- Free Study Planner

- Residency Consulting

- Free Resources

- Med School Blog

- 1-888-427-7737

How to Get Involved in Research As A Medical Student

- by Dr. Mike Ren

- Apr 11, 2023

- Reviewed by: Amy Rontal, MD

It goes without saying that getting involved in research as a medical student, while an important part of the medical school experience , can also be an intimidating prospect. Not only are you balancing a hectic schedule, but it’s tough to know how (and where) to get started.

So, how exactly do you secure an appropriate, fulfilling research opportunity that will enhance your residency application and put you on track for success? To answer that question, we’ll walk through the absolute fundamentals of pursuing research as a medical student.

Commitment, Benefits, and Where to Begin

What are the advantages of participating in research as a medical student.

As mentioned, r esearch is an important component of the residency application. Particularly, if you are interested and invested in a particular aspect of medicine or if you want to match into a competitive specialty or at a nationally-ranked academic institution.

Research experience helps to strengthen a resume and allows candidates to fill in for gaps in their application. For instance, an academic program director might be willing to overlook an applicant’s marginal pass on an elective rotation if that applicant demonstrates strong participation in research. This is not a “magic bullet” to matching with a residency program, however—the priority here is still pass your rotations and national licensing exams.

Further, some applicants find research opportunities so appealing that they even take a research year to churn out publications and present at national conferences. Quality and quantity are both important in terms of publications and presentations. Participating in research as a medical student can help you network as well, further advancing your career in medicine, academia, or industry.

So, how do you get into a research project that eventually yields publications and acclaim?

How much of a time commitment is research?

Look, I get it. You’re a busy medical student. Last week you prepared in order to lead a women’s health interest group meeting, this week you have those pesky histology lectures to catch up on, and next week is a particularly intimidating anatomy practical. Not to mention, you haven’t had a date night with your significant other since Valentine’s Day because you’ve been busy with your pharmacology study group, and you still have to call your mom.

How will you possibly have time for research in an already hectic MS1 year and how much time should you allot to the cause?

To put things into perspective, keep in mind that research time ranges from entire month-long electives to a more longitudinal approach. The most common is longitudinal research— this involves working on a project a few hours a week over the course of 6-18 months, typically with a few dedicated weeks near completion to make the publishing deadline. Busy students should dedicate around 10-20 hours weekly for tasks such as obtaining IRB approval, reviewing charts, or writing drafts.

Alright, I’m interested. Where do I start?

You’ve heard this before. “Just ask!” Often, it’s as simple as that. Create opportunities for yourself by being enthusiastic and inquisitive. Seek out attendings or residents on your rotations, ask if there are any research projects they know of or are involved in. Research is a team effort, and oftentimes, residents will have unfinished projects that could use the help of a medical student to complete.

Another common finding is that graduating students or students who’ve changed interests do not wish to further continue their projects. This can be a great place to pick up where they left off, as some of the work may already be finished before you even start. (As a disclaimer for this approach: I would be cautious to ask to ensure the project in question is not an issue. Red flags in this case are if the publication process is in limbo or significantly delayed, if funding has ceased, or if the PI plans to change roles/jobs.)

Cast a wide net and email attendings whose research you find interesting and ask if there is any way to get involved. Some of your requests will be ignored (don’t take it personally, people are just busy!) but by and large, academics are helpful and even if they don’t have a project that matches your interests, they will likely have a colleague to direct you to.

So, whether you are interested in starting a project or joining an existing one, start drafting your emails. After all, what do you have to lose?

Choosing a Research Opportunity

Pick an activity that aligns with your goals.

Naturally, you want to ensure the research activity you participate in aligns with your goals because, ultimately when you interview for residency or an introductory consulting position, or for a job in biotech, having a coherent theme in your publications that position alongside your passions will distinguish you amongst your peers.

Find a good fit with your PI

To get started on a research project, you will first need to find a mentor or principal investigator (PI). Criteria vary but generally, most agree that a good PI is:

- 1. Prolific: They have had various publications over the past decade with academic peer-reviewed journals.

- 2. Responsive: They do not take weeks to answer emails or are not away from their lab for weeks at a time.

- 3. Has aligned interests: Publication takes a lot of work, often involving potentially hundreds of hours of effort. Thus, you and your PI should see it as a big deal. Make sure it is something you are interested in and advances your career whether you’re in a lab doing cell cultures or editing epidemiology papers or designing bio wearables at the intersection of healthcare and technology.

- 4. Has adequate funding: This ensures you can be compensated, or at the very least your project has the funding necessary to move forward. Publishing in top-tier academic journals isn’t cheap!

Keep in mind that some residencies have research time built in, often in the form of research electives that can last months to a year. If your desired program allows, and you remain interested in research, share your research interests and projects to see if it can be continued at the institution, or if there is something in a similar realm.

Decide which type of research project you’d like to pursue

The following are different types of medical research you could pursue as a medical student. This is not a comprehensive list, but rather, a starting point for where to look and how to increase your research output:

Image Source: NIH

Option #1: Case Reports and Series

A case report is a detailed write-up about the clinical course of a particular patient —an interesting presentation, an unusual case, a new potential treatment. It is used to describe an unusual or novel occurrence based on disease process, diagnosis, and/or treatment.

Pay attention when you are on rotations if you see anything interesting or unusual. Do a quick PubMed search to see what’s already out there and if there isn’t much, take the initiative and ask your attending to write it.

Case series, on the other hand, look at multiple patients in a retrospective manner. Case series are more tedious to write but also look better on an application as they provide more significant scientific conclusions.

- – Easy to write

- – Least time-consuming

- – No funding needed

- – Quick to publish if yours is accepted

- – Usually the least intensive data mining

- – Not as impressive (thus easier to write and fast to publish)

- – Journals receive so many so it can be difficult to publish

Option #2: Clinical Research

This is the cream of the crop, the nitty gritty evidence-based medical research. Typically this includes the studies and trials you read about for the biostats portion of your exams. Anything from randomized trials to case-controlled trials and cohort studies are included in this broad category.

- – Highly regarded on applications

- – AOA offers students funding for certain research projects

- – Significant contribution to medicine/science in your field

- – Publication includes more prestigious journals

- – Many barriers of entry (time, funding, depth of research)

- – Requires IRB review meaning strict protocols

- – Requires large sample sizes, thus requiring dedicated time and often funding.

- – Students often use a dedicated research year to gain experience in this area.

- – Slow and grueling publication process and peer review

Option #3: Literature/Chart Review

Systematic literature or chart reviews basically existing work on a particular, unresolved, or controversial topic in medicine. There are different categories including meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and traditional literature reviews.

This type of research typically involves combing through dozens to hundreds of charts in search of information that is relevant to the research question you are asking (i.e., scouring through charts for patients with multiple myeloma that were treated with a particular therapy and looking at the outcomes). Programs like Zotero can be helpful to make your searches easier.

Furthermore, research librarians can be extremely helpful in using search tools, formatting your research, and going about the systematic review process in general. I highly recommend you reach out to your school librarian before you dive in as they are often a high-yield resource.

- – Accessible for students

- – Meta-analysis and systematic reviews offer higher value and are more renowned

- – Can often be done in remote collaboration

- – Flexible hours of work

- – Time-consuming to review

- – You will need access to various journals to be reviewed

- – Tedious and repetitive work that is heavy in data analysis

- – Highly specialized! A sk your attendings for topic ideas as they will have a better sense of what is relevant in the field and what has the best chance of publication

What to Do After Publishing Your Research

You put in the effort, now it’s time to reap the rewards! While your friends or parents might not take note that you’re a footnote in this publication in NEJM, resident programs are sure to find out.

On ERAS, there are separate sections for presentations and publications —one dropdown for papers that have already been published, and one for papers that have been submitted/accepted/in press. These appear separately on ERAS, so it’s ideal to have more in the “published” section, preferably in journals that are within your field. The topics look something like this:

- – Peer-Reviewed Journal Articles/Abstracts

- – Peer-Reviewed Journal Articles/Abstracts (Other than Published = Submitted/Accepted)

- – Peer-Reviewed Book Chapter

- – Scientific Monograph

- – Poster Presentation

- – Oral Presentation

- – Peer-Reviewed Online Publication

- – Non-Peer-Reviewed Online Publication

6 Tips for Medical Students Getting Involved in Research

- 1. Realize that research can be a very slow process. Even prestigious journals can hold on to submissions for months before ultimately making the decision to publish.

- 2. We are not cavemen, use tools! Web and citation tools such as Medeley and Connected Papers are free to use and help a great deal when it comes to tracking literature.

- 3. Formatting is important. Always read the instructions for authors on the websites of the journals you are submitting to. Each journal will have different, often strict specifications from the formatting and scientific writing standards to citation guidelines. The process between submission and publication will be a lot smoother if you follow the instructions ahead of time to avoid the back and forth before going to peer review.

- 4. Writing is a team effort. Be sure to consult your teammates and definitely notify your PI if you have a concern or are unsure about some data.

- 5. You can only submit a particular paper to one journal at a time. Don’t submit the same paper to multiple journals at the same time.

- 6. Lastly, there have been increasing reports of predatory publishing scams. Always use protection and avoid these by first verifying publications that exist on legitimate databases such as PubMed. Stay safe!

Overall, the process of publishing research can be very frustrating, but also very rewarding, especially if you are genuinely interested in research or the topic. Remember to invest time to understand the demands before committing to the project.

Discuss with the principal investigator what you want out of the project and be clear about your time commitment and intentions. Ask classmates for help and pass the word on to others. If you need it, take some extra time for your research. Good luck!

About the Author

Mike is a driven tutor and supportive advisor. He received his MD from Baylor College of Medicine and then stayed for residency. He has recently taken a faculty position at Baylor because of his love for teaching. Mike’s philosophy is to elevate his students to their full potential with excellent exam scores, and successful interviews at top-tier programs. He holds the belief that you learn best from those close to you in training. Dr. Ren is passionate about his role as a mentor and has taught for much of his life – as an SAT tutor in high school, then as an MCAT instructor for the Princeton Review. At Baylor, he has held review courses for the FM shelf and board exams as Chief Resident. For years, Dr. Ren has worked closely with the office of student affairs and has experience as an admissions advisor. He has mentored numerous students entering medical and residency and keeps in touch with many of them today as they embark on their road to aspiring physicians. His supportiveness and approachability put his students at ease and provide a safe learning environment where questions and conversation flow. For exam prep, Mike will help you develop critical reasoning skills and as an advisor he will hone your interview skills with insider knowledge to commonly asked admissions questions.

Related Posts

Quiz: Which “Scrubs” Character Are You in Your Clinical Rotations?

Resident vs Attending: What’s the Difference? Role, Responsibility, Salary, & More

Step 2 Percentiles: How to Understand & Interpret Your Score in a Step 1 Pass/Fail World

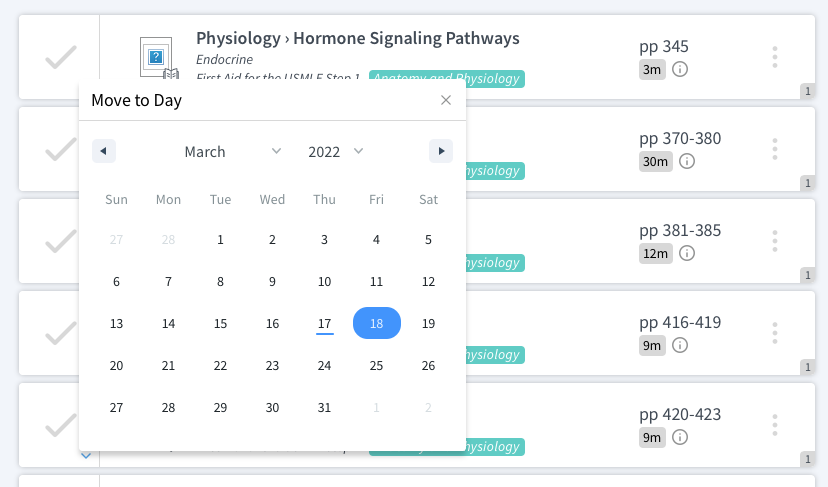

Search the blog, try blueprint med school study planner.

Create a personalized study schedule in minutes for your upcoming USMLE, COMLEX, or Shelf exam. Try it out for FREE, forever!

Could You Benefit from Tutoring?

Sign up for a free consultation to get matched with an expert tutor who fits your board prep needs

Find Your Path in Medicine

A side by side comparison of specialties created by practicing physicians, for you!

Popular Posts

Need a personalized USMLE/COMLEX study plan?

How to Conduct Research During Medical School

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Most med schools in the United States require that you participate in some sort of scholarly project. Participation in the academic life of medicine is a great way to enhance your residency applications, and it may even be expected or required to successfully match in the most competitive specialties.

Traditionally, medical student research took the shape of a formal research opportunity in a research lab with a research mentor, culminating in a publication. Today, research in medical school takes a variety of forms, including the traditional one.

Beyond the typical lab format, medical students engage in scholarship by conducting poster presentations, writing up case presentations of interesting diseases they have encountered on the wards, or participating in quality improvement initiatives or other health systems science projects. All of these scholarly pursuits fall under the broad category of “research”, which may be required during medical school, and all contribute to the strength of a student’s residency application.

Take the Online Course: Research Ethics

Covers all essentials: nuremberg code ✓, belmont report ✓, declaration of helsinki ✓, informed consent ✓

Is It Even Possible to Do Research in Medical School?

With all the day-to-day challenges of medical school, it can be difficult to see where time for research fits in. With good planning and time management, however, you can include research in medical school. While fulfilling your clerkship requirements, studying and passing exams and courses, and taking care of patients are all top priorities, carving out time for research is certainly a possibility, especially on lighter rotations and with the udicious use of elective time.

Many medical schools now offer a dedicated research period for you to engage in scholarship. Depending on the project, this period may be more or less time than you need to complete your research. You should check to see if your school offers dedicated time for research, and when it is.If you do have a dedicated research block, checking with your school about the expectations for deliverables at the end of the time period, as well as whether the block is structured or unstructured, will help you to make the most of this block.

If your school does not offer a specific time period for research and you anticipate needing to work on a project full-time, using elective time for research or scheduling research during lighter rotations can be a great way to make the time you need for research.

When is the best time to do research in medical school?

For many medical students, especially those applying to highly competitive specialties, you’ll want to start thinking about when to do research in medical school early in your academic career. If you know you have specific research or subspecialty interest going into medical school, start looking for a research project or mentor as soonas possible. This will maximize your chances of completing published research by the time you need to apply for a residency program.

If you are not sure about research or aren’t interested in conducting research at all, waiting until closer to your residency application and choosing an interesting case or project to present as a case conference or poster may make more sense. If you do intend to publish a paper or complete a large scholarly project, make sure you start early so that your project is complete in time for residency applications, recognizing that not every project results in a publication. For larger projects, it makes sense to have identified a research mentor and to start working on your project sometime before the beginning of your second year.

Keep in mind that the publication process of peer review and article revisions can take longer than anticipated, and your article may not appear in print until several months after you submit your abstract.

Smaller projects, such as a case vignette or poster presentation, typically have a much faster turnaround time – usually only a few months from project inception to presentation, depending on the venue where you present.

Do you have to do research in medical school?

Even for physicians in training who have no desire to do research after medical school, research can be a useful way to build skills that will be helpful in their future career. For instance, a student interested in hospital medicine might use the research time to complete a quality improvement project on reducing the risk of infections acquired in a hospital, which in turn might help them in a future role as a medical director.

A future general surgeon might decide to use the research time to get an MBA, helping them gain the business skills necessary to run a successful independent practice. A prospective infectious disease specialist might conduct a public health study that gets them comfortable with interpreting statistics, which could be beneficial when running a local health department.

Students who are not interested in staying in academics after graduation but are required to do research should make use of dedicated research time to build skills that they can apply outside of the academic world.

How to Do Research as a Medical Student

Every good research project starts with a question. You’re far more likely to stay engaged in research, and to produce a good research product, if you have a real interest in the question your project aims to answer. Once you’ve identified a question you hope to answer, ask your professors, attending physicians, and even other classmates if they know of anyone working on a similar question.

While you might not identify someone working on exactly what you are interested in, you’ll likely find someone with similar interests who can direct you to someone who is well-aligned with your interests. Once you identify a research mentor, it’s up to you to determine what your goals are in doing research.

If you intend to publish a paper that appears in a top-notch medical journal, for instance, your research will probably require more time and effort than if you hope to do a case presentation of an interesting disease you encountered on rounds.

Try to tailor the scope of your project to the time you have available to complete it. “I want to cure cancer” is not a realistic goal for a research project to complete as a medical student, but working on a specific gene pathway with a goal of presenting a poster at a national conference might be!

How to find research opportunities

Finding research opportunities as a medical student starts with identifying your area of interest. Do you have a subspecialty you are particularly fascinated by? If so, reaching out to an academic specialist in your area of interest is a great first step to finding research opportunities.

Fascinated by a particular case you saw on rounds? Ask your attending physician if they think the case might be appropriate for a poster presentation or to present at an academic conference. Not interested in writing up case reports or writing long research abstracts? Maybe an opportunity in quality improvement is right for you – ask your attending physicians if there are any hospital-level projects or initiatives which could benefit from some help.

Do you have a specific idea that you think could change the world? Try applying for a research grant or scholarship to help fund that opportunity and make it a reality. In many medical schools, and especially in those associated with academic research centers, the only limitations on research opportunities are those of your own imagination!

How is medical research funded?

Most medical research projects conducted by medical students are not funded and occur on the side, with a student volunteering their time and effort toward a project. However, if you are planning on a more extensive project that would take you away from your normal studies for a year or more, there are a variety of foundations and funded research opportunities that you can use to support yourself during the time you are conducting your research.

Generally speaking, the best opportunity to engage in funded medical research is by enrolling in a combined MD/PhD program.

If you are interested in a specific field of study and want to have protected, dedicated time to engage in medical research prior to residency, a combined MD/PhD program will give you the best balance of clinical and research training. However, MD/PhD programs are highly selective and are not available at every medical school.

You can learn more about combined degree programs on the AAMC website . The American Physician Scientists Association also maintains a list of funding opportunities for MD/PhD candidates on their website.

To Sum It Up…

Spending some time engaging in research during medical school can be rewarding, both personally and professionally. Although opportunities to engage in traditional research abound in medical school, students who are not interested in this can explore alternatives to traditional research, like case presentations, quality improvement projects, or even dual degree programs like an MBA. Pursuing research in any of these forms can be a great way to improve your residency application and help you develop the skills you need to succeed long after medical school.

Dr. Brennan Kruszewski is a practicing internist and primary care physician in Beachwood, Ohio. He graduated from Emory University School of Medicine in 2018, and recently completed his residency in Internal Medicine at University Hospitals/Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. He enjoys writing about a variety of medical topics, including his time in academic medicine and how to succeed as a young physician. In his spare time, he is an avid cyclist, lover of classical literature, and choral singer.

Explore materials

Free downloads

Share this post:

Further Reading

The Best Books for Medical Students

Medicine and Media: How Real are Doctors in Movies?

How to Take a Patient History with OLD CARTS

- Data Privacy

- Terms and Conditions

- Legal Information

USMLE™ is a joint program of the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB®) and National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME®). MCAT is a registered trademark of the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). NCLEX®, NCLEX-RN®, and NCLEX-PN® are registered trademarks of the National Council of State Boards of Nursing, Inc (NCSBN®). None of the trademark holders are endorsed by nor affiliated with Lecturio.

Save 50% Now >>

User Reviews

Get premium to test your knowledge.

Lecturio Premium gives you full access to all content & features

Get Premium to watch all videos

Verify your email now to get a free trial.

Create a free account to test your knowledge

Lecturio Premium gives you full access to all contents and features—including Lecturio’s Qbank with up-to-date board-style questions.

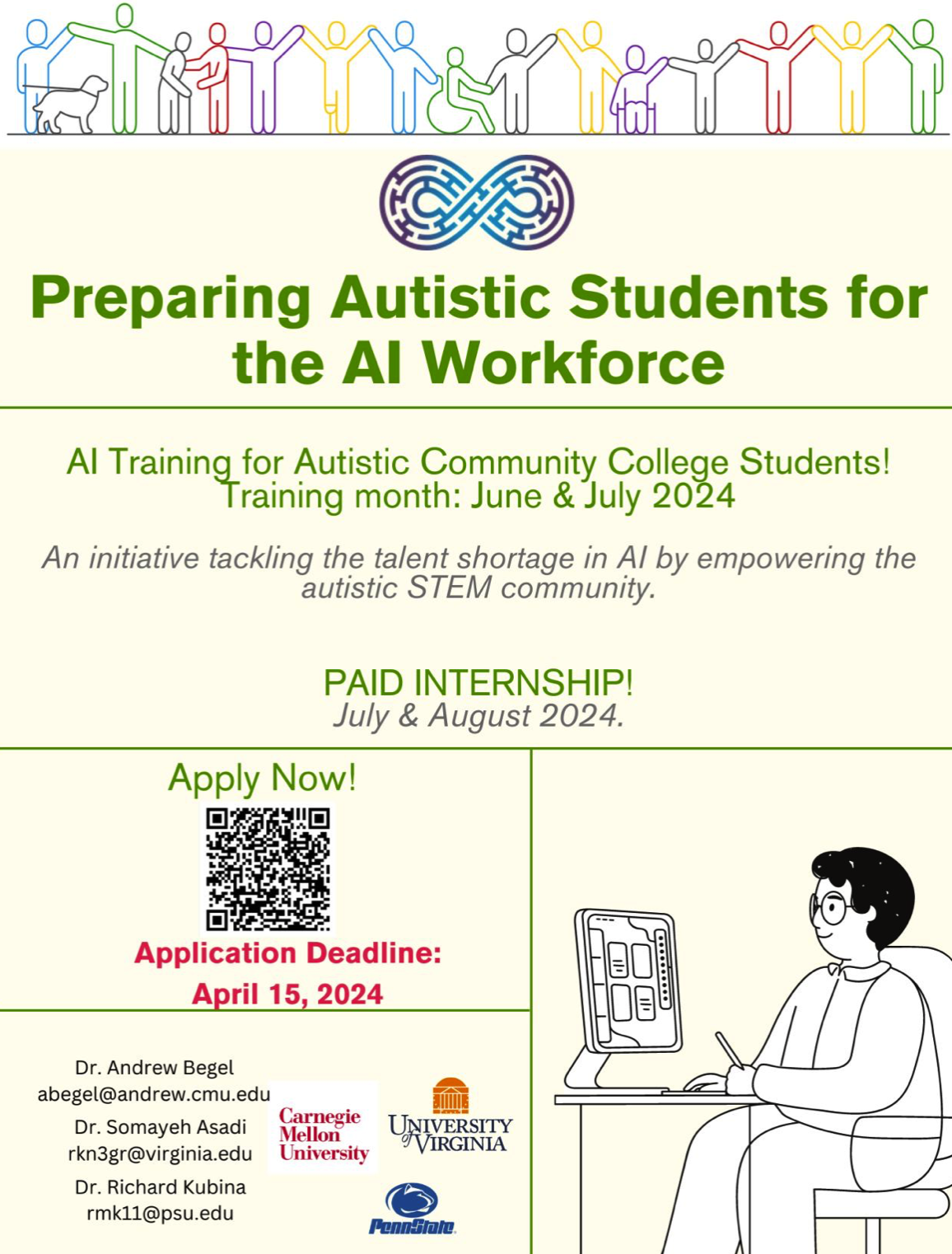

Research and Training Opportunities

New section.

Looking for ways to enrich your medical school experience? Check out our directories of clinical, research, and public health opportunities.

Looking for ways to enrich your medical school experience? Search for fellowships, internships, summer programs, scholarships, and grants currently available in the United States and abroad.

Earn two degrees in four to five years to improve the health of the individuals and communities you serve.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Medical Research Scholars Program (MRSP) is a comprehensive, year-long research enrichment program designed to attract the most creative, research-oriented medical, dental, and veterinary students to the intramural campus of the NIH in Bethesda, MD.

Summer programs at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) provide an opportunity to spend a summer working at the NIH side-by-side with some of the leading scientists in the world, in an environment devoted exclusively to biomedical research.

A Realistic Guide to Medical School

Written by UCL students for students

Top 10 Tips: Getting into Research as a Medical Student

Introducing our new series: Top 10 Tips – a simple guide to help you achieve your goals!

In this blog post, Jessica Xie (final year UCL medical student) shares advice on getting into research as a medical student.

Disclaimers:

- Research is not a mandatory for career progression, nor is it required to demonstrate your interest in medicine.

- You can dip into and out of research throughout your medical career. Do not feel that you must continue to take on new projects once you have started; saying “no, thank you” to project opportunities will allow you to focus your energy and time on things in life that you are more passionate about for a more rewarding experience.

- Do not take on more work than you are capable of managing. Studying medicine is already a full-time job! It’s physically and mentally draining. Any research that you get involved with is an extracurricular interest.

I decided to write this post because, as a pre-clinical medical student, I thought that research only involved wet lab work (i.e pipetting substances into test tubes). However, upon undertaking an intercalated Bachelor of Science (iBSc) in Primary Health Care, I discovered that there are so many different types of research! And academic medicine became a whole lot more exciting…

Here are my Top 10 Tips on what to do if you’re a little unsure about what research is and how to get into it:

TIP 1: DO YOUR RESEARCH (before getting into research)

There are three questions that I think you should ask yourself:

- What are my research interests?

Examples include a clinical specialty, medical education, public health, global health, technology… the list is endless. Not sure? That’s okay too! The great thing about research is that it allows deeper exploration of an area of Medicine (or an entirely different field) to allow you to see if it interests you.

2. What type of research project do I want to do?

Research evaluates practice or compares alternative practices to contribute to, lend further support to or fill in a gap in the existing literature.

There are many different types of research – something that I didn’t fully grasp until my iBSc year. There is primary research, which involves data collection, and secondary research, which involves using existing data to conduct further research or draw comparisons between the data (e.g. a meta-analysis of randomised control trials). Studies are either observational (non-interventional) (e.g. case-control, cross-sectional) or interventional (e.g. randomised control trial).

An audit is a way of finding out if current practice is best practice and follows guidelines. It identifies areas of clinical practice could be improved.

Another important thing to consider is: how much time do I have? Developing the skills required to lead a project from writing the study protocol to submitting a manuscript for publication can take months or even years. Whereas, contributing to a pre-planned or existing project by collecting or analysing data is less time-consuming. I’ll explain how you can find such projects below.

3. What do I want to gain from this experience?

Do you want to gain a specific skill? Mentorship? An overview of academic publishing? Or perhaps to build a research network?

After conducting a qualitative interview study for my iBSc project, I applied for an internship because I wanted to gain quantitative research skills. I ended up leading a cross-sectional questionnaire study that combined my two research interests: medical education and nutrition. I sought mentorship from an experienced statistician, who taught me how to use SPSS statistics to analyse and present the data.

Aside from specific research skills, don’t forget that you will develop valuable transferable skills along the way, including time-management, organisation, communication and academic writing!

TIP 2: BE PROACTIVE

Clinicians and lecturers are often very happy for medical students to contribute to their research projects. After a particularly interesting lecture/ tutorial, ward round or clinic, ask the tutor or doctors if they have any projects that you could help them with!

TIP 3: NETWORKING = MAKING YOUR OWN LUCK

Sometimes the key to getting to places is not what you know, but who you know. We can learn a lot from talking to peers and senior colleagues. Attending hospital grand rounds and conferences are a great way to meet people who share common interests with you but different experiences. I once attended a conference in Manchester where I didn’t know anybody. I befriended a GP, who then gave me tips on how to improve my poster presentation. He shared with me his experience of the National institute of Health Research (NIHR) Integrated Academic Training Pathway and motivated me to continue contributing to medical education alongside my studies.

TIP 4: UTILISE SOCIAL MEDIA

Research opportunities, talks and workshops are advertised on social media in abundance. Here are some examples:

Search “medical student research” or “medsoc research” into Facebook and lots of groups and pages will pop up, including UCL MedSoc Research and Academic Medicine (there is a Research Mentoring Scheme Mentee Scheme), NSAMR – National Student Association of Medical Research and International Opportunities for Medical Students .

Search #MedTwitter and #AcademicTwitter to keep up to date with ground-breaking research. The memes are pretty good too.

Opportunities are harder to come by on LinkedIn, since fewer medical professionals use this platform. However, you can look at peoples’ resumes as a source of inspiration. This is useful to understand the experiences that they have had in order to get to where they are today. You could always reach out to people and companies/ organisations for more information and advice.

TIP 5: JOIN A PRE-PLANNED RESEARCH PROJECT

Researchers advertise research opportunities on websites and via societies and organisations such as https://www.remarxs.com and http://acamedics.org/Default.aspx .

TIP 6: JOIN A RESEARCH COLLABORATIVE

Research collaboratives are multiprofessional groups that work towards a common research goal. These projects can result in publications and conference presentations. However, more importantly, this is a chance to establish excellent working relationships with like-minded individuals.

Watch out for opportunities posted on Student Training and Research Collaborative .

Interested in academic surgery? Consider joining StarSurg , BURST Urology , Project Cutting Edge or Academic Surgical Collaborative .

Got a thing for global health? Consider joining Polygeia .

TIP 7: THE iBSc YEAR: A STEPPING STONE INTO RESEARCH

At UCL you will complete an iBSc in third year. This is often students’ first taste of being involved in research and practicing academic writing – it was for me. The first-ever project that I was involved in was coding data for a systematic review. One of the Clinical Teaching Fellows ended the tutorial by asking if any students would be interested in helping with a research project. I didn’t really know much about research at that point and was curious to learn, so I offered to help. Although no outputs were generated from that project, I gained an understanding of how to conduct a systematic review, why the work that I was contributing to was important, and I learnt a thing or two about neonatal conditions.

TIP 8: VENTURE INTO ACADEMIC PUBLISHING

One of the best ways to get a flavour of research is to become involved in academic publishing. There are several ways in which you could do this:

Become a peer reviewer. This role involves reading manuscripts (papers) that have been submitted to journals and providing feedback and constructive criticism. Most journals will provide you with training or a guide to follow when you write your review. This will help you develop skills in critical appraisal and how to write an academic paper or poster. Here are a few journals which you can apply to:

- https://thebsdj.cardiffuniversitypress.org

- Journal of the National Student Association of Medical Researchjournal.nsamr.ac.uk

- https://cambridgemedicine.org/about

- https://www.bmj.com/about-bmj/resources-reviewers

Join a journal editorial board/ committee. This is a great opportunity to gain insight into how a medical journal is run and learn how to get published. The roles available depend on the journal, from Editor-in-Chief to finance and operations and marketing. I am currently undertaking a Social Media Fellowship at BJGP Open, and I came across the opportunity on Twitter! Here are a few examples of positions to apply for:

- Journal of the National Student Association of Medical Researchjournal.nsamr.ac.uk – various positions in journalism, education and website management

- https://nsamr.ac.uk – apply for a position on the executive committee or as a local ambassador

- Student BMJ Clegg Scholarship

- BJGP Open Fellowships

TIP 9: GAIN EXPERIENCE IN QUALITY IMPROVEMENT

UCL Be the Change is a student-led initiative that allows students to lead and contribute to bespoke QIPs. You will develop these skills further when you conduct QIPs as part of your year 6 GP placement and as a foundation year doctor.

TIP 10: CONSIDER BECOMING A STUDENT REPRESENTATIVE

You’ll gain insight into undergraduate medical education as your role will involve gathering students’ feedback on teaching, identifying areas of curriculum that could be improved and working with the faculty and other student representatives to come up with solutions.

It may not seem like there are any research opportunities up for grabs, but that’s where lateral thinking comes into play: the discussions that you have with your peers and staff could be a source of inspiration for a potential medical education research project. For example, I identified that, although we have lectures in nutrition science and public health nutrition, there was limited clinically-relevant nutrition teaching on the curriculum. I then conducted a learning needs assessment and contributed to developing the novel Nutrition in General Practice Day course in year 5.

Thanks for reaching the end of this post! I hope my Top 10 Tips are useful. Remember, research experience isn’t essential to become a great doctor, but rather an opportunity to explore a topic of interest further.

One thought on “Top 10 Tips: Getting into Research as a Medical Student”

This article was extremely helpful! Alothough, I’m only a junior in high school I have a few questions. First, is there anyway to prepare myself mentally for this challenging road to becoming a doctor? check our PACIFIC best medical college in Rajasthan

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Copyright © 2018 UCL

- Freedom of Information

- Accessibility

- Privacy and Cookies

- Slavery statement

- Reflect policy

Please check your email to activate your account.

« Go back Accept

Medical Research

How to conduct research as a medical student, this article will address how to conduct research as a medical student, including details on different types of research, how to go about constructing an idea and other practical advice., kevin seely, oms iv.

Student Doctor Seely attends the Rocky Vista University College of Osteopathic Medicine.

In addition to good grades, test performance, and notable characteristics, it is becoming increasingly important for medical students to participate in and publish research. Residency programs appreciate seeing that applicants are interested in improving the treatment landscape of medicine through the scientific method.

Many medical students also recognize that research is important. However, not all schools emphasize student participation in research or have associations with research labs. These factors, among others, often leave students wanting to do research but unsure of how to begin. This article will address how to conduct research as a medical student, including details on different types of research, how to go about constructing an idea, and other practical advice.

Types of research commonly conducted by medical students

This is not a comprehensive list, but rather, a starting point.

Case reports and case series

Case reports are detailed reports of the clinical course of an individual patient. They usually describe an unusual or novel occurrence or provide new evidence related to a specific pathological entity and its treatment. Advantages of case reports include a relatively fast timeline and little to no need for funding. A disadvantage, though, is that these contribute the most basic and least powerful scientific evidence and provide researchers with minimal exposure to the scientific process.

Case series, on the other hand, look at multiple patients retrospectively. In addition, statistical calculations can be performed to achieve significant conclusions, rendering these studies great for medical students to complete to get a full educational experience.

Clinical research

Clinical research is the peak of evidence-based medical research. Standard study designs include case-controlled trials, cohort studies or survey-based research. Clinical research requires IRB review, strict protocols and large sample sizes, thus requiring dedicated time and often funding. These can serve as barriers for medical students wanting to conduct this type of research. Be aware that the AOA offers students funding for certain research projects; you can learn more here . This year’s application window has closed, but you can always plan ahead and apply for the next grant cycle.

The advantages of clinical research include making a significant contribution to the body of medical knowledge and obtaining an understanding of what it takes to conduct clinical research. Some students take a dedicated research year to gain experience in this area.

Review articles

A literature review is a collection and summarization of literature on an unresolved, controversial or novel topic. There are different categories of reviews, including meta-analyses, systematic reviews and traditional literature reviews, offering very high, high and modest evidentiary value, respectively. Advantages of review articles include the possibility of remote collaboration and developing expertise on the subject matter. Disadvantages can include the time needed to complete the review and the difficulty of publishing this type of research.

Forming an idea

Research can be inspiring and intellectually stimulating or somewhat painful and dull. It’s helpful to first find an area of medicine in which you are interested and willing to invest time and energy. Then, search for research opportunities in this area. Doing so will make the research process more exciting and will motivate you to perform your best work. It will also demonstrate your commitment to your field of interest.

Think carefully before saying yes to studies that are too far outside your interests. Having completed research on a topic about which you are passionate will make it easier to recount your experience with enthusiasm and understanding in interviews. One way to refine your idea is by reading a recent literature review on your topic, which typically identifies gaps in current knowledge that need further investigation.

Finding a mentor

As medical students, we cannot be the primary investigator on certain types of research studies. So, you will need a mentor such as a DO, MD or PhD. If a professor approaches you about a research study, say yes if it’s something you can commit to and find interesting.

More commonly, however, students will need to approach a professor about starting a project. Asking a professor if they have research you can join is helpful, but approaching them with a well-thought-out idea is far better. Select a mentor whose area of interest aligns with that of your project. If they seem to think your idea has potential, ask them to mentor you. If they do not like your idea, it might open up an intellectual exchange that will refine your thinking. If you proceed with your idea, show initiative by completing the tasks they give you quickly, demonstrating that you are committed to the project.

Writing and publishing

Writing and publishing are essential components of the scientific process. Citation managers such as Zotero, Mendeley, and Connected Papers are free resources for keeping track of literature. Write using current scientific writing standards. If you are targeting a particular journal, you can look up their guidelines for writing and referencing. Writing is a team effort.

When it comes time to publish your work, consult with your mentor about publication. They may or may not be aware of an appropriate journal. If they’re not, Jane , the journal/author name estimator, is a free resource to start narrowing down your journal search. Beware of predatory publishing practices and aim to submit to verifiable publications indexed on vetted databases such as PubMed.

One great option for the osteopathic profession is the AOA’s Journal of Osteopathic Medicine (JOM). Learn more about submitting to JOM here .

My experience

As a second-year osteopathic medical student interested in surgery, my goal is to apply to residency with a solid research foundation. I genuinely enjoy research, and I am a member of my institution’s physician-scientist co-curricular track. With the help of amazing mentors and co-authors, I have been able to publish a literature review and a case-series study in medical school. I currently have some additional projects in the pipeline as well.

My board exams are fast approaching, so I will soon have to adjust the time I am currently committing to research. Once boards are done, though, you can bet I will be back on the research grind! I am so happy to be on this journey with all my peers and colleagues in medicine. Research is a great way to advance our profession and improve patient care.

Keys to success

Research is a team effort. Strive to be a team player who communicates often and goes above and beyond to make the project a success. Be a finisher. Avoid joining a project if you are not fully committed, and employ resiliency to overcome failure along the way. Treat research not as a passive process, but as an active use of your intellectual capability. Push yourself to problem-solve and discover. You never know how big of an impact you might make.

Disclaimers:

Human subject-based research always requires authorization and institutional review before beginning. Be sure to follow your institution’s rules before engaging in any type of research.

This column was written from the perspective from a current medical student with the review and input from my COM’s director of research and scholarly activity, Amanda Brooks, PhD.

Related reading:

H ow to find a mentor in medical school

Tips on surviving—and thriving—during your first year of medical school

A worthwhile jugging act

From diapers to degrees: parenting through medical school and residency, forrest 'phog' allen, do: the father of basketball coaching, ‘let your light so shine … ‘, the 4th wave of osteopathic medicine: re-establishing osteopathic distinctiveness, mental health, confronting burnout and moral injury in medicine, osteopathic history, how 19th-century news coverage helped shape the early years of osteopathic medicine, more in training.

Free webinar for graduating medical students will share strategies on reducing student loan debt

Presented by Student Loan Professor, the April 9 webinar will provide attendees with expert tips on saving money, relieving financial stress and managing their student loans.

Is it ever too late to attend medical school? A nontraditional student shares her thoughts

Yasi Arabi, OMS III, has advised many students who are concerned that age may be a barrier to attending med school. Here’s what she tells them.

Previous article

Next article, one comment.

Thanks! Your write out is educative.

Leave a comment Cancel reply Please see our comment policy

A Penn State Nittany Lion statue is seen in the courtyard of Penn State College of Medicine in Summer 2016. The statue is in focus toward the right side of the image. Out of focus in the background, green plants and trees are visible in the courtyard.

Medical Student Research

George Harrell, MD, the founding dean of Penn State College of Medicine, established the Medical Student Research (MSR) program as an integral part of this medical school’s curriculum. It is a requirement for the MD degree.

The MSR program gives each medical student an opportunity to participate in mentored medical research. Students gain an understanding of the research process, limitations and variability of data, and an application of research to clinical practice. Projects may be in the clinical, social or basic medical sciences and may be conducted on campus or at off-campus sites, nationally or internationally.

Faculty looking for information about the MSR project, including adding projects to the list for students and work-study, should see the MSR page on the Faculty and Staff website .

Contact Information

Ira Ropson, PhD Assistant Dean of Medical Student Research Associate Professor, Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Penn State College of Medicine Room C5716D 717-531-4064 [email protected]

Nicole Vasquezi-Rode Assistant Director, Medical Student Research Program Penn State College of Medicine Office of Medical Education [email protected]

Jump to topic

Jan. 17, 2024 – MSR Final Reports due

Jan. 17, 2025 – MSR Final Reports due

Jan. 16, 2026 – MSR Final Reports due

March 15, 2024 – Summer Translational Science Fellowship (TSF) application and proposal due (See details via Penn State Clinical and Translational Science Institute , which operates this program)

April 4, 2024 – MSR Scholarship applications due (an MSR Proposal and CV must also be submitted in order to be considered)

April 26, 2024 — Work Study Deadline for student and departmental paperwork

June 10, 2024 – MSR Proposals due for those conducting research during the summer of 2024 (For Federal Work Study Students)

Jan. 15, 2027 – MSR Final Reports Due

MSR Overview

The easiest way to identify an on-campus adviser would be to choose someone who is familiar with the kind of work you will be doing at an external institution (someone who can actually advise you, for example, on whether you are taking on a manageable role in a project, or whether your effort is suitable for an MSR). If you already have someone you work closely with here, and they are comfortable serving this additional role, that is also fine.

Projects may be performed at any qualified facility, as long as this is defined in the proposal and approved by the Committee. when an off-campus research adviser will be responsible for the actual supervision of the project, the student must also have an on-campus sponsor (this can be your academic adviser); the role of the on-campus sponsor is to help ensure that your project will meet the MSR requirements, and serve as a first point of contact if your research adviser has questions.

Note that if your project involves human subjects in any way, then human subjects research approval is required from the IRB at the research site, AND from the Penn State College of Medicine IRB. You will need to provide the IRB abstract from your research adviser and a copy of your sponsor’s approval letter to our IRB for approval. Approval MUST be granted by the University IRB before beginning involvement with the human subjects as part of MSR.

You can find more about human subjects in the MSR Guidelines .

Your research adviser is the person who has expertise in your chosen area of research, and who actually provides day-to-day supervision of your research project.

Human Subjects

Human research is any interaction with humans that involves data collection and analysis. This includes questionnaires, surveys, interviews, focus groups, etc., as well as scientific studies of normal or abnormal physiology and development, studies that evaluate the safety, effectiveness, or usefulness of a medical product, procedure, or intervention, and studies that involve any invasive procedures. Any research in medical education that you intend to report publicly (for example, in an MSR Final Report) requires IRB approval.

The IRB must review and approve research conducted outside the United States of America by PSU employees or students, even if the foreign research receives no U.S. governmental funding. Such collaborative research activities must meet ethical standards similar to those required at PSU. The IRB may approve such research, provided it determines that

- the research conforms to proper codes of ethics (e.g., the Declaration of Helsinki or the Belmont Report) and

- the research is approved by the local ethical review authority.

Requirements for the informed consent process will follow the laws and customs of the country in which the research is being conducted. If a U.S. department or agency funds the research, then it is probable that the foreign research site will need to file a Federal Wide Assurance (FWA) application through OHRP.

Guidance on important IRB issues in international human subjects research can be found in the University Park Office of Research Protections “ Guideline II, International Research Involving Human Participants .”

Academic credit is available, but not required, when a student uses specific elective time to conduct their research. To obtain academic credit, the student should register for course “Subject 596 Individual Studies” in basic science departments or “Subject 796 Individual Studies” in clinical departments. The number of credits will be determined by the sponsor and will depend on the number of hours committed to the project.

Data acquisition and data reduction for a MSR project while abroad requires a considerable time commitment to the research project on the part of the student. While Penn State supports students spending time abroad in clinical settings to acquire international perspectives on health care, it is very difficult for a student to do an international clinical rotation and an acceptable MSR project simultaneously.

The decision to pay you while working on your MSR project is at the discretion of your research supervisor. Research funding is extremely difficult to obtain, and research supervisors may not have research funds to pay you. Students working on their MSR project typically are working on their project full-time during the summer after the first year of medical school. Most projects at Penn State can be supported by federal work study positions for summer work, but both you and your adviser must fill out forms by April 1 to qualify. Work study funds will pay for three-quarters of the salary of a student. The department or adviser is responsible for the remainder. Research at sites other than Penn State cannot be supported by work study. Students may not be paid while enrolled in research electives for academic credit.

It depends. If you are the first author of the paper, you may submit the reprint or manuscript. If you are not the first author, you will need to also submit an MSR Final Report that describes your contribution to the overall work.

Congratulations! Having your work selected for national exposure is a true honor.

We have a limited amount of Travel Funds that are available to assist with expenses for medical students traveling to present at a conference. Information and guidelines are found under Funding and Awards .

It is not required that your research be published (although that is often a frequent outcome that we strongly encourage!). Your participation should be at a level that you would be a co-author should it be published.

MD Students

- 2023-2024 Handbook

- Careers in Medicine

- Medical Student Performance Evaluation

- Course Information

- Fourth-Year Electives

- Student Profile

- Community Service

- Competencies and Subcompetencies for Graduation

- Health Systems Science

- Hershey Curriculum

- Hershey Accelerated Curriculum

- Medical Students as Educators

- Patient Experience

- Poster Symposium 2021

- Criminal Background Check Requirements

- Financial Aid

- MD/PhD Student Information

- Finding A Project

- Funding and Awards

- Past MSR Projects

- Outstanding Research Awards

- Enrollment Verification

- Phases III & IV

- Student Groups

- MD Student Forms

- Reporting Immunizations

- Blood-Borne Pathogen Policy

- Health Care

- Sharps Injury Procedures

- Travel Health Preparation

- Cognitive Skills Program

- Office for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion

- Office for a Respectful Learning Environment

- Office for Professional Mental Health

- Global Health & Health Equity Pathway (GHHEP): Health Equity Scholars (Domestic)

- Scholarships

- Mark J. Young International Health Policy Scholarship

Medical Student Research

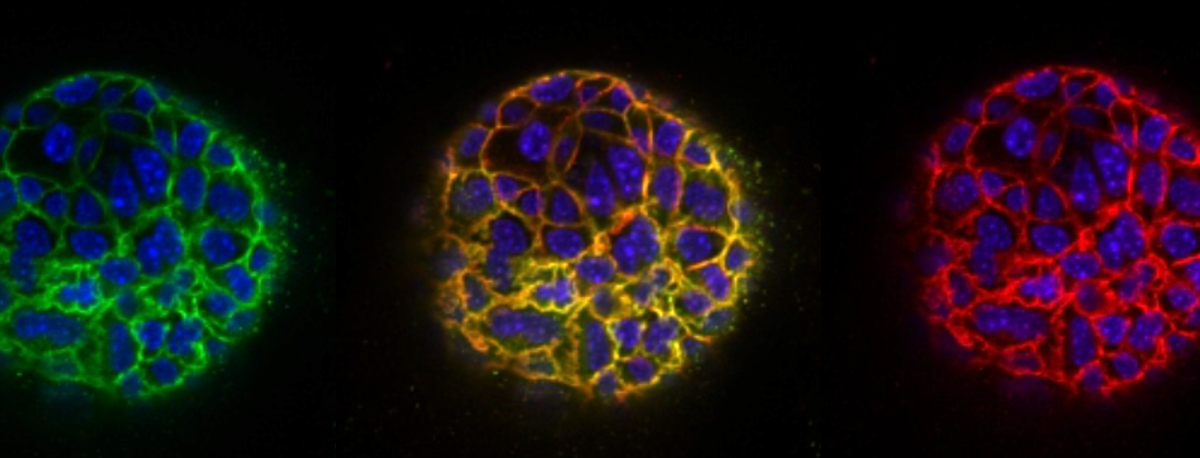

Medical research informs everything we do in medicine. Basic research helps us understand how the human body works at the molecular and cellular levels. Applied research in the lab gives rise to potential new diagnostic and therapeutic modalities. Clinical research tells us what medical interventions work and do not work in humans. Health services research helps us understand the best way to deliver medical care, including ongoing issues with health disparities. Quality improvement research helps make our care better. Epidemiologic research, population health research, and health policy research guide us in the realm of public health. And finally, medical education research helps us understand the best way to teach the next generation of doctors. Translational research and dissemination and implementation science bring these different research approaches together to bridges the gap from bench to bedside..

Given the importance of research within the medical profession, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine requires a mentored research project and associated written MD Thesis to graduate. All areas of exploration on the biomedical research spectrum, detailed above, are open for these projects. The Office of Medical Student Research is committed to helping you have a productive and positive experience, whatever your previous research background. We have numerous resources available, including a needs assessment delivered to all incoming medical students, in-person workshops, online learning modules, an easy-to-use website that links faculty research mentors and interested students together, and a dedicated faculty and staff team give you individualized support through the research process.

Being involved in research during medical school will help you in your career at every stage, including residency, fellowship, and beyond. Understanding medical research—what it is, how it is done, what it shows us and its limitations—allows you to practice both the science and art of medicine after graduation and beyond, whether you are doing the research yourself in an academic setting or serving patients or communities. Research can also be personally rewarding, opening doors to travel, collaboration, and lifelong learning.

If you are a CWRU faculty member interested in being a medical student research mentor, please click on the ‘Submit a Project’ link and take a few minutes to enter one or more projects that would be applicable to medical students. If you have many projects, enter your research interests and contact information and indicate that students should contact you. As of 2023, the large majority of required medical student research occurs over 12 weeks of summer. Many students continue the same project or join another one beyond this required experience. You can submit projects that are appropriate for either timeline.

If you are a current CWRU medical student, please click on the ‘Search for Project’ link to search the database for potential research mentors and projects. This requires CWRU single sign-on.

We also keep a partial list of potential student research opportunities external to CWRU, of which we are aware. Click on the ‘External Research Opportunities’ link to explore these.

If you need help or want more information, please email [email protected].

Rosa K Hand, PhD, RDN, LD, FAND

Associate Professor, Nutrition Director, Medical Student Research & Scholarship

Sharon Callahan Administrative Director, Medical Student Research & Scholarship

Research Opportunities for Medical Students

Programs for um som students.

The University of Maryland School of Medicine (UM SOM) and the Office of Student Research (OSR) are pleased to offer several programs for our students to conduct research with leading physicians and scientists. These programs may help students fulfill their FRCT Scholarly Project requirements.

The following programs are sponsored by, or in partnership with, UM SOM and are only available to current UM SOM students.

Program for Research Initiated by Students and Mentors (PRISM)

PRISM provides UM SOM students with a paid, 9-week, full-time immersive experience as well as a stipend. Students participate in structured enrichment programming, including interactive seminars led by scientists and physician scientists and learning modules and workshops on key aspects of research and on select research fields.

Alpha Omega Alpha (AOA) Carolyn L. Kuckein Student Research Fellowship

Designed to foster the development of the next generation of medical researchers, the Carolyn Kuckein Student Research Fellowship will provide financial support for research to be conducted either full time during a period of 8 to 10 weeks, or part-time over a period of 1 to 2 years.

University of Maryland School of Medicine Summer Fellowship in Radiation Oncology

The Department of Radiation Oncology has multiple paid 10-week research fellowships available for 1st and 2nd year medical students. Students will complete a research project in radiobiology, clinical radiation oncology, or physics, with the goal of securing a publication or national presentation.

MPower University of Maryland Scholars Program for UMB Students

This MPower mentored program matches University of Maryland, Baltimore (UMB) students with top faculty members at the University of Maryland, College Park (UMCP) who have interesting research projects. Entry to the program is highly competitive; accepted students receive a stipend to conduct research at UMCP for ten weeks over the summer.

Research Electives & Extended Research

MSIII and MSIV students can request approval to execute a one- or two-month research elective or an extended research elective. Research electives provide students with the opportunity to engage in new research or dedicate more time to research projects with which they were already engaged.

MD/Masters Dual Degree Programs

We offer specialized training in seven different dual degree programs (and more to come). Several dual degree programs allow students to complete a thesis in clinical research (MD/MS Clinical Research), basic or translational research (MD/MS Cellular & Molecular Biomedical Science), or biomedical engineering-related research (MD/MS in Bioengineering).

Programs for all Medical Students

The following programs are open to both UM SOM medical students and medical students outside the University of Maryland system.

CGE Listing of Global Opportunities

The Center for Global Engagement provides resources for students searching for global health opportunities including a listing of internal and external grants and travel awards. Visit their website for more information.

Boston University Medical Student Research

There are numerous opportunities for medical students to engage in mentored research projects at boston university chobanian & avedisian school of medicine. we are here to help connect you to these resources., medical student research opportunities @ bu chobanian & avedisian school of medicine.

My Research @ BU Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine

Piers Klein is working under the mentorship of Dr. Thanh Nguyen and Dr. Mohamad Abdalkader in the departments of Neurology and Radiology at Boston Medical Center and the Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine. His research focuses on the epidemiology, diagnosis, medical and interventional treatment of cerebrovascular disease.

Research Opportunities

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J R Soc Med

- v.101(3); 2008 Mar 1

Involving medical students in research

Undergraduate research is not a new phenomenon in medicine. Charles Best was a medical student at the time that he and his supervisor, Frederick Banting, discovered insulin. Insulin arises from the pancreatic islets of Längerhans, themselves discovered in 1869 by medical student Paul Längerhans. In biomedical research, Alan Hodgkin, formerly professor of biophysics at the University of Cambridge, won the Nobel Prize in 1972 for work on nerve transmission that he began as an undergraduate.

Medical student research can be mandatory, elective or extracurricular. In Germany, medical school graduates practice medicine but cannot assume the title ‘Doctor’ until they have submitted a thesis. As a result, around 90% of practicing German physicians have undertaken a period of research. 1 Although research is usually voluntary for UK medical students, there is increasing undergraduate interest in research and publication. The 2007 MTAS form, for example, awards credit to medical graduates for a first author paper in a peer-reviewed journal.

The GMC document Tomorrow's Doctors states that medical school graduates must be able to ‘critically evaluate evidence’ and ‘use research skills to develop greater understanding and to influence their practice’. 2 It has been suggested that a period of research might help fulfill this requirement of new doctors. 3 , 4 Despite this possibility, medical students have only limited opportunities to pursue original research. However, a number of institutions offer intercalated degree courses in which students suspend their medical training to undertake a second degree, often with a strong research component. These attract around a third of UK medical students each year. 5 , 6

Reasons for medical students choosing to intercalate are varied and include improving their long-term career prospects as well as establishing a broad knowledge base. 6 The opportunity to conduct original research is, however, less frequently given as a reason for pursuing an intercalated degree. 5 , 6 In addition, two thirds of new doctors in the UK have not undertaken an intercalated degree 5 , 6 and may graduate without experiencing research. A number of barriers explain the reluctance of medical students to intercalate. One survey found the most common reasons were financial constraints, lack of interest, and reluctance to prolong medical training. 6

Nevertheless, there are many benefits of undergraduate participation in research. For example, student researchers can greatly increase the publication output of their medical school. Academic supervisors at one German institution have reported that students appear as co-authors on approximately 28% of papers published in Medline-indexed journals. 8

Research experience may also boost the career profile of graduating medical students. When a cohort of students at the Stanford University School of Medicine was encouraged to participate in research, 75% gained authorship of a paper and 52% presented data to a national conference. 3 In Germany, around 66% of medical students obtain a Medline-indexed publication before qualifying. This does not include data presented to meetings or published in peer-reviewed journals not indexed by Medline. 8

In addition to boosting graduate employability, publication as an undergraduate can have long-term career implications for doctors. For example, one survey of academic physicians found that career success is independently associated with having conducted research as a student. 9 In addition, physicians who undertook extracurricular research at medical school produced four times as many publications as their peers. 10

Undergraduate research may also provide a solution for countries in which academic medicine is experiencing a crisis in recruiting postgraduate clinical researchers. 11 For example, a survey of medical student researchers found that 75% were motivated to pursue further research and 60% aspired to a full-time academic career. 3

Those students not considering research careers may nevertheless develop skills transferable to clinical practice. In particular, medical student research may help instil a culture of evidence-based medicine (EBM) in clinical medicine. According to one author, ‘the practice of EBM is not a “behaviour”… it is an internalized spirit of enquiry born of a deep understanding… of the value and the limitations of biomedical research’. 5 Indeed, there is evidence to suggest that research experience as an undergraduate may foster this ‘deeper understanding’. 3–5 According to one survey, American medical students participating in research found that the experience ‘taught them to ask questions, review the literature critically, and analyse data’. 3 Students undertaking a mandatory literature review further developed ‘critical appraisal, information literacy, and critical thinking skills’ and the opportunity to make ‘contacts for postgraduate training’. 4

Despite these apparent benefits, there are objections to involving undergraduates in research. Intensive projects may, for example, disrupt the progress of students through the core medical curriculum. Similarly, supervision requirements may distract faculty members from their own clinical and research commitments. However, students do not have to run a clinical trial to learn about the research process. If there are not pre-existing clinical projects suitable for student participation, undergraduates might be involved in critically appraising literature for a review article, or preparing patient case reports for publication. Projects such as these require little supervision while still immersing students in the research culture of their profession.

In summary, research opportunities for medical students are often confined to intercalated degree courses; potentially increasing financial burden, prolonging the curriculum and delaying clinical experience. As a result, around two thirds of medical students eschew the opportunity to intercalate 5 , 6 and miss out on conducting original research. Nevertheless, the benefits of student participation in research are well-documented for graduates, institutions and the academic community as a whole. 3–5 , 7–10 As a result, senior doctors should strongly consider involving motivated students in elective or extracurricular research projects. Furthermore, medical educators should recognize the value of student research and incorporate opportunities into the curriculum wherever practicable. Only in these ways can we secure a future for academic medicine and foster a genuine respect for EBM in tomorrow's doctors.

DECLARATIONS —

Competing interests DM is an undergraduate medical student and Editor of Reinvention: A Journal of Undergraduate Research . He has received research funding from the Reinvention Centre for Undergraduate Research at the University of Warwick and Oxford Brookes University

Funding None

Ethical approval Not applicable

Guarantor DM

Contributorship DM is the sole contributor

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Mina Aletrari for reviewing earlier drafts of this paper

University of South Florida

Main Navigation

Health news.

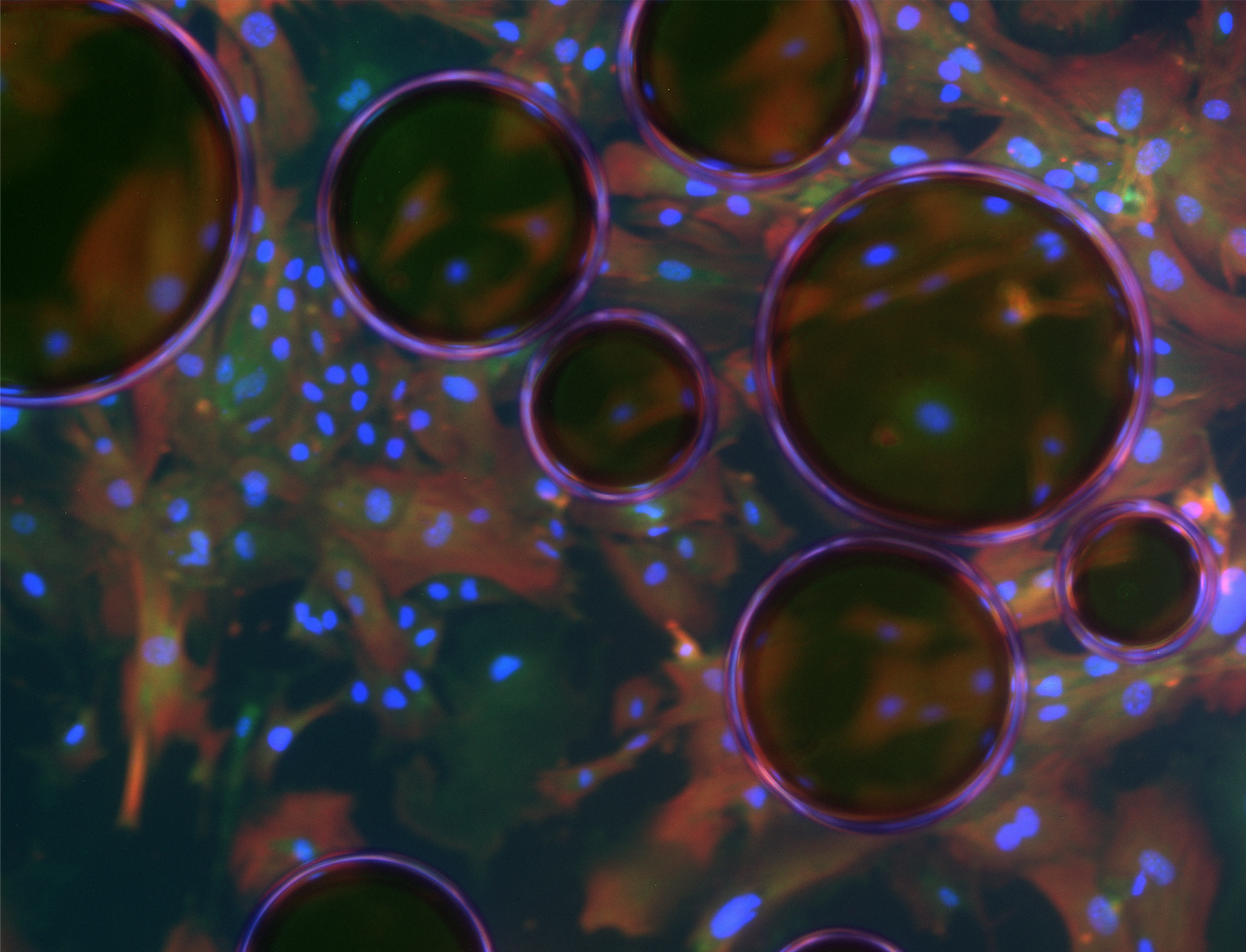

Image from USF Health Research Day 2024.

Research outcome teams enhance research opportunities at MCOM

- Story and photos by Freddie Coleman

- March 28, 2024

Morsani College of Medicine , Research

In an effort to enhance and expand the research capacity, and accommodate the increasing number of students conducting research, the USF Health Morsani College of Medicine Office of Research, Innovation & Scholarly Endeavors (RISE) created Specialty-Specific Research Outcomes Teams (SSROT).

These ‘vertical learning’ teams, specialty-specific teams, match medical students with resident physicians, fellows in training, and attending physicians on faculty at MCOM. This network better defines and sustains a pipeline of impactful research opportunities as well as invaluable mentorship.

Rahul Mhaskar, MD, PhD, professor and associate dean of medical student research for the Morsani College of Medicine, spearheaded in 2020 the concept of a more collaborative research environments with more students and physicians with similar research interests.

SSROTs have been instrumental in helping medical students gain access to research opportunities. Since 2018, 95% of MCOM medical students have engaged in scholarly work during their medical school tenure. SSROT’s have led to a sharp increase in medical students presenting at national and international meetings, and authoring peer-reviewed publications.

Benefits of medical student research experience:

- Higher first-choice match rate for senior medical students

- Higher number of competitive residency applicants

- Increased number of first-author publication

- Incremental increases in funding for research

Rahul Mhaskar, MD, PhD, professor and associate dean of medical student research for the USF Health Morsani College of Medicine.

RISE helps the attending physicians, residents, and fellows design projects. Then, they help match medical students to the projects based on interest. This concept has led to a sharp increase in the number of awards and authorships for medical students.

In 2023-2024, medical students reported 357 first-author abstracts, 196 peer-reviewed manuscripts, and 87 awards.

For medical students, residents, and fellows, SSROTs offer an opportunity to resume building, and overall broadening and enhancing the medical school experience. Sarah Alfieri, a third-year medical student in the Surgery Research Outcome Team (SORT), has been involved with the surgery SSROT since her first year. The experiences and knowledge she’s gained from physicians and more senior medical students helped shape her path through medical school, she said. She recently received her first first-author publication in the Journal of Global Surgical Education on her research exploring a transition to practice curriculum for surgery residents as a guide to early career success.

“It can be challenging early for new medical students to get involved because most students don’t have the knowledge base needed. But, once a student gets on a project, the knowledge and experience gained from learning from physicians and senior medical students was invaluable,” Alfieri said.

Alfieri said flexibility is also an added benefit to being part of an SSROT. Students can pick and choose the projects they wish to be part of, which is important when balancing a rigorous medical school schedule and conducting research.

Research experience on a residency application could be the difference in helping a medical student match to their top residency choice. Karim Hanna, MD, MCOM class of 2014 alumni, associate professor in the USF Department of Family Medicine, and lead physician of the A.I. in Medicine research outcome team, said the landscape of medical school and the level of competitiveness has drastically changed for the better, since when he was a medical student nearly 15 years ago. USF Health has always fostered an environment of mentoring medical students. Research outcome teams allow for that mentoring to be done in a team environment where ideas can be passed around, and new collaborations can be formed with the guidance and resources in place to help medical students be more successful.

“Fifteen years ago, it was rare to see a medical student with any publications,” Dr. Hanna said. “These days, it seems that publications are needed to stay competitive. The students push us as much as we push them. As clinicians, we need to know that we’re doing more than just coming in and seeing patients. It’s about building the academic environment for our students.”

In the future, Dr. Mhaskar looks to continue building the capacity of research opportunities for medical students and, eventually, into the larger research mission of USF Health. He is currently working to increase the offerings within MCOM. SSROTs in anesthesiology, medical education, radiation oncology, and trauma surgery are the next likely teams to be established.

Dr. Mhaskar said the next evolution of the concept is creating interdisciplinary teams, allowing USF Health students from different colleges to collaborate on research projects using the SSROT model.

Current SSROT offerings and attending physician leads:

- General Surgery – Christopher Ducoin, MD

- Vascular Surgery – K. Dean Arnaoutakis, MD, MBA

- Ear, Nose, and Throat – Matthew Mifsud, MD

- Neurosurgery – Siviero Agazzi, MD, Maxim Mokin, MD, PhD

- Internal Medicine – Shanu Gupta, MD, FACP; Sherri Huang, MD, PhD (med/peds resident)

- Family Medicine (A.I. focus) – Karim Hanna, MD

- Pulmonary & Critical Care Medicine – William Miller, MD

Return to article listing

Explore More Categories

- College of Nursing

- College of Public Health

- Honors & Awards

- MS/PhD Program Research Degrees

- Morsani College of Medicine

- Patient Care

- Physical Therapy

- Taneja College of Pharmacy

About Health News