Explanation of Grading System

Grades based upon the following system of marking are the only authorized grades to be used on the Official Class Roll and Grade Report Form.

Undergraduate Grade Points

- Letter grades of A, B, C, D, and F are used.

- Pluses and minuses may be assigned to grades of B and C.

- Minus may be assigned to an A, and plus may be assigned to a D.

- Temporary grades of IN and AB do not affect grade point average.

- Courses with a grade ( or notation ) of LP, PS, SP, BE, W or PL are ignored in establishing the quality point average.

Grade points are assigned as follows:

Grades of AB, FA, IN, PS, SP, and W are assigned as explained in the Undergraduate Grade Definitions area.

Undergraduate Grade Definitions

The following definitions will be used as a guide for the assignment of undergraduate grades.

A Mastery of course content at the highest level of attainment that can reasonably be expected of students at a given stage of development. The A grade states clearly that the students have shown such outstanding promise in the aspect of the discipline under study that he/she may be strongly encouraged to continue.

B Strong performance demonstrating a high level of attainment for a student at a given stage of development. The B grade states that the student has shown solid promise in the aspect of the discipline under study.

C A totally acceptable performance demonstrating an adequate level of attainment for a student at a given stage of development. The C grade states that, while not yet showing unusual promise, the student may continue to study in the discipline with reasonable hope of intellectual development.

D A marginal performance in the required exercises demonstrating a minimal passing level of attainment. A student has given no evidence of prospective growth in the discipline; an accumulation of D grades should be taken to mean that the student would be well advised not to continue in the academic field.

F For whatever reason, an unacceptable performance. The F grade indicates that the student’s performance in the required exercises has revealed almost no understanding of the course content. A grade of F should warrant an advisor’s questioning whether the student may suitably register for further study in the discipline before remedial work is undertaken.

AB Absent from final examination, but could have passed if exam taken. This is a temporary grade that converts to an F* after the last day of final exams for the next semester unless the student makes up the exam.

FA Failed and absent from exam. The FA grade is given when the undergraduate student did not attend the exam, and could not pass the course regardless of performance on the exam. This would be appropriate for a student that never attended the course or has excessive absences in the course, as well as missing the exam.

IN Work incomplete. This is a temporary grade that converts to F* after the last day of final exams into the next semester unless the student makes up the incomplete work.

PS Students who declare a course on the Pass/Fail option will receive the grade of PS (pass) when a letter grade of A through C is recorded on the official grade roster. An F under the Pass/Fail option counts as hours attempted and is treated in the same manner as F grades earned under any other grading basis. Instructors are not informed of which students have elected the Pass/Fail option and must assign the regular letter grade which will be converted to PS/F.

*Prior to Fall 2020 the PS grade was used when a student would have earned a letter grade of A through D and the LP grade was not used.

LP Low passing grade for a course using the Pass/Fail grading basis option, when an undergraduate student would have earned a letter grade of C-, D+, or D. Effective special grading accommodation for Fall 2020, Spring 2021, and later approved as a permanent grade.

NR This symbol is recorded as a notation for courses where grades are not recorded, such as when a faculty member has not submitted grades by the posted deadline for the term.

F* The Office of the University Registrar automatically converts the temporary grades of AB and IN to F* when the time limit for a grade change on these temporary grades has expired. The deadline for submitting a grade change for an AB or IN to an undergraduate student record is the last day of final exams in the following term.

Note: grade lapse is run for undergraduate students in Fall and Spring terms only. Temporary grades for summer terms are lapsed in the subsequent Fall term.

SP Satisfactory Progress ( Authorized only for the first portion of an Honors Program .)

W Withdrew passing. Entered when a student drops after the eight-week drop period.

NE No grade expected. This symbol is recorded as a notation for courses that are not graded, such as placeholders and some zero-credit courses.

Graduate Grades Definitions

All master’s and doctoral programs administered through The Graduate School operate under the same grading system. The graduate grading scale in use at UNC-Chapel Hill is unique in that it cannot be converted to the more traditional ABC grading scale. Graduate students do not carry a numerical GPA.

The following definitions will be used as a guide for the assignment of Graduate grades.

H – High Pass

P – Pass

L – Low Pass

F – Fail

IN – Work Incomplete A temporary grade that converts to an F* unless the grade is replaced with a permanent grade by the last day of classes for the same term one year later.

F* The Office of the University Registrar automatically converts the temporary grades of AB and IN to F* when the time limit for a grade change on these temporary grades has expired. The deadline for submitting a grade change for an AB or IN to a graduate student record is the last day of classes for the same term one year later.

AB – Absent from Final Examination A temporary grade that converts to an F* unless the grade is replaced with a permanent grade by the last day of classes for the same term one year later.

NOTE: Graduate students enrolled in courses numbered 099 and below ( prior to Fall 2006 ) and 399 and below ( starting with Fall 2006 ) should receive undergraduate grades.

Law School Grade Points

Effective August 2007 , letter grades of A, B, C, D, and F are used. Pluses and minuses may be assigned, but there is no grade of D-.

In rare instances, a grade of A+ is awarded in recognition of exceptionally high performance. Some designated courses are graded on a pass-fail basis. Students may not change a graded course to a pass/fail course.

From Fall 1993 – August 2007 , grades were assigned on a numerical scale ranging from 4.0 to 0.0. A grade of .7 will be considered the lowest passing grade. In rare instances, a grade of 4.3 may be awarded in recognition of exceptionally high performance.

Law School Grade Definitions

IN – Work Incomplete

AB – Absent from Final Examination

PS – Passing grade for course using Pass-Fail grading

F – Failed

Pharmacy Professional Program ( PHARMD ) Grade Definitions

Effective Fall 1997 Semester for Professional Pharmacy ( PHARMD ) students:

H – Clear Excellence

HP – Above Average

P – Entirely Satisfactory

LP – Below Average

L – Low Passing

Adopted in 1997, and amended in 2001 to eliminate +/- grading for all cohorts admitted to the Doctor of Pharmacy (professional degree) program in or after Fall 2002.

Classroom & Laboratory Courses Grade Definitions

The following definitions will be used as a guide for the assignment of Classroom & Laboratory Courses grades.

A – Clear Excellence

B – High Level of Achievement

C – Satisfactory Level of Achievement

Clinical Courses Grade Definitions

The following definitions will be used as a guide for the assignment of Clinical Courses grades.

All Courses Grade Definitions

The following definitions will be used as a guide for the assignment of All Courses grades.

F – Failed, Unacceptable Level of Achievement

A temporary grade; converts to an “F*” unless replaced with a permanent grade by the last day of classes for the same term one year later OR at the end of the term in which the course is next taught.

A temporary grade; converts to an F* unless replaced with a permanent grade after one year OR at the end of the term in which the course is next taught.

PS – Passing grade ( for elective courses using pass-fail grading under the University’s PS/D/D+/F option )

NOTE : Graduate Programs in the School of Pharmacy ( MS or PhD in Pharmaceutical Sciences ) use the standard University graduate grading scheme. No quality points are assigned to these grades.

Dentistry Professional Program ( DDS ) Grade Definitions

The following definitions will be used as a guide for the assignment of Dentistry Professional Program (DDS) grades.

A – Highest Level of Attainment

B – High Level of Attainment

C – Adequate Level of Attainment

D – Minimal Passing Level of Attainment

F – Failed, Unacceptable Performance

AB – Absent from Exam

PS – Pass

Medical School ( MD ) Grades

The School of Medicine records their own grades and houses the transcripts for students seeking the MD degree.

COVID-19 Grading Accommodations

Please refer to the following resources for information regarding the grading accommodations implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Grading Accommodation Spring/Summer 2020

Grading Accommodation Fall 2020/Spring 2021

Have a question about Grades?

Contact the records team at [email protected]

Imperial College London Imperial College London

Latest news.

Imperial Lates comes to a close with absorbing evening of AI

Imperial welcomes Irish Minister to celebrate research collaborations

Imperial-led consortium to nurture careers of research technicians

- Success Guide - undergraduate students

- Imperial students

- Success Guide

- Assessments & feedback

- Improving through feedback

Understanding grades

Getting a mark over 50% means that you are beginning to understand the difficult work of your degree. Getting over 60% is excellent because it means you have demonstrated a deep knowledge of your subject to the marker.

You may be used to getting marks of 90–100%, but this is very unlikely to happen at university. Remember that marks in the 50–70% range are perfectly normal. Your grades will improve as you get used to working at university level, and in the style required by your degree subject.

Degree classifications

UK degree classifications are as follows:

- First-Class Honours (First or 1st) (70% and above)

- Upper Second-Class Honours (2:1, 2.i) (60-70%)

- Lower Second-Class Honours (2:2, 2.ii) (50-60%)

- Third-Class Honours (Third or 3rd) (40-50%)

Visit the Regulations for further information on degree classifications.

In your first year at university, achieving a grade of 50% or more is a good thing. You can build on your work and improve as you work towards your final grade. Scores above 70% are classed as “First”, so you should be very excited to get a grade in that range.

It is rare for students to achieve grades higher than 90%, though this can happen. Remember as well that you will be surrounded by other highly motivated and capable students, so you may not automatically be top of the class anymore! Don’t worry – lots of your fellow students will be feeling the same, and there is always someone you can talk to about this. Having realistic expectations about your grades will help to reduce the possibility of feeling disappointed with yourself.

How to get a high mark

Before starting a piece of work, make sure you understand the assessment criteria . This may vary depending on your course and the specific piece of work; so ask your tutor if you are unsure.

In general, high marks will be given when you display that you have clearly understood the subject and included relevant detail. The best marks will go to students who show that they have read around the subject and brought their own analysis and criticism to the assignment.

Low marks will be given to a piece of work that suggests you don’t understand the subject or includes too much irrelevant detail. This applies to coursework and exams, so planning your work before you start is always a sensible option. Speak to your tutor if you are unsure about the requirements of a specific piece of work.

Don’t be afraid to ask

You may encounter different classifications, or courses that don’t use exactly the same boundaries. If you need help understanding the exact requirements of your course, contact your tutor for clarification.

When you’ve had your work returned to you, remember to look at the feedback to see where you could improve – this will give you the best chance of achieving a better grade in the future.

Center for Teaching

Grading student work.

Print Version

What Purposes Do Grades Serve?

Developing grading criteria, making grading more efficient, providing meaningful feedback to students.

- Maintaining Grading Consistency in Multi-Sectioned Courses

Minimizing Student Complaints about Grading

Barbara Walvoord and Virginia Anderson identify the multiple roles that grades serve:

- as an evaluation of student work;

- as a means of communicating to students, parents, graduate schools, professional schools, and future employers about a student’s performance in college and potential for further success;

- as a source of motivation to students for continued learning and improvement;

- as a means of organizing a lesson, a unit, or a semester in that grades mark transitions in a course and bring closure to it.

Additionally, grading provides students with feedback on their own learning , clarifying for them what they understand, what they don’t understand, and where they can improve. Grading also provides feedback to instructors on their students’ learning , information that can inform future teaching decisions.

Why is grading often a challenge? Because grades are used as evaluations of student work, it’s important that grades accurately reflect the quality of student work and that student work is graded fairly. Grading with accuracy and fairness can take a lot of time, which is often in short supply for college instructors. Students who aren’t satisfied with their grades can sometimes protest their grades in ways that cause headaches for instructors. Also, some instructors find that their students’ focus or even their own focus on assigning numbers to student work gets in the way of promoting actual learning.

Given all that grades do and represent, it’s no surprise that they are a source of anxiety for students and that grading is often a stressful process for instructors.

Incorporating the strategies below will not eliminate the stress of grading for instructors, but it will decrease that stress and make the process of grading seem less arbitrary — to instructors and students alike.

Source: Walvoord, B. & V. Anderson (1998). Effective Grading: A Tool for Learning and Assessment . San Francisco : Jossey-Bass.

- Consider the different kinds of work you’ll ask students to do for your course. This work might include: quizzes, examinations, lab reports, essays, class participation, and oral presentations.

- For the work that’s most significant to you and/or will carry the most weight, identify what’s most important to you. Is it clarity? Creativity? Rigor? Thoroughness? Precision? Demonstration of knowledge? Critical inquiry?

- Transform the characteristics you’ve identified into grading criteria for the work most significant to you, distinguishing excellent work (A-level) from very good (B-level), fair to good (C-level), poor (D-level), and unacceptable work.

Developing criteria may seem like a lot of work, but having clear criteria can

- save time in the grading process

- make that process more consistent and fair

- communicate your expectations to students

- help you to decide what and how to teach

- help students understand how their work is graded

Sample criteria are available via the following link.

- Analytic Rubrics from the CFT’s September 2010 Virtual Brownbag

- Create assignments that have clear goals and criteria for assessment. The better students understand what you’re asking them to do the more likely they’ll do it!

- letter grades with pluses and minuses (for papers, essays, essay exams, etc.)

- 100-point numerical scale (for exams, certain types of projects, etc.)

- check +, check, check- (for quizzes, homework, response papers, quick reports or presentations, etc.)

- pass-fail or credit-no-credit (for preparatory work)

- Limit your comments or notations to those your students can use for further learning or improvement.

- Spend more time on guiding students in the process of doing work than on grading it.

- For each significant assignment, establish a grading schedule and stick to it.

Light Grading – Bear in mind that not every piece of student work may need your full attention. Sometimes it’s sufficient to grade student work on a simplified scale (minus / check / check-plus or even zero points / one point) to motivate them to engage in the work you want them to do. In particular, if you have students do some small assignment before class, you might not need to give them much feedback on that assignment if you’re going to discuss it in class.

Multiple-Choice Questions – These are easy to grade but can be challenging to write. Look for common student misconceptions and misunderstandings you can use to construct answer choices for your multiple-choice questions, perhaps by looking for patterns in student responses to past open-ended questions. And while multiple-choice questions are great for assessing recall of factual information, they can also work well to assess conceptual understanding and applications.

Test Corrections – Giving students points back for test corrections motivates them to learn from their mistakes, which can be critical in a course in which the material on one test is important for understanding material later in the term. Moreover, test corrections can actually save time grading, since grading the test the first time requires less feedback to students and grading the corrections often goes quickly because the student responses are mostly correct.

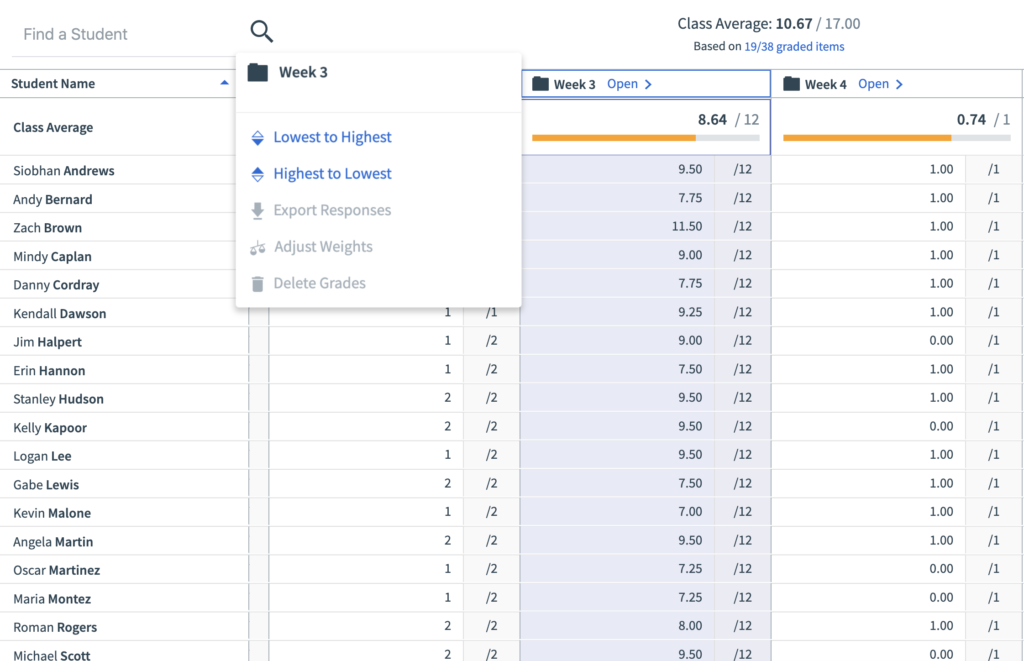

Spreadsheets – Many instructors use spreadsheets (e.g. Excel) to keep track of student grades. A spreadsheet program can automate most or all of the calculations you might need to perform to compute student grades. A grading spreadsheet can also reveal informative patterns in student grades. To learn a few tips and tricks for using Excel as a gradebook take a look at this sample Excel gradebook .

- Use your comments to teach rather than to justify your grade, focusing on what you’d most like students to address in future work.

- Link your comments and feedback to the goals for an assignment.

- Comment primarily on patterns — representative strengths and weaknesses.

- Avoid over-commenting or “picking apart” students’ work.

- In your final comments, ask questions that will guide further inquiry by students rather than provide answers for them.

Maintaining Grading Consistency in Multi-sectioned Courses (for course heads)

- Communicate your grading policies, standards, and criteria to teaching assistants, graders, and students in your course.

- Discuss your expectations about all facets of grading (criteria, timeliness, consistency, grade disputes, etc) with your teaching assistants and graders.

- Encourage teaching assistants and graders to share grading concerns and questions with you.

- have teaching assistants grade assignments for students not in their section or lab to curb favoritism (N.B. this strategy puts the emphasis on the evaluative, rather than the teaching, function of grading);

- have each section of an exam graded by only one teaching assistant or grader to ensure consistency across the board;

- have teaching assistants and graders grade student work at the same time in the same place so they can compare their grades on certain sections and arrive at consensus.

- Include your grading policies, procedures, and standards in your syllabus.

- Avoid modifying your policies, including those on late work, once you’ve communicated them to students.

- Distribute your grading criteria to students at the beginning of the term and remind them of the relevant criteria when assigning and returning work.

- Keep in-class discussion of grades to a minimum, focusing rather on course learning goals.

For a comprehensive look at grading, see the chapter “Grading Practices” from Barbara Gross Davis’s Tools for Teaching.

Teaching Guides

- Online Course Development Resources

- Principles & Frameworks

- Pedagogies & Strategies

- Reflecting & Assessing

- Challenges & Opportunities

- Populations & Contexts

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

Grade Calculator

Use this calculator to find out the grade of a course based on weighted averages. This calculator accepts both numerical as well as letter grades. It also can calculate the grade needed for the remaining assignments in order to get a desired grade for an ongoing course.

Final Grade Calculator

Use this calculator to find out the grade needed on the final exam in order to get a desired grade in a course. It accepts letter grades, percentage grades, and other numerical inputs.

Related GPA Calculator

The calculators above use the following letter grades and their typical corresponding numerical equivalents based on grade points.

Brief history of different grading systems

In 1785, students at Yale were ranked based on "optimi" being the highest rank, followed by second optimi, inferiore (lower), and pejores (worse). At William and Mary, students were ranked as either No. 1, or No. 2, where No. 1 represented students that were first in their class, while No. 2 represented those who were "orderly, correct and attentive." Meanwhile at Harvard, students were graded based on a numerical system from 1-200 (except for math and philosophy where 1-100 was used). Later, shortly after 1883, Harvard used a system of "Classes" where students were either Class I, II, III, IV, or V, with V representing a failing grade. All of these examples show the subjective, arbitrary, and inconsistent nature with which different institutions graded their students, demonstrating the need for a more standardized, albeit equally arbitrary grading system.

In 1887, Mount Holyoke College became the first college to use letter grades similar to those commonly used today. The college used a grading scale with the letters A, B, C, D, and E, where E represented a failing grade. This grading system however, was far stricter than those commonly used today, with a failing grade being defined as anything below 75%. The college later re-defined their grading system, adding the letter F for a failing grade (still below 75%). This system of using a letter grading scale became increasingly popular within colleges and high schools, eventually leading to the letter grading systems typically used today. However, there is still significant variation regarding what may constitute an A, or whether a system uses plusses or minuses (i.e. A+ or B-), among other differences.

An alternative to the letter grading system

Letter grades provide an easy means to generalize a student's performance. They can be more effective than qualitative evaluations in situations where "right" or "wrong" answers can be easily quantified, such as an algebra exam, but alone may not provide a student with enough feedback in regards to an assessment like a written paper (which is much more subjective).

Although a written analysis of each individual student's work may be a more effective form of feedback, there exists the argument that students and parents are unlikely to read the feedback, and that teachers do not have the time to write such an analysis. There is precedence for this type of evaluation system however, in Saint Ann's School in New York City, an arts-oriented private school that does not have a letter grading system. Instead, teachers write anecdotal reports for each student. This method of evaluation focuses on promoting learning and improvement, rather than the pursuit of a certain letter grade in a course. For better or for worse however, these types of programs constitute a minority in the United States, and though the experience may be better for the student, most institutions still use a fairly standard letter grading system that students will have to adjust to. The time investment that this type of evaluation method requires of teachers/professors is likely not viable on university campuses with hundreds of students per course. As such, although there are other high schools such as Sanborn High School that approach grading in a more qualitative way, it remains to be seen whether such grading methods can be scalable. Until then, more generalized forms of grading like the letter grading system are unlikely to be entirely replaced. However, many educators already try to create an environment that limits the role that grades play in motivating students. One could argue that a combination of these two systems would likely be the most realistic, and effective way to provide a more standardized evaluation of students, while promoting learning.

5 tips on writing better university assignments

Lecturer in Student Learning and Communication Development, University of Sydney

Disclosure statement

Alexandra Garcia does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Sydney provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

University life comes with its share of challenges. One of these is writing longer assignments that require higher information, communication and critical thinking skills than what you might have been used to in high school. Here are five tips to help you get ahead.

1. Use all available sources of information

Beyond instructions and deadlines, lecturers make available an increasing number of resources. But students often overlook these.

For example, to understand how your assignment will be graded, you can examine the rubric . This is a chart indicating what you need to do to obtain a high distinction, a credit or a pass, as well as the course objectives – also known as “learning outcomes”.

Other resources include lecture recordings, reading lists, sample assignments and discussion boards. All this information is usually put together in an online platform called a learning management system (LMS). Examples include Blackboard , Moodle , Canvas and iLearn . Research shows students who use their LMS more frequently tend to obtain higher final grades.

If after scrolling through your LMS you still have questions about your assignment, you can check your lecturer’s consultation hours.

2. Take referencing seriously

Plagiarism – using somebody else’s words or ideas without attribution – is a serious offence at university. It is a form of cheating.

In many cases, though, students are unaware they have cheated. They are simply not familiar with referencing styles – such as APA , Harvard , Vancouver , Chicago , etc – or lack the skills to put the information from their sources into their own words.

To avoid making this mistake, you may approach your university’s library, which is likely to offer face-to-face workshops or online resources on referencing. Academic support units may also help with paraphrasing.

You can also use referencing management software, such as EndNote or Mendeley . You can then store your sources, retrieve citations and create reference lists with only a few clicks. For undergraduate students, Zotero has been recommended as it seems to be more user-friendly.

Using this kind of software will certainly save you time searching for and formatting references. However, you still need to become familiar with the citation style in your discipline and revise the formatting accordingly.

3. Plan before you write

If you were to build a house, you wouldn’t start by laying bricks at random. You’d start with a blueprint. Likewise, writing an academic paper requires careful planning: you need to decide the number of sections, their organisation, and the information and sources you will include in each.

Research shows students who prepare detailed outlines produce higher-quality texts. Planning will not only help you get better grades, but will also reduce the time you spend staring blankly at the screen thinking about what to write next.

During the planning stage, using programs like OneNote from Microsoft Office or Outline for Mac can make the task easier as they allow you to organise information in tabs. These bits of information can be easily rearranged for later drafting. Navigating through the tabs is also easier than scrolling through a long Word file.

4. Choose the right words

Which of these sentences is more appropriate for an assignment?

a. “This paper talks about why the planet is getting hotter”, or b. “This paper examines the causes of climate change”.

The written language used at university is more formal and technical than the language you normally use in social media or while chatting with your friends. Academic words tend to be longer and their meaning is also more precise. “Climate change” implies more than just the planet “getting hotter”.

To find the right words, you can use SkELL , which shows you the words that appear more frequently, with your search entry categorised grammatically. For example, if you enter “paper”, it will tell you it is often the subject of verbs such as “present”, “describe”, “examine” and “discuss”.

Another option is the Writefull app, which does a similar job without having to use an online browser.

5. Edit and proofread

If you’re typing the last paragraph of the assignment ten minutes before the deadline, you will be missing a very important step in the writing process: editing and proofreading your text. A 2018 study found a group of university students did significantly better in a test after incorporating the process of planning, drafting and editing in their writing.

You probably already know to check the spelling of a word if it appears underlined in red. You may even use a grammar checker such as Grammarly . However, no software to date can detect every error and it is not uncommon to be given inaccurate suggestions.

So, in addition to your choice of proofreader, you need to improve and expand your grammar knowledge. Check with the academic support services at your university if they offer any relevant courses.

Written communication is a skill that requires effort and dedication. That’s why universities are investing in support services – face-to-face workshops, individual consultations, and online courses – to help students in this process. You can also take advantage of a wide range of web-based resources such as spell checkers, vocabulary tools and referencing software – many of them free.

Improving your written communication will help you succeed at university and beyond.

- College assignments

- University study

- Writing tips

- Essay writing

- Student assessment

Want to write?

Write an article and join a growing community of more than 180,400 academics and researchers from 4,914 institutions.

Register now

General University Grading System

Main navigation.

To jump to grading policies, please select a category below

- Revise Grades

Incomplete Grades

- Repeat Grades

The following summarizes the current General University Grading System adopted by the Faculty Senate on June 2, 1994. Courses completed prior to that time were subject to previous versions of this system .

The General University Grading System applies to all of Stanford University classes except those offered to students through the Graduate School of Business and the School of Law, and M.D. and M.S. in PAS students through the School of Medicine. Those schools grade courses using their local grading systems, even when your primary affiliation is with another Stanford school. For more details on other grading systems used at Stanford, visit Grades .

Students: Your transcripts and all your grades — excluding those of “I” (Incomplete), “GNR” (Grade Not Reported), “L” (Pass, grade to follow), and “N” (Continuation) — are fixed at the time of graduation. You have one year after your degree conferral to update grades of “GNR”, “L”, or “N” or they are locked in their existing status.

Understanding Grading Basis Types

- Grades Available: A+, A, A-, B+, B, B-, C+, C, C-, D+, D, D-, NP, I, L, N, N-

- Grades Available: CR, NC, I, N, N-

- Grades Available: S, NC, I, N, N-

Revision of End-Quarter Grades

When submitted via Axess or filed with the Registrar’s Office, end-quarter grades are final; they cannot be changed by the instructor for reason of a revision of judgment or on the basis of a second trial (e.g., a new examination or additional work undertaken or completed after the end of the quarter). Changes may be made at any time to correct an error in computation or in transcribing, or where some part of the student’s work was overlooked (i.e., the new grade is the one that would have been entered on the original report had there been no mistake in computing and had all the pertinent data been before the instructor).

In the event that a student disputes an end-quarter grade, the established grievance procedure should be followed (See the Student Academic Grievance Procedures policy.)

The “I” grade is restricted to cases in which you have satisfactorily completed a substantial part of the coursework. You do not receive credit until you complete the course with a passing grade. When the Registrar’s Office receives your final grade, the “I” notation is removed from your official transcript.

You must request an incomplete grade no later than the last class meeting. Instructors determine whether to grant the request and, if granted, the conditions under which you complete the remaining work, including setting a deadline of less than one year. Under no circumstances should you re-enroll in a class to complete an “I” grade. Enrolling in the class a second time invokes the Repeated Courses policy for courses that are not repeatable for credit.

An “I” grade must be changed to a grade or permanent notation within one year after you took the course (i.e., prior to the first day of the fifth quarter following the standard completion of the course, including Summer Quarter). If an incomplete grade is not cleared at the end of one year, it is automatically changed to an ‘NP’ (not passed) or ‘NC’ (no credit) as appropriate for the grading method of the course. Leaves of absence or other inactive statuses (e.g., discontinuation or conferral) do not alter the associated timeline.

Graduate students: If you are a graduate student with extenuating circumstances that may warrant an exception to academic policy, you must discuss the need for an extension with your advisor and the course instructor before the one-year deadline to complete the coursework expires. If the instructor agrees an extension is warranted, you may request an extension of one academic quarter to resolve an incomplete by submitting the Enrollment Change Petition - GR. Requests for extension submitted after the “I” grade has lapsed are not considered. You must have an active status (excluding a leave of absence) to petition to extend an incomplete.

If an “I” grade lapses to an NC or NP with an approved extension on file, the lapsed grade will remain until you have completed the required work and the instructor submits a final grade.

Note: Once an ‘I’ grade lapses, depending on the repeatability set up of the course, students may be eligible for their ‘NP’ or ‘NC’ to be replaced by the ‘RP’ notation. See Repeated Courses for additional information.

Leave of Absence

If you are on an approved leave of absence, you may complete coursework for which you received an “I” grade in a prior term unless doing so places an undue burden on an instructor, department, staff, or another university resource. You are still expected to comply with the maximum one-year time limit for resolving incompletes (i.e., a leave of absence does not alter the associated timeline for resolving incompletes).

Military Leaves of Absence

Students on an approved Military Leave of Absence are granted the following exceptions to the Incomplete Grading policies:

- If the student is called to service within weeks 1-8 of the quarter, the student may complete an LOA request form and receive a full tuition refund regardless of attendance.

- If the student is called to service within weeks 9-11, the student may take Incompletes in any or all courses; or the student may receive a grade for work completed in the course to date, based on the agreement with each instructor.

- In rare situations, the course requirements may not have been adequately met by weeks 9-11 in order to permit an Incomplete grade assignment. If the student was unable to complete the course requirements by the start of their military service and it is not possible for the student to complete the requirements at a later time, a late drop may be permitted. If the student had not been adequately engaging in the course prior to their leave, the instructor may be permitted to assign a grade of “NP” or “NC.”

- For a student completing work for previous incomplete courses, their timeline to complete the work will be extended by the duration of their required military service.

- Instructors must set a reasonable timeline for students to complete the work for an incomplete course and may not set a deadline prior to the student’s return from military service. Instructors must allow, at a minimum, a full quarter for the student to complete the work upon their return from military service. Students, in agreement with the professor, must complete the work within 1 year or less after their return from military service to align with the existing Incomplete grade policy.

- Should a student be called away to active duty after the last day of classes and unable to sit for final exams, the requirement to request an Incomplete grade in a course prior to finals week is not in effect.

Discontinued Students

You may complete and submit work toward an incomplete while in discontinued status unless doing so places an undue burden on the instructor, department, staff, or another university resource. You must fulfill the Incomplete within one year of the class finishing or risk lapsing to the appropriate failing notation (NP, NC). You must be in an active status to petition to extend an incomplete and are not permitted to make this request while in a discontinued or conferred status. Once an incomplete has lapsed to a failing grade, it no longer is eligible to be updated by the instructor nor can an extension be granted. Discontinuation does not alter the associated timeline for resolving incompletes.

Repeated Courses

Some Stanford courses may be repeated for credit; they are specifically noted in the Stanford Bulletin and ExploreCourses . Most courses may not be repeated for credit. Under the General University Grading System, when a course that may not be repeated for credit is retaken by a student, the following special rules apply:

- You may retake any course on your transcript, regardless of the grade earned, and have the original grade, for completed courses only, replaced by the notation 'RP' (repeated course). When retaking a course, the student must enroll in it for the same number of units originally taken. When the grade for the second enrollment in the course has been reported, the units and grade points for the second course count in the cumulative grade point average in place of the grade and units for the first enrollment in the course. Because the notation 'RP' can only replace grades for completed courses, the notation 'W' cannot be replaced by the notation 'RP' in any case.

- You may not retake the same course a third time unless you received an “NC” (no credit) or “NP” (not passed) when it was taken and completed the second time. When you complete a course the third time, grades and units for both the second and third completions count in your cumulative grade point average. The notation “W” is not counted toward the three-retake maximum. Any enrollment instance beyond the third retake, regardless of the grade earned, is not permitted unless by special approval from the Office of Academic Advising or the Registrar’s Office.

Note: Once an “I” notation lapses to an “NP” or is updated to a final grade by the instructor, it can be replaced by the “RP” notation. If you are working to complete an “I” notation and enroll in the class a second time, you could run the risk of having the incomplete excluded from the repeat process, eventually lapsing to an “NP” and subsequently frozen on the transcript upon degree conferral. Additional information on incomplete grades can be found in the Incomplete Grades section of this page.

You can submit questions on the Repeated Courses Policy via a Service Request .

Undergraduates who have questions related to requesting a second repeat of a course should meet with an Academic Advisor.

Temporary “N” Grades

Grading tgr 801 or 802 courses (“n” grades).

801 and 802 courses extend past a single quarter into successive quarters. You typically enroll in these courses when working on activities such as projects, theses, or dissertations.

When the instructor/advisor determines you are making satisfactory progress on the activity during the initial quarter(s) of these classes, you receive an “N” grade to indicate acceptable progress in a continuing course. You are given an “S” grade at the end of the final quarter when the instructor/advisor considers the activity satisfactorily completed.

When the instructor/advisor determines your progress is unsatisfactory in these courses, you receive an “N-” grade. Your first 'N-' grade constitutes a warning. The advisor, department chair, and student should discuss the deficiencies and agree on the steps necessary to correct them. If you receive a second “N-” it will normally result in the department denying you further registration until you submit a written plan for the completion of the degree requirements that is accepted by the department. Subsequent “N-” grades are grounds for dismissal from the program.

When you receive a final grade of “S” or “NP” for the final quarter of the project, thesis, or dissertation, that grade retroactively replaces the “N” grades for previous quarters. After you apply to graduate, the Registrar's Office runs an “N” grade report at the end of each quarter to update temporary “N” grades to their respective final grade. If the final grade is reported, but the previous “N” grades have not been replaced, please submit a SU Services & Support Request . Allow the Registrar’s Office several weeks after the end of each quarter to complete the process before reporting unconverted “N” grades.

Grading Non-TGR Courses (“N” Grades)

Departmental courses requiring enrollment for a number of successive quarters for ongoing research, projects, capstones, or theses that do not fall under the category of TGR status, are also eligible for a temporary “N” grade. To indicate that you are making satisfactory progress on the activity, your instructor assigns an “N” grade. Your final grade is recorded during the final quarter of enrollment in the series when you complete the research, project, capstone, or thesis and it is accepted by the department. If the ongoing project is not completed or accepted by the department, a grade of “NP” or “NC” is recorded as appropriate for the grading method of the course.

The Registrar’s Office does not run a manual “N” grade report for you if you have not applied to graduate. If you have not applied to graduate, or do not yet meet the requirements for degree conferral, your instructor must manually update the grade for each quarter, replacing the temporary “N” with your final grade. The units of credit awarded for the course do not appear on your transcript or on your student record until the “N” grade is updated (i.e., replaced by the instructor with your final grade).

The grading system in the US demystified (everything you want to know)

From the average course length and higher tuition fees to the importance of college football, there’s a lot that sets universities in America apart from those in other countries.

But for a student hoping to study abroad in the US , one of the more confusing things to understand is the US grading system.

You may have heard that American universities use letter grades when marking assignments, or you might already be familiar with the term ‘GPA,’ but how does it all fit together to give you a grade at the end of your studies?

Don’t worry, because we’ve got you covered. From how individual assignments are graded to how to calculate your GPA, here’s everything you need to know about the grading system in the USA.

Table of Contents

1. how are individual assessments graded in america, 2. what are quality points and how do they affect your grade, 3. what is a gpa and why is it important, 4. how is your gpa calculated, 5. what degree classifications are there in the us.

Every time you complete an individual assignment, your lecturer or instructor will give you a letter grade to tell you how well you performed.

The letter grading system ranges from A to F, and which letter you get depends on what percentage you score in the assignment, either by answering questions correctly or demonstrating that you’ve met the course requirements.

Grading system in the US (Grade conversion)

Anything between A and D is a pass, while F marks a failed assignment. You can also break each grade down even further if you wish, meaning you could class a B grade as a B+, B= or B-.

One thing to point out is that there has been no E grade in the American grading system since the 19th century, when parents and students would sometimes wrongly presume that the E stood for ‘excellent.’

Also read: How does the UK university grading system work?

Though individual assignments are mostly marked using the letter grade system, your grades aren’t the only thing used to determine your overall qualification.

This is where the US grading system gets a little more complicated. At most US universities, your grades will often correspond to something called a quality point, which is then calculated towards your GPA (more on this next).

Though every school, college and higher education institution uses a different scale, most use a 4.0 scale — referred to as a four point scale — that accompany your letter grades.

For example, if you receive an A grade, this will correspond to four points, while a B will get you three points, and so on until you reach F, which gives you no points.

Your overall grades then provide a Grade Point Average (GPA), which is the standard way of measuring academic achievement in the US.

The purpose of a GPA is to paint a picture of what kind of student you are, based on your performance throughout your degree.

If you passed all of your classes with high grades, you will most likely have a GPA that’s close to a 4.0. Alternatively, if you struggled with some classes but excelled in others, you may have a GPA of 2.5 to 3.0.

Getting a good GPA is really important if you want to apply for scholarships, enroll in a master’s degree or find a graduate job, as one of the first things admissions tutors or potential employers will do is look at your GPA.

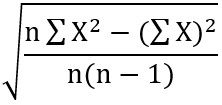

So now you know what a GPA is, the next step is to figure out how it’s calculated.

Each course you take has a set number of ‘units’ or ‘credits’ depending on the content and the set number of hours needed to complete weekly classes and homework.

Your average GPA is calculated by adding all the quality points achieved in each unit together and then dividing this by overall the number of course credits or units (credit hours) you attempted.

This number represents your GPA.

So for example, say you take one three-unit class and receive an A grade and then also get a C in a four-unit class.

For the first class, you need to times the three units by the four quality points for an A, giving you a total of 12-grade points.

For the second class, times the four units by two (the number of points you get for a C grade) to get eight points. Now, if you add these two numbers together you have accumulated 20 points over seven units.

Divide the total points by the total number of units to find your GPA, which in this case is 2.86, which falls just short of a 3.0 (B) average.

To Convert A Grade in India to the US 4.0 GPA Scale

At the end of the average undergraduate degree in the UK , students either graduate with First-Class Honours (70%+), an Upper Second-Class Honours or 2:1 (60-70%), a Lower Second-Class Honours or 2:2 (50-60%) or Third-Class Honours (40-50%).

If you achieve anything above 40%, you will pass your degree, while scoring higher than 70% will get you a first, the highest possible classification.

In America, the grading system in education is set up completely differently.

Instead of being awarded an honours classification, your GPA is your final grade, and is calculated using the method we explained above, by taking all your individual grades for each class into consideration.

The highest GPA you can graduate with is a 4.0, which is the equivalent to scoring 90-100%, or a first in the UK. A score of 80-89% overall provides a GPA of 3.0, while 70-79% is equivalent to a 2.0.

At the bottom end of the scale, the lowest GPA you are allowed to graduate with is 1.0, which is equivalent to scoring 60-69% in the UK. In America, anything less than 60% is counted as a fail.

Interested in studying abroad in the US? Learn more about all the top universities in America on our website and let us help you find your perfect course and university today!

You might also like: Difference between School, College and University in the UK

Guest Author

Talya is a part-time journalism master's student living in North Yorkshire.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions shared in this site solely belong to the individual authors and do not necessarily represent t ...Read More

Most affordable cities in USA for Indian students

Top 12 highest paying US majors 2024

Go Greek - Your guide to Greek life in the USA

University welcome week around the world: USA

Why are college sports so popular in the USA?

5 things you should know about applying to study in the USA

- Illinois Online

- Illinois Remote

- New Freshmen

- New International Students

- Info about COMPOSITION

- Info about MATH

- Info about SCIENCE

- LOTE for Non-Native Speakers

- Log-in Instructions

- ALEKS PPL Math Placement Exam

- Advanced Placement (AP) Credit

- What is IB?

- Advanced Level (A-Levels) Credit

- Departmental Proficiency Exams

- Departmental Proficiency Exams in LOTE ("Languages Other Than English")

- Testing in Less Commonly Studied Languages

- FAQ on placement testing

- FAQ on proficiency testing

- Legislation FAQ

- 2023 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2023 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2023 Cutoff Scores IMR-Biology

- 2023 Cutoff Scores MCB

- 2023 Cutoff Scores Physics

- 2023 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2023 Cutoff Scores ESL

- 2023 Cutoff Scores Chinese

- 2023 Cutoff Scores French

- 2023 Cutoff Scores German

- 2023 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2023 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2023 Advanced Placement Program

- 2023 International Baccalaureate Program

- 2023 Advanced Level Exams

- 2022 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2022 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2022 Cutoff Scores IMR-Biology

- 2022 Cutoff Scores MCB

- 2022 Cutoff Scores Physics

- 2022 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2022 Cutoff Scores ESL

- 2022 Cutoff Scores Chinese

- 2022 Cutoff Scores French

- 2022 Cutoff Scores German

- 2022 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2022 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2022 Advanced Placement Program

- 2022 International Baccalaureate Program

- 2022 Advanced Level Exams

- 2021 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2021 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2021 Cutoff Scores IMR-Biology

- 2021 Cutoff Scores MCB

- 2021 Cutoff Scores Physics

- 2021 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2021 Cutoff Scores ESL

- 2021 Cutoff Scores Chinese

- 2021 Cutoff Scores French

- 2021 Cutoff Scores German

- 2021 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2021 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2021 Advanced Placement Program

- 2021 International Baccalaureate Program

- 2021 Advanced Level Exams

- 2020 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2020 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2020 Cutoff Scores MCB

- 2020 Cutoff Scores Physics

- 2020 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2020 Cutoff Scores ESL

- 2020 Cutoff Scores Chinese

- 2020 Cutoff Scores French

- 2020 Cutoff Scores German

- 2020 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2020 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2020 Advanced Placement Program

- 2020 International Baccalaureate Program

- 2020 Advanced Level Exams

- 2019 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2019 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2019 Cutoff Scores MCB

- 2019 Cutoff Scores Physics

- 2019 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2019 Cutoff Scores Chinese

- 2019 Cutoff Scores ESL

- 2019 Cutoff Scores French

- 2019 Cutoff Scores German

- 2019 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2019 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2019 Advanced Placement Program

- 2019 International Baccalaureate Program

- 2019 Advanced Level Exams

- 2018 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2018 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2018 Cutoff Scores MCB

- 2018 Cutoff Scores Physics

- 2018 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2018 Cutoff Scores ESL

- 2018 Cutoff Scores French

- 2018 Cutoff Scores German

- 2018 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2018 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2018 Advanced Placement Program

- 2018 International Baccalaureate Program

- 2018 Advanced Level Exams

- 2017 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2017 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2017 Cutoff Scores MCB

- 2017 Cutoff Scores Physics

- 2017 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2017 Cutoff Scores ESL

- 2017 Cutoff Scores French

- 2017 Cutoff Scores German

- 2017 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2017 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2017 Advanced Placement Program

- 2017 International Baccalaureate Program

- 2017 Advanced Level Exams

- 2016 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2016 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2016 Cutoff Scores Physics

- 2016 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2016 Cutoff Scores ESL

- 2016 Cutoff Scores French

- 2016 Cutoff Scores German

- 2016 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2016 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2016 Advanced Placement Program

- 2016 International Baccalaureate Program

- 2016 Advanced Level Exams

- 2015 Fall Cutoff Scores Math

- 2016 Spring Cutoff Scores Math

- 2015 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2015 Cutoff Scores Physics

- 2015 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2015 Cutoff Scores ESL

- 2015 Cutoff Scores French

- 2015 Cutoff Scores German

- 2015 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2015 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2015 Advanced Placement Program

- 2015 International Baccalaureate (IB) Program

- 2015 Advanced Level Exams

- 2014 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2014 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2014 Cutoff Scores Physics

- 2014 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2014 Cutoff Scores ESL

- 2014 Cutoff Scores French

- 2014 Cutoff Scores German

- 2014 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2014 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2014 Advanced Placement (AP) Program

- 2014 International Baccalaureate (IB) Program

- 2014 Advanced Level Examinations (A Levels)

- 2013 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2013 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2013 Cutoff Scores Physics

- 2013 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2013 Cutoff Scores ESL

- 2013 Cutoff Scores French

- 2013 Cutoff Scores German

- 2013 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2013 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2013 Advanced Placement (AP) Program

- 2013 International Baccalaureate (IB) Program

- 2013 Advanced Level Exams (A Levels)

- 2012 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2012 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2012 Cutoff Scores Physics

- 2012 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2012 Cutoff Scores ESL

- 2012 Cutoff Scores French

- 2012 Cutoff Scores German

- 2012 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2012 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2012 Advanced Placement (AP) Program

- 2012 International Baccalaureate (IB) Program

- 2012 Advanced Level Exams (A Levels)

- 2011 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2011 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2011 Cutoff Scores Physics

- 2011 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2011 Cutoff Scores French

- 2011 Cutoff Scores German

- 2011 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2011 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2011 Advanced Placement (AP) Program

- 2011 International Baccalaureate (IB) Program

- 2010 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2010 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2010 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2010 Cutoff Scores French

- 2010 Cutoff Scores German

- 2010 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2010 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2010 Advanced Placement (AP) Program

- 2010 International Baccalaureate (IB) Program

- 2009 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2009 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2009 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2009 Cutoff Scores French

- 2009 Cutoff Scores German

- 2009 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2009 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2009 Advanced Placement (AP) Program

- 2009 International Baccalaureate (IB) Program

- 2008 Cutoff Scores Math

- 2008 Cutoff Scores Chemistry

- 2008 Cutoff Scores Rhetoric

- 2008 Cutoff Scores French

- 2008 Cutoff Scores German

- 2008 Cutoff Scores Latin

- 2008 Cutoff Scores Spanish

- 2008 Advanced Placement (AP) Program

- 2008 International Baccalaureate (IB) Program

- Log in & Interpret Student Profiles

- Mobius View

- Classroom Test Analysis: The Total Report

- Item Analysis

- Error Report

- Omitted or Multiple Correct Answers

- QUEST Analysis

Assigning Course Grades

- Improving Your Test Questions

- ICES Online

- Myths & Misperceptions

- Longitudinal Profiles

- List of Teachers Ranked as Excellent by Their Students

- Focus Groups

- IEF Question Bank

For questions or information:

- Introduction

- Grading Comparisons

- Basic Guidelines

- Methods of Assigning Course Grades

- Grading vs. Evaluation

- Grading in Multi-Sectioned Courses

- Evaluating Grading Policies

- Assistance Offered by Center for Innovation in Teaching and Learning

- References for Further Reading

I. INTRODUCTION

The end-of-course grades assigned by instructors are intended to convey the level of achievement of each student in the class. These grades are used by students, other faculty, university administrators, and prospective employers to make a multitude of different decisions. Unless instructors use generally-accepted policies and practices in assigning grades, these grades are apt to convey misinformation and lead the decision-maker astray. When grading policies and practices are carefully formulated and reviewed periodically, they can serve well the many purposes for which they are used.

What might a faculty member consider to establish sound grading policies and practices? The issues which contribute to making grading a controversial topic are primarily philosophical in nature. There are no research studies that can answer questions like: What should an "A" grade mean? What percent of the students in my class should receive a "C?" Should spelling and grammar be judged in assigning a grade to a paper? What should a course grade represent? These "should" questions require value judgments rather than an interpretation of research data; the answer to each will vary from instructor to instructor. But all instructors must ask similar questions and find acceptable answers to them in establishing their own grading policies. It is not sufficient to have some method of assigning grades--the method used must be defensible by the user in terms of his or her beliefs about the goals of an American college education and tempered by the realities of the setting in which grades are given. An instructor's view of the role of a university education consciously or unwittingly affects grading plans. The instructor who believes that the end product of a university education should be a "prestigious" group which has survived four or more years of culling and sorting has different grading policies from the instructor who believes that most college-aged youths should be able to earn a college degree in four or more years.

An instructor's beliefs are influenced by many factors. As any of these factors change there may be a corresponding change in belief. The type of instructional strategy used in teaching dictates, to some extent, the type of grading procedures to use. For example, a mastery learning approach 1 to teaching is incongruent with a grading approach which is based on competition for an arbitrarily set number of "A" or "B" grades. Grading policies of the department, college, or campus may limit the procedures which can be used and force a basic grading plan on each instructor in that administrative unit. The recent response to grade inflation has caused some faculty, individually and collectively, to alter their philosophies and procedures. Pressure from colleagues to give lower or higher grades often causes some faculty members to operate in conflict with their own views. Student grade expectations and the need for positive student evaluations of instruction probably both contribute to the shaping or altering of the grading philosophies of some faculty. The dissonance created by institutional restraints probably contributes to the wide-spread feeling that end-of-course grading is one of the least pleasant tasks facing a college instructor.

With careful thought and periodic review, most instructors can develop satisfactory, defensible grading policies and procedures. To this end, several of the key issues associated with grading are identified in the sections which follow. In each case, alternative viewpoints are described and advantages and disadvantages noted. Regulations pertaining to grading at the University of Illinois are presented in Article 3, Part 1 of the Student Code .

1 Airasian, P. W., Block, J. H., Bloom, B. S., & Carroll, J. B., (1971) Mastery learning: Theory and practice (J. Block, Ed.). Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

II. GRADING COMPARISONS

Some kind of comparison is being made when grades are assigned. For example, an instructor may compare a student's performance to that of his or her classmates, to standards of excellence (i.e., pre-determined objectives, contracts, professional standards) or to combinations of each. Four common comparisons used to determine college and university grades and the major advantages and disadvantages of each are discussed in the following section.

Comparisons With Other Students

By comparing a student's overall course performance with that of some relevant group of students, the instructor assigns a grade to show the student's level of achievement or standing within that group. An "A" might not represent excellence in attainment of knowledge and skill if the reference group as a whole is somewhat inept. All students enrolled in a course during a given semester or all students enrolled in a course since its inception are examples of possible comparison groups. The nature of the reference group used is the key to interpreting grades based on comparisons with other students.

Some Advantages of Grading Based on Comparison With Other Students

- Individuals whose academic performance is outstanding in comparison to their peers are rewarded.

- The system is a common one that many faculty members are familiar with. Given additional information about the students, instructor, or college department, grades from the system can be interpreted easily.

Some Disadvantages of Grading Based on Comparison With Other Students

- No matter how outstanding the reference group of students is, some will receive low grades; no matter how low the overall achievement in the reference group, some students will receive high grades. Grades are difficult to interpret without additional information about the overall quality of the group.

- Grading standards in a course tend to fluctuate with the quality of each class of students. Standards are raised by the performance of a bright class and lowered by the performance of a less able group of students. Often a student's grade depends on who was in the class.

- There is usually a need to develop course "norms" which account for more than a single class performance. Students of an instructor who is new to the course may be at a particular disadvantage since the reference group will necessarily be small and very possibly atypical compared with future classes.

Comparisons with Established Standards

Grades may be obtained by comparing a student's performance with specified absolute standards rather than with such relative standards as the work of other students. In this grading method, the instructor is interested in indicating how much of a set of tasks or ideas a student knows, rather than how many other students have mastered more or less of that domain. A "C" in an introductory statistics class might indicate that the student has minimal knowledge of descriptive and inferential statistics. A much higher achievement level would be required for an "A." Note that students' grades depend on their level of content mastery; thus the levels of performance of their classmates has no bearing on the final course grade. There are no quotas in each grade category. It is possible in a given class that all students could receive an "A" or a "B."

Some Advantages of Grading Based on Comparison to Absolute Standards

- Course goals and standards must necessarily be defined clearly and communicated to the students.

- Most students, if they work hard enough and receive adequate instruction, can obtain high grades. The focus is on achieving course goals, not on competing for a grade.

- Final course grades reflect achievement of course goals. The grade indicates "what" a student knows rather than how well he or she has performed relative to the reference group.

- Students do not jeopardize their own grade if they help another student with course work.

Some Disadvantages of Grading Based on Comparison to Absolute Standards

- It is difficult and time consuming to determine what course standards should be for each possible course grade issued.

- The instructor has to decide on reasonable expectations of students and necessary prerequisite knowledge for subsequent courses. Inexperienced instructors may be at a disadvantage in making these assessments.

- A complete interpretation of the meaning of a course grade cannot be made unless the major course goals are also available.

Comparisons Based on Learning Relative to Improvement and Ability

The following two comparisons—with improvement and ability—are sometimes used by instructors in grading students. There are such serious philosophical and methodological problems related to these comparisons that their use is highly questionable for most educational situations.

Relative to Improvement...

Students' grades may be based on the knowledge and skill they possess at the end of a course compared to their level of achievement at the beginning of the course. Large gains are assigned high grades and small gains are represented by low grades. Students who enter a course with some pre-course knowledge are obviously penalized; they have less to gain from a course than does a relatively naive student. The post test–pretest gain score is more error-laden, from a measurement perspective, than either of the scores from which it is derived. Though growth is certainly important when assessing the impact of instruction, it is less useful as a basis for determining course grades than end-of-course competence. The value of grades which reflect growth in a college-level course is probably minimal.

Relative to Ability...

Course grades might represent the amount students learned in a course relative to how much they could be expected to learn as predicted from their measured academic ability. Students with high ability scores (e.g., scores on the SAT or ACT) would be expected to achieve higher final examination scores than those with lower ability scores. When grades are based on comparisons with predicted ability, an "overachiever" and an "underachiever" may receive the same grade in a particular course, yet their levels of competence with respect to the course content may be vastly different. The first student may not be prepared to take a more advanced course, but the second student may be. A course grade may, in part, reflect the amount of effort the instructor believes a student has put into a course. The high ability students who can satisfy course requirements with minimal effort are penalized for their apparent "lack" of effort. Since the letter grade alone does not communicate such information, the value of ability-based grading does not warrant its use.

A single course grade should represent only one of the several grading comparisons noted above. To expect a course grade to reflect more than one of these comparisons is too much of a communication burden. Instructors who wish to communicate more than relative group standing, or subject matter competence or level of effort, must find additional ways to provide such information to each student. Suggestions for doing so are noted near the end of Section V.

III. BASIC GRADING GUIDELINES

1. grades should conform to the practice in the department and the institution in which the grading occurs. .

Grading policies of the department, college, or campus may limit the grading procedures which can be used and force a basic grading philosophy on each instructor in that administrative unit. Departments often have written statements which specify a method of assigning grades and meanings of grades. If such grading policies are not explicitly stated or written for faculty use, the percentages of A's, B's, C's, D's, and F's given by departments and colleges in their 100-level, 200- level, 300-level and graduate courses may be indicative of implicitly stated grading policies. Grade distribution information is available from all departmental offices or from Measurement and Evaluation (M&E) of the Center for Innovation in Teaching and Learning (CITL).

The University regulations encourage a uniform grading policy so that a grade of A, B, C, D, or F will have the same meaning independent of the college or department awarding the grade. In practice grade distributions vary by department, by college, and over time within each of these units. The grading standards of a department or college are usually known by other campus units. For example, a "B" in a required course given by Department X might indicate that the student probably is not a qualified candidate for graduate school in that or a related field. Or, a "B" in a required course given by Department Y might indicate that the student's knowledge is probably adequate for the next course. Grades in certain "key" courses may also be interpreted as a sign of a student's ability to continue work in the field. The faculty member who is uninformed about the grading grapevine may unwittingly make misleading statements about a student and also misinterpret information received. If an instructor's grading pattern differs markedly from others in the department or college and the grading is not being done in special classes (e.g., honors, remedial), the instructor should reexamine his or her grading practices to see that they are rational and defensible. Sometimes an individual faculty member's grading policy will differ markedly from that of the department and/or college and yet be defensible. For example, the department and instructor may be using different grading standards, course structure may seem to require a grading plan which differs from departmental guidelines, or the instructor and department may hold different ideas about the function of grading. Usually in such cases, a satisfactory grading plan can be worked out. Faculty new to the University can consult with the department head for advice about grade assignment procedures in particular courses. Measurement and Evaluation will consult with faculty on grading problems and procedures.

2. Grading Components Should Yield Accurate Information.

Carefully written tests and/or graded assignments (homework papers, projects) are keys to accurate grading. Because it is not customary at the university level to accumulate many grades per student, each grade carries great weight and should be as accurate as possible. Poorly planned tests and assignments increase the likelihood that grades will be based primarily on factors of chance. Some faculty members argue that over the course of a college education, students will receive an equal number of higher-grades-than-merited and lower-grades-than-merited. Consequently, final GPA's will be relatively correct. However, in view of the many ways course grades are used, each course grade is often significant in itself to the student and others. No evaluation efforts can be expected to be perfectly accurate, but there is merit in striving to assign course grades that most accurately reflect the level of competence of each student.

3. Grading Plans Should Be Communicated to the Class at the Beginning of Each Semester.

By stating the grading procedures at the beginning of a course, the instructor is essentially making a "contract" with the class about how each student is going to be evaluated. The contract should provide the students with a clear understanding of the instructor's expectations so that the students can structure their work efforts. Students should be informed about: which course activities will be considered in their final grade; the importance or weight of exams, quizzes, homework sets, papers and projects; and which topics are more important than others. Students also need to know what method will be used to assign their course grade and what kind of comparison the course grade will represent. By informing students early in the semester about course priorities, the instructor encourages students to study what he or she deems valuable. All of this information can be communicated effectively as a part of the course outline or syllabus.

4. Grading Plans Stated at the Beginning of the Course Should Not Be Changed Without Thoughtful Consideration and a Complete Explanation to the Students.

Two common complaints found on students' post-course evaluations are that grading procedures stated at the beginning of the course were either inconsistently followed or were changed without explanation or even advanced notice. One could look at the situation of altering or inconsistently following the grading plan as being analogous to playing a game wherein the rules arbitrarily change, sometimes without the players' knowledge. The ability to participate becomes an extremely difficult and frustrating experience. Students are placed in the unreasonable position of never knowing for sure what the instructor considers important. When the rules need to be changed all of the players must be informed (and hopefully be in agreement).

5. The Number of Components or Elements Used to Assign Course Grades Should Be Large Enough to Enhance High Accuracy in Grading.

From a decision-making point of view, the more pieces of information available to the decision-maker, the more confidence one can have that the decision will be accurate and appropriate. This same principle applies to the process of assigning grades. If only a final exam score is used to assign a course grade, the adequacy of the grade will depend on how well the test covered all the relevant aspects of course content and how typically the student performed on one specific day during a 2-3 hour period. Though the minimum number of tests, quizzes, papers, projects, and/or presentations needed must be course- specific, each instructor must attempt to secure as much relevant data as are reasonably possible to ensure that the course grade will accurately reflect each student's achievement level.

IV. SOME METHODS OF ASSIGNING COURSE GRADES

Various grading practices are used by college and university faculty. Following is an examination of the more widely used methods and discussion of the advantages, disadvantages and fallacies associated with each.

Weighting Grading Components and Combining Them to Obtain a Final Grade