Life-Cycle Hypothesis

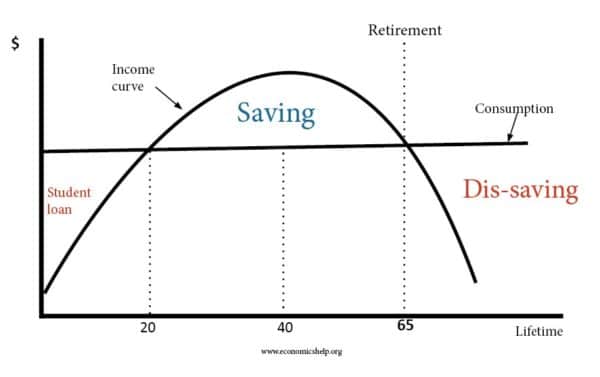

Definition: The Life-cycle hypothesis was developed by Franco Modigliani in 1957. The theory states that individuals seek to smooth consumption over the course of a lifetime – borrowing in times of low-income and saving during periods of high income.

- As a student, it is rational to borrow to fund education.

- Then during your working life, you pay off student loans and begin saving for your retirement.

- This saving during working life enables you to maintain similar levels of income during your retirement.

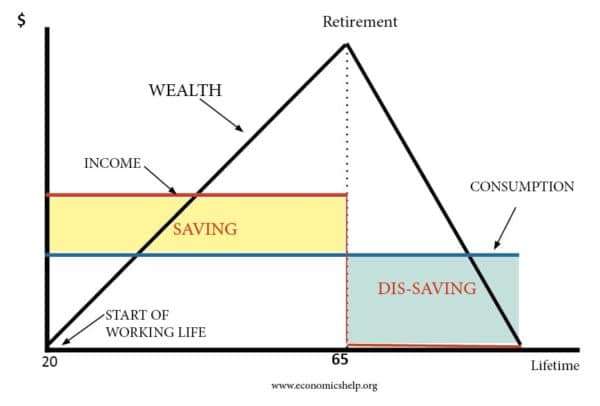

It suggests wealth will build up in working age, but then fall in retirement.

Wealth in the Life-Cycle Hypothesis

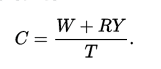

The theory states consumption will be a function of wealth, expected lifetime earnings and the number of years until retirement.

Consumption will depend on

- C= consumption

- R = Years until retirement. Remaining years of work

- T= Remaining years of life

It suggests for the whole economy consumption will be a function of both wealth and income.

Prior to life-cycle theories, it was assumed that consumption was a function of income. For example, the Keynesian consumption function saw a more direct link between income and spending.

However, this failed to account for how consumption may vary depending on the position in life-cycle.

Motivation for life-cycle consumption patterns

- Diminishing marginal utility of income. If income is high during working life, there is a diminishing marginal utility of spending extra money at that particular time.

- Harder to work and earn money, in old age. Life Cycle enables people to work hard and spend less.

Does the Life-cycle theory happen in reality?

Mervyn King suggests life-cycle consumption patterns can be found in approx 75% of the population. However, 20-25% don’t plan in the long term. (NBER paper on economics of saving )

Reasons for why people don’t smooth consumption over a lifetime.

- Present focus bias – People can find it hard to value income a long time in the future

- Inertia and status quo bias . Planning for retirement requires effort, forward thinking and knowledge of financial instruments such as pensions. People may prefer to procrastinate – even though they know they should save more – and so saving gets put off.

Criticisms of Life Cycle Theory

- It assumes people run down wealth in old age, but often this doesn’t happen as people would like to pass on inherited wealth to children. Also, there can be an attachment to wealth and an unwillingness to run it down. See: Prospect theory and the endowment effect.

- It assumes people are rational and forward planning. Behavioural economics suggests many people have motivations to avoid planning.

- People may lack the self-control to reduce spending now and save more for future.

- Life-cycle is easier for people on high incomes. They are more likely to have financial knowledge, also they have the ‘luxury’ of being able to save. People on low-incomes, with high credit card debts, may feel there is no disposable income to save.

- Leisure. Rather than smoothing out consumption, individuals may prefer to smooth out leisure – working fewer hours during working age, and continuing to work part-time in retirement.

- Government means-tested benefits for old-age people may provide an incentive not to save because lower savings will lead to more social security payments.

Other theories

- Permanent income hypothesis of Milton Friedman – This states people only spend more when they see it as an increase in permanent income.

- Ricardian Equivalence – consumers may see tax cuts as only a temporary rise in income so will not alter spending.

- Autonomous consumption – In Keynesian consumption function, the level of consumption that is independent of income.

- Marginal propensity to consume – how much of extra income is spent.

15 thoughts on “Life-Cycle Hypothesis”

Thanks for the reminder of the theory… Am a moi university Economic student in Nairobi Kenya.

Thanks for the most summarised note ever. it will help me with presentation. Gulu university. JALON

prof premraj pushpakaran writes — 2018 marks the 100th birth year of Franco Modigliani!!!

Thanks for the analysis on the hypothesis

Nice piece of work for economist. Been applicable in my presentation at Kyambogo university Uganda

This piece of paper is very important as far as consumption is concerned…

This piece is the best I have seen so far, this is a great work

Thanks for this work.it Will help me in my presentation at metropolitan international University

Very coincise and well articulated. This work reconnects me with themechanics of consumption theories. I appreaciate for a job well done.

Very nice and comprensive information. It will help me in my exams at university of jos Nigeria, studying economics

thank u for the summarized notes,it will help me in my exam at Kibabii university

Great job. Thanks for this masterpiece.

Good job. Thanks for this masterpiece. It reconnects me with the consumption theories.

A good summarised piece of work on life cycle hypothesis, it will help me in my group presentation. Kenyatta University economics student.

Comments are closed.

Quickonomics

Life-Cycle Hypothesis (Lch)

Definition of life-cycle hypothesis (lch).

The Life-Cycle Hypothesis (LCH) is an economic theory that suggests individuals base their consumption and savings decisions on their expected lifetime income rather than their current income. According to the LCH, individuals strive to maintain a stable standard of living throughout their lifetime by adjusting their savings and consumption patterns. This hypothesis takes into account the different stages of life, such as education, working years, and retirement, and assumes individuals plan and save accordingly for these stages.

To illustrate the Life-Cycle Hypothesis, let’s consider two individuals: Alan, a young professional just starting his career, and Sarah, a retiree. Alan expects his income to increase significantly over time as he gains experience and advances in his profession. To maintain a stable standard of living, he saves a portion of his income during his early working years, which allows him to enjoy a more comfortable retirement.

On the other hand, Sarah has already retired and relies on savings and pensions for her income. Since she is no longer earning a salary, her consumption decreases to meet her reduced income. She draws from her accumulated savings to support her lifestyle in retirement.

Throughout their lives, both Alan and Sarah make consumption and savings decisions based on their expected lifetime income, adjusting their behavior accordingly.

Why the Life-Cycle Hypothesis Matters

The Life-Cycle Hypothesis provides a framework for understanding individuals’ consumption and savings patterns over their lifetimes. It emphasizes the importance of long-term financial planning and highlights the trade-off between current consumption and saving for the future.

Understanding the Life-Cycle Hypothesis is useful for policymakers, financial planners, and individuals themselves. Policymakers can design policies and programs that support retirement savings and encourage long-term financial stability. Financial planners can help individuals develop strategies to achieve their desired lifestyles in retirement. Lastly, individuals can benefit from understanding their own consumption patterns and making informed decisions about savings and retirement planning.

To provide the best experiences, we and our partners use technologies like cookies to store and/or access device information. Consenting to these technologies will allow us and our partners to process personal data such as browsing behavior or unique IDs on this site and show (non-) personalized ads. Not consenting or withdrawing consent, may adversely affect certain features and functions.

Click below to consent to the above or make granular choices. Your choices will be applied to this site only. You can change your settings at any time, including withdrawing your consent, by using the toggles on the Cookie Policy, or by clicking on the manage consent button at the bottom of the screen.

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- Financial Planning

What Is the Life-Cycle Hypothesis?

The Life-Cycle Hypothesis Explained

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_0031-a6116af31d5a4783a969390cd325367c.jpg)

Definition and Examples of the Life-Cycle Hypothesis

How the life-cycle hypothesis works, criticisms of the life-cycle hypothesis, life-cycle hypothesis theory vs. permanent income hypothesis theory.

Ridofranz / Getty Images

The life-cycle hypothesis (LCH) is an economic theory that suggests that individuals have a tendency to maintain the same level of spending over time. They achieve this goal by borrowing in when they're younger and their income is low, saving during their middle years when income is high, and living off their assets in their older years when income is low again.

Here’s a closer look at how the LCH works and why it’s important.

The LCH states that households save and spend their wealth in an effort to keep their consumption level steady over time. Even though wealth and income may vary over your lifetime, the theory states, your spending habits stay relatively the same.

- Acronym: LCH

- Alternate name: Life-cycle model

Saving for retirement is a good example of the LCH in action. You know your income may disappear when you’re older, so you save money during your working years to afford the same lifestyle later on.

The LCH predicts that, in general, you maintain the same level of consumption throughout your lifetime by:

- Borrowing money when you’re young (either by borrowing money or liquidating assets you already own)

- Saving more money when you’re middle aged and at the peak of your career

- Living off the wealth you’ve accumulated when you’re old and retired

Franco Modigliani published the life-cycle hypothesis theory in 1954 with Richard Brumberg and later won a Nobel Prize for his economic analyses.

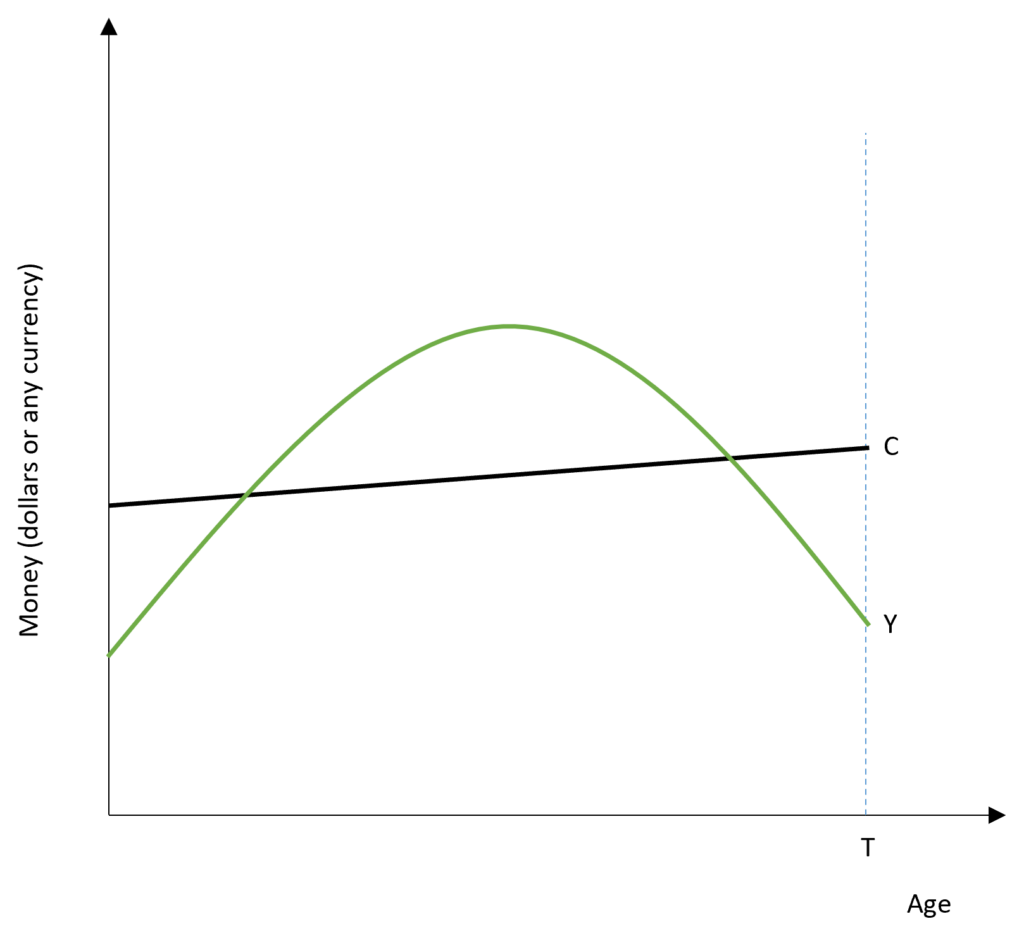

The LCH predicts that your savings habits follow a hump-shaped pattern as in the diagram below where your savings rate is low during your younger and older years and peaks during your middle years:

For example, suppose you make $20,000 this year, but you expect your income will increase to $80,000 next year because you’ve got a job lined up after you graduate from college.

According to the LCH, you may spend money today with your future income in mind, which may lead you to borrow money. As you reach the peak of your career, you’ll pay off any debt you accumulated and ramp up your savings. Then, you’ll draw down that savings in retirement so you can continue your same level of spending.

The LCH has withstood the test of time but it’s not without its flaws:

LCH Doesn’t Account for Financial Windfalls

Traditional LCH models don’t apply to individuals who run into financial windfalls or have sporadic income throughout their lives.

Take NFL players, for example. The LCH would imply that NFL players save considerable amounts of money while they’re at the peak of their careers so they can sustain the same level of consumption when they retire.

But the reality is that some NFL athletes go from enormously wealthy to near poverty shortly after the end of their careers. A 2015 National Bureau of Economic Research study that focused on LCH and the NFL predicted that an NFL player has a 15% to 40% chance of going bankrupt 25 years after they retire.

The study said the high bankruptcy rates may be due to the fact that players:

- Think their career will last longer than it typically does

- Make poor financial decisions with the money they receive

- Have social pressures to spend more than they should

LCH Assumes Your Consumption Level Will Stay the Same

The LCH predicts that you’ll maintain roughly your same level of spending by borrowing money when income is low and saving when income is high. But this isn’t always realistic.

For example, younger workers may not have access to the credit needed to fund their ideal level of spending now. So, naturally, their consumption habits would change as their income increased and those options became available to them.

Likewise, a family with parents in their 30s with three young kids, student loan debt, and a mortgage may consume more now than they will in their 70s when they’re retired, possibly debt-free, and no longer have dependents to care for.

Both the LCH theory and the permanent income hypothesis (PIH) theory seek to understand how individuals spend and save money. The main difference is that the LCH is based on a finite timeline where a person saves only enough to sustain their spending habits during their lifetime. The PIH, on the other hand, is based on an infinite timeline where a person saves enough for both themselves and their heirs.

Key Takeaways

- The life-cycle hypothesis (LCH) is an economic theory that describes how an individual maintains roughly the same level of consumption over time by saving when their income is high and borrowing when income is low.

- The LCH predicts that wealth accumulation follows a hump-shaped curve where you have a low savings rate when you’re young, a high rate when you’re middle-aged, and a low rate again when you’re old.

- Some experts criticize the LCH because consumption doesn’t always stay consistent over time. For example, a middle-aged worker with three kids and a mortgage probably consumes more than they will when they’re retired with no debt or dependents.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology. " The Collected Papers of Franco Modigliani, Volume 6 ."

Federal Reserve Board. " A Primer on the Economics and Time Series Econometrics of Wealth Effects ," Page 8.

Carnegie Mellon University. " The Life Cycle Theory of Consumption ," Page 340.

National Bureau of Economic Research. " Bankruptcy Rates Among NFL Players With Short-Lived Income Spikes ," Page 8.

Centre for Economic Studies and Finance. " Working Paper No. 140: The Life-Cycle Hypothesis, Fiscal Policy,and Social Security ," Page 7.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/WhatIsaBudget-e91a800ea0fe4f1e85efd025333985ef.jpeg)

Life-cycle hypothesis: Ando and Modigliani

- Post author: Viren Rehal

- Post published: August 18, 2022

- Post category: Consumption function / Macroeconomics

- Post comments: 0 Comments

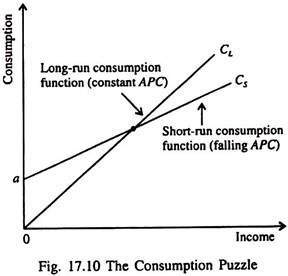

The life-cycle hypothesis was postulated by Ando and Modigliani in an attempt to explain the behaviour of consumption function in the long and short run. According to this theory, current consumption decisions are based on future expected income over an individual’s lifetime. The major advantage of this theory is that Ando and Modigliani incorporated the role of assets in determining consumption decisions. Other theories don’t incorporate assets into consumption ( absolute income hypothesis ) or the role of assets is only implicit ( permanent income hypothesis ).

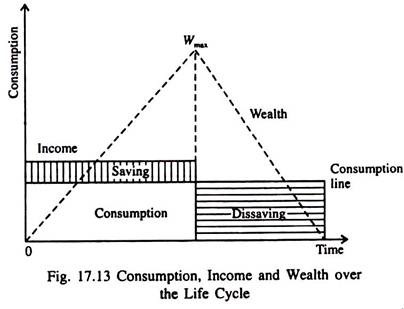

MPC < APC in cross-sections

Over the lifetime of any individual, income is low in the early years of life. As people reach middle age, their income rises as they start earning more. In later years of life, however, income starts falling again to reach low levels owing to retirement or the inability to work as people grow older. Therefore, income starts from a low level, keeps increasing in middle age, and declines back to a low level in old age.

In the case of consumption, individuals are expected to maintain a constant or slightly increasing level of consumption as they keep growing older. Since consumption is dependent on future expected income, the present value of consumption is constrained by the present value of income.

APC and MPS at different age

During the early years, income is low as compared to consumption and individuals are borrowers during this period, i.e. APC is high. However, they expect their future income to rise during their middle age. Because income is higher than consumption level, they pay off their borrowings during this period and save for retirement in old age. With high income, APC is low because consumption is much lower as compared to income in this period. In the later years of the life-cycle, income is again below consumption level. Hence, this is a period of dissavings or negative savings by individuals, leading to a low APC.

Therefore, across different sections based on income levels, APC will be high for low-income groups. These low-income groups primarily include people in their early years of life and people in old age, who have low incomes. On average, APC will be high as the low-income group consists of higher than average young and older people. On the contrary, high-income groups will have a higher than average proportion of middle-aged people. This is because they have higher incomes. APC, in this case, will be lower because consumption is low compared to income level during middle age.

Hence, APC will decline as income increases and MPC<APC in cross sections because of different income levels in a life-cycle.

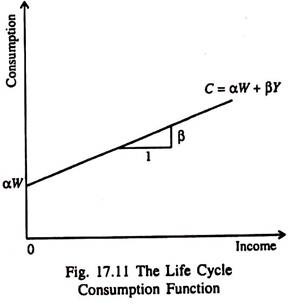

consumption function of Life-Cycle Hypothesis

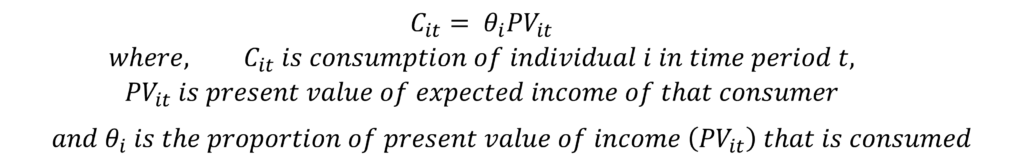

According to the life-cycle hypothesis, the consumption of any individual is based on expected income in the future. If the expected income rises, the consumption of that consumer will also increase. Ando and Modigliani use the Present Value criterion to represent expected income in the future. Therefore, the consumption of an individual can be expressed as follows:

If the present value of expected income increases, then consumption of that consumer will increase by a given proportion ( theta ) of that increase in income.

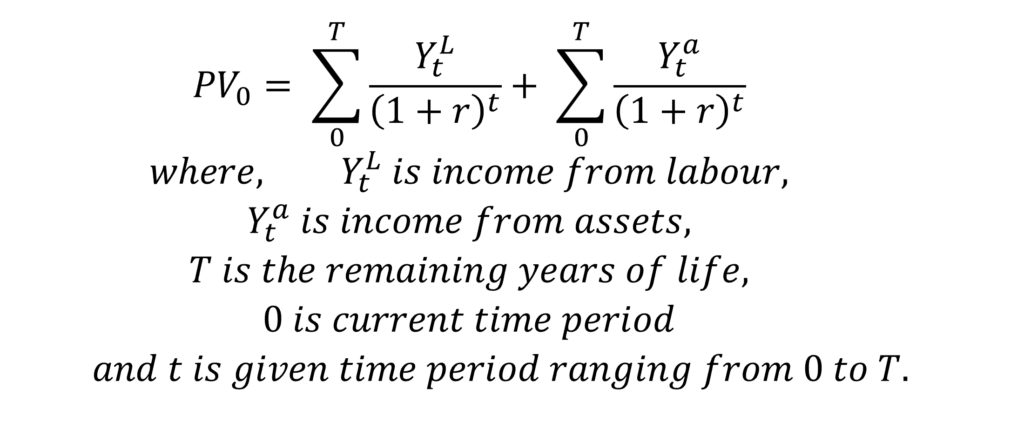

If the income distribution and age of the population are stable along with the constant taste and preferences of consumers, then the aggregate consumption function can simply be obtained by summation of all individual consumption functions.

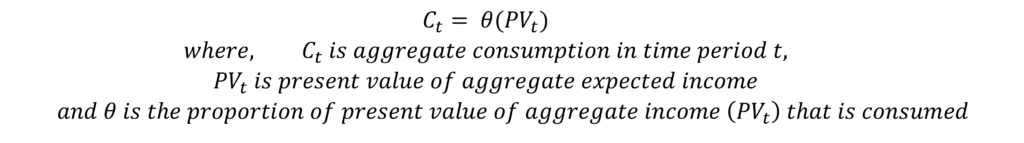

Present Value of expected future income

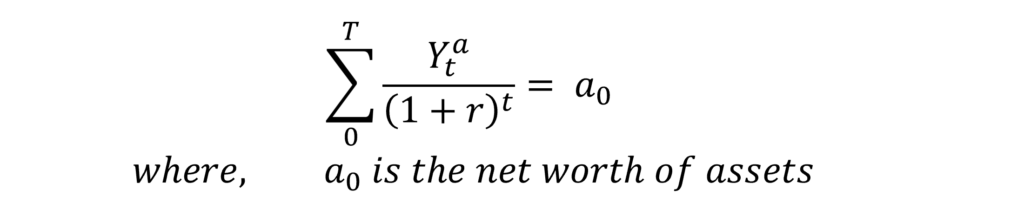

Future income is unknown and cannot be measured directly. Therefore, the present value of expected income has to be estimated indirectly. Ando and Modigliani divided income into two types- income labour and income from assets, and estimated the present value variable as follows:

In an efficient capital market, we can assume that the present value of income from assets is equal to the value of assets in the current time period. Therefore, we can substitute the second element of the equation as:

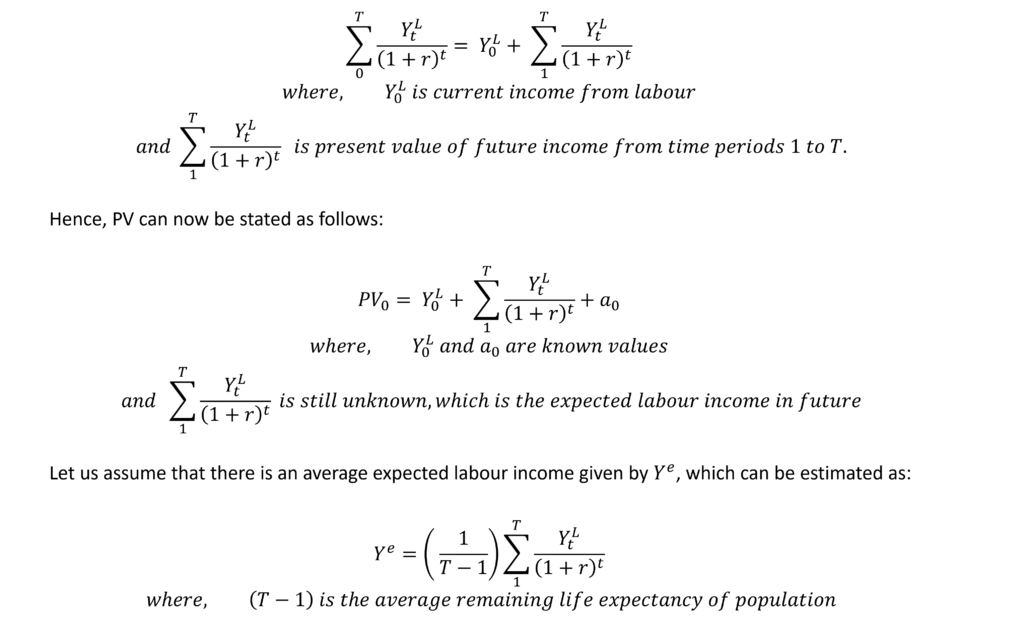

In the case of the first element of income from labour, we know the labour income in the current period and can therefore separate current income from the present value of expected income.

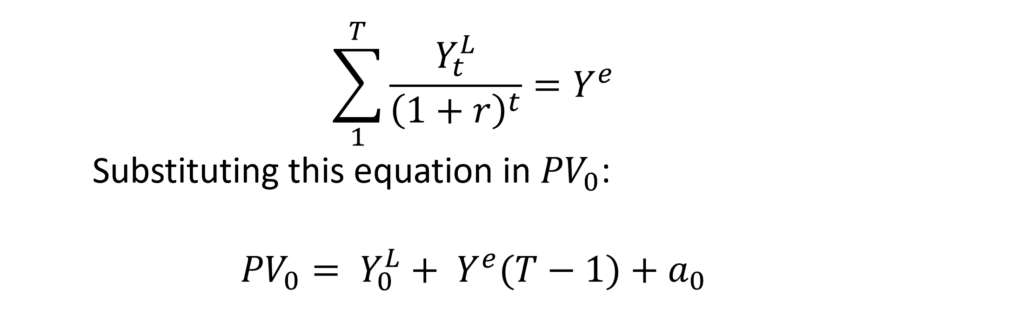

Therefore, the above equation simply divides the expected future labour income by the average life remaining of the population in years to estimate an average expected labour income. From this equation, we have:

In this equation, Y e is the only unknown which is an estimate of average expected labour income.

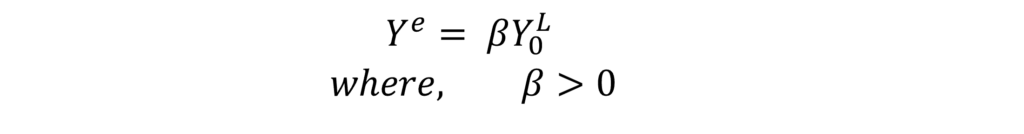

Ando and Modigliani found that assuming this average expected labour income as a function of current labour income worked well and they stated this as:

This implies that if current income increases, people expect average future income to rise as well. The amount of this rise is determined by the proportion coefficient (beta), such that an increase in average expected income is a proportion of current labour income.

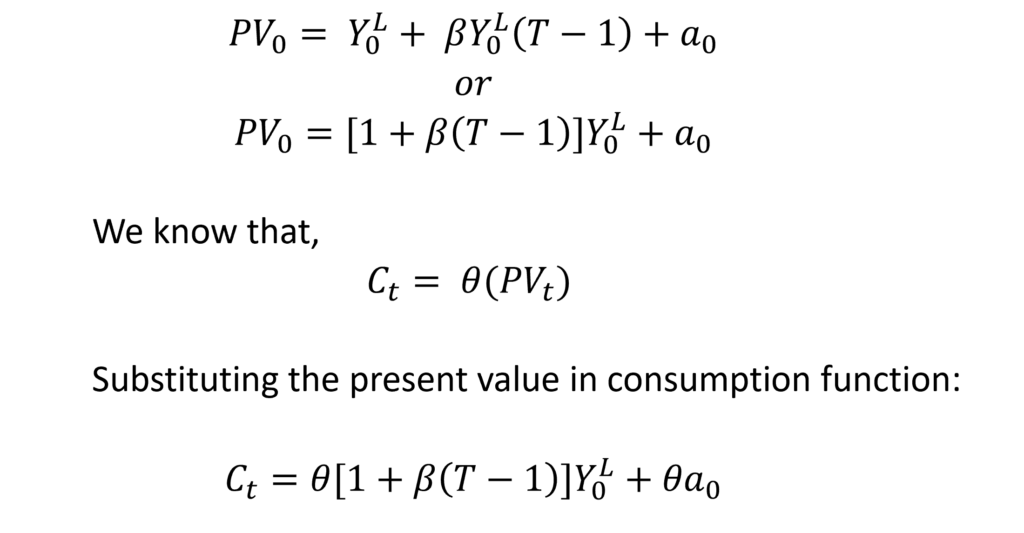

Hence, we can modify the PV 0 equation and the consumption function as follows:

This equation represents the consumption function associated with the life-cycle hypothesis. Every variable in this equation can be measured which allows empirical estimation of the consumption function.

cyclical fluctuation and long-run consumption: empirical results

The consumption function put forward by Ando and Modigliani can be used to carry out empirical analysis to understand the behaviour of consumption in the long run and the effect of business cycles on consumption.

Ando and Modigliani applied this consumption function to annual data of the United States. They obtained the following results:

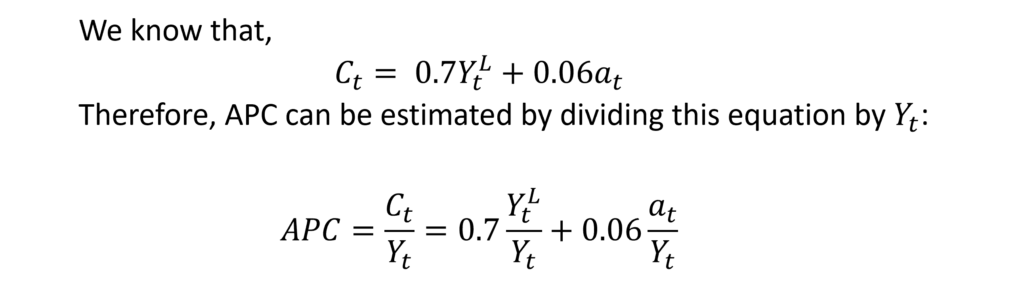

The marginal propensity to consume from labour income is 0.7. This means that a $1 increase in labour income will lead to a $0.7 increase in consumption. Similarly, the marginal propensity to consume from assets is 0.06 implying that a $1 increase in assets (net worth of assets) will lead to a $0.06 increase in consumption.

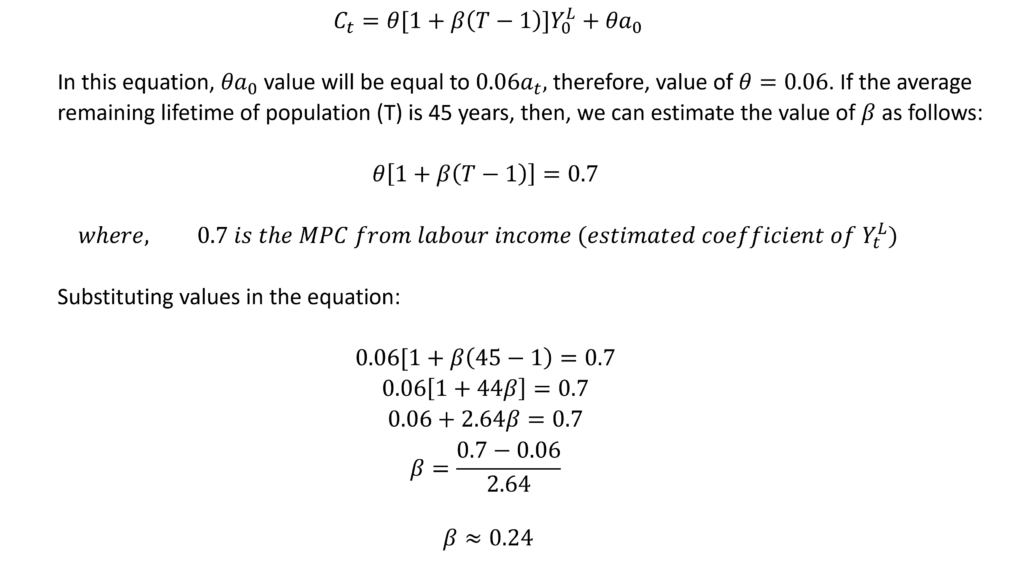

Let us apply these results to the life cycle consumption function:

Positive coefficient beta suggests that with an increase in current labour income, the average expected labour income increases. As current labour income increases by $1, the average expected labour income increases by $0.25.

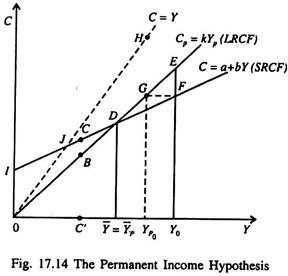

MPC and APC

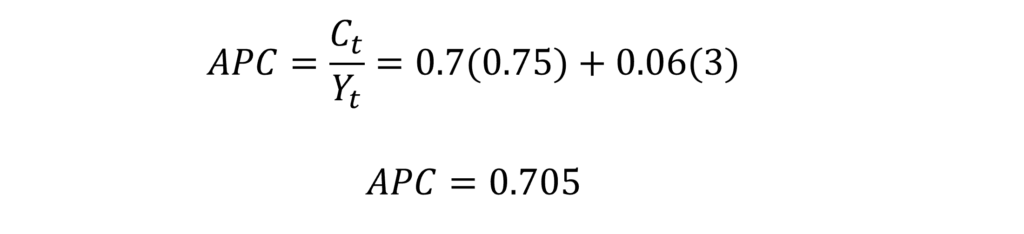

This estimated consumption function has a slope of 0.7 or MPC, corresponding to the coefficient of Y t L . The intercept of the consumption function is equal to 0.06a t because assets remain the same in the short run. As seen in the figure, APC is falling with a rise in labour income and MPC<APC in the short run consumption function.

In the long run, however, assets will not be constant. With an increase in assets, the short-run consumption functions will keep shifting upwards as the economy grows. Therefore, long-run consumption will be along the trend where APC is constant and APC=MPC along this long-run consumption.

The APC will be constant if the share of labour income in total income ( Y t L / Y t ) and the ratio of total assets to total income (at / Yt) remain constant in the long run as the economy grows along the trend. Ando and Modigliani observed that both these ratios remained fairly constant in the long run in the annual U.S. data. The labour share in income was around 75 per cent and the ratio of assets to income was around 3. Therefore, the estimated APC is:

criticism of Life-cycle Hypothesis

- The life cycle hypothesis assumes that everyone is a rational consumer aiming to maximize utility based on expected income. However, this may not be necessarily true because not everyone’s consumption decisions are based on future income. Some individuals may not even consider future outcomes while spending in the current period. Or they may be impulsive and lacking in self-control. And, they do not focus on having a smooth consumption over a long period.

- The life-cycle hypothesis assumes that every increase in current income leads to an increase in average future expected income. This may not be true in every case because every income change will not necessarily affect expected future income. For instance, a temporary tax that changes current income, but, consumers are aware that it is temporary and they will not change their expected future income.

Nevertheless, life-cycle theory explains consumer behaviour across cross sections, short run as well as long run. Additionally, it takes into account the role of wealth or assets in determining consumption and can be empirically tested.

You Might Also Like

Relative income hypothesis, absolute income hypothesis, difference between microeconomics and macroeconomics, leave a reply cancel reply.

To provide the best experiences, we and our partners use technologies like cookies to store and/or access device information. Consenting to these technologies will allow us and our partners to process personal data such as browsing behavior or unique IDs on this site and show (non-) personalized ads. Not consenting or withdrawing consent, may adversely affect certain features and functions.

Click below to consent to the above or make granular choices. Your choices will be applied to this site only. You can change your settings at any time, including withdrawing your consent, by using the toggles on the Cookie Policy, or by clicking on the manage consent button at the bottom of the screen.

Open Access is an initiative that aims to make scientific research freely available to all. To date our community has made over 100 million downloads. It’s based on principles of collaboration, unobstructed discovery, and, most importantly, scientific progression. As PhD students, we found it difficult to access the research we needed, so we decided to create a new Open Access publisher that levels the playing field for scientists across the world. How? By making research easy to access, and puts the academic needs of the researchers before the business interests of publishers.

We are a community of more than 103,000 authors and editors from 3,291 institutions spanning 160 countries, including Nobel Prize winners and some of the world’s most-cited researchers. Publishing on IntechOpen allows authors to earn citations and find new collaborators, meaning more people see your work not only from your own field of study, but from other related fields too.

Brief introduction to this section that descibes Open Access especially from an IntechOpen perspective

Want to get in touch? Contact our London head office or media team here

Our team is growing all the time, so we’re always on the lookout for smart people who want to help us reshape the world of scientific publishing.

Home > Books > Macroeconomic Analysis for Economic Growth

The Life Cycle Hypothesis and Uncertainty: Analyzing Aging Savings Relationship in Tunisia

Submitted: 13 August 2021 Reviewed: 15 September 2021 Published: 03 January 2022

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.100459

Cite this chapter

There are two ways to cite this chapter:

From the Edited Volume

Macroeconomic Analysis for Economic Growth

Edited by Musa Jega Ibrahim

To purchase hard copies of this book, please contact the representative in India: CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. www.cbspd.com | [email protected]

Chapter metrics overview

503 Chapter Downloads

Impact of this chapter

Total Chapter Downloads on intechopen.com

Total Chapter Views on intechopen.com

This research empirically checks the effect of uncertainty on aging-saving link that is indirectly captured by an auxiliary variable: the unemployment. It looks at the nexus population aging and savings by bringing out the unemployment context importance in determination saving behavior notably in a setting of unavailability of unemployment allowance. To better estimate population aging, it considers the old-age dependency ratio besides the total dependency one, which is the usually indicator used. Applying the Structural VAR model, the variance decomposition technique and the response impulse function, on Tunisia during 1970–2019, it puts on show that elderly do not dissave in a context of enduring unemployment and unavailability of unemployment allowance. Unemployment is an important factor able to shaping the saving behavior and to distort the life cycle hypothesis’s prediction. Consequently, the life cycle hypothesis cannot be validated under uncertainty. Hence, aging does not to alter savings systematically. The nature of aging-saving relationship is upon to social and economic context.

- Unemployment

- life cycle hypothesis

Author Information

Olfa frini *.

- ISCAE, University of Manouba, Tunisia

- ECSTRA Lab, Carthage University, Tunisia

*Address all correspondence to: [email protected]

1. Introduction

There is a great concern about the increase of elderly proportion follow-up the aging population process over the world. It is likely to create important macroeconomic issues and involve new policies challenges as it will put downward pressure on saving according to the life cycle hypothesis (LCH) prediction formulated by Modigliani and Brumberg [ 1 ]. Indeed, the saving decline is well recognized to be associated with lower rates of capital accumulation and growth in the economy. Saving is crucial for investment and the maintenance of strong and sustainable economic growth. In addition, saving is one of the essential aspects of building wealth and having a secure financial future. It gives a way out from uncertainties of life and enjoy a quality of life.

Hence, it is of great interest to look at the demographic changes impact on saving in order to seek how to prevent saving from such an eventual decline. The empirical studies in the topic, generally, have relied on the life cycle model; as it better explains the varying rates of savings in societies with relatively younger or older populations. However, the LCH’s prediction was not often empirically validated to argue that saving will be automatically depressed consequence of the population aging process. There is evidence that the social and economic conditions limit the scope of the LCH.

This study reviews the LCH to emphasize the most significant factors that may distort its prediction. It focuses on the uncertainty to explain the aging-saving relationship. It tries to check empirically whether uncertainty consideration may distort the LCH. Thereby the aging population do not put a down pressure on saving systematically.

However, given the difficulty to directly and objectively estimate uncertainty extent on saving behavior, we indirectly capture by an auxiliary variable the unemployment. We seek to highlight the influence of the precautionary motive related to the risk of unemployment. Thus, we try to give information about the transmission mechanism between aging population and saving considering the unemployment savings pattern as a determinant of saving behavior in a setting of unavailability of unemployment allowance. So, we draw attention that unemployment is an important factor up to distort the life cycle model’s prediction.

Unlike previous studies, we build our estimates not only on the total dependency ratio (the proportion of population aged less than 15 years and aged 60 years or more versus the proportion aged 15–59) as an aging indicator, but also on the old-age dependency ratio (the proportion of population aged 60 years or more versus the proportion aged 15–59). This will allow us to make comparison and to deduce the effect of the child dependency ratio (the proportion of population aged less than 15 years versus the proportion aged 15–59). Besides, we focus on national saving to avoid narrowing the population aging impacts since the corporate and the government saving are sensitive to population aging as the household saving.

In addition, given the lack of researches on this issue on developing countries (which economic and social environment greatly differ from the developed countries) we devote our study to Tunisian case. Tunisia is an interesting case of study because it is a well advanced in the aging process. As well, it suffers from an enduring and high unemployment rate and an inefficient pension system (as detailed in Section 3). Furthermore, it is characterized by a strong altruistic familial intergenerational relationship [ 2 , 3 , 4 ].

To check out the relationship between aging, unemployment, national saving and economic growth we apply a time series modeling approach over the period 1970–2019. We carry out a Structural VAR model, as defined by Sims [ 5 ]. We analyze the impulse response functions (IRFs) of different shocks for all variable’s fluctuations. We also apply the bootstrap methods to construct the confidence intervals of the IRFs. Additionally, we complete our dynamic analysis by the variance decomposition.

This study represents the first attempt to model the Tunisian aggregate national saving by considering both the impact of demographic changes and of unemployment.

In what follows, we give, in Section 2, an overview of the life cycle hypothesis and its bounds. In Section 3 we give some sight of the demographic change and the saving evolution occurred in Tunisia. In Section 4, we specify the econometric model and in Section 5 we discuss the results found. Finally, we end, in Section 6, with the main findings and policy recommendations.

2. Life cycle pattern overview

In this section we state the life cycle’s savings to emphasize the social and economic conditions that may constrain its validation.

2.1 Life cycle hypothesis

The life cycle theory pinpoints the intertemporal allocation of time, effort and money. In its simple form, the standard life cycle hypothesis’s (LCH) formulated by Modigliani and Brumberg [ 6 ], suggests that individuals save during working life for their consumption needs when they retire, dissave after retirement, and die without wealth. Hence, individuals will smooth consumption over their lifetime regard to the expected lifetime resources. They accumulate wealth during the pre-retirement period by consuming less than their disposable income. So, during retirement, they de-cumulates wealth to finance its consumption. That is, the saving rate should follow a hump-shaped over the life cycle as shown by the Figure 1 (in the Appendix).

Therefore, one very important implication of the LCH is that the demographic profile of a population should be an important factor influencing the aggregate saving rate. Given that population aging is defined as a shift in the population age distribution towards old age, so a change of the balance between youth and elderly proportion (defined in the following as a person aged over 60 years-old) causes society to age and subsequently to affect the saving pattern. 1 Such a change may change the savers proportion in the economy and diminish the aggregate saving rate according to the LCH.

If there is a large proportion of the population working, then, the saving rate should be high. However, if there is a large population proportion over retirement age or very young, the saving rate would be low. This suggests that aggregate saving rate should be negatively correlated with total dependency ratio.

Even though the theoretical conclusion of the life cycle model is clear, the empirical evidence is not often proved and stays controversial until today as it was decades ago. There is evidence that elderly may not dissave, at least not to the extend hypothesis suggested by the pure life cycle model which abstracts a number of factors that would complicate its prediction.

2.2 The life cycle hypothesis bounds

The Life cycle theoretical conclusion is understandable given its simplifying assumptions such as no uncertainty, a finite decision horizon, no inheritance and perfect financial market with no credit constraint [ 7 ]. According to the LCH, individual takes decisions basically depending to events and fact that are known with certainty in each period of life (such future income, death date, and interest rate). Nevertheless, these assumptions are considered too restrictive. Indeed, events are uncertain [ 8 , 9 ] and financial market is imperfect with credit constraint. Uncertainty affects consumption and savings behavior as consumers are generally cautious. Moreover, according to the Kotlikoff [ 10 ] dynastic model of savings, individuals do not act in a finite horizon, but in an infinite one. In addition, they have a dynastic behavior characterized by a strong preference to let, at their death, a very limited capital de-cumulation [ 11 , 12 , 13 ]. Thus, parents, having an altruistic motive, seek to not decumulate wealth to leave inheritance to their children. Consequently, the population aging may not automatically depress national saving. Kotlikoff and Summers [ 14 ] conclude that the “life cycle saving” cannot account for more than 20 percent of U.S. capital formation, and the intergenerational transfers play a dominant role in wealth accumulation, accounting for 80 percent or more of observed wealth.

Additionally, it is worth noting that the conflicting evidence on the life cycle saving may also be due to the econometric approaches used and the aging indicator chosen. Indeed, the micro econometric analysis invalidates life cycle model’s prediction to support the Kotilkoff hypothesis but their results are difficult to aggregate because of severe problem of heterogeneous behavior at the household level. Conversely, studies based on macro data for a country generally support the prediction. However, most of them refer to developed societies while in developing societies people face different economic challenges and social conditions, which may lead to different evidences. In that way, these studies could not be very useful for understanding saving behavior in developing countries. The difference through countries is in the design of pension systems and health care, taxes and transfers as well as labour market conditions, which are unavoidably depend to the population age distribution. As well, they may alter individual economic behavior and so could be the origin of the inconsistency LCH’s evidences.

Also, the choice of the population aging indicator to estimate is crucial. The total dependency ratio which is generally used does not accurately reflect the aged population since it composed of both the old and the child dependency ratio. It is more fitting to use the old-age dependency ratio to explicitly consider the effect of aged population on savings rate [ 15 ]. With more cautious in the aging indicator use, the life cycle model’s prediction is likely to be endorsed also in macroeconomic approach.

2.3 The life cycle hypothesis and uncertainty

The LCH analysis has been gradually enriched, to focus on three reasons for accumulation: the foresight for retirement, the intergenerational altruism and inheritance and the wariness of the saver face to risk (of income, health and lifetime span). In this work, we focus more on the third reason of accumulation by looking at how uncertainty, about future income affects the behavior of the individual’ saving. Uncertainty consideration has made it possible to highlight precautionary behavior as the future work income is random; consumption (otherwise savings) depends not only on expectation, but also on the variance of the expected income. A risk-averse or aware consumer will save more. In fact, savings play an insurance role against the hazards affecting the household, especially the hazards related to income (unemployment, loss of wages, etc.) [ 16 ]. Thus, uncertainty about future income affects the behavior of the individual ‘saving by increasing the demand for precautionary assets, and hence savings amount.

As well, there is precautionary behavior as to face health care expenditure at advanced aged when the risk of health problems is potentially great; notably in the context of inefficient health care system [ 17 ]. As a result, households are saving not only to offset lower future income, but also to insure against all sorts of risks.

However, empirically it is not easy to estimate uncertainty extent on saving behavior. It is difficult to quantify this relationship given the difficulty to directly and objectively estimate uncertainty. Empirically there are no quantitative measurements of uncertainty that could be used directly. In the case studies, income uncertainty is usually measured indirectly by auxiliary variables such as inflation rate, unemployment rate or a derivative of these variables. In this case of study, we focus on unemployment as an income uncertainty indicator to better understand the aging impact on saving and to find an answer to the crucial question: do population aging depress savings?

Unemployment inevitably alters the savings behavior by its two aspects: (1) a high rate and (2) an increase in the average age of unemployed [ 18 ].

(1) The high and persistent unemployment rate weights on household confidence, prompting them to increase their precautionary savings. Such behavior is accentuated in a setting of unavailability of unemployment allowance (like in Tunisia) [ 19 ]. Thus, for precautionary reasons and to finance unexpected income losses, unemployment is viewed as an income uncertainty given the probability to become unemployed alters the savings behavior. Faure et al. [ 20 ] shown that unemployment and the deterioration of household confidence accounted for almost 20% of the aggregate consumption decline.

(2) The increase of the unemployed average age implies that the working population becomes occupied at advanced age. Consequently, they would save a less amount of wealth and they would form a low retirement pension. To offset at this lack of savings they do not immediately dissave at the beginning of the retirement. They would even compensate their low pension by working further after retirement, mainly at the beginning of the period (as long as they stay in better health) to face the future’ uncertainties. Also, given the granting difficulties for credit liquidity at the retirement period, this insufficient pension nudges them to continue to save to keep up a certain level of consumption. It increases, in addition, the need for retirement savings from private sources.

Furthermore, the high and enduring unemployment increases inter-vivos transfers, which represents a form of precautionary saving [ 21 ]. With a dynastic behavior (which is ignored by the LCH) the old generation (parents) saves more throughout the life cycle to help the young generation (their offspring) to facing uncertainty and hard-economic conditions related for instance to unemployment’s conditions. Thus, if intergenerational transfers (by purely altruistic incentive or following a kind of implicit contract between parents and children) are an important motive for savings; elderly rarely decumulate their wealth.

Henceforth, given uncertainty about the future income and lifespan, liquidity constraints, and the wish to leave bequests (a dynastic savings) population aging would not drive the decrease of savings. Therefore, aging economic impact on the household saving and so on the cumulative and on national saving, may not be large [ 22 ].

Hence, for our empirical evaluation of the life cycle hypothesis, we analyze the aging-savings relationship in a developing country, in particular, Tunisia. It greatly differs, economically and socially, from the developed countries, by its altruistic familial intergenerational relationship, the enduring and high unemployment rate and the inefficient pension system; as detailed in the section below.

3. The Tunisian demographic and economic setting

3.1 demographic shifts and age structure evolution.

Tunisia after has shortly ended its demographic transition regime, it has well undertaken the population aging process. During the period 1960–2019, the mortality rate fell from 35 to 40 per thousand to a low rate 5.9. Likewise, fertility which was nearby 8 children per woman fell to 2.17. Thus, the life expectancy has attained an average close to that of developed countries 75.4 years (78.1 years for woman and 74.5 years for man) in 2017.

Accordingly, the population age distribution has shifted towards aging. This fertility decline has narrowed the bottom of the age pyramid by the decline of the younger generation size, while the mortality decline has enlarged the top of the pyramid through the life expectancy gain. Thus, the age range proportion less than 15 years-old becomes less important (passing from 46.5 percent to 24.7) and it is likely to continue its decline. In the contrary, a remarkable increase is recorded for the proportion of person aged over 60 years-old (from 5.5 percent to 12.6) and is expected to increase by 10 points over the future three decades. Therefore, during 1966–2019, the child dependency ratio has sharply declined (from 96.27 percent to 39.36) while the old-age dependency ratio has increased (from 11.60 percent to 20.08). Consequently, the total dependency ratio has decreased (from 107.86 percent to 59.44).

3.2 Economic setting

Tunisian economy recorded a high and enduring unemployment. Over the period 1966–2000, it has increased by 6.1 points to pass from 12.5 percent to 18.6, and then fell slightly to stabilize during the last two decades (2000–2019) around 15.3 percent. Additionally, aging has hit the age composition of the unemployed. Indeed, the modal age range of the unemployed population has moved from less than 25 years-old (by about 29 percent) to 25–29 years-old (by about 34.2 percent) during 2005–2011. It is worth noting here that Tunisian authorities do not distribute any unemployment allowance. 2

For the national saving, it has evolved with some fluctuations. During the period 1970–2010, the national saving rate (of gross national disposable income) was relatively stable around an average of 22.8 percent then progressively fell to achieve 9.3 in 2019, mainly due to a steady loss of purchasing power. 3

According to the Islamic Development Bank, the behavior of Tunisian investors appears to be driven by factors related to consumer demand and/or the income effect [ 23 ]. The financial changes in interest rates have more effect on the savings structure than on its volume. Indeed, the financial liberalization policy adopted (since the structural adjustment plan in 1986) has not succeeded to stimulate private savings through the increasing of the real interest rates [ 24 ]. In Tunisia, saving behavior seems to comply more to the Keynesian approach.

However, an interest for the long-term financial savings is recorded. During 2010–2017, the listed companies increase from 56 to 81 with a broad sectors diversification. Likewise, the life insurance, as a long-term saving vehicle, has undergone an important increase; the average annual growth rate was 18 percent in 2017. Its share in the insurance market has climbed from 12.05 percent in 2009 to 20.2 in 2017; however, it remains far from the international standards (about 56.2 percent).

This interest for the long-term savings is explained by the failure of the pension system the pay-as-you-go system and the bankruptcy of the provident fund as well as the authority’s future intention to withhold a proportion of the retirement pension. 4 Thus, the insured people are driven to form a complementary retirement pension under others retirement savings forms through voluntarily paying into saving schemes in private financial institutions. This savings form is encouraged by the financial authority through the establishment of tax benefits.

Concerning the non-financial savings, it is allocated to buy housing, jewelry or land by household and productive assets by individual corporate. Household saving is particularly oriented to housing savings which has experienced a growth rate of about 5.5 percent during 2000–2017.

4. Econometric model and data specification

To look at the relationship between population aging and savings in an unemployment context in Tunisia over the period 1970–2019, we apply a structural VAR model, as defined by Sims [ 25 ]. This enables us to approach a multivariate causal setting allowing the coexistence of both short and long-term forces derived from the aging influences on saving decisions. Finally, we deepen our dynamic analysis by application the techniques of impulse response functions (IRFs) of different shocks for all variable’s fluctuations and of the variance decomposition (VDC).

4.1 Data specification

To undertake the aggregate saving model estimating, we use as an independent variable the national savings rate unlike previous studies, which generally referred to the household savings rate. National saving is important as it is a source of investment and one of the major determinants of macroeconomic growth. Also, as it is closely related to the demand for financial and real assets and it may affect asset price formation. In addition, we seek to avoid narrowing the aging impact as its takes into account companies and public sector saving (related to social sector, health, education and pensions). On another side, the household savings refers to survey measure which undervalues personal income as it provides information related to expenditure than to income sources. Likewise, it does not capture the same share of total saving for persons at different ages, so the estimate of relationship between savings and age may be fallacious.

As a definition, between the two known alternative measures of savings (S) we adopt that of national account (as income minus consumption expenditure) given data availability. 5 Explicitly, we use the savings rate with respect to the gross national income disposable income 6 .

For independent variables, we refer to the main population aging indicators. We consider the mortality rate (MR) and fertility rate (FR) to capture demographic changes and its impact on the age structure composition, and likewise on the dependency ratio. We consider the old-age dependency ratio (EDR) to accurately look at the effect of aging besides the broadly used the total dependency ratio (TDR). Then, we could deduce if the aging impact is due to the fertility decline or to the longevity increase.

Concerning economic variables, we include three macroeconomic variables. (1) Basing to the neoclassical approach we introduce the interest rate (MMR) in particular the money market rate as a driver of the real interest rate (credit and debit). (2) As a one quantitative measure of aggregate income uncertainty we consider the aggregate unemployment rate (U). (3) In order to check the economic effect of saving, we examine the economic growth (G) measured by the GDP per capita at constant domestic prices. It is computed by dividing GDP per capita at current domestic prices by the consumption price index (base 1990). Hence, the inflation rate is indirectly considered.

The main statistical characteristics of these variables used are summarized in Table 1 (in the Appendix). Data are drawn from the Central Bank of Tunisia (CBT), the National Institution of Statistics (NIS) and Tunisian Institute of competitively and quantitative study (ITCQS).

4.2 Econometric models

Our analysis is based on the identification and estimation of structural vector autoregressive (SVAR). The SVAR model is used in macroeconomic analysis in order to check the effect of exogenous shocks (of the demographic change, for instance) on macroeconomic variables.

Our basic model VAR is the following:

where Y t is a column vector of stationary variables considered in the estimate.

The selection and order of independent variables are essential in the SVAR estimate. Thus, the independent demographic variables are introduced with caution following the demographic transition theory. As mortality decline brings that of fertility, so we first introduce the mortality rate (MR) followed by the fertility rate (FR). Then, we integrate the dependency ratio as an indicator of the population aging and the age structure change following the demographic transition.

After what, we consider the economic variable exogenous effect on saving. So, we insert the interest rate (MMR) as a saving determinant and the aggregate unemployment rate (U) as a measure of aggregate income uncertainty. Lastly, we introduce the national savings rate (S) followed by the economic growth (G) to check the aging impact on economic growth through the savings evolution.

As we use two dependency ratios, we estimate two distinct vectors autoregression. A vector includes the total dependency ratio which reflects the effect of both the mortality and fertility evolution as a result of the demographic policy as follows (MR t , FR t , TDR t , U t , MMR t , S t , G t ).

The second vector includes the old-age dependency ratio and takes the mortality choc as the main cause of the elderly proportion evolution as follows (MR t , EDR t , U t , MMR t , S t , G t ).

Otherwise, Γ(L) = Γ 1 L 1 + Γ 2 L 2 + … + Γp. L p is a lag operator in the form of polynomial matrix and ν t is a vector of idiosyncratic errors, where ν t = (μ 1 t ,…,μ 5 t ) ’ . These errors are not auto correlated and are homoscedastic. Then, the representation (1) can be written in the form of a moving average of infinite order VMA (∞) (representation theorem of Wald):

where C(L) = [I - Γ(L)] −1 .

The structural form (SF) of the model (1) can be written as follows:

where A(L) = C(L) H is the coefficient matrix (a ij ) of (7 × 7 or 6 × 6 for the two vectors respectively) size, and more precisely it represents the impulse response functions of the elements of Y t following the various shocks. Moreover, H is the transition matrix and ε is the vector of structural shocks where E (ε t ε t ’) = I N .

However, the identification of these shocks requires the Cholesky decomposition in the order to identify the structure of the shocks. As a result, the decomposition of the variance covariance matrix of the reduced form residuals is written in a lower triangular matrix A(L). The number of constraints imposed on A(L) is equal to 21 i.e. n × (n-1) / 2 with n = 7 variables and where some of the structural shocks do not have contemporaneous impact on other variables.

Additionally, the Cholesky decomposition assumes that series listed earlier in the VAR order impact the others variables contemporaneously. But series listed later in the VAR order impact those listed earlier only with lag. Therefore, the variables listed early in the VAR order are considered more exogenous. As mentioned above, the order of endogenous variables is central to the identification of structural shocks, i.e. it determines the structure of the shocks. More precisely, the first variable has impacts on all the variables that are below it, but it does not receive any impacts from these variables. This rule applies to all subsequent variables. For instance, the triangular matrix A(L), for the case of n = 7 variables, is as follows.

Henceforth, we have to estimate four matrixes: a matrix (Alt1) for the total dependency ratio and one for the old-age dependency ratio (Alt2). Two others matrixes are also estimates as a robustness test by omitting the unemployment rate, respectively the matrixes (Alt3) and (Alt4).

To undertake the SVAR estimate model, we first study the stationarity of all variables using the Phillips-Perron test [ 26 ]. As reported in Table 2 (in the Appendix) all the considered variables are I(0) suggesting that a long-run (cointegration) relationship could exist between the considered variables.

Then we determine the order p of the VAR process to remember. To do this, we consider various processes for VAR lag orders p ranging from 1 to 4. For each model, we calculate the Akaike information criteria (AIC) and Schwarz (SC), and the log-likelihood (LV) to hold the p lag (=4) that minimizes these criteria as indicated in Table 3 (in the Appendix).

Accordingly, four alternatives are estimated, respectively with the identification of cointegration relationships by using the cointegration test of Johansen [ 27 ] as well as the structural factorization (with 500 iterations).

Finally, to examine the dynamic of the model, we refer to the impulse response function (IRF). It helps us to judge and to appreciate the channel(s) of population age structure change transmission. It allows to see if there is really a robust, stable and predictable relationship between aging and savings. In this respect, we will identify the different responses of all the variables in the model to various shocks. It should be noted that we focused on the effects of the shock on 10 periods and that errors are generated by Monte Carlo with 100 repetitions. Such analysis is strengthened with the variance decomposition analysis (VDC), which however, indicates the proportion of the variable changes due to own shocks versus shocks on the other variables. Namely, the variance of the forecast error of the change in savings rate is partitioned among the contributions of the innovations in each variable of the system.

5. Results interpretation

Interestingly, results put forward that the LCH prediction is not automatically confirmed, but it is up to the economic uncertainty extent. Indeed, the LCH is not validated in the unemployment setting, which is considered in our study as an indirect measure of income uncertainty.

5.1 The SVAR results interpretation

The SVAR’s estimate results (reported in Table 4 in the Appendix) points out that uncertainty encourages saving. Indeed, for the two aging indicators used (TDR and EDR) the LCH prediction is not validated once unemployment is introduced unlike Ahmedova’s [ 28 ] findings. As we note from matrixes Alt1 and Alt2, the two indicators present a significant positive effect on savings rate in the context of enduring unemployment without allowance, like in Frini’ work [ 29 ]. However, this effect is found more significant for old-age dependency ratio, unlike in Wong and Tang [ 30 ] and Loumrhari’s [ 31 ] findings.

In contrast, the LCH prediction is validated by the estimate omitting the unemployment rate, however, for only the total dependency ratio. Indeed, a significant negative effect is found in the matrix Alt3.

Such results confirm that the demographic changes impact on saving depends on the perception of the economic context and the confidence towards future. Furthermore, the LCH’s validation appears to be, as well, empirically related to the aging indicator used in the estimate. This confirms our proposal that the old-age dependency ratio indicator seems more efficient to explicitly check the effect of aging.

The unemployment which hints uncertainty about future income pushes the savers to keep up savings. It reduces confidence and intensifies incentives for precautionary saving so that, it prevents savings from decline. Indeed, the unemployment rate displays a significant and positive coefficient. The weight of the future uncertainty boosts the employed population to form a precautionary savings. This precautionary saving is important to offset the small amount of wealth accumulated after an enduring unemployment without any allocation benefit. When enduring a long unemployment period and facing great difficulties for credit liquidity at old age, elderly try to continue to save to keep up a certain level of consumption. Such behavior is very pronounced in Tunisia since retired do not benefit from a sufficient pension in a distressed pay-as-you-go system. The insufficiency of pension and medical care benefits entails the elderly saving’s behavior adjustment by continuing to work and to save at the beginning of the retirement period (as long as they remain in better health). As pointed out by Frini [ 32 , 33 ] the new retirees or the youngest elderly (which share, generally, weighs more than that of the old retirees or the old elderly) maintain their savings mainly for precautionary motives in high uncertainty economic environment.

This Tunisian elderly saving behavior may in part be strengthened by the intentional transfers motivation of the old generation towards the young one. Indeed, Tunisian families, as stressed by Mahfoud [ 34 ] and Frini [ 35 , 36 ], are strongly linked and directed by an intergenerational altruistic motive. So, the old generation do not seek to cut savings so as to help the young generation to face uncertain environment and hard economic conditions.

As expected, mortality drop induces a fertility decline, putting on show the demographic transition theory. This fertility decline increases the savings rate. It seems that the youth share decrease outweighs the small increase in the elderly share since the aggregate savings rate increases. Household with fewer children are likely to incur less expenditure in respect to their income for looking after them and then would save more. In addition, a reduced family size leads to a competition between children as a mean of transferring income from present to future and as a financial asset. 7 Henceforth, by the fall of fertility rate, the demand of financial and capital market as a substitute of youth assurance service will increase and thus savings. Additionally, the decline of government expenditures for youth (given their share decline), seems to make up or even more the government expenditures increase for elderly (due to their share increase) to not lead savings decrease.

Considering uncertainty, mortality evolution positively influences savings rate when considering the economic and social facts, but negatively when they are neglected. The increase of mortality risk and health problem intensifies precautionary behavior to face health care expenditure at old age.

The uncertainty related to interest rate affects positively the savings rate. An increase in interest rate will make saving more attractive. Finally, like in AbuAl-Foul’s [ 37 ] work results show that no long-run relationship exists between saving and GDP growth. This in part due to that saving is, generally, done in real estate, which is known as a small creator of wealth with a small ripple effect.

5.2 The IRF’s and VDC’s results interpretation

Likewise, the IRF’s and VDC’s results underline that population aging on savings evolution changes respect to the economic uncertainty context. Savings positively respond to age structure changes once unemployment is taken into account. The different graphs of impulse responses ( Figure 2 in the Appendix) show that savings respond quickly to demographic changes (mortality rate, fertility rate and dependency ratio jointly), but weakly to the shock of the money market rate. The response due to unemployment rate shock can be judged as significant with a return to equilibrium in the long-term. The saving response to economic growth innovations is, however, slow and limited. This analysis is corroborated out by the variance decomposition as displayed in Table 5 (in the Appendix). 8 In detail, a relatively constant proportion of the change in savings rate variance is recorded for both ratios. The total dependency ratio shock is by about 3.75 percent for Alt1 and by 4.26 percent for Alt3 after three years. The old-age dependency ratio shocks are, however, of a less proportion by 1.42 percent for Alt2 and 0.16 percent for Alt4 over ten years. The noteworthy result is that savings evolution follow-up a shock of the total dependency ratio is more significant (by three times more) than of the elderly one. This fact is also proved by the dynamic response path. Fewer children lower the dependent population and consumption without contribution to income. The decrease of the youth dependent proportion out weights the increase of the elderly dependent in the proportion, which limits saving rate depression. This brings up the role of relative weight of the youth share to the elderly share on savings evolution. Further, the increase of elderly proportion appears not to cut savings rate. Thus, savings rises when fertility declines and longevity increases, but less intensively. In the contrary, to the LCH prediction, the old-age dependency ratio shock instantaneously and positively affects saving rate, however, more weakly than the total dependency ratio.

Remarkably, once we ignore the labour market unbalance (or uncertainty) of the estimates the relationship between aging and savings becomes consistent with the LCH prediction. The total dependency ratio shocks present a negative short-term impact on saving to disappear at long-run (after eight years). However, no impact is found for the old-age dependency ratio. This discrepancy in estimated magnitude through the two dependency ratios used refers back to our assumption that aging impact may be sensitive to the measurement used to describe it.

Moreover, demographic indicators shocks trace the variance of savings innovations. Mortality rate explains saving variance by almost the same small proportion (by about 2.30 percent) for all alternatives in the variance decomposition, but relatively less without the unemployment rate. In the impulse function graph, a negligible positive impact is found of mortality shock. Hence, with the rise of longevity and elderly proportion savings may not decline. Fertility decline significantly contributes in the savings change variance (by about 5.16 percent in Alt1) and even much more when forsaking the unemployment rate (by about 17.79 percent in Alt3). The corresponding impulse function displays a negative influence over six years to reverse positively after.

However, saving is less sensitive to interest rate shock. Money market rate contribution is more pronounced for the total dependency ratio than the elderly one. The same evidence is observed through the impulse function graph shown a very small positive influence which disappears in the long-term. This small impact of the real interest rate on saving may hide the offsetting of its two effects (of income and substitution). In other hand, it may be related to the Tunisian household’s behavior which seems to comply more with the Keynesian approach.

Finally, in the long-term, savings shocks seem to produce an effect on economic growth, but weakly when the imbalance labour market is considered (as reported in Table 6 in the Appendix). As mapped out by the response functions this dynamic is non-instantaneous. In contrast, a very small ‘feed-back’ seems to be produced of economic growth over three years on saving.

6. Conclusion

This study puts on show that the life cycle prediction of a downward pressure on saving by aging population could not be proved under uncertainty. Population aging is, on contrast, found to exert a long-term upward pressure on saving in an unemployment context. The economic environment’s uncertainty (such income uncertainty) quantified, in our case of study, by the unemployment phenomenon, looks to be an essential factor of the change in the life cycle pattern of savings. It is able to shaping the saving behavior and to distort the LCH. The impact of the demographic change seems strongly related to the economic confidence factors. Accordingly, the social and economic conditions limit the scope of the LCH. Thus, population aging will not necessarily spell disaster on national saving. Consequently, studies’ findings on developed countries could not be representative of saving behavioral in developing countries; where pension and medical insurance schemes are less developed and the persistent unemployment is without unemployment allowance benefit. Furthermore, it seems that the empirical findings checking the LCH depend on the aging indicator used. In fact, the use of the total dependency ratio could not validate the LCH, but it is validated by the old-age dependency ratio use. So, with more caution on the population aging measure, the evidence that elderly do not dissave may be found and the life cycle prediction may not be endorsed. Henceforth, the life cycle hypothesis may not be validated in macroeconomic approach as in the micro-econometric approach.

Finally, as policy implications, several measures are needed to sustain saving rate or to prevent it from an eventual decline. In addition to the strategy applied lately to postponing the retirement age to 62 years-old, Tunisian Policy-makers have to accelerate the move from the pay-as-you-ago public pension system towards the funded pension system to cut costs of increasing old-age benefits. As well, to mobilize more savings, they should shift the liquid savings towards long-term products. Accordingly, it is important to reconsider the long-term savings strategy to meet the household’s needs as well as the huge potential investment’s needs. Therefore, major economic and financial reforms should be undertaken to restructure public corporates and the partial openness of their capital, to strengthen the pension plans, to develop the insurance sector and promote life insurance, and to improve the framework of the stock market and the bond market and diversify product of savings.

Consumption,consumer income, wealth and saving over the life cycle.

Descriptive statistics variables.

Unit root test of ADF.

Note: The null hypothesis for the ADF test is that the series are non-stationary i.e. there is presence of unit root. The values in the table indicate the p-values of this test. Using the Phillips-Perron test, the results were the same.

* and **denotes that the null hypothesis of unit root is rejected at the 5% level and 10% level respectively.

Choice of the lag number of VAR (p) process.

Note: LV denotes the log-likelihood; the asterisk indicates P order to retain according to the criterion used.

SVAR estimates results for the four alternatives.

Variance decomposition of saving rates (Cholesky ordering).

Notes: Cholesky ordering follow that of the four alternatives. The second column (S.E) shows the forecast error of the variable at the given forecast horizon. The source of this forecast error is the variation in the current and future values of the innovations to each endogenous variable in the VAR. The other columns give the percentage of the forecast variance due to each innovation.

Variance decomposition of economic growth to saving rates.

Estimated impulse response functions. Response to Cholesky one S.D. innovations.

Classifications

JEL Classifications: J1, E2, C3

- 1. Modigliani, F. & Brumberg, R. (1954). Utility Analysis and the Consumption Function: An Interpretation of Cross-section Data’ Post Keynesian Economics , ed Kenneth K. Kurihara. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- 2. Frini, O. (1996). Le transfert intergénérationnel et accumulation du capital humain: cas de la Tunisie . A search dissertation.

- 3. Frini, O. (2014). The Familial Network Influence on Fertility Behaviour in Tunisia. Journal of Economic and Social Research, 16(1–2), 33-61

- 4. Mahfoud Draoui, D. (2006). Entraide familiale et nouvelles formes de solidarité’, 2 ème table ronde des cercles de la population et de la santé de la reproduction; “dynamiques familiales et solidarités intergenérationnelles” ONFP, Tunis 24 February 2006.

- 5. Sims, C (2002). Solving Linear Rational Expectations Models. Computational Economics 20, 1–20.

- 6. Modigliani, F. & Brumberg, R. (1954). Utility Analysis and the Consumption Function: An Interpretation of Cross-section Data’ Post Keynesian Economics , ed Kenneth K. Kurihara. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- 7. Attanasio, O. & Weber, G. (2010). Consumption and Saving: Models intertemporal Allocation and their implication for Public Policy. Journal of Economic Literature, 48(3), 693-751. http://www.nber.org/papers/w15756.pdf

- 8. Leland, H. (1968). Savings and Uncertainty: The Precautionary Demand for Savings. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 82, 465-473.

- 9. Nagatani, K. (1972). Life Cycle Savings: Theory and Fact, American Economic Review 62(1), 344-353.

- 10. Kotlikoff, L. (1988). Intergenerational Transfers and Savings, Journal of Economic Perspectives 2, 41-58. DOI: 10.1257/jep.2.2.41.

- 11. Ameriks J., A., Laufer, C., S. & Van Nieuwerburgh, S. (2011). The Joy of Giving or Assisted Living ? Using Strategic Surveys to Separate Public Care Aversion from Bequest Motives. The Journal of Finance, 66(2), 519-561. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2010.01641.x

- 12. Lockwood, L. (2016). Incidental Bequests: Bequest Motives and the Choice to Self-Insure Late-Life Risks. NBER Working Paper No. 20745.

- 13. De Nardi, M., French, E., & French, J. (2016). Medicaid Insurance in Old Age. The American Economic Review, 106(11), 3480-3520. http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.20140015 .

- 14. Kotlikoff, L. J. & Summers, L. H. (1981). The Role of Intergenerational Transfers in Aggregate Capital Accumulation, Journal of Political Economy 89 (4), 706-732.

- 15. Ahmedova, D. (2011). The impact of population Ageing on Private Savings Rate: Empirical Evidence from the OCDE Members Countries. Department of Economic, Central European University.

- 16. Antonin, C. (2018). Les liens entre taux d’épargne, revenu et incertitude. Une illustration sur données françaises . Documents de Travail de l’OFCE 2018-19. Observatoire Français des Conjonctures Economiques.

- 17. De Nardi, M., French, E., & Jones, J. (2010). Why Do the Elderly Save? The Role of Medical Expenses’, Journal of Political Economy, 118(1), 39-75. DOI: 10.1086/651674.

- 18. Kessler, D., Perelman, S., & Pestieau, P. (1993). Savings behavior in 17 OECD countries. Review of Income and Wealth Series, 39, (1)

- 19. Engen, E. M., & Gruber, J. (2001). Unemployment insurance and precautionary saving. Journal of Monetary Economics, 47 (3), 545-579.

- 20. Faure, M-E., Soual, H., & Clovis, K. (2012). La consommation des ménages dans la crise. Note de Conjoncture : 23–37.

- 21. Kotlikoff, L.J., & Spivak, A. (1981). The Family as an Incomplete Annuities Market. Journal of Political Economy, 89(2), 372-391.

- 22. Yamauchi, N. (1996). The effects of Aging on National Saving and Asset Accumulation. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) , Inc , 131-151.

- 23. BID, Thomson Reuters, IIRF and CIBAFI (2013) Tunisie prudemment optimiste Rapport pays sur la finance islamique, Retrieved from : http://www.irti.org/irj/go/km/docs/documents/IDBDevelopments/Internet/English/IRTI/CM/downloads/Reports/Tunisia_Islamic_Finance_Country_Report_Cautiously_Optimistic_Fr.pdf/

- 24. Tunisian Professional Association of Banks and Financial Institutions (2005) ‘L’épargne’, Retrieved from: http://www.apbt.org.tn/upload/telechargement/

- 25. Sims, C (2002). Solving Linear Rational Expectations Models. Computational Economics 20, 1–20.

- 26. Phillips, P. C. B., & Perron, P. (1988), Testing for a Unit Root in Time Series Regression, Biometrika, 75, 335-346.

- 27. Johansen, S (1988) Statistical analysis of cointegration vectors, Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 12, 231-254.

- 28. Ahmedova, D. (2011). The impact of population Ageing on Private Savings Rate: Empirical Evidence from the OCDE Members Countries. Department of Economic, Central European University.

- 29. Frini, O. (2021). The relationship aging of the population and saving in an unemployment context: Empirical evidence using an autoregressive distributed lag bounds testing approach. Australian Economic Papers, 60(1), 98-121. DOI: 10.1111/1467-8454.12195.

- 30. Wong, B. & Tang, K.K. (2013). Do Ageing Economies Save Less? Evidence from OECD Data, International Journal of Social Economics, 40(6), 591-605.

- 31. Loumrhari, G. (2014). Ageing, Longevity and Savings: The Case of Morocco, International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues . 4, 344-352.

- 32. Frini, O. (2018). Do elderly really dissave? Empirical analysis using ARDL and NARDL bounds approach’4 èmes Journées Economiques et Financières Appliquées; Mahdia Tunisia 11 - 12 May 2018.

- 33. Frini, O. (2021). The relationship aging of the population and saving in an unemployment context: Empirical evidence using an autoregressive distributed lag bounds testing approach. Australian Economic Papers, 60(1), 98-121. DOI: 10.1111/1467-8454.12195.

- 34. Mahfoud Draoui, D. (2006). Entraide familiale et nouvelles formes de solidarité’, 2 ème table ronde des cercles de la population et de la santé de la reproduction; “dynamiques familiales et solidarités intergenérationnelles” ONFP, Tunis 24 February 2006.

- 35. Frini, O. (1996). Le transfert intergénérationnel et accumulation du capital humain: cas de la Tunisie . A search dissertation.

- 36. Frini, O. (2014). The Familial Network Influence on Fertility Behaviour in Tunisia. Journal of Economic and Social Research, 16(1–2), 33-61.

- 37. AbuAl-Foul, B. (2010). The Causal Relation between Savings and Economic Growth: Some Evidence from MENA Countries’, The 30 Th MEEA Meeting Atlanta .

- Population aging arises from two demographic phenomena the birth and the mortality decline. As for declining fertility, it reduces the number of children, which is generally considered a main explanation of growing aging. For mortality decline, it increases the longevity and the number of elderly.

- Source: NIS employment 1966, 2005, 2007, 2010, 2011.

- During 2011–2019 inflation rate has passed from 3.7 percent to 6.2.

- For instance, during 2010–2017, the overall financial situation of the three funds of the social security recorded a very serious drop going from 40MD in 2010 to −1326 MD.

- The second defines savings as the changes in net wealth. Net wealth accumulation includes capital gains and losses, adjusted for general inflation, and is more relevant for purposes of measuring changes individual’s economic well-being.

- Gross national income equal to the gross national income minus the current transfers (current taxes on income and wealth, social security contributions, social security benefits) paid to non-residents units plus the current transfers received from the rest of the world by the residents.

- Children is treated as pure capital goods and a kind of safety assets which returns are “elderly assurance”.

- The VDC indicates the proportion of the variable changes due to own shocks versus shocks on the other variables. The Cholesky decomposition method is used in orthogonalizing the innovations across equation. Percentage of forecast variances is explained by innovations.

© 2021 The Author(s). Licensee IntechOpen. This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Continue reading from the same book

Published: 28 September 2022

By Ombeswa Ralarala and Masenkane Happiness Makwala

70 downloads

By Maria Letizia Bertotti

256 downloads

By Meng Sun

557 downloads

Top 4 Types of Hypothesis in Consumption (With Diagram)

The following points highlight the top four types of Hypothesis in Consumption. The types of Hypothesis are: 1. The Post-Keynesian Developments 2. The Relative Income Hypothesis 3. The Life-Cycle Hypothesis 4. The Permanent Income Hypothesis.

Hypothesis Type # 1. The Post-Keynesian Developments:

Data collected and examined in the post-Second World War period (1945-) confirmed the Keynesian consumption function.

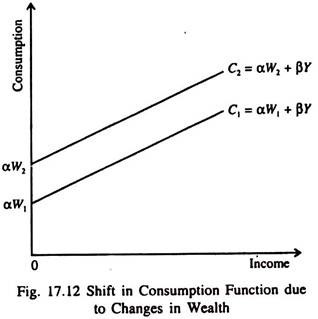

Time series data collected over long periods showed that the relation between income and consumption was different from what cross-section data revealed.