291 Feminism Topics

Much has been written about feminism, yet there always are good feminism essay topics and issues to debate about. Here, we invite you to delve into this movement advocating for gender equality, women’s rights, and the dismantling of patriarchal norms. With our feminist topics, you can encompass a wide range of perspectives and theories that challenge systemic discrimination and promote social change.

334 Feminism Essay Topics & Examples

If you’re looking for original feminist topics to write about, you’re in luck! Our experts have collected this list of ideas for you to explore.

📝 Key Points to Use to Write an Outstanding Feminism Essay

🌟 top feminism title ideas, 🏆 best feminism essay topics & examples, 🥇 most interesting feminist topics to write about, 📌 creative feminist essay titles, ✅ simple & easy feminism essay titles, 🔍 interesting topics to write about feminism, 📑 good research topics about feminism, ❓ feminism questions for essay.

You may find yourself confused by various theories, movements, and even opinions when writing a feminism essay, regardless of your topic. Thus, producing an excellent paper becomes a matter of more than merely knowing your facts.

You should be able to explain difficult concepts while coincidentally touching upon fundamental points of feminist theory. Here are some starter examples of crucial essay-writing points, which can make your work better:

- Research and create a bibliography before beginning to write. There are various book and journal titles available both online and in libraries, and using them defines your essay’s credibility. You may use both books published long ago, such as “The Second Sex” by Simone de Beauvoir, and modern-day publications. Referencing reliable sources throughout your work will help you convince your readers that your approach is factual and in line with the main trends of the academic community.

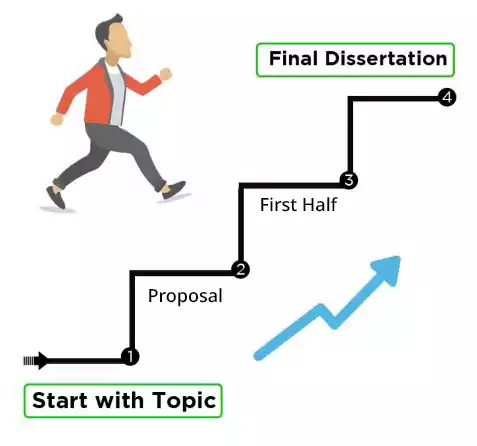

- Writing a feminism essay outline beforehand will save you precious time. Not only because it is a tool to get your thoughts in order before beginning to write but also because it allows you to judge whether you have covered the subject thoroughly. Furthermore, structuring beforehand enables you to understand possible drawbacks of your previous research, which you can promptly correct.

- Explain the history behind your problem. Doing so allows you to set the scene for your essay and quickly introduce it to an audience, who may not be as well versed in feminism essay topics as you. Furthermore, you can use your historical introduction later as a prerequisite to explaining its possible future effects.

- Be aware of the correct terminology and use it appropriately. This action demonstrates a profound knowledge of your assigned issue to your readers. From women’s empowerment and discrimination to androcentrism and gynocriticism, track the terms you may need to implement throughout your work.

- Do not overlook your title as a tool to gain your readers’ attention. Your papers should interest people from the beginning and making them want to read more of your work. Writing good feminism essay titles is a great start to both catching their attention and explaining what your central theme is.

- Read available feminism essay examples to understand the dos and don’ts that will help you write your own paper. Plagiarism and inspiration are different concepts, and you can get great ideas from others’ work, so long as you do not copy them!

After you have done your research, drafted an outline, and read some sample works, you are ready to begin writing. When doing so, you should not avoid opposing opinions on topics regarding feminism, and use them to your advantage by refuting them.

Utilizing feminist criticism will allow you to sway even those with different perspectives to see some aspects worthy of contemplation within your essay. Furthermore, it is a mark of good academism, to be able to defend your points with well-rounded counterarguments!

Remember to remain respectful throughout your essay and only include trusted, credible information in your work. This action ensures that your work is purely academic, rather than dabbling in a tabloid-like approach.

While doing the latter may entertain your readers for longer, the former will help you build a better demonstration of your subject, furthering good academic practices and contributing to the existing body of literature.

Find more points and essays at IvyPanda!

- 21st Century Patriarchy.

- Third Wave Feminism.

- Men in the Movement.

- Gender Roles in Sports.

- Femininity in Media.

- The History of Feminist Slogans.

- Must-Read Feminist Books.

- Feminist Perspective in Politics.

- Gender Equality in Patriarchal Society.

- Feminism & Contemporary Art.

- Feminism in “A Doll’s House” by Henrik Ibsen Nora is referred by her husband as a songbird, a lark, a squirrel, names that suggest how insignificant she is to her.

- Feminism: Benefits over Disadvantages They believe that feminists make the importance of family less critical than it used to be, which affects children’s lives and their psychological state.

- Feminist Approach to Health In general feminist recognize gender as an important aspect and believe that gender inequality essentially exist.

- Feminist Perspective: “My Last Duchess”, “To His Coy Mistress”, and “The Secretary Chant” He thinks such behavior is offensive to his position and his power, this is why this woman is in the past, and the other one is waiting for him downstairs to enlarge Duke’s collection of […]

- The Great Gatsby: Analysis and Feminist Critique The feminist critique is an aspect that seeks to explore the topic of men domination in the social, economic, and political sectors.

- Feminism in “The Handmaid’s Tale” by Margaret Atwood Religion in Gilead is the similar to that of the current American society especially, the aspect of ambiguity which has been predominant with regard to the rightful application of religious beliefs and principles.

- Hedda Gabler: Feminist Ideas and Themes Central to the female world was the woman with knowledge.”Think of the sort of life she was accustomed to in her father’s time.

- Third-World Feminism Analysis Although the primary aim of western feminists is centered on the issues women face, the beliefs of the third world consist of various tenets compared to western feminist interpretations.

- Top Themes About Feminism It’s a movement that is mainly concerned with fighting for women’s rights in terms of gender equality and equity in the distribution of resources and opportunities in society.

- Female Characters in Shakespeare’s “Othello”: A Feminist Critique This shows that Desdemona has completely accepted and respected her role as a woman in the society; she is an obedient wife to Othello.

- Feminist Criticism in Literature: Character of Women in Books Wright The unimportance of women in the play is a critical factor for the women should follow all the things that their men counterparts impose on them.

- Feminism in “The Introduction” and “A Nocturnal Reverie” by Finch One of Anne Finch’s poems, “The Introduction,” talks about female writers of her time in the first twenty lines of her text.

- Feminism in Frankenstein by Mary Shelley Mary Wollstonecraft expressly makes her stand known in advocating for the rights of the women in her novel, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, but her daughter is a bit reluctant to curve a […]

- Feminist Theory of Delinquency by Chesney-Lind One of the core ideas expressed by Chesney-Lind is that girls are highly susceptible to abuse and violent treatment. At the same time, scholars note that girls do not view delinquency as the “rejection of […]

- “We Should All Be Feminists” Adichie’s TED Talk For Adichie, the only thing necessary to qualify as a feminist is recognizing the problem with gender and aspiring to fix it, regardless of whether a person in question is a man or woman. This […]

- Metropolis’ Women: Analysis of the Movie’s Feminism & Examples This film is an endeavor to examine the image of the female depicted, the oppression that they have to endure before they are liberated, as well as the expectations of men with regard to the […]

- Feminism in Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler Hedda Gabler, upon the discovery that her imaginary world of free-living and noble dying lies in shivers about her, no longer has the vitality to continue existence in the real world and chooses self-annihilation. At […]

- Feminism in The Yellow Wallpaper In an attempt to free her, she rips apart the wallpaper and locks herself in the bedroom. The husband locks her wife in a room because of his beliefs that she needed a rest break.

- Feminist Connotations in Susan Glaspell’s “Trifles” It is a call to reexamine the value of women in a patriarchal society; through their central role in the drama, the female characters challenge traditional notions about women’s perspective and value.

- Race, Class and Gender: Feminism – A Transformational Politic The social construction of difference in America has its historical roots in the days of slavery, the civil war, the civil rights movement, and the various shades of affirmative action that have still not managed […]

- Character Analysis in Pride and Prejudice From the Feminist Perspective Darcy is a character who is able to evolve over the span of the story, and eventually, he recognizes his mistakes.Mr.

- Feminist Therapy: Gwen’s Case Study The application of a feminist perspective in Gwen’s case is different from other theoretical frameworks as the approach highlights the impact of gender and associated stressors on the client’s life.

- Feminism in Advertisements of the 1950s and Today In the paper, the author discussed how the whole process of advertising and feminism is depicted in print advertisements. The common characteristic is the advertisements’ illustration of feminism in the media.

- Gender Issues: Education and Feminism These experiences in many times strongly affects the individual’s understanding, reasoning, action about the particular issue in contention In this work two issues of great influence and relevance to our societies are discussed.

- Yves Klein’s Works From a Feminist Perspective The images were painted in the 20th century in the backdrop of the rising pressure in many parts of the globe for the government to embrace gender equality.

- The Fraternal Social Contract on Feminism and Community Formation The contract was signed by men to bring to an end the conditions of the state of nature. Life was anarchic and short lived which forced men to sign a social contract that could bring […]

- Feminism in “Heart of Darkness” and “Apocalypse Now” However, one realizes that she is voiceless in the novel, which highlights the insignificance of role of women in Heart of Darkness.

- Feminist View of Red Riding Hood Adaptations The Brothers Grimm modified the ending of the story, in their version the girl and her grandmother were saved by a hunter who came to the house when he heard the wolf snoring.

- Feminism in the “The Bell Jar” by Sylvia Plath This piece of writing reveals the concept of gender in general and “the role of female protagonists in a largely patriarchal world” in particular. In Plath’s novel, the bell jar is a metaphor used to […]

- A Feminist Life Lesson in “Sula” by Toni Morrison This essay is going to review gender and love and sexuality as the key themes that intertwined with Nel and Sula’s friendship, while also explaining how these influenced each of the two main characters. On […]

- Hello Kitty as a Kitsch and Anti-Feminist Phenomenon In this scenario, Hello Kitty is linked to the notion of kitsch because it connects adult men and women that are attached to the cute image to constant consumerism.

- Shifting the Centre: Race, Class, and Feminist Theorizing About Motherhood The author is very categorical in that it is necessary to put the role of the woman of color in the same position as that of the white one since this ensures that cultural identity […]

- Feminist Critique of Jean Racine’s “Phedre” Racine view Phedre as in a trap by the anger of gods and her destiny due to the unlawful and jealous passion that resulted into the deaths of Hippolytus and Oenone.

- Feminism in the Past and Nowadays The definition of liberal feminism is the following: “a particular approach to achieving equality between men and women that emphasizes the power of an individual person to alter discriminatory practices against women”.

- Mary Rowlandson’s Feminism and View on Women’s Role The sort of power developed by Rowlandson was such that it set her apart from the traditional roles of the Puritan women in her time and within her culture.

- Feminist Approach: Virginia Woolf In “A room of ones own” Virginia Woolf speaks about the problems of women, gender roles, and the low social position of women writers in society.

- Maya Angelou and Audre Lorde: The Black Feminist Poets The themes of double discrimination are developed in the poems “Woman Work” and “Still I Rise” by Maya Angelou and poems “A Meeting of Minds” and “To the Poet Who Happens to Be Black and […]

- The Picture of Arabic Feminist Najir’s father’s taking of her sexually excludes her from chances at a marriage of her own, because she is deprived of her virginity, and exposes the young woman to the risk of a pregnancy which […]

- Feminism in ‘Trifles’ by Susan Glaspell The Feminist Movement, also called the Women’s Movement and the Women’s Liberation Movement, includes a series of efforts by women in the world to fight for the restoration of gender equality.

- Feminist Theory and Postmodern Approaches It seems to me that such technique can be quite helpful because it helps to get to the root of the problem.

- Kate Chopin’s Feminist Short Stories and Novels Two short stories were written by Chopin, A Story of One Hour and The Storm well as her brilliant novel Awakening should be regarded as one of the best examples of the feminist literature of […]

- Feminist Theory of Family Therapy The purpose of this paper is to review and evaluate the feminist theory based on its model, views on mental health, goals, and the role of the counselor in the process.

- Willa Cather and Feminism Ability to work and/or supervise oneself as a woman is also quietly depicted through the girl who is able to work in the absence of her father. Cather depicts most of the women in her […]

- Importance of Feminism in Interpersonal Communication in “Erin Brockovich” In this presentation, the theme of feminism in interpersonal communication will be discussed to prove that it is a good example of how a woman can fight for her rights.

- Feminist Analysis of Gender in American Television The analysis is guided by the hypothesis that the media plays a role in the propagation of antagonistic sexual and gender-based stereotypes.

- Black Feminism: A Revolutionary Practice The Black Feminist Movement was organized in an endeavor to meet the requirements of black women who were racially browbeaten in the Women’s Movement and sexually exploited during the Black Liberation Movement.

- Popular Culture From the Fifties to Heroin Chic: Feminism The women have become aware of their legal rights and disabilities as a consequence of the inclusion of educated women in movements to repair the legal disabilities.

- Feminism: “The Second Sex” by Simone de Beauvoir According to post-structural feminism structures in society still hold the woman back.de Beauvoir states that this is because structures still exist in the minds of people as to the place of women in society.

- “Feminism and Modern Friendship” by Marilyn Friedman Individualism denies that the identity and nature of human beings as individuals is a product of the roles of communities as well as social relationships.

- Feminism and Roles in “A Raisin in the Sun” Play These are such questions as: “What does Beneatha’s conduct reveal about her intentions?”, “How does the character treat female’s role in society?”, “How does Beneatha regard poor people?”, “How does the heroine explain her choice […]

- Third World Feminism and Its Challenges As a conclusion, Sa’ar states that “it is rooted in the code of familial commitment, which is primarily masculine and includes women only secondarily,” which makes it difficult for women to commit to the family, […]

- “First Wave” Feminist Movement The reading explicitly details the pathways used by women and men in the United States in the 18th and 19th centuries to advocate for the realization of equality of rights across a wide spectrum of […]

- Feminism and Respect for Culture A crucial gender aspect that continues to trouble the unity of the people across the world is gender bias, which seems to encourage the formation of the feminist campaigns.

- Feminism in the 20th Century: a Literature Perspective. Research Summaries For years, the sphere of political, social and economical life of people all over the world was dominated by men, while women’ were restricted to the household domain; more to the point, women were not […]

- Women’s Health and Feminism Theory For a woman to be in charge of her reproductive health, she has to know some of the stages and conditions in her life.

- Feminist Research Methods The study of methods and methodology shows that the unique differences are found in the motives of the research, the knowledge that the research seeks to expound, and the concerns of the researchers and the […]

- Feminism Builds up in Romanticism, Realism, Modernism Exploring the significance of the theme as well as the motifs of this piece, it becomes essential to understand that the era of modernism injected individualism in the literary works.

- The Adoption of Structuralism and Post-Structuralism Basics in Feminist Cultural Theory On the contrary, post structuralism is opposite to such an assumption and uses the concept of deconstruction in order to explain the relations and the position of women in the society.

- “Othello” Through the Lens of Feminist Theory It depicts female characters in a state of submission and obedience and shows the disbalance in the distribution of power between men and women.

- The Feminist Theory in Nursing Since nursing has traditionally been a women’s profession, it is important to understand the oppression of women to gain insight into some of the most pressing issues in nursing.

- Historical Development of Feminism and Patriarchy Women in the United States have always encountered challenges that interfere with their individual fulfillment in society.

- The Concept of Feminist Epistemology The analysis starts with an overview of the evolutions process of standpoint epistemology; then, the philosophical movement is defined and the major ideas and arguments embedded into the theory are discussed.

- Ecological Feminism and Environmental Ethics Because of the effects that the process of globalization has had on the environment, including the increase in the speed of global warming and the scope of its outcomes, environmental ethics has gained significance.

- Feminism is for Everybody: Passionate Politics It seems that this approach to this problem is important for discussing the origins of social inequalities existing in the community. This is one of the main points that can be made.

- Comparing Views on the Feminism of Wollstonecraft and Martin Luther King This means that if women are given and encouraged to have the same level of education as the men than the society would be a much better place as both the female and male genders […]

- Judith Butler’s Feminist Theory From a phenomenological point of view, gender is a stable identity that is realized through the repetition of certain acts. Butler’s article is dedicated to the role of gender, its relation to a body and […]

- Charlotte Gilman’s feminism theory Because of the many issues that women face, feminism movements’ seeks equality between men and women in the society. Throughout, the paper will discuss Gilman’s feminism theory and relate it to the issues of women […]

- Feminist Accountability Approach Therefore, the feminist accountability approach involves the collective responsibility to fight social injustices regardless of gender and race. Therefore, integrating the global approach to social injustice promotes the aspect of universality and unity in promoting […]

- The Feminist and Gender Theory Influence on Nursing That is, gender and feminist theories are still relevant in the modern world. This is explained by the fact that women are struggling to demonstrate their professionalism in order to receive the same recognition and […]

- The Incorporation of Feminism in Literature By focusing on the character, the book portrays the demand for feminism in society to allow females to have the ability and potential to undertake some responsibilities persevered by their male counterparts. The belief in […]

- The Feminist Theory, Prostitution, and Universal Access to Justice In the essay, it is concluded that the theory is a key component of the reforms needed in the criminal justice system with respect to prostitution. In this essay, the subject of prostitution is discussed […]

- Feminism in ‘Telephone Video’ To demonstrate how feminist theory in communication is relevant to music, the paper will analyze the depiction of females, the vocal arrangements, representation of female roles and their visual appearance in Lady Gaga’s “Telephone” music […]

- Feminist Theory in Psychotherapy This theory puts women at the first place, and this place is reflected in three aspects: the first is its main object of study – the situation and difficulties faced by women in society, and […]

- A Feminist Analysis on Abu Ghraib Moreover, these tortures were intended to become public with the help of demonstrations at Abu Ghraib and taking photographs that accentuated the loss of prisoners’ masculine power.[4] According to Foucault’s views, public torture is an […]

- Feminist Perspective in “Ruined” Play by Nottage This is a story about the issues of women in the Democratic Republic of Congo during the civil war. The comments of ‘Anonymous’ published as a response to the review of Jill Dolan, demonstrate the […]

- Feminist Political Theory, Approaches and Challenge However, regardless of studying the perception of women and their role in society, there is no unified approach in feminist political theory that leads to the existence of the so-called feminist challenge.

- Feminism in the Story “Lord of the Rings” The movie, in its turn, instead of focusing on the evolution of the female leads, seemed to be concerned with the relationships between the male characters as well as the growth of the latter.

- Feminist Pro-Porn During Sex Wars In particular, this group was determined to fight for the rights of the lesbians as they realised that the arguments of the anti-porn feminists were against their freedom.

- Seven Variations of Cinderella as the Portrayal of an Anti-Feminist Character: a Counterargument Against the Statement of Cinderella’s Passiveness It is rather peculiar that, instead of simply providing Cinderella with the dress, the crystal slippers and the carriage to get to the palace in, the fairy godmother turns the process of helping Cinderella into […]

- Feminist Literature: “The Revolt of Mother” by Mary E. Wilkins The woman in her story goes against the tradition of the time and triumphs by challenging it and gaining a new self-identity. The author uses this story to address the issue of women oppression that […]

- Feminist Films: “Stella Dallas” and “Dance Girl, Dance” In my opinion, the film’s main idea is the relations between the mother and the daughter. In other words, I would like to point out that it is a female subjectivity, which is recognized to […]

- Comparing Mainardi and Kollantai on Housework and Women’s Oppression Mainardi and Kollantai argue that women should be liberated from chores for the sake of the future. Nonetheless, the two feminists have different views on the way liberation can be achieved.

- Bell Hooks’ Article Analysis With Regard to Women and Minorities Feminism is meant to stop sexist oppression. The major aim of these movements has not yet been achieved. Bell Hooks promotes the knowledge of feminist theory as essential portion of the development of self-actualization.

- Equal Society: Antebellum Feminism, Temperance, and Abolition It is characterized by the emergence of a women’s rights movement that was spearheaded by activists who sought to secure the rights of women to vote, own property, and participate in education and the public […]

- Feminism in the “Lorraine Hansberry” Film Her activism aligns with the fundamental tenets of women of color feminism, which emphasizes the intersecting nature of oppression and the importance of centering the experiences of marginalized groups in social justice movements.

- Gloria Steinem: Political Activist and Feminist Leader Thesis: Gloria Steinem’s direct, bold, argumentative, and explicit style of conveying her ideas and values is the result of her political activism, feminist leadership, and her grandmother, Pauline Perlmutter Steinem.

- The Myntra Logo from a Feminist Perspective The first feature of the Myntra logo that comes under the scrutiny of transnational feminism is the commercialization of female sexuality.

- Feminist Geography and Women Suppression Tim Cresswell’s feminist geography explores how the patriarchal structures of our society have silenced women’s voices and experiences in the field of geography for centuries and how recent changes in the field have allowed for […]

- Feminism from a Historical Perspective Accordingly, the discontent facilitated the development of reform-minded activist organizations across Europe and the United States and the subsequent rise of the Modern or New Women’s Movement.

- The Feminist Theory in Modern Realities The theory and culture of feminism in modern philosophy and the development of society play a significant role in cultural and social development.

- Alice Walker’s Statement “Womanist Is to Feminist…” In her short tale “Perspectives Past and Present,” author and poet Alice Walker famously uses the statement “Womanist Is to Feminist as Purple Is to Lavender,” meaning that womanist is a larger ideological framework within […]

- Feminist Perspective on Family Counselling The author of the article considers the study and the data obtained as a result of it as information reporting not only about the specifics of homosexual relationships but also about their perception in American […]

- Modern Feminism and Its Major Directions Radical feminism views patriarchy as the reason men have more rights than women and attempts to fight against it. Liberal, intersectional, and radical feminism differ in many ways as they have various perspectives on women’s […]

- Feminist Theory and Its Application Alice Walker advocated for the rights of women of color at the end of the 20th century, creating a feminist branch named womanism. The feminist theory is one of the most known and popular theories […]

- Discussion of Feminist Movements The feminist movements have been behind a sequence of political and social movements that champion the equal rights of women in all aspects of life.

- Feminists on the Women’s Role in the Bible The author of the article uses the term intertextuality, which plays a significant role in the text analysis, including from the feminist aspect.

- Feminist Contribution to International Relations Moreover, it will be shown that the concept of gender is important as it helps to shed light on the power dynamics in the sphere of international relations and explain female exclusion from politics.

- Emotional Revival in Feminist Writers’ Short Stories This paper aims to discuss the emotional revival of heroines in the short stories of Kate Chopin and Charlotte Perkins Gilman.”The Story of an Hour” is a very short story that describes a woman’s experience […]

- Emotion and Freedom in 20th-Century Feminist Literature The author notes that the second layer of the story can be found in the antagonism between the “narrator, author, and the unreliable protagonist”.

- The Cyborg Term in the Context of Feminist Studies In other words, during the transition of identity from the individual to the collective level, people, especially women, may encounter inequalities manifested in the collective space.

- Feminist and Traditional Ethics The feminist ethics also criticize the gender binary of distinct biological formation between men and women. Consequentialism, deontology, and virtue ethics are the three theories of conventional ethics.

- Feminism: A Road Map to Overcoming COVID-19 and Climate Change By exposing how individuals relate to one another as humans, institutions, and organizations, feminism aids in the identification of these frequent dimensions of suffering.

- White Privilege in Conflict and Feminist Theories They see how the privilege of whiteness and denial of non-whiteness are connected to the social and political meaning of race and ethnicity.

- Women’s Role in Society From Feminist Perspective Also, in Hartsock’s opinion, that the whole society would benefit if women were allowed to have a role equal with men in a community.

- The Feminist Theory and IR Practice Focusing on how international relations theorists explained some concepts, such as security, state, and superiority that led to gender bias, feminists felt the need to develop and transform the international relations practice and theory.

- Intersectionality and Feminist Activism Therefore, I hope to study the academic literature to discuss the existing tendencies and difficulties to contribute to the understanding of the identified topic in terms of gender and female studies.

- Feminism: Reflection of Cultural Feminism If they found that the gases were harmful and may lead to complications in their body, they would approve the employer’s right to prohibit women from working in the company.

- Feminist Theoretical Perspectives on Rape There is a number of theoretical perspectives aimed at explaining what stands behind rape, that is, how rape is reinforced by, why it is more widespread in specific concepts, and what a rapist’s motivations for […]

- A Feminist Reading of “Wild Nights” and “Death Be Not Proud” From the feminist perspective, the key feature of the speaker’s stance in “Death Be Not Proud” that sets it apart from “Wild Nights” is the speaker’s persona, which is openly and unequivocally male.

- Body: Social Constructionist & Feminist Approaches The idea of the gendered body was based on the focus on the concept of gender, which sees masculinity and femininity as social roles and the need for the representatives of genders to maintain within […]

- Feminist Film Theory Overview The presence of women on the screen is commonly accomplished by the sexualization and objectivization of female characters. Along with that, sadism and fetishism toward the physical beauty of the object and the representation of […]

- “Daddy-long-Legs”: Why Jerusha Is a Feminist Heroine Jerusha is a feminist because she uses the letters to communicate the inequalities she feels in her relationship with Daddy-long-legs and her limits.

- Homosexuality and Feminism in the TV Series The depiction of these complex topics in the TV series of the humoristic genre implies both regressive and progressive impulses for the audience.

- Popular Feminism in Video Post of Emma Watson According to Emma Watson, now feminism is increasingly associated with hatred of men, although in reality it only implies the belief that men and women should have equal rights and opportunities.

- Contingent Foundations: Feminism and Postmodernism Feminism offers women theoretical bases on which to interrogate the issues of womanhood while Postmodernism takes this away by arguing for the “death of subjects”.abolition of the foundations of the ideals of reality.

- Art, Pornography and Feminism and Internet Influence The purpose of pornography is not the desire to admire the human body and respect physical intimacy. Indeed, society can say that women themselves agree to such rules, but the choice of a minority forms […]

- The Contemporary Image of Feminism Following the initial surge of the movement, governments finally came to acknowledge the magnitude of the situation and satisfied the demands of the female population.

- Feminism and Nationalism: The Western World In this case, we find that feminism has been a different that all the time and therefore, it is impossible to predict the trend of feminism in future.

- Gould’s and Sterling’s Feminist Articles Critique The focal point of this paper is to prepare a critical reflection on the articles by Stephen Jay Gould named “Women’s Brains” in The Panda’s Thumb and by Anne Fausto-Sterling named “The biological Connections,” from […]

- Core Aspects of Black Feminist and Womanist Thoughts Compared to Jones, who believes in “unparalleled advocates of universal suffrage in its true sense,” Lindsey does not support the relegation of the “voices and experiences of women of color to the background”.

- Barbara and Beverly Smith: Black Feminist Statement Sexism was an explicit element of the African American Civil Rights Movement. Fight against segregation was rather single-sided.

- Feminism: Fundamentals of Case Management Practice The feminist therapy’s main emphasis is put on the notion of invoking social changes and transforming the lives of people in favor of feminist resistance in order to promote equality and justice for all.

- Feminist Contributions to Understanding Women’s Lives This gave women a clear picture of the daily realities in their lives. The success of feminism is evident at all levels of human interaction since there is a better understanding of women and their […]

- As We Are Feminist Campaign’s Strategic Goals The present paper is devoted to the analysis of the goals of a feminist campaign As We Are that is aimed at challenging gender stereotypes that are being promoted by the media and society in […]

- Feminist Ethics in Nursing: Personal Thoughts The concept of feminist ethics emphasizes the belief that ethical theorizing at the present is done from a distinctly male point of view and, as such, lacks the moral experience of women.

- Feminism: Kneel to the Rest of Life, or Fight for the Fairness It seems that the law is not perfect, and the public opinion of sexual harassment might influence a woman’s life negatively.

- Feminist Perspective Influence on Canadian Laws and Lawmakers The change in the statistics is attributed to social changes, which include increase of women in the labor force, conflict in female-male relations, increase in alcohol consumption and increase in the rate of divorce. Feminists […]

- Blog Post: Arab Feminism in Contemporary World Women of the Arab world have struggled to overcome inequality, oppression, and rights deprivation by state authorities, which takes the discussion of the Islamic feminist movement to the political domain. According to Sharia, the unity […]

- Feminist Movement and Recommendations on Women’s Liberation According to Nawal El-Saadawi In Egypt, the feminist movement was started by Nawal El-Saadawi, and her article “The Arab Women’s Solidarity Association: The Coming Challenge” has historical importance as it addresses the plight of women in the community.

- Technological Progress, Globalization, Feminism Roots However, the work becomes more complicated when the time distance of the events and processes is shorter, and the stories are unfinished.

- Race at the Intersections: Sociology, 3rd Wave Feminism, and Critical Race Theory In this reading, the author examines the phenomenon of racism not merely as an issue but a systematic, institutionalized, and cultural phenomenon that is hard to eliminate.

- The Feminist Performers: Yoko Ono, Marina Abramovic, Gina Pane The feminist artists ccontributed to the women’s image, its role in society, and exposed the passiveness and submissiveness the women are obliged to endure.

- Feminism and Multiculturalism for Women The foundation of liberalism is having an interest in all the minority cultures that are put together to form the larger special group.

- “The Great Gatsby” by Fitzgerald: Betrayal, Romance, Social Politics and Feminism This work seeks to outline the role of women in the development of the plot of the book and in relation to the social issues affecting women in contemporary society.

- Pornography’s Harm as a Feminist Fallacy In this scenario, scientific research has proven the argument not to be true. It is weakened by the fact that people are not forced to watch the video.

- Feminism in Mourning Dove’s “Cogewea, the Half-Blood” The patriarchal practices embraced by the Indian community and the subsequent system of governance humiliated the writer; hence, the use of Cogewea in the passage was aimed to imply the abilities that were bestowed upon […]

- Feminist Film Strategy: The Watermelon Women These techniques have the capabilities of shifting meaning away from the narrative as the source of meaning to the audience’s background knowledge in making meaning.

- The Emerging Feminism in India and Their Views on God as a Feminist However, among the explanation of the cause of the phenomenon for this lack of agreement is the tendency for people to define religion too narrowly, and in most cases from the perspective of their own […]

- Feminist Psychology in Canada The introduction of the article gives the purposes of the research that include the historical and present condition of the psychology of women field of interest.

- American Art Since 1945 Till Feminism The entire movement represented the combination of emotional strength and the self-expression of the European abstract schools: Futurism, the Bauhaus and Synthetic Cubism.

- Modernist Art: A Feminist Perspective Clarke limited the definition of modernism even further by his restriction of it to the facets of the Paris of Manet and the Impressionists, a place of leisure, pleasure, and excesses, and it seems that […]

- Enlightenment, Feminism and Social Movements As a result of Enlightenment, the creative entrepreneurs as well as thinkers enjoyed the high freedom benefits that were brought in by the Enlightenment thinkers, enabling them to apply the newly acquired liberty to invent […]

- “Our Journey to Repowered Feminism” by Sonja K. Foss Foss tried to work out a new conception of repowered feminism in the article “Our Journey to Repowered Feminism: Expanding the Feminist Toolbox”.

- Feminist Position on Prostitution and Pornography The only requirement is that it should not violate the norms of the law. On the other hand, one of the suggestions for feminists is to envisage individual cases of enslaving women as prostitutes.

- The Politics of Feminism in Islam by Anouar Majid Considering the work The Politics of Feminism in Islam by Anouar Majid written in 1998, it should be noticed that the main point of this article is the Muslim feminism and the relation of West […]

- The Feminist Art Movement in the 1970s and Today The feminist art movement emerged in the 1960s and from that time the women had taken much interest in what causes them to be different from the male gender and particularly, what causes the art […]

- Feminist Theory. Modes of Feminist Theorizing The second point of conflict is the acknowledgment that most of the feminist ideas are part and parcel of our culture yet these ideas might be presented in a way that is hard for us […]

- Australian Feminism Movements The fact that feminism movements do not have a great following in Australia is because they are not generally seen to address issues that women and the society are facing.

- Feminism in Canadian Literature First of all, the female author of the article considered by Cosh is evidently a supporter of the equality of rights for men and women, and her account on the women liberation movement in the […]

- Understanding of Feminism: Philosophical and Social Concepts The vision that emerges, in the narrative as in the world it represents, is of a whole composed of separate, yet interdependent and interrelating, parts.

- Geoffrey Chaucer: A Founder of English Literature as a Feminist Despite the distorted interpretation of gender in the patriarchal society, Chaucer’s vision of women contradicts the orthodox view of the biological distinction of males and females as the justification for gender inequality.

- Feminist Activism for Safer Social Space by Whitzman The scientist pays special attention to the municipal parks, mainly High Park in Toronto, from the point of view of feminists trying to make women involved into the discourse concerning different aspects of the park.

- Western Feminism as Fighters Against Oppression For postmodern feminists and post-colonial feminists, the second component of the new women’s ideology is the idea of the responsibility of the state to rule and administer both genders on the basis of their interpretation […]

- Perils and Possibilities of Doing Transnational Feminist Activism These have promoted awareness of human rights among women and other masses, ensured and led to the adoption of the rules and regulations recognizing women rights and that supports ending of women violations and participated […]

- The Feminist Gendering Into International Relations These are early female contributions to IR academic and the In terms of conferences, the theme of gender and politics was being explored in conferences.

- “Feminism and Religion: The Introduction” by R. Gross Gross critically in order to see the essence of the book and the competence of the author in the current issue.

- Western Feminists and Their Impact on the Consciousness and Self-Identity of Muslim Women One of the main objectives of the Western feminism is to give to the citizen of the new nation a feeling of dignity and importance resulting from that citizenship and from his ethnic origin, and […]

- Feminism – Women and Work in the Middle East The history of feminism consists of different movements and theories for the rights of women. The first wave of this phenomenon began in the 19th century and saw the end only in the early 20th […]

- Harriet Martineau, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, and Marianne Weber: Feminist Sociologists Through her writings she always advocated for the equal rights of women with men and remarked the importance of financial self-sufficiency among women in the society. She observed the role of women in society and […]

- English Language in the Feminist Movement In addition to that, it is of the crucial importance to explore the underlying causes of this phenomenon. Now that we have enumerated the research methods, that can be employed, it is of the utmost […]

- Feminist Ideas in Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein”

- Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s Works and Feminism

- Positive Changes That Feminism Brought to America

- Are Feminist Criticisms of Militarism Essentialist?

- Western Feminist Critics and Cultural Imperialism

- Social Justice and Feminism in America

- American Women in History: Feminism and Suffrage

- Wendy McElroy: A Feminist Defense of Men’s Rights

- Modern Feminism as the Part of Intellectual Life

- Feminist Movements in Contemporary Times

- Feminist Critiques of Medicine

- Shakespeare: A Feminist Writer

- Liberal Feminism Movement Analysis

- Feminism and Support of Gender Equality

- Feminism: Liberal, Black, Radical, and Lesbian

- Women and Law. Feminist Majority Foundation

- Empowerment and Feminist Theory

- “The Historical Evolution of Black Feminist Theory and Praxis” by Taylor

- Is Power Feminism a Feminist Movement?

- Postcolonial Feminism Among Epistemological Views

- Feminist Theory: Performing and Altering Bodies

- Feminist Theories by Bordo, Shaw & Lee, Shildrick & Price

- Feminist Examination of Science

- Race, Sex and Knowledge From Feminist Perspective

- Colonialism and Knowledge in Feminist Discourse

- Feminism and the Relational Approach to Autonomy

- Feminism and Sexuality in the “Lila Says” Film

- Feminist Perspective: “The Gender Pay Gap Explained”

- Second Wave of Feminist Movement

- Feminist Approach in Literary Criticism

- Education and Feminism in the Arabian Peninsula

- Black Women in Feminism and the Media

- Spiritual and Educational Feminist Comparison

- Feminist Theoretical Schools in Various Cultures

- The Application of Psychoanalysis in Feminist Theories

- Feminism: Exposing Women to the Public Sphere

- Feminist Psychoanalysis From McRobbie’s Perspective

- Ageism and Feminism in Career and Family Expectations

- “Feminist Geopolitics and September 11” by Jenifer Hyndman

- The History of Feminism in the 1960

- Feminist Theory in “A Family Thing” Movie

- Feminism in Tunisia and Jordan in Comparison

- Feminism and Gender Studies in Science

- Feminism in the United Arab Emirates

- Conceptualization of Difference in Feminism

- Feminism in Latin America

- Planet B-Girl: Community Building and Feminism in Hip-Hop

- Methods of Feminism Education and Its Modern Theories

- Feminism in Lorrie Moore’s “You’re Ugly, Too”

- Anti-Feminism and Heteropatriarchal Normativity

- Feminist Archaeologists’ Interpretations of the Past

- The Theory of Feminism Through the Prism of Time

- Development of Feminism in Chile

- Elena Poniatowska and Her Feminism

- Feminism in Laura Esquivel’s “Like Water for Chocolate”

- Concept of “Western Feminism”

- Marxism vs. Feminism: Human Nature, Power, Conflict

- Feminism in Lorber’s, Thompson’s, Hooks’s Views

- Prison and Social Movement in Black Feminist View

- Great Awakening, American Civil War, and Feminism

- Feminist Miss America Pageant Protest of 1968

- Black Feminist Perspectives in Toni Morrison’s Works

- Feminist Movement as an Attempt to Obtain Equal Rights

- Axel Honneth Views on Feminism

- Activist and Feminist Rose Schneiderman

- Feminist Deceit in Short Stories

- Post-Feminism in the Wonder Bra Commercial

- Feminist Movement Influence on the Arab Film Industry

- Feminism: the Contraception Movement in Canada

- Beyonce and Assata Shakur Feminism Ideas Comparison

- Feminism in “‘Now We Can Begin” by Crystal Eastman

- Gender Studies of Feminism: Radical and Liberal Branches

- Feminism and Film Theory

- The Realization of Third-wave Feminism Ideals

- Sexuality as a Social and Historical Construct

- Modern Feminist Movements

- Feminist Theories in Relation to Family Functions

- Rebecca Solnit’s Views on Feminism

- “Old and New Feminists in Latin America: The Case of Peru and Chile” by Chaney E.M.

- “Frida Kahlo: A Contemporary Feminist Reading” by Liza Bakewell

- Chinese Feminism in the Early 20th Century

- Feminism and Modern Friendship

- Historical Development of Feminism and Patriarchy

- Women and Their Acceptance of Feminism

- Women, Religion, and Feminism

- The History of the Pill and Feminism

- Challenges to Build Feminist Movement Against Problems of Globalization and Neoliberalism

- Feministic Movement in Iron Jawed Angels

- Hillary Clinton: Furthering Political Agenda Through Feminism

- Feministic View of McCullers’ “The Member of the Wedding”

- “Feminism, Peace, Human Rights and Human Security” by Charlotte Bunch

- Feminism in China During the Late Twentieth Century

- Feminist Political Change

- Antonio Gramsci and Feminism: The Elusive Nature of Power

- Changes That Feminism and Gender Lenses Can Bring To Global Politics

- Feminism Has Nothing to Tell Us About the Reality of War, Conflict and Hard, Cold Facts

- Feminism in the works of Susan Glaspell and Sophocles

- Cross Cultural Analysis of Feminism in the Muslim Community

- The Adoption of Feminist Doctrine in Canada

- Feminist Movement in Canada

- The Feminist Power and Structure in Canada

- Feminism and Gender Mainstreaming

- Feminist Movement: The National Organization for Women

- Female Chauvinist Pigs: Raunch Culture and Feminism

- Feminist Analysis of the Popular Media: The Sexualization Process Takes Its Toll on the Younger Female Audience

- Women in the Field of Art

- The Reflection of the Second-Wave Feminism in Scandinavia: “Show Me Love” and “Together”

- Liberal and Socialist Feminist Theories

- What Does Feminism Stand For? Who are These Creatures who call themselves Feminists?

- Full Frontal Feminism – What is Still Preventing Women from Achieving Equality?

- The Ordeal of Being a Woman: When Feminist Ideas Dissipate

- Comparison and Contrast of Spiritual and Educational Feminists

- Gender Issue and the Feminist Movement

- Dorothy E. Smith and Feminist Theory Development

- Feminist Movement Tendencies

- Scholars Comment on Gender Equality

- The Smurfette Principle in the Modern Media: Feminism Is over?

- Feminist Challenge to Mainstream International Relations Theory

- The Feminist Movement

- Feminism and Evolution or Emergence of Psychology

- Reasons Why the Black Women Population Did Not Consider Themselves a Part of the Ongoing Feminist Movements

- Black Women and the Feminist Movement

- Feminism and Patriarchy

- Feminism Interview and the Major Aim of Feminism

- Gender and Religion: Women and Islam

- World Politics: Realist, Liberals, and Feminists Theories

- Concept and History of the Liberal Feminism

- Feminism and Women’s History

- Feminist Criticism in “The Story of an Hour” and “The Yellow Wallpaper”

- Obesity: Health or Feminist Issue?

- Feminism in Roger and Dodger Film

- Anarchy, Black Nationalism and Feminism

- Concepts of Feminism in the Present Societies

- Gender Issues and Feminist Movement

- How Did African Feminism Change the World?

- Why Might Feminism and Poststructuralism Be Described as an Uneasy Alliance?

- Does Feminism and Masculinity Define Who People Are Today?

- How Did Feminism Change New Zealand?

- Can Feminism and Marxism Come Together?

- How Did Second Wave Feminism Affect the Lives of Women?

- Does Arab Feminism Exist?

- How Does Chivalry Affect Feminism?

- Has Feminism Achieved Its Goals?

- How Does the French Feminism Theory Manifest Itself?

- Does Feminism Create Equality?

- How Has Feminism Changed the Lives of Women, Men, and Families?

- Has Feminism Benefited the American Society?

- How Does Feminism Explain Gender Differences in Comparison to the Mainstream Psychology?

- Does Feminism Discriminate Against Men?

- How Does Feminism Harm Women’s Health Care?

- Does Feminism Really Work?

- How Does Feminism Threaten Male Control and Alters Their Dominance in Society?

- What Are the Basic Traits of Liberal Feminism?

- How Has Economic Development and Globalization of South Korea Influenced the Role of Feminism?

- What Are the Concepts of Marxism and Feminism?

- How Has Feminism Developed?

- What Are the Main Theoretical and Political Differences Between First and Second Waves of Feminism?

- Why Should Men Teach Feminism?

- How Does Popular Fiction Reflect Debates About Gender and Sexuality?

- When Does Feminism Go Wrong?

- How Do Teenage Magazines Express the Post-feminism Culture?

- Why Has Patriarchy Proved Such a Contentious Issue for Feminism?

- What Are the Main Contributions of Feminism to the Contemporary Lifestyle?

- Can Modern Feminism Start the Discrimination of Men?

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, February 24). 334 Feminism Essay Topics & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/feminism-essay-examples/

"334 Feminism Essay Topics & Examples." IvyPanda , 24 Feb. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/feminism-essay-examples/.

IvyPanda . (2024) '334 Feminism Essay Topics & Examples'. 24 February.

IvyPanda . 2024. "334 Feminism Essay Topics & Examples." February 24, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/feminism-essay-examples/.

1. IvyPanda . "334 Feminism Essay Topics & Examples." February 24, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/feminism-essay-examples/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "334 Feminism Essay Topics & Examples." February 24, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/feminism-essay-examples/.

- Motherhood Ideas

- Gender Stereotypes Essay Titles

- Women’s Role Essay Topics

- Sociological Perspectives Titles

- Gender Discrimination Research Topics

- Masculinity Topics

- Activist Essay Titles

- Gender Issues Questions

277 Feminism Topics & Women’s Rights Essay Topics

- Icon Calendar 18 January 2024

- Icon Page 2272 words

- Icon Clock 11 min read

Feminism topics encompass a comprehensive range of themes centered on advocating for gender equality. These themes critically address the social, political, and economic injustices primarily faced by females, aiming to dismantle patriarchal norms. Feminism topics may span from intersectional feminism, which underscores the diverse experiences of women across various intersections of race, class, and sexuality, to reproductive rights that advocate for women’s bodily autonomy and healthcare accessibility. They also involve the examination of workplace discrimination through concepts, such as the gender wage gap and the glass ceiling. Violence against women, including work and domestic abuse, sexual assault, and harassment, is a hot aspect, providing many discussions. In turn, one may explore the representation of women in media, politics, and STEM fields. Explorations of gender roles, gender identity, and the significance of male feminism are integral parts of these discussions. As society continues to evolve, feminism topics persistently adapt to confront and address emerging forms of gender inequality.

Best Feminism & Women’s Rights Topics

- Achievements of Women in Politics: A Global Perspective

- Emphasizing Gender Equality in the 21st-Century Workplace

- Evolving Representation of Women in Media

- Fight for Women’s Voting Rights: The Historical Analysis

- Intersectionality: Examining its Role in Feminism

- Unpacking Feminism in Third-World Countries

- Dissecting Misogyny in Classical Literature

- Influence of Religion on Women’s Rights Worldwide

- Unveiling Bias in STEM Fields: Female Experiences

- Gender Pay Gap: Global Comparisons and Solutions

- Probing the Historical Evolution of Feminism

- Reshaping Beauty Standards Through Feminist Discourse

- Importance of Reproductive Rights in Women’s Health

- Exploring Women’s Role in Environmental Activism

- Glass Ceiling Phenomenon: Women in Corporate Leadership

- Trans Women’s Struggles in Feminist Movements

- Empowering Girls: The Role of Education

- Intersection of Race, Class, and Feminism

- Effects of Feminism on Modern Art

- Impacts of Social Media on Women’s Rights Movements

- Deconstructing Patriarchy in Traditional Societies

- Single Mothers’ Challenges: A Feminist Perspective

- Dynamics of Feminism in Post-Colonial Societies

- Queer Women’s Struggles for Recognition and Rights

- Women’s Contributions to Scientific Discovery: An Underrated History

- Cybersecurity: Ensuring Women’s Safety in the Digital Age

- Exploring the Misrepresentation of Feminism in Popular Culture

- Repositioning Sexuality: The Role of Feminism in Health Discourse

- Women’s Economic Empowerment: The Impact of Microfinance

- Investigating Sexism in Video Gaming Industry

- Female Leadership During Global Crises: Case Studies

Easy Feminism & Women’s Rights Topics

- Power of Women’s Protest: A Historical Study

- Feminist Movements’ Role in Shaping Public Policy

- Body Autonomy: A Key Aspect of Feminist Ideology

- Cyber Feminism: Women’s Rights in Digital Spaces

- Violence Against Women: International Legal Measures

- Feminist Pedagogy: Its Impact on Education

- Depiction of Women in Graphic Novels: A Feminist Lens

- Comparing Western and Eastern Feminist Movements

- Men’s Roles in Supporting Feminist Movements

- Impacts of Feminism on Marriage Institutions

- Rural Women’s Rights: Challenges and Progress

- Understanding Feminist Waves: From First to Fourth

- Inclusion of Women in Peace Negotiation Processes

- Influence of Feminism on Modern Advertising

- Indigenous Women’s Movements and Rights

- Reclaiming Public Spaces: Women’s Safety Concerns

- Roles of Feminist Literature in Social Change

- Women in Sports: Overcoming Stereotypes and Bias

- Feminism in the Context of Refugee Rights

- Media’s Roles in Shaping Feminist Narratives

- Women’s Rights in Prisons: An Overlooked Issue

- Motherhood Myths: A Feminist Examination

- Subverting the Male Gaze in Film and Television

- Feminist Critique of Traditional Masculinity Norms

- Rise of Female Entrepreneurship: A Feminist View

- Young Feminists: Shaping the Future of Women’s Rights

Interesting Feminism & Women’s Rights Topics

- Roles of Feminism in Promoting Mental Health Awareness

- Aging and Women’s Rights: An Overlooked Dimension

- Feminist Perspectives on Climate Change Impacts

- Women’s Rights in Military Service: Progress and Challenges

- Achieving Gender Parity in Academic Publishing

- Feminist Jurisprudence: Its Impact on Legal Structures

- Masculinity in Crisis: Understanding the Feminist Perspective

- Fashion Industry’s Evolution through Feminist Ideals

- Unheard Stories: Women in the Global Space Race

- Effects of Migration on Women’s Rights and Opportunities

- Women’s Land Rights: A Global Issue

- Intersection of Feminism and Disability Rights

- Portrayal of Women in Science Fiction: A Feminist Review

- Analyzing Post-Feminism: Its Origins and Implications

- Cyberbullying and Its Impact on Women: Measures for Protection

- Unveiling Gender Bias in Artificial Intelligence

- Reimagining Domestic Work Through the Lens of Feminism

- Black Women’s Hair Politics: A Feminist Perspective

- Feminist Ethical Considerations in Biomedical Research

- Promoting Gender Sensitivity in Children’s Literature

- Understanding the Phenomenon of Toxic Femininity

- Reconsidering Women’s Rights in the Context of Climate Migration

- Advancing Women’s Participation in Political Activism

Feminism Argumentative Essay Topics

- Intersectionality’s Impact on Modern Feminism

- Evolution of Feminist Thought: From First-Wave to Fourth-Wave

- Gender Wage Gap: Myths and Realities

- Workplace Discrimination: Tackling Unconscious Bias

- Feminist Theory’s Influence on Contemporary Art

- Intersection of Feminism and Environmental Activism

- Men’s Roles in the Feminist Movement

- Objectification in Media: A Feminist Perspective

- Misconceptions about Feminism: Addressing Stereotypes

- Feminism in the Classroom: The Role of Education

- Feminist Analysis of Reproductive Rights Policies

- Transgender Rights: An Extension of Feminism

- Intersection of Feminism and Racial Justice

- Body Shaming Culture: A Feminist Viewpoint

- Feminism’s Influence on Modern Advertising

- Patriarchy and Religion: A Feminist Critique

- Domestic Labor: Feminist Perspectives on Unpaid Work

- Sexism in Sports: The Need for Feminist Intervention

- The MeToo Movement’s Influence on Modern Feminism

- Feminism and the Fight for Equal Representation in Politics

- Women’s Rights in the Digital Age: A Feminist Examination

- Feminist Critique of Traditional Beauty Standards

- Globalization and Its Effects on Women’s Rights

- The Role of Feminism in LGBTQ+ Rights Advocacy

- Popular Culture and Its Reflection on Feminist Values

Controversial Feminist Research Paper Topics

- Intersectionality in Modern Feminist Movements: An Analysis

- Representation of Women in High-Powered Political Roles

- Cultural Appropriation Within the Feminist Movement: An Inquiry

- The Role of Feminism in Defining Beauty Standards

- Women’s Reproductive Rights: A Debate of Autonomy

- Feminism and Religion: The Question of Compatibility

- Male Allies in the Feminist Movement: An Evaluation

- Shift in Traditional Gender Roles: Feminist Perspective

- Impacts of Media on Perceptions of Feminism

- Dissecting the Wage Gap: A Feminist Examination

- Menstrual Equity: A Battle for Feminist Activists

- Feminism in Popular Music: Power or Appropriation?

- Climate Change: The Unseen Feminist Issue

- Education’s Role in Shaping Feminist Beliefs

- Power Dynamics in the Workplace: A Feminist Scrutiny

- Cyber-Feminism: Harnessing Digital Spaces for Activism

- Healthcare Disparities Faced by Women: An Analysis

- Transgender Women in Feminist Discourse: An Exploration

- Feminist Perspectives on Monogamy and Polyamory

- Feminist Analysis of Modern Advertising Campaigns

- Exploring Sexism in the Film Industry through a Feminist Lens

- Debunking Myths Surrounding the Feminist Movement

- Childcare Responsibilities and Their Feminist Implications

- Women’s Sports: Evaluating Equity and Feminist Advocacy

Feminist Research Paper Topics in Feminism Studies

- Evaluating Feminist Theories: From Radical to Liberal

- Women’s Health Care: Policies and Disparities

- Maternal Mortality: A Global Women’s Rights Issue

- Uncovering Sexism in the Tech Industry

- Critique of Binary Gender Roles in Children’s Toys

- Body Positivity Movement’s Influence on Feminism

- Relevance of Feminism in the Fight Against Human Trafficking

- Women in Coding: Breaking Stereotypes

- The Role of Women in Sustainable Agriculture

- Feminism in the Cosmetics Industry: A Dual-Edged Sword

- The Influence of Feminism on Modern Architecture

- Bridging the Gap: Women in Higher Education Leadership

- The Role of Feminism in Advancing LGBTQ+ Rights

- Menstrual Equity: A Key Women’s Rights Issue

- Women in Classical Music: Breaking Barriers

- Analyzing Gendered Language: A Feminist Approach

- Women’s Rights and Humanitarian Aid: The Interconnection

- Exploring the Role of Women in Graphic Design

- Addressing the Lack of Women in Venture Capitalism

- Impact of Feminism on Urban Planning and Design

- Maternal Labor in the Informal Economy: A Feminist Analysis

- Feminism’s Influence on Modern Dance Forms

- Exploring the Role of Women in the Renewable Energy Sector

- Women in Esports: An Emerging Frontier

- Child Marriage: A Grave Violation of Women’s Rights

Feminist Topics for Discussion

- Feminist Criticism of the Fashion Modelling Industry

- Domestic Violence: Feminist Legal Responses

- Analyzing the Success of Women-Only Workspaces

- Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A Human Rights Issue

- Women’s Role in the Evolution of Cryptocurrency

- Women and the Right to Water: A Feminist Perspective

- Gender Stereotypes in Comedy: A Feminist View

- Intersection of Animal Rights and Feminist Theory

- Roles of Feminism in the Fight Against Child Labor

- Representation of Women in Folklore and Mythology

- Women’s Rights in the Gig Economy: Issues and Solutions

- Revisiting Feminism in Post-Soviet Countries

- Women in the Space Industry: Present Status and Future Trends

- The Influence of Feminism on Culinary Arts

- Unraveling the Impact of Fast Fashion on Women Workers

- Feminist Perspectives on Genetic Engineering and Reproduction

- Assessing the Progress of Women’s Financial Literacy

- Sex Work and Feminism: A Controversial Discourse

- Women in Cybernetics: An Untapped Potential

- Uncovering the Women Behind Major Historical Events

- The Impact of the #MeToo Movement Globally

- Women’s Rights in the Cannabis Industry: Challenges and Progress

- Redefining Motherhood: The Intersection of Feminism and Adoption

- Roles of Feminist Movements in Combatting Child Abuse

Women’s Rights Essay Topics for Feminism

- Evolution of Women’s Rights in the 20th Century

- Roles of Women in World War II: Catalyst for Change

- Suffrage Movement: Driving Force Behind Women’s Empowerment

- Cultural Differences in Women’s Rights: A Comparative Study

- Feminist Movements and Their Global Impact

- Women’s Rights in Islamic Societies: Perceptions and Realities

- Glass Ceiling Phenomenon: Analysis and Impacts

- Pioneering Women in Science: Trailblazers for Equality

- Impacts of Media Portrayal on Women’s Rights

- Economic Autonomy for Women: Pathway to Empowerment

- Women’s Rights in Education: Global Perspective

- Gender Equality in Politics: Global Progress

- Intersectionality and Women’s Rights: Race, Class, and Gender

- Legal Milestones in Women’s Rights History

- Inequities in Healthcare: A Women’s Rights Issue

- Modern-Day Slavery: Women and Human Trafficking

- Climate Change: A Unique Threat to Women’s Rights

- Body Autonomy and Reproductive Rights: A Feminist Analysis

- Globalization’s Effect on Women’s Rights: Opportunities and Threats

- Gender Violence: An Erosion of Women’s Rights

- Indigenous Women’s Rights: Struggles and Triumphs

- Women’s Rights Activists: Unsung Heroes of History

- Empowerment Through Sports: Women’s Struggle and Success

- Balancing Act: Motherhood and Career in the 21st Century

- LGBTQ+ Women: Rights and Recognition in Different Societies

Women’s Rights Research Questions

- Evolution of Feminism: How Has the Movement Shifted Over Time?

- The Workplace and Gender Equality: How Effective Are Current Measures?

- Intersectionality’s Influence: How Does It Shape Women’s Rights Advocacy?

- Reproductive Rights: What Is the Global Impact on Women’s Health?

- Media Representation: Does It Affect Women’s Rights Perception?

- Gender Stereotypes: How Do They Impede Women’s Empowerment?

- Global Disparities: Why Do Women’s Rights Vary So Widely?

- Maternal Mortality: How Does It Reflect on Women’s Healthcare Rights?

- Education for Girls: How Does It Contribute to Gender Equality?

- Cultural Norms: How Do They Influence Women’s Rights?

- Leadership Roles: Are Women Adequately Represented in Positions of Power?

- Domestic Violence Laws: Are They Sufficient to Protect Women’s Rights?

- Roles of Technology: How Does It Impact Women’s Rights?

- Sexual Harassment Policies: How Effective Are They in Protecting Women?

- Pay Equity: How Can It Be Ensured for Women Globally?

- Politics and Gender: How Does Women’s Representation Shape Policy-Making?

- Child Marriage: How Does It Violate Girls’ Rights?

- Climate Change: How Does It Disproportionately Affect Women?

- Trafficking Scourge: How Can Women’s Rights Combat This Issue?

- Female Genital Mutilation: How Does It Contradict Women’s Rights?

- Armed Conflicts: How Do They Impact Women’s Rights?

- Body Autonomy: How Can It Be Safeguarded for Women?

- Women’s Suffrage: How Did It Pave the Way for Modern Women’s Rights?

- Men’s Role: How Can They Contribute to Women’s Rights Advocacy?

- Legal Frameworks: How Do They Support or Hinder Women’s Rights?

History of Women’s Rights Topics

- Emergence of Feminism in the 19th Century

- Roles of Women in the Abolitionist Movement

- Suffragette Movements: Triumphs and Challenges

- Eleanor Roosevelt and Her Advocacy for Women’s Rights

- Impacts of World War II on Women’s Liberation

- Radical Feminism in the 1960s and 1970s

- Pioneering Women in Politics: The First Female Senators

- Inception of the Equal Rights Amendment

- Revolutionary Women’s Health Activism

- Struggle for Reproductive Freedom: Roe vs. Wade

- Birth of the Women’s Liberation Movement

- Challenges Women Faced in the Civil Rights Movement

- Women’s Roles in the Trade Union Movement

- Intersectionality and Feminism: Examining the Role of Women of Color

- How Did the Women’s Rights Movement Impact Education?

- Sexuality, Identity, and Feminism: Stonewall Riots’ Impact

- Influence of Religion on Women’s Rights Activism

- Women’s Empowerment: The UN Conferences

- Impact of Globalization on Women’s Rights

- Women’s Movements in Non-Western Countries

- Women in Space: The Fight for Equality in NASA

- Achievements of Feminist Literature and Arts

- Evolution of the Women’s Sports Movement

- Advancement of Women’s Rights in the Digital Age

- Cultural Shifts: The Media’s Role in Promoting Women’s Rights

Feminism Essay Topics on Women’s Issues

- Career Challenges: The Gender Wage Gap in Contemporary Society

- Examining Microfinance: An Empowering Tool for Women in Developing Countries

- Pioneers of Change: The Role of Women in the Space Industry

- Exploring Beauty Standards: An Analysis of Global Perspectives

- Impacts of Legislation: Progress in Women’s Health Policies

- Maternity Leave Policies: A Comparative Study of Different Countries

- Resilience Through Struggles: The Plight of Female Refugees

- Technology’s Influence: Addressing the Digital Gender Divide

- Dissecting Stereotypes: Gender Roles in Children’s Media

- Influence of Female Leaders: A Look at Political Empowerment

- Social Media and Women: Effects on Mental Health

- Understanding Intersectionality: The Complexity of Women’s Rights

- Single Mothers: Balancing Parenthood and Economic Challenges

- Gaining Ground in Sports: A Look at Female Athletes’ Struggles

- Maternal Mortality: The Hidden Health Crisis

- Reproductive Rights: Women’s Control Over Their Bodies

- Feminism in Literature: Portrayal of Women in Classic Novels

- Deconstructing Patriarchy: The Impact of Gender Inequality

- Body Autonomy: The Battle for Abortion Rights

- Women in STEM: Barriers and Breakthroughs

- Female Soldiers: Their Role in Military Conflicts

- Human Trafficking: The Disproportionate Impact on Women

- Silent Victims: Domestic Violence and Women’s Health

To Learn More, Read Relevant Articles

385 Odyssey Essay Topics & Ideas

- 1 August 2023

415 Rogerian Essay Topics & Good Ideas

- 30 July 2023

- Thesis Statement Generator

- Online Summarizer

- Rewording Tool

- Topic Generator

- Essay Title Page Maker

- Conclusion Writer

- Academic Paraphraser

- Essay Writing Help

- Topic Ideas

- Writing Guides

- Useful Information

487 Feminism Essay Topics

Women make up half of the world’s population. How did it happen they were oppressed?

We are living in the era of the third wave of feminism, when women fight for equal rights in their professional and personal life. Public figures say that objectification and sexualization of women are not ok. Moreover, governments adopt laws that protect equal rights and possibilities for people of all genders, races, and physical abilities. Yes, it is also about feminism.

In this article, you will find 400+ feminism essay topics for students. Some raise the problems of feminism; others approach its merits. In addition, we have added a brief nuts-and-bolts course on the history and principal aspects of this social movement.

❗ Top 15 Feminism Essay Topics

- 💻 Feminism Research Topics

- 📜 History of Feminism Topics

- 🙋♀️ Topics on Feminism Movements

🔥 Famous Feminists Essay Topics

- 👩🎓 Topics on Women’s Rights in the World

- 👸 Antifeminism Essay Topics

📚 Topics on Feminism in Literature

🔗 references.

- Compare and contrast liberal and radical feminism.

- The problem of political representation of feminism.

- Is Hillary Clinton the most prominent feminist?

- How can feministic ideas improve our world?

- What is the glass ceiling, and how does it hinder women from reaching top positions?

- What can we do to combat domestic violence?

- Unpaid domestic work: Voluntary slavery?

- Why do women traditionally do social work?

- What are the achievements of feminism?

- Why is there no unity among the currents of feminism?

- Pornographic content should be banned in a civilized society.

- Does feminism threaten men?

- What is intersectional feminism, and why is it the most comprehensive feminist movement?

- Those who are not feminists are sexists.

- Why are women the “second gender?”

💻 Feminism Research Topics & Areas

Feminism is the belief in the equality of the sexes in social, economic, and political spheres. This movement originated in the West, but it has become represented worldwide. Throughout human history, women have been confined to domestic labor. Meanwhile, public life has been men’s prerogative. Women were their husband’s property, like a house or a cow. Today this situation has vastly improved, but many problems remain unresolved.

A feminism research paper aims to analyze the existing problems of feminism through the example of famous personalities, literary works, historical events, and so on. Women’s rights essay topics dwell on one of the following issues:

Healthcare & Reproductive Rights of Women

Women should be able to decide whether they want to have children or not or whether they need an abortion or not. External pressure or disapprobation is unacceptable. In many countries, abortions are still illegal. It is a severe problem because the female population attempts abortions without medical assistance in unhygienic conditions.

Economic Rights of Women

Women’s job applications are often rejected because they are expected to become mothers and require maternity leave. Their work is underpaid on a gender basis. They are less likely to be promoted to managerial positions because of the so-called “ glass ceiling .” All these problems limit women’s economic rights.

Women’s Political Rights

Yes, women have voting rights in the majority of the world’s countries. Why isn’t that enough? Because they are still underrepresented in almost all the world’s governments. Only four countries have 50% of female parliamentarians. Laws are approved by men and for men.

Family & Parenting

The British Office for National Statistics has calculated that women spend 78% more time on childcare than men. They also perform most of the unpaid domestic work. Meanwhile, increasingly more mothers are employed or self-employed. It isn’t fair, is it?

Virginity is a myth. Still, women are encouraged to preserve it until a man decides to marry her. Any expression of female sexuality is criticized (or “ slut-shamed “). We live in the 21st century, but old fossilized prejudices persist.

📜 History of Feminism Essay Topics

First wave of feminism & earlier.

- Ancient and medieval promoters of feminist ideas.

- “Debate about women” in medieval literature and philosophy.

- The emergence of feminism as an organized movement.

- Enlightenment philosophers’ attitudes towards women.

- The legal status of women in Renaissance.

- Women’s Liberation Movement Evolution in the US.

- Mary Wollstonecraft’s views on women’s rights.

- Sociopolitical background of the suffrage movement.

- The most prominent suffrage activists.

- The Liberation Theme Concerning Women.

- “Declaration of sentiments”: key points and drawbacks.

- What was special about Sojourner Truth and her famous speech?

- The significance of the first feminist convention in Seneca Falls.

- The National Woman Suffrage Association: goals and tactics.

- The influence of abolitionism on feminism ideas.

- Why did some women prefer trade unions to feminism?

- Radical feminists’ criticism of the suffrage movement.

- The UK suffragists’ approach to gaining voting rights for women.

- Alice Paul and Emmeline Pankhurst’s role in the suffrage movement.

- The Nineteenth Amendment: the essence and significance.

- Infighting in the post-suffrage era.

Second Wave of Feminism Essay Titles

- How did second-wave feminism differ from the suffrage movement?

- The roots of the second wave of feminism.

- John Kennedy’s policies concerning women’s rights.

- Eleanor Roosevelt’s contribution to feminism.

- Debates on gender equality in the late 1960s.

- Feminism activists’ achievements in 1960-1970.

- What was the focus of second-wave feminist research?

- Why was there no comprehensive feminist ideology?

- Anarcho-, individualist, “Amazon,” and separatist feminism: key ideas.

- The nature of liberal feminism.

- How did liberal and radical feminism differ?

- Why was cultural feminism also called “difference” feminism?

- Liberal and Postmodernist Theories of Feminism.

- What is the difference between liberal and radical feminism?

- Black feminists’ challenges and input to the fight for equity.

- Sociocultural differences in views on female liberation.

- The globalization of feminism: positive and negative aspects.