- Our Mission

Preparing Social Studies Students to Think Critically in the Modern World

Vetting primary resources isn’t easy—but doing it well is crucial for fostering engagement and deeper learning in a rapidly changing world.

In an era when students must sort through increasingly complex social and political issues, absorbing news and information from an evolving digital landscape, social studies should be meaningful and engaging—a means for preparing students for the modern world, writes Paul Franz for EdSurge . Yet much of our social studies curricula emphasizes content knowledge over the development of foundational, critical thinking skills such as understanding the context in which primary sources were created, and determining the credibility of resources.

“The consequence of this approach, coupled with a preference by many schools for multiple-choice assessments, turns out students who are disillusioned with social studies—and creates an environment where “accumulating knowledge and memorizing information is emphasized because that’s what counts on standardized tests,” writes Franz.

In his book Why Learn History (When It’s Already on Your Phone) , author Sam Wineburg, a professor at Stanford’s Graduate School of Education, examines how historians approach resources and argues that this is how teachers should be rigorously vetting—and teaching students to vet—social studies materials for the classroom.

Wineburg first describes how an AP US History student analyzes a New York Times article from 1892 about the creation of Discovery Day, later renamed Columbus Day. The student criticizes the article for celebrating Columbus as a noble hero when, in fact, he “captured and tortured Indians.” However, when real-life historians examine the same article, Wineburg notes that their approach is “wildly different.”

“When historians encounter this resource, their first move is to source it and put it in context, not to engage with the content,” writes Franz. “This article, to them, isn’t really about Columbus at all. It’s about President Harrison, who was responsible for the proclamation, and the immigration politics of the 1890s.”

The skills demonstrated by the historians are the same skills that should form the core of effective social studies education, according to Franz:

- Assessing the point of view of an author and source

- Placing arguments in context

- Validating the veracity of a claim

It is critical that teachers model this process for students: “Vetting social studies resources is important not just because we want to ensure students are learning from accurate, verifiable materials. It’s important also because the ability to ask questions about sources, bias, and context are at the heart of social studies education and are essential skills for thriving in the modern world.”

Much like historians, professional fact-checkers verify digital resources by using lateral reading. As opposed to vertical reading, where a reader might stay within a single website to evaluate a factual claim, fact-checkers scan a resource briefly, then open up new browser tabs to read more widely about the original site and verify its credibility via outside sources. This process mirrors how historians vet primary sources.

Teachers may also, of course, choose to rely on vetted social studies resources and lessons published by reputable sources—Franz recommends Newsela, Newseum, The National Archives, and the Stanford History Education Group.

Encouraging students to seek out knowledge and ideas, and then to deeply explore the reliability of their sources by considering their context, perspective, and accuracy should be the core skill of any rigorous social studies curriculum.

Join the Mailing List

Search the blog.

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

Alyssa Teaches

an Upper Elementary Blog

Critical Thinking in Your Social Studies Lessons

If your state is like mine, you’re expected to teach critical thinking skills in every subject. And it makes sense why! We want our students to be evaluating content and creating solutions – not just memorizing facts. Today, I want to share some easy ways to get your students using critical thinking skills in social studies.

What Critical Thinking Skills Can I Teach?

Practically all of them!

Here are just a few skills you can integrate into your history lessons:

- ask questions

- determine credibility and evaluate bias

- interpret sources

- recognize a variety of perspectives

- analyze choices

- compare and contrast

- determine relationships

- sequence events

- draw conclusions based on evidence

- differentiate facts from opinions

- explore impact

A lot of the social studies activities you’re using probably include some critical thinking skills! Let’s take a look at some simple strategies you can try to include more critical thinking opportunities in your lessons.

Ask Questions

A simple way to encourage students to dig a little deeper when they learn about history is to use higher-order thinking questions. Once they know the what, where, who, and when, you can guide students to explore the HOW and WHY. What were the causes of these events? What effects did they have? How did they impact different groups of people then and now?

Inquiry-based lessons are a great way to get students using these skills. Plus, they give them ownership of what they’re learning and help to increase engagement.

If you want to start a little more low-key, you can use some HOTS question prompts. A simple “parking lot” or bulletin board where students can record questions is also a good place to begin.

Analyze Primary Sources

I LOVE using primary sources to teach social studies. Primary source analysis requires students to use their background knowledge and observational skills to draw conclusions about history.

I almost always have students collaborate when they work with primary sources so they can bounce ideas off each other. I also usually use DBQs or question prompts so they have some direction. Afterward, I like to follow up with a whole-class discussion to debrief.

Compare & Contrast

A simple Venn diagram or t-chart is a great way for students to compare people, places, civilizations, artifacts, inventions, events, and time periods from history.

Plus, comparing helps students identify connections between people/places and over time.

Use Sorting Activities

Sorting activities are one of my favorite ways to get students thinking critically. They’re hands-on, interactive, and perfect for kids to do with a partner or in a small group.

You can assign an open sort, where students sort cards with words and/or pictures according to their own categories by looking for connections or patterns. I love this activity because it helps me see how students think.

Another option is to do a closed sort where you can ask students to sort according to specific rules. For example, they might sequence events into a timeline or sort them into cause-and-effect relationships. To make it more challenging, you can involve some inferencing scenarios. For instance, you can have them match quotes to the person or group that would’ve been likely to say them.

Explore Perspectives

We want students to consider a variety of perspectives and points of view when they learn about different historical events or periods. Primary sources are very helpful here, especially if you can find letters or diary entries. Picture books are another good option if you can find ones that provide different perspectives on a topic.

An easy activity is to use two different quotes about an event (that represent two points of view) and have students analyze their differences. Again, guiding questions or prompts will help them to understand the perspectives of different groups of people. One activity I’ve used is to explore the English colonization of Jamestown from Captain John Smith’s perspective compared to Chief Powhatan’s.

Even creating a fake social media profile for a historical figure can help students think critically about someone’s needs, wants, and point-of-view.

Look at Cause and Effect

I think that exploring cause and effect relationships in history helps students understand the impact of events that have taken place. I like using a simple graphic organizer that has room for multiple causes and effects. (Cause and effect is also a good place to tie in perspectives and connections.)

Analyze Decision Making

Another critical thinking activity you can use is to analyze specific choices that people made.

A decision-making model graphic organizer helps students determine the costs and benefits of a choice or event. For example, they can weigh the costs and benefits of the 13 Colonies declaring independence from Great Britain.

A good extension activity is to have students discuss alternate decisions that could have been made. They can hypothesize how different choices would have changed history.

Investigate the Impact of Geography

Geography has played such a huge role in human history, but it’s not something our students always think about. It helps to use activities that encourage students to consider the specific ways geography has affected people. Comparing early maps to current maps is one option. And I love having students explore locations with Google Earth.

You can also practice this skill with the 5 themes of geography .

Research and Create Products

Finally, social studies research projects are a great way to use critical thinking skills. Students can take their research and create an artifact or product to apply their knowledge. They can also design solutions for the future based on what they’ve learned.

I’m all about finding ways to make social studies engaging . Incorporating critical thinking skills into your social studies lessons is a great way to challenge students, and it doesn’t have to be complicated. I hope you give some of these activities a try!

Related posts

How to Make Social Studies Interesting

Teaching Point of View in Social Studies

Top 12 Jamestown Books for Kids

No comments, leave a reply cancel reply, join the mailing list for tips, ideas, and freebies.

- Mentor Teacher

- Organization

- Social Studies

- Teacher Tips

- Virginia Studies

Improving Social Studies Students’ Critical Thinking

- First Online: 01 January 2014

Cite this chapter

- Khe Foon Hew 3 &

- Wing Sum Cheung 4

Part of the book series: SpringerBriefs in Education ((BRIEFSEDUCAT))

2539 Accesses

2 Citations

The ability to think critically along with an awareness of local and global issues have been identified as important competencies that could benefit students as they journey through life in the 21st century (Voogt and Roblin 2012 ). Social studies, as a subject discipline, could serve as a conducive environment for the development of such competencies because it not only aims to equip students with information about important social-cultural issues within and without a country but also to inculcate critical thinking ability whereby students review, analyze, and make appropriate judgments based on particular evidences or ideas presented. This chapter reports a study that examines the effect of using blended learning approaches on social studies students’ critical thinking. This study relied on objective measurements of students’ critical thinking such as their actual performance scores, rather than students’ self-report data of their critical thinking levels. It employed a one-group pre- and post-test research design to examine the impact of a Socratic question-blogcast model on grade 10 students’ ability to critically evaluate controversial social studies issues. A paired-samples t -test was conducted to determine the potential critical thinking gain using a validated rubric. There was a significant difference in critical thinking between pre-intervention ( M = 2.33 SD = 1.240) and post-intervention ( M = 3.19 SD = 1.388), t (26) = −3.690, p < 0.001, with an effect size of 0.67. We also reported students’ perceptions of the Socratic question-blogcast blended learning approach to provide additional qualitative insights into how the approach was particularly helpful to the students.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Abrami, P. C., Bernard, R. M., Borokhovski, E., Wade, A., Surkes, M. A., Tamim, R., & Zhang, D. (2008). Instructional interventions affecting critical thinking skills and dispositions: A stage 1 meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 78 (4), 1102–1134.

Google Scholar

Allen, J. (1994). If this is history, why isn’t it boring? In S. Steffey & W. J. Hood (Eds.), If this is social studies, why isn’t it boring? (pp. 1–12). York: Stenhouse.

Bjork, R. A. (1999). Assessing our own competence: Heuristics and illusions. In D. Gopher, A. Koriat (Eds.), Attention and performance XVII. Cognitive regulation of performance: Interaction of theory and application (pp. 435–459). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Black, M. S., & Blake, M. E. (2001). Knitting local history together: Collaborating to construct curriculum. The Social Studies, 92 (6), 243–247.

Article Google Scholar

Buckley, M. (1979). The development of verbal thinking and Its implications for teaching. Theory Into Practice, 18 (4), 295–297.

Burack, J. (2014). Interpreting political cartoons in the history classroom. Retrieved on 24 Feb 2014 from http://teachinghistory.org/teaching-materials/teaching-guides/21733 .

Case, R., & Wright, L. (1997). Taking seriously the teaching of critical thinking. In R. Case & P. Clark (Eds.), The Canadian anthology of social studies . Burnaby, BC: Field Relations and Teacher In-service Education, Simon Fraser University.

Chaffee, J. (1998). The thinker’s way: 8 steps to a richer life . USA: Little, Brown & Company.

Chance, P. (1986). Thinking in the classroom: A survey of programs . New York: Teachers College, Columbia University.

Colley, B. M., Bilics, A. R., & Lerch, C. M. (2012). Reflection: A key component to thinking critically. The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning , 3 (1). Retrieved on 25 Feb 2014 from http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/cjsotl_rcacea/vol3/iss1/2 .

Diem, R. A. (2000). Can it make a difference? Technology and the social studies. Theory and Research in Social Education, 28 (4), 493–501.

Dillon, J. T. (1988). Questioning and teaching: A manual of practice . New York: Teachers College Press.

Ellison, N. B., & Wu, Y. (2008). Blogging in the classroom: A preliminary exploration of student attitudes and impact on comprehension. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 17 (1), 99–122.

Ennis, R. (1989). Critical thinking and subject specificity: Clarification and needed research. Educational Researcher, 18 (3), 4–10.

Falchikov, N., & Boud, D. (1989). Student self-assessment in higher education: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 59 (4), 395–430.

Fertig, G. (2005). Teaching elementary students how to interpret the past. The Social Studies, 96 (1), 2–8.

Flammer, A. (1981). Towards a theory of question asking. Psychological Research 4 , 407–420.

Friedman, A. M., & Hicks, D. (2006). Guest editorial: The state of the field: Technology, social studies, and teacher education. Contemporary Issues in Technology in Teacher Education, 6 , 246–258.

Heitzmann, W. R. (1998). The power of political cartoons in teaching history . Westlake: National Council for History Education.

Henri, F. (1992). Computer conferencing and content analysis. In A. R. Kaye (Ed.), Collaborative learning through computer conferencing: The Najaden Papers (pp. 117–136). Berlin: Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Hew, K. F., & Cheung, W. S. (2013). Audio-based versus text-based asynchronous online discussion: Two case studies. Instructional Science, 41 (2), 365–380.

Jensen, M. (2001). Bring the past to life. The Writer, 114 (11), 30.

Kassirer, J. P., & Kopelman, R. I. (1991). Learning clinical reasoning . Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins.

King, A. (1990). Enhancing peer interaction and learning in classroom through reciprocal questioning. American Educational Research Journal, 27 (4), 664–687

Levans, N. E. (2007). Critical thinking in the secondary social studies classroom. Unpublished master project. Evergreen State College.

Maiorana, V. P. (1990–1991). The road from rote to critical thinking. Community Review, 11 (1–2), 53–63.

Martindale, T., & Wiley, D. A. (2004). An Introduction to Teaching with Weblogs. Retrieved March 15, 2008, from http://teachable.org/papers/2004_techtrends_bloglinks.htm

McLoughlin, C., & Lee, M. (2007). Listen and learn: A systematic review of the evidence that podcasting supports learning in higher education. In C. Montgomerie & J. Seale (Eds.), Proceedings of World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications 2007 (pp. 1669–1677). Chesapeake, VA: AACE.

Mezirow, J. (1990). Fostering critical reflection in adulthood: A guide to transformative and emancipatory learning . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS) (1994). Expectations of excellence: Curriculum standards for Social Studies . Washington, DC: NCSS.

Newman, D. R., Johnson, C., Webb, B., & Cochrane, C. (1997). Evaluating the quality of learning in computer supported cooperative learning. Journal of the American Society of Information Science, 48 , 484–495.

Ng, J. Y. (2012). Social Studies syllabus revamped to train critical thinking. Today . Retrieved from http://www.todayonline.com/Focus/Education/EDC121023-0000026/Social-Studies-syllabus-revamped-to-train-critical-thinking .

Paul, R. W. (1993). Critical thinking: What every person needs to survive in a rapidly changing world . CA: Foundation for Critical Thinking, Sonoma Valley University.

Phaneuf, M. (2009). The think-aloud protocol, adjunct or substitute for the nursing process . Retrieved on 25 Feb 2014 from http://www.infiressources.ca/fer/Depotdocument_anglais/The_think-aloud_protocol_adjunct_or_substitute_for_the_nursing_process.pdf .

Salam, S., & Hew, K. F. (2010). Enhancing social studies students’ critical thinking through blogcast and Socratic questioning: A Singapore case study. International Journal of Instructional Media, 37 (4), 391–401.

Schafersman, S.D. (1991). An introduction to critical thinking . Retrieved on 26 Aug 2011 from http://smartcollegeplanning.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/Critical-Thinking.pdf .

Schellens, T., Keer, H. V., De Wever, B., & Valcke, M. (2009). Tagging thinking types in asynchronous discussion groups: Effects on critical thinking. Interactive Learning Environments, 17 (1), 77–94.

Siegel, H. (1988). Educating reason: Rationality, critical thinking, and education . New York: Routledge.

Steinbrink, J. E., & Bliss, D. (1988). Using political cartoons to teach thinking skills. The Social Studies, 79 (5), 217–220.

Swartz, R. J. & Parks, S. (1994). Infusing the teaching of critical and creative thinking into content instruction. A lesson design handbook for the elementary grades. Critical Thinking Press & Software.

Taylor, L. (1992). Mathematics attitude development from a Vygotskian perspective. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 4 , 8–23.

Vogler, K. (2004). Using political cartoons to improve your verbal questioning. Social Studies, 95 (1), 11–15.

Voogt, J., & Roblin, N. P. (2012). A comparative analysis of international frameworks for 21st century competences: Implications for national curriculum policies. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 44 (3), 299–321.

Wade, S., Niederhauser, D. S., Cannon, M., & Long, T. (2001). Electronic discussions in an issues course. Expanding the boundaries of the classroom. Journal of Computing in Teacher Education, 17 (3), 4–9.

Waring, S. M., & Robinson, K. S. (2010). Developing critical historical thinking skills in middle grades social studies. Middle School Journal , 22–28.

White, C. W. (1999). Transforming social studies education: A critical perspective . Springfield: Charles C. Thomas.

White, J. E., Nativio, D. G., Kobert, S. N., & Engberg, S. J. (1992). Content and process in clinical decision-making by nurse practitioners. IMAGE, 24 , 153–158.

Wright, I. (2002a). Challenging students with the tools of critical thinking. The Social Studies, 93 (6), 257–261.

Wright, I. (2002b). Critical thinking in the schools: Why doesn’t much happen? Informal Logic, 22 (2), 137–154.

Yang, S. C., & Chung, T.-Y. (2009). Experimental study of teaching critical thinking in civic education in Taiwanese junior high school. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 79 , 29–55.

Yang, Y.-T. C., Newby, T. J., & Bill, R. L. (2005). Using Socratic questioning to promote critical thinking skills through asynchronous discussion forums in distance learning environments. American Journal of Distance Education, 19 (3), 163–181.

Zhao, Y., & Hoge, J. D. (2005). What elementary students and teachers say about social studies. The Social Studies, 96 (5), 216–221.

Zohar, A., Weinberger, Y., & Tamir, P. (1994). The effect of the biology critical thinking project on the development of critical thinking. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 31 (2), 183–196.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Education, Division of Information and Technology Studies, The University of Hong Kong, Pok Fu Lam, Hong Kong SAR

Khe Foon Hew

Learning Sciences and Technologies, NIE, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, Singapore

Wing Sum Cheung

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Khe Foon Hew .

4.1.1 Activity 1

1. Instructions

Getting started:

Podcast your answer:

Study the background information, sources and question. Then answer the question orally and record it to audacity. Just say out whatever comes to mind. Do not worry if your ideas do not flow. This is only your first draft. You will be given a chance to improve on your answers later. Upload your podcast onto your blogcast account, which have been created for you. Do not spend more than 15 min on this activity!

2. The Question

Study this question carefully.

Study Source A

How reliable is the source as evidence to suggest that the Tamils formed a militant group due to the unfair university admission criteria? Explain your answer.

3. The Background Information

Read this carefully. It may help you to answer the questions.

After 1970, the government introduced new university admission criteria. Tamil students had to score higher marks than the Sinhalese students to enter the same courses in the universities. A fixed number of places were also reserved for the Sinhalese. Admission was no longer based solely on academic results. This became the main point of the conflict between the government and Tamil leaders. Tamil youths, resentful by what they considered discrimination against them, formed a militant group, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), more popularly known as Tamil Tigers, and resorted to violence to achieve its aim.

4. The Sources

A cartoon about university admission in Sri Lanka by a Tamil artist.

http://www.slideshare.net/khooky/srilanka-conflict-v09

A view expressed by a Sinhalese about the Tamils in Sri Lanka, 1995.

The LTTE terrorists complain that the Tamils have been treated unfairly. This is unfair. This is no longer true. They say they have been the victims of discrimination in university education, employment and in other matters controlled by the government. But most of their demands were met long ago. Discrimination exists in every society but in Sri Lanka it is less serious than in some countries. It certainly does not give them the right to kill people. The Tamils do not need to be freed by a group of terrorists. Discrimination is not the real reason for terrorism, it is just an excuse.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Hew, K.F., Cheung, W.S. (2014). Improving Social Studies Students’ Critical Thinking. In: Using Blended Learning. SpringerBriefs in Education. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-089-6_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-287-089-6_4

Published : 02 August 2014

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-287-088-9

Online ISBN : 978-981-287-089-6

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

Eight Instructional Strategies for Promoting Critical Thinking

- Share article

(This is the first post in a three-part series.)

The new question-of-the-week is:

What is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom?

This three-part series will explore what critical thinking is, if it can be specifically taught and, if so, how can teachers do so in their classrooms.

Today’s guests are Dara Laws Savage, Patrick Brown, Meg Riordan, Ph.D., and Dr. PJ Caposey. Dara, Patrick, and Meg were also guests on my 10-minute BAM! Radio Show . You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here.

You might also be interested in The Best Resources On Teaching & Learning Critical Thinking In The Classroom .

Current Events

Dara Laws Savage is an English teacher at the Early College High School at Delaware State University, where she serves as a teacher and instructional coach and lead mentor. Dara has been teaching for 25 years (career preparation, English, photography, yearbook, newspaper, and graphic design) and has presented nationally on project-based learning and technology integration:

There is so much going on right now and there is an overload of information for us to process. Did you ever stop to think how our students are processing current events? They see news feeds, hear news reports, and scan photos and posts, but are they truly thinking about what they are hearing and seeing?

I tell my students that my job is not to give them answers but to teach them how to think about what they read and hear. So what is critical thinking and how can we integrate it into the classroom? There are just as many definitions of critical thinking as there are people trying to define it. However, the Critical Think Consortium focuses on the tools to create a thinking-based classroom rather than a definition: “Shape the climate to support thinking, create opportunities for thinking, build capacity to think, provide guidance to inform thinking.” Using these four criteria and pairing them with current events, teachers easily create learning spaces that thrive on thinking and keep students engaged.

One successful technique I use is the FIRE Write. Students are given a quote, a paragraph, an excerpt, or a photo from the headlines. Students are asked to F ocus and respond to the selection for three minutes. Next, students are asked to I dentify a phrase or section of the photo and write for two minutes. Third, students are asked to R eframe their response around a specific word, phrase, or section within their previous selection. Finally, students E xchange their thoughts with a classmate. Within the exchange, students also talk about how the selection connects to what we are covering in class.

There was a controversial Pepsi ad in 2017 involving Kylie Jenner and a protest with a police presence. The imagery in the photo was strikingly similar to a photo that went viral with a young lady standing opposite a police line. Using that image from a current event engaged my students and gave them the opportunity to critically think about events of the time.

Here are the two photos and a student response:

F - Focus on both photos and respond for three minutes

In the first picture, you see a strong and courageous black female, bravely standing in front of two officers in protest. She is risking her life to do so. Iesha Evans is simply proving to the world she does NOT mean less because she is black … and yet officers are there to stop her. She did not step down. In the picture below, you see Kendall Jenner handing a police officer a Pepsi. Maybe this wouldn’t be a big deal, except this was Pepsi’s weak, pathetic, and outrageous excuse of a commercial that belittles the whole movement of people fighting for their lives.

I - Identify a word or phrase, underline it, then write about it for two minutes

A white, privileged female in place of a fighting black woman was asking for trouble. A struggle we are continuously fighting every day, and they make a mockery of it. “I know what will work! Here Mr. Police Officer! Drink some Pepsi!” As if. Pepsi made a fool of themselves, and now their already dwindling fan base continues to ever shrink smaller.

R - Reframe your thoughts by choosing a different word, then write about that for one minute

You don’t know privilege until it’s gone. You don’t know privilege while it’s there—but you can and will be made accountable and aware. Don’t use it for evil. You are not stupid. Use it to do something. Kendall could’ve NOT done the commercial. Kendall could’ve released another commercial standing behind a black woman. Anything!

Exchange - Remember to discuss how this connects to our school song project and our previous discussions?

This connects two ways - 1) We want to convey a strong message. Be powerful. Show who we are. And Pepsi definitely tried. … Which leads to the second connection. 2) Not mess up and offend anyone, as had the one alma mater had been linked to black minstrels. We want to be amazing, but we have to be smart and careful and make sure we include everyone who goes to our school and everyone who may go to our school.

As a final step, students read and annotate the full article and compare it to their initial response.

Using current events and critical-thinking strategies like FIRE writing helps create a learning space where thinking is the goal rather than a score on a multiple-choice assessment. Critical-thinking skills can cross over to any of students’ other courses and into life outside the classroom. After all, we as teachers want to help the whole student be successful, and critical thinking is an important part of navigating life after they leave our classrooms.

‘Before-Explore-Explain’

Patrick Brown is the executive director of STEM and CTE for the Fort Zumwalt school district in Missouri and an experienced educator and author :

Planning for critical thinking focuses on teaching the most crucial science concepts, practices, and logical-thinking skills as well as the best use of instructional time. One way to ensure that lessons maintain a focus on critical thinking is to focus on the instructional sequence used to teach.

Explore-before-explain teaching is all about promoting critical thinking for learners to better prepare students for the reality of their world. What having an explore-before-explain mindset means is that in our planning, we prioritize giving students firsthand experiences with data, allow students to construct evidence-based claims that focus on conceptual understanding, and challenge students to discuss and think about the why behind phenomena.

Just think of the critical thinking that has to occur for students to construct a scientific claim. 1) They need the opportunity to collect data, analyze it, and determine how to make sense of what the data may mean. 2) With data in hand, students can begin thinking about the validity and reliability of their experience and information collected. 3) They can consider what differences, if any, they might have if they completed the investigation again. 4) They can scrutinize outlying data points for they may be an artifact of a true difference that merits further exploration of a misstep in the procedure, measuring device, or measurement. All of these intellectual activities help them form more robust understanding and are evidence of their critical thinking.

In explore-before-explain teaching, all of these hard critical-thinking tasks come before teacher explanations of content. Whether we use discovery experiences, problem-based learning, and or inquiry-based activities, strategies that are geared toward helping students construct understanding promote critical thinking because students learn content by doing the practices valued in the field to generate knowledge.

An Issue of Equity

Meg Riordan, Ph.D., is the chief learning officer at The Possible Project, an out-of-school program that collaborates with youth to build entrepreneurial skills and mindsets and provides pathways to careers and long-term economic prosperity. She has been in the field of education for over 25 years as a middle and high school teacher, school coach, college professor, regional director of N.Y.C. Outward Bound Schools, and director of external research with EL Education:

Although critical thinking often defies straightforward definition, most in the education field agree it consists of several components: reasoning, problem-solving, and decisionmaking, plus analysis and evaluation of information, such that multiple sides of an issue can be explored. It also includes dispositions and “the willingness to apply critical-thinking principles, rather than fall back on existing unexamined beliefs, or simply believe what you’re told by authority figures.”

Despite variation in definitions, critical thinking is nonetheless promoted as an essential outcome of students’ learning—we want to see students and adults demonstrate it across all fields, professions, and in their personal lives. Yet there is simultaneously a rationing of opportunities in schools for students of color, students from under-resourced communities, and other historically marginalized groups to deeply learn and practice critical thinking.

For example, many of our most underserved students often spend class time filling out worksheets, promoting high compliance but low engagement, inquiry, critical thinking, or creation of new ideas. At a time in our world when college and careers are critical for participation in society and the global, knowledge-based economy, far too many students struggle within classrooms and schools that reinforce low-expectations and inequity.

If educators aim to prepare all students for an ever-evolving marketplace and develop skills that will be valued no matter what tomorrow’s jobs are, then we must move critical thinking to the forefront of classroom experiences. And educators must design learning to cultivate it.

So, what does that really look like?

Unpack and define critical thinking

To understand critical thinking, educators need to first unpack and define its components. What exactly are we looking for when we speak about reasoning or exploring multiple perspectives on an issue? How does problem-solving show up in English, math, science, art, or other disciplines—and how is it assessed? At Two Rivers, an EL Education school, the faculty identified five constructs of critical thinking, defined each, and created rubrics to generate a shared picture of quality for teachers and students. The rubrics were then adapted across grade levels to indicate students’ learning progressions.

At Avenues World School, critical thinking is one of the Avenues World Elements and is an enduring outcome embedded in students’ early experiences through 12th grade. For instance, a kindergarten student may be expected to “identify cause and effect in familiar contexts,” while an 8th grader should demonstrate the ability to “seek out sufficient evidence before accepting a claim as true,” “identify bias in claims and evidence,” and “reconsider strongly held points of view in light of new evidence.”

When faculty and students embrace a common vision of what critical thinking looks and sounds like and how it is assessed, educators can then explicitly design learning experiences that call for students to employ critical-thinking skills. This kind of work must occur across all schools and programs, especially those serving large numbers of students of color. As Linda Darling-Hammond asserts , “Schools that serve large numbers of students of color are least likely to offer the kind of curriculum needed to ... help students attain the [critical-thinking] skills needed in a knowledge work economy. ”

So, what can it look like to create those kinds of learning experiences?

Designing experiences for critical thinking

After defining a shared understanding of “what” critical thinking is and “how” it shows up across multiple disciplines and grade levels, it is essential to create learning experiences that impel students to cultivate, practice, and apply these skills. There are several levers that offer pathways for teachers to promote critical thinking in lessons:

1.Choose Compelling Topics: Keep it relevant

A key Common Core State Standard asks for students to “write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence.” That might not sound exciting or culturally relevant. But a learning experience designed for a 12th grade humanities class engaged learners in a compelling topic— policing in America —to analyze and evaluate multiple texts (including primary sources) and share the reasoning for their perspectives through discussion and writing. Students grappled with ideas and their beliefs and employed deep critical-thinking skills to develop arguments for their claims. Embedding critical-thinking skills in curriculum that students care about and connect with can ignite powerful learning experiences.

2. Make Local Connections: Keep it real

At The Possible Project , an out-of-school-time program designed to promote entrepreneurial skills and mindsets, students in a recent summer online program (modified from in-person due to COVID-19) explored the impact of COVID-19 on their communities and local BIPOC-owned businesses. They learned interviewing skills through a partnership with Everyday Boston , conducted virtual interviews with entrepreneurs, evaluated information from their interviews and local data, and examined their previously held beliefs. They created blog posts and videos to reflect on their learning and consider how their mindsets had changed as a result of the experience. In this way, we can design powerful community-based learning and invite students into productive struggle with multiple perspectives.

3. Create Authentic Projects: Keep it rigorous

At Big Picture Learning schools, students engage in internship-based learning experiences as a central part of their schooling. Their school-based adviser and internship-based mentor support them in developing real-world projects that promote deeper learning and critical-thinking skills. Such authentic experiences teach “young people to be thinkers, to be curious, to get from curiosity to creation … and it helps students design a learning experience that answers their questions, [providing an] opportunity to communicate it to a larger audience—a major indicator of postsecondary success.” Even in a remote environment, we can design projects that ask more of students than rote memorization and that spark critical thinking.

Our call to action is this: As educators, we need to make opportunities for critical thinking available not only to the affluent or those fortunate enough to be placed in advanced courses. The tools are available, let’s use them. Let’s interrogate our current curriculum and design learning experiences that engage all students in real, relevant, and rigorous experiences that require critical thinking and prepare them for promising postsecondary pathways.

Critical Thinking & Student Engagement

Dr. PJ Caposey is an award-winning educator, keynote speaker, consultant, and author of seven books who currently serves as the superintendent of schools for the award-winning Meridian CUSD 223 in northwest Illinois. You can find PJ on most social-media platforms as MCUSDSupe:

When I start my keynote on student engagement, I invite two people up on stage and give them each five paper balls to shoot at a garbage can also conveniently placed on stage. Contestant One shoots their shot, and the audience gives approval. Four out of 5 is a heckuva score. Then just before Contestant Two shoots, I blindfold them and start moving the garbage can back and forth. I usually try to ensure that they can at least make one of their shots. Nobody is successful in this unfair environment.

I thank them and send them back to their seats and then explain that this little activity was akin to student engagement. While we all know we want student engagement, we are shooting at different targets. More importantly, for teachers, it is near impossible for them to hit a target that is moving and that they cannot see.

Within the world of education and particularly as educational leaders, we have failed to simplify what student engagement looks like, and it is impossible to define or articulate what student engagement looks like if we cannot clearly articulate what critical thinking is and looks like in a classroom. Because, simply, without critical thought, there is no engagement.

The good news here is that critical thought has been defined and placed into taxonomies for decades already. This is not something new and not something that needs to be redefined. I am a Bloom’s person, but there is nothing wrong with DOK or some of the other taxonomies, either. To be precise, I am a huge fan of Daggett’s Rigor and Relevance Framework. I have used that as a core element of my practice for years, and it has shaped who I am as an instructional leader.

So, in order to explain critical thought, a teacher or a leader must familiarize themselves with these tried and true taxonomies. Easy, right? Yes, sort of. The issue is not understanding what critical thought is; it is the ability to integrate it into the classrooms. In order to do so, there are a four key steps every educator must take.

- Integrating critical thought/rigor into a lesson does not happen by chance, it happens by design. Planning for critical thought and engagement is much different from planning for a traditional lesson. In order to plan for kids to think critically, you have to provide a base of knowledge and excellent prompts to allow them to explore their own thinking in order to analyze, evaluate, or synthesize information.

- SIDE NOTE – Bloom’s verbs are a great way to start when writing objectives, but true planning will take you deeper than this.

QUESTIONING

- If the questions and prompts given in a classroom have correct answers or if the teacher ends up answering their own questions, the lesson will lack critical thought and rigor.

- Script five questions forcing higher-order thought prior to every lesson. Experienced teachers may not feel they need this, but it helps to create an effective habit.

- If lessons are rigorous and assessments are not, students will do well on their assessments, and that may not be an accurate representation of the knowledge and skills they have mastered. If lessons are easy and assessments are rigorous, the exact opposite will happen. When deciding to increase critical thought, it must happen in all three phases of the game: planning, instruction, and assessment.

TALK TIME / CONTROL

- To increase rigor, the teacher must DO LESS. This feels counterintuitive but is accurate. Rigorous lessons involving tons of critical thought must allow for students to work on their own, collaborate with peers, and connect their ideas. This cannot happen in a silent room except for the teacher talking. In order to increase rigor, decrease talk time and become comfortable with less control. Asking questions and giving prompts that lead to no true correct answer also means less control. This is a tough ask for some teachers. Explained differently, if you assign one assignment and get 30 very similar products, you have most likely assigned a low-rigor recipe. If you assign one assignment and get multiple varied products, then the students have had a chance to think deeply, and you have successfully integrated critical thought into your classroom.

Thanks to Dara, Patrick, Meg, and PJ for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo .

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching .

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email (The RSS feed for this blog, and for all Ed Week articles, has been changed by the new redesign—new ones won’t be available until February). And if you missed any of the highlights from the first nine years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below.

- This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

- Race & Racism in Schools

- School Closures & the Coronavirus Crisis

- Classroom-Management Advice

- Best Ways to Begin the School Year

- Best Ways to End the School Year

- Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

- Implementing the Common Core

- Facing Gender Challenges in Education

- Teaching Social Studies

- Cooperative & Collaborative Learning

- Using Tech in the Classroom

- Student Voices

- Parent Engagement in Schools

- Teaching English-Language Learners

- Reading Instruction

- Writing Instruction

- Education Policy Issues

- Differentiating Instruction

- Math Instruction

- Science Instruction

- Advice for New Teachers

- Author Interviews

- Entering the Teaching Profession

- The Inclusive Classroom

- Learning & the Brain

- Administrator Leadership

- Teacher Leadership

- Relationships in Schools

- Professional Development

- Instructional Strategies

- Best of Classroom Q&A

- Professional Collaboration

- Classroom Organization

- Mistakes in Education

- Project-Based Learning

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributors to this column .

The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Social Studies and Critical Thinking

2004, Critical Thinking and Learning

Related Papers

Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education

Dan Shevock

2015 Link to the Article: http://act.maydaygroup.org/articles/Shevock14_2.pdf Abstract Paulo Freire was an important figure in adult education whose pedagogy has been used in music education. In this act of praxis (reflection and action upon the world in order to transform it), I share an autoethnography of my teaching of a university-level small ensemble jazz class. The purpose of this autoethnography was to examine my teaching praxis as I integrated Freirean pedagogy. There were two research questions. To what extent were the teachings of Paulo Freire applicable or useful for a university-level, improvisational, small ensemble class? How do students’ confidence and ability at improvisation improve during the class? Data sources included teacher reflections, video-recordings of each class, and conversations on a Facebook page. In the Jazz Combo Lab, students who were unable to successfully navigate the competitive audition process were empowered to develop as jazz musicians and become critically reflective. A narrative of my own evolving praxis is shared around the themes “Freirean Pedagogy as Increased Conversation,” “Empowering Students to Critique Their Worlds,” “Pedagogical Missteps,” and “A More Critical Praxis.” Keywords: music education, Freire, jazz, pedagogy

E. Wayne Ross , Abraham DeLeon

[Winner of the 2011 “Critics Choice Award” from the American Educational Studies Association] "Critical Theories, Radical Pedagogies, and Social Education: New Perspectives for Social Studies Education begins with the assertion that there are emergent and provocative theories and practices that should be part of the discourse on social studies education in the 21st century. Anarchist, eco-activist, anti-capitalist, and other radical perspectives, such as disability studies and critical race theory, are explored as viable alternatives in responding to current neo-conservative and neo-liberal educational policies shaping social studies curriculum and teaching. Despite the interdisciplinary nature the field and a historical commitment to investigating fundamental social issues such as democracy, human rights, and social justice, social studies theory and practice tends to be steeped in a reproductive framework, celebrating and sustaining the status quo, encouraging passive acceptance of current social realities and historical constructions, rather than a critical examination of alternatives. These tendencies have been reinforced by education policies such as No Child Left Behind, which have narrowly defined ways of knowing as rooted in empirical science and apolitical forms of comprehension. This book comes at a pivotal moment for radical teaching and for critical pedagogy, bringing the radical debate occurring in social sciences and in activist circles—where global protests have demonstrated the success that radical actions can have in resisting rigid state hierarchies and oppressive regimes worldwide—to social studies education.

Abraham DeLeon , E. Wayne Ross

Critical Theories, Radical Pedagogies, and Social Education: New Perspectives for Social Studies Education begins with the assertion that there are emergent and provocative theories and practices that should be part of the discourse on social studies education in the 21st century. Anarchist, eco-activist, anti-capitalist, and other radical perspectives, such as disability studies and critical race theory, are explored as viable alternatives in responding to current neo-conservative and neo-liberal educational policies shaping social studies curriculum and teaching. Despite the interdisciplinary nature the field and a historical commitment to investigating fundamental social issues such as democracy, human rights, and social justice, social studies theory and practice tends to be steeped in a reproductive framework, celebrating and sustaining the status quo, encouraging passive acceptance of current social realities and historical constructions, rather than a critical examination of alternatives. These tendencies have been reinforced by education policies such as No Child Left Behind, which have narrowly defined ways of knowing as rooted in empirical science and apolitical forms of comprehension. This book comes at a pivotal moment for radical teaching and for critical pedagogy, bringing the radical debate occurring in social sciences and in activist circles—where global protests have demonstrated the success that radical actions can have in resisting rigid state hierarchies and oppressive regimes worldwide—to social studies education. I have attached an excerpt of the book and have included the website for ordering information. Thank you. https://www.sensepublishers.com/product_info.php?products_id=1106&osCsid=62e8008518b023f2866bc1bda9b42e03

Scholar-Practitioner Quarterly

Myriam N Torres

The main objective of this self-study is to reflect and document the development of our own praxis by using teacher research in our teacher education courses. By praxis we mean an ongoing interdependent process in which reflection, including theoretical analysis, enlightens action, and in turn the transformed action changes our understanding of the object of our reflection. Based on the examination of our reflective journals, collegial dialogue, and students' teacher-research reports, we have achieve three major insights: (1) Teacher Research is a vehicle of genuine praxis of teacher education; (2) Praxis involves a dialectical rationality, which is radically different from the conception of practice within an instrumental rational-ity; and (3) Modeling and scaffolding the praxis of teacher research for our master's students-in-service teachers-facilitate both their transformation and ours.

Unpublished manuscript

David W Stinson

CITATION: Stinson, D. W., Bidwell, C. R., Powell, G. C., & Thurman, M. M. (2007). Becoming critical mathematics pedagogues: Three teachers’ beginning journey. Unpublished manuscript, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA. Manuscript presented (summer 2008) at the annual International Conference of Teacher Education and Social Justice, Chicago, IL. Condensed manuscript published: Stinson, D. W., Bidwell, C. R., & Powell, G. C. (2012). Critical pedagogy and teaching mathematics for social justice. The International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 4(1), 76–94. ABSTRACT: In this study, the authors report the transformations in the pedagogical philosophies and practices of three mathematics teachers (middle, high school, and 2-year college) who completed a graduate-level mathematics education course that focused on critical theory and teaching for social justice. The study employed Freirian participatory research methodology; in fact, the participants were not only co-researchers but also co authors of the study. Data collection included reflec-tive essays, journals, and “storytelling”; data analysis was a combination of textual analysis and autoethnography. The findings report that the teachers believed that the course provided not only a new language but also a legitimization to transform their pedagogical philosophies and practices away from the “traditional” and toward a mathematics for social justice.

Simon Campbell

William M Reynolds

The Praeger Handbook …

Thiam-Seng Koh

Shirley R Steinberg , Dike Excel

This paper describes the key notions of situated cognition, Vygotskian thought (zone of proximal development, the general law of cultural development and the mediational nature of signs and tools), and learning from the community of practice perspective. From these notions, we conceptualize principles on learning through which design considerations relevant to the web-based e-learning environments are drawn.

RELATED PAPERS

Scotney Evans

E. Wayne Ross

Juha Suoranta

Shirley R Steinberg

Gary P Hampson

Richard Kahn

International Journal of English Research

Khalil Tawhidyar

Mary Drinkwater

Review of Education, Pedagogy and Cultural Studies

Pedagogy, Culture and Society

Katherine E Entigar

Alexandra Lakind , Amos Margulies

Elizabeth Visedo

Paul R Carr

Journal For Critical Education Policy Studies

arturo rodriguez

Media Theory

Maximillian Alvarez

Clarybell Diaz Vazquez

Sheila Macrine, Ph.D.

Carla Bidwell

Transgressions: Cultural Studies and Education. Vol. 17

Jennifer Gidley

International Critical Childhood Policy Studies Journal

Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies

Maria Cecília Camargo Magalhães , Sueli S Fidalgo

Kevin Magill

Proceedings of the 9th International Conference: Mathematics Education in a Global Community

Daniel Rubin

Journal of the Research Center for Educational …

Jeff Share , Douglas Kellner

ACTES DU SJPD-JPDS PROCEEDINGS, 2018, VOL. 2

Taciana de LiraSilva

Gianna Katsiampoura

João M Paraskeva

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Open access

- Published: 21 May 2024

Health profession education hackathons: a scoping review of current trends and best practices

- Azadeh Rooholamini ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9638-7953 1 &

- Mahla Salajegheh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0651-3467 1

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 554 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

32 Accesses

Metrics details

While the concept of hacking in education has gained traction in recent years, there is still much uncertainty surrounding this approach. As such, this scoping review seeks to provide a detailed overview of the existing literature on hacking in health profession education and to explore what we know (and do not know) about this emerging trend.

This was a scoping review study using specific keywords conducted on 8 databases (PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, ERIC, PsycINFO, Education Source, CINAHL) with no time limitation. To find additional relevant studies, we conducted a forward and backward searching strategy by checking the reference lists and citations of the included articles. Studies reporting the concept and application of hacking in education and those articles published in English were included. Titles, abstracts, and full texts were screened and the data were extracted by 2 authors.

Twenty-two articles were included. The findings are organized into two main categories, including (a) a Description of the interventions and expected outcomes and (b) Aspects of hacking in health profession education.

Hacking in health profession education refers to a positive application that has not been explored before as discovering creative and innovative solutions to enhance teaching and learning. This includes implementing new instructional methods, fostering collaboration, and critical thinking to utilize unconventional approaches.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Health professions education is a vital component of healthcare systems to provide students with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary to provide high-quality care to patients [ 1 ]. However, with the advent of innovative technologies and changing global dynamics, there is a growing need to incorporate new educational methods to prepare medical science students for the future [ 2 ].

Although traditional methods can be effective for certain learning objectives and in specific contexts and may create a stable and predictable learning environment, beneficial for introducing foundational concepts, memorization, and repetition, however, they may not fully address the diverse needs and preferences of today’s learners [ 3 ]. Some of their limitations may be limited engagement, passive learning, lack of personalization, and limited creativity and critical thinking [ 4 ].

As Du et al. (2022) revealed the traditional teaching model fails to capture the complex needs of today’s students who require practical and collaborative learning experiences. Students nowadays crave interactive learning methods that enable them to apply theoretical knowledge in real-world situations [ 5 ].

To achieve innovation in health professions education, engaging students and helping them learn, educators should use diverse and new educational methods [ 6 ]. Leary et al. (2022) described how schools of nursing can integrate innovation into their mission and expressed that education officials must think strategically about the knowledge and skills the next generation of students will need to learn, to build an infrastructure that supports innovation in education, research, and practice, and provide meaningful collaboration with other disciplines to solve challenging problems. Such efforts should be structured and built on a deliberate plan and include curricular innovations, and experiential learning in the classroom, as well as in practice and research [ 7 ].

The incorporation of technology in education is another aspect that cannot be ignored. Technology has revolutionized the way we communicate and learn, providing opportunities for students to access information and resources beyond the traditional education setting. According to the advancement of technology in education, hacking in education is an important concept in this field [ 8 ].

Hack has become an increasingly popular term in recent years, with its roots in the world of computer programming and technology [ 9 ]. However, the term “hack” is not limited solely to the realm of computers and technology. It can also refer to a creative approach to problem-solving, a willingness to challenge established norms, and a desire to find new and innovative ways to accomplish tasks [ 10 ]. At its core, hacking involves exploring and manipulating technology systems to gain a deeper understanding of how they work. This process of experimentation and discovery can be applied to many different fields, including education [ 11 ].

In education, the concept of “hack” has become popular as educators seek innovative ways to engage students and improve learning outcomes. As Wizel (2019) described “hack in education” involves applying hacker mentality and techniques, such as using technology creatively and challenging traditional structures, to promote innovation within the educational system [ 12 ]. These hacking techniques encompass various strategies like gamification, hackathons, creating new tools and resources for education, use of multimedia presentations, online forums, and educational apps for project-based learning [ 9 ]. Butt et al. (2020) demonstrated the effectiveness of hack in education in promoting cross-disciplinary learning in medical education [ 13 ]. However, concerns exist about the negative connotations and ethical implications of hacking in education, with some educators hesitant to embrace these techniques in their classrooms [ 7 , 14 ].

However, while the concept of hack in education has gained traction in recent years, there is still a great deal of uncertainty surrounding its implementation and efficacy. As such, this scoping review seeks to provide a comprehensive overview of the existing literature on hacking in health profession education (HPE), to explore what we know (and do not know) about this emerging trend. To answer this research question, this study provided a comprehensive review of the literature related to hacking in HPE. Specifically, it explored the various ways in which educators are using hack techniques to improve learning outcomes, increase student engagement, and promote creativity in the classroom.

Methods and materials

This scoping review was performed based on the Arksey and O’Malley Framework [ 15 ] and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement to answer some questions about the hacking approach in health professions education [ 16 ].

Search strategies

The research question was “What are the aspects of hacking in education?“. We used the PCC framework which is commonly used in scoping reviews to develop the research question [ 17 ]. In such a way the Population assumed as learners, the Concept supposed as aspects of hacking in education, and the Context is considered to be the health profession education.

A systematic literature search was conducted on June 2023, using the following terms and their combinations: hack OR hacking OR hackathon AND education, professional OR “medical education” OR “medical training” OR “nursing education” OR “dental education” OR “pharmacy education” OR “health professions education” OR “health professional education” OR “higher education” OR “healthcare education” OR “health care education” OR “students, health occupations” OR “medical student” OR “nursing student” OR “dental student” OR “pharmacy student” OR “schools, health occupations” OR “medical school” OR “nursing school” OR “dental school” OR “pharmacy school”) in 8 databases (PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, ERIC, PsycINFO, Education Source, CINAHL) with no time limitation. (A copy of the search strategy is included in Appendix 1 ). To find additional relevant studies, we conducted a forward and backward searching strategy by checking the reference lists and citations of the included articles.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Original research reporting the different aspects of hacking in health professions education and published in English was included. We excluded commentaries, editorials, opinion pieces, perspectives, reviews, calls for change, needs assessments, and other studies in which no real interventions had been employed.

Study identification

After removing the duplicates, each study potentially meeting the inclusion criteria was independently screened by 2 authors (A.R. and M.S.). Then, the full texts of relevant papers were assessed independently by the 2 authors for relevance and inclusion. Disagreements at either step were resolved when needed until a consensus was reached.

Quality assessment of the studies

We used the BEME checklist [ 18 ], consisting of 11 indicators, to assess the quality of studies. Each indicator was rated as “met,” “unmet,” or “unclear.” To be deemed of high quality, articles should meet at least 7 indicators. The quality of the full text of potentially relevant studies was assessed by 2 authors (A.R. and M.S.). Disagreements were resolved through discussion. No study was removed based on the results of the quality assessment.

Data extraction and synthesis

To extract the data from the studies, a data extraction form was designed based on the results of the entered studies. A narrative synthesis was applied as a method for comparing, contrasting, synthesizing, and interpreting the results of the selected papers. All outcomes relevant to the review question were reported. The two authors reviewed and coded each included study using the data extraction form independently.

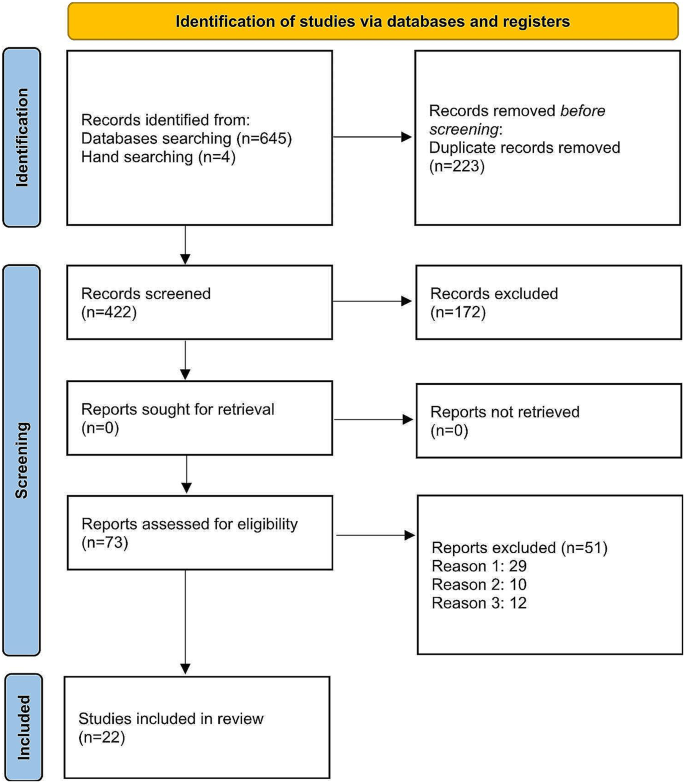

A total of 645 titles were found, with a further four titles identified through the hand-searching of reference lists of all reviewed articles. After removing the duplicate references, 422 references remained. After title screening, 250 studies were considered for abstract screening, and 172 studies were excluded. After the abstract screening, 73 studies were considered for full-text screening, and 177 studies were excluded due to reasons such as:1. being irrelevant, 2. loss of data, and 3. language limitation. 22 studies were included in the final analysis. The 2020 PRISMA diagram for the included studies is shown in Fig. 1 . The quality was evaluated as “high” in 12 studies, “moderate” in 7 studies, and “low” in 3 studies.

PRISMA flow diagram for included studies

The review findings are organized into two main categories: (a) Description of the interventions and expected outcomes and (b) Aspects of hacking in health profession education.

Description of the interventions and expected outcomes

The description of the studies included the geographical context of the interventions, type, and number of participants, focus of the intervention, evaluation methodology, and outcomes. Table 1 displays a summary of these features.

Geographical context

Of the 22 papers reviewed, 11 studies (45.4%) took place in the United States of America [ 7 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ], two studies in Pakistan [ 13 , 29 ], one study performed in international locations [ 30 ], and the remainder being in the United Kingdom [ 31 ], Germany [ 32 ], Finland [ 33 ], Australia [ 34 ], Austria [ 35 ], Thailand [ 36 ], Africa [ 37 ], and Canada [ 38 ].

Type and number of participants

Hacking in HPE interventions covered a wide range and multiple audiences. The majority of interventions targeted students (17 studies, 77.2%) [ 7 , 13 , 20 , 21 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 36 , 37 , 38 ]. Their field of education was reported differently including medicine, nursing, engineering, design, business, kinesiology, and computer sciences. Also, they were undergraduates, postgraduates, residents, and post-docs. Ten interventions (45.4%) were designed for physicians [ 13 , 19 , 21 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 28 , 29 , 33 , 35 ]. Their field of practice was reported diverse including psychology, radiology, surgery, and in some cases not specified. Eight (36.3%) studies focused on staff which included healthcare staff, employees of the university, nurses, care experts, and public health specialists [ 13 , 22 , 26 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 32 , 35 ]. Interestingly, nine of the hacking in HPE interventions (40.9%) welcomed specialists from other fields outside of health sciences and medicine [ 13 , 19 , 22 , 25 , 26 , 28 , 29 , 33 , 35 ]. Their field of practice was very diverse including engineers, theologians, artists, entrepreneurs, designers, informaticists, IT professionals, business professionals, industry members, data scientists, and user interface designers. The next group of participants was faculty with 5 studies (22.7%) [ 7 , 23 , 32 , 34 , 36 ]. An intervention (4.5%) targeted the researchers [ 27 ]. The number of participants in the interventions ranged from 12 to 396. Three studies did not specify the number of their participants.

The focus of the intervention

The half of interventions aimed to improve HPE (12 studies, 54.5%) [ 7 , 13 , 21 , 23 , 24 , 26 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 34 , 38 ], with a secondary emphasis on enhancing clinical or health care [ 19 , 22 , 25 , 29 , 33 , 35 , 36 , 37 ]. Two studies highlighted the improvement in entrepreneurship skills of health professions [ 19 , 20 ]. One study aimed to improve the research skills of health professionals [ 27 ].

Evaluation methodology

Methods to evaluate hacking in HPE interventions included end-of-program questionnaires, pre-and post-test measures to assess attitudinal or cognitive change, self-assessment of post-training performance, project-based assessment through expert judgment and feedback, interviews with participants, and direct observations of behavior.

Hacking in HPE interventions has resulted in positive outcomes for participants. Five studies found high levels of satisfaction for participants with the intervention [ 21 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 37 ]. Some studies evaluated learning, which included changes in attitudes, knowledge, and skills. In most studies, participants demonstrated a gain in knowledge regarding awareness of education’s strengths and problems, in the desire to improve education by enhancement of awareness for technological possibilities [ 7 , 13 , 19 , 21 , 23 , 30 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 38 ]. Some studies found improving participant familiarity with healthcare innovation [ 19 , 22 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 33 , 36 , 37 ]. Some participants reported a positive change in attitudes towards HPE as a result of their involvement in hacking interventions. They cited a greater awareness of personal strengths and limitations, increased motivation, more confidence, and a notable appreciation of the benefits of professional development [ 20 , 21 , 29 , 34 ]. Some studies also demonstrated behavioral change. In one study, changes were noted in developing a successful proof-of-concept of a radiology training module with elements of gamification, enhancement engagement, and learning outcomes in radiology training [ 28 ]. In a study, participants reported building relationships when working with other members which may be students, faculty, or healthcare professionals [ 7 ]. Five studies found a high impact on participant perceptions and attitudes toward interdisciplinary collaboration [ 22 , 26 , 27 , 36 , 38 ].

Aspects of hacking in health profession education

The special insights of hacking in HPE included the adaptations considered in the interventions, the challenges of interventions, the suggestions for future interventions, and Lessons learned.

Adaptations

The adaptations are considered to improve the efficacy of hacking in HPE interventions. We found that 21 interventions were described as hackathons. Out of this number, some were only hackathons, and some others had benefited from hackathons besides other implications of hacking in education. Therefore, most of the details in this part of the findings are presented with a focus on hackathons. The hackathon concept has been limited to the industry and has not been existing much in education [ 39 , 40 ]. In the context of healthcare, hackathons are events exposing healthcare professionals to innovative methodologies while working with interdisciplinary teams to co-create solutions to the problems they see in their practice [ 19 , 22 , 24 , 25 , 30 , 41 , 42 ].

Some hackathons used various technologies for internal and external interactions during the hackathon including Zoom, Gmail, WhatsApp, Google Meet, etc [ 37 ]. . . Almost all hackathons were planned and performed in the following steps including team formation, team working around the challenges, finding innovative solutions collaboratively, presenting the solutions and being evaluating based on some criteria including whether they work, are good ideas with a suitable problem/solution fit, how a well-designed experience and execution, etc. For example, in the hackathon conducted by Pathanasethpong et al. (2017), the judging criteria included innovativeness, feasibility, and value of the projects [ 36 ]. Also, they managed the cultural differences between the participants through strong support of leadership, commitment, flexibility, respect for culture, and willingness to understand each other’s needs [ 36 ].

Despite valuable adaptations, several challenges were reported. The hackathons faced some challenges such as limited internet connectivity, time limitations, limited study sample, power supply, associated costs, lack of diversity among participants, start-up culture, and lack of organizational support [ 13 , 19 , 25 , 28 , 30 , 34 , 37 ]. Some interventions reported the duration of the hackathon was deemed too short to develop comprehensive solutions [ 37 ]. One study identified that encouraging experienced physicians and other healthcare experts to participate in healthcare hackathons is an important challenge [ 26 ].

Suggestions for the future

Future hackathons should provide internet support for participants and judges, invite investors and philanthropists to provide seed funding for winning teams, and enable equal engagement of all participants to foster interdisciplinary collaboration [ 37 ]. Subsequent hackathons have to evaluate the effect of implementation or durability of the new knowledge in practice [ 19 , 28 ]. Wang et al. (2018) performed a hackathon to bring together interdisciplinary teams of students and professionals to collaborate, brainstorm, and build solutions to unmet clinical needs. They suggested that future healthcare hackathon organizers a balanced distribution of participants and mentors, publicize the event to diverse clinical specialties, provide monetary prizes and investor networking opportunities for post-hackathon development, and establish a formal vetting process for submitted needs that incorporates faculty review and well-defined evaluation criteria [ 22 ]. Most interventions had an overreliance on self-assessments to assess their effectiveness. To move forward, we should consider the use of novel assessment methods [ 30 ].

Lessons learned

Based on the findings of hackathons, they have developed efficient solutions to different problems related to public health and medical education. Some of these solutions included developing novel computer algorithms, designing and building model imaging devices, designing more approachable online patient user websites, developing initial prototypes, developing or optimizing data analysis tools, and creating a mobile app to optimize hospital logistics [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 36 ]. Staziaki et al. (2022) performed an intervention to develop a radiology curriculum. Their strategies were creating new tools and resources, gamification, and conducting a hackathon with colleagues from five different countries. They revealed a radiology training module that utilized gamification elements, including experience points and a leaderboard, for annotation of chest radiographs of patients with tuberculosis [ 28 ].

Most hackathons provide an opportunity for medical health professionals to inter-professional and inter-university collaboration and use technology to produce innovative solutions to public health and medical education [ 7 , 23 , 26 , 30 , 37 , 38 ]. For example, one study discussed that hackathons allowed industry experts and mentors to connect with students [ 37 ]. In the study by Mosene et al. (2023), results offer an insight into the possibilities of hackathons as a teaching/learning event for educational development and thus can be used for large-scale-assessments and qualitative interviews for motivational aspects to participate in hackathons, development of social skills and impact on job orientation [ 32 ].