A collective case study of nursing students with learning disabilities

Affiliation.

- 1 Franciscan University of Steubenville, Steubenville, Ohio, USA. [email protected]

- PMID: 14535146

This collective case study described the meaning of being a nursing student with a learning disability and examined how baccalaureate nursing students with learning disabilities experienced various aspects of the nursing program. It also examined how their disabilities and previous educational and personal experiences influenced the meaning that they gave to their educational experiences. Seven nursing students were interviewed, completed a demographic data form, and submitted various artifacts (test scores, evaluation reports, and curriculum-based material) for document analysis. The researcher used Stake's model for collective case study research and analysis (1). Data analysis revealed five themes: 1) struggle, 2) learning how to learn with LD, 3) issues concerning time, 4) social support, and 5) personal stories. Theme clusters and individual variations were identified for each theme. Document analysis revealed that participants had average to above average intellectual functioning with an ability-achievement discrepancy among standardized test scores. Participants noted that direct instruction, structure, consistency, clear directions, organization, and a positive instructor attitude assisted learning. Anxiety, social isolation from peers, and limited time to process and complete work were problems faced by the participants.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Adaptation, Psychological*

- Attitude of Health Personnel*

- Disabled Persons / education

- Disabled Persons / psychology*

- Education, Nursing, Baccalaureate / methods

- Education, Nursing, Baccalaureate / standards*

- Education, Special

- Educational Status

- Faculty, Nursing / standards

- Interprofessional Relations

- Learning Disabilities / psychology*

- Needs Assessment

- Nursing Education Research

- Self Efficacy

- Social Support

- Students, Nursing / psychology*

- Surveys and Questionnaires

- Teaching / methods

- Teaching / standards

A collective case study of nursing students with learning disabilities.

- MLA style: "A collective case study of nursing students with learning disabilities.." The Free Library . 2003 National League for Nursing, Inc. 17 May. 2024 https://www.thefreelibrary.com/A+collective+case+study+of+nursing+students+with+learning...-a0108649337

- Chicago style: The Free Library . S.v. A collective case study of nursing students with learning disabilities.." Retrieved May 17 2024 from https://www.thefreelibrary.com/A+collective+case+study+of+nursing+students+with+learning...-a0108649337

- APA style: A collective case study of nursing students with learning disabilities.. (n.d.) >The Free Library. (2014). Retrieved May 17 2024 from https://www.thefreelibrary.com/A+collective+case+study+of+nursing+students+with+learning...-a0108649337

Terms of use | Privacy policy | Copyright © 2024 Farlex, Inc. | Feedback | For webmasters |

Type your tag names separated by a space and hit enter

A collective case study of nursing students with learning disabilities. Nurs Educ Perspect . 2003 Sep-Oct; 24(5):251-6. NE

This collective case study described the meaning of being a nursing student with a learning disability and examined how baccalaureate nursing students with learning disabilities experienced various aspects of the nursing program. It also examined how their disabilities and previous educational and personal experiences influenced the meaning that they gave to their educational experiences. Seven nursing students were interviewed, completed a demographic data form, and submitted various artifacts (test scores, evaluation reports, and curriculum-based material) for document analysis. The researcher used Stake's model for collective case study research and analysis (1). Data analysis revealed five themes: 1) struggle, 2) learning how to learn with LD, 3) issues concerning time, 4) social support, and 5) personal stories. Theme clusters and individual variations were identified for each theme. Document analysis revealed that participants had average to above average intellectual functioning with an ability-achievement discrepancy among standardized test scores. Participants noted that direct instruction, structure, consistency, clear directions, organization, and a positive instructor attitude assisted learning. Anxiety, social isolation from peers, and limited time to process and complete work were problems faced by the participants.

Authors +Show Affiliations

Pub type(s).

- Adaptation, Psychological

- Attitude of Health Personnel

- Disabled Persons

- Education, Nursing, Baccalaureate

- Education, Special

- Educational Status

- Faculty, Nursing

- Interprofessional Relations

- Learning Disabilities

- Needs Assessment

- Nursing Education Research

- Self Efficacy

- Social Support

- Students, Nursing

- Surveys and Questionnaires

Related Citations

- Student's perceptions of effective clinical teaching revisited.

- EN to RN: the transition experience pre- and post-graduation.

- Case seminars open doors to deeper understanding - Nursing students' experiences of learning.

- Analyzing the teaching style of nursing faculty. Does it promote a student-centered or teacher-centered learning environment?

- The experiences of students with English as a second language in a baccalaureate nursing program.

- An evaluation of fitness for practice curricula: self-efficacy, support and self-reported competence in preregistration student nurses and midwives.

- Preferences for teaching methods in a baccalaureate nursing program: how second-degree and traditional students differ.

- Enacting connectedness in nursing education: moving from pockets of rhetoric to reality.

- Nursing students' and tutors' perceptions of learning and teaching in a clinical skills centre.

- An analysis of clinical teacher behaviour in a nursing practicum in Taiwan.

A Student Nurse Experience of Learning Disability Nursing

This week our EBN Blog Series has focused on Learning Disability with thought-provoking blogs from Professor Ruth Northway , on nursing older people with learning disabilities and Nurse Consultant Jonathan Beebee , on the future of learning disability nursing . Today we are delighted to share the student nurse perspective on learning disability nursing from student nurse Amy Wixey , a rising star from the University of Chester .

I remember my first day like it was yesterday, as a student Learning Disability nurse. That day was the most exciting and the most nerve-racking day of my life. Now I can’t believe that it has been two years and 3 months since that day, what an incredible journey it has been. I have had a wealth of experience since then.

I am currently in my 3 rd year at the University of Chester, my first choice since the beginning of my UCAS application. It’s scary to think that it has been three years since I was attending open days and writing my personal statement. I fell in love with Chester from the moment I went to their open day, coming from a small town, the University’s friendly community is what made me want to study here. The city isn’t too overwhelming but then it isn’t too small, which was perfect for me.

Before coming into Learning Disability nursing I thought I had an idea of what my course would entail as my mother is a Registered Learning Disability Nurse and has been for over 30 years now. Her vast knowledge and my childhood memories of visiting her at work gave me the building blocks to what I already knew would be a fantastic career.

To date I have been on four 10 week placements, these have been within the NHS and the private sector. All these placements have been valuable to me, they have allowed me to work with a number of professionals not just the Learning Disability Nurse. Placements have allowed me to see the importance of Multi-Disciplinary Team working and person centred care, these two approaches have shown that, if used correctly, they can lead the way in ensuring an individual can achieve the best quality of life.

Since the beginning of my degree, I have gained part time employment with a company that specialises in supported living for individuals with a Learning Disability and Mental Health problems. Their philosophy “Delivering on your potential” has given the opportunities for me to practice what I believe. Individuals with Learning Disabilities should have the right to deliver on their potential, with the support from dedicated staff. Working part time has allowed me to develop my skills further while I am not on placements with the University, in which I am grateful for.

Through all the highs there have also been lows. If I have ever had a bad day, I put it down to experience and reflected on the situation that had happened. I have also made friends who I know will stay with me for the rest of my life. They have encouraged me and supported me, like I have with them all the way. One thing I have learnt to do is to not worry, the good days outweigh the bad days by far. A simple “thank you for listening to me” made my heart smile.

If I could give any key lessons to remember as you enter this new stage of your life.

- Never do something you are unsure of. Always ask questions, it is better to ask.

- Ensure you reflect. Reflecting allows you to look back on the situation, see what could be done better, what was done well.

- Try not to put pressure on yourself, just try your best. Be proud.

- Respect health care assistants, they know the area they are working in, don’t be afraid to utilise them.

- Don’t be afraid to get upset. Just choose your moment, we all have bad days, it’s important to acknowledge that.

- Most of all treat people the way you or your family would like to be treated.

Amy Wixey , 3rd Year Learning Disability Student Nurse, University of Chester .

Check out EBN’s own top 5 recommended resources on Learning Disability below:

- Chue, P. (2014) ‘In adults with intellectual disability, discontinuation of antipsychotics is associated with reduction in weight, BMI, waist circumference and blood pressure’, Evidence-Based Nursing, 17, (3), pp. 89

- Bressington , D. and Tong-Chien, W. (2015) ‘ Case study : Guidelines improve nurses’ knowledge and confidence in diagnosis of anxiety and challenging behaviours in people with intellectual disabilities’, Evidence-Based Nursing, Published Ahead of Print doi:10.1136/eb-2015-102168

- EBN Podcast with Professor Chue on intellectual disability and antipsychotic medication.

- Balandin, S. (2008) ‘Inpatients with cerebral palsy and complex communication needs identified barriers to communicating with nurses’, Evidence-Based Nursing, 11, (1), pp. 30.

- EBN Guest Blog by Carole Beighton on Parenting Children with Intellectual Disabilities

Comment and Opinion | Open Debate

The views and opinions expressed on this site are solely those of the original authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of BMJ and should not be used to replace medical advice. Please see our full website terms and conditions .

All BMJ blog posts are posted under a CC-BY-NC licence

BMJ Journals

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Baksh RA, Pape SE, Smith J, Strydom A. Understanding inequalities in COVID-19 outcomes following hospital admission for people with intellectual disability compared to the general population: a matched cohort study in the UK. BMJ Open. 2021; 11:(10) https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052482

Binda F, Marelli F, Galazzi A, Pascuzzo R, Adamini I, Laquintana D. Nursing management of prone positioning in patients with COVID-19. Crit Care Nurse. 2021; 41:(2)27-35 https://doi.org/10.4037/ccn2020222

Brown M, MacArthur J, McKechanie A, Mack S, Hayes M, Fletcher J. Learning Disability Liaison Nursing Services in south-east Scotland: a mixed-methods impact and outcome study. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2012; 56:(12)1161-1174 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2011.01511.x

Brown M, Chouliara Z, MacArthur J The perspectives of stakeholders of intellectual disability liaison nurses: a model of compassionate, person-centred care. J Clin Nurs. 2016; 25:(7-8)972-982 https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13142

Bur J, Missen K, Cooper S. The impact of intellectual disability nurse specialists in the United Kingdom and Eire Ireland: an integrative review. Nurs Open. 2021; 8:(5)2018-2024 https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.690

Cashin A, Pracilio A, Buckley T A survey of Registered Nurses' educational experiences and self-perceived capability to care for people with intellectual disability and/or autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability. 2022; 47:(3)227-239 https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2021.1967897

Chicoine C, Hickey EE, Kirschner KL, Chicoine BA. Ableism at the bedside: people with intellectual disabilities and COVID-19. J Am Board Fam Med. 2022; 35:(2)390-393 https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2022.02.210371

Couper K, Murrells T, Sanders J The impact of COVID-19 on the wellbeing of the UK nursing and midwifery workforce during the first pandemic wave: A longitudinal survey study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2022; 127 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.104155

Cummins L, Ebyarimpa I, Cheetham N, Tzortziou Brown V, Brennan K, Panovska-Griffiths J. Factors associated with COVID-19 related hospitalisation, critical care admission and mortality using linked primary and secondary care data. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2021; 15:(5)577-588 https://doi.org/10.1111/irv.12864

Equality and Human Rights Commission. What are reasonable adjustments?. 2023. https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/en/advice-and-guidance/what-are-reasonable-adjustments (accessed 30 August 2023)

Henderson A, Fleming M, Cooper SA COVID-19 infection and outcomes in a population-based cohort of 17 203 adults with intellectual disabilities compared with the general population. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2022; 76:(6)550-555 https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2021-218192

Javaid A, Nakata V, Michael D. Diagnostic overshadowing in learning disability: think beyond the disability. Progress in Neurology and Psychiatry. 2019; 23:(2)8-10 https://doi.org/10.1002/pnp.531

Koyama AK, Koumans EH, Sircar K Severe outcomes, readmission, and length of stay among COVID-19 patients with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Int J Infect Dis. 2022; 116:328-330 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2022.01.038

Louch G, Albutt A, Harlow-Trigg J Exploring patient safety outcomes for people with learning disabilities in acute hospital settings: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2021; 11:(5) https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047102

MacArthur J, Brown M, McKechanie A, Mack S, Hayes M, Fletcher J. Making reasonable and achievable adjustments: the contributions of learning disability liaison nurses in ‘Getting it right’ for people with learning disabilities receiving general hospitals care. J Adv Nurs. 2015; 71:(7)1552-1563 https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12629

McCallum L, Rattray J, Pollard B The CANDID Study: impact of COVID-19 on critical care nurses and organisational outcomes: implications for the delivery of critical care services. A questionnaire study before and during the pandemic. 2022; https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.16.22282346

McCormick F, Marsh L, Taggart L, Brown M. Experiences of adults with intellectual disabilities accessing acute hospital services: A systematic review of the international evidence. Health Soc Care Community. 2021; 29:(5)1222-1232 https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13253

Mencap. Getting it right charter: see the person, not the disability. 2016. https://tinyurl.com/ykumt3mh (accessed 23 August 2023)

Miranda F, Arevalo-Rodriguez I, Díaz G Confusion Assessment Method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU) for the diagnosis of delirium in adults in critical care settings. Protocol for review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018; 2018:(9) https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013126

Moloney M, Hennessy T, Doody O. Reasonable adjustments for people with intellectual disability in acute care: a scoping review of the evidence. BMJ Open. 2021; 11:(2) https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039647

Moloney M, Hennessy T, Doody O. Parents' perspectives on reasonable adjustments in acute healthcare for people with intellectual disability: A qualitative descriptive study. J Adv Nurs. 2023; https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15772

Montgomery CM, Humphreys S, McCulloch C, Docherty AB, Sturdy S, Pattison N. Critical care work during COVID-19: a qualitative study of staff experiences in the UK. BMJ Open. 2021; 11:(5) https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048124

Project report: understanding the who, where and what of learning disability liaison nurses. 2020. https://tinyurl.com/aw6p27sp (accessed 23 August 2023)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE impact: people with a learning disability. NICE impact report. 2021. https://tinyurl.com/yzvz7p6v (accessed 23 August 2023)

Scottish Executive. Promoting health, supporting inclusion. The national review of the contribution of all nurses and midwives to the care and support of people with learning disabilities. 2002. https://www.scot.nhs.uk/sehd/mels/HDL2002_59report.pdf (accessed 23 August 2023)

Seale J. The role of supporters in facilitating the use of technologies by adolescents and adults with learning disabilities: a place for positive risk-taking?. European Journal of Special Needs Education. 2014; 29:(2)220-236 https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2014.906980

Totsika V, Emerson E, Hastings RP, Hatton C. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health of adults with intellectual impairment: evidence from two longitudinal UK surveys. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2021; 65:(10)890-897 https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12866

Tyrer F, Kiani R, Rutherford MJ. Mortality, predictors and causes among people with intellectual disabilities: A systematic narrative review supplemented by machine learning. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability. 2021; 46:(2)102-114 https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2020.1834946

Learning from Lives and Deaths - People with a learning disability and autistic people (LeDeR) report for 2021. 2022. https://www.kcl.ac.uk/research/leder (accessed 23 August 2023)

Williamson EJ, McDonald HI, Bhaskaran K Risks of covid-19 hospital admission and death for people with learning disability: population based cohort study using the OpenSAFELY platform. BMJ. 2021; 374 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n1592

Wilson NJ, Pracilio A, Kersten M Registered nurses' awareness and implementation of reasonable adjustments for people with intellectual disability and/or autism. J Adv Nurs. 2022; 78:(8)2426-2435 https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15171

Person-centred critical care for a person with learning disability and COVID-19: case study of positive risk taking

Penny Clarke

Senior Charge Nurse, Intensive Care Unit, Western General Hospital, NHS Lothian, Edinburgh

View articles · Email Penny

Rachel Brannan

Learning Disability Liaison Nurse, NHS Lothian, Edinburgh

View articles

Scott Taylor

Consultant Nurse Learning Disabilities, NHS Lothian, Edinburgh

Juliet MacArthur

Chief Nurse Research and Development, NHS Lothian, Edinburgh

People with learning disabilities are known to experience a wide range of health inequalities and have a lower life expectancy than the general population. During the COVID-19 pandemic this extended to higher mortality rates following infection with the novel coronavirus. This case study presents an example of a positive outcome for Jade, a 21-year-old woman with learning disabilities and autism who required a long period in intensive care following COVID-19 infection. It demonstrates the impact of effective multidisciplinary collaboration involving the acute hospital learning disability liaison nurse and Jade's family, leading to a wide range of reasonable and achievable adjustments to her care.

This case study focuses on Jade, a 21-year old woman who contracted COVID-19 in December 2021 and was in hospital for around 4 months, including 68 days being ventilated in an intensive care unit (ICU). Jade's health needs were compounded by having learning disabilities and autism, and this case study illuminates the effective multidisciplinary collaboration between critical care staff and the acute hospital learning disability liaison nurse (AHLDLN) that led to an eventual positive outcome for Jade. It aims to illustrate the complexity of Jade's physical, social, emotional and cognitive health needs during the acute and recovery phases of her illness, and the extensive reasonable adjustments made to support her and her family's needs. It presents the perspective of both the critical care and learning disability liaison nurses and draws on their reflections from this experience.

From the initial identification of COVID-19 as a disease caused by a novel, highly contagious virus (SARS-CoV-2) presenting a global public health emergency, people with learning disabilities experienced higher rates of infection, symptom complications, and mortality ( Williamson et al, 2021 ). During the first wave of COVID-19 in the UK, mortality rates for people with learning disabilities were six times higher than those in the general population, and at the end of 2021 (following the introduction of vaccination) they remained three times higher ( Henderson et al, 2022 ). Furthermore, analysis undertaken by Learning from Lives and Deaths (LeDeR), a service improvement programme for people with a learning disability and autistic people at King's College London, identified that during 2021 the rate of excess deaths was more than two times higher for people with a learning disability compared with the general population ( White et al, 2022 ).

People with learning disabilities are known to experience high levels of pervasive health inequalities and poorer health outcomes than the general population ( Tyrer et al, 2021 ). The main causes of death in people with a learning disability in 2021 were COVID-19, diseases of the circulatory system, diseases of the respiratory system, cancers, and diseases of the nervous system ( White et al, 2022 ). Despite improvements in the evidence base on these health inequalities resulting in targeted policy and service delivery, life expectancy for people with learning disabilities remains significantly reduced, and is lower than the general population by 23 years for males and 27 years for females ( National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2021 ). Moreover, 46% of people with learning disabilities live with between seven and ten comorbidities ( NICE, 2021 ).

In terms of COVID-19 infection, the underpinning risk factors for people with learning disabilities are multi-faceted and unique to each individual. Given a higher incidence of comorbidities, including diabetes, obesity and respiratory conditions, it was believed that these factors have led to the higher mortality rates. However, it is also argued that underlying assumptions made by clinicians about people with learning disabilities have often presented a higher risk ( Chicoine et al, 2022 ). This is due to diagnostic overshadowing and disability bias or ableism, which can lead to expectations of poorer outcomes, rather than a rights-based expectation to intervene, escalate, and seek recovery as an outcome ( Totsika et al, 2021 ). Diagnostic overshadowing refers to the missatribution of symptoms arising from physical or mental health problems to an individual's learning disability, leading to delayed diagnosis and treatment ( Javaid et al, 2019 ). Examples include attributing a confused state to a person's learning disability rather than infection, dehydration or medication side effects.

A range of underlying non-medical factors also impacted people with learning disabilities in both the prevention and treatment of COVID-19 infection. These include health literacy and the ability to follow population-wide guidance on protective measures, the need for supported care with involvement of a team of staff, the ability to tolerate invasive and stress-inducing interventions such as wearing face masks or an oxygen mask during treatment, and understanding and tolerating the need to isolate within the home, or to remain in a hospital bed or room ( Baksh et al, 2021 ; Cummins et al, 2021 ).

Across the health pathway, people with learning disabilities are also vulnerable to not being able to tolerate established, standardised processes and procedures, which may in turn reduce their chances for successful recovery ( Koyama et al, 2022 ). People with a learning disability and/or autism often have sensory perception and processing difficulties – involving lighting, noise, touch and smells – that can lead to feelings of being overwhelmed, confused or distressed. Putting reasonable adjustments in place based on individual need is a legal duty set out within the Equality Act 2010. Reasonable adjustments include making adaptations to communication methods, processes, procedures and interventions; examples include changing the time of an appointment to avoid a long period of waiting, creating accessible information in easy-read format, and reducing sensory overload by removal of unnecessary equipment. There is evidence that such adjustments make health care accessible for people with learning disabilities by addressing potential barriers, which enable equity of access, and uphold safety ( Moloney et al, 2021 ). However, it is important to recognise that adjustments and deviations from standardised practice can elevate risk and therefore demand careful and expert planning and management, with measured variations that are safe and achievable ( Louch et al, 2021 ). This is where the AHLDLN role brings clinical expertise to support teams to put reasonable adjustments in place and build a compassionate, person-centred model of care to enable the best outcomes ( Brown et al, 2016 ; Wilson et al, 2022 ).

In 1999 NHS Lothian was the first health service in the UK to introduce the role of the AHLDLN, with this initiative being subsequently endorsed in Scottish health policy ( Scottish Executive, 2002 ) and recommended by Mencap (2016) in the Getting it Right charter and campaign. Over successive years, the role has been firmly established as an integral component of the support infrastructure in acute hospitals and has been introduced across the UK and Ireland. There is a growing evidence base to demonstrate its value and impact on patient outcomes through educational interventions, influencing policy, and supporting reasonable adjustments at both individual and organisational level ( Moulster, 2020 ; Bur, et al, 2021 ). The main elements of the role of the AHLDLN were identified through a mixed methods research study undertaken by Brown et al (2012) and are identified in Table 1 . Key to the success of AHLDLNs is their leadership, influencing and enabling skills to support teams to deliver safe, effective, person-centred care to patients and their families ( MacArthur et al, 2015 ).

Patient overview

At the time of this case study, Jade was living in Edinburgh with her family, having moved there from Poland when she was 13 years old. Jade was diagnosed with a severe learning disability and autistic spectrum disorder at a very young age. She experiences significant anxiety in unfamiliar settings and, alongside her communication difficulties, this can lead to expressions of distress including self-injurious behaviours. Jade had no known comorbidities and this was her first admission to hospital. Both Jade's and her mother's first language is Polish, and although they both understand English, Jade is non-verbal and is supported to communicate using symbols and familiar objects. Jade enjoys using her iPad to listen to Polish music and to watch videos, with trams travelling through her home town in Poland being a particular favourite.

Jade tested positive for COVID-19 in December 2021 and 2 days later, following GP assessment, she was attended to by paramedics in order to transfer her to hospital for assessment. Given Jade's distress at the sensory overload and anxiety caused by her situation, the paramedics were with her at home for 4 hours, before they could safely move her to the ambulance, following administration of lorazepam (for her anxiety). On admission to hospital her clinical condition was recorded as being ‘mildly unwell’, with no sign of using accessory muscles that would have indicated respiratory compromise, and with peripheral oxygen saturation of 87% on air. However, Jade's level of distress was high and assessment by the intensive care unit (ICU) team was that further invasive investigations (such as chest X-ray) at this stage would mean she would need to be sedated and ventilated, which was felt not to be in her best interests, given her presenting symptoms. She settled overnight in a quiet single room with her mother present and in the morning her oxygen saturation levels had risen to 96% on air. Following consultation with Jade's mother there was agreement that she would be best cared for in her familiar home environment. Unfortunately, 5 days later her condition worsened with acute breathlessness and on re-admission to hospital her oxygen saturations were 67%. In spite of Jade's deteriorating condition, she was not able to tolerate the urgent need for oxygen therapy and the decision was made that admission to ICU would best ensure her needs were met. Given the urgency of the situation and Jade's experience of sensory overload in an unfamiliar environment, including multiple staff members wearing full personal protective equipment (PPE), she manifested her anxiety and distress in the form of physical aggression towards herself and the health care staff.

Making reasonable adjustments in a critical situation

With the situation becoming increasingly critical and potentially life-threatening for Jade, due to the risk of hypoxic cardiac arrest, and in the face of unfamiliar territory in their experience of treating someone with a learning disability with this level of COVID-19 hypoxia who was exhibiting high levels of distress, the ICU team recognised the need to make significant and immediate reasonable adjustments. These included some staff removing certain items of PPE in order that Jade could more easily relate to them and the decision to administer a sedative in a hospital corridor, rather than in the controlled environment of the admissions unit. This permitted safe transfer to ICU, where Jade was admitted to a side room, intravenous access was obtained and rapid sequence intubation was performed, thereby stablising her situation.

Jade remained in ICU for 104 days and for a further 16 days in a step-down ward before being discharged home. A summary of key milestones in Jade's admission is presented in Table 2 , with the key critical care nursing priorities detailed in Box 1 . Jade's medical treatment in ICU was complex and included prone positioning ( Binda et al, 2021 ), administration of the broad-spectrum antibiotic Tazocin (piperacillin and tazobactam) and, linked to her prolonged ICU stay, treatment of multiple infections (such as chest, sinus and blood cultures) with numerous antibiotics. Jade experienced two initial failed attempts at extubation, resulting in the need for a tracheostomy.

Box 1.Critical care nursing priorities for Jade

- Treatment of COVID-19 pneumonitis

- Medication management

- Safe sedation management

- Ventilation management

- Prone positioning and associated care – one episode (18 hours)

- Continuation of regular medication regimen, complex with sedation needs

- Frequent sedation holds and assessment of consciousness levels

- Tracheostomy management and safety

- Weaning of ventilation

- Maintaining safety of Jade in a complex, unfamiliar environment

- Providing support to Jade's family

- Involvement in rehabilitation

- Avoiding the cycle of re-sedation

- Avoiding ICU complications

Involvement of the learning disability liaison nurse

An email referral to the AHLDLN was made by the senior charge nurse after Jade had been in ICU for 5 days. Their first meeting took place 3 days later, where in addition to the AHLDLN being able to update the ICU nurses about Jade's known community learning disability support services (which were minimal), she suggested making contact with the paediatric ICU team at another hospital site who had recently cared for someone requiring ventilation who had a learning disability similar to Jade's. This led to valuable discussions between the medical teams regarding pharmaceutical interventions and learning disability psychiatrist's advice on Jade's anticipated behavioural support needs when she regained consciousness and was extubated.

Throughout Jade's period of care in ICU the nursing team liaised with the AHLDLN to ensure that appropriate reasonable adjustments were made to ensure that her needs were met effectively (summarised in Box 2 ). Jade's care also involved the dedicated critical care recovery team, made up of a medic, nurse, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, dietitian, speech and language therapist, pharmacist and psychologist. Given that ICU has to be a highly controlled environment, and was already significantly affected by the enhanced infection prevention and control requirements associated with COVID-19, many of these adjustments constituted substantial positive risk-taking by the critical care team. Seale (2014) describes positive risk-taking as involving an element of risk in terms of health and safety, but stresses managing that risk rather than avoiding or ignoring it; taking positive risks because the potential benefits outweigh the potential harm.

Box 2.Positive risk-taking and reasonable adjustments in ICUPositive risk-taking

- Removal of personal protective equipment (PPE) during transfer from admission area to ICU

- Allowing Jade's mother access to an otherwise restricted COVID-positive area

- Use of minimal PPE while aerosol-generating procedures were undertaken, to prevent distress

- Readjustment of sedation expectations

- Minimising monitoring

- Weaning ventilation based on Jade's peripheral saturations instead of via an invasive arterial line

Reasonable adjustments

- Jade being placed in side room in quiet area of unit to facilitate a calm environment

- Early use of iPad for calming/reassuring music/sounds

- Early movement of Jade into a cubicle to provide calm environment to prevent distress

- Adjustment of critical care assessment tools – Confusion Assessment Method (CAM-ICU) ( Miranda et al, 2018 ) not appropriate in this situation

- Extensive multidisciplinary team involvement to facilitate daily gym sessions – including Jade's mother, AHLDLN, physiotherapist, physiotherapy assistant, occupational therapist and at least one bedside nurse

- Reducing equipment in the immediate environment where possible

Meeting Jade's communication needs

Over and above Jade's critical care nursing needs, the main nursing and critical care recovery team's priorities were to provide support to her family and secure their full involvement in assessing Jade's baseline needs and preparing for future reasonable adjustments to maximise her potential for recovery. The initial meeting of the AHLDLN with Jade's mother and aunt took place in the ICU family room, with no time pressures in order to be able to explain Jade's situation and seek their involvement in completion of the ‘My Important Health Information’ (MIHI) document to enable the ICU staff to more fully understand Jade as a person. A key section of the MIHI document focused on Jade's communication needs, particularly given that English was not her first language, and preparation for the use of appropriate symbols and clarification of a basic timetable in words that Jade would understand to indicate the sequence of events. The AHLDLN also contacted the community speech and language therapist to explore her previous input with Jade.

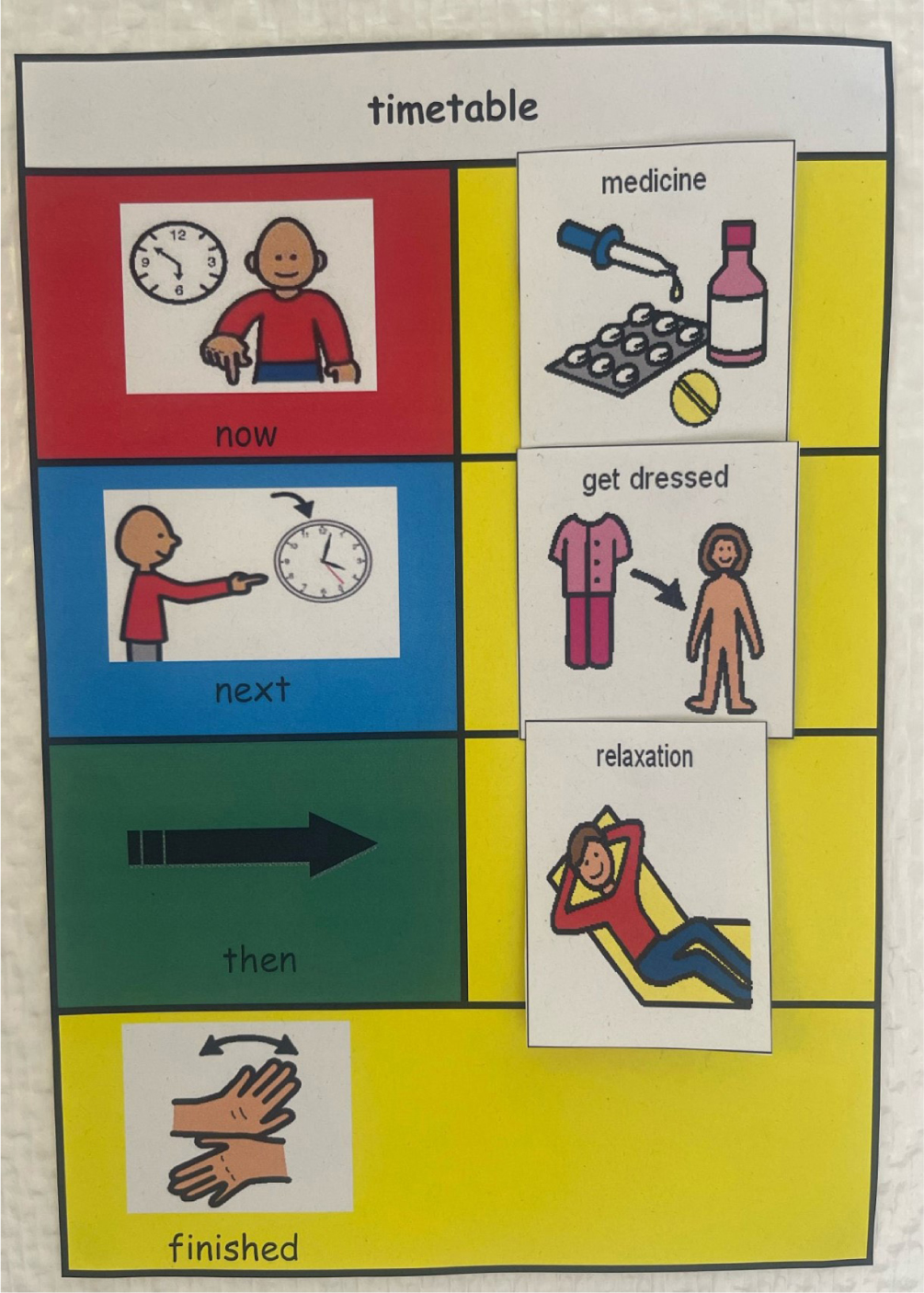

Jade's mother and the AHLDLN worked together to develop a list of appropriate symbols required for the ICU environment; for example, ‘nurse’, ‘physio’, ‘medication’, ‘suction’, ‘blood pressure’, ‘turning over’, ‘iPad’, ‘TV’ and items around personal care. Symbols were sourced from the Boardmaker (Tobii Dynavox) picture library for augmented communication. They settled on a symbol format around a timetable of ‘Now’, ‘Next’, ‘Then’ and ‘Finished’ and also agreed on producing much larger laminated symbols so the timetable could be placed on the wall directly opposite Jade's bed ( Figure 1 ). Once Jade was extubated and able to engage with her mother and the nursing staff, it was clear that both the symbols and timetable were being used effectively: for example Jade's mother displayed the ‘brush hair’ symbol and Jade picked a brush up from table and brushed her hair. Further symbols were developed and added as Jade commenced more active rehabilitation with the physiotherapist and occupational therapist; for example, wheelchair, hoist, gym and ‘stand up’ and later food symbols after the removal of her naso-gastric tube.

Jade's needs associated with her learning disability were high priority for the AHLDLN and during the remainder of her admission the AHLDLN identified and addressed a range of nursing priorities, which are summarised in Box 3 . The AHLDLN's involvement extended throughout Jade's admission and during her post-discharge period Jade's mother got in touch for further support and advice regarding community services.

Box 3.Learning disability nursing priorities for Jade

- Building a trusting relationship with Jade and her family

- Liaising with appropriate specialities regarding sedation and ventilation management

- Supporting the family while Jade remained intubated

- Liaising with the ward staff (nursing and medical) to have regular updates on Jade's condition and providing the space to speak openly around concerns or opinions of current care

- Advocating for Jade and her family regarding family involvement in daily care provided

- Emphasising the importance of Jade's environment and the safety she felt in her space

- Encouraging staff to create therapeutic relationships with Jade and her family (especially after the traumatic admission)

- Encouraging positive use of communication aids and allowing the family to lead the education on this to the staff team

- Providing support through documentation to allow Jade's family to explain the importance of knowing Jade to meet her needs

- Being present when required and knowing when to give Jade and her family their space

- Linking with the wider critical care recovery team and community learning disability services

- Encouraging staff to reflect on the reasonable adjustments they made to meet Jade's needs

- Being available when transferring to the ward to maintain consistency for Jade and her family

Supporting Jade's mother

Support for Jade's mother was a priority for both teams of nurses and she required significant reassurance and benefitted from being able to contact the AHLDLN directly by phone and text to raise concerns and ask questions. Jade was eventually transferred to a step-down ward and both she and her mother found this transition difficult, given that it involved a completely new team of staff and a much less intensive level of support. Communication with Jade's mother leading up to this transfer had not been optimal and unfortunately this led to a breakdown in some of the trust that had been previously established with her. The AHLDLN worked closely with the new ward staff team to build the relationship with Jade's mother and ensure reasonable adjustments were made for Jade, where possible. This included getting Jade a low-profile bed to support mobilisation, recommending one-to-one staffing overnight to offer reassurance to Jade and the introduction of further communication symbols to support discharge; for example, bus, shops, walking and reinforcing the names of her community support team. On Jade's day of discharge the AHLDLN met with Jade and her mother to ensure they were happy before leaving hospital and to discuss community support and referrals. The physiotherapist and occupational therapist had taken Jade for a final gym session and encouraged her to appreciate how far she had come and to continue with her physical rehabilitation at home.

This case study has drawn on the collective reflections of the ICU senior charge nurse and the AHLDLN, which have followed a comprehensive multidisciplinary learning review by the critical care team and the learning disability liaison service involving the consultant nurse for learning disabilities. This review highlighted the positive impact of early contact with the AHLDLN as being key to Jade's recovery and the crucial role she played in supporting staff to understand Jade's communication and behavioural needs, leading to effective reasonable adjustments. Jade's discharge from ICU was delayed due to safety concerns, and it was acknowledged that communication with the receiving ward and Jade's mother during this period could have been better, and would have avoided some breakdown in trust between the hospital and family.

There is considerable evidence to demonstrate that adults with learning disabilities experience higher physical and mental health needs when compared with the general population ( Tyrer et al, 2021 ; White et al, 2022 ). Furthermore, previous research has revealed that many people with learning disabilities have negative encounters within acute hospitals, including poorer safety outcomes ( Louch et al, 2021 ). In a recent systematic review of the international evidence on experiences of adults with intellectual disabilities accessing acute hospital services ( McCormick et al, 2021 ) the authors highlighted lack of communication, inadequate information sharing and issues related to compassionate care and respect. Other studies have identified an ongoing sense of nurses feeling unprepared to care for people with a learning disability and/or autism spectrum disorder in mainstream clinical settings ( Cashin et al, 2022 ). There is also evidence that adult registered nurses have relatively low familiarity of the concept of reasonable adjustments ( Wilson et al, 2022 ). It is against this background that Jade's case study provides a positive example of collaborative, rights-based care during one of the most exceptionally challenging periods for UK health services.

Jade's care episode took place during an unprecedented period and the impact of COVID-19 on patients, relatives and healthcare staff cannot be underestimated. There is evidence of the negative psychological impact on the UK nursing and midwifery workforce ( Couper et al, 2022 ). Studies undertaken in ICUs during the early stages of the pandemic revealed significant stress, which was mitigated by strong teamwork, camaraderie, pride and fulfilment ( Montgomery et al, 2021 ). One study of UK critical care nurses who worked between January and November 2021 identified that a third reported probable post-traumatic stress disorder, which was linked to increased job demands, particularly where there was a lack of resources, reduced learning opportunities and a lack of focus on staff wellbeing ( McCallum et al, 2022 ).

A recent integrative review of learning disability nurse specialists in the UK and Ireland ( Bur et al, 2021 ) identified that the central tenets of the role focus on person-centred care, organisational and practice development. One of the papers in this review ( Brown et al, 2012 ) identified seven key elements of the AHLDLN role: advocating, collaborating, communicating, educating, facilitating, influencing and mediating. All elements were clearly shown during Jade's admission and were evident through the AHLDLN's direct involvement with Jade and her mother, promotion of collaboration between different acute services, facilitation of specific care interventions, role modelling and educating the critical care staff with regard to communication and behavioural support for Jade and, when necessary, mediating to improve relationships.

One of the most important features of Jade's care was the focus on reasonable adjustments made to ensure her individual care needs were addressed. The Equalities and Human Rights Commission (2023) identifies three categories of duties in relation to reasonable adjustments, all of which are applicable in hospital settings: duty to change a provision, criterion or practice; duty related to physical features; duty to provide auxiliary aids. In an evaluation of the AHLDLN role, MacArthur et al (2015) identified a fourth category relevant to people with learning disabilities, which is ‘behavioural and emotional adjustments’. The reasonable adjustments made for Jade were wide ranging and covered all these categories. The specific examples of nursing priorities and positive risk taking/reasonable adjustments identified in Boxes 1 - 3 are important to share, particularly given a recent scoping review on reasonable adjustments for people with learning disabilities in acute care ( Moloney et al, 2021 ), which identified only six studies, with very few identifying actual applications in practice. Moloney et al's (2023) subsequent research on the experience of reasonable adjustments of parents of children with learning disabilities in acute care settings in Ireland revealed very limited positive examples of these being made.

Some key online learning resources for further information on meeting the needs of people with learning disabilities in healthcare settings are given in Box 4 .

Box 4.Online learning resourcesScotlandOnce for NES: Learning Disabilities (TURAS portal, NHS Education for Scotland)https://learn.nes.nhs.scot/59009EnglandThe Oliver McGowan Mandatory Training on Learning Disability and Autism (elearning for healthcare portal, NHS England)https://www.e-lfh.org.uk/programmes/the-oliver-mcgowan-mandatory-training-on-learning-disability-and-autism/WalesPaul Ridd Foundationhttps://paulriddfoundation.org/

The COVID-19 pandemic created an unprecedented impact on the UK population and for the NHS in all four countries. People with learning disabilities experienced higher levels of mortality from COVID-19 infections, which has in part been linked to pre-existing health inequalities and limitations in the knowledge, experience and attitudes of health professionals. Jade's case study is a positive example of collaboration between health professionals, working in partnership with her family to make reasonable and achievable adjustments that allowed her to recover from an initial life-threatening event.

- People with learning disabilities are known to experience a range of health inequalities, leading to significantly reduced life expectancy

- Mortality rates from COVID-19 infection for people with learning disabilities were 3-6 times higher than for the general population

- Acute hospital learning disability liaison nurses have become an established feature across the UK and are recognised for their role in ensuring person-centred care and practice development

- People with learning disabilities have a right to reasonable adjustments in their hospital care and these should include adaptations to the environment, augmented communication, risk-based modification to policies and procedures, and behavioural and emotional support

CPD reflective questions

- Think about your experiences of caring for people with learning disabilities in general hospital or primary care settings. Do you feel you had the knowledge and confidence to make reasonable adjustments to support their care?

- What resources do you have locally to support people with learning disabilities in hospital, including in critical care?

- If you were caring for someone with a learning disability who was non-verbal how would you assess and plan their care?

- How might your own healthcare environment impact people with learning disabilities and how do you think it could be adapted?

A Collective Case Study of Nursing Students with Learning Disabilities.

Nursing education perspectives 2003, sept-oct, 24, 5, publisher description.

ABSTRACT This collective case study described the meaning of being a nursing student with a learning disability and examined how baccalaureate nursing students with learning disabilities experienced various aspects of the nursing program. It also examined how their disabilities and previous educational and personal experiences influenced the meaning that they gave to their educational experiences. Seven nursing students were interviewed, completed a demographic data form, and submitted various artifacts (test scores, evaluation reports, and curriculum-based material) for document analysis. The researcher used Stake's model for collective case study research and analysis (I). Data analysis revealed five themes: I) straggle, 2) learning how to learn with LD, 3) issues concerning time, 4) social support, and 5) personal stories. Theme clusters and individual variations were identified for each theme. Document analysis revealed that participants had average to above average intellectual functioning with an ability-achievement discrepancy among standardized test scores. Participants noted that direct instruction, structure, consistency, clear directions, organization, and a positive instructor attitude assisted learning. Anxiety, social isolation from peers, and limited time to process and complete work were problems faced by the participants. STUDENTS WITH LEARNING DISABILITIES (LD) CONSTITUTE APPROXIMATELY 50 PERCENT OF STUDENTS WITH DISABILITIES IN COLLEGES AND NURSING PROGRAMS (2,3).

More Books Like This

More books by nursing education perspectives.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Med Educ

Medical students’ perceptions and understanding of their specific learning difficulties

Angela rowlands.

1 Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, UK

Stephen Abbott

2 School of Health Sciences, City University, London, UK

Grazia Bevere

3 Dyslexia and Disability Department, Queen Mary University of London, UK

Christopher M. Roberts

The purpose of this study is to explore how medical students with Specific Learning Difficulties perceive and understand their Specific Learning Difficulty and how it has impacted on their experience of medical training.

A purposive sample of fifteen students from one medical school was interviewed. Framework Analysis was used to identify and organise themes emerging from the data. An interpretation of the data was made capturing the essence of what had been learned. The concept of ‘reframing’ was then used to re-analyse and organise the data.

Students reported having found ways to cope with their Specific Leaning Difficulty in the past, some of which proved inadequate to deal with the pressures of medical school. Diagnosis was a mixed experience: many felt relieved to understand their difficulties better, but some feared discrimination. Practical support was available in university but not in placement. Students focused on the impact of their Specific Learning Difficulty on their ability to pass undergraduate exams. Most did not contemplate difficulties post-qualification.

Conclusions

The rigours of the undergraduate medical course may reveal undisclosed Specific Learning Difficulties. Students need help to cope with such challenges, psychologically and practically in both classroom and clinical practice. University services for students with Specific Learning Difficulties should become familiar with the challenges of clinical placements, and ensure that academic staff has access to information about the needs of these students and how these can be met.

Introduction

A Specific Learning Difficulty (SpLDs) is an umbrella category that includes dyslexia (reading difficulties), dyspraxia (motor difficulties), dysgraphia (writing difficulties) and dyscalculia (mathematical difficulties). Any of these SpLDs can make study at all levels difficult, although they are not linked with low intelligence. 1 , 2 Substantial numbers of students who have disclosed a SpLD enroll for higher education 3 and other students are diagnosed after admission. 4 Medical schools should expect a significant number of students with SpLDs, as evidence suggests that such individuals are more likely to choose a career in a ‘caring profession’ 5 , 6 indeed, there has been an increase nationally in the number of students diagnosed while at medical school. 7 Data for the medical school where this study was carried out show that proportionally more medical undergraduate students make themselves known to the university’s Disability and Dyslexia Service than students in other departments.The social model of disability emphasises how individuals with an SpLD are disabled by society’s failure to accommodate their particular needs, thereby further disadvantaging them. 8 In the UK, national disability legislation ensures that universities address this issue by offering help to students with SpLDs: extra time in examinations, equipment loans and grants for purchasing aids, etc. 9 Particular issues arise for health care professionals in training because their courses also require extensive experience in clinical practice. Support is likely to vary considerably between these two settings, given their different functions.However, students with SpLDs may do better in the clinical environment: Sanderson-Mann and McCandless 10 suggest that they tend to have a kinesthetic learning style which makes it easier to learn practical procedures, and, further, that they perform well clinically because of attributes such as creativity, greater oral recall, intuition, multi-dimensional thinking and innovation. Wray et al 11 and Fink 12 found high levels of empathy and interpersonal skills among nurses with SpLDs, while Wright’s 13 study suggested that having a disability can bring with it an insight into what it is like to be ill or disabled, which accordingly promotes the development of caring skills.While the tangible benefits offered in universities give incentives students to disclose their SpLDs, the benefits of disclosure in the clinical areas are less obvious. There is in any case a more general under-reporting of disabilities within the medical profession. 14 Also; there are difficulties translating strategies learnt in the classroom to the clinical setting. For example, students in one study found that using laptops, which had proved valuable in academic studies, met resistance from clinical staff and caused concern about the safety of the equipment. 15 At an individual level, students have to recognise and accept their SpLD before they can decide whether or not to disclose it and to ask for support. Gerber et al 16 suggest that in order to achieve, individuals with difficulties need to reframe their SpLD. Re-framing is a process whereby a person changes how they perceive or understand something, leading to changes in their responses and behaviour. Gerber et al 16 draw on earlier research about people with SpLDs at work to identify four distinct though overlapping stages in the re-framing process: recognition of the SpLD as such, understanding of the nature and implications of the SpLD; acceptance of both negative and positive aspects of the SpLD; and action in pursuit of both short- and long-term goals.A computer based literature search was performed to provide background to the study. A search combined the terms Dyslexia or Dyslex*or Dyspraxia or Dysprax*or Learning difficulties or learning difficult* or learning disabilities or learning disabilit* Nursing students, health professionals (as I wanted to read what work had been done in other health care fields too as certain clinical skill requirements are the same and prevalence is also high in nursing) or medical students.The Library databases used included: PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, British Education Index and the British Nursing Index were used (as well as a citation search), as these were considered the most applicable to the area of study. The literature search was limited to evidence in English from the last 10 years. These restrictions were applied since the most relevant legislation has been passed within this time frame. Medical practice is constantly changing and therefore it was important that this study reflected the current climate. In addition, some earlier articles have been included to gain insight into the background and history of the issues.The aim of the present study was to explore how medical students with a SpLD perceived and understood their SpLD and its effect on their education and future careers.

Study design

A qualitative methodology (semi-structured interviews) was used for data-gathering, as the emphasis was on self-perceptions rather than objective measurement.

Participants

Invitations to take part in a semi-structured interview were sent by an e-mail from the Dyslexia and Disability Department to all students attending the medical school who had registered with the university’s SpLD service (N=106). By the three month deadline required by the research timetable, fifteen medical students had volunteered, signed a written consent form, and had been interviewed. The rationale for using this purposive sample 17 was that it allowed access to and enabled medical students with SpLDs with something to say about their experience to come forward. Guest, Bunce and Johnson 18 argue that the size of a purposive sample relies typically on the concept of ‘saturation’ of data (the point at which no new information or themes are observed from the data). They found that data saturation occurred within the first 12 interview in qualitative data. Therefore the sample size was deemed large enough to answer the research question.

Interviews were audio-recorded where students agreed (this was included as a separate item on the written consent form.) The students were not personally known to the interviewer prior to the interview. The Queen Mary University of London Research Ethics Committee approved the study. The topic guide included the following topics: becoming aware of SpLD (when, where, feelings, consequences); impact of SpLD on school studies, career choice, university studies (non-medical), studies at medical school, experience on placement; anticipated impact on future career.

Data analysis

Initially, Framework Analysis was used to identify and organise themes emerging from the data. Ritchie and Spencer 19 described the 5 key steps of Framework Analysis: familiarisation with the text, identifying a thematic framework, indexing, charting and mapping and interpretation.During the first two stages of the data analysis the interviews were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim. All the data was read so that an overall sense of the information was gained. Each interview was given a number. A thematic framework was then developed. This involved developing an index of the key concepts, issues and themes and organising them into main categories and sub categories. In order to improve rigour inter-rater reliability was used to check the process of analysing the data. Two of us repeatedly listened to the audio records, compared the interviews, identified common themes and transcribed selected sections. We agreed on the meaning of the concepts and themes and compared the similarities and differences in our data analysis. We then developed a single index that we agreed upon and identified new main categories and sub categories.The third stage of the data analysis was indexing (or coding) the data. This was the process of deciding how to conceptually divide up the raw data. Narrative data from the transcriptions was numbered using line numbers so that units of text could be traced back to their original context when needed. Comments from the transcripts were divided up and arranged electronically into groups according to their initial coding before bringing meaning to the information. Certain ideas started to emerge from the transcripts and these were given a preliminary code. Some of these were changed and refined later but they served to begin the process of categorising and analysing the data. Codes were given abbreviations and written next to the appropriate segments of the text as well as recorded in a coding table.In the charting stage the data was synthesised and regrouped. Themes and concepts from all of the transcripts were drawn together. The categories were reduced by grouping topics that related to each other with the aim of generating a small number of themes that would form the main discussion points of the study. The themes were labeled by an expression taken directly from the data. Headings from the thematic framework were used to develop data charts which could be easily read across the whole data set. In the chart boxes, line and page references were put next to the relevant passages in the transcript.In the mapping and interpretation stage an interpretation of the whole data set was made after all the interview transcripts had been coded and charted. The charts and research notes were reviewed at this stage, comparisons and discrepancies between different perceptions and accounts of interviewees were noted and a search was made for patterns and associations within the data. An interpretation of the data was made capturing the essence of what had been learned from the data.It emerged from this process that Gerber et al’s 16 concept of ‘reframing’ would provide a useful analytic framework, and the data was accordingly re-analysed using Gerber’s stages as themes.

Fifteen medical students agreed to take part. One refused to be audio-taped but allowed note-taking. Ten were female and five male. Their years of medical training ranged from one to five. Two had previous degrees (one also had a PhD). Ten students described themselves as dyslexic, three as dyspraxic, and one as both; one had been diagnosed as dyslexic and dysgraphic. Interviews took place individually in a private room within the medical school and lasted typically a quarter of an hour (ranging between six and twenty-five minutes).Gerber et al’s 16 framework was helpful in understanding the data, but it became clear that students with SpLDs were likely to go through the reframing stages more than once at different points in their career, as their learning environment changed. For this reason, we organised the data into three re-framing cycles: before medical school, at medical school, and after medical school.

Before medical school

Three groups of students could be identified: Group A - those diagnosed with an SpLD before medical school. Group B - those aware before medical school of difficulties associated with learning, but who had not been diagnosed and Group C - those who had not seen themselves before medical school as having learning difficulties.The first group included two (nos. A2 and A4) who had been diagnosed at school, and two (nos. A6 and A7) who were diagnosed during their first degree (though both had been aware of difficulties in learning while at school). The second group (nos. B1, B8, B12, B13, B14, B15) had become aware that they were challenged by some aspects of academic study (e.g. reading, understanding, spelling) more than were their peers, but they had not been diagnosed until medical school. This awareness could be very long-lasting: one said that she had been aware of difficulties when learning her alphabet at primary school, but had not been assessed and diagnosed because of her family’s attitude:

“The sort of background I come from, you don’t really address issues. If you have a learning disability, obviously you just need to work harder; we’ll get you a personal tutor.” (Interview B12)

The third group (C3, C5, C9, C10, C11) had not realised that they faced learning difficulties that others did not: they recognised there were weak areas in their academic performance but saw these as normal.Data from group A students suggests that they had experienced the other re-framing stages before medical school; they understood and accepted their SpLDs, and had received help to facilitate study, which enabled them to progress to medical training (the action stage).One student in group A spoke ambivalently about acceptance. Although he did not challenge his diagnosis, and had taken advantage of help, he also believed that he should be trying to overcome his SpLD: he had attempted this before diagnosis, and reproached himself a little for having reduced his efforts since.

“I’m not sure it was a good thing to get diagnosed. I’ve always struggled with spelling and reading and writing, but I’ve always tried to overcome it. But when I got diagnosed, I thought, OK, that explains it, and I sort of stopped trying.” (Interview A7)

He thus suggested a dissonance between his behaviour (more accepting) and his belief (less accepting). He did know that expert opinion was that he could not overcome it, but he was reluctant to accept this:

“They say, we’ll teach you coping strategies. But you know, I’ve been coping, I don’t need coping strategies … I want to overcome it, and they say I can’t.” (Interview A7)

Given that groups B and C had not recognised their SpLD, one would not expect them to describe the other stages. However, some did speak of what they now realised was their earlier lack of understanding:

“Throughout school, the problems I was facing, I just thought they were the normal problems everyone would face ... I didn’t realise that that amount of time that [I needed] was not normal…English was just a weak subject… I didn’t really take any notice.” (Interview C11)

One student in group C itemised two factors that had obscured the problem. Firstly, he had adopted coping strategies without realising that that is what they were:

“I’ve always picked subjects that played to my strengths.” (Interview C10)

He understood this as a normal set of preferences for some subjects over others. Secondly, he, his brother and his parents had recently found out that they were all dyslexic, and with hindsight, he realised that this had made his difficulties seem normal.

“You kind of hear all these things and you think that that’s just normal, cos you don’t know any different… so it never occurred to me before…” (Interview C10)

Diagnosis at medical school had been enlightening, enabling students to re-frame their past experiences.

“When I got my diagnosis, a lot of things in my past [education and work] came clear… it answered a lot of questions…” (Interview B8)

Having a proper assessment could be vital to recognition. One student spoke of how teachers had repeatedly suggested that she was dyslexic, but she had always rejected this idea, as she was consistently good at English and reading: her diagnosis was in fact dyspraxia, and

“suddenly it all made sense.” (Interview C9)

At medical school

By definition, all those interviewed now recognised their SpLD, as they had made themselves known to the SpLD service. For students in groups B and C, it was recognition of the difficulties in studying at medical school that had led to self-referral to the service. Some were disappointed by the grades they were getting; others compared themselves with their peers.

“I was just taking much longer than the other students to write up a lecture, process information … exercises where I would be sharing a handout or a pamphlet or something, I would be like still there minutes after everyone else had finished.” (Interview B8)

Some students explained how the increased pressure of medical school had for the first time forced recognition on them.

“I got by [before] by being able to remember stuff and working at my own pace, probably. It was only when I was under so much pressure studying medicine - I was working absolutely flat out, and I think that’s when my strategies that had got me through like just wouldn’t cope any more, and I needed a new way to look at things.’ (Interview B1)

Recognition led to understanding of the SpLD and what it took to continue to study.

“I now know that simply writing out things from text books isn’t going to do it for me. And so the module after I had my test result back from the dyslexia person, I did everything in pictures … and then I got top of the class, from being an average person.” (Interview B8)

Others spoke of how understanding had an emotional effect.

“I felt really down about it… it dampened my confidence a little bit, so I think my motivation dwindled.” (Interview 12)

More mixed feelings were also reported:

“I was actually kind of relieved that it wasn’t something that I was actually doing wrong… [but] I get depressed a lot… I put a lot of effort into work and uni, and the fact that I’m not getting the same return as other people, it’s really frustrating.” (Interview B13)

Student B1 had gone for an initial screening by the SpLD service, but had then delayed going for full assessment:

“I had a lot of emotional feelings about having some kind of problems, so I put that off for quite a while.” (Interview B1)

But when she did receive a diagnosis, it brought her more positive feelings: she felt enabled to accept her limitations and to find constructive strategies to meet the demands of medical education.

“I started to feel better about myself… I don’t feel bad about having to print everything out now ... Whereas I used to think I was a bit picky about it, now I feel it’s OK to say … I need to touch it, I need to run my finger under it … I don’t feel bad about not being able to sit in the library for hours, which is what everyone else seems to do. I just study in short bursts, and if I’m tired, I won’t study, because I know that it won’t go in.” (Interview B1)

Generally speaking, those interviewed had not encountered prejudice or stigma because of their SpLD: minor instances, or fear of possible stigma, were briefly mentioned (in contrast with the third cycle, see below).Two students described an acceptance that was only partial. Student A2 described how, despite having been diagnosed at school, she found the challenges of her SpLD so normal that she wondered if she really had it.

“I even wonder myself sometimes, do I have dyslexia, am I different from anyone else, should I be getting extra time? I know I wouldn’t be here if I didn’t have extra time, but I don’t know… I can’t be like, ‘The dyslexia is annoying me’, because I don’t know anything else. So if I muddle my words, that’s just [her name] being silly.” (Interview A2)

This illustrates how familiarity with the SpLD can lead students to resist full acceptance of the diagnosis, and even, as in this case, to accept negative labeling (‘being silly’). This is particularly striking as this student already had both a bachelor’s degree and a doctorate.Student C10 felt unsure of the diagnosis because he had friends whose dyslexia was worse than his.

“You compare yourself to them, and it’s quite obvious that they struggle to read things and struggle to understand… it seems more obvious. So I sometimes even doubt if I am [dyslexic]…” (Interview C10)

For him, acceptance followed from understanding, which he felt in his case was as yet incomplete:

“I don’t even know if I fully comprehend what dyslexia is… still a learning process, I suppose.” (Interview C10)

Unsurprisingly, given that all students were supported by the SpLD service, there were many reports of actions taken to cope (extra time in exams, software, Dictaphones, etc.); and all had demonstrated, by continuing their studies at medical school, a commitment to pursuing their goal to become a doctor.

After medical school

Obviously, recognition had already taken place, but the third cycle had otherwise not begun: understanding and acceptance of the impact of SpLDs on work could only be guessed at. Some students did foresee likely difficulties when working as a doctor. These included: making mistakes with drug names or drug calculations; finding acronyms difficult; writing in patient notes under pressure; encountering problems when sitting Royal College examinations.Four students did not refer to any anticipated problems in how they would do their job technically, but identified stigma as a likely problem: negative perceptions by colleagues, and a possible barrier to work progression or choice of specialty. A third group of students foresaw no problems. Some explained that this was because of aids such as Dictaphones, while others expected their own skills to have improved to a satisfactory level (e.g. learning drug names). For another, the SpLD was associated with acquiring rather than using knowledge.

“By the end of your five years, you’ve learnt all the physiology you need. So I think on the wards that will require very much sort of applying your knowledge. I’ll hopefully already know it.” (Interview C3)

For another, the key skills required were about interpersonal rather than written communication

“You can be a pretty good doctor as long as you just listen to the patient.” (Interview B2)

Another student more specifically envisaged a career in medical teaching:

“I’d probably want to get into academic, because with my dyslexia, I’d understand how students feel… students would benefit from my learning experience.” (Interview B13)

Expectations of the likelihood or unlikelihood of future SpLD-related difficulties were not apparently linked to membership of group A, B or C.