Research Topics & Ideas: Sociology

50 Topic Ideas To Kickstart Your Research Project

If you’re just starting out exploring sociology-related topics for your dissertation, thesis or research project, you’ve come to the right place. In this post, we’ll help kickstart your research by providing a hearty list of research ideas , including real-world examples from recent sociological studies.

PS – This is just the start…

We know it’s exciting to run through a list of research topics, but please keep in mind that this list is just a starting point . These topic ideas provided here are intentionally broad and generic , so keep in mind that you will need to develop them further. Nevertheless, they should inspire some ideas for your project.

To develop a suitable research topic, you’ll need to identify a clear and convincing research gap , and a viable plan to fill that gap. If this sounds foreign to you, check out our free research topic webinar that explores how to find and refine a high-quality research topic, from scratch. Alternatively, consider our 1-on-1 coaching service .

Sociology-Related Research Topics

- Analyzing the social impact of income inequality on urban gentrification.

- Investigating the effects of social media on family dynamics in the digital age.

- The role of cultural factors in shaping dietary habits among different ethnic groups.

- Analyzing the impact of globalization on indigenous communities.

- Investigating the sociological factors behind the rise of populist politics in Europe.

- The effect of neighborhood environment on adolescent development and behavior.

- Analyzing the social implications of artificial intelligence on workforce dynamics.

- Investigating the impact of urbanization on traditional social structures.

- The role of religion in shaping social attitudes towards LGBTQ+ rights.

- Analyzing the sociological aspects of mental health stigma in the workplace.

- Investigating the impact of migration on family structures in immigrant communities.

- The effect of economic recessions on social class mobility.

- Analyzing the role of social networks in the spread of disinformation.

- Investigating the societal response to climate change and environmental crises.

- The role of media representation in shaping public perceptions of crime.

- Analyzing the sociocultural factors influencing consumer behavior.

- Investigating the social dynamics of multigenerational households.

- The impact of educational policies on social inequality.

- Analyzing the social determinants of health disparities in urban areas.

- Investigating the effects of urban green spaces on community well-being.

- The role of social movements in shaping public policy.

- Analyzing the impact of social welfare systems on poverty alleviation.

- Investigating the sociological aspects of aging populations in developed countries.

- The role of community engagement in local governance.

- Analyzing the social effects of mass surveillance technologies.

Sociology Research Ideas (Continued)

- Investigating the impact of gentrification on small businesses and local economies.

- The role of cultural festivals in fostering community cohesion.

- Analyzing the societal impacts of long-term unemployment.

- Investigating the role of education in cultural integration processes.

- The impact of social media on youth identity and self-expression.

- Analyzing the sociological factors influencing drug abuse and addiction.

- Investigating the role of urban planning in promoting social integration.

- The impact of tourism on local communities and cultural preservation.

- Analyzing the social dynamics of protest movements and civil unrest.

- Investigating the role of language in cultural identity and social cohesion.

- The impact of international trade policies on local labor markets.

- Analyzing the role of sports in promoting social inclusion and community development.

- Investigating the impact of housing policies on homelessness.

- The role of public transport systems in shaping urban social life.

- Analyzing the social consequences of technological disruption in traditional industries.

- Investigating the sociological implications of telecommuting and remote work trends.

- The impact of social policies on gender equality and women’s rights.

- Analyzing the role of social entrepreneurship in addressing societal challenges.

- Investigating the effects of urban renewal projects on community identity.

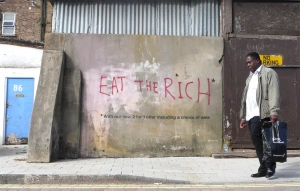

- The role of public art in urban regeneration and social commentary.

- Analyzing the impact of cultural diversity on education systems.

- Investigating the sociological factors driving political apathy among young adults.

- The role of community-based organizations in addressing urban poverty.

- Analyzing the social impacts of large-scale sporting events on host cities.

- Investigating the sociological dimensions of food insecurity in affluent societies.

Recent Studies & Publications: Sociology

While the ideas we’ve presented above are a decent starting point for finding a research topic, they are fairly generic and non-specific. So, it helps to look at actual sociology-related studies to see how this all comes together in practice.

Below, we’ve included a selection of recent studies to help refine your thinking. These are actual studies, so they can provide some useful insight as to what a research topic looks like in practice.

- Social system learning process (Subekti et al., 2022)

- Sociography: Writing Differently (Kilby & Gilloch, 2022)

- The Future of ‘Digital Research’ (Cipolla, 2022).

- A sociological approach of literature in Leo N. Tolstoy’s short story God Sees the Truth, But Waits (Larasati & Irmawati, 2022)

- Teaching methods of sociology research and social work to students at Vietnam Trade Union University (Huu, 2022)

- Ideology and the New Social Movements (Scott, 2023)

- The sociological craft through the lens of theatre (Holgersson, 2022).

- An Essay on Sociological Thinking, Sociological Thought and the Relationship of a Sociologist (Sönmez & Sucu, 2022)

- How Can Theories Represent Social Phenomena? (Fuhse, 2022)

- Hyperscanning and the Future of Neurosociology (TenHouten et al., 2022)

- Sociology of Wisdom: The Present and Perspectives (Jijyan et al., 2022). Collective Memory (Halbwachs & Coser, 2022)

- Sociology as a scientific discipline: the post-positivist conception of J. Alexander and P. Kolomi (Vorona, 2022)

- Murder by Usury and Organised Denial: A critical realist perspective on the liberating paradigm shift from psychopathic dominance towards human civilisation (Priels, 2022)

- Analysis of Corruption Justice In The Perspective of Legal Sociology (Hayfa & Kansil, 2023)

- Contributions to the Study of Sociology of Education: Classical Authors (Quentin & Sophie, 2022)

- Inequality without Groups: Contemporary Theories of Categories, Intersectional Typicality, and the Disaggregation of Difference (Monk, 2022)

As you can see, these research topics are a lot more focused than the generic topic ideas we presented earlier. So, for you to develop a high-quality research topic, you’ll need to get specific and laser-focused on a specific context with specific variables of interest. In the video below, we explore some other important things you’ll need to consider when crafting your research topic.

Get 1-On-1 Help

If you’re still unsure about how to find a quality research topic, check out our Research Topic Kickstarter service, which is the perfect starting point for developing a unique, well-justified research topic.

You Might Also Like:

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Translators

- Graphic Designers

Please enter the email address you used for your account. Your sign in information will be sent to your email address after it has been verified.

100 Sociology Research Topics You Can Use Right Now

Sociology is a study of society, relationships, and culture. It can include multiple topics—ranging from class and social mobility to the Internet and marriage traditions. Research in sociology is used to inform policy makers, educators, businesses, social workers, non-profits, etc.

Below are 100 sociology research topics you can use right now, divided by general topic headings. Feel free to adapt these according to your specific interest. You'll always conduct more thorough and informed research if it's a topic you're passionate about.

Art, Food, Music, and Culture

- Does art imitate life or does life imitate art?

- How has globalization changed local culture?

- What role does food play in cultural identity?

- Does technology use affect people's eating habits?

- How has fast food affected society?

- How can clean eating change a person's life for the better?

- Should high-sugar drinks be banned from school campuses?

- How can travel change a person for the better?

- How does music affect the thoughts and actions of teenagers?

- Should performance artists be held partially responsible if someone is inspired by their music to commit a crime?

- What are some examples of cultural misappropriation?

- What role does music play in cultural identity?

Social Solutions and Cultural Biases

- What (if any) are the limits of free speech in a civil society?

- What are some reasonable solutions to overpopulation?

- What are some ways in which different types of media content influence society's attitudes and behaviors?

- What is the solution to stop the rise of homegrown terrorism in the U.S.?

- Should prescription drug companies be allowed to advertise directly to consumers?

- Is the global warming movement a hoax? Why or why not?

- Should the drinking age be lowered?

- Should more gun control laws be enacted in the U.S.?

- What bias exists against people who are obese?

- Should polygamy be legal in the U.S.? Why or why not?

- Should there be a legal penalty for using racial slurs?

- Should the legal working age of young people be raised or lowered?

- Should the death penalty be used in all cases involving first-degree murder?

- Should prisons be privately owned? Why or why not?

- What is privilege? How is it defined and how can it be used to gain access to American politics and positions of power?

- How are women discriminated against in the workplace?

- What role does feminism play in current American politics?

- What makes a patriot?

- Compare/analyze the social views of Plato and Aristotle

- How has labor migration changed America?

- What important skills have been lost in an industrialized West?

- Is the #MeToo movement an important one? Why or why not?

- What conflict resolution skills would best serve us in the present times?

- How can violence against women be dealt with to lower incidence rates?

- Should students be allowed to take any subject they want in High School and avoid the ones they don't like?

- How should bullies be dealt with in our country's schools?

- Do standardized tests improve education or have the opposite effect?

- Should school children be forced to go through metal detectors?

- What is the best teacher/student ratio for enhanced learning in school?

- Do school uniforms decrease teasing and bullying? If so, how?

- Should teachers make more money?

- Should public education be handled through private enterprises (like charter schools)?

- Should religious education be given priority over academic knowledge?

- How can schools help impoverished students in ways that won't embarrass them?

- What are ethical values that should be considered in education?

- Is it the state's role or the parents' role to educate children? Or a combination of both?

- Should education be given more political priority than defense and war?

- What would a perfect educational setting look like? How would it operate and what subjects would be taught?

Marriage and Family

- How should a "family" be defined? Can it be multiple definitions?

- What is a traditional role taken on by women that would be better handled by a man (and vice versa)?

- How has marriage changed in the United States?

- What are the effects of divorce on children?

- Is there a negative effect on children who are adopted by a family whose ethnicity is different than their own?

- Can children receive all they need from a single parent?

- Does helicopter parenting negatively affect children?

- Is marriage outdated?

- Should teens have access to birth control without their parents' permission?

- Should children be forced to show physical affection (hugs, etc.) to family members they're uncomfortable around?

- What are the benefits (or negative impact) of maintaining traditional gender roles in a family?

- Are social networks safe for preteens and teens? Why or why not?

- Should the government have a say in who can get married?

- What (if any) are the benefits of arranged marriages?

- What are the benefits for (or negative impact on) children being adopted by LGBTQ couples?

- How long should two people date before they marry?

- Should children be forced to be involved in activities (such as sports, gymnastics, clubs, etc.), even when they'd rather sit at home and play video games all day?

- Should parents be required to take a parenting class before having children?

- What are potential benefits to being married but choosing not to have children?

Generational

- Should communities take better care of their elderly? How?

- What are some generational differences among Generations X, Y, and Z?

- What benefits do elderly people get from interaction with children?

- How has Generation Y changed the country so far?

- What are the differences in communication styles between Generation X and Generation Y (Millennials)?

- Why could we learn from our elders that could not be learned from books?

- Should the elderly live with their immediate family (children and grandchildren)? How would this resolve some of our country's current problems?

- What are some positive or negative consequences to intergenerational marriage?

Spiritualism, religion, and superstition

- Why do some people believe in magic?

- What is the difference between religion and spiritualism?

- Should a government be a theocracy? Why or why not?

- How has religion helped (or harmed) our country?

- Should religious leaders be able to support a particular candidate from their pulpit?

- How have religious cults shaped the nation?

- Should students at religious schools be forced to take state tests?

- How has our human connection with nature changed while being trapped in crowded cities?

- Which generation from the past 200 years made the biggest impact on culture with their religious practice and beliefs? Explain your answer.

Addiction and Mental Health

- How should our society deal with addicts?

- What are ethical values that should be considered in mental health treatment?

- Should mental health be required coverage on all insurance policies?

- Is mental health treatment becoming less stigmatized?

- How would better access to mental health change our country?

- What are some things we're addicted to as a society that are not seen as "addiction," per se?

- Should medicinal marijuana be made legal?

- What are some alternative treatments for mental health and wellness instead of antidepressants?

- Has social media helped or harmed our society?

- Are video games addictive for young people and what should be done to curb the addiction?

- Should all recreational drugs be made legal?

- How has mental health treatment changed in the past 20 years?

- Should recreational marijuana be made legal?

- How is family counseling a good option for families going through conflict?

Related Posts

The Best Resources for Academic Presentation Templates

Graduate-level Writing Advice: Expectations and Tips

- Academic Writing Advice

- All Blog Posts

- Writing Advice

- Admissions Writing Advice

- Book Writing Advice

- Short Story Advice

- Employment Writing Advice

- Business Writing Advice

- Web Content Advice

- Article Writing Advice

- Magazine Writing Advice

- Grammar Advice

- Dialect Advice

- Editing Advice

- Freelance Advice

- Legal Writing Advice

- Poetry Advice

- Graphic Design Advice

- Logo Design Advice

- Translation Advice

- Blog Reviews

- Short Story Award Winners

- Scholarship Winners

Need an academic editor before submitting your work?

What is Applied Sociology?

A brief introduction on applied sociology.

By Dr Zuleyka Zevallos, 23 May 2009. 1

The aim of this article is to broadly sketch what it means to be working as an applied sociologist. I begin with a general introduction into the discipline of sociology, before providing a definition of its applied branch. I then provide a concise background history of the different practices that might be considered under the rubric of ‘applied sociology’. Lastly, I present an outline of the professional skills that a degree in sociology can offer its graduates.

My discussion on applied sociology refers to those professionals who use the principles of sociology outside a university setting in order to provide their clients with an in-depth understanding of some specific facet of society that requires information gathering and analysis.

Applied sociologists work in various industries, including private business, government agencies and not-for-profit organisations. The work of applied sociologists is especially concerned with changing the current state of social life for the better. This can include anything from increasing the health and wellbeing of a disadvantaged community group; working with law enforcement organisations to implement a rehabilitation program for criminal offenders; assisting in planning for natural disasters; and enhancing existing government programs and policies.

I will show that a degree in sociology has several career benefits, but I specifically focus on the strong communication, research and interpersonal skills that prove advantageous to sociology graduates looking for work. I argue that applied sociology can help to improve any professional sector that might benefit from a critical evaluation of how a particular social issue, group or organisation works.

What is Sociology?

In a very general sense, sociology can be defined as the study of ‘the bases of social membership’ (Abercrombie, Hill and Turner 2000: 333). That is, sociology is the study of what it means to be a member of a particular society, and it involves the critical analysis of the different types of social connections and social structures that constitute a society. This includes questions about how and why different groups are formed and the various meanings attached to different modes of social interaction, such as between individuals or social networks; face to face versus online communications; local and global discourses, and so on.

Sociology also encompasses the study of the social institutions that shape social action. A social institution is a complex, but distinctive, sub-system of society that regulates human conduct (Berger 1963: 87). For example, the media acts as a social institution that can influence the way in which ‘facts’ are represented and interpreted; the law and politics impact on the ways in which different cultural groups define what is deemed ‘right’ and ‘moral’; the institutions of economy and education affect social status (that is, wealth and inequality among individuals); and the institution of family shapes our ideas about partnership, work, gender, sex, childrearing, and our bodies, as well as various other aspects of our lives.

Sociology can therefore be used to study all the social experiences that human beings are capable of imagining – from practices of childbirth, to the use technologies, to our attitudes and rituals regarding death – and everything else in between. People usually understand their problems in reference to their own personal life story and they are not always aware of the complex links between their own lives and the rest of the world’s history (Mills 1959: 5). The ‘sociological imagination’ helps us to make sense of the connections between history, biography and place (Mills 1959: 6).

Sociology allows us to study individual behaviour in a broader context, to take into consideration how societal forces might impact upon individuals, as well as the ways in which individuals construct the world around them, and how they manage to resist existing power relationships in order to achieve social change. In this light, sociology represents ‘a transformation of consciousness’ (Berger 1963: 21).

Sociology questions taken-for-granted assumptions about the world we live in (what we see as ‘familiar’ and ‘normal’ within the context of our everyday lives), and it provides a new and more critical perspective of the world, through the use of scientific theories, concepts and empirical evidence.

Sociology is often perceived as an academic profession, but there are many places outside of universities where sociology can be used to enhance personal and professional development.

A definition of applied sociology

Applied sociology is a term that describes practitioners who use sociological theories and methods outside of academic settings with the aim to ‘produce positive social change through active intervention’ (Bruhn 1999: 1). More specifically, applied sociology might be seen as the translation of sociological theory into practice for specific clients. That is, this term describes the use of sociological knowledge in answering research questions or problems as defined by specific interest groups, rather than the researcher (Steele and Price 2007: 4).

Applied research is sometimes conducted within a multidisciplinary environment and in collaboration with different organisations, including community services, activist groups and sometimes in partnership with universities. Some applied sociologists may not explicitly use sociological theories or methods in their work, but they may use their sociological training more broadly to inform their work and their thinking.

I will now go on to provide a broad overview of the history of applied sociology, including some of the professional roles that sociologists have traditionally taken on, and the variations of sociological practices that exist today.

History and applications of sociological practice

Harry Perlstadt (2007) traces the history of applied sociology to 1850, and the work of Auguste Comte, one of sociology’s founding figures. Perlstadt writes that Comte divided the discipline of sociology in two parts: social statics , the study of social order, and social dynamics , the study of social progress and development (2004: 342-343). Perlstadt argues that Comte’s theory lends itself to two types of sociologies: ‘basic research’ and social interventionism.

Basic researchers educate and influence public debate, and social interventionists are political activists who are responsible for actively enforcing social change (2004: 343). According to Perlstadt, Comte saw applied researchers as occupying a ‘ translational role ’ in-between these two positions. Nevertheless, almost 160 years later, there remains a long-standing divide between the so-called ‘pure’ and ‘practical’ research traditions in sociology. While these differences may appear to be artificial, ambivalence persists between academic and applied sociologies, despite the fluidity and intersections between these practices (see Gouldner 1965; DeMartini 1982; Rossi 1980).

Roles for Practitioners

Hans Zetterberg (1964) argues that ‘practical’ sociological knowledge might be distinguished into five roles: decision-maker, educator, social critic, researcher for clients, and consultant. First, the sociologist as decision-maker is someone who uses social science in order to shape policy decisions (1964: 57-58).

The sociologist as an educator is a person who teaches sociology to students, typically in a university setting (1964: 28-60), although sociology is now increasingly taught in high schools and as part of specialist courses.

The sociologist as a commentator and social critic is someone who writes for a wider public through books and articles aimed at an educated public, with a view of influencing public opinion (1964: 61-62).

The sociologist as researcher for clients might be someone who works with public or private organisations, such as mental health groups, banks, or some other company that commissions research on very specific topics (1964: 61-62).

Finally, the sociologist who acts as a consultant works to answer a specific and practical problem as defined by a particular client, using their client’s language and by making specific reference to their client’s problem, rather than a broader social problem or grand social theory (1964: 62-63).

Zetterberg positions applied sociologists as fulfilling the latter two roles: client work and consultancy .

Variations of Applied Sociological Practices

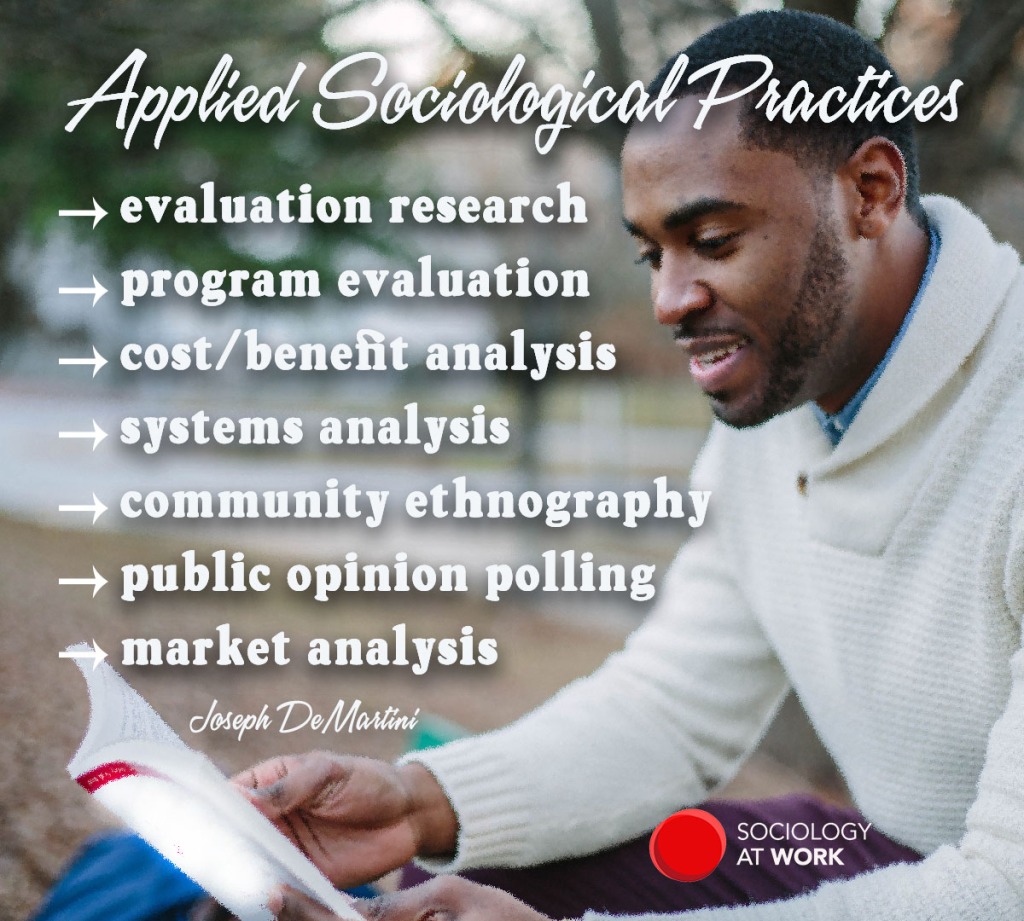

Joseph DeMartini (1979) identifies that applied sociology can take on two variations. First, applied researchers might use basic empirical methods in collecting information in order to help shape informed decisions, such as in the creation of social policy. In this meaning, sociologists might be directly working within government agencies, or they might work for private research organisations, or they might be contracted for one or the other. He lists the following activities as examples of this applied methodological approach:

‘evaluation research, program evaluation, cost/benefit analysis, systems analysis, community ethnography, public opinion polling, and market analysis’ (1979: 333).

While these sociologists might employ scientific theories and concepts, their specialisation is actually the application of sociological research techniques in order to gather specific information, rather than the application of sociological theories per se (1979: 334).

Second, applied researchers might be employed more specifically for their knowledge of sociological concepts and theories in order to help their clients better understand a narrowly defined issue. Activities might include assessing the determinants of observed phenomena, such as the causes of crime, explaining demographic changes, and evaluating the shifts in social movements.

Alternatively, applied sociologists might propose a course of action in order to achieve targeted change, such as by increasing the economic outcomes of a disadvantaged community, reforming illegal behaviours, or developing a framework in order to prepare a local community in the advent of a natural disaster (1979: 334).

To clarify the distinction between these two applied practices, DeMartini uses the example of social policy: in the first case, where methods take primacy, applied sociological research techniques are employed in order to create and inform new social policies; in the second instance, where theories and concepts have greater relevance to the clients, applied sociological knowledge is used to evaluate existing social policies.

DeMartini notes, however, that this differentiation is for illustration purposes, and that, in fact, applied practices run along a continuum in between these two practices (1979: 333). Methods and theories cannot be used in isolation, but some jobs might require more emphasis on one than the other.

Distinguishing Academic and Applied Sociology

Howard Freeman and Peter Rossi (1984) argue that the application of sociological knowledge is different for academic and applied sociologists. They see that some of the work that academics do might be considered to be ‘applied’, particularly as universities are seeking more external revenue, and so they encourage academics to carry out contract work. Nevertheless, by and large, Freeman and Rossi see that academic and applied sociologists are distinguished in six ways.

First, applied sociologists’ careers rely less on publishing in academic journals, and, instead, they focus more on the utility of their work to a specialised (non-academic) audience . Since, they are hired by external stakeholders, their rewards are judged by their sponsors, on the basis of whether these clients see the work as being useful to them (1984: 572). Academics rely more on peer-evaluations, and there is high prestige in publishing in academic journals.

Second, Freeman and Rossi argue that applied sociologists have narrow constraints on their time and the specificity of their work outputs , while academic sociologists are more free to choose their research topic (notwithstanding the politics of grant funding and the publishing potential of certain topics) (1984: 572-573).

Third, applied sociologists adhere to ‘absolute norms’ of rigorous scholarship ‘only to the extent necessary to achieve usable results ‘ (1984: 573; my emphasis). There is sometimes a swift turnover expected of the work by applied researchers, while academics generally have a longer time-frame with which to develop their scholarship.

Fourth, applied sociologists are more concerned with ‘external validity’, that is, the extent to which their conclusions speak directly to their specific client’s topic area , rather than to some general social problem or broader group. Academics tend to focus more on ‘internal validity’ – to making a contribution to the academic literature, and the judgements of their peers (1984: 573).

Fifth, applied sociologists are driven by the ‘ practical payoffs’ of their activities, such as their client’s judgement of the utility of this applied work to the client’s situation, while academics are required to defend the merits of their work in relation to their theoretical contribution.

In connection, the final difference between applied and academic sociologists is that the former judges the success of their work on their client’s adoption of their proposed solutions , and their ability to influence their stakeholders’ decision-making , while the conclusions proposed by academics do not always lend themselves to specific actions (1984: 573).

Freeman and Rossi’s distinctions between the work of academic and applied sociologists are, in reality, not so absolute, but these points do identify some of the broad facets of applied sociology.

In summary, applied sociologists work for specific stakeholders, their research topics and time is often constrained by their sponsors’ needs and wishes, their work is less concerned with making a contribution to academic scholarship, and they are more interested in practical payoffs that will have a direct influence on their clients.

Clinical Sociology

There are various other sociological practices that fall under the ‘applied’ rubric. For example, clinical sociology is a term that has been used since the 1930s to describe ‘sociologically based interventions’, usually in reference to sociological work done across the health sector, in social work, and even in forensic settings (Bruhn and Rebach 1996: 3). This work includes collaborating with medical practitioners, nurses, psychologists, psychiatrists and nutritionists, as well as advocacy and support in mental health programs, including through counselling, interpersonal therapy, intervention programs with youth, substance abuse services, and group grief counselling.

Social Engineering

The term social engineering describes the applied research activities that are used in social planning, and it is also used to critique the value judgements made about what constitutes ‘pure’ and ‘applied’ research (Gouldner 1965; Israel 1966). Jonathan Turner (1998) runs with the idea of ‘sociological engineering’ to describe the type of sociology ‘that tries to deal with the real world’ (1998: 246). He argues that applied sociological knowledge lends itself to a systems engineering approach. He sees that applied sociology should be used to break abstract theoretical principles into ‘rules of thumb’ about social structures, in order to identify how societies are built, how to evaluate the problems of a given social structure, and how to break down the structures that are not working well (1998: 248).

Whatever we choose to call it, applied sociologists’ use of methods and theories has one central goal: to change some specific facet of social life.

Public Sociology

One thing that practitioners seem to agree on is that their work needs to be carried out in a way that is both accessible to their clients and devoid of academic jargon. In this connection, applied sociology has some synergy with public sociology , the branch of sociology that aims to engage ‘lay’ audiences, including neighborhood groups and grassroots organisations, with the aim of stimulating informed public dialogue (Burawoy 2004: 5-6).

Rita Simon (1987) argues that communication skills are quintessential in an applied context; sociologists who work in non-academic sectors should therefore be able to express themselves in plain language and not in ‘sociologese’ (using phrases that only people with a sociology degree might understand). She writes,

‘Basically, I think graduate students have to be taught that scientific writing is not a thing apart from ordinary prose; the aim is still to communicate efficiently, effectively, and if possible, aesthetically’ (1987: 34).

The next section takes up this issue of graduate careers in applied sociology.

Jobs in applied sociology

Employers place a strong value in sociological training, including our methodological excellence in conducting research and analysis, our ability to evaluate a wide variety of resources, and our effective communication skills, both written and oral (Germov and Poole 2006: 12). Moreover, sociologists are trained to appreciate different world-views, and so our interpersonal skills also give us an advantage in the job marketplace (cf. Sabin 1987: 396).

Most job advertisements (at least in Australia) will indicate two requirements that are nowadays almost universal in professional sectors: reflexive social skills and the ability for workers to adhere to equity and diversity laws. Sociology graduates are well placed to get along with their co-workers, to respect diversity in the workplace, and to foster good client relationships with various different public groups due to our discipline’s comparative focus on other cultures, and our critical appreciation of social context (both in terms of history and place).

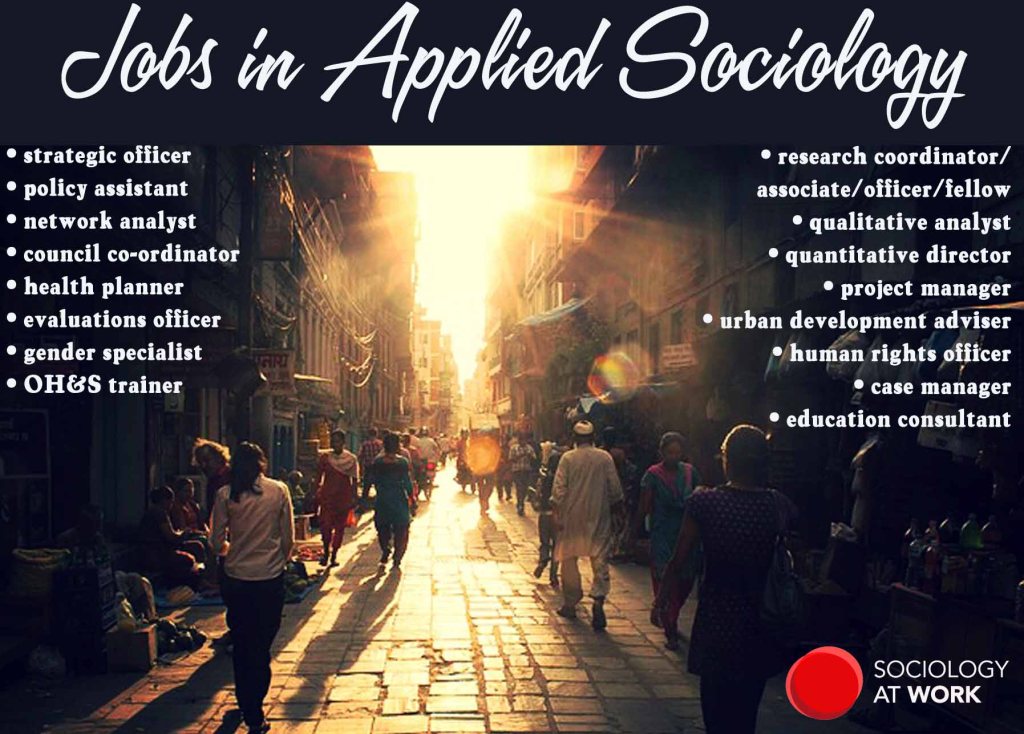

Despite their marketable qualities, sociology graduates do not always understand the types of career pathways available to them outside of academia. Few jobs that sociologists do are labelled under the category of ‘sociologist’. Nevertheless, the reality is that sociologists’ general skills are useful in a wide range of professional contexts.

For example, Edward Sabin (1987) writes that in Washington, USA, of the 1.6 million non-academic jobs that were listed in 1980, only 560 were identified as ‘sociologists’. The rest of the people in this sample were employed predominantly as professional and technical workers (113,640 people), systems analysts (19,850), and as writers and/or editors (8,690). A smaller proportion of workers were employed as public relations specialists (3,750), statisticians (2,870), statistical clerks (1,040), and urban and regional planners (760) (1987: 396). Sabin argues that the position of systems analyst holds great potential for applied sociologists, as it involves data processing, as well as an understanding of how organisations and businesses work. He writes,

‘Sociologists have a head start in understanding how people, procedures, and automated systems fit together, which is the focus of the systems analyst’ (1987: 397).

As far as the professional and technical workers category is concerned, Sabin sees that the general skills of a sociologist, rather than their specialist knowledge in one niche area (such as the topic of their thesis), is more likely to open up employment opportunities.

So, while employers may not advertise for ‘sociologists’, they might instead ask for the various roles identified above, as well as some of the positions listed below (although this is by no means an exhaustive list): • research coordinator, • research associate/officer/fellow, • qualitative analyst, • project manager, • strategic analyst, • public policy assistant, • policy analyst, • urban development adviser, • human rights officer, • case manager, • impact planning or evaluations officer, • education consultant, • gender specialist.

Sociology graduates therefore need to have a broader understanding of the different types of career paths that are out there waiting for them, and they need to better recognise that sociologists can be employed in the most (seemingly) unlikely places. For further discussion of applied sociology in the Australian context, and some examples of these practitioners’ work, see our online journal, Working Notes.

Applied sociological work can fit in well within any professional context; wherever people work, sociologists can help them grow by better understanding their business, their workers, their work practices, or whatever issues are of interest to their organisation. Rather than having a narrow focus on the types of companies and groups that might hire sociologists, sociology students and the wider public need to better recognise that sociologists are employed across a multitude of business, government and private industries. The quality of their work is exemplary, and, moreover, it can make a substantial contribution to the way the world works.

Further Resources

Visit our Working Notes section to read articles about applied sociology written by applied sociologists, or watch our videos with applied researchers and activists. See our other resources .

1. At the time of writing, Zuleyka was employed as a Social Scientist in the Australian public service, and she was an Adjunct Research Fellow with the Swinburne Institute of Social Research, Australia. She remains in her Adjunct position but now works as an applied sociologist elsewhere . This article was last updated 5th June 2014: added sub-headings and images. Paragraphs broken up into smaller chunks. Added Further Resources section. No text in the body of the article has been otherwise altered.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Lucy Nelms for commenting on an earlier draft of this article.

Abercrombie, N., S. Hill and B. S. Turner (2000) The Penguin Dictionary Of Sociology , 4th ed. London: Penguin Books.

Berger, P. (1963) Invitation To Sociology: A Humanistic Perspective . New York: Anchor Books.

Bruhn, J. G. (1999) ‘Introductory Statement: Philosophy and Future Direction’, Sociological Practice 1(1): 1-2.

Bruhn, J. G. and H. M. Rebach (1996) Clinical Sociology: An Agenda For Action . New York: Plenum Press.

Burawoy, M. (2004) ‘Public Sociologies: Contradictions, Dilemmas, And Possibilities’, Social Forces 82(4): 1-16.

DeMartini, J. R. (1979) ‘Applied Sociology: An Attempt At Clarification And Assessment’, Teaching Sociology 6(4): 331-354.

DeMartini, J. R. (1982) ‘Basic And Applied Sociological Work: Divergence, Convergence, Or Peaceful Co-existence?’, The Journal Of Applied Behavioural Science 18(2): 203-215.

Freeman, H. E. and P. H. Rossi (1984) ‘Furthering The Applied Side Of Sociology’, American Sociological Review 49(4): 571-580.

Germov, J. and M. Poole (2006) ‘The Sociological Gaze: Linking Private Lives To Public Issues’ pp. 3-20 in J. Germov and M. Poole (Eds) Public Sociology: An Introduction To Australian Society . Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin.

Gouldner, A. W. (1965) ‘Explorations In Applied Social Science’, pp. 5-22 in A. W. Gouldner (Ed) Applied Sociology: Opportunities And Problems . New York: Free Press.

Israel, J. (1966) ‘Remarks On The Sociology Of Social Scientists’, Acta Sociologica 9(3-4): 193-200.

Mills, C. W. (1959) The Sociological Imagination . New York: Oxford University Press.

Perlstadt, H. (2007) ‘Applied Sociology’, pp. 342-352 in C. D. Bryant and D. L. Peck (Eds) 21st Century Sociology: A Reference Handbook . Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Rossi, P. H. (1980) ‘Presidential Address: The Challenge And Opportunities Of Applied Social Research’, American Sociological Review 45(6): 889-904.

Sabin, E. (1987) ‘Hidden Jobs: Good News For Sociologists’, The American Sociologist 18(4): 394-399.

Simon, R. J. (1987) ‘Graduate Education In Sociology: What Do We Need To Do Differently?’, The American Sociologist 18(1): 32-36.

Steele, S. F. and J. Price (2007) Applied Sociology: Terms, Topics, Tools And Tasks, 2nd ed . Belmont: Thomson Wadsworth Publishing.

Turner, J. H. (1998) ‘Must Sociological Theory And Sociological Practice Be So Far Apart?: A Polemical Answer’, Sociological Perspectives 41(2): 243-258.

Zetterberg, H. L. (1964) ‘The Practical Use Of Sociological Knoweldge’, Acta Sociologica 7(2): 57-72.

Image Credits

1) Banksy .

3) Jusben Morgue File .

4) Banksy .

5) Mu-Am-Spring2008 (2008) Faces of Athens- Sociology Project . Flickr.

6) Michele0188 (2011) Hopeful the Egyptian Government will listen . Flickr.

7) Antsnax (2009) SCARE TSBVI Volunteers . Flickr.

8) Banksy .

Share this:

7 comments on “ what is applied sociology ”.

Pingback: Sociology for Clients | Sociology at Work

Pingback: Applied Sociology Roles, Skills and Methods – New S@W Series | Sociology at Work

Pingback: Erotic Capital & Beauty: How Sociology Can Help Explain Desire & Sex Appeal | The Other Sociologist - Analysis of Difference... By Dr Zuleyka Zevallos

Pingback: A Note on Academic (Ir)relevance | Political Violence @ a Glance

Pingback: Sociology for What, Who, Where and How? Situating Applied Sociology in Action | The Other Sociologist - Analysis of Difference... By Dr Zuleyka Zevallos

Pingback: Where to Look For Contract Research Work | Sociology at Work

Pingback: Career Planning in the Research Sector – The Other Sociologist

Get our blog posts via email

Enter your email address to receive notifications of new posts by email.

Email Address:

S@W is a registered not-for-profit network run by Dr Zuleyka Zevallos .

Learn more about SAW’s aims on our About page .

ABN: 22700939849

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Journal of Applied Social Science

Preview this book.

- Description

- Aims and Scope

- Editorial Board

- Submission Guidelines

The Journal of Applied Social Science publishes research articles, essays, research reports, teaching notes, and book reviews on a wide range of topics of interest to the social science practitioner. Specifically, we encourage submission of manuscripts that, in a concrete way, apply social science or critically reflect on the application of social science. Authors must address how they either improved a social condition or propose to do so, based on social science research .

We offer the following categories and formats as guides:

Application-Oriented Research This article details the development, implementation, and evaluation of a social science application. The goal: Provide readers with concrete examples of, and practical information on, applications to inform future implementations and applications.

Reflection on Process This article provides first-person reflection and/or critique on how we apply social science knowledge. The format is more creative. The goal: Spark discussion and debate, inspire future work in our discipline.

Engaged Scholarship This article provides social scientific insights, interpretations of findings, concepts, etc., that can improve understanding of social processes and increase the likelihood of the reader being able to improve communications, professional outcomes, and interactions. The goal: Translate social science knowledge into action steps.

Application of Theory and Method This article discusses how to effect social change by 1) applying a social science concept/theory/method; 2) assisting organizations; 3) empowering research or consulting; or 4) working on other relevant activities. It includes a definition, an example, and then discussion of how it could be (or has been) applied in a social setting. The goal: Generate new applications of social science tools more broadly.

Teaching Practice This article describes best practices in informing audiences about applied social science. The goal: Improve teaching of applied social science.

All new manuscripts to JASS must be submitted using the Sage Track manuscript submission website. Books for review and manuscripts of reviews should be sent to: Miriam Boeri, [email protected] , Sociology Department, Morison 193, 175 Forest Street, Bentley University Waltham MA 02452. Please read below for instructions on submitting manuscripts to JASS . Book review guidelines are also described below.

Log onto the Sage Track manuscript submission website at http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/jass and click on “Create Account: New users click here.”

Follow the instructions and make sure to enter your current and correct email address. Once you have finished creating a user account, your User ID and Password will be sent via email.

Submission of a New Manuscript

Log onto the manuscript central website and select “Author Center.” Once at the Author Center, select the link “Click here to Submit a New Manuscript.” Follow the instructions on each page. Once finished with a page, click on the “Save and Continue” option at the end of each page. Continue to follow the instructions for loading a new manuscript and/or other files at the appropriate stages (e.g., abstract, title page, etc.). When loading the manuscript file, make sure to use the “Browse” function and locate the correct file on your computer drive. Make sure to “Upload Files” when you are finished selecting the manuscript file you wish to upload. NOTE: All text files must be in word format and de-identified (please also remove any identifying information from the manuscript’s properties before you upload the manuscript). The system will convert the submission to a PDF file.

After uploading your manuscript, review your submission in one of the provided formats (e.g., PDF). Once you have reviewed your submission, click on the “Submit” button. You should receive a submission confirmation screen and an email confirming submission. You can revisit the website at any time to review the status of your submission.

Submission of a Revised Manuscript

To submit a revised manuscript to JASS , log onto the Sage Track manuscript submission website at http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/jass . Once at your Author Dashboard, view your “Manuscripts with Decisions” and select the option to “Create a Revision.” Continue to follow the directions to upload your revised manuscript. Make sure to upload a de-identified version of your revision as with the initial submission. Also provide comments regarding changes that were made to your revised manuscript. These comments will be provided to reviewers.

Submission of a manuscript implies commitment to publish in the journal; simultaneous submissions are not acceptable.

All copy should be typed, double-spaced, and should follow the style of the American Sociological Association Style Guide ( 7th ed .). Notes and references should appear at the end of the manuscript. Each manuscript should include a brief abstract of 100-150 words describing the subject, general approach, intended purpose of the article, and findings; also include 4-5 keywords for indexing and online searching. Ordinarily, articles should be less than 35 pages in length. However, research notes should not exceed 15 pages. Please note that the number of tables and figures mentioned in the text should be submitted along with the manuscript. Tables should be in editable format.

Authors who want to refine the use of English in their manuscripts might consider utilizing the services of SPi, a non-affiliated company that offers Professional Editing Services to authors of journal articles in the areas of science, technology, medicine or the social sciences. SPi specializes in editing and correcting English-language manuscripts written by authors with a primary language other than English. Visit http://www.prof-editing.com for more information about SPi’s Professional Editing Services, pricing, and turn-around times, or to obtain a free quote or submit a manuscript for language polishing.

Please be aware that Sage has no affiliation with SPi and makes no endorsement of the company. An author’s use of SPi’s services in no way guarantees that his or her submission will ultimately be accepted. Any arrangement an author enters into will be exclusively between the author and SPi, and any costs incurred are the sole responsibility of the author.

Supplemental Materials

This journal is able to host additional materials online (e.g. datasets, podcasts, videos, images etc) alongside the full-text of the article. For more information, please refer to our guidelines on submitting supplementary files .

Journal of Applied Social Science may accept submissions of papers that have been posted on pre-print servers; please alert the Editorial Office when submitting and include the DOI for the preprint in the designated field in the manuscript submission system. Authors should not post an updated version of their paper on the preprint server while it is being peer reviewed for possible publication in the journal. If the article is accepted for publication, the author may re-use their work according to the journal's author archiving policy.

If your paper is accepted, you must include a link on your preprint to the final version of your paper.

Visit the Sage Journals and Preprints page for more details about preprints.

Book Review Guidelines

Length of review: 4-5 pages double spaced.

Publication information: Title, author, publisher, date and place of publication.

Reviewer’s position: Disclose any personal information the reader should know about you in connection with this review. Are an expert in this area? Are you a researcher reviewing the book of someone from a different discipline? Do you know the author personally? Why does this book interest you? Is there is any possible conflict of interest?

Content of review: Include as many of the following topics as you can that are appropriate for this type of book:

Author: Describe the author’s background and qualifications. If the author is an academic or researcher? What is his or her present position? Are there any biases the reader should be aware of such as athe author is defending one side of an academic debate? List major contributions of the author to the field.

Audience: For whom is this book intended?

Overview: What are the major themes and topics of the book? How does the author organize the presentation (i.e. chronologically, by topic, etc.)? Is the presentation clear? Comprehensive? Is the organization appropriate?

Content: Using specific examples, discuss how the content supports and/or addresses the author’s expressed purpose. Is there new information? Are there significant errors or omissions? If the book is a research work, is the methodology appropriate? How well do the findings support the author’s conclusions? Use specific examples to illustrate your remarks.

Quality of the presentation: Is the book well written? Is the style appropriate to the topic? How well does the author flesh out his or her basic topics and themes? Use specific examples to illustrate your points.

Contribution: Does the book add to our knowledge or understanding of its subject? If so, in what ways? How does the book contribute to applied or clinical sociology?

Books for review and manuscripts of reviews should be sent to: Miriam Boeri, [email protected] , Sociology Department, Morison 193, 175 Forest Street, Bentley University Waltham MA 02452

- Read Online

- Sample Issues

- Current Issue

- Email Alert

- Permissions

- Foreign rights

- Reprints and sponsorship

- Advertising

Individual Subscription, Print Only

Institutional Subscription, E-access

Institutional Subscription, Print Only

Institutional Subscription, Combined (Print & E-access)

Individual, Single Print Issue

Institutional, Single Print Issue

To order single issues of this journal, please contact SAGE Customer Services at 1-800-818-7243 / 1-805-583-9774 with details of the volume and issue you would like to purchase.

Sociology Research Areas

The department has a long-standing tradition of engaging and valuing theoretically driven empirical research. This approach to sociology uses sophisticated theoretical reasoning and rigorous methodological tools, many of which are developed by Cornell faculty, to answer fundamental questions about the social world, how it is organized and how it is changing.

In addition to the research areas below, the department also hosts several unique research hubs and institutes on campus. These include:

Center for the Study of Inequality

Center for the Study of Economy and Society

Social Dynamics Lab

Community and Urban Sociology

Community and urban sociology are foundational topics in sociology. The shift from rural to urban society is one of the largest and most profound shifts in the history of society.

Read more about Community and Urban Sociology

Computational Social Science

With the rapid increase in the availability and use of computers, and their capacity to process information rapidly, the value of knowledge associated with computational resources has increased substantially. T

Read more about Computational Social Science

Sociology overlaps with other social sciences (like anthropology) considerably. Students who take the culture of area will be expected to understand the relationships between social and other approaches (e.g., anthropological) to understanding culture.

Read more about Culture

Economy and Society

Economic sociology analyzes economic phenomena such as markets, corporations, property rights, and work using the tools of sociology.

Read more about Economy and Society

A student who specializes in the area of gender must demonstrate special knowledge of how biological sex and gender shape individuals’ identities, how they shape experiences in everyday social life, individuals’ experiences with major social institutions, and also, therefore, important life outcomes such as family, career, and health.

Read more about Gender

Inequality and Social Stratification

Sociologists of inequality study the distribution of income, wealth, education, health and longevity, autonomy, status, prestige, political power, or other desired social goods, often (though not exclusively) across groups defined by social classes and occupations, race, gender, immigrant status, age, or sexual orientation.

Read more about Inequality and Social Stratification

Methodology

Sociologists approach their objects of study in a number of ways.

Read more about Methodology

Organizations, Work and Occupations

Like families, organizations are important social institutions. This area is designed to increase students’ knowledge and mastery of a range of organizations, including business firms, non-profit organizations, and government bodies.

Read more about Organizations, Work and Occupations

Policy Analysis

Sociology is increasingly linked to issues of social policy. This includes public policy, health policy and related domains.

Read more about Policy Analysis

Political Sociology and Social Movements

This is a long-standing focus of the field of sociology at Cornell. The realm of political action is an important domain for understanding social structure at the national and local levels.

Read more about Political Sociology and Social Movements

Race, Ethnicity and Immigration

Students who specialize in this area focus on the role of the individual statuses of race/ethnicity and the experience of immigration (e.g., rates of in- vs out-migration)

Read more about Race, Ethnicity and Immigration

Science, Technology and Medicine

Like the sociology of health and illness, students to take this area are usually interested in concepts associated with health and medicine.

Read more about Science, Technology and Medicine

Social Demography

Demographers in the field of sociology carry out research on varied aspects of population composition, distribution, and change.

Read more about Social Demography

Social Networks

Social network analysis is a way of conceptualizing, describing, and modeling society as sets of people or groups linked to one another by specific relationships, whether these relationships are as tangible as exchange networks or as intangible as perceptions of each other.

Read more about Social Networks

Social Psychology

Social psychologists study how behaviors and beliefs are shaped by the social context in which people are embedded.

Read more about Social Psychology

Sociology of Education

The sociology of education is an important topic for understanding individuals’ outcomes with respect to things like occupation and labor market status

Read more about Sociology of Education

Sociology of Family

Family research in the field of sociology addresses patterns of change and variation in family behaviors and household relationships by social class, race/ethnicity, and gender.

Read more about Sociology of Family

Sociology of Health and Illness

There is increasing recognition (including within the field of medicine) that health and illness are a function of social factors (e.g., inequality).

Read more about Sociology of Health and Illness

Top 50 Sociology Research Topics Ideas and Questions

Interesting Sociology Research Topics and Questions: Due to the vastness of the possibilities, coming up with sociological research topics can be stressful. In order to help narrow down the specificities of where our interests lie, it is important to organize them into various subtopics. This article will be focusing on various sociology research topics, ideas, and questions, one can venture into, to write an effective sociology research paper .

- Social Institutions

Interactions with social institutions are inextricably linked to our lives. Social institutions such as family, marriage, religion, education, etc., play a major role in defining the type of primary and secondary identities we create for ourselves. They also define the types and natures of our various relationships with fellow individuals and social systems around us and play a huge role in the type of socialization we are exposed to in various stages of our lives. Some topics that one can consider to examine the roles that social institutions play in different dimensions of our lives are as follows:

- Hierarchical creation of Distinction and Differentiation in cultures rich in Plurality

- Violence perpetuated in the structures of Family, Marriage and Kinship

- Sexually Abused Boys – The contribution of familial and societal neglect due to unhealthy stereotypes resulting in silenced voices of male victims

- The Institution of Dowry – Turning Marriage into an Unethical Transaction Process

- Gendered Socialization of young children in Indian households and how it feeds into the Patriarchy

- Marital Rape – An Examination on the Importance of Consent

- How do the institutions of Family, Marriage and Kinship contribute towards the Socialization of young minds?

- In the Pretext of upholding the Integrity of the Family – The Horrifying Prevalence of Honor Killing

- The Underlying Influence of Religion and Family in the cultivation of Homophobic sentiments – A Case Study

- The Roles of Family, Education and Society in both enforcing as well as eradicating negative sentiments towards Inter-caste Marriages.

- The effects of Divorce on young minds and their interactions with their social environments and the relationships they create. Are there primarily negative effects as society dictates, or could divorce also have possible effects for children in mentally/ physically abusive parents?

- Examining the Influence of class status on Parenting styles

- Social Issues

Our society is never rid of the conflict. It lies in our very human nature to create conflict-ridden- situations and seek multiple ways to resolve them. Conflict is ingrained in human society, and the more diverse it is, in terms of social institutions, nationalities, gender identities, sexualities, races, etc., the more prone to conflict we are. It is not always necessarily a bad thing, but a clear sociological examination of these social issues that stem from our various interactions is of utmost importance, in order to come up with optimal and rational solutions. Some social issues that one can focus on for delving into research are as follows:

- Reconceptualizing the underlying differences between Race and Ethnicity with the help of examples and examining the interchangeable usage of the two terms

- Assess from a Sociological perspective the rise in Xenophobia after the rise of Covid-19

- Examining the prevalence of gender-inequality in the workspace and solutions that can help overcome it

- Sociological Perspective on Ethnic Cleansing and possible solutions

- 10 Things that Need to Change in the Society in order to be more accommodative of Marginalized Communities and help tackle their Challenges

- The Directly Proportional Relationship between Privilege and Power – A Sociological Examination

- Demonization of the Occident by the Orient – A Case Study

- Dimensions of Intersectionality – An Examination through Feminist Theory

- Examining the Manner in which the Modern Education System feeds into Harmful Capitalistic Ideals with examples

- The perpetuation of differential treatment of male and female students within Indian Educational Systems

- Scarcity of Resources or rather the Accumulation of the World’s Resources in the Hands of a Few? – A Sociological Examination

- Links between Colonialism and Christianity and their effects on the Colonized

- Creation and conflict of Plural Identities in the Children of Migrants

- The Overarching need for Social Reform to precede and hence ensure Economic Reform

- Marxist Perspectives

Karl Marx was a renowned German Sociologist from whom comes the Marxist Theories. Through works such as “The Communist Manifesto” (1848) and other renowned works, his views on capitalist society, the unequal division of labor, class conflict, and other issues spread throughout the world, influencing many. His influential works significantly widened the Marxist perspective. He sought to explain and analyze the various inequalities and differences that were imposed on society and led to class conflict; for which the economic system of capitalism was blamed. His views on other topics like religion, education, interdisciplinarity, climate change, etc. were also highly praised. Here are some of the topics one can venture into for researching Marx’s perspectives.

- Marxist perspective on the Effect of Capitalism on the Climate Crisis

- Marxist perspective on the Importance of the element of Interdisciplinarity within Indian Sociology as an Academic Discipline

- Marxist Criticism of Normative Ethical Thought

Read: How to Apply Sociology in Everyday Life

The majority of the world’s population is exposed to various forms of media in today’s world such as, Films, Newspapers, TV Shows, Books, Online Sources, Social-Media etc. The consumption of such content has increased to such an extent that it now plays a huge role in the way individual identities are shaped and influenced. They also play a huge role in influencing the opinions and views we hold about the world’s issues and various phenomena, and now hold the power to become driving forces of social change in society. These are some areas that have the potential for in-depth sociological research:

- A Sociological Analysis of the Influence of Pop Culture in an Individual’s socialization process and building body image

- Influence of social media in the ongoing perpetuation of Western standards of Beauty

- A Sociological Analysis of Representations of Masculinity in Audio/Visual/Print Advertisements and the effects the pose for audiences who are offered this content

- A Sociological Analysis on the Fetishization of Queer Relationships as Token Diversity in Film

- A Sociological Perspective on the Perpetuation of Casteism in the Bollywood Industry by means of Endorsements for Colorist advertisements, as well as portrayal of Negative Stereotypes of Marginalized Communities on the big screen

- Popular Cinema – Possessing Potential to both Reinforce or Challenge Hegemonic Masculinity

- A Detailed Sociological Analyses of Cultural Appropriation in Media and how it perpetuates unhealthy Fetishization of certain cultures

- Trace Representations of Hegemonic Masculinity in Popular Media – Assessing spectator relationship

READ: How to Write Academic Paper: Introduction to Academic Writing

- Political Issues

Just as social issues, political issues are equally important. The various political systems of the world determine the kind of governance we are under and the nature of human rights we are ensured as citizens. A sociological assessment of the various relationships between the different political issues instigated by the numerous forms of political power is of utmost importance. Such sociological indulgence helps in assessing the nature of these issues and the effect these issues have on citizens. Colonialism, Caste system, Resource conflicts, Communism, etc. and their roles in the political arena, as well as the nature of the world governments of today, can be assessed using research questions/ topics such as these:

- Sociological Inspection on the International Peacekeeping Efforts in local conflicts

- Tracing the Role of Colonialism in the act of instigating Contemporary and Historical conflicts in post-colonial states – A Case Study

- Illustrating with examples the Vitality of Symbolic Representation of Indian Nationalism and how it contributes to Nationalistic Sentiments

- Comparative Analysis on the two cases of Palestine/Israel conflict and Kashmir/India conflict within the dimensions of State Violence, Separatism and Militancy

- Case Study outlining the influence of socio-economic and political factors that result in the creation and perpetuation of Conflict over Resources.

- Trace the Relationship between Naxalism and Intrastate Conflict

- Analyzing the existence of Caste based Violence in India

- Examination of the extent to which Freedom of Speech and Expression is allowed to be practiced and controlled under the Indian Government today

- Sociological Analysis on the Occupation of Kashmir within Dimensions of Militancy and Human Rights

- Sociological Analysis on the Occupation of Palestine

- Annihilation of Caste: A Review – Stirring the Waters Towards a Notional Reform to Attain Fundamental Social Reforms

- The demonization of Communism – A Sociological Perspective

- Role of Social Movements – A Sociological Case Study

We will update with more sociology research topics like Urban Sociology, industries, crime, mental health, Etc.

Also READ: How to write a Sociology Assignment – Guide

Angela Roy is currently pursuing her majors in Sociology and minors in International Relations and History, as a part of her BA Liberal Arts Honors degree in SSLA, Pune. She has always been driven to play a part in changing and correcting the social evils that exist in society. With a driving passion for breaking down harmful societal norms and social injustices, she seeks to learn and understand the different social institutions that exist in society like family, marriage, religion and kinship, and how they influence the workings and functioning of various concepts like gender, sexuality and various types of socializations in an individual’s life. She envisions herself to play a vital role in building safe places for today’s marginalized communities and creating a world that is characterized by equity and inclusiveness, free of discrimination and exploitative behaviors.

2.1 Approaches to Sociological Research

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you should be able to:

- Define and describe the scientific method.

- Explain how the scientific method is used in sociological research.

- Describe the function and importance of an interpretive framework.

- Describe the differences in accuracy, reliability and validity in a research study.

When sociologists apply the sociological perspective and begin to ask questions, no topic is off limits. Every aspect of human behavior is a source of possible investigation. Sociologists question the world that humans have created and live in. They notice patterns of behavior as people move through that world. Using sociological methods and systematic research within the framework of the scientific method and a scholarly interpretive perspective, sociologists have discovered social patterns in the workplace that have transformed industries, in families that have enlightened family members, and in education that have aided structural changes in classrooms.

Sociologists often begin the research process by asking a question about how or why things happen in this world. It might be a unique question about a new trend or an old question about a common aspect of life. Once the question is formed, the sociologist proceeds through an in-depth process to answer it. In deciding how to design that process, the researcher may adopt a scientific approach or an interpretive framework. The following sections describe these approaches to knowledge.

The Scientific Method

Sociologists make use of tried and true methods of research, such as experiments, surveys, and field research. But humans and their social interactions are so diverse that these interactions can seem impossible to chart or explain. It might seem that science is about discoveries and chemical reactions or about proving ideas right or wrong rather than about exploring the nuances of human behavior.

However, this is exactly why scientific models work for studying human behavior. A scientific process of research establishes parameters that help make sure results are objective and accurate. Scientific methods provide limitations and boundaries that focus a study and organize its results.

The scientific method involves developing and testing theories about the social world based on empirical evidence. It is defined by its commitment to systematic observation of the empirical world and strives to be objective, critical, skeptical, and logical. It involves a series of six prescribed steps that have been established over centuries of scientific scholarship.

Sociological research does not reduce knowledge to right or wrong facts. Results of studies tend to provide people with insights they did not have before—explanations of human behaviors and social practices and access to knowledge of other cultures, rituals and beliefs, or trends and attitudes.

In general, sociologists tackle questions about the role of social characteristics in outcomes or results. For example, how do different communities fare in terms of psychological well-being, community cohesiveness, range of vocation, wealth, crime rates, and so on? Are communities functioning smoothly? Sociologists often look between the cracks to discover obstacles to meeting basic human needs. They might also study environmental influences and patterns of behavior that lead to crime, substance abuse, divorce, poverty, unplanned pregnancies, or illness. And, because sociological studies are not all focused on negative behaviors or challenging situations, social researchers might study vacation trends, healthy eating habits, neighborhood organizations, higher education patterns, games, parks, and exercise habits.

Sociologists can use the scientific method not only to collect but also to interpret and analyze data. They deliberately apply scientific logic and objectivity. They are interested in—but not attached to—the results. They work outside of their own political or social agendas. This does not mean researchers do not have their own personalities, complete with preferences and opinions. But sociologists deliberately use the scientific method to maintain as much objectivity, focus, and consistency as possible in collecting and analyzing data in research studies.

With its systematic approach, the scientific method has proven useful in shaping sociological studies. The scientific method provides a systematic, organized series of steps that help ensure objectivity and consistency in exploring a social problem. They provide the means for accuracy, reliability, and validity. In the end, the scientific method provides a shared basis for discussion and analysis (Merton 1963). Typically, the scientific method has 6 steps which are described below.

Step 1: Ask a Question or Find a Research Topic

The first step of the scientific method is to ask a question, select a problem, and identify the specific area of interest. The topic should be narrow enough to study within a geographic location and time frame. “Are societies capable of sustained happiness?” would be too vague. The question should also be broad enough to have universal merit. “What do personal hygiene habits reveal about the values of students at XYZ High School?” would be too narrow. Sociologists strive to frame questions that examine well-defined patterns and relationships.

In a hygiene study, for instance, hygiene could be defined as “personal habits to maintain physical appearance (as opposed to health),” and a researcher might ask, “How do differing personal hygiene habits reflect the cultural value placed on appearance?”

Step 2: Review the Literature/Research Existing Sources

The next step researchers undertake is to conduct background research through a literature review , which is a review of any existing similar or related studies. A visit to the library, a thorough online search, and a survey of academic journals will uncover existing research about the topic of study. This step helps researchers gain a broad understanding of work previously conducted, identify gaps in understanding of the topic, and position their own research to build on prior knowledge. Researchers—including student researchers—are responsible for correctly citing existing sources they use in a study or that inform their work. While it is fine to borrow previously published material (as long as it enhances a unique viewpoint), it must be referenced properly and never plagiarized.

To study crime, a researcher might also sort through existing data from the court system, police database, prison information, interviews with criminals, guards, wardens, etc. It’s important to examine this information in addition to existing research to determine how these resources might be used to fill holes in existing knowledge. Reviewing existing sources educates researchers and helps refine and improve a research study design.

Step 3: Formulate a Hypothesis

A hypothesis is an explanation for a phenomenon based on a conjecture about the relationship between the phenomenon and one or more causal factors. In sociology, the hypothesis will often predict how one form of human behavior influences another. For example, a hypothesis might be in the form of an “if, then statement.” Let’s relate this to our topic of crime: If unemployment increases, then the crime rate will increase.

In scientific research, we formulate hypotheses to include an independent variables (IV) , which are the cause of the change, and a dependent variable (DV) , which is the effect , or thing that is changed. In the example above, unemployment is the independent variable and the crime rate is the dependent variable.

In a sociological study, the researcher would establish one form of human behavior as the independent variable and observe the influence it has on a dependent variable. How does gender (the independent variable) affect rate of income (the dependent variable)? How does one’s religion (the independent variable) affect family size (the dependent variable)? How is social class (the dependent variable) affected by level of education (the independent variable)?