- How it works

A Step-By-Step Guide to Write the Perfect Dissertation

“A dissertation or a thesis is a long piece of academic writing based on comprehensive research.”

The significance of dissertation writing in the world of academia is unparalleled. A good dissertation paper needs months of research and marks the end of your respected academic journey. It is considered the most effective form of writing in academia and perhaps the longest piece of academic writing you will ever have to complete.

This thorough step-by-step guide on how to write a dissertation will serve as a tool to help you with the task at hand, whether you are an undergraduate student or a Masters or PhD student working on your dissertation project. This guide provides detailed information about how to write the different chapters of a dissertation, such as a problem statement , conceptual framework , introduction , literature review, methodology , discussion , findings , conclusion , title page , acknowledgements , etc.

What is a Dissertation? – Definition

Before we list the stages of writing a dissertation, we should look at what a dissertation is.

The Cambridge dictionary states that a dissertation is a long piece of writing on a particular subject, especially one that is done to receive a degree at college or university, but that is just the tip of the iceberg because a dissertation project has a lot more meaning and context.

To understand a dissertation’s definition, one must have the capability to understand what an essay is. A dissertation is like an extended essay that includes research and information at a much deeper level. Despite the few similarities, there are many differences between an essay and a dissertation.

Another term that people confuse with a dissertation is a thesis. Let's look at the differences between the two terms.

What is the Difference Between a Dissertation and a Thesis?

Dissertation and thesis are used interchangeably worldwide (and may vary between universities and regions), but the key difference is when they are completed. The thesis is a project that marks the end of a degree program, whereas the dissertation project can occur during the degree. Hanno Krieger (Researchgate, 2014) explained the difference between a dissertation and a thesis as follows:

“Thesis is the written form of research work to claim an academic degree, like PhD thesis, postgraduate thesis, and undergraduate thesis. On the other hand, a dissertation is only another expression of the written research work, similar to an essay. So the thesis is the more general expression.

In the end, it does not matter whether it is a bachelor's, master or PhD dissertation one is working on because the structure and the steps of conducting research are pretty much identical. However, doctoral-level dissertation papers are much more complicated and detailed.

Problems Students Face When Writing a Dissertation

You can expect to encounter some troubles if you don’t yet know the steps to write a dissertation. Even the smartest students are overwhelmed by the complexity of writing a dissertation.

A dissertation project is different from any essay paper you have ever committed to because of the details of planning, research and writing it involves. One can expect rewarding results at the end of the process if the correct guidelines are followed. Still, as indicated previously, there will be multiple challenges to deal with before reaching that milestone.

The three most significant problems students face when working on a dissertation project are the following.

Poor Project Planning

Delaying to start working on the dissertation project is the most common problem. Students think they have sufficient time to complete the paper and are finding ways to write a dissertation in a week, delaying the start to the point where they start stressing out about the looming deadline. When the planning is poor, students are always looking for ways to write their dissertations in the last few days. Although it is possible, it does have effects on the quality of the paper.

Inadequate Research Skills

The writing process becomes a huge problem if one has the required academic research experience. Professional dissertation writing goes well beyond collecting a few relevant reference resources.

You need to do both primary and secondary research for your paper. Depending on the dissertation’s topic and the academic qualification you are a candidate for, you may be required to base your dissertation paper on primary research.

In addition to secondary data, you will also need to collect data from the specified participants and test the hypothesis . The practice of primary collection is time-consuming since all the data must be analysed in detail before results can be withdrawn.

Failure to Meet the Strict Academic Writing Standards

Research is a crucial business everywhere. Failure to follow the language, style, structure, and formatting guidelines provided by your department or institution when writing the dissertation paper can worsen matters. It is recommended to read the dissertation handbook before starting the write-up thoroughly.

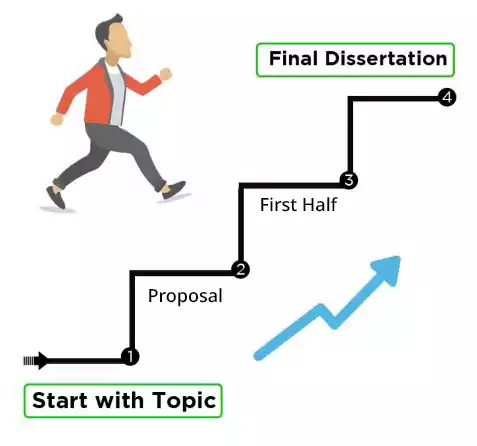

Steps of Writing a Dissertation

For those stressing out about developing an extensive paper capable of filling a gap in research whilst adding value to the existing academic literature—conducting exhaustive research and analysis—and professionally using the knowledge gained throughout their degree program, there is still good news in all the chaos.

We have put together a guide that will show you how to start your dissertation and complete it carefully from one stage to the next.

Find an Interesting and Manageable Dissertation Topic

A clearly defined topic is a prerequisite for any successful independent research project. An engaging yet manageable research topic can produce an original piece of research that results in a higher academic score.

Unlike essays or assignments, when working on their thesis or dissertation project, students get to choose their topic of research.

You should follow the tips to choose the correct topic for your research to avoid problems later. Your chosen dissertation topic should be narrow enough, allowing you to collect the required secondary and primary data relatively quickly.

Understandably, many people take a lot of time to search for the topic, and a significant amount of research time is spent on it. You should talk to your supervisor or check out the intriguing database of ResearchProspect’s free topics for your dissertation.

Alternatively, consider reading newspapers, academic journals, articles, course materials, and other media to identify relevant issues to your study area and find some inspiration to get going.

You should work closely with your supervisor to agree to a narrowed but clear research plan.Here is what Michelle Schneider, learning adviser at the University of Leeds, had to say about picking the research topics,

“Picking something you’re genuinely interested in will keep you motivated. Consider why it’s important to tackle your chosen topic," Michelle added.

Develop a First-Class Dissertation Proposal.

Once the research topic has been selected, you can develop a solid dissertation proposal . The research proposal allows you to convince your supervisor or the committee members of the significance of your dissertation.

Through the proposal, you will be expected to prove that your work will significantly value the academic and scientific communities by addressing complex and provocative research questions .

Dissertation proposals are much shorter but follow a similar structure to an extensive dissertation paper. If the proposal is optional in your university, you should still create one outline of the critical points that the actual dissertation paper will cover. To get a better understanding of dissertation proposals, you can also check the publicly available samples of dissertation proposals .

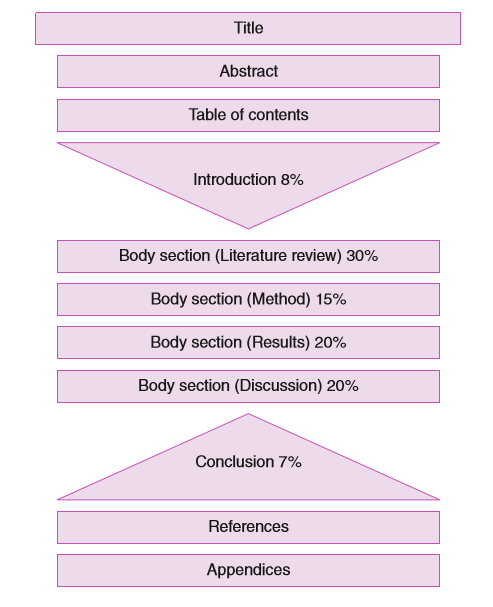

Typical contents of the dissertation paper are as follows;

- A brief rationale for the problem your dissertation paper will investigate.

- The hypothesis you will be testing.

- Research objectives you wish to address.

- How will you contribute to the knowledge of the scientific and academic community?

- How will you find answers to the critical research question(s)?

- What research approach will you adopt?

- What kind of population of interest would you like to generalise your result(s) to (especially in the case of quantitative research)?

- What sampling technique(s) would you employ, and why would you not use other methods?

- What ethical considerations have you taken to gather data?

- Who are the stakeholders in your research are/might be?

- What are the future implications and limitations you see in your research?

Let’s review the structure of the dissertation. Keep the format of your proposal simple. Keeping it simple keeps your readers will remain engaged. The following are the fundamental focal points that must be included:

Title of your dissertation: Dissertation titles should be 12 words in length. The focus of your research should be identifiable from your research topic.

Research aim: The overall purpose of your study should be clearly stated in terms of the broad statements of the desired outcomes in the Research aim. Try and paint the picture of your research, emphasising what you wish to achieve as a researcher.

Research objectives: The key research questions you wish to address as part of the project should be listed. Narrow down the focus of your research and aim for at most four objectives. Your research objectives should be linked with the aim of the study or a hypothesis.

Literature review: Consult with your supervisor to check if you are required to use any specific academic sources as part of the literature review process. If that is not the case, find out the most relevant theories, journals, books, schools of thought, and publications that will be used to construct arguments in your literature research.Remember that the literature review is all about giving credit to other authors’ works on a similar topic

Research methods and techniques: Depending on your dissertation topic, you might be required to conduct empirical research to satisfy the study’s objectives. Empirical research uses primary data such as questionnaires, interview data, and surveys to collect.

On the other hand, if your dissertation is based on secondary (non-empirical) data, you can stick to the existing literature in your area of study. Clearly state the merits of your chosen research methods under the methodology section.

Expected results: As you explore the research topic and analyse the data in the previously published papers, you will begin to build your expectations around the study’s potential outcomes. List those expectations here.

Project timeline: Let the readers know exactly how you plan to complete all the dissertation project parts within the timeframe allowed. You should learn more about Microsoft Project and Gantt Charts to create easy-to-follow and high-level project timelines and schedules.

References: The academic sources used to gather information for the proposed paper will be listed under this section using the appropriate referencing style. Ask your supervisor which referencing style you are supposed to follow.

The proposals we write have:

- Precision and Clarity

- Zero Plagiarism

- High-level Encryption

- Authentic Sources

Investigation, Research and Data Collection

This is the most critical stage of the dissertation writing process. One should use up-to-date and relevant academic sources that are likely to jeopardise hard work.

Finding relevant and highly authentic reference resources is the key to succeeding in the dissertation project, so it is advised to take your time with this process. Here are some of the things that should be considered when conducting research.

dissertation project, so it is advised to take your time with this process. Here are some of the things that should be considered when conducting research.

You cannot read everything related to your topic. Although the practice of reading as much material as possible during this stage is rewarding, it is also imperative to understand that it is impossible to read everything that concerns your research.

This is true, especially for undergraduate and master’s level dissertations that must be delivered within a specific timeframe. So, it is important to know when to stop! Once the previous research and the associated limitations are well understood, it is time to move on.

However, review at least the salient research and work done in your area. By salient, we mean research done by pioneers of your field. For instance, if your topic relates to linguistics and you haven’t familiarised yourself with relevant research conducted by, say, Chomsky (the father of linguistics), your readers may find your lack of knowledge disconcerting.

So, to come off as genuinely knowledgeable in your own field, at least don’t forget to read essential works in the field/topic!

Use an Authentic Research database to Find References.

Most students start the reference material-finding process with desk-based research. However, this research method has its own limitation because it is a well-known fact that the internet is full of bogus information and fake information spreads fasters on the internet than truth does .

So, it is important to pick your reference material from reliable resources such as Google Scholar , Researchgate, Ibibio and Bartleby . Wikipedia is not considered a reliable academic source in the academic world, so it is recommended to refrain from citing Wikipedia content.Never underrate the importance of the actual library. The supporting staff at a university library can be of great help when it comes to finding exciting and reliable publications.

Record as you learn

All information and impressions should be recorded as notes using online tools such as Evernote to make sure everything is clear. You want to retain an important piece of information you had planned to present as an argument in the dissertation paper.

Write a Flawless Dissertation

Start to write a fantastic dissertation immediately once your proposal has been accepted and all the necessary desk-based research has been conducted. Now we will look at the different chapters of a dissertation in detail. You can also check out the samples of dissertation chapters to fully understand the format and structures of the various chapters.

Dissertation Introduction Chapter

The introduction chapter of the dissertation paper provides the background, problem statement and research questions. Here, you will inform the readers why it was important for this research to be conducted and which key research question(s) you expect to answer at the end of the study.

Definitions of all the terms and phrases in the project are provided in this first chapter of the dissertation paper. The research aim and objectives remain unchanged from the proposal paper and are expected to be listed under this section.

Dissertation Literature Review Chapter

This chapter allows you to demonstrate to your readers that you have done sufficient research on the chosen topic and understand previous similar studies’ findings. Any research limitations that your research incorporates are expected to be discussed in this section.

And make sure to summarise the viewpoints and findings of other researchers in the dissertation literature review chapter. Show the readers that there is a research gap in the existing work and your job is relevant to it to justify your research value.

Dissertation Methodology

The methodology chapter of the dissertation provides insight into the methods employed to collect data from various resources and flows naturally from the literature review chapter.Simply put, you will be expected to explain what you did and how you did it, helping the readers understand that your research is valid and reliable. When writing the methodology chapter for the dissertation, make sure to emphasise the following points:

- The type of research performed by the researcher

- Methods employed to gather and filter information

- Techniques that were chosen for analysis

- Materials, tools and resources used to conduct research (typically for empirical research dissertations)

- Limitations of your chosen methods

- Reliability and validity of your measuring tools and instruments (e.g. a survey questionnaire) are also typically mentioned within the mythology section. If you used a pre-existing data collection tool, cite its reliability/validity estimates here, too.Make use of the past tense when writing the methodology chapter.

Dissertation Findings

The key results of your research are presented in the dissertation findings chapter . It gives authors the ability to validate their own intellectual and analytical skills

Dissertation Conclusion

Cap off your dissertation paper with a study summary and a brief report of the findings. In the concluding chapter , you will be expected to demonstrate how your research will provide value to other academics in your area of study and its implications.It is recommended to include a short ‘recommendations’ section that will elaborate on the purpose and need for future research to elucidate the topic further.

Follow the referencing style following the requirements of your academic degree or field of study. Make sure to list every academic source used with a proper in-text citation. It is important to give credit to other authors’ ideas and concepts.

Note: Keep in mind whether you are creating a reference list or a bibliography. The former includes information about all the various sources you referred to, read from or took inspiration from for your own study. However, the latter contains things you used and those you only read but didn’t cite in your dissertation.

Proofread, Edit and Improve – Don’t Risk Months of Hard Work.

Experts recommend completing the total dissertation before starting to proofread and edit your work. You need to refresh your focus and reboot your creative brain before returning to another critical stage.

Leave space of at least a few days between the writing and the editing steps so when you get back to the desk, you can recognise your grammar, spelling and factual errors when you get back to the desk.

It is crucial to consider this period to ensure the final work is polished, coherent, well-structured and free of any structural or factual flaws. Daniel Higginbotham from Prospects UK states that:

“Leave yourself sufficient time to engage with your writing at several levels – from reassessing the logic of the whole piece to proofreading to checking you’ve paid attention to aspects such as the correct spelling of names and theories and the required referencing format.”

What is the Difference Between Editing and Proofreading?

Editing means that you are focusing on the essence of your dissertation paper. In contrast, proofreading is the process of reviewing the final draft piece to ensure accuracy and consistency in formatting, spelling, facts, punctuation, and grammar.

Editing: Prepare your work for submission by condensing, correcting and modifying (where necessary). When reviewing the paper, make sure that there are coherence and consistency between the arguments you presented.

If an information gap has been identified, fill that with an appropriate piece of information gathered during the research process. It is easy to lose sight of the original purpose if you become over-involved when writing.

Cut out the unwanted text and refine it, so your paper’s content is to the point and concise.Proofreading: Start proofreading your paper to identify formatting, structural, grammar, punctuation and referencing flaws. Read every single sentence of the paper no matter how tired you are because a few puerile mistakes can compromise your months of hard work.

Many students struggle with the editing and proofreading stages due to their lack of attention to detail. Consult a skilled dissertation editor if you are unable to find your flaws. You may want to invest in a professional dissertation editing and proofreading service to improve the piece’s quality to First Class.

Tips for Writing a Dissertation

Communication with supervisor – get feedback.

Communicate regularly with your supervisor to produce a first-class dissertation paper. Request them to comprehensively review the contents of your dissertation paper before final submission.

Their constructive criticism and feedback concerning different study areas will help you improve your piece’s overall quality. Keep your supervisor updated about your research progress and discuss any problems that you come up against.

Organising your Time

A dissertation is a lengthy project spanning over a period of months to years, and therefore it is important to avoid procrastination. Stay focused, and manage your time efficiently. Here are some time management tips for writing your dissertation to help you make the most of your time as you research and write.

- Don’t be discouraged by the inherently slow nature of dissertation work, particularly in the initial stages.

- Set clear goals and work out your research and write up a plan accordingly.

- Allow sufficient time to incorporate feedback from your supervisor.

- Leave enough time for editing, improving, proofreading, and formatting the paper according to your school’s guidelines. This is where you break or make your grade.

- Work a certain number of hours on your paper daily.

- Create a worksheet for your week.

- Work on your dissertation for time periods as brief as 45 minutes or less.

- Stick to the strategic dissertation timeline, so you don’t have to do the catchup work.

- Meet your goals by prioritising your dissertation work.

- Strike a balance between being overly organised and needing to be more organised.

- Limit activities other than dissertation writing and your most necessary obligations.

- Keep ‘tangent’ and ‘for the book’ files.

- Create lists to help you manage your tasks.

- Have ‘filler’ tasks to do when you feel burned out or in need of intellectual rest.

- Keep a dissertation journal.

- Pretend that you are working in a more structured work world.

- Limit your usage of email and personal electronic devices.

- Utilise and build on your past work when you write your dissertation.

- Break large tasks into small manageable ones.

- Seek advice from others, and do not be afraid to ask for help.

Dissertation Examples

Here are some samples of a dissertation to inspire you to write mind-blowing dissertations and to help bring all the above-mentioned guidelines home.

DE MONTFORT University Leicester – Examples of recent dissertations

Dissertation Research in Education: Dissertations (Examples)

How Long is a Dissertation?

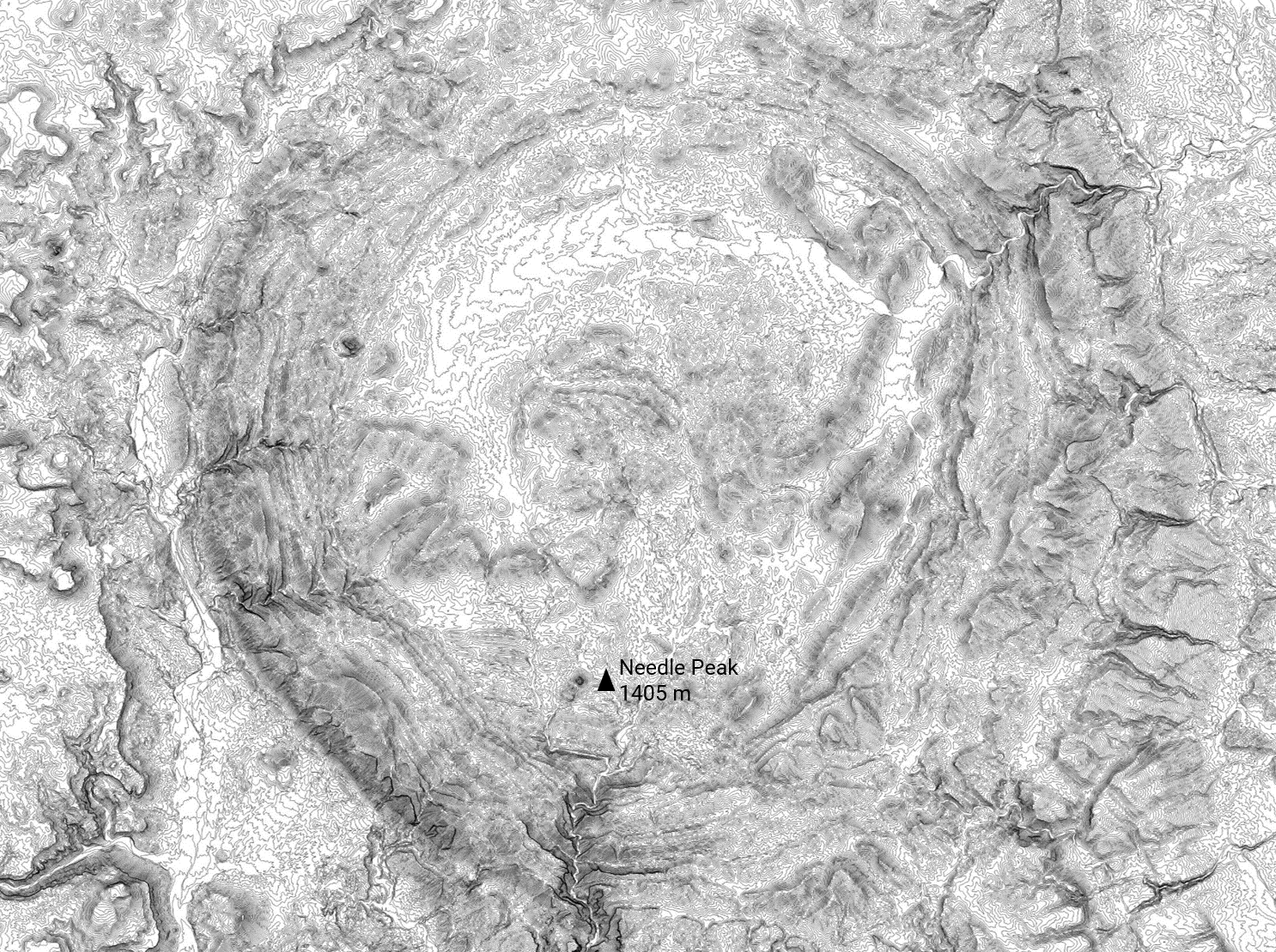

The entire dissertation writing process is complicated and spans over a period of months to years, depending on whether you are an undergraduate, master’s, or PhD candidate. Marcus Beck, a PhD candidate, conducted fundamental research a few years ago, research that didn’t have much to do with his research but returned answers to some niggling questions every student has about the average length of a dissertation.

A software program specifically designed for this purpose helped Beck to access the university’s electronic database to uncover facts on dissertation length.

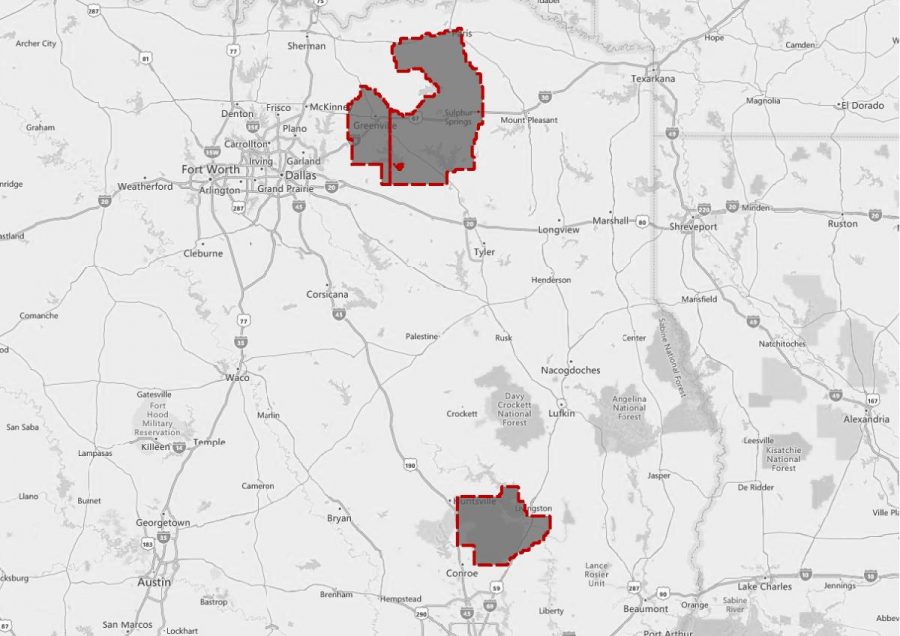

The above illustration shows how the results of his small study were a little unsurprising. Social sciences and humanities disciplines such as anthropology, politics, and literature had the longest dissertations, with some PhD dissertations comprising 150,000 words or more.Engineering and scientific disciplines, on the other hand, were considerably shorter. PhD-level dissertations generally don’t have a predefined length as they will vary with your research topic. Ask your school about this requirement if you are unsure about it from the start.

Focus more on the quality of content rather than the number of pages.

Hire an Expert Writer

Orders completed by our expert writers are

- Formally drafted in an academic style

- Free Amendments and 100% Plagiarism Free – or your money back!

- 100% Confidential and Timely Delivery!

- Free anti-plagiarism report

- Appreciated by thousands of clients. Check client reviews

Phrases to Avoid

No matter the style or structure you follow, it is best to keep your language simple. Avoid the use of buzzwords and jargon.

A Word on Stealing Content (Plagiarism)

Very straightforward advice to all students, DO NOT PLAGIARISE. Plagiarism is a serious offence. You will be penalised heavily if you are caught plagiarising. Don’t risk years of hard work, as many students in the past have lost their degrees for plagiarising. Here are some tips to help you make sure you don’t get caught.

- Copying and pasting from an academic source is an unforgivable sin. Rephrasing text retrieved from another source also falls under plagiarism; it’s called paraphrasing. Summarising another’s idea(s) word-to-word, paraphrasing, and copy-pasting are the three primary forms plagiarism can take.

- If you must directly copy full sentences from another source because they fill the bill, always enclose them inside quotation marks and acknowledge the writer’s work with in-text citations.

Are you struggling to find inspiration to get going? Still, trying to figure out where to begin? Is the deadline getting closer? Don’t be overwhelmed! ResearchProspect dissertation writing services have helped thousands of students achieve desired outcomes. Click here to get help from writers holding either a master's or PhD degree from a reputed UK university.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does a dissertation include.

A dissertation has main chapters and parts that support them. The main parts are:

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Research Methodology

- Your conclusion

Other parts are the abstract, references, appendices etc. We can supply a full dissertation or specific parts of one.

What is the difference between research and a dissertation?

A research paper is a sort of academic writing that consists of the study, source assessment, critical thinking, organisation, and composition, as opposed to a thesis or dissertation, which is a lengthy academic document that often serves as the final project for a university degree.

Can I edit and proofread my dissertation myself?

Of course, you can do proofreading and editing of your dissertation. There are certain rules to follow that have been discussed above. However, finding mistakes in something that you have written yourself can be complicated for some people. It is advisable to take professional help in the matter.

What If I only have difficulty writing a specific chapter of the dissertation?

ResearchProspect ensures customer satisfaction by addressing all relevant issues. We provide dissertation chapter-writing services to students if they need help completing a specific chapter. It could be any chapter from the introduction, literature review, and methodology to the discussion and conclusion.

You May Also Like

Are you looking for intriguing and trending dissertation topics? Get inspired by our list of free dissertation topics on all subjects.

Looking for an easy guide to follow to write your essay? Here is our detailed essay guide explaining how to write an essay and examples and types of an essay.

Learn about the steps required to successfully complete their research project. Make sure to follow these steps in their respective order.

More Interesting Articles

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

- 1-888-SNU-GRAD

- Daytime Classes

The Dissertation Process Explained in 6 Simple Steps

Completing your doctoral program is no easy feat, yet the payoff makes it all worthwhile. You’ll challenge yourself with academic rigor and defend your thesis as you showcase your knowledge to a panel of experts.

One of the hardest parts of the dissertation process is simply getting started. Here are six steps to guide you to successfully earning your doctoral degree by tackling your dissertation, from start to finish.

Step 1: Brainstorm Topics

Finding a research topic that’s right for you and your doctoral studies requires some serious thought. A doctoral program can take years to complete, so it’s important you choose a topic that you’re passionate about. Whether that’s in the field of education administration or entrepreneurship, find an area of study that suits your academic interests and career goals.

As a doctoral candidate, you’ll take on the role of an independent researcher, which means you’ll be facilitating your own studies and academic milestones. Choose a topic that gets your wheels turning and stirs up an urgent sense of curiosity. However, take note that not every idea will suit a doctoral dissertation and the manuscript formatting. Many students make the mistake of choosing a topic that is too broad. Doctoral dissertations must be researchable and demonstrative based on qualitative or quantitative data.

Do some preliminary research to determine if someone has already conducted similar research. Being flexible with your brainstorming will allow you to refine your topic with ease. Take constructive criticism from peers and mentors seriously so that you set yourself up for success from day one. If you find yourself feeling a bit lost, don’t be afraid to turn to experts in your field for their opinion. At this initial stage of the dissertation process, you should be the most open to exploring new ideas and refining your area of research.

Step 2: Find a Faculty Mentor and Committee Assignment

Once your topic is approved by the university, you’ll be tasked with selecting a faculty mentor. Finding a faculty chairperson is one of the most important steps you will take in your dissertation process , apart from crafting and delivering your manuscript. After all, your mentor will guide your academic work over the course of your doctoral studies for the next several years. You two will develop a working relationship, so it’s crucial that you choose a mentor you can collaborate and communicate with effectively.

At most universities, your faculty chair will be dedicated to the dissertation process full time. That means they will have the skills, expertise and time to support all of your needs. However, for the other members of your dissertation committee, you’ll want to consider logistics as well. You may have a dream faculty mentor you’d appreciate working with, but they must have the time and attention to dedicate to make the investment worthwhile for you both. Be upfront about your intended timeline, weekly and monthly time commitment, and expectations around communication. When you approach a faculty member about serving as part of your dissertation committee, leave the door open for them to say “no,” so you’re sure to find the right fit and someone who can commit in the long run.

Some universities make the selection process easy by assigning a dissertation chair and committee to you. For example, doctoral students at SNU are assigned a committee comprised of four people: a dissertation chair within the program’s department, a second departmental faculty member, a member from outside the department who has scholarly expertise in the student’s research topic, and the Dissertation Director who coordinates all communication among the committee members.

Step 3: Develop and Submit a Proposal

Think of the proposal as an opportunity for you to both suss out your ideas and create a convincing argument to present to the faculty committee. Your proposal is the first look at your thesis statement, where you:

- Introduce the topic

- Pose a set of related topics

- Outline the qualitative and quantitative data you hope to extract through careful research

Again, be open to critical feedback. During this stage, you have the opportunity to reflect and refine the direction of your research. Faculty members will likely reciprocate your proposal with pointed questions that identify gaps in your proposal development or information-seeking process.

You’ll go through a set of one or more revisions based on faculty feedback. You’ll then submit your proposal application for final approval. Once you have the entire committee’s approval, you’ll begin to collect data.

Step 4: Conduct Research and Data Analysis

In your proposal, you’ll outline your plan to conduct careful research, collect data and analyze that data. Throughout the research process, refer back to your outline to chart your own progress and to build a collection of measurable results to present to your faculty mentor.

The next step is to add the data you collect to your proposal in two sections. The first section will summarize the data, and the second will offer an interpretation of that data. This step also lends itself to a series of revisions between you and the dissertation committee. Be prepared to implement those changes as you begin to draft your manuscript .

Step 5: Draft Your Manuscript

First, consult with your university’s policies and procedures regarding the doctoral manuscript academic requirements and scholarly style. Check with your department to inquire about additional departmental procedures.

Consider Your Format

Develop a consistent format in the early stages, so that submitting your thesis to the Advisory Committee and Examining Committee will run smoothly and you can receive swift feedback. You want to create both a professional and intuitive system for the academic committee and your general audience to be able to easily peruse your thesis.

Pay close attention to proper sourcing of previously published content and provide a numbering system (page numbers and charts) that reflects the formatting of your thesis, not the numbering system of a previous publication. Devise chapter layout with the same level of scrutiny. Number chapters sequentially, and create a uniform system to label all charts, tables and equations. And last but not least, be sure to follow standard grammatical conventions, including spelling and punctuation.

Cite Your Sources

As you gather research and develop your manuscript, you must cite your sources accurately and consistently. Check with your department ahead of time in case you should be formatting your resources according to specific departmental standards. In the absence of departmental standards, create a format of your own that you can adhere to with consistency. Most doctoral candidates will choose to include sources at the end of each chapter or in one single list at the end of their dissertation.

Craft Your Content

You’ll spend the bulk of your time crafting the content of the manuscript itself . You’ll begin by summarizing relevant sourcing and reviewing related literature. The purpose of this first section is to establish your expertise in the field, establish clear objectives for your research, identify the broader context within which the research resides, and provide more acute context for the data itself. You’ll then discuss the methods of analyzing the research before transitioning into data analysis in a chapter-by-chapter breakdown. Finally, in your conclusion, you’ll link your direct research to the larger picture and the implications of its impact in your field.

Step 6: Defend Your Thesis

The pinnacle of your research will be defending your thesis in front of a panel of experts — the dissertation committee. Sometimes this takes place in person, or, as has proved increasingly common during the past year, by video/voice conferencing.

This is your opportunity to demonstrate all that you have learned over multiple years of careful research and analysis. The committee will pose questions to both clarify and challenge your level of knowledge in an impromptu fashion. In some cases, based on the committee’s perception, you may need to submit a secondary oral defense. Ultimately, the committee will determine a successful delivery of your dissertation and the chance to proudly assert your doctoral status after completing all degree requirements.

No matter which path you choose to pursue en route to your doctoral, online and in-person education options can make your dream of completing your degree one step closer to reality. Take a look at SNU’s online and on-campus course offerings today.

Want to learn more about SNU's programs?

Request more information.

Have questions about SNU, our program, or how we can help you succeed. Fill out the form and an enrollment counselor will reach out to you soon!

Subscribe to the SNU blog for inspirational articles and tips to support you on your journey back to school.

Recent blog articles.

Building Special Ed Leaders: A Deep Dive into SNU's MAASE Program

Adult Education

What is unique about the MBA program at SNU?

Online Degree Programs

Growing Career Opportunities for Healthcare Administration Degrees

Southern Nazarene University's Dr. Delilah Joiner Martin Named 2024 Oklahoma Mother of the Year

Have questions about SNU or need help determining which program is the right fit? Fill out the form and an enrollment counselor will follow-up to answer your questions!

Text With an Enrollment Counselor

Have questions, but want a faster response? Fill out the form and one of our enrollment counselors will follow-up via text shortly!

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Dissertation – Format, Example and Template

Dissertation – Format, Example and Template

Table of Contents

Dissertation

Definition:

Dissertation is a lengthy and detailed academic document that presents the results of original research on a specific topic or question. It is usually required as a final project for a doctoral degree or a master’s degree.

Dissertation Meaning in Research

In Research , a dissertation refers to a substantial research project that students undertake in order to obtain an advanced degree such as a Ph.D. or a Master’s degree.

Dissertation typically involves the exploration of a particular research question or topic in-depth, and it requires students to conduct original research, analyze data, and present their findings in a scholarly manner. It is often the culmination of years of study and represents a significant contribution to the academic field.

Types of Dissertation

Types of Dissertation are as follows:

Empirical Dissertation

An empirical dissertation is a research study that uses primary data collected through surveys, experiments, or observations. It typically follows a quantitative research approach and uses statistical methods to analyze the data.

Non-Empirical Dissertation

A non-empirical dissertation is based on secondary sources, such as books, articles, and online resources. It typically follows a qualitative research approach and uses methods such as content analysis or discourse analysis.

Narrative Dissertation

A narrative dissertation is a personal account of the researcher’s experience or journey. It typically follows a qualitative research approach and uses methods such as interviews, focus groups, or ethnography.

Systematic Literature Review

A systematic literature review is a comprehensive analysis of existing research on a specific topic. It typically follows a qualitative research approach and uses methods such as meta-analysis or thematic analysis.

Case Study Dissertation

A case study dissertation is an in-depth analysis of a specific individual, group, or organization. It typically follows a qualitative research approach and uses methods such as interviews, observations, or document analysis.

Mixed-Methods Dissertation

A mixed-methods dissertation combines both quantitative and qualitative research approaches to gather and analyze data. It typically uses methods such as surveys, interviews, and focus groups, as well as statistical analysis.

How to Write a Dissertation

Here are some general steps to help guide you through the process of writing a dissertation:

- Choose a topic : Select a topic that you are passionate about and that is relevant to your field of study. It should be specific enough to allow for in-depth research but broad enough to be interesting and engaging.

- Conduct research : Conduct thorough research on your chosen topic, utilizing a variety of sources, including books, academic journals, and online databases. Take detailed notes and organize your information in a way that makes sense to you.

- Create an outline : Develop an outline that will serve as a roadmap for your dissertation. The outline should include the introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion.

- Write the introduction: The introduction should provide a brief overview of your topic, the research questions, and the significance of the study. It should also include a clear thesis statement that states your main argument.

- Write the literature review: The literature review should provide a comprehensive analysis of existing research on your topic. It should identify gaps in the research and explain how your study will fill those gaps.

- Write the methodology: The methodology section should explain the research methods you used to collect and analyze data. It should also include a discussion of any limitations or weaknesses in your approach.

- Write the results: The results section should present the findings of your research in a clear and organized manner. Use charts, graphs, and tables to help illustrate your data.

- Write the discussion: The discussion section should interpret your results and explain their significance. It should also address any limitations of the study and suggest areas for future research.

- Write the conclusion: The conclusion should summarize your main findings and restate your thesis statement. It should also provide recommendations for future research.

- Edit and revise: Once you have completed a draft of your dissertation, review it carefully to ensure that it is well-organized, clear, and free of errors. Make any necessary revisions and edits before submitting it to your advisor for review.

Dissertation Format

The format of a dissertation may vary depending on the institution and field of study, but generally, it follows a similar structure:

- Title Page: This includes the title of the dissertation, the author’s name, and the date of submission.

- Abstract : A brief summary of the dissertation’s purpose, methods, and findings.

- Table of Contents: A list of the main sections and subsections of the dissertation, along with their page numbers.

- Introduction : A statement of the problem or research question, a brief overview of the literature, and an explanation of the significance of the study.

- Literature Review : A comprehensive review of the literature relevant to the research question or problem.

- Methodology : A description of the methods used to conduct the research, including data collection and analysis procedures.

- Results : A presentation of the findings of the research, including tables, charts, and graphs.

- Discussion : A discussion of the implications of the findings, their significance in the context of the literature, and limitations of the study.

- Conclusion : A summary of the main points of the study and their implications for future research.

- References : A list of all sources cited in the dissertation.

- Appendices : Additional materials that support the research, such as data tables, charts, or transcripts.

Dissertation Outline

Dissertation Outline is as follows:

Title Page:

- Title of dissertation

- Author name

- Institutional affiliation

- Date of submission

- Brief summary of the dissertation’s research problem, objectives, methods, findings, and implications

- Usually around 250-300 words

Table of Contents:

- List of chapters and sections in the dissertation, with page numbers for each

I. Introduction

- Background and context of the research

- Research problem and objectives

- Significance of the research

II. Literature Review

- Overview of existing literature on the research topic

- Identification of gaps in the literature

- Theoretical framework and concepts

III. Methodology

- Research design and methods used

- Data collection and analysis techniques

- Ethical considerations

IV. Results

- Presentation and analysis of data collected

- Findings and outcomes of the research

- Interpretation of the results

V. Discussion

- Discussion of the results in relation to the research problem and objectives

- Evaluation of the research outcomes and implications

- Suggestions for future research

VI. Conclusion

- Summary of the research findings and outcomes

- Implications for the research topic and field

- Limitations and recommendations for future research

VII. References

- List of sources cited in the dissertation

VIII. Appendices

- Additional materials that support the research, such as tables, figures, or questionnaires.

Example of Dissertation

Here is an example Dissertation for students:

Title : Exploring the Effects of Mindfulness Meditation on Academic Achievement and Well-being among College Students

This dissertation aims to investigate the impact of mindfulness meditation on the academic achievement and well-being of college students. Mindfulness meditation has gained popularity as a technique for reducing stress and enhancing mental health, but its effects on academic performance have not been extensively studied. Using a randomized controlled trial design, the study will compare the academic performance and well-being of college students who practice mindfulness meditation with those who do not. The study will also examine the moderating role of personality traits and demographic factors on the effects of mindfulness meditation.

Chapter Outline:

Chapter 1: Introduction

- Background and rationale for the study

- Research questions and objectives

- Significance of the study

- Overview of the dissertation structure

Chapter 2: Literature Review

- Definition and conceptualization of mindfulness meditation

- Theoretical framework of mindfulness meditation

- Empirical research on mindfulness meditation and academic achievement

- Empirical research on mindfulness meditation and well-being

- The role of personality and demographic factors in the effects of mindfulness meditation

Chapter 3: Methodology

- Research design and hypothesis

- Participants and sampling method

- Intervention and procedure

- Measures and instruments

- Data analysis method

Chapter 4: Results

- Descriptive statistics and data screening

- Analysis of main effects

- Analysis of moderating effects

- Post-hoc analyses and sensitivity tests

Chapter 5: Discussion

- Summary of findings

- Implications for theory and practice

- Limitations and directions for future research

- Conclusion and contribution to the literature

Chapter 6: Conclusion

- Recap of the research questions and objectives

- Summary of the key findings

- Contribution to the literature and practice

- Implications for policy and practice

- Final thoughts and recommendations.

References :

List of all the sources cited in the dissertation

Appendices :

Additional materials such as the survey questionnaire, interview guide, and consent forms.

Note : This is just an example and the structure of a dissertation may vary depending on the specific requirements and guidelines provided by the institution or the supervisor.

How Long is a Dissertation

The length of a dissertation can vary depending on the field of study, the level of degree being pursued, and the specific requirements of the institution. Generally, a dissertation for a doctoral degree can range from 80,000 to 100,000 words, while a dissertation for a master’s degree may be shorter, typically ranging from 20,000 to 50,000 words. However, it is important to note that these are general guidelines and the actual length of a dissertation can vary widely depending on the specific requirements of the program and the research topic being studied. It is always best to consult with your academic advisor or the guidelines provided by your institution for more specific information on dissertation length.

Applications of Dissertation

Here are some applications of a dissertation:

- Advancing the Field: Dissertations often include new research or a new perspective on existing research, which can help to advance the field. The results of a dissertation can be used by other researchers to build upon or challenge existing knowledge, leading to further advancements in the field.

- Career Advancement: Completing a dissertation demonstrates a high level of expertise in a particular field, which can lead to career advancement opportunities. For example, having a PhD can open doors to higher-paying jobs in academia, research institutions, or the private sector.

- Publishing Opportunities: Dissertations can be published as books or journal articles, which can help to increase the visibility and credibility of the author’s research.

- Personal Growth: The process of writing a dissertation involves a significant amount of research, analysis, and critical thinking. This can help students to develop important skills, such as time management, problem-solving, and communication, which can be valuable in both their personal and professional lives.

- Policy Implications: The findings of a dissertation can have policy implications, particularly in fields such as public health, education, and social sciences. Policymakers can use the research to inform decision-making and improve outcomes for the population.

When to Write a Dissertation

Here are some situations where writing a dissertation may be necessary:

- Pursuing a Doctoral Degree: Writing a dissertation is usually a requirement for earning a doctoral degree, so if you are interested in pursuing a doctorate, you will likely need to write a dissertation.

- Conducting Original Research : Dissertations require students to conduct original research on a specific topic. If you are interested in conducting original research on a topic, writing a dissertation may be the best way to do so.

- Advancing Your Career: Some professions, such as academia and research, may require individuals to have a doctoral degree. Writing a dissertation can help you advance your career by demonstrating your expertise in a particular area.

- Contributing to Knowledge: Dissertations are often based on original research that can contribute to the knowledge base of a field. If you are passionate about advancing knowledge in a particular area, writing a dissertation can help you achieve that goal.

- Meeting Academic Requirements : If you are a graduate student, writing a dissertation may be a requirement for completing your program. Be sure to check with your academic advisor to determine if this is the case for you.

Purpose of Dissertation

some common purposes of a dissertation include:

- To contribute to the knowledge in a particular field : A dissertation is often the culmination of years of research and study, and it should make a significant contribution to the existing body of knowledge in a particular field.

- To demonstrate mastery of a subject: A dissertation requires extensive research, analysis, and writing, and completing one demonstrates a student’s mastery of their subject area.

- To develop critical thinking and research skills : A dissertation requires students to think critically about their research question, analyze data, and draw conclusions based on evidence. These skills are valuable not only in academia but also in many professional fields.

- To demonstrate academic integrity: A dissertation must be conducted and written in accordance with rigorous academic standards, including ethical considerations such as obtaining informed consent, protecting the privacy of participants, and avoiding plagiarism.

- To prepare for an academic career: Completing a dissertation is often a requirement for obtaining a PhD and pursuing a career in academia. It can demonstrate to potential employers that the student has the necessary skills and experience to conduct original research and make meaningful contributions to their field.

- To develop writing and communication skills: A dissertation requires a significant amount of writing and communication skills to convey complex ideas and research findings in a clear and concise manner. This skill set can be valuable in various professional fields.

- To demonstrate independence and initiative: A dissertation requires students to work independently and take initiative in developing their research question, designing their study, collecting and analyzing data, and drawing conclusions. This demonstrates to potential employers or academic institutions that the student is capable of independent research and taking initiative in their work.

- To contribute to policy or practice: Some dissertations may have a practical application, such as informing policy decisions or improving practices in a particular field. These dissertations can have a significant impact on society, and their findings may be used to improve the lives of individuals or communities.

- To pursue personal interests: Some students may choose to pursue a dissertation topic that aligns with their personal interests or passions, providing them with the opportunity to delve deeper into a topic that they find personally meaningful.

Advantage of Dissertation

Some advantages of writing a dissertation include:

- Developing research and analytical skills: The process of writing a dissertation involves conducting extensive research, analyzing data, and presenting findings in a clear and coherent manner. This process can help students develop important research and analytical skills that can be useful in their future careers.

- Demonstrating expertise in a subject: Writing a dissertation allows students to demonstrate their expertise in a particular subject area. It can help establish their credibility as a knowledgeable and competent professional in their field.

- Contributing to the academic community: A well-written dissertation can contribute new knowledge to the academic community and potentially inform future research in the field.

- Improving writing and communication skills : Writing a dissertation requires students to write and present their research in a clear and concise manner. This can help improve their writing and communication skills, which are essential for success in many professions.

- Increasing job opportunities: Completing a dissertation can increase job opportunities in certain fields, particularly in academia and research-based positions.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

Academic & Employability Skills

Subscribe to academic & employability skills.

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Join 397 other subscribers.

Email Address

Writing your dissertation - structure and sections

Posted in: dissertations

In this post, we look at the structural elements of a typical dissertation. Your department may wish you to include additional sections but the following covers all core elements you will need to work on when designing and developing your final assignment.

The table below illustrates a classic dissertation layout with approximate lengths for each section.

Hopkins, D. and Reid, T., 2018. The Academic Skills Handbook: Your Guid e to Success in Writing, Thinking and Communicating at University . Sage.

Your title should be clear, succinct and tell the reader exactly what your dissertation is about. If it is too vague or confusing, then it is likely your dissertation will be too vague and confusing. It is important therefore to spend time on this to ensure you get it right, and be ready to adapt to fit any changes of direction in your research or focus.

In the following examples, across a variety of subjects, you can see how the students have clearly identified the focus of their dissertation, and in some cases target a problem that they will address:

An econometric analysis of the demand for road transport within the united Kingdom from 1965 to 2000

To what extent does payment card fraud affect UK bank profitability and bank stakeholders? Does this justify fraud prevention?

A meta-analysis of implant materials for intervertebral disc replacement and regeneration.

The role of ethnic institutions in social development; the case of Mombasa, Kenya.

Why haven’t biomass crops been adopted more widely as a source of renewable energy in the United Kingdom?

Mapping the criminal mind: Profiling and its limitation.

The Relative Effectiveness of Interferon Therapy for Chronic Hepatitis C

Under what conditions did the European Union exhibit leadership in international climate change negotiations from 1992-1997, 1997-2005 and 2005-Copenhagen respectively?

The first thing your reader will read (after the title) is your abstract. However, you need to write this last. Your abstract is a summary of the whole project, and will include aims and objectives, methods, results and conclusions. You cannot write this until you have completed your write-up (look at our six point checklist for writing an abstract ).

Introduction

Your introduction should include the same elements found in most academic essay or report assignments, with the possible inclusion of research questions. The aim of the introduction is to set the scene, contextualise your research, introduce your focus topic and research questions, and tell the reader what you will be covering. It should move from the general and work towards the specific. You should include the following:

- Attention-grabbing statement (a controversy, a topical issue, a contentious view, a recent problem etc)

- Background and context

- Introduce the topic, key theories, concepts, terms of reference, practices, (advocates and critic)

- Introduce the problem and focus of your research

- Set out your research question(s) (this could be set out in a separate section)

- Your approach to answering your research questions.

See also Writing your introduction .

Literature review

Your literature review is the section of your report where you show what is already known about the area under investigation and demonstrate the need for your particular study. This is a significant section in your dissertation (30%) and you should allow plenty of time to carry out a thorough exploration of your focus topic and use it to help you identify a specific problem and formulate your research questions.

You should approach the literature review with the critical analysis dial turned up to full volume. This is not simply a description, list, or summary of everything you have read. Instead, it is a synthesis of your reading, and should include analysis and evaluation of readings, evidence, studies and data, cases, real world applications and views/opinions expressed. Your supervisor is looking for this detailed critical approach in your literature review, where you unpack sources, identify strengths and weaknesses and find gaps in the research.

In other words, your literature review is your opportunity to show the reader why your paper is important and your research is significant, as it addresses the gap or on-going issue you have uncovered.

See also: Developing your literature review - getting started and Developing your literature review - top tips

You need to tell the reader what was done. This means describing the research methods and explaining your choice. This will include information on the following:

- Are your methods qualitative or quantitative... or both? And if so, why?

- Who (if any) are the participants?

- Are you analysing any documents, systems, organisations? If so what are they and why are you analysing them?

- What did you do first, second, etc?

- What ethical considerations are there?

It is a common style convention to write what was done rather than what you did, and write it so that someone else would be able to replicate your study.

Here you describe what you have found out. You need to identify the most significant patterns in your data, and use tables and figures to support your description. Your tables and figures are a visual representation of your findings, but remember to describe what they show in your writing. There should be no critical analysis in this part (unless you have combined results and discussion sections).

Here you show the significance of your results or findings. You critically analyse what they mean, and what the implications may be. Talk about any limitations to your study, evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of your own research, and make suggestions for further studies to build on your findings. In this section, your supervisor will expect you to dig deep into your findings and critically evaluate what they mean in relation to previous studies, theories, views and opinions.

This is a summary of your project, reminding the reader of the background to your study, your objectives, and showing how you met them. Do not include any new information that you have not discussed before.

This is the list of all the sources you have cited in your dissertation. Ensure you are consistent and follow the conventions for the particular referencing system you are using. (Note: you shouldn't include books you've read but do not appear in your dissertation).

Include any extra information that your reader may like to read. It should not be essential for your reader to read them in order to understand your dissertation. Your appendices should be labelled (e.g. Appendix A, Appendix B, etc). Examples of material for the appendices include detailed data tables (summarised in your results section), the complete version of a document you have used an extract from, etc.

Adapted from: https://www2.le.ac.uk/offices/ld/all-resources/writing/writing-resources/planning-and-conducting-a-dissertation-research-project

Share this:.

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Click here to cancel reply.

- Email * (we won't publish this)

Write a response

I am finding this helpful. Thank You.

It is very useful.

Glad you found it useful Adil!

I was a useful post i would like to thank you

Glad you found it useful! 🙂

Navigating the dissertation process: my tips for final years

Imagine for a moment... After months of hard work and research on a topic you're passionate about, the time has finally come to click the 'Submit' button on your dissertation. You've just completed your longest project to date as part...

8 ways to beat procrastination

Whether you’re writing an assignment or revising for exams, getting started can be hard. Fortunately, there’s lots you can do to turn procrastination into action.

My takeaways on how to write a scientific report

If you’re in your dissertation writing stage or your course includes writing a lot of scientific reports, but you don’t quite know where and how to start, the Skills Centre can help you get started. I recently attended their ‘How...

Selecting Research Area

Selecting a research area is the very first step in writing your dissertation. It is important for you to choose a research area that is interesting to you professionally, as well as, personally. Experienced researchers note that “a topic in which you are only vaguely interested at the start is likely to become a topic in which you have no interest and with which you will fail to produce your best work” [1] . Ideally, your research area should relate to your future career path and have a potential to contribute to the achievement of your career objectives.

The importance of selecting a relevant research area that is appropriate for dissertation is often underestimated by many students. This decision cannot be made in haste. Ideally, you should start considering different options at the beginning of the term. However, even when there are only few weeks left before the deadline and you have not chosen a particular topic yet, there is no need to panic.

There are few areas in business studies that can offer interesting topics due to their relevance to business and dynamic nature. The following is the list of research areas and topics that can prove to be insightful in terms of assisting you to choose your own dissertation topic.

Globalization can be a relevant topic for many business and economics dissertations. Forces of globalization are nowadays greater than ever before and dissertations can address the implications of these forces on various aspects of business.

Following are few examples of research areas in globalization:

- A study of implications of COVID-19 pandemic on economic globalization

- Impacts of globalization on marketing strategies of beverage manufacturing companies: a case study of The Coca-Cola Company

- Effects of labour migration within EU on the formation of multicultural teams in UK organizations

- A study into advantages and disadvantages of various entry strategies to Chinese market

- A critical analysis of the effects of globalization on US-based businesses

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is also one of the most popular topics at present and it is likely to remain so for the foreseeable future. CSR refers to additional responsibilities of business organizations towards society apart from profit maximization. There is a high level of controversy involved in CSR. This is because businesses can be socially responsible only at the expense of their primary objective of profit maximization.

Perspective researches in the area of CSR may include the following:

- The impacts of CSR programs and initiatives on brand image: a case study of McDonald’s India

- A critical analysis of argument of mandatory CSR for private sector organizations in Australia

- A study into contradictions between CSR programs and initiatives and business practices: a case study of Philip Morris Philippines

- A critical analysis into the role of CSR as an effective marketing tool

- A study into the role of workplace ethics for improving brand image

Social Media and viral marketing relate to increasing numbers of various social networking sites such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube etc. Increasing levels of popularity of social media among various age groups create tremendous potential for businesses in terms of attracting new customers.

The following can be listed as potential studies in the area of social media:

- A critical analysis of the use of social media as a marketing strategy: a case study of Burger King Malaysia

- An assessment of the role of Instagram as an effective platform for viral marketing campaigns

- A study into the sustainability of TikTok as a marketing tool in the future

- An investigation into the new ways of customer relationship management in mobile marketing environment: a case study of catering industry in South Africa

- A study into integration of Twitter social networking website within integrated marketing communication strategy: a case study of Microsoft Corporation

Culture and cultural differences in organizations offer many research opportunities as well. Increasing importance of culture is directly related to intensifying forces of globalization in a way that globalization forces are fuelling the formation of cross-cultural teams in organizations.

Perspective researches in the area of culture and cultural differences in organizations may include the following:

- The impact of cross-cultural differences on organizational communication: a case study of BP plc

- A study into skills and competencies needed to manage multicultural teams in Singapore

- The role of cross-cultural differences on perception of marketing communication messages in the global marketplace: a case study of Apple Inc.

- Effects of organizational culture on achieving its aims and objectives: a case study of Virgin Atlantic

- A critical analysis into the emergence of global culture and its implications in local automobile manufacturers in Germany

Leadership and leadership in organizations has been a popular topic among researchers for many decades by now. However, the importance of this topic may be greater now than ever before. This is because rapid technological developments, forces of globalization and a set of other factors have caused markets to become highly competitive. Accordingly, leadership is important in order to enhance competitive advantages of organizations in many ways.

The following studies can be conducted in the area of leadership:

- Born or bred: revisiting The Great Man theory of leadership in the 21 st century

- A study of effectiveness of servant leadership style in public sector organizations in Hong Kong

- Creativity as the main trait for modern leaders: a critical analysis

- A study into the importance of role models in contributing to long-term growth of private sector organizations: a case study of Tata Group, India

- A critical analysis of leadership skills and competencies for E-Commerce organizations

COVID-19 pandemic and its macro and micro-economic implications can also make for a good dissertation topic. Pandemic-related crisis has been like nothing the world has seen before and it is changing international business immensely and perhaps, irreversibly as well.

The following are few examples for pandemic crisis-related topics:

- A study into potential implications of COVID-19 pandemic into foreign direct investment in China

- A critical assessment of effects of COVID-19 pandemic into sharing economy: a case study of AirBnb.

- The role of COVID-19 pandemic in causing shifts in working patterns: a critical analysis

Moreover, dissertations can be written in a wide range of additional areas such as customer services, supply-chain management, consumer behaviour, human resources management, catering and hospitality, strategic management etc. depending on your professional and personal interests.

[1] Saunders, M., Lewis, P. & Thornhill, A. (2012) “Research Methods for Business Students” 6th edition, Pearson Education Limited.

John Dudovskiy

info This is a space for the teal alert bar.

notifications This is a space for the yellow alert bar.

Research Process

- Brainstorming

- Explore Google This link opens in a new window

- Explore Web Resources

- Explore Background Information

- Explore Books

- Explore Scholarly Articles

- Narrowing a Topic

- Primary and Secondary Resources

- Academic, Popular & Trade Publications

- Scholarly and Peer-Reviewed Journals

- Grey Literature

- Clinical Trials

- Evidence Based Treatment

- Scholarly Research

- Database Research Log

- Search Limits

- Keyword Searching

- Boolean Operators

- Phrase Searching

- Truncation & Wildcard Symbols

- Proximity Searching

- Field Codes

- Subject Terms and Database Thesauri

- Reading a Scientific Article

- Website Evaluation

- Article Keywords and Subject Terms

- Cited References

- Citing Articles

- Related Results

- Search Within Publication

- Database Alerts & RSS Feeds

- Personal Database Accounts

- Persistent URLs

- Literature Gap and Future Research

- Web of Knowledge

- Annual Reviews

- Systematic Reviews & Meta-Analyses

- Finding Seminal Works

- Exhausting the Literature

- Finding Dissertations

- Researching Theoretical Frameworks

- Research Methodology & Design

- Tests and Measurements

- Organizing Research & Citations This link opens in a new window

- Scholarly Publication

- Learn the Library This link opens in a new window

Library Basic Training: Resources for Doctoral Success

- Library Basic Training: Resources for Doctoral Success Reviews the most important resources for your dissertation research. Learn how to search for scholarly articles and dissertations, place Interlibrary Loan requests, find information about research methodology and design, use Google Scholar, and more.

NU Dissertation Center

If you are looking for a document in the Dissertation Center or Applied Doctoral Center and can't find it please contact your Chair or The Center for Teaching and Learning at [email protected]

- NCU Dissertation Center Find valuable resources and support materials to help you through your doctoral journey.

- Applied Doctoral Center Collection of resources to support students in completing their project/dissertation-in-practice as part of the Applied Doctoral Experience (ADE).

Dissertation Research

Dissertation topics are a special subset of research topics. All of the previously mentioned techniques can, and should, be utilized to locate potential dissertation topics, but there are also some special considerations to keep in mind when choosing a dissertation topic.

Dissertation topics should interesting, feasible, relevant, and worthy. The criterion of feasibility is especially important when choosing a dissertation topic. You don’t want to settle on a topic and then find out that the study you were imagining can’t be done, or the survey or assessment instrument you need can’t be used. You also want to make sure that you select a topic that will allow you to be an objective researcher. If you select a topic that you have worked closely on for many years, make sure you are still open to new information, even if that information runs counter what you believe to be true about the topic. To learn more about feasibility, see the Center for Teaching & Learning's Feasibility Checklist .

It is very important to think about these considerations beforehand so that you don’t get stuck during the dissertation process. Here are some considerations to keep in mind when choosing a dissertation topic:

- Access to the primary literature relating to your topic

- Access to grey literature relating to your topic

- Access to the surveys and assessment instruments that you will need

- Access to the study group to conduct your study

- IRB approval for your study

- Access to equipment for your study, if needed

Note that published surveys and assessment instruments are generally NOT free. Due to copyright laws you will more than likely need to purchase the survey from the publisher in order to gain permissions to use in your own study. Unpublished surveys and assessments (usually found in the appendices of articles) may be freely available, but you will need to contact the author(s) to gain permission to use the survey in your research.

Looking at previously published dissertations is a great way to gauge the level of research and involvement that is generally expected at the dissertation level. Previously published dissertations can also be good sources of inspiration for your own dissertation study. Similar to scholarly articles, many dissertations will suggest areas of future research. Paying attention to those suggestions can provide valuable ideas and clues for your own dissertation topic. Note that dissertations are not considered to be peer-reviewed documents, so carefully review and evaluate the information presented in them.

The literature review section in a dissertation contains a wealth of information. Not only can the literature review provide topic ideas by showing some of the major research that has been done on a topic, but it can also help you evaluate any topics that you are tentatively considering. From your examination of literature reviews can you determine if your research idea has already been completed? Has the theory that validates your study been disproved by new dissertation research? Is your research idea still relevant to the current state of the discipline? Literature reviews can help you answer these questions by providing a compact and summative description of a particular research area.