Essay on Polygamy Is Better Than Monogamy

Students are often asked to write an essay on Polygamy Is Better Than Monogamy in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Polygamy Is Better Than Monogamy

More support in family life.

Polygamy means being married to more than one person at a time. This can make family life stronger because there are more adults to help with things like money, housework, and taking care of kids. Everyone can share these jobs, so no one gets too tired or stressed.

Diverse Relationships

In polygamy, people enjoy a variety of relationships. Each partner brings different strengths and emotions to the family. This mix can create a rich and fulfilling family life, where each member learns from the others and grows.

Better Child Care

Children in polygamous families often have more than one mother or father figure. This means more love and attention for each child. It can also mean a better upbringing because there are more people to teach them right from wrong.

Economic Benefits

Polygamous families can be better off money-wise. With more adults working, they can make more money. This can mean a better life for the whole family, with more food, a bigger house, and money for school or fun activities.

250 Words Essay on Polygamy Is Better Than Monogamy

Understanding polygamy and monogamy.

Polygamy means being married to more than one person at the same time, while monogamy means being married to only one person. Some people believe polygamy has benefits over monogamy.

Sharing Responsibilities

In polygamy, chores and responsibilities can be shared among the partners. This can make life easier because one person does not have to do everything. For example, in a house with many adults, they can take turns cooking, cleaning, and taking care of children.

Financial Support

With more than one adult working, a polygamous family can have more money. More money means the family can afford better things like a nice house, good food, and education for the children.

Children Have More Care

Children in polygamous families often have more than two adults to look after them. This means they can get more love and help with their problems. If one parent is busy, another can step in to help the child.

Social Bonds

Polygamy can create strong social bonds. Since the family is big, people can help each other in tough times. They can also enjoy celebrations and holidays together, making life more joyful.

Polygamy has its advantages, like shared work, more money, and a big support system. It can make life easier and happier for some people. It is important to remember that the choice between polygamy and monogamy depends on what works best for the individuals involved.

500 Words Essay on Polygamy Is Better Than Monogamy

When people decide to spend their lives together, they often choose between two types of relationships: polygamy and monogamy. Polygamy means being married to more than one person at the same time, while monogamy means being married to only one person. Some believe that polygamy can be better than monogamy. This essay will discuss why they think so, using simple words and ideas.

Support and Help in a Polygamous Family

In a polygamous family, there are more adults to take care of the children and the house. This means the work can be shared. If one person is busy or sick, others can help with cooking, cleaning, and taking care of the kids. This teamwork can make life easier for everyone in the family. It’s like having a big team where each player has a special role, and they all work together to win the game.

Financial Benefits

More adults in a family also mean more people can earn money. In a polygamous setup, if one person loses their job, the family still has other sources of income. This can make the family stronger in tough times, like a boat with many anchors, which is safer in a storm than a boat with just one.

Children Have More Guidance

Children in a polygamous family can get love and learning from more than just two parents. They have a bigger group of adults to teach them right from wrong and help with their schoolwork. It’s like having more coaches in a sports team, which can help the players become better and stronger.

Social and Cultural Reasons

In many cultures, polygamy is a traditional way of life. It is part of their history and helps keep communities strong. People in these cultures can have large families with many relatives. This creates a sense of belonging and support that is very important to them. It’s like being part of a big club where everyone knows each other and looks out for one another.

Personal Choices and Happiness

Finally, some people just feel happier in a polygamous relationship. They like having the company and friendship of more than one partner. Everyone is different, and what makes one person happy might not work for another. It’s important for people to choose the kind of relationship that feels right for them, just like choosing the right clothes to wear.

In conclusion, while some prefer to be with just one partner, others find that being with more than one can bring many benefits. Polygamy can offer support, financial stability, more guidance for children, and can be a part of cultural practices. It can also make some people happier. It’s important to remember that the best type of relationship is the one where all people involved feel loved, respected, and happy, whether it’s polygamy or monogamy.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Politics And Society

- Essay on Political Socialization

- Essay on Political Ideology

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The Pros and Cons of Polygamy

Is there a link between polygamy and social unrest.

Posted January 4, 2018 | Reviewed by Kaja Perina

- Making Marriage Work

- Find a marriage therapist near me

- Polygyny may benefit the women involved, who may come to enjoy one another’s company and share out the burdens of housekeeping and childrearing.

- Younger wives may add to the status and standing of the first wife, while at the same time subtracting from her responsibilities.

- Polygyny sanctions and perpetuates gender inequality, with co-wives officially and patently subordinated to their husband.

[Article updated on 25 April 2020.]

In the state of nature, people were generally polygamous, as are most animals. With many animals, the male leaves the female soon after mating and long before any offspring are born.

According to genetic studies, it is only relatively recently, about 10,000 years ago, that monogamy began to prevail over polygamy in human populations. Monogamous unions may have developed in tandem with sedentary agriculture, helping to maintain land and property within the same narrow kin group.

Polygamy may enable a male to sire more offspring, but monogamy can, in certain circumstances, represent a more successful overall reproductive strategy. By sticking with the same female, a male is able to ensure that the female’s offspring are also his, and prevent this offspring from being killed by male rivals intent on returning the female to fertility (breastfeeding being a natural contraceptive).

Historically, most cultures that permitted polygamy permitted polygyny (a man taking two or more wives) rather than polyandry (a woman taking two or more husbands).

In the Gallic War , Julius Cæsar claimed that, among ancient Britons, ‘ten and even twelve men have wives in common’, particularly brothers, or fathers and sons—which to me sounds more like group marriage than polyandry proper.

Let’s talk about the rarer polyandry first. Polyandry is typically tied to scarcity of land and resources, as, for example, in certain parts of the Himalayas, and serves to limit population growth. If it involves several brothers married to the one wife (fraternal polyandry), it also protects the family’s land from division.

In Europe, this was generally achieved through the feudal rule of primogeniture (‘first born’), still practised among the British aristocracy, by which the eldest legitimate son inherits the entire estate (or almost) of both his parents. Primogeniture has antecedents in the Bible, with, most notably, Esau selling his ‘birthright’ to his younger brother Jacob.

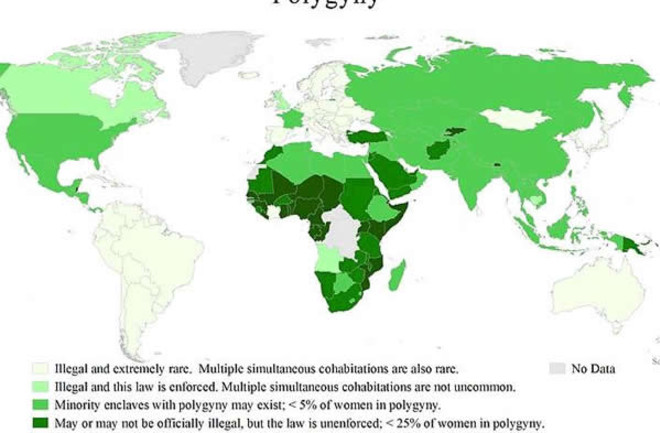

Today, most countries that permit polygamy—invariably in the form of polygyny—are countries with a Muslim majority or sizeable Muslim minority. In some countries, such as India, polygamy is legal only for Muslims. In others, such as Russia and South Africa, it is illegal but not criminalized.

Under Islamic marital jurisprudence, a man can take up to four wives, so long as he treats them all equally. While it is true that Islam permits polygyny, it does not require or impose it: marriage can only occur by mutual consent, and a bride is able to stipulate that her husband-to-be is not to take a second wife. Monogamy is by far the norm in Muslim societies, as most men cannot afford to maintain more than one family, and many of those who could would rather not. That said, polygyny remains very common across much of West Africa.

Polygamy is illegal and criminalized across Europe and the Americas, as well as in China, Australia, and other countries. Even so, there are many instances of polygamy in the West, especially within immigrant communities and certain religious groups such as the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (FLDS Church) and other Mormon fundamentalists.

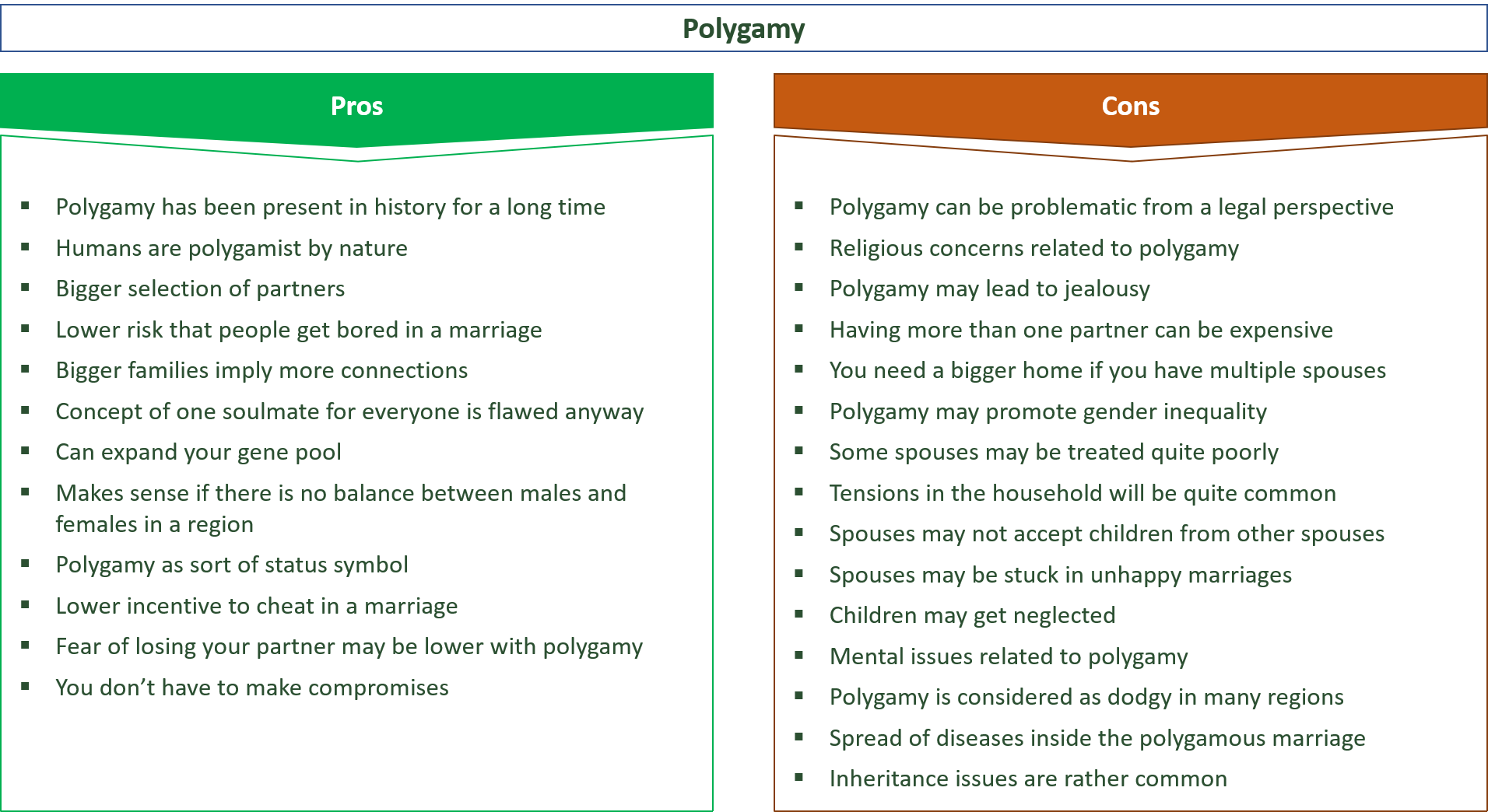

So what are the pros and cons of polygamy (or polygyny)? A man who takes more than one wife satisfies more of his sexual appetites, signals high social status, and generally feels better about himself. His many children supply him with a ready source of labour, and the means, through arranged marriages, to create multiple, reliable, and durable social, economic, and political alliances. Polygyny may be costly, but in the long term it can make a rich man richer still.

Even in monogamous societies, powerful men often establish long-term sexual relationships with women other than their wives (concubinage), although in this case the junior partners and their children born to them do not enjoy the same legal protections as the ‘legitimate’ wife and children.

Louis XIV of France, the Sun King, had a great number of mistresses, both official and unofficial. His chief mistress at any one time carried the title of maîtresse-en-titre , and the most celebrated one, Françoise-Athénaïs, Marquise de Montespan, bore him no fewer than seven children.

In some cases, a man might get divorced to marry a much younger woman (serial monogamy), thereby monopolizing the reproductive lifespan of more than one woman without suffering the social stigma of polygamy.

As I argue in my book, For Better For Worse , if divorce has become so common, it is in part because people are living for much longer, whereas in the past death would have done the job of divorce. ‘Till death do us part’ means a great deal more today than it ever did.

Polygyny might even benefit the women involved, who may come to enjoy one another’s company and share out the burdens of housekeeping and childrearing. Younger wives may add to the status and standing of the first wife, while at the same time subtracting from her responsibilities. In times of war, with high male absenteeism and mortality, polygyny supports population growth and replenishment by ensuring that every female can find a mate.

But of course, polygyny also has drawbacks, especially when viewed through a modern, Western lens.

First and foremost, polygyny sanctions and perpetuates gender inequality, with co-wives officially and patently subordinated to their husband.

Women in polygynous unions tend to marry at a younger age, into a setup that, by its very nature, fosters jealousy , competition , and conflict, with instances of co-wives poisoning one another’s offspring in a bid to further their own.

Although the husband ought in principle to treat his co-wives equally, in practice he will almost inevitably favour one over the others—most likely the youngest, most recent one.

Tensions may be reduced by establishing a clear hierarchy among the co-wives, or if the co-wives are sisters (sororal polygyny), or if they each keep a separate household (hut polygyny).

While polygyny may benefit the men involved, it denies wives to other men, especially young, low-status men, who, like all men, tend to measure their success by their manhood, that is, by the twin parameters of social status and fertility.

With little to lose or look forward to, these frustrated men are much more likely to turn to crime and violence, including sexual violence and warmongering. It is perhaps telling that polygamy is practiced in almost all of the 20 most unstable countries on the Fragile States Index.

All this is only aggravated by the brideprice, a payment from the groom to the bride’s family. Brideprice is a frequent feature of polygynous unions and is intended to compensate the bride’s family for the loss of a pair of hands.

Divorce typically requires that the brideprice be returned, leaving many women with no choice but to remain in miserable or abusive marriages.

If polygynous unions are common, the resulting shortage of brides inflates the brideprice, raising the age at which young men can afford to marry while incentivizing families to hive off their daughters at the soonest opportunity, even at the cost of interrupting their education .

Brideprice is often paid in cows, leading some young men to resort to cattle raids and other forms of crime. Gang leaders and warlords attract new recruits with the promise of a bride or an offer to cover their brideprice.

Polygyny also tends to disadvantage the offspring. On the one hand, children in polygamous families share in the genes of an alpha male and stand to benefit from his protection, resources, influence, outlook, and expertise.

But on the other hand, their mothers are younger and less educated, and they receive a divided share of their father’s attention , which may be directed at his latest wife, or at amassing resources for his next one.

They are also at greater risk of violence from their kin group, particularly the extended family. Overall, the infant mortality in polygynous families is considerably higher than in monogamous families.

So draw your own conclusions.

See my related post, " Polyamory: A New Way of Loving ."

Dupanloup I et al. (2003): A recent shift from polygyny to monogamy in humans is suggested by the analysis of worldwide Y-chromosome diversity. J Mol Evol. 57(1):85–97.

Fragile-States Index 2017. The Fund for Peace; DHS; MICS.

Neel Burton, M.D. , is a psychiatrist, philosopher, and writer who lives and teaches in Oxford, England.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Advertisement

Supported by

Ivory Tower

Love in the Time of Monogamy

- Share full article

By James Ryerson

- April 5, 2016

It’s hard to say how many people in the United States practice polygamy — estimates vary widely, from 20,000 to half a million — but it’s clear most of their fellow Americans disapprove. In a 2013 Gallup poll about morally controversial issues, a mere 14 percent of the public said they accepted polygamy (only adultery and cloning humans had lower approval rates). An earlier poll found two-thirds of the public felt the government had a right to outlaw the practice, which typically takes the form of a married man also living in a marriage-type relationship with other women. So don’t read too much into the popularity of TV shows like “Sister Wives” and “Big Love.” The country is not ready for plural marriage.

Certainly that was a bet Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. was willing to make last year. In his dissent in Obergefell v. Hodges, the Supreme Court case that recognized a right to same-sex marriage, he sought to capitalize on widespread discomfort with polygamy: “It is striking how much of the majority’s reasoning would apply with equal force to the claim of a fundamental right to plural marriage.” The majority had outlined a right to marriage that could not be constrained by historical definitions or legislative whim. But if there was nothing special, legally speaking, about the man-woman aspect of traditional marriage, what was so special about the two-person aspect?

Roberts intended his argument as a reductio ad absurdum, assuming that defenders of same-sex marriage would be alarmed by the implication. While some rose to the bait — the same-sex marriage advocate Jonathan Rauch, for example, was quick to offer arguments for why polygamy was different — other progressive thinkers, like the political philosopher Elizabeth Brake, embraced the opportunity to explore novel possibilities for marriage reform. In the essay collection AFTER MARRIAGE: Rethinking Marital Relationships (Oxford University, paper, $29.95), edited by Brake, she and nine other philosophers consider what further consequences might be implied by the principles of the same-sex-marriage movement — including, notably, the “disestablishment of marriage itself.”

As traditionally understood, a liberal state lets individuals decide for themselves, whenever possible, how to live, and so it can’t justify its policies solely by appeal to controversial moral doctrines. Yet only such doctrines, progressives have argued, could justify limiting the benefits of marriage to male-female couples (or, in an earlier era, to single-race couples). Extending this logic, Brake suggests that the same principle forbids the state to limit the benefits of marriage to romantic-love dyads — which represent just another “controversial conception of the good.” Surely, she speculates, there are other legal arrangements, less exclusive and less burdened by their history than the institution of monogamous marriage, which could offer support to adult partners, children and caregivers. Contributors to her volume entertain some possibilities: relegating marriage to private contract; replacing marriage with a parenting agreement; modeling marriage on friendship instead of romantic unions; recognizing temporary marriages (those intended to last for only a set time); and allowing polygamy.

Not all the essays are so strenuously avant-garde. One of the more nuanced pieces, by the philosopher Peter de Marneffe, articulates a liberal position on polygamy that opposes its legalization but also its criminalization. The government, according to this view, may legitimately withhold the benefits of marriage from adults in polygamous relationships (on grounds that such relationships characteristically deprive children of material and emotional resources from their father), but may not prosecute them, as is currently possible in some states, for polygamous cohabitation (because this is private consensual sexual activity). Here, de Marneffe finds himself in agreement with the law professor Deborah L. Rhode. In ADULTERY: Infidelity and the Law (Harvard University, $28.95), Rhode concludes that “perhaps the most plausible solution” to the problem of polygamy is partial legalization: invalidating criminal laws against cohabitation but retaining the prohibition on multiple marriage licenses.

In the United States, polygamy is technically a form of adultery, since it involves sexual relations between a married person and someone who is not his or her legal spouse. Adultery remains illegal in 21 states. Rhode, though no fan of adultery, argues that it should not be prohibited by law, because such laws infringe on our constitutionally protected right to privacy — and have proved woefully ineffective, in any event, at protecting the institution of marriage. Laws criminalizing polygamous cohabitation have comparable flaws, she observes.

Rhode is sympathetic to efforts to get the government out of people’s bedrooms, and she even notes that polygamy sometimes offers benefits, and not just to the men involved: “Some Mormon women consider polygamy a solution to such difficulties as single motherhood, poverty, loneliness and work/family conflicts.” And among some African-American women, she reports, an arrangement known as “man sharing” is considered a route to family stability in communities where high rates of imprisonment and unemployment have created a shortage of potential husbands. But Rhode also cites evidence of practical problems with formally legalizing polygamy. After World War II, France, looking to increase its labor supply, allowed the immigration of polygamous families from Africa — only to encounter difficulties with coerced marriages and excessive demand for government benefits.

Aside from questioning the legal status of polygamy, you might also wonder about its biological status — whether it is a “natural” state of affairs for humans. In OUT OF EDEN: The Surprising Consequences of Polygamy (Oxford University, $29.95), the evolutionary psychologist David P. Barash tackles this issue. Surveying the anthropological, biological and psychological evidence, he argues that humans, like most mammals, are not built for monogamy. Evolutionarily speaking, polygamy was the “default setting for human intimacy,” and polygyny — an arrangement in which a man mates with a harem of wives — remains our biological inclination. Barash is aware that such a claim about human nature will sound retrograde. But the facts, he insists, are the facts.

Barash cites four major pieces of evidence. The first is that in polygynous species, males are generally larger than females, because of the need to compete for access to females. The greater the degree of polygyny, the larger the size difference. (Orangutans are quite polygynous, and the male is 25 to 50 percent larger than the female; gibbons are close to monogamous, and the body sizes of males and females are roughly equal.) The size difference of male and female human beings has suggested to biologists like E.O. Wilson that humans are “moderately polygynous” by nature.

Second, in polygynous species, males are more inclined than females toward violence and physical aggression — and Barash’s analysis finds that the ratio between men and women as perpetrators of violent crime is about 10 to 1 across every state in the United States and every country with available data. The third relevant fact is that in polygynous species, females become sexually and socially mature at a younger age than males do (which is also true of humans). And finally, there is the historical record: DNA retrieved from early human fossils, for example, reveals a disparity between a low diversity of Y chromosomes (which are inherited from fathers only) and a high diversity of mitochondrial DNA (which is inherited from mothers only), suggesting that a relatively few men contributed a relatively large fraction of genetic material.

Let’s assume Barash is right and humans are polygamous by nature. So what? To his credit, Barash does not argue that because polygamy is natural it is desirable. Nor does he imply that monogamy is a stifling social convention imposed on our free animal natures. On the contrary, he notes that monogamy has many advantages as a marital lifestyle (chiefly, it better promotes paternal love and devotion). Monogamy may not be natural, he explains, but “some of the best things we do aren’t those that ‘come naturally.’ ” The trouble is that doing those unnatural things — learning a second language as an adult, avoiding sugary foods — isn’t easy. If we want to live monogamously, we will be more successful, Barash suggests, if we are honest about the biological forces we are up against.

James Ryerson is a senior staff editor for The Times’s Op-Ed page.

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

A few years ago, Harvard acquired the archive of Candida Royalle, a porn star turned pioneering director. Now, the collection has inspired a new book challenging the conventional history of the sexual revolution.

Gabriel García Márquez wanted his final novel to be destroyed. Its publication this month may stir questions about posthumous releases.

Tessa Hulls’s “Feeding Ghosts” chronicles how China’s history shaped her family. But first, she had to tackle some basics: Learn history. Learn Chinese. Learn how to draw comics.

James Baldwin wrote with the kind of clarity that was as comforting as it was chastising. His writing — pointed, critical, angry — is imbued with love. Here’s where to start with his works .

Do you want to be a better reader? Here’s some helpful advice to show you how to get the most out of your literary endeavor .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Sociology Polygamy

Monogamy And Polygamy: No Wrong Way To Love

Table of contents, introduction:, drivers for social monogamy:, infanticide, encephalization, and lactation:, sexually transmitted infections:, common features of socially monogamous species:, conclusions:, dispersal, density, and feeding:, reduced sexual dimorphism:, paternal care:, neurobiology of socially monogamous characteristics:.

*minimum deadline

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below

- Generation X

- Anthropology

Related Essays

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

- Remember me Not recommended on shared computers

Forgot your password?

Or sign in with one of these services

.thumb.jpg.78735a344a3340a866dda54f465baebb.jpg)

By Willard Marsh

By Willard Marsh • October 20, 2023

Everything You Need to Know About Monogamy Vs. Polygamy

When it comes to relationships, the words 'monogamy' and 'polygamy' often stir up strong emotions and opinions. The choice between monogamy and polygamy isn't just a matter of personal preference—it can be a complex interplay of cultural, religious, and emotional factors. If you find yourself wondering about the distinctions and implications of "polygamy vs monogamy," you're in the right place. In this article, we delve deep into these relationship styles, weighing the pros and cons, and providing expert insights to help you make an informed decision.

Whether you're single, in a relationship, or exploring new romantic avenues, understanding the fundamental differences between monogamy and polygamy can offer valuable insights into your own relational dynamics. Buckle up as we explore this fascinating topic!

Now, I'm not here to say one is better than the other. That's a subjective decision you'll have to make for yourself, based on a myriad of factors that are unique to you. But what I am here to do is lay out the facts and perspectives that can help guide you in your choice.

The topic of polygamy vs monogamy can be fraught with misunderstandings, and it's often shrouded in societal expectations and judgments. Our aim is to break through that fog and give you the clarity you need.

Before we dive into the specifics, let's set some groundwork by defining what monogamy and polygamy actually are. This is crucial because misunderstandings often arise from unclear or preconceived notions about these terms.

Let's begin, shall we?

Defining Monogamy and Polygamy

The most basic definition of monogamy involves two partners being in a romantic and/or sexual relationship exclusively with each other. Monogamy is often considered the 'norm' in many Western societies, but it's crucial to remember that this has not always been the case throughout human history or across all cultures.

Polygamy, on the other hand, involves one person having multiple spouses or partners simultaneously. There are different forms of polygamy, such as polygyny (one man, multiple wives) and polyandry (one woman, multiple husbands), and there can also be egalitarian forms where all partners are considered equal.

It's important to note that polygamy is often confused with polyamory, though the two are not the same. Polyamory is a broader term that refers to having multiple emotional or sexual relationships, with the consent and knowledge of everyone involved. Polygamy typically refers more specifically to multiple marriages or long-term commitments.

Understanding these definitions is the first step in exploring the larger implications of polygamy vs monogamy. Once we are clear on these terms, we can delve into the rich tapestry of history, society, religion, psychology, and law that further shape these relationship models.

There's often an underlying assumption that monogamy is somehow more 'natural' or 'normal' than polygamy. However, both have existed for millennia, and both have their unique sets of advantages and disadvantages, which we'll delve into in subsequent sections.

In short, neither is inherently 'better' than the other; they are simply different ways of structuring relationships. Your personal happiness and fulfillment in either will largely depend on your own values, beliefs, and needs.

Historical Context of Monogamy and Polygamy

The history of monogamy and polygamy is as diverse as the cultures that practice them. In ancient times, polygamy was relatively common, especially among rulers, nobility, and societies where the male to female ratio was skewed due to warfare. On the other hand, monogamy gained prominence as societies became more focused on individual property rights and inheritance.

In Ancient Greece and Rome, for instance, monogamy was the norm among citizens, although extramarital affairs were often tolerated for men. The rise of Christianity further entrenched monogamy as the ideal, as it was closely aligned with Christian teachings on marriage and fidelity.

However, even as monogamy became more prevalent in the West, polygamy continued to be practiced in various other parts of the world, such as Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. It's also essential to note that Indigenous cultures across the Americas had diverse marital and relational practices that included both monogamy and polygamy.

Today, monogamy is often seen as the default option in many Western societies, thanks in part to both religious influence and laws that prohibit polygamy. However, polygamous relationships are still widespread in many other parts of the world, both legally and socially accepted.

The understanding of "polygamy vs monogamy" throughout history isn't just an academic exercise. It provides context for why we might feel societal pressure to choose one over the other and why certain emotional or logistical issues may arise in either relationship style.

When weighing the pros and cons of polygamy vs monogamy, it's essential to recognize that no single approach to relationships is universally superior to the other. Both have evolved for specific societal and historical reasons, and both have their unique benefits and challenges.

Societal Perceptions: Monogamy Vs. Polygamy

Society has a significant influence on how we perceive relationships, and the societal views on monogamy and polygamy can be markedly different. In Western cultures, monogamy is often hailed as the pinnacle of emotional maturity and commitment. Polygamy, meanwhile, can be stigmatized and seen as 'lesser'—often considered either exotic or morally questionable.

This perception is deeply embedded in our media, laws, and social norms. Monogamous relationships are usually celebrated and idealized in movies, books, and TV shows, while polygamous relationships are often portrayed as problematic or confined to specific, 'exotic' cultures.

There's also a considerable amount of misinformation and stereotypes surrounding polygamy, which contributes to its stigmatization. For example, people often mistakenly conflate polygamy with a lack of commitment, exploitation, or deceit, which is not necessarily the case.

However, attitudes are slowly changing. With the rise of ethical non-monogamy and polyamory in Western society, there's a growing movement to re-examine the complexities and potential benefits of multiple partnerships. Online communities and educational resources on ethical non-monogamy have also contributed to a nuanced understanding of what polygamous relationships can look like.

If you're evaluating polygamy vs monogamy, it's vital to separate societal perceptions from the reality of each relationship style. Understand that choosing either doesn't make you more or less committed, ethical, or loving—it's all about what aligns with your values and lifestyle.

One can argue that the winds are shifting, and as they do, we might see a society that's more accepting of different forms of love and commitment. Nevertheless, it's crucial to make your relationship choices based on your own needs and not solely on societal expectations.

Pros and Cons of Monogamy

Monogamy has its distinct set of advantages and disadvantages, which can vary based on individual circumstances. One of the most cited benefits is the emotional security and intimacy that can develop between two committed partners. With only one partner to focus on, you can, in theory, build a deeper, more meaningful connection.

Additionally, monogamy often aligns with societal norms, making it easier to navigate family expectations , social functions, and even legal matters like inheritance and healthcare decisions. There's a sort of "built-in" societal support system for monogamous couples, which can make life easier in various ways.

However, monogamy is not without its challenges. For some, the exclusivity can feel stifling or limiting, leading to issues like resentment or boredom. Additionally, there's the often-mentioned issue of infidelity . The exclusivity of monogamy can sometimes lead to unrealistic expectations around sexual and emotional needs, which, when unmet, may result in one or both partners seeking fulfillment elsewhere.

It's also worth mentioning that the notion of 'forever' can be both a blessing and a curse in monogamous unions. While the commitment can provide a sense of security and continuity, it can also create pressure to make the relationship work at all costs, sometimes leading to prolonged unhealthy dynamics.

The decision to pursue monogamy should be carefully considered, with an understanding of both its potential rewards and pitfalls. Think of it not as the default option but as a choice that comes with its own set of responsibilities and challenges.

While weighing polygamy vs monogamy, it's essential to ask yourself what you're looking for in a relationship and how you envision your future. The answer to these questions can often provide a clue as to which relationship style may be more suitable for you.

Pros and Cons of Polygamy

Just as with monogamy, polygamy comes with its own set of advantages and disadvantages. One of the key benefits is the diversified emotional support and love one can receive from multiple partners. Different partners can fulfill different needs, making the relationship dynamic less susceptible to stagnation.

Polygamy also offers a broader network of support when it comes to practical matters like childcare, financial stability, and emotional support. In cultures where polygamy is socially accepted, it can also offer a sense of community and social cohesion.

However, polygamy is not without its challenges. It requires a high level of emotional intelligence, open communication, and logistical management. Balancing time, attention, and emotional resources among multiple partners can be exhausting, not to mention the possibility of jealousy and rivalry arising between partners.

Moreover, polygamous relationships often face social scrutiny and stigmatization, particularly in societies where monogamy is the norm. This societal pressure can add an additional layer of complexity, affecting your professional life, social standing, and even your legal status in some jurisdictions.

Also, it's worth mentioning that the dynamics of power and fairness can get complicated. In some forms of polygamy, like polygyny, where one man has multiple wives, there can be an unequal distribution of power, resources, and emotional support, which can lead to exploitation or neglect.

When considering polygamy vs monogamy, take time to evaluate how well you handle complex emotional dynamics and whether the benefits of multiple partnerships outweigh the challenges for you. It's not a decision to be taken lightly but should align with your personal values, lifestyle, and emotional needs.

Religious and Cultural Dimensions

The practice of monogamy or polygamy often aligns with religious or cultural beliefs, adding another layer of complexity to the decision-making process. For instance, certain branches of Christianity, Judaism, and Islam have explicit teachings about the 'correct' form of marital or relational arrangement.

In Mormonism, although mainstream Latter-day Saints have abandoned the practice, some fundamentalist groups continue to practice polygamy. Islamic traditions allow a man to have up to four wives, provided he can treat them all equally. In contrast, most Christian denominations advocate for monogamy, citing various biblical passages as the foundation of this belief.

Hinduism and Buddhism generally promote monogamy but are less prescriptive, offering room for interpretation and individual choice. Indigenous religions and African traditional religions can vary widely, with some communities practicing polygamy as a norm.

Your religious or cultural background might play a significant role in how you approach the polygamy vs monogamy debate. It's crucial to determine how much weight you give to these teachings and traditions and whether they align with your personal beliefs and circumstances.

For some, the teachings of their faith or the traditions of their culture are guiding principles that they cannot overlook. For others, personal experience and emotional needs might take precedence. There's no right or wrong approach, but it's a significant aspect to consider.

If you find yourself torn between your cultural or religious beliefs and your personal desires or needs, it may be helpful to consult with a spiritual advisor or a counselor familiar with these dimensions. Sometimes an external perspective can provide invaluable insights into what could work best for you.

Legal Implications

Before diving into either a monogamous or polygamous relationship, it's crucial to be aware of the legal ramifications , which can vary significantly depending on your jurisdiction. In many Western countries, for example, polygamy is illegal and could lead to criminal charges. Monogamous marriages, on the other hand, are not only legally recognized but often come with various benefits like tax breaks, inheritance rights, and shared healthcare plans.

Even in countries where polygamy is legal, there are often restrictions and conditions that must be met. For example, in some Islamic countries, a man must obtain the consent of his existing wife or wives before marrying another woman. Failure to meet these conditions can result in legal consequences.

Aside from formal legalities, there are also "soft" legal issues to consider. For example, in a polygamous setting, how are property and assets divided? What happens in the event of a breakup or, worse, the death of one partner ? These issues can become incredibly complicated without the guidance of legal norms or precedents.

Legal considerations should not be the sole factor in your decision, but they are crucial. Ignoring them could not only lead to legal trouble but also put emotional and financial strain on your relationships. Always consult a legal advisor familiar with family law in your jurisdiction when considering polygamy vs monogamy.

It's also wise to think about the long-term legal implications. Laws change, and social attitudes shift. What is illegal or stigmatized today might not be so in the future, and vice versa. Always stay updated on the legal landscape as it pertains to your relationship choices.

Ultimately, the legal framework surrounding monogamy and polygamy serves as another layer in an already complex decision-making process. It's essential to be aware and make informed choices to protect yourself and your loved ones.

Psychological Aspects: Jealousy, Trust, and Commitment

Both monogamy and polygamy present unique psychological challenges and rewards. One of the most discussed aspects is jealousy. Monogamous relationships aren't immune to jealousy; however, in polygamous arrangements, the emotion can become amplified as you're sharing your partner with other people. Effective communication and emotional intelligence become crucial in managing jealousy constructively.

Trust, on the other hand, plays an integral role in both relationship styles. Monogamy often provides a simplified framework for building trust as you're committing to one person. In polygamy, trust must be established with multiple partners, which can be both rewarding and challenging.

Commitment is another psychological factor that varies between these relationship types. In monogamy, commitment generally implies exclusivity. In polygamous relationships, the definition of commitment is less straightforward and can mean different things to different people. It usually involves a distinct set of boundaries agreed upon by all parties.

These psychological aspects can either be hurdles or opportunities for growth, depending on your perspective. If you're someone who values a higher level of emotional complexity, polygamy offers a playground for developing sophisticated interpersonal skills. On the flip side, if you're seeking emotional security and a more straightforward emotional landscape, monogamy might be more your speed.

It's essential to be aware of your emotional limits and needs when contemplating polygamy vs monogamy. If you have a history of insecurity or possessive tendencies, a polygamous relationship could exacerbate those issues. A mental health professional can offer valuable insights into your emotional readiness for either relationship type.

It's not uncommon for people to experiment with both monogamy and polygamy at different stages of their lives. Your psychological needs can change, and it's entirely acceptable to transition between different forms of relationships as you grow emotionally and psychologically.

Expert Opinions on Polygamy Vs. Monogamy

Experts in the field of psychology and sociology have varied opinions on the subject of polygamy vs monogamy. Dr. Helen Fisher, a biological anthropologist, argues that humans are naturally inclined toward serial monogamy, punctuated by cheating. On the other hand, Dr. Elisabeth Sheff, a sociologist who has extensively studied polyamorous families, argues that ethical non-monogamy can offer more sustainable and fulfilling relationships for some individuals.

It's worth noting that professional opinions can be influenced by cultural and individual biases, so take them as part of a larger mosaic of information. They should not replace your personal experiences or emotional needs but can offer valuable frameworks for understanding the complexities of different relationship styles.

Another facet that experts often discuss is the ethical aspect of each relationship style. Ethical monogamy and ethical non-monogamy both require consent, honesty, and mutual respect. It's not the number of partners that makes a relationship ethical or unethical, but how parties treat each other.

Despite academic debates, there's a general consensus that no one-size-fits-all answer exists. Both monogamy and polygamy have their merits and downsides, and what works for one person may not work for another. The key takeaway from expert opinions is the encouragement to introspect and choose a path that aligns with your individual circumstances.

Importantly, experts stress the necessity of open communication in any relationship model. A recurring theme in scholarly work is that communication can make or break the success of your relationship, irrespective of its structure. Expert opinions can offer a guide, but the most essential voice to listen to is your own and those of your partner or partners.

Both monogamy and polygamy come with their unique sets of challenges and benefits. Many experts stress that the most critical aspect is to be honest with yourself and your partners, whether you have one or many. Openness, communication, and respect are the pillars of any successful relationship, be it monogamous or polygamous.

Scientific Research and Statistical Data

The scientific community has also weighed in on the polygamy vs monogamy debate, although the research is often culturally and regionally specific. For instance, a study published in the Journal of Marriage and Family found that children in polygamous families experienced similar outcomes to those in monogamous families when socioeconomic factors were controlled for.

Another study, focusing on sexual health, discovered that monogamous couples reported higher levels of sexual satisfaction compared to polygamous couples, but the latter reported higher levels of emotional satisfaction. It suggests that the psychological fulfillment derived from relationships can be multi-faceted and dependent on individual expectations and needs.

It's also worth noting that evolutionary biology offers differing perspectives. Some argue that humans are naturally inclined towards monogamy because it ensures a stable environment for child-rearing. Others suggest that early human societies were likely polygamous, emphasizing the natural diversity in human mating strategies.

Statistics also play a role in understanding societal trends. According to a 2016 study published in the Archives of Sexual Behavior, younger generations are increasingly interested in forms of non-monogamy, although the majority still prefer monogamous arrangements.

Scientific research and statistical data provide valuable insights but should not dictate your personal choices. These studies offer general trends and findings, not definitive answers. Your unique circumstances, emotional needs, and life situation should be the ultimate determining factors in your choice between polygamy and monogamy.

It's also important to approach scientific studies critically. Look at who funded the study, the size and diversity of the sample, and whether the research has been peer-reviewed. These factors can influence the validity of the study and, consequently, how much weight you should give to its findings in your personal decision-making process.

Practical Tips for Choosing Between Monogamy and Polygamy

So you've absorbed the historical context, societal perspectives, expert opinions, and scientific research on polygamy vs monogamy. Now, it's time to think practically about what choice is right for you. First and foremost, let's talk about self-awareness. Take stock of your emotional needs, levels of jealousy, and desire for commitment. These are the core elements that will inform your decision.

Next, consider what you're willing to invest in terms of time and emotional labor. Polygamous relationships often require more time and emotional investment across multiple partners. Monogamous relationships are not necessarily simpler; they have their own challenges but are often less logistically complicated.

Let's also touch upon the importance of trial and error. While it might sound a bit unromantic, many people find their preference through experience. It's perfectly okay to try out both monogamy and polygamy to see what suits you better, as long as you're honest and upfront with your partners about your intentions and uncertainties.

Communication is key, no matter which path you choose. In polygamous relationships, you'll need to discuss boundaries, emotional commitments, and time allocations. In monogamous ones, conversations around exclusivity, future plans, and mutual emotional needs are vital. In both cases, openness will mitigate misunderstandings and set the foundation for a healthy relationship.

Consult external resources. Whether it's books, relationship coaches, or mental health professionals, don't hesitate to seek external guidance. The experiences and insights from others can provide you with valuable perspectives that you might not have considered.

Lastly, remember that your choice isn't irreversible. People grow and change, and so can your relationship preferences. What's crucial is to be honest—both with yourself and your partners—every step of the way. You're not locked into any decision forever, and it's okay to reassess as you move along in your life's journey.

The choice between monogamy and polygamy is a deeply personal one and varies from individual to individual. Armed with historical context, societal perceptions, expert opinions, and scientific data, you're now better equipped to make an informed decision.

Both relationship styles come with their own sets of challenges and rewards, and neither is inherently better or worse than the other. What ultimately matters is what aligns with your emotional needs, life circumstances, and personal beliefs.

One of the most significant takeaways from this exploration is the importance of self-awareness and communication. Regardless of how many partners you have or want to have, understanding yourself and talking openly with your partners are the keys to a successful and fulfilling relationship.

The debate between polygamy and monogamy is a nuanced and complex one, enriched by historical practices, religious beliefs, and contemporary societal norms. While you can draw from these various factors, remember that the most important voice in this discussion is yours.

Be aware that your choices will have implications—not just for you but for your current or future partners. Treat them with the respect and openness you would want in return. It's an ongoing process, and it's completely okay to evolve in your preferences and needs.

As you make your decision, always remember: the goal is to choose the path that offers you the most joy, fulfillment, and emotional satisfaction. Whether that path leads you to monogamy or polygamy, the most important thing is that it's yours to take.

Further Reading

1. "The Ethical Slut: A Practical Guide to Polyamory, Open Relationships & Other Adventures" by Dossie Easton and Janet W. Hardy - A seminal book that delves into the practicalities and ethics of non-monogamous relationships.

2. "Mating in Captivity: Unlocking Erotic Intelligence" by Esther Perel - This book offers a nuanced look at the complexities of sustaining desire and intimacy in long-term relationships, including monogamous ones.

3. "Sex at Dawn: How We Mate, Why We Stray, and What It Means for Modern Relationships" by Christopher Ryan and Cacilda Jethá - An anthropological take on human relationships, challenging conventional wisdom about monogamy.

User Feedback

Recommended comments.

There are no comments to display.

Create an account or sign in to comment

You need to be a member in order to leave a comment

Create an account

Sign up for a new account in our community. It's easy!

Already have an account? Sign in here.

- Notice: Some articles on enotalone.com are a collaboration between our human editors and generative AI. We prioritize accuracy and authenticity in our content.

7 Secrets to Seduce Your Husband

By Olivia Sanders , in Marriage , February 27

What is the Best Age for Getting Married?

By Gustavo Richards , in Marriage , February 17

12 Keys to Being the Perfect Wife (And Loving It!)

By Olivia Sanders , in Marriage , February 13

Why Narcissistic Husbands Don't Want Their Wives To Be Free

By Matthew Frank , in Marriage , February 9

12 Signs Your Marriage Is Really Over

By Willard Marsh , in Marriage , February 8

7 Steps to Navigate Last Name Decisions in Relationships

By Natalie Garcia , in Marriage , February 5

No intimacy in my marriage

By Notin1 , March 10 in Marriage/Long Term Relationships

- Wednesday at 06:50 PM

Sexless marriage due to husband watching gay and transexual porn

By Spellman , February 29 in Marriage/Long Term Relationships

Wife wants to explore her sexuality

By jp74 , August 31, 2023 in Marriage/Long Term Relationships

- February 14

I'm in high school, and I have been with him for over a year

By Shad07 , January 25 in Marriage/Long Term Relationships

What to do about unjust custody situation

By Viper666 , January 20 in Marriage/Long Term Relationships

- itsallgrand

Top Articles

8 flirty jokes to make her laugh (guaranteed), what does friends with benefits mean to a guy, 8 effective strategies to disarm a narcissist, 8 signs your ex still loves you.

Wednesday at 10:39 AM

rainbowsandroses · Started Wednesday at 07:43 PM

Advice4888 · Started Monday at 11:09 AM

rainbowsandroses · Started March 10

Armyguy368 · Started Thursday at 03:32 PM

- Existing user? Sign In

- Online Users

- Leaderboard

- All Activity

- Relationships

- Career & Money

- Mental Health

- Personal Growth

- Create New...

- The Magazine

- Stay Curious

- The Sciences

- Environment

- Planet Earth

Monogamous societies superior to polygamous societies

The title is rather loud and non-objective. But that seems to me to be the upshot of Henrich et al.'s The puzzle of monogamous marriage (open access). In the abstract they declare that "normative monogamy reduces crime rates, including rape, murder, assault, robbery and fraud, as well as decreasing personal abuses." Seems superior to me. As a friend of mine once observed, "If polygamy is awesome, how come polygamous societies suck so much?" Case in point is Saudi Arabia. Everyone assumes that if it didn't sit on a pile of hydrocarbons Saudi Arabia would be dirt poor and suck. As it is, it sucks, but with an oil subsidy. The founder of modern Saudi Arabia was a polygamist, as are many of his male descendants (out of ~2,000). The total number of children he fathered is unknown! (the major sons are accounted for, but if you look at the genealogies of these Arab noble families the number of daughters is always vague and flexible, because no one seems to have cared much)

So how did monogamy come to be so common? If you follow Henrich's work you will not be surprised that he posits "cultural group selection." That is, the advantage of monogamy can not be reduced just to the success of monogamous individuals within a society. On the contrary, males who enter into polygamous relationships likely have a higher fitness than monogamous males within a given culture. To get a sense of what they mean by group selection I recommend you read this review of the concept by David B. A major twist here though is that they are proposing that the selective process operates upon cultural , not genetic , variation (memes, not genes). Why does this matter? Because inter-cultural differences between two groups in competition can be very strong, and arise rather quickly, while inter-group genetic differences are usually weak due to the power of gene flow. To give an example of this, Christian societies in Northern Europe adopted normative monogamy, while pagans over the frontier did not (most marriages may have been monogamous, but elite males still entered into polygamous relationships). The cultural norm was partitioned (in theory) totally across the two groups, but there was almost no genetic difference. This means that very modest selection pressures can still work on the level of groups for culture, where they would not be effective for biological differences between groups (because those differences are so small) in relation to individual selection (within group variation would remain large).

From what I gather much of the magic of gains of economic productivity and social cohesion, and therefore military prowess, of a given set of societies (e.g., Christian Europe) in this model can be attributed to the fact of the proportion of single males. By reducing the fraction constantly scrambling for status and power so that they could become polygamists in their own right the general level of conflict was reduced in these societies. Sill, the norm of monogamy worked against the interests of elite males in a relative individual sense. Yet still, one immediately recalls that elite males in normatively monogamy societies took mistresses and engaged in serial monogamy. Additionally, there is still a scramble for mates among males in monogamous societies, though for quality and not quantity . These qualifications weaken the thesis to me, though they do not eliminate its force in totality.

In the end I am not convinced of this argument about group selection, though the survey of the empirical data on the deficiencies of societies which a higher frequency of polygamy was totally unsurprising. I recall years ago reading of a Muslim male who wondered how women would get married if men did not marry more than once. He outlined how wars mean that there will always be a deficit of males! One is curious about the arrow of causality is here; is polygamy a response to a shortage of males, or do elite polygamist make sure that there is a shortage of males? (as is the case among Mormon polygamists in the SA)

Finally, I do not think one can discount the fact that despite the long term ultimate evolutionary logic, over shorter time periods other dynamics can take advantage of proximate mechanisms. For example, humans purportedly wish to maximize fitness via our preference for sexual intercourse. But in the modern world humans have decoupled sex and reproduction, and our fitness maximizing instincts are now countervailed by our conscious preference for smaller families. Greater economic production is not swallowed up by population growth, but rather greater individual affluence. This may not persist over the long term for evolutionary reasons, but it persists long enough that it is a phenomenon worth examining. Similarly, the tendencies which make males polygamous may exist in modern monogamous males, but be channeled in other directions. One could posit that perhaps males have a preference to accumulate status. In a pre-modern society even the wealthy usually did not have many material objects. Land, livestock, and women, were clear and hard-to-fake signalers to show what a big cock you had. Therefore, polygamy was a common cultural universal evoked out of the conditions at hand. Today there are many more options on the table. My point is that one could make a group selective argument for the demographic transition, but to my knowledge that is not particularly popular. Rather, we appeal to common sense understandings of human psychology and motivation, and how they have changed over the generations.

Addendum: When I say polygamy, I mean polygyny. I would say polygyny, but then readers get confused. Also, do not confuse social preference for polygyny with lack of female power. There are two modern models of polygynous societies, the African, and the Islamic. The Islamic attitude toward women shares much with the Hindu monogamist view, while in African societies women are much more independent economic actors, albeit within a patriarchal context. The authors note that this distinction is important, because it seems monogamy (e.g., Japan) is a better predictor of social capital than gender equality as such, despite the correlation.

Citation: Joseph Henrich, Robert Boyd, and Peter J. Richerson, The puzzle of monogamous marriage, Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B March 5, 2012 367 (1589) 657-669; doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0290

Already a subscriber?

Register or Log In

Keep reading for as low as $1.99!

Sign up for our weekly science updates.

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Polygamy vs Monogamy: Unraveling the Complexities of Relationship Structures

I’ve always found the topic of monogamy versus polygamy fascinating. It’s one of those subjects that can evoke strong feelings and heated debates. But before we dive into this complex issue, let’s first define what we mean by these terms. Monogamy refers to the practice or state of having a relationship with only one partner at a time, while polygamy , on the other hand, involves being married to more than one person.

In today’s society, monogamy is mostly accepted as the norm. We’re raised with fairy tales and romantic movies that champion the idea of finding ‘the one.’ Yet it’s important to remember that polygamous societies have existed since ancient times and are still prevalent in some parts of the world today.

It’s crucial for me to clarify early on that this discussion isn’t about advocating for one form over another. Instead, I’ll explore both sides objectively so you can gain a better understanding of these two different ways people choose to live their lives.

Understanding Polygamy: A Detailed Overview

Let’s dive right in. Polygamy, to put it simply, is the practice of having more than one spouse at a time. It’s been around for centuries and is still practiced in several cultures globally today.

Historically, polygamy often took the form of polygyny – where a man has multiple wives. This was common in societies where resources were abundant but labor was scarce. Men with many wives could have more children, which meant more hands to work the land or herd livestock.

However, polyandry – when a woman has multiple husbands – also exists but it’s far less common compared to polygyny. It typically occurs in regions with scarce resources where sharing a wife can help limit population growth and share resource burdens.

Polyamory is another modern twist on polygamy that differs from traditional forms because it emphasizes emotional relationships over marital status. In this setup, individuals may have multiple partners but not necessarily be married to all of them.

Now let’s look at some numbers:

It’s important to note that there are legal and social implications tied up with these practices too:

- In most Western societies today, including the US and Europe, monogamous marriages are legally recognized while polygamist unions aren’t.

- There are exceptions though – like among certain religious groups who continue these practices despite legal challenges.

This quick overview should give you an understanding of what exactly we mean by ‘polygamy. We’ll delve deeper into its societal impacts as well as how it compares with monogamy in subsequent sections!

The Practice of Monogamy and Its Origins

Monogamy’s roots are as complex as they are fascinating. I’ve seen it in my research time and again: monogamy isn’t a human invention, but rather, a natural occurrence we share with many other species. For example, certain types of birds like swans or albatrosses are famously monogamous.

Delving into anthropology and history, evidence suggests that early humans weren’t strictly monogamous. Some societies practiced polygyny (one man marrying multiple women), while others were more egalitarian, resembling what we’d call ‘serial monogamy’ today.

But let’s not forget our primate cousins! Looking at their behavior can provide some insight into the origins of human monogamy. While most primate species aren’t strictly monogamous, gibbons stand out with their pair-bonding habit. Could this be an echo of our ancestral practices?

On to sociology now: modern society has been largely shaped by monotheistic religions which promote the idea of one man-one woman unions—monogamy as we know it today. It’s worth noting though that even within these societies there is diversity. Some individuals practice serial monogamy—entering into one committed relationship after another—while others choose lifelong partnerships.

And finally, psychology gives us another perspective on why humans might opt for monogamous relationships. Emotional security, economic stability and mutual support are some reasons often cited.

It’s clear that the practice of monogamy has deep roots entwined in biology, history and culture alike—a testament to its adaptability across different times and contexts.

Polygamy Vs Monogamy: Key Differences

When we’re talking about marriage structures, it’s hard to ignore the stark contrast between polygamy and monogamy. They are indeed two poles apart in how they shape family dynamics, societal norms, and personal relationships.

Polygamy involves a person being married to more than one spouse simultaneously. It’s an age-old practice seen across many cultures globally. For instance, certain African and Middle Eastern societies have long histories of polygamous marriages. The reasoning behind this varies – some see it as a status symbol while others view it as an economic necessity.

On the other hand, monogamy represents a union between two individuals exclusively. I’ve noticed that this form of marriage is predominant in Western societies due to religious beliefs and legal restrictions. People often choose this path seeking emotional intimacy and stability with one partner.

Here are some key differences between these two marital structures:

- Number of Partners : In polygamy, there’s no limit to the number of spouses one can have at once. Conversely, monogamous relationships strictly involve only two partners.

- Societal Acceptance : Monogamous unions are widely accepted around the globe whereas polygamous marriages often face societal scrutiny or legal prohibitions.

- Family Structure : Families in polygamous setups tend to be larger with complex dynamics while those in monogamous arrangements usually consist of smaller nuclear families.

It’s important to remember that neither structure is inherently ‘better’ than the other; each has its own merits and challenges based on individual preferences and cultural contexts. Moreover, both require mutual consent, respect, understanding, communication for them to be healthy and successful relationships .

Regardless of our personal views on these contrasting marital forms – whether we deem one superior over another – their existence provides us with rich insights into human behavior and cultural diversity worldwide.

Cultural Perspectives on Polygamy and Monogamy

It’s fascinating to see how different cultures approach the idea of marriage. In some parts of the world, polygamy is accepted and even encouraged, while in others it’s seen as a violation of human rights. On the flip side, monogamy is widely praised in Western societies but can be viewed as restrictive or unnatural elsewhere. So let’s dive into these perspectives.

In many African cultures, for example, polygamy was traditionally practiced and continues to this day. For them, it’s not so much about romance but more about social economics. They see having multiple wives as a status symbol or means of wealth accumulation.

- Uganda: 28%

- Tanzania: 31%

On the other hand, monogamy is deeply rooted in Western culture stemming from religious beliefs primarily Christianity which promotes fidelity within marriage.

However in some Middle Eastern and Asian countries where Islam is prevalent, polygamy is allowed though rarely practiced due to economic constraints.

Then there are indigenous tribes such as those found in Amazonian regions that practice both depending on their societal rules and norms.

What stands out when comparing these cultural views on monogamy and polygamy isn’t necessarily who’s right or wrong – because morality can often be subjective – but rather understanding why certain practices exist based on historical contexts and societal needs.

It’s intriguing how something as intimate as marriage can vary so vastly across different landscapes yet at its core remains a universal institution binding individuals together under various terms.

Psychological Impacts of Polygamous and Monogamous Relationships

Diving into the world of relationships, it’s impossible to ignore the psychological impacts they have on us. When we talk about polygamy and monogamy, there are distinct differences in how they shape our mental states.

Strutting down the path of polygamy might seem like a route paved with endless possibilities. After all, having multiple partners can mean more support, affection, and perspectives. But there’s a flip side to this coin. I’ve seen data that suggests individuals in polygamous relationships often grapple with feelings of jealousy and inadequacy. There’s also the potential for increased stress due to juggling multiple relationship dynamics simultaneously.

On the other hand, monogamy offers its own unique psychological impacts. The security provided by a single committed partner may lead to greater overall satisfaction and happiness for some people. However, others might feel constrained or unfulfilled in their desire for variety or new experiences.

Beyond these general observations, it’s crucial to point out that every person is unique – your experience with either form of relationship may vary greatly based on your individual personality traits . For instance:

- If you’re someone who highly values stability and predictability – you might find greater comfort in monogamous relationships.

- Conversely, if freedom and variety are important to you – polygamy could be more fulfilling.

All said though, it’s critical not to forget that good communication remains key regardless of whether you’re navigating through waves in a monogamous or polygamous sea. In my opinion, a successful relationship isn’t defined by the number of partners involved but by the quality of connection and understanding between them.

Legalities Around Polygamy and Monogamy Worldwide

When it comes to the legal status of monogamy and polygamy worldwide, there’s quite a varied landscape. Let’s start with monogamy. It’s practically the norm in many parts of the world – North America, Europe, Australia, for instance. Laws in these regions generally support one-man-one-woman unions, reflecting how entrenched monogamy is in their cultures.

Polygamy, on the other hand, presents a more complex picture. In some nations like India and Sri Lanka, polygamous marriages are allowed only for Muslims but not for other religious communities. Meanwhile, certain African countries such as Kenya have laws that permit men to marry multiple wives.

However, there are also countries where polygamy is outright illegal. For example:

- United States: Any form of polygamous relationship is considered against federal law.

- China: Criminal Code prohibits plural marriage.

- France: The French Civil Code does not recognize polygamous unions.

It gets trickier when you consider places like Canada or Russia where polygamy isn’t explicitly criminalized but isn’t exactly legal either – they fall into what we might call grey areas legally.

The following points summarize this situation even further:

- Most Western societies legally endorse monogamous marriages only

- Some Eastern and African countries allow both types of marriages under specific circumstances

- There exist few ‘grey areas’ where neither practice is explicitly criminalized

So it becomes apparent that laws around marital practices vary greatly depending on cultural norms and societal beliefs within each country. As we’ve seen here – from outright illegality to tacit acceptance – the legalities around polygamy and monogamy worldwide are as diverse as the cultures they stem from.

Societal Acceptance: From Polygamy to Monogamy

I’ve been diving into the societal acceptance of polygamy and monogamy, and it’s clear that views have shifted significantly over time. Let’s look at how attitudes have evolved from a preference for one to the other.

In ancient times, polygamy was relatively common. Many societies saw it as beneficial for various reasons. For instance:

- It allowed wealthy men to produce more offspring.

- Provided economic advantages by merging multiple families’ resources.

- Gave widows and orphans a social safety net in the absence of government support systems.

However, as we moved towards the modern era, monogamy started gaining popularity. Some factors contributing to this shift include:

- The rise of individualism leading people to value emotional intimacy with a single partner.

- Increased urbanization making large families impractical due to space constraints.

- Legal restrictions implemented by various governments around the world against polygamous marriages.

Nowadays, I’m sure you’ll notice that most societies predominantly practice monogamy. According to Pew Research Center, only 2% of cultures worldwide openly support polygamy today.

Yet, it’s crucial not to overlook pockets where polygamous practices still occur – often tied up with religious beliefs or cultural traditions. On an ending note though, no matter what society’s stance is on these marital structures – be it polygamous or monogamous – what remains paramount is mutual respect and consent among all parties involved.

Concluding Thoughts on Polygamy Vs Monogamy

Let’s wrap up our discussion on polygamy versus monogamy. Our journey into these contrasting marital systems has been enlightening, to say the least.

Polygamy, with its roots in various cultures and religions worldwide, offers multiple partners. This arrangement can provide a larger support network, diversified companionship, and potentially more financial stability. However, it’s also fraught with complications such as potential favoritism, jealousy among co-spouses, and complex family dynamics.

On the other hand, we have monogamy – the more prevalent form of marriage globally. It’s deeply ingrained in many societies as the ‘norm’ or ‘standard’. Its benefits include a focused relationship between two individuals, fewer complexities compared to polygamous relationships and is generally less controversial from a social perspective. Yet it too has its challenges like dependency on a single partner for emotional and financial support.

Here’s a brief comparison:

So which is better? Well that boils down to personal preference and cultural context. For some people polygamous relationships work perfectly well while others find solace in monogamous unions.

Both systems have their pros & cons so ultimately it’s about what suits you best as an individual or couple considering your circumstances goals values emotions societal norms religious beliefs etc

In truth there isn’t a definitive answer as human experiences vary widely depending upon numerous factors including individual personality sociocultural context personal beliefs and so on.

It’s essential to respect each person’s choice in this matter as long as it involves consent from all parties involved and is not detrimental to anyone’s wellbeing. After all, the goal of any relationship should be mutual happiness, love, respect, and understanding.

This has been a fascinating exploration into polygamy versus monogamy. Remember that no one size fits all in matters of the heart. What works for one may not work for another, so let’s keep an open mind about different forms of relationships while ensuring they’re healthy and respectful!

Related Posts

The Male Mind in Love: Demystifying Men’s Love Journey

Loving You: To the Moon & Back – A Journey of Endless Love

- United Kingdom

- United States

1 Married Woman & 1 Single Man Debate Monogamy

The pros & cons of staying with one person for the rest of your life, more from sex & relationships.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci

- v.22(1); 2013 Mar

The impact of polygamy on women's mental health: a systematic review

L. d. shepard.