideals, where Googley mantras such as “ALL THAT HAPPENS MUST BE KNOWN” are trotted out without a hint of levity.

What is frustrating about this portrayal is that it poses a very legitimate question — what would happen if such a company were allowed to truly become so pervasive as to subsume society itself? — but goes about answering it in all the wrong ways.

Frank discussions about privacy and surveillance are well worth having, after all: We should all know, or at least consider, the implications of putting so much of our lives, our connections, our likes and habits, into the cloud. But Eggers feeds off a popular, albeit not entirely accurate belief, that technology itself is to blame for our societal ruin. Put another way, imagine being told for nearly 400 pages that cellphones are changing the way our children write and speak — a fact which has demonstrably been proven to be untrue.

This manifests itself most obviously in the way The Circle ’s central characters are portrayed. Mae, eager to please and oblivious to the company’s domineering goals, is merely a prop through which we learn about The Circle, it’s founders, its products and its plans. Later, she is quite literally turned into a lens, live streaming the company’s inner workings and minutiae for all to see. The exposition here is often dreary and lengthy, an exercise in meticulous world building that presents clunky, distorted aphorisms of how present day social networking and online interactions work.

Characters don’t merely Like things — they smile, and frown. They participate in online petitions and surveys, believing their choices hold tangible, worldly weight. They are wholly and utterly complicit in The Circle’s intrusion into their lives, and in a tired, predictable trope, it is up to a mysterious, shadowy figure to warn Mae of impending societal ruin.

There are brief mentions of resistance, a small percentage of people who seek to resist the mass surveillance and societal sublimation The Circle represents. But Eggers seems to have no desire to explore this opposition with anything more than passing derision, through an analog character named Mercer who makes deer antler chandeliers for a living.

It says nothing of the people who, in the present day, use technology against those who seek to digitally oppress — the online activists who champion anonymity, privacy and security, who are dismissed early on with an assertion that everyone in The Circle’s universe simply grew to prefer the use of real names.

Rather, technology’s ability to enable, as much as enslave, is just as worth exploring in a context such as this, but Eggers opts for the easier, more alarmist tale.

The Circle bludgeons its reader over the head — swiftly, repeatedly — with its message of societal doom and gloom. It is tedious, twice as long as it should be and reduces a topic rife for serious, smart and witty exploration into easily consumable popcorn fare. For those unfamiliar with the machinations of social media, or who grew up outside the Internet’s pervasive grasp, it may delight. But for the rest it will merely frustrate, a naive vision of pixelated ruin that could more accurately be summed up as “old man yells at Cloud.”

Matthew Braga writes about technology for the Financial Post .

Postmedia is committed to maintaining a lively but civil forum for discussion. Please keep comments relevant and respectful. Comments may take up to an hour to appear on the site. You will receive an email if there is a reply to your comment, an update to a thread you follow or if a user you follow comments. Visit our Community Guidelines for more information.

Subscriber only. Conrad Black: A better approach than 'reconciliation'

Np view: the pro-hamas puppet masters behind ‘pro-palestinian’ protests.

'Who are you to stop someone blowing crack smoke at a newborn?' Inside the thoughts of B.C.'s harm reduction program

Quebec man has two healthy fingers amputated to relieve 'body integrity dysphoria', vivian bercovici: liberals and ndp turned their backs on jews — in israel and canada.

What’s streaming April 2024: New on Netflix, Prime Video and more

A list of the top films and series that should be on your radar this month

Makeover: A spring refresh for a busy educator

Sandy Dhami, 45, works in education and was feeling like her hair was not exceeding its potential and needed extra attention.

Advertisement 2 Story continues below This advertisement has not loaded yet, but your article continues below.

Ciello review: A plush, supportive sofa

The easy-to-assemble sofa-in-a-box that’s comfortable and looks lovely

Sephora Spring Savings Event: Top products currently on sale

From refillable beauty products to what’s trending, here’s what to grab at the Sephora sale starting April 5

Beauty Buzz: Première by Kérastase hair care collection, Sahajan Sleep Well Bath Soak, and Roger and Gallet Wellbeing Fragrant Water Gingembre Rouge

Three buzzed-about beauty products we tried this week.

This website uses cookies to personalize your content (including ads), and allows us to analyze our traffic. Read more about cookies here . By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Terms of Service and Privacy Policy .

You've reached the 20 article limit.

You can manage saved articles in your account.

and save up to 100 articles!

Looks like you've reached your saved article limit!

You can manage your saved articles in your account and clicking the X located at the bottom right of the article.

We've detected unusual activity from your computer network

To continue, please click the box below to let us know you're not a robot.

Why did this happen?

Please make sure your browser supports JavaScript and cookies and that you are not blocking them from loading. For more information you can review our Terms of Service and Cookie Policy .

For inquiries related to this message please contact our support team and provide the reference ID below.

- Search for:

You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Book Review: The Circle by Dave Eggers

Dave Eggers’ novel about privacy and democracy in the Internet age, The Circle, asks, “If you aren’t being transparent with your personal information, what are you hiding?” Set in the near future, the story revolves around an omniscient tech company called The Circle that wants to digitally record your past, present and future, allegedly in the name of promoting human rights and democracy. Personal data is volunteered freely by the public, and so populist governments and online communities join the march towards total informational transparency. In The Circle , Eggers portends to expose the soft-totalitarian nightmare that waits at the logical end of such thinking – an extreme metaphor about transparency as a virtue, but maybe not extreme enough.

“All that happens must be known.”

The book follows young Mae Holland at work on the company’s sprawling Californian campus. Mae, accustomed to the drudgery and chicken-coop work of a call-centre, finds The Circle’s amenities and open-plan layout initially enticing – what’s more, the company’s medical benefits cover her sick father. The first part of the novel casually introduces this environment, an increasingly odd synergy between upbeat, blue-sky-thinking creatives and the institutionalisation of suspicion, conformity and mutualised invigilation.