- Top Courses

- Online Degrees

- Find your New Career

- Join for Free

7 Effective Note-Taking Methods

Do you want to take better notes? Explore seven effective note-taking methods, including the Cornell method, the sentence method, the outlining method, the charting method, the mapping method, the flow-based method, and the rapid logging method.

![assignment on notes [Featured Image] Three smiling multiracial professionals sitting at a table taking notes on paper and laptops.](https://d3njjcbhbojbot.cloudfront.net/api/utilities/v1/imageproxy/https://images.ctfassets.net/wp1lcwdav1p1/kqbx26KjuBkmpPAKhB1bR/54544b1dc609d11cb1223482802d2b53/GettyImages-1439944720.jpg?w=1500&h=680&q=60&fit=fill&f=faces&fm=jpg&fl=progressive&auto=format%2Ccompress&dpr=1&w=1000)

Taking notes while learning is a great way to record information to review later. Note-taking can also help you stay more focused on the material you’re listening to or reading and help you remember your questions and comments while listening to the material. To get the most out of your notes later, you can use systems or note-taking methods to organize what you write down.

In this article, you’ll learn about seven effective note-taking methods and how they can help you get more value out of your notes.

Effective note-taking methods

One way to take practical notes is to adopt a system or method. Your best note-taking method will be the one you use frequently or makes the most sense to you. You can also change your method, although you might consider finding what works and sticking with it. Consistency will make it easier to stick with the habit of taking good notes, and it will make it easier to review your notes later.

Below, you’ll find seven examples of note-taking methods to try, although you can find more to choose from if you’d prefer. You may also blend styles to find a hybrid method that’s most effective for you. The important thing is to create consistent notes highlighting the most critical points of the lecture to review later, as well as key terms and potential exam questions.

1. The Cornell method

Developed at Cornell University, the Cornell note-taking method begins by dividing the page into three sections: A column along the left-hand side of the page, a row across the bottom, and the rectangle that remains centered along the top and right edges of the page. The last section, the rectangle, will be the only section you write in while actively taking notes during a lecture, while the others will remain blank for now.

During the lecture, your primary goal is to record as much information as possible in the note-taking sections of your notes. Immediately after the lecture is over, you will use the left-hand column to record the major points of the lecture as well as any potential information that may be on the exam. This is also a place for ideas, questions, and other notes you want to retain. You'll also use the footer or bottom column to summarize the notes on the page.

Why use the Cornell method

The Cornell method makes it easy to identify the most essential points of the lecture. You can mark cues like an asterisk or exclamation point in the left-hand column to mark important details to return to later. The design is flexible and uncomplicated, making it easy to use in various settings or lecture topics.

Another advantage to the Cornell method is that you must finish your notes after the lecture, which forces you to think about the material you just learned and rephrase it in your own words. This helps you retain more information.

2. Sentence method

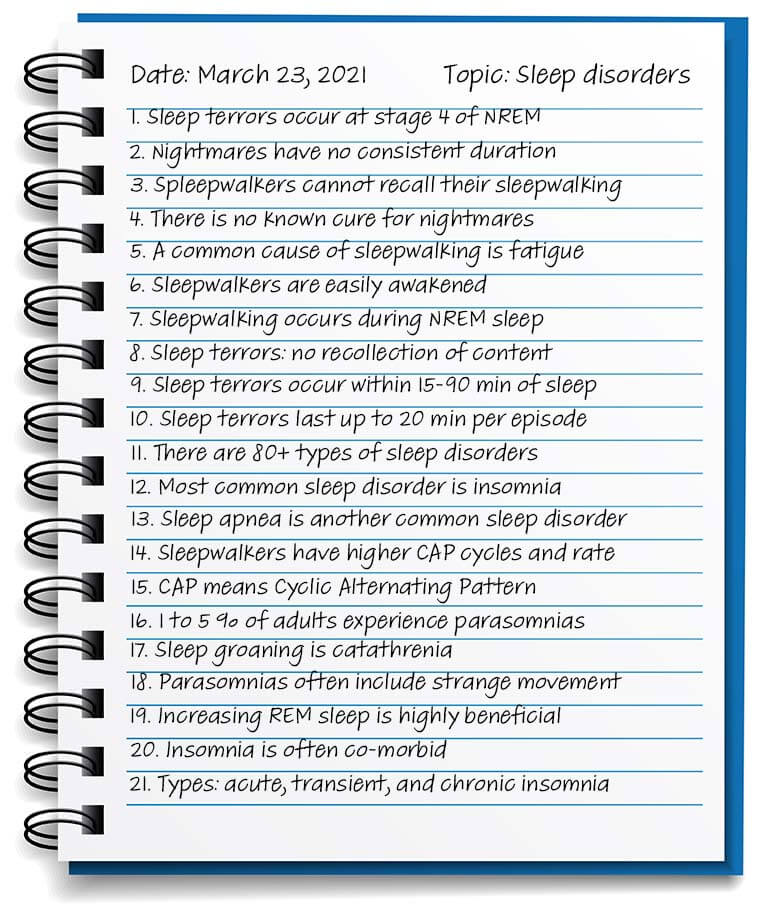

The sentence method, or list method, is a way of capturing as much information as possible. It’s a simple method where you record every thought or sentence on a new line without pausing to organize or prioritize the information. With the sentence method, you won’t spend time during the lecture working out which points are the main points to study later, leaving you with more time to listen to the lecturer and write down more of what they are saying.

You can improve your notes after class by spending a few minutes clarifying and categorizing your notes, marking down main ideas and potential exam questions, and taking notes of any questions you have.

Why use the sentence method

The sentence method allows you to take notes quickly, which is especially useful for keeping up during a fast-paced lecture or a class that presents much information. The sentence method is also useful when you don’t have clues about the lecture format ahead of time, such as with a syllabus or agenda.

While the sentence method has a clear time-saving benefit, it doesn’t allow you to engage with the content as you would if you were paraphrasing in your own words. By returning to your notes later to add context and review, you can get more study power out of your efforts.

3. Outlining method

The outline method involves creating an outline of the important points of the lecture using numbers, letters, and indentation to show information hierarchies. You can use a more traditional outline structure or incorporate other symbols to help you designate the main ideas, ideas that support those ideas, and the more minor details of each sub-category.

Learning to use the outline method when using pen and paper to take notes can take some practice because it can be difficult to identify relationships between different pieces of information during a live class or lecture. Outlining is especially useful on a computer because you can quickly change and edit how information is organized as the lecture progresses.

Why use the outlining method

The outlining method helps you quickly understand how information relates to each other. It’s also easy to review and make sense of later. The outline method is beneficial if your professor gives you a syllabus or agenda to add structure to your notes before the class begins. In that circumstance, you can pre-populate your notes and focus on adding details while the lecture is underway.

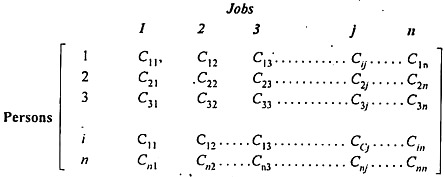

4. Charting method

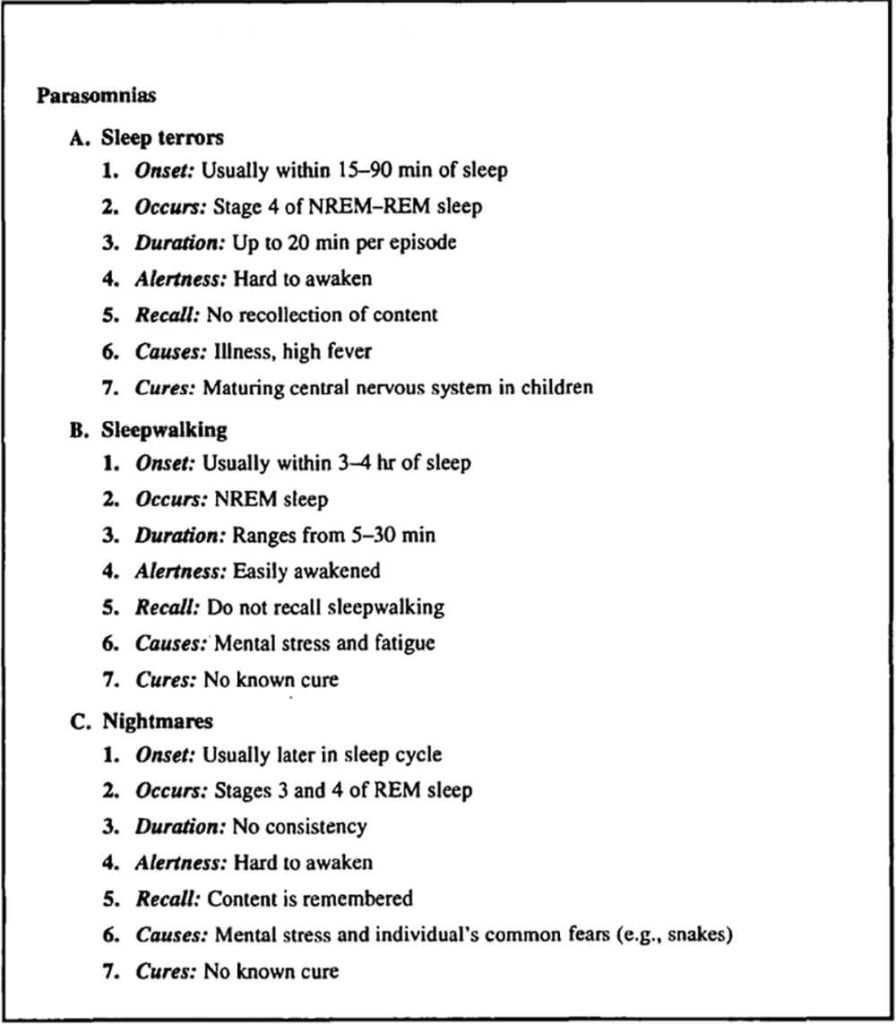

The charting method is a way of visually organizing your notes in a chart. This method works best when summarizing information you’re taking notes with headings.

For example, a lecture about famous people throughout history might use a chart to list each person along the left-hand column, with topics like “early life,” “major achievements,” or “historical significance” along the top. As the lecture progresses, you can fill each box with notes to review later.

Why use the charting method

The charting method helps you understand the material visually. It’s particularly effective for keeping track of important details in a lecture, such as dates or numbers, that can get lost in the chaos of other note-taking forms.

Another advantage of the charting system is that it reduces the writing you must do to organize the information. Plus, the visual nature of a chart makes it easy to review later or to create study materials.

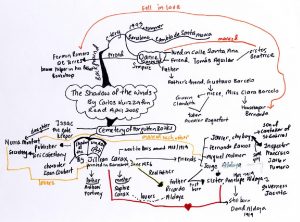

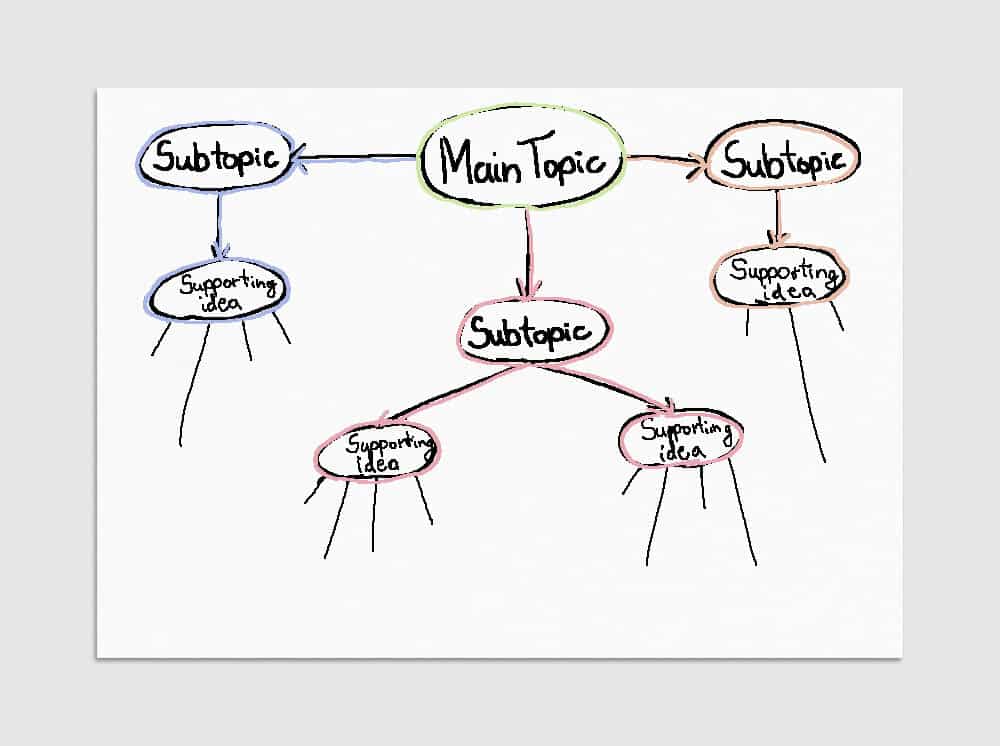

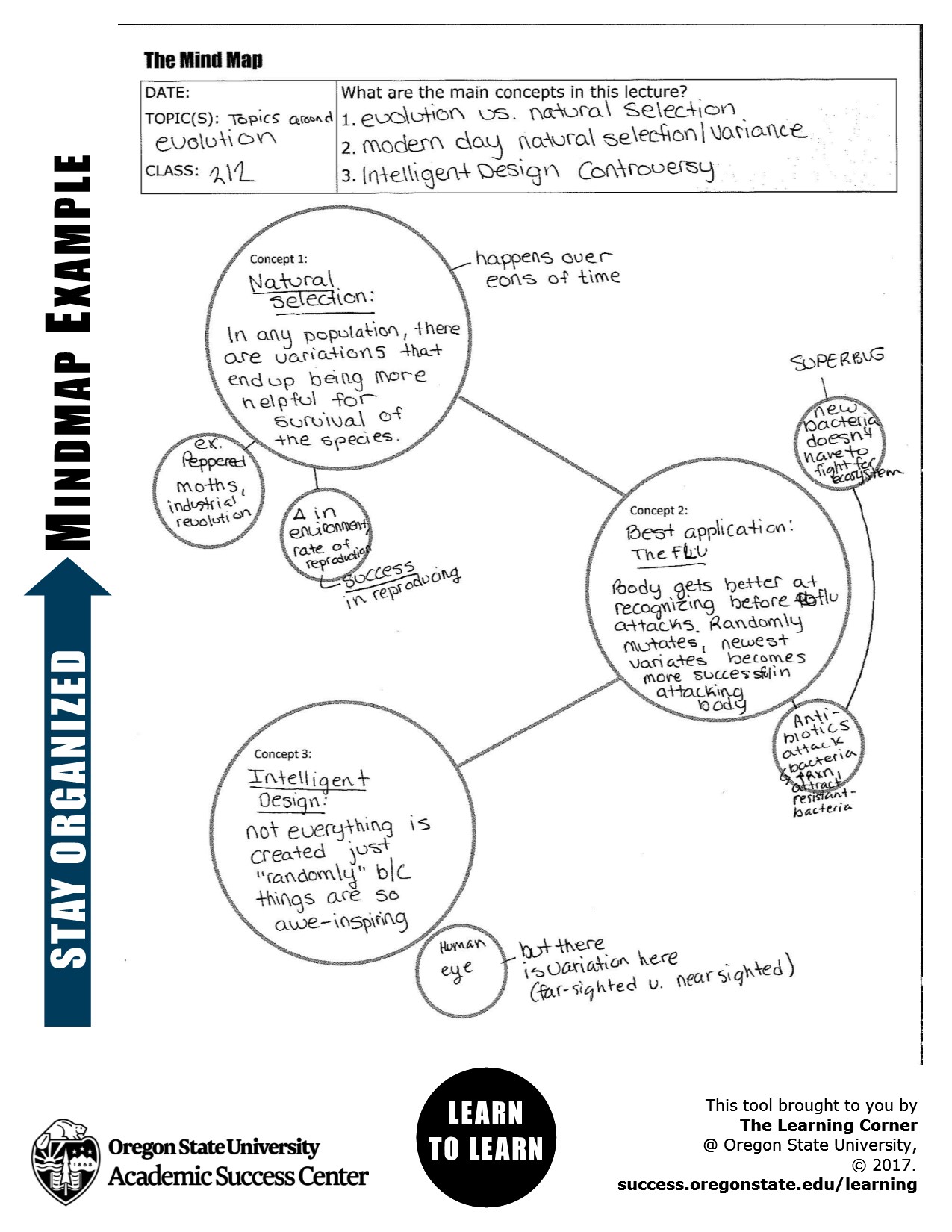

5. Mapping method

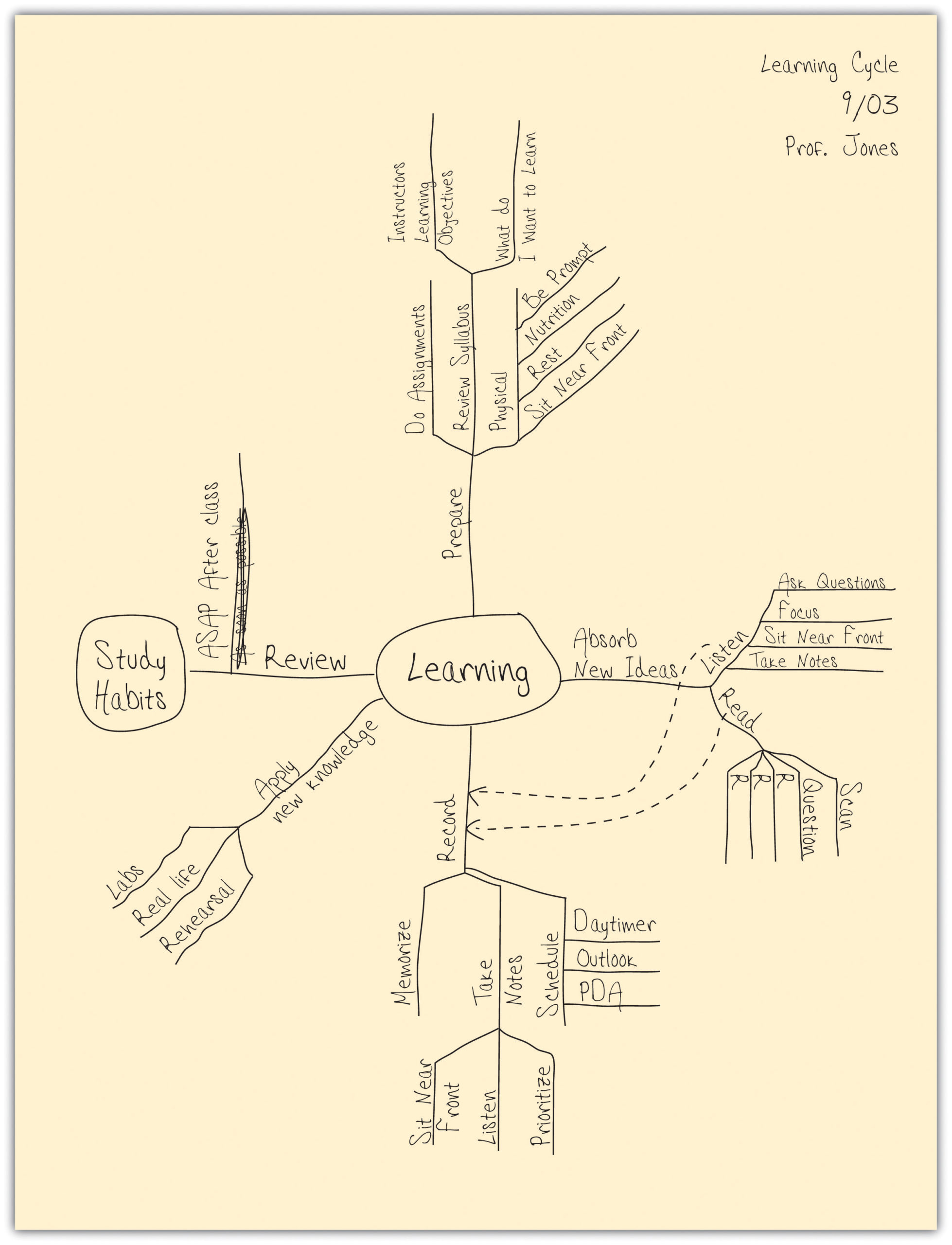

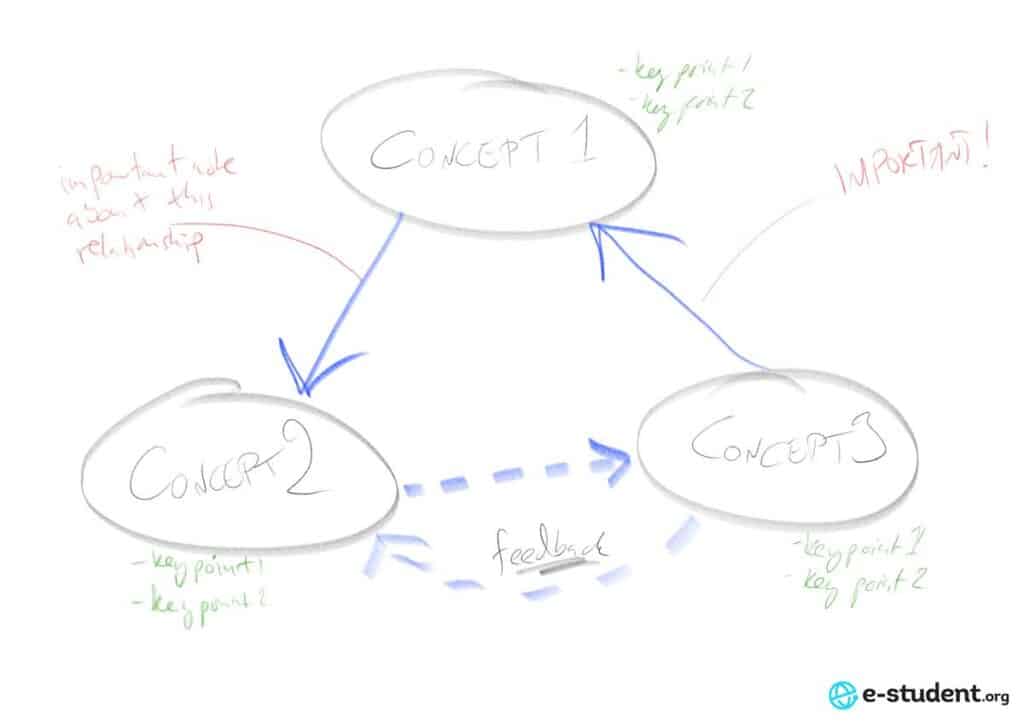

The mapping note-taking method starts with the central idea in the middle of the page, sometimes in a circle. You can write related ideas in smaller circles around the main idea, connected with lines. As you fill in more details, the connections will get more specific, and circles and lines will sprawl along the page, moving from the main idea to small details.

Learning how information should relate to each other can take practice while listening to a lecture in person. You can review your notes later and adjust the position of information on the map to help keep things accurate.

Why use the mapping method

Mapping provides a visual representation of how the material relates to one another. Not only does this make it easier to study later, but it can also help you retain the material.

Another way mapping helps you retain material is that by working through the relationships in real time and paraphrasing what you hear, you are actively engaging with the material. This lets you learn the material as you listen, not simply record what the lecturer says.

6. Flow-based method

Flow-based notes are a concept developed by Scott Young where you write down points of information from the lecture in your own words and connect them visually with arrows. This method of note-taking is similar to the sentence or list method. Still, instead of moving down the paper line by line, you’re drawing connections and representing the material in a visual way to describe relationships. Flow-based note-taking intends to record the material organically as you process it in your head, allowing for a non-linear note system.

Why use the flow-based method

The flow-based method allows you the flexibility to organize information quickly and intuitively. By writing the notes in your own words and demonstrating how they relate to other pieces of information, you will retain more of what you write because of the thought required to rephrase and understand the information.

7. Rapid logging method

Rapid logging, a term often used in connection to bullet journaling, is a method of rapidly capturing information using symbols to organize and add context. For example, you could use one symbol to designate tasks you must complete, another for questions to ask later, and a third for potential exam topics.

Rapid logging aims to note important information without any irrelevant details quickly. Doing so will allow you to capture more information. You can also return to your notes later to add context.

Why rapid logging works

Rapid logging is straightforward and flexible, allowing you to design whatever symbols you need to help you distinguish between different types of information, and you can start taking notes without setting up your notes with any formatting. One of the most significant advantages of rapid logging is that you can use it for any note-taking setting, whether taking notes during a lecture, setting up a day planner, or keeping a personal journal.

Benefits of taking good notes

Taking good notes can help you in a lot of different ways. You record what was discussed when you take notes during a lecture or conference. Reviewing your notes after class helps you retain more information from the lecture and can serve as the beginning of a study guide or material to review for an exam.

Effective note-taking methods can also help you pay better attention in class. Taking notes can help you focus on what’s being said and makes you less likely to daydream or let your thoughts wander. When you take practical notes with a note-taking system, you will save time when you return to your notes to study later because it will be easier to understand what you’ve written and the lecture's main points.

Another benefit of taking good notes is that you have a place to jot down ideas, questions, and connections that come into your head while listening to the lecture. These ideas can be fleeting, but your note-taking method can help you capture them.

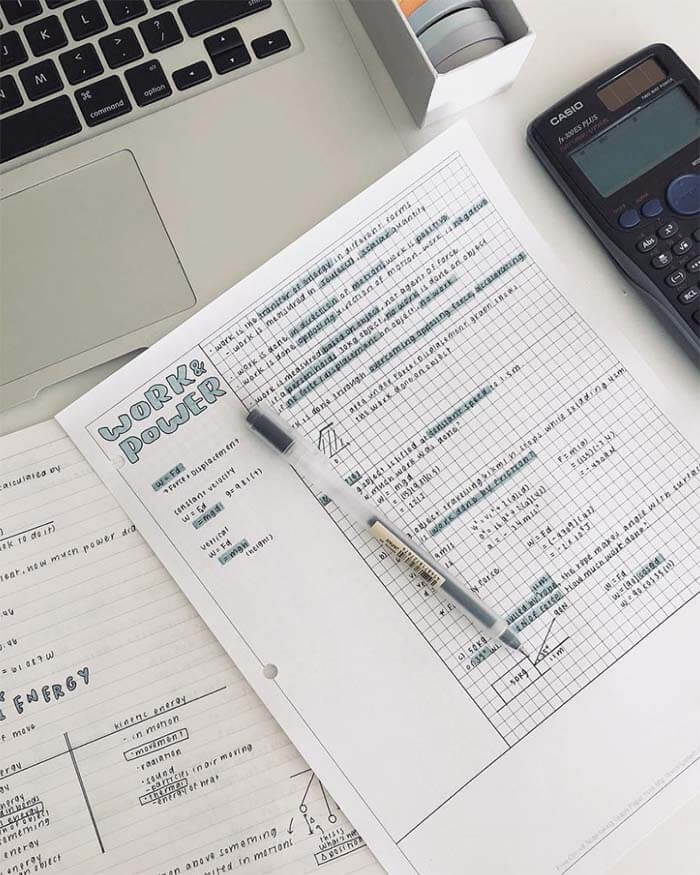

Paper vs. digital note-taking

You can use the analog method of scratching a pen or pencil across paper or use technology to take your notes digitally. Let’s examine the pros and cons of traditional and digital paper note-taking methods.

Paper notes

One of the most significant advantages of using pen and paper to write notes is that you'll retain more information. Writing notes by hand causes us to think more closely about what we are doing because we are more engaged in creating words, funneling the lecture's message through our minds. Paper notes also eliminate distractions that come from digital devices. You won’t have any notifications or emails on your notepad to take you away from the lecture.

Another benefit to paper notes is that it can be faster and easier to create diagrams or other visual ways of organizing information. Although you could achieve the same effect with technology, such as a tablet with a stylus, paper notes are an inexpensive alternative.

Digital notes

Digital notes are an attractive option because typing is faster than writing notes by hand, allowing you to capture more information from the lecture you’re listening to. Typing notes on a computer also lets you edit your notes easily to add more information, organize the information, or create a study guide. However, the formatting capabilities of your word processor might limit you.

Learn more with Coursera

If you’re ready to take the next step, consider Academic Listening and Note-Taking , a course to help you learn note-taking strategies. Another option, the Academic Skills for University Success Specialization from the University of Sydney, helps you further build skills for success. Both are available on Coursera, along with a catalog of courses from globally-renowned institutions.

Keep reading

Coursera staff.

Editorial Team

Coursera’s editorial team is comprised of highly experienced professional editors, writers, and fact...

This content has been made available for informational purposes only. Learners are advised to conduct additional research to ensure that courses and other credentials pursued meet their personal, professional, and financial goals.

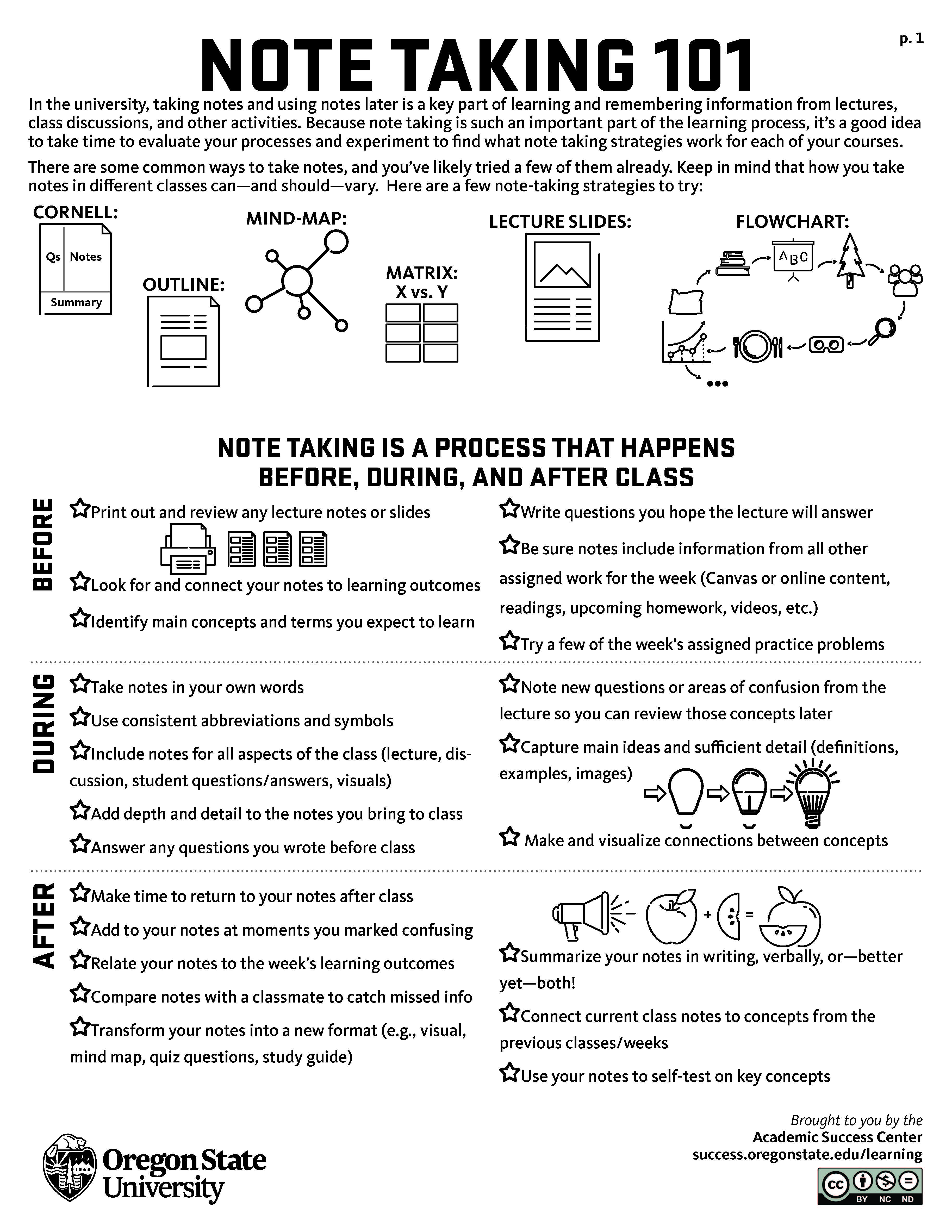

Effective Note-Taking in Class

Do you sometimes struggle to determine what to write down during lectures? Have you ever found yourself wishing you could take better or more effective notes? Whether you are sitting in a lecture hall or watching a lecture online, note-taking in class can be intimidating, but with a few strategic practices, anyone can take clear, effective notes. This handout will discuss the importance of note-taking, qualities of good notes, and tips for becoming a better note-taker.

Why good notes matter

In-class benefits.

Taking good notes in class is an important part of academic success in college. Actively taking notes during class can help you focus and better understand main concepts. In many classes, you may be asked to watch an instructional video before a class discussion. Good note-taking will improve your active listening, comprehension of material, and retention. Taking notes on both synchronous and asynchronous material will help you better remember what you hear and see.

Post-class benefits

After class, good notes are crucial for reviewing and studying class material so that you better understand it and can prepare appropriately for exams. Efficient and concise notes can save you time, energy, and confusion that often results from trying to make sense of disorganized, overwhelming, insufficient, or wordy notes. When watching a video, taking good notes can save you from the hassle of pausing, rewinding, and rewatching large chunks of a lecture. Good notes can provide a great resource for creating outlines and studying.

How to take good notes in class

There’s a lot going on during class, so you may not be able to capture every main concept perfectly, and that’s okay. Part of good note-taking may include going back to your notes after class (ideally within a day or two) to check for clarity and fill in any missing pieces. In fact, doing so can help you better organize your thoughts and to determine what’s most important. With that in mind, it’s important to have good source material.

Preparing to take good notes in class

The first step to taking good notes in class is to come to class prepared. Here are some steps you can take to improve your note-taking before class even begins:

- Preview your text or reading assignments prior to lecture. Previewing allows you to identify main ideas and concepts that will most likely be discussed during the lecture.

- Look at your course syllabus so that you know the topic/focus of the class and what’s going to be important to focus on.

- Briefly review notes from previous class sessions to help you situate the new ideas you’ll learn in this class.

- Keep organized to help you find information more easily later. Title your page with the class name and date. Keep separate notebook sections or notebooks for each class and keep all notes for each class together in one space, in chronological order.

Note-taking during class

Now that you are prepared and organized, what can you do to take good notes while listening to a lecture in class? Here are some practical steps you can try to improve your in-class note-taking:

- If you are seeking conceptual information, focus on the main points the professor makes, rather than copying down the entire presentation or every word the professor says. Remember, if you review your notes after class, you can always fill in any gaps or define words or concepts you didn’t catch in class.

- If you are learning factual information, transcribing most of the lecture verbatim can help with recall for short-answer test questions, but only if you study these notes within 24 hours.

- Record questions and thoughts you have or content that is confusing to you that you want to follow-up on later or ask your professor about.

- Jot down keywords, dates, names, etc. that you can then go back and define or explain later.

- Take visually clear, concise, organized, and structured notes so that they are easy to read and make sense to you later. See different formats of notes below for ideas.

- If you want your notes to be concise and brief, use abbreviations and symbols. Write in bullets and phrases instead of complete sentences. This will help your mind and hand to stay fresh during class and will help you access things easier and quicker after class. It will also help you focus on the main concepts.

- Be consistent with your structure. Pick a format that works for you and stick with it so that your notes are structured the same way each day.

- For online lectures, follow the above steps to help you effectively manage your study time. Once you’ve watched the lecture in its entirety, use the rewind feature to plug in any major gaps in your notes. Take notes of the timestamps of any parts of the lecture you want to revisit later.

Determining what’s important enough to write down

You may be asking yourself how you can identify the main points of a lecture. Here are some tips for recognizing the most important points in a lecture:

- Introductory remarks often include summaries of overviews of main points.

- Listen for signal words/phrases like, “There are four main…” or “To sum up…” or “A major reason why…”

- Repeated words or concepts are often important.

- Non-verbal cues like pointing, gestures, or a vocal emphasis on certain words, etc. can indicate important points.

- Final remarks often provide a summary of the important points of the lecture.

- Consider watching online lectures in real time. Watching the lecture for the first time without pausing or rewinding can help force you to focus on what’s important enough to write down.

Different formats for notes

There is no right format to use when taking notes. Rather, there are many different structures and styles that can be used. What’s important is that you find a method that works for you and encourages the use of good note-taking qualities and stick with it. Here are a few types of formats that you may want to experiment with:

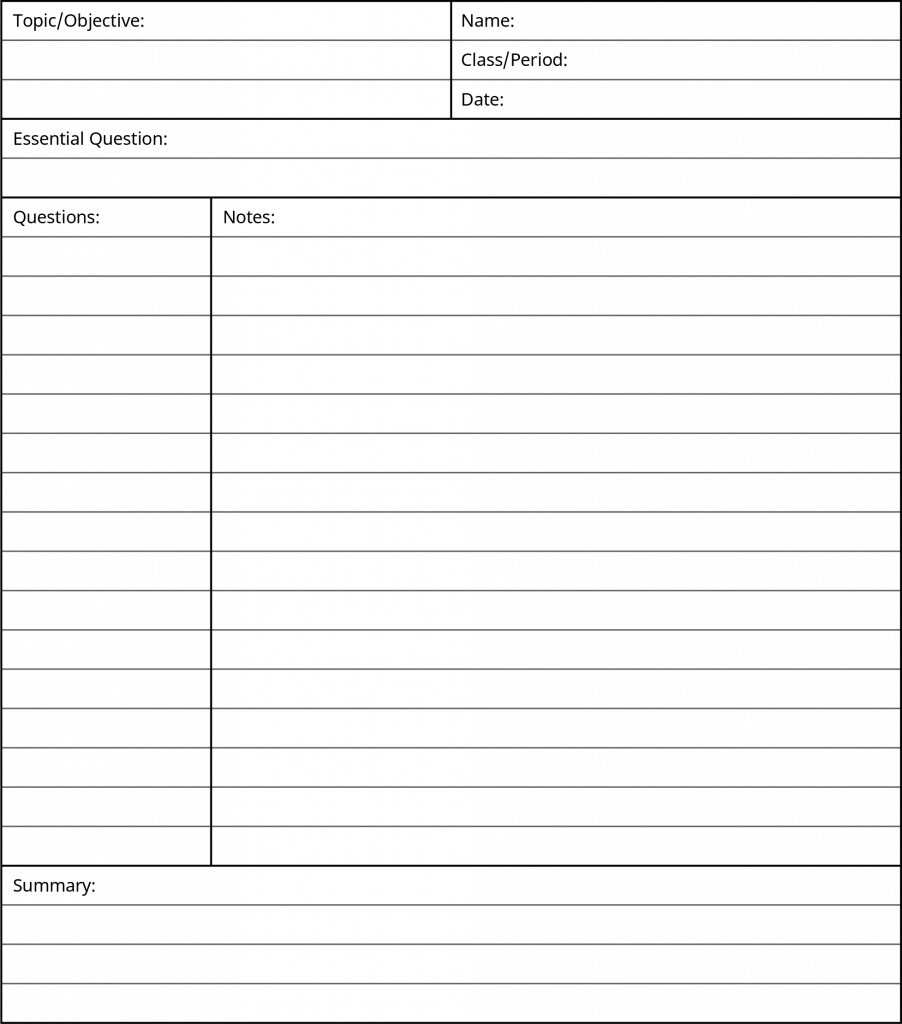

1. Cornell Notes: This style includes sections for the date, essential question, topic, notes, questions, and a summary. Check out this link for more explanation.

2. Outline: An outline organizes the lecture by main points, allowing room for examples and details.

3. Flowchart/concept map: A visual representation of notes is good for content that has an order or steps involved. See more about concept mapping here .

4. Charting Method : A way to organize notes from lectures with a substantial amount of facts through dividing key topics into columns and recording facts underneath.

5. Sentence Method : One of the simplest forms of note taking, helpful for disseminating which information from a lecture is important by quickly covering details and information.

Consider…what’s the best strategy for you: handwritten, digital, or both?

Taking notes in a way to fully understand all information presented conceptually and factually may differ between students. For instance, working memory, or the ability to process and manipulate information in-the-moment, is often involved in transcribing lecture notes, which is best done digitally; but there are individual differences in working memory processes that may affect which method works best for you. Research suggests that handwriting notes can help us learn and remember conceptual items better than digital notes. However, there are some pros to typing notes on a computer as well, including speed and storage. Consider these differences before deciding what is best for you.

Follow up after class

Part of good note-taking includes revisiting your notes a day or so after class. During this time, check for clarity, fill in definitions of key terms, organize, and figure out any concepts you may have missed or not fully understood in class. Figure out what may be missing and what you may need to add or even ask about. If your lecture is recorded, you may be able to take advantage of the captions to review.

Many times, even after taking good notes, you will need to utilize other resources in order to review, solidify, question, and follow-up with the class. Don’t forget to use the resources available to you, which can only enhance your note-taking. These resources include:

- Office Hours : Make an appointment with your professor or TA to ask questions about concepts in class that confused you.

- Academic Coaching : Make an appointment with an Academic Coach at the Learning Center to discuss your note-taking one-on-one, brainstorm other strategies, and discuss how to use your notes to study better.

- Learning Center resources : The Learning Center has many other handouts about related topics, like studying and making the most of lectures. Check out some of these handouts and videos to get ideas to improve other areas of your academics.

- Reviewing your notes : Write a summary of your notes in your own words, write questions about your notes, fill in areas, or chunk them into categories or sections.

- Self-testing : Use your notes to make a study guide and self-test to prepare for exams.

Works consulted

“The Pen is Mightier Than the Keyboard: Advantages of Longhand Over Laptop Note Taking.” Mueller, P., and Oppenheimer, D. Psychological Science 25(6), April 2014.

“Note-taking With Computers: Exploring Alternative Strategies for Improved Recall.” Bui, D.C., Myerson, J., and Hale, S. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(299-309), 2013.

“How To Take Study Notes: 5 Effective Note Taking Methods.” Oxford Learning. Retrieved from https://www.oxfordlearning.com/5-effective-note-taking-methods/

“Preparing for Taking Notes.” The Pennsylvania State University. Retrieved from http://tutorials.istudy.psu.edu/notetaking/notetaking2.html

“Listening Note Taking Strategies.” UNSW Sydney. Retrieved from https://student.unsw.edu.au/note-taking-skills

“Note Taking and In-Class Skills.” Virginia Tech University. Retrieved from https://www.ucc.vt.edu/academic_support/study_skills_information/note_taking_and_in-class_skills.html

“Lecture Note Taking.” College of Saint Benedict, Saint John’s University. Retrieved from https://www.csbsju.edu/academic-advising/study-skills-guide/lecture-note-taking

“Note Taking 101.” Oregon State University. Retrieved from http://success.oregonstate.edu/learning/note-taking-tips

“Note Taking. Why Should I Take Notes in Class?” Willamette University. Retrieved from http://willamette.edu/offices/lcenter/resources/study_strategies/notes.html

If you enjoy using our handouts, we appreciate contributions of acknowledgement.

Make a Gift

- Utility Menu

- ARC Scheduler

- Student Employment

- Note-taking

Think about how you take notes during class. Do you use a specific system? Do you feel that system is working for you? What could be improved? How might taking notes during a lecture, section, or seminar be different online versus in the classroom?

Adjust how you take notes during synchronous vs. asynchronous learning (slightly) .

First, let’s distinguish between synchronous and asynchronous instruction. Synchronous classes are live with the instructor and students together, and asynchronous instruction is material recorded by the professor for viewing by students at another time. Sometimes asynchronous instruction may include a recording of a live Zoom session with the instructor and students.

With this distinction in mind, here are some tips on how to take notes during both types of instruction:

Taking notes during live classes (synchronous instruction).

Taking notes when watching recorded classes (asynchronous instruction)., check in with yourself., if available, annotate lecture slides during lecture., consider writing notes by hand., review your notes., write down questions..

Below are some common and effective note-taking techniques:

Cornell Notes

If you are looking for help with using some of the tips and techniques described above, come to the ARC’s note-taking workshop, offered several times every semester.

Register for ARC Workshops

Accordion style.

- Assessing Your Understanding

- Building Your Academic Support System

- Common Class Norms

- Effective Learning Practices

- First-Year Students

- How to Prepare for Class

- Interacting with Instructors

- Know and Honor Your Priorities

- Memory and Attention

- Minimizing Zoom Fatigue

- Office Hours

- Perfectionism

- Scheduling Time

- Senior Theses

- Study Groups

- Tackling STEM Courses

- Test Anxiety

How to take good notes (and how NOT to!)

Learn how to finally take smarter notes. These 8 note-taking strategies will help you to truly master your subject, prepare for your exams, and save hours of study time.

It’s a race against time.

The projector’s light burns brightly against the canvas as the lecturer paces back and forth, the PowerPoint clicker clutched in hand, words spilling from his mouth faster than you can follow them. The lecture hall is hushed, your fellow students bent low to their pages, furiously writing, copying down the information on the slide.

The clock is ticking.

Sweat beads across your forehead—the slide has been up for a whole minute now. Any second, the lecturer is going to raise that clicker and skip to the next slide. But you’re not done yet. Time is running out. You grit your teeth, pen flying furiously across the page of your notebook. Almost finished ... almos—CLICK!

“And as we see on this next slide”

There is hardly a student under the sun who cannot relate to this dramatization. We put so much pressure on ourselves to capture in writing everything our educators tell us and show us that we forget to do the most important thing of all:

Hear what they are saying.

The result is that you walk out of the classroom with next to NO recollection of the lesson.

Sure, you’ll have your notes (which look like they were written by a spider that fell in an inkwell and staggered across the page), but you’ll only look at those again when the next test or exam comes your way. And by that point, you’ll struggle to make head or tail of them.

We’re here to change that.

The team here at Brainscape has spent over a decade rigorously asking ourselves, the scientific literature, and our millions of users what it takes to learn efficiently, comfortably, and conveniently.

What we have discovered has become the foundation and framework of our awesome web and mobile flashcard app , which applies tried-and-tested cognitive learning principles to help students prepare for high stakes exams.

It has also taught us that note-taking is one of the primary tenets of education . Note-taking can vastly improve student learning . Yet, most students have been doing it wrong .

This doesn’t have to be the case.

By taking your focus off the notebook in front of you and returning your attention to your lecturer, you can spend more time learning in class and less time relearning everything from scratch when exam time comes.

So the Brainscape team put our heads together, geeked out on what science has to say, and came up with this super helpful guide on how to take notes well (and how not to), which we now offer to you to help you succeed.

Let’s jump right in!

The secret for how to take notes well: preparation

As students, we think the best way to take notes in class is to be thorough. The more the better . But the tragedy is, for all your efforts, this way of recording information is just not benefiting you as it should. In fact, it’s handicapping you.

While you’re so busy writing everything down, you’re missing out on:

- Engaging in the lecture,

- Hearing what your teacher is saying,

- Processing the information, and

- Asking questions about what’s unclear to you.

This is what genuine learning looks like: listening and engaging in class . The missing link in facilitating this ... is preparation .

Preparing for class beforehand is a fundamental step that almost all students are missing in their note-taking approach.

Okay, so nobody actually reads the textbook before class. But you can!

In other words, the ironic secret to taking better notes isn't as much what you do in class as what you do before it.

Reading the relevant section or chapter before class:

- Fundamentally takes the pressure off of you to write everything down during the lecture,

- Alerts you to what information is to come, which primes your brain for learning,

- Contributes enormously towards your ability to understand the information presented in the lecture,

- Frees up your concentration and focus , which you can now direct at the lecturer and to asking questions,

- Deepens the memories you make of the information, and

- Saves you hours of time later on.

With this preparation done, you can walk into class primed to learn and fully equipped to sit back, listen, engage, and only take notes when needed . Keep reading for a step-by-step on how to best prepare for class.

Use these 8 steps to learn how to take notes

“By failing to prepare, you are preparing to fail.” ― Benjamin Franklin (and he’s on the $100 bill so he knows what he’s talking about)

We have 8 steps for effective note-taking strategies. The first four steps are all about how to best prepare and make the most out of your class:

- Step 1: Review the previous lesson

- Step 2: Read through the new material

- Step 3: Write down any questions you might have

- Step 4: Make preliminary notes before class

Step 1. Review the previous lesson

In most subjects, the concepts you learn today logically support the concepts you learn tomorrow. If you don’t know what the heck is going on, anything new you’re exposed to isn’t going to have a framework to fit into, which makes remembering it so much harder.

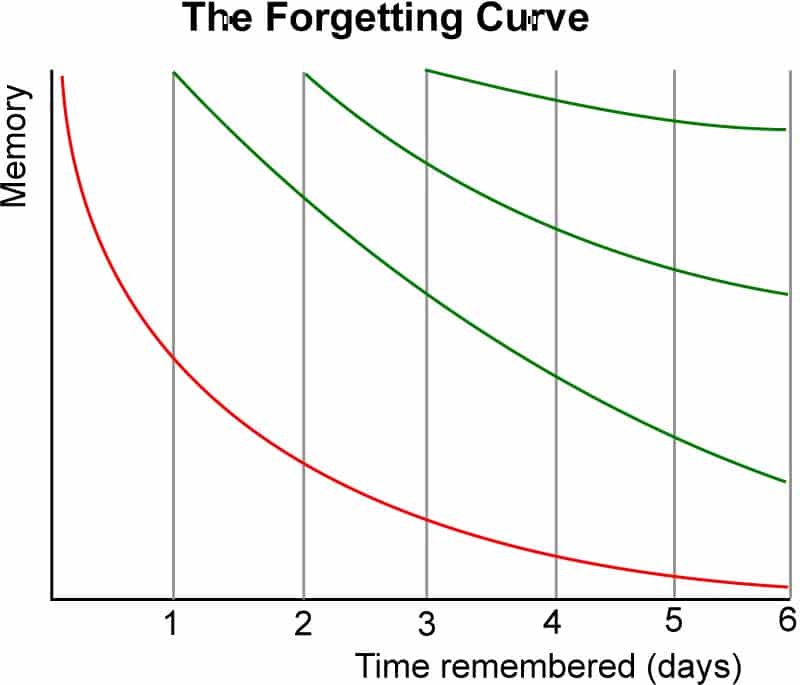

Ergo, by reviewing the previous lesson’s notes, you (1) reinforce the information you learned (which is critically important ) and (2) provide a stable foundation for the new information you’ll be exposed to today.

It’s kind of like reading the previous page of a novel to remind yourself of what’s going on in the story before reading on.

Step 2. Skim through the new material

Being primed to learn makes your brain receptive to new information. So, read through the sections your lecturer intends to cover in the next lesson before you arrive for class.

Reading ahead in the textbook takes new information you need time to process, and makes it familiar. Then, in class, you can focus on consolidating that information and filling in the gaps.

This may feel super nerdy. Who reads the textbook before class? But think about it. You're gonna have to eventually read the chapter anyway . If reading it before the lecture is so much more effective, why not do it in this order?!

The idea here is not to memorize or become 100% confident in the material but rather to establish:

- A high-level view of what’s to come,

- A preliminary understanding of the chapter’s key concepts, and

- An idea of the concepts you might struggle with.

It also makes you curious to fill in the gaps ... and a curious student is an engaged student!

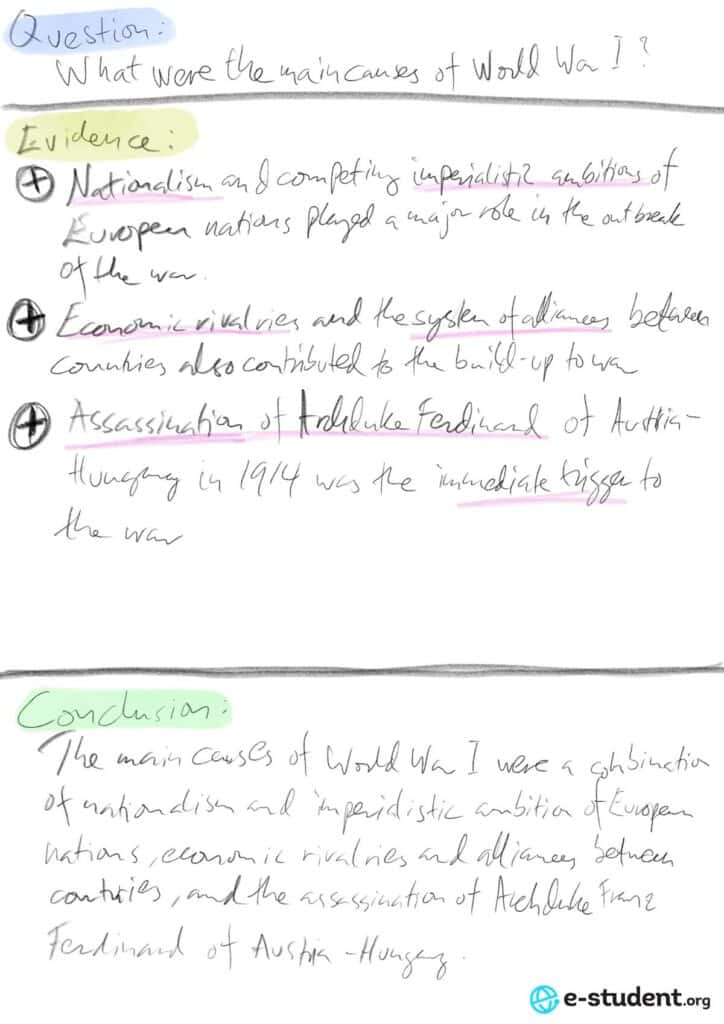

Step 3. Write down any questions you might have

Once you’ve finished reading the chapter, think about some questions you should ask to bridge any gaps in your understanding.

For example: let’s say you’ve read a chapter on thunderstorms, and you mostly understand the atmospheric requirements for their formation. But cloud electrification makes you say "DOH!" harder than Homer Simpson. You might write the following questions:

- How do particles within a cloud become positively and negatively charged?

- Why do the positive ions travel upwards while the negative ions travel earthwards?

- Do people who play golf in thunderstorms have a lower-than-average IQ?

Simply jotting these specific questions down awakens your powers of metacognition.

Oooh, aaah.

Metacognition is your awareness and understanding of your own thought processes and using it prompts your brain to form deeper memory traces .

In your head, it might sound a little like this: “Do I fully understand this concept? Or could I use some clarity on a few points?”

This type of inquiry encourages engagement in class and puts your brain into problem-solving mode , both of which are powerful for learning and remembering. And this takes the pressure off the note-taking in class, since you’ll already know the information your lecturer will be presenting.

Step 4. Make preliminary notes before class

Now your task is to create your own chapter outline with preliminary notes from the textbook. The idea is to have the basic structure of the chapter with its main concepts laid out in logical connection with one another, leaving plenty of space for you to write down additional information in class.

Keep this summary succinct and with only the key points, concepts, and definitions from the chapter written down. Anything time-consuming is probably going to deter you from doing this all-important prep work so keep it concise! You can go into greater detail where your understanding falters and you may require richer explanations.

With your preparation done, we will now address how to take good notes during and after class with the following four steps …

- Step 5: Note-taking in class

- Step 6: Consolidate the material

- Step 7: Transform the salient concepts into flashcards

- Step 8: Reframing content as concept maps

Step 5. Note-taking in class

With your preliminary notes done, you can focus on the lecture, using the spaces you’ve left to flesh out the information rather than writing everything from scratch. Just remember to remain calm and keep your perspective on the material so that you don’t slip back into your old habits.

Also, keep a record in the margin of your page of the most important points so that you can turn these into flashcards later (more on this in a moment!).

Pro Tip: If the information in a particular lecture is super important, or the course you’re taking critical to your overall education, you could even use your device to make an audio or even video recording of it. This frees you up to pay total attention in class rather than writing down notes.

But, be SUPER sparing with this technique . It has the nasty habit of making students lazy and seducing them to put off the necessary preparation and consolidation work until right before the exam. It can also be time-consuming working through 23 hours of audio/video content! Like people who take videos of fireworks displays, you might both miss the moment and then never look at the video again.

Step 6. Consolidate the material

Before the lecture (with your preparation work) you were introduced to the chapter’s concepts for the first time. During the lecture, these concepts were reinforced and expanded upon. Now, after the lecture—ideally within 24 hours of it—you should sit down with your notes and combine everything you have into Version 2.0: your new, improved, and rewritten sexy study notes!

This consolidation of your study notes after class strengthens the memory traces you’ve created in your brain, while also helping you to understand the section’s most important concepts and paraphrase them in your own words . It also leaves you with a valuable learning asset, which you can use for studying for tests and exams!

Step 7. Transform the salient concepts into flashcards

What you really need to do after taking notes is to transform them into a format that you can actively study later. And this is best done by turning the material’s salient points into Cue/Target pairs (i.e. Question/Answer card), which you can review in a custom pattern based on how well you know each one.

That’s right: we’re talking about flashcards . And, naturally, flashcards are Brainscape’s favorite study tool!

Flashcards have been used for centuries by serious students to efficiently learn knowledge-intensive subjects, from biology, science, and medicine to history, law, and language.

What flashcards essentially do is break subjects up into their fundamental (and manageable) bite-sized facts, making them much easier to digest. They also leverage your brain's innate wiring to help you absorb information by engaging:

- Active recall: Thinking of the answer from scratch rather than passively reading through your notes or textbook,

- Spaced repetition: Repeating your exposure to the information in order to better memorize it.

- Metacognition: Assessing the strength of your knowledge as you go.

Decades of cognitive science research and thousands of academic studies prove this method's effectiveness.

[ Use Brainscape to start studying with flashcards ]

Just remember , no matter how great the flashcard tool you use—and Brainscape is pretty great—if you didn't first record and consolidate your notes effectively, you may be missing the key content that’s likely to be on your exam!

Step 8. Reframing content as concept maps

Finally, if your subject is riddled with complex, interrelated topics, it might also make sense to transform the content into a mind map or concept map. These are useful, adjunctive tools for consolidating information presented in your textbook and in class. And they have the added benefit of engaging your critical thinking skills, which form more permanent, long-term memories.

BUT while concept maps are great exercises to consolidate notes after the lecture , they are not the best format for studying that information later on. Similar to reading a textbook, simply staring at a concept map only engages your brain on a passive level and doesn’t establish any strong, meaningful connections to that information. This tends to form shallow memories that disappear quickly.

Flashcards, on the other hand, compel you to actively recall information (by answering questions) and repeat difficult concepts to you more often, which, as we have explained, establishes deeper memory traces.

So, be cautioned: making concept maps can be a useful tool, but if you think that continually reviewing them will help you prepare effectively for your exam, you might be making a version of the #1 biggest studying mistake !

What about the Cornell Method of note-taking?

Most resources that dive into how to take good notes mention the “ Cornell Method ”: a systematic format for condensing and organizing notes designed for high school or college level students. Very briefly, the Cornell Method pivots on the same approach we have discussed in this article (record, question, recite, reflect, and review) but requires students to divide their page into two columns with keywords and questions on the left and discussion on the right.

You can also combine this with the visual icons for deeper learning.

The Outline Method is another popular note-taking strategy (also for college-level students). An outline naturally organizes the information in a highly structured, logical manner, forming a skeleton of the subject. This can later serve as an excellent study guide when preparing for exams.

Which note-taking method works the best? Quite simply: the one that works for you . Nowadays, most of us tend to take our notes digitally anyway (e.g. in a Google doc), so it's increasingly easy to move your notes around or turn them into an outline after the fact, rather than sweating precisely how we divide a sheet of paper before even beginning to record any information.

Writing smarter (not harder): a summary

Now you know how to take notes the right way; follow these steps:

- Step 1: Remind yourself what you learned the day before

All of this—the pre-reading, preliminary note-taking, jotting down of questions, information consolidation, and flashcard-making—may sound like a lot of extra work .

It is the work you should be doing to (1) truly master your subject, (2) prepare for your exams throughout the semester, and (3) save yourself hours of study time later on, not to mention the anxiety that comes with cramming an entire semester’s worth of information into a few days or weeks.

The note-taking approach we have outlined in this guide sets the excellent students apart from the mediocre ones, who have only average results and a nasty case of carpal tunnel to show for their efforts. So, go forth and write smarter (and not harder) with our eight steps on how to take good notes!

Chang, W. & Ku, Y. (2014). The effects of note-taking skills instruction on elementary students’ reading. The Journal of Educational Research, 108 (4), 278–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2014.886175

Kiewra, K. A. (2002). How classroom teachers can help students learn and teach them how to learn. Theory Into Practice, 41 (2), 71-80. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4102_3

Rahmani, M. & Sadeghi, K. (2011). Effects of note-taking training on reading comprehension and recall. The Reading Matrix, 11 (2). https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/85a8/f016516e61de663ac9413d9bec58fa07bccd.pdf

Flashcards for serious learners .

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Linda Clark and Charlene Jackson

Introduction

Notetaking and reading are two compatible skill sets. Beyond providing a record of the information you are reading or hearing, notes help you make meaning out of unfamiliar content. Well-written notes help you organise your thoughts, enhance your memory, and participate in class discussion, and they prepare you to respond successfully in exams. This chapter will provide you with guidelines for understanding your purpose for taking notes, and steps for taking notes before, during and after class. Then, a summary of different notetaking strategies will be provided so that you can choose the best method for your learning style. Finally, you will discover ways to annotate your notes to enable quick reference, along with information about taking notes specifically for assignments.

Understanding Your Purpose for Learning

Knowing your course requirements and the intended purpose for your notes should impact the type of notes you take. For example, are you:

- taking lecture notes that will become the basis of exam study?

- taking notes while watching your classes online?

- taking notes from books or articles for an assignment?

There are no right or wrong ways to take notes, but it is important to find strategies that work for you and are efficient for your purpose.

Taking Notes from Classes

Whether you are attending classes on campus or are studying online, it is still important to take notes from your lectures. Notes help you keep up with the content each week which in turn helps you prepare for your exams. There are things you should consider before, during and after your lectures to assist with your notetaking.

Before the class

In some courses the weekly class content is available before the lecture as PowerPoint slides. This may make it tempting not to take notes, however these slides usually only have key points. Further details and explanations are given verbally in the class. A good tip is to print the PowerPoint slides before the lecture and use them as the basis for your note taking. If you select the three slides per page from the print options, it will give you room to take some notes. Come to lectures prepared by completing any set reading or tasks for that week. This will help you understand the content and more easily make decisions about what relevant notes to take.

During the class

Take notes to actively engage in the process of learning. This will help with concentration. Handwriting your notes has been proven to increase memory and retention. Do not try to write down every word or you will miss important information. Keep your notes brief, use keywords, short sentences and meaningful abbreviations.

Most lectures are recorded so you can go back and check for anything you missed. It is a good idea also to leave plenty of space for these thoughts, or for adding in pictures or diagrams. Pay attention to the structure or organisational pattern of the lecture. Key points are usually outlined at the beginning of the lecture, and repeated or summarised at the end. Listen for language cues emphasising important information including:

- numerical lists, e.g. “firstly…, secondly”, “there are three steps/stages…”

- phrases such as “on the other hand”, “in particular”, “remember/note/look out for”, “consequently”

- inclusion of examples or hypothetical situations

- emphasis of a particular point through tone of voice

If you do not understand the content, make a note or write a question and follow this up in your tutorial or discussion forum.

After the class

It is important that you re-read your notes as soon as possible after the class, when the content is still fresh in your mind, and make any additions. If you have exams in your course, then it is important to spend time organising your notes throughout the semester. This will ensure that by the end of the semester you will have well-ordered notes that are meaningful and useful to learn from, saving you valuable exam preparation time. Your learning preference will inform the review strategies you choose.

Notetaking Strategies

There are several different notetaking strategies. Regardless of your method, be sure to keep your notes organised, store notes from the same subject together in one place, and clearly label each batch of notes with subject, source and date taken. Here are three notetaking strategies you can try; Cornell Method, linear notes and concept mapping.

Cornell Method

One of the most recognisable notetaking systems is called the Cornell Method. In this system, divide a piece of paper into three sections: the summary area, the questions column and the notes column (see Figure 16.3 ). The Cornell Method provides you with a well-organised set of notes that will help you study and review your notes as you move through the course. If you are taking notes on your computer, you can still use the Cornell Method in Word or Excel.

The righ t-hand notes c olumn: Use this section to record in your own words the main points and concepts of the lecture. Skip lines between each idea in this column and use bullet points or phrases. After your notetaking session, read over your notes column and fill in any details you missed in class.

In the questions c olumn : Write any one or two-word key ideas from the corresponding notes column. These keywords serve as cues to help you remember the detailed information you recorded in the ‘notes’ column.

The summary area: Summarise this page of notes in two or three sentences using the summary area at the bottom of the sheet. Before you move on, read the large notes column, and quiz yourself over the key ideas you recorded in the questions column. This review process will help your memory make the connections between your notes, your textbook reading, your in-class work, and assignments.

The main advantage of the Cornell Method is that you are setting yourself up to have organised, workable notes. This method is a useful strategy to organise your notes for exam preparation.

Linear notes

A common format for note taking is a linear style – using numbers or letters to indicate connections between concepts. Indicate the hierarchy of ideas by using headings, written in capitals, underlined or highlighted in some way. Within concepts, ideas can be differentiated by dot points, or some other indicator, to create an outline that makes the notes easier to read. The main benefit of an outline is its organisation.

The following formal outline example shows the basic pattern:

Notetaking can continue with this sort of numbering and indenting format to show the connections between main ideas, concepts and supporting details.

Con cept mapping

One final notetaking method that appeals to learners who prefer a visual representation of notes is called mapping or sometimes mind mapping or concept mapping . The basic principles are that you are making connections between main ideas through a graphic depiction. Main ideas can be circled, with supporting concepts radiating from these ideas, shown with a connecting line and possibly details of the support further radiating from the concepts. You may add pictures to your notes for clarity.

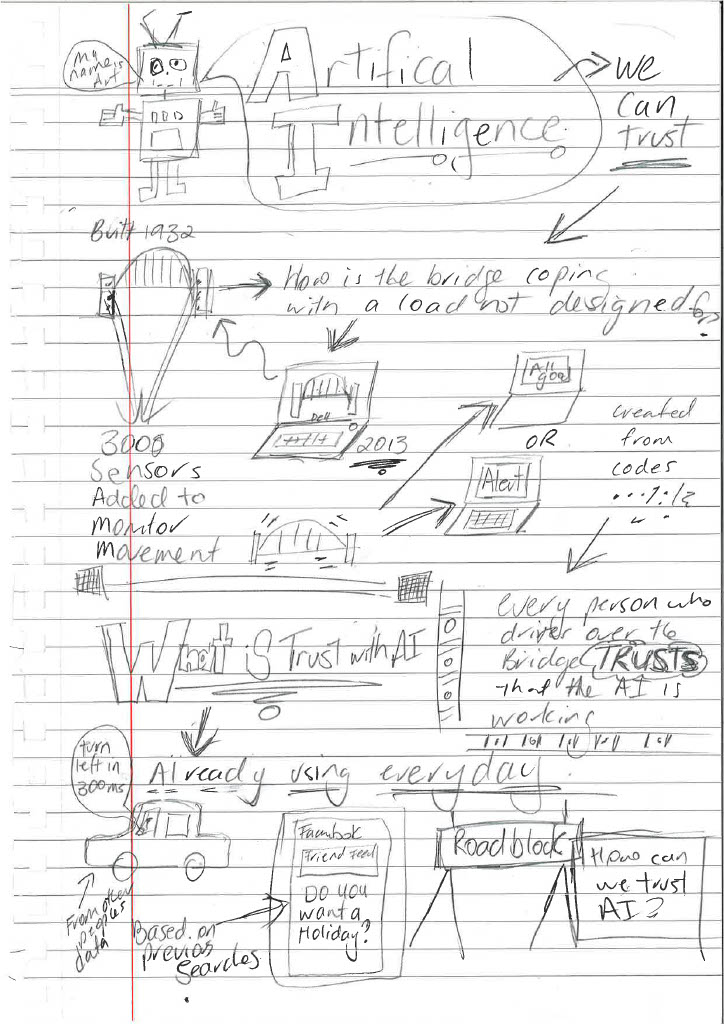

Sketchnoting

Sketchnoting differs from concept mapping. Concept maps use a hierarchical structure and consist primarily of text with a focus on one main theme, and show the connections between ideas related to that theme. Sketch notes have a picture focus using a flexible layout and can cover one or a range of themes. (See Figure 16.6 )

Sketchnoting is a personalised way of combining words with visual elements such as drawings, icons, shapes and lines. This style of notetaking is used by students to maintain engagement, enhance understanding, and to retain information from verbal or written content. The sketchnoting technique is used to organise ideas and summarise content in a meaningful way to help the notetaker recall the information at a later date. Sketchnoting can be created digitally or using pen and paper. You can choose your style and preference.

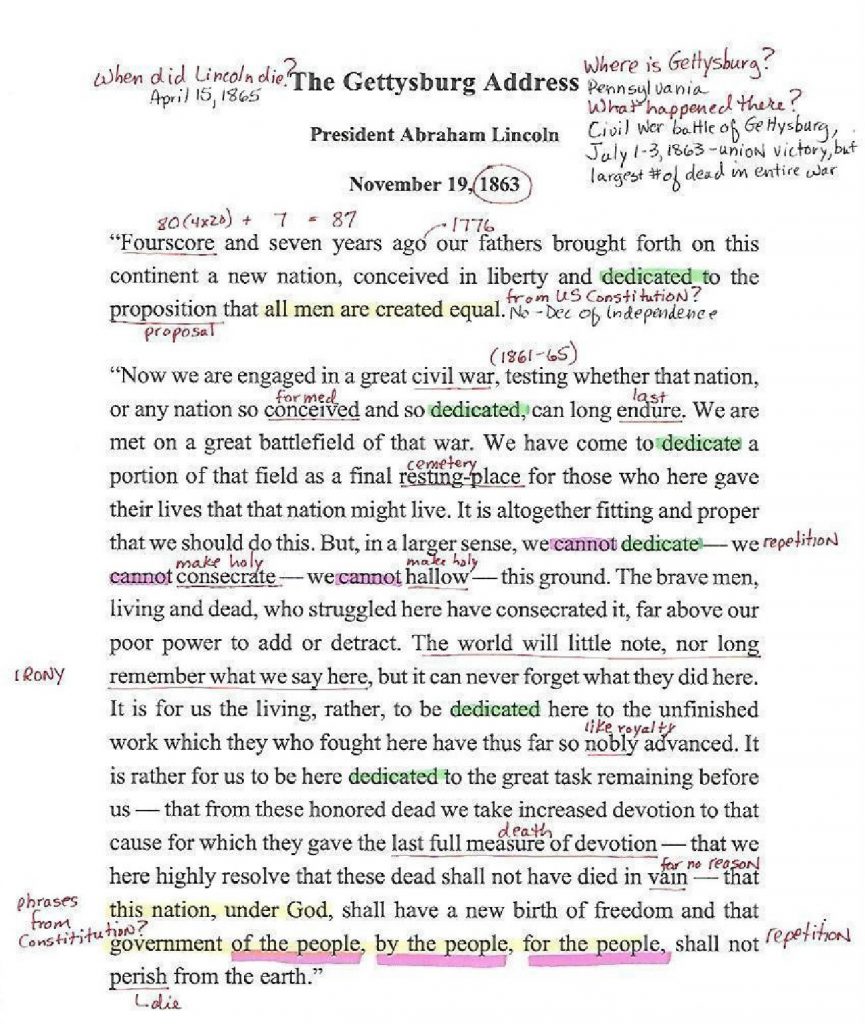

Annotating notes

Annotations can refer to anything you do with a text to enhance it for your particular use (either a printed text, handwritten notes, or other sort of document you are using to learn concepts). The annotations may include highlighting passages or vocabulary, defining those unfamiliar terms once you look them up, writing questions in the margin of a book and underlining or circling key terms for future reference. You can also annotate some electronic texts.

Your mantra for highlighting text should be less is more. Always read your text selection first before you start highlighting anything. You need to know what the overall message is before you start placing emphasis in the text with highlighting. Another way to annotate notes after initial notetaking is underlining significant words or passages.

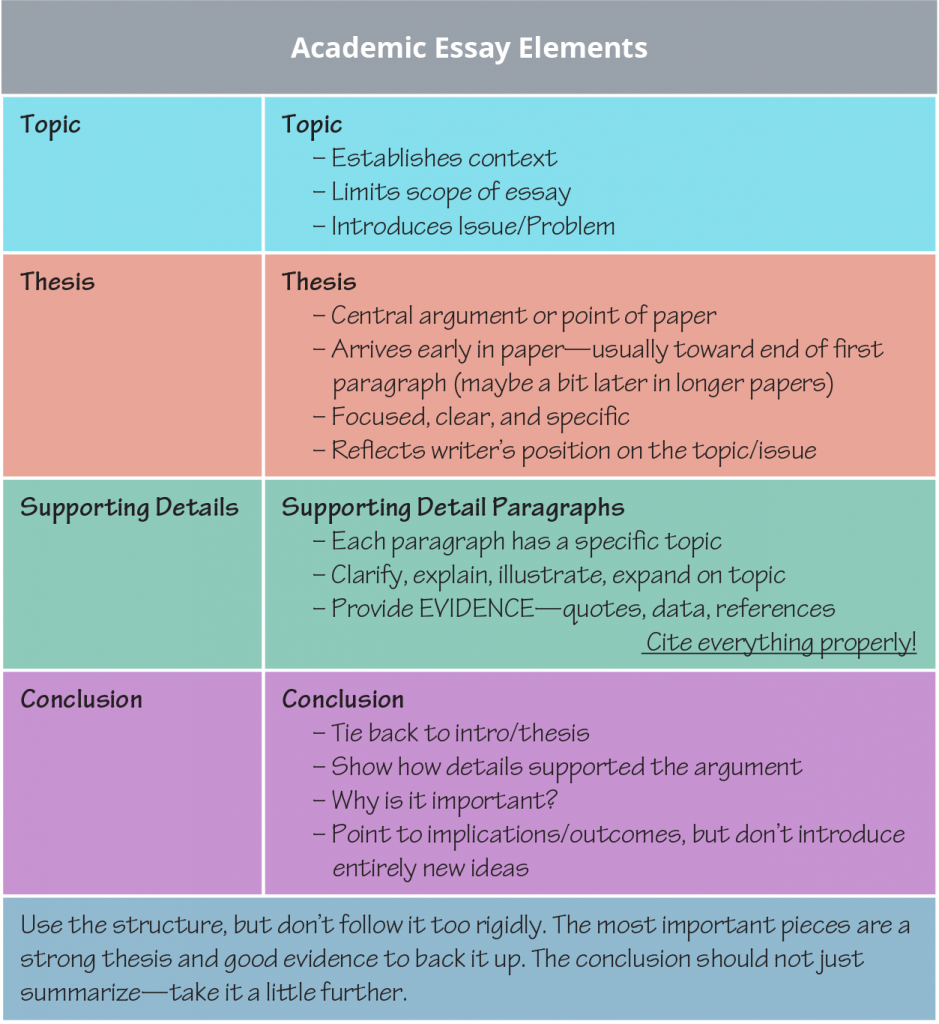

Taking notes for assignments

When taking notes for an assignment, be clear whether they are your own words, or a direct quote so that you do not accidentally plagiarise. When you have finished taking notes, look for key themes or ideas and highlight them in different colours. This organises your information and helps you to see what evidence you have to support various ideas you wish to make in your assignment. Make sure to record the author, title, date, publishing details and relevant page numbers of books and articles you use. This will save you time and avoid errors when referencing.

Electronic Notetaking

If you use an e-reader or e-books to read texts for class or read articles from the internet on your laptop or tablet, you can still take effective notes. Almost all electronic reading platforms allow readers to highlight and underline text. Some devices allow you to add a written text in addition to marking a word or passage that you can collect at the end of your notetaking session. Look into the specific tools for your device and learn how to use the features that allow you to take notes electronically. You can also find apps on devices to help with taking notes. Microsoft’s OneNote, Google Keep, and the Notes feature on phones are relatively easy to use, and you may already have free access to those.

Notetaking is a major element of university studying and learning. As you progress through your study, your notes need to be complete so you can recall the information you learn in lectures. The strategies that have been explored in this chapter will help you to be deliberate in your notetaking.

- Know the purpose for your notes.

- Before the class, print any lecture slides with the notes option.

- During the class, keep your notes brief, use keywords, short sentences and meaningful abbreviations.

- After the class, re-read your notes and organise them.

- The Cornell Method uses a table with a summary area, a questions column and a notes column.

- Linear notetaking uses headings, numbers or letters to show hierarchy and connections between concepts.

- Concept mapping uses graphic depiction to connect ideas.

- Sketchnoting is a creative way to make personalised meaningful notes from written or spoken content.

- Annotating your notes with highlights, underlining, circling or writing in the margin can enhance your understanding.

- Notetaking for assignments must show clearly when the words are your own or are a direct quote. Record the source details for use in referencing.

- Notetaking can be performed by hand or on electronic devices.

Academic Success Copyright © 2021 by Linda Clark and Charlene Jackson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Places on our 2024 summer school are filling fast. Don’t miss out. Enrol now to avoid disappointment

- The best way to write study notes

As a student, it’s likely you’ll have done a lot of note-taking by now. But are your study notes messy, disorganised or confusing to read? If so, it’s probably because you haven’t learned how to write study notes effectively yet.

Writing notes in your own words is one of the best ways to ensure you’ve remembered and understood what your teacher is saying in class or what you’ve read in a textbook.

However, unless your notes are concise, structured and well-organised, it’s unlikely they’ll be much help when it comes to reviewing what you’ve just been taught or revising for an exam.

There are many different ways to take good notes; you just need to find the one that suits you best. In this article, we’ve outlined some of the most popular note-taking methods – which you can try out next time you’re in class.

What’s the best way to write study notes?

There’s no one best way to write study notes, but some of the most popular methods include the Cornell Method, the Outline Method, the Mapping Method, the Flow Notes Method and the Bullet Journaling Method.

Some tips for helping you take effective study notes are to make sure you focus only on the key points and phrases, consider drawing pictures if you’re short on time and remember to clarify anything you don’t understand.

Keep reading to learn more about writing better notes.

Why is it important to take good study notes?

As mentioned above, taking your own notes helps you to remember and understand key topics and concepts much better. This is because:

- You have to think about what you’re writing down

- You’ll be actively listening to what your teacher is saying

- You’re more likely to be able to make connections between topics

- You can review everything you’ve learnt once the class is over

Effective study notes will also make exam time less stressful, as they’ll be really helpful when it comes to revising.

What are some of the different note-taking techniques?

The cornell method.

Created at America’s Cornell University, this note-taking technique has been around for decades.

It’s great for taking structured notes, as you divide your paper up into easily-digestible sections:

- Notes – This is for the notes you take during class, which you can structure however you like, although we recommend the Outline Method (see below).

- Cues – This section can be written during or straight after class. It’s where you fill out the main points or potential exam questions. The words you write should jog your memory, to help you remember bigger ideas.

- Summary – Your summary can be written straight after class or when reviewing your notes. It should be a summary of the whole lecture.

You can also use the Cornell Method for taking revision notes from textbooks. It’s particularly helpful for testing yourself, as you can cover up the notes and summary sections of the page and see how much you can remember from your cues.

The Outline Method

This is one of the easiest ways to take notes, and most people find it comes quite naturally.

It’s useful for learning about detailed topics, as you use headings and bullet points to organise the information straight down the page.

Here’s how to use the Outline Method:

- At the start of each lesson, write a headline for the main topic at the top of the page and underline or highlight it

- As the lesson progresses, write subheadings for each subtopic, indenting them slightly to the right

- List key information underneath each subheading using bullet points

The great thing about this method is that it’ll help you to pay attention to what’s being said. The downside is that reviewing your notes afterwards can be overwhelming. To combat this, you could try highlighting keywords straight after class, so that only the most relevant information stands out.

The Mapping Method

Also called the Mind-Map Method, this note-taking method is ideal for visual learners, and it’s useful for when you’re being taught about the relationships between different topics.

You start by writing the name of the main topic you’re learning about in the middle of your page. Then you write headings for each subtopic branching off the main topic, with important notes underneath each one. You can then have more subtopics branching off each of the previous subtopics, continuing this pattern as needed.

This method is perfect for subjects that have interlocking topics or complex, abstract ideas, for example, history, chemistry and philosophy.

The Chart Method

This is another good technique to use if you’re learning about the relationships between topics, however, it’s really only useful if you know what the topics are before the start of your lesson.

To use it, divide your page into several columns, labelled by category. Then, when your teacher mentions information relating to one of the categories, jot it down in the relevant column.

It’s handy for lessons that cover lots of facts and figures as it enables you to organise information in a way that’s easy to review.

The Sentence Method

If your lessons are fast-paced and cover a great deal of information, you may find this note-taking method helpful.

This is because each time a new topic is introduced, you jot down the main points on a new line. This enables you to cover lots of details quickly and helps you to identify which information is worth writing down.

If you want to organise your notes further, use headings for each main topic.

The Flow Notes Method

Rather than simply transcribing a lesson, the Flow Notes Method allows you to actively learn while you’re writing, so you spend less time reviewing your notes after class.

The aim is to engage with the material in a way that connects with you, from drawing doodles, diagrams and graphs to use your knowledge of other subjects to make connections with what’s being said in your current class.

If you’re an auditory and visual learner with a fantastic memory, you might find that taking notes in this way suits you best, although pairing this technique with Cornell notes can make it easier to revise for exams.

The Writing on Slides Method

Some teachers are kind enough to provide their students with course material before the lesson. If you’re lucky enough to be in this position, use it to your advantage!

By printing off presentation slides beforehand, you can save time by annotating the key concepts that are already there in front of you, instead of frantically trying to keep up with everything that’s being said.

As well as being an easy way to write notes, it’s effective for reviewing and revising too, as actually seeing the slide means it’s more likely you’ll remember what your teacher was saying at the time.

The Bullet Journaling Method

Another one for visual learners, the Bullet Journaling Method allows you to be as creative with your note-taking as you want to be.

With this technique, you take aesthetically-pleasing notes and sort information in the way your mind works – which can involve blending multiple note-taking methods.

The aim is to make your bullet journal as attractive and organised as possible. Although, this can be difficult to do when you’re scribbling down notes in a classroom environment, so you can always use another technique when writing notes in class and then transfer them to your bullet journal when reviewing them afterwards.

Is it better to hand-write study notes or type them up?

As you now know from reading this article, there are multiple ways in which you can take good study notes, and it’s up to you to decide which method is best suited to the way your brain understands and retains information.

Similarly, whether you prefer handwriting notes or typing them up on a laptop or tablet, it’s your choice how you record the information you’ve learned from a lecture or textbook.

It could be argued that because typing is quicker, you’re less likely to process information properly in order to condense it into note-form. Or that electronic devices provide more opportunities for distraction. However, self-disciplined students may benefit from taking in-depth digital notes they can study extensively once a class is over.

What are some tips for taking better study notes?

If you’re struggling to take effective study notes, you might find the following tips helpful:

- Don’t try to write everything down – just focus on key points and phrases.

- But don’t write too little either, as this could lead to ambiguity.

- Avoid the temptation to copy everything, word-for-word. Write in short, succinct sentences, organising and rewriting the original material in your own words. This will also help to ensure you’re not plagiarising.

- If you’re short on time, use abbreviations and symbols, or try drawing pictures or diagrams instead.

- Colour-code what you’ve written after the initial note-taking; not during.

- If you don’t understand something, remember to go back later and clarify it.

How to get the most out of your study notes

Throughout this article, we’ve spoken about reviewing your notes, and we can’t stress enough, the importance of doing this.

You should review your notes within the first 24 hours to make sure you retain as much information as possible, and then go back over small portions of your notes every day up until an exam or test.

Your study notes will also come in handy when doing research or assigned reading, as you can refer to them to ensure you have a good understanding of the subject matter.

Writing study notes in your own words is one of the best ways to make sure you’ve remembered and understood what your teacher is saying in class or what you’ve read in a textbook. It will also make exam time less stressful, as your study notes will be really helpful with revision.

When it comes to taking good notes, there are many different methods – you just need to find the one that suits you best.

Some of the most popular note-taking methods are the Cornell Method, the Outline Method, the Mapping Method, the Chart Method, the Sentence Method, the Flow Notes Method, the Writing on Slides Method and the Bullet Journaling Method.

Some tips to help you take effective study notes include making sure you focus only on the key points and phrases, drawing pictures if you’re short on time and remembering to clarify anything you don’t understand.

Once you’ve taken your notes and class is over, it’s extremely important to go back over them to increase the chances of the information staying in your head.

The Learning Strategies Center

- Meet the Staff

- –Supplemental Course Schedule

- AY Course Offerings

- Anytime Online Modules

- Winter Session Workshop Courses

- –About Tutoring

- –Office Hours and Tutoring Schedule

- –LSC Tutoring Opportunities

- –How to Use Office Hours

- –Campus Resources and Support

- –Student Guide for Studying Together

- –Find Study Partners

- –Productivity Power Hour

- –Effective Study Strategies

- –Concept Mapping

- –Guidelines for Creating a Study Schedule

- –Five-Day Study Plan

- –What To Do With Practice Exams

- –Consider Exam Logistics

- –Online Exam Checklist

- –Open-Book Exams

- –How to Tackle Exam Questions

- –What To Do When You Get Your Graded Test (or Essay) Back

- –The Cornell Note Taking System

- –Learning from Digital Materials

- –3 P’s for Effective Reading

- –Textbook Reading Systems

- –Online Learning Checklist

- –Things to Keep in Mind as you Participate in Online Classes

- –Learning from Online Lectures and Discussions

- –Online Group Work

- –Learning Online Resource Videos

- –Start Strong!

- –Effectively Engage with Classes

- –Plans if you Need to Miss Class

- –Managing Time

- –Managing Stress

- –The Perils of Multitasking

- –Break the Cycle of Procrastination!

- –Finish Strong

- –Neurodiversity at Cornell

- –LSC Scholarship

- –Pre-Collegiate Summer Scholars Program

- –Study Skills Workshops

- –Private Consultations

- –Resources for Advisors and Faculty

- –Presentation Support (aka Practice Your Talk on a Dog)

- –About LSC

- –Meet The Team

- –Contact Us

The Cornell Note Taking System

Why do you take notes? What do you hope to get from your notes? What are Cornell Notes and how do you use the Cornell note-taking system?

There are many ways to take notes. It’s helpful to try out different methods and determine which work best for you in different situations. Whether you are learning online or in person, the physical act of writing can help you remember better than just listening or reading. Research shows that taking notes by hand is more effective than typing on a laptop. This page and our Canvas module will teach you about different note-taking systems and styles and help you determine what will work best for your situation.

In our Cornell Note Taking System module you will:

- Examine your current note taking system

- Explore different note taking strategies (including the Cornell Notes system)

- Assess which strategies work best for you in different situations

The best way to explore your current note-taking strategies and learn about the Cornell note taking system is to go through our Canvas note taking module. The module will interactively guide you through how to use Cornell Notes – click on the link here or the button below. This module is publicly available.

Just want to see a bit more about Cornell Notes? You can view the videos below.

Watch: What are Cornell Notes?

Watch: Learn how students use the Cornell Note Taking System

The Cornell Note-Taking System was originally developed by Cornell education professor, Walter Pauk. Prof. Pauk outlined this effective note-taking method in his book, How to Study in College (1).

- Pauk, Walter; Owens, Ross J. Q. (2010). How to Study in College (10 ed.). Boston, MA: Wadsworth. ISBN 978-1-4390-8446-5 . Chapter 10: “The Cornell System: Take Effective Notes”, pp. 235-277

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 5 Study Skills

5.6 Note-Taking

You’ve got the PowerPoint slides for your lecture, and the information in your textbook. Do you need to take notes as well?

Despite the vast amount of information available in electronic formats, taking notes is an important learning strategy. In addition, the way that you take notes matters, and not all note-taking strategies lead to equal results. By considering your note-taking strategies carefully, you will be able to create a set of notes that will help retain the most important concepts from lectures and tests, and that will assist you in your exam preparation.

Two Purposes for Taking Notes

People take notes for two main reasons:

- To keep a record of the information they heard. This is also called the external storage function of note-taking.

- To facilitate learning material they are currently studying.

The availability of information on the internet may reduce the importance of the external storage function of note-taking. When the information is available online, it may seem logical to stop taking notes. However, by neglecting to take notes, you lose the benefits of note-taking as a learning tool.

How Note-Taking Supports Learning

Taking notes during class supports your learning in several important ways:

- Taking notes helps you to focus your attention and avoid distractions.

- As you take notes in class, you will be engaging your mind in identifying and organizing the main ideas. Rather than passively listening, you will be doing the work of active learning while in class, making the most of your time.

- Creating good notes means that you will have a record for later review. Reviewing a set of condensed and well-organized notes is more efficient than re-reading longer texts and articles.

Everybody takes notes, or at least everybody claims to. But if you take a close look, many who are claiming to take notes on their laptops are actually surfing the Web, and paper notebooks are filled with doodles interrupted by a couple of random words with an asterisk next to them reminding you that “This is important!” In college and university, these approaches will not work. Your instructors expect you to make connections between class lectures and reading assignments; they expect you to create an opinion about the material presented; they expect you to make connections between the material and life beyond school. Your notes are your road maps for these thoughts. Do you take good notes? Actively listening and note-taking are key strategies to ensure your student success.

Effective note-taking is important because it

- supports your listening efforts.

- allows you to test your understanding of the material.

- helps you remember the material better when you write key ideas down.

- gives you a sense of what the instructor thinks is important.

- creates your “ultimate study guide.”

There are various forms of taking notes, and which one you choose depends on both your personal style and the instructor’s approach to the material. Each can be used in a notebook, index cards, or in a digital form on your laptop. No specific type is good for all students and all situations, so we recommend that you develop your own style, but you should also be ready to modify it to fit the needs of a specific class or instructor. To be effective, all of these methods require you to listen actively and to think; merely jotting down words the instructor is saying will be of little use to you.

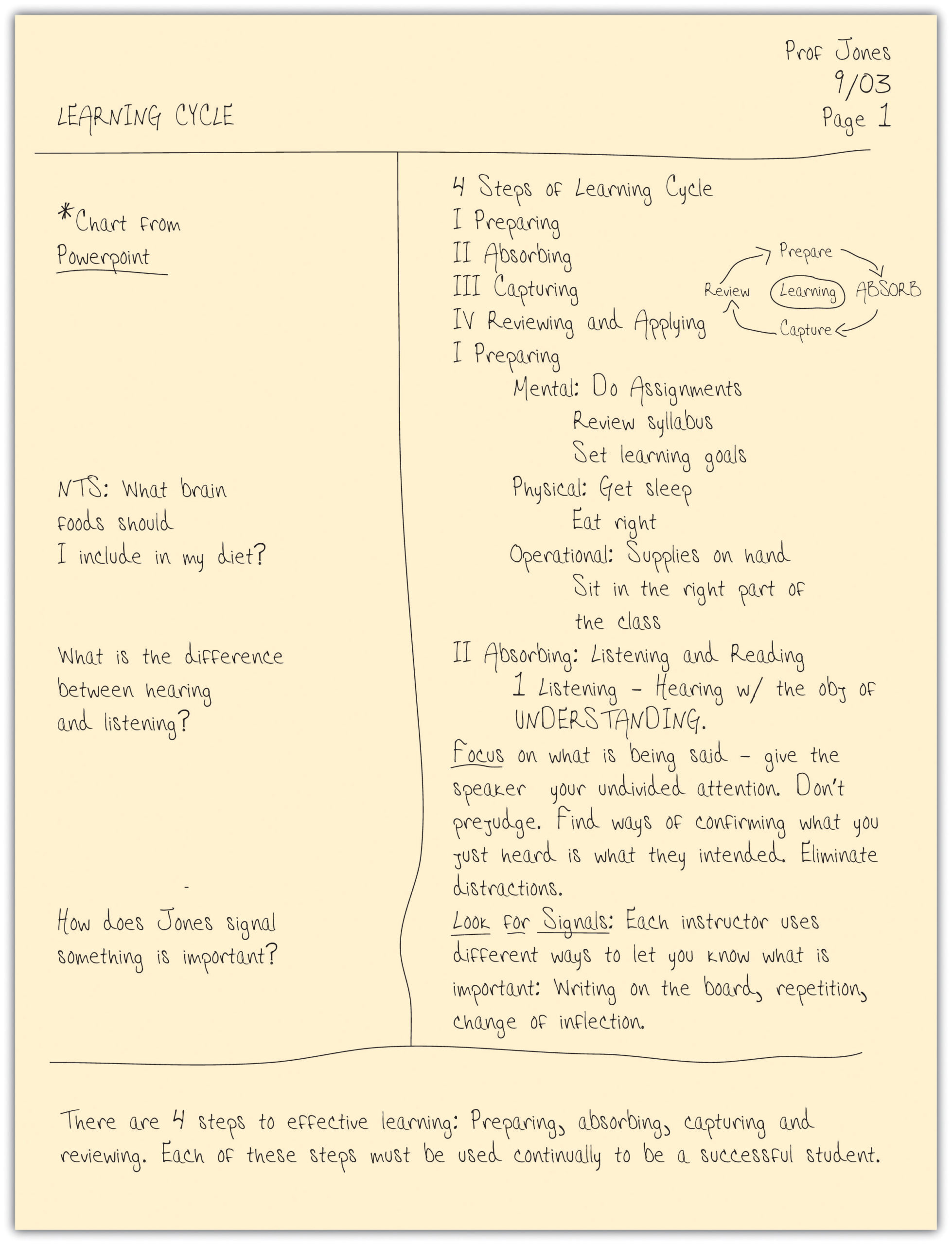

The List Method

Example: The List Method of Note-taking

Learning Cycle

September 3

Prof. Jones

The learning cycle is an approach to gathering and retaining info that can help students be successful in Col. The cycle consists of 4 steps which should all be app’d. They are preparing, which sets the foundation for learning, absorbing, which exposes us to new knowledge, capturing, which sets the information into our knowledge base and finally reviewing and applying which lets us set the know. into our memory and use it.

Preparing for learning can involve mental preparation, physical prep, and oper. prep. Mental prep includes setting learning goals for self based on what we know the class w/ cover (see syllabus)/ Also it is very important to do any assignments for the class to be able to learn w/ confidence and…. ______________

Physical Prep means having enough rest and eating well. Its hard to study when you are hungry and you won’t listen well in class if you doze off.

Operation Prep means bringing all supplies to class, or having them at hand when studying… this includes pens, paper, computer, textbook, etc. Also means setting to school on time and getting a good seat (near the front).

Absorbing new knowledge is a combination of listening and reading. These are two of the most important learning skills you can have.

The list method is usually not the best choice because it is focused exclusively on capturing as much of what the instructor says as possible, not on processing the information. Most students who have not learned effective study skills use this method, because it’s easy to think that this is what note-taking is all about. Even if you are skilled in some form of shorthand, you should probably also learn one of the other methods described here, because they are all better at helping you process and remember the material. You may want to take notes in class using the list method, but transcribe your notes to an outline or concept map method after class as a part of your review process. It is always important to review your notes as soon as possible after class and write a summary of the class in your own words.

The Outline Method

Example: The Outline Method of Note-taking

Learning is a cycle made up of 4 steps:

- Preparing: Setting the foundation for learning.

- Absorbing: (Data input) Exposure to new knowledge.

- Capturing: Taking ownership of the knowledge.

- Review & Apply: Putting new knowledge to work.

- assignments from prior classes.

- Readings! (May not have been assigned in class – see Syllabus!)

- Know what instructor expects to cover

- Know what assignments you need to do

- Set your own objective

- Get right about of rest. Don’t zzz in class.

- Eat right. Hard to focus when you are hungry.

- Arrive on time.

- Bring right supplies – (Notebooks, Texts, Pens, etc.)

- Get organized and ready to listen

- Don’t unterupt the focus of others

- Get a good seat

- Sit in the front of the class.

The advantage of the outline method is that it allows you to prioritize the material. Key ideas are written to the left of the page, subordinate ideas are then indented, and details of the subordinate ideas can be indented further. To further organize your ideas, you can use the typical outlining numbering scheme (starting with roman numerals for key ideas, moving to capital letters on the first subordinate level, Arabic numbers for the next level, and lowercase letters following.) At first you may have trouble identifying when the instructor moves from one idea to another. This takes practice and experience with each instructor, so don’t give up! In the early stages you should use your syllabus to determine what key ideas the instructor plans to present. Your reading assignments before class can also give you guidance in identifying the key ideas.

If you’re using your laptop computer for taking notes, a basic word processing application (like Microsoft Word or Works) is very effective. Format your document by selecting the outline format from the format bullets menu. Use the increase or decrease indent buttons to navigate the level of importance you want to give each item. The software will take care of the numbering for you!

After class be sure to review your notes and then summarize the class in one or two short paragraphs using your own words. This summary will significantly affect your recall and will help you prepare for the next class.

The Concept Map Method

Example: The Concept Map Method of Note-taking

This is a very graphic method of note-taking that is especially good at capturing the relationships among ideas. Concept maps harness your visual sense to understand complex material “at a glance.” They also give you the flexibility to move from one idea to another and back easily (so they are helpful if your instructor moves freely through the material).

To develop a concept map, start by using your syllabus to rank the ideas you will listen to by level of detail (from high-level or abstract ideas to detailed facts). Select an overriding idea (high level or abstract) from the instructor’s lecture and place it in a circle in the middle of the page. Then create branches off that circle to record the more detailed information, creating additional limbs as you need them. Arrange the branches with others that interrelate closely. When a new high-level idea is presented, create a new circle with its own branches. Link together circles or concepts that are related. Use arrows and symbols to capture the relationship between the ideas. For example, an arrow may be used to illustrate cause or effect, a double-pointed arrow to illustrate dependence, or a dotted arrow to illustrate impact or effect.