Skip navigation

- Log in to UX Certification

World Leaders in Research-Based User Experience

Diary studies: understanding long-term user behavior and experiences.

March 29, 2024 2024-03-29

- Email article

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Twitter

In This Article:

Defining diary studies, when to conduct a diary study, how data is gathered, the diary-study timeline, data analysis.

A diary study is a qualitative user research method used to collect insights about user behaviors, activities, and experiences over time and in context.

During a diary study, participants report their interactions and experiences as they occur over a period ranging from a few days, weeks, to a month or longer.

For example, in a diary study investigating how nurses interact with patient health records in a hospital setting, we may ask nurses to log all their activities involving health records.

Collecting contextual , self-reported insights from participants over time makes diary studies great for understanding how users behave within the context of their everyday lives.

Diary Studies vs. Field Studies and Contextual Inquiries

Like field studies and contextual inquiries, diary studies are a type of context method . All these methods are used to understand users’ contexts and environments. However, field studies and contextual inquiries involve directly observing users, usually in person, and can be costly.

In contrast, diary studies are done remotely and asynchronously, allowing researchers flexibility and access to distributed users. Diary studies can often be conducted at a lower cost than field studies or contextual inquiries.

Diary Studies vs. User Interviews and Usability Testing

Contextual and longitudinal insights cannot be collected through single-session moderated user-research methods, like usability testing or user interviews. These types of methods typically remove users from their personal context and take place over a short time.

Diary studies are useful for exploring a wide variety of research questions about long-term experiences and repetitive activities. You might decide to conduct a diary study when you have research questions about the following aspects of an experience.

The focus of a diary study can range from very broad to extremely targeted , depending on the topic being studied. Diary studies are often focused on one of the following:

- Broad behaviors

- Targeted product usage

- Targeted activities

Diary Studies with Broad Behavioral Focus

Researching general activities or behaviors helps researchers understand users’ mindsets, mental models, habits, and strategies.

Example: How do people use intelligent assistants like Amazon Alexa or Google Assistant?

Diary Studies Focused on Targeted Product Usage

Studying users’ interactions with a particular product over time gives insights into their motivations, usage patterns, and comprehensive experience using that product.

Example: How do people use a specific meal-delivery application in their everyday lives, and what is their overall experience and perception of using it?

Diary Studies Focused on a Targeted Activity

Targeted research around specific activities that take place over time helps researchers understand how users approach broad goals that often include multiple interactions.

Example: How do customers go about researching and purchasing a new mobile phone plan?

These types of diary studies may target activities involving one particular product or service or may focus on how users approach long-term activities in the larger marketplace.

Diary studies get their name from the way this type of research was traditionally conducted. Research participants were asked to keep a physical diary, documenting relevant behaviors and experiences during a defined period of time.

Today, we have access to a host of digital tools that can make running diary studies much more efficient for both participants and researchers. However, the underlying method is still the same. Participants are asked to log specific information about activities being studied.

Selecting the right tool(s) for data collection is a decision that should be made based on a variety of factors. We discuss tool selection in detail later in this article. However, one of the primary considerations in tool selection will be driven by your research questions and the focus of your study.

Due to the long-term nature of diary studies and the added complexity of directing participants on how to share insights, these studies require substantial planning and preparation.

After defining the goals of the study, you will need to consider a few important aspects (and document them in your study plan):

- When Participants Should Create Diary Entries

- Length of the diary study

- Number of participants and their profile

- Incentives and response requirements

- Communication templates and supporting materials

- Pilot study

- Pre-study brief

- Post-study interview

1. When Participants Should Create Diary Entries

There are three common methods for gathering insights during diary studies: event-based, interval-based, and signal-based. Each study's unique research goals, questions, and focus will help researchers determine the best method for gathering information from participants. Many studies use a combination of these methods.

2. Length of Diary Study

Consider for how long you will need participants to report their interactions. The length of a diary study should depend on:

- Your research questions

- What behavior you’re trying to capture

- How frequently these behaviors might happen

- How long it takes typical users to complete a longitudinal activity

You may need to do some exploration to understand the typical frequency or length of activities, but ultimately, the reporting period you select should be one that will give you enough data points across your whole participant sample.

3. Number of Participants and Their Profile

Consider who and how many participants should be part of your study. Your participants’ typical behaviors should match what you’re looking for in the study.

For example, a study about food-delivery applications may need to involve participants who use such applications several times a week.

Because a diary study takes place over a longer time than a regular usability-testing study, there is a higher chance that participants will drop out of the study due to unexpected circumstances in their lives. Consider overrecruiting in preparation for potential dropouts so that you have enough data points in the end.

Also, consider how many participants will give you enough data to answer your research questions. You want enough participants to reach saturation — that is enough data to ensure your themes will be well established.

Saturation refers to a moment in qualitative research when your data becomes repetitive — you hear the same thing again and again. After this point, there is a diminishing return with any additional participants. In a diary-study context, saturation happens when additional data no longer changes your understanding of the behaviors you’re studying but instead reinforces the themes you’ve already identified.

The best sample size to reach saturation depends on how broad your research questions or the problem space are and on how varied or homogenous your target user group is. The more variety in your user group, the more participants you will need to recruit to get a representative mix of users. And, the broader the research questions, the more people you will need to recruit to ensure enough insight coverage across all questions.

Below we outline some rough guidelines for sample sizes based on these criteria.

4. Incentives and Response Requirements

Be clear and specific about what participants need to do in your diary study so that people understand what is expected of them and you get the data that you need.

It’s useful to designate a minimum number of responses you expect from participants in exchange for the study incentive. However, this minimum should be realistic to ensure natural behavior from participants.

Expect that your participants' number of responses may vary. In some situations, you might allow participants to report activities beyond the minimum and earn more for doing so. However, if you do so, you should also designate a maximum number of responses that participants can submit, to avoid having respondents manufacture fake interactions to earn more money.

Diary-study incentives should be higher than those for a typical user-testing session due to the long-term engagement required. Consider the length of the study and the effort required for participants to provide all the information you need, utilizing the tools you select.

As a broad guideline, we recommend about $40 per hour of the total time commitment you expect for a study with a general sample of US-based participants. However, this number should be adjusted accordingly for highly specialized audiences.

For studies longer than a week, think about how you might keep users engaged throughout the length of the study . You can break apart the total incentive and offer smaller installments as participants reach specific milestones (e.g., 3 days of logging), to keep them motivated throughout the duration of the study.

Think about the type of information you need from your participants.

- Is the information simple or complex?

- Do you need basic feedback about behaviors and interactions, or do you need screenshots, images, videos, or screencasts as well?

- Do you have specific questions that each participant should answer about each interaction they report?

These factors will influence the tools you choose.

- For simple text responses , you might choose to use a messaging application like Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, or Telegram.

- For more complex data , consider tools like Google Forms, Google Docs, Survey Monkey, dScout, or Recollective.

Beyond the type of data you need, there are other considerations to factor into your the choice of a tool.

Data Security

If your responses are likely to include personal identifying information or private data, select tools that guarantee data security.

Participant Convenience

Think about the tools that are most convenient for your participant sample. For example, teenagers may prefer to report activities through Snapchat rather than email.

Some tools are free,others can be quite expensive. Free tools are usually general-purpose and not tailored to diary studies, so they often involve a lot of work to onboard participants, write specific directions, communicate with participants, and process the data after the study.

Specialized diary-study tools like dScout are costly, but they alleviate a lot of the researchers’ overhead. They streamline the setup and facilitation of these studies and make them easy to run.

6. Communication Templates and Supporting Materials

You should plan to monitor your participants’ responses as they submit them . If you review data as it comes in, you can ask follow-up questions and prompt them for additional details while the activity is still fresh in their minds.

Let participants know up front that you will be reaching out throughout the study and agree on a means of contacting them so you can give encouragement or ask for clarification without being overly intrusive. Give periodic reminders each day or every few days. You’ll also want to track the qualifying submissions in relation to the reporting timeline.

Regardless of the tool you select, some preparation will be required.

It’s a good idea to create templates for various messages you will send to participants, as well as documentation and instructions in advance.

Documentation you should prepare includes:

- Study description

- Consent form

- Welcome message

- Informational packet: Directions for participation, requirements, incentive details, example logs, detailed instructions for using selected tools, schedule

- Any proactive logging prompts (Consider using a scheduling tool for automated delivery.)

- Status and check-in message templates to streamline periodic communications about the number of interactions provided and what is still required

- Post-study interview guide

- Thank you message and incentive delivery

Present the study and expectations in simple and straightforward terms, using consistent terminology throughout. Be as specific as possible about what information you need participants to log without stifling natural variability and differences that you cannot plan for.

Give users example log entries to help them understand the level of detail you need from them. But make sure you don’t bias participants toward those types of entries that you happened to provide as examples.

Communicating periodically with your participants ensures that they stay on track and that they provide you with the right data. Create template messages for the following types of participants:

- Engaged and submitting useful responses: recognize their efforts and ask them to keep up the good work.

- Less engaged or producing incomplete data: give encouragement or offer to answer any questions that may help to get them on track.

- Disengaged or submitting responses that do not fit the reporting requirements: reiterate what they need to do or possibly release these participants from the study if participation issues aren’t corrected.

Diary studies are quite complex, so writing and reviewing all supporting materials in advance will eliminate the risk of confusion and set participants up for success.

7. Run a Pilot Study

Diary studies are fairly expensive and resource-intensive, so it’s helpful to conduct a short pilot study first. Ask pilot participants for feedback about materials and the diary study experience and adjust accordingly.

The pilot study does not need to be as long as the real study and is not meant to garner data for analysis. Its purpose is to test your study design, tools, and related materials, and practice the process. It will allow you to tweak your instructions and approach to ensure you get the data you need.

8. Pre-Study Brief

In a diary study, a pre-study brief is a short meeting you conduct with participants in advance of the reporting period to get them ready for the study. You should communicate what they should report, the required number of reports, and incentives, and answer any questions they may have.

For very simple studies, a pre-study brief may not be necessary — your onboarding materials may be able to serve this purpose.

However, if your study has a complex setup or if it requires users to report complex information or to use unfamiliar tools, take the time upfront to get participants ready to log their responses.

Schedule a meeting with each participant to discuss the details of the study. Walk through the schedule or calendar for the reporting period, answer questions, and discuss expectations.

Discuss the tools they will be using and be sure each participant has familiarized themselves with the technology; answer any questions they may have before beginning.

9. Post-study Interview

After the study, you will evaluate all the information provided by each participant . Plan a follow-up interview with each participant to discuss their responses in detail. This is your last opportunity to get insights from your participants before the study ends.

Ask probing questions to uncover specific details needed to complete the story and clarify as needed. For example, if you’re studying how people use meal-delivery applications, you may ask a participant to clarify a vague response. For example, “I see that you said you were unsatisfied with the experience using this app. Can you elaborate a little bit about why you were unsatisfied?”

You might also ask general reflection questions about the broader experience you are studying, such as “Overall, what did you like or dislike about using these meal-delivery applications over the last few weeks?”

Because diary studies are longitudinal, they generate a large amount of qualitative data. Re-visit your research questions before you dig into all the rich insights you’ve collected to find the answers.

Evaluate the behaviors you’ve captured throughout the study. How did they evolve and change over time? What influenced these behaviors? If the focus of your study was around a particular product or service relationship, look at the entire customer journey.

Related Courses

Remote user research.

Collect insights without leaving your desk

Omnichannel Journeys and Customer Experience

Create a usable and cohesive cross-channel experience by following guidelines to resolve common user pain points in a multi-channel landscape

Interaction

Related Topics

- Research Methods Research Methods

Learn More:

Please accept marketing cookies to view the embedded video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=euc_KvEoV_k

5 Steps for Effective Diary Studies in Customer Journey Research

Always Pilot Test User Research Studies

Kim Salazar · 3 min

Level Up Your Focus Groups

Therese Fessenden · 5 min

Inductively Analyzing Qualitative Data

Tanner Kohler · 3 min

Related Articles:

Balancing Natural Behavior with Incentives and Accuracy in Diary Studies

Mayya Azarova · 6 min

Attitudinal vs. Behavioral Research in UX

Page Laubheimer · 5 min

Open-Ended vs. Closed Questions in User Research

Maria Rosala · 5 min

Competitive Usability Evaluations

Tim Neusesser · 6 min

Context Methods: Study Guide

Kate Moran and Mayya Azarova · 4 min

The Hawthorne Effect or Observer Bias in User Research

Mayya Azarova · 10 min

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Med Res Methodol

A qualitative approach to guide choices for designing a diary study

Karin a. m. janssens.

1 Interdisciplinary Center for Psychopathology and Emotion regulation, Department of psychiatry, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands

2 Sleep-Wake Center, Stichting Epilepsie Instellingen Nederland (SEIN), Zwolle, The Netherlands

Elisabeth H. Bos

3 Developmental Psychology, University of Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands

Judith G. M. Rosmalen

Marieke c. wichers, harriëtte riese, associated data.

Since this is a qualitative study, most of the data cannot be provided due to the protection of the privacy of the participants. Parts of the information obtained can be found in the manuscript. Data request for the quantitative part of the study can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Electronic diaries are increasingly used in diverse disciplines to collect momentary data on experienced feelings, cognitions, behavior and social context in real life situations. Choices to be made for an effective and feasible design are however a challenge. Careful and detailed documentation of argumentation of choosing a particular design, as well as general guidelines on how to design such studies are largely lacking in scientific papers. This qualitative study provides a systematic overview of arguments for choosing a specific diary study design (e.g. time frame) in order to optimize future design decisions.

During the first data assessment round, 47 researchers experienced in diary research from twelve different countries participated. They gave a description of and arguments for choosing their diary design (i.e., study duration, measurement frequency, random or fixed assessment, momentary or retrospective assessment, allowed delay to respond to the beep). During the second round, 38 participants (81%) rated the importance of the different themes identified during the first assessment round for the different diary design topics.

The rationales for diary design choices reported during the first round were mostly strongly related to the research question. The rationales were categorized into four overarching themes: nature of the variables, reliability, feasibility, and statistics. During the second round, all overarching themes were considered important for all diary design topics.

Conclusions

We conclude that no golden standard for the optimal design of a diary study exists since the design depends heavily upon the research question of the study. The findings of the current study are helpful to explicate and guide the specific choices that have to be made when designing a diary study.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12874-018-0579-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Diary studies in which participants are asked to repeatedly fill out questions about experienced feelings, cognitions, behaviors and their social context are increasingly being performed [ 1 ]. This is probably due to technological developments that ease performance of diary studies, such as the wide availability of Smartphones. Further, awareness is growing that the use of repeated assessment of (psychological) symptoms makes it possible to acquire valuable insights about (psychological) dynamics that cannot be obtained with the use of single-administered questionnaires [ 2 ]. The terms commonly used in diary research are experience sampling methods (ESM) and ecological momentary assessment (EMA). The terms ESM and EMA each stand for a wide variety of ambulatory assessment methods ranging from paper diaries and repeated telephone interviews to electronic data recording technologies and physiological recordings with sensors [ 3 ]. ESM/EMA aims to measure symptoms, affect and behavior in close relation to experience and context [ 3 , 4 ].

When designing a diary study, several choices have to be made. First, the research question should be specified, since the research question has important consequences for the choices of a diary design. Second, a decision on the sampling design should be made, e.g. the duration of the diary study and the measurement frequency. Third, one has to decide on the number of items to include in the diary. Fourth, a decision has to be made on whether participants have to answer the questionnaires on predefined (i.e. fixed assessment) or at random time-points. Fifth, it should be decided whether the items are about the here-and-now (i.e. momentary assessment) or about a previous time period (i.e. retrospective assessment). Finally, one has to decide on the delay participants are allowed to respond to the prompt to fill out the questionnaire. This is the time allowed to complete the survey before it is counted as missing data.

So far, diary design issues have mostly been addressed in methodological papers and textbooks (e.g., [ 4 – 8 ]). Although these are very useful, they are typically based on extensive personal experience from researchers who work in a specific research field. A systematic overview of information on diary design from researchers from different research fields is lacking. Typically, specific details on argumentation of choosing a particular diary design are not described in scientific publications. In order to increase information on diary designs performed in different disciplines, Stone and Shiffman already plead for careful description of argumentations for choosing a particular diary design in scientific papers [ 8 ]. Nevertheless, recent research indicates that the rationale for these choices is often not reported [ 9 ]. To overcome this omission in the literature, the aim of the current study was to obtain insight into reasons behind diary design by performance of a qualitative study. As a first step, we wanted to identify key elements relevant to diary design shared by research fields. Therefore, experts on diary studies from different research fields were asked about the rationale behind their choices for particular diary design topics.

Study population

All members of the international Society of Ambulatory Assessment [ 10 ] were invited by e-mail to participate in the study. Additionally, we invited researchers experienced in diary research from our personal network. Finally, PubMed was searched using the search terms “diary studies” and “time-series analysis”, after which leading authors of relevant articles were approached. Since the optimal design for a diary study depends heavily upon the research question, we did not strive to reach consensus, as opposed to a typical Delphi study. However, we believed that a second assessment round was necessary to validate the themes that we identified during the first assessment round. Therefore, our study is a semi-Delphi study [ 11 ] in which answers reported by the researchers during a first assessment round were independently summarized and anonymously given back to all participating researchers for feedback during a second assessment round. The first and second assessment round consisted of online questionnaires. All data processing and feedback reports were done without disclosing the identity of the participating researchers.

The first assessment round ran between October 2015 and February 2016, the second assessment round ran between April 2016 and July 2016. During both assessment rounds participants were provided a link to a Google Docs questionnaire by e-mail. Participants could answer all questions online. During the first assessment round, only open text fields were used. During the second assessment round, questions were answered on either 10 point rating scales or entered in open text fields. The data processing of both assessment rounds is explained in more detail below.

First assessment round

In the first round of this study, participants were asked to answer questions about themselves and the amount of experience they had with performing diary studies. Next, they were specifically asked about a diary study they had designed or co-designed. They were requested to report on the type of participants, study duration, the measurement frequency, the use of random or fixed assessments, the choice for momentary or retrospective assessment, and the delay participants were allowed to respond. In the current research, retrospective assessment means that questions covered the period between two prompts. In contrast to regular research in which retrospective recall is often much longer, this period was up to 24 h in the diary studies reported about in our research. We distinguished retrospective assessment from momentary assessment. During momentary assessment, questions covered the few minutes before the participants were filling out the questionnaires. Participating researchers were asked to provide these characteristics of their diary design and thereafter for their rationale behind these choices. Finally, we asked whether they would use the same diary design when he/ she should redo the study.

Data processing of the first round

KJ performed the initial thematic analysis to group the reasons given for particular diary designs into different categories for each diary design topic. A second rater (HR) grouped all arguments into these categories, and added or skipped categories if needed. In case no consensus was reached about the grouping of the arguments, a third rater (EB) made the final decision. The categorized rationales were grouped in overarching themes during a consensus meeting in which all authors (i.e., KJ, EB, JR, MW and HR) participated. During this meeting additional questions on the overarching themes raise, namely questions about the number of items used in the diary, practical suggestions and observed hiatus in the literature. These questions were added to the second assessment round.

Second assessment round

The overarching themes containing the categorized rationales for diary designs were given back to the participants during the second assessment round, in the form of a textual description accompanied by bar graphs depicting the frequency of the reported rationales. These, slightly adapted, bar graphs can be found in the result section of this article. Researchers were asked to rate the importance of the identified themes for diary studies in general for all the diary design topics (i.e. study duration, sampling frequency, random or fixed design, momentary or retrospective assessment, and delay allowed to respond to the beep). This was done on a rating scale ranging from 1 (not important at all) to 10 (extremely important).

Data processing of the second round

For each diary design topic, the median importance rate and interquartile range (IQR) were computed for each theme. The open text fields were thematically analyzed in the same way as during the first assessment round, except that EB was the second rater, and HR the third rater for the questions about practical suggestions and reported hiatus in the literature.

Participants

Forty-seven researchers participated in our study and provided us with information of 47 different diary studies. Two researchers reported about the same diary study during the first round, and one researcher reported about two studies during the second round. Answers about characteristics of the same study given by multiple participating researchers were only counted once. The researchers worked at 27 different institutes from 12 different countries. Details about the participating researchers are given in Table 1 . Information about the studies they reported on are given in Table 2 .

Characteristics of participating researchers ( n = 47)

Note: IQR Interquartile range

Characteristics of studies reported about ( n = 47)

a Assessed during the second round, based upon answers on 35 studies reported by 38 participating researchers

Study intensity

The median study duration of the studies reported on was 17 days (IQR 7, 30), the median sampling frequency was five times a day (IQR 3, 10) and the median number of items was 30 (IQR 19, 55). The longest study duration was 9 months with a sampling frequency of five times a day when the participant filled out 55 items. It should be noted that this latter study was a single-case study ( n = 1) performed in a clinical setting. The highest sampling frequency was every 15 min for 1 day while the participants filled out seven items each time. The highest number of items participants had to fill out during a single assessment was 90 in a study with a sampling frequency of twice a day for a period of 30 days.

Rationales for choices on different diary design topics

Rationales provided for the design choices will be discussed for each diary design topic, accompanied by bar graphs: i.e. the study duration (Fig. 1 ), measurement frequency (Fig. 2 ), random or fixed assessment (Fig. 3 ), momentary or retrospective assessment (Fig. 4 ), and allowed delay to respond to the beep (Fig. 5 ). Please note that some researchers did not provide a rationale for certain topics and that most researchers gave more than one rationale per topic. Therefore, the number of reasons does not add up to 47. A reason for a decision that was given for all design topics, was that the decision was based on previous research or expert opinion. Thirteen researchers did so for the decision on their study duration. They provided the following literature references: [ 12 – 17 ]. Thirtheen researchrs based their decision for the measurement frequency on previous research or expert opinion. The following references were given: [ 2 , 3 , 5 , 12 , 13 , 16 , 18 , 19 ]. One researcher based the decision for momentary or retrospective assessment on previous literature. The following literature references were provided: [ 4 , 20 – 25 ]. Four researchers based the decision for random or fixed assessment on expert opinion or previous literature. They provided the following literature references: [ 2 , 24 – 27 ]. Finally, seven researchers based their decision for the allowed delay to respond to the beep on expert opinion or previous research. These literature references were provided: [ 12 , 14 , 17 ].

Overview of the reasons provided for the chosen study duration, grouped into themes: Ot = Other, St = Statistical reasons, Fe = Feasibility, Re = Reliability, Na = Nature of the variables

Overview of reasons reported for the chosen measurement frequency, grouped into themes: Ot = Other, St = Statistical reasons, Fe = Feasibility, Re = Reliability, Na = Nature of the variables

Overview of reasons provided for the choice of (semi)random and or fixed assessment, grouped into themes: Ot = Other, St = Statistical reasons, Fe = Feasibility, Re = Reliability, Na = Nature of the variables. F = fixed and (S)R = (semi-)random

Overview of reasons provided for the choice of momentary or retrospective assessment, grouped into themes: Ot = Other, St = Statistical reasons, Fe = Feasibility, Re = Reliability, Na = Nature of the variables. M = Momentary, R = Retrospective and C = Combination of retrospective and momentary assessment

Overview of reasons provided for the chosen allowed delay to respond to the beep, grouped into themes: Ot = Other, St = Statistical reasons, Fe = Feasibility, Re = Reliability, Na = Nature of the variables

Study duration

The median study duration was 17 days, with an IQR from 7 days till 30 days, and total range between 1 and 270 days. The most frequently reported reason for the choice of a study duration was to measure long enough to obtain reliable and representative data (23 times). Also statistical reasons, such as obtaining enough observations to perform specific statistical analyses, were often reported (15 times). Reducing participant burden was reported eight times for minimizing study duration. Six researchers wanted to make sure that their study duration captured both week and weekend days, or an entire menstrual cycle. For six researchers, the study duration was related to an event, such as 2 weeks before and 4 weeks after a studied intervention. Four researchers reported that their study had to include a longer period, since the variable of interest was a priori known to occur infrequently. Very practical reasons were reported as well, e.g. the limited battery life of the ambulatory sensor. The variety of reasons a researcher can have for a particular study duration is illustrated in the following response: “We have chosen a measurement period of two weeks for several reasons. First, we wanted to have enough measurements to conduct reliable analyses within persons (….) we wanted at least 60 completed observations per person. We first decided that 5 measurements per day would be appropriate, and based on this, the minimum measurement period consists of 12 days. Eventually, we thought that 2 weekends in the measurement period would enable us to check weekend effects in a more reliable way, and we therefore set the measurement period at 14 days. In addition, our choice was also based on what we expected to be the maximum length that participants would be willing and able to fill out 5 measurements per day (….), and which length would be ‘representative’ for a person (….).”

Measurement frequency

The median measurement frequency was 5 times a day with an IQR range between 3 and 10 times a day, and total range between 1 and 50 times a day. Most researchers based their choice for a particular measurement frequency on the dynamics of the variable of interests (reported 18 times). Researchers interested in variables known to follow a circadian rhythm, like for example hormones or mood states, chose for relatively frequent measurements (e.g. 10 times a day). Researchers interested in variables expected to occur infrequently (e.g. panic attacks) or in summary measures (e.g. number of cups of coffee) chose infrequent measurements (i.e. once a day). Keeping acceptable participant burden was the second most often reported reason for a certain measurement frequency (reported 16 times). By keeping participant burden low, researchers wanted to diminish interference with participants’ normal daily lives (reported five times), improve compliance (reported four times), improve response rate (reported twice), and keep drop out low (reported twice). Nine researchers based their measurement frequency on the assessment on different parts of the day. Eight reported feasibility, not further specified, for their choice of the measurement frequency.

Five researchers chose for frequent measurements in order to increase representativeness of the data, and four to diminish recall bias and in this way increase reliability. Four researchers mentioned that frequent measurements were necessary to perform meaningful statistical analyses, and three that equidistant measurements were needed to meet the statistical assumptions, e.g. for vector autoregressive analyses. The ultimate choice for a particular study duration was mostly a compromise between these different aspects. This was nicely illustrated by one of the participating researchers: “Because the study aimed to investigate a rapidly varying phenomenon, namely momentary affective state and reactivity, we wanted to optimize temporal resolution. We wanted as high measurement frequency ( i.e. temporal resolution) as possible without compromising compliance. A frequency of 10 times per day has been shown to be feasible in previous studies (Csikszentmihalyi et al . 1987. J Nerv Ment Dis; 175:526–536, Shiffman et al 2008. Annu Rev Clin Psychol; 4: 1–32).”

Random or fixed assessment

Although we asked whether researchers used fixed or random assessment, many researchers indicated that they used semi-random assessment instead. Semi-random assessment means that an assessment occurs at a random time point, however within a certain predefined time window, to ascertain that assessments are on average equally spread over a day. Twenty-four researchers used a fixed assessment, eleven used random assessment, ten a semi-random assessment, and one used a combination of fixed and random assessment design. Since we expect that random designs were in fact mostly semi-random in nature, arguments for using them will be discussed together.

(Semi-)Random assessment was mostly chosen to avoid reactivity and anticipation effects (reported 14 times) and to increase the representativeness of the data (reported seven times). For example, one researcher wrote: “ Random intervals presumably decrease the influence of the measurements on daily life activities of the participants, as the participants do not know the exact measurement time and cannot plan and change their activities based on that. This increases ecological validity. Semi-random intervals guarantee that measurement times are evenly distributed across the day (Shiffman et al 2008. Annu Rev Clin Psychol; 4: 1-32).” The main reason for a fixed design was that such a design made it possible to obtain time-series data with equidistant time points required for many statistical techniques, such as vector autoregressive analyses (14 times). Other reasons for choosing for fixed designs were related to feasibility, e.g. to decrease participant burden (seven times), increase protocol adherence (seven times), and increase response rate (four times).

Retrospective or momentary assessment

Most researchers ( n = 21) used a combined momentary and retrospective assessment design, followed by 14 researchers that chose for only momentary assessments, and finally 12 researchers that chose for only retrospective assessment. A retrospective assessment design was often used in order to obtain a (reflective) summary measure (reported 12 times) and for assessing thoughts or events, since these are mostly count variables (reported six times). Momentary assessment was mostly used to assess current emotions or context (reported ten times) and to capture life as it is lived (reported four times). For example, one researcher wrote: “Emotions were measured momentary as these are fleeting experiences and heavily influenced by recall bias. Daily events were asked retrospective (windows of approximately 90 minutes) as this is needed to capture the most important events that happened and that may have been rewarding or stressful” . The most frequently reported reason to assess momentary was to diminish recall bias (reported 14 times). Reasons related to feasibility were reported for both assessment methods, e.g. retrospective assessment was considered to be less intrusive, and momentary assessment easier to respond to. With regard to statistics, two researchers used a combination of momentary and retrospective assessment to allow studying the temporal order of events: “In addition, we chose for this design (affect/cognition momentarily and events retrospectively) because when assessing the relationships between events and affect/cognition the ordering would always be clear: events happened before the affect/cognition measurements. If both would have been asked retrospectively, it would have been less clear whether the affective states/cognitions came first or the events.”

Allowed delay to respond to the beep

The median amount of delay allowed to respond when respondents were prompted to fill out a questionnaire was 30 min, with an IQR of 15 min to 60 min, and total range between 1.5 min and 24 h. The most commonly reported reason for the delay allowed to respond was to give the respondents enough time to respond (reported 14 times). Thirteen researchers only allowed short delays in order to increase the ecological validity of the data (e.g., better representations of the activities the participant is currently involved in) and ten did so to diminish recall bias. Five researchers wanted to obtain momentary feelings and therefore did not allow participants much time to respond (that is < 20 min). Six researchers only allowed short delays to retain the measurement frequency needed to perform their analyses. The delay allowed to respond was also related to the measurement frequency. A researcher that opted for a long delay wrote: “Because for time-series analysis it is important to have little missing values, we chose a relatively long delay. Because we only have three measurements a day and because many of our variables concern “the previous measurement interval”, we don’t see this as a big problem.” A researcher who chose a short delay wrote : “We chose to allow a relatively short length of delay to ensure the real-time assessment and to avoid recall bias. However, to increase compliance, some delay has to be allowed as the participants are living their normal lives and are not always able to reply immediately. 15 minutes delay has been used in previous studies (e.g. Jacobs et al 2011. Br J Clin Psychol; 50: 19-32). Results from previous paper&pencil –diary studies suggest that most of the participants answer within 10 to 20 minutes (Csikszentmihalyi et al 1987. J Nerv Ment Dis; 175:526-536) and that answers after a longer than 15 minutes delay are less reliable (Wichers et al 2007. Acta Psychiatr Scand; 115: 451-457).”

Using the study design again

Most researchers (i.e. n = 27 [60%]) reported that on hindsight they were satisfied with their designs. Of the researchers who were not satisfied, most would like to intensify their diary design, by using more frequent measurements (five researchers), extending the diary period (four researchers), using a combination of intensive diary and longitudinal designs (i.e. burst designs, two researchers), or adding some items (one researcher). Three researchers opted for a less intensive design: that is a lower measurement frequency ( n = 2) or fewer items in the diary ( n = 1). Further, two researchers would have included more participants and one would have personalized the diary items.

Themes identified

After thematically analyzing the data of the first assessment round, four overarching themes were identified that covered the reasons mentioned for choices behind all diary design topics. The first theme was ‘the nature of the variables of interest’. This theme comprised reasons related to characteristics of the variable of interest, for example its fluctuation pattern or its occurrence rate. The second theme was ‘reliability’. Reliability referred to the reproducibility, representativeness, and/or consistency of the obtained assessments. The third theme was ‘feasibility’. This theme covered reasons related to practicability for both the participant and the researcher. The fourth theme was ‘statistics’. This theme contained reasons related to performance of statistical analyses. To get more insight into these categories, the reasons reported by the researchers are grouped per category in Figs. Figs.1, 1 , ,2, 2 , ,3, 3 , ,4, 4 , ,5 5 .

Thirty-eight participants (81% of the participants in the first assessment round) participated in the second assessment round. They rated the importance of the different overarching themes identified during the first assessment round for the choices of each diary design topic.

Importance of different themes

The importance rates (scored on a scale from 0 = not important at all to 10 = extremely important) for the different overarching themes for each diary design topics are given in Table 3 . The role of statistics for the choice of the time allowed to respond was considered least import (i.e. median 6, IQR: 4–8). The role of the nature of the variable of interest for the choice of momentary or retrospective was considered most important (i.e. median 9. IQR: 9–10). The nature of the variable(s) of interest (e.g., its occurrence or fluctuation rate) was found to be most important for making a decision about the measurement frequency and the choice for momentary or retrospective assessment. The nature of the variable(s) of interest and the reliability (e.g. obtaining representative data) were found to be most important for the choice of the study duration. The reliability and statistics (e.g. obtaining equidistant data) were most important for the choice of (semi)random or fixed assessment. The nature of the variable, reliability and feasibility were all found equally important for the choice of the delay allowed to respond.

Importance rates of overarching themes for different diary design topics

Note: Assessed on a scale ranging from 1 (not important) to 10 (extremely important), more details are given in the method section

Medians (Interquartile range) are given

Practical suggestions

We will now discuss the practical suggestions to improve diary studies that were reported by more than one researcher. Suggestions that were reported by only one researcher are given in Additional file 1 . Suggestions were provided by 34 researchers, four researchers did not report suggestions.

To increase the reliability of the obtained data, the following suggestions were given. Five researchers suggested to use language for the items and answering scales that suits participants (e.g. to use easy wording and ask about the here-and-now). Four researchers suggested to use previous studies or pilots to help designing a diary study. Two researchers suggested making the study relevant for participants as well, for example by providing them personalized feedback reports based on their diary data. Two researchers reported to use reliable items or modified traditional questionnaires. Two researchers suggested verifying the sampling times of the self-reported data with objective information obtained at the same moment (i.e. general available weather information) and telling participants that you will do so.

To increase the feasibility for participants, it was suggested to use short questionnaires (six times), sample not too frequently (five times), use electronic diaries or smartphones (four times), use fixed sampling designs (four times), provide incentives (four times), personalize the (fixed) sampling scheme to the participants’ preference (four times), and to allow a long delay to respond (twice).

Many suggestions were about involving participants when preparing, conducting, and evaluating the study. It was suggested to offer participants close support during the diary study (eight times), to think together with participants about how to prevent missing data (four times), give good briefing and instructions to your participants (four times), and to perform a pilot study to check on feasibility (twice). Other suggestions were to use fixed or equidistant assessment designs (four times) and to ensure enough assessments (four times) to increase statistical possibilities.

Suggestions for future research

The nine suggestions for future research reported by more than one researcher were: theoretical guidance with regard to dynamics of phenomena of interest (ten times); theoretical guidance on what the advantages and disadvantages are of particular diary designs (eight times); information on how burdensome particular designs are (for particular target populations) (five times); information about power calculation (both number of participants and number of time-points) (four times); information on statistical strategies for diary data (thrice); information on optimal number of items (twice), information on how to obtain reliable data (twice): and information on whether the reliability of the data changes over time (twice). Gaps in the literature that were reported by only one researcher can be found in Additional file 2 . Finally, five researchers indicated that they did not know the answer or did not respond, and three researchers reported that we know already a lot (although one of them also reported that an extensive/complete overview of all pros and cons of certain designs is lacking).

From the results of this semi-Delphi study we can conclude that the nature of the variable(s) of interest, reliability, feasibility and statistics were important to keep in mind when making decisions on diary design topics. Small differences in importance scores were found. The nature of the variable(s) of interest (e.g., its occurrence or fluctuation rate) was found to be most important for making a decision about the measurement frequency and the choice for momentary or retrospective assessments. The nature of the variable(s) of interest, and the reliability (e.g. obtaining representative data) were found to be most important for the choice of the study duration. The reliability and statistics (e.g. obtaining equidistant data) were most important for the choice of (semi)random or fixed assessment. The nature of the variable, reliability and feasibility were all found equally important for the choice of the delay allowed to respond.

The strong points of this study are that the qualitative approach allowed insight into the reasoning of researchers when deciding on a particular study design. Moreover, researchers from eleven different countries from 27 institutes participated and reported about a wide variety of studies which increased the generalizability of our study. The open text field answers were independently scored by two reviewers, in order to diminish subjective choices while grouping the reported reasons.

A limitation of this study is that although we planned to perform a Delphi study, the diversity and the number of topics addressed did not allow in depth discussion of different viewpoints of participating researchers. For example, most researchers argued that increasing the measurement frequency would increase participant burden, while some reported that increasing the measurement frequency actually decreases participant burden, since it becomes more routine for participants to fill out the questionnaire. It would have been interesting to have the participating researchers discussing these different points of view, for example in focus groups. Moreover, the online survey might potentially have led to less extensive responses than could have been obtained by face-to-face interviews. Further, although we strived to include researchers from a variety of research fields by inviting researchers who were member of the Society of Ambulatory Assessment, we only partially managed to do so. By also contacting researchers from our personal network, an oversampling might have occurred of researchers using fixed and low frequency sampling schemes and of researchers performing studies on mood disorders. Also some participating researchers were relatively new in the field, and completed only one or two diary studies so far. This might have diminished the generalizability of our findings.

Findings in the current study are generally in line with recommendations in text books and other methodological articles in which diary design topics are addressed [ 1 , 4 – 6 , 28 ], and no unexpected findings came out. The emphasis on particular diary designs in prior publications was however somewhat different from the current study, as they were mostly in favour of (semi)random designs and momentary assessment. The current study found also many arguments in favour of using fixed designs and retrospective assessment. This is probably due to the larger weight that was given to statistical possibilities for data collected at equidistant time points and the nature of the variable of interest for choices of diary designs. In the current study, also topics that so far gained relatively little attention were addressed such as the number of items to include in a diary study and the time participants were allowed to respond to the prompt. Further, the current study is the first to identify and categorize reasons for diary design choices made by researchers from different research fields in specific diary studies. Therefore, it offers examples of translations of methodological knowledge to specific research settings. Upcoming researchers in the field might thereby obtain further insight into the various options and to consider these options carefully when planning a study. Researchers are made aware that these choices may have a large influence on the collected data and on the research questions that can be answered. We therefore believe that our study might serve as a helpful source of information for researchers designing diary-based research. It presents an overview of the different choices they can make, with arguments in favour of specific choices in specific circumstances. It also shows that design choices often are a trade-off between different themes, because taking the nature of the variables, reliability, feasibility, and statistical possibilities into account when choosing a specific design topic may lead to conflicting optimal designs. For example, a long study duration may improve reliability, but decrease feasibility. Most importantly, we hope to increase the awareness that a gold standard for the optimal design of a diary study is not possible, since the design depends heavily on the research question.

To make the results more applicable for future researchers, we developed a checklist for designing a diary study based on our results. This checklist is intended to make researchers think carefully about their research design before conducting a diary study, and contains practical considerations, such as sending out reminder text messages. The checklist is given in Additional file 3 and is successfully used at our department. Results of our study can also be used to adapt the recently published checklist for reporting EMA studies that was based on the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist [ 9 ]. For example, information on reasons behind design selection decisions, information on whether items were assessed momentary or retrospectively, and information on the delay the respondents were allowed to respond might be useful additions to this checklist, since this information might help other researchers when designing their own study. Further, information on whether items were assessed momentarily or retrospectively is essential for interpreting the results. Information on the dynamics of the variables of interests and the participant burden of different sampling schemes is also essential for making sophisticated decisions. These topics have up-till-now only been scarcely examined (e.g., [ 2 , 27 , 29 ]). We believe that a careful description of diary designs in the method section of future studies or on study pre-registration platforms might increase insight into these topics.

The current study identified different topics that are helpful to keep in mind when designing a diary study, namely the nature of the variables, reliability, feasibility and statistics. All these topics were found to be important for choices on the study duration, the measurement frequency, random or fixed assessment, momentary or retrospective assessment, and time allowed to respond to the beep. No preferred designs have been provided, since the exact choices for the study design depend heavily upon the research questions. We believe this study will help guiding the choices that have to be made for optimal diary designs.

Additional files

Additional practical suggestions as reported by participating researchers. (DOCX 16 kb)

Additional gaps in the literature as reported by participating researchers. (DOCX 15 kb)

Example of a checklist for handing in a diary study used within our (i.e. the authors) psychiatry department at the University Medical Center Groningen, the Netherlands. (DOCX 18 kb)

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Society for Ambulatory Assessment for providing their mailing list, and we would like to thank all participating researchers for their valuable input to this study. We would also like to thank Inge ten Vaarwerk and Erwin Veermans for their critical feedback on the Checklist for diary studies within RoQua [ 30 ].

The authors received no specific funding for this work. We acknowledge the financial contribution of the iLab of the department of Psychiatry of the UMCG [ 31 ] to the appointment of dr. K.A.M. Janssens.

Availability of data and materials

Abbreviations, authors’ contributions.

KAMJ designed the study, wrote the initial and final draft of the study and performed the qualitative and quantitative analyses. EHB designed the study, contributed to the qualitative analyses, and reviewed and approved the final manuscript. JGMR designed the study, and reviewed and approved the final manuscript. MCW designed the study, and reviewed and approved the final manuscript. HR designed the study, contributed to the qualitative analyses, and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Our study does not fall under the scope of the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO) and thus no approval of the ethics committee and no informed consent had to be obtained according to our national regulation, see also guidelines of the Central Committee on research involving human subjects ( www.ccmo.nl ).

Consent for publication

Our study does not fall under the scope of the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO) and thus no informed consent had to be obtained according to our national regulation, see also guidelines of the Central Committee on research involving human subjects ( www.ccmo.nl ). However, participants (all scientific researchers) were informed on forehand that their information would anonymously be used for scientific publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Karin A. M. Janssens, Email: [email protected] .

Elisabeth H. Bos, Email: [email protected] .

Judith G. M. Rosmalen, Email: [email protected] .

Marieke C. Wichers, Email: [email protected] .

Harriëtte Riese, Email: [email protected] .

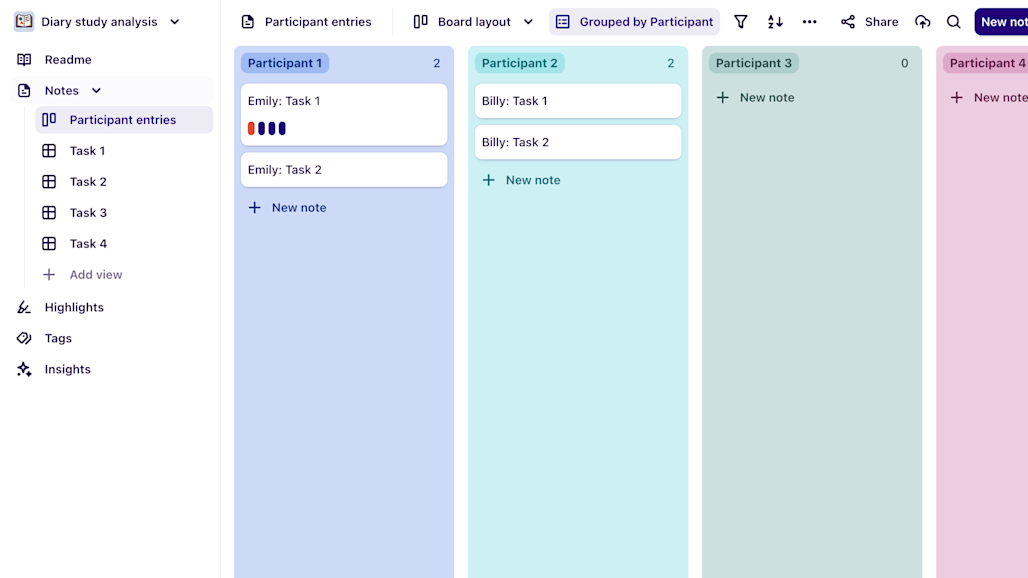

Integrations

What's new?

Prototype Testing

Live Website Testing

Feedback Surveys

Interview Studies

Card Sorting

Tree Testing

In-Product Prompts

Participant Management

Automated Reports

Templates Gallery

Choose from our library of pre-built mazes to copy, customize, and share with your own users

Browse all templates

Financial Services

Tech & Software

Product Designers

Product Managers

User Researchers

By use case

Concept & Idea Validation

Wireframe & Usability Test

Content & Copy Testing

Feedback & Satisfaction

Content Hub

Educational resources for product, research and design teams

Explore all resources

Question Bank

Research Maturity Model

Guides & Reports

Help Center

Future of User Research Report

The Optimal Path Podcast

Maze Guides | Resources Hub

What is UX Research: The Ultimate Guide for UX Researchers

0% complete

Diary research: Understanding UX in context

Diary research is a research method which provides a deep level of intimate insight into your target user and focus area. Read on to learn how to plan, prepare, and conduct diary studies.

What is diary research?

Diary research—also known as a diary study—is a longitudinal (running over a period of time) UX research method used to collect qualitative data , through participants keeping a diary to record their thoughts, feelings, and behavior, while they use a product.

A diary study entails participants self-reporting data over an extended period of time—ranging from days to a month or longer. During this time, they’ll log specific information about activities regarding the product being studied.

Diary studies allow us to better understand the complexity of the user experience, which changes so drastically based on the use cases experienced by users, and the evolution of the product in their hands.

Matthieu Dixte , Product Researcher @ Maze

The purpose of diary studies

The main value of diary studies are their unique ability to give contextual insights about real-time user behavior and needs . Unlike other research methods—such as usability tests or user interviews, which provide observational data gathered in a lab-based situation, removed from a product’s everyday application—diary studies offer a window into the reality of users interacting with products .

Product teams can then use these organic insights to define UX features and requirements, creating a truly user-centered experience, without the guesswork.

Methods for conducting diary research

There are several methods of diary study, ranging from open diary studies which give participants freedom to use the diary as they wish, and closed diary studies which follow a tighter set of protocols. Depending on your research objectives, you’ll want to choose between the two:

- Freeform/open diary study: Similar to a personal journal, this type of study gives participants a lot of freedom in how and when they record their thoughts. You’ll still want to give subjects some initial guidance, but the diary is more free-form. This style enables less-experienced participants to take part, and people are likely to provide information you may not think to ask for, making it ideal for generative research. However, the downside is participants may not include the details you need, or include too little—or too much—information.

- Structured/closed diary study: A closed diary study uses pre-set focuses and closed-ended questions to uncover information. Structured diaries may include a page per study day, concluding questions, and explicit instructions. They are typically easier to analyze as the data will be pre-formatted across all participants. They also ensure you receive the information that’s most relevant to your study, so it’s perfect for evaluative research. The downside of this study type is that you may miss out on additional insights that don’t fit into the structure provided.

Most researchers find that the ideal method sits somewhere between freeform and structured, providing participants with a decent amount of guidance and reminders throughout the study, without overcrowding them.

The different types of diary studies

Along with deciding between an open or closed diary study, you also need to determine the type of diary you’ll be using.

There are an increasing number of ways to record diary entries, all of which broadly fall under the bracket of digital or paper. Unlike other research methods, the research tool you use for a diary study does not significantly impact the results, so the decision mostly comes down to the resources you have available (whether you can pay for an online tool or physical diaries) or personal preferences.

Paper diaries are a good, simple format for respondents, but there are big advantages to digital diary studies. You can ask follow-up questions, and have the ability to make sure respondents answer in the way you want them to. It’s also a big plus to be able to collect results little-by-little, and progress at the same pace as the analysis of results (even if sometimes it’s too early to draw conclusions.

Digital/online

- Digital tool e.g. dscout

- Online platform e.g. GoogleDocs

- Mobile app e.g. Indeemo

- Digital communication platform e.g. Whatsapp

Paper/offline

- A physical diary (provided by researcher or participant)

- Question sheet

- Video/audio log

Tip: The only main differentiator, other than cost, is that some digital research tools may analyze the results for you.

The benefits of diary research

There’s many reasons to opt for diary studies as your choice of research method , from a focus on micro-moments to providing real-life context to data. Let’s cover the perks of diary research.

Provides data with real-world context

One of the stand-out points of diary studies are how they convey a product’s impact within real-world context.

Diary research requires study participants to actually interact with a product in their everyday life, and record data in-situ (or shortly after). Where the majority of research methods ask participants questions outside a real-life scenario, diary studies do the opposite.

As a result, you’ll receive far more reliable, honest, and contextualized data. For example, say you’re making a travel maps app, during a usability test, users may find few issues with the app. However, in the real world, users may discover that the app doesn’t work offline and makes navigation difficult. They may realize that some of the features they use most when actually navigating, are ones they barely considered when sat in a research room.

Gaining this data is incredibly valuable, and provides key feedback points and priority for product teams, where previously they may have missed it.

Allows for a deep level of insight and micro-moments

Where some research methods reveal broad strokes of insight, diary studies scope in on the detail that builds the bigger picture.

If you want to focus on the micro-moments of user experience, diary research offers designers an incredibly detailed understanding of the users and product in question.

The purpose of a diary study is to understand long-term behaviors such as habits, changes in behavior or perception (especially if your product is evolving), motivations, customer journeys, etc.

One example is if you’re researching what makes users purchase a new product—asking them the question outright will likely provide a different answer than observing their thoughts and frustrations over the course of a week or longer. A longitudinal study like this will surface those micro-moments that build up, pushing someone towards a major choice.

By giving participants the opportunity to record thoughts, feelings and behaviors in the moment they happen, you also gain a deeper understanding of how your product works and impacts the user. This sort of nuance typically fades from our mind over time—where other UX research methods are a snapshot of user experience, diary research is like an HD video.

Captures how behaviors change over time

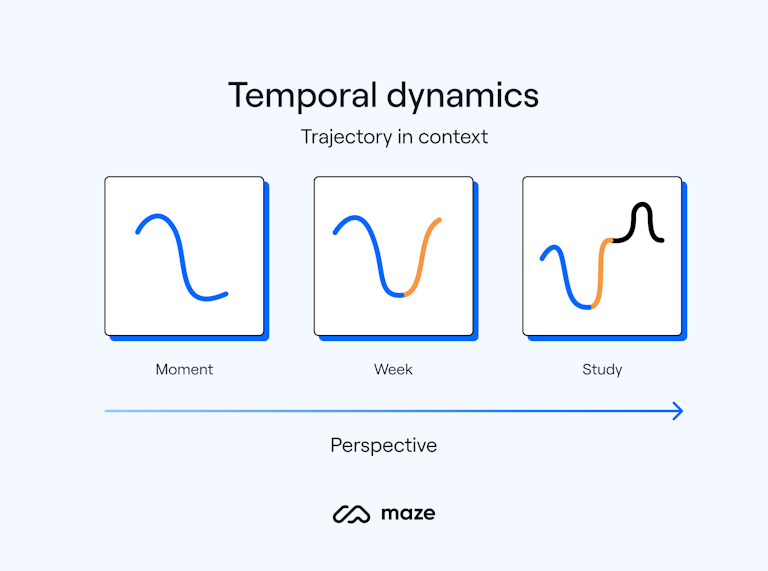

Temporal dynamics refers to how perceptions and behaviors change over time, and how they interact with and impact each other. For the sake of a product’s longevity, diary studies’ ability to reveal temporal dynamics is incredibly useful.

Diary research is one of the few research methodologies that provides respondents with autonomy, as well as a way to track their progress over time. This inherently means data is less likely to be biased in terms of the evolution of the results.

For a majority of UX research methods, users respond in the moment. Decisions are made on the spot, and thoughts are recorded during the test or afterwards. The perks of this is that you get gut reactions without users overthinking. However, it means your insight only goes so many levels deep.

Diary research, on the other hand, gives participants the opportunity to check in multiple times, record how their thoughts and feelings change over time, and reflect on their answers. It encourages self-discovery, providing you with a different lens of insight to consider.

Diary research’s longitudinal approach means you can understand how different events, emotions, and moments impact decisions and interactions with a product at the start of their relationship right through to consistent usage.

This view can unlock unique insights such as:

User habits and usage scenarios:

- What does a typical day look like for users; when do they engage with the product?

- What behaviors are spontaneous vs. pre-planned?

- What behaviors are sporadic, or habitual?

- When, why, and how does life interrupt usage of the product?

- What do users do before/after using the product?

- What are their workflows for completing these tasks?

Changes in behavior and perception:

- How learnable is a product?

- Do users share the product or results of using the product with others?

- Does using the product become part of their routine?

- What are users’ primary motivations for using the product—does this change?

- What are their main tasks with the product—does this change?

Attitudes and motivations:

- How do users feel before and after engaging with the product?

- How do they feel when they complete a task?

- Why do they make certain decisions?

- How do feelings and perceptions about the product change over time?

- What points of delight or friction are there?

Gathering answers to these questions enables you to develop a richer understanding of your users, and product, while also providing questions, scenarios, and research goals for future tests.

Minimize bias and the impact of observation

Even in the most carefully planned, unbiased research studies, participants are somewhat influenced by the presence of observation. Regardless of whether a study is moderated or not, participants know they are being observed—as a result, data will always be somewhat biased, however much we mitigate that.

Consider a field study; even though participants are in their natural habitat and you’re able to observe their day-to-day life, the participant will still act differently to how they do when truly alone.

Diary studies allow researchers to simulate a more personal relationship between user and study than other research methods. If the purpose of research is to truly uncover how participants interact with a product, then diary research captures this at its most natural.

The other plus side of a lack-of-observer is that—if prepared in advance—diary studies can self-run, removing some of the resources needed. Of course they still need to be monitored intermittently, but depending on how much you plan to communicate with participants, they can be fairly self-sufficient.

When should you conduct diary research?

There’s many circumstances where you may want to use diary research. Depending on your focus, the time you’ll want to conduct your study may vary.

Diary study objectives

The focus of a diary study can range from extremely specific (e.g. understanding all interactions with a specific section of a web page) to very broad (e.g. gathering general information about when people use a smartphone).

The Nielsen Norman Group suggests there are broadly four categories of diary study topics: 1. Product or website: Understanding all interactions with a product or site (e.g. a retail site) over the course of a month 2. Behavior: Gathering general information about user behavior (e.g. smartphone usage) 3. General activity: Understanding how people complete general activities (e.g. sharing information via social tools or shopping online) 4. A specific activity: Understanding how people complete specific activities (e.g. buying a new car)

The best time to conduct diary research

Diary studies can be conducted at any stage in the design process, but are typically most useful at the beginning, middle, and end:

When you’re in the discovery phase , diary research can reveal how users currently solve the problem in question, giving you valuable context to plan your own solution. Discovery-phase diary research can also be conducted on existing products or competitors, to set benchmarks or better understand the way users interact with similar products.

Testing early-stage prototypes can be done with diary research to gather information on the current success of your design, and identify any issues to address in future iterations.

At the end of development , a diary study can delve into user experience in the closest simulation to real life. This is a chance to see whether users are interacting with your product as expected, and uncover any missed opportunities for improvement.

After launch , diary research is helpful as a form of post-study interview to assess the success of a product and analyze performance in the real world; is it meeting expectations, what changes should be implemented in updates?

Diary research doesn’t necessarily take more time than other quantitative research methods. While there’s passive time of the study to take into account, it’s the analysis that is time-consuming. You’re analyzing evolutions of behavior and in-depth patterns, each focused on a different respondent’s perspective. The insight is well worth the time, but it helps to do this analysis in bits and pieces as you progress through the study.

Things to consider before conducting your diary study

Like most research methods, planning a diary study involves a lot of preparation. The added element of diary research being fairly hands-off, and taking place over a significant course of time, means it’s even more important to ensure you’ve not missed anything.

To help, here’s some things to consider before your study gets underway:

What type of diary are you using?

Determine what type of study you want to conduct, and the kind of diary your participants will be using.

- Open or closed: As we saw earlier in the chapter, open diaries are ideal for generative research, and closed for evaluative research. Take a look at the section above for a full rundown on the pros and cons of each, and remember to consider your research goals while deciding.

- Online or offline: Decide on the type of diary you want filled in. Consider your users—are they tech-savvy and would gel with electronic diaries? What activities are they logging—if you’re researching the durability of camping equipment, an offline diary users can travel with may work best. However, if you’re studying cosmetic preferences, then maybe a video log where participants can record their usage would make sense.

What equipment do you need?

If you’re asking participants to use a certain product, have they received a physical item, product, or prototype? Do they need instructions for it? If you’re testing a website or app, do participants have access to the platform and a copy of instructions for logging in?

What kind of logging are you doing?

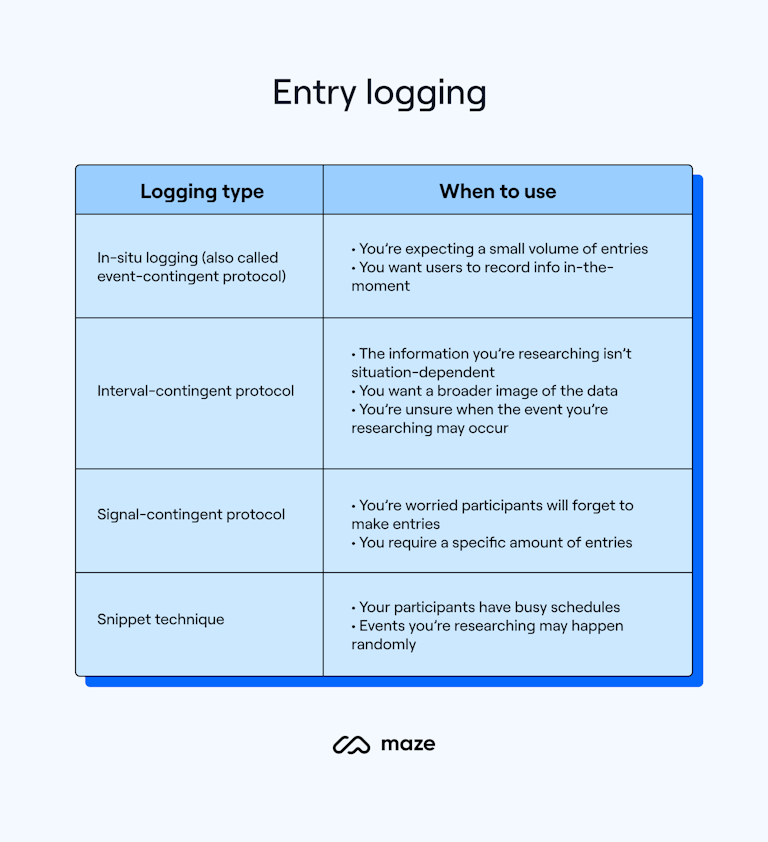

Before you can begin your study, it’s crucial to think about how you’ll ensure diary entries are logged. There are several approaches to logging:

- In-situ logging (also called event-contingent protocol): Participants log when a relevant event occurs

When to use: Since this method asks participants to log information as it happens, it’s best for research where you don’t expect high volumes of entries, as this could disrupt the participant’s usual activities, and would be difficult to analyze later. For example, if you’re researching fashion retail websites, one of the events you’d ask participants to log may be each time they think about or browse clothing websites.

- Interval-contingent protocol: Participants are given predetermined intervals to report into, e.g. asking for entries to be logged every three hours

When to use: This technique is effective if the research you’re conducting isn’t situation-dependent, if you want a broader picture of daily life, or if you’re unsure when the event may occur. E.g. If you're researching the use of infant toys, interval-contingent protocol may be useful, as it’s hard to predict the play patterns of young children.

- Signal-contingent protocol: Participants receive notification to log. These may be manually sent or set up to automatically notify participants at regular or pre-planned intervals.

When to use: This method ensures you’ll receive an adequate amount of entries (typically one per day, or more if you’re doing in-situ logging), and reduces the possibility of participants forgetting to log entries, however it requires a notification tool and participants with some flexibility (unless you tailor notifications to their schedule).