- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- French Abstracts

- Portuguese Abstracts

- Spanish Abstracts

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About International Journal for Quality in Health Care

- About the International Society for Quality in Health Care

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Contact ISQua

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Primacy of the research question, structure of the paper, writing a research article: advice to beginners.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Thomas V. Perneger, Patricia M. Hudelson, Writing a research article: advice to beginners, International Journal for Quality in Health Care , Volume 16, Issue 3, June 2004, Pages 191–192, https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzh053

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Writing research papers does not come naturally to most of us. The typical research paper is a highly codified rhetorical form [ 1 , 2 ]. Knowledge of the rules—some explicit, others implied—goes a long way toward writing a paper that will get accepted in a peer-reviewed journal.

A good research paper addresses a specific research question. The research question—or study objective or main research hypothesis—is the central organizing principle of the paper. Whatever relates to the research question belongs in the paper; the rest doesn’t. This is perhaps obvious when the paper reports on a well planned research project. However, in applied domains such as quality improvement, some papers are written based on projects that were undertaken for operational reasons, and not with the primary aim of producing new knowledge. In such cases, authors should define the main research question a posteriori and design the paper around it.

Generally, only one main research question should be addressed in a paper (secondary but related questions are allowed). If a project allows you to explore several distinct research questions, write several papers. For instance, if you measured the impact of obtaining written consent on patient satisfaction at a specialized clinic using a newly developed questionnaire, you may want to write one paper on the questionnaire development and validation, and another on the impact of the intervention. The idea is not to split results into ‘least publishable units’, a practice that is rightly decried, but rather into ‘optimally publishable units’.

What is a good research question? The key attributes are: (i) specificity; (ii) originality or novelty; and (iii) general relevance to a broad scientific community. The research question should be precise and not merely identify a general area of inquiry. It can often (but not always) be expressed in terms of a possible association between X and Y in a population Z, for example ‘we examined whether providing patients about to be discharged from the hospital with written information about their medications would improve their compliance with the treatment 1 month later’. A study does not necessarily have to break completely new ground, but it should extend previous knowledge in a useful way, or alternatively refute existing knowledge. Finally, the question should be of interest to others who work in the same scientific area. The latter requirement is more challenging for those who work in applied science than for basic scientists. While it may safely be assumed that the human genome is the same worldwide, whether the results of a local quality improvement project have wider relevance requires careful consideration and argument.

Once the research question is clearly defined, writing the paper becomes considerably easier. The paper will ask the question, then answer it. The key to successful scientific writing is getting the structure of the paper right. The basic structure of a typical research paper is the sequence of Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion (sometimes abbreviated as IMRAD). Each section addresses a different objective. The authors state: (i) the problem they intend to address—in other terms, the research question—in the Introduction; (ii) what they did to answer the question in the Methods section; (iii) what they observed in the Results section; and (iv) what they think the results mean in the Discussion.

In turn, each basic section addresses several topics, and may be divided into subsections (Table 1 ). In the Introduction, the authors should explain the rationale and background to the study. What is the research question, and why is it important to ask it? While it is neither necessary nor desirable to provide a full-blown review of the literature as a prelude to the study, it is helpful to situate the study within some larger field of enquiry. The research question should always be spelled out, and not merely left for the reader to guess.

Typical structure of a research paper

The Methods section should provide the readers with sufficient detail about the study methods to be able to reproduce the study if so desired. Thus, this section should be specific, concrete, technical, and fairly detailed. The study setting, the sampling strategy used, instruments, data collection methods, and analysis strategies should be described. In the case of qualitative research studies, it is also useful to tell the reader which research tradition the study utilizes and to link the choice of methodological strategies with the research goals [ 3 ].

The Results section is typically fairly straightforward and factual. All results that relate to the research question should be given in detail, including simple counts and percentages. Resist the temptation to demonstrate analytic ability and the richness of the dataset by providing numerous tables of non-essential results.

The Discussion section allows the most freedom. This is why the Discussion is the most difficult to write, and is often the weakest part of a paper. Structured Discussion sections have been proposed by some journal editors [ 4 ]. While strict adherence to such rules may not be necessary, following a plan such as that proposed in Table 1 may help the novice writer stay on track.

References should be used wisely. Key assertions should be referenced, as well as the methods and instruments used. However, unless the paper is a comprehensive review of a topic, there is no need to be exhaustive. Also, references to unpublished work, to documents in the grey literature (technical reports), or to any source that the reader will have difficulty finding or understanding should be avoided.

Having the structure of the paper in place is a good start. However, there are many details that have to be attended to while writing. An obvious recommendation is to read, and follow, the instructions to authors published by the journal (typically found on the journal’s website). Another concerns non-native writers of English: do have a native speaker edit the manuscript. A paper usually goes through several drafts before it is submitted. When revising a paper, it is useful to keep an eye out for the most common mistakes (Table 2 ). If you avoid all those, your paper should be in good shape.

Common mistakes seen in manuscripts submitted to this journal

Huth EJ . How to Write and Publish Papers in the Medical Sciences , 2nd edition. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 1990 .

Browner WS . Publishing and Presenting Clinical Research . Baltimore, MD: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 1999 .

Devers KJ , Frankel RM. Getting qualitative research published. Educ Health 2001 ; 14 : 109 –117.

Docherty M , Smith R. The case for structuring the discussion of scientific papers. Br Med J 1999 ; 318 : 1224 –1225.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1464-3677

- Print ISSN 1353-4505

- Copyright © 2024 International Society for Quality in Health Care and Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Sports Phys Ther

- v.7(5); 2012 Oct

HOW TO WRITE A SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

Barbara j. hoogenboom.

1 Grand Valley State University, Grand Rapids, MI, USA

Robert C. Manske

2 University of Wichita, Wichita, KS, USA

Successful production of a written product for submission to a peer‐reviewed scientific journal requires substantial effort. Such an effort can be maximized by following a few simple suggestions when composing/creating the product for submission. By following some suggested guidelines and avoiding common errors, the process can be streamlined and success realized for even beginning/novice authors as they negotiate the publication process. The purpose of this invited commentary is to offer practical suggestions for achieving success when writing and submitting manuscripts to The International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy and other professional journals.

INTRODUCTION

“The whole of science is nothing more than a refinement of everyday thinking” Albert Einstein

Conducting scientific and clinical research is only the beginning of the scholarship of discovery. In order for the results of research to be accessible to other professionals and have a potential effect on the greater scientific community, it must be written and published. Most clinical and scientific discovery is published in peer‐reviewed journals, which are those that utilize a process by which an author's peers, or experts in the content area, evaluate the manuscript. Following this review the manuscript is recommended for publication, revision or rejection. It is the rigor of this review process that makes scientific journals the primary source of new information that impacts clinical decision‐making and practice. 1 , 2

The task of writing a scientific paper and submitting it to a journal for publication is a time‐consuming and often daunting task. 3 , 4 Barriers to effective writing include lack of experience, poor writing habits, writing anxiety, unfamiliarity with the requirements of scholarly writing, lack of confidence in writing ability, fear of failure, and resistance to feedback. 5 However, the very process of writing can be a helpful tool for promoting the process of scientific thinking, 6 , 7 and effective writing skills allow professionals to participate in broader scientific conversations. Furthermore, peer review manuscript publication systems requiring these technical writing skills can be developed and improved with practice. 8 Having an understanding of the process and structure used to produce a peer‐reviewed publication will surely improve the likelihood that a submitted manuscript will result in a successful publication.

Clear communication of the findings of research is essential to the growth and development of science 3 and professional practice. The culmination of the publication process provides not only satisfaction for the researcher and protection of intellectual property, but also the important function of dissemination of research results, new ideas, and alternate thought; which ultimately facilitates scholarly discourse. In short, publication of scientific papers is one way to advance evidence‐based practice in many disciplines, including sports physical therapy. Failure to publish important findings significantly diminishes the potential impact that those findings may have on clinical practice. 9

BASICS OF MANUSCRIPT PREPARATION & GENERAL WRITING TIPS

To begin it might be interesting to learn why reviewers accept manuscripts! Reviewers consider the following five criteria to be the most important in decisions about whether to accept manuscripts for publication: 1) the importance, timeliness, relevance, and prevalence of the problem addressed; 2) the quality of the writing style (i.e., that it is well‐written, clear, straightforward, easy to follow, and logical); 3) the study design applied (i.e., that the design was appropriate, rigorous, and comprehensive); 4) the degree to which the literature review was thoughtful, focused, and up‐to‐date; and 5) the use of a sufficiently large sample. 10 For these statements to be true there are also reasons that reviewers reject manuscripts. The following are the top five reasons for rejecting papers: 1) inappropriate, incomplete, or insufficiently described statistics; 2) over‐interpretation of results; 3) use of inappropriate, suboptimal, or insufficiently described populations or instruments; 4) small or biased samples; and 5) text that is poorly written or difficult to follow. 10 , 11 With these reasons for acceptance or rejection in mind, it is time to review basics and general writing tips to be used when performing manuscript preparation.

“Begin with the end in mind” . When you begin writing about your research, begin with a specific target journal in mind. 12 Every scientific journal should have specific lists of manuscript categories that are preferred for their readership. The IJSPT seeks to provide readership with current information to enhance the practice of sports physical therapy. Therefore the manuscript categories accepted by IJSPT include: Original research; Systematic reviews of literature; Clinical commentary and Current concept reviews; Case reports; Clinical suggestions and unique practice techniques; and Technical notes. Once a decision has been made to write a manuscript, compose an outline that complies with the requirements of the target submission journal and has each of the suggested sections. This means carefully checking the submission criteria and preparing your paper in the exact format of the journal to which you intend to submit. Be thoughtful about the distinction between content (what you are reporting) and structure (where it goes in the manuscript). Poor placement of content confuses the reader (reviewer) and may cause misinterpretation of content. 3 , 5

It may be helpful to follow the IMRaD format for writing scientific manuscripts. This acronym stands for the sections contained within the article: Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion. Each of these areas of the manuscript will be addressed in this commentary.

Many accomplished authors write their results first, followed by an introduction and discussion, in an attempt to “stay true” to their results and not stray into additional areas. Typically the last two portions to be written are the conclusion and the abstract.

The ability to accurately describe ideas, protocols/procedures, and outcomes are the pillars of scientific writing . Accurate and clear expression of your thoughts and research information should be the primary goal of scientific writing. 12 Remember that accuracy and clarity are even more important when trying to get complicated ideas across. Contain your literature review, ideas, and discussions to your topic, theme, model, review, commentary, or case. Avoid vague terminology and too much prose. Use short rather than long sentences. If jargon has to be utilized keep it to a minimum and explain the terms you do use clearly. 13

Write with a measure of formality, using scientific language and avoiding conjunctions, slang, and discipline or regionally specific nomenclature or terms (e.g. exercise nicknames). For example, replace the term “Monster walks” with “closed‐chain hip abduction with elastic resistance around the thighs”. You may later refer to the exercise as “also known as Monster walks” if you desire.

Avoid first person language and instead write using third person language. Some journals do not ascribe to this requirement, and allow first person references, however, IJSPT prefers use of third person. For example, replace “We determined that…” with “The authors determined that….”.

For novice writers, it is really helpful to seek a reading mentor that will help you pre‐read your submission. Problems such as improper use of grammar, tense, and spelling are often a cause of rejection by reviewers. Despite the content of the study these easily fixed errors suggest that the authors created the manuscript with less thought leading reviewers to think that the manuscript may also potentially have erroneous findings as well. A review from a second set of trained eyes will often catch these errors missed by the original authors. If English is not your first language, the editorial staff at IJSPT suggests that you consult with someone with the relevant expertise to give you guidance on English writing conventions, verb tense, and grammar. Excellent writing in English is hard, even for those of us for whom it is our first language!

Use figures and graphics to your advantage . ‐ Consider the use of graphic/figure representation of data and important procedures or exercises. Tables should be able to stand alone and be completely understandable at a quick glance. Understanding a table should not require careful review of the manuscript! Figures dramatically enhance the graphic appeal of a scientific paper. Many formats for graphic presentation are acceptable, including graphs, charts, tables, and pictures or videos. Photographs should be clear, free of clutter or extraneous background distractions and be taken with models wearing simple clothing. Color photographs are preferred. Digital figures (Scans or existing files as well as new photographs) must be at least 300dpi. All photographs should be provided as separate files (jpeg or tif preferred) and not be embedded in the paper. Quality and clarity of figures are essential for reproduction purposes and should be considered before taking images for the manuscript.

A video of an exercise or procedure speaks a thousand words. Please consider using short video clips as descriptive additions to your paper. They will be placed on the IJSPT website and accompany your paper. The video clips must be submitted in MPEG‐1, MPEG‐2, Quicktime (.mov), or Audio/Video Interface (.avi) formats. Maximum cumulative length of videos is 5 minutes. Each video segment may not exceed 50 MB, and each video clip must be saved as a separate file and clearly identified. Formulate descriptive figure/video and Table/chart/graph titles and place them on a figure legend document. Carefully consider placement of, naming of, and location of figures. It makes the job of the editors much easier!

Avoid Plagiarism and inadvertent lack of citations. Finally, use citations to your benefit. Cite frequently in order to avoid any plagiarism. The bottom line: If it is not your original idea, give credit where credit is due . When using direct quotations, provide not only the number of the citation, but the page where the quote was found. All citations should appear in text as a superscripted number followed by punctuation. It is the authors' responsibility to fully ensure all references are cited in completed form, in an accurate location. Please carefully follow the instructions for citations and check that all references in your reference list are cited in the paper and that all citations in the paper appear correctly in the reference list. Please go to IJSPT submission guidelines for full information on the format for citations.

Sometimes written as an afterthought, the abstract is of extreme importance as in many instances this section is what is initially previewed by readership to determine if the remainder of the article is worth reading. This is the authors opportunity to draw the reader into the study and entice them to read the rest of the article. The abstract is a summary of the article or study written in 3 rd person allowing the readers to get a quick glance of what the contents of the article include. Writing an abstract is rather challenging as being brief, accurate and concise are requisite. The headings and structure for an abstract are usually provided in the instructions for authors. In some instances, the abstract may change slightly pending content revisions required during the peer review process. Therefore it often works well to complete this portion of the manuscript last. Remember the abstract should be able to stand alone and should be as succinct as possible. 14

Introduction and Review of Literature

The introduction is one of the more difficult portions of the manuscript to write. Past studies are used to set the stage or provide the reader with information regarding the necessity of the represented project. For an introduction to work properly, the reader must feel that the research question is clear, concise, and worthy of study.

A competent introduction should include at least four key concepts: 1) significance of the topic, 2) the information gap in the available literature associated with the topic, 3) a literature review in support of the key questions, 4) subsequently developed purposes/objectives and hypotheses. 9

When constructing a review of the literature, be attentive to “sticking” or “staying true” to your topic at hand. Don't reach or include too broad of a literature review. For example, do not include extraneous information about performance or prevention if your research does not actually address those things. The literature review of a scientific paper is not an exhaustive review of all available knowledge in a given field of study. That type of thorough review should be left to review articles or textbook chapters. Throughout the introduction (and later in the discussion!) remind yourself that a paper, existing evidence, or results of a paper cannot draw conclusions, demonstrate, describe, or make judgments, only PEOPLE (authors) can. “The evidence demonstrates that” should be stated, “Smith and Jones, demonstrated that….”

Conclude your introduction with a solid statement of your purpose(s) and your hypothesis(es), as appropriate. The purpose and objectives should clearly relate to the information gap associated with the given manuscript topic discussed earlier in the introduction section. This may seem repetitive, but it actually is helpful to ensure the reader clearly sees the evolution, importance, and critical aspects of the study at hand See Table 1 for examples of well‐stated purposes.

Examples of well-stated purposes by submission type.

The methods section should clearly describe the specific design of the study and provide clear and concise description of the procedures that were performed. The purpose of sufficient detail in the methods section is so that an appropriately trained person would be able to replicate your experiments. 15 There should be complete transparency when describing the study. To assist in writing and manuscript preparation there are several checklists or guidelines that are available on the IJSPT website. The CONSORT guidelines can be used when developing and reporting a randomized controlled trial. 16 The STARD checklist was developed for designing a diagnostic accuracy study. 17 The PRISMA checklist was developed for use when performing a meta‐analyses or systematic review. 18 A clear methods section should contain the following information: 1) the population and equipment used in the study, 2) how the population and equipment were prepared and what was done during the study, 3) the protocol used, 4) the outcomes and how they were measured, 5) the methods used for data analysis. Initially a brief paragraph should explain the overall procedures and study design. Within this first paragraph there is generally a description of inclusion and exclusion criteria which help the reader understand the population used. Paragraphs that follow should describe in more detail the procedures followed for the study. A clear description of how data was gathered is also helpful. For example were data gathered prospectively or retrospectively? Who if anyone was blinded, and where and when was the actual data collected?

Although it is a good idea for the authors to have justification and a rationale for their procedures, these should be saved for inclusion into the discussion section, not to be discussed in the methods section. However, occasionally studies supporting components of the methods section such as reliability of tests, or validation of outcome measures may be included in the methods section.

The final portion of the methods section will include the statistical methods used to analyze the data. 19 This does not mean that the actual results should be discussed in the methods section, as they have an entire section of their own!

Most scientific journals support the need for all projects involving humans or animals to have up‐to‐date documentation of ethical approval. 20 The methods section should include a clear statement that the researchers have obtained approval from an appropriate institutional review board.

Results, Discussion, and Conclusions

In most journals the results section is separate from the discussion section. It is important that you clearly distinguish your results from your discussion. The results section should describe the results only. The discussion section should put those results into a broader context. Report your results neutrally, as you “found them”. Again, be thoughtful about content and structure. Think carefully about where content is placed in the overall structure of your paper. It is not appropriate to bring up additional results, not discussed in the results section, in the discussion. All results must first be described/presented and then discussed. Thus, the discussion should not simply be a repeat of the results section. Carefully discuss where your information is similar or different from other published evidence and why this might be so. What was different in methods or analysis, what was similar?

As previously stated, stick to your topic at hand, and do not overstretch your discussion! One of the major pitfalls in writing the discussion section is overstating the significance of your findings 4 or making very strong statements. For example, it is better to say: “Findings of the current study support….” or “these findings suggest…” than, “Findings of the current study prove that…” or “this means that….”. Maintain a sense of humbleness, as nothing is without question in the outcomes of any type of research, in any discipline! Use words like “possibly”, “likely” or “suggests” to soften findings. 12

Do not discuss extraneous ideas, concepts, or information not covered by your topic/paper/commentary. Be sure to carefully address all relevant results, not just the statistically significant ones or the ones that support your hypotheses. When you must resort to speculation or opinion, be certain to state that up front using phrases such as “we therefore speculate” or “in the authors' opinion”.

Remember, just as in the introduction and literature review, evidence or results cannot draw conclusions, just as previously stated, only people, scientists, researchers, and authors can!

Finish with a concise, 3‐5 sentence conclusion paragraph. This is not just a restatement of your results, rather is comprised of some final, summative statements that reflect the flow and outcomes of the entire paper. Do not include speculative statements or additional material; however, based upon your findings a statement about potential changes in clinical practice or future research opportunities can be provided here.

CONCLUSIONS

Writing for publication can be a challenging yet satisfying endeavor. The ability to examine, relate, and interlink evidence, as well as to provide a peer‐reviewed, disseminated product of your research labors can be rewarding. A few suggestions have been offered in this commentary that may assist the novice or the developing writer to attempt, polish, and perfect their approach to scholarly writing.

Research Paper Guide

Research Paper Example

Research Paper Examples - Free Sample Papers for Different Formats!

People also read

Research Paper Writing - A Step by Step Guide

Guide to Creating Effective Research Paper Outline

Interesting Research Paper Topics for 2024

Research Proposal Writing - A Step-by-Step Guide

How to Start a Research Paper - 7 Easy Steps

How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper - A Step by Step Guide

Writing a Literature Review For a Research Paper - A Comprehensive Guide

Qualitative Research - Methods, Types, and Examples

8 Types of Qualitative Research - Overview & Examples

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research - Learning the Basics

200+ Engaging Psychology Research Paper Topics for Students in 2024

Learn How to Write a Hypothesis in a Research Paper: Examples and Tips!

20+ Types of Research With Examples - A Detailed Guide

Understanding Quantitative Research - Types & Data Collection Techniques

230+ Sociology Research Topics & Ideas for Students

How to Cite a Research Paper - A Complete Guide

Excellent History Research Paper Topics- 300+ Ideas

A Guide on Writing the Method Section of a Research Paper - Examples & Tips

How To Write an Introduction Paragraph For a Research Paper: Learn with Examples

Crafting a Winning Research Paper Title: A Complete Guide

Writing a Research Paper Conclusion - Step-by-Step Guide

Writing a Thesis For a Research Paper - A Comprehensive Guide

How To Write A Discussion For A Research Paper | Examples & Tips

How To Write The Results Section of A Research Paper | Steps & Examples

Writing a Problem Statement for a Research Paper - A Comprehensive Guide

Finding Sources For a Research Paper: A Complete Guide

A Guide on How to Edit a Research Paper

200+ Ethical Research Paper Topics to Begin With (2024)

300+ Controversial Research Paper Topics & Ideas - 2024 Edition

150+ Argumentative Research Paper Topics For You - 2024

How to Write a Research Methodology for a Research Paper

Crafting a comprehensive research paper can be daunting. Understanding diverse citation styles and various subject areas presents a challenge for many.

Without clear examples, students often feel lost and overwhelmed, unsure of how to start or which style fits their subject.

Explore our collection of expertly written research paper examples. We’ve covered various citation styles and a diverse range of subjects.

So, read on!

- 1. Research Paper Example for Different Formats

- 2. Examples for Different Research Paper Parts

- 3. Research Paper Examples for Different Fields

- 4. Research Paper Example Outline

Research Paper Example for Different Formats

Following a specific formatting style is essential while writing a research paper . Knowing the conventions and guidelines for each format can help you in creating a perfect paper. Here we have gathered examples of research paper for most commonly applied citation styles :

Social Media and Social Media Marketing: A Literature Review

APA Research Paper Example

APA (American Psychological Association) style is commonly used in social sciences, psychology, and education. This format is recognized for its clear and concise writing, emphasis on proper citations, and orderly presentation of ideas.

Here are some research paper examples in APA style:

Research Paper Example APA 7th Edition

Research Paper Example MLA

MLA (Modern Language Association) style is frequently employed in humanities disciplines, including literature, languages, and cultural studies. An MLA research paper might explore literature analysis, linguistic studies, or historical research within the humanities.

Here is an example:

Found Voices: Carl Sagan

Research Paper Example Chicago

Chicago style is utilized in various fields like history, arts, and social sciences. Research papers in Chicago style could delve into historical events, artistic analyses, or social science inquiries.

Here is a research paper formatted in Chicago style:

Chicago Research Paper Sample

Research Paper Example Harvard

Harvard style is widely used in business, management, and some social sciences. Research papers in Harvard style might address business strategies, case studies, or social policies.

View this sample Harvard style paper here:

Harvard Research Paper Sample

Examples for Different Research Paper Parts

A research paper has different parts. Each part is important for the overall success of the paper. Chapters in a research paper must be written correctly, using a certain format and structure.

The following are examples of how different sections of the research paper can be written.

Research Proposal

The research proposal acts as a detailed plan or roadmap for your study, outlining the focus of your research and its significance. It's essential as it not only guides your research but also persuades others about the value of your study.

Example of Research Proposal

An abstract serves as a concise overview of your entire research paper. It provides a quick insight into the main elements of your study. It summarizes your research's purpose, methods, findings, and conclusions in a brief format.

Research Paper Example Abstract

Literature Review

A literature review summarizes the existing research on your study's topic, showcasing what has already been explored. This section adds credibility to your own research by analyzing and summarizing prior studies related to your topic.

Literature Review Research Paper Example

Methodology

The methodology section functions as a detailed explanation of how you conducted your research. This part covers the tools, techniques, and steps used to collect and analyze data for your study.

Methods Section of Research Paper Example

How to Write the Methods Section of a Research Paper

The conclusion summarizes your findings, their significance and the impact of your research. This section outlines the key takeaways and the broader implications of your study's results.

Research Paper Conclusion Example

Research Paper Examples for Different Fields

Research papers can be about any subject that needs a detailed study. The following examples show research papers for different subjects.

History Research Paper Sample

Preparing a history research paper involves investigating and presenting information about past events. This may include exploring perspectives, analyzing sources, and constructing a narrative that explains the significance of historical events.

View this history research paper sample:

Many Faces of Generalissimo Fransisco Franco

Sociology Research Paper Sample

In sociology research, statistics and data are harnessed to explore societal issues within a particular region or group. These findings are thoroughly analyzed to gain an understanding of the structure and dynamics present within these communities.

Here is a sample:

A Descriptive Statistical Analysis within the State of Virginia

Science Fair Research Paper Sample

A science research paper involves explaining a scientific experiment or project. It includes outlining the purpose, procedures, observations, and results of the experiment in a clear, logical manner.

Here are some examples:

Science Fair Paper Format

What Do I Need To Do For The Science Fair?

Psychology Research Paper Sample

Writing a psychology research paper involves studying human behavior and mental processes. This process includes conducting experiments, gathering data, and analyzing results to understand the human mind, emotions, and behavior.

Here is an example psychology paper:

The Effects of Food Deprivation on Concentration and Perseverance

Art History Research Paper Sample

Studying art history includes examining artworks, understanding their historical context, and learning about the artists. This helps analyze and interpret how art has evolved over various periods and regions.

Check out this sample paper analyzing European art and impacts:

European Art History: A Primer

Research Paper Example Outline

Before you plan on writing a well-researched paper, make a rough draft. An outline can be a great help when it comes to organizing vast amounts of research material for your paper.

Here is an outline of a research paper example:

Here is a downloadable sample of a standard research paper outline:

Research Paper Outline

Want to create the perfect outline for your paper? Check out this in-depth guide on creating a research paper outline for a structured paper!

Good Research Paper Examples for Students

Here are some more samples of research paper for students to learn from:

Fiscal Research Center - Action Plan

Qualitative Research Paper Example

Research Paper Example Introduction

How to Write a Research Paper Example

Research Paper Example for High School

Now that you have explored the research paper examples, you can start working on your research project. Hopefully, these examples will help you understand the writing process for a research paper.

If you're facing challenges with your writing requirements, you can hire our essay writing service .

Our team is experienced in delivering perfectly formatted, 100% original research papers. So, whether you need help with a part of research or an entire paper, our experts are here to deliver.

So, why miss out? Place your ‘ write my research paper ’ request today and get a top-quality research paper!

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Nova Allison is a Digital Content Strategist with over eight years of experience. Nova has also worked as a technical and scientific writer. She is majorly involved in developing and reviewing online content plans that engage and resonate with audiences. Nova has a passion for writing that engages and informs her readers.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

Psychological safety and the critical role of leadership development

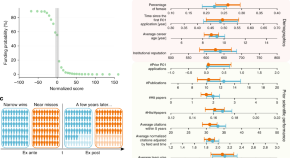

When employees feel comfortable asking for help, sharing suggestions informally, or challenging the status quo without fear of negative social consequences, organizations are more likely to innovate quickly , unlock the benefits of diversity , and adapt well to change —all capabilities that have only grown in importance during the COVID-19 crisis. 1 Jonathan Emmett, Gunnar Schrah, Matt Schrimper, and Alexandra Wood, “ COVID-19 and the employee experience: How leaders can seize the moment ,” June 2020, McKinsey.com; Tera Allas, David Chinn, Pal Erik Sjatil, and Whitney Zimmerman, “ Well-being in Europe: Addressing the high cost of COVID-19 on life satisfaction ,” June 2020, McKinsey.com. Yet a McKinsey Global Survey conducted during the pandemic confirms that only a handful of business leaders often demonstrate the positive behaviors that can instill this climate, termed psychological safety , in their workforce. 2 The online survey was in the field from May 14–29, 2020, and garnered responses from 1,574 participants representing the full range of regions, industries, company sizes, functional specialties, and tenures. Of those respondents, we analyzed the results of 1,223 participants who said they were a member of a team that they did not lead, where a team is defined as two or more people who work together to achieve a common goal. CEOs were included in the findings if they said that a) their organization had a board of directors and b) they were not the board’s chair, so that they could think of their board when asked questions about their team.

As considerable prior research shows, psychological safety is a precursor to adaptive, innovative performance—which is needed in today’s rapidly changing environment—at the individual, team, and organization levels. 3 Amy C. Edmondson, The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth, first edition, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, November 2018; Shirley A. Ashauer and Therese Macan, “How can leaders foster team learning? Effects of leader-assigned mastery and performance goals and psychological safety,” Journal of Psychology, November–December 2013, Volume 147, Number 6, pp. 541–61, tandfonline.com; Anne Boon et al., “Team learning beliefs and behaviours in response teams,” European Journal of Training and Development, May 2013, Volume 37, Number 4, pp. 357–79, emerald.com; Daphna Brueller and Abraham Carmeli, “Linking capacities of high-quality relationships to team learning and performance in service organizations,” Human Resource Management, July–August 2011, Volume 50, Number 4, pp. 455–77, wileyonlinelibrary.com; M. Lance Frazier et al., “Psychological safety: A meta-analytic review and extension,” Personnel Psychology, February 2017, Volume 70, Number 1, pp. 113–65, onlinelibrary.wiley.com; Nikos Bozionelos and Konstantinos C. Kostopoulos, “Team exploratory and exploitative learning: Psychological safety, task conflict, and team performance,” Group & Organization Management, June 2011, Volume 36, Number 3, pp. 385–415, journals.sagepub.com; Rosario Ortega et al., “The emotional impact of bullying and cyberbullying on victims: A European cross-national study,” Aggressive Behavior, September–October 2012, Volume 38, Issue 5, pp. 342–56, onlinelibrary.wiley.com; Corinne Post, “Deep-level team composition and innovation: The mediating roles of psychological safety and cooperative learning,” Group & Organizational Management, October 2012, Volume 37, Number 5, pp. 555–88, journals.sagepub.com; Charles Duhigg, “What Google learned from its quest to build the perfect team,” New York Times, February 25, 2016, nytimes.com. Amy Edmondson’s 1999 research previously found—and our survey findings confirm—that higher psychological safety predicts a higher degree of boundary-spanning behavior, which is accessing and coordinating with those outside of an individual’s team to accomplish goals. For example, successfully creating a “ network of teams ”—an agile organizational structure that empowers teams to tackle problems quickly by operating outside of bureaucratic or siloed structures—requires a strong degree of psychological safety.

Fortunately, our newest research suggests how organizations can foster psychological safety. Doing so depends on leaders at all levels learning and demonstrating specific leadership behaviors that help their employees thrive. Investing in and scaling up leadership-development programs can equip leaders to embody these behaviors and consequently cultivate psychological safety across the organization.

A recipe for leadership that promotes psychological safety

Leaders can build psychological safety by creating the right climate, mindsets, and behaviors within their teams. In our experience, those who do this best act as catalysts, empowering and enabling other leaders on the team—even those with no formal authority—to help cultivate psychological safety by role modeling and reinforcing the behaviors they expect from the rest of the team.

Our research finds that a positive team climate—in which team members value one another’s contributions, care about one another’s well-being, and have input into how the team carries out its work—is the most important driver of a team’s psychological safety. 4 Past research by Frazier et al. (2017) found three categories to be the main drivers of psychological safety: positive leader relations, work-design characteristics, and a positive team climate. We conducted multiple regression with relative-importance analysis to understand which category matters most, and our results show that a positive team climate has a significantly stronger direct effect on psychological safety than the other two. Based on these results, we tested a structural-equation model (SEM) in which the frequency with which team leaders displayed four leadership behaviors predicted psychological safety both directly and indirectly via positive team climate. Exploratory analyses were conducted to determine whether the effect of the leadership behaviors affected psychological safety at different levels of team climate. By setting the tone for the team climate through their own actions, team leaders have the strongest influence on a team’s psychological safety. Moreover, creating a positive team climate can pay additional dividends during a time of disruption. Our research finds that a positive team climate has a stronger effect on psychological safety in teams that experienced a greater degree of change in working remotely than in those that experienced less change during the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet just 43 percent of all respondents report a positive climate within their team.

Positive team climate is the most important driver of psychological safety and most likely to occur when leaders demonstrate supportive, consultative behaviors, then begin to challenge their teams.

During the pandemic, we have seen an accelerated shift away from the traditional command-and-control leadership style known as authoritative leadership, one of the four well-established styles of leadership behavior we examined to understand which ones encourage a positive team climate and psychological safety . The survey finds that team leaders’ authoritative-leadership behaviors are detrimental to psychological safety, while consultative- and supportive-leadership behaviors promote psychological safety.

The results also suggest that leaders can further enhance psychological safety by ensuring a positive team climate (Exhibit 1). Both consultative and supportive leadership help create a positive team climate, though to varying degrees and through different types of behaviors.

With consultative leadership, which has a direct and indirect effect on psychological safety, leaders consult their team members, solicit input, and consider the team’s views on issues that affect them. 5 The standardized regression coefficient between consultative leadership and psychological safety was 0.54. The survey measured consultative-leadership behaviors by asking respondents how frequently their team leaders demonstrate the following behaviors: ask the opinions of others before making important decisions, give team members the autonomy to make their own decisions, and try to achieve team consensus on decisions. Supportive leadership has an indirect but still significant effect on psychological safety by helping to create a positive team climate; it involves leaders demonstrating concern and support for team members not only as employees but also as individuals. 6 The survey measured supportive leadership behaviors by asking respondents how frequently their team leaders demonstrate the following behaviors: create a sense of teamwork and mutual support within the team, and demonstrate concern for the welfare of team members. These behaviors also can encourage team members to support one another.

Another set of leadership behaviors can sometimes strengthen psychological safety—but only when a positive team climate is in place. This set of behaviors, known as challenging leadership, encourages employees to do more than they initially think they can. A challenging leader asks team members to reexamine assumptions about their work and how it can be performed in order to exceed expectations and fulfill their potential. Challenging leadership has previously been linked with employees expressing creativity, feeling empowered to make work-related changes, and seeking to learn and improve. 7 Giles Hirst, Helen Shipton, and Qin Zhou, “Context matters: Combined influence of participation and intellectual stimulation on the promotion focus–employee creative relationship,” Journal of Organizational Behavior, October 2012, Volume 33, Number 7, pp. 894–909, onlinelibrary.wiley.com; Le Cong Thuan, “Motivating follower creativity by offering intellectual stimulation,” International Journal of Organizational Analysis, December 2019, Volume 28, Number 4, pp. 817–29, emerald.com; Jie Li et al., “Not all transformational leadership behaviors are equal: The impact of followers’ identification with leader and modernity on taking charge,” Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, August 2017, Volume 24, Number 3, pp. 318–34, journals.sagepub.com; Susana Llorens-Gumbau, Marisa Salanova Soria, and Israel Sánchez-Cardona, “Leadership intellectual stimulation and team learning: The mediating role of team positive affect,” Universitas Psychologica, March 2018, Volume 17, Number 1, pp. 1–16, revistas.javeriana.edu.co. However, the survey findings show that the highest likelihood of psychological safety occurs when a team leader first creates a positive team climate, through frequent supportive and consultative actions, and then challenges their team; without a foundation of positive climate, challenging behaviors have no significant effect. And employees’ experiences look very different depending on how their leaders behave, according to Amy Edmondson, the Novartis Professor of Leadership and Management at Harvard Business School (interactive).

What’s more, the survey results show that a climate conducive to psychological safety starts at the very top of an organization. We sought to understand the effects of senior-leader behavior on employees’ sense of safety and found that senior leaders can help create a culture of inclusiveness that promotes positive leadership behaviors throughout an organization by role-modeling these behaviors themselves. Team leaders are more likely to exhibit supportive, consultative, and challenging leadership if senior leaders demonstrate inclusiveness—for example, by seeking out opinions that might differ from their own and by treating others with respect.

The importance of developing leaders at all levels

Our findings show that investing in leadership development across an organization—for all leadership positions—is an effective method for cultivating the combination of leadership behaviors that enhance psychological safety. Employees who report that their organizations invest substantially in leadership development are more likely to also report that their team leaders frequently demonstrate consultative, supportive, and challenging leadership behaviors. They also are 64 percent more likely to rate senior leaders as more inclusive (Exhibit 2). 8 We measured investing in leadership development by asking about agreement with the following statements: “my organization places a great deal of importance on developing its leaders,” and “my organization devotes significant resources to developing its leaders.” However, the results suggest that the effectiveness of these programs varies depending upon the skills they address.

Reorient the skills developed in leadership programs

Organizations often attempt to cover many topics in their leadership-development programs . But our findings suggest that focusing on a handful of specific skills and behaviors in these learning programs can improve the likelihood of positive leadership behaviors that foster psychological safety and, ultimately, of strong team performance. Some of the most commonly taught skills at respondents’ organizations—such as open-dialogue skills, which allow leaders to explore disagreements and talk through tension in a team—are among the ones most associated with positive leadership behaviors. However, several relatively untapped skill areas also yield beneficial results (Exhibit 3).

Two of the less-commonly addressed skills in formal programs are predictive of positive leadership. Training in sponsorship—that is, enabling others’ success ahead of one’s own—supports both consultative- and challenging-leadership behaviors, yet just 26 percent of respondents say their organizations include the skill in development programs. And development of situational humility, which 36 percent of respondents say their organizations address, teaches leaders how to develop a personal-growth mindset and curiosity. Addressing this skill is predictive of leaders displaying consultative behaviors.

Development at the top is equally important

According to the data, fostering psychological safety at scale begins with companies’ most senior leaders developing and embodying the leadership behaviors they want to see across the organization. Many of the same skills that promote positive team-leader behaviors can also be developed among senior leaders to promote inclusiveness. For example, open-dialogue skills and development of social relationships within teams are also important skill sets for senior leaders.

In addition, several skills are more important at the very top of the organization. Situational and cultural awareness, or understanding how beliefs can be developed based on selective observations and the norms in different cultures, are both linked with senior leaders’ inclusiveness.

Looking ahead

Given the quickening pace of change and disruption and the need for creative, adaptive responses from teams at every level, psychological safety is more important than ever. The organizations that develop the leadership skills and positive work environment that help create psychological safety can reap many benefits, from improved innovation, experimentation, and agility to better overall organizational health and performance. 9 We define organizational health as an organization’s ability to align on a clear vision, strategy, and culture; to execute with excellence; and to renew the organization’s focus over time by responding to market trends.

As clear as this call to action may be, “How do we develop psychological safety?” and, more specifically, “Where do we start?” remain the most common questions we are asked. These survey findings show that there is no time to waste in creating and investing in leadership development at scale to help enhance psychological safety. Organizations can start doing so in the following ways:

- Go beyond one-off training programs and deploy an at-scale system of leadership development. Human behaviors aren’t easily shifted overnight. Yet too often we see companies try to do so by using targeted training programs alone. Shifting leadership behaviors within a complex system at the individual, team, and enterprise levels begins with defining a clear strategy aligned to the organization’s overall aspiration and a comprehensive set of capabilities that are required to achieve it. It’s critical to develop a taxonomy of skills (having an open dialogue, for example) that not only supports the realization of the organization’s overall identity but also fosters learning and growth and applies directly to people’s day-to-day work. Practically speaking, while the delivery of learning may be sequenced as a series of trainings—and rapidly codified and scaled for all leaders across a cohort or function of the organization—those trainings will be even more effective when combined with other building blocks of a broader learning system, such as behavioral reinforcements. While learning experiences look much different now than before the COVID-19 pandemic , digital learning provides large companies with more opportunities to break down silos and create new connections across an organization through learning.

- Invest in leadership-development experiences that are emotional, sensory, and create aha moments. Learning experiences that are immersive and engaging are remembered more clearly and for a longer time. Yet a common pitfall of learning programs is an outsize focus on the content—even though it is usually not a lack of knowledge that holds leaders back from realizing their full potential. Therefore, it’s critical that learning programs prompt leaders to engage with and shift their underlying beliefs, assumptions, and emotions to bring about lasting mindset changes. This requires a learning environment that is both conducive to the often vulnerable process of learning and also expertly designed. Companies can begin with facilitated experiences that push learners toward personal introspection through targeted reflection questions and small, intimate breakout conversations. These environments can help leaders achieve increased self-awareness, spark the desire for further growth, and, with the help of reflection and feedback, drive collective growth and performance.

- Build mechanisms to make development a part of leaders’ day-to-day work. Formal learning and skill development serve as springboards in the context of real work; the most successful learning journeys account for the rich learning that happens in day-to-day work and interactions. The use of learning nudges (that is, daily, targeted reminders for individuals) can help learners overcome obstacles and move from retention to application of their knowledge. In parallel, the organization’s most senior leaders need to be the first adopters of putting real work at the core of their development, which requires senior leaders to role model—publicly—their own processes of learning. In this context, the concept of role models has evolved; rather than role models serving as examples of the finished product, they become examples of the work in progress, high on self-belief but low on perfect answers. These examples become strong signals for leaders across the organization that it is safe to be practicing, failing, and developing on the job.

The contributors to the development and analysis of this survey include Aaron De Smet , a senior partner in McKinsey’s New Jersey office; Kim Rubenstein, a research-science specialist in the New York office; Gunnar Schrah, a director of research science in the Denver office; Mike Vierow, an associate partner in the Brisbane office; and Amy Edmondson , the Novartis Professor of Leadership and Management at Harvard Business School.

This article was edited by Heather Hanselman, an associate editor in the Atlanta office.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Psychological safety, emotional intelligence, and leadership in a time of flux

Why rigor is the key ingredient to develop leaders

Diverse employees are struggling the most during COVID-19—here’s how companies can respond

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

Collection 12 March 2020

Top 50 Life and Biological Sciences Articles

We are pleased to share with you the 50 most read Nature Communications articles* in life and biological sciences published in 2019. Featuring authors from around the world, these papers highlight valuable research from an international community.

Browse all Top 50 subject area collections here .

*Based on data from Google Analytics, covering January-December 2019 (data has been normalised to account for articles published later in the year)

Genome-wide analysis identifies molecular systems and 149 genetic loci associated with income

Household income is used as a marker of socioeconomic position, a trait that is associated with better physical and mental health. Here, Hill et al. report a genome-wide association study for household income in the UK and explore its relationship with intelligence in post-GWAS analyses including Mendelian randomization.

- W. David Hill

- Neil M. Davies

- Ian J. Deary

A 5700 year-old human genome and oral microbiome from chewed birch pitch

Birch pitch is thought to have been used in prehistoric times as hafting material or antiseptic and tooth imprints suggest that it was chewed. Here, the authors report a 5,700 year-old piece of chewed birch pitch from Denmark from which they successfully recovered a complete ancient human genome and oral microbiome DNA.

- Theis Z. T. Jensen

- Jonas Niemann

- Hannes Schroeder

A short translational ramp determines the efficiency of protein synthesis

Several factors contribute to the efficiency of protein expression. Here the authors show that the identity of amino acids encoded by codons at position 3–5 significantly impact translation efficiency and protein expression levels.

- Manasvi Verma

- Junhong Choi

- Sergej Djuranovic

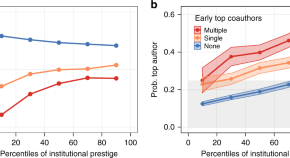

Early coauthorship with top scientists predicts success in academic careers

By examining publication records of scientists from four disciplines, the authors show that coauthoring a paper with a top-cited scientist early in one's career predicts lasting increases in career success, especially for researchers affiliated with less prestigious institutions.

- Tomaso Aste

- Giacomo Livan

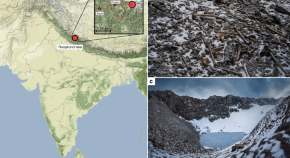

Ancient DNA from the skeletons of Roopkund Lake reveals Mediterranean migrants in India

Remains of several hundred humans are scattered around Roopkund Lake, situated over 5,000 meters above sea level in the Himalayan Mountains. Here the authors analyze genome-wide data from 38 skeletons and find 3 clusters with different ancestries and dates, showing the people were desposited in multiple catastrophic events.

- Éadaoin Harney

- Ayushi Nayak

Ketamine can reduce harmful drinking by pharmacologically rewriting drinking memories

Memories linking environmental cues to alcohol reward are involved in the development and maintenance of heavy drinking. Here, the authors show that a single dose of ketamine, given after retrieval of alcohol-reward memories, disrupts the reconsolidation of these memories and reduces drinking in humans.

- Ravi K. Das

- Sunjeev K. Kamboj

Sequential LASER ART and CRISPR Treatments Eliminate HIV-1 in a Subset of Infected Humanized Mice

Here, the authors show that sequential treatment with long-acting slow-effective release ART and AAV9- based delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 results in undetectable levels of virus and integrated DNA in a subset of humanized HIV-1 infected mice. This proof-of-concept study suggests that HIV-1 elimination is possible.

- Prasanta K. Dash

- Rafal Kaminski

- Howard E. Gendelman

XX sex chromosome complement promotes atherosclerosis in mice

Men and women differ in their risk of developing coronary artery disease, in part due to differences in their levels of sex hormones. Here, AlSiraj et al. show that the XX sex genotype regulates lipid metabolism and promotes atherosclerosis independently of sex hormones in mice.

- Yasir AlSiraj

- Lisa A. Cassis

Early-career setback and future career impact

Little is known about the long-term effects of early-career setback. Here, the authors compare junior scientists who were awarded a NIH grant to those with similar track records, who were not, and find that individuals with the early setback systematically performed better in the longer term.

- Benjamin F. Jones

- Dashun Wang

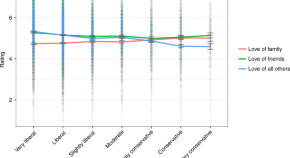

Ideological differences in the expanse of the moral circle

How do liberals and conservatives differ in their expression of compassion and moral concern? The authors show that conservatives tend to express concern toward smaller, more well-defined, and less permeable social circles, while liberals express concern toward larger, less well-defined, and more permeable social circles.

- Jesse Graham

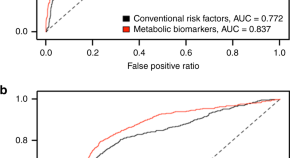

A metabolic profile of all-cause mortality risk identified in an observational study of 44,168 individuals

Biomarkers that predict mortality are of interest for clinical as well as research applications. Here, the authors analyze metabolomics data from 44,168 individuals and identify key metabolites independently associated with all-cause mortality risk.

- Joris Deelen

- Johannes Kettunen

- P. Eline Slagboom

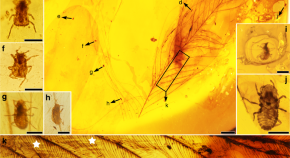

New insects feeding on dinosaur feathers in mid-Cretaceous amber

Numerous feathered dinosaurs and early birds have been discovered from the Jurassic and Cretaceous, but the early evolution of feather-feeding insects is not clear. Here, Gao et al. describe a new family of ectoparasitic insects from 10 specimens found associated with feathers in mid-Cretaceous amber.

- Taiping Gao

- Xiangchu Yin

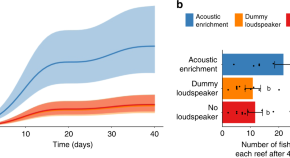

Acoustic enrichment can enhance fish community development on degraded coral reef habitat

Healthy coral reefs have an acoustic signature known to be attractive to coral and fish larvae during settlement. Here the authors use playback experiments in the field to show that healthy reef sounds can increase recruitment of juvenile fishes to degraded coral reef habitat, suggesting that acoustic playback could be used as a reef management strategy.

- Timothy A. C. Gordon

- Andrew N. Radford

- Stephen D. Simpson

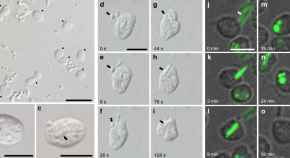

Phagocytosis-like cell engulfment by a planctomycete bacterium

Phagocytosis is a typically eukaryotic feature that could be behind the origin of eukaryotic cells. Here, the authors describe a bacterium that can engulf other bacteria and small eukaryotic cells through a phagocytosis-like mechanism.

- Takashi Shiratori

- Shigekatsu Suzuki

- Ken-ichiro Ishida

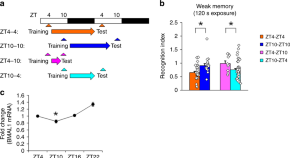

Hippocampal clock regulates memory retrieval via Dopamine and PKA-induced GluA1 phosphorylation

The neural mechanisms that lead to a relative deficit in memory retrieval in the afternoon are unclear. Here, the authors show that the circadian - dependent transcription factor BMAL1 regulates retrieval through dopamine and glutamate receptor phosphorylation.

- Shunsuke Hasegawa

- Hotaka Fukushima

- Satoshi Kida

Agreement between two large pan-cancer CRISPR-Cas9 gene dependency data sets

Integrating independent large-scale pharmacogenomic screens can enable unprecedented characterization of genetic vulnerabilities in cancers. Here, the authors show that the two largest independent CRISPR-Cas9 gene-dependency screens are concordant, paving the way for joint analysis of the data sets.

- Joshua M. Dempster

- Clare Pacini

- Francesco Iorio

Phylogenomics of 10,575 genomes reveals evolutionary proximity between domains Bacteria and Archaea

The authors build a reference phylogeny of 10,575 evenly-sampled bacterial and archaeal genomes, based on 381 markers. The results indicate a remarkably closer evolutionary proximity between Archaea and Bacteria than previous estimates that used fewer “core” genes, such as the ribosomal proteins.

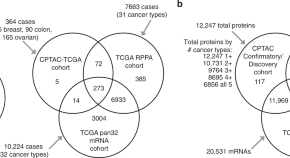

Pan-cancer molecular subtypes revealed by mass-spectrometry-based proteomic characterization of more than 500 human cancers

Mass-spectrometry-based profiling can be used to stratify tumours into molecular subtypes. Here, by classifying over 500 tumours, the authors show that this approach reveals proteomic subgroups which cut across tumour types.

- Fengju Chen

- Darshan S. Chandrashekar

- Chad J. Creighton

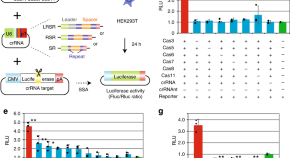

CRISPR-Switch regulates sgRNA activity by Cre recombination for sequential editing of two loci

Inducible genome editing systems often suffer from leakiness or reduced activity. Here the authors develop CRISPR-Switch, a Cre recombinase ON/OFF-controlled sgRNA cassette that allows consecutive editing of two loci.

- Krzysztof Chylinski

- Maria Hubmann

- Ulrich Elling

CRISPR-Cas3 induces broad and unidirectional genome editing in human cells

Class 1 CRISPR systems are not as developed for genome editing as Class 2 systems are. Here the authors show that Cas3 can be used to generate functional knockouts and knock-ins, as well as Cas3-mediated exon-skipping in DMD cells.

- Hiroyuki Morisaka

- Kazuto Yoshimi

- Tomoji Mashimo

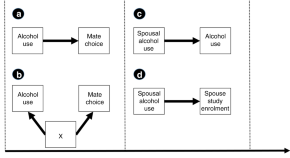

Genetic evidence for assortative mating on alcohol consumption in the UK Biobank

From observational studies, alcohol consumption behaviours are known to be correlated in spouses. Here, Howe et al. use partners’ genotypic information in a Mendelian randomization framework and show that a SNP in the ADH1B gene associates with partner’s alcohol consumption, suggesting that alcohol consumption affects mate choice.

- Laurence J. Howe

- Daniel J. Lawson

- Gibran Hemani

The autophagy receptor p62/SQST-1 promotes proteostasis and longevity in C. elegans by inducing autophagy

While the cellular recycling process autophagy has been linked to aging, the impact of selective autophagy on lifespan remains unclear. Here Kumsta et al. show that the autophagy receptor p62/SQSTM1 is required for hormetic benefits and p62/SQSTM1 overexpression is sufficient to extend C. elegans lifespan and improve proteostasis.

- Caroline Kumsta

- Jessica T. Chang

- Malene Hansen

The coincidence of ecological opportunity with hybridization explains rapid adaptive radiation in Lake Mweru cichlid fishes

Recent studies have suggested that hybridization can facilitate adaptive radiations. Here, the authors show that opportunity for hybridization differentiates Lake Mweru, where cichlids radiated, and Lake Bangweulu, where cichlids did not radiate despite ecological opportunity in both lakes.

- Joana I. Meier

- Rike B. Stelkens

- Ole Seehausen

Flagellin-elicited adaptive immunity suppresses flagellated microbiota and vaccinates against chronic inflammatory diseases

Gut microbiota alterations, including enrichment of flagellated bacteria, are associated with metabolic syndrome and chronic inflammatory diseases. Here, Tran et al. show, in mice, that elicitation of mucosal anti-flagellin antibodies protects against experimental colitis and ameliorates diet-induced obesity.

- Hao Q. Tran

- Ruth E. Ley

- Benoit Chassaing

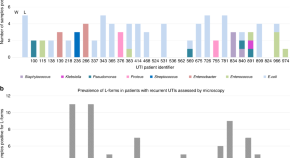

Possible role of L-form switching in recurrent urinary tract infection

The reservoir for recurrent urinary tract infection in humans is unclear. Here, Mickiewicz et al. detect cell-wall deficient (L-form) E. coli in fresh urine from patients, and show that the isolated bacteria readily switch between walled and L-form states.

- Katarzyna M. Mickiewicz

- Yoshikazu Kawai

- Jeff Errington

Dual microglia effects on blood brain barrier permeability induced by systemic inflammation

Although it is known that microglia respond to injury and systemic disease in the brain, it is unclear if they modulate blood–brain barrier (BBB) integrity, which is critical for regulating neuroinflammatory responses. Here authors demonstrate that microglia respond to inflammation by migrating towards and accumulating around cerebral vessels, where they initially maintain BBB integrity via expression of the tight-junction protein Claudin-5 before switching, during sustained inflammation, to phagocytically remove astrocytic end-feet resulting in impaired BBB function

- Koichiro Haruwaka

- Ako Ikegami

- Hiroaki Wake

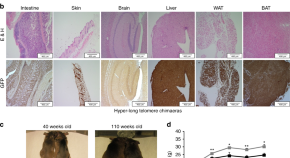

Mice with hyper-long telomeres show less metabolic aging and longer lifespans

Telomere shortening is associated with aging. Here the authors analyze mice with hyperlong telomeres and demonstrate that longer telomeres than normal have beneficial effects such as delayed metabolic aging, increased longevity and less incidence of cancer.

- Miguel A. Muñoz-Lorente

- Alba C. Cano-Martin

- Maria A. Blasco

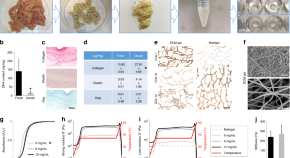

Extracellular matrix hydrogel derived from decellularized tissues enables endodermal organoid culture

Organoid cultures have been developed from multiple tissues, opening new possibilities for regenerative medicine. Here the authors demonstrate the derivation of GMP-compliant hydrogels from decellularized porcine small intestine which support formation and growth of human gastric, liver, pancreatic and small intestinal organoids.

- Giovanni Giuseppe Giobbe

- Claire Crowley

- Paolo De Coppi

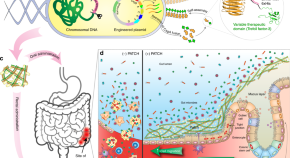

Engineered E. coli Nissle 1917 for the delivery of matrix-tethered therapeutic domains to the gut

Anti-inflammatory treatments for gastrointestinal diseases can often have detrimental side effects. Here the authors engineer E. coli Nissle 1917 to create a fibrous matrix that has a protective effect in DSS-induced colitis mice.

- Pichet Praveschotinunt

- Anna M. Duraj-Thatte

- Neel S. Joshi

Ambient black carbon particles reach the fetal side of human placenta

Exposure to air pollution during pregnancy has been associated with impaired birth outcomes. Here, Bové et al. report evidence of black carbon particle deposition on the fetal side of human placentae, including at early stages of pregnancy, suggesting air pollution could affect birth outcome through direct effects on the fetus.

- Hannelore Bové

- Eva Bongaerts

- Tim S. Nawrot

Real-time decoding of question-and-answer speech dialogue using human cortical activity

Speech neuroprosthetic devices should be capable of restoring a patient’s ability to participate in interactive dialogue. Here, the authors demonstrate that the context of a verbal exchange can be used to enhance neural decoder performance in real time.

- David A. Moses

- Matthew K. Leonard

- Edward F. Chang

In-cell identification and measurement of RNA-protein interactions

RNA-interacting proteome can be identified by RNA affinity purification followed by mass spectrometry. Here the authors developed a different RNA-centric technology that combines high-throughput immunoprecipitation of RNA binding proteins and luciferase-based detection of their interaction with the RNA.

- Antoine Graindorge

- Inês Pinheiro

- Alena Shkumatava

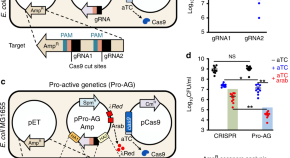

A bacterial gene-drive system efficiently edits and inactivates a high copy number antibiotic resistance locus

Genedrives bias the inheritance of alleles in diploid organisms. Here, the authors develop a gene-drive analogous system for bacteria, selectively editing and clearing plasmids.

- J. Andrés Valderrama

- Surashree S. Kulkarni

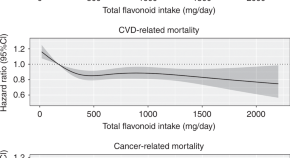

Flavonoid intake is associated with lower mortality in the Danish Diet Cancer and Health Cohort

The studies showing health benefits of flavonoids and their impact on cancer mortality are incomplete. Here, the authors perform a prospective cohort study in Danish participants and demonstrate an inverse association between regular flavonoid intake and both cardiovascular and cancer related mortality.

- Nicola P. Bondonno

- Frederik Dalgaard

- Jonathan M. Hodgson

Senescent cell turnover slows with age providing an explanation for the Gompertz law

One of the underlying causes of aging is the accumulation of senescent cells, but their turnover rates and dynamics during ageing are unknown. Here the authors measure and model senescent cell production and removal and explore implications for mortality.

- Amit Agrawal

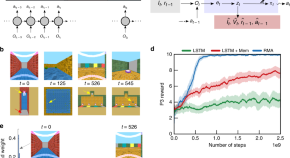

Optimizing agent behavior over long time scales by transporting value

People are able to mentally time travel to distant memories and reflect on the consequences of those past events. Here, the authors show how a mechanism that connects learning from delayed rewards with memory retrieval can enable AI agents to discover links between past events to help decide better courses of action in the future.

- Chia-Chun Hung

- Timothy Lillicrap

Mutant p53 drives clonal hematopoiesis through modulating epigenetic pathway

Ageing is associated with clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP), which is linked to increased risks of hematological malignancies. Here the authors uncover an epigenetic mechanism through which mutant p53 drives clonal hematopoiesis through interaction with EZH2.

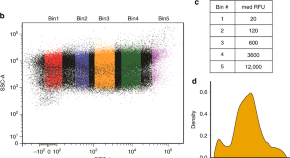

A systematic evaluation of single cell RNA-seq analysis pipelines

There has been a rapid rise in single cell RNA-seq methods and associated pipelines. Here the authors use simulated data to systematically evaluate the performance of 3000 possible pipelines to derive recommendations for data processing and analysis of different types of scRNA-seq experiments.

- Beate Vieth

- Swati Parekh

- Ines Hellmann

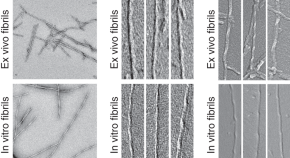

Cryo-EM structure and polymorphism of Aβ amyloid fibrils purified from Alzheimer’s brain tissue

Alzheimer’s disease is characterised by the deposition of Aβ amyloid fibrils and tau protein neurofibrillary tangles. Here the authors use cryo-EM to structurally characterise brain derived Aβ amyloid fibrils and find that they are polymorphic and right-hand twisted, which differs from in vitro generated Aβ fibrils.

- Marius Kollmer

- William Close

- Marcus Fändrich

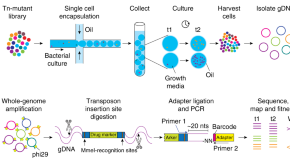

Droplet Tn-Seq combines microfluidics with Tn-Seq for identifying complex single-cell phenotypes

Culturing transposon-mutant libraries in pools can mask complex phenotypes. Here the authors present microfluidics mediated droplet Tn-Seq, which encapsulates individual mutants, promotes isolated growth and enables cell-cell interaction analyses.

- Derek Thibault

- Paul A. Jensen

- Tim van Opijnen

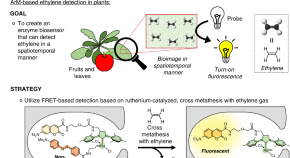

An artificial metalloenzyme biosensor can detect ethylene gas in fruits and Arabidopsis leaves