An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Practical Guidance for New Multiple Myeloma Treatment Regimens: A Nursing Perspective

Monica epstein.

a National Cancer Institute, 10 Center Drive Bethesda, Maryland 20814

Candis Morrison

b United States Food and Drug Administration, 10903 New Hampshire Ave, Building 22 Room 2319 Silver Spring Maryland 20993

As is the case for solid tumors, treatment paradigms have shifted from non-specific chemotherapeutic agents towards novel targeted drugs in the treatment of patients with multiple myeloma (MM). Currently, multiple targeted therapies are available to treat patients augmenting the arsenal of modalities which also includes chemotherapy, immunotherapy, radiation therapy, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCST) and chimeric antigen T-cell therapy (CAR-T). These novel, targeted agents have dramatically increased optimism for patients, who may now be treated over many years with successive regimens. As fortunate as we are to have these new therapies available for our patients, this advantage is juxtaposed with the challenges involved with delivering them safely. While each class of agents has demonstrated efficacy, in terms of response rates and survival, they also exert class effects which pose risks for toxicity. In addition, newer generation agents within the classes often have slightly different toxicity profiles than did their predecessors. These factors must be addressed, and their risks mitigated by the multidisciplinary team. This review presents a summary of the evolution of drug develoipent for MM. For each targeted agent, the efficacy data from pivotal trials and highlights of the risks that were demonstrated in trials, as well as during post-marketing surveillance, are presented. Specific risks associated with agents within the classes, that are not shared with all new class members, are described. A table presenting these potential risks, with recommended nursing actions to mitigate toxicity, is provided as a quick reference that nurses may use during the planning, and provision, of patient care.

PR was diagnosed with multiple myeloma (MM) in 1978, at the age of 67, during evaluation for progressive anemia and was noted to have Grade 2 chronic kidney disease and hypercalcemia. This provoked an evaluation for MM. His IgG M-spike was 6.5g/dL and multiple osteolytic lesions were evident on his skeletal survey. Since his disease was advanced, his performance status (PS) and quality of life were rapidly declining. He understood that his prognosis was very poor, though he agreed to treatment with melphalan and prednisone. Mr. R. did not tolerate the chemotherapy, experiencing nausea and anorexia which both contributed to his frailty and rapid decline in PS. It became difficult to maintain his hemoglobin with red blood cell transfusion and erythrocyte stimulating agents were not yet approved. His M-spike had only declined to 5 after three cycles. Since few options were available, he was offered referral to an academic center which was evaluating other alkylating agents as well as vinca alkaloids. However, by this point, he was extremely fatigued and was experiencing severe pain from a thoracic compression fracture and thus incapable of travel. After a short course of palliative radiation to his thoracic spine, he decided to forgo additional chemotherapy and to live his remaining months receiving palliative care exclusively. Addressing his symptoms, while the MM continued to take its course, was his priority. He died five weeks later at home. Unfortunately, this was a common scenario at the time.

INTRODUCTION

As this case study illustrates, patients with MM enter therapy with complications of their disease. The acronym CRAB has been used to describe MM’s constellation of end-organ effects; hypercalcemia (C), renal effects (R), anemia (A), and bone lesions (B). In addition, since MM affects cells involved in humoral immunity, infections pose a significant risk in terms of morbidity and mortality. Patient comorbidities affect tolerance of therapy and may also be contraindications to certain agents. When we consider the multitude of potential combinations of agents that may be used during multiple lines of therapy, we must address each agent in terms of its potential for “off-target” toxicities, the need for prophylaxis for thrombolic events and opportunistic infections, recommended dose modifications for comorbid organ dysfunction, and important drug-drug interactions (DDI). Addressing these considerations may decrease unnecessary treatment-related morbidity and mortality for patients with MM. In this Practical Guidance, the authors will provide a brief history highlighting the rapidity of MM drug development, present a review of the classes of targeted agents, specific agents within each class, and agent-specific toxicity risks. A reference table containing risk mitigation interventions is included.

TRAJECTORY OF DRUG DEVELOPMENT FOR MULTIPLE MYELOMA

Corticosteroids, alkylating agents, and radiation have been available to patients with MM since the 1960’s. Prior to the introduction of alkylating agents, the median survival for patients with MM was less than one year. [ 1 ] While dexamethasone remains the cornerstone of many regimens, and as a single agent is successful in temporarily depleting lymphocytes including monoclonal plasma cells by blocking IL-6 and thus plasma cell differentiation [ 2 ], its effect is short-lived. Chemotherapy options were generally limited to alkylating agents such as cyclophosphamide, and later melphalan, which act by inducing irreversible damage to DNA helix strands. [ 3 ] Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program (SEER) data demonstrated that median survival for patients with MM between 1973 and 2003 was only 24 months. [ 4 ] Radiation was successful in treating lytic lesions, though rarely impacted survival.

The introduction of high dose chemotherapy with autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (autoHSCT) rescue in the 1980’s, achieved an improvement in survival [ 5 ]. Allogeneic HSCT was more successful in eradicating disease, though associated with higher morbidity and mortality, however, it was not available to many patients, particularly those at advanced age or with significant comorbidities. Few had suitable donors for an allogeneic transplant. Graft-versus host disease provoked its own morbidity, and risk of death, via infection and organ damage. With 69 being the median age of patients diagnosed with MM, a shift away from high dose chemotherapy with ASCT, was direly needed [ 6 , 7 ].

Widespread benefits for all patients with MM were first seen with the introduction of targeted agents to the US market in 2003, initiating the trajectory that improved survival statistics. The first Immunomodulatory drug (IMiD) was thalidomide, though it was not initially approved United States due to its teratogenic effects that affected over 10,000 children. [ 8 ] Though the exact mechanism of action of IMiDs was elusive, immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, and antiangiogenic features were hypothesized [ 9 ]. Thalidomide was later reintroduced as the first in the class of IMiDs, though not approved until 2006 for MM. Lenalidomide (Revlimid®) trials were initiated in the late 1990s, with approval in 2006. Median overall survival (OS) for patients diagnosed between 1971 and 1996, was 29.9 months.[ 10 ]

The introduction of bortezomib (Velcade®), developed in the early 2000’s and approved in 2003 as the first proteasome inhibitor (PI) [ 11 ] and lenalidomide the second IMiD approved in 2006, dramatically changed therapeutic paradigms. Combined with corticosteroids, bortezomib and lenalidomide favorably impacted overall response rates (ORRs) and overall survivals (OS), rapidly becoming the standard of care, and in the case of lenalidomide providing an oral alternative to infusion therapy and HSCST.[ 6 ] Both bortezomib and lenalidomide were initially used with dexamethasone in doublet regimens and when eventually combined into a triplet regimen, Velcade®, Revlimid®, and dexamethasone (VRd), had a major impact. OS for patients diagnosed between 1996 and 2006 rose to a median of 44.8 months [ 10 ], and those diagnosed between 2006 −2010 experienced an average survival of 6.1 years, a 31% increase. [ 12 ]

The past five years have proven to be the most prolific in terms of advances in the therapy of MM. Panobinostat (Farydak®), a histone deacetylase inhibitor, garnered an approval in 2015 but was later withdrawn, while ixazomib (Ninlaro®) became the first oral PI. Elotuzumab (Empliciti®), which targets SLAM 7, was the first monoclonal antibody approved for patients with MM. Daratumumab (Dazalex®), the first anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody (mAb), was approved initially in 2016 for use in refractory/relapsed multiple myeloma (RRMM), and then moved quickly into earlier lines of therapy including newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma (NDMM). Antibodies are generally used in combination regimens although they may be useful as single agents in the event of tolerability issues with other agents.

In 2019, a new drug class, the nuclear export inhibitor Selinexor (Xpovio®), was added after demonstrating efficacy in patients whose disease was “triple refractory”. Its novel mechanism of action, blocking exportin 1 (XPO1), is postulated to lead to nuclear accumulation of tumor suppressor proteins and reduced oncoprotein messenger RNA translation ultimately inducing apoptosis of the malignant cells.[ 13 ] Isatuximab (Sarclisa®), a second anti CD-38 antibody was approved in 2020, as was belantamab mafoditin (Blenrep®), the first therapeutic targeting B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), expanding treatment options further. Belantamab mafoditin, an antibody-drug conjugate (ADC), attaches to BCMA expressed on MM cells, inducing apoptosis of the MM cells.[ 14 ]

Additional drugs are under investigation and are anticipated to change therapeutic paradigms of MM even further. CAR-T cell therapies that target receptors such as BCMA or CD229 are currently being studied in MM and have been successful in a subset of patients. Bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs) are a new class of immunotherapy drugs under investigation that improve patient’s immune response by redirecting T-cells to cancer cells and are thought to have potential benefits in the treatment of MM. [ 15 ]

Thus, the changing landscape of MM treatment has dramatically improved survival for patients, with the development of more than 11 new agents in the past two decades and 7 in the past 5 years. Currently, there are multiple options available for patients with MM, highlighting the rapidity of change in treatment for a disease that formerly had few, to no options.

REVIEW OF AGENTS USED IN THE TREATMENT OF PATIENTS WITH MULTIPLE MYELOMA

Immunomodulatory drugs (imids, thalidomide analogs), class effects.

Immunomodulatory drugs have multiple properties that contribute to their anti-myeloma effects including anti-proliferative, anti-inflammatory, T-cell co-stimulatory, and anti-angiogenic properties.[ 16 ] It is not clear as to how, and to what degree, each of these actions contribute to the anti-tumor effect of this class of agents. Cellular targets, including suppression of macrophage driven prostaglandin synthesis and modulation of the production of interleukin-1 and 2 by monocytes, as well as increased numbers of natural killer cells are involved. [ 9 ]

As a class, IMiDs are associated with development of venous thromboembolic events (VTEs) and require concomitant VTE prophylaxis with antiplatelet drugs or anticoagulants. There is a boxed warning on the label for risk of thromboembolism and patients are at greater risk for ischemic heart disease and strokes and must be monitored closely.

IMiDs are associated with the greatest known risk for embryo-fetal toxicities and have mandatory REMS (Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy) requirements. Revlimid® (lenalidomide) and Pomalyst® (pomalidomide) have additional warnings regarding development of second primary malignancies. In an analysis of 11 clinical trials that included 3,848 patients enrolled on lenalidomide containing regimens, the overall incidence of second primary malignancies was 3.62 per 100 patient-years. [ 17 ]

In 2017, trials administering the IMiDs lenalidomide or pomalidomide, and dexamethasone with the PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab (Keytruda®) were put on hold due to an increased risk of death in the PD-1 containing arms. This led to concern regarding combination of IMiDs and checkpoint inhibitors, and over 30 trials were closed. Deaths included those related to immune-mediated events, infections, and organ failure. [ 18 ]

Thalidomide (Thalomid®)

Thalomid® was approved in 2006 for treatment of patients with NDMM in combination with dexamethasone. The initial US approval of Thalomid® was based on two RCTs comparing thalidomide plus dexamethasone (Td), to dexamethasone plus placebo in newly diagnosed MM patients. Data is presented in Table 1 .

Agents approved in the United States.

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; DOR, duration of response; MM, multiple myeloma; NDMM, newly diagnosed multiple myeloma; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression free survival; RCT, randomized control trial; RRMM, relapsed refractory multiple myeloma; TTP, time to progression.

The most common non-hematologic toxicities, occurring in 20% or more of patients receiving thalidomide for MM are_fatigue, hypocalcemia, edema, constipation, neuropathy-sensory, dyspnea, muscle weakness, rash/desquamation, confusion, anorexia, nausea, anxiety/agitation, asthenia, tremor, fever, weight loss, thrombosis/embolism, neuropathy-motor, weight gain, dizziness, and dry skin. [ 19 ]

Compared to the other IMiDs, thalidomide has greater impact on patient’s quality of life [QOL] due to development of peripheral neuropathy [ 20 ] and sedation [ 19 ]. Neurological damage can also be associated with disease but more often associated with MM treatment. The FDA recommends performing sensory nerve amplitude potential studies (SNAPs) at baseline and every 6 months to assess the impact, and whether dose reductions or a delay in treatment is necessary ( Table 2 ). The second generation IMiDs have shown a decrease in the incidence of neurotoxicity and may be a better option for patients presenting with neuropathy at diagnosis [ 21 ]. Since the development of lenalidomide, thalidomide is less frequently used in the US, although it remains a major therapeutic for MM in Asia, South America, and Europe. [ 22 ]

Considerations for Use.

Abbreviations: DDI, drug-drug interaction; REMS, risk evaluation and mitigation strategies; VTE, venous thromboembolism

Due to the drowsiness/somnolence that can occur with thalidomide as well as the risk for dizziness and bradycardia, patients must be educated about the risk of driving a vehicle and alerted to the possibility that taking additional medications that may potentiate these side effects. If bradycardia is severe, dose reduction or discontinuation may be required. Patients who have a history of, or are at risk for, seizures must be monitored closely for a possible increase in seizure activity. [ 19 ]

Lenalidomide (Revlimid®)

Revlimid® is an IMiD, which received its first MM approval in 2006, for use (with dexamethasone) in patients who had received one, or more, prior therapies. Approval was based on pooled data from two phase 3 RCTs, MM-09 and MM-10 (see Table 1 ). In 2015, the indication expanded to include use with dexamethasone for the treatment of patients not eligible for auto HSCST (see Table 1 ).

Neutropenia (27.7% vs 4.6%) and thrombocytopenia (17.1% vs 9.9%) are the most frequent hematologic toxicities that occur with lenalidomide. Significant neutropenia and thrombocytopenia are listed as boxed warnings on the Revlimid® label, and it is recommended to perform a CBC weekly for the first 2 cycles of treatment, and then monthly. The most common non-hematologic toxicities occurring in 20%, or more, patients included fatigue/asthenia (62%), constipation (39%), muscle cramps (30 %), diarrhea (29.2%), pneumonia and upper respiratory tract infections (24.9%), pyrexia (23.1%), headache (21.4%), dizziness 21%) and dyspnea (20.2%). VTE occurred in 12%, indicating a need for prophylaxis. Dose modification guidelines are included in the original label for thrombocytopenia, neutropenia and later for renal insufficiency. [ 23 ]

Pomalidomide (Pomalyst®)

Pomalyst® was first approved in 2013 for use in combination with dexamethasone for patients with whose disease had progressed after receiving at least two prior therapies, including lenalidomide and a PI. Initial approval of was based on two randomized phase 2 trials, in patients with RRMM who had received therapy consistent with that stipulated in the indication (see Table 1 ). [ 24 ]

The most common non-hematologic toxicities reported in greater than 30%, or more, of patients included fatigue and asthenia, constipation, nausea, diarrhea, dyspnea, upper respiratory tract infections, back pain, and pyrexia. [ 25 ]

Proteasome inhibitors (PIs)

Proteasomes are multienzyme complexes that provide the main pathway for intracellular protein degradation and contribute to the maintenance of homeostasis, promote angiogenesis, and stabilize proapoptotic members of the BCL-2 family.[ 26 ] Numerous proteins are degraded by the proteasome, therefore multiple cellular processes are affected by inhibition of the proteasome. The effect of PIs on MM cells is multifactorial and includes inhibition of the proteasome leading to the accumulation of cyclin- or CDK inhibitors and tumor suppressor proteins such as TP53, as well as the blockade of NFκB transcription and inhibition of clearance of misfolded proteins. [ 11 ]

Risks of PIs include infection, neuropathy, and gastrointestinal toxicities, and these require dose adjustments in patients with organ dysfunction. They all require concomitant herpes zoster prophylaxis. 27, 28, 29] A phase 3 RCT comparing melphalan and prednisone (MP) with or without bortezomib, reported a 13% incidence of zoster infections in patients receiving bortezomib without prophylaxis, compared to 3% with prophylaxis. [ 30 ] Antiviral prophylaxis is now recommended for all patients who are seropositive for HSV and/or VZV patients to prevent this complication.

A risk for thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA), including thrombocytopenic purpura/hemolytic uremic syndrome (TTP/HUS), has been associated with the use of PIs. Patients who have signs and symptoms of TMA, including fever, hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia or reduced renal function must discontinue PIs until evaluated. [ 31 ]

Bortezomib (Velcade®)

Velcade® was the first-in-class PI, receiving an accelerated approval in 2003 based on the results of the single arm SUMMIT trial ( Table 1 ). The most common toxicities were fatigue, malaise, and weakness, occurring in 65%, nausea (64%), diarrhea (51%), with anorexia, constipation, and thrombocytopenia in 43%. [ 32 ]

Full approval for the use of Velcade® in the relapsed setting as single agent was based on a Phase 2 RCT comparing bortezomib to dexamethasone in 669 patients who had received 1-3 prior therapies ( Table 1 ). Assessment of safety in the bortezomib group demonstrated an incidence of; diarrhea of 57% versus 21%, nausea 57% versus 14%, constipation 42% versus 32%, and peripheral neuropathy 36% versus 9%. Thrombocytopenia was the most common hematologic toxicity affecting 35% versus 11%, followed by anemia in 26% versus 22%. [ 28 ]

Approval for use in treatment naïve patients was based on the VISTA trial which randomized 682 patients ( Table 1 ). Toxicities higher in the bortezomib containing arm included thrombocytopenia in 52% versus 47%, and neutropenia in 49% versus 46%, however anemia was higher in the melphalan/prednisone control group (55% versus 43%).[ 30 ]

Bortezomib was initially available in an intravenous (IV) formulation, though it was later demonstrated to have equivalent efficacy, with less neuropathy, if administered subcutaneously (SC). SC approval was based on results of a phase 3 non-inferiority study comparing the two formulations ( Table 1 ). Grade 3 or higher peripheral neuropathy was significantly reduced in the SC arm (16% to 6%).[ 33 ]

Bortezomib can be safely used in patients with renal dysfunction and does not require reduced dosing. However, since it is metabolized by the liver, its exposure is increased in patients with moderate to severe hepatic impairment, and dose reduction should be considered in patients with serum bilirubin ≥1.5 times the upper limit of normal. [ 28 ]

Though bortezomib was administered twice weekly in clinical trials once weekly administration has been shown to maintain efficacy while decreasing the incidence of peripheral neuropathy. Neuropathy is more severe in patients that have pre-existing neuropathic conditions, and those who have received prior neurotoxic therapy [ 34 ]. The USPI contains a dose adjustment algorithm for neuropathy. [ 28 ]

Carfilzomib (Kyprolis®)

Kyprolis® was first approved in 2012 for the treatment of patients with RRMM who had received at least 2 prior therapies (including bortezomib and an IMiD) and were deemed refractory to their last therapy ( Table 1 ). The most frequently reported AEs were hematologic. [ 35 ]

The multicenter phase 3 trial (ASPIRE) enrolled 792 patients with RRMM who had received one to three prior therapies (see Table 1 ). Improved QOL, measured by the QLQ-C30 Global Health Status and Quality of Life Scales, was demonstrated. [ 36 ]

Compared to bortezomib, carfilzomib is associated with a decreased incidence and severity of neuropathy however there is increased risk of hypertension and heart failure (seen in early trials). An analysis of 526 patients in four trials demonstrated a 22% incidence, including events of heart failure of grade 3 or higher, pulmonary edema, and decreased ejection fraction [ 37 ]. A prospective cohort that used intensive screening for cardiotoxicity reported signs in approximately 50% of patients. [ 38 ]

Other common carfilzomib toxicities include fatigue, fever, dyspnea, nausea, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. In addition, VTE, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, and progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy have occurred. [ 27 ]

The Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center published guidelines for minimizing cardiotoxicity with carfilzomib therapy. A comprehensive evaluation of comorbidities that may contribute to cardiotoxicity (hypertension, arrhythmias, heart failure, coronary artery or valvular disease, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and renal insufficiency) should be conducted. If at high risk, patients should undergo transthoracic echocardiogram to assess left ventricular function (LVEF), in addition to an electrocardiogram (EKG). Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) at baseline is also recommended. Hypertension should be managed aggressively. A pretreatment cardiology consultation should be considered. Dosing and IV fluid guidelines are presented in Table 1 .[ 39 ]

Ixazomib (Ninlaro®)

Ninlaro® is the first orally administered PI. It was approved in 2015 in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone for the treatment of patients with RRMM, who have received at least one prior therapy. Approval of ixazomib was based on results of the TOURMALINE-MM1 ( Table 1 ).[ 40 ]

Monoclonal Antibodies

Daratumumab and isatuximab are both CD38-directed cytolytic antibodies that bind to the antigen on the surface of the myeloma cell, induce apoptosis, and activate immune effector mechanisms including antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC), antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis and complement dependent cytotoxicity. Antibody binding can also activate NK cells and suppress CD38-positive T-regulatory cells. [ 41 ] Elotuzumab targets SLAMF7 (signaling lymphocytic activation molecule F7). Highly expressed on myeloma and NK cells, its mechanism of action is multifactorial and includes stabilization by elotuzumab and its F(ab’)2 fragment of the interaction between SLAMF7 on NK cells with MM cells resulting in enhanced killing of MM cells. [ 42 ]

The monoclonal antibodies, daratumumab, elotuzumab, and isatuximab, are associated with infusion related reactions (IRRs), and require premedication to minimize this risk. Dexamethasone, acetaminophen, histamine (H2) blockers and diphenhydramine (H1 blocker), (or equivalents) are recommended. Cytopenias, infection, and blood banking issues are additional considerations. Patients are at high risk for reactivation of varicella-zoster and/or herpes simplex. Prophylactic antivirals are strongly recommended. Elotuzumab and isatuximab are associated with increased risk of SPMs.

Blood banking issues may be problematic with the use of daratumumab and isatuximab as they can interfere with red blood cell antibody screening and cross-matching. A type and screen should be performed prior to therapy. The blood bank should be informed that the patient has received daratumumab or isatuximab. This has not been an issue with elotuzumab therapy.

Interference with serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation occurs and may interfere with these assays in monitoring the M-protein and thus impact the ability to determine complete response. [ 43 , 44 , 45 ]

Daratumumab (Darzelex®)

Darzelex® was originally approved as a monotherapy in 2015 for patients with RRMM and is now approved in multiple different combinations for RRMM and NDMM ( Table 1 ).

Patients receiving daratumumab receive post-infusion corticosteroids to decrease risk/severity of delayed reactions. Patients with a history of asthma, or other obstructive lung disease, may require inhaled steroids or bronchodilators. The most common non-hematologic adverse reactions reported in greater than 20% of patients were upper respiratory infections, IRRs, diarrhea, constipation, nausea, peripheral neuropathy, fatigue, peripheral edema, cough, pyrexia, dyspnea, and asthenia. [ 43 ]

Subcutaneous daratumumab (daratumumab-hyaluronidase) has been shown to have similar efficacy, shorter administration time, and lower rates of IRRs. [ 46 ] Patients require monitoring post-injection, for up to six hours, for the first two to three doses. At home, patients should use acetaminophen and diphenhydramine for any symptoms of delayed IRR.

Elotuzumab (Emplicity®)

The target for elotuzumab is SLAMF7, a glycoprotein highly specific to plasma cells. Though it demonstrated only modest activity as a single agent, it has responses in more than 80% when combined with lenalidomide and dexamethasone, likely due to the synergism of immune-mediated activity with the IMiD. Elotuzumab is thought to modify plasma cells making them vulnerable to targeting by the immune cells. [ 47 ]

Emplicity® was approved in 2015 in combination with Revlimid® and dexamethasone (ERd) for patients with RRMM based on results of the ELOQUENT-2 trial [ 48 ] ( Table 1 ). The triplet therapy has been associated with hepatotoxicity and SPMs. Hepatic enzymes should be monitored closely, and drug held in the event of grade 3, or higher, events. [ 44 ] In this trial, elotuzumab was administered IV weekly for the first two cycles, followed by every other week thereafter. Patients were premedicated for IRRs (occurring in 10% of all patients, with 70% of IRRs occurring with the first infusion) and anticoagulation during therapy for the potential of TTE with lenalidomide. There was an increased risk of severe adverse events in the elotuzumab arm including opportunistic infection, herpes zoster, and a higher rate of SPMs. [ 44 ] Some ascribe the higher risks to the fact patients remained on the triplet arm longer. [ 48 ]

Isatuximab (Sarclisa®)

Sarclisa® was approved in 2020 to be combined with pomalidomide and dexamethasone, for the treatment of adult patients with MM who have received at least 2 prior therapies including lenalidomide and a PI, based on results from the ICARIA-MM trial ( Table 1 ). IRRs occurred in 38% of patients. There were also increased incidences of upper respiratory tract infections (28% versus 17%), and diarrhea (26% versus 20%). [ 49 ] The antibody should be permanently discontinued for grade 3 and higher IRRs. Neutropenia may require dose delays and colony stimulating factor to help prevent infection. IMWG guidelines recommend monitoring for SPMs. [ 45 ]

Histone deacetylase inhibitor [HDACi]

Panobinostat (farydak®).

Deacetylases are enzymes that remove acetyl groups from various proteins and are overexpressed in MM. Panobinostat, an epigenetic modulator, is a pan-deacetylase inhibitor, that targets class I and II histone deacetylase enzymes, components of the aggresome pathway, a target in MM cells, as is the proteasome pathway. [ 50 ] Since MM cells overproduce misfolded proteins, they rely on both pathways for survival. While lacking notable single agent activity, Farydak is synergistic with bortezomib and dexamethasone, in effectively blocking both pathways. [ 51 ]

Originally granted accelerated approval in the United States in 2015 for the treatment of patients with RRMM who had received at least two prior regimens including both bortezomib, and an IMiD, Farydak® was voluntarily withdrawn from the U.S. market at the end of 2021, although it remains available in other markets where approval had been granted. The accelerated approval had been based on data from PANORAMA 1, a multicenter, phase-3 trial, that enrolled 768 patients (see Table 1 ). The most common grade 3/4 toxicities were thrombocytopenia (67% versus 41%), diarrhea (25% versus 8%), asthenia or fatigue (24% versus 12%), and peripheral neuropathy (18% vs 55%). [ 51 ]

With the use of the IV formulation in PANORAMA 1, panobinostat was associated with a prolonged QT interval, and ischemic cardiac events (San Miguel, 2014). An oral formulation with less effect on QT than was seen in the registrational trial became available, however, QT prolongation remained problematic at high doses. [ 52 ] Gastrointestinal toxicities are the most frequent non-hematologic toxicities observed with the use of panobinostat. Diarrhea and neuropathy are overlapping toxicities with bortezomib in the regimen. [ 51 ] When used as a single agent, only 2.6% of patients reported grade 3 or greater diarrhea. [ 53 ]

The USPI for panobinostat had a boxed warning, due to ischemic cardiac events, severe arrythmias and severe diarrhea. It was recommended that its use be restricted to patients less than 65 years of age, with good performance status, who have either not been exposed to a proteasome inhibitor or have been exposed and are not refractory. Non-hematologic laboratory abnormalities that occurred in at least 40% of patients were hypophosphatemia, hypokalemia, hyponatremia, and increased serum creatinine. [ 54 ] Use of antiemetics to combat nausea are indicated along with dose modifications as necessary. If diarrhea reaches grade 4 in severity, panobinostat should be discontinued. [ 55 ]

Nuclear Export Inhibitor

Selinexor (xpovio®).

Xpovio® received FDA accelerated approval in 2019 for the treatment of patients with RRMM who have received at least four prior therapies and have disease refractory to at least two proteasome inhibitors, at least two immunomodulatory agents, and an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody [ 56 ]. It is a nuclear export inhibitor that induces apoptosis through inhibition of exportin 1 (XPO1). XPO1 is overexpressed on MM cells, allows nuclear retention of tumor suppressor proteins, and is associated with shorter patient survival and increased bone disease. Inhibiting nuclear export induces apoptosis in malignant cells. [ 57 ]

Approval was based on results of the STORM trial, a multicenter, phase 2 study that enrolled 122 patients with RRMM ( Table 1 ). The most common AEs were thrombocytopenia (73%), fatigue (73%) nausea (72%), and anemia (67%). Hyponatremia was seen in 37% of patients and neurologic side effects, such as mental status changes and dizziness, were seen in 17% and 15%, respectively. SAEs including pneumonia (11%) and sepsis (9%) also occurred.[ 13 ]

Risk mitigation strategies include dose interruptions, thrombopoietin-receptor agonists, and management of neutropenia. Prophylactic antiemetics and close monitoring of electrolytes and hydration status is recommended.

BCMA Antibody-Drug Conjugate

Belantamab mafodotin (blenrep®).

Blenrep® was approved in 2020 for the treatment of patients with multiply relapsed MM after at least four prior therapies including an anti-CD 38 monoclonal antibody, a PI, and an immunomodulatory agent. Belantamab mafodotin is an antibody-drug-conjugate (ADC) wherein the antibody component is directed against B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA) a protein expressed on MM cells, as well as on normal B lymphocytes. BCMA’s normal function is to promote plasma cell growth and survival. The antibody is conjugated to the small molecule auristatin, a microtubule agent, that when released into the cell disrupts the microtubule network. leading to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. [ 58 ]

Approval of Blenrep® was based on the DREAMM 1 and 2 trials that enrolled patients with RRMM who had received an IMiD, a PI and an anti-CD38 antibody in at least three prior lines of therapy (see Table 1 ). Safety issues included IRRs (29%), cytopenias, and the unexpected toxicity of corneal events seen in 69% of patients. The latter included blurry vision, photophobia, dry eyes, and loss of acuity. [ 59 ] Keratopathy occurred in 27% of patients. Thrombocytopenia is the major hematologic toxicity with belantamab mafodotin and CBCs are necessary as baseline, then routinely, and as clinically indicated. Other toxicities observed in 5% of patients, or higher, include creatinine increases and increase of gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT).[ 60 ]

There is a boxed warning on the Blenrep® label for ocular toxicity and the drug is only available through a REMS program. When eye toxicity occurs, the use of lubricating agents such as artificial tears and dose delays and/or reductions are mitigating measures to enact as soon as symptoms are noted. Routine ophthalmologic examinations are required (baseline, prior to each dose, and at onset of any new ocular symptoms) to assess for asymptomatic corneal lesions. [ 60 ]

Belantamab mafodotin is associated with IRRs. Cytopenias are common as seen with other chemotherapeutics that target microtubules. [ 59 ] Patients must be monitored for infusion reactions, and the dose may need to be reduced, or the drug discontinued, if reactions are severe.

SUPPORTIVE CARE AND RISK MITIGATION MEASURES

Underlying disease related symptoms.

Compared to patients with other hematologic malignancies, patients with MM experience more physical symptoms, and a poorer quality of life (QoL) [ 61 ]. This is often due to the end- organ damage evident at diagnosis characterized in the acronym CRAB (hypercalcemia, renal dysfunction, anemia, and bone lesions), and may be worsened by drug-related toxicity. For example, up to 25% of patients with MM have some degree of renal impairment at diagnosis, and 60% will experience it during the disease. This contributes to anemia and fatigue and engenders increased complexity when renally-cleared agents are used. Up to 90% have lytic lesions at diagnosis [ 62 ] which contributes to anemia, pain, fatigue and poorer QoL. Infection is a major threat, as patients with MM come with altered immune function due to suppression of healthy immunoglobulins. Pain is a major concern for patients and must be controlled to a tolerable level, using agents with safe risk profiles that align with the patient’s comorbidities while avoiding potential drug-drug interactions (DDI). If not addressed, QoL suffers, as may adherence to anti-MM regimens. Analgesic regimens that include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may worsen renal function and increase risk of gastrointestinal symptoms, as well as bleeding. Non-analgesic pain relief measures should be utilized as adjuncts whenever possible including, though not limited to massage, acupuncture, hypnosis, and meditation.

It is frequently difficult to determine whether symptoms are disease-related or are related to toxicities of therapy. In addition, the fact that multiple drugs are generally in use simultaneously, makes is difficult to attribute a given toxicity to a specific agent. It is therefore of paramount importance to avoid early complications that may compromise therapeutic outcome. Hematologic toxicities are common with the use of most of the targeted agents [ 22 ] therefore risk of anemia and infection is common. Patients should additionally be monitored for worsening renal function, peripheral neuropathy, infection, and thromboembolic events (TEEs). Table 1 is provided to present risks and mitigation measures to implement during care for specific class and agent effects. This section addresses the risks proposed by the effects of MM on end-organs, irrespective of therapy used.

Renal Impairment

Renal impairment is one of the most common clinical effects of MM. Most patients will develop renal impairment during their disease, restricting use of some targeted therapies for MM including IMiDs and agents used to prevent skeletal-related events (SREs), such as bisphosphonates. In addition, due to the average of 69 years at diagnosis, some degree of renal insufficiency is likely present at diagnosis.

Renal impairment is generally multifactorial. Disease related renal impairment is due to excessive production of monoclonal light chains leading to myeloma cast nephropathy with, or without, hypercalcemia. It may also be iatrogenic due to therapies or agents that are associated with renal toxicity including IMiDs, NSAIDs, or contrast media used with CT scans. Deterioration of renal function negatively affects OS and QoL Median OS has been reported at 112 months for patients with normal renal function, and 56 months for those who recovered renal function after acute renal injury [ 63 ] highlighting the importance of prevention.

It has been estimated that 97% of patients will experience anemia, defined as hemoglobin of 12 g/dL or less, at some time during their disease and over two-thirds of patients with MM will present already anemic. [ 64 ] Treatment of anemia is important, as it negatively impacts QoL and cardiovascular function. However, correction must be done cautiously, as not to overshoot and create complications related to cardiovascular, and thromboembolic events. The etiology of the anemia is an important consideration and as with other non-cancer patients, a search for other etiologies is necessary. [ 65 ]

When related to underlying MM, several etiologies have been identified, including anemia of chronic disease and/or chronic renal disease, with inadequate erythropoietin (EPO) production. This is related to release of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) which are capable of suppressing erythropoiesis. Anemia may also be the result of the packing of the bone marrow with MM cells, leading to marrow failure and anemia. [ 66 ] In this case, treatment of the MM will improve the anemia. Coagulation defects may lead to iron deficiency through bleeding. Nutritional deficiencies, such as vitamin B12 and folate may occur from inadequate diet or absorption and should be expeditiously corrected [ 65 ].

In addition to its effect on QoL, anemia has a negative impact on the cardiovascular system. It has been estimated that many patients with MM over 70 years of age have pre-existing ischemic heart disease. [ 67 ] Anemia may also aggravate, or induce, hypoxia and has been shown to be a negative prognosticator for patients with MM. [ 65 ]

Symptomatic patients, and patients with cardiovascular compromise, are generally treated with red blood cell transfusions. These correct the symptoms rapidly, however transfusions have been associated with complications including immediate reactions, hypervolemia, iron overload transmission of viruses, and immune tolerance. [ 68 ] Transfusions must be provided with extreme caution in patients with high paraprotein levels as they exacerbate hyperviscosity. [ 69 ]

Since renal insufficiency is a consequence of MM, patients may exhibit low EPO levels. Exogenous EPO became an attractive alternative to RBC transfusion and was successful in raising hemoglobin levels and decreasing symptoms. Epogen (Procrit) was initially approved in 1989 for use in patients with chronic kidney disease. It stimulates erythropoietin by the same mechanism as does the endogenous hormone. However, three randomized trials, the Normal Hematocrit Study (NHS) [ 70 ], Correction of Anemia with Epoetin Alfa in Chronic Kidney Disease (CHOIR) [ 71 ] and the Trial of Darbepoetin Alfa in Type 2 Diabetes and CKD (TREAT) [ 72 ], revealed that patients with higher hemoglobin targets, experienced worse cardiovascular outcomes and in each trial, the potential benefit of ESA therapy was associated with an unfavorable benefit-risk profile. In 2008, Katodritou et al., retrospectively evaluated data including 323 patients with MM and demonstrated that use of erythrocyte stimulating factors was associated with decreased median progression free survival (PFS) to 14 months compared to 30 months in patients who did not receive them. In addition to increased risk for death, serious adverse cardiovascular reactions and stroke were seen with hemoglobin targets levels of greater than 11 g/dL. [ 73 ]

Based on these findings, and those seen in patients with solid tumors, the FDA issued a REMs requirement for ESAs in 2010, the A ssisting P roviders and Cancer P atients with R isk I nformation for the S afe use of ESAs (ESA Apprise) Oncology Program [ 74 ] which was later removed in 2017. The removal decision was based on the results of surveyed prescribers demonstrating acceptable knowledge of product risks-benefit profile and awareness of the need to counsel patients regarding the risks. In addition, drug utilization data indicated that ESA prescribing was consistent with the intended use as a treatment alternative to RBC transfusion in appropriately selected patients. [ 75 ]

If concomitant use of ESAs is required, it should be conducted with extreme caution and the target for hemoglobin should be under 12g/dL to avoid thrombotic complications and hypertension. [ 76 ] The goal is to use the lowest dose possible to avoid RBC transfusion. No trial has identified an optimal hemoglobin target level, dose, or dosing strategy that is devoid of associated risks. ESA AEs have included hypertension, arthralgia, muscle spasm, pyrexia, dizziness, vascular occlusion, and upper respiratory tract infection. [ 77 ]

Bone Lesions

Lytic bone lesions in patients with MM are slow to heal and patients face lifelong increasing pain, as well as risk of developing skeletal-related event (SREs) such as pathologic fractions or spinal cord compression (SCC), leading to increased morbidity and mortality and decreased QoL. [ 78 ] SCC is an oncologic emergency requiring high-dose corticosteroids, radiation, and/or surgery.

Bone lesions develop in patients with MM due to an uncoupling of normal bone remodeling and have been seen in up to 90% of patients at initial diagnosis. In the bone environment, myeloma cells promote osteoclast activation by secreting MIP1α/β and VEGF and by promoting the secretion of IL1, IL6, TNFα, RANKL, SDF1, and PTHRP by bone marrow-derived stem/stromal cells which increase osteoclast function promoting bone breakdown. Additional factors, such as DKK-1 and sclerostin are secreted which inhibit osteoblast function that are responsible for bone building. This leads to imbalance in bone homeostasis, creating lytic lesions and hypercalcemia. [ 78 ] Excessive RANKL is associated with increased bone resorption and decreased patient survival. [ 79 ]

Bone modifying agents (BMA) including the bisphosphonates pamidronate (Aredia®) and zoledronic acid (Zometa®), and denosumab (Prolia®, Xgeva®) are osteoclast inhibitors approved for prevention of SREs. They do not repair existing bone damage; they serve to prevent the development of new lesions. They can be used with anti-MM therapy in most patients. Both have been postulated to have antimyeloma effects as well. The Myeloma IX trial randomized 1,970 patients with NDMM to receive either IV zoledronic acid, or the weaker oral agent, clondronate. [ 80 ] It was determined that zoledronic acid reduced mortality by 16% and extended median OS by 5.5 months, independent of the benefit of reduction in SREs. These suggested bisphosphonates may have some anti-MM effects.

Bisphosphonates are synthetic analogues to inorganic pyrophosphates found within the bone matrix. They inhibit osteoclastic bone resorption by directly attaching to binding sites on bone surfaces, especially surfaces undergoing active resorption. When the osteoclasts attempt to resorb bone that is bisphosphonate treated, the bisphosphonate released during resorption impairs the ability of the osteoclasts to adhere to the bony surface and to produce the protons (hydrogen ions) and acid hydrolases via lysosomal secretion necessary for continued bone resorption. Bisphosphonates incorporated into the bone matrix also exert a direct apoptotic effect on osteoclasts by disrupting their differentiation and maturation. [ 81 , 82 ] As a class, bisphosphonates are cleared by the kidney and may induce or exacerbate pre-existing renal impairment. [ 62 ]

Denosomab is a human monoclonal antibody (mAb) that binds to, and neutralizes, RANKL, inhibiting osteoclasts and reduces risks of SREs. A RCT that enrolled 1,718 patients found that denosumab was non-inferior for time to SREs and compared zoledronic acid was less nephrotoxic. Renal toxicity occurred in 10% versus 17% and denosumab was also associated with less hypocalcemia events. The incidence of osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) was not significantly different between groups. [ 62 ]

Since prevention of lytic lesions is a major focus in the care of patients with MM, it is recommended that patients receiving primary MM therapy, also receive BMAs. While these have been used in various schedules, and durations, major societies and guidelines now recommended they be used for no more than 2 years to decrease associated risks. Recommendations from the NCCN, ASCO and the IMWG recommend BMA for up to two years. Thereafter, patients may be retreated at relapse. [ 83 ]

Bisphosphonate use requires careful monitoring of creatinine clearance as they can worsen renal function. Pamidronate (Aredia®) is administered over 90 minutes at a dose of 90 mg. In patients with moderate renal function impairment, (creatine clearance 30-60 mL/min) infusions times are prolonged to 4 hours. Zoledronic acid (Zometa®) may be infused over 15 minutes, with its dose reduced to 3 mg in cases of moderate renal impairment, although still infused over 15 minutes [ 84 ]. Patients with hypercalcemia should also receive zoledronic acid.

Osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) is a serious though potentially avoidable complication of bisphosphonate use. Patients must undergo baseline dental examination prior to therapy, and dental surveillance during therapy, with appropriate durations of interruptions during, and after dental interventions. [ 83 ] While on therapy, patients should maintain meticulous oral hygiene and avoid dental procedures that could impact bone.

Additional considerations across therapeutic regimens include the risk of infection. This is due to disease-related immunodeficiency, as well as a direct effect on white blood cells from marrow crowding and therapeutic toxicity. Since early mortality due to serious bacterial infections has been demonstrated to be responsible for nearly 50% of mortality in the first three months after diagnosis, prophylactic antimicrobials are used more liberally in this setting. A randomized study conducted in the United Kingdom evaluated prophylactic levofloxacin in 489 patients, versus placebo in 488. The addition of the antibiotic significantly reduced the incidence of febrile episodes and deaths in newly diagnosed patients on therapy. [ 85 ]

However, the use of prophylaxis is still controversial due to valid concerns such as the potential increased risk of antibiotic resistant organisms, adverse reactions, and drug-drug interactions. Prophylaxis may be beneficial within the first 2-3 months of treatment in patients at high risk for infection, such as those receiving IMids, or in those at high risk of infections due to prior serious infections, or concurrent neutropenia. Prophylactic IV immunoglobulin is not routinely recommended. Treatment-induced severe neutropenia may require granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) and infectious episodes require immediate initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotics. [ 84 ]

Thromboembolic Events

The occurrence of venous thromboembolic events (VTEs) is problematic in patients with a diagnosis of MM, with an estimated 10% of patients developing one or more VTEs during their disease. [ 1 ] They occur more frequently during the initial cycles of treatment and diminish in frequency when the disease is under better control. [ 86 ] A review of almost 5,000 patients with MM demonstrated that VTE is associated with increased mortality at two- and five-years post diagnosis, and that this is independent of other known prognostic factors. [ 87 ]

Risk factors have been broken down into those that are myeloma specific, treatment specific and patient specific. Myeloma specific factors include active uncontrolled disease, and hyperviscosity. Treatment specific factors include chemotherapy, targeted therapies such as IMiDs, high-dose dexamethasone, doxorubicin and multiagent chemotherapy. Patient specific risk factors include history of VTE, obesity, presence of a central venous catheter or pacemaker, and comorbidities such as inherited thrombophilia or clotting disorders, and surgical procedures. 22] Other MM related symptoms such as fatigue and pain contribute to immobility which as an additional risk factor.

Corticosteroids have long been associated with development of VTE and arterial thrombosis in MM. High doses of dexamethasone stimulate increased expression of tissue factor and cellular adhesion molecules, as well as decreased expression of thrombomodulin and plasminogen activator inhibitor in vitro [ 88 ] which would otherwise help prevent clotting. Dexamethasone may also sensitize cells to cytokine stimulation directly. [ 89 ] Low doses dexamethasone has been demonstrated to exert less risk than do higher doses, 3.5 % versus 18.2% [ 90 ], supporting the thrombogenic potential of high-dose dexamethasone.

As discussed in the prior section, and presented in Table 1 , IMiDs increase thrombotic risk. This is thought to occur by their effect on angiogenesis, adhesion of myeloma plasma cells, as well as regulation of the immune system. [ 91 ] Bortezomib is associated with a far lower thrombogenic potential as was demonstrated in the phase 3 VISTA trial. [ 30 ] There is less data with use of carfilzomib, however in the ASPIRE trial, VTE incidence was 13% in the Kyprolis arm vs. 6% in the Rd arm. There were also increased rates of carfilzomib-related hypertension, arrhythmias, myocardial infarctions, and cases of heart failure. [ 92 ]

Anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy has been recommended, and though the preferred agent differs based on patient and therapy-related factors, patients require education regarding the rationale for, and the importance of adhering with, the chosen strategy. If one patient-specific risk factor exists in isolation, thromboprophylaxis with aspirin, dosed at 81-325 mg may be sufficient. Those with two patient-specific, or one treatment-specific risk factor, should be treated with low molecular weight heparins (LMWH) or warfarin [ 76 , 83 ]. LMWH requires daily, or twice daily injections, while warfarin requires strict dietary compliance and is associated with multiple DDIs.

The optimal duration and choice of thromboprophylactic drugs has not been established. More recently, direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) including inhibitors of factor Xa (apixaban, rivaroxaban, edoxaban and betrixaban), and factor IIa (dabigatran), have been introduced into the prophylactic and therapeutic regimens for patients with MM. Though not approved specifically for use in patients with MM at this time, they demonstrate many advantages, particularly in patients with renal impairment and recurrent thromboses. They do not require monitoring, nor SC injections. The EINSTEIN CHOICE trial was a phase 3 RTC which randomized 3,396 patients with VTE to receive either oral rivaroxaban (10 or 20 mg) or aspirin dosed at 100 mg. The primary efficacy endpoint was the composite of recurrent VTE and unexplained death for which pulmonary embolism could not be ruled out. Incidence of major bleeding was the major safety endpoint. Composite efficacy events occurred in 1.5% of patients receiving 20 mg of rivaroxaban and 1.2 of those receiving 10 mg. This compared favorably to the 4.4% of patients on aspirin who experienced an event. Major bleeding was seen in 0.5% (20 mg rivaroxaban), 0.4% (10 mg rivaroxaban) and 0.3% (aspirin). Non-relevant nonmajor bleeds occurred in 2.7%, 2.0% and 1.8% of patients, respectively. The researchers concluded that rivaroxaban was more effective than aspirin. [ 93 ]

Assessment of VTE risk is recommended prior to treatment initiation and careful discussions with patients are necessary regarding the risk-benefit ratio of using an anticoagulant. Patients should be encouraged to stay as active as possible to reduce DVT and PE risk and to inform providers if they plan to travel by air, or by car for long-distances. Providers must maintain a low threshold for diagnostic testing in the event of suspected VTE.

Psychosocial Factors

Psychosocial factors have been demonstrated to influence the supportive care needs of patients, particularly anxiety and depression. Diagnosis with an incurable disease can trigger new disorders and exacerbate those that are pre-existing, negatively impacting quality of life and cooperation with therapeutic recommendations. Uncertainty about the future and lack of information were shown to be important determinants in supportive needs of patients with MM in this regard. [ 94 ]

When patients with MM met for a roundtable in 2015, it was validated that they were aware of the inevitability of relapse and that they preferred to be informed upfront about the treatment plan and likely succession of treatments they would receive during their illness. Uncertainty also developed from the variation in care provided between practice settings. They felt vulnerable due to their lack of medical knowledge and forced reliance of recommendations of physicians. [ 95 ] Connecting patients with support agencies, such as the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation and the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society may provide additional emotional and educational resources as well as direction toward additional resources that can assist with the “financial toxicity” of MM therapy.

Reviewing symptoms at each encounter allows for prompt initiation of aggressive treatments and enhances the ability of patients to stay on treatment. Effective therapies are now available for most toxicities and initiating them as soon as possible is crucial. Much of this is within nursing’s domain. One of the most valuable advocates a patient with MM can have, is his/her office, clinic, and infusion center nurse. Nursing assessments, and communication to report symptoms to other providers, help to increase the team’s ability to adequately address the aforementioned issues, provide more seamless care, an optimize outcomes for patients with MM.

Toxicities of Therapy

Despite rapid advances in treatment, MM remains incurable, and toxicities associated with treatment have an obvious impact on QOL. They are frequently responsible for discontinuation of otherwise therapeutic agent(s). Toxicity mitigation and nursing actions are presented in Table 2 .

Targeted therapies have made a dramatic difference in terms of efficacy and safety for patients with MM. Though multiple myeloma remains incurable, the ability to combine agents to address multiple targets simultaneously is likely to continue and hopefully reach the point of cure for some patients. Development of these drugs and immune therapies has been rapid, and there is no reason to suspect this to change in the near future. As new classes of agents emerge, and new agents within class are developed, nurses can build on past experience to assist patients through the myriad of toxicities in order to take advantage of this evolving science.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

- Member Benefits

- Communities

- Grants and Scholarships

- Student Nurse Resources

- Member Directory

- Course Login

- Professional Development

- Institutions Hub

- ONS Course Catalog

- ONS Book Catalog

- ONS Oncology Nurse Orientation Program™

- Account Settings

- Help Center

- Print Membership Card

- Print NCPD Certificate

- Verify Cardholder or Certificate Status

- Trouble finding what you need?

- Check our search tips.

- Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing

- Number 4 / August 2010

A Case Study Progression to Multiple Myeloma

Mary Ann Yancey

Adam J. Waxman

Ola Landgren

Multiple myeloma consistently is preceded by precursor states, which often are diagnosed incidentally in the laboratory. This case report illustrates the clinical dilemma of progression from precursor to full malignancy. The article also discusses future directions in management and research focusing on myelomagenesis.

Become a Member

Purchase this article.

has been added to your cart

Related Articles

Emerging from the haze™: pilot feasibility study comparing two virtual formats of a cognitive rehabilitation intervention, a systematic review of cognitive impairment in individuals with colorectal cancer, predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating factors of insomnia in cancer survivors.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 18 February 2021

Management of patients with multiple myeloma beyond the clinical-trial setting: understanding the balance between efficacy, safety and tolerability, and quality of life

- Evangelos Terpos ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5133-1422 1 ,

- Joseph Mikhael 2 ,

- Roman Hajek ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6955-6267 3 ,

- Ajai Chari 4 ,

- Sonja Zweegman 5 ,

- Hans C. Lee 6 ,

- María-Victoria Mateos ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2390-1218 7 ,

- Alessandra Larocca ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2070-3702 8 ,

- Karthik Ramasamy 9 ,

- Martin Kaiser ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3677-4804 10 ,

- Gordon Cook 11 ,

- Katja C. Weisel ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9422-6614 12 ,

- Caitlin L. Costello 13 ,

- Jennifer Elliott 14 ,

- Antonio Palumbo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1763-6609 14 &

- Saad Z. Usmani 15

Blood Cancer Journal volume 11 , Article number: 40 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

9117 Accesses

47 Citations

21 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Adverse effects

- Cancer therapy

- Quality of life

Treatment options in multiple myeloma (MM) are increasing with the introduction of complex multi-novel-agent-based regimens investigated in randomized clinical trials. However, application in the real-world setting, including feasibility of and adherence to these regimens, may be limited due to varying patient-, treatment-, and disease-related factors. Furthermore, approximately 40% of real-world MM patients do not meet the criteria for phase 3 studies on which approvals are based, resulting in a lack of representative phase 3 data for these patients. Therefore, treatment decisions must be tailored based on additional considerations beyond clinical trial efficacy and safety, such as treatment feasibility (including frequency of clinic/hospital attendance), tolerability, effects on quality of life (QoL), and impact of comorbidities. There are multiple factors of importance to real-world MM patients, including disease symptoms, treatment burden and toxicities, ability to participate in daily activities, financial burden, access to treatment and treatment centers, and convenience of treatment. All of these factors are drivers of QoL and treatment satisfaction/compliance. Importantly, given the heterogeneity of MM, individual patients may have different perspectives regarding the most relevant considerations and goals of their treatment. Patient perspectives/goals may also change as they move through their treatment course. Thus, the ‘efficacy’ of treatment means different things to different patients, and treatment decision-making in the context of personalized medicine must be guided by an individual’s composite definition of what constitutes the best treatment choice. This review summarizes the various factors of importance and practical issues that must be considered when determining real-world treatment choices. It assesses the current instruments, methodologies, and recent initiatives for analyzing the MM patient experience. Finally, it suggests options for enhancing data collection on patients and treatments to provide a more holistic definition of the effectiveness of a regimen in the real-world setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Antibody drug conjugate: the “biological missile” for targeted cancer therapy

Targetable leukaemia dependency on noncanonical PI3Kγ signalling

Long-term outcomes following CAR T cell therapy: what we know so far

Introduction.

Today’s physicians treating multiple myeloma (MM) are faced with the challenge of individualizing treatment choices associated with the highly diverse patient populations seen across all treatment settings. Historically, median overall survival (OS) for MM patients was only ~3 years 1 , and there were a limited number of agents/regimens available. Now there is an increasing range of highly active treatment options available, offering novel combinations and leading to the marked improvements in patient outcomes seen in randomized clinical trials over the past 15 years 2 . These changes in the MM treatment landscape make the current scenario much more complex, requiring physicians to weigh varying goals of treatment in different settings 3 , 4 , 5 . The objectives of this review are to provide a comprehensive summary of the key factors that determine treatment goals and drive treatment choices for patients—specifically, therapy-related factors impacting patient-reported outcomes (PROs) that are additional to those related to commonly administered agents and other supportive pharmacologic interventions—and to summarize existing and emerging methodologies for capturing these drivers of treatment choices.

The gap between the clinical-trial and real-world settings

Phase 3 studies remain the ‘gold standard’ for obtaining regulatory approvals, based on their strong internal validity, prespecified and well-defined endpoints, and use of randomization, blinding and control arms. Favorable efficacy and benefit:risk balances have been demonstrated in clinical trials for multiple new standard-of-care regimens in recent years. However, these prospective studies have limitations in terms of external validity and generalizability. Frequently, these clinical-trial data are first reported after a median follow-up of 1–2 years, and thus the ability of patients to continue treatment beyond the initial period is unknown. The increasingly complex novel-agent-based regimens are typically associated with toxicity additional to that arising from standard backbone agents such as dexamethasone, and in the real-world setting the feasibility of and adherence to these regimens may be more difficult. The full benefit may not be derived if drugs and regimens are not: (i) tolerable enough for real-world patients and may thus impact their quality of life (QoL), including for specific patient populations such as elderly/frail patients; (ii) available to patients, e.g., due to limited mobility or travel issues/preference, or due to affordability; or (iii) in line with patients’ preferences. There is a need for efficacious options that meet these criteria, and physicians require a balance of all relevant information when making treatment decisions.

Additionally, phase 3 studies may include an unrepresentative patient population. Many real-world and registry studies have concluded that approximately 40% of MM patients in the real world do not meet the criteria for inclusion in phase 3 studies on which approvals are based (Table 1 ) 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 . Patients may be ineligible for a range of reasons, including poor performance status, inadequate organ function, and adverse medical history or comorbidities, meaning that they are underrepresented in phase 3 clinical trials. As documented by these studies, clinical trial ineligibility is often associated with significantly poorer outcomes compared to those reported in trial-eligible patients, including shorter progression-free survival (PFS) and OS (Table 1 ) 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 . This leads to a lack of representative phase 3 trial data for this high proportion of real-world patients.

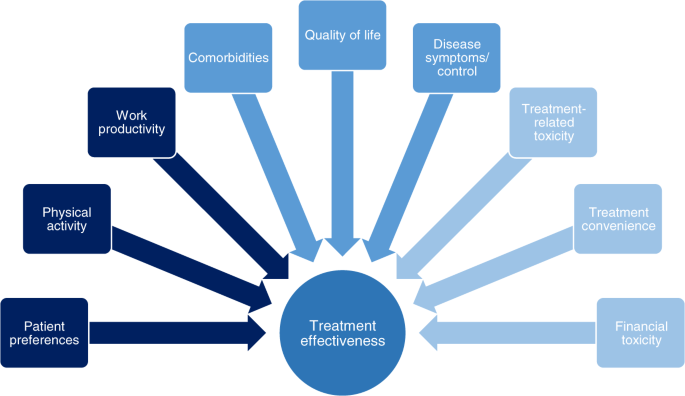

Additional considerations in real-world patients

In patients who are underrepresented in phase 3 clinical studies, treatment decisions must be based on additional considerations. We review multiple factors in addition to the traditional definition of efficacy that are key when considering the real-world MM patient experience (Fig. 1 ) 12 , 13 , 14 , including PROs. Those that may affect a patient’s health-related QoL in the real-world setting include their disease symptoms and how they are controlled, including supportive care, adverse events (AEs) associated with therapy, and pre-existing comorbidities. Also important to patients is their ability to participate in daily activities, the support available to them, access to treatment, and—particularly for elderly/frail patients—access to treatment centers 12 , 13 , 14 . The level of data captured on such patient-focused outcomes is another limitation of prospective phase 3 clinical studies.

There are multiple factors of importance to MM patients regarding their treatment that impact on the effectiveness of that treatment in the real-world setting.

We highlight that the relative importance of these different factors, and the goals of treatment, differ between patient groups and treatment settings—suggesting that ‘efficacy’ does not necessarily mean the same thing to different patients and depends on the balance of all attributes of a drug or regimen. In this context, a holistic needs assessment is valuable for making treatment choices, with broad support from a multidisciplinary team in the clinic and at home, and will assist in defining efficacy/effectiveness for each individual patient 15 , 16 . Additionally, in order to fully capture the patient’s experience of their MM treatment, it is necessary to be able to analyze and—where feasible—quantify all the relevant real-world drivers; we therefore also review the various instruments and studies developed to capture treatment impact/burden and preferences.

Factors of importance to patients in the real-world setting

Symptom burden.

Among the hematologic malignancies, MM patients have the greatest symptom burden 17 . Symptoms related to the CRAB criteria (hypercalcemia, renal impairment, anemia, and bone disease) can be debilitating and may require supportive therapy such as bisphosphonates or denosumab 18 . These symptoms, along with fatigue, pain, gastrointestinal symptoms 16 , 19 , 20 , 21 , and other common disease-related complications such as neuropathic symptoms, as well as side effects that may arise from supportive therapy, can result in MM patients having significantly impaired QoL compared to the general population 16 , 19 , 20 , 22 , 23 , 24 . This highlights the need for rapid symptom control and minimal toxicity when choosing a treatment. However, in many clinical trials, patients with only biochemical progression are overrepresented.

Side effects

Real-world studies of patients’ preferences have highlighted side effects of treatment as an important consideration. Various specific toxicities have been identified as being associated with specific agents, including peripheral neuropathy with bortezomib 25 and thalidomide 26 , fatigue with lenalidomide 27 , cardiovascular side effects with carfilzomib 28 , 29 , gastrointestinal and hematologic side effects with ixazomib 30 , 31 , lenalidomide 26 , 32 and panobinostat 33 , 34 , and fluid-retention effects, bone loss, eye complications and insomnia with corticosteroids 16 , with associated QoL decrements having been reported due to some of these toxicities. Real-world analyses have identified the substantial role played by toxicities in treatment discontinuation in both the frontline setting 35 , 36 and more so in later lines 36 , suggesting that toxicities are more burdensome and limit the duration of treatment more substantially in the real-world setting compared with pivotal phase 3 studies. Such shortening of treatment duration due to toxicity has been shown to adversely impact outcomes 37 , highlighting how safety is an important component of efficacy.

Daily activities

Multiple reports have demonstrated the value to patients of being able to continue with activities of daily living and of maintaining good physical and mental well-being. Impairment of activities of daily living due to MM and its treatment or other comorbidities is associated with poorer prognosis, as demonstrated by analyses of outcomes according to frailty indices 38 , 39 , as well as patient frustration 40 . The ability to continue with one’s daily routine and physical activities while receiving treatment is associated with fewer side effects and lower fatigue and is appreciated by patients as it improves QoL 41 , 42 , 43 .

These findings highlight the importance of gathering PROs in the context of considering the efficacy of a treatment regimen and taking into consideration the value patients place on being able to continue with their regular lives as much as possible. The associated mental health and well-being of the patient should be considered too 14 , 44 , as adverse impacts on a patient’s activities and emotional functioning may curtail treatment duration and effectiveness.

Financial toxicity

Another aspect of concern to MM patients is the cost of treatment 12 , 14 , 21 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , although the importance of this varies substantially worldwide according to healthcare system and access to drugs. Financial hardship may result from direct out-of-pocket costs arising from treatment and its side effects, depending on the healthcare system, and other indirect costs such as those involved in attending appointments (e.g., travel costs) and any compensation loss arising from impaired ability to work 46 , 47 . Studies have shown that such issues impact patients’ QoL 12 , 14 , 44 . Thus, treatment effectiveness may also be dependent on a patient’s ability to cope with the financial toxicity associated with receiving their regimen on a long-term basis.

Treatment convenience/route of administration

Of related importance to patients is the convenience of treatment. While some patients may value the regular face-to-face contact with their treating physician/care team required with parenterally administered medications, some prefer oral medications even in the context of shorter progression-free time and/or more AEs 48 . This may be driven by various reasons; for example, patients may not be able to travel to infusion centers for treatment, due to limited mobility or distance from the clinic, they may wish to avoid the clinic/hospital setting due to specific circumstances, or they may want to minimize treatment burden associated with frequent hospital/clinic visits. Recent analyses have indicated patients’ preference for oral treatment is based on greater convenience, less impairment of daily activities, and less impact on work/productivity 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 . In this context, the feasibility of receiving treatment at home may be a relevant consideration, particularly in the current COVID-19 pandemic, with some studies showing domestic administration of therapy in MM patients spared the burden of repeat hospital transfers, leads to a low rate of treatment discontinuation 52 , and substantially improved QoL.

Different patients, different perspectives: patient preferences in the real-world setting

Patients are becoming increasingly involved in their own treatment decision-making 53 , and their specific preferences, including the importance they attach to each of the factors discussed in the previous section, as well as their overall treatment goals, must be considered when selecting a regimen 54 . As MM is a heterogeneous disease with a heterogeneous patient population, these preferences and goals of treatment may differ between patients, depending on multiple patient-related, disease-related, and treatment-related factors 3 , 4 , 5 , 14 , 54 , 55 . ‘Efficacy’ therefore means different things to different patients. Treatment decision-making in the context of personalized medicine needs to be guided by an individual’s composite definition of what constitutes an effective treatment, per their preferences and treatment goals, in order to achieve the right balance between efficacy, safety, tolerability, feasibility, QoL, and treatment satisfaction 55 .

Within a specific patient population, drivers for treatment selection may be more granular in detail. For example, among younger MM patients, while some prioritize life expectancy/survival 44 , a discrete-choice experiment showed that others value preserving further treatment options, ‘not always thinking of the disease’, and treatment-free intervals as important characteristics of therapy, along with effectiveness 56 . Additionally, younger patients have been reported to rank severe or life-threatening toxicity as a greater concern than mild or moderate chronic toxicity more frequently than older patients, associated with the need to continue working and supporting their families 57 . However, younger, fitter patients may opt for an intensive treatment including stem cell transplantation in order to elicit a very deep response, improve their QoL, and achieve a lengthy remission and potential functional cure 58 .

In contrast, among elderly/frail MM patients, preferences may differ and factors of importance may be ranked differently. Frail patients may be older and/or have more comorbidities than fitter patients, and are at a greater risk of experiencing non-hematologic toxicity and of discontinuing treatment for reasons other than progression/death 38 . Furthermore, frail patients are less able to receive and tolerate intensive treatment approaches intended to induce deep responses 59 . Thus, for some of these patients, disease control and maintaining QoL may be priorities 2 , with comorbidities and the challenges of polypharmacy, potential toxicities associated with treatment, and functional limitations potentially weighted more heavily when making treatment decisions 60 . Treatment convenience and the ability to continue with daily activities may be of substantial importance in elderly/frail patients in the context of potentially receiving longer term, less-intensive treatment regimens than younger/fit patients.

As well as differing between groups of patients, preferences and weighting of factors of importance may also differ in the same patients at different stages of their treatment course. For example, among relapsed/refractory MM patients, a primary concern is the efficacy of their treatment regimen due to the desire to get their disease back under control after experiencing relapse. While QoL in newly diagnosed MM patients may be expected to increase during/following treatment, at relapse it may be expected only to stabilize 61 ; therefore, QoL may perhaps be weighted less heavily when choosing treatment in these patients. Nevertheless, an underlying consideration for all treatment choices is that safety and tolerability are consistent drivers for efficacy, as the longer a patient can stay on treatment, the greater the therapeutic benefit they can accrue.

Measurement of PROs: analyzing real-world preferences and factors of importance