GAMSAT ® Courses

- UCAT ® Courses

GAMSAT ® OVERVIEW

- GAMSAT ® 2024

- What is GAMSAT ®

- GAMSAT ® Results Guide 2023

MEDICAL SCHOOLS

- Australian Medical Schools Overview

- Medical School Entry Requirements

- Pathways to Medicine

- Guide to Medicine Multiple Mini Interviews (MMIs)

GAMSAT ® Tips

- How to study for the GAMSAT ®

- GAMSAT ® Section 1 Prep

- GAMSAT ® Section 2 Prep

- GAMSAT ® Section 3 Prep

- GAMSAT ® Biology

- GAMSAT ® Chemistry

- GAMSAT ® Physics

- GAMSAT ® Preparation for a Non-Science Background

GAMSAT ® Resources

- Free GAMSAT ® Resources

GAMSAT ® Free Trial

- Free GAMSAT ® Practice Test

- GAMSAT ® Quote Generator

- GAMSAT ® Practice Questions

- GAMSAT ® Example Essays

- GAMSAT ® Study Syllabus

- GAMSAT ® Physics Formula Sheet

- GradReady GAMSAT ® Podcast

GAMSAT ® COURSES

- GET IN TOUCH

- GRADREADY PARTNERS

- Get In Touch

- GradReady Partners

Struggling with how to write the perfect GAMSAT Essay? Check out our free GAMSAT Example Essays with tips and corrections to master your preparation for the GAMSAT Section 2 Essays

GAMSAT® Courses are Now Open for Sept 2024 & Mar 2025 | Get access to our materials until March 2025!

Free GAMSAT Example Essays

12 min read

Read 134837 times

Writing GAMSAT ® practice essays is the most important aspect of preparing for Section 2 of the GAMSAT ® Exam. Regularly writing essays allows you to develop and practise your essay writing skills and is something you should aim to start from early on. It’s important to get into a routine: Whether you aim to type an essay once a week or once a day, every bit counts.

Writing regularly also helps develop your confidence, and prevents having that ‘writer’s block’ moment in the exam.

We’ve prepared a handy GAMSAT ® Essay Writing Guide you can download which includes all the information on this page, as well as some extra tips, some example essays to help you get a head start on your preparation for Section 2 of the GAMSAT ® Exam. Start preparing today!

- GAMSAT ® Essay Writing Tips

- GAMSATE ® Essay Qualities

- GAMSAT ® Essay Writing Guide

- GAMSAT ® Section 2 Essay Topics

- GAMSAT ® Section 2 Example Essays

- Further Free GAMSAT ® Preparation Materials

1178 downloads

Want more tips on how to ace GAMSAT ® Section 2 after reviewing our GAMSAT ® example essays? Our expert tutors, Nick and Caroline, provide further tips to help improve your essay writing skills in this Free GAMSAT ® Example Essays video guide.

GAMSAT Essay Writing Tips

Simply writing GAMSAT ® essays is not enough - It needs to be done in a structured fashion to ensure that you get the most out of your preparation. We recommend that you:

- Get feedback on your essays. It is vital that you get your friends, family, tutors and anyone else to read these essays - ask them to provide criticism and suggestions.

- Critique your own essays. After every essay you write, read it aloud to yourself and listen to see if it makes sense. Try to mark your own essays -use the list below as a useful guide

- Start gently. Don’t feel the need to write under time pressure from the word go. It’s more important that you develop and improve your essay writing skills before gradually applying realistic time pressure.

- Type your practice essays. It’s important that you get accustomed to typing your responses. There is no spell-check function in the GAMSAT ® exam , so practise typing responses into word processors without spelling and grammar corrections. You may also need to work on your typing speed. You will still be able to use provided sheets of paper for planning and brainstorming if necessary.

- Vary the type of essays that you write. You should make sure you try argumentative, personal reflective essays, fictional creative essays , poetry, and any other medium that can work in the GAMSAT ® exam. The GAMSAT ® exam can throw up unexpected prompts that might be difficult to write in a particular style: it’s important to give yourself the flexibility to deal with anything the exam might throw at you.

You can find more detailed GAMSAT ® Section 2 Essay Writing Tips and a Section 2 Reading List on our guide here: How to Prepare for GAMSAT ® Section 2.

Make sure you also sign up for our GAMSAT ® Free Trial to get a wealth of other free GAMSAT ® Resources including a recording of our GAMSAT ® Essay Writing Webinar:

Start Your GAMSAT ® Preparation Today!

Get a study buddy, upcoming events, gamsat essay qualities.

A strong GAMSAT ® essay, no matter what structure you choose, should:

- Be strongly related to the theme of the prompts. The GAMSAT ® is a test of reasoning skills: Your markers want to see how you think. In order to assess this, they need to see how you have thought about the prompts provided. GAMSAT ® essays that are unrelated give the impression of being ‘pre-written’, and are penalised quite heavily.

- Be well-written and well-structured. Sentences should be clear and concise. Paragraphs should only contain one main idea. Introductions and conclusions should summarise the essay, and not include any information that you do not analyse in your body paragraphs.

- Be interesting and original. Rather than simply arguing that the theme of the prompts is ‘good’ or ‘bad’, try to come up with something more specific. For example, for a set of prompts about research, rather than arguing that ‘research is good for the development of society’, you could take a more specific approach and argue that ‘research is a male-dominated field that suppresses female voices’.

- Include detailed critical analysis. Again, your writers want to see how you think, not ‘what you know’. This means pulling your examples apart in great detail. Ask yourself questions, and answer them in your response. What were the motivations behind it? Was there a driving ideology? What were the consequences? What does this show about human society?

GAMSAT Essay Writing Guide

How do you start writing a gamsat essay.

- Understand the Theme: Read the quote, identify the main theme, and any other related ideas. Your response needs to engage strongly with this - otherwise your markers cannot reward you.

- Brainstorm Ideas: Build a bank of ideas. Look over many essay prompts, and try to come up with three supporting examples that could be used for the theme. If you can’t think of any, do some research - current affairs, history, literature - anything that is relevant.

- Create a Thesis: What is your opinion on the theme? Make it clear, concise, and easy to understand.

- Choose a Structure: Consider what is most appropriate for the theme and explore your options. You might choose an argumentative response with concrete supporting examples, a more reflective response drawing on your own experience, or a fictional response that allows you to explore emotions and psychology.

- Plan Body Paragraphs: Each body paragraph needs to support your thesis, and go into detailed critical analysis. Support your thesis by referring back to your central idea at the beginning and end of each paragraph, and throughout your analysis.

- Be Clear & Succinct: Write in logical and well-phrased sentences that can be easily understood by a marker who will be reading your essay at a fast pace. Long sentences are not necessarily sophisticated sentences. Think of the great speech-makers. They use concise language. Simple writing is often the most powerful.

- Review your Essay: Review what you have written and ensure it makes sense. Check for typos and errors of grammar and punctuation. You want to give your marker the best impression possible.

For a further breakdown and more tips visit our guide: How to Prepare for GAMSAT ® Section 2.

Is GAMSAT Section 2 written or typed?

After the trial of a digital platform for the March and September GAMSAT ® in 2020, ACER decided that all future exams will be conducted digitally. Thus, GAMSAT ® Section 2 is typed, not written. Note that this change has not impacted the total allocated time, and you will still have 65 minutes to complete the two pieces of writing. However, students are now permitted to write in the 5 minutes that were previously allocated solely for planning.

Many students will be used to completing practice essays by hand, and it is important to tailor your practice to the exam context as closely as possible. Note that on the digital interface of the GAMSAT ® exam, there will be no autocorrect function or ‘copy and paste’ functions. Thus, it is important that when practising, you disable the autocorrect feature as well as any automated correction functions of your writing software. Programs with a simple interface like Notepad (and similar alternatives available online) are recommended.

How long are the essays in GAMSAT?

Another consideration with regards to Section 2 preparation is the paragraph/word count you are expected to reach. 400-600 words per essay has typically been used as a rough estimate of what students should aim to achieve under the previous handwritten condition. In contrast, a reasonably fast typers will be able to reach up to 1000 words in a 30-minute essay. Whilst the emphasis should still be on the quality of your writing and ideas, it is still important to keep in mind that you should be aiming for a longer essay than you would under handwritten conditions.

How to Practice for GAMSAT Essay Writing

- Get into the practice of typing. Whilst many students may be used to texting or typing out their assignments, typing under time pressure is a different skill altogether. The last thing you want is for your typing speed to limit the amount of content you can produce in the exam. Typing your essays under timed conditions will be the best practice in this regard.

- Make effective use of planning time. It is much easier to write-out and edit your plan on the digital interface. Whilst you’re now permitted to write during the 5-minute planning time at the start, it is advised that you use this time to plan out your essays and perhaps even write out your topic sentences to keep you on track during the writing process.

- Practice editing. As with planning, editing essays is much easier on a digital interface than in handwritten conditions. Nonetheless, it is important not to spend large chunks of writing time editing an incomplete essay. It is preferable that you aim to complete your essays a few minutes before the writing time ends so that you have time to edit. When editing, look for simple grammatical mistakes as well as changes to words and sentence structure that can increase the depth and clarity of your ideas. It is also a good idea to assess the flow of your essay, and integrate connecting words (thus, however, therefore, furthermore, etc.) to link your ideas and more clearly explicate the relationship between them.

For more information, check out our GAMSAT ® to Med School Podcast episode which specifically covers GAMSAT ® Section 2 advice and best practices.

GAMSAT Essay Structure

ACER does not provide any guidelines in regards to an essay structure, minimum word count, or how long your GAMSAT ® Section 2 essays should be. However, a maxim that holds true even for the GAMSAT ® Exam is 'quality over quantity'.

The quality of what you write is much more important than the quantity and as such, you should focus on what you write about and your expression and organisation of ideas. A basic guideline to your GAMSAT ® Essay Structure is:

- An Introduction

- 3 Body Paragraphs

- A Conclusion

Note however that this example structure is not necessarily applicable to every type of essay. If you were to write a creative piece, the structure of your GAMSAT ® Essay could certainly be more flexible. The main factor to take into account is how to best organise your ideas to ensure that your arguments are conveyed logically and coherently.You can practise using our Free GAMSAT ® Quote Generator which has over 90 Section 2 essay prompts, covering 40+ themes.

How many words should a GAMSAT essay be?

As mentioned above, a common piece of advice is to aim for about 400-600 words, but the most important point is to focus on the quality of your essay rather than the quantity. If you can express an idea clearly and effectively in fewer words then do it.

For tips on Section 2 of the GAMSAT ® exam, our study guide contains a 14 pg Section 2 Essay Writing Guide. Sign up here: GAMSAT ® Free Trial

For general tips and strategies on how you can prepare for the GAMSAT ® Exam, visit our Guide to GAMSAT ® Preparation.

How do you choose a GAMSAT essay style?

There are many GAMSAT ® essay styles to try, and each have their own advantages, disadvantages, and challenges. The list below is by no means exhaustive but may help provide you with some ideas and styles to trial. You should aim to test different styles and work out what works for you best.

Argumentative Essays

- Personal Reflective Essays

- Short Stories

These GAMSAT ® essays follow a basic structure, using an introduction, 2-3 body paragraphs, and a conclusion. You will take a strong central opinion, and introduce it in your introduction. Each body paragraph should contain one supporting example, and detailed critical analysis, in order to defend your argument. These essays:

- Are usually students’ preferred option.

- Allow you to analyse political and social themes very effectively.

- Require a good breadth of knowledge in order to provide three supporting examples.

- Follow a set structure or formula, and can therefore be easier to get the hang of if you are not as comfortable writing.

- However, argumentative essays can be difficult if the prompts are about something very personal or introspective, for example, ‘love’.

- They can also make it more difficult to be interesting and original in your response.

Personal reflective essays

These GAMSAT ® essays allow you to demonstrate your emotional intelligence, self-awareness, and empathy. These are vital qualities to demonstrate in the entrance exam for medical school. Try to avoid a hybrid of argumentative and personal styles: personal essays that take three short anecdotes and discuss them in an introduction/three body paragraphs/conclusion structure do not usually come across as sincere.

Taking one, strong personal experience that is related to the theme of the prompts, and analysing it in detail, is a great way to start. Show your marker what you felt and why you felt that way - demonstrate your emotional and psychological analytical skills. These essays:

- Are an excellent way of being interesting and original: your experience is your own.

- Make it easier to demonstrate emotional awareness - It is much easier to provide emotional insight into something with which you have personal experience.

- Can move your marker. Your marker is a human being! Giving them a personal response gives them a connection to you.

- Are the least challenging of the non-argumentative essays - most students like to start with these essays before branching into more creative writing.

- However, it can be difficult to write these essays if you have no experience related to the theme of the prompts. Collecting a ‘bank’ of personal experiences that can be used for various themes is a helpful way of knowing whether you can use a personal reflection for a set of prompts.

Short stories

Writing short stories is an excellent way of standing out. They allow you to show emotional and psychological insight, but without having the restraint of personal experience.

In a short story, try to stick within your own realm of experience. A short story does not have to be a Hollywood Blockbuster: often the simplest plots are those that are the most sincere, touching, and effective. Remember that the point of these essays is not to write a dramatic story. It is to demonstrate your social, emotional, or psychological reasoning skills to your marker. These essays:

- Require practice. Refine your writing style to be simple, sincere, and not far-fetched.

- Require creativity! Think of creative ways to describe emotions or situations. Avoid cliches in your descriptions.

- Should deal with one strong central idea that is related to the theme of the prompts.

- Can produce outstanding marks. Well-written and thoughtful short stories allow you to demonstrate the sophistication of your expression, your originality, and your analytical skills.

GAMSAT Section 2 Essay Topics

Section 2 of the GAMSAT ® Essay consists of two different essays (usually called Task A and Task B), each in response to their own set of stimuli. These prompts are presented as a set of quotes (usually 5), with each set centred around a common theme.

GAMSAT Section 2 Task A Themes:

Gamsat section 2 task b themes:.

- Originality

GAMSAT Section 2 Questions

Theme: truth.

- Gossip, as usual, was one-third right and two-thirds wrong. (L.M. Montgomery, Chronicles of Avonlea)

- The truth is rarely pure and never simple. (Oscar Wilde, The Importance of Being Earnest)

- Truth is a matter of the imagination. (Ursula K. Le Guin, The Left Hand of Darkness)

- You don't destroy what you want to acquire in the future. (Suzanne Collins, Mockingjay)

- To be fully seen by somebody, then, and be loved anyhow - this is a human offering that can border on miraculous. (Elizabeth Gilbert, Committed: A Skeptic Makes Peace with Marriage)

Theme: Justice

- Being good is easy, what is difficult is being just. (Victor Hugo)

- I don't want tea, I want justice! (Ally Carter, Uncommon Criminals)

- It is better to risk saving a guilty person than to condemn an innocent one. (Voltaire, Zadig)

- Right is right, even if everyone is against it, and wrong is wrong, even if everyone is for it. (William Penn)

- Keep your language. Love its sounds, its modulation, its rhythm. But try to march together with men of different languages, remote from your own, who wish like you for a more just and human world. (Hélder Câmara, Spiral Of Violence)

You can find further essay topics using this free GAMSAT ® Section 2 Essay Quote Generator:

GAMSAT Section 2 Example Essays

Even with all of the above tips and topics, it can be difficult to start writing without an idea of what a GAMSAT ® Essay should look like. That’s why we’ve decided to provide an example essay below with feedback provided by our tutors to help you make a start on your preparation for Section 2 of the GAMSAT ® Exam.

GAMSAT Section 2 Task A Example Essay

Task a example essay question.

- Don’t forget your great guns, which are the most respectable argument for the rights of kings. (Frederick the Great)

- The people are that part of the state that does not know what it wants. (G W F Hegel)

- Those who cast the votes decide nothing. Those who count the votes decide everything. (Joseph Stalin)

- Win or lose, we go shopping after the election. (Imelda Marcos)

- Democracy is the worst form of government except for all those other forms which have been tried from time to time. (Winston Churchill)

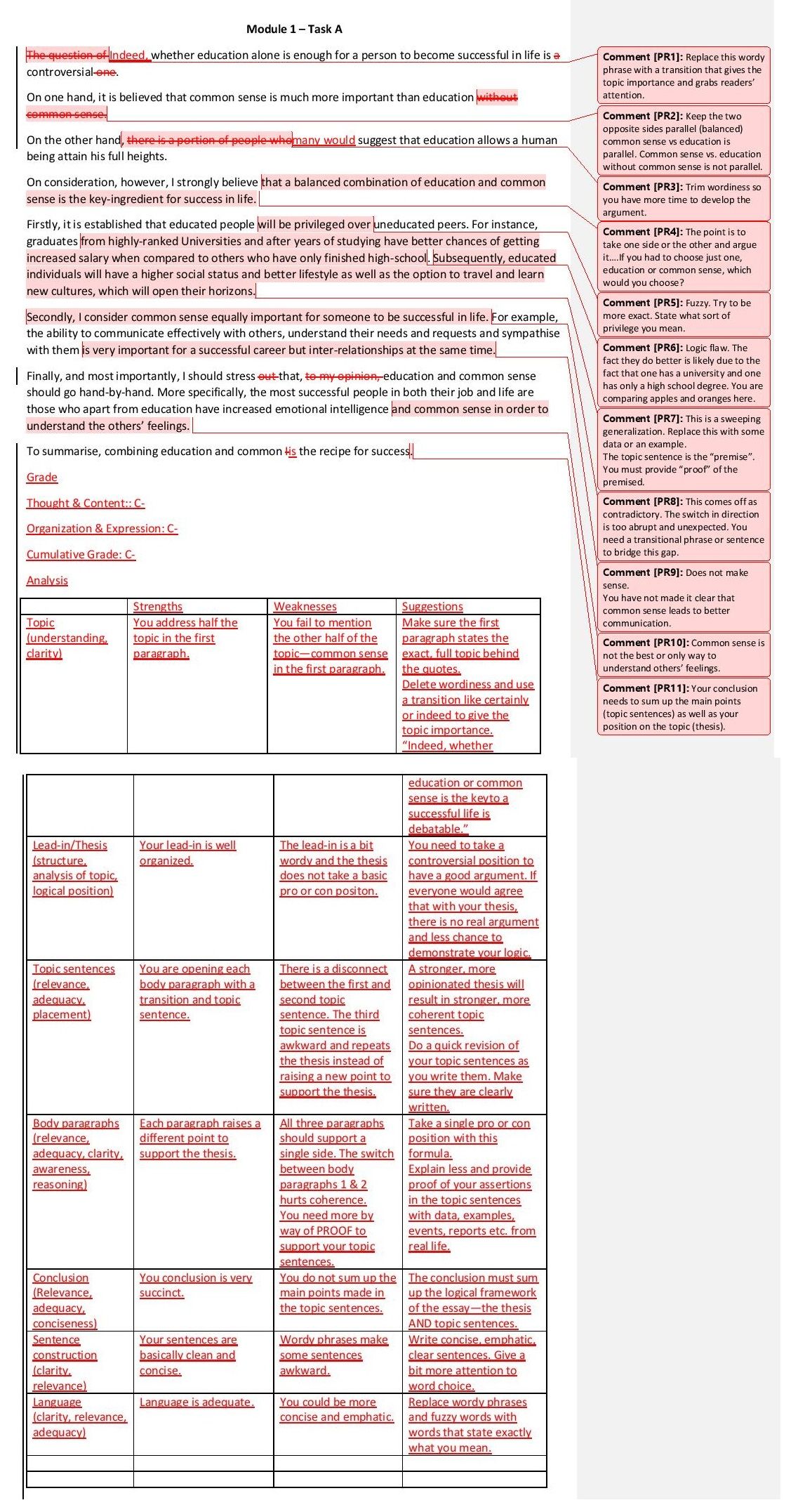

Task A Example Essay: Medium Standard Essay

- The people are lead to believe that their votes decide the power, however the real power resides with those who count the votes. Whether the power is attained by corruption or manipulation, the people have little say even what they try to stage a backlash. Examples of corruption aren’t hard to find, but the frustrating case of Robert Mugabe is a strong example. Constant broken pre-election promises try to manipulate the people even at a staged constituency. Time and again tyrants pop up to demonstrate clearly how compromised the electoral process can sometimes become.

- The strings of bad decisions made by Robert Mugabe have devastated Zimbabwe, whilst somehow benefiting him and his family. In 200 President Mugabe enacted the removal of white ownership of farmland. His plan was to give the land to the native Zimbabwean’s to make them more successful and therefor give them more of the power. This was an important promise and made him very popular with his countrymen. During the crossover period, Mugabe’s family ended up with 39 farms, with the rest going to un-experienced Zimbabweans. The result was a complete slump in food production and in return a failing economy for Zimbabwe, forcing them to abandon their currency in 2009. Ironically the white farmers had been very effective in their farming and had bolstered the economy. In the 2010 election, despite being generally despised by many Zimbabweans, Robert Mugabe won another term by a giant 60% of the votes. It seems unlikely he would win reelection given the circumstances. Corruption among the voting officials who were under the control of Mugabe is suspected but few are willing to question his authority.

- It’s partially expected by citizens of democratic countries that pre-election promises are seldom kept. However when a candidate is making promises that would highly benefit you and your community, it’s hard not to jump on their bandwagon. In the 2013 election, the Labor party promised millions to rural communities to fund different community projects which would have provided stimulation for their economy. However since winning the election and releasing the budget, those promises have been revoked in order to cut costs. Resulting in thousands of rural citizens feeling manipulated by false promises made by the Labor party.

- Most recently in WA, an alleged 1800 people have voted multiple times at different polling stations in the 2013 election. Before this, thousands of votes had believed to have simply vanished so a new election was to be held, but in light of this new information an additional investigation is being held. This is an example of the people trying to take back the power. Although it is illegal, most would not consider it to be any less morally wrong than corruption or manipulation especially on a huge scales such as the examples of Robert Mugabe and the Labor party. Voting is only a human invention, and it can be easily manipulated just like any other human invention.

- Tactics of politics are harsh. With emotional and physical tries to power, its not a surprise that votes feel the need to use the same tactics in order to win back the power. Examples can be found all over the globe with Zimbabwe and Australia just scratching the surface. In the words of Joseph Stalin – “Those who cast the votes deiced nothing. Those who count the votes decide everything.”

Task A Example Essay Correction and Feedback

- This is a well-written essay and appears to make a sound argument by incorporating some well-informed examples.

- There is no major flaw with the written expression in this essay. While sentences in some cases can be shortened and written in a more direct manner, this is not a major criticism of the essay. There are, however, multiple small errors: ‘people are lead to believe’ should be ‘people are led to believe’; ‘the people have little say even what they try to stage a backlash’ should be ‘the people have little say even when they try to stage a backlash’, amongst others. Whilst these are small details, it’s important to give your marker a strong impression of the quality of your written expression.

- The structure of the essay also follows the basic argumentative essay structure. One of the main issues that prevents this essay from receiving a higher mark is that the quote that the writer has selected is not compatible with the second example that they have provided. This example talks about a political party changing its tune after an election. It is not clear how it furthers the argument that the electoral process itself is compromised in some way. In argumentative essays, every supporting example should be defending and strengthening the thesis. Irrelevant examples and analysis is very difficult for a marker to reward. In fact, they can actually weaken, rather than strengthen, an argument, as they distract the reader from the central idea.

- The content of this essay appears informed. The writer, however, has made a crucial mistake in saying that the Labour party won the 2013 election. It was the Liberal party. If this mistake were made once in the text it could be dismissed as a typographical error under the time pressure; however, it is repeated.

- This essay could also go to a more sophisticated level of critical analysis. The details of the examples could be teased out to further support the central example. For example, in the third body paragraph, what are the consequences of these votes being ‘lost’? Democracy is being compromised and people’s votes are being silenced: imagine living in a country where voting is compulsory, yet your vote is not counted. Is this a betrayal of the people? How is it an example of the people trying to take back power? Perhaps because they are demanding accountability from their democratic government. Is this, in itself, promising? Namely, whilst voting is open to corruption, in a true democracy, the people have a right to freedom of speech and to transparency of government. Does the true spirit of democracy, then, help to defeat the possible corruption of the voting process?

- Going into this level of detail would demonstrate stronger reasoning skills. Markers want to see how a candidate thinks, and how deeply they think - not simply ‘what they know’.

- This essay is quite good, and it has chosen a challenging argument to present. However, it can be improved by a better selection of content that goes directly to the argument that the writer is trying to make.

GAMSAT Section 2 Task B Example Essay

Task b example essay question.

- Creativity is the defeat of habit by originality. (Arthur Koestler)

- Create like a god; command like a king; work like a slave. (Constantin Brancusi)

- Truth and reality in art do not arise until you no longer understand what you are doing. (Henri Matisse)

- You are lost the instant you know what the result will be. (Juan Gris)

- An essential aspect of creativity is not being afraid to fail. (Edwin Land)

Task B Example Essay - High Standard Essay

- Creation is a power no mortal man should be gifted with. And it’s exactly that. A gift. It can give rise to ugly life forms capable of destruction yet it can also wondrously design and improve our small insignificant lives. A gift not bestowed upon me and perhaps for good reason.

- The power of creation is given to those who sit on the outskirts of our society, like outcasts and the insane. These poor souls, if poor is the best fitting word, let their minds wander aimlessly and ironically discover and churn out fantastical and absurd ideas. How blissful.

- Desperation summons creative too. When we are pushed to the extremes and our normal ways fail, new ideas spawn almost spontaneously. When there is no other option but to be creative, we find ourselves stumble upon the new and the amazing.

- Regardless, there is a very good reason being creative is not easy. It's not for everyone. Chaos would conspire. Creativity is power. Power corrupts the mind. Corruption is fatal. But just for a minute, let's indulge and pretend we possessed the power of creation. What to do? What should I create? I would not create equality amongst equality amongst race or world peace or a cure for aids. That’s not out of the hexagon enough for me. It's not that I do not support world peace or todays real issues, but someone with a smaller capacity for creation can do that. A child. A dying war veteran. I’m going to create something unfathomable. It's my duty, my unspoken agreement to create something for more unimaginable. Good or evil? Black or white? The answers to these questions are never easy.

- Who knows. Let drugs and hallucinogens do their work there. Because I can’t create anything of such a nature. I’m skin and bone. Not god. Not even a demi-god. I’m not burdened by the gift of creation. But god knows someone is. What a frustration to wait for the day they realize, what a terror to see what follows.

Task B Example Essay Correction and Feedback

- This essay is challenging and different. The written expression in this essay, whilst simple, is powerful. It can be read as a form of dramatic monologue and the writer has carefully selected each word and sentence length to ensure that the essay is read in a dramatic tone. It resembles speeches by accomplished orators: simple and moving. The purpose of many essays is to convince the reader. It is much easier to convince someone if they can understand it; even easier to convince someone if they are moved by it.

- The structure of this essay is almost similar to a free verse poem in that there is no real structure; however, there is cohesion between paragraphs. The writer’s ideas on the issue are easy to follow.

- This essay is considered a high standard mainly because of the content and the original perspective on the theme. The writer reflects upon what creativity is, but in a way that is not often executed by students under strict exam conditions.

- Each paragraph of the essay covers a different twist on what creativity means. It challenges the reader to consider the writer’s opinions and stands out from other essays. Also note that although this essay is a high standard response, the length of the response is much shorter than the other examples. This is a good demonstration of how quality is more important than quantity.

- As with every essay, however, there are aspects that could be improved.

- There are simple errors throughout: these detract from the writer’s otherwise powerful and strong sense of voice.

- One other important way in which this essay could improve would be to have a stronger central idea. The essay clearly focussed on creativity, and different interpretations of it. However, unifying the essay behind one perspective, such as the danger of creativity, could make this response more effective.

Make sure to also sign up to our GAMSAT ® Free Trial to watch a recording of our GAMSAT ® Essay Writing Workshop! Check out the 10 minute excerpt below:

Further Free GAMSAT Preparation Materials

Free gamsat preparation materials.

The most comprehensive library of free GAMSAT Preparation materials available.

Understanding your GAMSAT ® Results

Covers everything you need to know about your GAMSAT ® Results - How the scoring works, result release dates and even GAMSAT ® score cutoffs.

How to study for the GAMSAT ® Exam

A breakdown of how to approach study effectively and how to set up a GAMSAT ® study schedule

How to prepare for GAMSAT ® Section 1

An overview of what to expect in Section 1 of the GAMSAT ® Exam, how to prepare.

How to prepare for GAMSAT ® Section 2

An overview of what to expect in Section 2 of the GAMSAT ® Exam, how to prepare and how to perfect your essay technique.

How to prepare for GAMSAT ® Section 3

An overview of what to expect in Section 3 of the GAMSAT ® Exam and how to prepare for each of the topics - Biology, Chemistry, & Physics.

GradReady GAMSAT Preparation Courses

To learn more about our GAMSAT ® Preparation courses and compare their different components, view an in depth comparison here: GradReady Course Comparison

If you’re not sure which course is best for you, try our Course Recommender.

If you’re after a single feature, such as our Textbook, or access to our 4000+ Intelligent MCQ Bank, or if you want to customise your preparation, you can do so here: GradReady GAMSAT ® Custom Course.

At GradReady, we pride ourselves on providing students with the Best Results at the Best Value:

- Our team is consistently reinvesting in our internal operational technology to ensure that we're constantly improving our efficiency and productivity. The end result for our students is that we stand head and shoulders above our competition in the comprehensiveness of the tools we offer and the effectiveness of our teachings – all at the best value .

- We believe in a data-driven approach: using student performance data to fine tune our practice questions, study content and teaching styles has allowed us to achieve unparalleled results for our students.

- We are the only provider with Statistically Significant Proven Results – our students achieved an average improvement of 20+ Percentile Points, 10+ years in a row, with an average improvement of 25 Percentile Points for the May 2020 GAMSAT ® exam.

- We achieve these results through our interactive teaching style and adaptive online learning technologies. Our classes are capped at 21 students, and taught by a specialist tutor for each subject, tutors who are themselves Medical Students who have sat the GAMSAT ® .

- Our online systems make learning into a science and we are the only provider with a proprietary online system that uses algorithmic-assisted, targeted learning. Unlike other providers who purchase a 3rd Party System, the targeted system that we've developed tracks your performance, quickly identifying your weaknesses and pointing you to the most relevant materials and even tutor assistance.

To learn more about our courses and compare us to the competition, visit: GradReady GAMSAT ® Preparation Courses

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy Policy

General & Course Queries: (03) 9819 6696 10am - 5pm Melb Time

GAMSAT Queries: (03) 9885 0809 10am - 5pm Melb Time

Copyright © GradReady Pty. Ltd. All rights reserved

GradReady is not in any way affiliated with ACER, nor are any materials produced or services offered by it relating to the GAMSAT ® test endorsed or approved by ACER.

Got a Question?

Would you like to consult our faqs first, september 2024 gamsat® courses are now open enrol now for access up until march 2025.

Enrolments for our 15-Day Attendance Courses & Industry-Leading Online Courses are now open for the Sept 2024 and March 2025 GAMSAT® Exam! Enrol now to get access to our comprehensive GAMSAT® preparation materials until March 2025 ! Get access to 4000+ MCQs in our question bank, 12 GAMSAT® Practice Tests which mimic the official ACER GAMSAT® exam in detail, weekly 1-hour session with our experienced tutors from June, and one additional round of Virtual PBLs of your choosing free of charge . For instance, if you enrol for the August Course, you can choose to attend again in January. You can also subscribe to our GAMSAT® Courses and get the flexibility to cancel anytime! Early subscribers enjoy lower monthly fees; prices for new enrolments increase as we approach the GAMSAT® exam. The prices are at their lowest now! Join 10,000+ GradReady Students who have improved their scores by 20+ Percentile Points on average, 10+ Years in a Row!

GAMSAT Section 2 Essay Examples

GAMSAT Section 2: Five Example Essays Ranging From Scores Of 50 To 80+

In order to perform well in Section 2 , it is important to understand the key features of a high scoring GAMSAT essay. When reviewing previous GAMSAT essay topics , you should know the main marking criteria to address.

This guide contains worked examples of GAMSAT essays to help you identify the major metrics looked for by Section 2 tutors and markers, using pieces discussing healthcare as examples. You can use the pertinent principles in this guide to create a stringent GAMSAT essay plan to maximise your performance in Section 2 .

Inside the Section 2 Sample Essay Guide

- Sample Essays spanning scores from the low 50s to 80+

- Highlighted flaws in each essay to aid in self-assessment

- In-depth analysis and feedback from top tutors

Example Paragraph From An 80+ GAMSAT Essay

“In the current polito-economic landscape of most nation-states, health and healthcare are contentious issues. It is this very discourse that leads me to both types of research the realities and explores my own values and beliefs in relation to the notion of health. This surveying of my mental landscape led me to one unwavering belief: “healthcare is not a privilege, it is a right.” When this statement became core to the way I understand the human condition, I started to question if the societies I live in have come to embody the opposite of this belief in practice.

This line of questioning led me to understand one of the most fundamental mechanisms in the way modern societies function. This mechanism is the domineering politico-economic ideology. Neoliberalism. Through observation, we can see it functions to commodify most aspects of the human experience and does so very drastically in the case of healthcare.”

The Quotes Covered Are:

Health is not valued till sickness comes.

Take care of the patient and everything else will follow.

Control healthcare and you control the people.

Wherever the art of medicine is loved, there is also a love of humanity.

If you found this useful, kindly look at our free GAMSAT preparation resources:

Related Articles

- Section 1: What to Expect & How to Study

- Section 2: How to Write High Scoring Essays

- Section 3: Tips & Strategy

- What is the GAMSAT?

Free Resources

- Free Online Course with +200 Topics

- GAMSAT Topic Book

- Online Practice Test

GAMSAT Section 1

- Section 1 Question Log

- Tips on GAMSAT Poetry

GAMSAT Section 2

- Quote Generator

Related posts

Read more articles from our team

GAMSAT Biology for Section 3

GAMSAT 2022 March: What Did it Look Like?

GAMSAT & GPA Average Score Cutoffs

Can You Wing The GAMSAT Exam?

GAMSAT English Tutor

Specialist S1 and S2 | Australia

GAMSAT Theme Talk: Politics

The first step in writing a GAMSAT Section 2 essay is identifying the theme associated with the quotes presented. This blog post will go through potential ideas and sample essay structures.

- 1 Brainstorm Arguments & Ideas

- 2.1 Sample 1

- 2.2 Sample 2

- 2.3 Sample 3

- 3 Resources to improve your ideas and writing

- 4 Need Help?

Brainstorm Arguments & Ideas

- Same sex marriage bill, on Dec 2017, the right to marry in Australia was no longer determined by sex or gender, postal vote.

- This can be considered the correct course of action – equality, supporting love regardless of gender

- Politics – make promises to get the popular vote, campaign promises made in good faith or do they hide more sinister intentions or cause division?

- E.g. Trump with the wall – pandering to right wing views? Create more divide in society

- Kevin Rudd, promised to apologise for the wrongs that had been done and towards the Stolen Generation. → instigate movement towards reparations, acceptance, belonging, closing the gap → potential to create real societal change

- Politics – manipulation, lies

- Removed from politics – direct, clear, unbiased, see the bigger picture → the common people are perhaps best to understand the issues that plague society, e.g. homelessness, poverty

- The true mark of a good government is able to listen and understand

- ‘Most removed’ – Trump in terms of understanding the common man’s demise, their problems and pandering to this….’best politician’ provide a solution

- ‘Most removed’ – Jacinda Ardern in terms of understanding the emotional state of the country

- Greta Thunberg – raising awareness of climate change, part of the grassroot initiating change, instigated multiple high school strikes across the world

- Compromise, gain support of other people

- E.g. Julia Gillard, allied herself with the Greens in order to gain leadership but had to introduce the Carbon tax

- E.g. vaccine rollout, state and national leaders working together

- 1917 Bolshevik revolution – Lenin/Trotsky to overthrow the Tsar (Soviet Union). In the aftermath of the 1917 Bolshevik revolution – Stalin learnt the art of compromise, use political rhetoric to oust Trotsky and gain leadership and the support of others → Five year plans disastrous for the economy, secret police, widespread poverty, famine

- Money = more resources, can get more involved

- Power can help to enact change, e.g. Martin Luther King, Nelson Mandela, Aung San Suu Kyi

- Power can corrupt, e.g. Macbeth

Possible Essay Structures

- E.g. Sam Dastyari and murky links with Chinese businessman, potential for foreign powers to influence politics or trade relations.

- E.g. Clive Palmer and use of money to support his political campaign, implies that only those with money can garner adequate support. –> https://theconversation.com/mineral-wealth-clive-palmer-and-the-corruption-of-australian-politics-117248

- E.g. Malaysia’s former Prime Minister Najib Razak being found guilty in the corruption trial over the multi-billion dollar 1MDB scandal. Consider the money that could have gone to the people, in supporting infrastructure, economic growth and improving welfare.

- In Australia, we have a separation of powers between the parliament, executive and judiciary

- In democratic countries, potential for lobby groups and protests to raise awareness about important issues

- Role of media in keeping people accountable, e.g. Tony Abbott and not wearing a mask (Sept 2021) subjected to same fines as others

- Donald Trump – building a Wall, replacing Obamacare, personality more important than promises of actual change. Trump recognises this and uses this to his advantage, appealing to minority/isolated/disenfranchised members of society by discrediting the media and their propagation of ‘fake news’. Give examples of what he have said and analyse.

- Kevin Rudd – promises to unify/eliminate barriers between Aboriginal Australians in modern society

- If we are to make positive change within our society we must hold those we elect into power accountable.

- Politics is often turned into a popularity contest rather than a campaign for what is beneficial for communities.

- This is further exacerbated by the use of money and power to further political agendas

- However, a truly successful politician is one who is able to compromise and understand the concerns of the common people.

Resources to improve your ideas and writing

Click here to buy Part A Idea Bank

Click here to buy a step-by-step study guide to mastering GAMSAT essay writing

Contact me here

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Discover more from gamsat english tutor.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Section II Quote Generator

Test yourself with the worlds largest GAMSAT quote generator. Randomly select from over 100 quote sets modelled on previously tested ACER topics.

Task Selection:

Press on the options below to practice upon GAMSAT-style prompts. Review your work to standards in line with our famous essay structure . Remember to practice under test conditions.

Timer (press to start)

Frequently Asked Questions

ask A usually revolves around geopolitical issues (war, democracy, crime) and Task B surrounding personal and social topics (friendship, trust, love). Yet, practicing a broad philosophical idea can be applicable to both.

When studying, try limiting yourself between 25-29 minutes per essay, this will give you some time to review your work. Remember, you can always come back to add in extra details if you have the time.

This number will vary between students. It is generally recommended that before sitting the GAMSAT, students will type up at least 4 essays under exam conditions. This will help students understanding timings and familiarise themselves with exam-style prompts.

Yes, we offer comprehensive essay guides and classes to help you improve your GAMSAT essay writing. Visit our products page under the 'Buy Now' tab.

- GAMSAT COURSES

- FREE GAMSAT RESOURCES

- LIKEMIKE AI

by Michael Sunderland

How to ACE GAMSAT Section 2 Quote Interpretation – Task A

0 Comments

December 20, 2020 in Free Chapters

How to ACE GAMSAT Section 2 Quote Interpretation

GAMSAT Section 2 writing is not normal essay writing. I’ve said this before, I’ll no doubt say it again. The origin of a 90+ Section 2 response is what is made from the task, or in other words how you approach quote interpretation. It’s very hard to write a poor response with quality, sophisticated ideas; and very hard to write a good response to simple, pedestrian, or reductive ideas.

I like to think of quote interpretation as the ceiling value of your writing. It sets the upper limit of what you can achieve. How you then deliver the thoughts you’ve had is the degree to which you capitalise on the potential you have created through your quote interpretation. In my experience, 95% of students turn that ceiling into a glass ceiling, and shoot themselves in the foot before they begin by approaching perhaps the most crucial element of the task in the most rushed, and pedestrian manner. This does not bode well for a high scoring response.

ACER’s words

Let’s begin first with ACER’s own words from the GAMSAT information booklet so we can be sure that I’m not pontificating about something I just made up. The underlining is my own, the rest is a direct quote.

“Written Communication is assessed on two criteria: the quality of the thinking about a topic and the control of language demonstrated in its development. Assessment focuses on the way in which ideas are integrated into a thoughtful response to the task. Control of language (grammatical structure and expression) is an integral component of a good piece of writing. However, it is only assessed insofar as it contributes to the overall effectiveness of the response to the task and not in isolation. “

There is an emphasis here on quality of thinking, and integration of ideas thoughtfully. That is, in part, to place the prompts in their broader cultural, psycho-social, politico-economic, or philosophical contexts; but also linearly and deliberately developing an argument or position (see my post The Ontology of Structure – Logic for more on this). Structure, language, and other things that traditionally are thought of as the foundations of a good essay are almost explicitly said here not to be assessed in isolation, and that they contribute only insofar as they contribute to the aforementioned criteria (quality of thinking). This is why traditional methods of approaching writing are only sufficient to get you to a 75. There seems to be a huge paucity of information and discussion about how to improve your quality of thinking, or how to telegraph an improved quality of thinking in a GAMSAT section 2 context.

ACER also explicitly says in their information book

“pre-prepared responses and responses that do not relate to the topic will receive a low score.”

Which, if this is what is being assessed, begs two questions..

1. How can I improve the quality of my thinking about the prompts 2. How can I be sure to be relevant to the topic

I come bearing gifts.

How not to approach quote interpretation

Let me first deal with what not to do. Almost everybody I come across conflates the prompts into a one word “theme.” They tell me, “oh the theme is conformity” (or “punishment”, or “government”, or “death”, or “space”, or “boredom” etc). This leads to simple and low level thinking responses which lack direct relevance; and therefore often score poorly. Here’s two reasons why.

It’s reductive

In the first instance you have reduced five incredibly complex, nuanced, sophisticated world views – which have arisen in many cases from 60+ years of expert experience and study, and if not, still from within a valid ontology and set of human experiences, thoughts, and ideas – into a simple world. You have reduced what could have a book, or hundreds of books in many cases, written about it to a word. It’s like thinking that the words “harry potter” is the same thing as everything that happens in those seven books (is it seven, idk?), plus the movies, plus the childhood experiences reading and interacting with those materials, plus the popular culture around it etc. There is a whole world behind it which is not conveyed in proper depth by its placeholder title.

And then, you’ve grabbed four other equally complex and nuanced and sophisticated world views, and conflated them – suggesting that they all more or less say the same thing when, in truth, this word does not adequately describe even one of the prompts, let alone all of them. And this is done simply based on the criteria that this word happened to have cropped up a number of times in the prompts. This is already to have made ten odd errors. Because it is to say that 1 is the same as 2, 3, 4, 5; and 2 is the same as 3, 4, 5 and so on.

Perhaps you’re thinking “no that’s not me,” and that you’re being really sophisticated because you contrast the ‘positive’ side of the theme, with the ‘negative’ side – which is still to have reduced a quote to one word: either ‘positive’ or ‘negative.’ Many of you will then flatly say that one of the prompts is false, or even relate to that view in a belittling manner suggesting it “is completely wrong” or “a ridiculous misinterpretation of the democratic foundations of modern life” (very fancy), and think you’re doing the right thing by arguing forcefully in an argumentative essay. I don’t blame or judge you, I’ve done the same thing. But what you’re really saying to the marker when you do that is that you, in a psychometric test on an unprepared topic, in thirty minutes, know better than someone who has dedicated their whole life to having that viewpoint. A major misstep.

Lastly you are then forced to generate a whole essay from a single word; rather than to focus highly nuanced and sophisticated ideas into a powerful single point (contention). It’s hard to write a bad essay from sophisticated ideas. And very hard to make a good essay from reductive or pedestrian ideas.

The reductive approach

single word theme < essay

A high scoring approach

Five highly complex ideas > focused in the introduction to a sharpened point (contention) > thrust forward and upward into the armor in Body Paragraph 1 > twisted in Body Paragraph 2 > graceful psychometric validation of the other sides and the contexts in which those truths arrive as you stand over the defeated opponent

It also lacks relevance

A reductive approach to quote interpretation often leads to writing that fails to “directly respond to one or more of the prompts” which is one of the only things ACER tell you explicitly that you are supposed to be doing.

This final error occurs not in the quote interpretation, but in the very next moment after it. Let us suppose you have thought to yourself “the theme is conformity.” You then think “hmm, what do I have to say about conformity.” You then come up with some idea and go off and write about it. Your writing will then be in the domain of conformity, but this will often lack relevance to conformity to begin with (as you’re under time pressure and writing whatever comes out); and furthermore, as we have established, ‘conformity’ wasn’t, in many cases, directly relevant to the prompts to begin with.

Ok, so what is the best way to approach quote interpretation?

What you make from the task, which essentially is what is being examined, arises from how you confront the ideas in front of you and situate them in their broader contexts.

I always recommend to re-write the five quotes in your own words. This takes some time, and needs to be practice, it’s also mentally draining. But the rest of the essay stems from this moment. In time you will be able to spot quotes that you think won’t lead to good outcomes, or may include traps you want to avoid, so you can save time by only re-writing/interpreting the quotes you eventually want to involve in your response. I wouldn’t recommend doing it in your head, it’s too hard to remember the other ones by the time you finish. But almost always when you see the five interpreted versions you can see links that weren’t evident before. I physically write 1 to 5 under every set of prompts. Towards the back end of my preparation I found time saving approaches, but to begin with it’s a good exercise.

Also, by “write them in your own words” I don’t mean repeat the exact thing the prompt says in different words. I mean to interpret what they are saying. Imagine a teacher said the prompt to one of your friends and then your friend turned to you after and said “that made no sense, what do they mean” and then you responded to explain it to your friend so they understood. That interpretation is what you need to be writing down. When you receive the real implications of what the quote is inviting you to consider, you will relate to the prompts very differently, and answer in a more embellished and insightful way. I will have a case study later in the chapter, so hold that thought for just a moment. First:

Do I respond to the one or all of the quotes; or do I interpret a theme and respond to that?

We’ve already discussed that reducing it to one word is not the thing to do. You are welcome to respond to complex, deeply, highly considered and thoughtfully interpreted theme if you think you are up to it. When I started I would interpret each quote, and then think to myself “if these five ideas were in a news article, what would the heading of that article be?” .. and it would often be something like “the relevance, function, and limitations of punishment in contemporary Western societies” or something to that effect. Now this was (is) high order thinking, however, it comes with some challenges.

This approach does lead to sophisticated responses, however the marker 9 times out of 10 won’t follow what you’re saying or the implied connection to the theme very easily. Because you are responding to something that took a great deal of thought, the marker can be left wondering which prompt you’re responding to. They won’t have engaged with it in the level of detail you have (or have interpreted the quotes in quite the same way), so it can lose points for relevance (even though it’s highly relevant). This circles back to earlier times when I’ve mentioned that it is crucial to be both generous to the marker, and aware of how you position yourself in their eyes (which I discussed in further detail here ).

So, I personally don’t recommend writing to a whole theme (either one word, or correctly interpreted) because it can fail to translate in a very generous, direct, and clear way. Or if you do write to the correctly interpreted theme, be prepared to be VERY explicit about what you’re saying, why you’re saying it, and how it relates to the theme (and how the theme you have interpreted relates to the prompts, and which one).

Regarding responding to all of the quotes. I’d encourage you guys to think of the five prompts as being facets of the same diamond. There is something that coheres them. Reality and truth is not absolute. All perspectives happen to tend toward, or converge from many directions on, an approximation of the truth. Knowing this is essential. The prompts are deliberately chosen for this reason. They look at issue from many directions. Early in my preparation, addressing each of these perspectives was essentially the essay written for me. I just made each point a paragraph (or lumped a couple together in one; and the others in another) etc. Again, fine, although I frustratingly had markers ask me “which prompt was this in response to?” which eventually annoyed me enough that I came to the final iteration of my prompt-addressing strategy.

I pick one prompt (or two if they happen to exist within the same ontological or epistemological frameworks) and I address it/them directly , and clearly . I don’t use the quotes from the prompts in my writing directly (you should have plenty of other examples and evidence to bring up such that you wouldn’t want to waste space on one from the prompts – when others zig; you zag!), but I do use key words or partial phrases from the prompt in my essay, especially in the introduction to make it clear what I am talking about. This greatly helped the concision and clarity of my writing.

A final note: it is essential to display a comprehension and respect for the complexity of the theme and how other, diverging, viewpoints contribute to it equally and validly (even if you disagree with them). You need to show that you have situated the prompts in their broader psycho-social or politico economic or philosophic contexts to show an appreciation for these contexts.

A case study

I’ve included below a case study of an analysis I did of a response to a set of Task A prompts. In this particular case the essay had written above it “against capitalism.”

The prompts were:

1. “Socialism states that you owe me something simply because I exist. Capitalism, by contrast, results in a sort of reality-forced altruism: I may not want to help you, I may dislike you, but if I don’t give you a product or service you want, I will starve. Voluntary exchange is more moral than forced redistribution. ” – Ben Shapiro 2. “Democracy and socialism have nothing in common but one word, equality. But notice the difference: while democracy seeks equality in liberty, socialism seeks equality in restraint and servitude.” – Alexis de Tocqueville 3. “The inherent vice of capitalism is the unequal sharing of blessings; the inherent virtue of socialism is the equal sharing of miseries.” – Winston Churchill 4. “Democracy is indispensable to socialism.” – Vladimir Lenin 5. “We’re going to fight racism not with racism, but we’re going to fight with solidarity. We say we’re not going to fight capitalism with black capitalism, but we;re going to fight it with socialism.” – Fred Hampton

You’ve left here “against capitalism.”

This suggests to me that there’s work to be done on how you confront the prompts before you begin writing. Most people look for the common word in these quotes (in this case socialism, or capitalism) and they say “ah, the theme is capitalism” and then they pick a side and off they go. The problem is that you will then only be writing in the domain of the prompts not in specific response to the prompts. You will lose marks for relevance and precision. The theme is not capitalism here.

The first quote says “capitalism is pragmatic, and more moral than socialism.” The second “democracy (an adjunct of capitalism) and socialism share only a desire for equality, but differ in approach.”

Note: we see already a link to first quote, a mini theme is developing here which is ‘the similarities between socialism and capitalist democracies in their attempt to provide equality or equitability.’ If you wrote an essay contrasting democracy and socialism in how they achieve equality, and to what extent they are successful/moral in this you would be not only scoring far more highly for relevance, but also for “what was made from the task.” Furthermore, this frames your essay to be of much higher sophistication and quality. If you have made a reductive or simple interpretation of the quotes you are forced to expand and write an essay from a small point. This can feel wavering, or unfocussed, or repetitive, and will always be elementary. If you, on the other hand, spend some time really looking at what each quote is saying (I re-write each quote in my own words and then examine them… i stopped doing this toward the end to save time, but the discipline of doing so for my first 30 essays was invaluable) you will have a complex and nuanced understanding of what is being said and the issue at large. The essay, then, becomes not an expansion from a small point (along with inevitable psychometric faults), but a narrowing and focus of a very large and complex issue (necessarily winning psychometrics points for you) into themes and components of that issue that you wish to discuss and give a focussed opinion on.

In this case, I think of the ontology of Pol Pot, Stalin, Mao Zedong – who’s behaviour was illustrative of a utilitarian calculus wherein violence was justified in the name of achieving a socialist utopia. Suffering, the transgression of individual liberty, famine, even mass murder were all justified within the grand narrative of the promise of communist utopias in China, the Society Union, and Cambodia. Mao killed more than 5 times as many people than did Hitler. Humans were reduced to a number, or a flesh bag of chemicals and a physiological set of reactions as the body struggled to fight against emaciation due to poverty in gulags in the soviet union – each person’s unique individuality reduced to a cascading, brutal homogeneity. Where is the morality in this? Is this why Ben Shapiro (quote 1) says capitalism is more moral?

The third quote: a critique of socialism, so we have further re-enforcement for our suspected theme. These people do not think socialism is the most moral way of achieving equality, no matter its intentions. The fourth: tbh I don’t get this. next. (although Lenin was a Bolshevik and was responsible for the Russian revolution and establishment of socialism in Russia pre-soviet union, so perhaps you could simply use that for support of the similarities between the two political ideologies) The fifth: I would skip this entirely. I doubt ACER would give you this prompt. It requires context, and it’s just a weird prompt. Using this would be a red herring in my view.

So, in short, if you dont correctly interpret the quote, and situate it in its broader historical, sociological, psychological, politico-economics contexts, you will struggle to make something profound of the task, and lose points on relevance. Everything that follows is necessarily going to flow from that initial reduction. Your essay is necessarily limited and framed by what you made (or failed to make) of the quotes. Most people go : 5 quotes > one word theme you want to go 5 quotes < essay. Like the quotes are the thinnest part and you make them expansive by developing on them in insightful ways, rather than reducing them to one word and picking a side.

An 80+ essay requires partially agreeing or disagreeing with the obvious interpretation of the comments, rather than flatly. Qualify its limits or contexts in which it arises. Situate the comment in their wider cultural contexts . Body paragraphs are a logical analysis of these ideas. Don’t let this make you fence sit, though. Choose your viewpoint clearly and argue strongly for it, but try situating it off centre of one of the implications of the quotes.

See more writing on 90plusgamsat.com/blog/

or have a look at my existing resources for sale in the store 90plusgamsat.com/shop

Our 90+ Facebook group, where I work for free for ever is at: https://www.facebook.com/groups/419297965763290

About the author

Michael Sunderland

My name's Michael, I achieved 91 in Section II, and 82 overall, in the September '20 sitting. I'm here to show you how I did it. Let's get to work :)

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Subscribe to get the latest updates

Gamsat Review Blog

Everything you need to know about GAMSAT by Dr Peter Griffiths

GAMSAT Essay Examples

Below we have reproduced one of our GAMSAT essay examples sent to us by a student for marking complete with the markers detailed comments.

100 marked essay examples like this are included in the Griffiths GAMSAT Review Home Study Course together with our complete blueprint to writing high scoring Gamsat essays.

We include both high scoring and low scoring essays so you can see the characteristics of both.

For more help writing your GAMSAT essays and to get 100 marked examples like the above please check out Griffths GAMSAT Review

Search Gamsat Review Blog

Gamsat Notes

June 28, 2017, gamsat notes in essay examples | june 28, 2017, “the best argument against democracy is a five minute conversation with the average voter”.

Essay Title: Is democracy providing society with their wants and needs?

The question of whether society appreciates the role of government in providing them with their wants and needs is a controversial one.

On the one hand , government provides a wide range of benefits, such as; child benefits, government issued health cards – providing low cost/free heath care, pensions, among many more. These are clearly very beneficial for society as a whole.

On the other hand , the media will quickly have us believe that our government is a greedy, corporation like institution, where we must select the lesser of evil candidates to take office and run our country. It appears ever too often that we hear of shady government deals with large multinational corporations; costing many of the countries taxpayers, and benefiting only a select few of those closely related to the deal.

Ultimately , I believe society benefits more from our government than caveats. Firstly , our education system is highly desirable, especially when compared to that of the United States (tuition fees related). Although this is a popular topic of debate in the past number of years and should be watched closely. Secondly , society also benefits from our government being pro-disability focused. Regulations in building and construction require features such as wheelchair access as standard to ensure all able, and disable bodied people can gain access to any building. This flows generously into that of fire standards and fire safety. Our government has strict safety regulations that we almost unconsciously benefit from.

Finally, Ireland has an attractive corporate tax rate; which helps vastly in attaining corporations to set up their European headquarters (Google, Facebook, etc.); providing jobs, increasing pay standards, and overall improving the quality of life.

In conclusion, Democracy; at least in Ireland, is benefiting society as a whole in my opinion. A lot of work is needed to ensure improvements can be made in the future. Democracy does benefit society in comparison to other systems of government, but this does not mean it is the most appropriate either. Government system evolve over time along with everything else. I believe Democracy is a step in the right direction; but we are not there yet in terms of the perfect solution (which there may not be one).

Ozimed & Acer Exam Papers

Related Notes:

- Essay Example: “The Liberty of the Individual Must be thus far Limited; He must not Make Himself a Nuisance to Other People”

- Essay Example Rundown – How to Write Essays for the GAMSAT

Cancel Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

GAMSAT Essay Themes

From: acegamsat re: gamsat essay themes.

So, you are completing practice essays and perfecting your structure. You might also be (understandably!) wondering how you are meant to deal with the vast number of themes that might arise in section II, and considering how you should approach type A and B quotes (is there even difference, you ask?). If you are at this stage, then this is the guide for you!

Firstly, the difference between ‘type A’ and ‘type B’ sets of quotes…

Note here that I have referred to type A and B ‘sets of quotes’ rather than ‘essays.’ This was intentional! Sometimes there is the perception that there is a certain ‘type’ of essay that must be written in response to either type A or B quotes, but the reality is that you could craft an effective response for either styles of quotes using a variety of essay styles, including a persuasive essay style or reflective/ creative essay style. The most important thing is to find a style and structure that you understand and can utilise effectively.

Ok, back to the different between type A and B quotes! Type A tends to focus on an issue that is perhaps more ‘objective’ (in that is can be observed playing out in society) and is often a more political issue (think democracy, the environment, terrorism, the legal system etc.), whereas type B quotes usually refer to something that is more subjective (in that many people will have different, individual views on the matter that they have developed over their lives) (think trust, love, relationships, childhood, optimism etc.)

Ok great. Are there any ways of predicting what the theme will be?

The short answer is no! Unfortunately there is no way of predicting what kinds of themes will be included in section II in a given year. It would appear, however, that often at least one of the themes relates to something that is quite topical. This does not necessarily mean that the topic has been apparent in the media in the last week or month or even year. It might be something that has been going around for a while, and the assessors feel as though it would raise interesting ideas for candidates to consider. Currently, for example, you might consider democracy and its utility (in the wake of the US election), gender equality (pretty much always quite topical), or themes surrounding gender identity and sexual orientation (an area which is currently receiving a lot of attention, especially in the field of research).

So, what are some examples of type A and B themes?

Note that the following lists are by no means exhaustive! They are simply suggestions in order to get your brain pumping and for you to build on!

Sample Type A GAMSAT Essay Themes:

- The scientific endeavor

- Human rights

- Conflict/ warfare

- Space exploration

- Stem cell research

- Multiculturalism

- The media and/or social media

- Bureaucracy

Sample Type B GAMSAT Essay Themes:

- Imagination

- Optimism/ attitude

Hopefully this post has left you feeling better prepared to deal with any theme thrown your way!

Happy essay writing!

FREE Resources

If you want your free GAMSAT Practice Test , then click below right now!

Published by acegamsat.com

Subscribe to our newsletter, how to master section ii of the gamsat.

The Only Prep You Need

Skip to content

- DAT-prep.com

- GAMSAT Preparation Courses

- GAMSAT Practice Tests

- GAMSAT Videos

- GAMSAT Scores

- Free GAMSAT

- Board index ‹ GAMSAT Preparation ‹ Discuss your strategies and experience with Section II

- Change font size

Sample Marked GAMSAT Essays on the Environment

Return to Discuss your strategies and experience with Section II

Who is online

Users browsing this forum: No registered users and 0 guests

- Board index

- All times are UTC

The Atlantic’s June Cover Story: Anne Applebaum on How “Democracy Is Losing the Propaganda War”

F or The Atlantic ’s June cover story, “ Democracy Is Losing the Propaganda War ,” staff writer Anne Applebaum reports on how autocrats in China, Russia, and other places around the world are now making common cause with MAGA Republicans to discredit liberalism and freedom everywhere. Applebaum’s story is adapted from her forthcoming book, Autocracy Inc. (publishing July 23), and draws from her exceptional reporting for The Atlantic .

Even in authoritarian states where surveillance is almost total, Applebaum reports, “the experience of tyranny and injustice can radicalize people. Anger at arbitrary power will always lead someone to start thinking about another system, a better way to run society.” This has resulted in autocratic regimes slowly turning their repressive mechanisms outward, into the democratic world. Applebaum writes: “If people are naturally drawn to the image of human rights, to the language of democracy, to the dream of freedom, then those concepts have to be poisoned. That requires more than surveillance, more than close observation of the population, more than a political system that defends against liberal ideas. It also requires an offensive plan: a narrative that damages both the idea of democracy everywhere in the world and the tools to deliver it.”

To accomplish this, Applebaum reports, autocracies are now making systematic efforts to influence both popular and elite audiences, including via the use of state-controlled media—most notably China’s Xinhua news agency and Russia’s RT, but also Venezuela’s Telesur network and Iran’s Press TV, along with numerous others—to create stories, slogans, memes, and narratives promoting the worldview of the autocracies. These, in turn, are repeated and amplified in other countries, translated into multiple languages, and reshaped for local markets around the world.

When these stories make their way to the U.S., Applebaum reports, “a part of the American political spectrum is not merely a passive recipient of the combined authoritarian narratives that come from Russia, China, and their ilk, but an active participant in creating and spreading them. Like the leaders of those countries, the American MAGA right also wants Americans to believe that their democracy is degenerate, their elections illegitimate, their civilization dying. The MAGA movement’s leaders also have an interest in pumping nihilism and cynicism into the brains of their fellow citizens, and in convincing them that nothing they see is true. Their goals are so similar that it is hard to distinguish between the online American alt-right and its foreign amplifiers.” The State Department has in the past decade created a division to preemptively combat (or “prebunk”) foreign disinformation operations. But no such agency exists to combat the spread of Russian and Chinese propaganda within the United States.

“One could call this a secret authoritarian ‘plot’ to preserve the ability to spread antidemocratic conspiracy theories, except that it’s not a secret. It’s all visible, right on the surface,” Applebaum writes. “Russia, China, and sometimes other state actors—Venezuela, Iran, Hungary—work with Americans to discredit democracy, to undermine the credibility of democratic leaders, to mock the rule of law. They do so with the goal of electing Trump, whose second presidency would damage the image of democracy around the world, as well as the stability of democracy in America, even further.”

“ Democracy Is Losing the Propaganda War ” was published today in The Atlantic . Please reach out with any questions or requests: [email protected].

The New Propaganda War

Autocrats in China, Russia, and elsewhere are now making common cause with MAGA Republicans to discredit liberalism and freedom around the world.

/media/cinemagraph/2024/05/10/WEL_Applebaum_PropagandaHP-Portriat_2.mp4)

Listen to this article

Listen to more stories on curio

This article was featured in the One Story to Read Today newsletter. Sign up for it here .

On June 4 , 1989 , the Polish Communist Party held partially free elections, setting in motion a series of events that ultimately removed the Communists from power. Not long afterward, street protests calling for free speech, due process, accountability, and democracy brought about the end of the Communist regimes in East Germany, Czechoslovakia, and Romania. Within a few years, the Soviet Union itself would no longer exist.

Also on June 4, 1989, the Chinese Communist Party ordered the military to remove thousands of students from Tiananmen Square. The students were calling for free speech, due process, accountability, and democracy. Soldiers arrested and killed demonstrators in Beijing and around the country. Later, they systematically tracked down the leaders of the protest movement and forced them to confess and recant. Some spent years in jail. Others managed to elude their pursuers and flee the country forever.

Explore the June 2024 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

In the aftermath of these events, the Chinese concluded that the physical elimination of dissenters was insufficient. To prevent the democratic wave then sweeping across Central Europe from reaching East Asia, the Chinese Communist Party eventually set out to eliminate not just the people but the ideas that had motivated the protests. In the years to come, this would require policing what the Chinese people could see online.

Nobody believed that this would work. In 2000, President Bill Clinton told an audience at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies that it was impossible. “In the knowledge economy,” he said, “economic innovation and political empowerment, whether anyone likes it or not, will inevitably go hand in hand.” The transcript records the audience reactions:

“Now, there’s no question China has been trying to crack down on the internet.” ( Chuckles. ) “Good luck!” ( Laughter. ) “That’s sort of like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall.” ( Laughter. )

While we were still rhapsodizing about the many ways in which the internet could spread democracy, the Chinese were designing what’s become known as the Great Firewall of China . That method of internet management—which is in effect conversation management—contains many different elements, beginning with an elaborate system of blocks and filters that prevent internet users from seeing particular words and phrases. Among them, famously, are Tiananmen , 1989 , and June 4 , but there are many more. In 2000, a directive called “ Measures for Managing Internet Information Services ” prohibited an extraordinarily wide range of content, including anything that “endangers national security, divulges state secrets, subverts the government, undermines national unification,” and “is detrimental to the honor and interests of the state”—anything, in other words, that the authorities didn’t like.

From the May 2022 issue: There is no liberal world order