Literature Reviews: Types of Clinical Study Designs

- Library Basics

- 1. Choose Your Topic

- How to Find Books

- Types of Clinical Study Designs

- Types of Literature

- 3. Search the Literature

- 4. Read & Analyze the Literature

- 5. Write the Review

- Keeping Track of Information

- Style Guides

- Books, Tutorials & Examples

Types of Study Designs

Meta-Analysis A way of combining data from many different research studies. A meta-analysis is a statistical process that combines the findings from individual studies. Example : Anxiety outcomes after physical activity interventions: meta-analysis findings . Conn V. Nurs Res . 2010 May-Jun;59(3):224-31.

Systematic Review A summary of the clinical literature. A systematic review is a critical assessment and evaluation of all research studies that address a particular clinical issue. The researchers use an organized method of locating, assembling, and evaluating a body of literature on a particular topic using a set of specific criteria. A systematic review typically includes a description of the findings of the collection of research studies. The systematic review may also include a quantitative pooling of data, called a meta-analysis. Example : Complementary and alternative medicine use among women with breast cancer: a systematic review. Wanchai A, Armer JM, Stewart BR. Clin J Oncol Nurs . 2010 Aug;14(4):E45-55.

Randomized Controlled Trial A controlled clinical trial that randomly (by chance) assigns participants to two or more groups. There are various methods to randomize study participants to their groups. Example : Meditation or exercise for preventing acute respiratory infection: a randomized controlled trial . Barrett B, et al. Ann Fam Med . 2012 Jul-Aug;10(4):337-46.

Cohort Study (Prospective Observational Study) A clinical research study in which people who presently have a certain condition or receive a particular treatment are followed over time and compared with another group of people who are not affected by the condition. Example : Smokeless tobacco cessation in South Asian communities: a multi-centre prospective cohort study . Croucher R, et al. Addiction. 2012 Dec;107 Suppl 2:45-52.

Case-control Study Case-control studies begin with the outcomes and do not follow people over time. Researchers choose people with a particular result (the cases) and interview the groups or check their records to ascertain what different experiences they had. They compare the odds of having an experience with the outcome to the odds of having an experience without the outcome. Example : Non-use of bicycle helmets and risk of fatal head injury: a proportional mortality, case-control study . Persaud N, et al. CMAJ . 2012 Nov 20;184(17):E921-3.

Cross-sectional study The observation of a defined population at a single point in time or time interval. Exposure and outcome are determined simultaneously. Example : Fasting might not be necessary before lipid screening: a nationally representative cross-sectional study . Steiner MJ, et al. Pediatrics . 2011 Sep;128(3):463-70.

Case Reports and Series A report on a series of patients with an outcome of interest. No control group is involved. Example : Students mentoring students in a service-learning clinical supervision experience: an educational case report . Lattanzi JB, et al. Phys Ther . 2011 Oct;91(10):1513-24.

Ideas, Editorials, Opinions Put forth by experts in the field. Example : Health and health care for the 21st century: for all the people . Koop CE. Am J Public Health . 2006 Dec;96(12):2090-2.

Animal Research Studies Studies conducted using animal subjects. Example : Intranasal leptin reduces appetite and induces weight loss in rats with diet-induced obesity (DIO) . Schulz C, Paulus K, Jöhren O, Lehnert H. Endocrinology . 2012 Jan;153(1):143-53.

Test-tube Lab Research "Test tube" experiments conducted in a controlled laboratory setting.

Adapted from Study Designs. In NICHSR Introduction to Health Services Research: a Self-Study Course. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/nichsr/ihcm/06studies/studies03.html and Glossary of EBM Terms. http://www.cebm.utoronto.ca/glossary/index.htm#top

Study Design Terminology

Bias - Any deviation of results or inferences from the truth, or processes leading to such deviation. Bias can result from several sources: one-sided or systematic variations in measurement from the true value (systematic error); flaws in study design; deviation of inferences, interpretations, or analyses based on flawed data or data collection; etc. There is no sense of prejudice or subjectivity implied in the assessment of bias under these conditions.

Case Control Studies - Studies which start with the identification of persons with a disease of interest and a control (comparison, referent) group without the disease. The relationship of an attribute to the disease is examined by comparing diseased and non-diseased persons with regard to the frequency or levels of the attribute in each group.

Causality - The relating of causes to the effects they produce. Causes are termed necessary when they must always precede an effect and sufficient when they initiate or produce an effect. Any of several factors may be associated with the potential disease causation or outcome, including predisposing factors, enabling factors, precipitating factors, reinforcing factors, and risk factors.

Control Groups - Groups that serve as a standard for comparison in experimental studies. They are similar in relevant characteristics to the experimental group but do not receive the experimental intervention.

Controlled Clinical Trials - Clinical trials involving one or more test treatments, at least one control treatment, specified outcome measures for evaluating the studied intervention, and a bias-free method for assigning patients to the test treatment. The treatment may be drugs, devices, or procedures studied for diagnostic, therapeutic, or prophylactic effectiveness. Control measures include placebos, active medicines, no-treatment, dosage forms and regimens, historical comparisons, etc. When randomization using mathematical techniques, such as the use of a random numbers table, is employed to assign patients to test or control treatments, the trials are characterized as Randomized Controlled Trials.

Cost-Benefit Analysis - A method of comparing the cost of a program with its expected benefits in dollars (or other currency). The benefit-to-cost ratio is a measure of total return expected per unit of money spent. This analysis generally excludes consideration of factors that are not measured ultimately in economic terms. Cost effectiveness compares alternative ways to achieve a specific set of results.

Cross-Over Studies - Studies comparing two or more treatments or interventions in which the subjects or patients, upon completion of the course of one treatment, are switched to another. In the case of two treatments, A and B, half the subjects are randomly allocated to receive these in the order A, B and half to receive them in the order B, A. A criticism of this design is that effects of the first treatment may carry over into the period when the second is given.

Cross-Sectional Studies - Studies in which the presence or absence of disease or other health-related variables are determined in each member of the study population or in a representative sample at one particular time. This contrasts with LONGITUDINAL STUDIES which are followed over a period of time.

Double-Blind Method - A method of studying a drug or procedure in which both the subjects and investigators are kept unaware of who is actually getting which specific treatment.

Empirical Research - The study, based on direct observation, use of statistical records, interviews, or experimental methods, of actual practices or the actual impact of practices or policies.

Evaluation Studies - Works consisting of studies determining the effectiveness or utility of processes, personnel, and equipment.

Genome-Wide Association Study - An analysis comparing the allele frequencies of all available (or a whole genome representative set of) polymorphic markers in unrelated patients with a specific symptom or disease condition, and those of healthy controls to identify markers associated with a specific disease or condition.

Intention to Treat Analysis - Strategy for the analysis of Randomized Controlled Trial that compares patients in the groups to which they were originally randomly assigned.

Logistic Models - Statistical models which describe the relationship between a qualitative dependent variable (that is, one which can take only certain discrete values, such as the presence or absence of a disease) and an independent variable. A common application is in epidemiology for estimating an individual's risk (probability of a disease) as a function of a given risk factor.

Longitudinal Studies - Studies in which variables relating to an individual or group of individuals are assessed over a period of time.

Lost to Follow-Up - Study subjects in cohort studies whose outcomes are unknown e.g., because they could not or did not wish to attend follow-up visits.

Matched-Pair Analysis - A type of analysis in which subjects in a study group and a comparison group are made comparable with respect to extraneous factors by individually pairing study subjects with the comparison group subjects (e.g., age-matched controls).

Meta-Analysis - Works consisting of studies using a quantitative method of combining the results of independent studies (usually drawn from the published literature) and synthesizing summaries and conclusions which may be used to evaluate therapeutic effectiveness, plan new studies, etc. It is often an overview of clinical trials. It is usually called a meta-analysis by the author or sponsoring body and should be differentiated from reviews of literature.

Numbers Needed To Treat - Number of patients who need to be treated in order to prevent one additional bad outcome. It is the inverse of Absolute Risk Reduction.

Odds Ratio - The ratio of two odds. The exposure-odds ratio for case control data is the ratio of the odds in favor of exposure among cases to the odds in favor of exposure among noncases. The disease-odds ratio for a cohort or cross section is the ratio of the odds in favor of disease among the exposed to the odds in favor of disease among the unexposed. The prevalence-odds ratio refers to an odds ratio derived cross-sectionally from studies of prevalent cases.

Patient Selection - Criteria and standards used for the determination of the appropriateness of the inclusion of patients with specific conditions in proposed treatment plans and the criteria used for the inclusion of subjects in various clinical trials and other research protocols.

Predictive Value of Tests - In screening and diagnostic tests, the probability that a person with a positive test is a true positive (i.e., has the disease), is referred to as the predictive value of a positive test; whereas, the predictive value of a negative test is the probability that the person with a negative test does not have the disease. Predictive value is related to the sensitivity and specificity of the test.

Prospective Studies - Observation of a population for a sufficient number of persons over a sufficient number of years to generate incidence or mortality rates subsequent to the selection of the study group.

Qualitative Studies - Research that derives data from observation, interviews, or verbal interactions and focuses on the meanings and interpretations of the participants.

Quantitative Studies - Quantitative research is research that uses numerical analysis.

Random Allocation - A process involving chance used in therapeutic trials or other research endeavor for allocating experimental subjects, human or animal, between treatment and control groups, or among treatment groups. It may also apply to experiments on inanimate objects.

Randomized Controlled Trial - Clinical trials that involve at least one test treatment and one control treatment, concurrent enrollment and follow-up of the test- and control-treated groups, and in which the treatments to be administered are selected by a random process, such as the use of a random-numbers table.

Reproducibility of Results - The statistical reproducibility of measurements (often in a clinical context), including the testing of instrumentation or techniques to obtain reproducible results. The concept includes reproducibility of physiological measurements, which may be used to develop rules to assess probability or prognosis, or response to a stimulus; reproducibility of occurrence of a condition; and reproducibility of experimental results.

Retrospective Studies - Studies used to test etiologic hypotheses in which inferences about an exposure to putative causal factors are derived from data relating to characteristics of persons under study or to events or experiences in their past. The essential feature is that some of the persons under study have the disease or outcome of interest and their characteristics are compared with those of unaffected persons.

Sample Size - The number of units (persons, animals, patients, specified circumstances, etc.) in a population to be studied. The sample size should be big enough to have a high likelihood of detecting a true difference between two groups.

Sensitivity and Specificity - Binary classification measures to assess test results. Sensitivity or recall rate is the proportion of true positives. Specificity is the probability of correctly determining the absence of a condition.

Single-Blind Method - A method in which either the observer(s) or the subject(s) is kept ignorant of the group to which the subjects are assigned.

Time Factors - Elements of limited time intervals, contributing to particular results or situations.

Source: NLM MeSH Database

- << Previous: How to Find Books

- Next: Types of Literature >>

- Last Updated: Dec 29, 2023 11:41 AM

- URL: https://research.library.gsu.edu/litrev

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous

- Next chapter >

1Chapter 1 The literature review

- Published: November 2011

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

A major part of any study, the literature review has a variety of influences over a project which may not be immediately apparent to those new to the research field. In essence, pulling a number of citations out of a search engine to request from the library is only one small element of this important tool in addressing the research question. Before discussing the practicalities of the literature review we need to establish what it is, why it is necessary to do one in the first place, and how such a review fits into both the research process and the finished dissertation. Before being able to establish a research question or decide on a design to address a clinical problem, it is necessary to have an awareness of published material pertaining to that subject. In broad terms, what do we already know? Through an appraisal of the literature, one can identify if further investigation is merited, avoid duplication, and benefit from the experiences of those exploring similar issues.… It is generally unwise to define something as important as a dissertation topic without first obtaining a broad familiarity with the field. (Rudestam and Newton, 1992, p.9) (1)… A comprehensive review of the literature will ensure you have a grasp of up-to-date knowledge, which is key to putting any research project into context. Whilst in-depth critical appraisal of the relevant literature may not be necessary at this point, one can see that a literature review is required to turn an interesting idea into a research question. Having established its role in the conception of a research question, once the project is underway the review serves a variety of purposes. No research is unique in all its aspects—at least some of the features addressed in the project will have been previously described and may be used to justify why further investigation is required. To this end each individual research project forms one part of a bigger ‘evidence-based jigsaw puzzle’. Without an appreciation of all the other bits of the puzzle it is impossible to provide a background and identify a gap in the knowledge base which we wish to address.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Health (Nursing, Medicine, Allied Health)

- Find Articles/Databases

- Reference Resources

- Evidence Summaries & Clinical Guidelines

- Drug Information

- Health Data & Statistics

- Patient/Consumer Facing Materials

- Images and Streaming Video

- Grey Literature

- Mobile Apps & "Point of Care" Tools

- Tests & Measures This link opens in a new window

- Citing Sources

- Selecting Databases

- Framing Research Questions

- Crafting a Search

- Narrowing / Filtering a Search

- Expanding a Search

- Cited Reference Searching

- Saving Searches

- Term Glossary

- Critical Appraisal Resources

- What are Literature Reviews?

- Conducting & Reporting Systematic Reviews

- Finding Systematic Reviews

- Tutorials & Tools for Literature Reviews

- Finding Full Text

What are Systematic Reviews? (3 minutes, 24 second YouTube Video)

Systematic Literature Reviews: Steps & Resources

These steps for conducting a systematic literature review are listed below .

Also see subpages for more information about:

- The different types of literature reviews, including systematic reviews and other evidence synthesis methods

- Tools & Tutorials

Literature Review & Systematic Review Steps

- Develop a Focused Question

- Scope the Literature (Initial Search)

- Refine & Expand the Search

- Limit the Results

- Download Citations

- Abstract & Analyze

- Create Flow Diagram

- Synthesize & Report Results

1. Develop a Focused Question

Consider the PICO Format: Population/Problem, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome

Focus on defining the Population or Problem and Intervention (don't narrow by Comparison or Outcome just yet!)

"What are the effects of the Pilates method for patients with low back pain?"

Tools & Additional Resources:

- PICO Question Help

- Stillwell, Susan B., DNP, RN, CNE; Fineout-Overholt, Ellen, PhD, RN, FNAP, FAAN; Melnyk, Bernadette Mazurek, PhD, RN, CPNP/PMHNP, FNAP, FAAN; Williamson, Kathleen M., PhD, RN Evidence-Based Practice, Step by Step: Asking the Clinical Question, AJN The American Journal of Nursing : March 2010 - Volume 110 - Issue 3 - p 58-61 doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000368959.11129.79

2. Scope the Literature

A "scoping search" investigates the breadth and/or depth of the initial question or may identify a gap in the literature.

Eligible studies may be located by searching in:

- Background sources (books, point-of-care tools)

- Article databases

- Trial registries

- Grey literature

- Cited references

- Reference lists

When searching, if possible, translate terms to controlled vocabulary of the database. Use text word searching when necessary.

Use Boolean operators to connect search terms:

- Combine separate concepts with AND (resulting in a narrower search)

- Connecting synonyms with OR (resulting in an expanded search)

Search: pilates AND ("low back pain" OR backache )

Video Tutorials - Translating PICO Questions into Search Queries

- Translate Your PICO Into a Search in PubMed (YouTube, Carrie Price, 5:11)

- Translate Your PICO Into a Search in CINAHL (YouTube, Carrie Price, 4:56)

3. Refine & Expand Your Search

Expand your search strategy with synonymous search terms harvested from:

- database thesauri

- reference lists

- relevant studies

Example:

(pilates OR exercise movement techniques) AND ("low back pain" OR backache* OR sciatica OR lumbago OR spondylosis)

As you develop a final, reproducible strategy for each database, save your strategies in a:

- a personal database account (e.g., MyNCBI for PubMed)

- Log in with your NYU credentials

- Open and "Make a Copy" to create your own tracker for your literature search strategies

4. Limit Your Results

Use database filters to limit your results based on your defined inclusion/exclusion criteria. In addition to relying on the databases' categorical filters, you may also need to manually screen results.

- Limit to Article type, e.g.,: "randomized controlled trial" OR multicenter study

- Limit by publication years, age groups, language, etc.

NOTE: Many databases allow you to filter to "Full Text Only". This filter is not recommended . It excludes articles if their full text is not available in that particular database (CINAHL, PubMed, etc), but if the article is relevant, it is important that you are able to read its title and abstract, regardless of 'full text' status. The full text is likely to be accessible through another source (a different database, or Interlibrary Loan).

- Filters in PubMed

- CINAHL Advanced Searching Tutorial

5. Download Citations

Selected citations and/or entire sets of search results can be downloaded from the database into a citation management tool. If you are conducting a systematic review that will require reporting according to PRISMA standards, a citation manager can help you keep track of the number of articles that came from each database, as well as the number of duplicate records.

In Zotero, you can create a Collection for the combined results set, and sub-collections for the results from each database you search. You can then use Zotero's 'Duplicate Items" function to find and merge duplicate records.

- Citation Managers - General Guide

6. Abstract and Analyze

- Migrate citations to data collection/extraction tool

- Screen Title/Abstracts for inclusion/exclusion

- Screen and appraise full text for relevance, methods,

- Resolve disagreements by consensus

Covidence is a web-based tool that enables you to work with a team to screen titles/abstracts and full text for inclusion in your review, as well as extract data from the included studies.

- Covidence Support

- Critical Appraisal Tools

- Data Extraction Tools

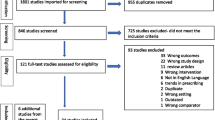

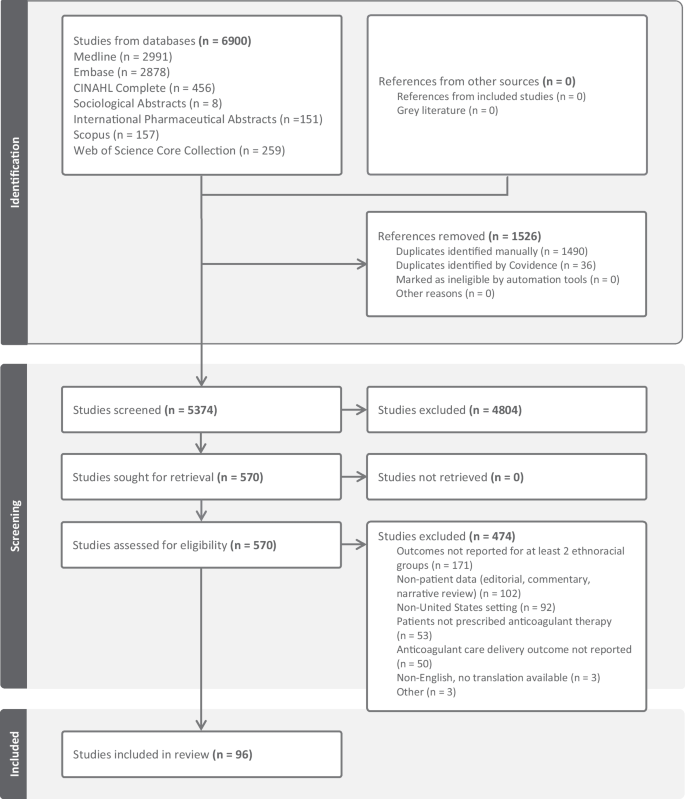

7. Create Flow Diagram

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram is a visual representation of the flow of records through different phases of a systematic review. It depicts the number of records identified, included and excluded. It is best used in conjunction with the PRISMA checklist .

Example from: Stotz, S. A., McNealy, K., Begay, R. L., DeSanto, K., Manson, S. M., & Moore, K. R. (2021). Multi-level diabetes prevention and treatment interventions for Native people in the USA and Canada: A scoping review. Current Diabetes Reports, 2 (11), 46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-021-01414-3

- PRISMA Flow Diagram Generator (ShinyApp.io, Haddaway et al. )

- PRISMA Diagram Templates (Word and PDF)

- Make a copy of the file to fill out the template

- Image can be downloaded as PDF, PNG, JPG, or SVG

- Covidence generates a PRISMA diagram that is automatically updated as records move through the review phases

8. Synthesize & Report Results

There are a number of reporting guideline available to guide the synthesis and reporting of results in systematic literature reviews.

It is common to organize findings in a matrix, also known as a Table of Evidence (ToE).

- Reporting Guidelines for Systematic Reviews

- Download a sample template of a health sciences review matrix (GoogleSheets)

Steps modified from:

Cook, D. A., & West, C. P. (2012). Conducting systematic reviews in medical education: a stepwise approach. Medical Education , 46 (10), 943–952.

- << Previous: Critical Appraisal Resources

- Next: What are Literature Reviews? >>

- Last Updated: May 16, 2024 9:53 AM

- URL: https://guides.nyu.edu/health

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Performing a...

Performing a literature review

- Related content

- Peer review

- Gulraj S Matharu , academic foundation doctor ,

- Christopher D Buckley , Arthritis Research UK professor of rheumatology

- 1 Institute of Biomedical Research, College of Medical and Dental Sciences, School of Immunity and Infection, University of Birmingham, UK

A necessary skill for any doctor

What causes disease, which drug is best, does this patient need surgery, and what is the prognosis? Although experience helps in answering these questions, ultimately they are best answered by evidence based medicine. But how do you assess the evidence? As a medical student, and throughout your career as a doctor, critical appraisal of published literature is an important skill to develop and refine. At medical school you will repeatedly appraise published literature and write literature reviews. These activities are commonly part of a special study module, research project for an intercalated degree, or another type of essay based assignment.

Formulating a question

Literature reviews are most commonly performed to help answer a particular question. While you are at medical school, there will usually be some choice regarding the area you are going to review.

Once you have identified a subject area for review, the next step is to formulate a specific research question. This is arguably the most important step because a clear question needs to be defined from the outset, which you aim to answer by doing the review. The clearer the question, the more likely it is that the answer will be clear too. It is important to have discussions with your supervisor when formulating a research question as his or her input will be invaluable. The research question must be objective and concise because it is easier to search through the evidence with a clear question. The question also needs to be feasible. What is the point in having a question for which no published evidence exists? Your supervisor’s input will ensure you are not trying to answer an unrealistic question. Finally, is the research question clinically important? There are many research questions that may be answered, but not all of them will be relevant to clinical practice. The research question we will use as an example to work through in this article is, “What is the evidence for using angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors in patients with hypertension?”

Collecting the evidence

After formulating a specific research question for your literature review, the next step is to collect the evidence. Your supervisor will initially point you in the right direction by highlighting some of the more relevant papers published. Before doing the literature search it is important to agree a list of keywords with your supervisor. A source of useful keywords can be obtained by reading Cochrane reviews or other systematic reviews, such as those published in the BMJ . 1 2 A relevant Cochrane review for our research question on ACE inhibitors in hypertension is that by Heran and colleagues. 3 Appropriate keywords to search for the evidence include the words used in your research question (“angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor,” “hypertension,” “blood pressure”), details of the types of study you are looking for (“randomised controlled trial,” “case control,” “cohort”), and the specific drugs you are interested in (that is, the various ACE inhibitors such as “ramipril,” “perindopril,” and “lisinopril”).

Once keywords have been agreed it is time to search for the evidence using the various electronic medical databases (such as PubMed, Medline, and EMBASE). PubMed is the largest of these databases and contains online information and tutorials on how to do literature searches with worked examples. Searching the databases and obtaining the articles are usually free of charge through the subscription that your university pays. Early consultation with a medical librarian is important as it will help you perform your literature search in an impartial manner, and librarians can train you to do these searches for yourself.

Literature searches can be broad or tailored to be more specific. With our example, a broad search would entail searching all articles that contain the words “blood pressure” or “ACE inhibitor.” This provides a comprehensive list of all the literature, but there are likely to be thousands of articles to review subsequently (fig 1). ⇓ In contrast, various search restrictions can be applied on the electronic databases to filter out papers that may not be relevant to your review. Figure 2 gives an example of a specific search. ⇓ The search terms used in this case were “angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor” and “hypertension.” The limits applied to this search were all randomised controlled trials carried out in humans, published in the English language over the last 10 years, with the search terms appearing in the title of the study only. Thus the more specific the search strategy, the more manageable the number of articles to review (fig 3), and this will save you time. ⇓ However, this method risks your not identifying all the evidence in the particular field. Striking a balance between a broad and a specific search strategy is therefore important. This will come with experience and consultation with your supervisor. It is important to note that evidence is continually becoming available on these electronic databases and therefore repeating the same search at a later date can provide new evidence relevant to your review.

Fig 1 Results from a broad literature search using the term “angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor”

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Fig 2 Example of a specific literature search. The search terms used were “angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor” and “hypertension.” The limits applied to this search were all randomised controlled trials carried out in humans, published in English over the past 10 years, with the search terms appearing in the title of the study only

Fig 3 Results from a specific literature search (using the search terms and limits from figure 2)

Reading the abstracts (study summary) of the articles identified in your search may help you decide whether the study is applicable for your review—for example, the work may have been carried out using an animal model rather than in humans. After excluding any inappropriate articles, you need to obtain the full articles of studies you have identified. Additional relevant articles that may not have come up in your original search can also be found by searching the reference lists of the articles you have already obtained. Once again, you may find that some articles are still not applicable for your review, and these can also be excluded at this stage. It is important to explain in your final review what criteria you used to exclude articles as well as those criteria used for inclusion.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) publishes evidence based guidelines for the United Kingdom and therefore provides an additional resource for identifying the relevant literature in a particular field. 4 NICE critically appraises the published literature with recommendations for best clinical practice proposed and graded based on the quality of evidence available. Similarly, there are internationally published evidence based guidelines, such as those produced by the European Society of Cardiology and the American College of Chest Physicians, which can be useful when collecting the literature in a particular field. 5 6

Appraising the evidence

Once you have collected the evidence, you need to critically appraise the published material. Box 1 gives definitions of terms you will encounter when reading the literature. A brief guide of how to critically appraise a study is presented; however, it is advisable to consult the references cited for further details.

Box 1: Definitions of common terms in the literature 7

Prospective—collecting data in real time after the study is designed

Retrospective—analysis of data that have already been collected to determine associations between exposure and outcome

Hypothesis—proposed association between exposure and outcome. If presented in the negative it is called the null hypothesis

Variable—a quantity or quality that changes during the study and can be measured

Single blind—subjects are unaware of their treatment, but clinicians are aware

Double blind—both subjects and clinicians are unaware of treatment given

Placebo—a simulated medical intervention, with subjects not receiving the specific intervention or treatment being studied

Outcome measure/endpoint—clinical variable or variables measured in a study subsequently used to make conclusions about the original interventions or treatments administered

Bias—difference between reported results and true results. Many types exist (such as selection, allocation, and reporting biases)

Probability (P) value—number between 0 and 1 providing the likelihood the reported results occurred by chance. A P value of 0.05 means there is a 5% likelihood that the reported result occurred by chance

Confidence intervals—provides a range between two numbers within which one can be certain the results lie. A confidence interval of 95% means one can be 95% certain the actual results lie within the reported range

The study authors should clearly define their research question and ideally the hypothesis to be tested. If the hypothesis is presented in the negative, it is called the null hypothesis. An example of a null hypothesis is smoking does not cause lung cancer. The study is then performed to assess the significance of the exposure (smoking) on outcome (lung cancer).

A major part of the critical appraisal process is to focus on study methodology, with your key task being an assessment of the extent to which a study was susceptible to bias (the discrepancy between the reported results and the true results). It should be clear from the methods what type of study was performed (box 2).

Box 2: Different study types 7

Systematic review/meta-analysis—comprehensive review of published literature using predefined methodology. Meta-analyses combine results from various studies to give numerical data for the overall association between variables

Randomised controlled trial—random allocation of patients to one of two or more groups. Used to test a new drug or procedure

Cohort study—two or more groups followed up over a long period, with one group exposed to a certain agent (drug or environmental agent) and the other not exposed, with various outcomes compared. An example would be following up a group of smokers and a group of non-smokers with the outcome measure being the development of lung cancer

Case-control study—cases (those with a particular outcome) are matched as closely as possible (for age, sex, ethnicity) with controls (those without the particular outcome). Retrospective data analysis is performed to determine any factors associated with developing the particular outcomes

Cross sectional study—looks at a specific group of patients at a single point in time. Effectively a survey. An example is asking a group of people how many of them drink alcohol

Case report—detailed reports concerning single patients. Useful in highlighting adverse drug reactions

There are many different types of bias, which depend on the particular type of study performed, and it is important to look for these biases. Several published checklists are available that provide excellent resources to help you work through the various studies and identify sources of bias. The CONSORT statement (which stands for CONsolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials) provides a minimum set of recommendations for reporting randomised controlled trials and comprises a rigorous 25 item checklist, with variations available for other study types. 8 9 As would be expected, most (17 of 25) of the items focus on questions relating to the methods and results of the randomised trial. The remaining items relate to the title, abstract, introduction, and discussion of the study, in addition to questions on trial registration, protocol, and funding.

Jadad scoring provides a simple and validated system to assess the methodological quality of a randomised clinical trial using three questions. 10 The score ranges from zero to five, with one point given for a “yes” in each of the following questions. (1) Was the study described as randomised? (2) Was the study described as double blind? (3) Were there details of subject withdrawals, exclusions, and dropouts? A further point is given if (1) the method of randomisation was appropriate, and (2) the method of blinding was appropriate.

In addition, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme provides excellent tools for assessing the evidence in all study types (box 2). 11 The Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine levels of evidence is yet another useful resource for assessing the methodological quality of all studies. 12

Ensure all patients have been accounted for and any exclusions, for whatever reason, are reported. Knowing the baseline demographic (age, sex, ethnicity) and clinical characteristics of the population is important. Results are usually reported as probability values or confidence intervals (box 1).

This should explain the major study findings, put the results in the context of the published literature, and attempt to account for any variations from previous work. Study limitations and sources of bias should be discussed. Authors’ conclusions should be supported by the study results and not unnecessarily extrapolated. For example, a treatment shown to be effective in animals does not necessarily mean it will work in humans.

The format for writing up the literature review usually consists of an abstract (short structured summary of the review), the introduction or background, methods, results, and discussion with conclusions. There are a number of good examples of how to structure a literature review and these can be used as an outline when writing your review. 13 14

The introduction should identify the specific research question you intend to address and briefly put this into the context of the published literature. As you have now probably realised, the methods used for the review must be clear to the reader and provide the necessary detail for someone to be able to reproduce the search. The search strategy needs to include a list of keywords used, which databases were searched, and the specific search limits or filters applied. Any grading of methodological quality, such as the CONSORT statement or Jadad scoring, must be explained in addition to any study inclusion or exclusion criteria. 6 7 8 The methods also need to include a section on the data collected from each of the studies, the specific outcomes of interest, and any statistical analysis used. The latter point is usually relevant only when performing meta-analyses.

The results section must clearly show the process of filtering down from the articles obtained from the original search to the final studies included in the review—that is, accounting for all excluded studies. A flowchart is usually best to illustrate this. Next should follow a brief description of what was done in the main studies, the number of participants, the relevant results, and any potential sources of bias. It is useful to group similar studies together as it allows comparisons to be made by the reader and saves repetition in your write-up. Boxes and figures should be used appropriately to illustrate important findings from the various studies.

Finally, in the discussion you need to consider the study findings in light of the methodological quality—that is, the extent of potential bias in each study that may have affected the study results. Using the evidence, you need to make conclusions in your review, and highlight any important gaps in the evidence base, which need to be dealt with in future studies. Working through drafts of the literature review with your supervisor will help refine your critical appraisal skills and the ability to present information concisely in a structured review article. Remember, if the work is good it may get published.

Originally published as: Student BMJ 2012;20:e404

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

- ↵ The Cochrane Library. www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgibin/mrwhome/106568753/HOME?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0 .

- ↵ British Medical Journal . www.bmj.com/ .

- ↵ Heran BS, Wong MMY, Heran IK, Wright JM. Blood pressure lowering efficacy of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors for primary hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008 ; 4 : CD003823 , doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003823.pub2. OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. www.nice.org.uk .

- ↵ European Society of Cardiology. www.escardio.org/guidelines .

- ↵ Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, Heit JA, Samama CM, Lassen MR, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8th ed). Chest 2008 ; 133 : 381 -453S. OpenUrl CrossRef

- ↵ Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki .

- ↵ Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG, Egger M, Davidoff F, Elbourne D, et al. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Lancet 2001 ; 357 : 1191 -4. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ The CONSORT statement. www.consort-statement.org/ .

- ↵ Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996 ; 17 : 1 -12. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). www.sph.nhs.uk/what-we-do/public-health-workforce/resources/critical-appraisals-skills-programme .

- ↵ Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine—Levels of Evidence. www.cebm.net .

- ↵ Van den Bruel A, Thompson MJ, Haj-Hassan T, Stevens R, Moll H, Lakhanpaul M, et al . Diagnostic value of laboratory tests in identifying serious infections in febrile children: systematic review. BMJ 2011 ; 342 : d3082 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Awopetu AI, Moxey P, Hinchliffe RJ, Jones KG, Thompson MM, Holt PJ. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the relationship between hospital volume and outcome for lower limb arterial surgery. Br J Surg 2010 ; 97 : 797 -803. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

The “PP-ICONS” approach will help you separate the clinical wheat from the chaff in mere minutes .

ROBERT J. FLAHERTY, MD

Fam Pract Manag. 2004;11(5):47-52

Keeping up with the latest advances in diagnosis and treatment is a challenge we all face as phycians. We need information that is both valid (that is, accurate and correct) and relevant to our patients and practices. While we have many sources of clinical information, such as CME lectures, textbooks, pharmaceutical advertising, pharmaceutical representatives and colleagues, we often turn to journal articles for the most current clinical information.

Unfortunately, a great deal of research reported in journal articles is poorly done, poorly analyzed or both, and thus is not valid. A great deal of research is also irrelevant to our patients and practices. Separating the clinical wheat from the chaff can take skills that many of us never were taught.

Reading the abstract is often sufficient when evaluating an article using the PP-ICONS approach.

The most relevant studies will involve outcomes that matter to patients (e.g., morbidity, mortality and cost) versus outcomes that matter to physiologists (e.g., blood pressure, blood sugar or cholesterol levels).

Ignore the relative risk reduction, as it overstates research findings and will mislead you.

The article “Making Evidence-Based Medicine Doable in Everyday Practice” in the February 2004 issue of FPM describes several organizations that can help us. These organizations, such as the Cochrane Library, Bandolier and Clinical Evidence, develop clinical questions and then review one or more journal articles to identify the best available evidence that answers the question, with a focus on the quality of the study, the validity of the results and the relevance of the findings to everyday practice. These organizations provide a very valuable service, and the number of important clinical questions that they have studied has grown steadily over the past five years. (See “Four steps to an evidence-based answer.” )

FOUR STEPS TO AN EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER

When faced with a clinical question, follow these steps to find an evidence-based answer:

Search the Web site of one of the evidence review organizations, such as Cochrane (http://www.cochrane.org/cochrane/revabstr/mainindex.htm), Bandolier ( http://www.jr2.ox.ac.uk/bandolier ) or Clinical Evidence ( http://www.clinicalevidence.com ), described in “Making Evidence-Based Medicine Doable in Everyday Practice,” FPM, February 2004, page 51 . You can also search the TRIP+ Web site ( http://www.tripdatabase.com ), which simultaneously searches the databases of many of the review organizations. If you find a systematic review or meta-analysis by one of these organizations, you can be confident that you’ve found the best evidence available.

If you don’t find the information you need through step 1, search for meta-analyses and systematic reviews using the PubMed Web site (see the tutorial at http://www.nlm.nih.gov/bsd/pubmed_tutorial/m1001.html ). Most of the recent abstracts found on PubMed provide enough information for you to determine the validity and relevance of the findings. If needed, you can get a copy of the full article through your hospital library or the journal’s Web site.

If you cannot find a systematic review or meta-analysis on PubMed, look for a randomized controlled trial (RCT). The RCT is the “gold standard” in medical research. Case reports, cohort studies and other research methods simply are not good enough to use for making patient care decisions.

Once you find the article you need, use the PP-ICONS approach to evaluate its usefulness to your patient.

If you find a systematic review or meta-analysis done by one of these organizations, you can feel confident that you have found the current best evidence. However, these organizations have not asked all of the common clinical questions yet, and you will frequently be faced with finding the pertinent articles and determining for yourself whether they are valuable. This is where the PP-ICONS approach can help.

What is PP-ICONS?

When you find a systematic review, meta-analysis or randomized controlled trial while reading your clinical journals or searching PubMed ( http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi ), you need to determine whether it is valid and relevant. There are many different ways to analyze an abstract or journal article, some more rigorous than others. 1 , 2 I have found a simple but effective way to identify a valid or relevant article within a couple of minutes, ensuring that I can use or discard the conclusions with confidence. This approach works well on articles regarding treatment and prevention, and can also be used with articles on diagnosis and screening.

The most important information to look for when reviewing an article can be summarized by the acronym “PP-ICONS,” which stands for the following:

Patient or population,

Intervention,

Comparison,

Number of subjects,

Statistics.

For example, imagine that you just saw a nine-year-old patient in the office with common warts on her hands, an ideal candidate for your usual cryotherapy. Her mother had heard about treating warts with duct tape and wondered if you would recommend this treatment. You promised to call Mom back after you had a chance to investigate this rather odd treatment.

When you get a free moment, you write down your clinical question: “Is duct tape an effective treatment for warts in children?” Writing down your clinical question is useful, as it can help you clarify exactly what you are looking for. Use the PPICO parts of the acronym to help you write your clinical question; this is actually how many researchers develop their research questions.

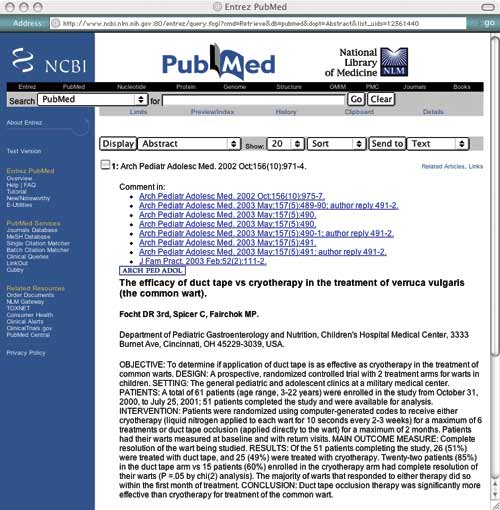

You search Cochrane and Bandolier without success, so now you search PubMed, which returns an abstract for the following article: “Focht DR 3rd, Spicer C, Fairchok MP. The efficacy of duct tape vs cryotherapy in the treatment of verruca vulgaris (the common wart). Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med . 2002 Oct;156(10):971-974.”

You decide to apply PP-ICONS to this abstract (see "Abstract from PubMed" ) to determine if the information is both valid and relevant.

ABSTRACT FROM PUBMED

Using the PP-ICONS approach, physicians can evaluate the validity and relevance of clinical articles in minutes using only the abstract, such as this one, obtained free online from PubMed, http://www.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi. The author uses this abstract to evaluate the use of duct tape to treat common warts.

Problem. The first P in PP-ICONS is for “problem,” which refers to the clinical condition that was studied. From the abstract, it is clear that the researchers studied the same problem you are interested in, which is important since flat warts or genital warts may have responded differently. Obviously, if the problem studied were not sufficiently similar to your clinical problem, the results would not be relevant.