Allport’s Intergroup Contact Hypothesis: Its History and Influence

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Contact hypothesis was proposed by Gordon Allport (1897-1967) and states that social contact between social groups is sufficient to reduce intergroup prejudice.

However, empirical evidence suggests that this is only in certain circumstances.

Key Takeaways:

- The contact hypothesis fundamentally rests on the idea that ingroups who have more interactions with a certain outgroup tend to develop more positive perceptions and fewer negative perceptions of that outgroup.

- Theorists have long been interested in intergroup conflict . However, Robin Williams and Gordon Allport proposed a number of conditions for ameliorating intergroup conflict that has formed the basis of empirical research for several decades.

- Allport suggests four “positive factors” leading to better intergroup relations; however, recent research suggests that these factors can facilitate but are not necessary for reducing intergroup prejudice.

- Although originally studied in the context of race and ethnic relations, the contact hypothesis has applicability between ingroup-outgroup relations across religion, age, sexuality, disease status, economic circumstances, and so on.

Contact Hypothesis

The Contact Hypothesis is a psychological theory that suggests that direct contact between members of different social or cultural groups can reduce prejudice, improve intergroup relations, and promote mutual understanding.

According to this hypothesis, interpersonal contact can lead to positive attitudes, decreased stereotypes, and increased acceptance between individuals from different groups under certain conditions.

The Contact Hypothesis was first proposed by Gordon W. Allport in 1954 and has since been supported by numerous studies in the field of social psychology. T

The contact theory suggests that contact between groups is more likely to be effective in reducing prejudice and improving relations if it meets specific criteria:

1. Equal Status Between Groups

Members of the contact situation should not have an unequal, hierarchical relationship (e.g., teacher/student, employer/employee).

Both groups perceive the other to be of equal status in the situation (Cohen, 1982; Riordan and Ruggiero, 1980; Pettigrew and Tropp, 2005).

Although some scholars emphasize that groups should be of equal status both prior to (Brewer and Kramer, 1985) and during (Foster and Finchilescu, 1986) a contact situation, research demonstrated that equal status could promote positive intergroup attitudes even when the groups initially differ in status (Patchen, 1982; Schofield and Rich-Fulcher, 2001).

2. Common Goals

Members must rely on each other to achieve their shared desired goal. To have effective contact, typically, groups need to be making an active effort toward a goal that the groups share.

For example, a national football team (Chu and Griffey, 1985; Patchen, 1982) could draw from many people of different races and ethnic origins — people from different groups — in working together and replying to each other to achieve their shared goals of winning. This tends to lead to Allport’s third characteristic of intergroup contact; intergroup cooperation (Pettigrew and Tropp, 2005).

3. Intergroup Cooperation

Members should work together in a non-competitive environment.

According to Allport (1954), the attainment of these common goals must be based on cooperation over competition. For example, in Sheriff et al. ‘s (1961) Robbers’ Cave field study , researchers devised barriers to common goals, such as a planned picnic that could only be resolved with cooperation between both groups.

This intergroup cooperation encourages positive relations between the groups. Another instance of intergroup cooperation has been studied in schools (e.g., Brewer and Miller, 1984; Johnson, Johnson, and Maruyama, 1984; Schofield, 1986).

For example, Elliot Aronson developed a “jigsaw” approach such that students from diverse backgrounds work toward common goals, fostering positive relationships among children worldwide (Aronson, 2002).

4. The Support of Authorities, Law, or Custom

The support of authorities, law, and customs also tend to lead to more positive intergroup contact effects because authorities can establish norms of acceptance and guidelines for how group members should interact with each other.

There should not be official laws enforcing segregation. This importance has been demonstrated in such wide-ranging circumstances as the military (Landis, Hope, and Day, 1983), business (Morrison and Herlihy, 1992), and religion (Parker, 1968).

Legislation, such as the civil-rights acts in American society, can also be instrumental in establishing anti-prejudicial norms (Pettigrew and Tropp, 2005).

5. Positive Contact Norms

The belief in positive contact norms refers to the understanding that positive interactions between individuals from different groups are the norm and valued by society.

When individuals perceive that positive contact is socially accepted and encouraged, it can increase the effectiveness of intergroup contact.

6. Personal Accountability

A belief in personal accountability for one’s actions and attitudes is important for effective intergroup contact.

Taking responsibility for one’s biases, stereotypes, and prejudices and actively working towards changing them, can contribute to positive intergroup relationships.

7. Empathy and Perspective-Taking

The belief in the importance of empathy and perspective-taking can enhance intergroup contact.

When individuals try to understand and empathize with the experiences and perspectives of members from other groups, it can lead to greater mutual understanding and positive relationships.

Why Does Contact Reduce Prejudice?

Brewer and Miller (1996) and Brewer and Brown (1998) suggest that these conditions can be viewed as an application of dissonance theory (Festinger, 1957).

Specifically, when individuals with negative attitudes toward specific groups find themselves in situations in which they engage in positive social interactions with members of those groups, their behavior is inconsistent with their attitudes.

This dissonance, it is theorized, may result in a change of attitude to justify the new behavior if the situation is structured so as to satisfy the above four conditions.

In contrast, Forbes (1997) asserts that most social scientists implicitly assume that increased interracial/ethnic contact reduces tension between groups by giving each information about the other.

Those who write, adopt, participate in or evaluate prejudice reduction programs are likely to have explicit or implicit informal theories about how prejudice reduction programs work.

Examples of Contact Hypothesis

Homelessness.

Historically, in contact hypothesis research, racial and ethnic minorities have been the out-group of choice; however, the hypothesis can extend to out-groups created by a number of factors. One such alienating situation is homelessness.

Like many out-groups, homeless people are more visible than they once were because of their growth in number as well as extensive media and policy coverage.

This has elicited a large amount of stigmatization and associations between homelessness and poor physical and mental health, substance abuse, and criminality, and ethnographic studies have revealed that homeless people are regularly degraded, avoided, or treated as non-persons by passersby (Anderson, Snow, and Cress, 1994).

Lee, Farrell, and Link (2004) used data from a national survey of public attitudes toward homeless people to evaluate the applicability of the contact hypothesis to relationships between homeless and housed people, even in the absence of Allport’s four positive factors.

The researchers found that even taking selection and social desirability biases into account, general exposure to homeless people tended to affect public attitudes toward homeless people favorably (Lee, Farrell, and Link, 2004).

Contact Between Age Groups

In the 1980s, there was a trend of pervasive age segregation in American society, with children and adults tending to pursue their own separate and independent lives (Caspi, 1984).

This had consequences such as a lack of transmission of work skills and culture, poor preparation for parenthood, and generally inaccurate stereotypes and unfavorable attitudes toward other age groups.

Caspi (1984) assessed the effects of cross-age contact on the attitudes of children toward older adults by comparing children attending an age-integrated preschool to children attending a traditional preschool.

Those in the age-integrated preschool (having daily contact with older adults) tended to hold positive attitudes toward older adults, while those without such contact tended to hold vague or indifferent attitudes.

In addition, children placed in the age-integrated preschool show better differentiation between adult age groups than those not in that preschool.

These findings were among the first to suggest that Allport’s contact hypothesis held relevance in intergroup contact beyond race relations (Caspi, 1984).

Contact Between Religious Groups in Indonesia and the Philippines

Following a resurgence of religion-related conflict and religiously motivated intolerance and violence and the 1999-2002 outbreak of sectarian violence in Ambon, Indonesia, between Christians and Muslims, researchers have become motivated to find ways to reduce acts of religiously motivated intolerance.

Kanas, Scheepers, and Sterkens (2015) examined the relationship between interreligious contact and negative attitudes toward religious out-groups by conducting surveys of Christian and Muslim students in Indonesia and the Philippines.

They attempted to answer the following questions (Kanas, Sccheeepers, and Sterkens, 2015):

- Does positive interreligious contact reduce, while negative interreligious contact induces negative attitudes towards the religious out-group?

- Does the perception of group threat provide a valid mechanism for both the positive and negative effects of interreligious contact?

- Does positive interreligious contact reduce negative out-group attitudes when intergroup relations are tense and both groups experience extreme conflict and violence?

The researchers focused on four ethnically and religiously diverse regions of Indonesia and the Philippines: Maluku and Yogyakarta, the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, and Metro Manila, with Maluku and the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao having more substantial religious conflicts than the other two regions.

Kanas, Scheepers, and Sterkens found that even accounting for the effects of self-selection, interreligious friendships reduced negative attitudes toward the religious out-group, while casual interreligious contact tended to increase negative out-group attitudes.

In regions experiencing more interreligious violence, there was no effect on interreligious friendships but a further deterioration in effect between casual interreligious contact and negative out-group attitudes.

Kanas, Scheepers, and Sterrkens believed that this effect could be explained by perceived group threat.

Evaluating the Contact Hypothesis

Allport’s testable formulation of the Contact Hypothesis has spawned research using a wide range of approaches, such as field studies, laboratory experiments, surveys, and archival research.

Pettigrew and Tropp (2005) conducted a 5-year meta-analysis on 515 studies (a method where researchers gather data from every possible study and statistically pool results to examine overall patterns) to uncover the overall effects of intergroup contact on prejudice and assess the specific factors that Allport identified as important for successful intergroup contact.

These studies ranged from the 1940s to the year 2000 and represented responses from 250,493 individuals across 38 countries.

The researchers found that, in general, greater levels of intergroup contact were associated with lower levels of prejudice and that more rigorous research studies actually revealed stronger relationships between contact and lowered prejudice (Pettigrew and Tropp, 2005).

The meta-analysis showed that the positive effects of contact on group relations vary dramatically between the nature of the groups, such as age, sexual orientation, disability, and mental illness, with the largest contact effects emerging for contact between heterosexuals and non-heterosexuals.

The smallest contact effects happened between those with and without mental and physical disabilities (Pettigrew and Tropp, 2005).

Although meta-analyses, such as Pettigrew and Tropp’s (2005) show that there is a strong association between intergroup contact and decreased prejudice, whether or not Allport’s four conditions hold is more widely contested.

Some researchers have suggested that the inverse relationship between contact and prejudice still persists in situations that do not match Allport’s key conditions, albeit not as strong as when they are present (Pettigrew and Tropp, 2005).

Gordon Allport taught sociology as a young man in Turkey (Nicholson, 2003) but emphasized proximal and immediate causes and disregarded larger-level, societal causes of intergroup effects.

As a result, both Allport and Williams (1947) doubted whether contact in itself reduced intergroup prejudice and thus attempted to specify a set of “positive conditions” where intergroup contact did.

Researchers have criticized Allport’s “positive factors” approach because it invites the addition of different situational conditions thought to be crucial that actually are not.

As a result, a number of researchers have proposed a host of additional conditions needed to achieve positive contact outcomes (e.g., Foster and Finchilescu, 1986) to the extent that it is unlikely that any contact situation would actually meet all of the conditions specified by the body of contact hypothesis researchers (Pettigrew and Tropp, 2005).

Researchers have also criticized Allport for not specifying the processes involved in intergroup contact’s effects or how these apply to other situations, the entire outgroup, or outgroups not involved in the contact (Pettigrew, 1998).

For example, Allport’s contact conditions leave open the question of whether contact with one group could lead to less prejudicial opinions of other outgroups.

All in all, Allport’s hypothesis neither reveals the processes behind the factors leading to the intergroup contact effect nor its effects on outgroups not involved in contact (Pettigrew, 1998).

Theorists have since pivoted their stance on the intergroup contact hypothesis to believing that intergroup contact generally diminishes prejudice but that a large number of facilitating factors can increase or decrease the magnitude of the effect.

In fact, according to newer theoretical approaches, there are negative factors that can even subvert the way that contact normally reduces prejudice (Pettigrew and Tropp, 2005).

For example, groups that tend to feel anxiety and threat toward others tend to have less decreased prejudice when put in contact with other groups (Blair, Park, and Bachelor, 2003; Stephan et al., 2002).

Indeed, more recent research into the contact hypothesis has suggested that the underlying mechanism of the phenomenon is not increased knowledge about the out-group in itself but empathy with the out-group and a reduction in intergroup threat and anxiety (Pettigrew and Tropp, 2008; Kanas, Scheepers, and Sterkens, 2015).

Social Darwinists such as William Graham Sumner (1906) believed that intergroup contact almost inevitably leads to conflict. Sumner believed that because most groups believed themselves to be superior, intergroup hostility and conflict were natural and inevitable outcomes of contact.

Perspectives such as those in Jackson (1983) and Levine and Campbell (1972) make similar predictions. In the twentieth century, perspectives began to diversify.

While some theorists believed that contact between in groups, such as between races, bred “suspicion, fear, resentment, disturbance, and at times open conflict” (Baker, 1934), others, such as Lett (1945), believed that interracial contact led to “mutual understanding and regard.”

Nonetheless, these early investigations were speculative rather than empirical (Pettigrew and Tropp, 2005). The emerging field of social psychology emphasized theories of intergroup contact.

The University of Alabama researchers Sims and Patrick (1936) were among the first to conduct a study on intergroup contact but found, discouragingly, that the anti-black attitudes of northern white students increased when immersed in the then all-white University of Alabama.

Aligning more with the later work of Allport, Brophy (1946) studied race relations between blacks and whites in the nearly-desegregated Merchant Marine. The researchers found that the more voyages that white seamen took with black seamen, the more positive their racial attitudes became.

In a similar direction, white police in Philadelphia with black colleagues showed fewer objections to working with black partners, having black people join previously all-white police districts, and taking orders from qualified black police officers (Kephart, 1957; Pettigrew and Tropp, 2005).

Following these studies, Cornell University sociologist Robin Williams Jr. offered 102 propositions on intergroup relations that constituted an initial formulation of intergroup contact theory.

These propositions generally stressed that intergroup contact reduces prejudice when (Williams, 1947):

- The two groups share similar statuses, interests, and tasks;

- the situation fosters personal, intimate intergroup contact;

- participants do not fit stereotypical conceptions of their group members;

- the activities cut across group lines.

Stouffer et al. offered the first extensive field study of the effects of intergroup contact (1949).

Stouffer et al. demonstrated that white soldiers who fought alongside black soldiers in the 1944-1945 Battle of the Bulge tended to have far more positive attitudes toward their black colleagues (Pettigrew and Tropp, 2005), regardless of status or place of origin.

Researchers such as Deutsch and Collins (1951); Wilner, Walkley, and Cook (1955); and Works (1961) supported mounting evidence that contact diminished racial prejudice among both blacks and whites through their studies of racially desegregated housing projects.

Allport, G. W. (1955). The nature of prejudice. In: JSTOR.

Anderson, L., Snow, D. A., & Cress, D. (1994). Negotiating the public realm: Stigma management and collective action among the homeless. Research in Community Sociology, 1(1), 121-143.

Aronson, E. (2002). Building empathy, compassion, and achievement in the jigsaw classroom. In Improving academic achievement (pp. 209-225): Elsevier.

Baker, P. E. (1934). Negro-white adjustment in America. Journal of Negro Education, 194-204.

Blair, I. V., Park, B., & Bachelor, J. (2003). Understanding Intergroup Anxiety: Are Some People More Anxious than Others? Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 6(2), 151-169. doi:10.1177/1368430203006002002

Brewer, M. B., & Kramer, R. M. (1985). The psychology of intergroup attitudes and behavior. Annual review of psychology, 36(1), 219-243.

Brophy, I. N. (1945). The luxury of anti-Negro prejudice. Public opinion quarterly, 9(4), 456-466.

Caspi, A. (1984). Contact Hypothesis and Inter-Age Attitudes: A Field Study of Cross-Age Contact. Social Psychology Quarterly, 47(1), 74-80. doi:10.2307/3033890

Chu, D., & Griffey, D. (1985). The contact theory of racial integration: The case of sport. Sociology of Sport Journal, 2(4), 323-333.

Cohen, E. G. (1982). Expectation states and interracial interaction in school settings. Annual review of sociology, 8(1), 209-235.

Deutsch, M., & Collins, M. E. (1951). Interracial housing: A psychological evaluation of a social experiment: U of Minnesota Press.

Foster, D., & Finchilescu, G. (1986). Contact in a”non-contact”society: The case of South Africa.

Jackson, J. W. (1993). Contact theory of intergroup hostility: A review and evaluation of the theoretical and empirical literature. International Journal of Group Tensions, 23(1), 43-65.

Jackson, P. (1985). Social geography: race and racism. Progress in Human Geography, 9(1), 99-108.

Johnson, D., Johnson, R., & Maruyama, G. (1984). Goal Interdependence and Interpersonal-personal Attraction in Heterogeneous Classrooms: a meta analysis, chapter in Miller N & Brewer MB Groups in Contact: The Psychology of Desegregation. In: New York: Academic Press.

Kanas, A., Scheepers, P., & Sterkens, C. (2015). Interreligious Contact, Perceived Group Threat, and Perceived Discrimination:Predicting Negative Attitudes among Religious Minorities and Majorities in Indonesia. Social Psychology Quarterly, 78(2), 102-126. doi:10.1177/0190272514564790

Kephart, W. M. (2018). Racial factors and urban law enforcement: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Kramer, B. M. (1950). Residential contact as a determinant of attitudes toward Negroes. Harvard University.

Lee, B. A., Farrell, C. R., & Link, B. G. (2004). Revisiting the Contact Hypothesis: The Case of Public Exposure to Homelessness. American Sociological Review, 69(1), 40-63. doi:10.1177/000312240406900104

Lee, F. F. (1956). Human Relations in Interracial Housing: A Study of the Contact Hypothesis. In: JSTOR.

Lett, H. A. (1945). Techniques for achieving interracial cooperation. Harvard Educational Review, 15(1), 62-71.

LeVine, R. A., & Campbell, D. T. (1972). Ethnocentrism: Theories of conflict, ethnic attitudes, and group behavior.

MacKenzie, B. K. (1948). The importance of contact in determining attitudes toward Negroes. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 43(4), 417.

Morrison, E. W., & Herlihy, J. M. (1992). Becoming the best place to work: Managing diversity at American Express Travel related services. Diversity in the Workplace, 203-226.

Nicholson, I. A. M. (2003). Inventing personality: Gordon Allport and the science of selfhood. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association.

Parker, J. H. (1968). The Interaction of Negroes and Whites in an Integrated Church Setting. Social Forces, 46(3), 359-366. doi:10.2307/2574883

Pettigrew, T. F. (1998). INTERGROUP CONTACT THEORY. Annual review of psychology, 49(1), 65-85. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.65

Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2005). Allport’s intergroup contact hypothesis: Its history and influence. On the nature of prejudice: Fifty years after Allport, 262-277.

Riordan, C., & Ruggiero, J. (1980). Producing equal-status interracial interaction: A replication. Social Psychology Quarterly, 131-136. Schofield, J. W. (1986). Black-White contact in desegregated schools.

Schofield, J. W., & Eurich-Fulcer, R. (2004). When and How School Desegregation Improves Intergroup Relations.

Sims, V. M., & Patrick, J. R. (1936). Attitude toward the Negro of northern and southern college students. The Journal of Social Psychology, 7(2), 192-204.

Stephan, W. G., Boniecki, K. A., Ybarra, O., Bettencourt, A., Ervin, K. S., Jackson, L. A., . . . Renfro, C. L. (2002). The Role of Threats in the Racial Attitudes of Blacks and Whites. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(9), 1242-1254. doi:10.1177/01461672022812009

Stouffer, S. A., Suchman, E. A., DeVinney, L. C., Star, S. A., & Williams Jr, R. M. (1949). The american soldier: Adjustment during army life.(studies in social psychology in world war ii), vol. 1.

Sumner, W. G. (1906). Folkways: The Sociological Importance of Usages. Manners, Customs, Mores, and Morals, Ginn & Co., New York, NY.

Williams Jr, R. M. (1947). The reduction of intergroup tensions: a survey of research on problems of ethnic, racial, and religious group relations. Social Science Research Council Bulletin.

Works, E. (1961). The prejudice-interaction hypothesis from the point of view of the Negro minority group. American Journal of Sociology, 67(1), 47-52.

Further Information

Dovidio, J. F., Love, A., Schellhaas, F. M., & Hewstone, M. (2017). Reducing intergroup bias through intergroup contact: Twenty years of progress and future directions. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 20(5), 606-620.

Pettigrew, T. F., Tropp, L. R., Wagner, U., & Christ, O. (2011). Recent advances in intergroup contact theory. International journal of intercultural relations, 35(3), 271-280.

Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of personality and social psychology, 90(5), 751.

Related Articles

Social Science

Hard Determinism: Philosophy & Examples (Does Free Will Exist?)

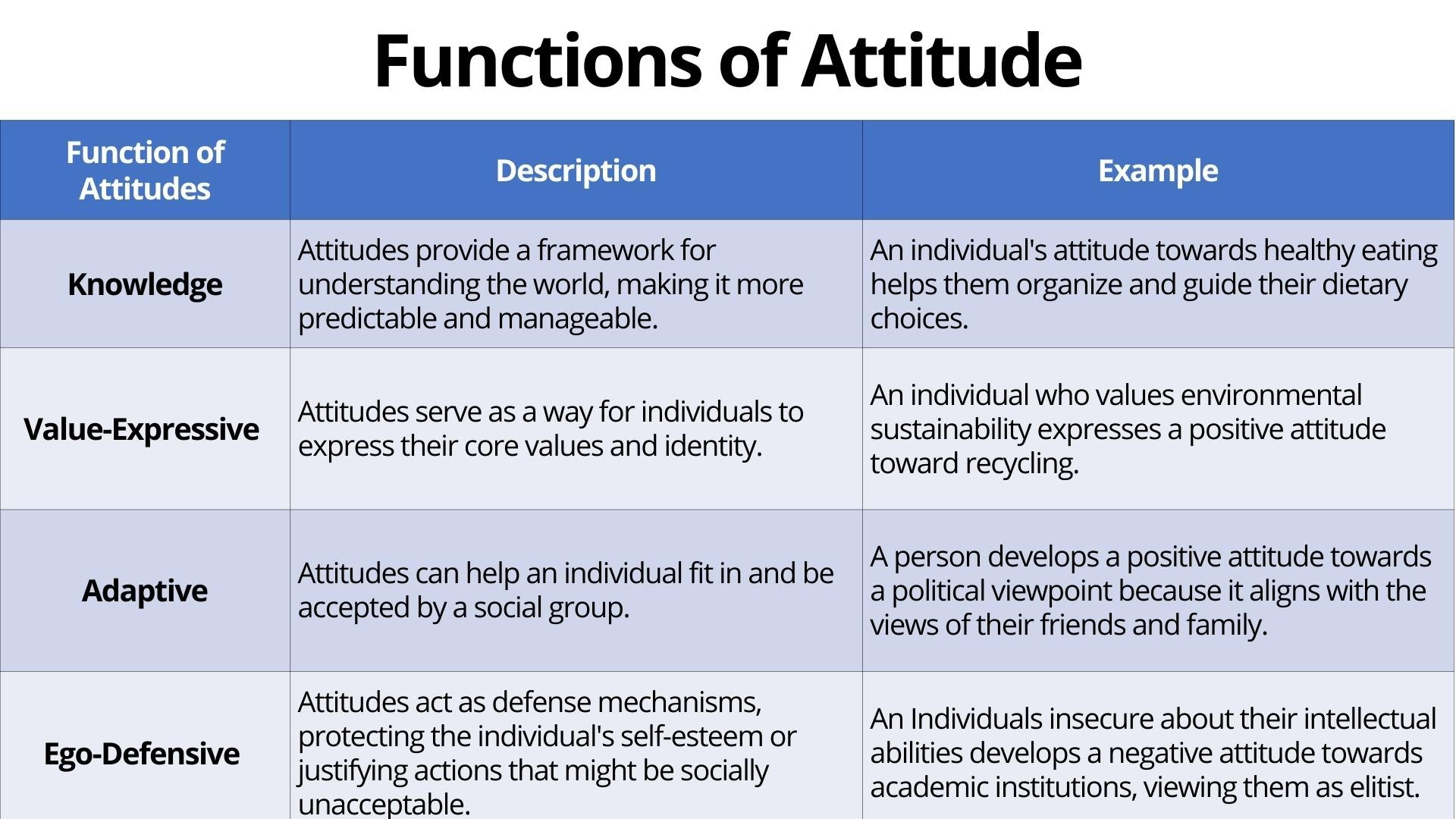

Functions of Attitude Theory

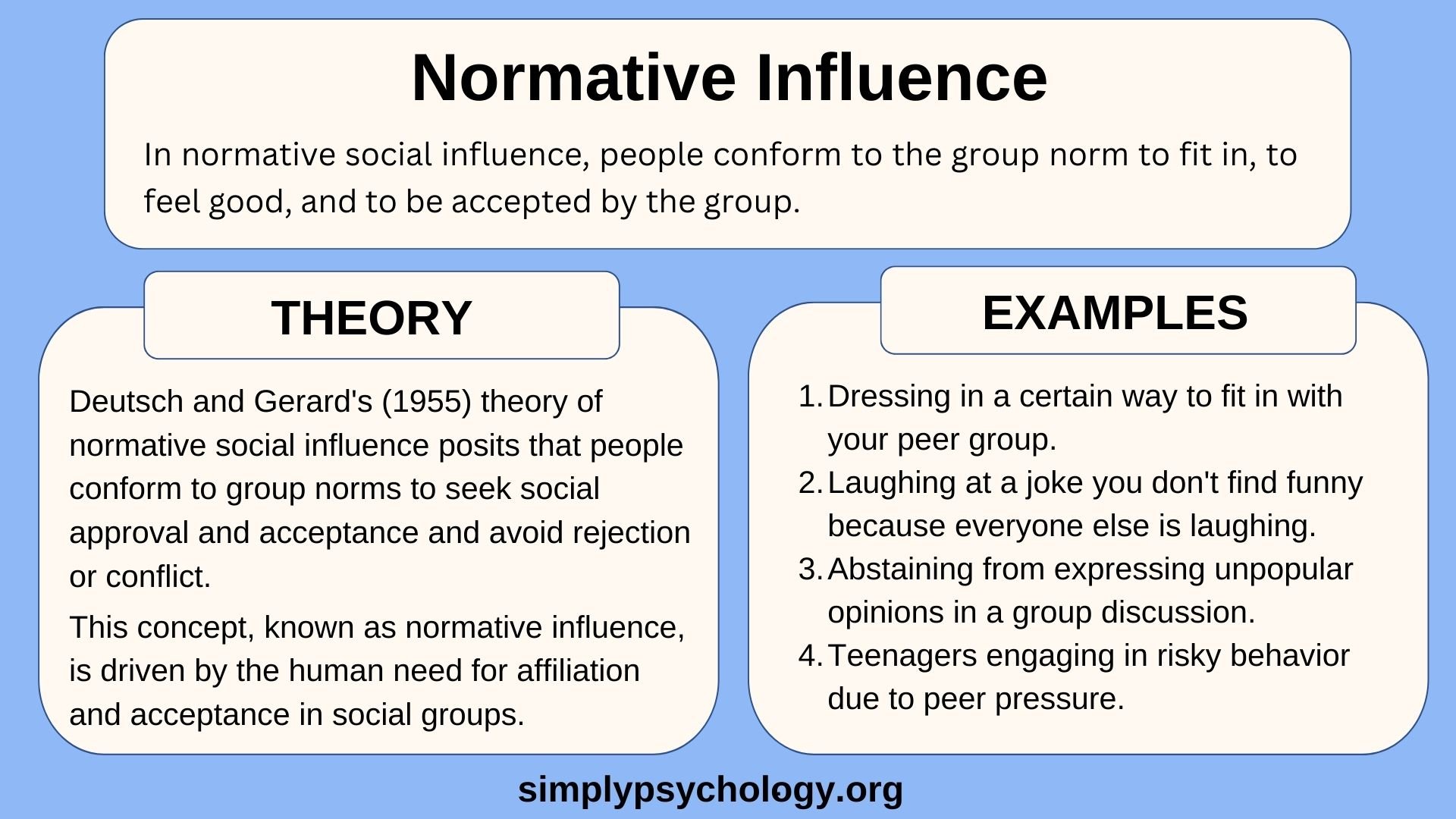

Understanding Conformity: Normative vs. Informational Social Influence

Social Control Theory of Crime

Emotions , Mood , Social Science

Emotional Labor: Definition, Examples, Types, and Consequences

Famous Experiments , Social Science

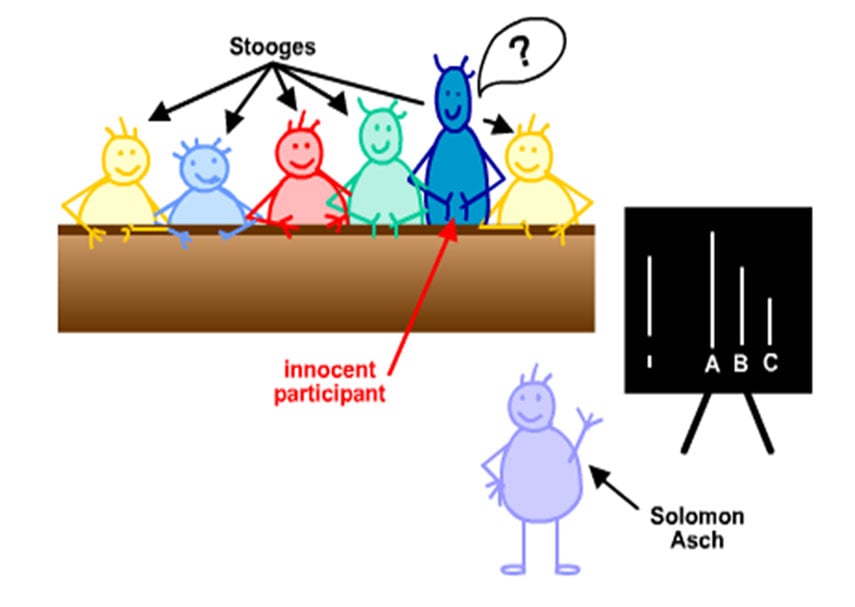

Solomon Asch Conformity Line Experiment Study

What Is the Contact Hypothesis in Psychology?

Can getting to know members of other groups reduce prejudice?

Jacob Ammentorp Lund / Getty Images

- Archaeology

- Ph.D., Psychology, University of California - Santa Barbara

- B.A., Psychology and Peace & Conflict Studies, University of California - Berkeley

The contact hypothesis is a theory in psychology which suggests that prejudice and conflict between groups can be reduced if members of the groups interact with each other.

Key Takeaways: Contact Hypothesis

- The contact hypothesis suggests that interpersonal contact between groups can reduce prejudice.

- According to Gordon Allport, who first proposed the theory, four conditions are necessary to reduce prejudice: equal status, common goals, cooperation, and institutional support.

- While the contact hypothesis has been studied most often in the context of racial prejudice, researchers have found that contact was able to reduce prejudice against members of a variety of marginalized groups.

Historical Background

The contact hypothesis was developed in the middle of the 20th century by researchers who were interested in understanding how conflict and prejudice could be reduced. Studies in the 1940s and 1950s , for example, found that contact with members of other groups was related to lower levels of prejudice. In one study from 1951 , researchers looked at how living in segregated or desegregated housing units was related to prejudice and found that, in New York (where housing was desegregated), white study participants reported lower prejudice than white participants in Newark (where housing was still segregated).

One of the key early theorists studying the contact hypothesis was Harvard psychologist Gordon Allport , who published the influential book The Nature of Prejudice in 1954. In his book, Allport reviewed previous research on intergroup contact and prejudice. He found that contact reduced prejudice in some instances, but it wasn’t a panacea—there were also cases where intergroup contact made prejudice and conflict worse. In order to account for this, Allport sought to figure out when contact worked to reduce prejudice successfully, and he developed four conditions that have been studied by later researchers.

Allport’s Four Conditions

According to Allport, contact between groups is most likely to reduce prejudice if the following four conditions are met:

- The members of the two groups have equal status. Allport believed that contact in which members of one group are treated as subordinate wouldn’t reduce prejudice—and could actually make things worse.

- The members of the two groups have common goals.

- The members of the two groups work cooperatively. Allport wrote , “Only the type of contact that leads people to do things together is likely to result in changed attitudes.”

- There is institutional support for the contact (for example, if group leaders or other authority figures support the contact between groups).

Evaluating the Contact Hypothesis

In the years since Allport published his original study, researchers have sought to test out empirically whether contact with other groups can reduce prejudice. In a 2006 paper, Thomas Pettigrew and Linda Tropp conducted a meta-analysis: they reviewed the results of over 500 previous studies—with approximately 250,000 research participants—and found support for the contact hypothesis. Moreover, they found that these results were not due to self-selection (i.e. people who were less prejudiced choosing to have contact with other groups, and people who were more prejudiced choosing to avoid contact), because contact had a beneficial effect even when participants hadn’t chosen whether or not to have contact with members of other groups.

While the contact hypothesis has been studied most often in the context of racial prejudice, the researchers found that contact was able to reduce prejudice against members of a variety of marginalized groups. For example, contact was able to reduce prejudice based on sexual orientation and prejudice against people with disabilities. The researchers also found that contact with members of one group not only reduced prejudice towards that particular group, but reduced prejudice towards members of other groups as well.

What about Allport’s four conditions? The researchers found a larger effect on prejudice reduction when at least one of Allport’s conditions was met. However, even in studies that didn’t meet Allport’s conditions, prejudice was still reduced—suggesting that Allport’s conditions may improve relationships between groups, but they aren’t strictly necessary.

Why Does Contact Reduce Prejudice?

Researchers have suggested that contact between groups can reduce prejudice because it reduces feelings of anxiety (people may be anxious about interacting with members of a group they have had little contact with). Contact may also reduce prejudice because it increases empathy and helps people to see things from the other group’s perspective. According to psychologist Thomas Pettigrew and his colleagues , contact with another group allows people “to sense how outgroup members feel and view the world.”

Psychologist John Dovidio and his colleagues suggested that contact may reduce prejudice because it changes how we categorize others. One effect of contact can be decategorization , which involves seeing someone as an individual, rather than as only a member of their group. Another outcome of contact can be recategorization , in which people no longer see someone as part of a group that they’re in conflict with, but rather as a member of a larger, shared group.

Another reason why contact is beneficial is because it fosters the formation of friendships across group lines.

Limitations and New Research Directions

Researchers have acknowledged that intergroup contact can backfire , especially if the situation is stressful, negative, or threatening, and the group members did not choose to have contact with the other group. In his 2019 book The Power of Human , psychology researcher Adam Waytz suggested that power dynamics may complicate intergroup contact situations, and that attempts to reconcile groups that are in conflict need to consider whether there is a power imbalance between the groups. For example, he suggested that, in situations where there is a power imbalance, interactions between group members may be more likely to be productive if the less powerful group is given the opportunity to express what their experiences have been, and if the more powerful group is encouraged to practice empathy and seeing things from the less powerful group’s perspective.

Can Contact Promote Allyship?

One especially promising possibility is that contact between groups might encourage more powerful majority group members to work as allies —that is, to work to end oppression and systematic injustices. For example, Dovidio and his colleagues suggested that “contact also provides a potentially powerful opportunity for majority-group members to foster political solidarity with the minority group.” Similarly, Tropp—one of the co-authors of the meta-analysis on contact and prejudice— tells New York Magazine’s The Cut that “there’s also the potential for contact to change the future behavior of historically advantaged groups to benefit the disadvantaged.”

While contact between groups isn’t a panacea, it’s a powerful tool to reduce conflict and prejudice—and it may even encourage members of more powerful groups to become allies who advocate for the rights of members of marginalized groups.

Sources and Additional Reading:

- Allport, G. W. The Nature of Prejudice . Oxford, England: Addison-Wesley, 1954. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1954-07324-000

- Dovidio, John F., et al. “Reducing Intergroup Bias Through Intergroup Contact: Twenty Years of Progress and Future Directions.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations , vol. 20, no. 5, 2017, pp. 606-620. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430217712052

- Pettigrew, Thomas F., et al. “Recent Advances in Intergroup Contact Theory.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations , vol. 35 no. 3, 2011, pp. 271-280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.03.001

- Pettigrew, Thomas F., and Linda R. Tropp. “A Meta-Analytic Test of Intergroup Contact Theory.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , vol. 90, no. 5, 2006, pp. 751-783. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751

- Singal, Jesse. “The Contact Hypothesis Offers Hope for the World.” New York Magazine: The Cut , 10 Feb. 2017. https://www.thecut.com/2017/02/the-contact-hypothesis-offers-hope-for-the-world.html

- Waytz, Adam. The Power of Human: How Our Shared Humanity Can Help Us Create a Better World . W.W. Norton, 2019.

- What Was the Robbers Cave Experiment in Psychology?

- What Is a Microaggression? Everyday Insults With Harmful Effects

- Understanding Social Identity Theory and Its Impact on Behavior

- What Is Deindividuation in Psychology? Definition and Examples

- What Is Social Loafing? Definition and Examples

- Definition of Scapegoat, Scapegoating, and Scapegoat Theory

- What Is Stereotype Threat?

- What Is the Mere Exposure Effect in Psychology?

- What Is Mindfulness in Psychology?

- Implicit Bias: What It Means and How It Affects Behavior

- What's the Difference Between Prejudice and Racism?

- What Is Groupthink? Definition and Examples

- Understanding the Big Five Personality Traits

- Definition and Examples of Social Distance in Psychology

- What Is Flirting? A Psychological Explanation

- What Is a Contact Language?

magazine issue 2 2013 / Issue 17

Justice seems not to be for all: exploring the scope of justice.

written by Aline Lima-Nunes, Cicero Roberto Pereira & Isabel Correia

That human touch that means so much: Exploring the tactile dimension of social life

written by Mandy Tjew A Sin & Sander Koole

Intergroup Contact Theory: Past, Present, and Future

- written by Jim A. C. Everett

- edited by Diana Onu

In the midst of racial segregation in the U.S.A and the ‘Jim Crow Laws’, Gordon Allport (1954) proposed one of the most important social psychological events of the 20th century, suggesting that contact between members of different groups (under certain conditions) can work to reduce prejudice and intergroup conflict . Indeed, the idea that contact between members of different groups can help to reduce prejudice and improve social relations is one that is enshrined in policy-making all over the globe. UNESCO, for example, asserts that contact between members of different groups is key to improving social relations. Furthermore, explicit policy-driven moves for greater contact have played an important role in improving social relations between races in the U.S.A, in improving relationships between Protestants and Catholics in Northern Ireland, and encouraging a more inclusive society in post-Apartheid South Africa. In the present world, it is this recognition of the benefits of contact that drives modern school exchanges and cross-group buddy schemes. In the years since Allport’s initial intergroup contact hypothesis , much research has been devoted to expanding and exploring his contact hypothesis . In this article I will review some of the vast literature on the role of contact in reducing prejudice , looking at its success, mediating factors, recent theoretical extensions of the hypothesis and directions for future research. Contact is of utmost importance in reducing prejudice and promoting a more tolerant and integrated society and as such is a prime example of the real life applications that psychology can offer the world.

The Contact Hypothesis

The intergroup contact hypothesis was first proposed by Allport (1954), who suggested that positive effects of intergroup contact occur in contact situations characterized by four key conditions: equal status, intergroup cooperation , common goals, and support by social and institutional authorities (See Table 1). According to Allport, it is essential that the contact situation exhibits these factors to some degree. Indeed, these factors do appear to be important in reducing prejudice , as exemplified by the unique importance of cross-group friendships in reducing prejudice (Pettigrew, 1998). Most friends have equal status, work together to achieve shared goals, and friendship is usually absent from strict societal and institutional limitation that can particularly limit romantic relationships (e.g. laws against intermarriage) and working relationships (e.g. segregation laws, or differential statuses).

Since Allport first formulated his contact hypothesis , much work has confirmed the importance of contact in reducing prejudice . Crucially, positive contact experiences have been shown to reduce self-reported prejudice (the most common way of assessing intergroup attitudes) towards Black neighbors, the elderly, gay men, and the disabled - to name just a few (Works, 1961; Caspi, 1984; Vonofako, Hewstone, & Voci, 2007; Yuker & Hurley, 1987). Most interestingly, though, in a wide-scale meta-analysis (i.e., a statistical analysis of a number of published studies), it has been found that while contact under Allport’s conditions is especially effective at reducing prejudice , even unstructured contact reduces prejudice (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006). What this means is that Allport’s proposed conditions should be best be seen as of a facilitating, rather than an essential, nature. This is important as it serves to show the importance of the contact hypothesis : even in situations which are not marked by Allport’s optimal conditions, levels of contact and prejudice have a negative correlation with an effect size comparable to those of the inverse relationship between condom use and sexually transmitted HIV and the relationship between passive smoking and the incidence of lung cancer at work (Al-Ramiah & Hewstone, 2011). Contact between groups, even in sub-optimal conditions, is strongly associated with reduced prejudice .

Importantly, contact does not just influence explicit self-report measures of prejudice , but also reduces prejudice as measured in a number of different ways. Explicit measures (e.g. ‘How much do you like gay men?’) are limited in that there can be a self-report bias: people often answer in a way that shows them in a good light. As such, research has examined the effects of contact on implicit measures: measures that involve investigating core psychological constructs in ways that bypass people’s willingness and ability to report their feelings and beliefs. Implicit measures have been shown to be a good complement to traditional explicit measures - particularly when there may be a strong chance of a self-report bias. In computer reaction time tasks, contact has been shown to reduce implicit associations between the participant’s own in-group and the concept ‘good’, and between an outgroup (a group the participant is not a member of) and the concept ‘bad’ (Aberson and Haag, 2007). Furthermore, positive contact is associated with reduced physiological threat responses to outgroup members (Blascovich et al., 2001), and reduced differences in the way that faces are processed in the brain, implying that contact helps to increase perceptions of similarity (Walker et al., 2008). Contact, then, has a real and tangible effect on reducing prejudice – both at the explicit and implicit level. Indeed, the role of contact in reducing prejudice is now so well documented that it justifies being referred to as intergroup contact theory (Hewstone & Swart, 2011).

How does it work?

Multiple mechanisms have been proposed to explain just how contact reduces prejudice . In particular, “four processes of change” have been proposed: learning about the out-group , changing behavior, generating affective ties, and in-group reappraisal (Pettigrew, 1998). Contact can, and does, work through both cognitive (i.e. learning about the out-group , or reappraising how one thinks about one’s own in-group ), behavioural (changing one’s behavior to open oneself to potential positive contact experiences), and affective (generating affective ties and friendships, and reducing negative emotions) means. A particularly important mediating mechanism (i.e. the mechanisms or processes by which contact achieves its effect) is that of emotions, or affect, with evidence suggesting that contact works to reduce prejudice by diminishing negative affect (anxiety / threat) and inducing positive affect such as empathy (Tausch and Hewstone, 2010). In another meta-analysis , Pettigrew and Tropp (2008) supported this by looking specifically at mediating mechanisms in contact and found that contact situations which promote positive affect and reduce negative affect are most likely to succeed in conflict reduction. Contact situations are likely to be effective at improving intergroup relations insofar as they induce positive affect, and ineffective insofar as they induce negative affect such as anxiety or threat. If we feel comfortable and not anxious, the contact situation will be much more successful.

Generalizing the effect

An important issue that I have not yet addressed, however, is how these positive experiences after contact can be extended and generalized to other members of the outgroup . While contact may reduce an individual’s prejudice towards (for example) their Muslim colleague, its practical use is strongly limited if it doesn’t also diminish prejudice towards other Muslims. Contact with each and every member of an outgroup – let alone of all out-groups to which prejudice is directed – is clearly unfeasible and so a crucial question in intergroup contact research is how the positive effect can be generalized.

A number of approaches have been developed to explain how the positive effect of contact, including making group saliency low so that people focus on individual characteristics and not group-level attributes (Brewer & Miller, 1984), making group saliency high so that the effect is best generalized to others (Johnston & Hewstone, 1992), and making an overarching common ingroup identity salient (Gaertner, Dovidio, Anastasio, Bachman, & Rust, 1993). Each of these approaches have both advantages and disadvantages, and in particular each individual approach may be most effective at different stages of an extended contact situation. To deal with this issue Pettigrew (1998) proposed a three stage model to take place over time to optimize successful contact and generalization. First is the decategorization stage (as in Brewer & Miller, 1984), where participants’ personal (and not group) identities should be emphasized to reduce anxiety and promote interpersonal liking. Secondly, the individuals’ social categories should be made salient to achieve generalization of positive affect to the outgroup as a whole (as in Johnston & Hewstone, 1992). Finally, there is the recategorization stage, where participants’ group identities are replaced with a more superordinate group: changing group identities from ‘Us vs. Them’ to a more inclusive ‘We’ (as in Gaertner et al., 1993). This stage model could provide an effective method of generalizing the positive effects of intergroup contact.

Theoretical Extensions

Even with such work on generalization, however, it may still be unrealistic to expect that group members will have sufficient opportunities to engage in positive contact with outgroup members: sometimes positive contact between group members is incredibly difficult, if not impossible. For example, at the height of the Northern Ireland conflict, positive contact between Protestants and Catholics was nigh on impossible. As such, recent work on the role of intergroup contact in reducing prejudice has moved away from the idea that contact must necessarily include direct (face-to-face) contact between group members and instead includes the notion that indirect contact (e.g. imagined contact, or knowledge of contact among others) may also have a beneficial effect.

A first example of this approach comes from Wright, Aron, McLaughlin-Volpe, and Ropp’s (1997) extended contact hypothesis . Wright et al. propose that mere knowledge that an ingroup member has a close relationship with an outgroup member can improve outgroup attitudes, and indeed this has been supported by a series of experimental and correlational studies. For example, Shiappa, Gregg, & Hewes, (2005) have offered evidence suggesting that just watching TV shows that portrayed intergroup contact was associated with lower levels of prejudice . A second example of an indirect approach to contact comes from Crisp and Turner’s (2009) imagined contact hypothesis , which suggests that actual experiences may not be necessary to improve intergroup attitudes, and that simply imagining contact with outgroup members could improve outgroup attitudes. Indeed, this has been supported in a number of studies at both an explicit and implicit level: British Muslims (Husnu & Crisp, 2010), the elderly (Abrams, Crisp, & Marques 2008), and gay men (Turner, Crisp, & Lambert, 2007).

These more recent extensions of the contact hypothesis have offered important suggestions on how to most effectively generalize the benefits of the contact situation and make use of findings from work on mediating mechanisms. It seems that direct face-to-face contact is always not necessary, and that positive outcomes can be achieved by positive presentation of intergroup-friendships in the media and even simply by imagining interacting with an outgroup member.

Issues and Directions for Future Research

Contact, then, has important positive effects on improved intergroup relations. It does have its critics, however. Notably, Dixon, Durrheim, & Tredoux (2005) argue that while contact has been important in showing how we can promote a more tolerant society, the existing literature has an unfortunate absence of work on how intergroup contact can affect societal change: changes in outgroup attitudes from contact do not necessarily accompany changes in the ideological beliefs that sustain group inequality. For example, Jackson and Crane (1986) demonstrated that positive contact with Black individuals improved Whites’ affective reactions towards Blacks but did not change their attitudes towards policy in combating inequality in housing, jobs and education. Furthermore, contact may also have the unintended effect of weakening minority members’ motivations to engage in collective action aimed at reducing the intergroup inequalities. For example, Dixon, Durrheim, & Tredoux (2007) found that the more contact Black South Africans had with White South Africans, the less they supported policies aimed at reducing racial inequalities. Positive contact may have the unintended effect of misleading members of disadvantaged groups into believing inequality will be addressed, thus leaving the status differentials intact. As such, a fruitful direction for future research would be to investigate under what conditions contact could lead to more positive intergroup relations without diminishing legitimate protest aimed at reducing inequality. One promising suggestion is to emphasize commonalities between groups while also addressing unjust group inequalities during the contact situation. Such a contact situation could result in prejudice reduction without losing sight of group inequality (Saguy, Tausch, Dovidio, & Pratto, 2009).

A second concern with contact research is that while contact has shown to be effective for more prejudiced individuals, there can be problems with getting a more prejudiced individual into the contact situation in the first place. Crisp and Turner’s imagined contact hypothesis seems to be a good first step in tackling this problem (Crisp & Turner, 2013), though it remains to be seen if, and how, such imagined contact among prejudiced individuals can translate to direct contact. Greater work on individual differences in the efficacy of contact would provide an interesting contribution to existing work.

Conclusions

Contact, then, has been shown to be of utmost importance in reduction of prejudice and promotion of more positive intergroup attitudes. Such research has important implications for policy work. Work on contact highlights the importance of institutional support and advocation of more positive intergroup relations, the importance of equal status between groups, the importance of cooperation between groups and the importance of positive media presentations of intergroup friendships - to name just a few. As Hewstone and Swart (2011) argue,

“Theory-driven social psychology does matter, not just in the laboratory, but also in the school, the neighborhood, and the society at large” (Hewstone & Swart, 2011. p.380).

- Aberson, C. L., & Haag, S. C. (2007). Contact, perspective taking, and anxiety as predictors of stereotype endorsement, explicit attitudes, and implicit attitudes. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 10 , 179–201.

- Abrams, D. and Crisp, R.J. & Marques, S., (2008). Threat inoculation: Experienced and Imagined intergenerational contact prevent stereotype threat effects on older peoples math performance. Psychology and Aging, 23 (4), 934-939.

- Al Ramiah, A., & Hewstone, M. (2011). Intergroup difference and harmony: The role of intergroup contact. In P. Singh, P. Bain, C-H. Leong, G. Misra, and Y. Ohtsubo. (Eds.), Individual, group and cultural processes in changing societies. Progress in Asian Social Psychology (Series 8), pp. 3-22. Delhi: University Press.

- Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice . Cambridge/Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Aronson, E., & Patnoe, S. (1997). The jigsaw classroom: Building cooperation in the classroom (Vol. 978, p. 0673993830). New York: Longman.

- Blascovich, J., Mendes, W. B., Hunter, S. B., Lickel, B., & Kowai-Bell, N. (2001). Perceiver threat in social interactions with stigmatized others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 253–267.

- Brewer, M. B., & Kramer, R. M. (1985). The psychology of intergroup attitudes and behavior. Annual review of psychology, 36 (1), 219-243.

- Brewer, M. B., & Miller, N. (Eds.). (1984). Groups in contact: The psychology of desegregation. Academic Press.

- Caspi, A. (1984). Contact hypothesis and inter-age attitudes: A field study of cross-age contact. Social Psychology Quarterly, 74-80.

- Chu, D., & Griffey, D. (1985). The contact theory of racial integration: The case of sport. Sociology of Sport Journal, 2 (4), 323-333.

- Cohen, E. G., & Lotan, R. A. (1995). Producing equal-status interaction in the heterogeneous classroom. American Educational Research Journal, 32 (1), 99-120.

- Crisp, R. J., & Turner, R. N. (2009). Can imagined interactions produce positive perceptions? Reducing prejudice through simulated social contact. American Psychologist, 64, 231–240.

- Crisp, R. J., & Turner, R. N. (2013). Imagined intergroup contact: Refinements, debates and clarifications. In G. Hodson & M. Hewstone (Eds.), Advances in intergroup contact. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Dixon, J., Durrheim, K., & Tredoux, C. (2005). Beyond the optimal contact strategy: A reality check for the contact hypothesis . American Psychologist, 60, 697–711.

- Dixon, J., Durrheim, K., & Tredoux, C. (2007). Intergroup contact and attitudes toward the principle and practice of racial equality. Psychological Science, 18, 867–872.

- Gaertner, S. L., Dovidio, J. F., Anastasio, P. A., Bachman, B. A., & Rust, M. C. (1993). The common ingroup identity model: Recategorization and the reduction of intergroup bias. European Review of Social Psychology, 4 (1), 1-26.

- Hewstone, M., & Swart, H. (2011). Fifty-odd years of inter-group contact: From hypothesis to integrated theory. British Journal of Social Psychology, 50 (3), 374-386.

- Husnu, S. & Crisp, R. J. (2010). Elaboration enhances the imagined contact effect. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46, 943-950

- Jackman, M.R., & Crane, M. (1986). “Some of my best friends are black...”: interracial friendship and whites’ racial attitudes. Public Opinion Quarterly 50, pp. 459–86

- Johnston, L., & Hewstone, M. (1992). Cognitive models of stereotype change: 3. Subtyping and the perceived typicality of disconfirming group members. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 28 (4), 360-386.

- Landis D., Hope R.O., & Day H.R. (1984). Training for desegregation in the military. In N. Miller & M. B. Brewer 1984, Groups in Contact: The Psychology of Desegregation, pp. 257–78. Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

- Miller, N., & Brewer M. B., eds. (1984). Groups in Contact: The Psychology of Desegregation. Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

- Pettigrew, T. F. (1998). Intergroup contact theory. Annual review of psychology, 49 (1), 65-85.

- Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta- analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90 (5), 751.

- Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2008). How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice ? Meta- analytic tests of three mediators. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38 (6), 922-934.

- Saguy, T., Tausch, N., Dovidio, J. F., & Pratto, F. (2009). The irony of harmony: Intergroup contact can produce false expectations for equality. Psychological Science, 20 , 114–121.

- Schiappa, E., Gregg, P. B., & Hewes, D. E. (2006). Can One TV Show Make a Difference? Will & Grace and the Parasocial Contact Hypothesis . Journal of Homosexuality, 51 (4), 15-37.

- Tausch, N., & Hewstone, M. (2010). Intergroup contact and prejudice . In J. F. Dovidio, M. Hewstone, P. Glick, & V. M. Esses (Eds.), The Sage handbook of prejudice , stereotyping, and discrimination (pp. 544–560). Newburg Park, CA: Sage.

- Turner, R. N., Crisp, R. J., & Lambert, E. (2007). Imagining intergroup contact can improve intergroup attitudes. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 10 , 427-441.

- Vonofakou, C., Hewstone, M., & Voci, A. (2007). Contact with outgroup friends as a predictor of meta-attitudinal strength and accessibility of attitudes towards gay men. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92 , 804–820.

- Works, E. (1961).The prejudice -interaction hypothesis from the point of view of the Negro minority group. American Journal of Sociology. 67 : 47–52

- Wright, S. C., Aron, A., McLaughlin-Volpe, T., & Ropp, S. A. (1997). The extended contact effect: Knowledge of cross-group friendships and prejudice . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73 , 73–90.

- Yuker, H. E., & Hurley, M. K. (1987). Contact with and attitudes toward persons with disabilities: The measurement of intergroup contact. Rehabilitation Psychology, 32 (3), 145.

From the editors

Everett (2013) presents an excellent overview of the research on Intergroup Contact Theory and how psychologists have used it to understand prejudice and conflict. As the article notes, friendship between members of different groups is one form of contact that helps dissolve inter-group conflict. Friendships are beneficial because of “self-expansion,” which is a fundamental motivational process that drives people to grow and integrate new things into their lives (Aron, Norman, & Aron, 1998). When an individual learns something or experiences something for the first time, his/her mind literally grows. When friendships are very intimate, people include aspects of their friends in their own self-concept (Aron, Aron, Tudor, & Nelson, 1991).

For example, if Scott (an American) becomes friends with Dan (a Russian), Scott might grow to appreciate Russian culture, because of their intimacy. Even the word “Russian” is now part of Scott’s own self-concept through this friendship, and Scott will have more positive feelings and attitudes toward Russians as a group. The same process happens for all kinds of other groups based race/ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, etc.

Importantly, self-expansion and intimacy through friendship do not work like magic; psychologists can’t wave a wand and make them appear. Nor does it happen through superficial small talk (e.g., “how about this crazy weather?”). Intimacy develops through deep communication: sustained, reciprocal, escalating conversations in which two friends come to know each other in a meaningful way. A Christian person might say, “I have a Jewish co-worker” (while talking about a casual acquaintance) or a Caucasian person might say, “I give money to an organization that helps starving people in Africa” or a straight person might say, “I support same-sex marriage equality because I know someone who is gay.” All of that is good, but it’s not as effective at reducing inter-group conflict as a true friendship with someone in those other groups; superficial contact has a small effect on racism, anti-Semitism, or homophobia. A recent meta-analysis (Davies, Tropp, Aron, Pettigrew, & Wright, 2011) revealed that spending lots of time with cross-group friends and having lots of in-depth communication with those friends were the two strongest predictors of change in positive attitudes and prejudice reduction.

At In-Mind, we work in a transnational team and we think this is enriching. What about you? Have you found friendships, or even working relations, across social groups? Did this lead you to have more open or positive attitudes? Or, do you have other experiences?

article author(s)

Jim A. C. Everett

Jim Everett studied for his undergraduate at the University of Oxford, gaining a First Class degree in Psychology, Philosophy, and Physiology. He completed... more

article keywords

- discrimination

- intergroup contact hypothesis

article glossary

- intergroup conflict

- recognition

- Intergroup Contact Hypothesis

- contact hypothesis

- cooperation

- meta-analysis

- stereotypes

- stereotype threat

- field study

- Memberships

Contact Hypothesis theory explained

Contact Hypothesis Theory: this article explains the Contact Hypothesis Theory in a practical way. Next to what it is, this article also highlights the intergroup contact and prejudice, stereotypes and discrimination, the conditions and contact hypothesis examples. After reading you will understand the basics of this psychology theory. Enjoy reading!

What is the Contact Hypothesis?

The contact hypothesis is a psychology theory suggesting that prejudice and conflict between groups can be reduced by allowing members of those groups to interact with one another. This notion is also called intra-group contact. Prejudice and conflict usually arise between majority and minority group members.

The background to the contact hypothesis

Social psychologist Gordon Allport is credited with conducting the first studies on intergroup contact.

Allport is also known for this research in the field of personalities . After the Second World War, social scientists and policymakers concentrated mainly on interracial contact. Allport brought these studies together in his study of intergroup contact.

In 1954, Allport published his first hypothesis concerning intergroup contact in the journal of personality and social psychology. The main premise of his article stated that intergroup contact was one of the most effective ways to reduce prejudice between groups.

Allport claimed that contact management and interpersonal contact could produce positive effects against with stereotyping, prejudice and discrimination, leading to better and more worthwhile interaction between two or more groups.

Over the years since Allport’s original article, the hypothesis has been expanded by social scientists and used for research into reducing prejudice relating to racism, disability, women and LGBTQ + people.

Empirical and meta analytical research into intergroup contact is still ongoing today.

Intergroup contact and prejudice, stereotypes and discrimination

The term “prejudice” is used to refer to a preconceived, negative view of another person, based on perceived qualities such as political affiliation, skin colour, faith, gender, disability, religion, sexuality, language, height, education, and more.

Prejudice can also refer to an unfounded belief, or to pigeonhole people or groups. Gordon Allport, the originator of the contact hypothesis, defined prejudice as a feeling, positive or negative, prior to actual experience, that is not based on fact.

Stereotypes, as defined in the contact hypothesis, are generalisations about groups of people. Stereotypes are often based on sexual orientation, religion, race, or age. Stereotypes can be positive, but are usually negative. Either way, a stereotype is a generalisation that does not take into account differences at the individual level.

Prejudice and stereotypes concern biased views regarding others, but discrimination consists of targeted action against individuals or groups based on race, religion, gender or other identifying features. Discrimination takes many forms, from pay gaps and glass ceilings to unfair housing policies.

In recent years, more and more new legislation and regulations have been introduced, designed to tackle discrimination and prejudice reduction in, for example, the workplace. It is not however possible to eliminate discrimination through legislation. Discrimination is a complex issue relating to the justice, education and political systems in a society.

Conditions for intergroup contact to reduce prejudice

Gordon Allport claimed that prejudice and conflict between groups can be reduced by having equal status contact between groups in pursuit of common goals. This effect is even greater when contact is officially sanctioned.

This can be achieved through legislation, but also through local customs and practice. In other words, there are four conditions under which prejudice can be reduced. These are:

Equal status

Both groups taking part in the contact situations must play equal roles in the relationship. The members of each group should have similar backgrounds, qualities and other features. Differences in academic background, prosperity or experience should be kept to a minimum.

Common goals

Both groups should seek to serve a higher purpose through the relationship and working together. This is a goal which can only be achieved when the two groups join forces and work together on common initiatives.

Working together

Both groups should work together to achieve their common goals, rather than in competition.

Support from the authorities through legislation

Both groups should recognise a single authority, to support contact and collaborative interaction between groups. This contact should be helpful, considerate, and foster the right attitude towards one another.

Examples of the contact hypothesis

The effect of greater contact between members of disparate groups has been the basis of many policy decisions advocating racial integration in settings such as schools, housing, workplaces and the military.

The contact hypothesis in the desegregation of education

An example of this is a 1954 landmark court decision by the US Supreme Court. The decision brought about the desegregation of schools. In this ruling, the contact hypothesis was used to demonstrate that this would increase self-esteem among racial minorities and respect between groups in general.

Studies into the implications of this decision in subsequent years did not always yield positive results. There have been studies showing that prejudice was actually reinforced and that self-esteem did not improve among minorities. The reason for this has already been set out above.

Contact between groups in schools, for example, was not always equal, nor did it take place with social supervision. These are two essential requirements or conditions for improving relationships between disparate groups.

The contact hypothesis in developing education strategies

The contact hypothesis has also proved invaluable in developing cooperative education strategies. The best known of these is the jigsaw classroom technique. This technique involves creating a particular classroom setting where students from various racial backgrounds are brought together in pursuit of a common goal.

In practice this means that students are placed in study groups of 6. The lesson is split into six elements, and each student is assigned one part of those six. That means that each student actually represents one piece in that jigsaw.

For the lesson to succeed, students need to trust one another based on their knowledge. This increases interdependence within the group, which is necessary for improving relationships between people.

Reducing prejudice

Besides it being very important to know how prejudice arises, studies on prejudice also focus on the potential to reduce prejudice. One technique widely believed to be highly effective is training people to become more empathetic towards members of other groups.

Putting yourself in someone else’s shoes makes it easier to think about what you would do in a similar situation.

Other techniques and methods used to reduce prejudice are:

- Contact with members of other groups

- Making others aware of the inconsistencies in their beliefs and values

- Legislation and regulations which promote fair and equal treatment of people in minority groups

- Creating public support and awareness

Implication of prejudice and discrimination in the workplace

Discrimination and prejudice can lead to wellbeing issues and substantial financial loss to the organisation, along with a sharp fall in employee and company morale. According to the American Psychological Association, 61% of adults face prejudice or discrimination at some time.

For some this happens at work; others face it as part of everyday life in society. Most people are aware of the negative effects this can have on employees, but discrimination and prejudice going unchecked can also have serious consequences.

Firstly, treating people unfairly can contribute to increased stress levels. This in turn leads to more wellbeing issues for those who are personally harmed or attacked. When someone is constantly worrying about discrimination or religion, he or she is forced to think about that thing all day long. Too much stress reduces sleep quality and suppresses appetite. When this becomes the norm for someone, they are going to feel chronically ill or down.

Prejudice also has a negative effect on the company in general. Companies may even suffer financial loss as a consequence. Employees who feel ill or down because of social issues are more likely to resign. The company then incurs substantial costs training new people.

Another obvious negative outcome for organisations is employees who hate management if they feel they are not being treated fairly. This negative attitude from employees has an effect on individual employee performance and ultimately also on the performance of the organisation as a whole.

The contact hypothesis in summary

The contact hypothesis, of which the intergroup contact theory is a part, is a theory from sociology and psychology which suggests that problems such as discrimination and prejudice can be drastically reduced by having more contact with people from different social groups. This notion is also called intergroup contact. Prejudice and conflict usually arise between majority and minority group members.

The social psychologist credited for his contributions in this field is Gordon Allport. Allport brought together several studies of interracial contact after the Second World War and developed the intergroup contact theory from those. His hypothesis was published in 1954. In the decades which followed, the theory was widely used in initiatives to tackle these social problems.

Prejudice is often a negative evaluation of others based on qualities such as political affiliation, age, skin colour, height, gender or other identifying features. Stereotyping resembles prejudice, but is in fact making generalisations about groups of people.

This social failing is also based on religion, gender or other identifying features which say nothing about the group as a whole. Discrimination goes a step further than prejudice and stereotypes. Discrimination is about actually treating people in a negative way based on particular identifying features such as race or education.

Gordon Allport developed four requirements or conditions necessary for reducing prejudice through increased intergroup contact. The first is that both groups should have an equal status. The members of each group should have similar backgrounds, qualities or social status.

Differences in academic background, prosperity or experience should be kept to a minimum. The second is to have common goals. The groups should not be brought together without some purpose. As mentioned too in the example above in the jigsaw classroom section, dependence on one another is stimulating, which is a prerequisite for social equality and improved relationships. This is linked to the third condition: working together.

Now it is your turn

What do you think? Are you familiar with the explanation of the contact hypothesis? Have you ever faced prejudice or discrimination? Have you ever experienced the positive effects of contact? Had you ever heard of this theory before? Do you think eliminating discrimination and prejudice is possible? What is your view on opportunity of outcome vs opportunity of equality? Do you have any other advice or additional comments?

Share your experience and knowledge in the comments box below.

More information

- Amir, Y. (1969). Contact hypothesis in ethnic relations . Psychological bulletin, 71(5), 319.

- Brewer, M. B., & Miller, N. (1984). Beyond the contact hypothesis: Theoretical . Groups in contact: The psychology of desegregation, 281.

- Paluck, E. L., Green, S. A., & Green, D. P. (2019). The contact hypothesis re-evaluated . Behavioural Public Policy, 3(2), 129-158.

- Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2005). Allport’s intergroup contact hypothesis: Its history and influence . On the nature of prejudice: Fifty years after Allport, 262-277.

How to cite this article: Janse, B. (2021). Contact Hypothesis Theory . Retrieved [insert date] from Toolshero: https://www.toolshero.com/psychology/contact-hypothesis/

Original publication date: 05/25/2021 | Last update: 08/21/2023

Add a link to this page on your website: <a href=”https://www.toolshero.com/psychology/contact-hypothesis/”>Toolshero: Contact Hypothesis Theory</a>

Did you find this article interesting?

Your rating is more than welcome or share this article via Social media!

Average rating 4.2 / 5. Vote count: 13

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Ben Janse is a young professional working at ToolsHero as Content Manager. He is also an International Business student at Rotterdam Business School where he focusses on analyzing and developing management models. Thanks to his theoretical and practical knowledge, he knows how to distinguish main- and side issues and to make the essence of each article clearly visible.

Related ARTICLES

Relative Deprivation Theory by Garry Runciman

Social Learning Theory by Albert Bandura

Respondents: the definition, meaning and the recruitment

Social Intelligence (SI) explained

Max Weber biography, books and theory

Psychotherapy: the Definition and Theory explained

Also interesting.

Psychological Safety by Amy Edmondson

Mandela effect: the meaning, basics and some examples

Barrett Model, a great motivation theory

Leave a reply cancel reply.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

BOOST YOUR SKILLS

Toolshero supports people worldwide ( 10+ million visitors from 100+ countries ) to empower themselves through an easily accessible and high-quality learning platform for personal and professional development.

By making access to scientific knowledge simple and affordable, self-development becomes attainable for everyone, including you! Join our learning platform and boost your skills with Toolshero.

POPULAR TOPICS

- Change Management

- Marketing Theories

- Problem Solving Theories

- Psychology Theories

ABOUT TOOLSHERO

- Free Toolshero e-book

- Memberships & Pricing

- Subscriber Services

- For Authors

- Publications

- Archaeology

- Art & Architecture

- Bilingual dictionaries

- Classical studies

- Encyclopedias

- English Dictionaries and Thesauri

- Language reference

- Linguistics

- Media studies

- Medicine and health

- Names studies

- Performing arts

- Science and technology

- Social sciences

- Society and culture

- Overview Pages

- Subject Reference

- English Dictionaries

- Bilingual Dictionaries

Recently viewed (0)

- Save Search

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Related Content

Related overviews.

Gordon Willard Allport (1897—1967)

More Like This

Show all results sharing these subjects:

contact hypothesis

Quick reference.

The proposition by the US psychologist Gordon W(illard) Allport (1897–1967) that sheer social contact between social groups is sufficient to reduce intergroup prejudice. Empirical evidence suggests that this is so only in certain circumstances.

From: contact hypothesis in A Dictionary of Psychology »

Subjects: Science and technology — Psychology

Related content in Oxford Reference

Reference entries, contact hypothesis n..

View all related items in Oxford Reference »

Search for: 'contact hypothesis' in Oxford Reference »

- Oxford University Press

PRINTED FROM OXFORD REFERENCE (www.oxfordreference.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2023. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single entry from a reference work in OR for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice ).

date: 19 May 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.151.9]

- 185.80.151.9

Character limit 500 /500

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

From contact to enact: reducing prejudice toward physical disability using engagement strategies.

- 1 Center for Subjectivity Research, Faculty of Humanities, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark

- 2 Stages of Science, Copenhagen, Denmark

- 3 Enactlab, Copenhagen, Denmark

- 4 Medical Museion, Department of Public Health, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark

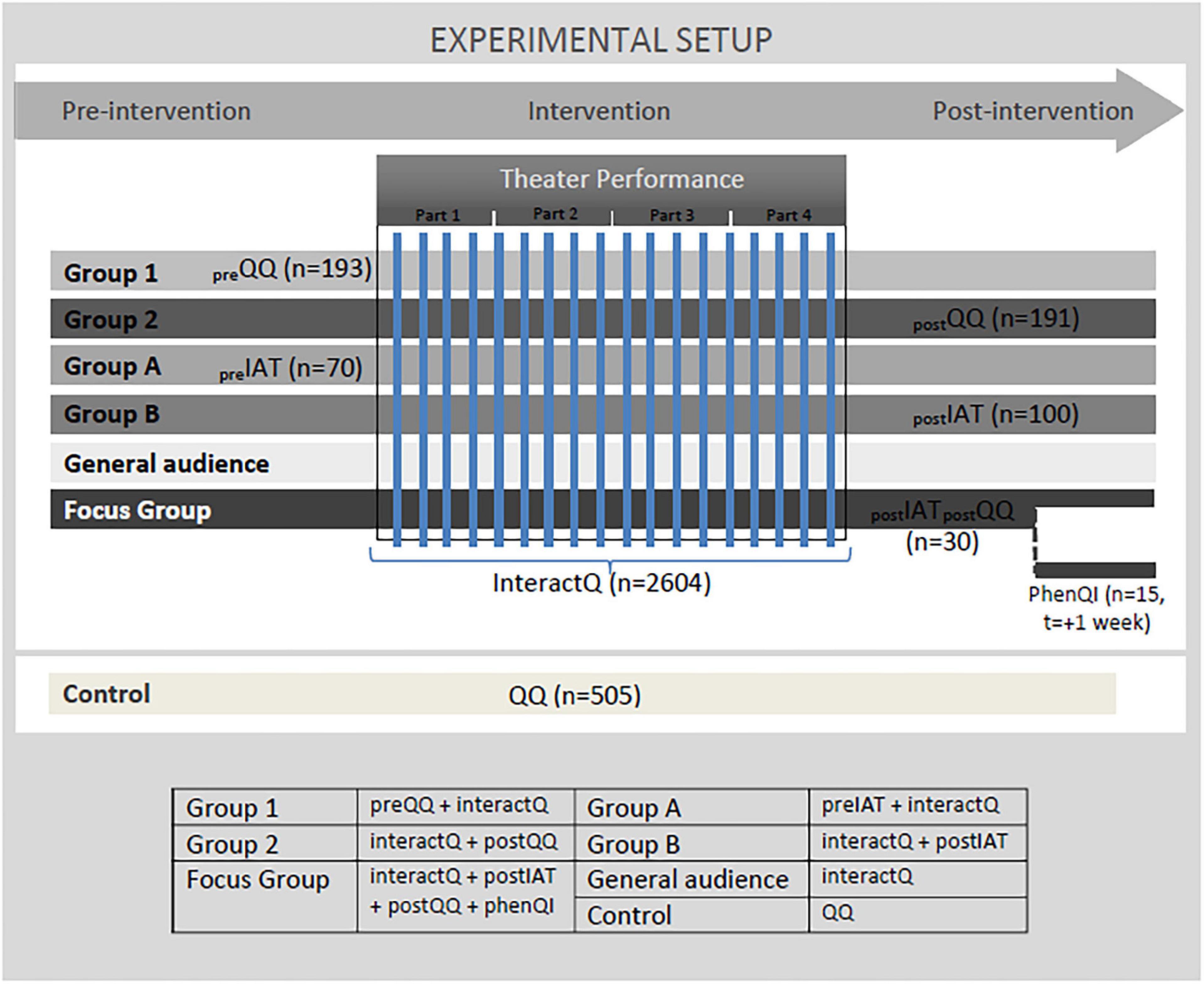

The contact hypothesis has dominated work on prejudice reduction and is often described as one of the most successful theories within social psychology. The hypothesis has nevertheless been criticized for not being applicable in real life situations due to unobtainable conditions for direct contact. Several indirect contact suggestions have been developed to solve this “application challenge.” Here, we suggest a hybrid strategy of both direct and indirect contact. Based on the second-person method developed in social psychology and cognition, we suggest working with an engagement strategy as a hybrid hypothesis. We expand on this suggestion through an engagement-based intervention, where we implement the strategy in a theater performance and investigate the effects on prejudicial attitudes toward people with physical disabilities. Based on the results we reformulate our initial engagement strategy into the Enact (Engagement, Nuancing, and Attitude formation) hypothesis. To deal with the application challenge, this hybrid hypothesis posits two necessary conditions for prejudice reduction. Interventions should: (1) work with engagement to reduce prejudice, and (2) focus on the second-order level of attitudes formation. Here the aim of the prejudice reduction is not attitude correction, but instead the nuancing of attitudes.

Introduction