UNICEF Data : Monitoring the situation of children and women

GOAL 3: GOOD HEALTH AND WELL-BEING

Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.

Goal 3 aims to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all, at all ages. Health and well-being are important at every stage of one’s life, starting from the beginning. This goal addresses all major health priorities: reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health; communicable and non-communicable diseases; universal health coverage; and access for all to safe, effective, quality and affordable medicines and vaccines.

SDG 3 aims to prevent needless suffering from preventable diseases and premature death by focusing on key targets that boost the health of a country’s overall population. Regions with the highest burden of disease and neglected population groups and regions are priority areas. Goal 3 also calls for deeper investments in research and development, health financing and health risk reduction and management.

UNICEF’s role in contributing to Goal 3 centres on healthy pregnancies ( maternal mortality and skilled birth attendant), healthy childhoods (under-five and neonatal mortality) as well as vaccine coverage. UNICEF also contributes to monitoring elements of the universal health coverage indicator.

UNICEF is custodian for global monitoring of two indicators that measure progress towards Goal 3 as it relates to children: Indicator 3.2.1 Under-five mortality rate and Indicator 3.2.2 Neonatal mortality rate. UNICEF is also co-custodian for Indicator 3.1.2 Proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel and for Indicator 3.b.1 Proportion of the target population covered by all vaccines included in their national programme.

Child-related SDG indicators

Target 3.1 by 2030, reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100,000 live births, maternal mortality ratio (number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births).

- Indicator definition

- Computation method

- Comments & limitations

Explore the data

Maternal mortality refers to deaths due to complications from pregnancy or childbirth. Accurate measurement of maternal mortality remains challenging and many deaths still go uncounted. Many countries still lack well functioning civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS) systems, and where such systems do exist, reporting errors – whether incompleteness (unregistered deaths, also known as “missing”) or misclassification of cause of death – continue to pose a major challenge to data accuracy.

The maternal mortality ratio (MMR) is defined as the number of maternal deaths during a given time period per 100,000 live births during the same time period. It depicts the risk of maternal death relative to the number of live births and essentially captures the risk of death in a single pregnancy or a single live birth.

Maternal deaths: The annual number of female deaths from any cause related to or aggravated by pregnancy or its management (excluding accidental or incidental causes) during pregnancy and childbirth or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, expressed per 100,000 live births, for a specified time period.

Maternal death: The death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management (from direct or indirect obstetric death), but not from accidental or incidental causes.

Pregnancy-related death: The death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the cause of death. Late maternal death: The death of a woman from direct or indirect obstetric causes, more than 42 days, but less than one year after termination of pregnancy

The maternal mortality ratio can be calculated by dividing recorded (or estimated) maternal deaths by total recorded (or estimated) live births in the same period and multiplying by 100,000. Measurement requires information on pregnancy status, timing of death (during pregnancy, childbirth, or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy), and cause of death. The maternal mortality ratio can be calculated directly from data collected through vital registration systems, household surveys or other sources. There are often data quality problems, particularly related to the underreporting and misclassification of maternal deaths. Therefore, data are often adjusted in order to take these data quality issues into account. Some countries undertake these adjustments or corrections as part of specialized/confidential enquiries or administrative efforts embedded within maternal mortality monitoring programmes.

For countries with data available on maternal mortality, the expected proportion of non-HIV- related maternal deaths was based on country and regional random effects, whereas for countries with no data available, predictions were derived using regional random effects only.

Estimation of HIV-related indirect maternal deaths For countries with generalized HIV epidemics and high HIV prevalence, HIV/AIDS is a leading cause of death during pregnancy and post-delivery. There is also some evidence from community studies that women with HIV infection have a higher risk of maternal death, although this may be offset by lower fertility. If HIV is prevalent, there will also be more incidental HIV deaths among pregnant and postpartum women. When estimating maternal mortality in these countries, it is, thus, important to differentiate between incidental HIV deaths (non-maternal deaths) and HIV-related indirect maternal deaths (maternal deaths caused by the aggravating effects of pregnancy on HIV) among HIV-positive pregnant and postpartum women who have died (i.e. among all HIV-related deaths occurring during pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium).

For observed PMs, we assumed that the total reported maternal deaths are a combination of the proportion of reported non-HIV-related maternal deaths and the proportion of reported HIV- related (indirect) maternal deaths, where the latter is given by a*v for observations with a “pregnancy-related death” definition and a*v*u for observations with a “maternal death” definition.

The extent of maternal mortality in a population is essentially the combination of two factors:

1. The risk of death in a single pregnancy or a single live birth. 2. The fertility level (i.e. the number of pregnancies or births that are experienced by women of reproductive age).

The maternal mortality ratio (MMR) is defined as the number of maternal deaths during a given time period per 100,000 live births during the same time period. It depicts the risk of maternal death relative to the number of live births and essentially captures (1) above.

By contrast, the maternal mortality rate (MMRate) is calculated as the number of maternal deaths divided by person-years lived by women of reproductive age. The MMRate captures both the risk of maternal death per pregnancy or per total birth (live birth or stillbirth), and the level of fertility in the population.

In addition to the MMR and the MMRate, it is possible to calculate the adult lifetime risk of maternal mortality for women in the population. An alternative measure of maternal mortality, the proportion of deaths among women of reproductive age that are due to maternal causes (PM), is calculated as the number of maternal deaths divided by the total deaths among women aged 15–49 years.

Related Statistical measures of maternal mortality:

Maternal mortality ratio (MMR): Number of maternal deaths during a given time period per 100,000 live births during the same time period.

Maternal mortality rate (MMRate): Number of maternal deaths divided by person-years lived by women of reproductive age.

Adult lifetime risk of maternal death: The probability that a 15-year-old woman will die eventually from a maternal cause.

The proportion of deaths among women of reproductive age that are due to maternal causes (PM): The number of maternal deaths in a given time period divided by the total deaths among women aged 15–49 years.

Click on the button below to explore the data behind this indicator.

Skilled birth attendant – Proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel

- Sources of discrepancies

Having a skilled health care provider at the time of childbirth is an important lifesaving intervention for both women and newborns. Not having access to this key assistance is detrimental to women’s and newborns’ health because it could cause adverse health outcomes such as the death of the women and/or the newborns or long lasting morbidity. Achieving universal coverage is therefore essential for reducing maternal and newborn mortality and morbidity.

Proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel (generally doctors, nurses or midwives but can refer to other health professionals providing childbirth care) is the proportion of childbirths attended by skilled health personnel. According to the current definition (1) these are competent maternal and newborn health (MNH) professionals educated, trained and regulated to national and international standards.

They are competent to:

(i) provide and promote evidence-based, human-rights based, quality, socio-culturally sensitive and dignified care to women and newborns;

(ii) facilitate physiological processes during labour and delivery to ensure a clean and positive childbirth experience; and

(iii) identify and manage or refer women and/or newborns with complications.

Discrepancies are possible if there are national figures compiled at the health facility level. These would differ from the global figures, which are typically based on survey data collected at the household level. In terms of survey data, some survey reports may present a total percentage of births attended by a skilled health professional that does not conform to the MDG definition (e.g., total includes provider that is not considered skilled, such as a community health worker). In that case, the percentage delivered by a physician, nurse, or a midwife are totalled and entered into the global database as the MDG estimate. In some countries where skilled attendant at birth is not available, birth in a health facility (institutional births) is used instead. This is frequent among Latin American countries, where the proportion of institutional births is very high. Nonetheless, it should be noted that institutional births may underestimate the percentage of births with skilled attendant.

TARGET 3.2 By 2030, end preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5 years of age, with all countries aiming to reduce neonatal mortality to at least as low as 12 per 1,000 live births and under-5 mortality to at least as low as 25 per 1,000 live births

Under-five mortality rate.

Mortality rates among young children are a key output indicator for child health and well-being, and, more broadly, for social and economic development. This is a closely watched public health indicator because it reflects the access of children and communities to basic health interventions such as vaccination, medical treatment of infectious diseases and adequate nutrition.

Probability of dying between birth and exactly 5 years of age, expressed per 1,000 live births

The under-five mortality rate as defined here is, strictly speaking, not a rate (i.e. the number of deaths divided by the number of population at risk during a certain period of time), but a probability of death derived from a life table and expressed as a rate per 1000 live births.

The UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME) estimates are derived from national data from censuses, surveys or vital registration systems. The UN IGME does not use any covariates to derive its estimates. It only applies a curve fitting method to good-quality empirical data to derive trend estimates after data quality assessment. In most cases, the UN IGME estimates are close to the underlying data. The UN IGME aims to minimize the errors for each estimate, harmonize trends over time and produce up-to-date and properly assessed estimates. The UN IGME applies the Bayesian B-splines bias-reduction model to empirical data to derive trend estimates of under-five mortality for all countries. See references for details.

For the underlying data mentioned above, the most frequently used methods are as follows:

Civil registration: The under-five mortality rate can be derived from a standard period abridged life table using the age-specific deaths and mid-year population counts from civil registration data to calculate death rates, which are then converted into age-specific probabilities of dying.

Census and surveys: An indirect method is used based on a summary birth history, a series of questions asked of each woman of reproductive age as to how many children she has ever given birth to and how many are still alive. The Brass method and model life tables are then used to obtain an estimate of under-five and infant mortality rates. Censuses often include questions on household deaths in the last 12 months, which can be used to calculate mortality estimates.

Surveys: A direct method is used based on a full birth history, a series of detailed questions on each child a woman has given birth to during her lifetime. Neonatal, post-neonatal, infant, child and under-five mortality estimates can be derived from the full birth history module.

The UN IGME estimates are derived based on national data. Countries often use a single source as their official estimates or apply methods different from the UN IGME methods to derive estimates. The differences between the UN IGME estimates and national official estimates are usually not large if empirical data has good quality.

Many countries lack a single source of high-quality data covering the last several decades. Data from different sources require different calculation methods and may suffer from different errors, for example random errors in sample surveys or systematic errors due to misreporting. As a result, different surveys often yield widely different estimates of under-five mortality for a given time period and available data collected by countries are often inconsistent across sources. It is important to analyse, reconcile and evaluate all data sources simultaneously for each country. Each new survey or data point must be examined in the context of all other sources, including previous data. Data suffer from sampling or non-sampling errors (such as misreporting of age and survivor selection bias; underreporting of child deaths is also common). UN IGME assesses the quality of underlying data sources and adjusts data when necessary. Furthermore, the latest data produced by countries often are not current estimates but refer to an earlier reference period. Thus, the UN IGME also projects estimates to a common reference year. In order to reconcile these differences and take better account of the systematic biases associated with the various types of data inputs, the UN IGME has developed an estimation method to fit a smoothed trend curve to a set of observations and to extrapolate that trend to a defined time point. The UN IGME aims to minimize the errors for each estimate, harmonize trends over time and produce up-to-date and properly assessed estimates of child mortality. In the absence of error-free data, there will always be uncertainty around data and estimates. To allow for added comparability, the UN IGME generates such estimates with uncertainty bounds. Applying a consistent methodology also allows for comparisons between countries, despite the varied number and types of data sources. UN IGME applies a common methodology across countries and uses original empirical data from each country but does not report figures produced by individual countries using other methods, which would not be comparable to other country estimates.

Neonatal mortality rate

The neonatal mortality rate is the probability that a child born in a specific year or period will die during the first 28 completed days of life if subject to age-specific mortality rates of that period, expressed per 1000 live births.

Neonatal deaths (deaths among live births during the first 28 completed days of life) may be subdivided into early neonatal deaths, occurring during the first 7 days of life, and late neonatal deaths, occurring after the 7th day but before the 28th completed day of life.

The UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME) estimates are derived from nationally representative data from censuses, surveys or vital registration systems. The UN IGME does not use any covariates to derive its estimates. It only applies a curve fitting method to good-quality empirical data to derive trend estimates after data quality assessment. In most cases, the UN IGME estimates are close to the underlying data. The UN IGME aims to minimize the errors for each estimate, harmonize trends over time and produce up-to-date and properly assessed estimates. The UN IGME produces neonatal mortality rate estimates with a Bayesian spline regression model which models the ratio of neonatal mortality rate / (under-five mortality rate – neonatal mortality rate). Estimates of NMR are obtained by recombining the estimates of the ratio with the UN IGME-estimated under-five mortality rate. See the references for details.

Civil registration: Number of children who died during the first 28 days of life and the number of births used to calculate neonatal mortality rates.

Censuses and surveys: Censuses and surveys often include questions on household deaths in the last 12 months, which can be used to calculate mortality estimates.

Many countries lack a single source of high-quality data covering the last several decades. Data from different sources require different calculation methods and may suffer from different errors, for example random errors in sample surveys or systematic errors due to misreporting. As a result, different surveys often yield widely different estimates of neonatal mortality for a given time period and available data collected by countries are often inconsistent across sources. It is important to analyse, reconcile and evaluate all data sources simultaneously for each country. Each new survey or data point must be examined in the context of all other sources, including previous data. Data suffer from sampling or non-sampling errors (such as misreporting of age and survivor selection bias; underreporting of child deaths is also common). UN IGME assesses the quality of underlying data sources and adjusts data when necessary. Furthermore, the latest data produced by countries often are not current estimates but refer to an earlier reference period. Thus, the UN IGME also projects estimates to a common reference year. In order to reconcile these differences and take better account of the systematic biases associated with the various types of data inputs, the UN IGME has developed an estimation method to fit a smoothed trend curve to a set of observations and to extrapolate that trend to a defined time point. The UN IGME aims to minimize the errors for each estimate, harmonize trends over time and produce up-to-date and properly assessed estimates of child mortality. In the absence of error-free data, there will always be uncertainty around data and estimates. To allow for added comparability, the UN IGME generates such estimates with uncertainty bounds. Applying a consistent methodology also allows for comparisons between countries, despite the varied number and types of data sources. UN IGME applies a common methodology across countries and uses original empirical data from each country but does not report figures produced by individual countries using other methods, which would not be comparable to other country estimates.

TARGET 3.3 By 2030, end the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and neglected tropical diseases and combat hepatitis, water-borne diseases and other communicable diseases

Estimated incidence rate (new hiv infection per 1,000 uninfected population).

This indicator is used to measure progress towards ending the AIDS epidemic. The overarching goal of the global AIDS response is to reduce the number of people newly infected to fewer than 500,000 in 2020 and fewer than 200,000 in 2030. Monitoring the rate of people newly infected over time measures the progress towards achieving this goal. Disaggregation by sex, age and key populations is important to characterize how the epidemic is evolving, to monitor equity of access to services and to support the planning of programme responses in specific age groups such as children under five, adolescents and young adults, as well as key populations.

Annual number of new HIV infections per 1,000 uninfected population

Longitudinal data on individuals are the best source of data but are rarely available for large populations. Special diagnostic tests in surveys or from health facilities can be used to obtain data on HIV incidence. HIV incidence is thus modelled using the Spectrum software.

Malaria incidence per 1,000 population

This indicator is used to measure trends in malaria morbidity and to identify locations where the risk of disease is highest. With this information, programmes can respond to unusual trends, such as epidemics, and direct resources to the populations most in need. This data also serves to inform global resource allocation for malaria such as when defining eligibility criteria for Global Fund finance.

Incidence of malaria is defined as the number of new cases of malaria per 1,000 people at risk each year.

Case of malaria is defined as the occurrence of malaria infection in a person whom the presence of malaria parasites in the blood has been confirmed by a diagnostic test. The population considered is the population at risk of the disease.

Malaria incidence (1) is expressed as the number of new cases per 100,000 population per year with the population of a country derived from projections made by the UN Population Division and the total proportion at risk estimated by a country’s National Malaria Control Programme. More specifically, the country estimates what is the proportion at high risk (H) and what is the proportion at low risk (L) and the total population at risk is estimated as UN Population x (H + L).

The total number of new cases, T, is estimated from the number of malaria cases reported by a Ministry of Health which is adjusted to take into account (i) incompleteness in reporting systems (ii) patients seeking treatment in the private sector, self-medicating or not seeking treatment at all, and (iii) potential over-diagnosis through the lack of laboratory confirmation of cases. The procedure, which is described in the World malaria report 2009 (2), combines data reported by NMCPs (reported cases, reporting completeness and likelihood that cases are parasite positive) with data obtained from nationally representative household surveys on health-service use.

𝑇=( a + (𝑐 × 𝑒) ⁄ 𝑑) × (1 + h ⁄𝑔 + ((1−𝑔−h)/2) ⁄ 𝑔)

where: a is malaria cases confirmed in public sector b is suspected cases tested c is presumed cases (not tested but treated as malaria) d is reporting completeness e is test positivity rate (malaria positive fraction) = a/b f is cases in public sector, calculated by (a + (c x e))/d g is treatment seeking fraction in public sector h is treatment seeking fraction in private sector i is the fraction not seeking treatment, calculated by (1-g-h)/2 j is cases in private sector, calculated by f x h/g k is cases not in private and not in public, calculated by f x i/g T is total cases, calculated by f + j + k.

To estimate the uncertainty around the number of cases, the test positivity rate was assumed to have a normal distribution centred on the Test positivity rate value and standard deviation defined as 0.244 × Test positivity rate 0.5547 and truncated to be in the range 0, 1.

Reporting completeness was assumed to have one of three distributions, depending on the range or value reported by the NMCP. -If the range was greater than 80% the distribution was assumed to be triangular, with limits of 0.8 and 1 and the peak at 0.8. – If the range was greater than 50% then the distribution was assumed to be rectangular, with limits of 0.5 and 0.8. -Finally, if the range was lower than 50% the distribution was assumed to be triangular, with limits of 0 and 0.5 and the peak at 0.5 (3).

If the reporting completeness was reported as a value and was greater than 80%, a beta distribution was assumed with a mean value of the reported value (maximum of 95%) and confidence intervals (CIs) of 5% round the mean value.

The proportions of children for whom care was sought in the private sector and in the public sector were assumed to have a beta distribution, with the mean value being the estimated value in the survey and the standard deviation calculated from the range of the estimated 95% confidence intervals (CI) divided by 4. The proportion of children for whom care was not sought was assumed to have a rectangular distribution, with the lower limit 0 and upper limit calculated as 1 minus the proportion that sought care in public or private sector.

Values for the proportion seeking care were linearly interpolated between the years that have a survey, and were extrapolated for the years before the first or after the last survey. Missing values for the distributions were imputed using a mixture of the distribution of the country, with equal probability for the years where values were present or, if there was no value at all for any year in the country, a mixture of the distribution of the region for that year. The data were analysed using the R statistical software.

Confidence intervals were obtained from 10000 drawns of the convoluted distributions. (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bolivia (Plurinational State of), Botswana, Brazil, Cambodia, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Eritrea, Ethiopia, French Guiana, Gambia, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Madagascar, Mauritania, Mayotte, Myanmar, Namibia, Nepal, Nicaragua, Pakistan, Panama, Papua New Guinea, Peru, Philippines, Rwanda, Senegal, Solomon Islands, Timor-Leste, Vanuatu, Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of), Viet Nam, Yemen and Zimbabwe. For India, the values were obtained at subnational level using the same methodology, but adjusting the private sector for an additional factor due to the active case detection, estimated as the ratio of the test positivity rate in the active case detection over the test positivity rate for the passive case detection. This factor was assumed to have a normal distribution, with mean value and standard deviation calculated from the values reported in 2010. Bangladesh, Bolivia, Botswana, Brazil, Cabo Verde, Colombia, Dominican Republic, French Guiana, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Myanmar (since 2013), Rwanda, Suriname and Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of) report cases from the private and public sector together; therefore, no adjustment for private sector seeking treatment was made.

For some high-transmission African countries the quality of case reporting is considered insufficient for the above formulae to be applied. In such cases estimates of the number of malaria cases are derived from information on parasite prevalence obtained from household surveys.

First, data on parasite prevalence from nearly 60 000 survey records were assembled within a spatiotemporal Bayesian geostatistical model, along with environmental and sociodemographic covariates, and data distribution on interventions such as ITNs, antimalarial drugs and IRS. The geospatial model enabled predictions of Plasmodium falciparum prevalence in children aged 2–10 years, at a resolution of 5 × 5 km2, throughout all malaria endemic African countries for each year from 2000 to 2016 (see http://www.map.ox.ac.uk/making-maps/ for methods on the development of maps by the Malaria Atlas Project).

Second, an ensemble model was developed to predict malaria incidence as a function of parasite prevalence.

The model was then applied to the estimated parasite prevalence in order to obtain estimates of the malaria case incidence at 5 × 5 km2 resolution for each year from 2000 to 2016.

Data for each 5 × 5 km2 area were then aggregated within country and regional boundaries to obtain both national and regional estimates of malaria cases. (Benin, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Guinea, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Togo and Zambia). For most of the elimination countries, the number of indigenous cases registered by the NMCPs are reported without further adjustments. (Algeria, Argentina, Belize, Bhutan, Cabo Verde, China, Comoros, Costa Rica, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Djibuti, Ecuador, El Salvador, Iran (Islamic Republic of), Iraq, Malaysia, Mexico, Paraguay, Republic of Korea, Sao Tome and Principe, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Suriname, Swaziland and Thailand).

The estimated incidence can differ from the incidence reported by a Ministry of Health which can be affected by: – the completeness of reporting: the number of reported cases can be lower than the estimated cases if the percentage of health facilities reporting in a month is less than 100% – the extent of malaria diagnostic testing (the number of slides examined or RDTs performed) – the use of private health facilities which are usually not included in reporting systems. – the indicator is estimated only where malaria transmission occurs.

TARGET 3.7 By 2030, ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health-care services, including for family planning, information and education, and the integration of reproductive health into national strategies and programmes

Adolescent birth rate (number of live births to adolescent women per 1,000 adolescent women).

Reducing adolescent fertility and addressing the multiple factors underlying it are essential for improving sexual and reproductive health and the social and economic well-being of adolescents. Preventing births very early in a woman’s life is an important measure to improve maternal health and reduce infant mortality. Furthermore, women having children at an early age experience a curtailment of their opportunities for socio-economic improvement, particularly because young mothers are unlikely to keep on studying and, if they need to work, may find it especially difficult to combine family and work responsibilities. The adolescent birth rate also provides indirect evidence on access to pertinent health services since young people, and in particular unmarried adolescent women, often experience difficulties in access to sexual and reproductive health services.

The adolescent birth rate represents the risk of childbearing among females in a particular age group. The adolescent birth rate among women aged 15-19 years is also referred to as the age-specific fertility rate for women aged 15-19

The adolescent birth rate represents the risk of childbearing among females in a particular age group. The adolescent birth rate (ABR) is also referred to as the age-specific fertility rate (ASFR) for ages 15-19 years, a designation commonly used in the context of calculation of total fertility estimates. A related measure is the proportion of adolescent fertility, measured as the percentage of total fertility contributed by women aged 15-19.

The adolescent birth rate is computed as a ratio.

Numerator – the number of live births to women aged 15-19 years Denominator – the estimate of the exposure to childbearing by women aged 15-19 years

The computation is the same for the age group 10-14 years. The numerator and the denominator are calculated differently for civil registration, survey and census data.

In the case of civil registration data, the numerator is the registered number of live births born to women aged 15-19 years during a given year, and the denominator is the estimated or enumerated population of women aged 15-19 years.

In the case of survey data, the numerator is the number of live births obtained from retrospective birth histories of the interviewed women who were 15-19 years of age at the time of the births during a reference period before the interview, and the denominator is person-years lived between the ages of 15 and 19 years by the interviewed women during the same reference period.

The reported observation year corresponds to the middle of the reference period. For some surveys without data on retrospective birth histories, computation of the adolescent birth rate is based on the date of last birth or the number of births in the 12 months preceding the survey.

With census data, the adolescent birth rate is computed on the basis of the date of last birth or the number of births in the 12 months preceding the enumeration. The census provides both the numerator and the denominator for the rates. In some cases, the rates based on censuses are adjusted for under-registration based on indirect methods of estimation.

For some countries with no other reliable data, the ‘own-children’ method of indirect estimation provides estimates of the adolescent birth rate for a number of years before the census.

For a thorough treatment of the different methods of computation, see Handbook on the Collection of Fertility and Mortality Data, United Nations Publication, Sales No. E.03.XVII.11 (publicly accessible at http://unstats.un.org/unsd/publication/SeriesF/SeriesF_92E.pdf ). Indirect methods of estimation are analyzed in Manual X: Indirect Techniques for Demographic Estimation, United Nations Publication, Sales No. E.83.XIII.2 (publicly accessible at http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/Manual_X/Manual_X.htm ).

Discrepancies between the sources of data at the country level are common and the level of the adolescent birth rate depends in part on the source of the data selected.

For civil registration, rates are subject to limitations which depend on the completeness of birth registration, the treatment of infants born alive but that die before registration or within the first 24 hours of life, the quality of the reported information relating to age of the mother, and the inclusion of births from previous periods.

The population estimates may be subject to limitations connected to age misreporting and coverage. For survey and census data, both the numerator and denominator come from the same population. The main limitations concern age misreporting, birth omissions, misreporting the date of birth of the child, and sampling variability in the case of surveys.

With respect to estimates of the adolescent birth rate among females aged 10-14 years, comparative evidence suggests that a very small proportion of births in this age group occur to females below age 12. Other evidence based on retrospective birth history data from surveys indicates that women aged 15-19 years are less likely to report first births before age 15 than women from the same birth cohort when asked five years later at ages 20–24 years.

TARGET 3.8 Achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all

Proportion of the target population covered by essential health services.

Coverage of essential health services (defined as the average coverage of essential services based on tracer interventions that include reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health, infectious diseases, non-communicable diseases and service capacity and access, among the general and the most disadvantaged population).

Target 3.8 is defined as “Achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all”. The concern is with all people and communities receiving the quality health services they need (including medicines and other health products), without financial hardship.

Indicator 3.8.1 is for health service coverage and indicator 3.8.2 focuses on health expenditures in relation to a household’s budget to identify financial hardship caused by direct health care payments. Taken together, indicators 3.8.1 and 3.8.2 are meant to capture the service coverage and financial protection dimensions, respectively, of target 3.8. These two indicators should be always monitored jointly.

The indicator is an index reported on a unitless scale of 0 to 100, which is computed as the geometric mean of 14 tracer indicators of health service coverage.

The index of health service coverage is computed as the geometric means of 14 tracer indicators. The 14 indicators are listed below and detailed metadata for each of the components are given online ( http://www.who.int/healthinfo/universal_health_coverage/UHC_Tracer_Indicators_Metadata.pdf ) and Annex 1. The tracer indicators are as follows, organized by four broad categories of service coverage:

I. Reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health 1. Family planning: Percentage of women of reproductive age (15−49 years) who are married or in- union who have their need for family planning satisfied with modern methods 2. Pregnancy and delivery care: Percentage of women aged 15-49 years with a live birth in a given time period who received antenatal care four or more times 3. Child immunization: Percentage of infants receiving three doses of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis containing vaccine 4. Child treatment: Percentage of children under 5 years of age with suspected pneumonia (cough and difficult breathing NOT due to a problem in the chest and a blocked nose) in the two weeks preceding the survey taken to an appropriate health facility or provider

II. Infectious diseases 5. Tuberculosis: Percentage of incident TB cases that are detected and successfully treated 6. HIV/AIDS: Percentage of people living with HIV currently receiving antiretroviral therapy 7. Malaria: Percentage of population in malaria-endemic areas who slept under an insecticide-treated net the previous night [only for countries with high malaria burden] 8. Water and sanitation: Percentage of households using at least basic sanitation facilities

III. Noncommunicable diseases 9. Hypertension: Age-standardized prevalence of non-raised blood pressure (systolic blood pressure <140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg) among adults aged 18 years and older 10. Diabetes: Age-standardized mean fasting plasma glucose (mmol/L) for adults aged 18 years and older 11. Tobacco: Age-standardized prevalence of adults >=15 years not smoking tobacco in last 30 days (SDG indicator 3.a.1, metadata available here)

IV. Service capacity and access 12. Hospital access: Hospital beds per capita, relative to a maximum threshold of 18 per 10,000 population 13. Health workforce: Health professionals (physicians, psychiatrists, and surgeons) per capita, relative to maximum thresholds for each cadre (partial overlap with SDG indicator 3.c.1, see metadata here) 14. Health security: International Health Regulations (IHR) core capacity index, which is the average percentage of attributes of 13 core capacities that have been attained (SDG indicator 3.d.1, see metadata here)

The index is computed with geometric means, based on the methods used for the Human Development Index. The calculation of the 3.8.1 indicator requires first preparing the 14 tracer indicators so that they can be combined into the index, and then computing the index from those values. The 14 tracer indicators are first all placed on the same scale, with 0 being the lowest value and 100 being the optimal value. For most indicators, this scale is the natural scale of measurement, e.g., the percentage of infants who have been immunized ranges from 0 to 100 percent. However, for a few indicators additional rescaling is required to obtain appropriate values from 0 to 100, as follows: – Rescaling based on a non-zero minimum to obtain finer resolution (this “stretches” the distribution across countries): prevalence of non-raised blood pressure and prevalence of non- use of tobacco are both rescaled using a minimum value of 50%. rescaled value = (X-50)/(100-50)*100 – Rescaling for a continuous measure: mean fasting plasma glucose, which is a continuous measure (units of mmol/L), is converted to a scale of 0 to 100 using the minimum theoretical biological risk (5.1 mmol/L) and observed maximum across countries (7.1 mmol/L). rescaled value = (7.1 – original value)/(7.1-5.1)*100 – Maximum thresholds for rate indicators: hospital bed density and health workforce density are both capped at maximum thresholds, and values above this threshold are held constant at 100. These thresholds are based on minimum values observed across OECD countries. rescaled hospital beds per 10,000 = minimum(100, original value / 18*100) rescaled physicians per 1,000 = minimum(100, original value / 0.9*100) rescaled psychiatrists per 100,000 = minimum(100, original value / 1*100) rescaled surgeons per 100,000 = minimum(100, original value / 14*100) Once all tracer indicator values are on a scale of 0 to 100, geometric means are computed within each of the four health service areas, and then a geometric mean is taken of those four values. If the value of a tracer indicator happens to be zero, it is set to 1 (out of 100) before computing the geometric mean. The following diagram illustrates the calculations.

Note that in countries with low malaria burden, the tracer indicator for use of insecticide-treated nets is dropped from the calculation.

These tracer indicators are meant to be indicative of service coverage, not a complete or exhaustive list of health services and interventions that are required for universal health coverage. The 14 tracer indicators were selected because they are well-established, with available data widely reported by countries (or expected to become widely available soon). Therefore, the index can be computed with existing data sources and does not require initiating new data collection efforts solely to inform the index.

TARGET 3.9 By 2030, substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination

Mortality rate attributed to household and ambient air pollution.

As part of a broader project to assess major risk factors to health, the mortality resulting from exposure to ambient (outdoor) air pollution and household (indoor) air pollution from polluting fuel use for cooking was assessed. Ambient air pollution results from emissions from industrial activity, households, cars and trucks which are complex mixtures of air pollutants, many of which are harmful to health. Of all of these pollutants, fine particulate matter has the greatest effect on human health. By polluting fuels is understood as wood, coal, animal dung, charcoal, and crop wastes, as well as kerosene.

Air pollution is the biggest environmental risk to health. The majority of the burden is borne by the populations in low and middle-income countries.

The mortality attributable to the joint effects of household and ambient air pollution can be expressed as: Number of deaths, Death rate. Death rates are calculated by dividing the number of deaths by the total population (or indicated if a different population group is used, e.g. children under 5 years).

Evidence from epidemiological studies have shown that exposure to air pollution is linked, among others, to the important diseases taken into account in this estimate: – Acute respiratory infections in young children (estimated under 5 years of age) – Cerebrovascular diseases (stroke) in adults (estimated above 25 years) – Ischaemic heart diseases (IHD) in adults (estimated above 25 years) – Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in adults (estimated above 25 years); and – Lung cancer in adults (estimated above 25 years)

The mortality resulting from exposure to ambient (outdoor) air pollution and household (indoor) air pollution from polluting fuels use for cooking was assessed. Ambient air pollution results from emissions from industrial activity, households, cars and trucks which are complex mixtures of air pollutants, many of which are harmful to health. Of all of these pollutants, fine particulate matter has the greatest effect on human health. By polluting fuels is understood kerosene, wood, coal, animal dung, charcoal, and crop wastes.

Attributable mortality is calculated by first combining information on the increased (or relative) risk of a disease resulting from exposure, with information on how widespread the exposure is in the population (e.g. the annual mean concentration of particulate matter to which the population is exposed, proportion of population relying primarily on polluting fuels for cooking).

This allows calculation of the ‘population attributable fraction’ (PAF), which is the fraction of disease seen in a given population that can be attributed to the exposure (e.g in that case of both the annual mean concentration of particulate matter and exposure to polluting fuels for cooking).

Applying this fraction to the total burden of disease (e.g. cardiopulmonary disease expressed as deaths), gives the total number of deaths that results from exposure to that particular risk factor (in the example given above, to ambient and household air pollution).

To estimate the combined effects of risk factors, a joint population attributable fraction is calculated, as described in Ezzati et al (2003).

The mortality associated with household and ambient air pollution was estimated based on the calculation of the joint population attributable fractions assuming independently distributed exposures and independent hazards as described in (Ezzati et al, 2003).

The joint population attributable fraction (PAF) were calculated using the following formula: PAF=1-PRODUCT (1-PAFi) where PAFi is PAF of individual risk factors.

The PAF for ambient air pollution and the PAF for household air pollution were assessed separately, based on the Comparative Risk Assessment (Ezzati et al, 2002) and expert groups for the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2010 study (Lim et al, 2012; Smith et al, 2014).

For exposure to ambient air pollution, annual mean estimates of particulate matter of a diameter of less than 2.5 um (PM25) were modelled as described in (WHO 2016, forthcoming), or for Indicator 11.6.2.

For exposure to household air pollution, the proportion of population with primary reliance on polluting fuels use for cooking was modelled (see Indicator 7.1.2 [polluting fuels use=1-clean fuels use]). Details on the model are published in (Bonjour et al, 2013).

The integrated exposure-response functions (IER) developed for the GBD 2010 (Burnett et al, 2014) and further updated for the GBD 2013 study (Forouzanfar et al, 2015) were used. The percentage of the population exposed to a specific risk factor (here ambient air pollution, i.e. PM2.5) was provided by country and by increment of 1 ug/m3; relative risks were calculated for each PM2.5 increment, based on the IER. The counterfactual concentration was selected to be between 5.6 and 8.8 ug/m3, as described elsewhere (Ezzati et al, 2002; Lim et al, 2012). The country population attributable fraction for ALRI, COPD, IHD, stroke and lung cancer were calculated using the following formula :

PAF=SUM(Pi(RR-1)/(SUM(RR-1)+1)

where i is the level of PM2.5 in ug/m3, and Pi is the percentage of the population exposed to that level of air pollution, and RR is the relative risk.

The calculations for household air pollution are similar, and are explained in detailed elsewhere (WHO 2014a).

An approximation of the combined effects of risk factors is possible if independence and little correlation between risk factors with impacts on the same diseases can be assumed (Ezzati et al, 2003). In the case of air pollution, however, there are some limitations to estimate the joint effects: limited knowledge on the distribution of the population exposed to both household and ambient air pollution, correlation of exposures at individual level as household air pollution is a contributor to ambient air pollution, and non- linear interactions (Lim et al, 2012; Smith et al, 2014). In several regions, however, household air pollution remains mainly a rural issue, while ambient air pollution is predominantly an urban problem. Also, in some continents, many countries are relatively unaffected by household air pollution, while ambient air pollution is a major concern. If assuming independence and little correlation, a rough estimate of the total impact can be calculated, which is less than the sum of the impact of the two risk factors.

TARGET 3.b Support the research and development of vaccines and medicines for the communicable and non‑communicable diseases that primarily affect developing countries, provide access to affordable essential medicines and vaccines, in accordance with the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health, which affirms the right of developing countries to use to the full the provisions in the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights regarding flexibilities to protect public health, and, in particular, provide access to medicines for all

Proportion of the target population covered by all vaccines included in their national programme.

This indicator aims to measure access to vaccines, including the newly available or underutilized vaccines, at the national level. In the past decades all countries added numerous new and underutilised vaccines in their national immunization schedule and there are several vaccines under final stage of development to be introduced by 2030. For monitoring diseases control and impact of vaccines it is important to measure coverage from each vaccine in national immunization schedule and the system is already in place for all national programmes, however direct measurement for proportion of population covered with all vaccines in the programme is only feasible if the country has a well-functioning national nominal immunization registry, usually an electronic one that will allow this coverage to be easily estimated. While countries will develop and strengthen immunization registries it is a need for an alternative measurement.

Coverage of DTP containing vaccine (3rd dose): Percentage of surviving infants who received the 3 doses of diphtheria and tetanus toxoid with pertussis containing vaccine in a given year.

Coverage of Measles containing vaccine (2nd dose): Percentage of children who received two dose of measles containing vaccine according to nationally recommended schedule through routine immunization services in a given year.

Coverage of Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (last dose in the schedule): Percentage of surviving infants who received the nationally recommended doses of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in a given year.

Coverage of HPV vaccine (last dose in the schedule): Percentage of 15 years old girls received the recommended doses of HPV vaccine. Currently performance of the programme in the previous calendar year based on target age group is used.

In accordance with its mandate to provide guidance to Member States on health policy matters, WHO provides global vaccine and immunization recommendations for diseases that have an international public health impact. National programmes adapt the recommendations and develop national immunization schedules, based on local disease epidemiology and national health priorities. National immunization schedules and number of recommended vaccines vary between countries, with only DTP polio and measles containing vaccines being used in all countries.

The target population for given vaccine is defined based on recommended age for administration. The primary vaccination series of most vaccines are administered in the first two years of life.

Coverage of DTP containing vaccine measure the overall system strength to deliver infant vaccination. Coverage of Measles containing vaccine ability to deliver vaccines beyond first year of life through routine immunization services. Coverage of Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine: adaptation of new vaccines for children Coverage of HPV vaccine: life cycle vaccination

WHO and UNICEF jointly developed a methodology to estimate national immunization coverage form selected vaccines in 2000. The methodology has been refined and reviewed by expert committees over time. The methodology was published and reference is available under the reference section. Estimates time series for WHO recommended vaccines produced and published annually since 2001.

The methodology uses data reported by national authorities from countries administrative systems as well as data from immunization or multi indicator household surveys.

The rational to select a set of vaccines reflects the ability of immunization programmes to deliver vaccines over the life cycle and to adapt new vaccines. Coverage for other WHO recommended vaccines are also available and can be provided.

Given that HPV vaccine is relatively new and vaccination schedule varies from countries to country coverage estimate will be made for girls vaccinated by ag 15 and at the moment data is limited to very few countries therefore reporting will start later.

To ensure healthy lives and promote the well-being of all children, UNICEF has four key asks that encourage all governments to:

- Strengthen primary healthcare systems to reach every child

- Focus on maternal, newborn and child survival

- Prioritize child and adolescent health and well-being, including mental health

- Support responses to reduce the impact on children and families of natural disasters, complex emergencies and demographic shifts

Learn more about UNICEF’s key asks for implementing Goal 3

See more Sustainable Development Goals

ZERO HUNGER

GOOD HEALTH AND WELL-BEING

QUALITY EDUCATION

GENDER EQUALITY

CLEAN WATER AND SANITATION

AFFORDABLE AND CLEAN ENERGY

DECENT WORK AND ECONOMIC GROWTH

REDUCED INEQUALITIES

CLIMATE ACTION

PEACE, JUSTICE AND STRONG INSTITUTIONS

PARTNERSHIPS FOR THE GOALS

Search the site

Links to social media channels

Healthy Lives and Well-being for Everyone: Why SDG 3 matters and how we can achieve it

Creating a sustainable world—and reaching economic, environmental and social goals—depends on having a thriving and healthy human population. We explore how Sustainable Development Goal 3 plans to achieve that.

Creating a sustainable world—and reaching economic, environmental and social goals—depends on having a thriving and healthy human population.

However, even the most cursory glance at figures pertaining to human health reveals a world where grave inequalities result in massive disparities when it comes to access to basic health care, and where easily treatable diseases still claim far too many lives in many corners of the globe.

Let’s start at birth. In 2015, there were approximately 303,000 maternal deaths worldwide, most from preventable causes. Maternal health conditions were also the leading cause of death among girls aged 15-19 in that year.

Infant mortality rates—along with many other health-related issues—can also expose inequalities within nations. In Canada, for example, while the average mortality rate is around 5 deaths per 1,000 live births, it reaches as high as 16 deaths per 1,000 live births in Nunavut—a region where 85 per cent of the population is Indigenous.

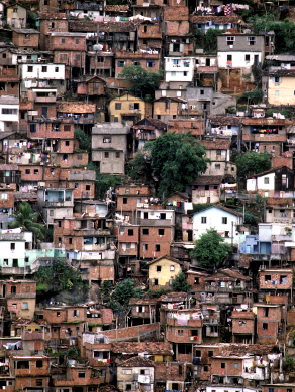

Around the world, more than 6 million children still die before their fifth birthday each year, with four out of five of those deaths occurring in sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia. Rates of poverty and the level of the mother’s education are key factors that affect the likelihood of a child making it past the age of five.

When it comes to communicable diseases, at the end of 2013, there were an estimated 35 million people living with HIV worldwide. In fact, 240,000 children were newly infected with the disease that year.

While the rates of malaria are falling globally, the recent resurgence of ailments such as measles and the Zika virus reminds us that there are always potential health crises around the corner for which we may not be equipped—with the Global South often most at risk.

A Global Approach to Worldwide Problems

When world leaders adopted the Sustainable Development Goals, they signed on to a goal (SDG 3) that aims to "ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages."

The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which provided a global framework for development from 2000-2015, and dedicated a hefty 3 out of 10 goals to global health issues (child mortality; maternal health; HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases).

The targets under SDG 3 have an even greater scope than those three MDGs combined. Furthermore, given the integrated nature of the sustainable development approach, many of the other SDGs, such as Goal 1 (“end poverty”), Goal 2 (“end hunger”) and Goal 6 (“ensure access to water”), are strongly tied to—and have an impact on—human health issues.

The recent resurgence of ailments such as measles and the Zika virus reminds us that there are always potential health crises around the corner for which we may not be equipped—with the Global South often most at risk.

Many of the SDG 3 targets are dedicated to tackling pressing issues surrounding maternal health and child mortality rates, which continue to affect much of the Global South in particular. The ambition of those targets reflects the urgency of the work at hand, and the desire of the international community to continue their work on the unfinished business in the MDGs. By 2030, Target 3.2 aims to “end preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5 years of age,” and Target 3.1 is to “reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100,000 live births.”

Other targets reflect the universal nature of the SDGs. They touch on everything from universal health coverage and tobacco control to reducing the number of deaths due to road traffic accidents and substance abuse—issues that are widespread in countries at all stages of development.

Both developed and developing countries have work to do to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all of their citizens, including addressing policies on universal access to health coverage and populations’ relationships with alcohol and narcotics.

Towards a Healthier Future

The global community has already made significant progress in key areas of human health. Despite the still-high figures of maternal mortality, the United Nations reports it has actually fallen by almost 50 percent since 1990. In Northern Africa and Southern and Eastern Asia, maternal mortality has also been reduced by around two-thirds.

17,000 fewer children die each day than in 1990—some of which can be attributed to increased access to vaccinations. For example, since 2000, the United Nations reports that measles vaccines have prevented almost 15.6 million deaths globally.

When it comes to treating HIV, at the end of 2014, 13.6 million had access to antiretroviral therapy, and new HIV infections in 2013 were estimated at 2.1 million—38 per cent lower than in 2001.

These achievements point to the value of international goals—the MDGs—in focusing global efforts on shared objectives. The SDGs continue, and widen the scope of actors and efforts, in order to ensure that no one is left behind due to lack of access to health care and healthy lifestyle options.

Insight details

You might also be interested in, rethinking investment treaties.

The reports maps out how the treaty system can be redesigned from the bottom up to accelerate—rather than obstruct—genuine sustainable development and international cooperation.

May 15, 2024

World Trade Organization Talks on Subsidies that Contribute to Overcapacity and Overfishing: What's on the table?

World governments are currently negotiating new global disciplines to curb harmful fisheries subsidies. What new rules are being proposed?

May 14, 2024

ASGM Tailings Management and Reprocessing Governance

This report outlines technical aspects, governance frameworks, and policy recommendations for artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) tailings management and reprocessing.

May 6, 2024

Progressing National SDGs Implementation

An independent assessment of the voluntary national review reports submitted to the United Nations High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development in 2023.

April 2, 2024

Sustainable Development Goal 3

Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.

Sustainable Development Goal 3 is to “ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages”, according to the United Nations .

The visualizations and data below present the global perspective on where the world stands today and how it has changed over time.

The UN has defined 13 targets and 28 indicators for SDG 3. Targets specify the goals and indicators represent the metrics by which the world aims to track whether these targets are achieved. Below we quote the original text of all targets and show the data on the agreed indicators.

Target 3.1 Reduce maternal mortality

Sdg indicator 3.1.1 maternal mortality ratio.

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 3.1.1 is the “maternal mortality ratio” in the UN SDG framework .

The maternal mortality ratio refers to the number of women who die from pregnancy-related causes while pregnant or within 42 days of pregnancy termination per 100,000 live births.

Data for this indicator is shown in the interactive visualization.

Target: By 2030 “reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100,000 live births” per year.

More research: The Our World in Data topic page on Maternal Mortality gives a long-run perspective over the last centuries and presents research on the causes and consequences of the deaths of mothers.

Additional charts

- Number of maternal deaths by region

- Number of maternal deaths by country

SDG Indicator 3.1.2 Skilled birth attendance

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 3.1.2 is the “proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel” in the UN SDG framework .

This indicator is measured as the ratio of the births attended by skilled health personnel (generally doctors, nurses, or midwives) who are trained in providing quality obstetric care, to the number of live births in the same period.

More research: Research, discussed in the Our World in Data topic page on Maternal Mortality , shows that skilled staff can reduce maternal mortality.

Target 3.2 End all preventable deaths under 5 years of age

Sdg indicator 3.2.1 under-5 mortality rate.

Definition: Indicator 3.2.1 is the “under-5 mortality rate” in the UN SDG framework .

The under-5 mortality rate measures the probability per 1,000 that a newborn baby will die before reaching age five, if subject to age-specific mortality rates of the specified year.

Target: By 2030, “end preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5 years of age, with all countries aiming to reduce neonatal mortality to at least as low as 12 per 1,000 live births and under-5 mortality to at least as low as 25 per 1,000 live births.”

More research: Child mortality is covered more broadly, and with a longer-term perspective in the Our World in Data topic page on Child Mortality .

- Number of under-five deaths

- Number of under-five deaths by region

- Child mortality rate by sex

SDG Indicator 3.2.2 Neonatal mortality rate

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 3.2.2 is the “neonatal mortality rate” in the UN SDG framework .

The neonatal mortality rate is defined as the probability per 1,000 that a child born in a given year will die during the first 28 days of life, if subject to the age-specific mortality rates of that period.

Data on this indicator is shown in the interactive visualization.

More research: The Our World in Data topic page on Child Mortality includes a section on neonatal mortality.

- Number of neonatal deaths

- Number of neonate deaths by region

Target 3.3 Fight communicable diseases

Sdg indicator 3.3.1 hiv incidence.

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 3.3.1 is the “number of new HIV infections per 1,000 uninfected population, by sex, age and key populations” in the UN SDG framework .

Data for this indicator is shown in the interactive visualization, by age group in the first chart and for the 15-49 age group in the second chart. You can change the country shown in the first chart by clicking the “Change country” button in the upper left hand corner.

Target: The target for 2030 is to “end the epidemic of AIDS” across all countries. 1

The targeted level of reduction is defined by UNAIDS as a 90% reduction in new HIV infections over 2010 levels. For all age groups combined, this would imply a target of around .03 per 1,000, or 3 new infections for every 100,000 uninfected people.

More research: HIV is covered in detail by the Our World in Data topic page on HIV/AIDS .

- Share of population infected with HIV

- HIV/AIDS death rates

- Number of HIV/AIDS deaths

SDG Indicator 3.3.2 Tuberculosis incidence

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 3.3.2 is “tuberculosis incidence per 100,000 population” in the UN SDG framework .

Tuberculosis incidence is the number of new and relapse cases of tuberculosis (TB) per 100,000 people, including all forms of TB.

Target: The 2030 target is to “end the epidemic of tuberculosis” in all countries. 1

The World Health Organization's End TB Strategy defines this targeted level of reduction as a decrease in incidence of 80% over 2015 levels. This would imply a target of around 28 cases per 100,000 population globally.

- Tuberculosis death rates

- Number of tuberculosis deaths

SDG Indicator 3.3.3 Malaria incidence

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 3.3.3 is “malaria incidence per 1,000 population” in the UN SDG framework .

Malaria incidence is the number of new cases of malaria in one year per 1,000 people at risk.

Target: By 2030 “end the epidemic of malaria” in all countries. 1

To achieve this target, the WHO Global Technical Strategy has set a target of reducing incidence by 90% by 2030 from 2015 levels. This would imply a target of 6 or fewer cases of malaria per 1,000 people globally in 2030.

More research: More information on global and national trends in malaria prevalence, deaths and interventions can be found at the Our World in Data topic page on Malaria .

- Malaria death rates

- Number of malaria deaths

SDG Indicator 3.3.4 Hepatitis B incidence

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 3.3.4 is “Hepatitis B incidence per 100,000 population” in the UN SDG framework .

Hepatitis B incidence is the number of new cases of hepatitis B in one year per 100,000 people in a given population. This is measured indirectly as the share of children under 5 years of age with an active Hepatitis B infection, as measured by an Hepatitis B surface antigen test.

Target: By 2030 “combat hepatitis” in all countries with a focus on hepatitis B. 1 The targeted level of reduction, however, is not defined.

- Hepatitis death rates

SDG Indicator 3.3.5 Neglected tropical diseases

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 3.3.5 is the “number of people requiring interventions against neglected tropical diseases” in the UN SDG framework .

This is defined as the number of people who require interventions (treatment and care) for any of the 20 neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) identified by the WHO NTD Roadmap and World Health Assembly resolutions. Treatment and care is broadly defined to allow for preventive, curative, surgical or rehabilitative treatment and care.

Target: By 2030 “end the epidemic of neglected tropical diseases (NTDs)” in all countries. 1

The associated WHO target is a 90% reduction in the number of people requiring interventions against NTDs from 2010 baseline levels. This implies a target of 219 million people needing interventions against NTDs in 2030.

- Number of people requiring interventions for NTDs by region

Target 3.4 Reduce mortality from non-communicable diseases and promote mental health

Sdg indicator 3.4.1 mortality rate from non-communicable diseases.

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 3.4.1 is the “mortality rate attributed to cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes or chronic respiratory disease” in the UN SDG framework .

This is defined as the percent of 30-year-old-people who would die before their 70th birthday from cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, or chronic respiratory disease, assuming that they would experience current mortality rates at every age and would not die from any other cause of death (e.g. injuries or HIV/AIDS).

Target: By 2030 “reduce by one third premature mortality from non-communicable diseases through prevention and treatment” in all countries. 2

More research: Further data and research on non-communicable diseases can be found at the Our World in Data topic pages on Causes of Death , Burden of Disease , and Cancer .

- Cancer death rates

- Cardiovascular disease (CVD) death rates

- Stroke death rates

SDG Indicator 3.4.2 Suicide rate

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 3.4.2 is the “suicide mortality rate” in the UN SDG framework .

The suicide mortality rate is the number of deaths from suicide measured per 100,000 people in a given population.

Target: By 2030 “promote mental health and wellbeing”. 2 There is no defined target level of reduction for this indicator.

More research: Further data and research on suicide, mental health and wellbeing can be found at the Our World in Data topic pages on Suicide , Mental Health and Happiness and Life Satisfaction .

- Number of suicide deaths

- Share of population with depression

Target 3.5 Prevent and treat substance abuse

Sdg indicator 3.5.1 coverage of treatment interventions for substance use disorders.

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 3.5.1 is the “coverage of treatment interventions (pharmacological, psychosocial and rehabilitation and aftercare services) for substance use disorders” in the UN SDG framework .

This is the share of people with substance use disorders in a given year who receive treatment in the form of pharmacological, psychosocial, rehabilitation or aftercare services. Data coverage in household surveys of substance use disorders is limited in many countries, and efforts are currently in progress to better estimate this indicator.

Data for this indicator is shown in the interactive visualizations. The first chart shows the share of the population with an alcohol use disorder in each country, and the second chart shows coverage of treatment interventions for certain types of substance use disorder for the countries where this data is available.

Target: By 2030 “strengthen the prevention and treatment of substance abuse, including narcotic drug abuse and harmful use of alcohol” across all countries. However, there is no defined target level for this indicator.

More research: The Our World in Data topic page on Substance Use provides data on substance use disorder prevalence and as well as more limited data coverage of treatment interventions.

SDG Indicator 3.5.2 Alcohol consumption per capita

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 3.5.2 is the “harmful use of alcohol, defined according to the national context as alcohol per capita consumption (aged 15 years and older) within a calendar year in litres of pure alcohol” in the UN SDG framework .

More research: Further data and research on alcohol consumption and alcohol use disorders can be found at the Our World in Data topic page on Alcohol Consumption .

- Share of population with alcohol use disorders

- Share of population with drug use disorders

- Prevalence of substance use disorders by sex

Target 3.6 Reduce road injuries and deaths

Sdg indicator 3.6.1 halve the number of road traffic deaths.

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 3.6.1 is the “death rate due to road traffic injuries” in the UN SDG framework .

Road traffic deaths include vehicle drivers, passengers, motorcyclists, cyclists and pedestrians.

Data for this indicator is shown in the first chart in the series of interactive visualizations. The second chart shows the absolute number of road traffic deaths for additional context.

Target: By 2020 “halve the number of global deaths and injuries from road traffic accidents.”

While most SDG targets are set for 2030, this was set to be achieved for 2020.

Note that the SDG Indicator is the rate of road deaths while the target is set for the absolute number of road deaths. Because of this, the interactive visualization shows, in the first chart, the road traffic death rate, and in the second chart, the number of road traffic deaths.

- Road traffic deaths by user

Target 3.7 Universal access to sexual and reproductive care, family planning and education

Sdg indicator 3.7.1 family planning needs.

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 3.7.1 is the “proportion of women of reproductive age (aged 15–49 years) who have their need for family planning satisfied with modern methods” in the UN SDG framework .

This indicator incorporates two components, the prevalence of modern methods of contraception, and the share of women of reproductive age who want to stop or delay childbearing but are not using any method of contraception.

It is measured as the percent of women of reproductive age (15-49 years) who are currently using at least one modern contraceptive method, out of the total population of women who have demand for contraceptive methods (defined as those using contraception of any form or who have unmet need for contraception).

Target: By 2030 “ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive healthcare services, including for family planning, information and education.” 3

More research: Further data and research can be found at the Our World in Data topic page on Fertility Rate .

- Unmet need for contraception

- Contraception prevalence, any methods

SDG Indicator 3.7.2 Adolescent birth rate

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 3.7.2 is the “adolescent birth rate (aged 10–14 years; aged 15–19 years) per 1,000 women in that age group” in the UN SDG framework .

Data for this indicator is shown in the interactive visualizations, which show, in the first chart, adolescent birth rates per 1,000 women aged 10-14 years old, and in the second chart, women aged 15-19 years old.

Target: By 2030 “ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive healthcare services, including for family planning.” 3

Target 3.8 Achieve universal health coverage

Sdg indicator 3.8.1 coverage of essential health services.

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 3.8.1 is “coverage of essential health services” in the UN SDG framework .

Coverage of essential health services is defined as the average coverage of essential services based on tracer interventions that include reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health, infectious diseases, non-communicable diseases and service capacity and access, among the general and the most disadvantaged population.

The Universal Health Coverage (UHC) Service Coverage Index is used to track progress on this indicator. The index is on a scale from 0 to 100, where 100 is the optimal value, and calculated from the geometric mean of 14 indicators measuring the coverage of essential services including reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health, infectious diseases, non-communicable diseases and service capacity and access.

Target: By 2030 “achieve universal health coverage including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all.”

More research: Further data and research can be found at the Our World in Data topic page on Financing Healthcare .

SDG Indicator 3.8.2 Household expenditures on health

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 3.8.2 is the “proportion of population with large household expenditures on health as a share of total household expenditure or income” in the UN SDG framework .

Two thresholds are used for defining large household expenditures: greater than 10% or 25% of total household expenditure or income.

The interactive visualizations show data for the 25 and 10 percent thresholds.

Target: By 2030 “achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all.”

- Out-of-pocket expenditure on healthcare

- Risk of catastrophic expenditure for surgical care

- Risk of impoverishing expenditure for surgical care

Target 3.9 Reduce illnesses and deaths from hazardous chemicals and pollution

Sdg indicator 3.9.1 mortality rate from air pollution.

Definition of the SDG indicator: Indicator 3.9.1 is the “mortality rate attributed to household and ambient air pollution” in the UN SDG framework .

This is measured as the number of deaths attributed to indoor and outdoor air pollution per 100,000 people, accounting for differences in the age structure of different populations.

Data for this indicator is shown in the series of interactive visualizations, first for household and ambient air pollution combined, then for each separately, and then with a comparison of the two types of pollution in the final chart.