Digital Commons @ SPU

Home > Academic Units > SPFC > IOP Dissertations

Industrial-Organizational Psychology Dissertations

The Seattle Pacific University Department of Industrial-Organizational Psychology offers both an M.A. and Ph.D. in Industrial-Organizational Psychology.

This series contains successfully defended doctoral dissertations.

Dissertations from 2024 2024

Effects of Advertising Employee Resource Groups (ERGs) on Female Applicants’ Intentions to Pursue Employment Through Perceived Organizational Support , Jamie Crites

Dissertations from 2023 2023

The psychometric evaluation of decent work in India , Jadvir K. Gill

Implicit Trait Policies and Situational Judgment Tests: How Personality Shapes Judgments of Effective Behavior , Alexander Edward Johnson

An Investigation of the Impact of Prosocial Action on Psychological Resilience in Female Volunteer Maskmakers During COVID-19 , Linda D. Montano

To make or buy: How does strategic team selection and shared leadership strategy interact to impact NBA team effectiveness? , Brandon Purvis

Dissertations from 2022 2022

“Intended Between a Man and a Woman”: Examining the LGBTQ Campus Climate of a Non-Affirming Free Methodist University , Justin Cospito

Adverse Work Experiences and the Impact on Workplace Psychological Well Being, Workplace Psychological Distress, Employee Engagement, Turnover Intention, and Work State Conscientiousness , Nicole J. DeKay

Managing One’s Anxiety When Work Narratives Misalign , Shannon Eric Ford and Shannon Ford

The HERO in you: The impact of psychological capital training and perceived leadership on follower psychological capital development and burnout , Alifiya Khericha

CoachMotivation: Leveraging Motivational Interviewing Methodology to Increase Emotion Regulation Ability in the Workplace , Michael R. Nelson

Effects of Pay Transparency on Application Intentions through Fairness Perceptions and Organizational Attractiveness: Diversifying the Workforce by Effectively Recruiting Younger Women , Phi Phan-Armaneous

The space between stress and reaction: A three-way interaction of active coping, psychological stress, and applied mindfulness in the prediction of sustainable resilience , Kait M. Rohlfing PhD

A Quantitative Comparison of Employee Engagement Antecedents , Kirby White

Dissertations from 2021 2021

RAD Managers: Strategic Coaching for Managers and Leaders , Audrey Mika Kinase Kolb

Can Gender Pronouns in Interview Questions Work as Nudges? , Fei Lu

Catalytic Resilience Practices: Exploring the Effects of Resilience and Resilience Practices through Physical Exercise , Mackenzie Ruether

Dissertations from 2020 2020

Softening Resistance Toward Diversity Initiatives: The Role of Mindfulness in Mitigating Emotional White Fragility , Vatia P. Caldwell

When Proenvironmental Behavior Crosses Contexts: Exploring the Moderating Effects of Central Participation at Work on the Work-Home Interface , Bryn E.D. Chighizola

Developing Adaptive Performance: The Power of Experiences and a Strategic Network of Support , Joseph D. Landers Jr.

Purposeful Investment in Others: The Power of a Character of Service , Kayla M. Logan

Developmental Experiences Impacting Leadership Differentiation in Emerging Adults , Gabrielle E. Metzler

Fighting dirty in an era of corporate dominance: Exploring personality as a moderator of the impact of dangerous organizational misconduct on whistleblowing intentions , Keith Andrew Price

CoachMotivation: Developing Transformational Leadership by Increasing Effective Communication Skills in the Workplace , Megan L. Schuller

The Relationship Between Authentic Leadership and Resilience, Moderated by Coping Skills , Alice E. Stark

Building and Sustaining Hope in the Face of Failure: Understanding the Role of Strategic Social Support , Kira K. Wenzel PhD

Dissertations from 2019 2019

Exploring the Buffering Effects of Holding Behaviors on the Negative Consequences of Workplace Discrimination for People of Color , Heather A. Kohlman Olsen

Employee Engagement Around the World: Predictors, Cultural Differences, and Business Outcomes , Amanda Munsterteiger

Dissertations from 2018 2018

Ignatian Spirituality in Vocational Career Development: An Experimental Study of Emerging Adults , Scott Campanario

Narrative Leadership: Exploring the Concept of Time in Leader Storytelling , Helen H. Chung Dr.

Vulnerability in Leadership: The Power of the Courage to Descend , Stephanie O. Lopez

An Exploratory Study Examining a Transformational Salesperson Model Mediated by Salesperson Theory-of-Mind , Philip (Tony) A. Pizelo Dr.

Dissertations from 2017 2017

Developing Conviction in Women Leaders: The Role of Unique Work and Life Experiences , McKendree J. Hickory

The Role of Organizational Buy-in in Employee Retention , Serena Hsia

The Psychometric Evaluation of a Personality Selection Tool , James R. Longabaugh

Approaching Stressful Situations with Purpose: Strategies for Emotional Regulation in Sensitive People , Amy D. Nagley

Validation of the Transformative Work in Society Index: Christianity, Work, and Economics Integration , John R. Terrill

Seeking Quality Mentors: Exploring Program Design Characteristics to Increase an Individual’s Likelihood to Participate as a Mentor , Kristen Voetmann

Predicting Employee Performance Using Text Data from Resumes , Joshua D. Weaver

College for The Sake of What? Promoting the Development of Wholly Educated Students , Michael P. Yoder

Dissertations from 2016 2016

Am I a Good Leader? How Variations in Introversion/Extraversion Impact Leaders’ Core Self-Evaluations , Marisa N. Bossen

Dissertations from 2015 2015

The Development of Job-Based Psychological Ownership , Robert B. Bullock

Generational Differences in the Interaction between Valuing Leisure and Having Work-Life Balance on Altruistic and Conscientious Behaviors , Sandeep Kaur Chahil

Obtaining Sponsorship in Organizations by Developing Trust through Outside of Work Socialization , Katie Kirkpatrick-Husk

Managing Work and Life: The Impact of Framing , Hilary G. Roche

Men and Women in Engineering: Professional Identity and Factors Influencing Workforce Retention , Caitlin Hawkinson Wasilewski

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Collections

- Disciplines

Contributors

- Submit Research

- Terms and Conditions

- SPU Department of I-O Psychology

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

Home > Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Capstone Projects > ALL-PROGRAMS > Industrial/Organizational Psychology Theses

Industrial/Organizational Psychology Theses

Theses/dissertations from 2022 2022.

Employee Satisfaction and Perceptions of Organizational Leadership Accountability , Caroline M. Clancy

The Effects of Transformational Leadership on Sales Performance in a Multilevel Marketing Organization , Alexander Techy

Theses/Dissertations from 2021 2021

Too Illegit to Quit: The Impact of Illegitiate Tasks on Turnover Intentions and Well-Being , Jacob Wessels

Theses/Dissertations from 2020 2020

The Effects of Positive and Negative Humor at Work , Trevor Frey

Diverse Teams, Team Effectiveness, and the Moderating Effect of Organizational Support , Hannah Tilstra

Theses/Dissertations from 2019 2019

Effects of Psychological Need Satisfaction on Proactive Work Behaviors , Shota Kawasaki

Theses/Dissertations from 2018 2018

Gender Differences in Development Center Performance in a Healthcare Organization , Samuel Lawson

Theses/Dissertations from 2017 2017

Success in Learning Groups: Where have we been? And Where are we going? , Tiffany Michelle Ackerman

Individual Differences as Predictors of Success for Learning Community Students , Nicole Haffield

Moderating Effects of Resilience and Recovery on the Stressor-Strain Relationship Among Law Enforcement Officers , Austin Hearne

Selection Portfolio: Applying Modern Portfolio Theory to Personnel Selection , Eric Leingang

The Hogan Development Survey: Personality in Selecting and Training Aviation Pilots , Jenna McChesney

Evaluating a Measure of Student Effectiveness in an Undergraduate Psychology Program , Colin Omori

Participant Self-Assessment of Development Center Performance , Ryan Powley

“Let’s be clear”: Exploring the Role of Transparency Within the Organization , Maxwell Salazar

Theses/Dissertations from 2016 2016

The Effect of an Email Intervention Tailored to Highly Ambitious Students on University Retention , Lauren Bahls

911,What's My Emergency? Emotional Labor, Work-Related Rumination, and Strain Outcomes in Emergency Medical Dispatchers , Jessica Lee Deselms

Can You Hack It? Validating Predictors for IT Boot Camps , Courtney Gear

Intervention E-mails and Retention: How E-mails Tailored to Personality Impact an Undergraduate Student's Decision to Return to School or Not , John Kelly Heffernon

Prudence and Persistence: Personality in Student Retention , Logan J. Michels

Examination of the Antecedents, Reactions, and Outcomes to a Major Technology-driven Organizational Change , Ngoc Dinh Nguyen

Training Coping Techniques to Reduce Statistics Anxiety , Brittany Prothe

Assessing the Effect of Personality Characteristics of Minnesota Golfers on the Brand Equity of Golf Drivers , Eric Schinella

Mood and Engagement Contagion in a Call Center Environment , Sarah Welsch

Why Do Some Employees Readjust to Their Home Organizations Better Than Others? Job Demands-Resources Model of Repatriation Adjustment , Yukiko Yamasaki

Theses/Dissertations from 2015 2015

Fitting Flow: An Analysis of the Role of Flow Within a Model of Occupational Stress , Jeffrey Alan Dahlke

Created Equal? Comparing Disturbing Media Outcomes Across Occupations , Christine Nicole Gundermann

The Influence of Perceived Similarity, Affect and Trust on the Performance of Student Learning Groups , Jennifer Louise Lacewell

Depth of a Salesman: Exploring Personality as a Predictor of Sales Performance in a Multi-Level Marketing Sample , Colleen Rose Miller

Expatriate Adjustment of U.S. Military on Foreign Assignment:The Role of Personality and Cultural Intelligence in Adjustment , Jennifer Pauline Stockert

Organizational Trust As a Moderator of the Relationship between Burnout and Intentions to Quit , Glenn Trussell

Theses/Dissertations from 2014 2014

Ethnic Names, Resumes, and Occupational stereotypes: Will D'Money Get the Job? , Tony Matthew Carthen

Examining the Effectiveness of the After Action Review for Online and Face-to-Face Discussion Groups , William Cradick

University Commitment: Test of a Three-Component Model , Brittany Davis

An Investigation into the Effect of Power on Entrepreneurial Motivations , Jack Reed Durand

Development and Enhancement to a Pilot Selection Battery for a University Aviation Program , Ryan Thomas Hanna

Overseas Assignments: Expatriate and Spousal Adjustment in the U.S. Air Force , Andrew R. Hayes

The Roles of Social Support and Job Meaningfulness in the Disturbing Media Exposure-Job Strain Relationship , Hung T. Hoang

Student Assessment of Professor Effectiveness , Roger Emil Knutson

Dirty Work: The Effects of Viewing Disturbing Media on Military Attorneys , Natalie Lynn Sokol

Theses/Dissertations from 2013 2013

Selection System Prediction Of Safety: A Step Toward Zero Accidents In South African Mining , Rachel Aguilera-Vanderheyden

Examining Generational Differences across Organizational Factors that Relate to Turnover , Kimberly Asuncion

An Investigation of Online Unproctored Testing and Cheating Motivations Using Equity Theory and Theory of Planned Behavior , Valerie Nicole Brophy

Race, Gender, and Leadership Promotion: The Moderating Effect of Social Dominance Orientation , Chelsea Chatham

Disentangling Individual, Organization, and Learning Process Factors that Drive Employee Participation , Diana Colangelo

Will [email protected] get the Job Done? An Analysis of Employees' Email Usernames, Turnover, and Job Performance , Jessica Marie Lillegaard

Using Personality Traits to Select Customer-Oriented Security Guards , Tracy Marie Shega

Mobile Internet Testing: Applicant Reactions To Mobile Internet Testing , Sarah Smeltzer

Ethical Leadership: Need for Cross-Cultural Examinations , Shuo Tian

Development of a Pilot Selection System for a Midwestern University Aviation Program , Kathryn Wilson

Theses/Dissertations from 2012 2012

Identifying Organizational Factors that Moderate the Engagement-Turnover Relationship in a Healthcare Setting , Stevie Ann Collini

Organizational Wellness Programs: Who Participates and Does it Help? , Justin Michael Dumond

Coping with Economic Stressors: Religious and Non-Religious Strategies for Managing Psychological Distress , Jonathan Karl Feil

The Creation and Validation of a Pilot Selection System for a Midwestern University Aviation Department , Jacob William Forsman

The National Survey of Student Engagement as a Predictor of Academic Success , Paul Michael Fursman

Perceptions of a Text-Based SJT versus an Animated SJT , Amanda Helen Halabi

The Moderating Effects of Work Control and Leisure Control on the Recovery-Strain Relationship , Jason Nicholas Jaber

The Role Social Influence Has On Dormitory Residents' Responses to Fire Alarms , Michael Otting Leytem

The Impact of Culture, Industry Type, and Job Relevance on Applicant Reactions , Olivia Martin

Someone Who Understands: The Effect of Support on Law Enforcement Officers Exposed to Disturbing Media , Jessica Morales

The Effects of Task Ambiguity and Individual Differences on Personal Internet Use at Work , Hitoshi Nishina

The Roles of Self-Efficacy and Self-Deception in Cheating on Unproctored Internet Testing , Christopher Adam Wedge

Theses/Dissertations from 2011 2011

Assessing Transfer Student Performance , Hyderhusain Shakir Abadin

Should You Hire [email protected]?: An Analysis of Job Applicants' Email Addresses and their Scores on Pre-Employment Assessments , Evan Blackhurst

The Dirty Work Of Law Enforcement: Emotion, Secondary Traumatic Stress, And Burnout In Federal Officers Exposed To Disturbing Media , Amanda Harms

Comparison of a Ranking and Rating Format of the 5Plus5: A Personality Measure , Kristy Lynn Jungemann

Cultural Intelligence and Collective Efficacy in Virtual Team Effectiveness , Pei See Ng

Relationship Type Determines the Target of Threat in Perceived Relational Devaluation: Organizational Self vs. Interpersonal Relationships , Peter Sanacore

Development of an Assessment Center as a Selection Method for I/O Graduate Applicants , Ting Tseng

Hiking, Haiku, or Happy Hour After Hours: The Effects of Need Satisfaction and Proactive Personality on the Recovery-Strain Relationship , Paige Woodruff

Exploring the Antecedents of Organizational Citizenship Behavior in Knowledge-based Virtual Communities , Luman Yong

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

Author Corner

- All Authors

- Submit Research

University Resources

- Digital Exhibits

- ARCH: University Archives Digital Collections

- Library Services

- Minnesota State University, Mankato

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

A meta-analysis of psychological empowerment: Antecedents, organizational outcomes, and moderating variables

- Open access

- Published: 28 February 2023

- Volume 43 , pages 1759–1784, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Marta Llorente-Alonso ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6884-2595 1 , 2 nAff3 ,

- Cristina García-Ael 3 &

- Gabriela Topa 3

13k Accesses

9 Citations

40 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Psychological empowerment (PE) is a subjective, cognitive and attitudinal process that helps individuals feel effective, competent and authorized to carry out tasks. Over the last twenty years, research into PE has reported strong evidence reaffirming its role as a motivational factor in organizational psychology. In this study, the aim is to systematically review, analyze and quantify correlational empirical research focusing on empowerment, as understood by the theory developed by Spreitzer et al. ( 1995a , b ), using meta-analytical techniques. The study also analyses the antecedents and consequences of PE and explores potential moderators of the relationship between this variable and its correlates. The electronic search encompassed studies dating from the publication of Spreitzer's empowerment scale ( Academy of Management Journal , 38 , 1442–1465, 1995b ) up to January 2019. It was conducted in database aggregators, as well as in Metabus, occupational psychology journals and doctoral thesis repositories. Of the 1110 records identified, 94 were included in the meta-analysis. Most of the studies included used purposive or convenience sampling and had a cross-sectional study design. We focused on searching for studies that use a survey analysis approach. We extracted information about effect size (ES) in the associations between PE and its antecedents and consequences, and used the Comprehensive Meta-analysis 2.0 program to carry out the analyses (Borenstein et al., 2005 ). Effect size was calculated as the Pearson correlation ( r ), processed using Fisher's Z transformation. A random effects model was used and heterogeneity was analyzed to detect moderator variables. In relation to antecedents, in all meta-analyses, non-significant results were found only for education ( r = -.001, CI [-.06, .06]) and organizational rank ( r = .10, CI [-.16, .36]). All meta-analyses focusing on the association between psychological empowerment and its consequences returned significant results. Job satisfaction ( r = .50) and organizational commitment ( r = .51) had the largest effect sizes. Our results suggest which factors may be more important for generating empowerment among employees in accordance with the profession in which they work and their culture of origin. The main novelty offered by our results is that they indicate that age moderates the relationship between empowerment and the majority of the antecedents studied, a finding not reported in other meta-analyses. The present meta-analysis may help encourage organizations to pay more attention to PE, focusing their efforts on improving or strengthening certain structures or factors. Empowerment initiatives or programs focused on employee well-being lead to a workplace in which people are motivated and have a sense of purpose. Our results allow us to recommend interventions that enhance and improve the antecedents of EP. Finally, the present meta-analysis may help encourage organizations to pay more attention to the antecedents and consequences of PE, focusing their efforts on improving or strengthening certain structures or factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Empowering satisfaction: analyzing the relationship between empowerment, work conditions, and job satisfaction for international center managers

The role of workers’ motivational profiles in affective and organizational factors.

Do it yourself, but I can help you at any time: the dynamic effects of job autonomy and supervisor competence on performance

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Empowerment theories.

Over the last twenty years, research into psychological empowerment has reported strong evidence reaffirming its role as a motivational factor in organizational psychology. The term "empowerment" was coined in 1977 by Kanter, who identified it as the cornerstone for improving quality and service in organizations. Kanter believed that by empowering workers, organizations could ensure that they responded more flexibly to the different situations which may arise, instead of merely obeying rules in an automatic fashion. The aim was to give workers greater control over their resources and more access to information, in order to enable them to deal more effectively with customer requirements and even elevate their status within the organization. Kanter's social-structural perspective was therefore focused on empowering structures, policies and practices, which she viewed as indicators of empowerment. Subsequently, other authors have also identified these same elements as contextual antecedents of empowerment (Seibert et al., 2004 ).

The first empowerment theories did not focus only on organizations. Indeed, authors such as Rappaport ( 1984 ) and Zimmerman ( 2000 ) considered the concept to be a key mechanism of community psychology, perceiving it as a process in which people, organizations and communities gain greater control over their lives (Rappaport, 1984 ). Zimmerman ( 2000 ) argued that empowerment is a multilevel construct that can be analyzed at different levels: individual, organizational and community. Moreover, within each level of analysis, empowerment can be understood as both a process (a mechanism through which people gain control and influence over their lives) and an outcome (the consequence of different processes). For example, activities, actions and structures may be empowering, and the outcome of these processes is a feeling of empowerment (Zimmerman, 2000 ). According to this author, psychological empowerment refers to the individual level of analysis (Zimmerman, 1995 ), although he also argued that it may take different forms, depending on the people and contexts that surround it, and is not, therefore, a static concept. Consequently, he broke psychological empowerment down into three components: intrapersonal, interactional and behavioral. The intrapersonal component refers to people's self-perceptions and includes motivation to control, perceived competence and self-efficacy, and perceived control in specific domains.

Conger and Kanungo ( 1988 ) are generally considered to be the first authors to talk about the concept of psychological empowerment (PE). They distinguished between empowerment based on management and social influence literature, and that based on psychology literature. They defined empowerment as a relational construct in the practice of management, since it describes the process by which a leader shares their power with their subordinates in a dynamic relationship. However, they also recommended that empowerment be understood as a motivational construct, as (they argued) it is indeed viewed in psychology literature. They defined empowerment as "a process of enhancing feelings of self-efficacy among organizational members through the identification of conditions that foster powerlessness and through their removal both by formal organizational practices and informal techniques of providing self-efficacy information" (p.474). They therefore distinguished between different meanings of empowerment: empowerment in management terms, as an attempt to delegate or share power; and empowerment in psychological terms, as a means of motivating by enhancing personal efficacy.

Thomas and Velthouse ( 1990 ) further developed the motivation-centered theory of PE defined by Conger and Kanungo ( 1988 ). They refined the model, viewing empowerment as a motivational factor linked to intrinsic task motivation and specifying the set of cognitive components aimed at generating this intrinsic motivation: impact, competence, meaning and choice or self-determination. Impact refers to the degree to which one behavior stands out from the rest when attempting to achieve one's goals, and can be understood as the act of obtaining the desired effect through excellent conduct in a specific activity. Competence refers to the degree of skill demonstrated by the individual in the required task. This component coincides with the construct proposed by Bandura ( 1977 ) in the field of clinical psychology, known as self-efficacy (Thomas & Velthouse, 1990 ). Meaning is the "value of the goal in relation to a person's ideals or standards". It represents the psychological energy invested in a task. Finally, self-determination is the perception of having a choice about what one does, and "involves causal responsibility for a person's actions" (p.673).

Spreitzer ( 1995a ) continued conceptualizing empowerment by focusing on the workplace, building on previous studies published by Thomas and Velthouse ( 1990 ). She developed a questionnaire to measure PE at work, including the four dimensions proposed by Thomas and Velthouse ( 1990 ), which she herself had subsequently identified independently (Spreitzer, 1992 ). These four dimensions (impact, competence, meaning and self-determination) correspond to the intrapersonal component of empowerment defined by Zimmerman ( 1995 ). Spreitzer ( 1995b ) defined PE as a motivational construct that reflects an active orientation and self-perception of one's capacity to shape one's own work role and is manifested in four cognitions. She also argued that each of the four dimensions proposed for evaluating PE contributes to a global construct of empowerment. However, although the lack of any one dimension may diminish empowerment, it will not eliminate it altogether.

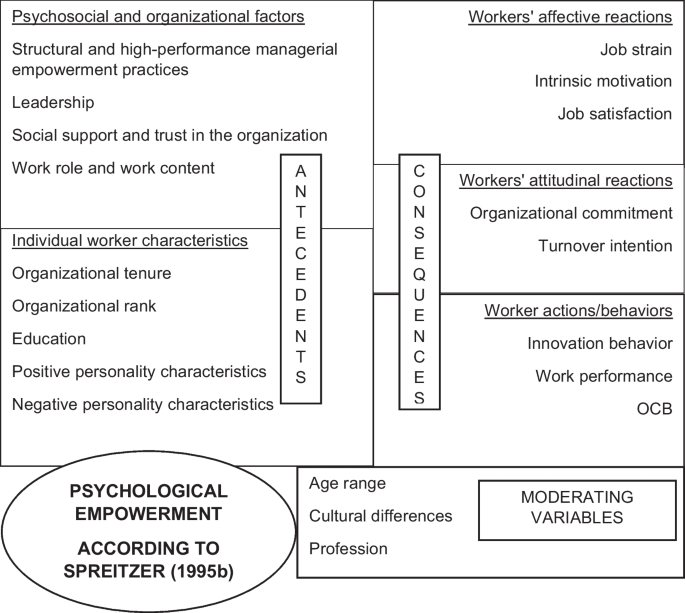

According to the theories outlined above, psychological empowerment may be defined as a cognitive, subjective and motivational process by which individuals perceive themselves as effective and competent for carrying out tasks, with sufficient capacity to ensure their completion. Moreover, the tasks themselves are deemed relevant and meaningful, and individuals feel they have freedom of choice in relation to them. The most comprehensive theory of PE is that developed by Spreitzer ( 1995a , b ). Her model includes both the social-structural antecedents of PE and its behavioral consequences. Seibert et al. ( 2011 ) carried out the first meta-analytical review of the concept of PE, integrating other theoretical approaches also, such as the social-structural one and that based on teams. Some years later, Maynard et al. ( 2013 ) conducted another meta-analysis, analyzing PE in teams and coding the studies aggregated to team level. Neither of these meta-analyses focused specifically on Spreitzer's measure of psychological empowerment, and both included other measures in their systematic reviews (Menon's empowerment scale ( 1995 ) in the first and Kirkman and Rosen's ( 1999 ) measure of team empowerment in the second).

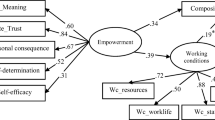

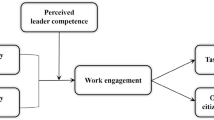

The aim of the present study is to perform a systematic review of the concept of psychological empowerment, using meta-analytical techniques. To this end, it analyzes and quantifies correlational empirical research focusing on PE, as understood by the theory developed by Spreitzer ( 1995a , b ). The ultimate aim is to gain greater insight into the antecedents and consequences of the concept of PE. The study also explores potential moderators of the relationship between empowerment and its correlates and compares the results obtained with those reported by previous meta-analytical studies, in order to highlight the principal differences and suggest possible avenues of future research. Moreover, previous meta-analyses have highlighted a lack of research into certain organizational variables that have become highly relevant to the field of work psychology over the past decade, identifying, for example, a need for studies that explore the relationship between psychological empowerment and variables such as job crafting, engagement and organizational identification. For this reason, in the present study, we analyze whether this gap in the literature is still evident. Figure 1 shows the model proposed for the meta-analysis.

Proposed model for the meta-analysis based on Seibert et al. ( 2011 ) and Spreitzer ( 1995b )

Antecedents of psychological empowerment

Spreitzer ( 1995b ) included the contextual antecedents of PE in her model, positing that role ambiguity, sociopolitical support, access to information, access to resources and a work unit culture would be seen as empowering by workers. Other individual or characteristic personality factors, such as locus of control and self-esteem, have also been viewed as influencing cognitions of empowerment and may generate greater intrinsic motivation (Spreitzer, 1995a ). Based on these previous studies, we distinguish between two types of factor in relation to the antecedents of PE: 1) psychosocial and organizational factors, and 2) individual worker characteristics.

Psychosocial and Organizational Factors

Structural and high-performance managerial empowerment practices.

This group includes both structural empowerment and high-performance managerial practices. Access to organizational empowerment structures influences perceptions of power in the work environment (Kanter, 1977 ). The elements that make up structural empowerment are learning opportunities, access to information, access to resources and access to support in the workplace (Kanter, 1977 ). As Seibert et al. ( 2011 ) proposed in their meta-analysis, we also include high-performance practices in this group, since they are believed to improve performance by increasing the amount of information and skills workers have in relation to their job. The factors included in this group refer to managerial practices oriented towards offering workers greater access to support, resources, information, learning, innovation and growth, which in turn act as motivational and empowering elements. This category reflects the extent to which jobs or managers provide workers with opportunities in relation to the different variables mentioned. In terms of structural empowerment, Monje Amor et al. ( 2021 ) observed that psychological empowerment partially mediated the positive link between this variable and work engagement, which in turn was related to better task performance and lower intention to quit. The categories and primary variables included in the present meta-analysis are outlined in detail in the Appendix (Tables 6 and 7 ).

Hypothesis 1a : Structural and high-performance managerial empowerment practices in the organization will, in general, be positively associated with PE.

The leadership factor encompasses all those practices or forms of leadership that are geared towards motivating workers and therefore seek to enhance their perception of empowerment. Leadership initiates a motivational process leading to empowerment and employees also tend to feel increasingly empowered when their leaders behave in a way that is viewed as positive (Laschinger et al., 2014 ). Indeed, some questionnaires on leadership styles suggest that empowerment may form part of the transformational leadership process. Specifically, the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ)—Short Form 5X (Avolio & Bass, 2004 ) includes a dimension called extra effort. This factor reflects the degree to which a leader is able to motivate an employee to do more than they expected to do, and to what extent that same leader manages to increase their desire to work hard and to succeed. Transformational leadership posits that transformational leaders are those who are able to involve and therefore empower their followers by fostering identification with goals, values and other members of the organization (Kark et al., 2003 ).

Rodríguez et al. ( 2017 ) also take into account the conceptual overlap between transformational leadership and authentic leadership. Authentic leadership has been considered a latent construct that serves as the foundation for transformational leadership (Avolio & Gardner, 2005 ) and contributes to the formation and development of members’ psychological capital (Jang, 2022 ). The ability of an authentic leader to develop their followers’ psychological capital helps empower them. Empowerment has been proposed as the mechanism through which authentic leadership influences performance (Walumbwa et al., 2007 ).

For its part, Leader-member exchange theory holds that the quality of the relationship between a leader and their followers plays a key role in determining how workers respond to their work environment (Davies et al., 2011 ). Arnold et al. ( 2000 ) describe empowering leaders as those who facilitate employee performance by enabling and encouraging workers in their work roles. Other authors have also argued that charismatic leadership is associated with a wide range of positive organizational outcomes and charismatic leaders are able to empower their followers to act beyond their expectations (Hepworth & Towler, 2004 ). Sylvia Nabila et al. ( 2021 ) found an indirect positive relationship between leadership styles (transformational leadership and transactional leadership) and task performance, with this relationship being mediated by psychological empowerment. In light of the above, we hypothesized that certain leadership styles would lead to major changes in followers' attitudes and behaviors, prompting them to accomplish more than expected.

Hypothesis 1b : Empowering, transformational and charismatic leadership styles and behaviors will be positively and significantly associated with workers' PE.

Social support and trust in the organization

This category includes sociopolitical support, support from the organization, rewards or income and trust in the organization. Spreitzer ( 1996 ) argued that certain managerial practices that are likely to improve sociopolitical support encourage people to trust each other, which in turn reduces the forces of domination at work and enhances empowerment. This category is closely linked to the " structural and high-performance managerial empowerment practices " one, the main difference being that, in this group, the emphasis is not on opportunities for or access to managerial elements, but rather on workers' perceptions of the support provided by the organization. The category " social support and trust in the organization " refers to the individual's perception of real rewards, trust and support, beyond the opportunity to access certain elements.

Interpersonal, mutual or dyadic trust between workers and supervisors has been found to facilitate activities in terms of organizational behavior and enables workers to feel empowered (Ergeneli et al., 2007 ). Seibert et al. ( 2011 ) refer to sociopolitical support as the degree to which work-related elements provide workers with material, social and psychological resources. According to Maynard et al. ( 2013 ), organizational support "can include actual resources that the team is able to obtain from other entities within an organization, [as well as] communication and coordination with other teams". As such, interpersonal trust and sociopolitical or organizational support through either resources or rewards can be considered facilitating factors that help enhance workers' motivation, thereby empowering them. In this sense, a study carried out by Gill et al. ( 2019 ) supports the idea that trust predicts feelings of empowerment among subordinates, as well as reciprocal feelings of trust towards supervisors. Moreover, the results of this study also support the idea that empowerment may play a unique mediating role in the relationship between subordinates’ feelings of being trusted and their well-being and work attitudes.

Hypothesis 1c : Greater social support and trust in the organization will be positively and significantly associated with PE.

Work role and work content

This category includes variables that explain the characteristics of the work content and the clarity of work roles. The concept work role comprises the set of tasks/activities that an individual is expected to perform in their job. When their roles are ambiguous and there is no clear definition of the tasks they are expected to perform, workers cannot be psychologically empowered. Furthermore, opportunities for empowerment are limited when employees perform routine and repetitive tasks. According to Yukl and Becker ( 2006 ), “there is more potential for meaningful work and self-determination in jobs that have complex tasks and enriching job characteristics”.

Morgeson and Humphrey ( 2006 ) developed a measure to assess job characteristics and argued that many terms have been used to describe similar job characteristics (defined as the attributes of the task, the job itself, and the social and organizational environment). According to these authors, the association between work characteristics and outcomes is moderated by several factors, one important one being psychological empowerment. Moreover, it has also been argued that although some employees may respond more positively than others to motivational characteristics, very few respond negatively (Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006 ).

Towsen et al. ( 2020 ) found that authentic leadership exerts its influence on work engagement through psychological empowerment, regardless of the level of employees' role clarity. However, these authors also suggested that, contrary to expectations, the nomological proximity of authentic leadership and role clarity may be linked to this result. Spreitzer ( 1996 ) found a strong negative association between role ambiguity and PE and Karasek ( 1979 ) developed the demand-control at work model to explain job strain in terms of the balance between the demands of the job and the level of control (opportunities to develop personal skills and decision latitude) enjoyed by workers over them. High-stress jobs, characterized by high demands and low control, have been associated with lower psychological empowerment levels among workers (Laschinger et al., 2001a , b ). A negative work environment may lead to demotivation and the inability to carry out the tasks required by the job. According to conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll, 2001 ), a negative work environment is one with too few resources. This lack of resources results in workers’ inability to perform their assigned tasks or to obtain new resources to minimize the problem. According to Zhou and Chen ( 2021 ), the loss of resources leads to stress, which in turn generates an iterative spiral. Psychological empowerment can prevent these resource loss spirals.

Hypothesis 1d : An adequate work environment, with well-defined roles, an absence of excessive demands and perceived control over one’s job, will be positively and significantly associated with PE.

Individual worker characteristics

This category includes worker characteristics such as organizational rank, organizational tenure and education level. These variables feature as control or demographic variables in many studies (Llorente-Alonso & Topa, 2018 ; Wang & Howell, 2012 ), although they are only considered key variables in a few (Malik & Courtney, 2010 ). In the present study, we view individual characteristics (tenure, rank in the organization, education, etc.) as proxy variables indicating the worker’s level of knowledge, skill or experience, as well as their contribution to the organization. These proxy variables make it possible to obtain others of greater interest, through a correlation with the inferred value.Seibert et al. ( 2011 ) argued that individual characteristics are linked to empowerment.Variables related to human capital and employees' demographics are closely linked to career success (Wayne et al., 1999 ), and may have a positive impact on worker empowerment.

Significant results have been reported which suggest that these variables are associated with greater worker empowerment, although a meta-analysis encompassing all research to date is required since, in some cases, the results are contradictory. Spreitzer ( 1996 ) found significant associations between education level and PE, and in a sample of healthcare workers, Koberg et al. ( 1999 ) observed greater empowerment among those who had been with their organization for longer and had a higher rank. However, these authors found no significant association between education and empowerment. Prabha et al. ( 2021 ) found that faculty members with above-average age exhibited greater psychological empowerment, motivation and satisfaction. Furthermore, faculty members with above-average experience possessed a higher level of PE and satisfaction. These results prompt us to hypothesize that experience and organizational tenure may lead to greater empowerment.

Moreover, this category also includes personality factors such as locus of control, attributional style and self-control, etc. The extant research suggests that workers with an internal locus of control have higher expectations of their impact on certain tasks than those with an external locus of control (Thomas & Velthouse, 1990 ). According to the cyclical and dynamic model established by Thomas and Velthouse ( 1990 ), interpretive styles influence the way in which individuals can empower or disempower themselves.

Hypothesis 2a : Greater organizational tenure will be associated with greater PE.

Hypothesis 2b : Higher organizational rank will be positively and significantly associated with PE.

Hypothesis 2c : Higher education levels will be associated with greater PE.

Hypothesis 2d : Positive personality characteristics will positively influence PE.

Hypothesis 2e : Negative personality characteristics will be negatively and significantly associated with PE.

Consequences of psychological empowerment

Many studies have sought to analyze the consequences of PE. Spreitzer ( 2008 ) highlighted the importance of feeling empowered at work for obtaining positive individual outcomes. Other meta-analyses have divided the consequences of PE into two groups. For example, Seibert et al. ( 2011 ) distinguished between attitudinal and behavioral consequences, whereas Maynard et al. ( 2013 ) made a distinction between performance variables and affective reactions. In this study, we establish three categories: workers' affective reactions, workers' attitudinal reactions and the actions or behaviors generated by empowerment. We therefore distinguish between the emotional reactions generated by the feeling of empowerment, the tendency or willingness to act in a certain way and the behaviors generated by PE.

Workers' attitudinal reactions

Attitude can be defined as a state of mental readiness, organized through experience, which has a direct influence on a person's behavior (Allport, 1935 ). This tendency to act in a certain way is considered to be directly influenced by motivational variables. Some studies have associated greater PE with a weaker turnover intention (Islam et al., 2016 ), and Avolio et al. ( 2004 ) argued that empowered employees see themselves as more capable and more able to significantly influence the work they perform. They are also more likely to make an additional effort, act independently and be more committed to their organization. Higher levels of PE have been associated with greater organizational commitment, although some studies have found differences in the degree of this commitment in accordance with the country in which the data were collected (Ahmad & Orange, 2010 ).

Aljarameez ( 2019 ) conducted a study in which psychological empowerment was found to have a small moderating effect on the relationship between structural empowerment and continuance commitment. In most of the studies included in the meta-analysis presented here, organizational commitment refers to the Three-Dimensional Model of Organizational Commitment, which encompasses affective, continuance, and normative commitment; and studies include a general measure of commitment made up of these three components (Allen & Meyer, 1990 ).

However, in the studies by Chen et al. ( 2011 ), Kabat-Farr et al. ( 2018 ), Redman et al. ( 2009 ) and Hill et al. ( 2014 ), only the affective commitment subscale was used. For their part, Janssen ( 2004 ) and Raub and Robert ( 2012 ) used the Organizational Commitment Questionnaire developed by Mowday et al. ( 1979 ).

Hypothesis 3a : Greater PE will be associated with stronger organizational commitment.

Hypothesis 3b : PE will be negatively and significantly associated with turnover intention. The more empowered the worker, the weaker their intention to leave the organization.

Workers' affective reactions

Laschinger et al. ( 2001a , b ) argue that the strategies proposed in Kanter's empowerment theory have the potential to reduce job strain and improve employee job satisfaction. They theorize that greater psychological empowerment provides an understanding of the mechanisms that intervene between structural work conditions and key organizational outcomes. Therefore, according to Affective Event Theory, when employees are excited about and immersed in their work, they are more likely to want to make a greater contribution to their organization (Park et al., 2021 ). According to this theory, dispositions and work events can lead to affective reactions, which in turn generate affect driven behavior (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996 ).

Job strain occurs when workers are subject to many psychological demands yet have little control over them (Karasek, 1979 ). Prolonged strain results in an occupational syndrome known as burnout, which is characterized by emotional and physical exhaustion, depersonalization and low levels of perceived personal accomplishment (Maslach & Jackson, 1982 ). Burnout occurs in the presence of chronic stressors. The original model encompassed only human service providers and education workers, although it has subsequently been found to be applicable to any occupation (Leiter & Schaufeli, 1996 ). Calvo and García ( 2018 ) argue that PE is the result of structural empowerment, and may therefore act as a protective factor against chronic stressors in the workplace. Laschinger et al. ( 2001a , b ) found that greater PE strongly influenced both the degree of occupational strain felt by workers and their job satisfaction. According to Heron and Bruk-Lee ( 2019 ), the experience of high stress at work interferes with the process whereby empowerment may impact desirable work attitudes and safety-related behaviors. The findings of their study highlight the importance of understanding the effects of workplace stress for predicting critical outcomes.

Job satisfaction is one of the most widely studied affective reactions among workers, and is considered an indicator of psychological health and well-being. According to Spector ( 1997 ), job satisfaction is the way people feel about their job and its different aspects, and is linked to the degree to which they like or dislike it. This author also argues that workers' level of satisfaction may affect behaviors linked to good organizational functioning. For example, workers with greater PE, and therefore a stronger perception of their own competence and impact, tend to feel more satisfied with their jobs. A recent meta-analysis has shown that the direct association between psychological empowerment and job satisfaction is strong, positive and significant (Mathew & Nair, 2021 ).

Finally, Thomas and Velthouse ( 1990 ) identified the four dimensions of PE as the cognitive components of intrinsic task motivation. However, as Gagné et al. ( 1997 ) pointed out, although these authors equate feelings of empowerment with intrinsic motivation, they also argue that the four components of empowerment are a proximal cause of intrinsic task motivation and satisfaction (Thomas & Velthouse, 1990 ). Gagné et al. ( 1997 ) believed that motivation is not conceptually the same as its antecedents, but is rather the energy that prompts behavior. For its part, competence is a previous cognitive evaluation of both one's context and oneself. The more positive the result of the evaluation, the more energy is generated. Consequently, in the present study, although PE is considered a motivational factor, we do not assimilate it into the concept of intrinsic motivation, but view it rather as an antecedent.

Hypothesis 3c : PE will be negatively and significantly associated with job stress/strain and indicators of burnout. The greater the PE, the lower the level of job strain.

Hypothesis 3d : PE will be positively associated with job satisfaction.

Hypothesis 3e : PE will positively influence workers' intrinsic motivation.

Worker actions/behaviors

Finally, the aim is also to determine how PE affects worker behaviors, specifically performance, creativity, innovation and organizational citizenship. A key assumption of Thomas and Velthouse's cognitive empowerment model ( 1990 ) is the existence of a continuous cycle encompassing environmental events, task evaluations and behaviors. Environmental events provide information about the consequences of behaviors. Tasks can therefore be evaluated in accordance with PE, providing feedback regarding the individual's behavior (Thomas & Velthouse, 1990 ).

According to Spreitzer ( 1995a ), intrapersonal empowerment mediates the relationship between social-structural antecedents and innovative behavior. Innovation is the successful implementation of creative ideas within an organization (Amabile, 1988 ). Empowered individuals who perceive themselves as competent are more likely to be innovative and creative due to their expectations of success, and because they feel less constrained by the rule-based aspects of their job (Amabile, 1988 ). Moreover, empowerment encourages members of the team to contribute in different ways to common activities (Spreitzer, 1999 ). It is therefore to be expected that more empowered individuals will perform better, engage in more organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs) and adopt a more active attitude to their job (Spreitzer, 2008 ). Sylvia Nabila et al. ( 2021 ) suggested that empowered employees are very responsible, make an extra work effort and are more creative in their jobs, which together tends to enhance their performance at work. Khan and Ghufran ( 2018 ) argue that the relationship between empowerment and OCB stems from the fact that whenever an employee feels that their job has meaning and that they themselves enjoy independence and freedom, are competent and have an impact, the more their behavior is oriented towards a direction that serves the organization—helping colleagues and customers and being courteous, conscientiousness and civic-minded.

Hypothesis 4a : PE will be positively associated with creativity and innovative behavior among workers.

Hypothesis 4b : PE will positively influence job performance.

Hypothesis 4c : PE will be positively associated with organizational citizenship behaviors.

The specific categories and primary variables of the antecedents and consequences of PE are outlined in detail in the Appendix (Tables 6 and 7 ).

Variables that moderate the relationship between PE and its antecedents and consequences

Participants were grouped into four age ranges: 19–29 years, 30–39 years, 40–49 years and over 50 s. Recent research has highlighted age discrimination as a common problem in organizations (Furunes & Mykletun, 2010 ). Age discrimination is the process by which workers are discriminated against solely on account of their age. Schermuly et al. ( 2014 ) have suggested that age discrimination may diminish PE and its components in a number of different ways, with stereotypes decreasing both performance and workers' perceptions of their own competence, and the selection of younger workers to the detriment of older ones reducing meaning. They also argue that the exclusion of older workers from decision-making and engagement processes may diminish both self-determination and impact.

In contrast, Dimitriades and Kufiduse ( 2004 ) found that empowerment was significantly associated with workers' age, and Spreitzer ( 1996 ) identified a positive relationship between age and the competence dimension of empowerment. Furthermore, after categorizing her sample into age ranges, Ozaralli ( 2003 ) found significant differences between those aged between 20 and 30 years and those aged over 40, concluding that older workers feel more empowered.

In light of the above, the aim here is to analyze whether workers' age influences the relationship between PE and either it antecedents ( Hypothesis 5a ) or its consequences ( Hypothesis 5b ). For example, a larger effect size (ES) in the relationship between individual worker characteristics and PE would indicate that the older the worker, the more their personal characteristics influence their PE.

Cultural differences

Recent research has compared the moderator effects of the collectivist and individualist outlooks on PE and its consequences, including job satisfaction and extra-role performance. Fock et al. ( 2011 ) found that the collectivist outlook heightened the effect of self-determination on job satisfaction. Cho and Faerman ( 2010 ) suggested that higher levels of organizational collectivism had a stronger effect on the relationship between PE and extra-role performance than lower levels of this outlook, and Kirkman and Shapiro ( 2001 ) found that teams with a higher level of collectivism reported more empowerment. It is therefore likely that people working in collectivist cultures define themselves as part of a group and prioritize group goals to a greater extent than those working in individualistic environments (Triandis, 2001 ). PE may be more effective in collectivist cultures because members of these cultures may react more strongly to signals that foster identification and inclusion, such as psychological empowerment (Seibert et al., 2011 ).

In contrast, other studies have reported opposite results. For example, Thomas and Rahschulte ( 2018 ) studied the moderating effects of power distance and individualism/collectivism on the relationship between empowering leadership and PE, finding that, in a sample from Rwanda, high levels of collectivism weakened the relationship between empowering leadership and PE among employees, whereas in the USA, the moderating effect of individualism enhanced this relationship.

In relation to power distance, Seibert et al. ( 2004 ) suggested that among people from cultures with a high power distance, a stimulating climate may generate feelings of stress rather than feelings of PE. According to Spreitzer ( 2008 , p.27), in a high power-distance culture, workers may react less positively to PA, since "it may be culturally inappropriate for employees at low levels of an organizational hierarchy to have a significant say in their work". In these high power-distance cultures, it may be that bosses perceive employees with high levels of self-determination and impact as a threat.

Bearing in mind the contradictory findings reported by the literature, in this study, our aim is to explore whether the cultural characteristics of the sample (categorized in accordance with continental origin) influence the relationship between PE and its antecedents and consequences.

Hypothesis 6 : We expect to find significant cultural differences in the associations between PE and its antecedents and consequences.

In their meta-analysis on the antecedents and consequences of PE, Seibert et al. ( 2011 ) suggested that the effectiveness of PE may differ in accordance with the type of occupation being studied. Specifically, employees from the services sector reacted to PE with greater job satisfaction than those working in the manufacturing industry. These authors also highlighted opposing predictions in the literature: if contact with customers provides greater job motivation, the need for PE may decrease; yet at the same time, said contact may increase PE, since workers have more opportunities for discretionary behavior (Seibert et al., 2011 ). In the present study, the aim is to determine whether type of occupation affects the relationship between PE and its antecedents and consequences.

Hypothesis 7a : Associations between PE and its antecedents will have larger ESs in those professions involving close contact with, or the provision of services to, other people.

Hypothesis 7b : Associations between PE and its consequences will have larger ESs in those professions involving close contact with, or the provision of services to, other people.

The present study therefore seeks to answer the following research questions:

What antecedents and consequences are associated with psychological empowerment?

What variables moderate the relationship between PE and its antecedents and consequences?

Following the proposal made by Rassol et al. ( 2019 ), below is a summary of the structure followed by the paper. Section 2 is devoted to the Method. This section outlines the research method, population, sample and inclusion criteria, describes the operationalization of the variables and the evidence provided by the extant literature, and specifies the data analysis strategies used. Section 3 includes a description of the studies included in the meta-analysis and the results of the data analysis; and Sect. 4 provides a discussion of the results, outlines limitations, suggests avenues for future research and explores theoretical and practical implications.

Research approach

The present study adopts a quantitative approach with the aim of emphasizing the accuracy of the measurement procedures and providing evidence in support of Spreitzer's psychological empowerment scale and its relationship with other organizational variables. The aim is to analyze existing confirmatory and objective research into empowerment. We focused on searching for studies that use a survey analysis approach, since this approach is common and enables broad level data to be collected from the target population (Wang et al., 2022 ). Moreover, findings from a large sample can be significantly generalized to the population (Asghar et al., 2022 ). The research method used in this meta-analysis has the advantage of providing more precise results in relation to the research problem under analysis, since said results are a mathematical aggregate of those reported by several studies examining the variables in question (Ankem, 2005 ).

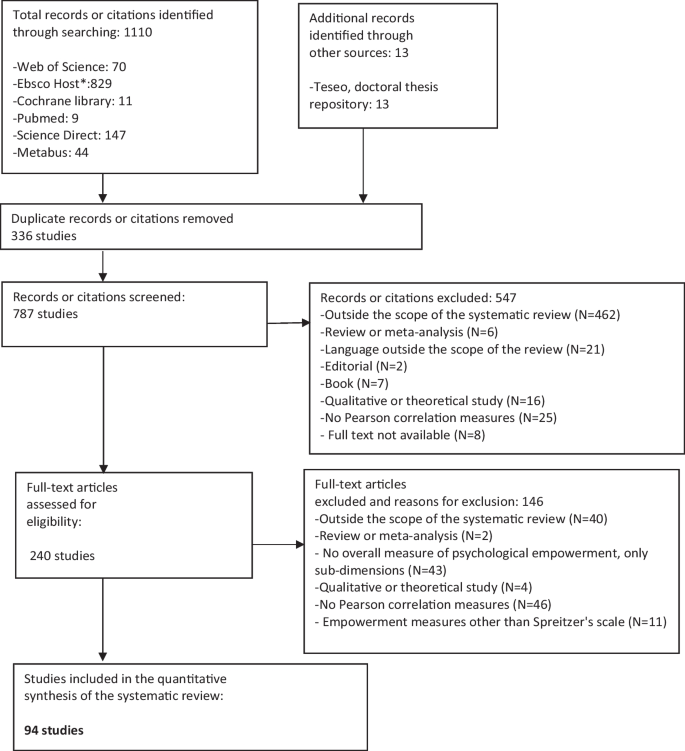

To carry out this meta-analytical study, we followed the guidelines provided by the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) declaration (Moher et al., 2009 ). The electronic search encompassed studies dating from after the publication of Spreitzer's paper outlining the construction and validation of the PE scale ( 1995b ) up until January 2019. It was conducted in digital databases and database aggregators (Web of Science, Ebsco Host, Cochrane library, Pubmed, Science Direct). Figure 2 lists all the databases used in the meta-analysis. We also used Metabus (Bosco et al., 2015 ), a research synthesis platform which offers an advanced search and synthesis engine, thereby representing a fast first step for conducting meta-analyses. A manual search was also performed of journals that habitually publish research in the field of Occupational and Organizational Psychology and which may have attracted studies on psychological empowerment. We included the Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, the Journal of Applied Psychology, and the Academy of Management Journal in our search.

Flow diagram of the different phases of the systematic review (according to PRISMA). Note: In relation to EBSCO HOST, the following databases were selected from the database aggregator (Medline, Academic Search Premier, PsycInfo, PsycArticles, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, ERIC, Open Dissertations, PSICODOC, MLA International Bibliography with Full Text, MLA Directory of Periodicals, EBSCO eClassics Collection (EBSCOhost), International Political Science Abstracts, E-Journals, eBook Education Collection (EBSCOhost), eBook Collection (EBSCOhost), ERIC, Philosophers Index with Full Text, Library & Information Science Source Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts, Teacher Reference Center, and The Serials Directory)

For the majority of the databases searched we used the (TX Empower*) AND (TX Spreitzer) search strategy. In Web of Science, Pubmed and Science Direct, we used the following search chain in order to limit the results and distinguish between different types of empowerment: (Psychological Empowerment) OR (Empower*) NOT (Structural Empowerment) AND (Spreitzer). The search strategy used identified a total of 1110 records. We also identified 13 other studies from other sources, such as doctoral thesis repositories.

After checking the results, 336 duplicate studies were removed. The remaining 787 records were assessed on the basis of their abstracts, with 547 being excluded for not complying (for various reasons) with the inclusion criteria (see Fig. 2 ). Consequently, 240 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 146 were excluded for being outside the scope of the review ( n = 40), being reviews or meta-analyses ( n = 2), not featuring the complete PE measure, featuring only certain dimensions ( n = 43), being theoretical or qualitative studies ( n = 4), not providing Pearson correlation measures ( n = 46) or focusing on empowerment measures other than the theory developed by Spreitzer ( n = 11).

Population, sample and inclusion criteria

To be included in this meta-analysis, articles had to comply with the following criteria: (a) they had to present a piece of correlational empirical research with a sample of workers from any organization; (b) they had to provide Pearson correlation coefficients (or equivalent) of the associations between PE and its antecedents and consequences; (c) the instrument used to measure PE had to be the 12-item scale developed by Spreitzer ( 1995b ), and articles had to provide a general measure of PE; and (d) they had to be written in English, French, Italian or Spanish.

A total of 94 empirical articles were finally included in the meta-analysis, providing 331 independent effect sizes (ESs) with a total of 42,212 participants. Most of the studies included used purposive or convenience sampling and had a cross-sectional study design. Bhatnagar ( 2005 ) used a survey design, but the sampling was randomized, with the organization being chosen first, followed by the sample.

Operationalization of the variables and the evidence provided by the extant literature

First, we compiled a Record Protocol for the moderator variables included in the articles, distinguishing between methodological, substantive and extrinsic characteristics (Sanchez-Meca, 2010 ). The methodological characteristics were sample size, type of non-experimental design (cross-sectional vs. longitudinal) and the reliability measure pertaining to Spreitzer's scale. Substantive characteristics were those linked to participants and context. In relation to participants, the percentage of women in the sample was coded, along with participants' age range (distributed across four groups: 19–29 years, 30–39 years, 40–49 years and over 50 s) and professional category (healthcare, security, services, industry/computing, education and banking/administration). The contextual variable was the location of the study (continent). Extrinsic characteristics were the year in which the study was carried out and the source of publication (published vs. unpublished). Articles were coded independently by two coders. To ensure consistency and guarantee reliability, the coders met to review the results and reach a consensus independently for each sample (Orwin & Vevea, 2010 ).

We also coded the antecedents of PE, distinguishing between psychosocial and organizational factors and individual worker characteristics. Variables linked to the consequences of PE were divided into three groups: affective reactions, attitudinal reactions and worker behaviors.

Data analysis strategies

In this meta-analysis, we extracted information about effect size (ES) in the associations between PE and its antecedents and consequences. We used the Comprehensive Meta-analysis 2.0 program to carry out the analyses (Borenstein et al., 2005 ). Effect size was calculated as the Pearson correlation ( r ), processed using Fisher's Z transformation. To calculate ES, subgroups were combined using the random effects model. The significance level of Z and the confidence intervals (95%) were analyzed to determine the statistical significance of each association between PE and its correlates. To interpret the magnitude of the ES, we followed the empirical guidelines proposed by Hemphill ( 2003 ): r < 0.20 = small ES; r between 0.20 and 0.30 = medium ES; and r > 0.30 = large ES.

To determine heterogeneity, the Q statistic and the I 2 index were calculated. If the Q statistic reaches statistical significance, this means that the different ESs are heterogeneous and are not well represented by the mean effect size. The I 2 index quantifies the heterogeneity existing between studies in percentage terms (Sanchez-Meca, 2010 ). If there is heterogeneity between the ESs, then the influence of moderator variables must be examined. I 2 indexes of around 50% or 75% may respectively be interpreted as medium and high (Borenstein et al., 2009 ). In this meta-analysis, since the I 2 values were high, analyses of variance were performed using weighted ANOVA techniques. The age range of the sample was analyzed, along with continent of origin and type of profession, with the aim of determining whether or not these variables moderated the associations observed between PE and its correlates.

Description of the studies

Of the 94 articles included in the systematic review, 4 were published between 1995 and 2000, 24 between 2001 and 2009 and 66 between 2010 and 2019. The majority were written in English. Only one was written in Spanish and five were in French. The mean age of participants in all samples was 36.15 ( SD = 8.22). The percentage of women in the total sample was 55.90 ( SD = 22.22). Samples mostly came from Asia and America (with 39 and 40 samples, respectively); Europe had 13 and Oceania and Africa had one each.

Antecedents of PE

Table 1 presents a meta-analytical summary of the antecedents of PE. We include the effect size for each meta-analysis, along with the Z significance level, the 95% confidence interval, the Q statistic and the I 2 index. Of all the results found in the meta-analyses, only those pertaining to education (r = -0.001, CI [-0.06, 0.06]) and organizational rank ( r = 0.10, CI [-0.16, 0.36]) were non-significant. The results of the meta-analyses of the associations between psychosocial and organizational variables and PE were significant, with large, positive ES values. The largest ES found ( r = 0.40) was for leadership. These results support Hypotheses 1a, 1b, 1c and 1d. As regards individual worker characteristics, organizational tenure had a small ES ( r = 0.12), negative personality characteristics a medium ES ( r = -0.22) and positive personality characteristics a large ES ( r = 0.31). These findings support Hypotheses 2a, 2d and 2e. In terms of heterogeneity, all I 2 indexes were over 75%, a value interpreted by Borenstein et al. ( 2009 ) as indicative of high heterogeneity. Consequently, we evaluated the influence of the moderator variables as predictors of ES.

Consequences of PE

Table 2 presents a meta-analytical summary of the consequences of PE. All the meta-analyses carried out returned significant results. Job satisfaction ( r = 0.50) and organizational commitment ( r = 0.51) had the largest ESs. Turnover intention ( r = -0.36) and job strain ( r = -0.30) had large but negative ESs. Organizational citizenship behaviors were significant, but had a small ES ( r = 0.18). These results support Hypothesis groups 3 and 4. The I 2 indexes were high, with the exception of creativity (68.48%) and organizational citizenship behaviors (62.9%), for which medium values were obtained. Again, the decision was made to evaluate the variables influencing this heterogeneity between ESs.

Analysis of moderator variables

Table 3 presents the results of the weighted analyses of variance by participants’ age range. We calculated the QW statistic, which indicates the existence of homogeneity within each category, and the QB statistic, which indicates the existence of differences between the mean ES in each category. In relation to psychosocial and organizational variables, both types of statistic were significant in every meta-analysis carried out. This indicates that in addition to the workers’ age range, other relevant mediator variables exist that explain the heterogeneity observed among ESs. Work role and content ( r = 0.35) and social support ( r = 0.08) had smaller ESs among older age ranges.

As for individual characteristics, both positive ( r = 0.47) and negative characteristics ( r = -0.36) had larger ESs among older age ranges. Significant values were found only for organizational tenure among the middle age ranges: 30–39 ( r = 0.17) and 40–49 years ( r = 0.13). As regards the consequences of PE, only creativity was found not to be significant (QB = 3.84, p = 0.27). Organizational commitment obtained large ESs in all age ranges, whereas turnover intention ( r = -0.61) had larger ESs in the upper age range. All affective reactions had larger ESs in the older age ranges, whereas performance was higher in the medium ranges. These results partially support Hypotheses 5a and 5b, since PE was found to vary in accordance with worker age range.

Table 4 presents the results of the ANOVAs by sample origin. In terms of psychosocial and organizational variables, work role and content ( r = -0.05, CI [-0.10, 0.007]) were not significant for America, although they were for the other continents. Social support ( r = 0.42), leadership ( r = 0.46) and structural empowerment ( r = 0.43) obtained larger ESs in collectivist cultures. Regarding individual characteristics, no significant differences were observed between the ESs for organizational tenure. Asian countries had larger ESs than America in terms of the influence of negative personality characteristics.

Significant differences were found for all the consequences of PE in terms of continent of origin. All continents obtained large, similar ESs for organizational commitment. Individualistic cultures had larger ESs in turnover intention ( r = -0.63), job satisfaction ( r = 0.77) and creativity ( r = 0.47). Collectivist cultures only scored higher for job strain ( r = -0.46). Large ESs were observed for performance in Europe and Africa, whereas Asia and America had moderate ESs. These results do not enable Hypothesis 6 to be rejected, since differences were observed in ESs in accordance with the continent on which the studies were carried out.

Table 5 presents the results of the ANOVAs by participant profession. Professions linked to health and education obtained larger ESs for social support ( r = 0.38, r = 0.55). The ES for leadership was larger among those who worked in banking ( r = 0.45) and industry/computing ( r = 0.41). Structural empowerment obtained smaller values in the services sector ( r = 0.29). The ES of work content was large in health and services, and negative in education ( r = -0.51). As regards organizational tenure, the results for banking were not significant, whereas ESs were very small for all other professions. The largest ESs in the positive personality category were found for health ( r = 0.28), services ( r = 0.41) and education ( r = 0.40).

Finally, in professions involving contact with people, the largest ESs were found for organizational commitment ( r = 0.66), turnover intention ( r = -0.61), job strain ( r = -0.43) and job satisfaction ( r = 0.73). Intrinsic motivation was higher in industry ( r = 0.48) and banking ( r = 0.41). No differences were observed between the ESs obtained for any worker behavior. These results partially support Hypotheses 7a and 7b.

The present study aimed to carry out a systematic review and meta-analysis of correlational studies focused on the concept of PE developed by Spreitzer et al. ( 1995a , b ). As well as enabling a better understanding of the antecedents and consequences of PE, the study also aimed to explore potential moderators of the relationship between this variable and its correlates. Finally, the aim was also to compare the results obtained with those reported by other meta-analyses of PE.

Firstly, following the meta-analytical model tested by Seibert et al. ( 2011 ), the antecedents of PE were divided into two categories, psychosocial and organization factors, and individual worker characteristics. The four psychosocial factors (structural empowerment, leadership, work role and social support and trust in the organization) were found to have a significant, strong, positive effect on workers' PE. This finding is consistent with that reported by Seibert et al. ( 2011 ), who also observed strong associations between contextual factors and PE. Indeed, solid evidence exists of the relationship between certain characteristics of leaders and leadership styles and PE (Allameh et al., 2012 ; Bagget, 2015 ; Dust et al., 2018 ; Gumusluoglu & Ilsev, 2009 ; Yahia et al., 2017 ). As regards high-performance managerial practices, Maynard et al. ( 2013 ) studied them separately from structural empowerment in order to highlight the differences that exist in their relationship with PE. Nevertheless, these authors found correlations between PE and high-performance managerial practices that were similar to those found in relation to structural empowerment. In the present meta-analysis, high-performance managerial practices and structural empowerment were included in a single category, with the results indicating that they act as a strong antecedent of PE. In this sense, Messersmith et al. ( 2012 ) observed that building an effective human resources system may have a powerful influence on the attitudes and behaviors of individual employees. As regards social support and trust in the organization, the results indicate that when participants perceive real rewards, trust and support, this leads to greater PE. Both rewards received and income were included in this category, since they are considered tangible assets that can be perceived by workers. In the meta-analysis by Seibert et al. ( 2011 ), however, they were included in the high-performance managerial practices factor. As with the other psychosocial factors, work role and content were found to be strong correlates of PE.

The results pertaining to individual worker characteristics revealed that education and organizational rank did not influence PE. These results are consistent with those found by Seibert et al. ( 2011 ). However, they contradict those reported by Spreitzer ( 1995b ), who found that, in demographic terms, more empowered employees tended to have higher education levels, greater tenure and a higher rank (Spreitzer, 2008 ). Our data suggest that although tenure in the organization does have an influence on PE, it is a weak one. In their meta-analysis, Maynard et al. ( 2013 ) found non-significant correlations between tenure and experience at the organization and PE. Further research and longitudinal studies are required to determine whether individual factors such as gender, age, education and organizational rank may offer a causal explanation for the differences observed in empowerment levels. Nevertheless, the fact that different meta-analyses have reported non-significant or low values in relation to these individual variables leads us to suspect that they are not relevant to empowerment.

In contrast, personality factors were found to be strong antecedents of PE, as indeed posited by the theory of PE (Thomas & Velthouse, 1990 ). Workers who often attribute negative organizational experiences or failures to uncontrollable sources tend to believe they cannot be changed. Moreover, they view effort and outcomes as independent factors. These perceptions may diminish empowerment and inhibit the development of positive expectations (Huang, 2012 ).

The consequences of PE were divided into three categories: affective reactions, attitudinal reactions and worker behaviors. All the factors included in the affective and attitudinal reactions categories were found to be strongly associated with PE. PE therefore acts as a motivational factor that may generate emotional reactions and dispose people to act in a positive manner within the organization. More empowered employees are committed to their organization and are less likely to want to leave, prompting them to behave in a way that contributes to the achievement of common goals. They also have strong affective reactions. They feel satisfied with their job, experience less strain or stress at work and have more intrinsic motivation, understood as the energy resulting from their assessment of the context as empowering. In the present meta-analysis, we believed it was important to separate attitudes from emotional reactions. However, other authors have analyzed these factors together, in the same group, obtaining similar results regarding the strength of their association with PE (Seibert et al., 2011 ; Maynard et al., 2013 ). Li et al. ( 2018 ) also found significant results in their meta-analysis of the relationship between PE and job satisfaction.

As regards worker behaviors, high, significant values were found for creativity. Employees with a greater degree of PE may feel more attracted to their work, propose more creative ideas and resolve more problems (Duan et al., 2018 ). Our results also indicate a statistically significant (although moderate) positive association between PE and performance and organizational citizenship behaviors. This finding is consistent with that reported by Seibert et al. ( 2011 ) and suggests that PE manifests as a motivational factor which impacts attitudes and emotions more than the direct achievement of targets and goals. Nevertheless, more longitudinal research is required in this sense to explore these indirect relationships between PE and worker behaviors, mediated by attitudes and emotions.

Moderators of PE: age, origin and professional area