Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: A case study

Affiliations.

- 1 University of North Dakota, United States of America. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 University of North Dakota, United States of America.

- 3 Dana Wiley, MD PA.

- PMID: 35461644

- DOI: 10.1016/j.apnu.2021.12.003

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is often misdiagnosed or mistreated in adults because it is often thought of as a childhood problem. If a child is diagnosed and treated for the disorder, it often persists into adulthood. In adult ADHD, the symptoms may be comorbid or mimic other conditions making diagnosis and treatment difficult. Adults with ADHD require an in-depth assessment for proper diagnosis and treatment. The presentation and treatment of adults with ADHD can be complex and often requires interdisciplinary care. Mental health and non-mental health providers often overlook the disorder or feel uncomfortable treating adults with ADHD. The purpose of this manuscript is to discuss the diagnosis and management of adults with ADHD.

Keywords: Adult; Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder; Misuse; Psychoeducation; Stimulant.

Copyright © 2022 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

- Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity* / diagnosis

- Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity* / epidemiology

- Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity* / therapy

- Comorbidity

- Mental Health*

- Open access

- Published: 23 November 2023

Risk factors associated with newly diagnosed attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: a retrospective case-control study

- Jeff Schein 1 ,

- Martin Cloutier 2 ,

- Marjolaine Gauthier-Loiselle 2 ,

- Rebecca Bungay 2 ,

- Emmanuelle Arpin 2 ,

- Annie Guerin 2 &

- Ann Childress 3

BMC Psychiatry volume 23 , Article number: 870 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

2315 Accesses

18 Altmetric

Metrics details

Knowledge of risk factors for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) may facilitate early diagnosis; however, studies examining a broad range of potential risk factors for ADHD in adults are limited. This study aimed to identify risk factors associated with newly diagnosed ADHD among adults in the United States (US).

Eligible adults from the IQVIA PharMetrics® Plus database (10/01/2015-09/30/2021) were classified into the ADHD cohort if they had ≥ 2 ADHD diagnoses (index date: first ADHD diagnosis) and into the non-ADHD cohort if they had no observed ADHD diagnosis (index date: random date) with a 1:3 case-to-control ratio. Risk factors for newly diagnosed ADHD were assessed during the 12-month baseline period; logistic regression with stepwise variable selection was used to assess statistically significant association. The combined impact of selected risk factors was explored using common patient profiles.

A total of 337,034 patients were included in the ADHD cohort (mean age 35.2 years; 54.5% female) and 1,011,102 in the non-ADHD cohort (mean age 44.0 years; 52.4% female). During the baseline period, the most frequent mental health comorbidities in the ADHD and non-ADHD cohorts were anxiety disorders (34.4% and 11.1%) and depressive disorders (27.9% and 7.8%). Accordingly, a higher proportion of patients in the ADHD cohort received antianxiety agents (20.6% and 8.3%) and antidepressants (40.9% and 15.8%). Key risk factors associated with a significantly increased probability of ADHD included the number of mental health comorbidities (odds ratio [OR] for 1 comorbidity: 1.41; ≥2 comorbidities: 1.45), along with certain mental health comorbidities (e.g., feeding and eating disorders [OR: 1.88], bipolar disorders [OR: 1.50], depressive disorders [OR: 1.37], trauma- and stressor-related disorders [OR: 1.27], anxiety disorders [OR: 1.24]), use of antidepressants (OR: 1.87) and antianxiety agents (OR: 1.40), and having ≥ 1 psychotherapy visit (OR: 1.70), ≥ 1 specialist visit (OR: 1.30), and ≥ 10 outpatient visits (OR: 1.51) (all p < 0.05). The predicted risk of ADHD for patients with treated anxiety and depressive disorders was 81.9%.

Conclusions

Mental health comorbidities and related treatments are significantly associated with newly diagnosed ADHD in US adults. Screening for patients with risk factors for ADHD may allow early diagnosis and appropriate management.

Peer Review reports

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a debilitating neurodevelopmental condition with an estimated prevalence of 4.4% among adults in the United States (US) [ 1 ]. ADHD is traditionally perceived as a childhood disorder [ 2 ]; hence, underdiagnosis, delayed diagnosis, and undertreatment of ADHD are believed to be common among adults [ 3 , 4 ].

The diagnostic challenges of ADHD are partially attributable to the frequent comorbid mental disorders [ 5 , 6 ]. Certain mental health comorbidities, such as anxiety and depressive disorders, share overlapping symptoms with ADHD [ 7 , 8 ], potentially leading to misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis. Studies have suggested that about one-fifth of adults seeking psychiatric services and reporting for other mental health conditions were later found to have ADHD [ 9 , 10 , 11 ]. The World Health Organization Mental Health Survey has also reported that among US adults with ADHD identified through diagnostic interviews, approximately half had received some form of treatment for their emotional or behavioral problems in the past year, but only 13.2% were treated specifically for ADHD [ 12 ]. Clinicians’ lack of awareness or training on adult ADHD may also hinder ADHD diagnosis [ 4 ]. A US medical record-based study found that 56% of adults with ADHD had not received a prior diagnosis of the condition despite complaining about ADHD symptoms to other healthcare professionals in the past [ 13 ]. Other reasons adding to the diagnostic challenge of ADHD in adults may include patient’s fear of stigma and masking behaviors developed over the years [ 4 , 14 ].

ADHD is associated with a wide range of psychosocial, functional, and occupational problems in adults [ 15 ]. A delay in diagnosis, or undiagnosed and ultimately untreated ADHD, may lead to poor clinical and functional outcomes even if comorbidities are treated [ 16 ]. Conversely, early identification of ADHD may allow better symptom management and improve patient functioning and quality of life. To facilitate diagnosis, risk factors are commonly used to predict disease development and aid clinicians to identify at-risk patients [ 17 ]. However, there is a paucity of large studies examining a broad range of potential risk factors for an ADHD diagnosis in adults. Prior studies have reported certain patient characteristics, such as presence of anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, sleep impairments, eating disorders, and childhood illnesses or health events (e.g., obesity, head injuries, infections) that may be associated with ADHD [ 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ]. Yet, most of these studies have examined a single or a few factors, and many were conducted in pediatric ADHD populations primarily outside of the US.

Knowledge on patient characteristics associated with a higher risk of ADHD in adults and the patient journey prior to a clinical ADHD diagnosis may facilitate early diagnosis and the provision of appropriate management. The current study was conducted to identify risk factors for newly diagnosed ADHD in adult patients using a large claims database in the US. The potential utility of the results was also demonstrated through exploring the combined impact of selected risk factors on ADHD risk prediction using fictitious common patient profiles.

Data source

Data from the IQVIA PharMetrics® Plus (IQVIA) database covering the period of October 1, 2015, to September 30, 2021, were used. The IQVIA database contains integrated claims data of over 190 million beneficiaries across the US and includes information on inpatient and outpatient diagnoses and procedures, prescription fills, patients’ pharmacy and medical benefits, inpatient stays, and provider details. Additional data elements encompass dates of service, demographic variables, plan type, payer type, and start and stop dates of health plan enrollment. Data are de-identified and comply with the patient requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA); therefore, no review by an institutional review board nor informed consent was required per Title 45 of CFR, Part 46.101(b)(4) [ 24 ].

Study design and patient populations

A retrospective case-control study design was used. Eligible adults were classified into two cohorts based on the presence of ADHD diagnoses (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] F90.x): the ADHD cohort comprised patients with ≥ 2 ADHD diagnoses recorded on a medical claim on distinct dates at any time during their continuous health plan enrollment; and the non-ADHD cohort comprised patients without any ADHD diagnoses recorded on a medical claim at any time during their continuous health plan enrollment. To account for large differences in sample size and to retain statistical power, a 1:3 case-to-control ratio was used. Specifically, eligible patients were randomly selected into the non-ADHD cohort such that the total number of patients in the non-ADHD cohort was three times that of the ADHD cohort.

The index date was defined as the first observed ADHD diagnosis among the ADHD cohort and a randomly selected date among the non-ADHD cohort. To allow sufficient time to capture potential risk factors for ADHD, patients were required to have ≥ 12 months of continuous health plan enrollment prior to the index date. The baseline period was defined as the 12 months pre-index.

Study measures and outcomes

Patient characteristics and potential risk factors for newly diagnosed ADHD were assessed during the baseline period for each cohort, separately. Potential risk factors considered in this study were identified through a targeted literature review and observable variables in the data and included demographic characteristics (i.e., age, sex, regions of residence, calendar year of index date), clinical characteristics (i.e., physical and mental health comorbidities), pharmacological treatments (i.e., medications for common ADHD comorbidities), healthcare resource utilization (i.e., number of psychotherapy, inpatient, emergency room, outpatient, and specialist [psychiatrist, neurologist] visits). Risk factors for ADHD in this study were identified from potential risk factors that had statistically significant association with newly diagnosed ADHD, as described in the next section.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline patient characteristics and potential risk factors for newly diagnosed ADHD. Means, medians, and standard deviations (SDs) were reported for continuous variables; frequency counts and percentages were reported for categorical variables.

Univariate statistics were used to compare potential risk factors between the ADHD and non-ADHD cohorts. The magnitude of the difference between cohorts was assessed by calculating the standardized differences (std. diff.) for both continuous and categorical variables.

Logistic regression model with stepwise variable selection was used to assess statistically significant association between potential risk factors and ADHD diagnosis. Potential risk factors were eligible for inclusion in the logistic regression based on their univariate association with ADHD diagnosis (i.e., std. diff. >0.10). Potential risk factors presented in < 0.5% of the sample were discarded. Variables included in the last iteration of the stepwise selection process were considered as risk factors of the study outcome. The association between risk factors and ADHD diagnosis were reported as odds ratios (ORs) along with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values.

To facilitate the interpretation of the regression analyses, the predicted risk of ADHD based on regression coefficient estimates was evaluated for six fictitious common patient profiles corresponding to patients who harbor selected combinations of ADHD risk factors. This exploratory analysis allowed for the estimation of how the risk of having ADHD would vary had the same person had additional risk factors but otherwise the same characteristics.

Patient characteristics and potential risk factors

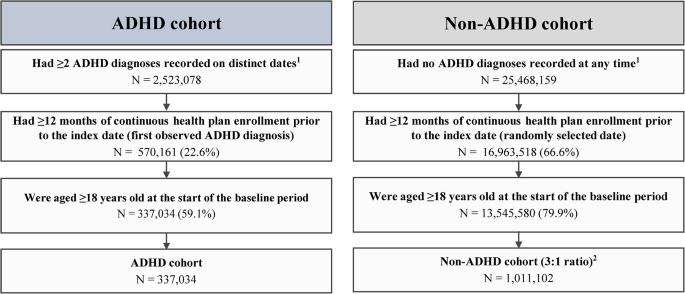

The total sample comprised 1,348,136 patients, including 337,034 in the ADHD cohort and 1,011,102 in the non-ADHD cohort (Fig. 1 ). Table 1 presents the patient characteristics and potential risk factors (i.e., characteristics with a std. diff. >0.10) by cohort.

Sample selection flowchart. ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ICD-10-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification

1 ADHD was defined as ICD-10-CM codes: F90.x

2 Eligible patients were randomly selected into the non-ADHD cohort such that the total number of patients in the non-ADHD cohort is 3 times that of the ADHD cohort to account for large differences in sample size

Demographic characteristics

As of index date, the ADHD cohort was younger than the non-ADHD cohort (mean age: 35.2 and 44.0 years; std. diff. = 0.68). In both cohorts, slightly over half of the patients were female (54.5% and 52.4%; std. diff. = 0.04), and the South was the most represented region (48.7% and 42.5%; std. diff. = 0.13).

Clinical characteristics

During the baseline period, the most frequent physical comorbidities in the ADHD and non-ADHD cohorts were hypertension (12.4% and 21.3%; std. diff. = 0.24), obesity (10.0% and 9.4%; std. diff. = 0.02), and chronic pulmonary disease (9.0% and 7.2%; std. diff. = 0.07).

A lower proportion of patients had no mental health comorbidities in the ADHD cohort than the non-ADHD cohort (42.0% and 70.8%; std. diff. = 0.61). The mean ± SD number of mental health comorbidities was 1.2 ± 1.4 in the ADHD cohort and 0.5 ± 0.9 in the non-ADHD cohort (std. diff. = 0.65). The most frequent mental health comorbidities in the ADHD and non-ADHD cohorts were anxiety disorders (34.4% and 11.1%; std. diff. = 0.58), depressive disorders (27.9% and 7.8%; std. diff. = 0.54), sleep-wake disorders (13.2% and 7.7%; std. diff. = 0.18), trauma- and stressor-related disorders (12.4% and 3.4%; std. diff. = 0.34), and substance-related and addictive disorders (9.4% and 5.0%; std. diff. = 0.17).

Pharmacological treatments

A higher proportion of patients in the ADHD than the non-ADHD cohort received antidepressants (40.9% and 15.8%; std. diff. = 0.58), antianxiety agents (20.6% and 8.3%; std. diff. = 0.36), anticonvulsants (16.1% and 6.8%; std. diff. = 0.29), and antipsychotics (7.2% and 1.5%; std. diff. = 0.28).

Healthcare resource utilization

The ADHD cohort, relative to the non-ADHD cohort, had generally higher mean ± SD rates of healthcare resource utilization, including more psychotherapy visits (2.9 ± 8.8 and 0.6 ± 4.0; std. diff. = 0.34), emergency room visits (0.6 ± 1.7 and 0.4 ± 1.2; std. diff. = 0.14), outpatient visits (12.7 ± 16.5 and 8.3 ± 12.4; std. diff. = 0.30), and specialist visits (1.0 ± 4.0 and 0.2 ± 1.8; std. diff. = 0.24); the number of inpatient visits were similar between cohorts (0.1 ± 0.4 and 0.1 ± 0.3; std. diff. = 0.04).

Association between risk factors and ADHD diagnosis

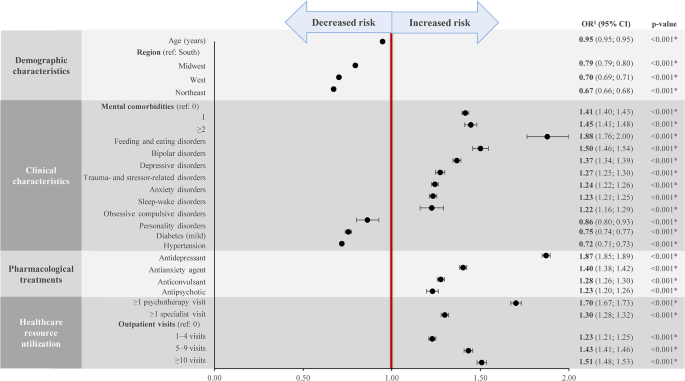

The risk factors with a significant association with an ADHD diagnosis are presented in Fig. 2 . Demographically, being younger and living in the South were risk factors for having an ADHD diagnosis (OR for age: 0.95; OR for region of residence using South as a reference: Midwest, 0.79; West, 0.70; Northwest, 0.67; all p < 0.05).

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio

*Statistically significant at the 5% level

1 Estimated from logistic regression analyses

Other key risk factors associated with a significantly increased probability of having an ADHD diagnosis included the number of mental health comorbidities (OR for 1 comorbidity: 1.41; ≥2 comorbidities: 1.45); certain mental health comorbidities, including feeding and eating disorders (OR: 1.88), bipolar disorders (OR: 1.50), depressive disorders (OR: 1.37), trauma- and stressor-related disorders (OR: 1.27), anxiety disorders (OR: 1.24), sleep-wake disorders (OR: 1.23), and obsessive compulsive disorders (OR: 1.22); use of antidepressants (OR: 1.87) and antianxiety agents (OR: 1.40); and having ≥ 1 psychotherapy visit (OR: 1.70), ≥ 1 specialist visit (OR: 1.30), and ≥ 10 outpatient visits (OR: 1.51) (all p < 0.05).

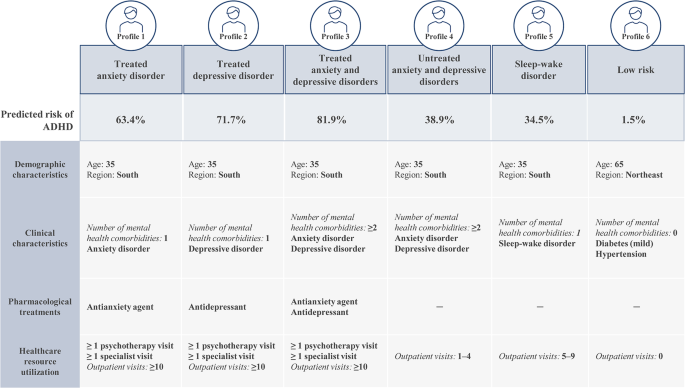

Predicted risk of ADHD for patient profiles with selected risk factors

Selected risk factors identified from the logistic regression analyses were used to create fictitious common patient profiles to demonstrate their combined impact on the predicted risk of having an ADHD diagnosis (Fig. 3 ). Five of the six profiles correspond to patients with the same demographic characteristics (i.e., aged 35 years and living in the South) but vary in terms of the number (i.e., 1 or ≥ 2) and types of mental health comorbidities (i.e., anxiety disorder and/or depressive disorder), the pharmacological treatment received (i.e., antianxiety and/or antidepressant agent, or no treatment), and the level of healthcare resource utilization (i.e., number of psychotherapy, specialist, and outpatient visits). The remaining profile corresponds to low-risk patients with no relevant risk factors for ADHD.

Predicted risk of ADHD for selected patient profiles

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

Based on these patient profiles, the predicted risk of ADHD was the highest among patients with treated anxiety and depressive disorders (profile 3). More specifically, a patient presenting with the characteristics described in this profile would have an 81.9% likelihood of being diagnosed with ADHD in the coming year. The profile with the next highest predicted risk of ADHD was patients with treated depressive disorder (profile 2; 71.7%), followed by patients with treated anxiety disorder (profile 1; 63.4%). Profiles corresponding to a moderate predicted risk of ADHD included patients with untreated anxiety and depressive disorders (profile 4; 38.9%) and patients with sleep-wake disorder (profile 5; 34.5%). The predicted risk for ADHD among low-risk patients (profile 6) was 1.5%.

This large retrospective case-control study has identified a broad range of risk factors associated with ADHD in adults and quantified the added likelihood of an ADHD diagnosis contributed by each factor. Certain mental health comorbidities and their associated treatments and care were found to be significantly associated with newly diagnosed ADHD in adults. Specifically, the presence of common mental health comorbidities of ADHD such as anxiety and depressive disorders was associated with 24% and 37% increased risk of having an ADHD diagnosis, respectively. The use of pharmacological treatments for these conditions such as antianxiety agents and antidepressants was associated with an increased risk of having an ADHD diagnosis of 40% and 87%, respectively; having at least one prior psychotherapy visit was also associated with a 70% increased risk. Demographically, being younger and living in the South were found to be risk factors for having an ADHD diagnosis. The combined impact of selected risk factors on the predicted ADHD risk was explored through specific patient profiles, which demonstrated how the findings may be interpreted in clinical settings. The presence of a combination of risk factors may suggest that a patient is at a high risk of having undiagnosed ADHD and signify the need for further assessments. Collectively, findings of this study have extended our understanding on the patient path to ADHD diagnosis as well as the characteristics and clinical events that could suggest undiagnosed ADHD in adults.

Most prior studies examining characteristics associated with ADHD have focused on a single or a few factors, and many were conducted in pediatric populations [ 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ]. Nonetheless, the risk factors for ADHD identified in the current study are largely aligned with the literature. For instance, among prior research in adults, a multicenter patient register study found that at the time of first ADHD diagnosis, mental health comorbidities were present in two-thirds of the patients; patients on average presented with 2.4 comorbidities, with the most common comorbidities being substance use disorders, anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and personality disorders [ 6 ]. Another study among adult members of two large managed healthcare plans found that compared with individuals without ADHD, those screened positive for ADHD through a telephone survey but had no documented ADHD diagnosis (i.e., the undiagnosed group) had significantly higher rates of mental health comorbidities (e.g., anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder) and were more likely to receive medications for a mental health condition [ 25 ]. In line with these findings, the current exploratory patient profile analyses also suggest that patients with more mental health comorbidities and have received the associated pharmacological treatments and care are at a higher risk of having undiagnosed ADHD than those with fewer or untreated mental health comorbidities.

The current study also found that an overall higher healthcare resource utilization was a characteristic associated with newly diagnosed ADHD among adult patients. A potential interpretation of this finding is that an individual who experienced ADHD-related symptoms might visit a psychologist or physician frequently to seek help for the symptoms; thus, a high level of prior healthcare resource utilization may be a sign that an individual could have undiagnosed ADHD. Clinical judgement should be applied to determine whether further evaluation for ADHD is needed on a case-by-case basis considering the presence of other high-risk characteristics.

The diagnosis of ADHD can be challenging, particularly among adults [ 2 , 3 ]. The current study suggests that information on patient characteristics, such as the presence of mental health comorbidities and healthcare resource utilization history, may be used to aid clinicians identify adult patients at risk of ADHD and minimize missed opportunity to provide a timely diagnosis of ADHD and the proper care. Notably, underdiagnosis or a delayed diagnosis of ADHD leads to undertreatment and can adversely affect patients’ occupational achievements, diminish self-esteem, and hamper interpersonal relationships, considerably reducing the quality of life [ 8 ]. ADHD in adults has also been shown to be associated with approximately $123 billion total societal excess costs in the US [ 26 ]. Consequently, early detection and treatment of ADHD may have the potential to alleviate the large patient and societal burden associated with the condition.

It is worth mentioning that causes for ADHD is multifactorial, and multiple risk factors may contribute to the risk of having ADHD [ 15 ]. Some risk factors in the literature (e.g., genetics and environmental factors [ 27 , 28 ]) are not available in claims data, and these factors are important to consider when establishing an ADHD diagnosis. Nonetheless, the risk factors identified in this study were generated based on a large sample size (over 1.3 million adults), and as exemplified by the exploratory patient profiles, the presence of multiple risk factors was associated with an overall higher risk of having undiagnosed ADHD. Together, these findings would help inform clinicians on the types of high-risk patient profiles that should raise a red flag for potential ADHD and prompt further clinical assessments, such as family psychiatric history and diagnostic interviews. As such, findings of this study may facilitate early diagnosis and appropriate management of ADHD among adults, which may in turn improve patient outcomes.

The findings of the current study should be considered in light of certain limitations inherent to retrospective databases using claims data, including the risk of data omissions, coding errors, and the presence of rule-out diagnosis. Nonetheless, while few studies specifically assessed the validity of ICD-10-CM codes for ADHD diagnoses in claims data, literature evidence has suggested high accuracy of ICD-9-CM codes in identifying neurodevelopmental disorders, including ADHD, and a good correspondence between the ICD-9 and − 10 codes is expected [ 29 , 30 ]. Furthermore, ICD codes have been widely used in the literature to identify ADHD diagnoses in claims-based analyses [ 31 , 32 , 33 ]. Meanwhile, as the study included commercially insured patients, the sample may not be representative of the entire ADHD population in the US. Furthermore, potential risk factors were limited to information available in health insurance claims data only, which may lack relevant information related to ADHD, such as presence of childhood ADHD, family history, or environmental factors. In addition, some characteristics may interact with multiple variables such that their association with an ADHD diagnosis may already be captured by other variables; as such, a characteristic with an OR of less than 1 should not be interpreted as having a protective effect against an ADHD diagnosis but rather that the characteristic alone may be insufficient to prompt screening for ADHD. Lastly, findings from this retrospective observational analysis should be interpreted as measures of association; no causal inference can be drawn.

This large retrospective case-control study found that mental health comorbidities and related treatments and care are significantly associated with newly diagnosed ADHD in US adults. The presence of a combination of risk factors may suggest that a patient is at a high risk of having undiagnosed ADHD. The results of this study provide insights on the path to ADHD diagnosis and may aid clinicians identify at-risk patients for screening, which may facilitate early diagnosis and appropriate management of ADHD.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from IQVIA but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the corresponding author (email: [email protected]) upon reasonable request and with permission of IQVIA.

Abbreviations

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

Confidence intervals

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification

Standard deviation

Standardized difference

United States

Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, Biederman J, Conners CK, Demler O, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):716–23.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Weibel S, Menard O, Ionita A, Boumendjel M, Cabelguen C, Kraemer C, et al. Practical considerations for the evaluation and management of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adults. Encephale. 2020;46(1):30–40.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Ginsberg Y, Quintero J, Anand E, Casillas M, Upadhyaya HP. Underdiagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adult patients: a review of the literature. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16(3).

Prakash J, Chatterjee K, Guha S, Srivastava K, Chauhan VS. Adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: from clinical reality toward conceptual clarity. Ind Psychiatry J. 2021;30(1):23–8.

Kooij JJ, Huss M, Asherson P, Akehurst R, Beusterien K, French A, et al. Distinguishing comorbidity and successful management of adult ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2012;16(5 Suppl):3S–19S.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Pineiro-Dieguez B, Balanza-Martinez V, Garcia-Garcia P, Soler-Lopez B, The CAT Study Group. Psychiatric comorbidity at the time of diagnosis in adults with ADHD: the CAT study. J Atten Disord. 2016;20(12):1066–75.

D’Agati E, Curatolo P, Mazzone L. Comorbidity between ADHD and anxiety disorders across the lifespan. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2019;23(4):238–44.

Goodman DW, Thase ME. Recognizing ADHD in adults with comorbid mood disorders: implications for identification and management. Postgrad Med. 2009;121(5):20–30.

Almeida MLG, Hernandez GAO, Ricardo-Garcell J. ADHD prevalence in adult outpatients with nonpsychotic psychiatric illnesses. J Atten Disord. 2007;11(2):150–6.

Article Google Scholar

Nylander L, Holmqvist M, Gustafson L, Gillberg C. ADHD in adult psychiatry. Minimum rates and clinical presentation in general psychiatry outpatients. Nord J Psychiatry. 2009;63(1):64–71.

Deberdt W, Thome J, Lebrec J, Kraemer S, Fregenal I, Ramos-Quiroga JA, et al. Prevalence of ADHD in nonpsychotic adult psychiatric care (ADPSYC): a multinational cross-sectional study in Europe. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:242.

Fayyad J, De GR, Kessler R, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Demyttenaere K, et al. Cross-national prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:402–9.

Faraone SV, Spencer TJ, Montano CB, Biederman J. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: a survey of current practice in psychiatry and primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(11):1221–6.

Lebowitz MS. Stigmatization of ADHD: a developmental review. J Atten Disord. 2016;20(3):199–205.

Faraone SV, Asherson P, Banaschewski T, Biederman J, Buitelaar JK, Ramos-Quiroga JA, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15020.

Pawaskar M, Fridman M, Grebla R, Madhoo M. Comparison of quality of life, productivity, functioning and self-esteem in adults diagnosed with ADHD and with symptomatic ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2020;24(1):136–44.

Offord DR, Kraemer HC. Risk factors and prevention. Evid Based Ment Health. 2000;3(3):70–1.

Carpena MX, Munhoz TN, Xavier MO, Rohde LA, Santos IS, Del-Ponte B, et al. The role of sleep duration and sleep problems during childhood in the development of ADHD in adolescence: findings from a population-based birth cohort. J Atten Disord. 2020;24(4):590–600.

Liu CY, Asherson P, Viding E, Greven CU, Pingault JB. Early predictors of de novo and subthreshold late-onset ADHD in a child and adolescent cohort. J Atten Disord. 2021;25(9):1240–50.

Meinzer MC, Pettit JW, Viswesvaran C. The co-occurrence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and unipolar depression in children and adolescents: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34(8):595–607.

Mowlem FD, Rosenqvist MA, Martin J, Lichtenstein P, Asherson P, Larsson H. Sex differences in predicting ADHD clinical diagnosis and pharmacological treatment. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;28(4):481–9.

So M, Dziuban EJ, Pedati CS, Holbrook JR, Claussen AH, O’Masta B et al. Childhood physical health and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of modifiable factors. Prev Sci. 2022.

Levy LD, Fleming JP, Klar D. Treatment of refractory obesity in severely obese adults following management of newly diagnosed attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Int J Obes (Lond). 2009;33(3):326–34.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 45 CFR 46: pre-2018 requirements [Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/45-cfr-46/index.html#46.101 .

Able SL, Johnston JA, Adler LA, Swindle RW. Functional and psychosocial impairment in adults with undiagnosed ADHD. Psychol Med. 2007;37(1):97–107.

Schein J, Adler LA, Childress A, Gagnon-Sanschagrin P, Davidson M, Kinkead F, et al. Economic burden of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among adults in the United States: a societal perspective. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2022;28(2):168–79.

PubMed Google Scholar

Palladino VS, McNeill R, Reif A, Kittel-Schneider S. Genetic risk factors and gene-environment interactions in adult and childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatr Genet. 2019;29(3):63–78.

Thapar A, Cooper M, Eyre O, Langley K. What have we learnt about the causes of ADHD? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;54(1):3–16.

Straub L, Bateman BT, Hernandez-Diaz S, York C, Zhu Y, Suarez EA, et al. Validity of claims-based algorithms to identify neurodevelopmental disorders in children. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2021;30(12):1635–42.

Gruschow SM, Yerys BE, Power TJ, Durbin DR, Curry AE. Validation of the use of electronic health records for classification of ADHD status. J Atten Disord. 2019;23(13):1647–55.

Classi PM, Le TK, Ward S, Johnston J. Patient characteristics, comorbidities, and medication use for children with ADHD with and without a co-occurring reading disorder: a retrospective cohort study. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2011;5:38.

Shi Y, Hunter Guevara LR, Dykhoff HJ, Sangaralingham LR, Phelan S, Zaccariello MJ, et al. Racial disparities in diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a US national birth cohort. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e210321.

Schein J, Childress A, Adams J, Gagnon-Sanschagrin P, Maitland J, Qu W, et al. Treatment patterns among children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the United States - A retrospective claims analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):555.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

Medical writing assistance was provided by Flora Chik, PhD, MWC, an employee of Analysis Group, Inc., and funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc.

Financial support for this research was provided by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. The study sponsor was involved in several aspects of the research, including the study design, the interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript, and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc, 508 Carnegie Center, Princeton, NJ, 08540, USA

Jeff Schein

Analysis Group, Inc, 1190 avenue des Canadiens-de-Montréal, Tour Deloitte, Suite 1500, Montréal, QC, H3B 0G7, Canada

Martin Cloutier, Marjolaine Gauthier-Loiselle, Rebecca Bungay, Emmanuelle Arpin & Annie Guerin

Center for Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, 7351 Prairie Falcon Rd STE 160, Las Vegas, NV, 89128, USA

Ann Childress

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

MC, MGL, RB, EA, and AG contributed to study conception and design, collection and assembly of data, and data analysis and interpretation. JS and AC contributed to study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation. All authors reviewed and approved the final content of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rebecca Bungay .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The research was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Data analyzed in this study are de-identified and comply with the patient requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA); therefore, no review by an institutional review board nor informed consent was required per Title 45 of CFR, Part 46.101(b)(4) [ 24 ].

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

JS is an employee of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc. AC received research support from Allergan, Takeda/Shire, Emalex, Akili, Ironshore, Arbor, Aevi Genomic Medicine, Neos Therapeutics, Otsuka, Pfizer, Purdue, Rhodes, Sunovion, Tris, KemPharm, Supernus, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration; was on the advisory board of Takeda/Shire, Akili, Arbor, Cingulate, Ironshore, Neos Therapeutics, Otsuka, Pfizer, Purdue, Adlon, Rhodes, Sunovion, Tris, Supernus, and Corium; received consulting fees from Arbor, Ironshore, Neos Therapeutics, Purdue, Rhodes, Sunovion, Tris, KemPharm, Supernus, Corium, Jazz, Tulex Pharma, and Lumos Pharma; received speaker fees from Takeda/Shire, Arbor, Ironshore, Neos Therapeutics, Pfizer, Tris, and Supernus; and received writing support from Takeda /Shire, Arbor, Ironshore, Neos Therapeutics, Pfizer, Purdue, Rhodes, Sunovion, and Tris. MC, MGL, RB, EA, and AG are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development & Commercialization, Inc.

Previous presentation

Part of the material in this manuscript was presented at the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) 2023 conference held on May 7–10, 2023, in Boston, MA, as a poster presentation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Schein, J., Cloutier, M., Gauthier-Loiselle, M. et al. Risk factors associated with newly diagnosed attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: a retrospective case-control study. BMC Psychiatry 23 , 870 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05359-7

Download citation

Received : 05 May 2023

Accepted : 07 November 2023

Published : 23 November 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05359-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Anxiety disorder

- Depressive disorder

- Comorbidity

- Risk factor

BMC Psychiatry

ISSN: 1471-244X

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Sage Choice

- PMC10009485

Disentangling the Associations Between Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Child Sexual Abuse: A Systematic Review

Rachel langevin.

1 Department of Educational and Counselling Psychology, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Carley Marshall

Aimée wallace.

2 Département de sexologie, Université du Québec à Montréal, Quebec, Canada

Marie-Emma Gagné

Emily kingsland.

3 McGill Library, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Caroline Temcheff

Background:.

An association between child sexual abuse (CSA) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has been documented. However, the temporal relationship between these problems and the roles of trauma-related symptoms or other forms of maltreatment remain unclear. This review aims to synthesize available research on CSA and ADHD, assess the methodological quality of the available research, and recommend future areas of inquiry.

Studies were searched in five databases including Medline and PsycINFO. Following a title and abstract screening, 151 full texts were reviewed and 28 were included. Inclusion criteria were sexual abuse occurred before 18 years old, published quantitative studies documenting at least a bivariate association between CSA and ADHD, and published in the past 5 years for dissertations/theses, in French or English. The methodological quality of studies was systematically assessed.

Most studies identified a significant association between CSA and ADHD; most studies conceptualized CSA as a precursor of ADHD, but only one study had a longitudinal design. The quality of the studies varied greatly with main limitations being the lack of (i) longitudinal designs, (ii) rigorous multimethod/ multiinformant assessments of CSA and ADHD, and (iii) control for two major confounders: trauma-related symptoms and other forms of child maltreatment.

Discussion:

Given the lack of longitudinal studies, the directionality of the association remains unclear. The confounding role of other maltreatment forms and trauma-related symptoms also remains mostly unaddressed. Rigorous studies are needed to untangle the association between CSA and ADHD.

Child sexual abuse (CSA) is a major public health concern that can have a long-lasting impact throughout the life span. It is estimated that approximately 20% of girls and 8% of boys will experience CSA before the age of 18 years ( Stoltenborgh et al., 2011 ). CSA has been found to be associated with a myriad of mental health problems that can persist through adulthood, including dissociation ( Hillberg et al., 2011 ), depression ( Hillberg et al., 2011 ), and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and anxiety ( Chen et al., 2010 ; Hillberg et al., 2011 ). An adverse childhood experience such as CSA is likely to disrupt the mastery of core developmental tasks ( Irigagay et al., 2013 ), such as the ability to regulate emotions and to form secure attachments. ( Doyle & Cicchetti, 2017 ). CSA has also been empirically associated with internalizing and externalizing behavior problems in childhood ( Berliner, 2011 ; Langevin et al., 2015 ) and with difficulties in the school environment (e.g., peer victimization, lower grades, need for special education; Daignault & Hébert, 2009 ; Hébert et al., 2016 ; Perfect et al., 2016 ). CSA, as well as other types of childhood maltreatment, has been associated with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; Fuller-Thomson & Lewis, 2015 ; González et al., 2019 ; Sanderud et al., 2016 ). Although ADHD has been linked to CSA in previous studies, the direction of this association and its relationship to other mental health problems is unclear. Interestingly, this temporality issue with ADHD and CSA only applies to few other consequences/risk factors that have been associated with CSA (e.g., chronic conditions; Assink et al., 2019 ).

ADHD is a heritable neurodevelopmental disorder with prevalence rates ranging from 2% to 7.1% depending on meta-analytic rates ( Sayal et al., 2018 ; Willcutt, 2012 ). ADHD typically has a childhood onset (less than 12 years old) and is characterized by inattention and/or hyperactivity–impulsivity ( American Psychiatric Association, 2013 ). The associated patterns of behaviors can cause performance-related issues in educational, social, and professional environments that can persist into adulthood ( Harpin et al., 2016 ). For example, Ebejer and colleagues (2012) found ADHD symptoms in adults to be associated with poorer health, lower educational attainment, and higher rates of unemployment. In addition, a Danish study found individuals with ADHD to have higher annual health care costs and to be more likely to receive social services in adulthood ( Jennum et al., 2020 ). In this review, the terms ADHD and ADHD symptoms will be used. ADHD refers to the diagnosis, whereas ADHD symptoms refer to the presence of symptoms that do not necessarily reach the clinical levels of the disorder. ADHD and ADHD symptoms, like CSA, can have dramatic consequences on individual’s adaptation and should be the focus of prevention and intervention efforts aiming to reduce the burden on affected individuals and, more largely, society.

As previously mentioned, CSA has been associated with ADHD in both men and women, but the direction of this association remains unclear. Indeed, some scholars have studied how ADHD can be a risk factor for later sexual victimization, while others have looked at the impact of CSA on the development of ADHD symptoms ( Ebejer et al., 2012 ; Fuller-Thomson & Lewis, 2015 ; Fuller-Thomson et al., 2016 ). A few mechanisms have been suggested to explain CSA as a risk factor for ADHD ( Fuller-Thompson & Lewis, 2015 ): (1) Stress induced by the exposure to CSA may cause changes in the individual’s brain functioning (e.g., deficits in default mode network connectivity involved in the activation of the medial temporal, prefrontal cortices, and the limbic areas integrated in the posterior cingulate) that could result in ADHD ( Anda et al., 2006 ; Dvir et al., 2014 ) and (2) learned experiences of threat, such as CSA, could affect the neural development and lead to changes in brain structures that are consistent with ADHD ( McLaughlin et al., 2014 ). Conversely, it has also been demonstrated that ADHD can be a risk factor for CSA ( Gotby et al., 2018 ). Experts speculate that children with ADHD (among other neurodevelopmental disorders) may be perceived as different, and it may be easier for motivated, potential offenders to dehumanize their victims and thus to transgress boundaries ( Gotby et al., 2018 ; Rudman & Mescher, 2012 ). It is also worthy to mention that several ADHD symptoms overlap with core symptoms of PTSD, raising concerns about potential misdiagnosis of ADHD in traumatized individuals ( Spencer et al., 2016 ).

Despite burgeoning interest in the topic and the multiplication of studies looking at the interrelations between CSA and ADHD in the past decades, to date, no systematic review synthesizing the evidence is available. Given the current state of research on this topic and the mixed perspectives on the direction of the association between ADHD and CSA, integrating the available research will help in identifying future directions of inquiry and help both clinicians and researchers have a better understanding of the mechanisms underlying the ADHD–CSA association. In this context, the current systematic review aims to (1) synthesize available research on the associations between CSA and ADHD, its temporality and its relationship to trauma-related symptoms, (2) assess the methodological quality of available research, and (3) recommend directions for future research and practice.

Article Search and Selection

Subject headings (when available) and key words were searched from the following databases in this order: (1) MEDLINE Ovid (1946–January 8, 2020), (2) PsycINFO Ovid (1806–January 8, 2020), (3) ERIC EBSCOhost (Education Resources Information Center; 1966–January 8, 2020), (4) Scopus (searched January 8, 2020), and (5) ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global (searched January 8, 2020). The initial search was built in Medline (see Appendix ). It was peer-reviewed by Dr. Tracie Afifi, Professor at the University of Manitoba, who has expertise in research on child maltreatment and mental health.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Given our specific interest in CSA, to be included in the review, sexual abuse had to have occurred before 18 years of age. Other inclusion criteria included published quantitative studies, dissertations and theses, and conference proceedings, as well as book chapters if they reported original findings. Studies published in English and French were included. There were no inclusion or exclusion criteria pertaining to the demographic background of participants nor where the study was conducted or published. Other review papers were not included. All articles published up to the time of article search/extraction (January 8, 2020) were included, except for theses and dissertations (only the past 5 years).

The search resulted in 2,825 articles. After removal of duplicates, 2,353 articles remained, which were imported into Rayyan ( Ouzzani et al., 2016 ) to facilitate the screening process. Following a review of titles and abstracts, 2,202 articles were excluded, resulting in 151 articles deemed eligible for full-text assessment. Following full-text assessment, a further 123 articles were excluded, leaving a final sample of 28 articles for this review. See Figure 1 for a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2009 flow diagram.

Data Extraction and Analysis

To address interrater reliability, the first 60 titles and abstracts were reviewed by the first three authors, after which the second and third authors continued screening, met to discuss discrepancies with each other, as well as consulted with the first author in cases of uncertainty. The same process was conducted for reading the 151 full-text articles; all were read and agreed upon by the second and third author, while consulting the first author. Throughout the process of full-text screening, the last author was also consulted for her expertise in externalizing behaviors. After reading the 151 full-text articles, 123 were excluded due to ADHD not being clearly measured. For instance, many studies examined behavioral or externalizing problems more generally or measured the association between conduct problems and sexual abuse.

The 28 remaining articles were assessed for quality using the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies, published by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute ( https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools ). This is a 14-item tool that requires readers to assess papers primarily on methods and requires a final rating of “good”, “fair”, or “poor.” The final 28 articles were evenly divided among the first three authors and last author, who appraised and summarized the articles in pairs. A summary template was created, so that each author extracted the same information from their articles including study aims, study design, sample, setting and procedures, measures, principal relevant results, and limitations. The authors met to discuss and resolve discrepancies in appraisal items and the final quality ratings.

The presentation of the findings is subdivided based on the theoretically or empirically postulated direction of the effects between CSA and ADHD. As such, papers conceptualizing CSA as a risk factor for ADHD are presented first, subdivided based on the use of an adult (mean age of 18 years or older) or child sample. Next, papers conceptualizing ADHD as a risk factor for CSA are presented with the same subdivision based on sample type. Finally, papers that did not seem to postulate a specific direction between CSA and ADHD, and therefore that appeared to conceptualize these as comorbid problems, are summarized. Further, presentation of the findings is separated based on the use of bivariate versus more complex analytic approaches accounting for potential confounders in the relation between ADHD and CSA. See Table 1 for details about the included studies.

Review Results Organized by Child and Adult Samples.

Note. OR = odds ratio; ADHD = attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; CSA = child sexual abuse; CTQ-SF: Conflict Tactics Scale-Short Form; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder; CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist; YSR = Youth Self Report; YASR = Young Adult Self Report; K-SADS-PL-T = Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia; DISC-IV = Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children IV; CRS = Conners’ Rating Scales; BAARS-IV = The Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale–IV; BPD = borderline personality disorder; DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition ; SES = socioeconomic status.

CSA as a Predictor of ADHD—Adult Samples (n = 7)

Two studies conceptualizing CSA as a risk factor for ADHD and using adult samples only provided bivariate associations. In their study of male inmates ( n = 799), Matsumoto and Imamura (2007) found that ADHD symptoms were higher for sexually abused than nonabused men. According to Sanderud et al. (2016 ; n = 2,980, community sample), young adults with a history of CSA were 2.07 times more likely to report ADHD than nonabused adults.

Five of the seven studies with adult samples conceptualizing CSA as a predictor of ADHD included potentially confounding factors in their analyses; all but one identified significant associations between CSA and ADHD. Using a representative sample of Canadian adults ( n = 23,395, population-based sample), Afifi et al. (2014) showed that CSA victims were 1.7 times more at risk of reporting suffering from attention deficit disorder (inattentive subtype of ADHD) than nonvictims after controlling for sociodemographic factors, other types of child abuse, and any diagnosed mental disorders, including PTSD. Using the same sample, Fuller-Thomson and Lewis (2015 ; n = 10,496 men, 12,877 women; population-based sample) found that both men and women were around 2.5 times more likely to have attention deficit disorder (renamed ADHD by the authors) if they reported a history of CSA, after controlling for age, parental domestic abuse, and physical abuse. After accounting for conduct problems and various childhood factors (e.g., socioeconomic status, parental conflicts and rules, family structure), CSA significantly predicted ADHD symptoms in another study ( Ebejer et al., 2012 ; n = 3,795, community sample). Women with borderline personality disorder and ADHD had higher scores of CSA than women without borderline personality and ADHD, while women only reporting ADHD did not differ in terms of CSA scores from women without ADHD and borderline personality ( Ferrer et al., 2017 ; n = 204, clinical sample). In this study, combined ADHD and borderline personality was significantly and uniquely predicted by childhood emotional abuse, physical abuse, and sexual abuse. Finally, the only study including confounding variables that did not show a significant association between CSA and ADHD in their adult sample is Boyd et al. (2019 ; n = 7,214, community sample). In this longitudinal study, CSA did not predict self-reported attention problems at 21 years old in bivariate analyses and multiple regressions controlling for several sociodemographic factors, birthweight, maternal depression, and other child maltreatment types.

CSA as a Predictor of ADHD—Child Samples (n = 9)

Three studies conceptualizing CSA as a predictor of ADHD with child samples documented bivariate associations. Comparing hyperactivity scores in their sample of sexually abused children ( n = 112, clinical sample) to the sample used to create the norms of the measure used, Gomes-Schwartz et al. (1985) identified a positive association with CSA. In comparison to the Turkish norms, another study found higher scores of attention problems (hyperactivity not measured) in sexually abused children over a 3-year period ( Ozbaran et al., 2009 ; n = 20, clinical sample). In contrast to the findings in these clinical samples, González et al. (2019) found no associations between CSA and ADHD in their Latino community sample ( n = 2,480).

Of the nine studies conceptualizing CSA as a predictor of ADHD using a child sample, six considered potential confounding factors; all but one found significant associations. In their longitudinal study, Boyd et al. (2019) found that after accounting for several sociodemographic factors and other maltreatment types, CSA was associated with more attention problems (hyperactivity not measured) at 14 years old as documented using parent reports, but not youth reports. Walrath et al. (2003 ; n = 759 children with CSA; 2,722 children with no CSA; clinical sample), after accounting for demographics (gender, age, and race) and life challenges (psychiatric hospitalization, physical abuse, runaway attempts, suicide attempts, drug/alcohol use, sexual abuse, and sibling in foster care), also had different results depending on the respondent for ADHD symptoms. Based on clinicians’ ratings of primary diagnosis, children with a history of sexual abuse had lower rates of ADHD than nonabused children. However, the relation was reversed when using caregivers’ reports of attention problems using the Child Behavior Checklist, and no difference was found when using children’s ratings. Sonnby et al. (2011) found that boys and girls ( n = 4,910, community sample) were more likely to have symptoms of ADHD if they were sexually abused, even after accounting for familial and sociodemographic factors, although this association was stronger among girls. Two studies examined the impact of CSA characteristics. One of them showed that while controlling for dissociation, intrafamilial abuse was associated with greater attention problems (hyperactivity not measured) than extrafamilial abuse ( Kaplow et al., 2008 ; n = 127, clinical sample). The other showed that when gender, age at onset of the CSA, severity, frequency, duration, perpetrator type, and physical abuse history were considered, children with higher frequencies of CSA had more attention problems (hyperactivity not measured; Ruggiero et al., 2000 ; n = 80 children with CSA, community sample). Finally, the one study that did not identify CSA as a significant predictor of ADHD symptoms was Ford et al. (2009 ; n = 397, residential treatment sample). In their analyses, they controlled for several potential confounding factors including gender, ethnicity, other mental disorders (psychotic, internalizing and externalizing, developmental, and substance use), complex traumatic experiences, parental impairment, placement history, and physical abuse.

ADHD as a Predictor of CSA—Adult Samples (n = 4)

All studies using an adult sample and conceptualizing ADHD as a risk factor for CSA accounted for potential confounding factors, and all uncovered significant associations. Adjusting only for gender and place of residence, Jaisoorya et al. (2019) found that the risk of contact and noncontact sexual abuse in college students ( n = 5,145, community sample) with clinically significant ADHD symptoms was three-fold as compared to non-ADHD students. While controlling for several sociodemographic and family factors, Ouyang et al. (2008) found that ADHD inattentive and combined types were associated with an increased risk of contact sexual abuse ( n = 14,322, population-based sample). Finally, two studies using the same sample of young women recruited through university psychology classes ( n = 417, community sample; White & Buelher, 2012 ; White et al., 2014 ) found that after accounting for sociodemographic variables, ADHD symptoms were associated with greater sexual victimization experiences during adolescence and that this association was mediated by risky sexual behaviors.

ADHD as a Predictor of CSA—Child Samples (n = 4)

Conducting only bivariate analyses, Gul and Gurkan (2018) found no differences in CSA rates between the ADHD ( n = 100) and control group ( n = 100) in their Turkish clinical sample. Gokten et al. (2016) also found no difference in rates of CSA between children with ( n = 104) and without ADHD ( n = 104; clinical sample). Conversely, Jaisoorya et al. (2016 ; n = 7,150, community sample) found that teenagers with ADHD combined type (inattention and hyperactivity) had higher odds (odds ratio [OR] = 3.63) of contact sexual abuse than non-ADHD teenagers.

One study using a child sample and conceptualizing ADHD as a predictor of CSA included potential confounding factors in their analyses. Ohlsson et al. (2018 ; n = 4,500, population-based) found that girls with clinical ADHD had two times the risk of being sexually abused when compared to non-ADHD girls. A similar pattern was found with boys, but it was nonsignificant. Ohlsson et al. (2018) only controlled for overall neurodevelopmental disorder symptoms as potential confounding factors in these analyses.

CSA and ADHD as Comorbid Problems—Adult Samples (n = 2)

No study conceptualizing CSA and ADHD as comorbid problems, without clear directionality, and using an adult sample included potential confounders in their analyses. Fuller-Thomson et al. (2016) found a significant difference in prevalence rates of CSA among adult women with ( n = 107) and without ADHD ( n = 3,801, subsample from the population-based sample used by Afifi et al., 2014 ). Rucklidge et al. (2006) reported a positive association between ADHD scores and CSA among women ( n = 114, community sample).

CSA and ADHD as Comorbid Problems—Child Samples (n = 3)

Among the three studies documenting the association between CSA and ADHD without clear hypothesized directionality and using child samples, none included covariates. Ford et al. (2000 ; n = 165, clinical sample) found positive associations between ADHD and sexual abuse, with the highest rate being among children with both ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder. In their cluster analysis study, Hébert et al. (2006) found that three of the four clusters of sexually abused children ( n = 123, clinical sample) had higher scores of inattention (hyperactivity not measured) than the comparison group of nonabused children ( n = 123, community sample). Finally, McLeer et al. (1994) failed to identify a significant association between ADHD diagnosis and sexual abuse in their small clinical sample ( n = 26 sexually abused children, 23 nonsexually abused children).

Methodological Quality of Reviewed Papers

The methodological quality of the 28 studies included in this review varied greatly. Of all of the articles, seven were rated highly ( Afifi et al., 2014 ; Boyd et al., 2019 ; González et al., 2019 ; Ruggiero et al., 2000 ; Sonnby et al., 2011 ; White & Buehler, 2012 ; White et al., 2014 ), nine fairly ( Ebejer et al., 2012 ; Ferrer et al., 2017 ; Fuller-Thomson & Lewis., 2015 ; Fuller-Thomson et al., 2016 ; Jaisoorya et al., 2016 ; Kaplow et al., 2008 ; Ohlsson et al., 2018 ; Ozbaran et al., 2009 ; Sanderud et al., 2016 ), nine poorly ( Ford et al., 2000 ; Fuller-Thomson et al., 2016 ; Gomes-Schwartz et al., 1985 ; Gul & Gurkan, 2018 ; Hébert et al., 2006 ; Jaisoorya et al., 2019 ; Matsumoto & Imamura, 2007 ; McLeer et al., 1994 ; Rucklidge et al., 2006 ; Walrath et al., 2003 ), two fell between fair and poor ( Ford et al., 2009 ; Ouyang et al., 2008 ), and one between fair and good ( Gokten et al., 2016 ). The main limitations related to the design, the sample, the measures, and the statistical analyses. Almost all studies had cross-sectional designs ( n = 27), and only one study was prospective longitudinal ( Boyd et al., 2019 ), the most robust design for determining an association between CSA and ADHD. In addition, the outcome assessors were often unblinded to the CSA status of the participants ( n = 23) which could have biased their assessment of ADHD symptoms. Of the 28 studies, only two presented a justification for their sample size in the form of a power analysis. Of the 26 studies that did not, eight had large samples which did not raise concerns over statistical power considerations, leaving a subsample of 18 studies that might have been underpowered. On the other hand, most studies ( n = 23) recruited participants from the same or similar populations (including the same time period) with predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria that were consistently applied to all participants.

Regarding the measures, in over half ( n =17) of the studies, the CSA measure were considered valid and reliable while 10 were not. Additionally, for one study, due to unclear information about the measures, it was not possible to determine whether the CSA measure used was valid. For 23 of the studies, the ADHD measure was considered valid and reliable, with only five studies that did not reach such standards. Moreover, for the assessment of CSA, 23 studies used questionnaires and parent-report and/or child self-report measures whereas five studies used more robust methods of assessment such as chart reviews or corroborated cases by child protective services. For the assessment of ADHD, 26 studies used questionnaires and parent-report, teacher-report, and/or child self-report measures whereas two studies used more robust measures, such as diagnosis by a clinician.

In terms of the analyses performed to examine the associations between ADHD and CSA, confounding variables of other maltreatment types and sociodemographic/other variables (e.g., sex, age, family structure, and income) were adjusted statistically for their impact on the relationship in only eight studies. In 17 studies, either sociodemographic/other variables or other maltreatment types were controlled for, and in most of these cases, it was the sociodemographic factors that were included. Only one study controlled for the presence of PTSD ( Afifi et al., 2014 ); one study controlled for dissociation symptoms ( Kaplow et al., 2008 ). Three studies only conducted bivariate analysis to document the association between CSA and ADHD.

This systematic review synthesized and critically assessed the methodological quality of available research on the association between CSA and ADHD. Over the past 35 years, 12 studies documented these associations using an adult sample, 15 using a child or adolescent sample, and one had a longitudinal design encompassing both adolescence and early adulthood ( Boyd et al., 2019 ). Most studies (82%) uncovered significant associations between CSA and ADHD or ADHD symptoms and, surprisingly, this proportion did not differ much depending on the number of confounding factors included in the main analyses. A little over half of the studies reviewed (57%) included at least one potentially confounding factor in their examination of the associations between CSA and ADHD, but only 21% of included studies controlled for other maltreatment types, despite the well-documented high rates of co-occurrence between different forms of child maltreatment and family adversity (e.g., Turner et al., 2010 ). The most frequent confounding factors incorporated were sociodemographic factors and family characteristics such as family size, parental conflicts, and parental psychopathology. Comorbid psychiatric disorders were also controlled for in 17.8% ( n = 5) of included studies, and only two studies (7.1%) controlled for PTSD or trauma-related symptoms (i.e., dissociation), consequently limiting greatly our ability to disentangle the associations between CSA, ADHD, and trauma symptoms. More than half of the included studies were based on samples from the United States or Canada (see Table 1 study setting for the list of countries). Associations would need to be explored further in more diverse samples and samples from other countries which might have varying rates of ADHD and CSA. Indeed, cross-cultural studies have inconsistent findings, some showing similar rates of ADHD across cultures ( Bauermeister et al., 2010 ; Polanczyk et al., 2014 ), and others showing overrepresentation of some ethnic groups (e.g., African American, Hispanic American) in children diagnosed with ADHD ( Flowers & McDougle, 2010 ; Gomez-Benito et al., 2019 ). CSA is also known to have highly varying rates globally ( Stoltenborgh et al., 2011 ).

Furthermore, we were unable to clarify the directionality of the association between CSA and ADHD. A little over half of studies conceptualized CSA as a risk factor for ADHD (53%), while 29% conceptualized ADHD as a risk factor for future CSA, and a minority of studies (18%) did not make clear assumptions regarding the temporal association between these variables. While there seems to be a tendency to consider CSA a risk factor for the development of ADHD symptoms, only one study had an appropriate design—prospective longitudinal—to ascertain such directionality ( Boyd et al., 2019 ). According to Boyd et al.’s (2019) findings, CSA only predicts ADHD symptoms in adolescence when parental reports are used.

Recently, Craig et al. (2020) published a systematic review on child maltreatment and ADHD and reported only five longitudinal studies, showing that early maltreatment is a risk factor for developing ADHD symptoms later on. However, the authors note that these findings are not consistent. Whereas some studies reported maltreatment predicting attention problems ( Thompson & Tabone, 2010 ), the associations were not as clear in other studies. For example, Stern et al. (2018) found ADHD and maltreatment associations concurrently across development. Relevant to the topic of this review, dissociative symptoms are common following sexual abuse ( Trickett et al., 2011 ) and can make differential diagnosis difficult, especially in children, since periods of dissociation may cause children to appear dazed, inattentive, and unfocused in the classroom ( Ford & Courtois, 2013 ). On the other hand, Lugo-Candelas et al. (2020) highlight that the reverse relationship of ADHD predicting adverse experiences has been understudied. Based on a longitudinal population-based study, they found that children with ADHD at Wave 1, specifically the inattentive, were more likely to experience adverse childhood experiences later on. Based on a sample of adults with childhood histories of ADHD ( n = 97) and a comparison group of adults with no ADHD history ( n = 121), Wymbs and Gidycz (2020) also reported that those with ADHD histories were more likely to experience sexual assault, assessed at or after the age of 14. Although these findings contribute to the literature on ADHD as a risk factor for abuse, this was a cross-sectional study and sexual abuse before the age of 14 was not analyzed.

While some included studies were rated strongly, there are several other limitations that were uncovered through the systematic assessment of the methodological quality of the available research, and these limitations compromise even further our ability to untangle the associations between CSA and ADHD based on the current evidence base. Hence, only a quarter of included studies was rated as high quality regarding the pursued objectives of the current review. Highly ranked studies had strengths such as large and representative samples and validated measures of CSA and ADHD (e.g., structured interviews, multiinformant measurement, validated questionnaires), in addition to using appropriate statistical analysis controlling for major confounders (e.g., other traumatic events, trauma symptoms). One third of included studies were rated as fair or good-to-fair, meaning that they had some important limitations regarding their sample (e.g., small, unrepresentative), recruitment procedures (e.g., convenience sampling), measures (e.g., unvalidated, self-report only), or statistical procedures (e.g., few confounding factors included). Finally, 40% of included studies were considered poor or poor-to-fair quality, highlighting major limitations such as the use of small, unrepresentative samples, unclear methods limiting reproducibility, unvalidated measures of ADHD and CSA, and poor control for confounding factors such as sociodemographic factors, other maltreatment types, and mental health symptoms.

In addition to these general ratings, it is worth mentioning that even though a gold standard assessment of ADHD usually requires a structured battery of neuropsychological tests, parent and teacher reports, and in-depth clinical interviews to avoid misdiagnoses ( Wolraich et al., 2011 ), almost all studies included in this review based their assessment of one or two informants using questionnaires. Thus, risks of confusion between actual ADHD symptoms and symptoms related to other psychopathologies (e.g., anxiety, mood; Mao & Findling, 2014 ) or typical reactions to psychosocial stressors or traumatic experiences ( Szymanski et al., 2011 ), especially in the context of the study of CSA ( Mii et al., 2020 ), are extremely high. Findings from Walrath et al. (2003) seem to confirm this risk of misdiagnosis when using self- or parent-report measures of ADHD instead of official diagnoses from clinicians. Indeed, they found that nonsexually abused children, when compared to abused children, were at higher risk of having ADHD as a primary diagnosis given by a clinician, while parent reports indicated higher attention problems in sexually abused children. This could be explained by the fact that clinicians are better able to discriminate between trauma and ADHD symptoms than parents, but also by the fact that questionnaires, such as the Child Behavior Checklist, do not offer enough sensitivity and contextualization to allow determining the cause behind the observed behavior, increasing the risk of mislabeling symptoms (e.g., labeling dissociation symptoms as attention deficit). However, an alternative explanation might be that clinicians misinterpret ADHD symptoms as trauma symptoms when assessing sexually abused children. Finally, the measurement of CSA was also problematic in several studies. Indeed, given problems with the sole use of retrospective recall or single question assessments (e.g., memory, underreporting), but also the limitations of relying only on official child protection records (e.g., major underreporting), a multimethod assessment is desirable ( Baldwin et al., 2019 ); none of the studies used such an approach.

In light of these major limitations, several recommendations may be made. First, there is a pressing need for prospective longitudinal studies documenting the associations over time of CSA and ADHD. Only such studies could clarify the temporal relationship between CSA and ADHD and might even show that transactional processes are at play between these two variables. For example, ADHD could increase the risk of being sexually abused, and in turn, CSA could increase already existing ADHD symptoms; or CSA could lead to ADHD symptoms that in turn increase someone’s risk of later sexual revictimization. Second, there needs to be rigorous assessment of both CSA and ADHD in participants, including differential diagnosis using neuropsychological tests for ADHD, and the integration of both self- and parent reports of CSA using validated questionnaires or interviews, and official child protection services data which would necessitate the use of clinical samples. Complementary to fine-grained analyses of clinical samples, there is a need for large and representative samples to minimize selection bias and ensure appropriate statistical power, and for cross-cultural studies or studies with diverse samples. Finally, studies should assess and control major confounding factors such as other forms of child maltreatment and family adversity, sociodemographic and cultural factors, and comorbid psychopathologies, especially trauma-related symptoms (e.g., PTSD, dissociation). The consideration of the potential impact of CSA characteristics, and even of the characteristics of the other maltreatment experiences where applicable, could also be appropriate given findings from Kaplow et al. (2008) and Ruggiero et al. (2000) .

Our review itself is not without limitations. Despite our efforts to ensure every relevant study would be included (e.g., including every major database related to the topic, having our search strategy peer-reviewed), there is always a risk of missing some due to the selection of databases, the search strategy used, or mistakes during the screening process. Also, we did not include gray literature and unpublished dissertations older than 5 years. Further, we were not able to combine the studies using a meta-analysis due to the heterogeneity of included papers in terms of measures, samples, and designs. Therefore, we are not able to test for impactful moderators or to determine the strength of the association between CSA and ADHD.

Implications and Conclusion

In line with research on this topic, clinicians have also reported on the associations between CSA and ADHD ( Burke Harris, 2018 ). Our rigorous systematic review revealed 28 studies. Of those, 16 were rated as at least fair using the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies; only one was longitudinal in nature and was highly rated in terms of quality; only two controlled for trauma-related symptoms, one of which was highly rated and one of which was fair. Although most studies pointed to a general link between CSA and ADHD, clearly, high quality, controlled, longitudinal evidence is sparse at best. Implications are summarized in Table 2 .

Implications for Research, Practice, and Policy.