An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychiatry

Family and Academic Stress and Their Impact on Students' Depression Level and Academic Performance

1 School of Mechatronics Engineering, Daqing Normal University, Daqing, China

2 School of Marxism, Heilongjiang University, Harbin, China

Jacob Cherian

3 College of Business, Abu Dhabi University, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

Noor Un Nisa Khan

4 Faculty of Business Administration, Iqra University Karachi Pakistan, Karachi, Pakistan

Kalpina Kumari

5 Faculty of Department of Business Administration, Greenwich University Karachi, Karachi, Pakistan

Muhammad Safdar Sial

6 Department of Management Sciences, COMSATS University Islamabad (CUI), Islamabad, Pakistan

Ubaldo Comite

7 Department of Business Sciences, University Giustino Fortunato, Benevento, Italy

Beata Gavurova

8 Faculty of Mining, Ecology, Process Control and Geotechnologies, Technical University of Kosice, Kosice, Slovakia

József Popp

9 Hungarian National Bank–Research Center, John von Neumann University, Kecskemét, Hungary

10 College of Business and Economics, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

Associated Data

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Current research examines the impact of academic and familial stress on students' depression levels and the subsequent impact on their academic performance based on Lazarus' cognitive appraisal theory of stress. The non-probability convenience sampling technique has been used to collect data from undergraduate and postgraduate students using a modified questionnaire with a five-point Likert scale. This study used the SEM method to examine the link between stress, depression, and academic performance. It was confirmed that academic and family stress leads to depression among students, negatively affecting their academic performance and learning outcomes. This research provides valuable information to parents, educators, and other stakeholders concerned about their childrens' education and performance.

Introduction

Higher education institutions (HEIs) are believed to be one of the strongest pillars in the growth of any nation ( 1 ). Being the principal stakeholder, the performance of HEIs mainly relies on the success of its students ( 2 ). To successfully compete in the prevailing dynamic industrial environment, students are not only supposed to develop their knowledge but are also expected to have imperative skills and abilities ( 3 ). In the current highly competitive academic environment, students' performance is largely affected by several factors, such as social media, academic quality, family and social bonding, etc. ( 4 ). Aafreen et al. ( 2 ) stated that students continuously experience pressure from different sources during academic life, which ultimately causes stress among students.

Stress is a common factor that largely diminishes individual morale ( 5 ). It develops when a person cannot handle their inner and outer feelings. When the stress becomes chronic or exceeds a certain level, it affects an individual's mental health and may lead to different psychological disorders, such as depression ( 6 ). Depression is a worldwide illness marked by feelings of sadness and the inability to feel happy or satisfied ( 7 ). Nowadays, it is a common disorder, increasing day by day. According to the World Health Organization ( 8 , 9 ), depression was ranked third among the global burden of disease and predicted to take over first place by 2030.

Depression leads to decreased energy, difficulty thinking, concentrating, and making career decisions ( 6 ). Students are a pillar of the future in building an educated society. For them, academic achievement is a big goal of life and can severely be affected if the students fall prey to depression ( 10 , 11 ). There can be several reasons for this: family issues, exposure to a new lifestyle in colleges and universities, poor academic grades, favoritism by teachers, etc. Never-ending stress or academic pressure of studies can also be a chief reason leading to depression in students ( 12 ). There is a high occurrence of depression in emerging countries, and low mental health literacy has been theorized as one of the key causes of escalating rates of mental illness ( 13 ).

Several researchers, such as ( 6 , 14 , 15 ) have studied stress and depression elements from a performance perspective and reported that stress and depression negatively affect the academic performance of students. However, Aafreen et al. ( 2 ) reported contradictory results and stated that stress sharpens the individual's mind and reflexes and enables workers to perform better in taxing situations. Ardalan ( 16 ) conducted a study in the United States (US). They reported that depression is a common issue among students in the US, and 20 percent of them may have a depressive disorder spanning 12 months or more. It affects students' mental and physical health and limits their social relationships and professional career.

However, the current literature provides mixed results on the relationship between stress and performance. Therefore, the current research investigates stress among students from family and academic perspectives using Lazaru's theory which describes stress as a relation between an individual and his environment and examines how it impacts students' depression level, leading to their academic performance. Most of the available studies on stress and depression are from industrial perspectives, and limited attention is paid to stress from family and institutional perspectives and examines its impact on students' depression level, leading to their academic performance, particularly in Pakistan, the place of the study. Besides, the present study follows a multivariate statistical technique, followed by structural equation modeling (SEM) to examine the relationship between stated variables which is also a study's uniqueness.

This paper is divided into five main sections. The current section provided introduction, theoretical perspective, and background of the study. In the second section, a theoretical framework, a detailed literature review and research hypotheses of the underlying relationships are being proposed. In the third and fourth section, methodology and analysis have been discussed. Finally, in the last section, the conclusion, limitations, implications, and recommendations for future research have been proposed.

Theory and Literature

The idea of cognitive appraisal theory was presented in 1966 by psychologist Richard Lazarus in Psychological Stress and Coping Process. According to this theory, appraisal and coping are two concepts that are central to any psychological stress theory. Both are interrelated. According to the theory, stress is the disparity between stipulations placed on the individuals and their coping resources ( 17 ). Since its first introduction as a comprehensive theory ( 18 ), a few modifications have been experienced in theory later. The recent adaptation states that stress is not defined as a specific incitement or psychological, behavioral, or subjective response. Rather, stress is seen as a relation between an individual and his environment ( 19 ). Individuals appraise the environment as significant for their well-being and try to cope with the exceeding demands and challenges.

Cognitive appraisal is a model based on the idea that stress and other emotional processes depend on a person's expectancies regarding the significance and outcome of an event, encounter, or function. This explains why there are differences in intensity, duration, and quality of emotions elicited in people in response to the environment, which objectively, are equal for all ( 18 ). These appraisals may be influenced by various factors, including a person's goals, values, motivations, etc., and are divided into primary and secondary appraisals, specific patterns of which lead to different kinds of stress ( 20 ). On the other hand, coping is defined as the efforts made by a person to minimize, tolerate, or master the internal and external demands placed on them, a concept intimately related to cognitive appraisal and, therefore, to the stress-relevant person-environment transactions.

Individuals experience different mental and physiological changes when encountering pressure, such as stress ( 21 , 22 ). The feelings of stress can be either due to factors in the external environment or subjective emotions of individuals, which can even lead to psychological disorders such as anxiety and depression. Excess stress can cause health problems. A particularly negative impact has been seen in students due to the high level of stress they endure, affecting their learning outcomes. Various methods are used to tackle stress. One of the methods is trying to pinpoint the causes of stress, which leads us to different terms such as family stress and academic stress. The two factors, stress and depression, have greatly impacted the students' academic performances. This research follows the Lazarus theory based on stress to examine the variables. See the conceptual framework of the study in Figure 1 .

Conceptual framework.

Academic Stress

Academic issues are thought to be the most prevalent source of stress for college students ( 23 ). For example, according to Yang et al. ( 24 ), students claimed that academic-related pressures such as ongoing study, writing papers, preparing for tests, and boring professors were the most important daily problems. Exams and test preparation, grade level competitiveness, and gaining a big quantity of knowledge in a short period of time all contribute to academic pressure. Perceived stress refers to a condition of physical or psychological arousal in reaction to stressors ( 25 , 26 ). When college students face excessive or negative stress, they suffer physical and psychological consequences. Excessive stress can cause health difficulties such as fatigue, loss of appetite, headaches, and gastrointestinal issues. Academic stress has been linked to a variety of negative effects, including ill health, anxiety, depression, and poor academic performance. Travis et al. ( 27 ), in particular, discovered strong links between academic stress and psychological and physical health.

Family Stress

Parental participation and learning effect how parents treat their children, as well as how they handle their children's habits and cognitive processes ( 28 ). This, in turn, shapes their children's performance and behaviors toward them. As a result, the parent-child relationship is dependent on the parents' attitudes, understanding, and perspectives. When parents have positive views, the relationship between them and their children will be considerably better than when they have negative attitudes. Parents respond to unpleasant emotions in a variety of ways, which can be classified as supportive or non-supportive ( 29 ). Parents' supportive reactions encourage children to explore their emotions by encouraging them to express them or by assisting them in understanding and coping with an emotion-eliciting scenario. Non-supportive behaviors, such as downplaying the kid's emotional experience, disciplining the child, or getting concerned by the child's display, transmit the child the message that expressing unpleasant emotions is inappropriate and unacceptable. Supportive parental reactions to unpleasant emotions in children have been linked to dimensions of emotional and social competence, such as emotion comprehension and friendship quality. Non-supportive or repressive parental reactions, on the other hand, have been connected to a child's stored negative affect and disordered behaviors during emotion-evoking events, probably due to an inability or unwillingness to communicate unpleasant sentiments ( 30 , 31 ).

Academic Stress and Students' Depression Levels

Generally, it is believed that mental health improves as we enter into adulthood, and depression disorder starts to decline between the age of 18 and 25. On the other hand, excessive depression rates are the highest pervasiveness during this evolution ( 15 ), and many university students in the particular screen above clinical cut-off scores for huge depression ( 14 , 32 ). Afreen et al. ( 2 ) stated that 30% of high school students experience depression from different perspectives. This means a major chunk of fresh high school graduates are more likely to confront depression or are more vulnerable to encountering depression while enrolling in the university. As the students promote to a higher level of education, there are many factors while calculating the stress like, for example, the syllabus is tough to comprehend, assignments are quite challenging with unrealistic deadlines, and accommodation problems for the students who are shifted from other cities, etc. ( 33 ). Experiences related to university can also contribute while studying depression. The important thing to consider is depression symptoms vary from time to time throughout the academic years ( 34 ); subjective and objective experiences are directly connected to the depression disorder ( 6 ), stress inherent in the university situation likely donates to the difference in university students' depressing experiences.

Stress negatively impacts students' mental peace, and 42.3% of students of Canadian university respondents testified devastating levels of anxiety and stress ( 35 , 36 ). Moreover, there were (58.1%) students who stated academic projects are too tough to handle for them. In Germany, Bulgaria, and Poland, a huge sample of respondents consider assignments a burden on their lives that cannot stand compared to relationships or any other concern in life ( 14 ).

In several countries, university students were studied concerning stress, and results show that depression disorder and apparent anxiety are correlated to educational needs and demands ( 37 ). In their cross-sectional study conducted on a sample of 900 Canadian students, Lörz et al. ( 38 ) concluded that strain confronted due to academic workload relatively has high bleak symptoms even after controlling 13 different risk affecting factors for depression (e.g., demographic features, abusive past, intellectual way, and personality, currently experienced stressful trials in life, societal support). Few have exhibited that students who are tired of educational workload or the students who name them traumatic tend to have more depressing disorders ( 15 ).

These relations can be described by examining the stress and coping behaviors that highlight the role of positive judgments in the stress times ( 39 ), containing the Pancer and colleagues' university modification framework ( 40 , 41 ). The evaluation concept includes examining the circumstances against the available resources, for instance, the effectiveness of coping behavior and societal support. As per these frameworks, if demand is considered unapproachable and resources are lacking, confronted stress and interrelated adverse effects will be high, conceivably giving birth to difficulties in an adjustment like mental instability. Stress triggering situations and the resources in the educational area led to excessive workload, abilities, and study and enhanced time managing skills.

Sketching the overall evaluation frameworks, Pancer et al. ( 40 ) established their framework to exhibit the constructive and damaging adjustment results for the university students dealing with the academic challenges. They stated that while students enroll in the university, they evaluate all the stress-related factors that students confront. They consider them manageable as long as they have sufficient resources. On the other hand, if the available resources do not match the stress factors, it will surely result in a negative relationship, which will lead students to experience depression for sure. Based on the given arguments, the researcher formulates the following hypothesis:

- H1: Increased academic stress results in increased depression levels in students.

Family Stress and Students' Depression Levels

According to Topuzoglu et al. ( 42 ), 3% to 16.9% of individuals are affected by depression worldwide. There are fewer chances for general people to confront depression than university students ( 43 , 44 ). In Mirza et al.'s ( 45 ) study, 1/3 of students encounter stress and depression (a subjective mean occurrence of 30.6%) of all participant students, which suggests students have a 9% higher rate of experiencing depression than general people. Depression can destroy life; it greatly impacts living a balanced life. It can impact students' personal and social relationships, educational efficiency, quality of life, affecting their social and family relationships, academic productivity, and bodily operations ( 46 , 47 ). This declines their abilities, and they get demotivated to learn new things, resulting in unsatisfactory performances, and it can even result in university dropouts ( 48 ). Depression is a continuous substantial risk aspect for committing suicide for university students ( 49 ); thus, it is obliged to discover the factors that can give rise to students' depression.

Seventy-five percentage of students in China of an intermediate school are lucky enough to enroll in higher education. The more students pursue higher education, the more they upsurge for depression (in 2002, the depression rate was 5 to 10%, 2011 it rises 24 to 38%) ( 5 ). Generally, University students' age range is late teens to early twenties, i.e., 18–23 years. Abbas ( 50 ) named the era of university students as “post-adolescence. Risk factors for teenage depression have several and complicated problems of individual characteristics and family and educational life ( 51 ). Amongst the huge depression factors, relationship building with family demands a major chunk of attention and time since factors like parenting and family building play an important role in children's development ( 52 , 53 ). Halonen et al. ( 54 ) concluded that factors like family binding play a major role in development, preservation, and driving adolescent depression. Generally speaking, depressed teenagers tend to have a weaker family relationship with their parents than non-depressed teenagers.

There are two types of family risk factors, soft and hard. Hard factors are encountered in families with a weak family building structure, parents are little to no educated at all, and of course, the family status (economically). Several studies have proved that students of hard risk factors are more likely to encounter depression. Firstly, students from broken families have low confidence in every aspect of life, and they are weak at handling emotional breakdowns compared to students from complete and happy families ( 55 – 57 ). Secondly, the university students born in educated families, especially mothers (at least a college degree or higher degree), are less likely to confront depression than the university students born in families with little to no educated families. Secondly, children born with educated mothers or mothers who at least have a college degree tend to be less depressive than the children of less-educated mothers ( 58 ). However, Parker et al. and Mahmood et al. ( 59 , 60 ) stated a strong relationship between depression and mothers with low literacy levels.

On the other hand, Chang et al. ( 46 ) couldn't prove the authentication of this relationship in university students. Thirdly, university students who belong to lower class families tend to have more unstable mental states and are more likely to witness depression than middle or upper-class families ( 61 ). Jadoon et al. and Abbas et al. ( 62 , 63 ) said that there is no link between depression and economic status. Their irrelevance can be because medical students often come from educated and wealthy families and know their jobs are guaranteed as soon as they graduate. Therefore, the relationship between the hard family environment and depression can be known by targeting a huge audience, and there are several factors to consider while gauging this relationship.

The soft family environment is divided into clear factors (parenting style example, family guidelines, rules, the parent with academic knowledge, etc.) and implied factors (family norm, parent-child relationship, communication within the family, etc.). The soft factor is the key factor within the family that cannot be neglected while studying the teenagers' mental state or depression. Families make microsystems within the families, and families are the reason to build and maintain dysfunctional behavior by multiple functional procedures ( 64 ). Amongst the soft family environmental factors, consistency and struggles can be helpful while forecasting the mental health of teenagers. The youth of broken families, family conflict, weak family relationships, and marital issues, especially unhappy married life, are major factors for youth depression ( 65 ). Ruchkin et al. ( 66 ) stated that African Americans usually have weak family bonding, and their teenagers suffer from depression even when controlling for source bias. Whereas, few researchers have stated, family unity is the most serious factor while foreseeing teenagers' depression. Eaton noted that extreme broken family expressions might hurt emotionality and emotional regulation ( 67 , 68 ).

Social circle is also considered while studying depression in teenagers ( 69 – 71 ). The traditional Pakistani culture emphasizes collectivism and peace and focuses on blood relations and sensitive sentiments. Adolescents with this type of culture opt to get inspired by family, but students who live in hostels or share the room with other students lose this family inspiration. This transformation can be a big risk to encounter depression ( 72 ). Furthermore, in Pakistan securing employment is a big concern for university students. If they want a good job in the future, they have to score good grades and maintain GPA from the beginning. They have to face different challenges all at once, like aggressive educational competition, relationships with peers and family, and of course the biggest employment stress all alone. The only source for coping with these pressures is the family that can be helpful for fundings. If the students do not get ample support the chances are of extreme depression. The following hypothesis is suggested:

- H2: Increased family stress level results in increased depression levels in students.

Students' Depression Levels and Students' Academic Performance

University students denote many people experiencing a crucial conversion from teenagers to adulthood: a time that is generally considered the most traumatic time in one's ( 73 ). This then gets accumulated with other challenges like changes in social circle and exams tension, which possibly puts students' mental health at stake. It has been concluded that one-third of students experience moderate to severe depression in their entire student life ( 74 ). This is the rate that can be increased compared to the general people ( 75 , 76 ). Students with limited social-class resources tend to be more helpless. Additionally, depressed students in attainable-focused environments (for instance, higher academic institutes) are likely to score lower grades with a sense of failure and more insufficient self-assurance because they consider themselves failures, find the world unfair, and have future uncertainties. Furthermore, students with low self-esteem are rigid to take on challenging assignments and projects, hence they are damaging their educational career ( 77 ).

Depression can be defined as a blend of physical, mental, bodily processes, and benightedness which can make themselves obvious by symptoms like, for example, poor sleep schedule, lack of concentration, ill thoughts, and state of remorse ( 78 , 79 ). But, even after such a huge number of depressions in students and the poor academic system, research has not explored the effect of depression on educational performance. A study has shown that the relationship between emotional stability and academic performance in university students and financial status directly results in poor exam performance. As the study further concluded, it was verified depression is an independent factor ( 80 ). Likewise, students suffering from depression score poor grades, but this relationship vanished if their depression got treated. Apart from confidence breaking, depression is a big failure for their academic life. Students with depression symptoms bunk more classes, assessments, and assignments. They drop courses if they find them challenging than non-depressed peers, and they are more likely to drop out of university completely ( 81 ). Students suffering from depression can become ruthless, ultimately affecting their educational performance and making them moody ( 82 ).

However, it has been stated that the association between anxiety and educational performance is even worse and ambiguous. At the same time, some comprehensive research has noted that the greater the anxiousness, the greater the student's performance. On the other hand, few types of research have shown results where there is no apparent relationship between anxiety and poorer academic grades ( 83 ). Ironically, few studies have proposed that a higher anxiety level may improve academic performance ( 84 , 85 ). Current research by Khan et al. ( 86 ) on the undergraduate medical students stated that even though the high occurrence of huge depression between the students, the students GPA is unharmed. Therefore, based on given differences in various research findings, this research is supposed to find a more specific and clear answer to the shared relationship between students' depression levels and academic performance. Based on the given arguments, the researcher formulates the following hypothesis:

- H3: Students' depression level has a significant negative effect on their academic performance.

Methodology

Target population and sampling procedure.

The target audience of this study contains all male and female students studying in the public, private, or semi-government higher education institutions located in Rawalpindi/Islamabad. The researchers collected data from undergraduate and postgraduate students from the management sciences, engineering, and computer science departments. The sampling technique which has been used is the non-probability sampling technique. A questionnaire was given to the students, and they were requested to fill it and give their opinion independently. The questionnaire is based on five points Likert scale.

However, stress and depression are the most common issue among the students, which affects their learning outcomes adversely. A non-probability sampling technique gathered the data from February 2020 to May 2020. The total questionnaires distributed among students were 220, and 186 responses were useful. Of which 119 respondents were females, 66 males, and 1 preferred not to disclose. See Table 1 for detailed demographic information of respondents.

Respondent's demographic profile.

Measurement Scales

We have divided this instrument into two portions. In the first section, there is demographic information of respondents. The second section includes 14 items based on family stress, academic stress, students' depression levels, and students' academic performance. Academic and family stress were measured by 3 item scale for each construct, and students' depression level and academic performance were measured by 4 item scale for each separate construct. The five-point Likert scale is used to measure the items, in which one signifies strongly disagree (S.D), second signifies disagree (D.A), third signifies neither agree nor disagree (N), fourth signifies agree (A.G), and the fifth signifies strongly agree (S.A). The questionnaire has been taken from Gold Berg ( 87 ), which is modified and used in the given questionnaire.

Data Analysis and Results

The researchers used the SEM technique to determine the correlation between stress, depression, and academic performance. According to Prajogo and Cooper ( 88 ), it can remove biased effects triggered by the measurement faults and shape a hierarchy of latent constructs. SPSS v.23 and AMOS v.23 have been used to analyze the collected data. Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test is used to test the competence of the sample. The value obtained is 0.868, which fulfills the Kaiser et al. ( 89 ), a minimum requirement of 0.6. The multicollinearity factor was analyzed through the variance inflation factor (VIF). It shows the value of 3.648 and meets the requirement of Hair et al. ( 90 ), which is < 4. It also indicates the absence of multicollinearity. According to Schwarz et al. ( 91 ), common method bias (CMB) is quite complex in quantitative studies. Harman's test of a single factor has been used to analyze CMB. The result obtained for the single factor is 38.63%. As stated by Podsakoff et al. ( 92 ), if any of the factors gives value < 50% of the total variance, it is adequate and does not influence the CMB. Therefore, we can say that there is no issue with CMB. Considering the above results are adequate among the measurement and structural model, we ensure that the data is valued enough to analyze the relation.

Assessment of the Measurement and Structural Model

The association between the manifest factors and their elements is examined by measuring model and verified by the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). CFA guarantees legitimacy and the unidimensional of the measurement model ( 93 ). Peterson ( 94 ) stated that the least required, i.e., 0.8 for the measurement model, fully complies with its Cronbach's alpha value, i.e., 0.802. Therefore, it can confidently be deduced that this measurement model holds satisfactory reliability. As for the psychological legitimacy can be analyzed through factor loading, where the ideal loading is above 0.6 for already established items ( 95 ). Also, according to the recommendation of Molina et al. ( 96 ), the minimum value of the average variance extracted (AVE) for all results is supposed to be >0.5. Table 2 gives detail of the variables and their quantity of things, factor loading, merged consistency, and AVE values.

Instrument reliability and validity.

A discriminant validity test was performed to ensure the empirical difference of all constructs. For this, it was proposed by Fornell and Larcker ( 97 ) that the variance of the results is supposed to be greater than other constructs. The second indicator of discriminant validity is that the square root values of AVE have a greater correlation between the two indicators. Hair et al. ( 90 ) suggested that the correlation between the pair of predictor variables should not be higher than 0.9. Table 3 shows that discriminant validity recommended by Hair et al. ( 90 ) and Fornell and Larcker ( 97 ) was proved clearly that both conditions are fulfilled and indicates that the constructs have adequate discriminant validity.

Discriminant validity analysis.

Acd. Strs, Academic Stress; Fam. Strs, Family Stress; Std. Dep. Lev, Student's Depression Level; Std. Acd. Perf, Student's Academic Performance .

Kaynak ( 98 ) described seven indicators that ensure that the measurement model fits correctly. These indicators include standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR), root means a square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), normative fit index (NFI), adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), the goodness of fit index (GFI) and chi-square to a degree of freedom (x 2 /DF). Tucker-Lewis's index (TLI) is also included to ensure the measurement and structural model's fitness. In the measurement model, the obtained result shows that the value of x 2 /DF is 1.898, which should be lower than 2 suggested by Byrne ( 99 ), and this value also meets the requirement of Bagozzi and Yi ( 100 ), i.e., <3. The RMSEA has the value 0.049, which fully meets the requirement of 0.08, as stated by Browne and Cudeck ( 101 ). Furthermore, the SRMR acquired value is 0.0596, which assemble with the required need of < 0.1 by Hu and Bentler ( 102 ). Moreover, according to Bentler and Bonett ( 103 ), McDonald and Marsh ( 104 ), and Bagozzi and Yi ( 100 ), the ideal value is 0.9, and the values obtained from NFI, GFI, AGFI, CFI, and TLI are above the ideal value.

Afterward, the structural model was analyzed and achieved the findings, which give the value of x 2 /DF 1.986. According to Browne and Cudeck ( 101 ), the RMSEA value should not be greater than 0.08, and the obtained value of RMSEA is 0.052, which meets the requirement perfectly. The minimum requirement of Hu and Bentler ( 102 ) should be <0.1, for the structural model fully complies with the SRMR value 0.0616. According to a recommendation of McDonald and Marsh ( 104 ) and Bagozzi and Yi ( 100 ), the ideal value must be up to 0.9, and Table 4 also shows that the values of NFI, GFI, AGFI, CFI, and TLI, which are above than the ideal value and meets the requirement. The above results show that both the measurement and structural models are ideally satisfied with the requirements and the collected data fits correctly.

Analysis of measurement and structural model.

Testing of Hypotheses

The SEM technique is used to examine the hypotheses. Each structural parameter goes along with the hypothesis. The academic stress (Acd. Strs) with the value β = 0.293 while the p -value is 0.003. These outcomes show a significant positive relationship between academic stress (Acd. Strs) and students' depression levels (Std. Dep. Lev). With the β = 0.358 and p = 0.001 values, the data analysis discloses that the family stress (Fam. Strs) has a significant positive effect on the students' depression level (Std. Dep. Lev). However, the student's depression level (Std. Dep. Lev) also has a significant negative effect on their academic performance (Std. Acd. Perf) with the values of β = −0.319 and p = 0.001. Therefore, the results supported the following hypotheses H 1 , H 2 , and H 3 . The sub-hypotheses analysis shows that the results are statistically significant and accepted. In Table 5 , the details of the sub-hypotheses and the principals are explained precisely. Please see Table 6 to review items with their mean and standard deviation values. Moreover, Figure 2 represents the structural model.

Examining the hypotheses.

Description of items, mean, and standard deviation.

Structural model.

Discussion and Conclusion

These findings add to our knowledge of how teenage depression is predicted by academic and familial stress, leading to poor academic performance, and they have practical implications for preventative and intervention programs to safeguard adolescents' mental health in the school context. The outcomes imply that extended academic stress positively impacts students' depression levels with a β of 0.293 and a p -value sof 0.003. However, according to Wang et al. ( 5 ), a higher level of academic stress is linked to a larger level of school burnout, which leads to a higher degree of depression. Satinsky et al. ( 105 ) also claimed that university officials and mental health specialists have expressed worry about depression and anxiety among Ph.D. students, and that his research indicated that depression and anxiety are quite common among Ph.D. students. Deb et al. ( 106 ) found the same results and concluded that depression, anxiety, behavioral difficulties, irritability, and other issues are common among students who are under a lot of academic stress. Similarly, Kokou-Kpolou et al. ( 107 ) revealed that depressive symptoms are common among university students in France. They also demonstrate that socioeconomic and demographic characteristics have a role.

However, Wang et al. ( 5 ) asserted that a higher level of academic stress is associated with a higher level of school burnout, which in return, leads to a higher level of depression. Furthermore, Satinsky et al. ( 105 ) also reported that university administrators and mental health clinicians have raised concerns about depression and anxiety and concluded in his research that depression and anxiety are highly prevalent among Ph.D. students. Deb et al. ( 106 ) also reported the same results and concluded that Depression, anxiety, behavioral problems, irritability, etc. are few of the many problems reported in students with high academic stress. Similary, Kokou-Kpolou et al. ( 107 ) confirmed that university students in France have a high prevalence of depressive symptoms. They also confirm that socio-demographic factors and perceived stress play a predictive role in depressive symptoms among university students. As a result, academic stress has spread across all countries, civilizations, and ethnic groups. Academic stress continues to be a serious problem impacting a student's mental health and well-being, according to the findings of this study.

With the β= 0.358 and p = 0.001 values, the data analysis discloses that the family stress (Fam. Strs) has a significant positive effect on the students' depression level (Std. Dep. Lev). Aleksic ( 108 ) observed similar findings and concluded that many and complicated concerns of personal traits, as well as both home and school contexts, are risk factors for teenage depression. Similarly, Wang et al. ( 109 ) indicated that, among the possible risk factors for depression, family relationships need special consideration since elements like parenting styles and family dynamics influence how children grow. Family variables influence the onset, maintenance, and course of juvenile depression, according to another study ( 110 ). Depressed adolescents are more likely than normal teenagers to have bad family and parent–child connections.

Conversely, students' depression level has a significantly negative impact on their academic performance with β and p -values of −0.319 and 0.001. According ( 111 ), anxiety and melancholy have a negative influence on a student's academic performance. Adolescents and young adults suffer from depression, which is a common and dangerous mental illness. It's linked to an increase in family issues, school failure, especially among teenagers, suicide, drug addiction, and absenteeism. While the transition to adulthood is a high-risk period for depression in general ( 5 ), young people starting college may face extra social and intellectual challenges that increase their risk of melancholy, anxiety, and stress ( 112 ). Students' high rates of depression, anxiety, and stress have serious consequences. Not only may psychological morbidity have a negative impact on a student's academic performance and quality of life, but it may also disturb family and institutional life ( 107 ). Therefore, long-term untreated depression, anxiety, or stress can have a negative influence on people's ability to operate and produce, posing a public health risk ( 113 ).

Theoretical Implications

The current study makes various contributions to the existing literature on servant leadership. Firstly, it enriches the limited literature on the role of family and academic stress and their impact on students' depression levels. Although, a few studies have investigated stress and depression and its impact on Students' academic performance ( 14 , 114 ), however, their background i.e., family and institutions are largely ignored.

Secondly, it explains how the depression level impacts students' academic learning, specifically in the Asian developing countries region. Though a substantial body of empirical research has been produced in the last decade on the relationship between students' depression levels and its impact on their academic achievements, however, the studies conducted in the Pakistani context are scarce ( 111 , 115 ). Thus, this study adds further evidence to prior studies conducted in different cultural contexts and validates the assumption that family and academic stress are key sources depression and anxiety among students which can lead toward their low academic grades and their overall performance.

This argument is in line with our proposed theory in the current research i.e., cognitive appraisal theory which was presented in 1966 by psychologist Richard Lazarus. Lazarus's theory is called the appraisal theory of stress, or the transactional theory of stress because the way a person appraises the situation affects how they feel about it and consequently it's going to affect his overall quality of life. In line with the theory, it suggests that events are not good or bad, but the way we think about them is positive or negative, and therefore has an impact on our stress levels.

Practical Implications

According to the findings of this study, high levels of depressive symptoms among college students should be brought to the attention of relevant departments. To prevent college student depression, relevant departments should improve the study and life environment for students, try to reduce the generation of negative life events, provide adequate social support for students, and improve their cognitive and coping capacities to improve their mental qualities.

Stress and depression, on the other hand, may be managed with good therapy, teacher direction, and family support. The outcomes of this study provide an opportunity for academic institutions to address students' psychological well-being and requirements. Emotional well-being support services for students at Pakistan's higher education institutions are lacking in many of these institutions, which place a low priority on the psychological requirements of these students. As a result, initiatives that consistently monitor and enhance kids' mental health are critical. Furthermore, stress-reduction treatments such as biofeedback, yoga, life-skills training, mindfulness meditation, and psychotherapy have been demonstrated to be useful among students. Professionals in the sector would be able to adapt interventions for pupils by understanding the sources from many spheres.

Counseling clinics should be established at colleges to teach students about stress and sadness. Counselors should instill in pupils the importance of positive conduct and decision-making. The administration of the school should work to create a good and safe atmosphere. Furthermore, teachers should assume responsibility for assisting and guiding sad pupils, since this will aid in their learning and performance. Support from family members might also help you get through difficult times.

Furthermore, these findings support the importance of the home environment as a source of depression risk factors among university students, implying that family-based treatments and improvements are critical in reducing depression among university students.

Limitations and Future Research Implications

The current study has a few limitations. The researcher gathered data from the higher education level of university students studying in Islamabad and Rawalpindi institutions. In the future, researchers are required to widen their region and gather information from other cities of Pakistan, for instance, Lahore, Karachi, etc. Another weakness of the study is that it is cross-sectional in nature. We need to do longitudinal research in the future to authoritatively assert the cause-and-effect link between academic and familial stress and their effects on students' academic performance since cross-sectional studies cannot establish significant cause and effect relationships. Finally, the study's relatively small sample size is a significant weakness. Due to time and budget constraints, it appears that the capacity to perform in-depth research of all firms in Pakistan's pharmaceutical business has been limited. Even though the findings are substantial and meaningful, the small sample size is predicted to limit generalizability and statistical power. This problem can be properly solved by increasing the size of the sample by the researchers, in future researches.

Data Availability Statement

Ethics statement.

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing and editing of the original draft, and read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This work was funded by the 2020 Heilongjiang Province Philosophy and Social Science Research Planning Project on Civic and Political Science in Universities (Grant No. 20SZB01). This work is supported by the Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research, and Sport of the Slovak Republic and the Slovak Academy Sciences as part of the research project VEGA 1/0797/20: Quantification of Environmental Burden Impacts of the Slovak Regions on Health, Social and Economic System of the Slovak Republic.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank all persons who directly or indirectly participated in the completion of this manuscript.

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Stress and coping strategies among higher secondary and undergraduate students during COVID-19 pandemic in Nepal

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Institute of Medicine, Tribhuvan University, Maharajgunj, Kathmandu, Nepal

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Institute of Medicine, Tribhuvan University, Maharajgunj, Kathmandu, Nepal, Nepal Health Frontiers, Kathmandu, Nepal

Roles Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Nepal Health Frontiers, Kathmandu, Nepal, Department of Public Health, Section for Environment, Occupation and Health, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark, COBIN Project, Nepal Development Society, Bharatpur, Chitwan, Nepal

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

- Durga Rijal,

- Kiran Paudel,

- Tara Ballav Adhikari,

- Ashok Bhurtyal

- Published: February 15, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001533

- Reader Comments

Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) pandemic has profoundly affected lives around the globe and has caused a psychological impact among students by increasing stress and anxiety. This study evaluated the stress level, sources of stress of students of Nepal and their coping strategies during the pandemic. A cross-sectional web-based study was conducted during the complete lockdown in July 2020 among 615 college students. Stress owing to COVID-19 and the lockdown was assessed using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), and Brief Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced (Brief COPE) was used to evaluate coping strategies. To compare the stress level among participants chi-square test was used. The Student’s t-test was used to compare Brief COPE scores among participants with different characteristics. The majority of study participants were female (53%). The mean PSS score was (±SD) of 20.2±5.5, with 77.2% experiencing moderate and 10.7% experiencing a high-stress level. Moderate to high levels of stress were more common among girls (92.6%) than boys (82.7%) (P = 0.001). However, there was a significant difference in perceived stress levels disaggregated by the students’ age, fields and levels of study, living status (with or away from family), parent’s occupation, and family income. The mean score for coping strategy was the highest for self-distraction (3.3±0.9), whereas it was the lowest for substance use (1.2±0.5). Students with a low level of stress had a higher preference for positive reframing and acceptance, whereas those with moderate to high levels of stress preferred venting. Overall, students experienced high stress during the lockdown imposed as part of governmental efforts to control COVID-19. Therefore, the findings of our study suggest stress management programs and life skills training. Also, further studies are necessary to conduct a longitudinal assessment to analyse the long-term impact of this situation on students’ psychological states.

Citation: Rijal D, Paudel K, Adhikari TB, Bhurtyal A (2023) Stress and coping strategies among higher secondary and undergraduate students during COVID-19 pandemic in Nepal. PLOS Glob Public Health 3(2): e0001533. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001533

Editor: Abhijit Nadkarni, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Faculty of Epidemiology and Population Health, UNITED KINGDOM

Received: October 13, 2021; Accepted: December 24, 2022; Published: February 15, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Rijal et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All data are available in the Supporting information file.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interests.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic profoundly affected lives worldwide, which not only threatened physical health but global public health and social systems also collapsed during the coronavirus outbreak [ 1 ]. Evidence from the previous outbreaks of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003 and H1N1 influenza in 2009 illustrates that the community suffered considerable fear and panic, resulting in a significant psychological impact. A similar scenario was seen during the COVID-19 pandemic [ 2 ]. Higher levels of anxiety, worries, and social avoidance behaviors were confirmed in the general population in many studies conducted during the earlier pandemic of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) [ 1 , 3 ].

The effect of COVID-19 pandemic on global mental health is less studied. The increasing trend of this disease led to a global atmosphere of anxiety and depression due to disrupted travel plans, social isolation, media information overload, and panic buying of necessity goods and restrictions and economic shutdown imposed a complete change to the psychological environment of affected countries [ 4 – 6 ]. The infection has also caused a psychological impact among students by increasing stress and anxiety during the pandemic [ 7 – 9 ]. Studies showed a high prevalence of stress, anxiety, and depression among students during the COVID-19 pandemic as an effect of the disease itself and lockdowns. The reported stressors include delay in academic activities, financial difficulties, prolonged lockdown, overload of COVID-19 related information, home-schooling, fear of COVID-19 infection, and restrictive measures such as quarantine, isolation, and social distancing which caused an impact on psychological well-being [ 1 , 6 , 10 , 11 ].

In Nepal, limited studies have been conducted to assess the psychological impact of COVID-19 among students. However, studies were conducted during the non-pandemic period, which revealed stress as a problem among the students, as 27% were stressed [ 12 ]. Similar to the studies conducted among students of various countries like Spain [ 7 ], China [ 11 ], and Turkey [ 13 ], students of Nepal also showed significant psychological impact during the pandemic [ 14 ]. According to the same study, 66.7% of students had some level of anxiety, with 27.1% having severe anxiety during the pandemic in Nepal [ 14 ].

To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies to assess the psychological effect and coping strategies among students other than medical students during the pandemic in Nepal. Students can make negative assessments of the pandemic and adopt various coping strategies that may affect their health and well-being. Additionally, there is a possibility that stress is a multi-faceted psychosocial experience that can affect different people differently; therefore, in addition to the prevalence of different levels of stress, it’s important to look at how it may be disproportionately impacting different groups of students. Therefore, a timely assessment of students’ mental health status and coping strategies may help reduce future negative consequences. Therefore, this study aimed to assess perceived stress levels, the sources of stress, and the coping strategies adopted by the students during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Study design and participants

A web-based descriptive, cross-sectional study was done in July 2020 during the complete lockdown in Nepal. The study was carried out among higher secondary and university-level undergraduate students. The study population was students in grades 11 and 12 of faculties, science, and management. Likewise, university-level students, only the bachelor-level students doing a four-year course on various subjects were included in the study. In our study, the undergraduate students were primarily in the fields of pure science, management, medical, paramedical, engineering/architecture, arts/humanities, and information technology. Our study was not confined to students of a specific college as we did not select a specific college for recruiting the participants.

To calculate the sample size, the expected proportion of stress of COVID-19 among the students was taken as 28.8% from a similar study conducted in China [ 9 ]. The sample size was calculated using the formula, n = z 2 pq/d 2 , where p = 0.29, q = 0.71, z = 1.96 at 95% confidence interval, and d = 0.05, which is 315. After assuming 10% of the non-response rate, the final calculated sample size was 347. A total of 643 responses were recorded, of which 28 were redundant, and only 615 were eligible for the analysis. Therefore, the sample size was 615.

Study procedure

We followed the non-probability sampling technique, purposive and snowball sampling, and used our personal contact as well as several Facebook pages and groups of college students to invite them for the study. Google forms were disseminated among the students through email and social media platforms. Facebook groups, Facebook chat, and Viber were predominantly used to recruit participants. To limit the response from only the college students, forms were posted in the official Facebook groups of college students such as Nepal Public Health Student’s Society, institution-based Rotaract clubs, Facebook groups of students of other faculties, etc. and it was mentioned strictly that the forms should be filled only by the college students. Out of the total responses, only 16% of the responses came through email and personal invitation, and 84% of responses were from social media groups. Participation was voluntary; only those who ticked “I Agree” in the informed consent form, which was displayed on the front page of the questionnaire, could proceed further. Participants were allowed to fill out the form once, and multiple entries were not allowed.

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Committee of the Institute of Medicine, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal [Registration number: 85/ (6–11) E 2 / 077/078]. Written digital consent was taken from study participants before completing the survey form. The informed consent form displayed on the front page of the form was for participants of age 18 and above. For the participants of age 16 and 17, it was mentioned in the consent form that the participants of this age group should fill up the form as per their parents’ consent.

The online questionnaire contained three main parts. The first part included questions about socio-demographic characteristics, COVID-19, and sources of stress. Sources of stress were assessed by a question that included variables derived from the literature review. The second part was the Perceived stress scale. Perceived stress was assessed using the Perceived stress scale (PSS-10). A PSS is a 10-item questionnaire to measure the respondents’ self-reported stress level by assessing feelings and thoughts during the last month [ 15 ]. However, to focus on the scope of the study and to reflect on perceived stress during the pandemic, “experiences because of COVID-19” was added to each question. The Cronbach’s alpha value reported for this scale was 0.79 [ 16 ]. The PSS-10 consists of six positive items (items 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, and 10) and four negative items (4, 5, 7, and 8). In PSS, each question is rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Never (score 0)”, “Almost never (score 1)”, “Sometimes (score 2)”, “Fairly often (score 3)”, “Very often (score 4)” with a range of 0 to 40 for the total score of the scale. A higher level of stress is indicated by higher scores on this scale which is the score of 0–13 indicates “Mild stress”, 14–26 indicates “Moderate stress” and 27–40 indicates “High stress”. The scores for questions 4, 5, 7, and 8 were reversed, and the scores for perceived stress were calculated by summing the scores for the relevant items.

The third part consisted of the Brief COPE scale [ 17 ]. The original brief-COPE by Carver comprised 14 subscales, including self-distraction, active coping, denial, substance use, use of emotional support, use of instrumental support, behavioral disengagement, venting, positive reframing, planning, humor, acceptance, religion, and self-blame.” It is an abbreviated version of the COPE Inventory consisting of 28 items, two items in every 14 subscales, and each item is rated on a 4-point Likert Scale ranging from “I have not been doing this at all (score 1)”, “A little bit (score 2)”, “A medium amount (score 3)”, “I have been doing this a lot (score 4)”. The mean score of all items in each subscale is used, and a higher number indicates a higher preference for the coping strategies reported by the participants. Only ten dimensions of coping strategies were used.

Data analysis

After completing data collection, responses stored in the web-based database (Google Drive) were downloaded, compiled, edited, and checked for errors in Microsoft Excel. Then the data was exported to Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20 for data cleaning, coding, and analysis. Continuous variables like coping strategies were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD), whereas frequency and percentages were used to present categorical data. The chi-square test was used to assess the association of perceived stress levels among participants with different characteristics. The Student’s t-test for independent samples was used to compare the mean values of coping strategies in relation to studied variables.

Socio-demographic characteristics

Table 1 depicts the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents. Among the 615 respondents, the majority (53.0%) were female. The age ranged from 16 to 29, with a mean age (±SD) of 20.5 (±2.5). More than two-thirds (70.2%) of the respondents were Brahmin/Chhetri. The majority of the respondents (92.7%) were living with their family, and only 9.6% of the respondents disclosed having their family/friends/relatives infected with COVID-19 or in isolation ( Table 1 ).

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001533.t001

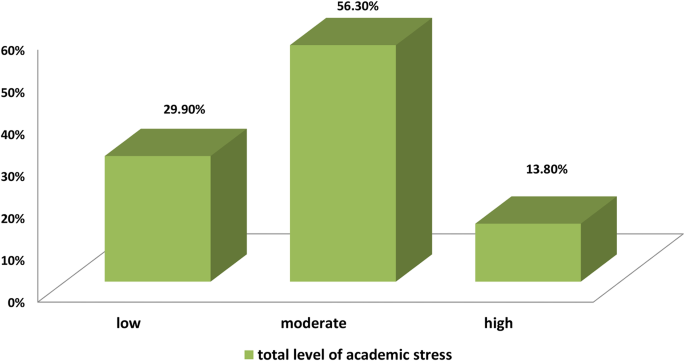

Perceived stress

The majority of the students (77.2%) had a moderate level of perceived stress, whereas 12.0% had low perceived stress, and 10.7% had high perceived stress. The overall mean stress score (±SD) was 20.2 (±5.5). Among the socio-demographic variables, only gender was significantly associated with the level of stress. Male respondents were observed to have significantly less stress than female respondents (p-value = 0.001). Table 2 shows the association of the level of perceived stress with socio-demographic variables.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001533.t002

Sources of stress among students

The most important sources of stress reported by students were the long duration of lockdown (60.7%) and excessive hearing of news related to COVID-19 (50.1%). Out of 12 sources of stress, only one source, i.e., delay in the resumption of teaching/learning or fear of extension of the academic year, was significantly associated with the level of perceived stress.

Coping strategies used by students

Out of the ten coping strategies, only three were significantly associated with perceived stress. Students with a low stress level had a higher preference for positive reframing and acceptance, whereas those with moderate to high levels of stress preferred venting more. ( Table 3 ). Self-distraction was the highest used coping strategy, followed by acceptance, and substance use was the lowest ( Table 4 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001533.t003

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001533.t004

Gender was observed to be one of the main factors where significant differences were observed for all the coping strategies used in the study except positive reframing (p = 0.1) and active coping (p = 0.2) ( Table 4 ).

This study examined perceived stress among college and university students during the COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown period in Nepal. Our study found that the majority of the students (77.2%) had moderate perceived stress, which resembles the findings of other studies from Spain [ 7 ], China [ 11 ], India [ 18 ], the US, and the UK [ 19 ] which reported a high level of mental health problems during the COVID-19 outbreak. Likewise, using the same measurement scale (i.e., PSS-10), in a study among students in Saudi Arabia during the COVID-19 outbreak, more than half of the participants (55%) showed moderate levels of stress, and 30.2% showed high stress [ 20 ]. Another study from Pune, India, reported that 82.6% of the students experienced moderate perceived stress, and a high perceived stress score was seen in 13.35% of the students during the COVID-19 pandemic [ 18 ]. Likewise, university students in southeast Serbia reported a mean perceived stress score of (20.3±7.6) which is similar to our findings (20.2±5.5) [ 21 ].

However, the result of our study contrasted with the findings from Turkey, in which 71.2% reported high perceived stress [ 13 ]. In the previous studies conducted in Nepal during the non-pandemic period, stress was found among 27% of students, 20.9% faced psychological morbidity, and the majority of the students (51%, n = 350) reported moderate to extremely severe levels of stress, anxiety, and depression [ 12 , 22 , 23 ]. In another study conducted during the non-pandemic period in Nepal, 60.4% of the students experienced moderate stress levels, and only 0.6% of the students experienced high-stress levels [ 24 ]. However, in our study, the percentage of students having stress was higher than in studies conducted during a non-pandemic situation in Nepal. Adding to it, the mean perceived stress score of (20.2±5.5) suggests that our participants had relatively high stress compared with established norms for a general population sample aged 18–29 (14.2±6.2) [ 15 ]. Furthermore, the perceived stress results in our study were relatively higher (20.2±5.5) than the results obtained in an earlier pre-COVID-19 survey among the Serbian students (14.9±6.3) [ 21 ]. Likewise, the perceived stress reported by the Malaysian study during the non-pandemic period was found to be relatively lower (46.3%) [ 25 ] than the result of our study, which may indicate that the pandemic might have aggravated the stress among students across the globe.

In this study, only gender was associated with the level of perceived stress. The female students were observed to have a higher mean score of perceived stress (21.0±5.1), similar to the findings from other studies conducted during the pandemic [ 13 , 19 , 20 ] that have shown significant gender differences in the psychological response to the pandemic. Likewise, the study results are in line with the recent studies carried out among the student of Spanish University [ 7 ] and the Saudi Arabian students [ 26 ], which showed significant gender differences. Therefore, high stress levels among females might have been attributed to various factors, including hormonal changes and expression of emotions and thoughts regarding their social situation [ 20 ], and the recent pandemic might have exacerbated this situation. Sociocultural inequity and gender norms, differences in the distribution of resources and restricted control over the economy make females more vulnerable to mental health problems in most of the low-and middle-income countries [ 27 ].

In Nepal, there is a difference in the socialization pattern of men and women [ 28 ]. Women are more likely to be more open about their feelings and admit their stress, whereas men are more reluctant to report psychological duress, which may lead to gender differences in terms of the appraisal process of stressful events [ 29 ]. In addition, women in Nepal have a higher societal expectation of being in caretaking roles, which may be even more stressful during a pandemic. Sometimes, they cannot fulfill the expectation of family members, so women are often abused and victimized [ 30 ]. In addition to economic hardship during the pandemic, a mental health risk for women could have been driven by gender-based violence (GBV) embedded in social norms [ 27 ]. The United Nations identified GBV as one of the areas of the impacts of COVID-19 on women [ 31 ]. During the COVID-19 lockdown in Nepal, several cases of domestic violence against women and girls were reported, which could directly affect their mental health [ 32 ]. Therefore, these gender differences open a path for more gender-specific intervention. The high prevalence of perceived stress and significant gender difference also suggests specific psychological measures prepared to prevent perceived stress and other mental health problems, especially for women.

In one of the studies, age and educational level were significantly associated with stress, where university students had a significantly higher mean score of perceived stress than intermediate and secondary school students. However, no such association was found in our study between perceived stress and age and perceived stress and educational level [ 20 ]. Similarly, in our research, there was no significant association between educational background and the stress level, contrary to other studies. Students in management-related studies seemed to have a higher level of anxiety than medical students during the pandemic [ 33 ]. This might be because students of all the faculties in our study could have been well-informed about the pandemic and the precautionary measures.

Likewise, the parents’ occupation did not affect the level of perceived stress, unlike the findings of the previous study [ 34 ]. In one of the studies conducted among college students in China, anxiety regarding the epidemic was associated with the source of parent income, whether living with parents and whether a relative or an acquaintance was infected with COVID-19, which is not in agreement with the results of our study [ 11 ].

Given the above findings, students considered many factors as sources of stress during the pandemic. More than six out of ten study participants considered the long duration of the lockdown as the major source of stress. It corroborates with the literature suggesting that lockdown is one of the important stressors during COVID-19 and has a considerable psychological impact on the well-being of people [ 6 ]. This might be because, during the lockdown, outdoor activities were hampered. Likewise, half of the students (50.1%) indicated stress induced by news outlets, similar to those found among the US College students. This type of stress may be exacerbated by a large amount of misinformation, including false and fabricated information distributed through news and social media [ 35 ]. Also, studies suggest that people may develop “headline stress disorder” during the modern pandemic, which is characterized by stress to endless reports from the news media [ 36 ].

Similarly, in our study, students considered a delay in the resumption of teaching/learning or fear of extension of the academic year, fear of contracting the virus by family/friends/relatives, financial difficulties, worries of the future like employment, gaining weight, interpersonal conflict with roommate/family members as other important sources of stress which resembles with the recent findings [ 35 , 37 ]. However, our findings related to an overload of the assignment were different from that found in the recent study in which 66.6% considered increased class workload as the source of stress. In contrast, in our study, only 11.1% considered it the source of stress [ 35 ]. This might be because colleges and universities were closed; only limited colleges and universities ran virtual classes. In the study conducted among university students in Pakistan, major distress was related to restricted social meetings with friends (84.7%) and fear of family/friends getting infected (70.9%), but in our study, only 14.1% and 44.6% of university-level undergraduate students considered inability to meet family/friends and fear of family/friends/relatives being infected as the source of stress respectively [ 38 ]. This might be because most of the students were with their family/relatives during the period of lockdown, and the virus may not be present at the community level in their place of residence.

To cope with the stressors, students used various coping strategies in our study. The mean scores for active coping strategies (acceptance, planning, active coping, positive reframing, use of emotional support) were greater than avoidant coping strategies (venting, substance use), as well as religious coping and humor except for self-distraction. A similar result was found in the study conducted among Pakistani students, where all the active coping strategies had higher mean scores [ 38 ]. Our study found that substance use was the least common coping strategy among the students, as in the previous studies. However, the average score of substance use was found to be 1.2± 0.5 in our study, and the average score of substance use was reported as 2.5±1.0 and 2.7±1.4 from the same study conducted in Nepal and Malaysia, respectively, during the non-pandemic period which suggests that the average score of substance use was less during the pandemic period [ 22 , 25 ]. This indicates that substance use as a coping strategy for stress might have decreased during the pandemic as the shops selling these products were closed following the government rule of lockdown.

Similarly, living with parents/family members during the lockdown and getting adequate emotional support might also be a reason for decreased substance use by the students. In our study, students with moderate to high-stress levels preferred venting more than the students who perceived low stress. However, students with a low stress level had a higher preference for positive reframing and acceptance. Mixed use of both the active and the avoidant types of coping strategies might be because, in times of uncontrollable situations and diverse types of stressors, any type of coping might be helpful in reducing stress. In our study, active coping was not associated with stress level; this might be because of the uncertainty and uncontrollability of COVID–related stressors.

Likewise, religious coping was also not associated with the level of stress, which is consistent with the finding of a previous study conducted during the non-pandemic period [ 25 ]. Nevertheless, this result contradicts the recent finding that shows religious coping as the most effective coping strategy to deal with severe stress and practiced by many severely stressed students during the pandemic [ 26 ]. This might be because, in our study, the study population was a younger group of people who tend to adopt other coping measures rather than religious coping. The older students in our study used positive reframing more than the teens, which resembles the previous study’s findings [ 25 ].

Our study found the association of gender with self-distraction, planning, humor, acceptance, and religious coping. Male students used self-distraction, acceptance, and religious coping less than females, and females used humor coping less than males, according to a recent study. However, the result of our study differed in planning; males used planning more than females in our study, which contrasts with the previous study [ 38 ]. In our study, male students used active coping less and substance use more than female students, resembling the previous study’s findings [ 25 ]. In the previous study conducted during the outbreak, the mean score was higher for religious coping among university students. However, the mean score was the highest for self-distraction among undergraduate students in our study, followed by acceptance. In contrast, it was the lowest for substance use, similar to the previous findings [ 38 ]. Furthermore, there might be many reasons behind such findings. One of the reasons might be having many options like watching TV, reading books, using social media, playing online games, attending online classes, etc., as there was a lockdown and low substance use might be because students were living with their family/relatives and there was no access of substance due to lockdown. In another study conducted among undergraduate medical students, commonly used coping strategies were “regular exercise”, “watching online movies and playing online games”, “religious activities,” and “learning to live in a COVID-19 situation and accept it” which resembles active coping, self-distraction, religious coping, and acceptance and these strategies were also, commonly used by the medical students in our study [ 26 ].

Therefore, the findings of our study suggest stress management programs as well as life skills training and mindfulness therapy, which have been validated to reduce stress and anxiety [ 39 , 40 ]. Similarly, regular exercise and good sleep are recommended, which have been found to have mitigating effects on negative emotions without social, medical burden [ 9 , 41 ]. Even though female students presented higher stress levels, providing mental health support systems and promoting physical activity regularly is necessary for all students, which could decrease perceived stress levels. Online training, workshops, and contests for the students from the respective educational institutions can also be conducted to distract them from stressful situations, reduce stress, and protect them from future psychological consequences. Therefore, further studies are necessary to conduct a longitudinal assessment to analyse the long-term impact of this situation on students’ psychological states and to enable more robust evidence on causal links and pathways.

Strengths and limitations

There are certain limitations in this study. First, the study was conducted during the peak time when COVID-19 was spreading rapidly, so the study used self-reported questionnaires, which may have issues with subjectivity and reliability. However, respondents were assured of the anonymity of the data. Similarly, social desirability bias and lack of conscientious response in respondents may limit the accuracy of the present findings. Furthermore, the findings from the self-reported measures of mental health cannot be subjected to direct treatment without using diagnostic tools. However, the self-reported tools are easy and useful for assessing individual perceptions of their illness. The PSS cut-offs are the ones established in the literature and may not be the best way to capture the variation in stress expressed in this sample. Second, the study might not represent the population with no access to the internet. Third, the questionnaire was in English, which might have created a language barrier. Fourth, the study used only ten Brief COPE dimensions and missed other dimensions that the respondents could have manifested. Fifth, the limited sample size and purposive sampling approach findings may not represent the entire student population. Sixth, the study was cross-sectional under an unprecedented situation and had a limitation in determining a causal relationship between factors of interest and perceived stress and evaluating the stress level during the actual pandemic and pre-pandemic period. In addition, there may be an exacerbation of existing psychiatric illness, substance use, etc., so the findings here do not represent the only impact of the disease on mental health. Despite the limitations of this study related to web-based cross-sectional design with self-reported measures, the findings add new evidence regarding stress among students during the COVID-19 pandemic. It could also be a piece of baseline evidence for future work on stress and coping strategies among students in Nepal.