Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Perspective

- Open access

- Published: 31 March 2017

Helping children with reading difficulties: some things we have learned so far

- Genevieve McArthur 1 &

- Anne Castles 1

npj Science of Learning volume 2 , Article number: 7 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

34k Accesses

22 Citations

65 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

A substantial proportion of children struggle to learn to read. This not only impairs their academic achievement, but increases their risk of social, emotional, and mental health problems. In order to help these children, reading scientists have worked hard for over a century to better understand the nature of reading difficulties and the people who have them. The aim of this perspective is to outline some of the things that we have learned so far, and to provide a framework for considering the causes of reading difficulties and the most effective ways to treat them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Reading skills intervention during the Covid-19 pandemic

Rapid online assessment of reading ability

Enhancing reading skills through a video game mixing action mechanics and cognitive training

Introduction.

Over 20 years ago, The Dyslexia Institute asked a 9-year-old boy called Alexander to describe his struggle with learning to read and spell. He bravely wrote: “I have blond her, Blue eys and an infeckshos smill. Pealpie tell mum haw gorgus I am and is ent she looky to have me. But under the surface I live in a tumoyl. Words look like swigles and riting storys is a disaster area because of spellings. There were no ply times at my old school untill work was fineshed wich ment no plytims at all. Thechers sead I was clevor but just didn’t try. Shouting was the only way the techors comuniccatid with me. Uther boys made fun of me and so I beckame lonly and mishroboll”. 1

Alexander’s experience is not unique. Sixteen per cent of children struggle to learn to read to some extent, and 5% of children have significant, severe, and persistent problems. 2 The impact of these children’s reading difficulties goes well beyond problems with reading Harry Potter or Snapchat. Poor reading is associated with increased risk for school dropout, attempted suicide, incarceration, anxiety, depression, and low self-concept. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 It is therefore important to identify and treat poor readers as early as we possibly can.

Scientists have been investigating poor reading—also known as reading difficulty, reading impairment, reading disability, reading disorder, and developmental dyslexia (to name but a few)—for over a century. While it may take another century of research to reach a complete understanding of reading impairment, there are number of things that we have learned about reading difficulties, as well as the children who experience reading them, that provide key clues about how poor reading can be identified and treated effectively.

Poor readers display different reading behaviours

One thing that we have learned about poor readers is that they are highly heterogeneous; that is, they do not all display the same type of reading impairment (i.e., “reading behaviour”; 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ). Some poor readers have a specific problem with learning to read new words accurately by applying the regular mappings between letters and sounds. 7 , 8 , 13 , 14 This problem, which is often called poor phonological recoding or decoding, can be detected by asking children to read novel “nonwords” such as YIT. Other poor readers have a particular difficulty with learning to read new words accurately that do not follow the regular mappings between letters and sounds, and hence must be read via memory representations of written words. 7 , 13 , 15 , 16 This problem, which is sometimes called poor sight word reading or poor visual word recognition, can be detected by asking children to read “exception” words such as YACHT. In contrast, some poor readers have accurate phonological recoding and visual word recognition but struggle to read words fluently. 17 , 18 , 19 Poor reading fluency can be detected by asking children to read word lists or sentences as quickly as they can. In contrast yet again, some poor readers have intact phonological recoding and visual word recognition and reading fluency, but struggle to understand the meaning of what they read. These “poor comprehenders” 20 can be identified by asking them to read paragraphs aloud (to ascertain that they can read accurately and fluently), and then ask them questions about the meaning of what they have read (to ascertain that they do not understand what they are reading). It is important to note that most poor readers have various combinations of these problems. 21 For example, Alexander’s spelling suggests that he would have poor phonological decoding (since he misspells words like playtimes as “plytims”) and poor sight word knowledge (since he misspells exception words like said as “sead”). Thus, poor readers vary considerably in the profiles of their reading behaviour.

Reading behaviours have different “proximal” causes

Another thing we have learned about poor readers is that the same reading behaviour (e.g., inaccurate reading of novel words) does not necessarily have the same “proximal cause”. A proximal cause of a reading behaviour can be defined as a component of the cognitive system that directly and immediately produces that reading behaviour. 22 , 23 , 24 Most reading behaviours will have more than one proximal cause. Reflecting this, several theoretical and computational models of reading comprise multiple cognitive components that function together to produce successful reading behaviour (e.g., refs 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 ). While these models vary in some respects, all include cognitive components that represent (1) the ability to recognise letters (e.g., S), letter-clusters (e.g., SH), and written words (e.g., SHIP), (2) the ability to recognise and produce speech sounds (e.g., “sh”, “i”, “p”) and spoken words (e.g., “ship”), (3) the ability to access stored knowledge about the meanings of words (e.g., “a floating vessel”), and (4) links between these various components. Impairment in any one of these components or links will directly and immediately impair aspects of reading behaviour. Thus, guided by theoretical and computational models, we have learned that a poor reading behaviour can have multiple proximal causes, and we have some idea about what those proximal causes might be. 10 , 11 , 12

Reading behaviours have different “distal” causes

We have also learned that even if two poor readers have exactly the same reading behaviour with exactly the same proximal cause, this reading behaviour will not necessarily have the same “distal cause”. A distal cause has a distant (i.e., an indirect or delayed) impact on a reading behaviour. 22 , 23 , 24 Distal causes reflect the fact that reading is a taught skill that unfolds over time and across development. It depends upon a range of more cognitive abilities, such as memory, attention, and language skills, to name but a few. Depending on children’s strengths and weaknesses in these underlying abilities, and how these abilities affect learning over time, children will have different profiles of developmental, or distal, causes of their reading impairment. Stated differently, there can be different causal pathways to the same impairment of the reading system.

To provide an example, as mentioned earlier, a common reading behaviour observed in poor readers is inaccurate reading of new or novel words, which can be assessed using nonwords such as YIT. Indeed, some researchers have described this as the defining symptom of reading difficulties. 29 According to theoretical and computational models of reading, one proximal cause of impaired reading of nonwords is impaired knowledge of letter-sound mappings. But what is responsible for this proximal cause of poor nonword reading? There are multiple hypotheses. The prominent “phonological deficit hypothesis” proposes a pervasive language-based difficulty in processing speech sounds that affects the ability to learn to associate written stimuli (e.g., letters) with speech sounds. 30 The “paired-associate learning deficit hypothesis” proposes a memory-based difficulty in forming cross-modal mappings across the visual (e.g, letters) and verbal domains (e.g., speech sounds) that affects letter-sound learning (e.g., ref. 31 ). And the “visual attentional deficit hypothesis” proposes an attention-based impairment in the size of the attentional window, affecting the formation of the sub-word orthographic units (e.g., letters) used in the letter-sound mapping process. 32 These three hypotheses illustrate why a single reading behaviour (e.g., poor nonword reading) with a common proximal cause (impaired knowledge of letter-sound mappings) might not have the same distal cause (e.g., a phonological deficit, a paired-associate learning deficit, or a visual attention deficit). These hypotheses also raise the possibility that the distal causes of poor readers’ reading behaviours may vary as much (if not more) than the proximal causes and the reading behaviours themselves.

Poor readers have concurrent problems with their cognition and emotional health

Another thing we have learned about poor readers is that many (but not all) have comorbidities in other aspects of their cognition and emotional health. Regarding cognition, studies have found that a significant proportion of poor readers have impairments in their spoken language. 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 Studies have also found that poor readers have atypically high rates of attention deficit disorder—a neurological problem that causes inattention, poor concentration, and distractibility (e.g., refs 40 , 41 , 42 ). Regarding emotional health, there is evidence that poor readers, as a group, have higher levels of anxiety than typical readers (e.g., refs 43 , 44 ). The same is true for low self-concept, which can be defined as a negative perception of oneself in a particular domain (e.g., academic self-concept; e.g., refs 45 , 46 ).

The fact that poor readers vary in their comorbid cognitive and emotional health problems—as well as in their reading behaviours, and the proximal and distal impairments of these behaviours—creates an impression of almost overwhelming complexity. However, it is possible to simplify this complexity somewhat using a proximal and distal schema. Specifically, comorbidities of poor reading might be categorised according to whether they represent potential proximal or distal impairment of poor reading—or possibly both. For example, a child’s current problem with spoken vocabulary might be considered a proximal cause of their poor word reading behaviour since, according to theoretical and computational models of reading, vocabulary knowledge may directly underpin word reading accuracy or reading comprehension. However, a child’s previous problem with spoken vocabulary, which may or may not still be present, might be considered a distal cause of their poor word reading: A history of poor understanding of word meanings might reduce a child’s motivation to engage in reading (distal cause), which would impair their development of phonological recoding and visual word recognition (proximal cause), and hence their word reading accuracy and fluency (reading behaviour). Thus, the proximal and distal schema can prove useful in clarifying the causal chain of events linking a reading behaviour to a potential cause.

The proximal and distal schema can also be useful in clarifying reciprocal or circular relationships between comorbidities of poor reading and reading behaviours. For example, if a poor reader has low academic self-concept (distal cause), this may stymie their motivation to pay attention in reading lessons (distal cause), which will impair their learning of letter-sound mappings (proximal cause), and hence their poor word reading (reading behaviour). At the same time, a reverse causal effect may be in play: A child’s poor word reading in the classroom (distal cause) may create a poor perception of their own academic ability (proximal cause) that lowers their academic self-concept (behaviour). Thus, the proximal and distal schema can be used to help develop hypotheses as to whether comorbidities of poor reading are proximal and/or distal causes or consequences of poor reading. Ultimately, of course, all of these hypotheses must be tested through experimental training studies.

Proximal intervention is more effective than distal intervention

Poor readers have inspired, and have been subjected to, an extraordinary array of interventions such as behavioural optometry, chiropractics, classical music, coloured glasses, computer games, fish oil, phonics, sensorimotor exercises, sound training, spatial frequency gratings, memory training, medication for the inner ear, phonemic awareness, rapid reading, visual word recognition, and vocabulary training, to name just a selection. It is noteworthy that while many of these interventions claim to be “scientifically proven”, few have been tested with a randomised controlled trial (RCT)—an experiment that randomly allocates participants to intervention and control groups in order to reduce bias in outcomes. RCTs are the gold standard method for assessing a treatment of any kind, and the method that must be used to prove the effectiveness of a pharmaceutical treatment.

In order to make sense of the chaotic variety of interventions that claim to help poor readers, it may again be helpful to use the proximal and distal schema outlined above to subdivide interventions into two types: “proximal interventions” that focus training on proximal causes of a reading behaviour that are proposed to be part of the cognitive system for reading (e.g., phonics training, vocabulary training) and “distal interventions” that focus on distal causes of a reading behaviour (e.g., coloured lenses, inner-ear medication). The idea of making a distinction between proximal and distal interventions is supported by the outcomes of a systematic review of all studies that have used an RCT to assess an intervention in poor readers. 47 These studies assessed the effect of coloured lenses or overlays, medication, motor training, phonemic awareness, phonics, reading comprehension, reading fluency, sound processing, and sunflower therapy on poor readers. One key finding of this review is that it only identified 22 RCTs, which is a small number of gold-standard intervention studies given the huge number of interventions that claim to help poor readers. A second key finding is that the majority of RCTs of interventions for poor readers have assessed the efficacy of phonics training, which trains the ability to use letter-sound mappings to learn to read new or novel words. A third key finding is that only one type of intervention produced a statistically reliable effect. This was phonics training, which focuses on improving a proximal cause of poor word reading (i.e., letter-sound mappings). In contrast, interventions that focused on distal causes of poor reading did not show a statistically reliable effect in poor readers. The outcomes of this systematic review suggest that interventions that focus on phonics—a proximal cause of reading behaviour—are more likely to be effective than interventions that focus on a distal cause. In other words, the “closer” the intervention is to an impaired reading behaviour, the more likely it is to be effective.

Translating what we know (thus far) into evidence-based practice

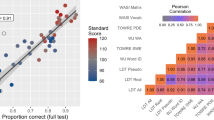

At first glance, what we have learned (so far) about poor readers and reading difficulties paints a picture of such complex heterogeneity that it is tempting to throw one’s hands up in despair. And yet, somewhat paradoxically, it is this very heterogeneity that provides some important clues about how to maximise the efficacy of intervention for poor readers. First, the fact that poor readers vary in the nature of their reading behaviours suggests that the first step in identifying an effective intervention for a poor reader is to assess different aspects of reading (e.g., word reading accuracy, reading fluency, and reading comprehension). There are numerous standardized tests provided commercially (e.g., the York Assessment for Reading Comprehension available from GL Assessment) 48 or for free (e.g., the Castles and Coltheart Word Reading Test—Second Edition (CC2) available at www.motif.org.au ) 49 that can be used to determine if a child falls below the average range for their age or grade for reading accuracy, fluency, or comprehension. In our experience, a teacher who has appropriate training in administrating such tests can carry out this first step effectively.

Second, the fact that poor readers’ reading behaviours can have different proximal causes suggests that the next step is to test them for the potential proximal causes of their poor reading behaviours. This is where cognitive models of reading are a useful roadmap, providing an explicit account of the key processes directly underpinning successful reading behaviour. Again, this can be done using standardized tests that are available commercially (e.g., the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test Fourth Edition available from Pearson) 50 or for free (e.g., the Letter-Sound Test available at www.motif.org.au ). 51 And well-trained teachers can administer these tests.

Third, the fact that poor readers vary in the degree to which they experience comorbid cognitive and emotional impairments suggests that it would be useful to assess poor readers for their spoken language abilities, attention, anxiety, depression, and self-concept, at the very least. This knowledge will reveal if they need support in other areas of their development, or if their reading-related intervention needs to be adjusted to accommodate their concomitant impairment in order to maximise efficacy. Trained speech and language therapists typically carry out the assessment of children’s spoken language; neuropsychologists are experts in assessing children’s attention; and clinical psychologists have the expertise to assess children’s emotional health.

Once a poor reader’s reading behaviours, proximal impairments, comorbid cognitive, and emotional health problems have been identified, it should be possible to design an intervention that is a good match to their needs. According to the systematic review conducted by Galuschka et al. 47 , current evidence suggests that this intervention should focus on the proximal impairment of a child’s reading behaviour, rather than a possible distal impairment. Two more recent controlled trials 52 , 53 and a systematic review 54 further suggest that it is possible to selectively train different proximal impairments of poor reading behaviours in order to improve those behaviours. The outcomes of these studies and reviews tentatively suggest that proximal interventions can be executed by a reading specialist or a highly-sophisticated online reading training programme.

In sum, over the last century or so, we have learned important things about reading difficulties and the people who have them. We have learned that poor readers display different reading behaviours, that any one reading behaviour has multiple proximal and distal causes, that some poor readers have concomitant problems in other areas of their cognition and emotional health, and that interventions that focus on proximal causes of poor reading behaviours may be more effective than those that focus on distal causes. This knowledge provides some clues to how we might best assist children with reading difficulties. Specifically, we need to assess poor readers for (1) a range of reading behaviours, (2) proximal causes for each poor reading behaviour, and (3) comorbidities in their cognition and emotional health. It should be possible to design an individualised intervention programme that accommodates for a poor reader’s comorbid cognitive or emotional problems whilst targeting the proximal causes of their poor reading behaviour or behaviours. This approach, which requires the co-ordinated efforts of teachers and specialists and parents, is no mean feat. However, according to the scientific evidence thus far, this is the most effective approach we have for helping children with reading difficulties.

The Dyslexia Institute. As I See It (Walker Books, 1990).

Shaywitz, S. E., Escobar, M. D., Shaywitz, B. A., Fletcher, J. M. & Makuch, R. Evidence that dyslexia may represent the lower tail of a normal distribution of reading ability. N. Engl. J. Med. 326 , 145–150 (1992).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Daniel, S. S. et al. Suicidality, school dropout, and reading problems among adolescents. J. Learn. Disabil. 39 , 507–514 (2006).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

McArthur, G., Castles, A., Kohnen, S. & Banales, E. Low self-concept in poor readers: prevalence, heterogeneity, and risk. Peer. J. 4 , e2669 (2016).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Carroll, J. M., Maughan, B., Goodman, R. & Meltzer, H. Literacy difficulties and psychiatric disorders: evidence for comorbidity. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 46 , 524–532 (2005).

Christie, C. A. & Yell, M. L. Preventing youth incarceration through reading remediation: issues and solutions. Read. Writ. Quart. 24 , 148–176 (2008).

Article Google Scholar

Castles, A. & Coltheart, M. Varieties of developmental dyslexia. Cognition 47 , 149–180 (1993).

Goulandris, N. K. & Snowling, M. Visual memory deficits: a plausible cause of developmental dyslexia? Evidence from a single case study. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 8 , 127–154 (1991).

Jones, K., Castles, A. & Kohnen, S. Subtypes of developmental dyslexia: recent developments and directions for treatment. ACQuiring Knowledge Speech Lang. Hear. 13 , 79–83 (2011).

Google Scholar

McArthur, G. et al. Getting to grips with the heterogeneity of developmental dyslexia. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 30 , 1–24 (2013).

Peterson, R., Pennington, B. & Olson, R. Subtypes of developmental dyslexia: testing predictions of the dual-route and connectionist frameworks. Cognition 126 , 20–38 (2013).

Ziegler, J. C. et al. Developmental dyslexia and the dual route model of reading: Simulating individual differences and subtypes. Cognition 107 , 151–178 (2008).

Manis, F. R., Seidenberg, M. S., Doi, L. M., McBride-Chang, C. & Petersen, A. On the bases of two subtypes of development dyslexia. Cognition 58 , 157–195 (1996).

Temple, C. M. & Marshall, J. C. A case study of developmental phonological dyslexia. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 74 , 517–533 (1983).

Friedmann, N. & Lukov, L. Developmental surface dyslexias. Cortex 44 , 1146–1160 (2008).

Broom, Y. M. & Doctor, E. A. Developmental phonological dyslexia: a case study of the efficacy of a remediation programme. Cogn. Neuropsychol 12 , 725–766 (1995).

de Jong, P. F. & van der Leij, A. Developmental changes in the manifestation of a phonological deficit in dyslexic children learning to read a regular orthography. Educ. Psychol 95 , 22–40 (2003).

Landerl, K., Wimmer, H. & Frith, U. The impact of orthographic consistency on dyslexia: a German-English comparison. Cognition 63 , 315–334 (1997).

Torgesen, J. K. Recent discoveries on remedial interventions for children with dyslexia. in The Science of Reading: A Handbook , (eds Snowling, M. J. & Hulme, C.), pp.521–537 (Blackwell, 2005).

Nation, K. & Snowling, M. Semantic processing and the development of word-recognition skills: evidence from children with reading comprehension difficulties. J. Mem. Lang. 39 , 85–101 (1998).

Stuart, M., & Stainthorp, R. Reading Development and Teaching (Sage, 2016).

Hulme, C., & Snowling, M. Developmental Disorders of Language, Learning and Cognition (Wiley-Blackwell, 2009).

Jackson, N. E., & Coltheart, M. Routes to Reading Success and Failure: Toward an Integrated Cognitive Psychology of Atypical Reading (Psychology Press, 2001).

Castles, A., Kohnen, S., Nickels, L. & Brock, J. Developmental disorders: what can be learned from cognitive neuropsychology? Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 369 , 20130407 (2014).

Coltheart, M., Rastle, K., Perry, C., Langdon, R. & Ziegler, J. DRC: a dual route cascaded model of visual word recognition and reading aloud. Psychol. Rev. 108 , 204 (2001).

Hoover, W. A. & Gough, P. B. The simple view of reading. Read. Writ. 2 , 127–160 (1990).

Perry, C., Ziegler, J. C. & Zorzi, M. Nested incremental modeling in the development of computational theories: the CDP+ model of reading aloud. Psychol. Rev. 114 , 273–315 (2007).

Plaut, D. C., McClelland, J. L., Seidenberg, M. S. & Patterson, K. Understanding normal and impaired word reading: computational principles in quasi-regular domains. Psychol. Rev. 103 , 56–115 (1996).

Rack, J. P., Snowling, M. J. & Olson, R. K. The nonword reading deficit in developmental dyslexia: a review. Read. Res. Q. 1 , 29–53 (1992).

Snowling, M. Dyslexia as a phonological deficit: evidence and implications. Child Psychol. Psychiatry.Rev. 3 , 4–11 (1998).

Warmington, M. & Hulme, C. Phoneme awareness, visual-verbal paired-associate learning, and rapid automatized naming as predictors of individual differences in reading ability. Sci. Studying Read. 16 , 45–62 (2012).

Bosse, M.-L., Tainturier, M. & Valdois, S. Developmental dyslexia: the visual attention span deficit hypothesis. Cognitio 104 , 198–230 (2007).

Bishop, D. V. M. & Snowling, M. J. Developmental dyslexia and specific language impairment: same or different? Psychol. Bull. 130 , 858–886 (2004).

Eisenmajer, N., Ross, N. & Pratt, C. Specificity and characteristics of learning disabilities. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 46 , 1108–1115 (2005).

Fraser, J., Goswami, U. & Conti-Ramsden, G. Dyslexia and specific language impairment: the role of phonology and auditory processing. Sci. Studies Read. 14 , 8–29 (2010).

McArthur, G. & Castles, A. Phonological processing deficits in specific reading disability and specific language impairment: same or different? J. Res. Read. 36 , 280–302 (2013).

McArthur, G. M., Hogben, J. H., Edwards, V. T., Heath, S. M. & Mengler, E. D. On the “specifics” of specific reading disability and specific language impairment. J Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Disciplines 41 , 869–874 (2000).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Rispens, J. & Been, P. Subject–verb agreement and phonological processing in developmental dyslexia and specific language impairment (SLI): a closer look. Int.J. Lang. Commun.Dis. 42 , 293–305 (2007).

Catts, H. W., Adolf, S. M., Hogan, T. P. & Weismer, S. E. Are specific language impairment and dyslexia distinct disorders? J. Speech. Lang. Hear. Res. 48 , 1378–1396 (2005).

Gilger, J. W., Pennington, B. F. & DeFries, J. C. A twin study of the etiology of comorbidity: attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and dyslexia. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 31 , 343–348 (1992).

Shaywitz, B. A., Fletcher, J. M. & Shaywitz, S. E. Defining and classifying learning disabilities and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Child. Neurol. 10 , S50–S57 (1995).

Willcutt, E. G. & Pennington, B. F. Comorbidity of reading disability and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder differences by gender and subtype. J. Learn. Disabil. 33 , 179–191 (2000).

Maughan, B. & Carroll, J. Literacy and mental disorders. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 19 , 350–354 (2006).

Mugnaini, D., Lassi, S., La Malfa, G. & Albertini, G. Internalizing correlates of dyslexia. World J. Clin. Pediatr. 5 , 255–264 (2009).

Snowling, M. J., Muter, V. & Carroll, J. Children at family risk of dyslexia: a follow-up in early adolescence. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 48 , 609–618 (2007).

Taylor, L. M., Hume, I. R. & Welsh, N. Labelling and self‐esteem: the impact of using specific vs. generic labels. Educ. Psychol. 30 , 191–202 (2010).

Galuschka, K., Ise, E., Krick, K. & Schulte-Körne, G. Effectiveness of treatment approaches for children and adolescents with reading disabilities: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE 9 , e89900 (2014).

Snowling, M. J. et al. YARC York Assessment of Reading for Comprehension Passage Reading (GL Assessment, 2009).

Castles, A. et al. Assessing the basic components of reading: a revision of the Castles and Coltheart test with new norms. Aust. J. Learn. Diffic. 14 , 67–88 (2009).

Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, D. M. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test: PPVT 4 (Pearson, 2015).

Larsen, L., Kohnen, S., Nickels, L. & McArthur, G. The letter-sound test (LeST): a reliable and valid comprehensive measure of grapheme-phoneme knowledge. Aust. J. Learn. Diffic. 20 , 129–142 (2015).

McArthur, G. et al. Sight word and phonics training in children with dyslexia. J. Learn. Disabil. 48 (4), 391–407 (2015a).

McArthur, G. et al. Replicability of sight word training and phonics training in poor readers: a randomised controlled trial. Peer. J. 3 , e922 (2015b).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

McArthur, G. et al. Phonics training for English‐speaking poor readers. The Cochrane Library . 12 , 1–102 (2012).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Cognitive Science, ARC Centre of Excellence in Cognition and its Disorders, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW, 2109, Australia

Genevieve McArthur & Anne Castles

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Genevieve McArthur .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

McArthur, G., Castles, A. Helping children with reading difficulties: some things we have learned so far. npj Science Learn 2 , 7 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-017-0008-3

Download citation

Received : 22 April 2016

Revised : 16 February 2017

Accepted : 01 March 2017

Published : 31 March 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-017-0008-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Perceptions of intelligence & sentience shape children’s interactions with robot reading companions.

- Nathan Caruana

- Ryssa Moffat

- Emily S. Cross

Scientific Reports (2023)

Deaf readers benefit from lexical feedback during orthographic processing

- Eva Gutierrez-Sigut

- Marta Vergara-Martínez

- Manuel Perea

Scientific Reports (2019)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Preventing Reading Difficulties in Young Children (1998)

Chapter: 1. introduction, 1 introduction.

Reading is essential to success in our society. The ability to read is highly valued and important for social and economic advancement. Of course, most children learn to read fairly well. In fact, a small number learn it on their own, with no formal instruction, before school entry (Anbar, 1986; Backman, 1983; Bissex, 1980; Jackson, 1991; Jackson et al., 1988). A larger percentage learn it easily, quickly, and efficiently once exposed to formal instruction.

SOCIETAL CHALLENGES

Parents, educators, community leaders, and researchers identify clear and specific worries concerning how well children are learning to read in this country. The issues they raise are the focus of this report:

1. Large numbers of school-age children, including children from all social classes, have significant difficulties in learning to read.

2. Failure to learn to read adequately for continued school success is much more likely among poor children, among nonwhite

children, and among nonnative speakers of English. Achieving educational equality requires an understanding of why these disparities exist and efforts to redress them.

3. An increasing proportion of children in American schools, particularly in certain school systems, are learning disabled, with most of the children identified as such because of difficulties in learning to read.

4. Even as federal and state governments and local communities invest at higher levels in early childhood education for children with special needs and for those from families living in poverty, these investments are often made without specific planning to address early literacy needs and sustain the investment.

5. A significant federal investment in providing bilingual education programs for nonnative speakers of English has not been matched by attention to the best methods for teaching reading in English to nonnative speakers or to native speakers of nonstandard dialects.

6. The passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) provides accommodations to children and to workers who have reading disabilities. In order to provide full access for the individuals involved, these accommodations should reflect scientific knowledge about the acquisition of reading and the effects of having a reading difficulty.

7. The debate about reading development and reading instruction has been persistent and heated, often obscuring the very real gains in knowledge of the reading process that have occurred.

In this report, we are most concerned with the children in this country whose educational careers are imperiled because they do not read well enough to ensure understanding and to meet the demands of an increasingly competitive economy. Current difficulties in reading largely originate from rising demands for literacy, not from declining absolute levels of literacy (Stedman and Kaestle, 1987). In a technological society, the demands for higher literacy are constantly increasing, creating ever more grievous consequences for those who fall short and contributing to the widening economic disparities in our society (Bronfenbrenner et al., 1996). These economic dispari-

ties often translate into disparities in educational resources, which then have the self-reinforcing effect of further exacerbating economic disparities. Although the gap in reading performance between educational haves and have-nots has shrunk over the last 50 years, it is still unacceptably large, and in recent years it has not shrunk further (National Academy of Education, 1996). These rich-get-richer and poor-get-poorer economic effects compound the difficulties facing educational policy makers, and they must be addressed if we are to confront the full scope of inadequate literacy attainment (see Bronfenbrenner et al., 1996).

Despite the many ways in which American schools have progressed and improved over the last half century (see, for example, Berliner and Biddle, 1995), there is little reason for complacency. Clear and worrisome problems have to do specifically with children's success in learning to read and our ability to teach reading to them. There are many reasons for these educational problems—none of which is simple. These issues and problems led to the initiation of this study and are the focus of this report.

The many children who succeed in reading are in classrooms that display a wide range of possible approaches to instruction. In making recommendations about instruction, one of the challenges facing the committee is the difficult-to-deal-with fact that many children will learn to read in almost any classroom, with almost any instructional emphasis. Nonetheless, some children, in particular children from poor, minority, or non-English-speaking families and children who have innate predispositions for reading difficulties, need the support of high-quality preschool and school environments and of excellent primary instruction to be sure of reading success. We attempt to identify the characteristics of the preschool and school environments that will be effective for such children.

The Challenge of a Technological Society

Although children have been taught to read for many centuries, only in this century—and until recently only in some countries—has there been widespread expectation that literacy skills should be universal. Under current conditions, in many ''literate" societies, 40 to

60 percent of the population have achieved literacy; today in the United States, we expect 100 percent of the population to be literate. Furthermore, the definition of full-fledged literacy has shifted over the last century with increased distribution of technology, with the development of communication across distances, and with the proliferation of large-scale economic enterprises (Kaestle, 1991; Miller, 1988; Weber, 1993). To be employable in the modern economy, high school graduates need to be more than merely literate. They must be able to read challenging material, to perform sophisticated calculations, and to solve problems independently (Murnane and Levy, 1993). The demands are far greater than those placed on the vast majority of schooled literate individuals a quarter-century ago.

Data from the National Education Longitudinal Study and High School and Beyond, the two most comprehensive longitudinal assessments of U.S. students' attitudes and achievements, indicate that, from 1972 through 1994 (the earliest and most recently available data), high school students most often identified two life values as "very important" (see National Center for Educational Statistics, 1995:403). "Finding steady work" was consistently highly valued by over 80 percent of male and female seniors over the 20 years of measurement and was seen as "very important'' by nearly 90 percent of the 1992 seniors—the highest scores on this measure in its 20-year history. "Being successful in work" was also consistently valued as very important by over 80 percent of seniors over the 20-year period and approached 90 percent in 1992.

The pragmatic goals stated by students amount to "get and hold a good job." Who is able to do that? In 1993, the percentage of U.S. citizens age 25 and older who were college graduates and unemployed was 2.6 percent (U.S. Department of Labor, Office of Employment and Unemployment Statistics, quoted in National Center for Education Statistics, 1995:401). By contrast, the unemployment rate for high school graduates with no college was twice as high, 5.4 percent, and for persons with less than a high school education the unemployment rate was 9.8 percent, over three times higher. An October 1994 survey of 1993-1994 high school graduates and dropouts found that fewer than 50 percent of the dropouts were holding

jobs (U.S. Department of Labor, 1995 ; quoted in National Center for Education Statistics, 1995:401).

One researcher found that, controlling for inflation, the mean income of U.S. male high school dropouts ages 25 to 34 has decreased by over 50 percent between 1973 and 1995 (Stringfield, 1995 , 1997). By contrast, the mean incomes of young male high school graduates dropped by about one-third, and those of college graduates by 20 percent in the 1970s and then stabilized. Among the six major demographic groups (males and females who are black, white, or Hispanic), the lowest average income among college graduates was higher than the highest group of high school graduates.

Academic success, as defined by high school graduation, can be predicted with reasonable accuracy by knowing someone's reading skill at the end of grade 3 (for reviews, see Slavin et al., 1994). A person who is not at least a modestly skilled reader by the end of third grade is quite unlikely to graduate from high school. Only a generation ago, this did not matter so much, because the long-term economic effects of not becoming a good reader and not graduating from high school were less severe. Perhaps not surprisingly, when teachers are asked about the most important goal for education, over half of elementary school teachers chose "building basic literacy skills" (National Center for Education Statistics Schools and Staffing Survey, 1990-1991, quoted in National Center for Education Statistics, 1995:31) .

The Special Challenge of Learning to Read English

Learning to read poses real challenges, even to children who will eventually become good readers. Furthermore, although every writing system has its own complexities, English presents a relatively large challenge, even among alphabetic languages. Learning the principles of a syllabic system, like the Japanese katakana, is quite straightforward, since the units represented—syllables—are pronounceable and psychologically real, even to young children. Such systems are, however, feasible only in languages with few possible syllable types; the hiragana syllabary represents spoken Japanese with 46 characters, supplemented with a set of diacritics (Daniels

and Bright, 1996). Spoken English has approximately 5,000 different possible syllables; instead of representing each one with a symbol in the writing system, written English relies on an alphabetic system that represents the parts that make up a spoken syllable, rather than representing the syllable as a unit.

An alphabetic system poses a challenge to the beginning reader, because the units represented graphically by letters of the alphabet are referentially meaningless and phonologically abstract. For example, there are three sounds represented by three letters in the word "but," but each sound alone does not refer to anything, and only the middle sound can really be pronounced in isolation; when we try to say the first or last consonant of the word all by itself, we have to add a vowel to make it a pronounceable entity (see Box 1-1).

Once the learner of written English gets the basic idea that letters represent the small sound units within spoken and heard words, called phonemes, the system has many advantages: a much more limited set of graphemic symbols is needed than in either syllabic (like Japanese) or morphosyllabic (like Chinese) systems; strategies

for sounding out unfamiliar strings and spelling novel words are available; and subsequences, such as prefixes and suffixes, are encountered with enough frequency for the reader to recognize them automatically.

Alphabetic systems of writing vary in the degree to which they are designed to represent the surface sounds of words. Some languages, such as Spanish, spell all words as they sound, even though this can cause two closely related words to be spelled very differently. Writing systems that compromise phonological representations in order to reflect morphological information are referred to as deep orthographies. In English, rather than preserving one-letter-to-one-sound correspondences, we preserve the spelling, even if that means a particular letter spells several different sounds. For example, the last letter pronounced "k" in the written word "electric" represents quite different sounds in the words "electricity" and ''electrician," indicating the morphological relation among the words but making the sound-symbol relationships more difficult to fathom.

The deep orthography of English is further complicated by the retention of many historical spellings, despite changes in pronunciation that render the spellings opaque. The "gh" in "night" and "neighborhood" represents a consonant that has long since disappeared from spoken English. The "ph" in "morphology" and "philosophy" is useful in signaling the Greek etymology of those words but represents a complication of the pattern of sound-symbol correspondences that has been abandoned in Spanish, German, and many other languages that also retain Greek-origin vocabulary items. English can present a challenge for a learner who expects to find each letter always linked to just one sound.

SOURCES OF READING DIFFICULTIES

Reading problems are found among every group and in every primary classroom, although some children with certain demographic characteristics are at greater risk of reading difficulties than others. Precisely how and why this happens has not been fully understood. In some cases, the sources of these reading difficulties

are relatively clear, such as biological deficits that make the processing of sound-symbol relationships difficult; in other cases, the source is experiential such as poor reading instruction.

Biological Deficits

Neuroscience research on reading has expanded understanding of the reading process (Shaywitz, 1996). For example, researchers have now been able to establish a tentative architecture for the component processes of reading (Shaywitz et al., 1998; Shaywitz, 1996). All reading difficulties, whatever their primary etiology, must express themselves through alterations of the brain systems responsible for word identification and comprehension. Even in disadvantaged or other high-risk populations, many children do learn to read, some easily and others with great difficulty. This suggests that, in all populations, reading ability occurs along a continuum, and biological factors are influenced by, and interact with, a reader's experiences. The findings of an anomalous brain system say little about the possibility for change, for remediation, or for response to treatment. It is well known that, particularly in children, neural systems are plastic and responsive to changed input.

Cognitive studies of reading have identified phonological processing as crucial to skillful reading, and so it seems logical to suspect that poor readers may have phonological processing problems. One line of research has looked at phonological processing problems that can be attributed to the underdevelopment or disruption of specific brain systems.

Genetic factors have also been implicated in some reading disabilities, in studies both of family occurrence (Pennington, 1989; Scarborough, 1989) and of twins (Olson et al., 1994). Differences in brain function and behavior associated with reading difficulty may arise from environmental and/or genetic factors. The relative contributions of these two factors to a deficit in reading (children below the local 10th percentile) have been assessed in readers with normal-range intelligence (above 90 on verbal or performance IQ) and apparent educational opportunity (their first language was English and they had regularly attended schools that were at or above national

norms in reading). This research has provided evidence for strong genetic influences on many of these children's deficits in reading (DeFries and Alarcon, 1996) and in related phonological processes (Olson et al., 1989). Recent DNA studies have found evidence for a link between some cases of reading disability and inheritance of a gene or genes on the short arm of chromosome 6 (Cardon et al., 1994; Grigorenko et al., 1997).

It is important to emphasize that evidence for genetic influence on reading difficulty in the selected population described above does not imply genetic influences on reading differences between groups for which there are confounding environmental differences. Such group differences may include socioeconomic status, English as a second language, and other cultural factors. It is also important to emphasize that evidence for genetic influence and anomalous brain development does not mean that a child is condemned to failure in reading. Brain and behavioral development are always based on the interaction between genetic and environmental influences. The genetic and neurobiological evidence does suggest why learning to read may be particularly difficult for some children and why they may require extraordinary instructional support in reading and related phonological processes.

Instructional Influences

A large number of students who should be capable of reading ably given adequate instruction are not doing so, suggesting that the instruction available to them is not appropriate. As Carroll (1963) noted more than three decades ago, if the instruction provided by a school is ineffective or insufficient, many children will have difficulty learning to read (unless additional instruction is provided in the home or elsewhere).

Reading difficulties that arise when the design of regular classroom curriculum, or its delivery, is flawed are sometimes termed "curriculum casualties" (Gickling and Thompson, 1985; Simmons and Kame'enui, in press). Consider an example from a first-grade classroom in the early part of the school year. Worksheets were being used to practice segmentation and blending of words to facili-

tate word recognition. Each worksheet had a key word, with one part of it designated the "chunk" that was alleged to have the same spelling-sound pattern in other words; these other words were listed on the sheet. One worksheet had the word "love" and the chunk "ove.'' Among the other words listed on the sheet, some did indicate the pattern ("glove," "above," "dove"), but others simply do not work as the sheet suggests they should ("Rover," "stove," and "woven"). In lesson plans and instructional activities, such mistakes occur in the accuracy and clarity of the information being taught.

When this occurs consistently, a substantial proportion of students in the classroom are likely to exhibit low achievement (although some students are likely to progress adequately in spite of the impoverished learning situation). If low-quality instruction is confined to one particular teacher, children's progress may be impeded for the year spent in that classroom, but they may overcome this setback when exposed to more adequate teaching in subsequent years. There is evidence, however, that poor instruction in first grade may have long-term effects. Children who have poor instruction in the first year are more seriously harmed by the bad early learning experience and tend to do poorly in schooling across the years (Pianta, 1990).

In some schools, however, the problem is more pervasive, such that low student achievement is schoolwide and persistent. Sometimes the instructional deficiency can be traced to lack of an appropriate curriculum. More often, a host of conditions occur together to contribute to the risk imposed by poor schooling: low expectations for success on the part of the faculty and administration of the school, which may translate into a slow-paced, undemanding curriculum; teachers who are poorly trained in effective methods for teaching beginning readers; the unavailability of books and other materials; noisy and crowded classrooms; and so forth.

It is regrettable that schools with these detrimental characteristics continue to exist anywhere in the United States; since these schools often exist in low-income areas, where resources for children's out-of-school learning are limited, the effects can be very detrimental to students' probabilities of becoming skilled readers (Kozol, 1991; Puma et al., 1997; Natriello et al., 1990). Attending a

school in which low achievement is pervasive and chronic, in and of itself, clearly places a child at risk for reading difficulty. Even within a school that serves most of its students well, an instructional basis for poor reading achievement is possible. This is almost never considered, however, when a child is referred for evaluation of a suspected reading difficulty. Evidence from case study evaluations of children referred for special education indicate that instructional histories of the children are not seriously considered (Klenk and Palincsar, 1996). Rather, when teachers refer students for special services, the "search for pathology" begins and assessment focused on the child continues until some explanatory factor is unearthed that could account for the observed difficulty in reading (Sarason and Doris, 1979).

In sum, a variety of detrimental school practices may place children at risk for poorer achievement in reading than they might otherwise attain. Interventions geared at improving beginning reading instruction, rehabilitating substandard schools, and ensuring adequate teacher preparation are discussed in subsequent chapters.

DEMOGRAPHICS OF READING DIFFICULTIES

A major source of urgency in addressing reading difficulties derives from their distribution in our society. Children from poor families, children of African American and Hispanic descent, and children attending urban schools are at much greater risk of poor reading outcomes than are middle-class, European-American, and suburban children. Studying these demographic disparities can help us identify groups that should be targeted for special prevention efforts. Furthermore, examining the literacy development of children in these higher-risk groups can help us understand something about the course of literacy development and the array of conditions that must be in place to ensure that it proceeds well.

One characteristic of minority populations that has been offered as an explanation for their higher risk of reading difficulties is the use of nonstandard varieties of English or limited proficiency in English. Speaking a nonstandard variety of English can impede the easy acquisition of English literacy by introducing greater deviations

in the representation of sounds, making it hard to develop sound-symbol links. Learning English spelling is challenging enough for speakers of standard mainstream English; these challenges are heightened for some children by a number of phonological and grammatical features of social dialects that make the relation of sound to spelling even more indirect (see Chapter 6).

The number of children who speak other languages and have limited proficiency in English in U.S. schools has risen dramatically over the past two decades and continues to grow. Although the size of the general school population has increased only slightly, the number of students acquiring English as a second language grew by 85 percent nationwide between 1985 and 1992, from fewer than 1.5 million to almost 2.7 million (Goldenberg, 1996). These students now make up approximately 5.5 percent of the population of public school students in the United States; over half (53 percent) of these students are concentrated in grades K-4. Eight percent of kindergarten children speak a native language other than English and are English-language learners (August and Hakuta, 1997).

Non-English-speaking students, like nonstandard dialect speakers, tend to come from low socioeconomic backgrounds and to attend schools with disproportionately high numbers of children in poverty, both of which are known risk factors (see Chapter 4). Hispanic students in the United States, who constitute the largest group of limited-English-proficient students by far, are particularly at risk for reading difficulties. Despite the group's progress in achievement over the past 15 to 20 years, they are about twice as likely as non-Hispanic whites to be reading below average for their age. Achievement gaps in all academic areas between whites and Hispanics, whether they are U.S. or foreign born, appear early and persist throughout their school careers (Kao and Tienda, 1995).

One obvious reason for these achievement differences is the language difference itself. Being taught and tested in English would, of course, put students with limited English proficiency at a disadvantage. These children might not have any reading difficulty at all if they were taught and tested in the language in which they are proficient. Indeed, there is evidence from research in bilingual education that learning to read in one's native language—thus offsetting the

obstacle presented by limited proficiency in English—can lead to superior achievement (Legarreta, 1979; Ramirez et al., 1991). This field is highly contentious and politicized, however, and there is a lack of clear consensus about the advantages and disadvantages of academic instruction in the primary language in contrast to early and intensive exposure to English (August and Hakuta, 1997; Rossell and Baker, 1996).

In any event, limited proficiency in English does not, in and of itself, appear to be entirely responsible for the low reading achievement of these students. Even when taught and tested in Spanish, as the theory and practice of bilingual education dictates, many Spanish-speaking Hispanic students in the United States still demonstrate low levels of reading attainment (Escamilla, 1994; Gersten and Woodward, 1995; Goldenberg and Gallimore, 1991; Slavin and Madden, 1995). This suggests that factors other than lack of English proficiency may also contribute to these children's reading difficulties.

One such factor is cultural differences, that is, the mismatch between the schools and the families in definitions of literacy, in teaching practices, and in defined roles for parents versus teachers (e.g., Jacob and Jordan, 1987; Tharp, 1989); these differences can create obstacles to children's learning to read in school. Others contend that primary cultural differences matter far less than do "secondary cultural discontinuities," such as low motivation and low educational aspirations that are the result of discrimination and limited social and economic opportunities for certain minority groups (Ogbu, 1974, 1982). Still others claim that high motivation and educational aspirations can and do coexist with low achievement (e.g., Labov et al., 1968, working in the African American community; Goldenberg and Gallimore, 1995, in the Hispanic community) and that other factors must therefore explain the differential achievement of culturally diverse groups.

Literacy is positively valued by adults in minority communities, and the positive views are often brought to school by young children (Nettles, 1997). Nonetheless, the ways that reading is used by adults and children varies across families from different cultural groups in ways that may influence children's participation in literacy activities

in school, as Heath (1983) found. And adults in some communities may see very few functional roles for literacy, so that they will be unlikely to provide conditions in the home that are conducive to children's acquisition of reading and writing skills (Purcell-Gates, 1991, 1996). The implications of these various views for prevention and intervention efforts are discussed in Part III of this volume.

It is difficult to distinguish the risk associated with minority status and not speaking English from the risk associated with lower socioeconomic status (SES). Studying the differential experiences of children in middle- and lower-class families can illuminate the factors that affect the development of literacy and thus contribute to the design of prevention and intervention efforts.

The most extensive studies of SES differences have been conducted in Britain. Stubbs (1980) found a much lower percentage of poor readers with higher (7.5 percent) than with lower SES (26.9 percent). Some have suggested that SES differences in reading achievement are actually a result of differences in the quality of schooling; that is, lower-SES children tend to go to inferior schools, and therefore their achievement is lower because of inferior educational opportunities (Cook, 1991). However, a recent study by Alexander and Entwisle (1996) appears to demonstrate that it is during nonschool time—before they start and during the summer months—that low-SES children fall academically behind their higher-SES peers and get progressively further behind. During the school months (at least through elementary school) the rate of progress is virtually identical for high- and low-SES children.

Regardless of the specific explanation, differences in literacy achievement among children as a result of socioeconomic status are pronounced. Thirty years ago Coleman et al. (1966) and Moynihan (1965) reported that the educational deficit of children from low-income families was present at school entry and increased with each year they stayed in school. Evidence of SES differences in reading achievement has continued to accumulate (National Assessment of Educational Progress, 1981, 1995). Reading achievement of children in affluent suburban schools is significantly and consistently higher than that of children in "disadvantaged" urban schools (e.g.,

NAEP, 1994, 1995; White, 1982; Hart and Risley, 1995). An important conceptual distinction was made by White (1982) in a groundbreaking meta-analysis. White discovered that, at the individual level, SES is related to achievement only very modestly. However, at the aggregate level, that is, when measured as a school or community characteristic, the effects of SES are much more pronounced. A low-SES child in a generally moderate or higher-SES school or community is far less at risk than an entire school or community of low-SES children.

The existence of SES differences in reading outcomes offers by itself little information about the specific experiences or activities that influence literacy development at home. Indeed, a look at socioeconomic factors alone can do no more than nominate the elements that differ between middle-class and lower-class homes. Researchers have tried to identify the specific familial interactions that can account for social class differences, as well as describe those interactions around literacy that do occur in low-income homes. For example, Baker et al. (1995) compared opportunities for informal literacy learning among preschoolers in the homes of middle-income and low-income urban families. They found that children from middle-income homes had greater opportunities for informal literacy learning than children of low-income homes. Low-income parents, particularly African-American parents, reported more reading skills practice and homework (e.g., flash cards, letter practice) with their kindergarten-age children than did middle-income parents. Middle-income parents reported only slightly more joint book reading with their children than did low-income families. But these middle-income parents reported more play with print and more independent reading by children. Among the middle-class families in this study, 90 percent reported that their child visited the library at least once a month, whereas only 43 percent of the low-income families reported such visits. The findings of Baker et al. that low-income homes typically do offer opportunities for literacy practice, though perhaps of a different nature from middle-class homes, have been confirmed in ethnographic work by researchers such as Teale (1986), Taylor and Dorsey-Gaines (1988), Taylor and Strickland (1986), Gadsden (1993), Delgado-Gaitan (1990), and Goldenberg et al. (1992).

ABOUT THIS REPORT

Charge to the committee.

The Committee on the Prevention of Reading Difficulties in Young Children has conducted a study of the effectiveness of interventions for young children who are at risk of having problems in learning to read. It was carried out at the request of the U.S. Department of Education's Office of Special Education Programs and its Office of Educational Research and Improvement (Early Childhood Institute) and the National Institute on Child Health and Human Development (Human Learning and Behavior Branch). The sponsors requested that the study address young children who are at -risk for reading difficulties, within the context of reading acquisition for all children. The scope included children from birth through grade 3, in special and regular education settings. The project had three goals: (1) to comprehend a rich research base; (2) to translate the research findings into advice and guidance for parents, educators, publishers, and others involved in the care and instruction of the young; and (3) to convey this advice to the targeted audiences through a variety of publications, conferences, and other outreach activities. In making its recommendations, the committee has highlighted key research findings that should be integrated into existing and future program interventions to enhance the reading abilities of young children, particularly instruction at the preschool and early elementary levels.

The Committee's Perspective

Our recommendations extend to all children. Of course, we are most worried about children at high risk of developing reading difficulties. However, there is little evidence that children experiencing difficulties learning to read, even those with identifiable learning disabilities, need radically different sorts of supports than children at low risk, although they may need much more intensive support. Childhood environments that support early literacy development and

excellent instruction are important for all children. Excellent instruction is the best intervention for children who demonstrate problems learning to read.

Knowledge about reading derives from work conducted in several disciplines, in laboratory settings as well as in homes, classrooms, and schools, and from a range of methodological perspectives. Reading is studied by ethnographers, sociologists, historians, child developmentalists, neurobiologists, and psycholinguists. Reading has been approached as a matter of cognition, culture, socialization, instruction, and language. The committee that wrote this report embraces all these perspectives—but we acknowledge the difficulty of integrating them into a coherent picture.

The committee agrees that reading is inextricably embedded in educational, social, historical, cultural, and biological realities. These realities determine the meaning of terms like literate as well as limits on access to literacy and its acquisition. Literacy is also essentially developmental, and appropriate forms of participation, instruction, and assessment in literacy for preschoolers differ from those for first graders and also from those for sophisticated critical readers.

Reading as a cognitive and psycholinguistic activity requires the use of form (the written code) to obtain meaning (the message to be understood), within the context of the reader's purpose (for learning, for enjoyment, for insight). In children, one can see a developmental oscillation between these foci: the preschool child who can pretend to read a story she has heard many times is demonstrating an understanding that reading is about content or meaning; the same child as a first grader, having been taught some grapheme-phoneme correspondences, may read the same storybook haltingly, disfluently, by sounding out the words she had earlier memorized, demonstrating an extreme focus on form. The mature, fluent, practiced reader shows more rapid oscillations between form-focused and meaning-focused reading: she can rely on automatic processing of form and focus on meaning until she encounters an unfamiliar pharmaceutical term or a Russian surname, whereupon the processing of meaning is disrupted while the form is decoded.

Groups define the nature as well as the value of literacy in culturally specific ways as well. A full picture of literacy from a cultural

and historical perspective would require an analysis of the distribution of literacy skills, values, and uses across classes and genders as well as religious and social groups; it would require a discussion of the connections between professional, religious, and leisure practices and literacy as defined by those practices. Such a discussion would go far beyond the scope of this report, which focuses on reading and reading difficulties as defined by mainstream opinions in the United States, in particular by U.S. educational institutions at the end of the twentieth century. In that context, employability, citizenship, and participation in the culture require high levels of literacy achievement.

Nature of the Evidence

Our review and summary of the literature are framed by some very basic principles of evidence evaluation. These principles derive from our commitment to the scientific method, which we view not as a strict set of rules but instead as a broad framework defined by some general guidelines. Some of the most important are that (1) science aims for knowledge that is publicly verifiable, (2) science seeks testable theories—not unquestioned edicts, (3) science employs methods of systematic empiricism (see Box 1-2). Science renders knowledge public by such procedures as peer review and such mechanisms as systematic replication (see Box 1-3). Testable theories are those that are potentially falsifiable—that is, defined in such a way that empirical evidence inconsistent with them can in principle be accumulated. It is the willingness to give up or alter a theory in the face of evidence that is one of the most central defining features of the scientific method. All of the conclusions reached in this report

are provisional in this important sense: they have empirical consequences that, if proven incorrect, should lead to their alteration.

The methods of systematic empiricism employed in the study of reading difficulties are many and varied. They include case studies, correlational studies, experimental studies, narrative analyses, quasi-experimental studies, interviews and surveys, epidemiological studies, ethnographies, and many others. It is important to understand how the results from studies employing these methods have been used in synthesizing the conclusions of this report.

First, we have utilized the principle of converging evidence. Scientists and those who apply scientific knowledge must often make a judgment about where the preponderance of evidence points. When this is the case, the principle of converging evidence is an important tool, both for evaluating the state of the research evidence and also for deciding how future experiments should be designed. Most areas of science contain competing theories. The extent to which one particular theory can be viewed as uniquely supported by a particular study depends on the extent to which other competing explanations have been ruled out. A particular experimental result is never equally relevant to all competing theoretical explanations. A given experiment may be a very strong test of one or two alternative theories but a weak test of others. Thus, research is highly convergent when a series of experiments consistently support a given theory while collectively eliminating the most important competing explanations. Although no single experiment can rule out all alternative explanations, taken collectively, a series of partially diagnostic studies can

lead to a strong conclusion if the data converge. This aspect of the convergence principle implies that we should expect to see many different methods employed in all areas of educational research. A relative balance among the methodologies used to arrive at a given conclusion is desirable because the various classes of research techniques have different strengths and weaknesses.

Another important context for understanding the present synthesis of research is provided by the concept of synergism between descriptive and hypothesis-testing research methods. Research on a particular problem often proceeds from more exploratory methods (ones unlikely to yield a causal explanation) to methods that allow stronger causal inferences. For example, interest in a particular hypothesis may originally stem from a case study of an unusually successful teacher. Alternately, correlational studies may suggest hypotheses about the characteristics of teachers who are successful. Subsequently, researchers may attempt experiments in which variables identified in the case study or correlation are manipulated in order to isolate a causal relationship. These are common progressions in areas of research in which developing causal models of a phenomenon is the paramount goal. They reflect the basic principle of experimental design that the more a study controls extraneous variables the stronger is the causal inference. A true experiment in controlling all extraneous variables is thus the strongest inferential tool.

Qualitative methods, including case studies of individual learners or teachers, classroom ethnographies, collections of introspective interview data, and so on, are also valuable in producing complementary data when carrying out correlational or experimental studies. Teaching and learning are complex phenomena that can be enhanced or impeded by many factors. Experimental manipulation in the teaching/learning context typically is less ''complete" than in other contexts; in medical research, for example, treatments can be delivered through injections or pills, such that neither the patient nor the clinician knows who gets which treatment, and in ways that do not require that the clinician be specifically skilled in or committed to the success of a particular treatment.

Educational treatments are often delivered by teachers who may enhance or undermine the difference between treatments and controls; thus, having qualitative data on the authenticity of treatment and on the attitudes of the teachers involved is indispensable. Delivering effective instruction occurs in the context of many other factors—the student-teacher relationship, the teacher's capability at maintaining order, the expectations of the students and their parents—that can neither be ignored nor controlled. Accordingly, data about them must be made available. In addition, since even programs that are documented to be effective will be impossible to implement on a wider scale if teachers dislike them, data on teacher beliefs and attitudes will be useful after demonstration of treatment effects as well (see discussion below of external validity).

Furthermore, the notion of a comparison between a treatment group and an untreated control is often a myth when dealing with social treatments. Families who are assigned not to receive some intervention for their children (e.g., Head Start placement, one-on-one tutoring) often seek out alternatives for themselves that approximate or improve on the treatment features. Understanding the dynamic by which they do so, through collecting observational and interview data, can prevent misguided conclusions from studies designed as experiments. Thus, although experimental studies represent the most powerful design for drawing causal inferences, their limitations must be recognized.

Another important distinction in research on reading is that between retrospective and prospective studies. On one hand, retrospective studies start from observed cases of reading difficulties and attempt to generate explanations for the problem. Such studies may involve a comparison group of normal readers, but of course inference from the finding of differences between two groups, one of whom has already developed reading difficulties and one of whom has not, can never be very strong. Studies that involve matching children with reading problems to others at the same level of reading skill (rather than to age mates) address some of these problems but at the cost of introducing other sources of difficulty—comparing two groups of different ages, with different school histories, and different levels of perceived success in school.

Prospective studies, on the other hand, are quite expensive and time consuming, particularly if they include enough participants to ensure a sizable group of children with reading difficulties. They do, however, enable the researcher to trace developmental pathways for participants who are not systematically different from one another at recruitment and thus to draw stronger conclusions about the likely directionality of cause-effect relationships.

As part of the methodological context for this report, we wish to address explicitly a misconception that some readers may have derived from our emphasis on the logic of an experiment as the most powerful justification for a causal conclusion. By such an emphasis, we do not mean to imply that only studies employing true experimental logic are to be used in drawing conclusions. To the contrary, as mentioned previously in our discussion of converging evidence, the results from many different types of investigations are usually weighed to derive a general conclusion, and the basis for the conclusion rests on the convergence observed from the variety of methods used. This is particularly true in the domains of classroom and curriculum research.

For example, it is often (but not always) the case that experimental investigations are high in internal validity but limited in external validity, whereas correlational studies are often high in external validity but low in internal validity. Internal validity concerns whether we can infer a causal effect for a particular variable. The more a study approximates the logic of a true experiment (i.e., includes manipulation, control, and randomization), the more we can make a strong causal inference. The internal validity of qualitative research studies depends, of course, on their capacity to reflect reality adequately and accurately. Procedures for ensuring adequacy of qualitative data include triangulation (comparison of findings from different research perspectives), cross-case analyses, negative case analysis, and so forth. Just as for quantitative studies, our review of qualitative studies has been selective and our conclusions took into account the methodological rigor of each study within its own paradigm.

External validity concerns the generalizability of the conclusion to the population and setting of interest. Internal validity and exter-