Lessons About Changing Culture - GM/Toyota Case Study

Culture changes when values are integrated into day-to-day operations.

Dustin Roman

In the early 1980’s GM’s Fremont plant was one of the worst-performing plants in the company. The labor force was also considered to be the worst in the entire auto industry. Absenteeism was over 20%. Sometimes so few people showed up, they would have to pull people from a local bar to start the assembly line.

Workers were constantly on strike and filing grievances. Sex and drugs were rampant in the factory. They were even known to sabotage quality, putting coke bottles in door panels to annoy eventual customers. Finally, in 1982 GM had enough and shut down the factory.

However, fortunes would change a few years after a partnership between GM and an overseas automaker. Toyota was behind competitors Nissan and Honda in their expansion, and they were facing pressure to start producing vehicles in the United States.

Instead of opening a new plant on their own, Toyota wanted to learn quickly how to transfer and teach their system to American workers. GM knew about Toyota’s production system and thought learning from them could benefit their company as well. So a partnership was formed, and they chose to bring an old factory back online.

In 1984 the Fremont factory produced its first car in 2 years. This time around, the factory would have extremely different results. Defects dropped to be one of the best in the country. Absenteeism fell from 20% to 2%. Even more impressive, they did this with the same workforce that plagued that plant only a few years earlier.

So what changed?

John Shook, who Toyota hired to oversee this joint venture, writes;

“As someone who was there at its launch and witnessed a striking story of phenomenal company culture reinvention, I am often asked: “What did you really do to change the culture at NUMMI (GM/Toyota partnership) so dramatically, so quickly?”

I could answer the question from high altitude by simply saying, “We instituted the Toyota production and management systems.” But in the end that doesn’t explain much.

A better way to answer is to describe more specifically what we actually did that resulted in turning the once dysfunctional disaster — GM’s Fremont, California, plant — into a model manufacturing plant with the very same workers. And describing what we did, and what worked so profoundly, says some interesting things about what “culture” is in the first place.”

This article will look at the Toyota production and management system and how it was developed. We will also look at some lessons on how to change a culture from its implementation in the GM plant.

Toyota's Values

Sakichi Toyoda started Toyoda Automatic Loom Works in 1926. He was a tinkerer, inventor, and engineer who had a zeal for continuous improvement. A trait that would define his company and family values. He observed that technology was changing and the loom business he built would eventually be obsolete.

He encouraged his son Kiichiro Toyoda to inherit his business and create something of his own. He tasked him with creating a company that would benefit society and move away from the older loom technology into something new. Kiichiro, like his father, was also an engineer and eventually founded Toyota Motor Company. He would build on his father's values and create new aspects that would eventually make up part of the Toyota production system.

However, while he was building his company, Japan was devastated by the aftermath of WWII. Nuclear bombs and war destroyed most industries. Inflation also ran rampant, and consumers had little money. So while Kiichiro cut costs wherever he could to prevent layoffs (a value still held by the company), he was forced to ask 1600 workers to retire. As a result, workers conducted public demonstrations to show their dissatisfaction with the company.

To bring some peace, Kiichiro accepted responsibility for his failures and stepped down as president of Toyota. Another member of the family, Kiichiro’s cousin Eiji Toyoda, would carry the torch. Coming from similar family values, he would continue developing Toyota’s unique approach to production and management.

Toyota’s process comes from a combination of necessities, problem-solving, and family values. Jeffrey Liker, author of The Toyota Way: 14 Management Principles from the World's Greatest Manufacturer explains;

“Toyota started with the values and ideals of the Toyoda family. To understand the Toyota Way, we must start with the Toyoda family. They were innovators, they were pragmatic idealists, they learned by doing, and they always believed in the mission of contributing to society. They were relentless in achieving their goals. Most importantly, they were leaders who led by example.”

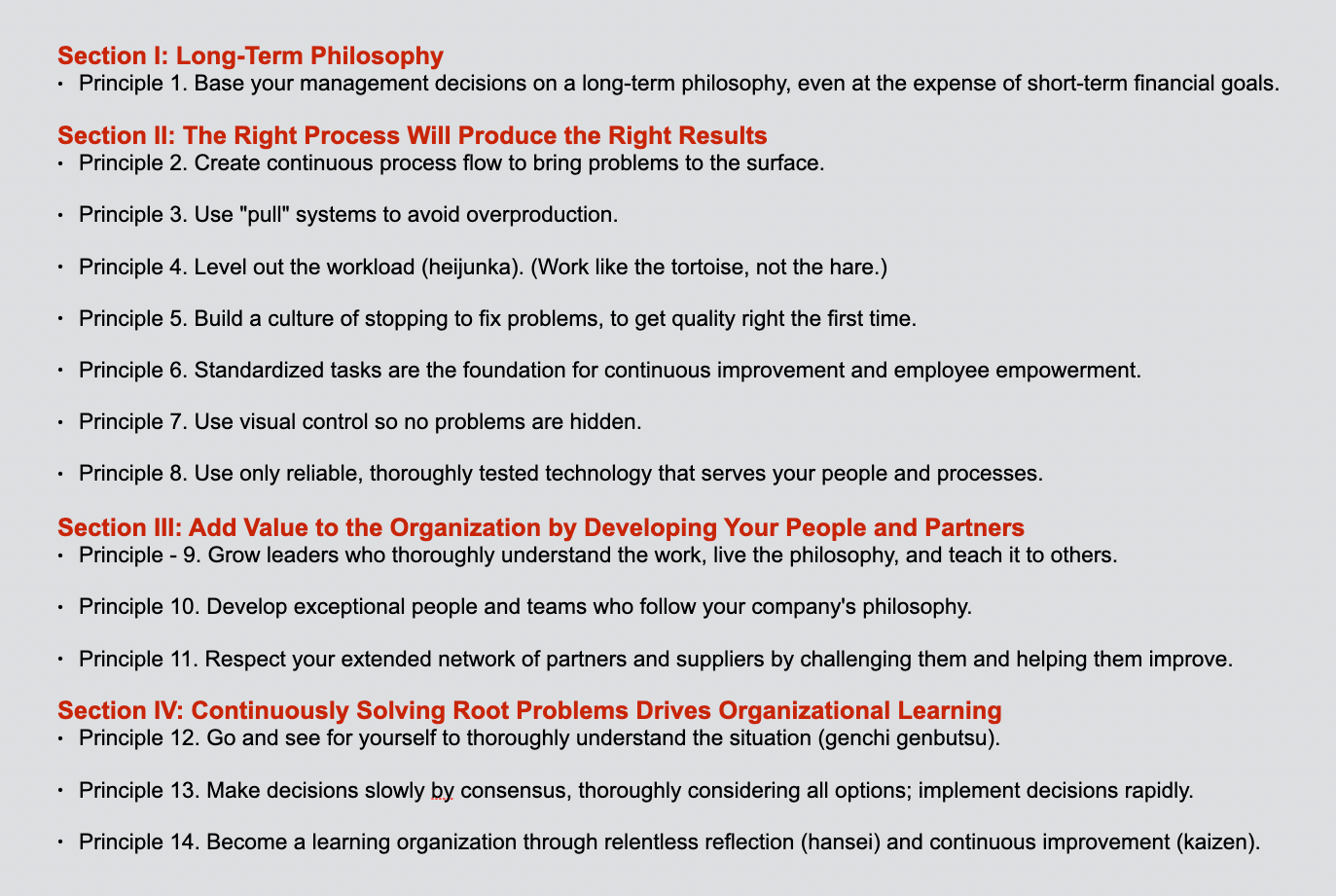

So what is the Toyota process or what Liker refers to as the “Toyota Way”? While I won’t go into the specifics of each principle, here is an overview.

Change Culture by Changing Actions

Most organizations have values that sound good. But, values alone don’t explain how the workers were able to buy into and implement them. We can go back to the Fremont Factory, and John Shook to understand better why they worked from a cultural perspective.

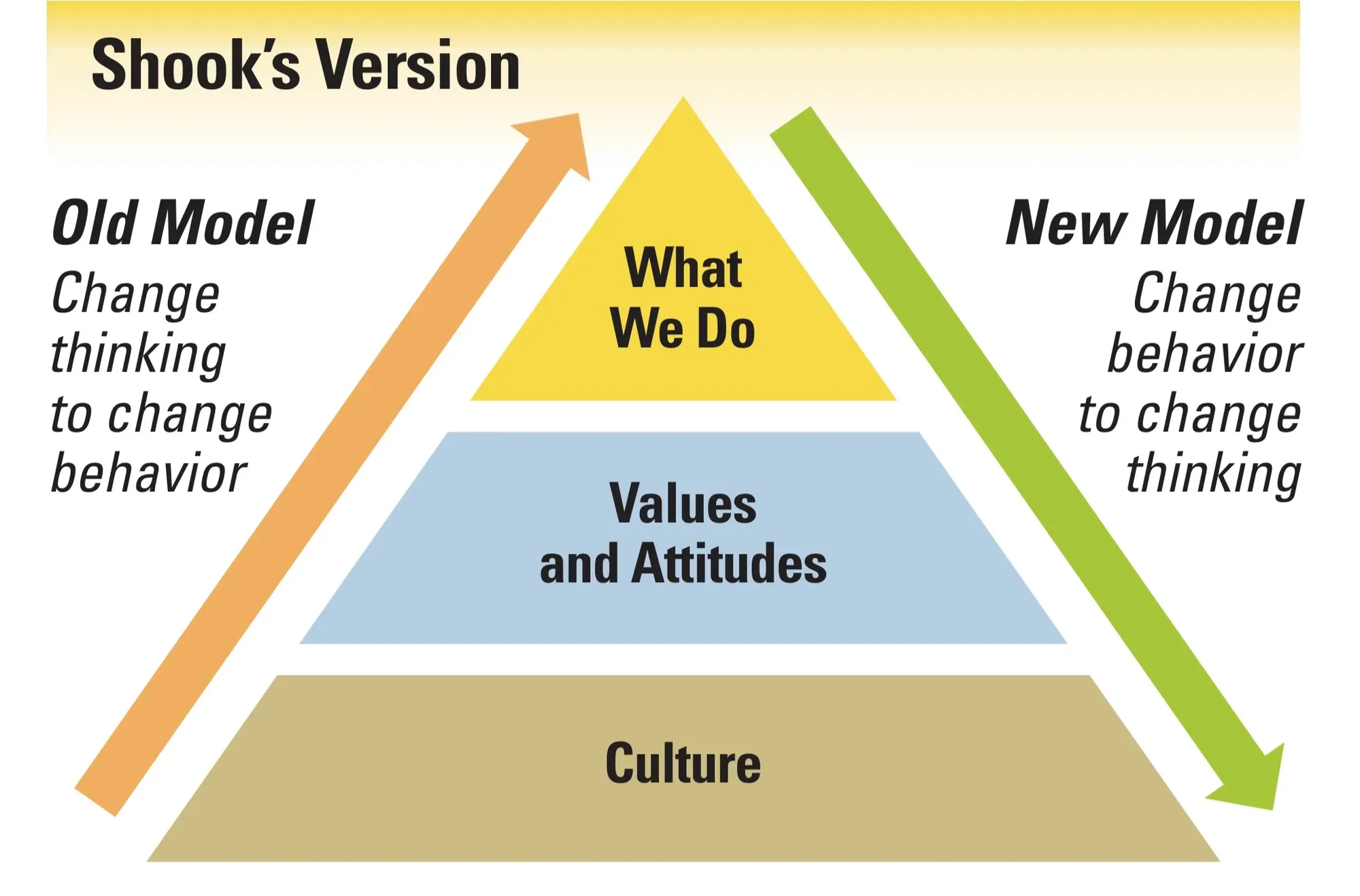

Traditional thinking is to work on culture directly. Inspire and change people's values and beliefs, eventually encouraging them to change their actions and behaviors. However, Shook argues that it is more effective to start with actions first;

“Those of us trying to change our organizations’ culture need to define the things we want to do, the ways we want to behave and want each other to behave, to provide training and then to do what is necessary to reinforce those behaviors. The culture will change as a result.”

(The concept of our values/beliefs forming to justify our actions is also supported by Psychologist Jonathan Haidt)

Basically, Toyota designed everything around how they want their employees to demonstrate their values or what they want to accomplish. This sounds simple, but in my experience, this is one of the hardest concepts for organizations to achieve.

Part of the job responsibility or how they want their employees to "behave" is to consistently find problems and improve (similar to how the founders behaved). An example of what this looks like is the concept of “stop the line,” a process during the assembly line where a worker is expected to pause production if they encounter a problem. This aligns with their values and what they want to accomplish. Most places wouldn’t give this much responsibility to a front-line worker.

"When NUMMI was being formed, though, some of our GM colleagues questioned the wisdom of trying to install andon there. “You intend to give these workers the right to stop the line?” they asked. Toyota’s answer: “No, we intend to give them the obligation to stop it — whenever they find a problem.” - Shook

Stopping the line has consequences for production, but each Toyota worker knows that this is part of their job title. They are given knowledge and skills to know when they have encountered a problem and the next steps to solve it. This process of identifying problems is expected and reinforced at all levels of management.

“As general manager of production control — arguably Toyota’s area of most unique operational expertise — Uchikawa had a team of six very smart, midlevel GM managers working for him. Being very smart, young GM managers, they had a ready response whenever Uchikawa asked them to report on how things were proceeding — “No problem!” The last thing they wanted was their boss sticking his nose into their problems. Finally Uchikawa exploded, “No problem is problem! Managers’ job is to see problems!” ” - Shook

If all of that sounds simple, compare the concept of empowered employees to identify and address problems to traditional organizations (which probably state something similar).

“ In early 1995 at an assembly plant on the outskirts of Detroit, I observed a worker make a major mistake. A regular automated process was down for the day, so the worker was making do with a work-around. And with the work-around, he managed to attach the wrong part on a car. He quickly realized his mistake, but by then the car had already moved on, out of his work station. That’s when I saw an amazing thing.

There was nothing that the worker could easily do to correct his mistake! Scratch the word “easily” from that. There was nothing at all that he could do. This was far from the NUMMI/Toyota process of making it (1) difficult to make a mistake to begin with; (2) easy to identify a problem or know when a mistake was made; (3) easy in the normal course of doing the work to notify a supervisor of the mistake or problem; and (4) consistent in what would happen next, which is that the supervisor would quickly determine what to do about it.

But for that worker on the Big Three assembly line, there was, practically speaking, nothing he could do about the mistake he had just made. No rope to pull. No team leader nearby to call. A red button was located about 30 paces away. He could walk over and push that button, which would immediately shut down the entire line. He would then indeed have a supervisor come to “help” him. But he probably wouldn’t like the “help” he would get.” - Shook

The Toyota "way" is born out of a combination of values and pragmatic systems. However, good values alone don't create a culture of success. People have to believe in those values and execute them. This doesn't happen by only speaking to values and hoping that people buy-in. Those values have to be integrated into everything from job titles to day-to-day processes. Making it easy for people to do their job means they can be successful at their job. Their success then changes their attitude toward that job.

“What changed the culture at NUMMI wasn’t an abstract notion of “employee involvement” or “a learning organization” or even “culture” at all. What changed the culture was giving employees the means by which they could successfully do their jobs. It was communicating clearly to employees what their jobs were and providing the training and tools to enable them to perform those jobs successfully.” - Shook

- How to Change a Culture: Lessons From NUMMI by John Shook

- https://www.npr.org/transcripts/125229157

- The Toyota Way: 14 Management Principles From the World's Greatest Manufacturer by Jeffrey Liker

Sign up for more like this.

Brought to you by:

Toyota Motor Manufacturing, U.S.A., Inc.

By: Kazuhiro Mishina

On May 1, 1992, Doug Friesen, manager of assembly for Toyota's Georgetown, Kentucky, plant, faces a problem with the seats installed in the plant's sole product--Camrys. A growing number of cars are…

- Length: 22 page(s)

- Publication Date: Sep 8, 1992

- Discipline: Operations Management

- Product #: 693019-PDF-ENG

What's included:

- Teaching Note

- Educator Copy

- Supplements

$4.95 per student

degree granting course

$8.95 per student

non-degree granting course

Get access to this material, plus much more with a free Educator Account:

- Access to world-famous HBS cases

- Up to 60% off materials for your students

- Resources for teaching online

- Tips and reviews from other Educators

Already registered? Sign in

- Student Registration

- Non-Academic Registration

- Included Materials

On May 1, 1992, Doug Friesen, manager of assembly for Toyota's Georgetown, Kentucky, plant, faces a problem with the seats installed in the plant's sole product--Camrys. A growing number of cars are sitting off-line with defective seats or are missing them entirely. This situation is one of several causes of recent overtime, yet neither the reason for the problem nor a solution is readily apparent. As the plant is an exemplar of Toyota's famed production system (TPS), Friesen is determined that, if possible, the situation will be resolved using TPS principles and tools. Students are asked to suggest what action(s) Friesen should take and to analyze whether Georgetown's current handling of the seat problem fits within the TPS philosophy.

This case is accompanied by a Video Short that can be shown in class or included in a digital coursepack. Instructors should consider the timing of making the video available to students, as it may reveal key case details.

Learning Objectives

1) Provide comprehensive knowledge on Toyota Production System,

2) Exercise advanced root cause analysis, and

3) Demonstrate the totality of manufacturing, especially the link between production control and quality control.

Sep 8, 1992 (Revised: Sep 5, 1995)

Discipline:

Operations Management

Harvard Business School

693019-PDF-ENG

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

Toyota Motor Manufacturing Case Study

What would be done to address quality (“seat” problem)-doug friesen, existing options, recommendations, and reasons, divergence of the present routines from the principles of tps, real problem(s) facing doug friesen, works cited.

The “seat” problem in Toyota Motor Manufacturing (TMM) Company requires immediate resolution. As evident from the case provided, the condition is worsening and might hinder the productivity of TMM. The company upholds the aspects quality and competitiveness. Thus, it can hardly install defective Camry seats in its new vehicle models due to quality issues (Mishina 1).

As the CEO of the company, Doug Friesen could have done a lot in order to address the quality issues regarding the seat problem. This is a significant provision when considered critically in the Toyota’s context. The processes set to ensure quality provisions within the company should be augmented to ensure that every department addresses quality issues with precision.

The first recommendable action is to order the supplier of Camry seats (Kentucky Framed Seats) to observe quality in its production systems. This will ensure that the seats they supply meet the quality standards set Toyota Corporation. Doug Friesen could have instructed KFS to produce Camry seats with substantial fitting provisions that minimize damages during their installation.

This will allow employees in the seat installation section to uphold quality and minimize the alleged seat damages. Evidently, how some of the seats are made contribute to the damages witnessed during their installation processes. This is quite discouraging and might force the company to change supplier of its required seats.

Additionally, the CEO would have instructed the concerned departments to observe vigilance while handling seats. This will help in upholding the stipulated quality with regard to seat installation. Additionally, Doug Friesen could have proposed the production of other viable seat designs for the concerned vehicles. This would have helped in alleviating the problems noticed with the defective Camry seats (Erjavec 55).

Ability to incorporate the entire production stakeholders and the department of quality assurance could have also helped in curbing the noticed seat problem. It is from this context that the whole problems facing the company could be alleviated. Additionally, it is important to consider the fact that having proficient workforce and seat designers who could make the required none-defective seats could have helped considerably.

As the CEO, Doug Friesen should act cautiously with precision. It is evident that the seat designs and their nature do not allow for effective installation. Liaising with the supplier of Camry seats (Kentucky Framed Seat-KFS) through relevant departments within the organization could equally help in the situation (Mishina 7). In such instances, KFS would obviously adjust its quality systems and change seat design to the better.

This would have solved the alleged seat problem once and for all. Nonetheless, employees were mandated to install the seats cautiously and report all the problems detected during the installation processes. This would have helped in redesigning the seats to suit the new vehicle models produced by Toyota. Contextually, this is an important provision due to its relevancy.

There are various options that can help in solving the seat problem presented in the provided case. Firstly, Toyota can change the seat supplier. The company can outsource another firm, which will provide the recommended seats with no defects and at a cheaper cost. This is an imperative provision in the entire production context. It can help in solving the seat problem with promptness.

Additionally, the company will be able to reduce costs and increase profits. However, changing the seat supplier can also interfere with the production processes and efficiency that the company has been embracing. It will take the new supplier a considerable duration to design the new seats, test their viability, and launch their mass production.

Contextually, it is considerable to change the supplier despite the probable challenges mentioned before. It is crucial to consider various aspects of this provision before enacting other inconsiderable measures. This will allow Toyota Motors to explore other new talents in the realms of seat designers, efficacy, and modernity.

Another considerable option in this context is changing the seat design such that the parts that create problems during installation are corrected precisely. It is illogical to damage the seats during installation due to their poor structures (Mishina 3). Despite the needs to grant customers some comfort within the vehicles, the aspects of production should also be considered for viability.

Evidently, it is quite costly to continue attaining faulty seats while the condition can be corrected with utmost precision. Considerably, changing the seat design is a viable option helpful in reducing wastage of resources. This is a significant option when scrutinized critically. Restructuring the concerned seat design will be helpful in augmenting the efficiency of production, reliability, and other relevant business provisions.

Another viable option in this context is the augmentation of quality assurance requirements. It is the mandate of the company to cope with the situation in a positive manner as it sources for viable options helpful in this context. The seat problem should not continue to distract the efficiency of employees since there are efforts on the ground to correct it.

As indicated before, caution during the alleged installation can help considerably in the matter. Additionally, the quality department will ensure that the seats made for installation abide by the quality demands of the company and enhance the efficiency of the workflow. Seats, which are easy to install, will not distract the production and assembly processes.

Concurrently, the company will achieve its quality demands stipulated in this context. It is crucial for TMM to consider this provision in the entire production context in order to remain relevant and competitive in the motor vehicle industry. Managing to execute the demanded duties will equally contribute to the alleged quality provisions and production efficiencies.

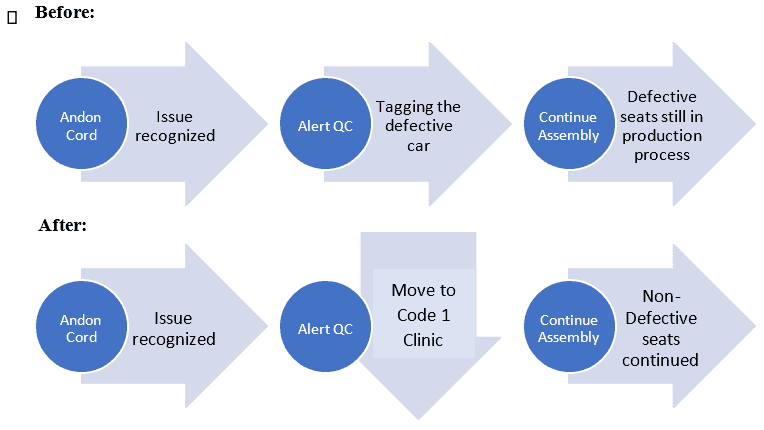

The Toyota Production Systems (TPS) has two principles governing its operations in order to attain value, efficacy, suitability, and adjustability to the constantly shifting market demands. Conversely, current practices used to manage faulty seats diverge considerable from the stipulated TPS principles.

The first principle of TPS is JIT (Just-In-Time) where the company intends to produce only what is needed, at the right time, place, and quantity (Mishina 2). This is meant to eradicate wastage of resources and other impracticable production concepts. Evidently, some aspects of the routines used to handle defective seats are incongruent with the JIT principles of quality, efficiency, and appropriateness.

Firstly, rejection of defective seats translates to wastage of resources and valuable production time. Seats should be inspected at the supplier’s site before introducing them into the Toyota’s production systems within the company. By using defective seats, it means that Toyota will be producing what is not needed in the market. Hence, the company will not meet the intended market demands.

Consequently, this will interfere with the viability and appropriateness of the company. Precisely, this provision hardly conforms to the JIT’s quality provisions embraced by TPS. It is important to observe the production duration used by the company in order to understand evident loopholes that characterizes the matter.

The second considerable principle embraced by TPS is the ability to put production systems focused on detecting problems. TPS achieves this by stopping production processes upon detection of any problem within the production systems. This is helpful in curbing problems promptly before they spread within the entire production systems.

Since the routine production systems do not stop their operations even after detecting defective seats, they hardly conform to the provisions of viable corrective measures as demanded by TPS. It is proper to consider such provisions in the business context. It helps in saving time, reducing costs, and improving efficiency.

Considerably, it is the mandate of every organization to uphold the aspects of quality and effective production processes. Since Toyota returns defective seats to KFS for replacements, it is evident that there are considerable delays in the entire production processes. Inability to correct the defective seats in time equally defies the principle of TPS in observing promptness and quality provisions.

Toyota considers the quality of Camry seats used in the new Wagon models produced by the company (Erjavec 55). Since the occurrence of defective seats is a stumbling block to the entire production processes, it is important to agree that there is a massive deviation from TPS’s quality and timely provisions.

From the provided case study, it is evident that Doug Friesen is faced by numerous problems. This ranges from managerial prospects to workforce concerns. One major problem that is facing Doug Friesen is the seat problem (Mishina 1). The emergence of defective seats witnessed within the production system is a major problem. It retards the organization’s efficiency and the productivity of the concerned organization.

This necessitates a massive eradication of this problem forever. The way through which Toyota Corporation would solve this problem explicitly is a massive concern to Doug Friesen. He must mediate its viability in various contexts. Additionally, since he is the CEO of the organization, he must react swiftly, cautiously, and meaningfully in order to correct the situation within the required duration and with precision.

This is a considerable option for Doug Friesen, which he must observe carefully. Evidently, he started to investigate the matter by himself in order to have a viable applicability of the matter. Contextually, it is important to eradicate uncertainties, reservations, and apprehensions within the company and beyond.

Another noticeable problem that faces Doug Friesen is how to enhance productivity of the company and deal with the issues of extended work durations. Employees complain of continuous work minus rest. Since there are higher demands for new model vehicles, the company has to increase its productivity in order to grasp the increasing customer demands and other probable provisions.

Proper management and convincing employees to work extensively is of a massive concern to Doug Friesen. Precisely, the need to resolve the “seat” problem, enhance the sale of new vehicle models, advance the company, embrace new vehicle models, and manage employees properly are noticeable problems facing Doug Friesen.

Erjavec, Jack. Automotive Technology: A Systems Approach . Sydney: Thomson/Delmar Learning, 2005. Print.

Mishina, Kazuhiro. Toyota Motor Manufacturing, U.S.A., Inc . Massachusetts, MA: Harvard Business School, 1995. Print.

- Weight Management Programs and Hypnotherapy

- Conviction and Punishment

- Toyota Company's Controlling and Cost Cutting

- Enron Corp. Business Environment and Strategic Position

- Business Analysis of Dell Inc.

- Eastman Kodak and Photographic Film Industry Major Changes

- The MacDonald Restaurant in Estonia

- Strategic HRM: Resource-Based View

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, May 20). Toyota Motor Manufacturing. https://ivypanda.com/essays/toyota-motor-manufacturing-case-study/

"Toyota Motor Manufacturing." IvyPanda , 20 May 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/toyota-motor-manufacturing-case-study/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'Toyota Motor Manufacturing'. 20 May.

IvyPanda . 2019. "Toyota Motor Manufacturing." May 20, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/toyota-motor-manufacturing-case-study/.

1. IvyPanda . "Toyota Motor Manufacturing." May 20, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/toyota-motor-manufacturing-case-study/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Toyota Motor Manufacturing." May 20, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/toyota-motor-manufacturing-case-study/.

The marketplace for case solutions.

Toyota Motor Manufacturing, U.S.A., Inc. – Case Solution

Doug Friesen, the manager of assembly for the Toyota Motor Manufacturing plant in Georgetown, Kentucky was facing a huge problem regarding its car seats. Several of their cars came up with either having defective seats or without any seat at all. It resulted in employees being engaged to work overtime to resolve the problem but the cause of the problem cannot be identified. Without identifying the cause, the company cannot come up with an appropriate solution.

Kazuhiro Mishina Harvard Business Review ( 693019-PDF-ENG ) September 08, 1992

Case questions answered:

Case study questions answered in the first and second solutions:

- As Doug Friesen, what would you do to address the seat problem at the Toyota Motor Manufacturing, U.S.A. plant? Where would you focus your attention and solution efforts?

- What options exist? What would you recommend for the short-term and long-term? Why?

- Where, if at all, does the current routine for handling defective seats deviate from the principles of the Toyota Production System?

- What is the real problem facing Doug Friesen?

Case study questions answered in the third solution:

- What are the key principles that TPS incorporates? Which ones did they fail to follow?

- What is the cost of a chord pull resulting in a line stoppage of 1 minute? 30 minutes? 60 minutes? What is the value of a chord pull?

- How should Doug Friesen address the seat problem of Toyota Motor Manufacturing Inc.? As Doug Friesen, where would you focus your attention and solution efforts?

Not the questions you were looking for? Submit your own questions & get answers .

Toyota Motor Manufacturing, U.S.A., Inc. Case Answers

You will receive access to three case study solutions! The second and third solutions are not yet visible in the preview.

Q1. As Doug Friesen, what would you do to address the seat problem at Toyota Motor Manufacturing, U.S.A. plant? Where would you focus your attention and solution efforts?

The deteriorating quality of seats continued to be an issue at Toyota Motor Manufacturing, U.S.A., Inc. (T.M.M.) owing to the Just-In-Time policy followed at their end. The problems ranged from the delivery of defective seats to failure in seat replacement for the defective ones.

Changes and proposed solutions are as follows:

- The introduction of numerous variants led to issues in seat quality management as the operations at the end of KFS were initially streamlined and in line with T.M.M.’s goals. Postponement of customization of colors can lead to a reduction in the variants during the production stage and can be customized after the seats pass the quality check.

- Quality Control needs to be performed either at the outbound stage of KFS (as per T.M.M. standards) or at the inbound stage of Toyota Motor Manufacturing, U.S.A.

Instead of keeping the faulty seats on the assembly line, it is better to move to the Code 1 Clinic Area immediately so that the problems in the seat can be identified and rectified. It also helps in the company’s adherence to the Jidoka concept. Adoption of Just-In-Time in the Code 1 Clinic Area for seat reworks as well to reduce the delay in the rework process.

Proper seat assembly needs to be cross-checked at the Inbound stage itself by T.M.M. for special deliveries.

Q2. What options exist? What would you recommend? Why?

The alternatives are as follows:

- Review of available variants to identify if all of them are necessary or not. Reduction in slow-moving variants can streamline the process.

- Toyota Motor Manufacturing, U.S.A. should take up the Quality Control process of KFS in association with KFS’s quality department by providing expertise and developing solutions to match the requisite standards.

- Search for a new supplier who could deliver quality products on Just-In-Time. o Multi-Vendor Policy

- Trend analysis (Exhibit 10) shows an increasing number of Andon Pulls as the month progresses for Rear Seats. The underlying issues have to be identified and rectified.

- Safety Inventory needed to be maintained for Seats so that the delay from the supplier wouldn’t affect the T.M.M.’s production cycle.

Recommendation : Out of the alternatives mentioned above, we would suggest Toyota Motor Manufacturing, U.S.A…

Unlock Case Solution Now!

Get instant access to this case solution with a simple, one-time payment ($24.90).

After purchase:

- You'll be redirected to the full case solution.

- You will receive an access link to the solution via email.

Best decision to get my homework done faster! Michael MBA student, Boston

How do I get access?

Upon purchase, you are forwarded to the full solution and also receive access via email.

Is it safe to pay?

Yes! We use Paypal and Stripe as our secure payment providers of choice.

What is Casehero?

We are the marketplace for case solutions - created by students, for students.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Learning to Lead at Toyota

- Steven Spear

Toyota’s famous production system makes great cars—and with them great managers. Here’s how one American hotshot learned to replicate Toyota’s DNA.

Reprint: R0405E

Many companies have tried to copy Toyota’s famous production system—but without success. Why? Part of the reason, says the author, is that imitators fail to recognize the underlying principles of the Toyota Production System (TPS), focusing instead on specific tools and practices.

This article tells the other part of the story. Building on a previous HBR article, “Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System,” Spear explains how Toyota inculcates managers with TPS principles. He describes the training of a star recruit—a talented young American destined for a high-level position at one of Toyota’s U.S. plants. Rich in detail, the story offers four basic lessons for any company wishing to train its managers to apply Toyota’s system:

- There’s no substitute for direct observation. Toyota employees are encouraged to observe failures as they occur—for example, by sitting next to a machine on the assembly line and waiting and watching for any problems.

- Proposed changes should always be structured as experiments. Employees embed explicit and testable assumptions in the analysis of their work. That allows them to examine the gaps between predicted and actual results.

- Workers and managers should experiment as frequently as possible. The company teaches employees at all levels to achieve continuous improvement through quick, simple experiments rather than through lengthy, complex ones.

- Managers should coach, not fix. Toyota managers act as enablers, directing employees but not telling them where to find opportunities for improvements.

Rather than undergo a brief period of cursory walk-throughs, orientations, and introductions as incoming fast-track executives at most companies might, the executive in this story learned TPS the long, hard way—by practicing it, which is how Toyota trains any new employee, regardless of rank or function.

The Idea in Brief

Many companies try to emulate Toyota’s vaunted production system (TPS), which uses simple real-time experiments to continually improve operations. Yet few organizations garner the hoped-for successes Toyota consistently achieves: unmatched quality, reliability, and productivity; unparalleled cost reduction; sales and market share growth; and market capitalization.

Why the difficulty? Companies take the wrong approach to training leaders in TPS: They rely on cursory introductions to the system, such as plant walk-throughs and classroom orientation sessions. But to truly understand TPS, managers must live it—absorbing it the long, hard way through total immersion training .

The keys to total immersion training? Leadership trainees directly observe people and machines in action—watching for and addressing problems as they emerge. Through frequent, simple experiments—relocating a switch, adjusting computer coding—they test their hypotheses about which changes will create which consequences. And they receive coaching—not answers—from their supervisors.

Total immersion training takes time. No one can assimilate it in just a few weeks or months. But the results are well worth the wait: a cadre of managers who not only embody TPS but also can teach it to others.

The Idea in Practice

The keys to TPS total immersion training:

Direct Observation

Trainees watch employees work and machines operate, looking for visible problems. Example:

Bob Dallis, a talented manager hired for an upper-level position at one of Toyota’s U.S. engine plants, started his training by observing engine assemblers working. He spotted several problems. For example, as one worker loaded gears in a jig that he then put into a machine, he often inadvertently tripped the trigger switch before the jig was fully aligned, causing the apparatus to fault.

Changes Structured as Experiments

Learners articulate their hypotheses about changes’ potential impact, then use experiments to test their hypotheses. They explain gaps between predicted and actual results. Example:

During the first six weeks of his training, Dallis and his group of assembly workers proposed 75 changes—such as repositioning machine handles to reduce wrist strain—and implemented them over a weekend. Dallis and his orientation manager, Mike Takahashi, then spent the next week studying the assembly line to see whether the changes had the desired effects. They discovered that worker productivity and ergonomic safety had significantly improved.

Frequent Experimentation

Trainees are expected to make many quick, simple experiments instead of a few lengthy, complex ones. This generates ongoing feedback on their solutions’ effectiveness. They also work toward addressing increasingly complex problems through experimentation. This lets them make mistakes initially without severe consequences—which increases their subsequent willingness to take risks to solve bigger problems. Example:

During his first three days of training at a Japanese plant, Dallis was asked to simplify a production employee’s job by making 50 improvements—an average of one change every 22 minutes. At first Dallis was able to observe and alter obvious aspects of his workmate’s actions. By the third day, he was able to see the more subtle impact of a new production layout on the worker’s movements. Result? 50 problems identified—35 of which were fixed on the spot.

Managers as Coaches

Learners’ supervisors serve as coaches, not problem solvers. They teach trainees to observe and experiment. They also ask questions about proposed solutions and provide needed resources. Example:

Takahashi showed Dallis how to observe workers to spot instances of stress and wasted effort. But he never suggested actual process improvements. He also gave Dallis resources he needed to act quickly—such as the help of a worker who moved equipment and relocated wires so Dallis could test as many ideas as possible.

Toyota is one of the world’s most storied companies, drawing the attention of journalists, researchers, and executives seeking to benchmark its famous production system. For good reason: Toyota has repeatedly outperformed its competitors in quality, reliability, productivity, cost reduction, sales and market share growth, and market capitalization. By the end of last year it was on the verge of replacing DaimlerChrysler as the third-largest North American car company in terms of production, not just sales. In terms of global market share, it has recently overtaken Ford to become the second-largest carmaker. Its net income and market capitalization by the end of 2003 exceeded those of all its competitors. But those very achievements beg a question: If Toyota has been so widely studied and copied, why have so few companies been able to match its performance?

- SS Steven Spear is a senior lecturer at MIT’s Sloan School of Management and a senior fellow at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement.

Partner Center

Smart. Open. Grounded. Inventive. Read our Ideas Made to Matter.

Which program is right for you?

Through intellectual rigor and experiential learning, this full-time, two-year MBA program develops leaders who make a difference in the world.

A rigorous, hands-on program that prepares adaptive problem solvers for premier finance careers.

A 12-month program focused on applying the tools of modern data science, optimization and machine learning to solve real-world business problems.

Earn your MBA and SM in engineering with this transformative two-year program.

Combine an international MBA with a deep dive into management science. A special opportunity for partner and affiliate schools only.

A doctoral program that produces outstanding scholars who are leading in their fields of research.

Bring a business perspective to your technical and quantitative expertise with a bachelor’s degree in management, business analytics, or finance.

A joint program for mid-career professionals that integrates engineering and systems thinking. Earn your master’s degree in engineering and management.

An interdisciplinary program that combines engineering, management, and design, leading to a master’s degree in engineering and management.

Executive Programs

A full-time MBA program for mid-career leaders eager to dedicate one year of discovery for a lifetime of impact.

This 20-month MBA program equips experienced executives to enhance their impact on their organizations and the world.

Non-degree programs for senior executives and high-potential managers.

A non-degree, customizable program for mid-career professionals.

Teaching Resources Library

Operations Management

Toyota Supplier Relations: Fixing the Suprima Chassis

Charles Fine

Donald Rosenfield

Jamie Bonini

Apr 24, 2017

In late 2004, Walt Bernstein, the director of production control for Toyota Motor Manufacturing’s Macon, Georgia operation, was notably frustrated with the plant manager for ChassisCo, a Toyota supplier. There were quality and conformance issues with the rear suspension cradle that ChassisCo was manufacturing for Toyota’s new Suprima crossover. ChassisCo had made a number of operational improvements since production started 14 months earlier, but problems continued to surface. Bernstein, an expert in Toyota’s production principles, needed to figure out what to do.

Learning Objectives

To encourage students to think about how best to structure a supplier relationship that will be able to continually address new challenges and change.

Appropriate for the Following Course(s)

operations management; operations strategy

Toyota Supplier Relations: Fixing the Suprima Chassis

teaching note*

*TEACHING NOTES AND SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIALS ARE ONLY AVAILABLE TO EDUCATORS WHO HOLD TEACHING POSITIONS AT ACADEMIC INSTITUTIONS.

- Search for:

Home Resources Case studies Toyota

Few companies have as solid a reputation for supplier relationship management as Toyota does. The world’s biggest auto maker has developed longterm, collaborative and close partnerships with its key Japanese suppliers over a period of several decades. In its European operations, like those of North America, supplier relationship management (SRM) is also a major focus area, albeit one with a shorter history.

We asked Jean-Christophe Deville, general manager, purchasing, at Toyota Motor Europe about its approach.

How do you define srm at toyota and how do srm specific activities with strategic suppliers differ from the way you manage supplier relations in general, what impact, if any, has the economic downturn and toyota’s recent quality issues had on your srm activities, what challenges do you face internally from an srm perspective, what other roles does purchasing, and the supplier relationship managers within the function, play in srm, innovation is a key driver of srm at toyota. how do you manage the process of capturing, assessing and either progressing or rejecting supplier ideas and proposals, to date, the financial benefits you’ve achieved from srm activity are relatively small (0-2% of annual spend with each supplier), but you expect these to grow significantly in future. how will you achieve that, toyota generally shares savings with suppliers, typically on a 50:50 basis. why do you consider this important, what do you see as the most important ingredients for success in srm and what should you avoid doing, reports and publications, case studies, newsletter sign-up, stay connected on linkedin, lang: en_us, enjoy customer of choice benefits.

Find out what your key suppliers really think of you and how to become their customer of choice.

Find out more

Stay in touch

2020 global srm research report - supplier management at speed..

Now in its 12th year, this year we have seen an increase of 29% in the number of companies responding compared to 2019. In addition, the proportion of respondents at CPO/EVP level or equivalent has increased to over 50%. Learn how now, more than ever before, procurement has the opportunity to make the case for SRM to ensure organisations don’t just survive but thrive.

Sign up below to get our insight emails direct to your inbox.

COMMENTS

Toyota a sustainable brand name and a market leader position. 7 3.3. SWOT Analysis Strengths: Strong market position and brand recognition: Toyota has a strong market position in different geographies across the world. The company's market share for Toyota and Lexus brands, (excluding mini vehicles) in Japan was 45.5% in FY2012.

Case Summary: Toyota Motor Corporation was instituted within the year 1937 in Japan. it's twelve plants in Japan also as fifty-four producing corporations in 27countries; it additionally markets its vehicles in additional than one hundred sixty countries worldwide. within the year 2010. and respect for folks.

Summary. Toyota has fared better than many of its competitors in riding out the supply chain disruptions of recent years. But focusing on how Toyota had stockpiled semiconductors and the problems ...

Stable and paranoid, systematic and experimental, formal and frank: The success of Toyota, a pathbreaking six-year study reveals, is due as much to its ability to embrace contradictions like these ...

In August, 2009, the improper installation of an all-weather floor mat from an SUV into a loaner Lexus sedan by a dealer led to the vehicle's accelerator getting stuck, causing a tragic, fatal ...

This paper focuses on the effectiveness of corporate strategy in making engineering organizations successful with a specific case study of Toyota Motors Corporation. The Study uses two approaches ...

Case Study Analysis of Toyota Company Course Code: MGT Course Title: Strategic Management Section- 05 Group- 05 Fall 2021 Prepared For Dr. Rumana Afroze Assistant Professor Department of Business Administration East West University Prepared By Name ID. Tanvir Ahmed 2017-1-10- MD. Ibrahim Khalid 2017-2-10-

T oyota Quality System case study. Introduction. T oyota from the early 1960s alongside their supplier network consolidated the way in which. they were able to refine their production system ...

In this paper, the. Toyota is selected as a special case to illustrate the points that how to impl ement the big data. techniques into supply chain management. According to the analysis, it ...

The Toyota Corporation case study report is based on the implementation of total quality management (TQM) meant to improve the overall performance and operations of this automobile company. TQM involves the application of quality management standards to all elements of the business. We will write a custom essay on your topic.

Crisis management is the process that a business goes through when dealing with an emergency situation. This lesson will focus on a situation Toyota faced which demanded crisis management. We will ...

Aug 18, 2021 • 7 min read. In the early 1980's GM's Fremont plant was one of the worst-performing plants in the company. The labor force was also considered to be the worst in the entire auto industry. Absenteeism was over 20%. Sometimes so few people showed up, they would have to pull people from a local bar to start the assembly line.

On May 1, 1992, Doug Friesen, manager of assembly for Toyota's Georgetown, Kentucky, plant, faces a problem with the seats installed in the plant's sole product--Camrys. A growing number of cars are sitting off-line with defective seats or are missing them entirely. This situation is one of several causes of recent overtime, yet neither the reason for the problem nor a solution is readily ...

Decoding the DNA of the Toyota Production System. by. Steven Spear. and. H. Kent Bowen. From the Magazine (September-October 1999) Summary. The Toyota production system is a paradox. On the one ...

Unlock Case Solution Now! Get instant access to this case solution with a simple, one-time payment ($24.90). You'll be redirected to the full case solution. You will receive an access link to the solution via email. This case study looks into the causes of the accelerator crisis and how well Toyota addressed the said crisis.

What would be done to address quality ("seat" problem)-Doug Friesen. The "seat" problem in Toyota Motor Manufacturing (TMM) Company requires immediate resolution. As evident from the case provided, the condition is worsening and might hinder the productivity of TMM. The company upholds the aspects quality and competitiveness.

Another unplanned ''disaster'' hit Toyota in 2011. It was the magnitude nine East Japan earthquake and tsunami. The Tohoku region is an auto making center that suffered great damage and loss of life.

Unlock Case Solution Now! Get instant access to this case solution with a simple, one-time payment ($24.90). You'll be redirected to the full case solution. You will receive an access link to the solution via email. Doug Friesen, manager of assembly for one of Toyota Motor Manufacturing plant, was facing a huge problem.

Short Summary. The Toyota organizational structure before 2013 was typical of the standard Japanese business model. It was hierarchical and very centralized, and all decisions were made at the ...

Summary. Reprint: R0405E. Many companies have tried to copy Toyota's famous production system—but without success. Why? Part of the reason, says the author, is that imitators fail to recognize ...

In late 2004, Walt Bernstein, the director of production control for Toyota Motor Manufacturing's Macon, Georgia operation, was notably frustrated with the plant manager for ChassisCo, a Toyota supplier. There were quality and conformance issues with the rear suspension cradle that ChassisCo was manufacturing for Toyota's new Suprima crossover. ChassisCo had made a number of operational ...

Few companies have as solid a reputation for supplier relationship management as Toyota does. The world's biggest auto maker has developed longterm, collaborative and close partnerships with its key Japanese suppliers over a period of several decades. In its European operations, like those of North America, supplier relationship management (SRM) is also a major focus area, albeit one with a ...

Toyota Case Study Summary. 1749 Words4 Pages. Recommended: History of Toyota. Chapter 1 1. Toyota Motor Corporation 1.1 Corporate Overview Toyota Motor Corporation is one of the bigger automobile industries in the world, located in Toyota, Aichi, Japan. This corporation was founded in 1937 by the Toyoda family.