- Search This Site All UCSD Sites Faculty/Staff Search Term

- Contact & Directions

- Climate Statement

- Cognitive Behavioral Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Adjunct Faculty

- Non-Senate Instructors

- Researchers

- Psychology Grads

- Affiliated Grads

- New and Prospective Students

- Honors Program

- Experiential Learning

- Programs & Events

- Psi Chi / Psychology Club

- Prospective PhD Students

- Current PhD Students

- Area Brown Bags

- Colloquium Series

- Anderson Distinguished Lecture Series

- Speaker Videos

- Undergraduate Program

- Academic and Writing Resources

Writing Research Papers

- Writing a Literature Review

When writing a research paper on a specific topic, you will often need to include an overview of any prior research that has been conducted on that topic. For example, if your research paper is describing an experiment on fear conditioning, then you will probably need to provide an overview of prior research on fear conditioning. That overview is typically known as a literature review.

Please note that a full-length literature review article may be suitable for fulfilling the requirements for the Psychology B.S. Degree Research Paper . For further details, please check with your faculty advisor.

Different Types of Literature Reviews

Literature reviews come in many forms. They can be part of a research paper, for example as part of the Introduction section. They can be one chapter of a doctoral dissertation. Literature reviews can also “stand alone” as separate articles by themselves. For instance, some journals such as Annual Review of Psychology , Psychological Bulletin , and others typically publish full-length review articles. Similarly, in courses at UCSD, you may be asked to write a research paper that is itself a literature review (such as, with an instructor’s permission, in fulfillment of the B.S. Degree Research Paper requirement). Alternatively, you may be expected to include a literature review as part of a larger research paper (such as part of an Honors Thesis).

Literature reviews can be written using a variety of different styles. These may differ in the way prior research is reviewed as well as the way in which the literature review is organized. Examples of stylistic variations in literature reviews include:

- Summarization of prior work vs. critical evaluation. In some cases, prior research is simply described and summarized; in other cases, the writer compares, contrasts, and may even critique prior research (for example, discusses their strengths and weaknesses).

- Chronological vs. categorical and other types of organization. In some cases, the literature review begins with the oldest research and advances until it concludes with the latest research. In other cases, research is discussed by category (such as in groupings of closely related studies) without regard for chronological order. In yet other cases, research is discussed in terms of opposing views (such as when different research studies or researchers disagree with one another).

Overall, all literature reviews, whether they are written as a part of a larger work or as separate articles unto themselves, have a common feature: they do not present new research; rather, they provide an overview of prior research on a specific topic .

How to Write a Literature Review

When writing a literature review, it can be helpful to rely on the following steps. Please note that these procedures are not necessarily only for writing a literature review that becomes part of a larger article; they can also be used for writing a full-length article that is itself a literature review (although such reviews are typically more detailed and exhaustive; for more information please refer to the Further Resources section of this page).

Steps for Writing a Literature Review

1. Identify and define the topic that you will be reviewing.

The topic, which is commonly a research question (or problem) of some kind, needs to be identified and defined as clearly as possible. You need to have an idea of what you will be reviewing in order to effectively search for references and to write a coherent summary of the research on it. At this stage it can be helpful to write down a description of the research question, area, or topic that you will be reviewing, as well as to identify any keywords that you will be using to search for relevant research.

2. Conduct a literature search.

Use a range of keywords to search databases such as PsycINFO and any others that may contain relevant articles. You should focus on peer-reviewed, scholarly articles. Published books may also be helpful, but keep in mind that peer-reviewed articles are widely considered to be the “gold standard” of scientific research. Read through titles and abstracts, select and obtain articles (that is, download, copy, or print them out), and save your searches as needed. For more information about this step, please see the Using Databases and Finding Scholarly References section of this website.

3. Read through the research that you have found and take notes.

Absorb as much information as you can. Read through the articles and books that you have found, and as you do, take notes. The notes should include anything that will be helpful in advancing your own thinking about the topic and in helping you write the literature review (such as key points, ideas, or even page numbers that index key information). Some references may turn out to be more helpful than others; you may notice patterns or striking contrasts between different sources ; and some sources may refer to yet other sources of potential interest. This is often the most time-consuming part of the review process. However, it is also where you get to learn about the topic in great detail. For more details about taking notes, please see the “Reading Sources and Taking Notes” section of the Finding Scholarly References page of this website.

4. Organize your notes and thoughts; create an outline.

At this stage, you are close to writing the review itself. However, it is often helpful to first reflect on all the reading that you have done. What patterns stand out? Do the different sources converge on a consensus? Or not? What unresolved questions still remain? You should look over your notes (it may also be helpful to reorganize them), and as you do, to think about how you will present this research in your literature review. Are you going to summarize or critically evaluate? Are you going to use a chronological or other type of organizational structure? It can also be helpful to create an outline of how your literature review will be structured.

5. Write the literature review itself and edit and revise as needed.

The final stage involves writing. When writing, keep in mind that literature reviews are generally characterized by a summary style in which prior research is described sufficiently to explain critical findings but does not include a high level of detail (if readers want to learn about all the specific details of a study, then they can look up the references that you cite and read the original articles themselves). However, the degree of emphasis that is given to individual studies may vary (more or less detail may be warranted depending on how critical or unique a given study was). After you have written a first draft, you should read it carefully and then edit and revise as needed. You may need to repeat this process more than once. It may be helpful to have another person read through your draft(s) and provide feedback.

6. Incorporate the literature review into your research paper draft.

After the literature review is complete, you should incorporate it into your research paper (if you are writing the review as one component of a larger paper). Depending on the stage at which your paper is at, this may involve merging your literature review into a partially complete Introduction section, writing the rest of the paper around the literature review, or other processes.

Further Tips for Writing a Literature Review

Full-length literature reviews

- Many full-length literature review articles use a three-part structure: Introduction (where the topic is identified and any trends or major problems in the literature are introduced), Body (where the studies that comprise the literature on that topic are discussed), and Discussion or Conclusion (where major patterns and points are discussed and the general state of what is known about the topic is summarized)

Literature reviews as part of a larger paper

- An “express method” of writing a literature review for a research paper is as follows: first, write a one paragraph description of each article that you read. Second, choose how you will order all the paragraphs and combine them in one document. Third, add transitions between the paragraphs, as well as an introductory and concluding paragraph. 1

- A literature review that is part of a larger research paper typically does not have to be exhaustive. Rather, it should contain most or all of the significant studies about a research topic but not tangential or loosely related ones. 2 Generally, literature reviews should be sufficient for the reader to understand the major issues and key findings about a research topic. You may however need to confer with your instructor or editor to determine how comprehensive you need to be.

Benefits of Literature Reviews

By summarizing prior research on a topic, literature reviews have multiple benefits. These include:

- Literature reviews help readers understand what is known about a topic without having to find and read through multiple sources.

- Literature reviews help “set the stage” for later reading about new research on a given topic (such as if they are placed in the Introduction of a larger research paper). In other words, they provide helpful background and context.

- Literature reviews can also help the writer learn about a given topic while in the process of preparing the review itself. In the act of research and writing the literature review, the writer gains expertise on the topic .

Downloadable Resources

- How to Write APA Style Research Papers (a comprehensive guide) [ PDF ]

- Tips for Writing APA Style Research Papers (a brief summary) [ PDF ]

- Example APA Style Research Paper (for B.S. Degree – literature review) [ PDF ]

Further Resources

How-To Videos

- Writing Research Paper Videos

- UCSD Library Psychology Research Guide: Literature Reviews

External Resources

- Developing and Writing a Literature Review from N Carolina A&T State University

- Example of a Short Literature Review from York College CUNY

- How to Write a Review of Literature from UW-Madison

- Writing a Literature Review from UC Santa Cruz

- Pautasso, M. (2013). Ten Simple Rules for Writing a Literature Review. PLoS Computational Biology, 9 (7), e1003149. doi : 1371/journal.pcbi.1003149

1 Ashton, W. Writing a short literature review . [PDF]

2 carver, l. (2014). writing the research paper [workshop]. , prepared by s. c. pan for ucsd psychology.

Back to top

- Research Paper Structure

- Formatting Research Papers

- Using Databases and Finding References

- What Types of References Are Appropriate?

- Evaluating References and Taking Notes

- Citing References

- Writing Process and Revising

- Improving Scientific Writing

- Academic Integrity and Avoiding Plagiarism

- Writing Research Papers Videos

In order to help minimize spread of the coronavirus and protect our campus community, Cowles Library is adjusting our services, hours, and building access. Read more...

- Research, Study, Learning

- Archives & Special Collections

- Cowles Library

- Find Journal Articles

- Find Articles in Related Disciplines

- Find Streaming Video

- Conducting a Literature Review

- Organizations, Associations, Societies

- For Faculty

What is a Literature Review?

Description.

A literature review, also called a review article or review of literature, surveys the existing research on a topic. The term "literature" in this context refers to published research or scholarship in a particular discipline, rather than "fiction" (like American Literature) or an individual work of literature. In general, literature reviews are most common in the sciences and social sciences.

Literature reviews may be written as standalone works, or as part of a scholarly article or research paper. In either case, the purpose of the review is to summarize and synthesize the key scholarly work that has already been done on the topic at hand. The literature review may also include some analysis and interpretation. A literature review is not a summary of every piece of scholarly research on a topic.

Why are literature reviews useful?

Literature reviews can be very helpful for newer researchers or those unfamiliar with a field by synthesizing the existing research on a given topic, providing the reader with connections and relationships among previous scholarship. Reviews can also be useful to veteran researchers by identifying potentials gaps in the research or steering future research questions toward unexplored areas. If a literature review is part of a scholarly article, it should include an explanation of how the current article adds to the conversation. (From: https://researchguides.drake.edu/englit/criticism)

How is a literature review different from a research article?

Research articles: "are empirical articles that describe one or several related studies on a specific, quantitative, testable research question....they are typically organized into four text sections: Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion." Source: https://psych.uw.edu/storage/writing_center/litrev.pdf)

Steps for Writing a Literature Review

1. Identify and define the topic that you will be reviewing.

The topic, which is commonly a research question (or problem) of some kind, needs to be identified and defined as clearly as possible. You need to have an idea of what you will be reviewing in order to effectively search for references and to write a coherent summary of the research on it. At this stage it can be helpful to write down a description of the research question, area, or topic that you will be reviewing, as well as to identify any keywords that you will be using to search for relevant research.

2. Conduct a Literature Search

Use a range of keywords to search databases such as PsycINFO and any others that may contain relevant articles. You should focus on peer-reviewed, scholarly articles . In SuperSearch and most databases, you may find it helpful to select the Advanced Search mode and include "literature review" or "review of the literature" in addition to your other search terms. Published books may also be helpful, but keep in mind that peer-reviewed articles are widely considered to be the “gold standard” of scientific research. Read through titles and abstracts, select and obtain articles (that is, download, copy, or print them out), and save your searches as needed. Most of the databases you will need are linked to from the Cowles Library Psychology Research guide .

3. Read through the research that you have found and take notes.

Absorb as much information as you can. Read through the articles and books that you have found, and as you do, take notes. The notes should include anything that will be helpful in advancing your own thinking about the topic and in helping you write the literature review (such as key points, ideas, or even page numbers that index key information). Some references may turn out to be more helpful than others; you may notice patterns or striking contrasts between different sources; and some sources may refer to yet other sources of potential interest. This is often the most time-consuming part of the review process. However, it is also where you get to learn about the topic in great detail. You may want to use a Citation Manager to help you keep track of the citations you have found.

4. Organize your notes and thoughts; create an outline.

At this stage, you are close to writing the review itself. However, it is often helpful to first reflect on all the reading that you have done. What patterns stand out? Do the different sources converge on a consensus? Or not? What unresolved questions still remain? You should look over your notes (it may also be helpful to reorganize them), and as you do, to think about how you will present this research in your literature review. Are you going to summarize or critically evaluate? Are you going to use a chronological or other type of organizational structure? It can also be helpful to create an outline of how your literature review will be structured.

5. Write the literature review itself and edit and revise as needed.

The final stage involves writing. When writing, keep in mind that literature reviews are generally characterized by a summary style in which prior research is described sufficiently to explain critical findings but does not include a high level of detail (if readers want to learn about all the specific details of a study, then they can look up the references that you cite and read the original articles themselves). However, the degree of emphasis that is given to individual studies may vary (more or less detail may be warranted depending on how critical or unique a given study was). After you have written a first draft, you should read it carefully and then edit and revise as needed. You may need to repeat this process more than once. It may be helpful to have another person read through your draft(s) and provide feedback.

6. Incorporate the literature review into your research paper draft. (note: this step is only if you are using the literature review to write a research paper. Many times the literature review is an end unto itself).

After the literature review is complete, you should incorporate it into your research paper (if you are writing the review as one component of a larger paper). Depending on the stage at which your paper is at, this may involve merging your literature review into a partially complete Introduction section, writing the rest of the paper around the literature review, or other processes.

These steps were taken from: https://psychology.ucsd.edu/undergraduate-program/undergraduate-resources/academic-writing-resources/writing-research-papers/writing-lit-review.html#6.-Incorporate-the-literature-r

- << Previous: Find Streaming Video

- Next: Organizations, Associations, Societies >>

- Last Updated: Feb 29, 2024 4:09 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.drake.edu/psychology

- 2507 University Avenue

- Des Moines, IA 50311

- (515) 271-2111

Trouble finding something? Try searching , or check out the Get Help page.

University Library

- Research Guides

- Literature Reviews

- Finding Articles

- Finding Books and Media

- Research Methods, Tests, and Statistics

- Citations and APA Style

- Annotated Bibliographies

- Other Resources

- According to Science

- The Scientific Process

- Activity: Scholarly Party

What is a Literature Review?

The scholarly conversation.

A literature review provides an overview of previous research on a topic that critically evaluates, classifies, and compares what has already been published on a particular topic. It allows the author to synthesize and place into context the research and scholarly literature relevant to the topic. It helps map the different approaches to a given question and reveals patterns. It forms the foundation for the author’s subsequent research and justifies the significance of the new investigation.

A literature review can be a short introductory section of a research article or a report or policy paper that focuses on recent research. Or, in the case of dissertations, theses, and review articles, it can be an extensive review of all relevant research.

- The format is usually a bibliographic essay; sources are briefly cited within the body of the essay, with full bibliographic citations at the end.

- The introduction should define the topic and set the context for the literature review. It will include the author's perspective or point of view on the topic, how they have defined the scope of the topic (including what's not included), and how the review will be organized. It can point out overall trends, conflicts in methodology or conclusions, and gaps in the research.

- In the body of the review, the author should organize the research into major topics and subtopics. These groupings may be by subject, (e.g., globalization of clothing manufacturing), type of research (e.g., case studies), methodology (e.g., qualitative), genre, chronology, or other common characteristics. Within these groups, the author can then discuss the merits of each article and analyze and compare the importance of each article to similar ones.

- The conclusion will summarize the main findings, make clear how this review of the literature supports (or not) the research to follow, and may point the direction for further research.

- The list of references will include full citations for all of the items mentioned in the literature review.

Key Questions for a Literature Review

A literature review should try to answer questions such as

- Who are the key researchers on this topic?

- What has been the focus of the research efforts so far and what is the current status?

- How have certain studies built on prior studies? Where are the connections? Are there new interpretations of the research?

- Have there been any controversies or debate about the research? Is there consensus? Are there any contradictions?

- Which areas have been identified as needing further research? Have any pathways been suggested?

- How will your topic uniquely contribute to this body of knowledge?

- Which methodologies have researchers used and which appear to be the most productive?

- What sources of information or data were identified that might be useful to you?

- How does your particular topic fit into the larger context of what has already been done?

- How has the research that has already been done help frame your current investigation ?

Examples of Literature Reviews

Example of a literature review at the beginning of an article: Forbes, C. C., Blanchard, C. M., Mummery, W. K., & Courneya, K. S. (2015, March). Prevalence and correlates of strength exercise among breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors . Oncology Nursing Forum, 42(2), 118+. Retrieved from http://go.galegroup.com.sonoma.idm.oclc.org/ps/i.do?p=HRCA&sw=w&u=sonomacsu&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CA422059606&asid=27e45873fddc413ac1bebbc129f7649c Example of a comprehensive review of the literature: Wilson, J. L. (2016). An exploration of bullying behaviours in nursing: a review of the literature. British Journal Of Nursing , 25 (6), 303-306. For additional examples, see:

Galvan, J., Galvan, M., & ProQuest. (2017). Writing literature reviews: A guide for students of the social and behavioral sciences (Seventh ed.). [Electronic book]

Pan, M., & Lopez, M. (2008). Preparing literature reviews: Qualitative and quantitative approaches (3rd ed.). Glendale, CA: Pyrczak Pub. [ Q180.55.E9 P36 2008]

Useful Links

- Write a Literature Review (UCSC)

- Literature Reviews (Purdue)

- Literature Reviews: overview (UNC)

- Review of Literature (UW-Madison)

Evidence Matrix for Literature Reviews

The Evidence Matrix can help you organize your research before writing your lit review. Use it to identify patterns and commonalities in the articles you have found--similar methodologies ? common theoretical frameworks ? It helps you make sure that all your major concepts covered. It also helps you see how your research fits into the context of the overall topic.

- Evidence Matrix Special thanks to Dr. Cindy Stearns, SSU Sociology Dept, for permission to use this Matrix as an example.

- << Previous: Citations and APA Style

- Next: Annotated Bibliographies >>

- Last Updated: Jan 8, 2024 2:58 PM

- URL: https://libguides.sonoma.edu/psychology

Maureen and Mike Mansfield Library

View All Hours | My Library Accounts

Research and Find Materials

Technology and Spaces

Archives and Special Collections

Psychology Research Guide

- Literature Review

- Web Resources

- Library Services

Literature Review Overview

A literature review involves both the literature searching and the writing. The purpose of the literature search is to:

- reveal existing knowledge

- identify areas of consensus and debate

- identify gaps in knowledge

- identify approaches to research design and methodology

- identify other researchers with similar interests

- clarify your future directions for research

List above from Conducting A Literature Search , Information Research Methods and Systems, Penn State University Libraries

A literature review provides an evaluative review and documentation of what has been published by scholars and researchers on a given topic. In reviewing the published literature, the aim is to explain what ideas and knowledge have been gained and shared to date (i.e., hypotheses tested, scientific methods used, results and conclusions), the weakness and strengths of these previous works, and to identify remaining research questions: A literature review provides the context for your research, making clear why your topic deserves further investigation.

Before You Search

- Select and understand your research topic and question.

- Identify the major concepts in your topic and question.

- Brainstorm potential keywords/terms that correspond to those concepts.

- Identify alternative keywords/terms (narrower, broader, or related) to use if your first set of keywords do not work.

- Determine (Boolean*) relationships between terms.

- Begin your search.

- Review your search results.

- Revise & refine your search based on the initial findings.

*Boolean logic provides three ways search terms/phrases can be combined, using the following three operators: AND, OR, and NOT.

Search Process

The type of information you want to find and the practices of your discipline(s) drive the types of sources you seek and where you search.

For most research you will use multiple source types such as: annotated bibliographies; articles from journals, magazines, and newspapers; books; blogs; conference papers; data sets; dissertations; organization, company, or government reports; reference materials; systematic reviews; archival materials; curriculum materials; and more. It can be helpful to develop a comprehensive approach to review different sources and where you will search for each. Below is an example approach.

Utilize Current Awareness Services Identify and browse current issues of the most relevant journals for your topic; Setup email or RSS Alerts, e.g., Journal Table of Contents, Saved Searches

Consult Experts Identify and search for the publications of or contact educators, scholars, librarians, employees etc. at schools, organizations, and agencies

- Annual Reviews and Bibliographies e.g., Annual Review of Psychology

- Internet e.g., Discussion Groups, Listservs, Blogs, social networking sites

- Grant Databases e.g., Foundation Directory Online, Grants.gov

- Conference Proceedings e.g., International Psychological Applications Conference and Trends (InPACT), The European Conference on Psychology & the Behavioral Sciences via IAFOR Research Archive

- Newspaper Indexes e.g., Access World News, Ethnic NewsWatch, New York Times Historical

- Journal Indexes/Databases and EJournal Packages e.g., PsycArticles, ScienceDirect

- Citation Indexes e.g., PsycINFO, Psychiatry Online

- Specialized Data e.g., American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment survey data, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Data Archive

- Book Catalogs – e.g., local library catalog or discovery search, WorldCat

- Library Web Scale Discovery Service e.g., OneSearch

- Web Search Engines e.g., Google, Yahoo

- Digital Collections e.g., Archives & Special Collections Digital Collections, Archives of the History of American Psychology

- Associations/Community groups/Institutions/Organizations e.g., American Psychological Association

Remember there is no one portal for all information!

Database Searching Videos, Guides, and Examples

- Comprehensive guide to the database

- Sample Searches

- Searchable Fields

- Education topic guide

- Child Development topic guide

ProQuest (platform for ERIC, PsycINFO, and Dissertations & Theses Global databases, among other databases) search videos:

- Basic Search

- Advanced Search

- Search Results

- Performing Basic Searches

- Performing Advanced Searches

- Search Tips

If you are new to research , check out the Searching for Information tutorials and videos for foundational information.

Finding Empirical Studies

In ERIC : Check the box next to “143: Reports - Research” under "Document type" from the Advanced Search page

In PsycINFO : Check the box next to “Empirical Study” under "Methodology" from the Advanced Search page

In OneSearch : There is not a specific way to limit to empirical studies in OneSearch, you can limit your search results to peer-reviewed journals and or dissertations, and then identify studies by reading the source abstract to determine if you’ve found an empirical study or not.

Summarize Studies in a Meaningful Way

The Writing and Public Speaking Center at UM provides not only tutoring but many other resources for writers and presenters. Three with key tips for writing a literature review are:

- Literature Reviews Defined

- Tracking, Organizing, and Using Sources

- Organizing and Integrating Sources

If you are new to research , check out the Presenting Research and Data tutorials and videos for foundational information. You may also want to consult the Purdue OWL Academic Writing resources or APA Style Workshop content.

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Web Resources >>

- Last Updated: May 20, 2024 2:51 PM

- URL: https://libguides.lib.umt.edu/psychology

News alert: UC Berkeley has announced its next university librarian

Secondary menu

- Log in to your Library account

- Hours and Maps

- Connect from Off Campus

- UC Berkeley Home

Search form

Psychology 140: developmental psychology: the literature review.

- The Literature Review

- Off-Campus Access

- Finding Articles

- Citations & Bibliographic Software (Zotero)

http://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/psyc140

Quick links.

- Google Scholar This link opens in a new window Search across many disciplines and sources including articles, theses, books, abstracts and court opinions, from academic publishers, professional societies, online repositories, universities and other web sites. more... less... Lists journal articles, books, preprints, and technical reports in many subject areas (though more specialized article databases may cover any given field more completely). Can be used with "Get it at UC" to access the full text of many articles.

What is a Literature Review?

A literature review is a survey of research on a given topic. It allows you see what has already been written on a topic so that you can draw on that research in your own study. By seeing what has already been written on a topic you will also know how to distinguish your research and engage in an original area of inquiry.

Why do a Literature Review?

A literature review helps you explore the research that has come before you, to see how your research question has (or has not) already been addressed.

You will identify:

- core research in the field

- experts in the subject area

- methodology you may want to use (or avoid)

- gaps in knowledge -- or where your research would fit in

Elements of a Successful Literature Review

According to Byrne's What makes a successful literature review? you should follow these steps:

- Identify appropriate search terms.

- Search appropriate databases to identify articles on your topic.

- Identify key publications in your area.

- Search the web to identify relevant grey literature. (Grey literature is often found in the public sector and is not traditionally published like academic literature. It is often produced by research organizations.)

- Scan article abstracts and summaries before reading the piece in full.

- Read the relevant articles and take notes.

- Organize by theme.

- Write your review .

from Byrne, D. (2017). What makes a successful literature review?. Project Planner . 10.4135/9781526408518. (via SAGE Research Methods )

Research help

Email : Email your research questions to the Library.

Appointments : Schedule a 30-minute research meeting with a librarian.

Find a subject librarian : Find a library expert in your specific field of study.

Research guides on your topic : Learn more about resources for your topic or subject.

- Next: Off-Campus Access >>

- Last Updated: Feb 28, 2024 3:04 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/psyc140

- Macquarie University Library

- Subject and Research Guides

Psychological Sciences

- Literature Reviews

- Databases & Journals

- Books and Reference Sources

- Search, Select, Evaluate

- Referencing

- Research Tools

- Tests and Measurements

- Master of Professional Psychology: PSYP8910

- Psychology Honours

Getting started with your Literature Review

- Introduction

- What is a good literature review?

- Future proofing

A literature review is a comprehensive and critical review of literature that provides the theoretical foundation of your chosen topic.

A review will demonstrate that an exhaustive search for literature has been undertaken. It might be used for a thesis, a report, a research essay or a study.

A good literature review is a critical component of academic research, providing a comprehensive and systematic analysis of existing scholarly works on a specific topic. Here are the key elements that make up a good literature review:

Focus and clarity: A good literature review has a clear and well-defined research question or objective. It focuses on a specific topic and provides a coherent and structured analysis of the relevant literature.

I n-depth research: A comprehensive literature review involves an extensive search of relevant sources, including academic journals, books, and reputable online databases. It ensures that a wide range of perspectives and findings are considered.

Critical evaluatio n: A good literature review involves a critical assessment of the quality, credibility, and relevance of the selected sources. It evaluates the methodologies, strengths, weaknesses, and limitations of each study to determine their impact on the overall research.

Synthesis and analysis : A literature review should go beyond summarizing individual studies. It involves synthesizing and analyzing the findings, identifying patterns, themes, and gaps in the existing literature, and presenting a coherent narrative that connects different works.

Contribution to knowledg e: A good literature review not only summarizes existing research but also contributes to the knowledge base. It identifies gaps, inconsistencies, or unresolved debates in the field and suggests avenues for further research.

Clear and concise writing : A well-written literature review presents complex ideas in a clear, concise, and organized manner. It uses appropriate language, avoids jargon, and maintains a logical flow of information.

Proper citation and referencing: Accurate citation and referencing of the reviewed sources are crucial for maintaining academic integrity. Following the appropriate referencing style guidelines ensures consistency and allows readers to access the cited works.

In summary, a good literature review demonstrates a thorough understanding of the topic, critically engages with existing literature, and offers valuable insights for future research.

Where should you search?

The Library uses MultiSearch as an access point to our subscriptions and resources. Using MultiSearch is a good place to start.

You can also search directly in databases. Every discipline has specialist databases and there are also good multidisciplinary databases such as Scopus . Check the Databases page on this guide or ask your Faculty Librarian for advice.

You might also like to consider statistics, government publications or conference proceedings. This will depend on the question you're researching.

What should you read?

Not everything!

- Skim the title, the keywords, the abstract ... know when to pass on something and move on.

- Also know when to stop your literature review. When you start seeing the same material repeated in searches, or no new ideas or perspectives, maybe you have it covered.

Evaluating Literature

You will need to read critically when assessing material for inclusion in your literature review. Each piece of information you look at (whether a journal article, a book, a video, or something else) should be assessed.

- Is the material current?

- Does it have a bias (why was is published)?

- Is the author authoritative?

- Is the journal well regarded in the field (peer reviewed journals are the gold standard but other journals are worthy too).

- Does it provide enough coverage of the topic, or is it basic?

- Will books or journal articles be most useful for your interest area - or do you need to find other materials like government publications, or primary sources?

Analyse the Literature

Once you've read widely on your subject, stop to consider what new insights this knowledge has provided.

- Can you see any ideas emerging more strongly than others?

- Have you changed your position since starting your reading? Perhaps the evidence has made you reconsider your starting viewpoint - or it might have made you more committed to it. However, you should read with an open mind, and be prepared to change your thinking if the evidence points that way.

- Make note of a few points every time you read something. Key arguments or themes. Perhaps a note of ideas you'd like to explore more. You might want to attach this information in the same file we've mentioned in the 'future proofing' tab.

Keep a search diary

Set up a document or spreadsheet to record where you've searched, and also the search strategies you've used. Record the search terms and also the places which have served you well. For instance, is there a particular database which had good coverage?

You may need to repeat searches in the future and this information will help. It might also be requested by your supervisor.

Saving alerts

There are many options for setting up alerts which will help you keep track of new publications by a journal, or an author who is key in your research area, or even when other people cite the papers you have noted (maybe their work will be of interest to you).

These include:

- Table of contents (TOC)

- Citation alerts

- Topic or subject alerts

- Author alert

Developing a comprehensive search strategy

- Before you start

1. Consider the guidance in the "getting started" box above before starting your search.

2. Develop your research question or need.

3. Set up your search diary to record your progress and as a reference guide to come back to.

1. Identify the major concepts from your research question or topic.

Let's say that our topic is: How do alternative energy sources play a role in climate change?

The major concepts will be

- a lternative energy sources

- climate change

2. List synonyms or alternative terms for each concept and organise them in a table like the one below - using a column for each major concept. Use as many columns as you have major concepts.

Tools and tips to assist with this process:

- Run scoping searches for your topic in your favourite database or databases such as Google Scholar or Scopus to identify how the literature can express your concepts. Scan titles, subject headings (if any) and abstracts for words describing the same things as your major concepts.

- Text mining tools including PubMed Reminer especially if you are using a database with MeSH such as Medline or Cochrane. There are many others however.

- As you find something new, add it to the appropriate column on your list to incorporate later in your search.

Create your search strategy from the concepts, synonyms, phrases etc in your Concept Grid

Identify the best databases for your topic. Check the databases tab in the left menu on this Guide.

N.B.The syntax/search tools for your search may depend on the particular database you are searching in. Most databases have a Help screen to assist.

However, the majority of databases will use Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) and other commonly used search tools :

- Use "OR" to connect each of your synonyms (eg "climate change" OR "global warming")

- Use "AND" to connect each of your concepts.

- (Use "NOT" to exclude terms - but these should be used sparingly as they can knock out useful results.)

- Use the Truncation symbol * at the end of word roots which might have alternative endings eg: manag* will retrieve: manage; management; managing, managerial etc.

- Use quotes to keep together words of phrases (eg "climate change")

- Group your concepts algebraically using parentheses.

- Consider, is your term alternatively expressed as two words? (eg hydro electricity or hydroelectricity (you should include both!))

So with our question/topic: How do alternative energy sources play a role in climate change?

After identifying our major concepts and synonyms for each and employing some of the tools mentioned above, our constructed search strategy might look something like this:

("alternative energ*" OR "wind power" OR "Solar power" OR "Solar energy" OR Renewabl* OR geothermal OR hydroelectricity OR "hydro electricity") AND ("climate change" OR "global* warm*" or "greenhouse gas*" or "green house gas*")

3. Be prepared to revise, reassess and refine your search strategies after you have run your initial searches to ensure you get the best possible results. If you retrieve too many false results or "noise", try to analyse why. For example, you may have used a word which has alternative meanings.

If you have too many results, you can either add another concept or remove some synonyms

If you have too few results, try searching with fewer concepts (identify the least most important to omit) or add more synonyms.

Your Faculty or Clinical Librarian will be able to assist with this process.

Further reading

- Other sources

- Journal Articles

- Books and Chapters

Related Guides

- Systematic Reviews

- Using MultiSearch

We have guidance on Literature Reviews in StudyWISE . This guides focuses on the writing skills associated with Literature Reviews.

You'll find it on iLearn (Macquarie University's learning portal)

- << Previous: Search, Select, Evaluate

- Next: Referencing >>

- Last Updated: Mar 25, 2024 11:30 AM

- URL: https://libguides.mq.edu.au/psychology

Writing a Literature Review

What is a literature review.

- Research Topic | Research Questions

- Outline (Example)

- What Types of Literature Should I Use in My Review?

- Project Planner: Literature Review

- Writing a Literature Review in Psychology

- Literature Review tips (video)

Table of Contents

- What is a literature review?

- How is a literature review different from a research article?

- The two purposes: describe/compare and evaluate

- Getting started Select a topic and gather articles

- Choose a current, well-studied, specific topic

- Search the research literature

- Read the articles

- Write the literature review

- Structure How to proceed: describe, compare, evaluate

Literature reviews survey research on a particular area or topic in psychology. Their main purpose is to knit together theories and results from multiple studies to give an overview of a field of research.

How is a Literature Review Different from a Research Article?

Research articles:

- are empirical articles that describe one or several related studies on a specific, quantitative, testable research question

- are typically organized into four text sections: Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion

The Introduction of a research article includes a condensed literature review. Its purpose is to describe what is known about the area of study, with the goal of giving the context and rationale for the study itself. Published literature reviews are called review articles. Review articles emphasize interpretation. By surveying the key studies done in a certain research area, a review article interprets how each line of research supports or fails to support a theory. Unlike a research article, which is quite specific, a review article tells a more general story of an area of research by describing, comparing, and evaluating the key theories and main evidence in that area.

The Two Purposes of a Literature Review

Your review has two purposes:

(1) to describe and compare studies in a specific area of research and

(2) to evaluate those studies. Both purposes are vital: a thorough summary and comparison of the current research is necessary before you can build a strong evaluative argument about the theories tested.

Getting Started

(1) Select a research topic and identify relevant articles.

(2) Read the articles until you understand what about them is relevant to your review.

(3) Digest the articles: Understand the main points well enough to talk about them.

(4) Write the review, keeping in mind your two purposes: to describe and compare, and to evaluate.

SELECT A TOPIC AND COLLECT ARTICLES

Choose a current, well-studied, specific topic.

Pick a topic that interests you. If you're interested in a subject, you're likely to already know something about it. Your interest will help you to choose meaningful articles, making your paper more fun both to write and to read. The topic should be both current and well studied. Your goal is to describe and evaluate recent findings in a specific area of research, so pick a topic that you find in current research journals. Find an area that is well defined and well studied, meaning that several research groups are studying the topic and have approached it from different perspectives. If all the articles you find are from the same research group (i.e., the same authors), broaden your topic or use more general search terms.

You may need to narrow your topic. The subject of a short literature review must be specific enough, yet have sufficient literature on the subject, for you to cover it in depth. A broad topic will yield thousands of articles, which is impossible to survey meaningfully. If you are drowning in articles, or each article you find seems to be about a completely different aspect of the subject, narrow your topic. Choose one article that interests to you and focus on the specific question investigated. For example, a search for ‘teenage alcohol use’ will flood you with articles, but searching for ‘teenage alcohol use and criminal behavior’ will yield both fewer and more focused articles.

You may need to broaden your topic. You need enough articles on your topic for a thorough review of the research. If you’re unable to find much literature on your topic, or if you find articles you want that are not easy to find online, broaden your topic. What’s a more general way to ask your question of interest? For example, if you’re having a hard time finding articles on ‘discrimination against Asian-American women in STEM fields,’ broaden your topic (e.g., ‘academic discrimination against Asian-American women’ or ‘discrimination against women in STEM.’)

Consider several topics, and keep an open mind. Don't fall in love with a topic before you find how much research has been done in that area. By exploring different topics, you may discover something that is newly exciting to you!

Search the Research Literature

Do a preliminary search. Use online databases to search the research literature. If you don’t know how to search online databases, ask your instructor or reference librarian. Reference librarians are invaluable!

Search for helpful articles. Find one or more pivotal articles that can be a foundation for your paper. A pivotal article may be exceptionally well written, contain particularly valuable citations, or clarify relationships between different but related lines of research. Two sources of such articles in psychology are:

- Psychological Bulletin •

- Current Directions in Psychological Science (published by the American Psychological Society) has general, short articles written by scientists who have published a lot in their research area

How many articles? Although published review articles may cite more than 100 articles, literature reviews for courses are often shorter because they present only highlights of a research area and are not exhaustive. A short literature review may survey 7-12 research articles and be about 10-15 pages long. For course paper guidelines, ask your instructor.

Choose representative articles, not just the first ones you find. This consideration is more important than the length of your review.

Choose readable articles. Some research areas are harder to understand than others. Scan articles in the topic areas you are considering to decide on the readability of the research in those areas.

READ THE ARTICLES

To write an effective review, you’ll need a solid grasp of the relevant research. Begin by reading the article you find easiest. Read, re-read, and mentally digest it until you have a conversational understanding of the paper. You don’t know what you know until you can talk about it. And if you can’t talk about it, you won’t be able to write about it.

Read selectively. Don't start by reading the articles from beginning to end. First, read just the Abstract to get an overview of the study.

Scan the article to identify the answers to these “Why-What-What-What” questions:

- Why did they do the study? Why does it matter?

- What did they do?

- What did they find?

- What does it mean?

The previous four questions correspond to these parts of a research article:

- Introduction: the research question and hypotheses

Create a summary sheet of each article’s key points. This will help you to integrate each article into your paper.

TIP: Give Scholarcy a try.

Read for depth. After you understand an article’s main points, read each section in detail for to gain the necessary indepth understanding to compare the work of different researchers.

WRITE THE LITERATURE REVIEW

Your goal is to evaluate a body of literature; i.e., to “identify relations, contradictions, gaps, and inconsistencies” and “suggest next steps to solve the research problem” (APA Publication Manual 2010, p. 10). Begin writing when you have decided on your story and how to organize your research to support that story.

Organization

Organize the literature review to highlight the theme that you want to emphasize – the story that you want to tell. Literature reviews tend to be organized something like this:

Introduction:

- Introduce the research topic (what it is, why does it matter)

- Frame the story: narrow the research topic to the studies you will discuss

- Briefly outline how you have organized the review

- Headings. Use theme headings to organize your argument (see below)

- Describe the relevant parts of each study and explain why it is relevant to the subtopic at hand.

- Compare the studies if need be, to discuss their implications (i.e., your interpretation of what the studies show and whether there are important differences or similarities)

- Evaluate the importance of each study or group of studies, as well as the implications for the subtopic, and where research should go from here (on the level of the subtopic)

Conclusion: Final evaluation, summation and conclusion

Headings. Use headings to identify major sections that show the organization of the paper. (Headings also help you to identify organizational problems while you’re writing.) Avoid the standard headings of research articles (Introduction, Method, Results, Discussion). Use specific, conceptual headings. If you are reviewing whether facial expressions are universally understood, headings might include Studies in Western Cultures and Studies in Non-Western Cultures. Organize your argument into topics that fit under each heading (one or more per heading).

Describe. For each section or subtopic, briefly describe each article or line of research. Avoid sudden jumps betewen broader and narrower ideas. Keep your story in mind to help keep your thoughts connected.

Compare. For each section or topic, compare related studies, if this is relevant to your story. Comparisons may involve the research question, hypotheses, methods, data analysis, results, or conclusions. However, you don’t want to compare everything. That wouldn’t be a story! Which parts are relevant? What evidence supports your arguments? Identifying strengths and weaknesses of each study will help you make meaningful comparisons.

If you're having trouble synthesizing information, you probably don't understand the articles well. Reread sections you don’t understand. Discuss the studies with someone: you don’t know what you know until you can talk about it.

Evaluate. Descriptions/comparisons alone are not illuminating. For each section or topic, evaluate the studies you have reviewed based on your comparisons. Tell your reader what you conclude, and why. Evaluating research is the most subjective part of your paper. Even so, always support your claims with evidence. Evaluation requires much thought and takes on some risk, but without it, your paper is just a book report.

Final evaluation and summation. On a broader scale, relating to your main theme, tell your reader what you conclude and why. Reiterate your main claims and outline the evidence that supports them.

Conclusion. How does your evaluatio change or add to current knowledge in the field field? What future studies are implied by your analysis? How would such studies add to current knowledge of the topic?

The purpose of a literature review is to survey, describe, compare, and evaluate research articles on a particular topic. Choose a current topic that is neither too broad nor too narrow. Find the story that you want to tell. Spend a lot of time reading and thinking before you write. Think critically about the main hypotheses, findings, and arguments in a line of research. Identify areas of agreement among different articles as well as their differences and areas for future study. Expect to revise your review many times to refine your story. A well-written literature review gives the reader a comprehensive understanding of the main findings and remaining questions brought about by research on that topic.

- << Previous: Project Planner: Literature Review

- Next: Literature Review tips (video) >>

- Last Updated: Apr 4, 2024 1:35 PM

- URL: https://gbc.libguides.com/literature_review

University of Houston Libraries

Psychology resources.

- Background Information

- Literature Review

- Tests and Measurements

- Citing Sources This link opens in a new window

- Need More Help?

What is a Literature Review?

If this is your first time having to do a literature review, you might be wondering what a "literature review" actually is. Typically, this entails searching through various databases to find peer-reviewed research within a particular topic of interest and then analyzing what you find in order to situate your own research within the existing works.

Watch the following video to learn more:

Video Transcript

What is Peer Review?

Most of your literature review will involve searching for sources that have gone through the peer-reviewed process. These are typically academic articles that have been published in scholarly journals and have been vetted by other experts with knowledge of the topic at hand.

How Do I Find Psychology Literature?

The following database are a great place to start to find relevant, peer-reviewed literature within the broad research area of psychology:

- APA PsycInfo This link opens in a new window From the American Psychological Association (APA), PsycINFO contains nearly 2.3 million citations and abstracts of scholarly journal articles, book chapters, books, and dissertations in psychology and related disciplines. It is the largest resource devoted to peer-reviewed literature in behavioral science and mental health.

- DynaMed This link opens in a new window A clinical reference tool of more than 3000 topics designed for physicians and health care professionals for use primarily at the point-of-care. DynaMed is updated daily and monitors the content of over 500 medical journal and systemic evidence review databases.

- EMBASE This link opens in a new window EMBASE is a major biomedical and pharmaceutical database indexing over 3,500 international journals in the following fields of health sciences and biomedical research. It is considered as the European version of Medline.

- MEDLINE with Full Text This link opens in a new window A bibliographic database that contains more than 26 million references to journal articles in life sciences with a concentration on biomedicine. A distinctive feature of MEDLINE is that the records are indexed with NLM Medical Subject Headings (MeSH®).

- PubMed This link opens in a new window PubMed® comprises more than 30 million citations for biomedical literature from MEDLINE, life science journals, and online books.

- Web of Science This link opens in a new window Web of Science is a comprehensive research database. It contains records of journal articles, patents, and conference proceedings, It also provides a variety of search and analysis tools. Web of Science Core Collection is a painstakingly selected, actively curated database of the journals that researchers themselves have judged to be the most important and useful in their fields

- << Previous: Background Information

- Next: Tests and Measurements >>

- Last Updated: Aug 12, 2023 11:20 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uh.edu/psychology

- SUNY Oswego, Penfield Library

- Resource Guides

Psychology Research Guide

- Literature Reviews

- Research Starters

- Find Tests and Measures

Conducting Literature Reviews

Finding literature reviews in psycinfo, more help on conducting literature reviews.

- How to Read a Scientific Article

- Citing Sources

- Peer Review

Quick Links

- Penfield Library

- Research Guides

- A-Z List of Databases & Indexes

The APA definition of a literature review (from http://www.apa.org/databases/training/method-values.html ):

Survey of previously published literature on a particular topic to define and clarify a particular problem; summarize previous investigations; and to identify relations, contradictions, gaps, and inconsistencies in the literature, and suggest the next step in solving the problem.

Literature Reviews should:

- Key concepts that are being researched

- The areas that are ripe for more research—where the gaps and inconsistencies in the literature are

- A critical analysis of research that has been previously conducted

- Will include primary and secondary research

- Be selective—you’ll review many sources, so pick the most important parts of the articles/books.

- Introduction: Provides an overview of your topic, including the major problems and issues that have been studied.

- Discussion of Methodologies: If there are different types of studies conducted, identifying what types of studies have been conducted is often provided.

- Identification and Discussion of Studies: Provide overview of major studies conducted, and if there have been follow-up studies, identify whether this has supported or disproved results from prior studies.

- Identification of Themes in Literature: If there has been different themes in the literature, these are also discussed in literature reviews. For example, if you were writing a review of treatment of OCD, cognitive-behavioral therapy and drug therapy would be themes to discuss.

- Conclusion/Discussion—Summarize what you’ve found in your review of literature, and identify areas in need of further research or gaps in the literature.

Because literature reviews are a major part of research in psychology, Psycinfo allows you to easily limit to literature reviews. In the advanced search screen, you can select "literature review" as the methodology.

Now all you'll need to do is enter your search terms, and your results should show you many literature reviews conducted by professionals on your topic.

When you find an literature review article that is relevant to your topic, you should look at who the authors cite and who is citing the author, so that you can begin to use their research to help you locate sources and conduct your own literature review. The best way to do that is to use the "Cited References" and "Times Cited" links in Psycinfo, which is pictured below.

This article on procrastination has 423 references, and 48 other articles in psycinfo are citing this literature review. And, the citations are either available in full text or to request through ILL. Check out the article "The Nature of Procrastination" to see how these features work.

By searching for existing literature reviews, and then using the references of those literature reviews to begin your own literature search, you can efficiently gather the best research on a topic. You'll want to keep in mind that you'll need to summarize and analyze the articles you read, and won't be able to use every single article you choose.

You can use the search box below to get started.

Adelphi Library's tutorial, Conducting a Literature Review in Education and the Behavioral Sciences covers how to gather sources from library databases for your literature review.

The University of Toronto also provides "A Few Tips on Conducting a Literature Review" that offers some good advice and questions to ask when conducting a literature review.

Purdue University's Online Writing Lab (OWL) has several resources that discuss literature reviews:

http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/666/01/

https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/994/04/ (for grad students, but is still offers some good tips and advice for anyone writing a literature review)

Journal articles (covers more than 1,700 periodicals), chapters, books, dissertations and reports on psychology and related fields.

- PsycINFO This link opens in a new window

- << Previous: Handbooks

- Next: How to Read a Scientific Article >>

- University of La Verne

- Subject Guides

PSY 306: Cognitive Psychology

- Literature Reviews

- Find Articles

- What is a Literature Review?

- Literature Review Resources

- Literature Review Books

- The 5 Steps to Writing a Literature Review

- APA Citations

- Organize Citations

- A literature review is a critical, analytical summary and synthesis of the current knowledge of a topic. As a researcher, you collect the available literature on a topic, and then select the literature that is most relevant for your purpose. Your written literature review summarizes and analyses the themes, topics, methods, and results of that literature in order to inform the reader about the history and current status of research on that topic.

What purpose does a literature review serve?

- The literature review informs the reader of the researcher's knowledge of the relevant research already conducted on the topic under discussion, and places the author's current study in context of previous studies.

- As part of a senior project, the literature review points out the current issues and questions concerning a topic. By relating the your research to a knowledge gap in the existing literature, you should demonstrate how his or her proposed research will contribute to expanding knowledge in that field.

- Short Literature Review Sample This literature review sample guides students from the thought process to a finished review.

- Literature Review Matrix (Excel Doc) Excel file that can be edited to suit your needs.

- Literature Review Matrix (PDF) Source: McLean, Lindsey. "Literature Review." CORA (Community of Online Research Assignments), 2015. https://www.projectcora.org/assignment/literature-review.

- Academic Writer (formerly APA Style Central) This link opens in a new window Academic Writer (formerly APA Style Central) features three independent but integrated centers that provide expert resources necessary for teaching, learning, and applying the rules of APA Style.

- Sample Literature Reviews: Univ. of West Florida Literature review guide from the University of West Florida library guides.

- Purdue University Online Writing Lab (OWL) Sample literature review in APA from Purdue University's Online Writing Lab (OWL)

- << Previous: Find Articles

- Next: APA Citations >>

- Last Updated: Oct 25, 2023 3:06 PM

- URL: https://laverne.libguides.com/psy306

- Home | Introduction Page

- Find Articles

- APA Formatting

- Literature Reviews

- Tests/Measures/Surveys

How to write a literature review

For more detailed information on Literature Reviews and how to write them, see our Literature Review Guide .

Introduction

A literature review surveys scholarly articles, books and other sources (e.g. dissertations, conference proceedings) relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory. Literature reviews provide a description, summary, and critical evaluation of each work. The purpose is to offer an overview of significant literature published on a topic.

Similar to primary research, development of the literature review requires four stages:

- Problem formulation—which topic or field is being examined and what are its component issues?

- Literature search—finding materials relevant to the subject being explored

- Data evaluation—determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic

- Analysis and interpretation—discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature

Literature reviews should comprise the following elements:

- An overview of the subject, issue or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review

- Division of works under review into categories (e.g. those in support of a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative theses entirely)

- Explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research

In assessing each piece, consideration should be given to:

- Provenance—What are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence (e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings)?

- Objectivity—Is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness—Which of the author's theses are most/least convincing?

- Value—Are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

Definition and Use/Purpose

A literature review may constitute an essential chapter of a thesis or dissertation, or may be a self-contained review of writings on a subject. In either case, its purpose is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to the understanding of the subject under review

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration

- Identify new ways to interpret, and shed light on any gaps in, previous research

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort

- Point the way forward for further research

- Place one's original work (in the case of theses or dissertations) in the context of existing literature

The literature review itself does not present new primary scholarship.

**Text from UC Santa Cruz University Literature Review Guide: http://guides.library.ucsc.edu/write-a-literature-review

- << Previous: APA Formatting

- Next: Tests/Measures/Surveys >>

- Last Updated: Sep 6, 2023 2:36 PM

- URL: https://library.ndnu.edu/psychology

Library Home

Academic Success Center

Emergency Information

© 2023 Notre Dame de Namur University. All rights reserved.

Notre Dame de Namur University 1500 Ralston Avenue Belmont, CA 94002 Map

- Open access

- Published: 14 May 2024

Pulling the lever in a hurry: the influence of impulsivity and sensitivity to reward on moral decision-making under time pressure

- Fiorella Del Popolo Cristaldi 1 ,

- Grazia Pia Palmiotti 2 ,

- Nicola Cellini 1 , 3 &

- Michela Sarlo 4

BMC Psychology volume 12 , Article number: 270 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

233 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Making timely moral decisions can save a life. However, literature on how moral decisions are made under time pressure reports conflicting results. Moreover, it is unclear whether and how moral choices under time pressure may be influenced by personality traits like impulsivity and sensitivity to reward and punishment.

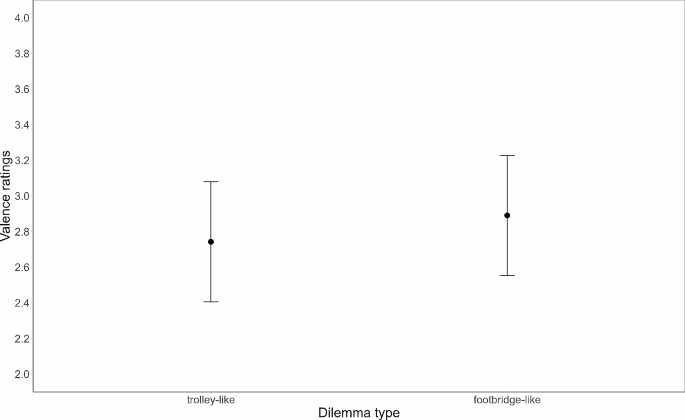

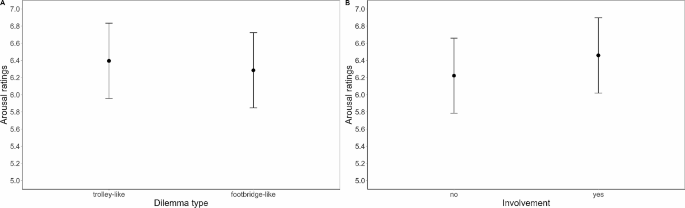

To address these gaps, in this study we employed a moral dilemma task, manipulating decision time between participants: one group ( N = 25) was subjected to time pressure (TP), with 8 s maximum time for response (including the reading time), the other ( N = 28) was left free to take all the time to respond (noTP). We measured type of choice (utilitarian vs. non-utilitarian), decision times, self-reported unpleasantness and arousal during decision-making, and participants’ impulsivity and BIS-BAS sensitivity.

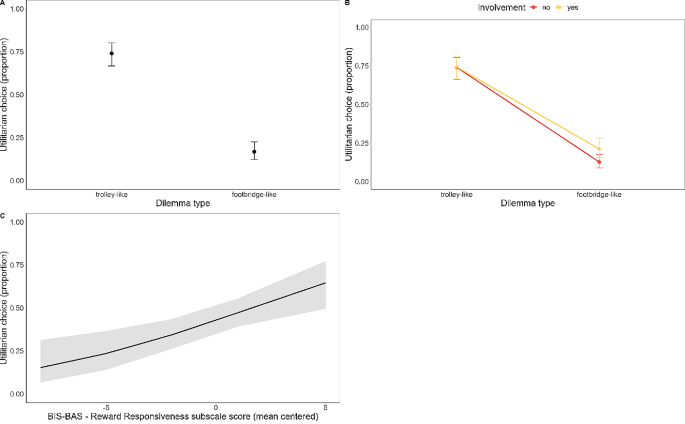

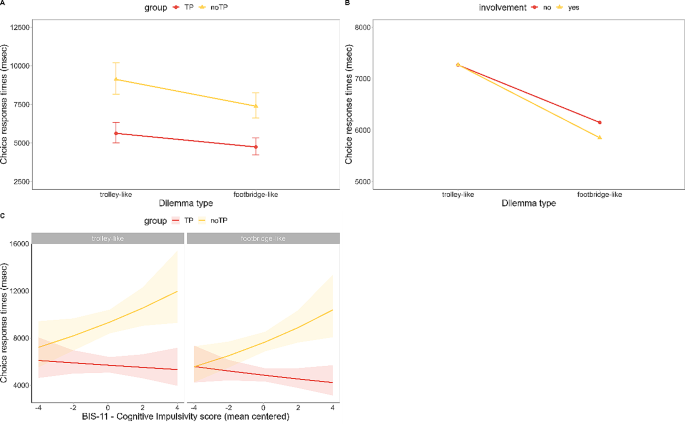

We found no group effect on the type of choice, suggesting that time pressure per se did not influence moral decisions. However, impulsivity affected the impact of time pressure, in that individuals with higher cognitive instability showed slower response times under no time constraint. In addition, higher sensitivity to reward predicted a higher proportion of utilitarian choices regardless of the time available for decision.

Conclusions

Results are discussed within the dual-process theory of moral judgement, revealing that the impact of time pressure on moral decision-making might be more complex and multifaceted than expected, potentially interacting with a specific facet of attentional impulsivity.

Peer Review reports

Making timely moral decisions is a real challenge, as emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic where physicians and nurses were forced to quickly choose which patients to treat first under limited healthcare resources.

Sacrificial moral dilemmas are reliable experimental probes to study the contribution of cognitive and emotional processes to moral decision-making [ 1 ]. In these studies, participants are confronted with life-and-death hypothetical scenarios where they have to decide whether to endorse or reject the utilitarian choice of killing one person to save more lives. In the classic Trolley dilemma, the utilitarian option requires pulling a lever to redirect a runaway trolley, which would kill five workmen, onto a sidetrack where it will kill only one person; in the Footbridge version, it requires pushing one large man off an overpass onto the tracks to stop the runaway trolley. Research consistently showed that most people respectively endorse and reject the utilitarian resolution in trolley- and footbridge-like dilemmas, despite the identical cost-benefit trade-off [ 1 , 2 , 3 ].

According to the dual-process model of moral judgement [ 1 ], responses to moral dilemmas are driven by the outcomes of a competition between cognitive and emotional processes. In the Footbridge case, a strong emotional aversive reaction to causing harm to one person overrides a cognitive-based analysis of saving more lives, driving toward the rejection of the utilitarian resolution because harming someone is perceived as an intended means to an end. Instead, in the Trolley case, a lower emotional engagement allows the deliberate cost-benefit reasoning to prevail and drive toward the utilitarian choice since harming someone is perceived as an unintended side effect. Therefore, dilemma resolutions vary depending on how much each dilemma type elicits aversive emotions, so that the more emotional processes are engaged the higher the likelihood of rejecting utilitarian choices. Unsurprisingly, in scenarios where the decision-maker’s own life is at stake (“personal involvement”), this pattern reverses, so that a strong negative emotional reaction to self-sacrifice pushes towards utilitarian, self-protective behaviour [ 4 ].

Time is a key feature of high-stakes human choices. Time pressure alters decision-making by increasing reliance on emotional states [ 5 ]. Previous research in moral decision-making has demonstrated that time pressure affects the outcomes and the processes involved in moral judgement, as it is assumed to reduce the time for the cost-benefit calculation letting emotional processes prevail. This led to a reduced proportion of utilitarian choices [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ], and a decreased willingness to self-sacrifice in dilemmas with personal involvement [ 11 ]. However, evidence remains mixed, with some studies suggesting that reduced decision times are associated with a higher proportion of utilitarian choices [ 12 , 13 ], and other studies finding null results [ 14 ]. Moreover, very few studies have investigated if these phenomena are influenced by personality traits known to affect how people make decisions. Among these, impulsivity and motivational drives towards action/inhibition seem particularly relevant.

Impulsivity involves multiple cognitive and behavioural domains (e.g., inability to reflect on choices’ outcomes, to defer rewards, and to inhibit prepotent responses; [ 15 ]) that are strongly involved in decision-making. Beyond research on psychopathy, studies investigating the role of impulsivity in moral dilemmas are surprisingly scarce. Within moral judgments, higher impulsivity should reduce the engagement of deliberative processes, thereby allowing emotional processes to prevail. Nonetheless, previous studies measuring impulsivity in moral judgement tasks have found no effects of impulsivity on the type of resolutions taken [ 16 , 17 , 18 ], and to our knowledge, no study has manipulated decision times.

Motivational drives towards action/inhibition, namely the Behavioural Inhibition and Activation Systems (BIS/BAS), are worthy of investigation, too. Indeed, the BIS is sensitive to signals of punishment, inhibiting behaviours leading to negative outcomes or potential harm; whereas the BAS is sensitive to reward, driving to behaviours resulting in positive outcomes [ 19 ]. Within moral dilemmas, “reward” corresponds to the maximisation of lives saved, thereby driving towards utilitarian resolutions. Consistently, previous research [ 20 ] showed that higher BAS individuals tended to make an overall higher number of utilitarian choices, while higher BIS participants tended to reject utilitarian resolutions, particularly in footbridge-like dilemmas. Notably, without time constraints no effects of BIS-BAS emerged on response times.