Disclaimer » Advertising

- HealthyChildren.org

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Presentation

The condition, lessons for the clinician, poster presentations:, section editor’s note, suggested readings, case 5: a 13-year-old boy with abdominal pain and diarrhea.

AUTHOR DISCLOSURE

Drs Sudhanthar, Okeafor, and Garg have disclosed no financial relationships relevant to this article. This commentary does not contain a discussion of an unapproved/investigative use of a commercial product/device.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- CME Quiz Close Quiz

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Anjali Garg , Sathyan Sudhanthar , Chioma Okeafor; Case 5: A 13-year-old Boy with Abdominal Pain and Diarrhea. Pediatr Rev December 2017; 38 (12): 572. https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.2016-0223

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

A 13-year-old boy presents to his primary care provider with a 5-day history of abdominal pain and a 2-day history of diarrhea and vomiting. He describes the quality of the abdominal pain as sharp, originating in the epigastric region and radiating to his back, and exacerbated by movement. Additionally, he has had several episodes of nonbloody, nonbilious vomiting and watery diarrhea. His mother discloses that several family members at the time also have episodes of vomiting and diarrhea.

He admits to decreased oral intake throughout the duration of his symptoms. He denies any episodes of fever, weight loss, fatigue, night sweats, or chills. He also denies any hematochezia or hematemesis. His medical history is significant for a ventricular septal defect that was repaired at a young age, but otherwise no other remarkable history.

During the physical examination, the adolescent is afebrile and assessed to be well hydrated. Examination of the abdomen reveals tenderness in the epigastric region and the right lower quadrant on light to deep palpation, with radiation to his back on palpation. There are no visible marks or lesions on his abdomen. Physical examination is negative for rebound tenderness, rovsing sign, or psoas sign. The remainder of the examination findings are negative.

Complete blood cell count, liver enzyme levels, pancreatic enzyme levels, and urinalysis results are all within normal limits.

Our patient was asked to observe his hydration status and pain at home and to report any changes. However, he arrived at the emergency department the next day due to increased severity of abdominal pain. The pain had localized into the right lower quadrant. Further imaging revealed the diagnosis.

The differential diagnosis for an adolescent who presents with abdominal pain is broad, including gastrointestinal causes such as gastroenteritis, appendicitis, or constipation and renal causes such as nephrolithiasis or urinary tract infections. With our patient, the more plausible answers were ruled out through laboratory studies and physical examination, and he was assumed to have gastroenteritis based on the history of similar symptoms in his family members. However, with the worsening of his abdominal pain, further diagnostic study became imperative and a computed tomographic (CT) scan of the abdomen was obtained to assess for appendicitis or nephrolithiasis.

The CT scan showed a cecum located midline; the large intestine was on the left side of the abdomen, and the small intestine was on the right ( Figs 1 and 2 ). The appendix was buried deep in the right pelvis, and there was no indication of appendicitis. These findings were consistent with intestinal malrotation. Intestinal malrotation is rare beyond the first year of life. Maintaining a higher index of suspicion in any patient with an acute presentation of severe abdominal pain is imperative because of the severity of potential complications such as bowel obstruction, volvulus, and eventual necrosis. Our patient’s pain is assumed to have been due to compressive effects of the peritoneal bands (Ladd bands), which were irritated by an initial gastroenteritis. He did not have the signs or symptoms of a more severe complication, such as bowel obstruction or volvulus.

Computed tomographic scan of the abdomen showing intestinal malrotation, specifically of the subtype nonrotation. The small bowel is present in the right hemi-abdomen and the large bowel in the left hemi-abdomen. The cecum is midline in the pelvis. Haustra are still present, excluding any sign of obstruction.

Swirling appearance of the mesentery is known as the whirl sign, which is also indicative of malrotation. This computed tomographic scan shows the superior mesenteric vein wrapped around the superior mesenteric artery.

Owing to the severity of the pain, our patient was taken for surgery, specifically, a Ladd procedure and a prophylactic appendectomy. Ladd bands were seen to extend from the cecum to above the duodenum. During the procedure, these bands were lysed, then the mesentery was spread out, and the bowels were rearranged. He tolerated the surgery well and was discharged 3 days after the operation.

His abdominal pain improved after surgery, and he has been doing well at his postoperative checks.

Intestinal malrotation is when the intestines fail to rotate properly in utero. From the fifth to 10th weeks of embryologic development, the small intestine lies in the right aspect of the abdomen, with the ileocecal junction midline, and the large intestine in the left hemi-abdomen. The segments are then pushed out of the abdomen into the umbilical cord. Both segments grow in the first stage of rotation. During the second stage of rotation, the small intestine rotates counterclockwise 270 degrees around the superior mesenteric artery. The remaining intestine is pulled into the abdomen, and the mesentery is fixed to the retroperitoneal space. The large intestine comes in last, with the final segment of the cecum lying anterior to the small intestine in the right lower quadrant.

Nonrotation is the most frequent cause of intestinal malrotation. Nonrotation occurs when the 270-degree rotation does not occur and, thus, the mesentery is not fixed to the retroperitoneal space. Derangements of the second stage of rotation are defined as having the small intestine in the right hemi-abdomen, with the cecum midline in the pelvis, and the large intestine in the left hemi-abdomen.

One percent of the population has intestinal rotation disorders. The incidence decreases with age. Approximately 90% of patients are diagnosed within the first year of their life, with 80% among them within the first month after birth. Due to a delay in diagnosis, the 10% of patients who present beyond that first year after birth can have severe complications.

Symptoms of malrotation are different in infants compared with adolescents. Neonates typically will have bilious emesis. In contrast, children and adults commonly exhibit acute abdominal pain. Some older patients have had chronic abdominal pain that goes unnoticed; others may be asymptomatic before diagnosis. The co-occurrence of intestinal malrotation with congenital cardiac anomalies is a common finding. Twenty-seven percent of intestinal malrotation patients were found to have a concurrent cardiovascular defect such as ventricular septal defect or another minor/major abnormality.

The diagnostic modality of choice is an upper gastrointestinal tract contrast study. This study modality shows any obstruction and depicts the malrotation through contrast media. Sometimes a contrast medium is not needed for diagnosis, as in the case of our patient, where CT scanning was enough to diagnose the malrotation.

Asymptomatic neonates and all symptomatic individuals, regardless of age, go through the Ladd procedure to correct the abnormality. However, the guidelines are not as clear for treatment of children older than 1 year who are asymptomatic. Currently, there is some consensus for performance of the procedure regardless of symptom status because of the severity of the complications or mortality that can occur due to malrotation. The narrow pedicle of the mesentery that forms in malrotation is prone to volvulus and ischemia, leading to complications at any point in an individual’s life. A diagnostic laparoscopy should be performed at the very least and can be therapeutic as well. Removal of the appendix has been suggested to prevent any diagnostic complications on future presentation. Additionally, the Ladd procedure can lyse Ladd bands, which are abnormal fibrous adhesions from the cecum that also arch over the duodenum. Removal of these bands is imperative because they can cause intestinal obstruction and ischemia as well.

Diagnosis of intestinal malrotation should be considered in a patient presenting acutely with severe abdominal pain, especially in a patient with known cardiac anomalies.

Often the symptoms of intestinal malrotation can be vague, and a patient can be asymptomatic for years before presentation.

The diagnostic modality of choice is an upper gastrointestinal tract series, but other imaging, such as computed tomographic scan, can help diagnose the presence of malrotation in emergency situations.

A Ladd procedure should be conducted on a patient even if he/she does not have current symptoms of obstruction due to increased risk of obstruction or complications such as volvulus and gut necrosis with this disease.

This case is based on a presentation by Ms Anjali Garg and Drs Sathyan Sudhanthar and Chioma Okeafor at the 39th Annual Michigan Family Medicine Research Day Conference in Howell, MI, May 26, 2016.

Poster Session: Student and Resident Case Report Poster Presentation

Poster Number: 23

This case is based on a presentation by Ms Anjali Garg and Drs Sathyan Sudhanthar and Chioma Okeafor at the 2016 AAP National Conference and Exhibition in San Francisco, CA, October 22-25, 2016.

Poster Session: Section on Pediatric Trainees Clinical Case Competition

Abdominal Pain in Children: https://www.healthychildren.org/English/health-issues/conditions/abdominal/Pages/Abdominal-Pain-in-Children.aspx

Diarrhea: https://www.healthychildren.org/English/health-issues/conditions/abdominal/Pages/Diarrhea.aspx

For a comprehensive library of AAP parent handouts, please go to the Pediatric Patient Education site at http://patiented.aap.org .

This case was selected for publication from the finalists in the 2016 Clinical Case Presentation program for the Section on Pediatric Trainees of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). Ms Anjali Garg, BS, was a medical student from Michigan State University College of Human Medicine, East Lansing, MI, when she wrote this case report, and she now is a medical resident at Rainbow Babies and Children's Hospital in Cleveland, OH. Choosing which case to publish involved consideration of not only the teaching value and excellence of writing but also the content needs of the journal. Other cases have been chosen from the finalists presented at the 2017 AAP National Conference and Exhibition and will be published in 2018.

Competing Interests

Advertising Disclaimer »

Citing articles via

Email alerts.

Affiliations

- Editorial Board

- ABP Content Spec Map

- Pediatrics On Call

- Online ISSN 1526-3347

- Print ISSN 0191-9601

- Pediatrics Open Science

- Hospital Pediatrics

- Pediatrics in Review

- AAP Grand Rounds

- Latest News

- Pediatric Care Online

- Red Book Online

- Pediatric Patient Education

- AAP Toolkits

- AAP Pediatric Coding Newsletter

First 1,000 Days Knowledge Center

Institutions/librarians, group practices, licensing/permissions, integrations, advertising.

- Privacy Statement | Accessibility Statement | Terms of Use | Support Center | Contact Us

- © Copyright American Academy of Pediatrics

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

DIARRHEA IN CHILDREN

Sep 04, 2014

4.61k likes | 17.92k Views

DIARRHEA IN CHILDREN. Maria Naval C. Rivas Department of Pediatrics The Medical City. SOURCES. Nelson’s Textbook of Pediatrics 18 th edition World Health Organization: A Manual for Physicians and Other Senior Health Workers, 2005. DEFINITION.

Share Presentation

- watery diarrhea

- acute diarrhea

- dry mucous membranes

- acute diarrhea 2 weeks

Presentation Transcript

DIARRHEA IN CHILDREN Maria Naval C. Rivas Department of Pediatrics The Medical City

SOURCES • Nelson’s Textbook of Pediatrics 18th edition • World Health Organization: A Manual for Physicians and Other Senior Health Workers, 2005

DEFINITION • passage of unusually loose or watery stools • at least 3 times in a 24 hour period • Acute diarrhea: < 2 weeks • Chronic diarrhea: > 2 weeks

EPIDEMIOLOGY • 2nd leading cause of morbidity • 1,135 cases per 100,000 population • 6th leading cause of mortality • 5.3 deaths per 100,000 population • 1000M episodes of diarrhea/year in children <5y • 5M deaths in <5y • 80% deaths in 1st 2y of life (1/3 of all deaths) Sources: Carlos M.D., C. & Saniel M.D., M. Etiology and Epidemiology of Diarrhea. Research Institute for Tropical Medicine : Philippine Health Statistics, 2000

APPROACH TO A CHILD WITH ACUTE DIARRHEA Main Objectives 1. assess degree of dehydration and provide fluid and electrolyte replacement 2. prevent spread of enteropathogen 3. in select episodes, determine etiologic agent and provide specific therapy if indicated

APPROACH TO A CHILD WITH ACUTE DIARRHEA Pertinent Data oral intake frequency of stools volume of stools presence of blood or mucus in stool general appearance & activity of child frequency of urination

APPROACH TO A CHILD WITH ACUTE DIARRHEA others: day care attendance recent travel to a diarrhea endemic area use of antibiotics exposure to contacts with similar symptoms intake of seafood, uncooked meat, unpasteurized milk, unwashed vegetables, contaminated water systemic sx: fever, vomiting, seizure

APPROACH TO A CHILD WITH ACUTE DIARRHEA Degree of Dehydration MILD DEHYDRATION (3-5%) - normal or increased pulse, decreased urine output, thirsty, normal physical examination MODERATE DEHYDRATION (7-10%) - tachycardia, little or no urine output, irritable/ lethargic, dry mucous membranes, mild tenting of skin, delayed capillary refill, cool and pale

APPROACH TO A CHILD WITH ACUTE DIARRHEA Degree of Dehydration SEVERE DEHYDRATION (10-15%) - rapid and weak pulse, decreased blood pressure, no urine output, very sunken eyes and fontanel, no tears, dry mucous membranes tenting of the skin, very delayed capillary refill, cold and mottled

ASSESSMENT OF DIARRHEA PATIENTS FOR DEHYDRATION

APPROACH TO A CHILD WITH ACUTE DIARRHEA Treatment Plan A - home therapy to prevent dehydration and malnutrition • Give the child more fluids than usual • ORS solution • salted drinks (e.g. salted water, salted yoghurt drink) • vegetable or chicken soup with salt • Give supplemental zinc (10-20mg) for 10-14 days • Continue to feed the child

APPROACH TO A CHILD WITH ACUTE DIARRHEA • Take child back to health worker if there are signs of dehydration or other problems • starts to pass many stools • repeated vomiting • becomes very thirsty • eating or drinking poorly • develops a fever • has blood in the stool • child does not get better in 3 days

APPROACH TO A CHILD WITH ACUTE DIARRHEA Treatment Plan B • oral rehydration therapy with ORS in a health facility • monitoring progress of oral rehydration • supplemental zinc (10-20mg) for 10-14 days • food should not be given during initial 4-hour rehydration period • breastmilk may be given continuously

Treatment Plan B: Approximate amount of ORS to give in the initial 4 hours

APPROACH TO A CHILD WITH ACUTE DIARRHEA Reduced osmalarity ORS mmol/liter Sodium 75 Chloride 65 Glucose 75 Potassium 20 Citrate 10 TOTAL OSMOLARITY 245

APPROACH TO A CHILD WITH ACUTE DIARRHEA Treatment Plan C • rapid intravenous rehydration • may give oral ORS if child can already drink - usually after 1-4 hours • monitoring progress of IV hydration • if IV therapy not available, give ORS by NGT at 20cc/kg/hr x 6 hrs. • manage electrolyte disturbance

IV Treatment of Children & Adults with Severe Dehydration

IV Treatment of Children & Adults with Severe Dehydration 1. Restore intravascular volume • normal saline: 20ml/kg over 20 mins • repeat until intravascular volume is restored 2. Calculate 24-hr water needs • calculate maintenance water • 0-10kg 100ml/kg • 11-20kg 1000ml + 50ml/kg for each kg > 10kg • > 20kg 1500ml + 20ml/kg for each kg > 20kg • calculate deficit water • Percent dehydration x weight

IV Treatment of Children & Adults with Severe Dehydration 3. Calculate 24-hour electrolyte needs • calculate maintenance sodium and potassium • calculate deficit sodium and potassium • Na deficit = water deficit x 80 mEq/L • K deficit = water deficit x 30 mEq/L 4. Select an appropriate fluid • nornal saline or Ringer lactate 5. Replace any ongoing losses as they occur

APPROACH TO A CHILD WITH ACUTE DIARRHEA Electrolyte Disturbances • Hypernatremic Dehydration (serum Na > 150 mmol/L) - due to drinks with excessive sugar or salt - e.g. soft drinks, commercial fruit drinks, concentrated infant formula - s/sx: extreme thirst convulsions

APPROACH TO A CHILD WITH ACUTE DIARRHEA Electrolyte Disturbances • Hyponatremic Dehydration (serum Na < 130 mmol/L) - due to drinking mostly water or drinks with little salt - common in Shigellosis and in severe malnutrition with edema - s/sx: lethargy

APPROACH TO A CHILD WITH ACUTE DIARRHEA Electrolyte Disturbances • Hypokalemia (serum K+ < 3 mmol/L) - s/sx: muscle weakness, paralytic ileus, cardiac arrhythmia, impaired kidney function

CLINICAL TYPES OF DIARRHEA • Acute Watery Diarrhea • Acute Bloody Diarrhea • Persistent Diarrhea

ACUTE WATERY DIARRHEA Viruses Rotavirus Astrovirus Adenovirus Calcivirus ( e.g. Norwalk agent )

ACUTE WATERY DIARRHEA Pathogenesis - destroy villus tip cells in the SI • imbalance in ratio of intestinal absorption and secretion • malabsorption of complex carbohydrates, sp. lactose - gastric mucosa is not affected - greatly enhances intestinal permeability to macromolecules increase risk of food allergies

ACUTE WATERY DIARRHEA Pathogenesis - increased vulnerability of infants • decreased intestinal reserve function • lack of specific immunity • decreased non-specific host defense mechanisms (e.g. gastric acid, mucus)

ACUTE WATERY DIARRHEA Rotavirus - most common viral cause; RNA virus - > 125 M of cases / yr in < 5 y/o - 600,000 deaths per year - most severe in ages 3mos – 24mos - transmission: fecal-oral route days before and after the clinical illness

Rotavirus in the Philippines - based on 2005 data of PPS - most common viral cause - 3,700 deaths from total of 14,500 deaths related to childhood diarrhea - most severe in ages 3mos – 24mos - 65% of diarrhea-related hospital admissions

Clinical Manifestations incubation: < 48 hours mild to moderate vomiting & fever onset of frequent, watery diarrhea Complications: dehydration, severe and prolonged symptoms in malnourished and immunocompromised children

Diagnosis - clinical and epidemiological features - enzyme immunoassays : 90% specificity/ sensitivity - stool exam : free of blood and leukocytes Treatment - rehydration - probiotics (Lactobacillus species) , zinc - no role for antiviral nor antibacterial drugs - no role for antiemetics nor antidiarrheal drugs

Prognosis - after initial infection, 38% protection against subsequent infection 77% against diarrhea 87% against severe diarrhea Prevention - good hygiene and isolation - breastfeeding - vaccine: > 80% protection against severe disease

Differential Diagnosis 1. Astrovirus – RNA virus - milder with less significant dehydration 2. Norwalk virus – RNA virus - short incubation period (<12 hrs) - vomiting and nausea tend to predominate - clinical picture resembles “food poisoning” by S. aureus

Differential Diagnosis 3. Adenovirus – DNA virus - 5-9% of diarrhea in children - mainly a respiratory virus that grows well in the epithelium of SI - diarrhea is watery but of longer duration ( 10-14 days )

Differential Diagnosis 3. Adenovirus - may be assoc with conjunctivitis, myocarditis, hemorrhagic cystitis, intussusception, encephalomyelitis - transmission: respiratory fecal-oral routes - diagnosis: virus detection by culture or PCR increase in antibody titers

ACUTE WATERY DIARRHEA Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) - major cause of infantile diarrhea - important etiologic agent of traveler’s diarrhea - 20-30% of diarrhea worldwide and in the Philippines

Pathogenesis - colonization of SI and subsequent elaboration of enterotoxins - enterotoxins: heat-labile (LT) heat- stable (ST) - require a large inoculum of organisms to induce disease - mode of transmission: food or water-borne

ACUTE WATERY DIARRHEA Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) - major cause of infant diarrhea and mortality in < 2 years - pathogenesis: “attaching and effacing lesion” • intimate attachment of bacteria to epithelial surface and effacement of host cell microvilli

Clinical Manifestations - explosive, watery, non-bloody, non-mucoid - abdominal pain - nausea and vomiting - +/- fever - self-limited: 3-5 days but occassionally > 1week

Diagnosis - clinical features seldom distinctive - laboratory studies not readily available: • isolation of bacteria from stool cultures • biochemical criteria (fermentation patterns) • tissue culture • identification of specific virulence factors • detection of antibodies

Treatment - rehydration - early refeeding - history of travel from developing country - DOC: Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole Prevention - prolonged breastfeeding - personal hygiene - proper food and water handling - public health measures

ACUTE WATERY DIARRHEA CHOLERA (Vibrio cholerae) - 5-7M cases and > 100,000 deaths/yr. - an EMERGENCY!! - latest epidemic in 1990s in Americas death rate = 12,000 deaths/70,000 cases -V. cholerae is a gram-negative rod with a polar, flagellum - 2 strains: O1 and O139

Pathogenesis colonization of SI by > 10 viable vibrios production of cholera toxin (CT) entry of toxin into intestinal epithelial cells high cAMP level decrease absorption of Na and Cl by villous cells active secretion of Cl by crypt cells 8

Clinical Manifestations - most are asymptomatic - ¼ with mild to moderate disease - 2-5% with severe disease - hallmark: massive loss of fluids and electrolytes - incubation: 6 hours – 5 days - watery diarrhea, vomiting, low-grade fever - severe: profuse, painless, watery diarrhea with rice-water consistency and fishy odor

Diagnosis - primarily clinical - laboratory confirmation during epidemics • culture by thiosulfate-citrate-bile-sucrose(GOLD STANDARD) • appear as large, yellow colonies against bluish-green medium • culture by tellurite-taurocholate-gelatin agar • small, opaque colonies with zone of cloudiness around them

Treatment - fluid and electrolyte replacement - refeeding does not affect purging rates or duration of illness - success of ORT shown in Peru epidemic in 1991 with <1% mortality - antibiotics for moderate or severe disease DOC: tetracycline and doxycycline resistant strains: TMP-SMZ, Erythromycin, Furazolidone

Complications - dehydration: hypoglycemia acute tubular necrosis - hypokalemia: cardiac arrhythmia paralytic ileus - sodium disturbance: lethargy seizures coma

Prevention - prolonged breastfeeding - safe food and water handling - improved vaccine is priority - Cholera vaccine • 50% efficacy, highly reactogenic, does not protect against O139 vibrios • used only for very high-risk persons (e.g. achlorhydria) with high probability of exposure • not recommended for < 6 mos old

ACUTE WATERY DIARRHEA Staphylococcus aureus - most common cause of food poisoning - ingestion of pre-formed enterotoxins sudden, severe vomiting watery diarrhea - treatment: supportive - prevention: • eat/refrigerate prepared food immediately • exclude those with Staphylococcal skin infections from food handling or preparations 2-7 hours

ACUTE WATERY DIARRHEA GIARDIASIS (Giardia lamblia) - frequently identified during outbreaks assoc with drinking water - high prevalence during childhood - role of child-care centers - transmission: water and food borne low infectious dose extended periods of cyst shedding resistant to chlorination and UV light irradiation

- More by User

Diarrhea. Definition. Increased liquidity, frequency or decreased consistency of stools. Mechanisms. Osmotic Diarrhea Secretory Diarrhea Deranged Motility Exudation. Osmotic Diarrhea. results from poorly absorbable osmotically active solutes in the gut lumen

1.86k views • 41 slides

DIARRHEA. MODULE FOR TEACHERS. OBJECTIVES. Define diarrhea Present major causes and symptoms associated with diarrhea Provide guidance as to when to seek medical attention for diarrhea Students should know: When diarrhea requires medical attention

959 views • 23 slides

CHRONIC DIARRHEA IN CHILDREN

CHRONIC DIARRHEA IN CHILDREN. Asaad M. A. Abdullah Assiri Professor of Pediatrics & Consultant Pediatric Gastroenterologist Department of Pediatrics King Khalid University Hospital. OBJECTIVES.

2.81k views • 113 slides

Evidence based Medicine on Acute Diarrhea in Children

Evidence based Medicine on Acute Diarrhea in Children. Dr.H.K.Takvani, MD Ped., FIAP

1.09k views • 39 slides

diarrhea. intro. Generally > 3 stools per day daily stool weight exceeding 200 grams Up to 5% of ER visits Four mechanisms: increased intestinal secretion decreased intestinal absorption increased osmotic load abnormal intestinal motility . Clinical features. History Camping Travel

478 views • 16 slides

Diarrhea . Brian Rempe MD. Goals. Define Diarrhea Statistics Approach to the Patient Who to work up How to work them up Who to treat and with what. Definitions. Any increase in daily stool weight above normal –roughly 200g per day (in men)

1.26k views • 73 slides

DIARRHEA. Dr. Therese C. Macatula Section of Gastroenterology Department of Medicine The Medical City. What is diarrhea ?. Diarrhea is caused by an imbalance in the physiologic mechanisms of the GI tract, resulting in impaired absorption and excessive secretion

1.6k views • 53 slides

Diarrhea. A messy subject. Case. A 1 year old girl is brought to clinic with 3 days of watery brown diarrhea, vomiting, and irritability. On exam the child is lethargic, afebrile, with sunken eyes and a weak pulse of 140/minute. Which of the following is the best management plan?

783 views • 26 slides

Nutrition For Children With Diarrhea

Nutrition For Children With Diarrhea. Why is diarrhea a concern for parents?. Dehydration, poor nutrition, and poor health 200,000 hospitalizations per year in U.S. 300 deaths per year in U.S. How can I tell if my child has diarrhea?.

491 views • 16 slides

Diarrhea in ICU setting

Diarrhea in ICU setting. B89401129 楊展輝. Patient. 蘇 xx 娥 4226891 72 y/o Female ER 10/16 4:46pm acute onset chest pain radiating to back + cold sweating since that afternoon 4pm T/P/R 35.9/96/24 BP 194/80mmHg Rectal CA s/p OP, C/T and cholecystectomy at 和信 H. 10+ yrs ago

525 views • 23 slides

Rehydration in acute diarrhea

Rehydration in acute diarrhea. Jorge Amil Dias Porto, Portugal [email protected]. Water and electrolyte movement across the intestinal mucosa. K Hodges and R Gill, Gut Microbes, 2010. K Hodges and R Gill, Gut Microbes, 2010. K Hodges and R Gill, Gut Microbes, 2010.

607 views • 33 slides

Prebiotics for acute diarrhea in adults and children

Prebiotics for acute diarrhea in adults and children. Rüdiger Schultz, MD, PhD Pediatrician Ilembula Hospital. Probiotics. The definition of Probiotics: -Living micro-organisms that, upon ingestion in certain numbers, exert health benefiting effects beyond inherent general nutrition

328 views • 11 slides

Antibiotics associated Diarrhea ( Nosocromial Diarrhea)

Antibiotics associated Diarrhea ( Nosocromial Diarrhea). Thananont Krittayawiwat MD. Donchedi Hospital. เชื้อสาเหตุ. Clostridium difficile Gram Positive, Normal commensal organism in Human Gut Major Source : Nosocromial Diarrhea Pseudomembranous Colitis

796 views • 12 slides

DIARRHEA. A pathophysiological Approach to Diagnosis and Treatment Prof. J. Zimmerman Gastroenterology Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center. Diarrhea = Increased loss of water from the GI tract. Diarrhea is a common complaint.

690 views • 44 slides

DIARRHEA. WHAT TO ORDER. Criteria for Conducting Stool Studies:. Perform a complete history which includes the following: Travel history Sexual practices Antibiotics in the past 2 months or usage any other medications

1.16k views • 29 slides

DIARRHEA. What is DIARRHEA ?. MOST CAUSATIVE AGENT. Pathophysiology: OSMOTIC DIARRHEA. SECRETORY DIARRHEA. Agents inducing SECRETORY DIARRHEA. INFLAMMATORY & INFECTIOUS DIARRHEA. PATHOGENS ASSOCIATED W/ INFECTIOUS DIARRHEA. DIARRHEA W/ DERANGED MOTILITY. EPIDEMIOLOGY.

1.28k views • 23 slides

541 views • 41 slides

405 views • 33 slides

Diarrhea in Cancer Patients

Diarrhea in Cancer Patients. By. Abdallah H. Elsheref. Diarrhea. WHO Definition: The passage of more than 3 unformed stools in 24 hours. Or Frequent passage of loose stools with urgency. NCI Grading of Diarrhea. Causes of diarrhea in cancer paients. Chemotherapy induced diarrhea

566 views • 23 slides

136 views • 11 slides

A Person is considered to have diarrhea if a person has loose bowel movement three or more times a day. Diarrhea is a condition in which loose, watery stools (bowel movement) appear. www.vaidjagjitsingh.com

480 views • 1 slides

- My presentations

Auth with social network:

Download presentation

We think you have liked this presentation. If you wish to download it, please recommend it to your friends in any social system. Share buttons are a little bit lower. Thank you!

Presentation is loading. Please wait.

To view this video please enable JavaScript, and consider upgrading to a web browser that supports HTML5 video

Chapter 5 Diarrhoea Case I

Published by Savanna Passon Modified over 9 years ago

Similar presentations

Presentation on theme: "Chapter 5 Diarrhoea Case I"— Presentation transcript:

Diarrhoea and Vomiting in Children Under 5yrs

Diarrhoea and Dehydration Paediatric Palliative Care For Home Based Carers Funded by British High Commission, Pretoria Small Grant Scheme.

Danger Signs in Children Paediatric Palliative Care For Home Based Carers Funded by British High Commission, Pretoria Small Grant Scheme.

Chapter 6 Fever Case I.

Nutrition For Children With Diarrhea

Nurul Sazwani. Definition : a state of negative fluid balance decreased intake increased output fluid shift.

Chapter3 Problems of the neonate and young infant - Neonatal resuscitation.

Chapter 9 Common surgical problems Burns. Case study: Alisher Alisher, a 10 months old girl was brought to the district hospital by her mother. At presentation.

Control of Diarrheal Diseases (CDD) BASIC TRAINING FOR BARANGAY HEALTH WORKERS Calasiao, Pangasinan.

Diarrhea Dr. Adnan Hamawandi Professor of Pediatrics.

DIARRHEA and DEHYDRATION

HAFIZ USMAN WARRAICH Roll#17-C Diarrhea and Dehydration Dr Shreedhar Paudel 25/03/2009.

Doug Simkiss Associate Professor of Child Health Warwick Medical School Management of sick neonates.

Chapter 5 Diarrhoea Case II

Chapter 4 Cough or difficult breathing Case I. Case study: Faizullo Faizullo is a 3-year old boy presented in the hospital with a 3 day history of cough.

Chapter 6 Fever (and joint pain). Case study: Mere Mere is an 11 year old girl brought to hospital after 4 days of fever. She has pain in her right knee.

Chapter 7 Severe Malnutrition

Chapter 4 Cough or Difficult Breathing Case II. Case study: Ratu 11 month old boy with 5 days of cough and fever, yesterday he became short of breath.

IMCI Dr. Bulemela Janeth (Mmed. Pead) 1IMCI for athens.

About project

© 2024 SlidePlayer.com Inc. All rights reserved.

- Open access

- Published: 30 November 2021

Determinants of diarrheal diseases among under five children in Jimma Geneti District, Oromia region, Ethiopia, 2020: a case-control study

- Dejene Mosisa 1 ,

- Mecha Aboma 1 ,

- Teka Girma 1 &

- Abera Shibru 1

BMC Pediatrics volume 21 , Article number: 532 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

10 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Globally, in 2017, there were nearly 1.7 billion cases of childhood diarrheal diseases, and it is the second most important cause of morbidity and mortality among under-five children in low-income countries, including Ethiopia. Sanitary conditions, poor housing, an unsanitary environment, insufficient safe water supply, cohabitation with domestic animals that may carry human pathogens, and a lack of food storage facilities, in combination with socioeconomic and behavioral factors, are common causes of diarrhea disease and have had a significant impact on diarrhea incidence in the majority of developing countries.

A community-based unmatched case-control study was conducted on 407 systematically sampled under-five children of Jimma Geneti District (135 with diarrhea and 272 without diarrhea) from May 01 to 30, 2020. Data was collected using an interview administered questionnaire and observational checklist adapted from the WHO/UNICEF core questionnaire and other related literature. Descriptive, bivariate, and multivariate binary logistic regression analyses were done by using SPSS version 20.0.

Sociodemographic determinants such as being a child of 12–23 months of age (AOR 3.3, 95% CI 1.68–6.46; P < 0.05) and mothers’/caregivers’ history of diarrheal diseases (AOR 7.38, 95% CI 3.12–17.44; P < 0.05) were significantly associated with diarrheal diseases among under-five children. Environmental and behavioral factors such as lack of a hand-washing facility near a latrine (AOR 5.22, 95% CI 3.94–26.49; P < 0.05), a lack of hand-washing practice at critical times (AOR 10.6, 95% CI 3.74–29.81; P < 0.05), improper domestic solid waste disposal (AOR 2.68, 95% CI 1.39–5.18; P < 0.05), and not being vaccinated against rotavirus (AOR 2.45, 95% CI 1.25–4.81; P < 0,05) were found important determinants of diarrheal diseases among under-five children.

The unavailability of a hand-washing facility nearby latrine, mothers’/caregivers’ history of the last 2 weeks’ diarrheal diseases, improper latrine utilization, lack of hand-washing practice at critical times, improper solid waste disposal practices, and rotavirus vaccination status were the determinants of diarrheal diseases among under-five children identified in this study. Thus, promoting the provision of continuous and modified health information programs for households on the importance of sanitation, personal hygiene, and vaccination against rotavirus is fundamental to decreasing the burden of diarrheal disease among under-five children.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines diarrhea as the passage of three or more loose or liquid stools per day due to an abnormally high fluid content of stool or an abnormal increase in daily stool fluidity, frequency, and volume from what is considered normal for an individual and is caused by bacterial, viral, protozoa, and parasitic organisms [ 1 ]. In low-income countries, the two most common etiological agents of moderate-to-severe diarrhea are rotavirus and Escherichia coli [ 2 ]. Diarrhea is more common when there is a lack of adequate sanitation and hygiene, safe water supply for drinking, cooking, and cleaning, improper feeding practices, and a poor housing situation [ 3 ].

Globally, in 2017, a large number of deaths and more than 1.7 billion cases of childhood diarrheal disease occur every year. Sub-Saharan African and South Asian countries account for roughly 80% of morbidity and mortality. According to 2018 WHO reports, in each year, diarrhea kills more than 525, 000 under-5 years’ children. Five countries accounted for 50 % of the deaths, one of which was Ethiopia [ 4 , 5 ]. Despite the global achievement in the reduction of all-cause of diarrheal diseases, particularly mortality, in the past 30 years, worldwide diarrhea remains the second most important cause of death due to infections among children under 5 years of age [ 6 ]. Likewise, in developing countries, childhood mortality is almost 10 times higher than in developed nations. In Africa, it is estimated that children below 5 years old experience a minimum of five episodes of diarrhea a year and about 800,000 children succumb to diarrhea annually [ 7 ]. Similarly, diarrheal disease is the most important community health problem in Sub-Saharan African countries and is accountable for greater than 50% of childhood illnesses and 50–80% of childhood deaths in the countries [ 1 , 8 ]. Ethiopia is one of the emerging sub-Saharan-African countries contributing to the tall burden of diarrheal illness and death [ 9 ]. In the year of 2016 alone, generally, 1 in every 15 children dies before reaching their fifth birthday. Among these deaths, diarrhea kills almost fifteen thousand under-five children in Ethiopia [ 10 ]. In Ethiopia in particular, diarrheal diseases alone accounted for 23% of the causes of child mortality, which is greater than the annual deaths due to malaria, HIV/AIDS and measles all together [ 11 , 12 ]. These were due to living conditions, high incidence of illness, lack of safe drinking water supply, sanitation and, hygiene, as well as poorer overall health and nutritional status [ 1 ]. In spite of all advances in health technology, improved management, and increased use of oral rehydration therapy in the past decades, diarrheal diseases still continue to be a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Moreover, there is no dramatic change in evidence about whether the health extension program has had an effect on the risk factors of childhood diarrhea [ 13 , 14 ].

According to the Ethiopia Demographic and Health Surveys (EDHS), under-five mortality declined from 166 deaths per 1000 live births in 2000 to 67 deaths per 1000 live births in 2016. This indicates a 60% decrease in under-five mortality over a period of 16 years. However, the under-five mortality rate in the Oromia regional state was 79 per 1000, which is higher than the national mortality rate. According to this survey, there was no significant change in the prevalence of diarrheal disease among under-five children, which has dropped only from 13% in 2011 to 12% in 2016 [ 10 ].

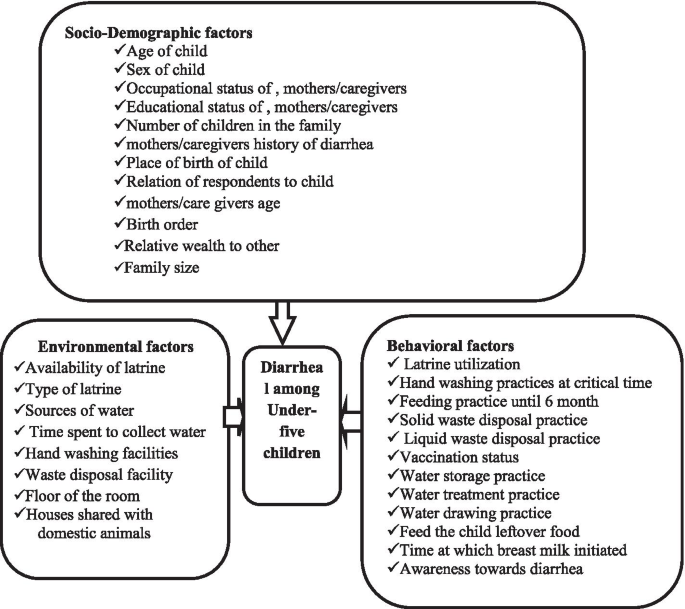

According to the 2019/2020 Jimma Geneti District Health Office performance report, the prevalence of diarrheal diseases among under-five children is 13.5%. Despite the emphasis given by the Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health, respective regional health offices, Zonal department, and district health offices to improve child health, there is still higher morbidity and mortality among under-five children due to diarrheal disease, specifically in Jimma Geneti District [ 15 ]. Generally, the burden of diarrheal diseases in developing countries is associated with different factors. Evidences revealed that, there is a significant variation in the determinants of diarrhea in Ethiopia, i.e., the determinants of diarrhea identified so far by different scholars was not uniform across the districts. Most of the research conducted in Ethiopia was cross-sectional, institutional-based, and used EDHS data to determine its prevalence. While there are insufficient reports on determinants of under-five diarrheal disease in the studied region, and there is no similar study in Jimma Ganti District, where the prevalence of diarrhea is high and higher child mortality and morbidity due to diarrhea were registered. Thus, to achieve the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) targeting childhood mortality reduction, operational research designed to identify determinants of diarrhea across different geographical settings is required. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to identify determinants of diarrheal disease among under-five children in the Jimma Geneti District, Oromia Region, Ethiopia, which has important public health implications for planning suitable interventions and appropriate strategies to decrease the impact of diarrheal disease [Fig. 1 ].

Conceptual framework on Determinants of Diarrheal Diseases among under-five children in Jimma Geneti District, Oromia regional state, Western Ethiopia, May, 2020 [ 16 , 17 ]

Study area and period

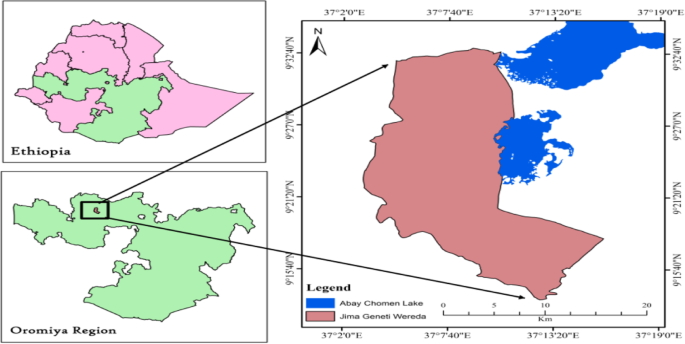

The study was conducted in Jimma Geneti District, from May 01 to 30, 2020. Jimma Geneti District is located in Horo Guduru Wollega Zone, Oromia Regional state, the western part of Ethiopia, 273 km from the Capital City, Addis Ababa. In the district there were 44,278 males and 46,086 females, among whom 5755 (6.4%) were urban and 84,609 (93.6%) were rural, and 18,826 total households. There are 19,998 women of reproductive age and 14,848 under-five children [ 15 ] [Fig. 2 ].

Location map of Jimma Geneti District: Nation, Region and, District, Oromia Regional state, Western Ethiopia, May, 2020 [ 15 ]. Source: - Ethiopian Map Agency 2007 [Using GIS Arc map 10.3.1 version 15]

Study design sample size and sampling procedures

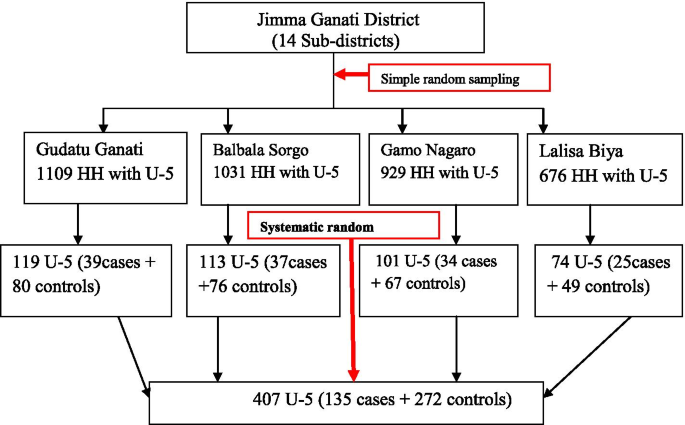

A community-based unmatched case-control study design was conducted to assess determinants of diarrheal diseases among under-five children. The district had 14 kebeles (the district’s smallest administrative unit), four of which were chosen by lottery. The households who had under-five children and residents of the study area in randomly selected kebeles were a sampling unit of this study. While randomly selected under-five children in the households in the preceding 2 weeks before the survey, with a report of diarrhea disease, for cases and without a report of diarrhea disease for controls, were the study units included in this study.

The sample size was determined using OpenEpi’s unmatched case-control model with the assumptions of power = 80%; confidence level = 95%; case to control ratio = 1:2; P1 = proportion of diarrheic children who had not used latrine for disposal of child feces, P2 = proportion of non-diarrheic children who had not used latrine for disposal of child feces as the main predictors of the outcome, which was 33.0 and 19.1% among cases and controls respectively [ 13 ]. And an adjusted odds’ ratio (AOR = 2.09) and 10% of none response rates were considered. Finally, a 407 (135 for cases and 272 for controls) sample size was generated.

A total of 3745 households with under-five children in the selected kebeles were obtained from the family folders of health extension workers (HEWs). Cases and controls were identified by the census through a house-to-house survey, and then 156 under-five children with diarrhea and 3589 under-five children without diarrhea in the selected kebeles were registered and coded with the guidance of HEWs. The case was confirmed from reports of mother’s/caregiver’s history of last 2 weeks period of diarrhea. Afterward, the calculated sample size for control was proportionally allocated to the size of household with under-five children for each selected kebeles. Finally, a total of 272 controls were selected by using the systematic random sampling technique, and all the registered 135 cases who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were included in the study [Fig. 3 ]. Both cases and controls were recruited from different households, and when there were more than one under-five child in the same household, the youngest child was included in the study since they are more vulnerable to the outcome variable [ 1 ].

Diagrammatic presentation of sampling technique of under-five children in Jimma Geneti district, Oromia Regional state, Western Ethiopia, May, 2020

Data collection tool and personnel

Data was collected by eight trained B.Sc. nurses under the supervision of four health officers and with guidance of HEWs using a pretested structured questionnaire adapted from the WHO/UNICEF core questionnaire and other related literature [ 16 , 17 , 18 ]. In addition, an observational checklist was used to observe water storage containers, the presence or absence of feces around the latrine and compound, availability, and types of the latrine, and the presence or absence of hand-washing facilities nearby the latrine.

Data quality control and analysis

Data quality was assured through pre-test on 5% of the total sample size in different sub-districts of the study area. Data collectors and supervisors were trained for 1 day by the principal investigator on the study instruments and consent form, how to interview and data collection procedures. The data collection processes were closely supervised by supervisors and investigators. Before data entry, the questionnaires were checked for completeness, consistency, and correction measures made by supervisors and investigators. Then, the data was coded and entered into Epi Info and was exported to SPSS for data processing, cleaning, and analysis. Descriptive analysis like frequency and percentage was carried out to describe sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents and environmental and behavioral determinants of diarrhea among under-five children and results were presented in texts and tables. Bivariate and multivariate analyses were done using a binary logistic regression model to identify determinants of diarrheal diseases among under-five children. Candidate variables for the final model (multivariate logistic regression) were identified using a bivariate logistic regression model with P < 0.25. Multivariate logistic regression was used to determine the independent effect of each explanatory variable on the study variable, with significance set to P < 0.05.

The Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit ( P -value = 0.348) was checked to test for model fitness. The independent variables were tested for multi-co-linearity using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and the Tolerance tests, and no variables were found to have a VIF greater than 2 to be omitted from the analysis.

Terms and operational definition

Is defined as having three or more loose or watery stools in a 24-h period in the household within the two-week period before the survey is administered, as reported by the mothers/caregivers of the child [ 10 ].

Mothers/caregivers

Parried-child mother/caregivers, a person who is responsible for taking care of a child; the person can be a relative of the child or a non-relative.

Relative wealth to others

Households are categorized based on the number and kinds of domestic animals they own, ranging from a hen to a cow or ox, in addition to farmland ownership, with the amount of productivity per year and housing characteristics such as consumer goods, toilet facilities, and flooring materials. Each household was ranked by their living standard, and then the distribution was divided into three categories: model, middle, and poor [ 19 ].

Improved water sources

It includes piped water into the dwelling, piped water to the yard, tube well, or borehole, public standpipes, protected dug wells, protected springs, and rainwater. An improved source is one that is likely to provide “safe” water [ 6 ].

Improper waste disposal

Is the disposal of waste in a way that has an impact on the environment. Examples include littering, hazardous waste that is dumped into the ground, and not recycling and disposing of refuse in open fields [ 6 ].

Hand-washing during the critical time

Refers to mothers’/caregivers’ hand-washing practice after the utilization of the latrine, after helping their child defecate, before food preparation, and before self-feeding and child-feeding. If yes, for all critical times of hand-washing, it is concluded as good, otherwise poor practice.

Proper latrine utilization

Households with functional latrines and at least no observable feces in the compound, observable fresh feces through the squat hole, and the footpath to the latrine were uncovered with grasses.

Good awareness towards diarrhea

mothers/caregivers who mentioned at least three causes of diarrhea such as microorganisms, flies, contaminated food/water, three ways of transmission such as by eating contaminated food, by flies, and by physical contact with the diseased person and its prevention such as vaccination of rotavirus vaccine, early initiation, and exclusive breastfeeding, use safe water for drinking and food preparation, proper waste disposal.

Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants

Totally, 407 under five-children (135 cases and 272 controls) were sampled for this study. However, data gathered from 399 under-five children of study participants (127 among cases and 272 among controls) showed a response rate of 94% for cases and 100% for controls. Among those studied children, 76 (59.8%) of cases and 156 (57.4%) of controls were male children and 44 (34.6%) cases and 128 (47.1%) controls were found in the age group of 24–59 months. The mean (+SD) of the age of cases and controls was 18.79 (+ 5.2) and 21.09 (+ 5.9) months respectively. Among these children, 107 (84.3%) of cases and 231 (84.9%) of controls were born at the health facility.

Of all the mothers/caregivers, 118 (92.9%) among cases and 266 (97.8%) among controls were biological mothers. Out of the total mothers/caregivers, 106 (81.9%) cases and 247 (87.9%) controls were found in the age group of 25–35 years.

The majority of mothers/caregivers, 108 (85%) cases, and 201 (73.9%) controls were housewives by occupation. Most of the mothers/caregivers, 115 (90.6%) cases, and 255 (93.8%) controls were married. More than half of the mothers/caregivers in both study groups; 69 (54.3%) cases and 151 (55.5%) controls, had no formal education.

Out of the total, 90 (70.9%) of the mothers/caregivers of the cases and 196 (72.1%) of the controls were protestant religious followers. By ethnicity, approximately 126 (99.2%) of cases and 267 (98.2%) of controls were Oromo.

Regarding the family size of the households in both groups, 62 (48.8%) of cases and 139 (51.1%) of controls were had > = 5 members and the number of under-five children in the households in both groups was one among more than half of the households, 65 (51.2%) of cases and 153 (56.2%) of controls.

Among all households, 34 (26.8%) mothers/caregivers of cases and 14 (5.1%) mothers/caregivers of controls had last two-week history of diarrhea (Table 1 ).

Environmental related characteristics of study participants respondents

The majority of households, 117 (92.1%) among cases and 258 (94.9%) among controls, had latrine facilities in their compound. From these households that had latrines, more than half, 66 (56.4%) among cases and 160 (62.0%) among controls, used pit latrines without a slab.

About 92 (72.4%) of cases and 201 (73.9%) of controls of households were used improved sources of water supply, and 36 (28.3%) of cases and 87 (32.0%) of controls of households traveled more than 30 min to collect water from the sources.

More than half of households with latrines, 73 (57.5%) of cases and 163 (59.9%) of controls, had a hand-washing facility, and 70 (55.1%) of cases and 163 (59.9%) of controls had a waste disposal facility in their compound.

The majority of the floors of the households, 94 (74.0%) of cases, and 214 (78.7%) of controls, were made of soil. About 112 (88.2%) of cases and 258 (84.9%) of controls of households had separated kitchens from their houses. From the total households, 104 (81.9%) of the cases and 251 (92.3%) of the controls were not shared houses with domestic animals (Table 2 ).

Behavioral characteristics of study participants

Regarding behavioral characteristics’ majority of households, 75 (59.1%) among cases, and 220 (80.9%) among controls were properly practiced latrine utilization. Greater than three fourth, 102 (80.3%) among cases and 265 (97.4%) among controls of respondents have washed their hands at critical times. Sixty-four (50.4%) of households from cases and 176 (64.7%) of households from controls were disposed domestic solid refuse properly, while 65 (51.2%) from cases and 113 (41.5%) from controls were disposed of liquid waste improperly.

More than half of under-five children, 73 (62.9%) from cases and 198 (77.6%) from controls, were vaccinated for the measles vaccine. And 73 (57.5%) of cases and 208 (76.5%) of controls were received rotavirus vaccine. From all mother/caregivers, 78 (61.4%) among cases and 171 (62.9%) among controls had good awareness towards diarrheal morbidity (Table 3 ).

Determinants of diarrheal disease among under-five children

The result of backward likelihood multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that age of child, availability of hand-washing facility, nearby latrine, mothers’/caregivers’ history of the last 2 weeks’ diarrheal disease, latrine utilization, hand-washing practice during a critical time, domestic solid waste refusal practice, and rotavirus vaccination status showed that they were statistically significantly associated with diarrheal diseases among under-five children, after controlling for potential confounders.

Thus, the odds of developing diarrheal disease among under-five children were 2.5 and 3 times higher among children of age 6–11 and 12–23 months, respectively, as compared to children of age 24–59 months (AOR 2.46; 95%CI: 1.09–5.57 and AOR 3.3; 95%CI: 1.68–6.46; P 0.05).

When compared to counterparts, the odds of developing diarrheal disease among under-five children from households with no hand-washing facility near their latrine were five times higher (AOR 5.2; 95% CI: 3.94–26.49; P 0.05). Under-five children whose mothers’/caregivers’ had a history of diarrheal disease in the last 2 weeks had 7 times more likely to develop the disease as compared with their counterparts (AOR 7.38; 95%CI: 3.12–17.44; P < 0.05).

The odds of developing diarrheal disease among under-five children was about 2 times higher among households who had not utilized latrines properly when compared to households who had properly utilized them (AOR 2.34; 95%CI: 1.16, 4.75; P < 0.05). The odds of developing diarrheal disease were 10.6 times higher among under-five children whose mothers’/caregivers’ did not wash their hands during critical time compared with under-five children whose mothers’/caregivers’ did wash their hands during critical times (AOR 10.6; 95%CI: 3.7–29.8; P < 0.05).

Odds of developing diarrheal disease among under-five children whose mothers/caregivers practiced improper domestic solid waste disposal were about 2.7 times higher than under-five children whose mothers’/caregivers’ practiced proper domestic solid waste disposal (AOR 2.68; 95%CI: 1.39–5.18; P < 0.05).

Unvaccinated under-five children were 2.5 times more likely to develop diarrhea disease compared to rotavirus vaccinated children, (AOR 2.45; 95%CI: 1.25–4.81 mothers’/caregivers’) (Table 4 ).

Case = under-five children with diarrhea, Control = under-five children without diarrhea, Crude odds’ ratio (COR), adjusted odds’ ratio (AOR), Confidence interval (CI), P -value derived from multivariate logistic regression based on likelihood ratio test, significant CI of the models are indicated in the bold letter, * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.001.

The result of this study showed that children’s age groups 6–11 and 12–23 months were 2.5 and 3 times more likely to develop diarrhoea disease as compared to children in the age group 24–59 months, respectively. This result was consistent with the results of other case-control studies conducted in Medebay Zane District, Gobi District, and Rural Ethiopia [ 20 , 21 , 22 ].

Similarly, this result was consistent with the study reported from Indonesia and Guatemala [ 23 , 24 ]. In general, children older than 24 months had a lower risk of having diarrheal diseases than children whose ages were between 6 and 23 months. The likely explanation for this risk might be that children between the ages of 6–23 months are undergoing complementary feeding, which may make them vulnerable to diarrheal disease-causing infectious agents due to their undeveloped immunity. Moreover, children at these ages are starting to crawl and walk, thus they may pick dirty or other contaminated objects and take them to their mouth. Likewise, the 2016 EDHS report revealed that diarrhoea prevalence remains high (18%) at the age of 12–23 months, for the reason that weaning and walking often occur during these ages, which contribute to the increased risk of contamination from the environment [ 10 ].

The unavailability of a hand-washing facility near the latrine was positively associated with childhood diarrheal disease. In this study, under five-year-old children from households that had no hand-washing facilities adjacent to the latrines were about five times more likely to have diarrheal diseases than under-five-year-old children from households that had hand-washing facilities adjacent to the latrines. The result of this study was consistent with the study conducted in Jimma District and Yama Gulale [ 25 , 26 ]. This might be expressed as where the hand-washing facilities were unavailable near the toilet; the mothers/caregivers may not frequently practice hand-washing after using the toilet and unintentionally feed their children with contaminated hands, which could be contributing to the high prevalence of under-five diarrheal diseases in the district.

Additionally, the findings of this study showed that mothers’/caregivers’ history of diarrheal diseases was significantly associated with diarrhea diseases among under-five children. Children whose mothers/caregivers had diarrheal diseases in the last 2 weeks prior to this study were 7 times more likely to develop diarrheal diseases than children whose mothers/caregivers had no history of diarrheal diseases in the last 2 weeks. The result of this study was similar to the study findings conducted in Ethiopia Harar Town, Medebay Zana District, and Pawi Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia [ 14 , 20 , 27 ]. The fact is that mothers/caregivers are the main food handlers in the family and the main childcare providers; hence, the possibility of diarrheal diseases among children with mothers/caregivers who have had diarrheal diseases is a common event. It also indicates poor hygienic practice in the household results in the occurrence of diarrheal diseases among under-five children. This might be due to mothers/caregivers with diarrheal diseases being considered as a source of infection for diarrheal diseases among under-five children. Moreover, the mother/caregivers might not be providing appropriate and comprehensive care for the child, which could be a contributing factor to the overall burden of under-five diarrhea and its consequences in the study area. The result of this study also revealed that households who improperly utilized latrines were 2 times more likely to develop diarrheal diseases among under-five children compared to households that utilized latrines properly. The result of this study was comparable with the study findings reported from West Gojjam, Ethiopia [ 13 ] and the Kawangware Slum in Nairobi County, Kenya [ 28 ]. This showed that the presence of a latrine alone does not ensure the prevention of diarrheal diseases among under-five children unless properly utilized. Many microorganisms that cause diarrheal diseases may be controlled when latrines are used properly.

This study found that children whose mothers/caregivers did not practice hand-washing during the critical period were 10.6 times more likely to be affected by diarrheal disease than children whose mothers/caregivers did practice hand-washing during the critical times. This finding was in line with the studies conducted in Adama Rural and Harena Buluk woreda in Ethiopia [ 29 , 30 ] and in Zambia [ 31 ]. This might indicate that diarrheal diseases are largely spread through contaminated hands, water and food supplies. This contamination occurs mainly from inadequate hygiene and sanitation. Contaminated hand is the main source of infection thus; mothers/caregivers should wash their hands at a critical time to prevent diarrheal diseases.

The findings of this study revealed that improper domestic solid waste disposal practices were 2.7 times more likely to be at risk of developing diarrhea diseases compared to their counterparts. The results of this study were consistent with the studies conducted in the Medebay Zana District and Jamma District in Ethiopia [ 20 , 26 ] and in Kenya [ 28 ]. This might be due to improper disposal of domestic solid waste, which serves as a source of infectious agents and reproduction sites for insects. As well, improper domestic solid waste disposal practices create a favorable environment for flies that carry pathogens and could be sources of contamination for water, food, and food utensils. These might cause children to be exposed to contaminated environments and are a leading risk factor for diarrheal diseases among under-five children.

The result of our study finding indicated that children who were not received the rotavirus vaccine were 2.5 times more likely to develop diarrheal diseases as compared to those children who were received the rotavirus vaccine. This finding was in line with the studies conducted at Harena Buluk Woreda, Bahir Dar, and Debre Berhan in Ethiopia [ 29 , 32 , 33 ] and in sub-Saharan Africa countries, Cameroon, and Madagascar [ 34 , 35 ]. These findings were reported that the rotavirus vaccine showed a significant association with the occurrence of diarrheal diseases among under-five children. This confirmed that the rotavirus vaccination is one of the best ways to prevent diarrheal morbidity and its consequences, together with improvements of sanitation and hygienic practices. Thus, two-dose rotavirus vaccines should be given for children as part of a comprehensive approach to control diarrhea. Evidence from experts review on vaccines suggests that rotavirus vaccines effectiveness provide sufficient prevention against rotavirus episodes among under-five children thus reducing the morbidity of diarrhea among this age group [ 36 , 37 ].

Strength and limitation of the study

One of the strengths of this study was that it was conducted community-based using a case-control study design and using the WHO/UNICEF core-based standard questionnaire for data collection. Some behavioral practices, including hand-washing practices at a critical time, reports of mother’s/caregiver’s history of the last 2 weeks of diarrhea, and treatment of drinking water at home used in the analysis were self-reported by the mothers/caregivers, which might introduce imprecision and information bias. Not including data on breastfeeding status, HIV sero-status and social factors could be considered as an additional limitation of this study.

The unavailability of a hand-washing facility nearby latrine, mother’s/caregiver’s history of the last 2 weeks’ diarrheal diseases, improper latrine utilization, lack of hand-washing practice at a critical time, improper solid waste disposal practices, and rotavirus vaccination status were the determinants of diarrheal diseases among under-five children identified in this study. Most of the identified determinants of diarrheal disease among under-five children in the study area are preventable. Thus, promoting the provision of continuous and modified health information programs for households on the importance of sanitation (proper domestic solid waste disposal and latrine utilization), personal hygiene (hand-washing facilities and proper hand-washing practices at critical times), and vaccination against rotavirus are fundamental to decreasing the burden of diarrheal disease among under-five children.

Recommendations

The District Health Office and Zonal Health Department should encourage the community to install a hand-washing facility nearby the latrine, motivate the community to utilize the latrine properly and practice hand-washing during a critical time, and strengthen rotavirus vaccination for all under-five children.

Health Extension Workers should facilitate and give health information to mothers/caregivers on the importance of the availability of hand-washing facilities near the latrine, personal hygiene, and proper latrine utilization, hand-washing practices during a critical time, proper solid waste disposal practices, vaccination of rotavirus, and homemade drinking water treatment practices. Local NGOs should collaborate with the District Health Office and other stakeholders on the construction of nearby hand-washing facilities, personal hygiene to prevent the transmission of diarrhea disease from mother to child, the introduction of hand-washing practices at a critical time, and the preparation of areas for proper solid waste disposal practices.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and analyzed throughout the present study accessible from the corresponding author based on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

Adjusted odds ratio

Confidence interval

Crude odds ratio

Ethiopian demographic and health survey

Health officer

Principal investigators

Standard deviation

Sustainable development goal

Statistical package for social science

Sub Saharan Africa

Under five years old children

United Nations Children’s Fund

UNICEF, WHO. Diarrhoea: Why children are still dying and what can be done, Unicef-WHO. New York: UNICEF/WHO 2009. doi, 10, pp.S0140–6736.

Peterson KM, Diedrich E, Lavigne J. Strategies for Combating Waterborne Diarrheal Diseases in the Developing World. 2008.

Chopra M, Binkin NJ, Mason E, Wolfheim C. Integrated management of childhood illness: what have we learned and how can it be improved? Arch Dis Child. 2012;97(4):350–4.

Article Google Scholar

WHO, Diarrhoeal disease. 2017.

Google Scholar

UNICEF, Diarrhoeal disease. 2018.

World Health Organization. Progress on drinking water, sanitation and hygiene: 2017 update and SDG baselines. 2017.

Dairo MD, Ibrahim TF, Salawu AT. Prevalence and determinants of diarrhoea among infants in selected primary health centres in kaduna north local government area, nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2017;28:109 PubMed| Google Scholar.

Azage M, Haile D. Factors associated with safe child feces disposal practices in Ethiopia: evidence from demographic and health survey. Arch Public Health. 2015;73(1):40.

Walker CLF, Rudan I, Liu L, Nair H, Theodoratou E, Bhutta ZA, et al. Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea. Lancet. 2013;381(9875):1405–16.

Csa I. Central statistical agency (CSA)[Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia demographic and health survey, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA. 2016.

Fenta AA. Kassahun Angaw, Dessie Abebaw, prevalence and associated factors of acute diarrhea among under-five children in Kamashi district, western Ethiopia: community-based study. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20(1):236.

Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa, E., and Rockville, Maryland, USA: CSA and ICF; 2016.

Girma M, Gobena T, Medhin G, Gasana J, Roba KT. Determinants of childhood diarrhea in West Gojjam, Northwest Ethiopia: a case control study. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;30:234. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2018.30.234.14109 . PMID: 30574253; PMCID: PMC6295292.

Brhanu H, Negese D, Gebrehiwot M. Determinants of acute diarrheal disease among under-five children in pawi hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Am J Pediatr. 2017;2(2):29–36.

Jimma Geneti district health office first-quarter performance work report. 2019/2020.

Tarekegn M, Enquselassie F. A case control study on determinants of diarrheal morbidity among under-five children in Wolaita Soddo town, southern Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2012;26(2):78–85.

Ayalew AM, Mekonnen WT, Abaya SW, Mekonnen ZA. Assessment of diarrhea and its associated factors in under-five children among open defecation and open defecation-free rural settings of Dangla District, Northwest Ethiopia. J Environ Public Health. 2018;2018.

WHO/UNICEF. Core questions on drinking water and sanitation for household surveys. 2006.

Jimma Geneti agricultural and natural resource office annual work report. report. 2019.

Asfaha KF, Tesfamichael FA, Fisseha GK, Misgina KH, Weldu MG, Welehaweria NB, et al. Determinants of childhood diarrhea in Medebay Zana District, Northwest Tigray, and Ethiopia: a community based unmatched case–control study. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18(1):120.

Megersa S, Benti T, Sahiledengle B. Prevalence of diarrhea and its associated factors among under-five children in open defecation free and non-open defecation free households in Goba District Southeast Ethiopia: a comparative cross-sectional study. Clin Mother Child Health. 2019;16:324.

Ferede MM. Socio-demographic, environmental and behavioural risk factors of diarrhoea among under-five children in rural Ethiopia: further analysis of the 2016 Ethiopian demographic and health survey. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20(1):1–9.

Rohmawati N, Panza A, Lertmaharit S. Factors associated with diarrhea among children under five years of age in Banten Province, Indonesia. J Health Res. 2012;26(1):31–4.

Edward A, Jung Y, Chhorvann C, Ghee AE, Chege J. Association of mother's handwashing practices and pediatric diarrhea: evidence from a multi-country study on community oriented interventions. BMC Public Health. 2019;60(2):E93–e102.

CAS Google Scholar

Degebasa MZ, Weldemichael DZ, Marama MT. Diarrheal status and associated factors in under five years old children in relation to implemented and unimplemented community-led total sanitation and hygiene in Yaya Gulele in 2017. Pediatric Health Med Ther. 2018;9:109.

Workie GY, Akalu TY, Baraki AG. Environmental factors affecting childhood diarrheal disease among under-five children in Jamma district, south Wello zone, Northeast Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):804.

Getachew B, Mengistie B, Mesfin F, Argaw R. Factors associated with acute diarrhea among children aged 0-59 months in Harar town, eastern Ethiopia. East Afr J Health Biomed Sci. 2018;2(1):26–35.

Reuben Mutama DM, Wakibia J. Risk factors associated with diarrhea disease among children under-five years of age in Kawangware slum in Nairobi County, Kenya. Food and Public Health. 2019;9(1):1–6.

Beyene SG, Melku AT. Prevalence of diarrhea and associated factors among under five years children in Harena Buluk Woreda Oromia region, south East Ethiopia, 2018. J Public Health Int. 2018;1(2):9.

Regassa W, Lemma S. Assessment of diarrheal disease prevalence and associated risk factors in children of 6-59 months old at Adama District rural Kebeles, eastern Ethiopia, and January/2015. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2016;26(6):581–8.

Musonda C, Siziya S, Kwangu M, Mulenga D. Factors associated with diarrheal diseases in under-five children: a case control study at arthur davison children’s hospital in Ndola. Zambia Asian Pac J Health Sci. 2017;4(3):228–34.

Shine S, Muhamud S, Adanew S, Demelash A, Abate M. Prevalence and associated factors of diarrhea among under-five children in Debre Berhan town, Ethiopia 2018: a cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):1–6.

Shumetie G, Gedefaw M, Kebede A, Derso T. Exclusive breastfeeding and rotavirus vaccination are associated with decreased diarrheal morbidity among under-five children in Bahir Dar, Northwest Ethiopia. Public Health Rev. 2018;39:28.

Ayuk TB, Carine NE, Ashu NJ, et al. Prevalence of diarrhoea and associated risk factors among children under-five years of age in Efoulan health district- Cameroon, sub-Saharan Africa. MOJ Public Health. 2018;7(6):259–64. https://doi.org/10.15406/mojph.2018.07.00248 .

Randremanana RV, Razafindratsimandresy R, Andriatahina T, Randriamanantena A, Ravelomanana L, Randrianirina F, et al. Etiologies, risk factors and impact of severe diarrhea in the under-fives in Moramanga and Antananarivo, Madagascar. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0158862.

O’Ryan M, Giaquinto C, Benninghoff B. Human rotavirus vaccine (Rotarix): focus on effectiveness and impact 6 years after first introduction in Africa. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2015;14(8):1099–112.

Parashar UD, Tate JE. The control of diarrhea, the case of a rotavirus vaccine. Salud Pública De México. 2020;62(1):1–5.

Download references

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the study participants and all other peoples who had formally or informally involved in the accomplishment of this research.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Public Health, Medicine and Health Sciences College, Ambo University, P.O.BOX:19, Ambo, Oromia, Ethiopia

Dejene Mosisa, Mecha Aboma, Teka Girma & Abera Shibru

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

DM, MA, TG, ASH carried out all the conception and designing of the study, data collection, performed statistical analysis, wrote final report, reviewing and editing the final draft of the manuscript. All of the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mecha Aboma .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethical Review Board of Ambo University College of Medicine and Health Sciences, with the Ref. No of PGC/18/2020. Hierarchically, all administrative bodies were communicated and permission was secured. Written informed consent was obtained from the parent/legal guardian for study subjects after explaining the objectives and procedures of the study and their right to participate or to withdraw at any time of the interview. The Research and Ethical Review Committee also approved its ethical issues as there was no procedure that affects the study subject and the data is used only for research purposes. For this purpose, a one-page consent letter was attached to the cover page of each questionnaire stating the general purpose of the study and issues of confidentiality, which were discussed by data collectors before proceeding to the interview. Parent/legal guardian who was found that their children are sick during the study time; they were consulted about the causes of the disease and refer her/him to a health facility nearby. Lastly, we confirm that this study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Mosisa, D., Aboma, M., Girma, T. et al. Determinants of diarrheal diseases among under five children in Jimma Geneti District, Oromia region, Ethiopia, 2020: a case-control study. BMC Pediatr 21 , 532 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-021-03022-2

Download citation

Received : 22 February 2021

Accepted : 18 November 2021

Published : 30 November 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-021-03022-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Case-control

- Determinants

- Jimma Geneti

BMC Pediatrics

ISSN: 1471-2431

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 09 May 2024

Contextual factors associated with diarrhea among under-five children in the Gambia: a multi-level analysis of population-based data

- Amadou Barrow 1 , 2 ,

- Solomon P.S. Jatta 3 , 4 ,

- Oluwarotimi Samuel Oladele 5 ,

- Osaretin Godspower Okungbowa 6 , 7 &

- Michael Ekholuenetale 8

BMC Infectious Diseases volume 24 , Article number: 453 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Diarrhea poses a significant threat to the lives of children in The Gambia, accounting for approximately 9% of all deaths among children under the age of five. Addressing and reducing child mortality from diarrhea diseases is crucial for achieving the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3, specifically target 3.2, which aims to eliminate preventable deaths in newborns and children under the age of five by 2030. Thus, this research aims to assess the prevalence and contextual factors associated with diarrhea among under-five children in The Gambia.