Action Research: Steps, Benefits, and Tips

Introduction

History of action research, what is the definition of action research, types of action research, conducting action research.

Action research stands as a unique approach in the realm of qualitative inquiry in social science research. Rooted in real-world problems, it seeks not just to understand but also to act, bringing about positive change in specific contexts. Often distinguished by its collaborative nature, the action research process goes beyond traditional research paradigms by emphasizing the involvement of those being studied in resolving social conflicts and effecting positive change.

The value of action research lies not just in its outcomes, but also in the process itself, where stakeholders become active participants rather than mere subjects. In this article, we'll examine action research in depth, shedding light on its history, principles, and types of action research.

Tracing its roots back to the mid-20th century, Kurt Lewin developed classical action research as a response to traditional research methods in the social sciences that often sidelined the very communities they studied. Proponents of action research championed the idea that research should not just be an observational exercise but an actionable one that involves devising practical solutions. Advocates believed in the idea of research leading to immediate social action, emphasizing the importance of involving the community in the process.

Applications for action research

Over the years, action research has evolved and diversified. From its early applications in social psychology and organizational development, it has branched out into various fields such as education, healthcare, and community development, informing questions around improving schools, minority problems, and more. This growth wasn't just in application, but also in its methodologies.

How is action research different?

Like all research methodologies, effective action research generates knowledge. However, action research stands apart in its commitment to instigate tangible change. Traditional research often places emphasis on passive observation , employing data collection methods primarily to contribute to broader theoretical frameworks . In contrast, action research is inherently proactive, intertwining the acts of observing and acting.

The primary goal isn't just to understand a problem but to solve or alleviate it. Action researchers partner closely with communities, ensuring that the research process directly benefits those involved. This collaboration often leads to immediate interventions, tweaks, or solutions applied in real-time, marking a departure from other forms of research that might wait until the end of a study to make recommendations.

This proactive, change-driven nature makes action research particularly impactful in settings where immediate change is not just beneficial but essential.

Action research is best understood as a systematic approach to cooperative inquiry. Unlike traditional research methodologies that might primarily focus on generating knowledge, action research emphasizes producing actionable solutions for pressing real-world challenges.

This form of research undertakes a cyclic and reflective journey, typically cycling through stages of planning , acting, observing, and reflecting. A defining characteristic of action research is the collaborative spirit it embodies, often dissolving the rigid distinction between the researcher and the researched, leading to mutual learning and shared outcomes.

Advantages of action research

One of the foremost benefits of action research is the immediacy of its application. Since the research is embedded within real-world issues, any findings or solutions derived can often be integrated straightaway, catalyzing prompt improvements within the concerned community or organization. This immediacy is coupled with the empowering nature of the methodology. Participants aren't mere subjects; they actively shape the research process, giving them a tangible sense of ownership over both the research journey and its eventual outcomes.

Moreover, the inherent adaptability of action research allows researchers to tweak their approaches responsively based on live feedback. This ensures the research remains rooted in the evolving context, capturing the nuances of the situation and making any necessary adjustments. Lastly, this form of research tends to offer a comprehensive understanding of the issue at hand, harmonizing socially constructed theoretical knowledge with hands-on insights, leading to a richer, more textured understanding.

Disadvantages of action research

Like any methodology, action research isn't devoid of challenges. Its iterative nature, while beneficial, can extend timelines. Researchers might find themselves engaged in multiple cycles of observation, reflection, and action before arriving at a satisfactory conclusion. The intimate involvement of the researcher with the research participants, although crucial for collaboration, opens doors to potential conflicts. Through collaborative problem solving, disagreements can lead to richer and more nuanced solutions, but it can take considerable time and effort.

Another limitation stems from its focus on a specific context: results derived from a particular action research project might not always resonate or be applicable in a different context or with a different group. Lastly, the depth of collaboration this methodology demands means all stakeholders need to be deeply invested, and such a level of commitment might not always be feasible.

Examples of action research

To illustrate, let's consider a few scenarios. Imagine a classroom where a teacher observes dwindling student participation. Instead of sticking to conventional methods, the teacher experiments with introducing group-based activities. As the outcomes unfold, the teacher continually refines the approach based on student feedback, eventually leading to a teaching strategy that rejuvenates student engagement.

In a healthcare context, hospital staff who recognize growing patient anxiety related to certain procedures might innovate by introducing a new patient-informing protocol. As they study the effects of this change, they could, through iterations, sculpt a procedure that diminishes patient anxiety.

Similarly, in the realm of community development, a community grappling with the absence of child-friendly public spaces might collaborate with local authorities to conceptualize a park. As they monitor its utilization and societal impact, continual feedback could refine the park's infrastructure and design.

Contemporary action research, while grounded in the core principles of collaboration, reflection, and change, has seen various adaptations tailored to the specific needs of different contexts and fields. These adaptations have led to the emergence of distinct types of action research, each with its unique emphasis and approach.

Collaborative action research

Collaborative action research emphasizes the joint efforts of professionals, often from the same field, working together to address common concerns or challenges. In this approach, there's a strong emphasis on shared responsibility, mutual respect, and co-learning. For example, a group of classroom teachers might collaboratively investigate methods to improve student literacy, pooling their expertise and resources to devise, implement, and refine strategies for improving teaching.

Participatory action research

Participatory action research (PAR) goes a step further in dissolving the barriers between the researcher and the researched. It actively involves community members or stakeholders not just as participants, but as equal partners in the entire research process. PAR is deeply democratic and seeks to empower participants, fostering a sense of agency and ownership. For instance, a participatory research project might involve local residents in studying and addressing community health concerns, ensuring that the research process and outcomes are both informed by and beneficial to the community itself.

Educational action research

Educational action research is tailored specifically to practical educational contexts. Here, educators take on the dual role of teacher and researcher, seeking to improve teaching practices, curricula, classroom dynamics, or educational evaluation. This type of research is cyclical, with educators implementing changes, observing outcomes, and reflecting on results to continually enhance the educational experience. An example might be a teacher studying the impact of technology integration in her classroom, adjusting strategies based on student feedback and learning outcomes.

Community-based action research

Another noteworthy type is community-based action research, which focuses primarily on community development and well-being. Rooted in the principles of social justice, this approach emphasizes the collective power of community members to identify, study, and address their challenges. It's particularly powerful in grassroots movements and local development projects where community insights and collaboration drive meaningful, sustainable change.

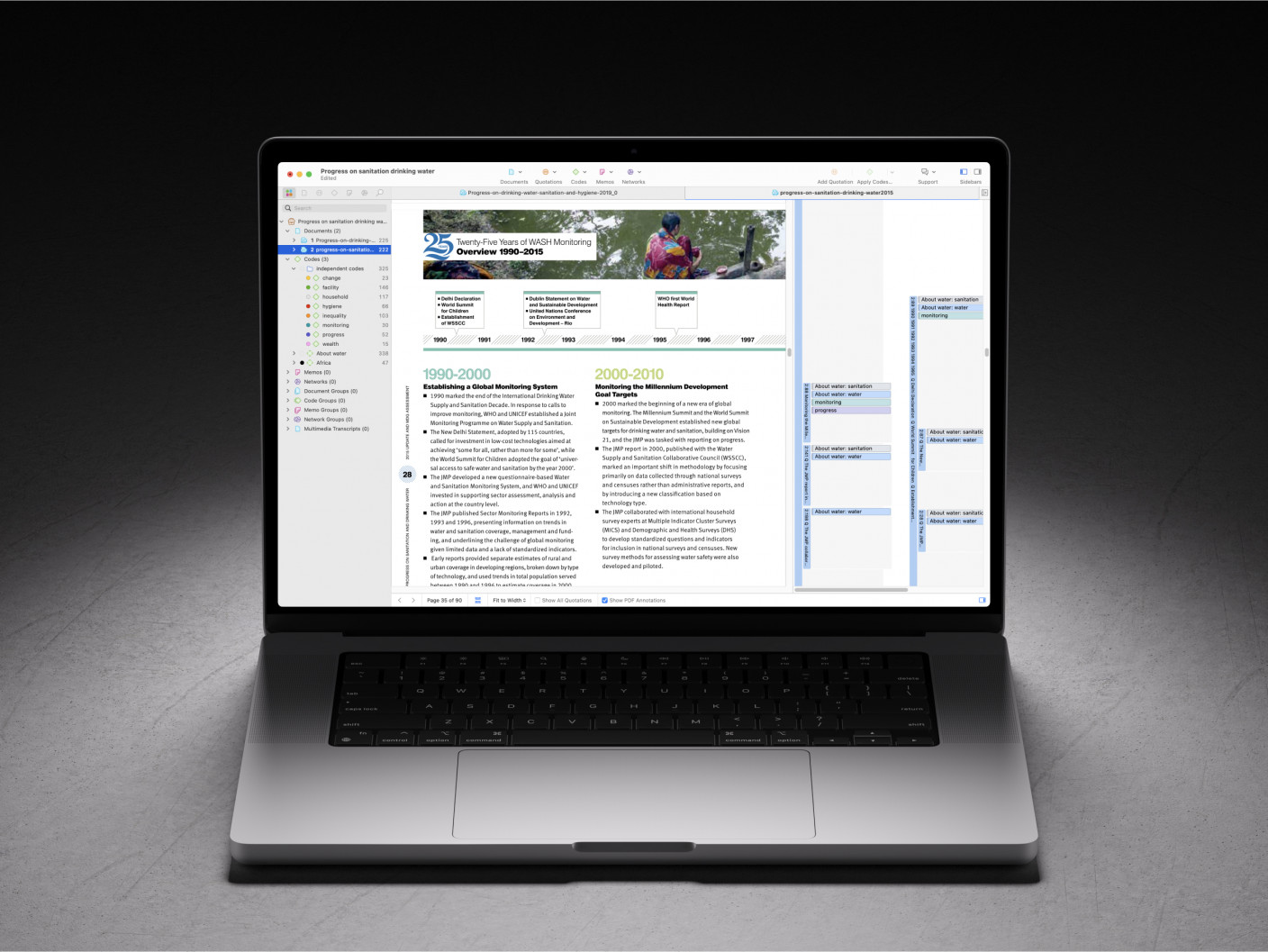

Key insights and critical reflection through research with ATLAS.ti

Organize all your data analysis and insights with our powerful interface. Download a free trial today.

Engaging in action research is both an enlightening and transformative journey, rooted in practicality yet deeply connected to theory. For those embarking on this path, understanding the essentials of an action research study and the significance of a research cycle is paramount.

Understanding the action research cycle

At the heart of action research is its cycle, a structured yet adaptable framework guiding the research. This cycle embodies the iterative nature of action research, emphasizing that learning and change evolve through repetition and reflection.

The typical stages include:

- Identifying a problem : This is the starting point where the action researcher pinpoints a pressing issue or challenge that demands attention.

- Planning : Here, the researcher devises an action research strategy aimed at addressing the identified problem. In action research, network resources, participant consultation, and the literature review are core components in planning.

- Action : The planned strategies are then implemented in this stage. This 'action' phase is where theoretical knowledge meets practical application.

- Observation : Post-implementation, the researcher observes the outcomes and effects of the action. This stage ensures that the research remains grounded in the real-world context.

- Critical reflection : This part of the cycle involves analyzing the observed results to draw conclusions about their effectiveness and identify areas for improvement.

- Revision : Based on the insights from reflection, the initial plan is revised, marking the beginning of another cycle.

Rigorous research and iteration

It's essential to understand that while action research is deeply practical, it doesn't sacrifice rigor . The cyclical process ensures that the research remains thorough and robust. Each iteration of the cycle in an action research project refines the approach, drawing it closer to an effective solution.

The role of the action researcher

The action researcher stands at the nexus of theory and practice. Not just an observer, the researcher actively engages with the study's participants, collaboratively navigating through the research cycle by conducting interviews, participant observations, and member checking . This close involvement ensures that the study remains relevant, timely, and responsive.

Drawing conclusions and informing theory

As the research progresses through multiple iterations of data collection and data analysis , drawing conclusions becomes an integral aspect. These conclusions, while immediately beneficial in addressing the practical issue at hand, also serve a broader purpose. They inform theory, enriching the academic discourse and providing valuable insights for future research.

Identifying actionable insights

Keep in mind that action research should facilitate implications for professional practice as well as space for systematic inquiry. As you draw conclusions about the knowledge generated from action research, consider how this knowledge can create new forms of solutions to the pressing concern you set out to address.

Collecting data and analyzing data starts with ATLAS.ti

Download a free trial of our intuitive software to make the most of your research.

Research Methods and Design

- Action Research

- Case Study Design

- Literature Review

- Quantitative Research Methods

- Qualitative Research Methods

- Mixed Methods Study

- Indigenous Research and Ethics This link opens in a new window

- Identifying Empirical Research Articles This link opens in a new window

- Research Ethics and Quality

- Data Literacy

- Get Help with Writing Assignments

Action research

A type of applied research designed to find the most effective way to bring about a desired social change or to solve a practical problem, usually in collaboration with those being researched.

SAGE Research Methods Videos

How do you define action research.

Professor David Coghlan explains action research as an approach that crosses many academic disciplines yet has a shared focus on taking action to address a problem. He describes the difference between this approach and empirical scientific approaches, particularly highlighting the challenge of getting action research to be taken seriously by academic journals

Dr. Nataliya Ivankova defines action research as using systematic research principles to address an issue in everyday life. She delineates the six steps of action research, and illustrates the concept using an anti-diabetes project in an urban area.

This is just one segment in a whole series about action research. You can find the rest of the series in our SAGE database, Research Methods:

Videos covering research methods and statistics

Further Reading

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Case Study Design >>

- Last Updated: May 7, 2024 9:51 AM

CityU Home - CityU Catalog

Theoretical and Methodological Validation of the Action Research: Methodology of the Scientific Study

- Open Access

- First Online: 11 September 2021

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Ona Monkevičienė 9 &

- Alvyra Galkienė 9

Part of the book series: Inclusive Learning and Educational Equity ((ILEE,volume 5))

2 Citations

This chapter presents the theoretical and methodological substantiation of the action research, which was used by collaborating research teams from Poland, Lithuania, Finland and Austria for the study “Improving Inclusive Education Through Universal Design for Learning”. The chapter discusses different sociocultural contexts in the participating countries and what led to the research question, which asks “How does the implementation of universal design for learning enrich the practice of inclusive education in different educational contexts”. This question was looked at in terms of its relevance to the four above-mentioned countries. It can be argued that the action research is favourable for the development of theory and that inclusive education can be changed and reflected by it. The types of action research chosen by the research teams are discussed, those being collaborative, and critical participatory. The cycles of action research and their goals are also presented. Seeking to substantiate the choices of research teams regarding the process and methods of action research, this chapter elaborates on the aspects of action research organisation that are interpreted differently by the researchers: Can the action research be conducted only by the researcher–teachers or can it be carried out by teachers in cooperation with researchers? Is it possible to use a combination of qualitative and quantitative research? The problem with quality and validity of action research is discussed.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Embedding Action Research in Philippine Teacher Education

Action Research Within the Tradition of Nordic Countries

Transforming educational practice through action research: three australian examples.

- Action research

- Transformation of education

- Methods of action research

3.1 Theoretical Perspective of the Research

The theoretical framework of the study is based on the theory of social constructivism, introduced by Vygotsky (Scheurman, 2018 ), and theories of educational neuroscience. Scheurman ( 2018 ) supports the idea of Piaget’s constructivism and explains Vygotsky’s theory on how social and cultural contexts influence the authentic construction of a child’s understanding. In terms of social constructivism theory, knowledge is co-constructed in the child’s interaction with others, as well as with his or her social and cultural environment. The teacher is seen as a collaborator and provides scaffolding (expert support) for learning. According to Wilson ( 1996 ), the sociocultural theory of Vygotsky ( 1978 ) highlights the significance of the child’s authentic learning experiences towards the construction of their own cognitive processes and strategies for world understanding. This is accomplished with the employment of the following cultural tools: scaffolding, dialogue, collaboration and language. The theories of educational neuroscience present a scientific understanding of brain–behaviour relationships, which allow for the development of new learning and teaching strategies (Jamaludin et al., 2019 ). The above-discussed theories substantiate the understanding of the approach investigated by the Universal Design for Learning and its improvement applied to inclusive education from multiple theoretical lenses (Hackman, 2008 , Meyer et al., 2014 ).

The Goal and Objectives of the Research

The purpose of the study is to better understand how the implementation of universal design for learning enriches the practices of inclusive education in different educational contexts.

The objectives of the research are to employ the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) methodology to:

Reveal the transformations of the educational process in an inclusive classroom

Identify the educational factors facilitating a student becoming an expert learner

Reveal the pedagogical competence of teachers for a diverse set of students

Re-interpret existing inclusive education practices in the classroom

The Context of the Research

The research was conducted implementing the project “Preconditions of Transformation of Education Process in Different Educational Contexts by Applying Inclusive Education Strategies” (Erasmus+, No. 2018-1-LT01-KA201-046957, 2018–2021). Researchers and school teachers from four countries and various educational settings, all of whom have been exploring research-based solutions for improving inclusive education, made up the international research team. Researchers from the University of Vienna, Austria, joined teachers from LWS Steinbrechergasse, a local school in Vienna; researchers from the University of Cracow, Poland, teamed up with local teachers from Zespol Szkol Ogolnoksztalcacych No. 9; researchers from Vytautas Magnus University, Lithuania, joined teachers from Vilniaus Balsiu mokykla, a school in Vilnius; finally, researchers from the University of Lapland, Finland, partnered with local teachers from Aleksanteri Kenan koulu.

The countries all experience different socio-educational contexts in the implementation of inclusive education. In Lithuania and Poland, inclusive education is still in a phase of active transformation. In Austrian primary schools, it has been actively implemented since 1993 and in secondary schools since 1996 (School Organization Act). However, challenges have been encountered in coping with immigration and socially disadvantaged situations (Galkienė, 2017 ). National projects have been implemented in Finland since 1997 and have contributed to a wide adoption of inclusive education’s main principles. Since 2014, special attention has mainly been paid to ensuring the child’s well-being (Galkienė, 2017 ). At present, the main focus in Finland is on developing the pedagogical competence of inclusive teachers.

In a joint discussion, the international research team identified problem areas in the quality of inclusive education in their countries and directions for its improvement: The concern in Poland centred around the replacement of routine lessons with methods applied by teachers, using the way schoolchildren learn to improve the quality of inclusive education; in Lithuania, it is about the promotion of schoolchildren’s self-regulated learning and developing their qualities and abilities in the context of having them be expert learners; Finland aims to develop teachers’ professional competencies, which enable them to teach a wide range of students; Austria seeks to re-interpret the existing practices of inclusive education by striving for a higher quality of this type of education. The researcher team also discussed the possibilities of applying UDL to help improve inclusive education in specific problem areas. It was decided that researchers and school teachers from all four countries would implement the UDL approach in schools, and assess its transformative impact in order to improve the quality of inclusive education in the identified problem areas.

3.2 Methodological Approach of the Participatory and Collaborative Action Research

Action research as transformational power.

The international research team chose action research after taking into consideration the aim and nature of the inquiry in question. This choice was made because such research is appropriate for planning, implementing, investigating and reflecting on the improvement of inclusive education quality . A theory is usually developed while action research is taking place. Simultaneously, a practical intervention is introduced to help understand and characterise processes and their results. It is believed that social systems and phenomena are easier to comprehend if attempts are made to change them. According to Cohen et al. ( 2013 ), action research is a powerful means for change and improvement. It possesses the potential power to initiate a change at school (Ferrance, 2000 ). According to Rowe et al. ( 2013 ), action research may initiate not only changes that are developmental or transactional but also ones that are transformational. Transformational changes are more radical compared to developmental or transactional ones because they embrace not only improvement of existing practices, structures and procedures but transformation of values, goals, roles, relations, learning and thinking of individuals, teams and organisations. The researchers state that action research is an efficient methodological approach for developing inclusive education (Charalampous & Papademetriou, 2019 ; Armstrong & Tsokova 2019 ).

Action Research Approaches

Since one can use it with various approaches, action research is convenient. Researchers frequently systemise action research according to type: individual teacher research, collaborative action research, school-wide research, etc. (Ferrance, 2000 ), classroom action research, as well as emancipatory, participatory and critical participatory action research (Kemmis et al., 2014 ). In all types of action research, participants raise questions and solve a real problem in a local environment, in a specific context and with the intention of sharing new knowledge with others. The implementers of the research perform the roles of practitioners and researchers. Thus, action research is conducted in the context of a participatory paradigm and, for this reason, it is referred to as participatory action research. Morales ( 2016 ) and Datta et al. ( 2015 ) identify other features of action research, such as collaboration among all the participants, co-learning, joint conducting of research and group reflections and creating new knowledge and meaning. Meanwhile, other researchers single out a separate type of action research, i.e. collaborative action research (Ferrance, 2000 ; Charalampous & Papademetriou, 2019 ).

Two types of action research—participatory and collaborative—are employed in the present research with an emphasis on the participatory approach, which prevails in participatory action research. However, the process of action research also possesses features of a collaborative approach. Nevertheless, the collaborative approach dominates in the process of collaborative action research but the action research naturally relies on the participatory paradigm.

Participatory Action Research

The Austrian team of researchers chose critical participatory action research. While carrying this out, attempts were made to connect all the social groups that were participating in the pedagogical practice and interact through it as a means of introducing changes in existing pedagogical practices at school (Kemmis et al., 2014 ). According to the above-mentioned authors, critical participatory action research aims to change three areas: the way in which practitioners practice (in this case, teachers and other participants in the educational process), their understanding of their own practices and conditions under which they practice (Kemmis et al., 2014 , p. 63). Participatory action research is typically coordinated by the participants themselves, its model being democratic and its success focused on personal and collective change (Morales, 2016 ; Jacobs, 2016 ).

Participatory action research proved useful for attaining the goal set by the Austrian team of researchers: to re-interpret existing inclusive education practices in the classroom under the perspective of the UDL methodology. Participating teachers, students and parents identified good practices of inclusive education, as well as barriers that work against it. Together, they developed a research and action plan, and reflected on learner outcomes.

Collaborative Action Research

The Polish, Lithuanian and Finnish research teams used collaborative action research, where school and university teachers acted as co-researchers. The Polish group employed collaborative action research to reveal transformations to the educational process that took place when an inclusive classroom employed the UDL methodology; the Lithuanians employed the UDL strategy to identify the educational factors facilitating a student becoming an expert learner. The Finns used it to reveal the pedagogical competencies involved with teaching to a diverse group of students. The participatory action research conducted in Austria included collaboration between university researchers and teachers.

Collaborative action research is considered to be an efficient strategy for transforming a settled practice in schools to achieve clear goals for its improvement and as a way to both improve teachers’ professional competencies and create knowledge free from the boundaries of theory and practice (Mertler, 2019a ; Rowell et al., 2017 , Alber & Nelson, 2002 ). Some researchers (Kemmis et al., 2014 ) express a position that action research has to be carried out by teachers themselves, since this type of research involves a self-reflective and self-transformative process. However, the studies conducted by the teachers and researchers working together contradict this approach (Charalampous & Papademetriou, 2019 ; Kapenieks, 2016 ). In the research carried out by Olander and Holmqvist Olander ( 2013 ), teachers joined researchers to design and reflect on lessons, with the results of one planned and delivered lesson of biology serving as a basis for planning a second and then a third lesson. Olander and Holmqvist Olander ( 2013 , 210) state that teachers’ collaboration with researchers allowed them to identify what students do not know and to design efficient lesson models. Moreover, such collaboration “is an important tool and has potential to scaffold teachers’ professional development”. The results of the research presented by Messiou ( 2019 ) show that collaborative action research encourages the development of inclusive thinking and improves inclusive education practices.

The collaborative dialogue of school teachers and university lecturers, which led to deeper reflection, was one of the essential features of “Improving Inclusive Education Through Universal Design for Learning”, the international action research presented in this study. Teachers and researchers from Poland, Lithuania, Finland and Austria acted as co-researchers from the first stages of the action research process to the end. Researchers from universities in all the countries chose participating schools and where authorities and teachers would volunteer to join the projects. They also sought out and tested new strategies of inclusive education that aim to improve the quality of both inclusive education and student achievement in their schools. As mentioned above, university researchers and school teachers together held discussions about the problems with the quality of inclusive education in their countries, as well as changes that would need to be introduced. In their joint discussion, all the researchers and school teachers chose the UDL approach, predicting that its implementation could have a transformative impact in improving the quality of inclusive education in the problem areas identified in each country. The researchers and teachers all participated in the training courses, where lecturers from the organisation CAST, which has created and has been developing this approach, presented conceptual and practical aspects of UDL. The researchers and teachers together participated in the CAST webinars, which focused on such topics as “The conception and principles of UDL”, “Design of socio-educational environment based on the UDL principles”, “Planning the process of education, based on UDL principles”, “Implementation of UDL-based learning-teaching methods in the process of education. Observation and analysis of teaching videos using the UDL lens” and “Designing of UDL-based classroom settings and teaching/learning supplies” (2018). The researchers and teachers shared insights on contextualisation of UDL at school and its use for lesson planning. They looked at this through the prism of striving for a better quality of inclusive education, more ways of learning that best suits students and more goal-oriented learning. After every cycle of action research, a joint discussion was held with the Polish, Lithuanian, Finish and Austrian research teams. Teachers spoke with researchers while they also debated within their own separate groups.

Researchers and school teachers from all participating countries designed models of action research tailored to the problems that had been analysed, devised a three-point plan of action research and set goals for each phase. Discussing with the researchers and collecting data from others participating in the education process (learners and parents), the teachers from Poland, Lithuania and Finland identified the strengths of inclusive education, areas for improvement, and barriers in the educational process that prevent students from experiencing learning success in their schools. They also foresaw UDL-based actions that would eliminate barriers in the education process. Together with teachers, the researchers discussed the methods of data collection. The researchers observed the lessons delivered by teachers and, based on the results of previously taught lessons, discussed with teachers the planning of new lessons. The application of a UDL approach during lessons was also discussed among teachers. The teachers alone, as well as with the researchers, reflected on the results, problems and barriers of each cycle of action. As mentioned above, participatory action research was carried out in Austria, where teachers, students, parents and researchers participated in all stages.

To ensure the success of the joint researcher–teacher approach, researchers need to establish certain principles and conditions: a two-way empowering relationship with teachers (Datta et al., 2015 ); a clear discussion on research methods and process, as well as roles; scaffolding that helps teachers plan their activities (Mertler, 2019b ); reflections and participation in the learning process to form the foundation for improving teachers’ educational practice; reflections that need to be grounded in mutual trust and open to discussions surrounding difficulties (Insuasty & Jaime Osorio, 2020 ). All these conditions had been embedded in our research, with the resulting collaboration between researchers, teachers and other participants in the action research being warm, open and based on critical dialogue, reflection and scaffolding.

3.3 Cycles of Action Research

Action research is a cyclical process that involves identifying areas where there are problems and room for improvement, devising an action and implementation plan, setting up data collection, assessing and reflecting action and changes, and modifying the action plan. These all need to be considered for results to occur (Ferrance, 2000 ; Cohen et al., 2013 ; Charalampous & Papademetriou, 2019 ). Models of action research vary. Although the research teams from Poland, Lithuania, Finland and Austria applied different models of action research, all but one comprised three cycles (with Austria comprising two), which we present below.

The first cycle is aimed at analysing the context of inclusive education’s problem areas that were identified in Polish, Lithuanian, Finnish and Austrian schools, as well as identifying a specific research problem. Applying the UDL approach in the school of each country, best practices for organising inclusive education were evaluated and student learning barriers were identified from the perspective of teachers and students (The Austrians and Poles also identified barriers from the perspective of parents). Possible areas for improvement were identified, as were how the application of UDL can contribute to that improvement.

The second cycle applies the UDL approach as a means of eliminating student learning barriers identified in the first cycle and to improve the quality of inclusive education. Traditional routine teaching and learning was replaced with an educational processs grounded in the principles of UDL; the UDL approach was applied to help develop the qualities of students as expert learners; practices of inclusive education were re-interpreted and renewed in the context of the UDL approach; in the process of inclusive education and applying the UDL approach, teachers came together to reflect on the competencies that help them facilitate teaching a diverse set of learners. This second-cycle reflection touched on changes in the practice of teaching and learning, as well as in the attitudes of teachers and other participants, the factors that enhance the quality of inclusive education, and unresolved or newly identified barriers to student learning.

In the third cycle , the UDL approach was applied seeking to enhance the good practices of inclusive education, which had been modelled in the second cycle, and to eliminate the barriers to students learning, which had not been coped with in the second cycle or emerged anew. The change in the practice of teaching and learning as well as in the attitudes of teachers and other participants in the process of teaching, the factors that strengthen the quality of inclusive education, unresolved or newly identified challenges to further improvement of the quality of inclusive education students’ learning were reflected on in the third cycle. The third cycle of action research conducted by Finnish researchers focused on reflecting the teachers’ competence to work with a diversity of students in the classroom applying UDL.

It just so happened that due to the coronavirus outbreak the schools faced a problem in the third cycle of research. Challenges with distance learning begat new questions: How can the inclusive process be organised in the online classroom and made accessible to all students, including SEN learners; What are both the advantages and disadvantages of distance learning that make it possible or impossible to ensure inclusion for all students or individual learners; How does the UDL approach help to adapt to unexpected challenges and make the experience more dynamic?

3.4 Research Methods

The data collection in the action research aims to identify a specific problem, to then foresee what will be improved prior to devising an action plan. Implementing it requires reflection on changes in practices and attitudes and factors that had led to those changes (after implementation of action plan). The accumulated data enable understanding of what is going on in the classroom and what participants in the process of teaching and learning think about and how they approach their work. It also helps to identify actions that can stimulate changes that result from a specific action and how that result can be predicted and achieved. The methodology of action research is associated with a qualitative paradigm over a long period of time. For this reason, it seemed most appropriate to apply qualitative data collection and analysis methods (Dosemagen & Schwalbach, 2019 , 163). However, other researchers have expanded the field of methods applied in the action research and have used a mixed research approach (i.e. combining qualitative and quantitative methods) (Charalampous & Papademetriou, 2019 ). While they evaluated and understood their work by applying qualitative methods, their results were measured with quantitative methods (Parker et al., 2017 ). Ivanova and Wingo ( 2018 ) substantiated conceptual, philosophical and procedural aspects of using a mixed-method approach in action research. A multi-method approach is applied in the presented research, applying either qualitative research methods on their own or combining both qualitative and quantitative (Charalampous & Papademetriou, 2019 ). Various methods of data collection and analysis were used: interviews, diaries, video and audio recordings, questionnaires, etc. (Ferrance, 2000 ). It should be noted that qualitative methods of data collection and analysis prevail even when a mixed approach to research methods is followed.

A multi-method approach was applied in the research conducted by the Polish, Lithuanian and Finnish research teams while a qualitative research approach was applied in the research conducted by the Austrians. A more detailed description of applied methods is provided in chapters where the research results are presented.

The action research was conducted following all the ethical requirements. Informed consent (from students, their parents, teachers, school authorities) was obtained. To ensure confidentiality, the names of children and teachers were changed to pseudonyms and no details that could be linked with a particular person were presented. While writing the study, the participants in the research were provided with information on the research results.

3.5 Quality and Validity of Action Research

Bradbury et al. ( 2019 , 25) state that the quality of action research is ensured by (1) clearly defined goals, (2) partnership and participation, (3) contribution to action research theory practice, (4) appropriate methods and process, (5) actionability, (6) reflexivity and (7) significance. To ensure the validity of action research, researchers have to adhere to principles that ensure the research quality (Dosemagen & Schwalbach, 2019 ).

The validity of the action research conducted in Poland, Lithuania, Finland and Austria is guaranteed by the quality of its organisation. The common goals of this research and the aims of the first cycle were discussed and elaborated on in the joint meeting. The aims of the second cycle of action research emerged after reflections on the first cycle by the teams of each country and were discussed in the joint meeting of all the countries. The aims of the third cycle were based on the reflections of the second cycle and were discussed in by analogy, ensuring a clear and precise definition. The validity of research methods and procedures was ensured by the responsibility for their design, assumed by university researchers, active discussions with teachers in the research process and from analysing and reflecting on the data.

As stated, a participatory and collaborative approach to the research was followed at all stages. Continuous reflection was held at different action research stages, allowing for all the participants to engage in the action research.

The use of UDL’s theoretical approach for introducing changes to inclusive education practices ensured a connection between theory and practice. The teachers devised plans for UDL-based lessons and, during the course of their implementation, the impact on students’ participation in the lessons was observed, their choices of learning that were convenient to them, expressing the qualities of the expert learner and having an influence on student achievement. It was also observed and reflected on whether action research helps in coping with challenges encountered by schools and whether or not it provides any benefit to all the participants in the process of teaching and learning. All this created pre-requisites for re-interpretation of the very UDL approach from the perspective of its application in different socio-educational contexts for different purposes.

Limitations of Action Research

The results of action research are context-specific and, therefore, cannot be generalised (Dosemagen & Schwalbach, 2019 , 162). The results of one study cannot be applied when making predictions or conclusions about other groups. On the other hand, the processes of action research disclose how considerable changes can be modelled and implemented in different local contexts, how transformative social learning occurs when dialogue based, creative methods that change practice are applied. Action research encourages teachers’ engagement in solving complex problems in the local context. Moreover, according to Bradbury et al. ( 2019 , 27): “action research liberates learning from a consolation of facts to taking our own experience seriously”.

Alber, S. R., & Nelson, J. S. (2002). Putting research in the collaborative hands of teachers and researchers: An alternative to traditional staff development. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 21 (1), 24–30.

Article Google Scholar

Armstrong, F., & Tsokova, D. (2019). Action research for inclusive education: Participation and democracy in teaching and learning . Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Bradbury, H., Lewis, R., & Embury, D. C. (2019). Education action research: With and for the next generation. In C. A. Mertler (Ed.), The Wiley handbook of action research in education (pp. 7–28). Wiley/ProQuest Ebook Central.

Google Scholar

Charalampous, C., & Papademetriou, C. (2019). Action research: The key to inclusive education in Cyprus. Sciendo. Journal of Pedagogy, 10 (2), 37–64. https://doi.org/10.2478/jped-2019-0006

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2013). Research methods in education (p. 638). Routledge/Taylor and Francis Group.

Datta, R., Khyang, N. U., Prue Khyang, H. K., Prue Kheyang, H. A., Khyang, M. C., & Chapola, J. (2015). Participatory action research and researcher’s responsibilities: An experience with an indigenous community. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 18 (6), 581–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2014.927492

Dosemagen, D. M., & Schwalbach, E. M. (2019). Legitimacy of and value in action research. In C. A. Mertler (Ed.), The Wiley handbook of action research in education (pp. 161–168). Wiley/ProQuest Ebook Central.

Chapter Google Scholar

Ferrance, E. (2000). Action research. Northeast and Islands Regional Educational Laboratory at Brown University. https://www.brown.edu/academics/education-alliance/sites/brown.edu.academics.education-alliance/files/publications/act_research.pdf

Galkienė, A. (Ed.). (2017). Inclusion in socio-educational frames: Inclusive school cases in four European countries (pp. 93–99) . The Publishing House of the Lithuanian University of Educational Sciences.

Hackman, H. W. (2008). Broadening the pathway to academic success: The critical intersections of social justice education, critical multicultural education, and universal instructional design. In J. L. Higbee & E. Goff (Eds.), Pedagogy and student services for institutional transformation: Implementing universal design in higher education (pp. 25–48). University of Minnesota Printing Services.

Insuasty, E. A., & Jaime Osorio, M. F. (2020). Transforming pedagogical practices through collaborative work. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 22 (2), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v22n2.80289

Ivanova, N., & Wingo, N. (2018). Applying mixed methods in action research: Methodological potentials and advantages. American Behavioral Scientist, 62 (7), 978–997. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764218772673

Jacobs, S. (2016). The use of participatory action research within education–benefits to stakeholders. World Journal of Education, 6 (3), 48–55.

Jamaludin, A., Henik, A., & Hale, J. B. (2019). Educational neuroscience: Bridging theory and practice. Learning: Research and Practice, 5 (2), 93–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/23735082.2019.1685027

Kapenieks, J. (2016). Educational action research to achieve the essential competencies of the future. Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability, 18 (1), 95–110, https://doi.org/10.1515/jtes-2016-0008

Kemmis, S., McTaggart, R., & Nixon, R. (2014). The action research planner. Doing critical participatory action research (p. 200). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-4560-67-2

Mertler, C. A. (2019a). Introduction to educational research (2nd ed.). Sage.

Mertler, G. A. (Ed.). (2019b). The Wiley Handbook of Action Research in Education. Wiley.

Messiou, K. (2019). Collaborative action research: Facilitating inclusion in schools. Educational Action Research, 27 (2), 197–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2018.1436081

Meyer, A., Rose, D. H., & Gordon, D. (2014). Universal design for learning: Theory and practice (p. 234). CAST Professional Publishing an imprint of CAST.

Morales, M. P. E. (2016). Participatory action research (PAR) cum action research (AR) in teacher professional development: A literature review. International Journal of Research in Education and Science (IJRES), 2 (1), 156–165.

Olander, C., & Holmqvist Olander, M. (2013). Professional development through the use of learning study: Contributions to pedagogical content knowledge in biology. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 89 , 205–212.

Parker, V., Lieshke, G., & Giles, M. (2017). Ground-up-top down: A mixed method action research study aimed at normalising research in practice for nurses and midwives. BMC Nursing, 16 (52), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-017-0249-8

Rowe, W. E., Graf, M., Agger-Gupta, N., Piggot-Irvine, E., & Harris, B. (2013). In E. Piggot-Irvine (Ed.), Action research engagement: Creating the foundation for organizational change (p. 44). Action Learning, Action Research Association.

Rowell, L., Bruce, C., Shosh, J., & Riel, M. (Eds.). (2017). The Palgrave international handbook of action research . Palgrave Macmillan. https://www.amazon.com/Palgrave-International-Handbook-Action-Research/dp/1137441089

Scheurman, G. (2018). Constructivism and the new social studies: A collection of classic inquiry lessons (Studies in the history of education). Information Age Publishing.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes . Harvard University Press.

Wilson, B. G. (1996). Constructivist learning environments: Case studies in instructional design . Educational Technology Publications.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Vytautas Magnus University, Educational Aacademy, Kaunas, Lithuania

Ona Monkevičienė & Alvyra Galkienė

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ona Monkevičienė .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Educational Aacademy, Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas, Lithuania

Alvyra Galkienė & Ona Monkevičienė &

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Monkevičienė, O., Galkienė, A. (2021). Theoretical and Methodological Validation of the Action Research: Methodology of the Scientific Study. In: Galkienė, A., Monkevičienė, O. (eds) Improving Inclusive Education through Universal Design for Learning. Inclusive Learning and Educational Equity, vol 5. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80658-3_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80658-3_3

Published : 11 September 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-80657-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-80658-3

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4 Preparing for Action Research in the Classroom: Practical Issues

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS

- What sort of considerations are necessary to take action in your educational context?

- How do you facilitate an action plan without disrupting your teaching?

- How do you respond when the unplanned happens during data collection?

An action research project is a practical endeavor that will ultimately be shaped by your educational context and practice. Now that you have developed a literature review, you are ready to revise your initial plans and begin to plan your project. This chapter will provide some advice about your considerations when undertaking an action research project in your classroom.

Maintain Focus

Hopefully, you found a lot a research on your topic. If so, you will now have a better understanding of how it fits into your area and field of educational research. Even though the topic and area you are researching may not be small, your study itself should clearly focus on one aspect of the topic in your classroom. It is important to maintain clarity about what you are investigating because a lot will be going on simultaneously during the research process and you do not want to spend precious time on erroneous aspects that are irrelevant to your research.

Even though you may view your practice as research, and vice versa, you might want to consider your research project as a projection or megaphone for your work that will bring attention to the small decisions that make a difference in your educational context. From experience, our concern is that you will find that researching one aspect of your practice will reveal other interconnected aspects that you may find interesting, and you will disorient yourself researching in a confluence of interests, commitments, and purposes. We simply want to emphasize – don’t try to research everything at once. Stay focused on your topic, and focus on exploring it in depth, instead of its many related aspects. Once you feel you have made progress in one aspect, you can then progress to other related areas, as new research projects that continue the research cycle.

Identify a Clear Research Question

Your literature review should have exposed you to an array of research questions related to your topic. More importantly, your review should have helped identify which research questions we have addressed as a field, and which ones still need to be addressed . More than likely your research questions will resemble ones from your literature review, while also being distinguishable based upon your own educational context and the unexplored areas of research on your topic.

Regardless of how your research question took shape, it is important to be clear about what you are researching in your educational context. Action research questions typically begin in ways related to “How does … ?” or “How do I/we … ?”, for example:

Research Question Examples

- How does a semi-structured morning meeting improve my classroom community?

- How does historical fiction help students think about people’s agency in the past?

- How do I improve student punctuation use through acting out sentences?

- How do we increase student responsibility for their own learning as a team of teachers?

I particularly favor questions with I or we, because they emphasize that you, the actor and researcher, will be clearly taking action to improve your practice. While this may seem rather easy, you need to be aware of asking the right kind of question. One issue is asking a too pointed and closed question that limits the possibility for analysis. These questions tend to rely on quantitative answers, or yes/no answers. For example, “How many students got a 90% or higher on the exam, after reviewing the material three times?

Another issue is asking a question that is too broad, or that considers too many variables. For example, “How does room temperature affect students’ time-on-task?” These are obviously researchable questions, but the aim is a cause-and-effect relationship between variables that has little or no value to your daily practice.

I also want to point out that your research question will potentially change as the research develops. If you consider the question:

As you do an activity, you may find that students are more comfortable and engaged by acting sentences out in small groups, instead of the whole class. Therefore, your question may shift to:

- How do I improve student punctuation use through acting out sentences, in small groups ?

By simply engaging in the research process and asking questions, you will open your thinking to new possibilities and you will develop new understandings about yourself and the problematic aspects of your educational context.

Understand Your Capabilities and Know that Change Happens Slowly

Similar to your research question, it is important to have a clear and realistic understanding of what is possible to research in your specific educational context. For example, would you be able to address unsatisfactory structures (policies and systems) within your educational context? Probably not immediately, but over time you potentially could. It is much more feasible to think of change happening in smaller increments, from within your own classroom or context, with you as one change agent. For example, you might find it particularly problematic that your school or district places a heavy emphasis on traditional grades, believing that these grades are often not reflective of the skills students have or have not mastered. Instead of attempting to research grading practices across your school or district, your research might instead focus on determining how to provide more meaningful feedback to students and parents about progress in your course. While this project identifies and addresses a structural issue that is part of your school and district context, to keep things manageable, your research project would focus the outcomes on your classroom. The more research you do related to the structure of your educational context the more likely modifications will emerge. The more you understand these modifications in relation to the structural issues you identify within your own context, the more you can influence others by sharing your work and enabling others to understand the modification and address structural issues within their contexts. Throughout your project, you might determine that modifying your grades to be standards-based is more effective than traditional grades, and in turn, that sharing your research outcomes with colleagues at an in-service presentation prompts many to adopt a similar model in their own classrooms. It can be defeating to expect the world to change immediately, but you can provide the spark that ignites coordinated changes. In this way, action research is a powerful methodology for enacting social change. Action research enables individuals to change their own lives, while linking communities of like-minded practitioners who work towards action.

Plan Thoughtfully

Planning thoughtfully involves having a path in mind, but not necessarily having specific objectives. Due to your experience with students and your educational context, the research process will often develop in ways as you expected, but at times it may develop a little differently, which may require you to shift the research focus and change your research question. I will suggest a couple methods to help facilitate this potential shift. First, you may want to develop criteria for gauging the effectiveness of your research process. You may need to refine and modify your criteria and your thinking as you go. For example, we often ask ourselves if action research is encouraging depth of analysis beyond my typical daily pedagogical reflection. You can think about this as you are developing data collection methods and even when you are collecting data. The key distinction is whether the data you will be collecting allows for nuance among the participants or variables. This does not mean that you will have nuance, but it should allow for the possibility. Second, criteria are shaped by our values and develop into standards of judgement. If we identify criteria such as teacher empowerment, then we will use that standard to think about the action contained in our research process. Our values inform our work; therefore, our work should be judged in relation to the relevance of our values in our pedagogy and practice.

Does Your Timeline Work?

While action research is situated in the temporal span that is your life, your research project is short-term, bounded, and related to the socially mediated practices within your educational context. The timeline is important for bounding, or setting limits to your research project, while also making sure you provide the right amount of time for the data to emerge from the process.

For example, if you are thinking about examining the use of math diaries in your classroom, you probably do not want to look at a whole semester of entries because that would be a lot of data, with entries related to a wide range of topics. This would create a huge data analysis endeavor. Therefore, you may want to look at entries from one chapter or unit of study. Also, in terms of timelines, you want to make sure participants have enough time to develop the data you collect. Using the same math example, you would probably want students to have plenty of time to write in the journals, and also space out the entries over the span of the chapter or unit.

In relation to the examples, we think it is an important mind shift to not think of research timelines in terms of deadlines. It is vitally important to provide time and space for the data to emerge from the participants. Therefore, it would be potentially counterproductive to rush a 50-minute data collection into 20 minutes – like all good educators, be flexible in the research process.

Involve Others

It is important to not isolate yourself when doing research. Many educators are already isolated when it comes to practice in their classroom. The research process should be an opportunity to engage with colleagues and open up your classroom to discuss issues that are potentially impacting your entire educational context. Think about the following relationships:

Research participants

You may invite a variety of individuals in your educational context, many with whom you are in a shared situation (e.g. colleagues, administrators). These participants may be part of a collaborative study, they may simply help you develop data collection instruments or intervention items, or they may help to analyze and make sense of the data. While the primary research focus will be you and your learning, you will also appreciate how your learning is potentially influencing the quality of others’ learning.

We always tell educators to be public about your research, or anything exciting that is happening in your educational context, for that matter. In terms of research, you do not want it to seem mysterious to any stakeholder in the educational context. Invite others to visit your setting and observe your research process, and then ask for their formal feedback. Inviting others to your classroom will engage and connect you with other stakeholders, while also showing that your research was established in an ethic of respect for multiple perspectives.

Critical friends or validators

Using critical friends is one way to involve colleagues and also validate your findings and conclusions. While your positionality will shape the research process and subsequently your interpretations of the data, it is important to make sure that others see similar logic in your process and conclusions. Critical friends or validators provide some level of certification that the frameworks you use to develop your research project and make sense of your data are appropriate for your educational context. Your critical friends and validators’ suggestions will be useful if you develop a report or share your findings, but most importantly will provide you confidence moving forward.

Potential researchers

As an educational researcher, you are involved in ongoing improvement plans and district or systemic change. The flexibility of action research allows it to be used in a variety of ways, and your initial research can spark others in your context to engage in research either individually for their own purposes, or collaboratively as a grade level, team, or school. Collaborative inquiry with other educators is an emerging form of professional learning and development for schools with school improvement plans. While they call it collaborative inquiry, these schools are often using an action research model. It is good to think of all of your colleagues as potential research collaborators in the future.

Prioritize Ethical Practice

Try to always be cognizant of your own positionality during the action research process, its relation to your educational context, and any associated power relation to your positionality. Furthermore, you want to make sure that you are not coercing or engaging participants into harmful practices. While this may seem obvious, you may not even realize you are harming your participants because you believe the action is necessary for the research process.

For example, commonly teachers want to try out an intervention that will potentially positively impact their students. When the teacher sets up the action research study, they may have a control group and an experimental group. There is potential to impair the learning of one of these groups if the intervention is either highly impactful or exceedingly worse than the typical instruction. Therefore, teachers can sometimes overlook the potential harm to students in pursuing an experimental method of exploring an intervention.

If you are working with a university researcher, ethical concerns will be covered by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). If not, your school or district may have a process or form that you would need to complete, so it would beneficial to check your district policies before starting. Other widely accepted aspects of doing ethically informed research, include:

Confirm Awareness of Study and Negotiate Access – with authorities, participants and parents, guardians, caregivers and supervisors (with IRB this is done with Informed Consent).

- Promise to Uphold Confidentiality – Uphold confidentiality, to your fullest ability, to protect information, identity and data. You can identify people if they indicate they want to be recognized for their contributions.

- Ensure participants’ rights to withdraw from the study at any point .

- Make sure data is secured, either on password protected computer or lock drawer .

Prepare to Problematize your Thinking

Educational researchers who are more philosophically-natured emphasize that research is not about finding solutions, but instead is about creating and asking new and more precise questions. This is represented in the action research process shown in the diagrams in Chapter 1, as Collingwood (1939) notes the aim in human interaction is always to keep the conversation open, while Edward Said (1997) emphasized that there is no end because whatever we consider an end is actually the beginning of something entirely new. These reflections have perspective in evaluating the quality in research and signifying what is “good” in “good pedagogy” and “good research”. If we consider that action research is about studying and reflecting on one’s learning and how that learning influences practice to improve it, there is nothing to stop your line of inquiry as long as you relate it to improving practice. This is why it is necessary to problematize and scrutinize our practices.

Ethical Dilemmas for Educator-Researchers

Classroom teachers are increasingly expected to demonstrate a disposition of reflection and inquiry into their own practice. Many advocate for schools to become research centers, and to produce their own research studies, which is an important advancement in acknowledging and addressing the complexity in today’s schools. When schools conduct their own research studies without outside involvement, they bypass outside controls over their studies. Schools shift power away from the oversight of outside experts and ethical research responsibilities are shifted to those conducting the formal research within their educational context. Ethics firmly grounded and established in school policies and procedures for teaching, becomes multifaceted when teaching practice and research occur simultaneously. When educators conduct research in their classrooms, are they doing so as teachers or as researchers, and if they are researchers, at what point does the teaching role change to research? Although the notion of objectivity is a key element in traditional research paradigms, educator-based research acknowledges a subjective perspective as the educator-researcher is not viewed separately from the research. In action research, unlike traditional research, the educator as researcher gains access to the research site by the nature of the work they are paid and expected to perform. The educator is never detached from the research and remains at the research site both before and after the study. Because studying one’s practice comprises working with other people, ethical deliberations are inevitable. Educator-researchers confront role conflict and ambiguity regarding ethical issues such as informed consent from participants, protecting subjects (students) from harm, and ensuring confidentiality. They must demonstrate a commitment toward fully understanding ethical dilemmas that present themselves within the unique set of circumstances of the educational context. Questions about research ethics can feel exceedingly complex and in specific situations, educator- researchers require guidance from others.

Think about it this way. As a part-time historian and former history teacher I often problematized who we regard as good and bad people in history. I (Clark) grew up minutes from Jesse James’ childhood farm. Jesse James is a well-documented thief, and possibly by today’s standards, a terrorist. He is famous for daylight bank robberies, as well as the sheer number of successful robberies. When Jesse James was assassinated, by a trusted associate none-the-less, his body travelled the country for people to see, while his assailant and assailant’s brother reenacted the assassination over 1,200 times in theaters across the country. Still today in my hometown, they reenact Jesse James’ daylight bank robbery each year at the Fall Festival, immortalizing this thief and terrorist from our past. This demonstrates how some people saw him as somewhat of hero, or champion of some sort of resistance, both historically and in the present. I find this curious and ripe for further inquiry, but primarily it is problematic for how we think about people as good or bad in the past. Whatever we may individually or collectively think about Jesse James as a “good” or “bad” person in history, it is vitally important to problematize our thinking about him. Talking about Jesse James may seem strange, but it is relevant to the field of action research. If we tell people that we are engaging in important and “good” actions, we should be prepared to justify why it is “good” and provide a theoretical, epistemological, or ontological rationale if possible. Experience is never enough, you need to justify why you act in certain ways and not others, and this includes thinking critically about your own thinking.

Educators who view inquiry and research as a facet of their professional identity must think critically about how to design and conduct research in educational settings to address respect, justice, and beneficence to minimize harm to participants. This chapter emphasized the due diligence involved in ethically planning the collection of data, and in considering the challenges faced by educator-researchers in educational contexts.

Planning Action

After the thinking about the considerations above, you are now at the stage of having selected a topic and reflected on different aspects of that topic. You have undertaken a literature review and have done some reading which has enriched your understanding of your topic. As a result of your reading and further thinking, you may have changed or fine-tuned the topic you are exploring. Now it is time for action. In the last section of this chapter, we will address some practical issues of carrying out action research, drawing on both personal experiences of supervising educator-researchers in different settings and from reading and hearing about action research projects carried out by other researchers.

Engaging in an action research can be a rewarding experience, but a beneficial action research project does not happen by accident – it requires careful planning, a flexible approach, and continuous educator-researcher reflection. Although action research does not have to go through a pre-determined set of steps, it is useful here for you to be aware of the progression which we presented in Chapter 2. The sequence of activities we suggested then could be looked on as a checklist for you to consider before planning the practical aspects of your project.

We also want to provide some questions for you to think about as you are about to begin.

- Have you identified a topic for study?

- What is the specific context for the study? (It may be a personal project for you or for a group of researchers of which you are a member.)

- Have you read a sufficient amount of the relevant literature?

- Have you developed your research question(s)?

- Have you assessed the resource needed to complete the research?

As you start your project, it is worth writing down:

- a working title for your project, which you may need to refine later;

- the background of the study , both in terms of your professional context and personal motivation;

- the aims of the project;

- the specific outcomes you are hoping for.

Although most of the models of action research presented in Chapter 1 suggest action taking place in some pre-defined order, they also allow us the possibility of refining our ideas and action in the light of our experiences and reflections. Changes may need to be made in response to your evaluation and your reflections on how the project is progressing. For example, you might have to make adjustments, taking into account the students’ responses, your observations and any observations of your colleagues. All this is very useful and, in fact, it is one of the features that makes action research suitable for educational research.

Action research planning sheet

In the past, we have provided action researchers with the following planning list that incorporates all of these considerations. Again, like we have said many times, this is in no way definitive, or lock-in-step procedure you need to follow, but instead guidance based on our perspective to help you engage in the action research process. The left column is the simplified version, and the right column offers more specific advice if need.

Figure 4.1 Planning Sheet for Action Research

Action Research Copyright © by J. Spencer Clark; Suzanne Porath; Julie Thiele; and Morgan Jobe is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- MyExperience

- Faculty of Education

An Introduction to Action Research

Home » Background of The Study – Examples and Writing Guide

Background of The Study – Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Background of The Study

Definition:

Background of the study refers to the context, circumstances, and history that led to the research problem or topic being studied. It provides the reader with a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter and the significance of the study.

The background of the study usually includes a discussion of the relevant literature, the gap in knowledge or understanding, and the research questions or hypotheses to be addressed. It also highlights the importance of the research topic and its potential contributions to the field. A well-written background of the study sets the stage for the research and helps the reader to appreciate the need for the study and its potential significance.

How to Write Background of The Study

Here are some steps to help you write the background of the study:

Identify the Research Problem

Start by identifying the research problem you are trying to address. This problem should be significant and relevant to your field of study.

Provide Context

Once you have identified the research problem, provide some context. This could include the historical, social, or political context of the problem.

Review Literature

Conduct a thorough review of the existing literature on the topic. This will help you understand what has been studied and what gaps exist in the current research.

Identify Research Gap

Based on your literature review, identify the gap in knowledge or understanding that your research aims to address. This gap will be the focus of your research question or hypothesis.

State Objectives

Clearly state the objectives of your research . These should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART).

Discuss Significance

Explain the significance of your research. This could include its potential impact on theory , practice, policy, or society.

Finally, summarize the key points of the background of the study. This will help the reader understand the research problem, its context, and its significance.

How to Write Background of The Study in Proposal

The background of the study is an essential part of any proposal as it sets the stage for the research project and provides the context and justification for why the research is needed. Here are the steps to write a compelling background of the study in your proposal:

- Identify the problem: Clearly state the research problem or gap in the current knowledge that you intend to address through your research.

- Provide context: Provide a brief overview of the research area and highlight its significance in the field.

- Review literature: Summarize the relevant literature related to the research problem and provide a critical evaluation of the current state of knowledge.

- Identify gaps : Identify the gaps or limitations in the existing literature and explain how your research will contribute to filling these gaps.

- Justify the study : Explain why your research is important and what practical or theoretical contributions it can make to the field.

- Highlight objectives: Clearly state the objectives of the study and how they relate to the research problem.

- Discuss methodology: Provide an overview of the methodology you will use to collect and analyze data, and explain why it is appropriate for the research problem.

- Conclude : Summarize the key points of the background of the study and explain how they support your research proposal.

How to Write Background of The Study In Thesis

The background of the study is a critical component of a thesis as it provides context for the research problem, rationale for conducting the study, and the significance of the research. Here are some steps to help you write a strong background of the study: